Genetic resistance to malaria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Human genetic resistance to malaria refers to inherited changes in the DNA of humans which increase resistance to

Malaria does not occur in the cooler, drier climates of the highlands in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world.

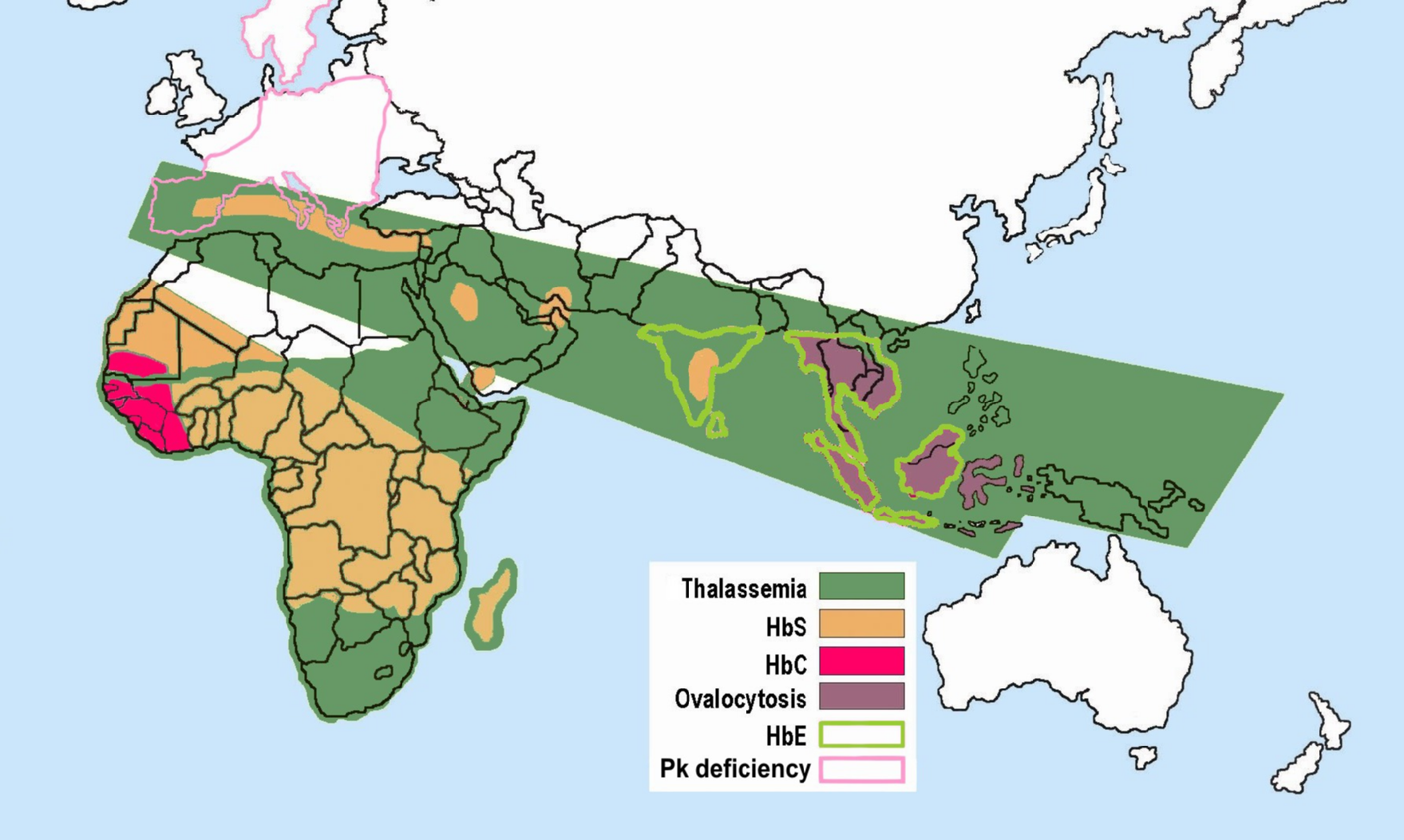

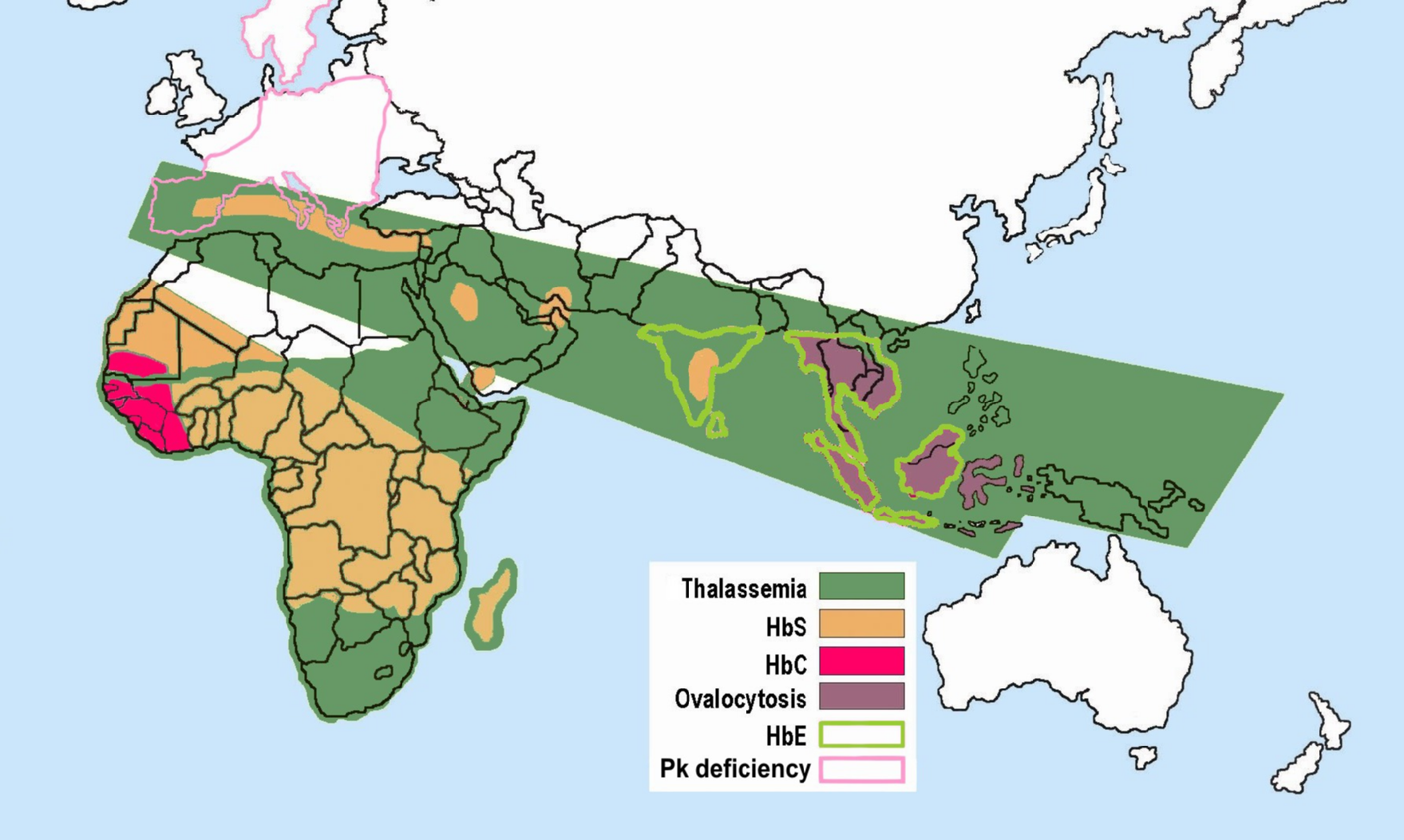

Tens of thousands of individuals have been studied, and high frequencies of abnormal hemoglobins have not been found in any population that was malaria-free. The frequencies of abnormal hemoglobins in different populations vary greatly, but some are undoubtedly polymorphic, having frequencies higher than expected by recurrent mutation. There is no longer doubt that malarial selection played a major role in the distribution of all these polymorphisms. All of these are in malarious areas,

*Sickle cell – The gene for HbS associated with sickle-cell is today distributed widely throughout sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and parts of the Indian subcontinent, where carrier frequencies range from 5–40% or more of the population. Frequencies of sickle-cell heterozygotes were 20–40% in malarious areas of

Malaria does not occur in the cooler, drier climates of the highlands in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world.

Tens of thousands of individuals have been studied, and high frequencies of abnormal hemoglobins have not been found in any population that was malaria-free. The frequencies of abnormal hemoglobins in different populations vary greatly, but some are undoubtedly polymorphic, having frequencies higher than expected by recurrent mutation. There is no longer doubt that malarial selection played a major role in the distribution of all these polymorphisms. All of these are in malarious areas,

*Sickle cell – The gene for HbS associated with sickle-cell is today distributed widely throughout sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and parts of the Indian subcontinent, where carrier frequencies range from 5–40% or more of the population. Frequencies of sickle-cell heterozygotes were 20–40% in malarious areas of

The molecular basis of sickle cell anemia was finally elucidated in 1959 when Ingram perfected the techniques of tryptic peptide fingerprinting. In the mid-1950s, one of the newest and most reliable ways of separating peptides and amino acids was by means of the enzyme trypsin, which split polypeptide chains by specifically degrading the chemical bonds formed by the carboxyl groups of two amino acids, lysine and arginine. Small differences in hemoglobin A and S will result in small changes in one or more of these peptides . To try to detect these small differences, Ingram combined paper electrophoresis and the paper chromotography methods. By this combination he created a two-dimensional method that enabled him to comparatively "fingerprint" the hemoglobin S and A fragments he obtained from the tryspin digest. The fingerprints revealed approximately 30 peptide spots, there was one peptide spot clearly visible in the digest of haemoglobin S which was not obvious in the haemoglobin A fingerprint. The HbS gene defect is a mutation of a single nucleotide (A to T) of the β-globin gene replacing the amino acid glutamic acid with the less polar amino acid valine at the sixth position of the β chain.

HbS has a lower negative charge at physiological pH than does normal adult hemoglobin. The consequences of the simple replacement of a charged amino acid with a hydrophobic, neutral amino acid are far-ranging, Recent studies in West Africa suggest that the greatest impact of Hb S seems to be to protect against either death or severe disease—that is, profound anemia or cerebral malaria—while having less effect on infection per se. Children who are heterozygous for the sickle cell gene have only one-tenth the risk of death from falciparum as do those who are homozygous for the normal hemoglobin gene. Binding of parasitized sickle erythrocytes to endothelial cells and blood monocytes is significantly reduced due to an altered display of ''Plasmodium falciparum'' erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP-1), the parasite's major cytoadherence ligand and virulence factor on the erythrocyte surface.

Protection also derives from the instability of sickle hemoglobin, which clusters the predominant integral red cell membrane protein (called band 3) and triggers accelerated removal by phagocytic cells. Natural antibodies recognize these clusters on senescent erythrocytes. Protection by HbAS involves the enhancement of not only innate but also of acquired immunity to the parasite. Prematurely denatured sickle hemoglobin results in an upregulation of natural antibodies which control erythrocyte adhesion in both malaria and sickle cell disease. Targeting the stimuli that lead to endothelial activation will constitute a promising therapeutic strategy to inhibit sickle red cell adhesion and vaso-occlusion.

This has led to the hypothesis that while

The molecular basis of sickle cell anemia was finally elucidated in 1959 when Ingram perfected the techniques of tryptic peptide fingerprinting. In the mid-1950s, one of the newest and most reliable ways of separating peptides and amino acids was by means of the enzyme trypsin, which split polypeptide chains by specifically degrading the chemical bonds formed by the carboxyl groups of two amino acids, lysine and arginine. Small differences in hemoglobin A and S will result in small changes in one or more of these peptides . To try to detect these small differences, Ingram combined paper electrophoresis and the paper chromotography methods. By this combination he created a two-dimensional method that enabled him to comparatively "fingerprint" the hemoglobin S and A fragments he obtained from the tryspin digest. The fingerprints revealed approximately 30 peptide spots, there was one peptide spot clearly visible in the digest of haemoglobin S which was not obvious in the haemoglobin A fingerprint. The HbS gene defect is a mutation of a single nucleotide (A to T) of the β-globin gene replacing the amino acid glutamic acid with the less polar amino acid valine at the sixth position of the β chain.

HbS has a lower negative charge at physiological pH than does normal adult hemoglobin. The consequences of the simple replacement of a charged amino acid with a hydrophobic, neutral amino acid are far-ranging, Recent studies in West Africa suggest that the greatest impact of Hb S seems to be to protect against either death or severe disease—that is, profound anemia or cerebral malaria—while having less effect on infection per se. Children who are heterozygous for the sickle cell gene have only one-tenth the risk of death from falciparum as do those who are homozygous for the normal hemoglobin gene. Binding of parasitized sickle erythrocytes to endothelial cells and blood monocytes is significantly reduced due to an altered display of ''Plasmodium falciparum'' erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP-1), the parasite's major cytoadherence ligand and virulence factor on the erythrocyte surface.

Protection also derives from the instability of sickle hemoglobin, which clusters the predominant integral red cell membrane protein (called band 3) and triggers accelerated removal by phagocytic cells. Natural antibodies recognize these clusters on senescent erythrocytes. Protection by HbAS involves the enhancement of not only innate but also of acquired immunity to the parasite. Prematurely denatured sickle hemoglobin results in an upregulation of natural antibodies which control erythrocyte adhesion in both malaria and sickle cell disease. Targeting the stimuli that lead to endothelial activation will constitute a promising therapeutic strategy to inhibit sickle red cell adhesion and vaso-occlusion.

This has led to the hypothesis that while

SAO is associated with protection against cerebral malaria in children because it reduces sequestration of erythrocytes parasitized by ''P. falciparum'' in the brain microvasculature. Adhesion of ''P. falciparum''-infected red blood cells to CD36 is enhanced by the cerebral malaria-protective SAO trait . Higher efficiency of sequestration via CD36 in SAO individuals could determine a different organ distribution of sequestered infected red blood cells. These provide a possible explanation for the selective advantage conferred by SAO against cerebral malaria.

SAO is associated with protection against cerebral malaria in children because it reduces sequestration of erythrocytes parasitized by ''P. falciparum'' in the brain microvasculature. Adhesion of ''P. falciparum''-infected red blood cells to CD36 is enhanced by the cerebral malaria-protective SAO trait . Higher efficiency of sequestration via CD36 in SAO individuals could determine a different organ distribution of sequestered infected red blood cells. These provide a possible explanation for the selective advantage conferred by SAO against cerebral malaria.

Detailed study of a cohort of 1022 Kenyan children living near

Detailed study of a cohort of 1022 Kenyan children living near

Favism

{{DEFAULTSORT:Genetic Resistance To Malaria Malaria Human population genetics Evolutionary biology Cell biology

malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. ...

and result in increased survival of individuals with those genetic changes. The existence of these genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

s is likely due to evolutionary pressure

Any cause that reduces or increases reproductive success in a portion of a population potentially exerts evolutionary pressure, selective pressure or selection pressure, driving natural selection. It is a quantitative description of the amount of ...

exerted by parasites of the genus ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a ve ...

'' which cause malaria. Since malaria infects red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "hol ...

s, these genetic changes are most common alterations to molecules essential for red blood cell function (and therefore parasite survival), such as hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythroc ...

or other cellular proteins or enzymes of red blood cells. These alterations generally protect red blood cells from invasion by ''Plasmodium'' parasites or replication of parasites within the red blood cell.

These inherited changes to hemoglobin or other characteristic proteins, which are critical and rather invariant features of mammalian biochemistry, usually cause some kind of inherited disease. Therefore, they are commonly referred to by the names of the blood disorders associated with them, including sickle-cell disease

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of blood disorders typically inherited from a person's parents. The most common type is known as sickle cell anaemia. It results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin found in red ...

, thalassemia

Thalassemias are inherited blood disorders characterized by decreased hemoglobin production. Symptoms depend on the type and can vary from none to severe. Often there is mild to severe anemia (low red blood cells or hemoglobin). Anemia can resul ...

, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PDD), which is the most common enzyme deficiency worldwide, is an inborn error of metabolism that predisposes to red blood cell breakdown. Most of the time, those who are affected have no symptoms. ...

, and others. These blood disorders cause increased morbidity

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that a ...

and mortality in areas of the world where malaria is less prevalent.

Development of genetic resistance to malaria

Microscopicparasites

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson ha ...

, like viruses, protozoans that cause malaria, and others, cannot replicate on their own and rely on a host to continue their life cycles. They replicate by invading the hosts' cells and usurping the cellular machinery to replicate themselves. Eventually, unchecked replication causes the cells to burst, killing the cells and releasing the infectious organisms into the bloodstream where they can infect other cells. As cells die and toxic products of invasive organism replication accumulate, disease symptoms appear. Because this process involves specific proteins produced by the infectious organism as well as the host cell, even a very small change in a critical protein may render infection difficult or impossible. Such changes might arise by a process of mutation in the gene that codes for the protein. If the change is in the gamete, that is, the sperm or egg that join to form a zygote that grows into a human being, the protective mutation will be inherited. Since lethal diseases kill many persons who lack protective mutations, in time, many persons in regions where lethal diseases are endemic come to inherit protective mutations.

When the ''P. falciparum'' parasite infects a host cell, it alters the characteristics of the red blood cell membrane, making it "stickier" to other cells. Clusters of parasitized red blood cells can exceed the size of the capillary circulation, adhere to the endothelium

The endothelium is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the rest of the ve ...

, and block circulation. When these blockages form in the blood vessels surrounding the brain, they cause cerebral hypoxia

Cerebral hypoxia is a form of hypoxia (reduced supply of oxygen), specifically involving the brain; when the brain is completely deprived of oxygen, it is called ''cerebral anoxia''. There are four categories of cerebral hypoxia; they are, in ...

, resulting in neurological

Neurology (from el, νεῦρον (neûron), "string, nerve" and the suffix -logia, "study of") is the branch of medicine dealing with the diagnosis and treatment of all categories of conditions and disease involving the brain, the spinal c ...

symptoms known as cerebral malaria. This condition is characterized by confusion, disorientation, and often terminal coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to respond normally to painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal wake-sleep cycle and does not initiate voluntary actions. Coma patients exhi ...

. It accounts for 80% of malaria deaths. Therefore, mutations that protect against malaria infection and lethality pose a significant advantage.

Malaria has placed the strongest known selective pressure

Any cause that reduces or increases reproductive success in a portion of a population potentially exerts evolutionary pressure, selective pressure or selection pressure, driving natural selection. It is a quantitative description of the amount of ...

on the human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as DNA within the 23 chromosome pairs in cell nuclei and in a small DNA molecule found within individual mitochondria. These are usually treated separately as the ...

since the origin of agriculture within the past 10,000 years. ''Plasmodium falciparum

''Plasmodium falciparum'' is a unicellular protozoan parasite of humans, and the deadliest species of ''Plasmodium'' that causes malaria in humans. The parasite is transmitted through the bite of a female '' Anopheles'' mosquito and causes the ...

'' was probably not able to gain a foothold among Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

n populations until larger sedentary communities emerged in association with the evolution of domestic agriculture in Africa (the agricultural revolution). Several inherited variants in red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), also referred to as red cells, red blood corpuscles (in humans or other animals not having nucleus in red blood cells), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek ''erythros'' for "red" and ''kytos'' for "hol ...

s have become common in parts of the world where malaria is frequent as a result of selection exerted by this parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson h ...

. This selection was historically important as the first documented example of disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that a ...

as an agent of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

in human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, cultu ...

s. It was also the first example of genetically controlled innate immunity

The innate, or nonspecific, immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies (the other being the adaptive immune system) in vertebrates. The innate immune system is an older evolutionary defense strategy, relatively speaking, and is the ...

that operates early in the course of infections, preceding adaptive immunity which exerts effects after several days. In malaria, as in other diseases, innate immunity leads into, and stimulates, adaptive immunity

The adaptive immune system, also known as the acquired immune system, is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized, systemic cells and processes that eliminate pathogens or prevent their growth. The acquired immune system ...

.

Mutations may have detrimental as well as beneficial effects, and any single mutation may have both. Infectiousness of malaria depends on specific proteins present in the cell walls and elsewhere in red blood cells. Protective mutations alter these proteins in ways that make them inaccessible to malaria organisms. However, these changes also alter the functioning and form of red blood cells that may have visible effects, either overtly, or by microscopic examination of red blood cells. These changes may impair the function of red blood cells in various ways that have a detrimental effect on the health or longevity of the individual. However, if the net effect of protection against malaria outweighs the other detrimental effects, the protective mutation will tend to be retained and propagated from generation to generation.

These alterations which protect against malarial infections but impair red blood cells are generally considered blood disorders since they tend to have overt and detrimental effects. Their protective function has only in recent times, been discovered and acknowledged. Some of these disorders are known by fanciful and cryptic names like sickle-cell anemia, thalassaemia, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, ovalocytosis, elliptocytosis and loss of the Gerbich antigen and the Duffy antigen. These names refer to various proteins, enzymes, and the shape or function of red blood cells.

Innate resistance

The potent effect of genetically controlled innate resistance is reflected in the probability of survival of young children in areas where malaria is endemic. It is necessary to study innate immunity in the susceptible age group (younger than four years) because, in older children and adults, the effects of innate immunity are overshadowed by those of adaptive immunity. It is also necessary to study populations in which random use ofantimalarial drug

Antimalarial medications or simply antimalarials are a type of antiparasitic chemical agent, often naturally derived, that can be used to treat or to prevent malaria, in the latter case, most often aiming at two susceptible target groups, young c ...

s does not occur. Some early contributions on innate resistance to infections of vertebrates, including humans, are summarized in Table 1.

It is remarkable that two of the pioneering studies were on malaria. The classical studies on the Toll receptor in ''Drosophila

''Drosophila'' () is a genus of flies, belonging to the family Drosophilidae, whose members are often called "small fruit flies" or (less frequently) pomace flies, vinegar flies, or wine flies, a reference to the characteristic of many speci ...

'' fruit fly were rapidly extended to Toll-like receptor

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a class of proteins that play a key role in the innate immune system. They are single-pass membrane-spanning receptors usually expressed on sentinel cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells, that recognize ...

s in mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur ...

s and then to other pattern recognition receptor

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) play a crucial role in the proper function of the innate immune system. PRRs are germline-encoded host sensors, which detect molecules typical for the pathogens. They are proteins expressed, mainly, by cells of ...

s, which play important roles in innate immunity. However, the early contributions on malaria remain as classical examples of innate resistance, which have stood the test of time.

Mechanisms of protection

The mechanisms by which erythrocytes containing abnormal hemoglobins, or are G6PD deficient, are partially protected against ''P. falciparum'' infections are not fully understood, although there has been no shortage of suggestions. During the peripheral blood stage of replication malaria parasites have a high rate ofoxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements ...

consumption and ingest large amounts of hemoglobin. It is likely that HbS in endocytic vesicles is deoxygenated, polymerizes and is poorly digested. In red cells containing abnormal hemoglobins, or which are G6PD deficient, oxygen radicals are produced, and malaria parasites induce additional oxidative stress. This can result in changes in red cell membranes, including translocation of phosphatidylserine

Phosphatidylserine (abbreviated Ptd-L-Ser or PS) is a phospholipid and is a component of the cell membrane. It plays a key role in cell cycle signaling, specifically in relation to apoptosis. It is a key pathway for viruses to enter cells via ap ...

to their surface, followed by macrophage recognition and ingestion. The authors suggest that this mechanism is likely to occur earlier in abnormal than in normal red cells, thereby restricting multiplication in the former. In addition, binding of parasitized sickle cells to endothelial cells is significantly decreased because of an altered display of ''P. falciparum'' erythrocyte membrane protein-1 (PfMP-1). This protein is the parasite's main cytoadherence ligand and virulence factor on the cell surface. During the late stages of parasite replication red cells are adherent to venous endothelium, and inhibiting this attachment could suppress replication.

Sickle hemoglobin induces the expression of heme oxygenase-1 in hematopoietic

Haematopoiesis (, from Greek , 'blood' and 'to make'; also hematopoiesis in American English; sometimes also h(a)emopoiesis) is the formation of blood cellular components. All cellular blood components are derived from haematopoietic stem cell ...

cells. Carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide ( chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simpl ...

, a byproduct of heme catabolism by heme oxygenase

Heme oxygenase, or haem oxygenase, (HMOX, commonly abbreviated as HO) is an enzyme that catalyzes the degradation of heme to produce biliverdin, ferrous ion, and carbon monoxide.

There are many heme degrading enzymes in nature. In general, onl ...

-1(HO-1), prevents an accumulation of circulating free heme after ''Plasmodium

''Plasmodium'' is a genus of unicellular eukaryotes that are obligate parasites of vertebrates and insects. The life cycles of ''Plasmodium'' species involve development in a blood-feeding insect host which then injects parasites into a ve ...

'' infection, suppressing the pathogenesis of experimental cerebral malaria. Other mechanisms, such as enhanced tolerance to disease mediated by HO-1 and reduced parasitic growth due to translocation of host micro-RNA into the parasite, have been described.

Types of innate resistance

The first line of defense against malaria is mainly exerted by abnormal hemoglobins and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. The three major types of inherited genetic resistance –sickle cell disease

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of blood disorders typically inherited from a person's parents. The most common type is known as sickle cell anaemia. It results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin found in red b ...

, thalassemia

Thalassemias are inherited blood disorders characterized by decreased hemoglobin production. Symptoms depend on the type and can vary from none to severe. Often there is mild to severe anemia (low red blood cells or hemoglobin). Anemia can resul ...

s, and G6PD deficiency

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PDD), which is the most common enzyme deficiency worldwide, is an inborn error of metabolism that predisposes to red blood cell breakdown. Most of the time, those who are affected have no symptoms. ...

– were present in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

world by the time of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

.

Hemoglobin abnormalities

Distribution of abnormal hemoglobins

Malaria does not occur in the cooler, drier climates of the highlands in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world.

Tens of thousands of individuals have been studied, and high frequencies of abnormal hemoglobins have not been found in any population that was malaria-free. The frequencies of abnormal hemoglobins in different populations vary greatly, but some are undoubtedly polymorphic, having frequencies higher than expected by recurrent mutation. There is no longer doubt that malarial selection played a major role in the distribution of all these polymorphisms. All of these are in malarious areas,

*Sickle cell – The gene for HbS associated with sickle-cell is today distributed widely throughout sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and parts of the Indian subcontinent, where carrier frequencies range from 5–40% or more of the population. Frequencies of sickle-cell heterozygotes were 20–40% in malarious areas of

Malaria does not occur in the cooler, drier climates of the highlands in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world.

Tens of thousands of individuals have been studied, and high frequencies of abnormal hemoglobins have not been found in any population that was malaria-free. The frequencies of abnormal hemoglobins in different populations vary greatly, but some are undoubtedly polymorphic, having frequencies higher than expected by recurrent mutation. There is no longer doubt that malarial selection played a major role in the distribution of all these polymorphisms. All of these are in malarious areas,

*Sickle cell – The gene for HbS associated with sickle-cell is today distributed widely throughout sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and parts of the Indian subcontinent, where carrier frequencies range from 5–40% or more of the population. Frequencies of sickle-cell heterozygotes were 20–40% in malarious areas of Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

, Uganda, and Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands ...

. Later studies by many investigators filled in the picture. High frequencies of the HbS gene are confined to a broad belt across Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Co ...

, but excluding most of Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

and the East African highlands; this corresponds closely to areas of malaria transmission. Sickle-cell heterozygote frequencies up to 20% also occur in pockets of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

and Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

that were formerly highly malarious.

The thalassemias have a high incidence in a broad band extending from the Mediterranean basin and parts of Africa, throughout the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, Melanesia, and into the Pacific Islands.

* α-thalassemia, which attains frequencies of 30% in parts of West Africa;

* β-thalassemia, with frequencies up to 10% in parts of Italy;

* HbE, which attains frequencies up to 55% in Thailand and other Southeast Asian countries; HbE is found in the eastern half of the Indian subcontinent and throughout Southeast Asia, where, in some areas, carrier rates may exceed 60% of the population.

* HbC, which attains frequencies approaching 20% in northern Ghana and Burkina-Faso. HbC is restricted to parts of West and North Africa.

*concurrent polymorphisms – double heterozygotes for HbS and β-thalassemia, and for HbS and HbC, suffer from variant forms of sickle-cell disease, milder than SS but likely to reduce fitness before modern treatment was available. As predicted, these variant alleles tend to be mutually exclusive in populations. There is a negative correlation between frequencies of HbS and β-thalassemia in different parts of Greece and of HbS and HbC in West Africa. Where there is no adverse interaction of mutations, as in the case of abnormal hemoglobins and G6PD deficiency, a positive correlation of these variant alleles in populations would be expected and is found.

Sickle-cell

Sickle-cell disease was the genetic disorder to be linked to a mutation of a specific protein. Pauling introduced his fundamentally important concept of sickle cell anemia as a genetically transmitted molecular disease.homozygote

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mo ...

s for the sickle cell gene suffer from disease, heterozygote

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

M ...

s might be protected against malaria. Malaria remains a selective factor for the sickle cell trait.

Thalassemias

It has long been known that a kind of anemia, termedthalassemia

Thalassemias are inherited blood disorders characterized by decreased hemoglobin production. Symptoms depend on the type and can vary from none to severe. Often there is mild to severe anemia (low red blood cells or hemoglobin). Anemia can resul ...

, has a high frequency in some Mediterranean populations, including Greeks and southern Italians. The name is derived from the Greek words for sea (''thalassa''), meaning the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

, and blood (''haima''). Vernon Ingram deserves the credit for explaining the genetic basis of different forms of thalassemia as an imbalance in the synthesis of the two polypeptide chains of hemoglobin.

In the common Mediterranean variant, mutations decrease production of the β-chain (β-thalassemia). In α-thalassemia, which is relatively frequent in Africa and several other countries, production of the α-chain of hemoglobin is impaired, and there is relative over-production of the β-chain. Individuals homozygous for β-thalassemia have severe anemia and are unlikely to survive and reproduce, so selection against the gene is strong. Those homozygous for α-thalassemia also suffer from anemia and there is some degree of selection against the gene.

The lower Himalayan foothills

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 100 ...

and Inner Terai or Doon Valleys of Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is ma ...

and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

are highly malarial due to a warm climate and marshes sustained during the dry season by groundwater percolating down from the higher hills. Malarial forests were intentionally maintained by the rulers of Nepal as a defensive measure. Humans attempting to live in this zone suffered much higher mortality than at higher elevations or below on the drier Gangetic Plain

The Indo-Gangetic Plain, also known as the North Indian River Plain, is a fertile plain encompassing northern regions of the Indian subcontinent, including most of northern and eastern India, around half of Pakistan, virtually all of Bang ...

. However, the Tharu people

The Tharu people are an ethnic group indigenous to the Terai in southern Nepal and northern India. They speak Tharu languages. They are recognized as an official nationality by the Government of Nepal. In the Indian Terai, they live foremost ...

had lived in this zone long enough to evolve resistance via multiple genes. Medical studies among the Tharu and non-Tharu population of the Terai

, image =Terai nepal.jpg

, image_size =

, image_alt =

, caption =Aerial view of Terai plains near Biratnagar, Nepal

, map =

, map_size =

, map_alt =

, map_caption =

, biogeographic_realm = Indomalayan realm

, global200 = Terai-Duar savanna a ...

yielded the evidence that the prevalence of cases of residual malaria is nearly seven times lower among Tharus. The basis for resistance has been established to be homozygosity of α-Thalassemia gene within the local population. Endogamy

Endogamy is the practice of marrying within a specific social group, religious denomination, caste, or ethnic group, rejecting those from others as unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relationships.

Endogamy is common in many cultu ...

along caste and ethnic lines appear to have prevented these genes from being more widespread in neighboring populations.

HbC and HbE erythroids

There is evidence that the persons with α-thalassemia, HbC and HbE have some degree of protection against the parasite. Hemoglobin C (HbC) is an abnormal hemoglobin with substitution of a lysine residue for glutamic acid residue of the β-globin chain, at exactly the same β-6 position as the HbS mutation. The "C" designation for HbC is from the name of the city where it was discovered—Christchurch, New Zealand. People who have this disease, particularly children, may have episodes of abdominal and joint pain, an enlarged spleen, and mild jaundice, but they do not have severe crises, as occur in sickle cell disease. Haemoglobin C is common in malarious areas of West Africa, especially in Burkina Faso. In a large case–control study performed in Burkina Faso on 4,348 Mossi subjects, that HbC was associated with a 29% reduction in risk of clinical malaria in HbAC heterozygotes and of 93% in HbCC homozygotes. HbC represents a ‘slow but gratis’ genetic adaptation to malaria through a transient polymorphism, compared to the polycentric ‘quick but costly’ adaptation through balanced polymorphism of HbS. HbC modifies the quantity and distribution of the variant antigen ''P. falciparum'' erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) on the infected red blood cell surface and the modified display of malaria surface proteins reduces parasite adhesiveness (thereby avoiding clearance by the spleen) and can reduce the risk of severe disease. Hemoglobin E is due to a single point mutation in the gene for the beta chain with a glutamate-to-lysine substitution at position 26. It is one of the most prevalent hemoglobinopathies with 30 million people affected. Hemoglobin E is very common in parts of Southeast Asia. HbE erythrocytes have an unidentified membrane abnormality that renders the majority of the RBC population relatively resistant to invasion by ''P falciparum''.Other erythrocyte mutations

Other genetic mutations besides hemoglobin abnormalities that confer resistance to ''Plasmodia'' infection involve alterations of the cellular surfaceantigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune respon ...

ic proteins, cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment (t ...

structural proteins, or enzymes involved in glycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose () into pyruvate (). The free energy released in this process is used to form the high-energy molecules adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH ...

.

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD or G6PDH) () is a cytosolic enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reaction

: D-glucose 6-phosphate + NADP+ + H2O 6-phospho-D-glucono-1,5-lactone + NADPH + H+

This enzyme participates in the pentose phospha ...

(G6PD) is an important enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

in red cells, metabolizing glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, u ...

through the pentose phosphate pathway

The pentose phosphate pathway (also called the phosphogluconate pathway and the hexose monophosphate shunt and the HMP Shunt) is a metabolic pathway parallel to glycolysis. It generates NADPH and pentoses (5-carbon sugars) as well as ribose 5-pho ...

, an anabolic alternative to catabolic oxidation (glycolysis), while maintaining a reducing environment. G6PD is present in all human cells but is particularly important to red blood cells. Since mature red blood cells lack nuclei and cytoplasmic RNA, they cannot synthesize new enzyme molecules to replace genetically abnormal or ageing ones. All proteins, including enzymes, have to last for the entire lifetime of the red blood cell, which is normally 120 days.

In 1956 Alving and colleagues showed that in some African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

s the antimalarial drug primaquine

Primaquine is a medication used to treat and prevent malaria and to treat ''Pneumocystis'' pneumonia. Specifically it is used for malaria due to ''Plasmodium vivax'' and '' Plasmodium ovale'' along with other medications and for prevention if oth ...

induces hemolytic anemia, and that those individuals have an inherited deficiency of G6PD in erythrocytes. G6PD deficiency

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PDD), which is the most common enzyme deficiency worldwide, is an inborn error of metabolism that predisposes to red blood cell breakdown. Most of the time, those who are affected have no symptoms. ...

is sex-linked, and common in Mediterranean, African and other populations. In Mediterranean countries such individuals can develop a hemolytic diathesis ( favism) after consuming fava beans

''Vicia faba'', commonly known as the broad bean, fava bean, or faba bean, is a species of vetch, a flowering plant in the pea and bean family Fabaceae. It is widely cultivated as a crop for human consumption, and also as a cover crop. Varieti ...

. G6PD deficient persons are also sensitive to several drugs in addition to primaquine.

G6PD deficiency is the second most common enzyme deficiency in humans (after ALDH2

Aldehyde dehydrogenase, mitochondrial is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ''ALDH2'' gene located on chromosome 12. This protein belongs to the aldehyde dehydrogenase family of enzymes. Aldehyde dehydrogenase is the second enzyme of the ...

deficiency), estimated to affect some 400 million people. There are many mutations at this locus, two of which attain frequencies of 20% or greater in African and Mediterranean populations; these are termed the A- and Med mutations. Mutant varieties of G6PD can be more unstable than the naturally occurring enzyme, so that their activity declines more rapidly as red cells age.

This question has been studied in isolated populations where antimalarial drugs were not used in Tanzania, East Africa and in the Republic of the Gambia, West Africa, following children during the period when they are most susceptible to ''falciparum'' malaria. In both cases parasite counts were significantly lower in G6PD-deficient persons than in those with normal red cell enzymes. The association has also been studied in individuals, which is possible because the enzyme deficiency is sex-linked and female heterozygotes are mosaics due to lyonization, where random inactivation of an X-chromosome

The X chromosome is one of the two sex-determining chromosomes (allosomes) in many organisms, including mammals (the other is the Y chromosome), and is found in both males and females. It is a part of the XY sex-determination system and XO sex- ...

in certain cells creates a population of G6PD deficient red blood cells coexisting with normal red blood cells. Malaria parasites were significantly more often observed in normal red cells than in enzyme-deficient cells. An evolutionary genetic analysis of malarial selection of G6PD deficiency genes has been published by Tishkoff and Verelli. The enzyme deficiency is common in many countries that are, or were formerly, malarious, but not elsewhere.

PK deficiency

Pyruvate kinase (PK) deficiency, also called erythrocyte pyruvate kinase deficiency, is an inherited metabolic disorder of the enzyme pyruvate kinase. In this condition, a lack of pyruvate kinase slows down the process of glycolysis. This effect is especially devastating in cells that lack mitochondria because these cells must use anaerobic glycolysis as their sole source of energy because the TCA cycle is not available. One example is red blood cells, which in a state of pyruvate kinase deficiency rapidly become deficient in ATP and can undergo hemolysis. Therefore, pyruvate kinase deficiency can cause hemolytic anemia. There is a significant correlation between severity of PK deficiency and extent of protection against malaria.Elliptocytosis

Elliptocytosis, a blood disorder in which an abnormally large number of the patient's erythrocytes are elliptical. There is much genetic variability amongst those affected. There are three major forms of hereditary elliptocytosis: common hereditary elliptocytosis, spherocytic elliptocytosis andsoutheast Asian ovalocytosis

Southeast Asian ovalocytosis is a blood disorder that is similar to, but distinct from hereditary elliptocytosis. It is common in some communities in Malaysia and Papua New Guinea, as it confers some resistance to cerebral Falciparum Malaria.

Pat ...

.

Southeast Asian ovalocytosis

Ovalocytosis

Southeast Asian ovalocytosis is a blood disorder that is similar to, but distinct from hereditary elliptocytosis. It is common in some communities in Malaysia and Papua New Guinea, as it confers some resistance to cerebral Falciparum Malaria.

Pa ...

is a subtype of elliptocytosis, and is an inherited condition in which erythrocytes have an oval instead of a round shape. In most populations ovalocytosis is rare, but South-East Asian ovalocytosis (SAO) occurs in as many as 15% of the indigenous people of Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions: Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Mal ...

and of Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

. Several abnormalities of SAO erythrocytes have been reported, including increased red cell rigidity and reduced expression of some red cell antigens.

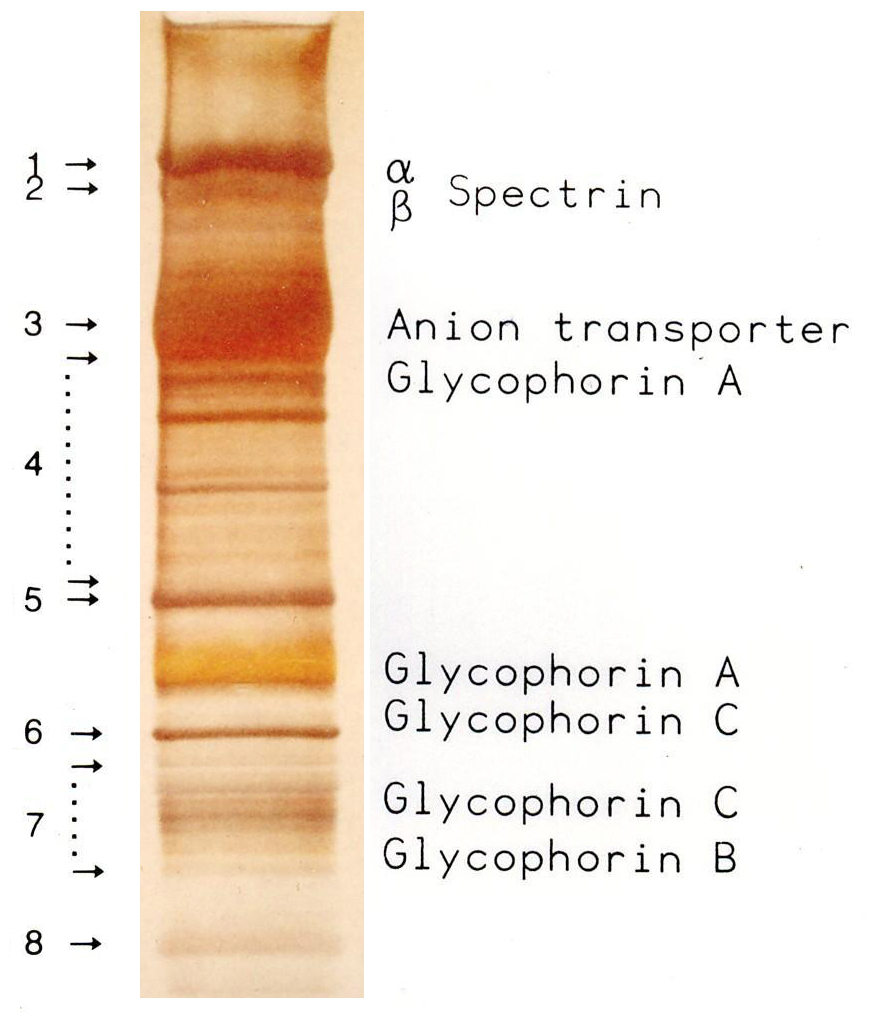

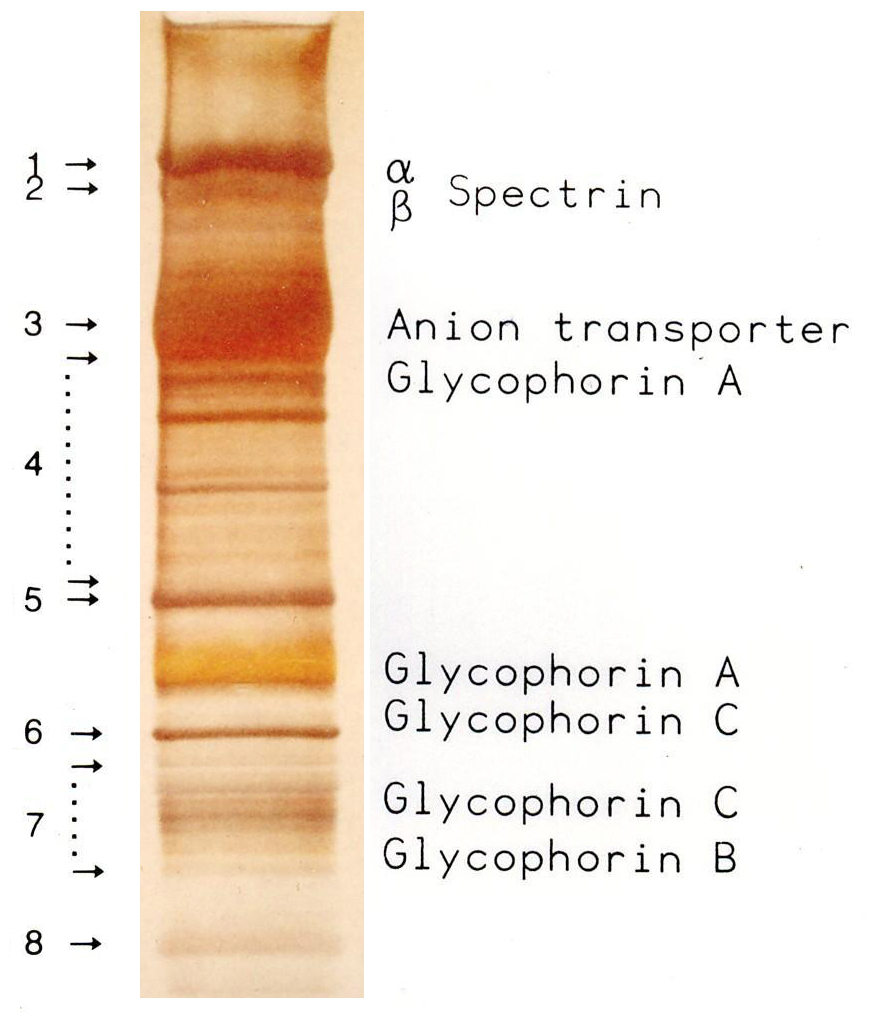

SAO is caused by a mutation in the gene encoding the erythrocyte band 3

Band 3 anion transport protein, also known as anion exchanger 1 (AE1) or band 3 or solute carrier family 4 member 1 (SLC4A1), is a protein that is encoded by the gene in humans.

Band 3 anion transport protein is a phylogenetically-preserved ...

protein. There is a deletion of codons 400–408 in the gene, leading to a deletion of 9 amino-acids at the boundary between the cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains of band 3 protein. Band 3 serves as the principal binding site for the membrane skeleton, a submembrane protein network composed of ankyrin

Ankyrins are a family of proteins that mediate the attachment of integral membrane proteins to the spectrin-actin based membrane cytoskeleton. Ankyrins have binding sites for the beta subunit of spectrin and at least 12 families of integral mem ...

, spectrin

Spectrin is a cytoskeletal protein that lines the intracellular side of the plasma membrane in eukaryotic cells. Spectrin forms pentagonal or hexagonal arrangements, forming a scaffold and playing an important role in maintenance of plasma membr ...

, actin

Actin is a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all eukaryotic cells, where it may be present at a concentration of ov ...

, and band 4.1

Protein 4.1, also known as Beatty's Protein, is a protein associated with the cytoskeleton that in humans is encoded by the ''EPB41'' gene. Protein 4.1 is a major structural element of the erythrocyte membrane skeleton. It plays a key role in ...

. Ovalocyte band 3 binds more tightly than normal band 3 to ankyrin, which connects the membrane skeleton to the band 3 anion transporter. These qualitative defects create a red blood cell membrane that is less tolerant of shear stress and more susceptible to permanent deformation.

SAO is associated with protection against cerebral malaria in children because it reduces sequestration of erythrocytes parasitized by ''P. falciparum'' in the brain microvasculature. Adhesion of ''P. falciparum''-infected red blood cells to CD36 is enhanced by the cerebral malaria-protective SAO trait . Higher efficiency of sequestration via CD36 in SAO individuals could determine a different organ distribution of sequestered infected red blood cells. These provide a possible explanation for the selective advantage conferred by SAO against cerebral malaria.

SAO is associated with protection against cerebral malaria in children because it reduces sequestration of erythrocytes parasitized by ''P. falciparum'' in the brain microvasculature. Adhesion of ''P. falciparum''-infected red blood cells to CD36 is enhanced by the cerebral malaria-protective SAO trait . Higher efficiency of sequestration via CD36 in SAO individuals could determine a different organ distribution of sequestered infected red blood cells. These provide a possible explanation for the selective advantage conferred by SAO against cerebral malaria.

Duffy antigen receptor negativity

''Plasmodium vivax'' has a wide distribution in tropical countries, but is absent or rare in a large region in West and Central Africa, as recently confirmed by PCR species typing. This gap in distribution has been attributed to the lack of expression of the Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines (DARC) on the red cells of many sub-Saharan Africans. Duffy negative individuals are homozygous for a DARC allele, carrying a single nucleotide mutation (DARC 46 T → C), which impairs promoter activity by disrupting a binding site for the hGATA1 erythroid lineage transcription factor. In widely cited ''in vitro'' and ''in vivo'' studies, Miller et al. reported that the Duffy blood group is the receptor for ''P. vivax'' and that the absence of the Duffy blood group on red cells is the resistance factor to ''P. vivax'' in persons of African descent. This has become a well-known example of innate resistance to an infectious agent because of the absence of a receptor for the agent on target cells. However, observations have accumulated showing that the original Miller report needs qualification. In human studies of ''P. vivax'' transmission, there is evidence for the transmission of ''P. vivax'' among Duffy-negative populations in Western Kenya, the BrazilianAmazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek mythology

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technolog ...

region, and Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Afric ...

. The Malagasy people

The Malagasy (french: Malgache) are an Austronesian-speaking African ethnic group native to the island country of Madagascar. Traditionally, the population have been divided by subgroups (tribes or ethnicities). Examples include "Highlander ...

on Madagascar have an admixture of Duffy-positive and Duffy-negative people of diverse ethnic backgrounds. 72% of the island population were found to be Duffy-negative. ''P. vivax'' positivity was found in 8.8% of 476 asymptomatic Duffy-negative people, and clinical ''P. vivax'' malaria was found in 17 such persons. Genotyping indicated that multiple ''P. vivax'' strains were invading the red cells of Duffy-negative people. The authors suggest that among Malagasy populations there are enough Duffy-positive people to maintain mosquito transmission and liver infection. More recently, Duffy negative individuals infected with two different strains of ''P. vivax'' were found in Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

and Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea ( es, Guinea Ecuatorial; french: Guinée équatoriale; pt, Guiné Equatorial), officially the Republic of Equatorial Guinea ( es, link=no, República de Guinea Ecuatorial, french: link=no, République de Guinée équatoria ...

; further, ''P. vivax'' infections were found both in humans and mosquitoes, which means that active transmission is occurring. The frequency of such transmission is still unknown. Because of these several reports from different parts of the world it is clear that some variants of ''P. vivax'' are being transmitted to humans who are not expressing DARC on their red cells. The same phenomenon has been observed in New World monkeys. However, DARC still appears to be a major receptor for human transmission of ''P. vivax''.

The distribution of Duffy negativity in Africa does not correlate precisely with that of ''P. vivax'' transmission. Frequencies of Duffy negativity are as high in East Africa (above 80%), where the parasite is transmitted, as they are in West Africa, where it is not. The potency of ''P. vivax'' as an agent of natural selection is unknown and may vary from location to location. DARC negativity remains a good example of innate resistance to an infection, but it produces a relative and not an absolute resistance to ''P. vivax'' transmission.

Gerbich antigen receptor negativity

The Gerbich antigen system is an integral membrane protein of the erythrocyte and plays a functionally important role in maintaining erythrocyte shape. It also acts as the receptor for the ''P. falciparum'' erythrocyte binding protein. There are fouralleles

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chrom ...

of the gene which encodes the antigen, Ge-1 to Ge-4. Three types of Ge antigen negativity are known: Ge-1,-2,-3, Ge-2,-3 and Ge-2,+3. persons with the relatively rare phenotype Ge-1,-2,-3, are less susceptible (~60% of the control rate) to invasion by ''P. falciparum''. Such individuals have a subtype of a condition called hereditary elliptocytosis

Hereditary elliptocytosis, also known as ovalocytosis, is an inherited blood disorder in which an abnormally large number of the person's red blood cells are elliptical rather than the typical biconcave disc shape. Such morphologically distinctive ...

, characterized by oval or elliptical shape erythrocytes.

Other rare erythrocyte mutations

Rare mutations of glycophorin A and B proteins are also known to mediate resistance to ''P. falciparum''.Human leucocyte antigen polymorphisms

Human leucocyte antigen (HLA) polymorphisms common in West Africans but rare in other racial groups are associated with protection from severe malaria. This group of genes encodes cell-surface antigen-presenting proteins and has many other functions. In West Africa, they account for as great a reduction in disease incidence as the sickle-cell hemoglobin variant. The studies suggest that the unusual polymorphism ofmajor histocompatibility complex

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a large locus on vertebrate DNA containing a set of closely linked polymorphic genes that code for cell surface proteins essential for the adaptive immune system. These cell surface proteins are cal ...

genes has evolved primarily through natural selection by infectious pathogens.

Polymorphisms at the HLA loci, which encode proteins that participate in antigen presentation, influence the course of malaria. In West Africa an HLA class I antigen (HLA Bw53) and an HLA class II haplotype (DRB1*13OZ-DQB1*0501) are independently associated with protection against severe malaria. However, HLA correlations vary, depending on the genetic constitution of the polymorphic malaria parasite, which differs in different geographic locations.

Hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin

Some studies suggest that high levels offetal hemoglobin

Fetal hemoglobin, or foetal haemoglobin (also hemoglobin F, HbF, or α2γ2) is the main oxygen carrier protein in the human fetus. Hemoglobin F is found in fetal red blood cells, and is involved in transporting oxygen from the mother's bloodstr ...

(HbF) confer some protection against falciparum malaria in adults with Hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin

Hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH) is a benign condition in which increased fetal hemoglobin (hemoglobin F, HbF) production continues well into adulthood, disregarding the normal shutoff point after which only adult-type hemoglobin s ...

.

Validating the malaria hypothesis

Evolutionary biologistJ.B.S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (; 5 November 18921 December 1964), nicknamed "Jack" or "JBS", was a British-Indian scientist who worked in physiology, genetics, evolutionary biology, and mathematics. With innovative use of statistics in biolo ...

was the first to give a hypothesis on the relationship between malaria and the genetic disease. He first delivered his hypothesis at the Eighth International Congress of Genetics held in 1948 at Stockholm on a topic "The Rate of Mutation of Human Genes". He formalised in a technical paper published in 1949 in which he made a prophetic statement: "The corpuscles of the anaemic heterozygotes are smaller than normal, and more resistant to hypotonic solutions. It is at least conceivable that they are also more resistant to attacks by the sporozoa which cause malaria." This became known as 'Haldane's malaria hypothesis', or concisely, the 'malaria hypothesis'.

Detailed study of a cohort of 1022 Kenyan children living near

Detailed study of a cohort of 1022 Kenyan children living near Lake Victoria

Lake Victoria is one of the African Great Lakes. With a surface area of approximately , Lake Victoria is Africa's largest lake by area, the world's largest tropical lake, and the world's second-largest fresh water lake by surface area after ...

, published in 2002, confirmed this prediction. Many SS children still died before they attained one year of age. Between 2 and 16 months the mortality in AS children was found to be significantly lower than that in AA children. This well-controlled investigation shows the ongoing action of natural selection through disease in a human population.

Analysis of genome wide association

In genomics, a genome-wide association study (GWA study, or GWAS), also known as whole genome association study (WGA study, or WGAS), is an observational study of a genome-wide set of genetic variants in different individuals to see if any varian ...

(GWA) and fine-resolution association mapping is a powerful method for establishing the inheritance of resistance to infections and other diseases. Two independent preliminary analyses of GWA association with severe falciparum malaria in Africans have been carried out, one by the Malariagen Consortium in a Gambian population and the other by Rolf Horstmann (Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Hamburg) and his colleagues on a Ghanaian population. In both cases the only signal of association reaching genome-wide significance was with the ''HBB'' locus encoding the ''β''-chain of hemoglobin, which is abnormal in HbS. This does not imply that HbS is the only gene conferring innate resistance to falciparum malaria; there could be many such genes exerting more modest effects that are challenging to detect by GWA because of the low levels of linkage disequilibrium

In population genetics, linkage disequilibrium (LD) is the non-random association of alleles at different loci in a given population. Loci are said to be in linkage disequilibrium when the frequency of association of their different alleles is h ...

in African populations. However, the same GWA association in two populations is powerful evidence that the single gene conferring strongest innate resistance to ''falciparum'' malaria is that encoding HbS.

Fitnesses of different genotypes

The fitnesses of differentgenotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

s in an African region where there is intense malarial selection were estimated by Anthony Allison in 1954. In the Baamba population living in the Semliki Forest region in Western Uganda the sickle-cell heterozygote (AS) frequency is 40%, which means that the frequency

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time. It is also occasionally referred to as ''temporal frequency'' for clarity, and is distinct from ''angular frequency''. Frequency is measured in hertz (Hz) which is eq ...

of the sickle-cell gene is 0.255 and 6.5% of children born are SS homozygotes.

It is a reasonable assumption that until modern treatment was available three-quarters of the SS homozygotes failed to reproduce. To balance this loss of sickle-cell genes, a mutation rate

In genetics, the mutation rate is the frequency of new mutations in a single gene or organism over time. Mutation rates are not constant and are not limited to a single type of mutation; there are many different types of mutations. Mutation rates ...

of 1:10.2 per gene per generation would be necessary. This is about 1000 times greater than mutation rates measured in ''Drosophila

''Drosophila'' () is a genus of flies, belonging to the family Drosophilidae, whose members are often called "small fruit flies" or (less frequently) pomace flies, vinegar flies, or wine flies, a reference to the characteristic of many speci ...

'' and other organisms and much higher than recorded for the sickle-cell locus in Africans. To balance the polymorphism, Anthony Allison estimated that the fitness of the AS heterozygote would have to be 1.26 times than that of the normal homozygote. Later analyses of survival figures have given similar results, with some differences from site to site. In Gambians, it was estimated that AS heterozygotes have 90% protection against ''P. falciparum''-associated severe anemia and cerebral malaria, whereas in the Luo population of Kenya it was estimated that AS heterozygotes have 60% protection against severe malarial anemia. These differences reflect the intensity of transmission of ''P. falciparum'' malaria from locality to locality and season to season, so fitness calculations will also vary. In many African populations the AS frequency is about 20%, and a fitness superiority over those with normal hemoglobin of the order of 10% is sufficient to produce a stable polymorphism.Glossary

* actin, ankrin, spectrin – proteins that are the major components of the cytoskeleton scaffolding within a cell's cytoplasm * aerobic – uses oxygen for the production of energy (contrast anaerobic) * allele – one of two or more alternative forms of a gene that arise by mutation * α-chain / β-chain (hemoglobin) – subcomponents of the hemoglobin molecule; two α-chains and two β-chains make up normal hemoglobin (HbA) * alveolar – pertaining to the alveoli, the tiny air sacs in the lungs * amino acid – any of twenty organic compounds that are subunits of protein in the human body * anabolic – of or relating to the synthesis of complex molecules in living organisms from simpler ones * together with the storage of energy; constructive metabolism (contrast catabolic) * anaerobic – refers to a process or reaction which does not require oxygen, but produces energy by other means (contrast aerobic) * anion transporter (organic) – molecules that play an essential role in the distribution and excretion of numerous endogenous metabolic products and exogenous organic anions * antigen – any substance (as an immunogen or a hapten) foreign to the body that evokes an immune response either alone or after forming a complex with a larger molecule (as a protein) and that is capable of binding with a component (as an antibody or T cell) of the immune system * ATP – (Adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is an organic compound that provides energy to drive many processes in living cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, condensate dissolution, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known forms ...

) – an organic molecule containing high energy phosphate bonds used to transport energy within a cell

* catabolic – of or relatig to the breakdown of complex molecules in living organisms to form simpler ones, together with the release of energy; destructive metabolism (contrast anabolic)

* chemokine – are a family of small cytokines, or signaling proteins secreted by cells

* codon – a sequence of three nucleotides which specify which amino acid will be added next during protein synthesis

* corpuscle – obsolete name for red blood cell

* cytoadherance – infected red blood cells may adhere to blood vellel walls and uninfected red blood cells

* cytoplasm – clear jelly-like substance, mostly water, inside a cell

* diathesis – a tendency to suffer from a particular medical condition

* DNA – deoxyribonucleic acid, the hereditary material of the genome

* ''Drosophila'' – a kind of fruit fly used for genetic experimentation because of ease of reproduction and manipulation of its genome

* endocytic – the transport of solid matter or liquid into a cell by means of a coated vacuole or vesicle

* endogamy – the custom of marrying only within the limits of a local community, clan, or tribe

* endothelial – of or referring to the thin inner surface of blood vessels

* enzyme – a protein that promotes a cellular process, much like a catalyst in an ordinary chemical reaction

* epidemiology – the study of the spread of disease within a population

* erythrocyte – red blood cell, which with the leucocytes make up the cellular content of the blood (contrast leucocyte)

* erythroid – of or referring to erythrocytes, red blood cells

* fitness (genetic) – loosely, reproductive success that tends to propagate a trait or traits (see natural selection)

* genome – (abstractly) all the inheritable traits of an organism; represented by its chromosomes

* genotype – the genetic makeup of a cell, an organism, or an individual usually with reference to a specific trait

* glycolysis – the breakdown of glucose by enzymes, releasing energy

* glycophorin – transmembrane proteins of red blood cells

* haplotype – a set of DNA variations, or polymorphisms, that tend to be inherited together.

* Hb (HbC, HbE, HbS, etc.) hemoglobin (hemoglobin polymorphisms: hemoglobin type C, hemoglobin type E,

* hemoglobin type S)

* hematopoietic (stem cell) – the blood stem cells that give rise to all other blood cells

* heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) – an enzyme that breaks down heme, the iron-containing non-protein part of hemoglobin

* hemoglobin – iron based organic molecule in red blood cells that transports oxygen and gives blood its red color

* hemolysis – the rupturing of red blood cells and the release of their contents (cytoplasm) into surrounding fluid (e.g., blood plasma)

* heterozygous – possessing only one copy of a gene for a particular trait

* homozygous – possessing two identical copies of a gene for a particular trait, one from each parent

* hypotonic – denotes a solution of lower osmotic pressure than another solution with which it is in contact, so that certain molecules will migrate from the region of higher osmotic pressure to the region of lower osmotic pressure, until the pressures are equalized

* ''in vitro'' – in a test tube or other laboratory vessel; usually used in regard to a testing protocol

* ''in vivo'' – in a live human (or animal); usually used in regard to a testing protocol

* leucocyte – white blood cell, part of the immune system, which together with red blood cells, comprise the cellular component of the blood (contrast erythrocyte)

* ligand – an extracellular signal molecule, which when it binds to a cellular receptor, causes a response by the cell

* locus (gene or chromosome) – the specific location of a gene or DNA sequence or position on a chromosome

* macrophage – a large white blood cell, part of the immune system that ingests foreign particles and infectious microorganisms

* major histocompatibility complex (MHC) – proteins found on the surfaces of cells that help the immune system recognize foreign substances; also called the human leucocyte antigen (HLA) system

* micro-RNA – a cellular RNA fragment that prevents the production of a particular protein by binding to and destroying the messenger RNA that would have produced the protein.

* microvasculature – very small blood vessels

* mitochondria – energy producing organelles of a cell

* mutation – a spontaneous change to a gene, arising from an error in replication of DNA; usually mutations are referred to in the context of inherited mutations, i.e. changes to the gametes

* natural selection – the gradual process by which biological traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of the effect of inherited traits on the differential reproductive success of organisms interacting with their environment (closely related to fitness)

* nucleotide – organic molecules that are subunits, of nucleic acids like DNA and RNA

* nucleic acid – a complex organic molecule present in living cells, esp. DNA or RNA, which consist of many nucleotides linked in a long chain.

* oxygen radical – a highly reactive ion containing oxygen, capable of damaging microorganisms and normal tissues.

* pathogenesis – the manner of development of a disease

* PCR – Polymerase Chain Reaction, an enzymatic reaction by which DNA is replicated in a test tube for subsequent testing or analysis

* phenotype – the composite of an organism's observable characteristics or traits, such as its morphology

* ''Plasmodium'' – the general type (genus) of the protozoan microorganisms that cause malaria, though only a few of them do

* polymerize – to combine replicated subunits into a longer molecule (usually referring to synthetic materials, but also organic molecules)

* polymorphism – the occurrence of something in several different forms, as for example hemoglobin (HbA, HbC, etc.)

* polypeptide – a chain of amino acids forming part of a protein molecule

* receptor (cellular surface) – specialized integral membrane proteins that take part in communication between the cell and the outside world; receptors are responsive to specific ligands that attach to them.

* reducing environment (cellular) – reducing environment is one where oxidation is prevented by removal of oxygen and other oxidising gases or vapours, and which may contain actively reducing gases such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide and gases that would oxidize in the presence of oxygen, such as hydrogen sulfide.

* RNA – ribonucleic acid, a nucleic acid present in all living cells. Its principal role is to act as a messenger carrying instructions from DNA for controlling the synthesis of proteins

* sequestration (biology) – process by which an organism accumulates a compound or tissue (as red blood cells) from the environment

* sex-linked – a trait associated with a gene that is carried only by the male or female parent (contrast with autosomal)

* Sporozoa – a large class of strictly parasitic nonmotile protozoans, including ''Plasmodia'' which cause malaria

* TCA cycle – TriCarboxylic Acid cycle is a series of enzyme-catalyzed chemical reactions that form a key part of aerobic respiration in cells

* translocation (cellular biology) – movement of molecules from outside to inside (or vice versa) of a cell

* transmembrane – existing or occurring across a cell membrane

* venous – of or referring to the veins

* vesicle – a small organelle within a cell, consisting of fluid enclosed by a fatty membrane

* virulence factors – enable an infectious agent to replicate and disseminate within a host in part by subverting or eluding host defenses.

See also

*Adaptive immunity

The adaptive immune system, also known as the acquired immune system, is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized, systemic cells and processes that eliminate pathogens or prevent their growth. The acquired immune system ...

*Malaria vaccine

A malaria vaccine is a vaccine that is used to prevent malaria. The only approved use of a vaccine outside the EU, as of 2022, is RTS,S, known by the brand name ''Mosquirix''. In October 2021, the WHO for the first time recommended the large- ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* Dronamraju KR, Arese P (2006) ''Malaria: Genetic and Evolutionary Aspects'', Springer; Berlin, / * Faye FBK (2009) ''Malaria Resistance or Susceptibility in Red Cells Disorders'', Nova Science Publishers Inc, New York.External links

Favism

{{DEFAULTSORT:Genetic Resistance To Malaria Malaria Human population genetics Evolutionary biology Cell biology