Francisco Elías de Tejada y Spínola on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Francisco Elías de Tejada y Spínola Gómez (April 6, 1917 – February 18, 1978) was a Spanish scholar and a

The Tejada family originated from

The Tejada family originated from

Already in 1935 Tejada was nominated Profesor Ayudante de Derecho Político in Madrid, an assignment held shortly as he soon left for Germany. When in the Nationalist army he was giving lectures at letters and philosophy courses organized by Universidad de Sevilla, in 1939 publishing his first works. Having obtained PhD laurels thanks to a thesis on Jerónimo Castillo de Bobadilla, in 1939 Tejada returned to Madrid as Professor Ayudante to assist Nicolás Pérez Serrano at Derecho Político. In 1940 he applied for chair of philosophy of law in Seville and Oviedo, but during the routine contest he was defeated by counter-candidates; referees described him as erudite and brilliant speaker, but also disoriented, immature, not adhering to the point, lacking reflexive spirit, excessively lyrical and repetitive. Also in 1940 Tejada left to pursue research abroad, having the unique opportunity to compare the early wartime realm in Berlin and in

Already in 1935 Tejada was nominated Profesor Ayudante de Derecho Político in Madrid, an assignment held shortly as he soon left for Germany. When in the Nationalist army he was giving lectures at letters and philosophy courses organized by Universidad de Sevilla, in 1939 publishing his first works. Having obtained PhD laurels thanks to a thesis on Jerónimo Castillo de Bobadilla, in 1939 Tejada returned to Madrid as Professor Ayudante to assist Nicolás Pérez Serrano at Derecho Político. In 1940 he applied for chair of philosophy of law in Seville and Oviedo, but during the routine contest he was defeated by counter-candidates; referees described him as erudite and brilliant speaker, but also disoriented, immature, not adhering to the point, lacking reflexive spirit, excessively lyrical and repetitive. Also in 1940 Tejada left to pursue research abroad, having the unique opportunity to compare the early wartime realm in Berlin and in  Since the early 1970s Tejada intended to move to Madrid, but his 1971 and 1974 bids for Complutense failed. His 1975 bid for Universidad Autónoma took an awkward turn, when Tejada challenged the referees appointed as linguistically incompetent. His protest was dismissed and in 1976 he lost to Elías Díaz García, appealing the decision; the issue was not settled before his death. However, in 1977 he was appointed with no contest to cátedra de Derecho Natural y Filosofía del Derecho at Complutense; death interrupted his first course in Madrid.

Though member of a number of scientific institutions around the world, recipient of a few

Since the early 1970s Tejada intended to move to Madrid, but his 1971 and 1974 bids for Complutense failed. His 1975 bid for Universidad Autónoma took an awkward turn, when Tejada challenged the referees appointed as linguistically incompetent. His protest was dismissed and in 1976 he lost to Elías Díaz García, appealing the decision; the issue was not settled before his death. However, in 1977 he was appointed with no contest to cátedra de Derecho Natural y Filosofía del Derecho at Complutense; death interrupted his first course in Madrid.

Though member of a number of scientific institutions around the world, recipient of a few

Tejada is considered member of the natural law school and its key representative during the Franco era, influenced by early modern Spanish jurists like Francisco Suarez but mostly following the

Tejada is considered member of the natural law school and its key representative during the Franco era, influenced by early modern Spanish jurists like Francisco Suarez but mostly following the  For Tejada the law resulted from God assuming a decisive role, but rendering it possible to find acceptable reasons for an objective-value-based human agency; natural law stemmed from conjunction of divine power and human liberty. Its purpose was twofold: salvation and vocation, corresponding to justice in relations to God and security in relations to other people. Though some scholars point to some confusion as to the terms used, most agree that for Tejada law was "la norma política con contenido justo", colloquially described as where politics and ethics overlapped, a sovereign normative system related but clearly separate from religion. Some students conclude that Tejada was close to normativism, others find this suggestion too restrictive and claim that for him, law was far more than a norm. A distinctive thread of his jurisprudential discourse was its application to vastly distinct cultural realms, though he attempted to sublimate a specific Hispanic natural law.

Tejada kept writing on theory of law throughout all of his academic career; his first contribution was published in 1942 and his new pieces are being published posthumously. Except two volumes of ''Historia de la filosofía del derecho y del Estado'' (1946), until the very late of his life Tejada's works were mostly articles in specialized reviews, lectures delivered at jurisprudential conferences or compendium-like textbooks intended for students. Tejada's vastly erudite opus magnum, a systematic in-depth lecture gathering all his ideas on law theory was ''Tratado de filosofia del derecho'', published in Seville in two volumes respectively in 1974 and 1977. It is not clear how many of his almost 400 works fall into theory of law, though their number might near one hundred.

For Tejada the law resulted from God assuming a decisive role, but rendering it possible to find acceptable reasons for an objective-value-based human agency; natural law stemmed from conjunction of divine power and human liberty. Its purpose was twofold: salvation and vocation, corresponding to justice in relations to God and security in relations to other people. Though some scholars point to some confusion as to the terms used, most agree that for Tejada law was "la norma política con contenido justo", colloquially described as where politics and ethics overlapped, a sovereign normative system related but clearly separate from religion. Some students conclude that Tejada was close to normativism, others find this suggestion too restrictive and claim that for him, law was far more than a norm. A distinctive thread of his jurisprudential discourse was its application to vastly distinct cultural realms, though he attempted to sublimate a specific Hispanic natural law.

Tejada kept writing on theory of law throughout all of his academic career; his first contribution was published in 1942 and his new pieces are being published posthumously. Except two volumes of ''Historia de la filosofía del derecho y del Estado'' (1946), until the very late of his life Tejada's works were mostly articles in specialized reviews, lectures delivered at jurisprudential conferences or compendium-like textbooks intended for students. Tejada's vastly erudite opus magnum, a systematic in-depth lecture gathering all his ideas on law theory was ''Tratado de filosofia del derecho'', published in Seville in two volumes respectively in 1974 and 1977. It is not clear how many of his almost 400 works fall into theory of law, though their number might near one hundred.

As historian of political ideas Tejada clearly focused on broad Hispanic realm: he published studies on Castile,

As historian of political ideas Tejada clearly focused on broad Hispanic realm: he published studies on Castile,  Tejada understood political thought as a vehicle of sustaining tradition and ignored the imperial and ethnic dimensions of Hispanidad. He viewed the Hispanic political community as forged by will of the people forming its components, not as a result of conquest. Ethnic features were merely means of transmitting heritage and a nation was defined as commonality of tradition, as opposed to positivist definitions focusing on features like language, geography, regime etc.; it enabled implantation of Hispanidad in vastly different settings of the Philippines,

Tejada understood political thought as a vehicle of sustaining tradition and ignored the imperial and ethnic dimensions of Hispanidad. He viewed the Hispanic political community as forged by will of the people forming its components, not as a result of conquest. Ethnic features were merely means of transmitting heritage and a nation was defined as commonality of tradition, as opposed to positivist definitions focusing on features like language, geography, regime etc.; it enabled implantation of Hispanidad in vastly different settings of the Philippines,

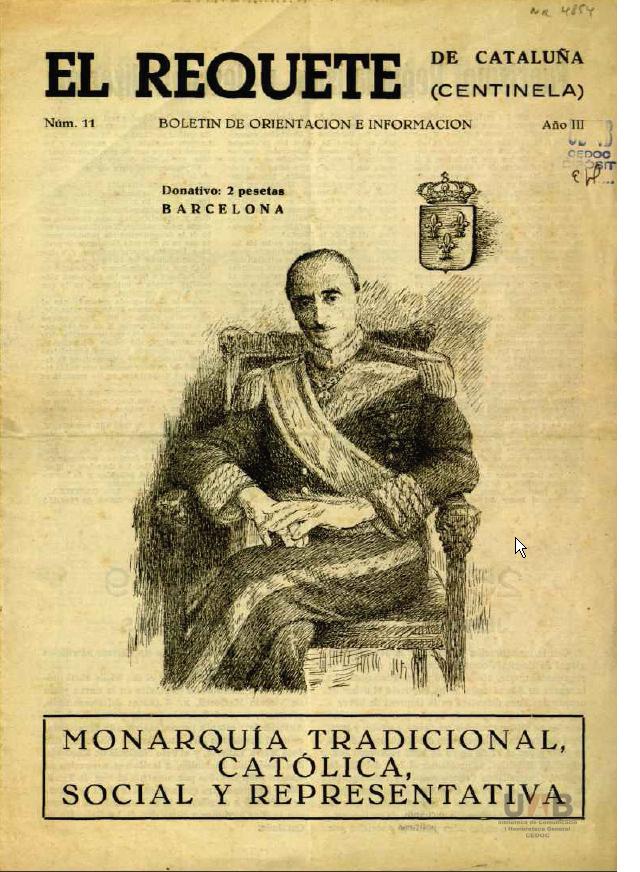

Initially Tejada developed a Hispanidad-oriented leadership theory of

Initially Tejada developed a Hispanidad-oriented leadership theory of  Tejada's works on theory of politics are visibly less numerous than those on theory of law or on history of political thought; moreover, some of them resemble political manifestos rather than scholarly writings. Preceded by caudillaje-oriented brochures of the late 1930s, the main body of his Traditionalism was laid out mostly in the 1950s, following activity in Academia Vazquez de Mella; its most complete and straightforward lecture was ''La monarquía tradicional'' (1954), though some, like ''El tradicionalismo político español'', remained in manuscript. The vision was further refined in details in the 1960s, especially during Congresses of Traditionalist Studies and systematically revisited in the early 1970s, mostly as result of political struggle taking place within Carlism: a lengthy manuscript was reduced into a manual-styled script - officially co-authored with Rafael Gambra Ciudad and Francisco Puy Muñoz - ''¿Qué es el carlismo?'' (1971), with late re-workings and compilations published either shortly before death or posthumously.

Tejada's works on theory of politics are visibly less numerous than those on theory of law or on history of political thought; moreover, some of them resemble political manifestos rather than scholarly writings. Preceded by caudillaje-oriented brochures of the late 1930s, the main body of his Traditionalism was laid out mostly in the 1950s, following activity in Academia Vazquez de Mella; its most complete and straightforward lecture was ''La monarquía tradicional'' (1954), though some, like ''El tradicionalismo político español'', remained in manuscript. The vision was further refined in details in the 1960s, especially during Congresses of Traditionalist Studies and systematically revisited in the early 1970s, mostly as result of political struggle taking place within Carlism: a lengthy manuscript was reduced into a manual-styled script - officially co-authored with Rafael Gambra Ciudad and Francisco Puy Muñoz - ''¿Qué es el carlismo?'' (1971), with late re-workings and compilations published either shortly before death or posthumously.

Some authors maintain that there were no Carlist antecedents in the Tejada family; however, records reveal that a Justiniano Elías de Tejada, though initially opposing neo-Catholic designs in the 1860s, in the early 1870s turned president of Junta Carlista de Castuera and was even subject to jokes because of that. Francisco himself claimed he had joined Comunión Tradicionalista at the age of 15, remained a Carlist during his adolescence and in 1936 returned from Germany to enlist to the Nationalist army responding to the call of his king, Alfonso Carlos, though he provided also conflicting or confusing accounts.

Nothing is known about Tejada political activity during the Civil War and soon afterwards; though seconded to a

Some authors maintain that there were no Carlist antecedents in the Tejada family; however, records reveal that a Justiniano Elías de Tejada, though initially opposing neo-Catholic designs in the 1860s, in the early 1870s turned president of Junta Carlista de Castuera and was even subject to jokes because of that. Francisco himself claimed he had joined Comunión Tradicionalista at the age of 15, remained a Carlist during his adolescence and in 1936 returned from Germany to enlist to the Nationalist army responding to the call of his king, Alfonso Carlos, though he provided also conflicting or confusing accounts.

Nothing is known about Tejada political activity during the Civil War and soon afterwards; though seconded to a  In the mid 1940s Tejada again neared Carlism, at that time with no king, divided into few factions and politically bewildered. First commencing co-operation with their periodicals, in the Madrid cafes he mixed with Carlists of different persuasions, including the pro-collaborationist Carloctavistas and the intransigent orthodox Javieristas; he also took part in their minor public manifestations against the regime. In unspecified circumstances, though most likely acting in agreement if not on request of the then Carlist political leader Manuel Fal Conde, Tejada ventured to co-organize a semi-official Traditionalist cultural network, which materialized as the Madrid Academia Vázquez de Mella; in the late 1940s he was among its most active lecturers. Now openly confronting the regime and in 1947 advocating a "no" vote in the Ley de Sucesión referendum, politically Tejada avoided clear identification with any of the Carlist groupings. He seemed closest to supporters of Dom Duarte Nuño de Braganza as a potential Carlist heir; according to other sources he merely considered the Portuguese claimant a viable candidate. The period of vacillation ended in 1950, when Tejada aligned with the Javieristas and accepted seat in their national executive, in 1951 nominated by Don Javier commissioner of Comunión Tradicionalista external affairs.

In the mid 1940s Tejada again neared Carlism, at that time with no king, divided into few factions and politically bewildered. First commencing co-operation with their periodicals, in the Madrid cafes he mixed with Carlists of different persuasions, including the pro-collaborationist Carloctavistas and the intransigent orthodox Javieristas; he also took part in their minor public manifestations against the regime. In unspecified circumstances, though most likely acting in agreement if not on request of the then Carlist political leader Manuel Fal Conde, Tejada ventured to co-organize a semi-official Traditionalist cultural network, which materialized as the Madrid Academia Vázquez de Mella; in the late 1940s he was among its most active lecturers. Now openly confronting the regime and in 1947 advocating a "no" vote in the Ley de Sucesión referendum, politically Tejada avoided clear identification with any of the Carlist groupings. He seemed closest to supporters of Dom Duarte Nuño de Braganza as a potential Carlist heir; according to other sources he merely considered the Portuguese claimant a viable candidate. The period of vacillation ended in 1950, when Tejada aligned with the Javieristas and accepted seat in their national executive, in 1951 nominated by Don Javier commissioner of Comunión Tradicionalista external affairs.

In the early 1950s Tejada got firmly engaged in mainstream Carlism and demonstrated an uncompromising political stand. He lambasted the dissenting Carloctavistas, complained to Fal about permissive, increasingly

In the early 1950s Tejada got firmly engaged in mainstream Carlism and demonstrated an uncompromising political stand. He lambasted the dissenting Carloctavistas, complained to Fal about permissive, increasingly  Having moved on longtime scientific research mission to Italy, at the turn of the decades Tejada was getting increasingly detached from daily Carlist politics. Within the Secretariat and numerous cultural outposts he was somewhat sidetracked by a new breed of young activists forming the entourage of prince Carlos Hugo. Though he knew some, especially their leader Ramón Massó, from the Academia Vázquez de Mella years of the 1940s, Tejada developed grave doubts about Carlist orthodoxy and genuine intentions of the hugocarlistas, suspecting them of pursuing a hidden agenda. Co-operation deteriorated into crisis and then open conflict in the early 1960s, when Don Carlos Hugo started to sidetrack most hard-line Traditionalists. Tejada did not illude himself about Don Javier potentially confronting his progressist son, and in July 1962 he decided to break with the Borbón-Parmas; some authors claim that he was expulsed. He declared to Don Carlos Hugo that he could not make him king, but could prevent him from becoming one. In 1963 Tejada already referred to Don Carlos Hugo as "este aventurero francés de sangre bastarda".

Having moved on longtime scientific research mission to Italy, at the turn of the decades Tejada was getting increasingly detached from daily Carlist politics. Within the Secretariat and numerous cultural outposts he was somewhat sidetracked by a new breed of young activists forming the entourage of prince Carlos Hugo. Though he knew some, especially their leader Ramón Massó, from the Academia Vázquez de Mella years of the 1940s, Tejada developed grave doubts about Carlist orthodoxy and genuine intentions of the hugocarlistas, suspecting them of pursuing a hidden agenda. Co-operation deteriorated into crisis and then open conflict in the early 1960s, when Don Carlos Hugo started to sidetrack most hard-line Traditionalists. Tejada did not illude himself about Don Javier potentially confronting his progressist son, and in July 1962 he decided to break with the Borbón-Parmas; some authors claim that he was expulsed. He declared to Don Carlos Hugo that he could not make him king, but could prevent him from becoming one. In 1963 Tejada already referred to Don Carlos Hugo as "este aventurero francés de sangre bastarda".

After the breakup Tejada did not join any Carlist faction, though he was reportedly sympathetic to RENACE: he liked its format of depositary of Traditionalist values with no support for any specific claimant. He embarked on building a network of institutions marketing orthodox Traditionalism. In 1963 he co-founded the Madrid-based Centro de Estudios Históricos y Políticos General Zumalacárregui; though officially affiliated with Secretariado General de Movimiento Nacional, it was intended as a Carlist think-tank. Its activity climaxed in two Congresos de Estudios Tradicionalistas, staged in 1964 and 1968; Centro issued also periodicals and organized so-called Jornadas Forales across the country.

In the first half of the 1960s Tejada emerged as chief ideologue of Juntas de Defensa del Carlismo, network mushrooming across the country and united by opposition to hugocarlismo; he also contributed to launch of a new periodical, ''Siempre''. In mid-1960s Tejada was firmly established among leaders of loosely organized followers of orthodox Traditionalism; his activity was increasingly leaning towards vague dynastical compromise, intended to block the Borbón-Parmas; this strategy led him close to Carloctavistas and Sivattistas. In 1966 he supported referendum on Ley Organica, considering it a stepping stone towards a Traditionalist ideal; despite this, some scholars dub him "isolated anti-regime sniper". In 1968 Franco, always keen to exploit differences, received Tejada to discuss the monarchical question; during their only personal meeting, the dictator was treated to legitimist discourse reverting to the Braganza solution.

The turn of the decades spelled a political disaster for Tejada: the Alfonsist pretender was nominated as the future king and Carlism was firmly taken over by the hugocarlistas. On the official front, in 1972 he was trialed for anti-government remarks. On the Carlist front, his 1971 last-minute doctrinal summary, ''¿Qué es el carlismo?'', made the Traditionalist position crystal clear, but failed to prevent transformation of Javierismo into the socialist-dominated Partido Carlista. During last years of Francoism he witnessed and indeed contributed to increasing decomposition of Traditionalism. In 1972 he was skeptical about launching an anti-hugocarlista organization on the

After the breakup Tejada did not join any Carlist faction, though he was reportedly sympathetic to RENACE: he liked its format of depositary of Traditionalist values with no support for any specific claimant. He embarked on building a network of institutions marketing orthodox Traditionalism. In 1963 he co-founded the Madrid-based Centro de Estudios Históricos y Políticos General Zumalacárregui; though officially affiliated with Secretariado General de Movimiento Nacional, it was intended as a Carlist think-tank. Its activity climaxed in two Congresos de Estudios Tradicionalistas, staged in 1964 and 1968; Centro issued also periodicals and organized so-called Jornadas Forales across the country.

In the first half of the 1960s Tejada emerged as chief ideologue of Juntas de Defensa del Carlismo, network mushrooming across the country and united by opposition to hugocarlismo; he also contributed to launch of a new periodical, ''Siempre''. In mid-1960s Tejada was firmly established among leaders of loosely organized followers of orthodox Traditionalism; his activity was increasingly leaning towards vague dynastical compromise, intended to block the Borbón-Parmas; this strategy led him close to Carloctavistas and Sivattistas. In 1966 he supported referendum on Ley Organica, considering it a stepping stone towards a Traditionalist ideal; despite this, some scholars dub him "isolated anti-regime sniper". In 1968 Franco, always keen to exploit differences, received Tejada to discuss the monarchical question; during their only personal meeting, the dictator was treated to legitimist discourse reverting to the Braganza solution.

The turn of the decades spelled a political disaster for Tejada: the Alfonsist pretender was nominated as the future king and Carlism was firmly taken over by the hugocarlistas. On the official front, in 1972 he was trialed for anti-government remarks. On the Carlist front, his 1971 last-minute doctrinal summary, ''¿Qué es el carlismo?'', made the Traditionalist position crystal clear, but failed to prevent transformation of Javierismo into the socialist-dominated Partido Carlista. During last years of Francoism he witnessed and indeed contributed to increasing decomposition of Traditionalism. In 1972 he was skeptical about launching an anti-hugocarlista organization on the  In bitter public skirmishes with partisans of Partido Carlista, following death of Franco Tejada attempted to build a new Carlist organization, born in 1977 as Comunión Católico-Monárquica-Legitimista. During the electoral campaign it joined forces with Unión Nacional Española and

In bitter public skirmishes with partisans of Partido Carlista, following death of Franco Tejada attempted to build a new Carlist organization, born in 1977 as Comunión Católico-Monárquica-Legitimista. During the electoral campaign it joined forces with Unión Nacional Española and

In the post-war Spain Tejada gained prominence principally as a theorist of law; present day scholars either suggest that Francoist setting provided a favorable background for domination of iusnaturalismo against other schools, or bluntly claim that Neoescolástica was the regime's means of auto-legitimization, enforced and disguised as "pluralism". His writings on history of political thought were appreciated if could have been presented as picturing the regime as ultimate climax of Hispanic tradition, while Traditionalist theory of politics – acceptable in the 1950s – when assuming a decisively Carlist flavor was clearly unwelcome in the 1970s.

During and after the

In the post-war Spain Tejada gained prominence principally as a theorist of law; present day scholars either suggest that Francoist setting provided a favorable background for domination of iusnaturalismo against other schools, or bluntly claim that Neoescolástica was the regime's means of auto-legitimization, enforced and disguised as "pluralism". His writings on history of political thought were appreciated if could have been presented as picturing the regime as ultimate climax of Hispanic tradition, while Traditionalist theory of politics – acceptable in the 1950s – when assuming a decisively Carlist flavor was clearly unwelcome in the 1970s.

During and after the  General assessment of Tejada's scholarly standing seems far from agreed. Some point to his massive production and suggest that having been among greatest intellectuals of his time he led a school of his own, building a holistic "sistema tejadiano" or "pensamiento tejadiano". Others consider him either mostly a law theorist or mostly a student of Hispanidad. His followers point also to his charming personality and acknowledging massive erudition, call him a genius monster. Others suggest that he was a little-minded, vindictive, impossible to deal with bigot of an overgrown ego, his career enabled by anti-democratic nature of the Francoist regime, dubbed "reaccionario" and the passion of his life, "tradición española", referred to as "ni es tradición ni es española". In the compromise version, he is either presented as notable but second-rate representative of Traditionalism or as an erudite eminent for some of his case studies.Díaz Díaz 1998, p. 22

General assessment of Tejada's scholarly standing seems far from agreed. Some point to his massive production and suggest that having been among greatest intellectuals of his time he led a school of his own, building a holistic "sistema tejadiano" or "pensamiento tejadiano". Others consider him either mostly a law theorist or mostly a student of Hispanidad. His followers point also to his charming personality and acknowledging massive erudition, call him a genius monster. Others suggest that he was a little-minded, vindictive, impossible to deal with bigot of an overgrown ego, his career enabled by anti-democratic nature of the Francoist regime, dubbed "reaccionario" and the passion of his life, "tradición española", referred to as "ni es tradición ni es española". In the compromise version, he is either presented as notable but second-rate representative of Traditionalism or as an erudite eminent for some of his case studies.Díaz Díaz 1998, p. 22

Elias de Tejada at ''UC3M'' service

de Tejada foundation

Centro de Estudios General Zumalacarregui

Consejo de Estudios Hispanicos

collection of minor de Tejada's pieces at Fundacion Larramendi

minor Elias de Tejada pieces and some works on him on ''Dialnet Unirioja'' service

''¿Que es el carlismo?'' by Elías and others

*

''Por Dios y por España''; contemporary Carlist propaganda

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tejada y Spinola, Francisco Elias de Carlists Corporatism Writers from Extremadura Francoist Spain 20th-century Spanish historians Spanish landowners Roman Catholic writers Spanish essayists Spanish male writers Spanish monarchists Spanish military personnel of the Spanish Civil War (National faction) Spanish philosophers Spanish politicians Spanish Roman Catholics Spanish victims of crime 20th-century Spanish lawyers Male essayists Academic staff of the University of Salamanca

Carlist

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty – one descended from Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855) – ...

politician. He is considered one of top intellectuals of the Francoist era, though not necessarily of Francoism

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spai ...

. As theorist of law he represented the school known as '' iusnaturalismo'', as historian of political ideas he focused mostly on Hispanidad

''Hispanidad'' (, en, Hispanicity,) is a Spanish term alluding to the group of people, countries, and communities that share the Spanish language and Hispanic culture. The term can have various, different implications and meanings depending on ...

, and as theorist of politics he pursued a Traditionalist approach. As a Carlist he remained an ideologue rather than a political protagonist.

Family and youth

The Tejada family originated from

The Tejada family originated from Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

; its branch moved to Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

and in the late Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

to the Spanish La Rioja

La Rioja () is an autonomous community and province in Spain, in the north of the Iberian Peninsula. Its capital is Logroño. Other cities and towns in the province include Calahorra, Arnedo, Alfaro, Haro, Santo Domingo de la Calzada, an ...

, settling at Muro de Cameros. In the early modern period

The term modern period or modern era (sometimes also called modern history or modern times) is the period of history that succeeds the Middle Ages (which ended approximately 1500 AD). This terminology is a historical periodization that is applie ...

its descendants transferred to Extremadura

Extremadura (; ext, Estremaúra; pt, Estremadura; Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is an autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central-western part of the Iberian Peninsula, it ...

and few generations later they were already considered extremeños. Francisco's distant ancestor was the 17th-century knight Sancho de Tejada, whose son Elías excelled during the siege of Breda and got his name incorporated into the family surname. In the early 19th century the family, referred to as terratenientes hidalgos, held estates mostly in Castuera and Zalamea de la Serena. Francisco's grandfather made his name as a lawyer. Francisco's father, José Maria Elías de Tejada y de la Cueva (1891-1970), also practiced as abogado in Castuera. In 1913 he married Encarnación Spínola Gómez (1891-1953), heir to a wealthy local landowners family. It was at her Rinconada estate near Granja de Torrehermosa where Francisco and his only brother spent most of their childhood, raised in the profoundly Catholic ambience. Though born in Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the Largest cities of the Europ ...

, he considered Extremadura his mother region.

Since early childhood consuming sophisticated books and gifted with excellent memory, the young Francisco was first educated in the Jesuit college of Nuestra Señora de Recuerdo in the Madrid quarter of Chamartin. After its premises were ransacked in May 1931 and the order was expulsed soon afterwards, he continued his learning in the Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

Estremoz

Estremoz () is a municipality in Portugal. The population in 2011 was 14,318, in an area of 513.80 km². The city Estremoz itself had a population of 7,682 in 2001. It is located in the Alentejo region.

History

The region around Estremoz ...

, still with the Jesuits. In 1933 Tejada obtained bachillerato

The Spanish Baccalaureate ( es, Bachillerato) is the post-16 stage of education in Spain, comparable to the A Levels/Higher (Scottish) in the UK, the French Baccalaureate in France or the International Baccalaureate. It follows the ESO (compulso ...

, nostrified by University of Seville

The University of Seville (''Universidad de Sevilla'') is a university in Seville, Spain. Founded under the name of ''Colegio Santa María de Jesús'' in 1505, it has a present student body of over 69.200, and is one of the top-ranked universi ...

. Inspired by his Jesuit mentor Fernando María de Huidobro he decided to study law, though at Universidad Central in Madrid he pursued also philosophy and letters. Having graduated in both in 1935 he left to study in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. Outbreak of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

caught him in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

; Tejada returned to Spain to learn that tens of his relatives were executed by the Republicans in Granja. In September in Calera de la Sierra he enlisted to Nationalist troops, first advancing to Toledo and then as artillery man serving during the battle of Madrid

The siege of Madrid was a two-and-a-half-year siege of the Republican-controlled Spanish capital city of Madrid by the Nationalist armies, under General Francisco Franco, during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). The city, besieged from Octo ...

. In February 1937 he was admitted to Alféreces Provisionales school in Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

, soon abandoned due to health reasons. In May 1937 he intended to join aviation, but in August he was nominated alférez asimilado at a logistics unit in Seville, remaining at this post until the end of the war.

Though described as heavily attracted to females, Elías de Tejada married as late as in 1962, at the age of 45. He wed an Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

20 years his junior, Gabriella Pèrcopo Calet (1937-1986), descendant to a distinguished Neapolitan family of immense intellectual heritage, fluent in Spanish, perfectly familiar with the Spanish cultural realm and the PhD herself. Throughout the rest of his life she supported Tejada on all possible fields, as a secretary, proofreader

Proofreading is the reading of a galley proof or an electronic copy of a publication to find and correct reproduction errors of text or art. Proofreading is the final step in the editorial cycle before publication.

Professional

Traditiona ...

, editor, erudite partner, co-author, organizer, academic inspiration and a soul mate. The couple had no children. Francisco Elías de Tejada Lozano, a Spanish diplomat in the 21st century serving as ambassador and high Foreign Ministry official, is descendant to Elías’ brother.

Academic career

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

.

In March 1941 Tejada won the contest for chair of Derecho Natural y Filosofía del Derecho in Murcia

Murcia (, , ) is a city in south-eastern Spain, the capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of the Region of Murcia, and the seventh largest city in the country. It has a population of 460,349 inhabitants in 2021 (about one ...

; in 1942 he moved to Salamanca

Salamanca () is a city in western Spain and is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the autonomous community of Castile and León. The city lies on several rolling hills by the Tormes River. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO World Herit ...

, having been the only contender. In 1951 he swapped chairs with Joaquín Ruiz Giménez Cortés and left for Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

, where he headed philosophy of law for the next 26 years, periodically chairing also the history of ideas. However, except the 1960-1961 course he spent the 1956-1964 period mostly pursuing research in Naples, with massive admin gimmicks on part of the University to find a legal framework for such a lengthy stay. Since 1964 he worked under the dedicación exclusiva contract. In 1969 nominated consejero honorario del Consejo Nacional de Educación, though his academic relations with the Francoist education authorities remained thorny.

doctor honoris causa

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad ho ...

titles, a vastly prolific author and during his lifetime himself subject of 4 PhD dissertations, Tejada did not make it to the top elite of Spanish law scholars and did not enter Real Academia de Jurisprudencia y Legislación. There are conflicting accounts of his standing in the academic realm. Some claim that he was universally highly regarded as doctrinally intransigent but pro-student open-minded, tolerant scholar, as demonstrated by his supervision of PhD bid of Enrique Tierno Galván, the future key PSOE

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español ; PSOE ) is a social-democraticThe PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* political party in Spain. The PSOE has been in gov ...

politician. Others present him as a feared ”inquisidor”, extremely quarrelsome hypocrite pursuing private goals and eager to call security when dealing with manifestations of student dissent towards him.

Theorist of law

Tejada is considered member of the natural law school and its key representative during the Franco era, influenced by early modern Spanish jurists like Francisco Suarez but mostly following the

Tejada is considered member of the natural law school and its key representative during the Franco era, influenced by early modern Spanish jurists like Francisco Suarez but mostly following the Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known ...

; he regarded own work merely a gloss to the opus of St. Thomas. Hence, within iusnaturalismo he is classified as representative of Neo-Scholastic school, as opposed to Axiological, Neo-Kantian and Innovative Natural Law schools. Together with Michel Villey deemed a renovator of classical European iusnaturalismo of the mid-20th century, Tejada clearly distinguished own vision from "iusnaturalismo racionalista". Within this framework, he agreed that the role of jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

was discovering rather than inventing.

Tejada's work consisted of systematizing concepts falling into ontology

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exi ...

, anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of be ...

, logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premise ...

and axiology. His original contribution was merging them into a complete system and introducing a set of own concepts. He is considered not a mere follower but a scholar who developed Thomist juridical philosophy, credited for attempting a synthesis with existentialist school; some even view him as representative of legal Catholic Existentialism, a definition not accepted universally. He is noted as the moving spirit behind emergence of Asociación Internacional de Iusnaturalistas Hispánicos "Felipe II". Last but not least, Tejada is acknowledged as the one who inspired a number of scholars, both in Spain and in wider Hispanic realm, though not all his proposals have been accepted by his followers.

For Tejada the law resulted from God assuming a decisive role, but rendering it possible to find acceptable reasons for an objective-value-based human agency; natural law stemmed from conjunction of divine power and human liberty. Its purpose was twofold: salvation and vocation, corresponding to justice in relations to God and security in relations to other people. Though some scholars point to some confusion as to the terms used, most agree that for Tejada law was "la norma política con contenido justo", colloquially described as where politics and ethics overlapped, a sovereign normative system related but clearly separate from religion. Some students conclude that Tejada was close to normativism, others find this suggestion too restrictive and claim that for him, law was far more than a norm. A distinctive thread of his jurisprudential discourse was its application to vastly distinct cultural realms, though he attempted to sublimate a specific Hispanic natural law.

Tejada kept writing on theory of law throughout all of his academic career; his first contribution was published in 1942 and his new pieces are being published posthumously. Except two volumes of ''Historia de la filosofía del derecho y del Estado'' (1946), until the very late of his life Tejada's works were mostly articles in specialized reviews, lectures delivered at jurisprudential conferences or compendium-like textbooks intended for students. Tejada's vastly erudite opus magnum, a systematic in-depth lecture gathering all his ideas on law theory was ''Tratado de filosofia del derecho'', published in Seville in two volumes respectively in 1974 and 1977. It is not clear how many of his almost 400 works fall into theory of law, though their number might near one hundred.

For Tejada the law resulted from God assuming a decisive role, but rendering it possible to find acceptable reasons for an objective-value-based human agency; natural law stemmed from conjunction of divine power and human liberty. Its purpose was twofold: salvation and vocation, corresponding to justice in relations to God and security in relations to other people. Though some scholars point to some confusion as to the terms used, most agree that for Tejada law was "la norma política con contenido justo", colloquially described as where politics and ethics overlapped, a sovereign normative system related but clearly separate from religion. Some students conclude that Tejada was close to normativism, others find this suggestion too restrictive and claim that for him, law was far more than a norm. A distinctive thread of his jurisprudential discourse was its application to vastly distinct cultural realms, though he attempted to sublimate a specific Hispanic natural law.

Tejada kept writing on theory of law throughout all of his academic career; his first contribution was published in 1942 and his new pieces are being published posthumously. Except two volumes of ''Historia de la filosofía del derecho y del Estado'' (1946), until the very late of his life Tejada's works were mostly articles in specialized reviews, lectures delivered at jurisprudential conferences or compendium-like textbooks intended for students. Tejada's vastly erudite opus magnum, a systematic in-depth lecture gathering all his ideas on law theory was ''Tratado de filosofia del derecho'', published in Seville in two volumes respectively in 1974 and 1977. It is not clear how many of his almost 400 works fall into theory of law, though their number might near one hundred.

Historian of political thought

Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the nort ...

, Navarre, Vascongadas, Extremadura, Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

and Galicia, produced works intended as synthetic accounts for Spain and Portugal, dedicated separate works to Franche-Comté, Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

, Naples, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

and Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and wrote on Hispanic Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

and California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, Portuguese holdings in Africa and Asia, the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, Colombia and Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

in general. However, his comparatistic zeal made him discuss history of political thought also beyond the Lusitanic

Lusitanic is a term used to refer to people who share the linguistic and cultural traditions of the Portuguese-speaking nations, territories, and populations, including Portugal, Brazil, Madeira, Macau, Timor-Leste, Azores, Angola, Mozambique ...

and Hispanic realm, e.g. in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

and Sephardic traditions, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

, Sweden, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

, Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

, Japan, Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

, Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and ea ...

, Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

, Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi ...

and elsewhere.

Tejada strove to reconstruct and define a Hispanic political tradition and vacillated between the role of historian and theorist. His understanding of Hispanidad was based on the concept of Las Españas, seen as embodied in confederal political shape but its essence having been pre-state commonality. Relying on the unity in diversity

Unity in diversity is used as an expression of harmony and unity between dissimilar individuals or groups. It is a concept of "unity without uniformity and diversity without fragmentation" that shifts focus from unity based on a mere tolerance ...

recipé and incorporating local traditions, including the fueros

(), (), () or () is a Spanish legal term and concept. The word comes from Latin , an open space used as a market, tribunal and meeting place. The same Latin root is the origin of the French terms and , and the Portuguese terms and ; all ...

, Hispanic tradition consisted of two features: Catholic vision of life combined with missionary universalist spirit pursued by a federative monarchy. According to Tejada Hispanidad was born in the Middle Ages, climaxed during the early España de los Austrias and declined due to centralist French tradition imported by the Borbones. His recurring subject was confronting Hispanic and European traditions, the latter born out of anti-Catholic, revolutionary, modernist thought and ultimately responsible for breaking the Hispanic community by force.

Tejada understood political thought as a vehicle of sustaining tradition and ignored the imperial and ethnic dimensions of Hispanidad. He viewed the Hispanic political community as forged by will of the people forming its components, not as a result of conquest. Ethnic features were merely means of transmitting heritage and a nation was defined as commonality of tradition, as opposed to positivist definitions focusing on features like language, geography, regime etc.; it enabled implantation of Hispanidad in vastly different settings of the Philippines,

Tejada understood political thought as a vehicle of sustaining tradition and ignored the imperial and ethnic dimensions of Hispanidad. He viewed the Hispanic political community as forged by will of the people forming its components, not as a result of conquest. Ethnic features were merely means of transmitting heritage and a nation was defined as commonality of tradition, as opposed to positivist definitions focusing on features like language, geography, regime etc.; it enabled implantation of Hispanidad in vastly different settings of the Philippines, Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

or Franche-Comté. Tejada saw the Hispanic tradition against a decisively providential background, e.g. when confronting Islam, Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

or the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

; scholars saw this approach as indebted to the vision of Giambattista Vico

Giambattista Vico (born Giovan Battista Vico ; ; 23 June 1668 – 23 January 1744) was an Italian philosopher, rhetorician, historian, and jurist during the Italian Enlightenment. He criticized the expansion and development of modern rationali ...

. Another frequently applied personal comparison was that to Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo: the two shared passion for Hispanic patrimony, massive erudition, reconstructive profile and Traditionalist leaning; Tejada's approach is dubbed "menéndezpelayismo".

Tejada's first work on history of political thought appeared in 1937 and the last ones in 1977. Unlike in case of theory of law, he did not produce a synthesis which would stand out; his thought is scattered across countless books, articles or minor opuscolos. Single works to be listed first are perhaps case studies, the monumental ''Nápoles hispánico'' (1958-1964) and an unfinished ''Historia del pensamiento político catalán'' (1963-1965). Publications attempting more general overview to be named are ''La causa diferenciadora de las comunidades políticas'' (1943), ''Las Españas'' (1948) and ''Historia de la literatura política en las Españas'' (1952, published 1991).

Theorist of politics

Initially Tejada developed a Hispanidad-oriented leadership theory of

Initially Tejada developed a Hispanidad-oriented leadership theory of authoritarian state

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic voti ...

; according to some in the early 1940s he performed a volte-face becoming a vehement anti-Francoist, according to the others during decades to come his theory was progressively dissociated from Francoism, some see 3 phases of his evolution and some advance rambling summaries. Some scholars highlight 1938-1940 works and consider him „superfascista”, most students tend to downplay caudillaje-related writings and focusing on the 1942-1978 period see Tejada as a Traditionalist; few advance an in-between option of "franquismo neotradicionalista". Among those supporting the Traditionalist tag many consider him "maximo representante del pensamiento tradicionalista español en la segunda mitad del siglo XX" or at least one of the key ones, though some present him as a second-rank theorist.

Tejada perceived Traditionalism as a unique Spanish response to the 1515-1648 rupture in European political thought; the latter afterwards degenerated into absolutism, liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

, totalitarism, and most recently into secular, parliamentarian, free-market, nation-state democracies

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose go ...

. Traditionalism itself was politically best embodied in Carlism. Its essence was threefold. First, it consisted of Catholic unity; some scholars claim that Tejada was opposed to religious liberty, others maintain that he was opposed to equality of faiths and advocated a state-endorsed Catholic orthodoxy. Second, it embraced historical, social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

, accountable, representative

Representative may refer to:

Politics

* Representative democracy, type of democracy in which elected officials represent a group of people

* House of Representatives, legislative body in various countries or sub-national entities

* Legislator, som ...

, foral

200px, Foral of Castro Verde - Portugal

The word ''foral'' ({{IPA-pt, fuˈɾaɫ, eu, plural: ''forais'') is a noun derived from the Portuguese word ''foro'', ultimately from Latin ''forum'', equivalent to Spanish ''fuero'', Galician '' foro'', ...

, federative, missionary

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

, organic and hereditary monarchy. Third, it was based on a subsidiary state model. The latter marked total reversal from original Tejada's penchant for omnipotent leadership and reflected the Traditionalist logic of state serving society, society serving man, and man serving God. A de-centralized withdrawn state, with its functions reduced, is to provide merely a framework for communities making it up, developed historically and safeguarded by separate legal establishments; The communities in question are to be governed by autonomous intermediary bodies and should participate in state politics represented in the Cortes

Cortes, Cortés, Cortês, Corts, or Cortès may refer to:

People

* Cortes (surname), including a list of people with the name

** Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), a Spanish conquistador

Places

* Cortes, Navarre, a village in the South border of ...

by delegates of various "gremios, hermandades, agrupaciones, cámaras, comunidades y cofradías"; Tejada juxtaposed Spanish communitarian fueros against the French individual liberties. According to some, the proposal advanced by Tejada was intended as a discussion how Spain should look like after Franco.

Carlist: around Francoism (1936-1950)

Some authors maintain that there were no Carlist antecedents in the Tejada family; however, records reveal that a Justiniano Elías de Tejada, though initially opposing neo-Catholic designs in the 1860s, in the early 1870s turned president of Junta Carlista de Castuera and was even subject to jokes because of that. Francisco himself claimed he had joined Comunión Tradicionalista at the age of 15, remained a Carlist during his adolescence and in 1936 returned from Germany to enlist to the Nationalist army responding to the call of his king, Alfonso Carlos, though he provided also conflicting or confusing accounts.

Nothing is known about Tejada political activity during the Civil War and soon afterwards; though seconded to a

Some authors maintain that there were no Carlist antecedents in the Tejada family; however, records reveal that a Justiniano Elías de Tejada, though initially opposing neo-Catholic designs in the 1860s, in the early 1870s turned president of Junta Carlista de Castuera and was even subject to jokes because of that. Francisco himself claimed he had joined Comunión Tradicionalista at the age of 15, remained a Carlist during his adolescence and in 1936 returned from Germany to enlist to the Nationalist army responding to the call of his king, Alfonso Carlos, though he provided also conflicting or confusing accounts.

Nothing is known about Tejada political activity during the Civil War and soon afterwards; though seconded to a Falangist

Falangism ( es, falangismo) was the political ideology of two political parties in Spain that were known as the Falange, namely first the Falange Española de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FE de las JONS) and afterwards the Fal ...

unit, he is not mentioned as engaged in Carlist, Falangist or other party structures until the early 1940s. However, his writings published in 1938-1939 clearly identified him as enthusiast of national syndicalism

National syndicalism is a far-right adaptation of syndicalism to suit the broader agenda of integral nationalism. National syndicalism developed in France in the early 20th century, and then spread to Italy, Spain, and Portugal. It is general ...

and the caudillaje system; some consider him concerned primarily with justifying the regime. He admitted great juvenile admiration for Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

. It was the second stay in Germany in 1940 that got him disillusioned with omnipotent state and single party; his 1940 article discussing caudillaje was notably tuned down and introduced a cautious tone. In the early 1940s he was assuming an increasingly dissenting stance. In 1942 he referred to "misería" of the Francoist system; the same year he was briefly detained for opposing subscriptions to División Azul. Though he had no chance to publish writings lambasting the system as anti-Catholic tyranny, Tejada made little secret of his views and in the Salamanca law faculty he voted against granting Franco doctorado honoris causa. In 1944 a Falangist

Falangism ( es, falangismo) was the political ideology of two political parties in Spain that were known as the Falange, namely first the Falange Española de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FE de las JONS) and afterwards the Fal ...

hit-squad stormed into his house, dragged him to the nearby Retiro park

The Buen Retiro Park (Spanish: ''Parque del Buen Retiro'', literally "Good retirement park"), Retiro Park or simply El Retiro is one of the largest parks of the city of Madrid, Spain. The park belonged to the Spanish Monarchy until the late 19th ...

and left him beaten unconscious.

In the mid 1940s Tejada again neared Carlism, at that time with no king, divided into few factions and politically bewildered. First commencing co-operation with their periodicals, in the Madrid cafes he mixed with Carlists of different persuasions, including the pro-collaborationist Carloctavistas and the intransigent orthodox Javieristas; he also took part in their minor public manifestations against the regime. In unspecified circumstances, though most likely acting in agreement if not on request of the then Carlist political leader Manuel Fal Conde, Tejada ventured to co-organize a semi-official Traditionalist cultural network, which materialized as the Madrid Academia Vázquez de Mella; in the late 1940s he was among its most active lecturers. Now openly confronting the regime and in 1947 advocating a "no" vote in the Ley de Sucesión referendum, politically Tejada avoided clear identification with any of the Carlist groupings. He seemed closest to supporters of Dom Duarte Nuño de Braganza as a potential Carlist heir; according to other sources he merely considered the Portuguese claimant a viable candidate. The period of vacillation ended in 1950, when Tejada aligned with the Javieristas and accepted seat in their national executive, in 1951 nominated by Don Javier commissioner of Comunión Tradicionalista external affairs.

In the mid 1940s Tejada again neared Carlism, at that time with no king, divided into few factions and politically bewildered. First commencing co-operation with their periodicals, in the Madrid cafes he mixed with Carlists of different persuasions, including the pro-collaborationist Carloctavistas and the intransigent orthodox Javieristas; he also took part in their minor public manifestations against the regime. In unspecified circumstances, though most likely acting in agreement if not on request of the then Carlist political leader Manuel Fal Conde, Tejada ventured to co-organize a semi-official Traditionalist cultural network, which materialized as the Madrid Academia Vázquez de Mella; in the late 1940s he was among its most active lecturers. Now openly confronting the regime and in 1947 advocating a "no" vote in the Ley de Sucesión referendum, politically Tejada avoided clear identification with any of the Carlist groupings. He seemed closest to supporters of Dom Duarte Nuño de Braganza as a potential Carlist heir; according to other sources he merely considered the Portuguese claimant a viable candidate. The period of vacillation ended in 1950, when Tejada aligned with the Javieristas and accepted seat in their national executive, in 1951 nominated by Don Javier commissioner of Comunión Tradicionalista external affairs.

Carlist: ''Javierista'' (1950-1962)

Christian-Democratic

Christian democracy (sometimes named Centrist democracy) is a political ideology that emerged in 19th-century Europe under the influence of Catholic social teaching and neo-Calvinism.

It was conceived as a combination of modern democratic ...

profile of a semi-official Carlist daily ''Informaciones'', and advocated that Don Javier goes bold by terminating the long overdue regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

. He co-drafted ''Declaración de Barcelona'', the statement which was issued by Don Javier in 1952 and which indeed announced his own claim to the Carlist throne, though the episode is not entirely clear. With the 1954 publication of ''La monarquía tradicional'' Tejada became the top Carlist theorist; the same year within the party top body, Junta Nacional, he formed part of Comisión de Cultura y Propaganda. At that time he was considered among key politicians of Carlism.

When in 1955 Fal Conde was released from Jefatura and when Carlism abandoned intransigent opposition to the regime in favor of cautious co-operation, Tejada was left puzzled. He did not hesitate to voice his doubts about collaborative strategy advocated by the new leader Jose Maria Valiente, yet he decided to comply and accepted appointment to the newly formed Secretariat; moreover, at one point he suggested that the body be dissolved as ineffective and replaced by Valiente's personal jefatura. Executing the rapprochement policy he did not believe in its success and was getting increasingly frustrated by Franco's rejection of the Carlist offer. However, he readily engaged in new formats of activity, now permitted by the regime: Tejada was active in the Carlist publishing house Ediciones Montejurra and became its director, animated the elitist Traditionalist periodical ''Reconquista'', contributed to new periodicals like ''Azada y Asta'' and especially threw himself into organizing Círculos Culturales Vázquez de Mella, a semi-official Carlist institutional network. In 1960 he entered Comision de Cultura of the Carlist executive and advocated setting up an "Instituto de Estudios Jurídicos".

Having moved on longtime scientific research mission to Italy, at the turn of the decades Tejada was getting increasingly detached from daily Carlist politics. Within the Secretariat and numerous cultural outposts he was somewhat sidetracked by a new breed of young activists forming the entourage of prince Carlos Hugo. Though he knew some, especially their leader Ramón Massó, from the Academia Vázquez de Mella years of the 1940s, Tejada developed grave doubts about Carlist orthodoxy and genuine intentions of the hugocarlistas, suspecting them of pursuing a hidden agenda. Co-operation deteriorated into crisis and then open conflict in the early 1960s, when Don Carlos Hugo started to sidetrack most hard-line Traditionalists. Tejada did not illude himself about Don Javier potentially confronting his progressist son, and in July 1962 he decided to break with the Borbón-Parmas; some authors claim that he was expulsed. He declared to Don Carlos Hugo that he could not make him king, but could prevent him from becoming one. In 1963 Tejada already referred to Don Carlos Hugo as "este aventurero francés de sangre bastarda".

Having moved on longtime scientific research mission to Italy, at the turn of the decades Tejada was getting increasingly detached from daily Carlist politics. Within the Secretariat and numerous cultural outposts he was somewhat sidetracked by a new breed of young activists forming the entourage of prince Carlos Hugo. Though he knew some, especially their leader Ramón Massó, from the Academia Vázquez de Mella years of the 1940s, Tejada developed grave doubts about Carlist orthodoxy and genuine intentions of the hugocarlistas, suspecting them of pursuing a hidden agenda. Co-operation deteriorated into crisis and then open conflict in the early 1960s, when Don Carlos Hugo started to sidetrack most hard-line Traditionalists. Tejada did not illude himself about Don Javier potentially confronting his progressist son, and in July 1962 he decided to break with the Borbón-Parmas; some authors claim that he was expulsed. He declared to Don Carlos Hugo that he could not make him king, but could prevent him from becoming one. In 1963 Tejada already referred to Don Carlos Hugo as "este aventurero francés de sangre bastarda".

Carlist: fighting the progressists (1962-1978)

After the breakup Tejada did not join any Carlist faction, though he was reportedly sympathetic to RENACE: he liked its format of depositary of Traditionalist values with no support for any specific claimant. He embarked on building a network of institutions marketing orthodox Traditionalism. In 1963 he co-founded the Madrid-based Centro de Estudios Históricos y Políticos General Zumalacárregui; though officially affiliated with Secretariado General de Movimiento Nacional, it was intended as a Carlist think-tank. Its activity climaxed in two Congresos de Estudios Tradicionalistas, staged in 1964 and 1968; Centro issued also periodicals and organized so-called Jornadas Forales across the country.

In the first half of the 1960s Tejada emerged as chief ideologue of Juntas de Defensa del Carlismo, network mushrooming across the country and united by opposition to hugocarlismo; he also contributed to launch of a new periodical, ''Siempre''. In mid-1960s Tejada was firmly established among leaders of loosely organized followers of orthodox Traditionalism; his activity was increasingly leaning towards vague dynastical compromise, intended to block the Borbón-Parmas; this strategy led him close to Carloctavistas and Sivattistas. In 1966 he supported referendum on Ley Organica, considering it a stepping stone towards a Traditionalist ideal; despite this, some scholars dub him "isolated anti-regime sniper". In 1968 Franco, always keen to exploit differences, received Tejada to discuss the monarchical question; during their only personal meeting, the dictator was treated to legitimist discourse reverting to the Braganza solution.

The turn of the decades spelled a political disaster for Tejada: the Alfonsist pretender was nominated as the future king and Carlism was firmly taken over by the hugocarlistas. On the official front, in 1972 he was trialed for anti-government remarks. On the Carlist front, his 1971 last-minute doctrinal summary, ''¿Qué es el carlismo?'', made the Traditionalist position crystal clear, but failed to prevent transformation of Javierismo into the socialist-dominated Partido Carlista. During last years of Francoism he witnessed and indeed contributed to increasing decomposition of Traditionalism. In 1972 he was skeptical about launching an anti-hugocarlista organization on the

After the breakup Tejada did not join any Carlist faction, though he was reportedly sympathetic to RENACE: he liked its format of depositary of Traditionalist values with no support for any specific claimant. He embarked on building a network of institutions marketing orthodox Traditionalism. In 1963 he co-founded the Madrid-based Centro de Estudios Históricos y Políticos General Zumalacárregui; though officially affiliated with Secretariado General de Movimiento Nacional, it was intended as a Carlist think-tank. Its activity climaxed in two Congresos de Estudios Tradicionalistas, staged in 1964 and 1968; Centro issued also periodicals and organized so-called Jornadas Forales across the country.

In the first half of the 1960s Tejada emerged as chief ideologue of Juntas de Defensa del Carlismo, network mushrooming across the country and united by opposition to hugocarlismo; he also contributed to launch of a new periodical, ''Siempre''. In mid-1960s Tejada was firmly established among leaders of loosely organized followers of orthodox Traditionalism; his activity was increasingly leaning towards vague dynastical compromise, intended to block the Borbón-Parmas; this strategy led him close to Carloctavistas and Sivattistas. In 1966 he supported referendum on Ley Organica, considering it a stepping stone towards a Traditionalist ideal; despite this, some scholars dub him "isolated anti-regime sniper". In 1968 Franco, always keen to exploit differences, received Tejada to discuss the monarchical question; during their only personal meeting, the dictator was treated to legitimist discourse reverting to the Braganza solution.

The turn of the decades spelled a political disaster for Tejada: the Alfonsist pretender was nominated as the future king and Carlism was firmly taken over by the hugocarlistas. On the official front, in 1972 he was trialed for anti-government remarks. On the Carlist front, his 1971 last-minute doctrinal summary, ''¿Qué es el carlismo?'', made the Traditionalist position crystal clear, but failed to prevent transformation of Javierismo into the socialist-dominated Partido Carlista. During last years of Francoism he witnessed and indeed contributed to increasing decomposition of Traditionalism. In 1972 he was skeptical about launching an anti-hugocarlista organization on the Requeté

The Requeté () was a Carlist organization, at times with paramilitary units, that operated between the mid-1900s and the early 1970s, though exact dates are not clear.

The Requeté formula differed over the decades, and according to its chan ...

basis and ridiculed its leaders, attracting some criticism in return. However, he engaged in another anti-hugocarlista initiative, Real Tercio de Requetés de Castilla, and neared the youngest of the Borbón-Parmas, Don Sixto, considered even his intellectual mentor. In 1975 he accepted Don Sixto as royal leader, though neither as a claimant nor regent but as a vaguely styled "abanderado de la Tradición".

In bitter public skirmishes with partisans of Partido Carlista, following death of Franco Tejada attempted to build a new Carlist organization, born in 1977 as Comunión Católico-Monárquica-Legitimista. During the electoral campaign it joined forces with Unión Nacional Española and