Foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The main issues of the

The main issues of the

The Second World War dramatically upended the international system, as formerly-powerful nations like Germany, France, Japan, and even Britain had been devastated. At the end of the war, only the United States and the Soviet Union had the ability to exercise influence, and a bipolar international power structure replaced the multipolar structure of the

The Second World War dramatically upended the international system, as formerly-powerful nations like Germany, France, Japan, and even Britain had been devastated. At the end of the war, only the United States and the Soviet Union had the ability to exercise influence, and a bipolar international power structure replaced the multipolar structure of the

The

The

Rising tensions with the Soviets, along with the Soviet veto of numerous

Rising tensions with the Soviets, along with the Soviet veto of numerous

Truman had long been sympathetic to the Jewish community in Kansas City. Regarding British-controlled

Truman had long been sympathetic to the Jewish community in Kansas City. Regarding British-controlled

online

/ref> Along with the Soviet detonation of a nuclear weapon, the Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War played a major role in escalating Cold War tensions and U.S. militarization during 1949. Truman would have been willing to maintain some relationship with the new government, but Mao was unwilling. Chiang established the

Following World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union occupied

Following World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union occupied

As the UN forces approached the Yalu River, the CIA and General MacArthur both expected that the Chinese would remain out of the war. Defying those predictions, Chinese People's Volunteer Army forces crossed the Yalu River in November 1950 and forced the overstretched UN soldiers to retreat. Fearing that the escalation of the war could spark a global conflict with the Soviet Union, Truman refused MacArthur's request to bomb Chinese supply bases north of the Yalu River. UN forces were pushed below the 38th parallel before the end of 1950, but, under the command of General

As the UN forces approached the Yalu River, the CIA and General MacArthur both expected that the Chinese would remain out of the war. Defying those predictions, Chinese People's Volunteer Army forces crossed the Yalu River in November 1950 and forced the overstretched UN soldiers to retreat. Fearing that the escalation of the war could spark a global conflict with the Soviet Union, Truman refused MacArthur's request to bomb Chinese supply bases north of the Yalu River. UN forces were pushed below the 38th parallel before the end of 1950, but, under the command of General

Scholars have on average

Scholars have on average

excerpt

* * Congressional Quarterly. ''Congress and the Nation; a review of government and politics in the postwar years: 1945–1984'' (1965

online

* * * * * * * * * * *

online

a major scholarly study * Beisner, Robert L. "Patterns of Peril: Dean Acheson Joins the Cold Warriors, 1945–46". ''Diplomatic History'' 1996 20(3): 321–355

online

* Benson, Michael T. ''Harry S. Truman and the founding of Israel'' (Greenwood, 1997). * Bernstein, Barton J. "The quest for security: American foreign policy and international control of atomic energy, 1942–1946". ''Journal of American History'' 60.4 (1974): 1003–104

online

* Beschloss, Michael R. ''The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941–1945'' (2003

excerpt

* * Borstelmann, Thomas. "Jim crow's coming out: Race relations and American foreign policy in the Truman years". ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 29.3 (1999): 549–569

online

* Bostdorff, Denise M. ''Proclaiming the Truman Doctrine: The Cold War Call to Arms'' (2008

excerpt

* Brinkley, Douglas, ed. ''Dean Acheson and the Making of U.S. Foreign Policy''. 1993. 271 pp. essays by scholars * Bryan, Ferald J. "George C. Marshall at Harvard: A Study of the Origins and Construction of the 'Marshall Plan' Speech". ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' (1991): 489–502

Online

* Campbell, John C. ''The United States in World Affairs, 1945–1947'' (Harper and Council on Foreign Relations. 1947), 585 pp; comprehensive coverage of all major issues. ** Campbell, John C. ''The United States in World Affairs, 1947–1949'' (Harper and Council on Foreign Relations. 1949), 600 pp; comprehensive coverage of all major issues

online

** Campbell, John C. ''The United States in World Affairs, 1948–1949'' (Harper and Council on Foreign Relations. 1949), 604 pp; comprehensive coverage of all major issues. ** Stebbins, Richard P. ''The United States in World Affairs, 1949'' (Harper and Council on Foreign Relations. 1950), 430 pp; annual for 1949–1953. Detailed global coverage. * * Chace, James. ''Acheson: The Secretary of State Who Created the American World''. (1998). 512 pp

online

* Davis, Lynn Etheridge. ''The Cold War Begins: Soviet-American Conflict Over East Europe'' (Princeton University Press, 2015. * Divine, Robert A. "The Cold War and the Election of 1948", ''The Journal of American History'', Vol. 59, No. 1 (Jun. 1972), pp. 90–11

in JSTOR

* Dobbs, Michael. ''Six Months in 1945: FDR, Stalin, Churchill, and Truman—from World War to Cold War'' (2012) popular narrative * * Edwards, Jason A. "Sanctioning foreign policy: The rhetorical use of President Harry Truman". ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 39.3 (2009): 454–472

online

* Edwards, Lee. "Congress and the Origins of the Cold War: The Truman Doctrine", ''World Affairs'', Vol. 151, 198

online edition

* * Feis, Herbert. ''Japan Subdued; the Atomic Bomb and the End of the War in the Pacific'' (1961

online

* Feis, Herbert. ''Between War and Peace: The Potsdam Conference'' (1960), Pulitzer Priz

Online

* Feis, Herbert. ''From Trust to Terror; the Onset of the Cold War, 1945–1950'' (1970

online

* Feis, Herbert. ''The China Tangle; the American Effort in China from Pearl Harbor to the Marshall Mission'' (1965

online

* Feis, Herbert. ''The Birth of Israel: The Tousled Diplomatic Bed'' (1969

online

* Feis, Herbert. ''Contest over Japan'' (1967), on the diplomacy with Stalin regarding occupation 1945—195

online

* Fisher, Louis. "The Korean War: on what legal basis did Truman act?" ''American Journal of International Law'' 89.1 (1995): 21–39

online

* Fletcher, Luke. "The Collapse of the Western World: Acheson, Nitze, and the NSC 68/Rearmament Decision". ''Diplomatic History'' 40#4 (2016): 750–777. * Frazier, Robert. "Acheson and the Formulation of the Truman Doctrine". ''Journal of Modern Greek Studies'' 1999 17(2): 229–251.

* Freda, Isabelle. "Screening Power: Harry Truman and the Nuclear Leviathan" ''Comparative Cinema'' 7.12 (2019): 38–52. Hollywood's take. * Gaddis, John Lewis. "Reconsiderations: Was the Truman Doctrine a Real Turning Point?" ''Foreign Affairs'' 1974 52(2): 386–402

online

* Gaddis, John Lewis. ''Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of Postwar American National Security Policy'' (1982, 2nd ed 2005

online

* Gaddis, John Lewis. ''George F. Kennan: An American Life'' (2011)

online

* Geselbracht, Raymond H. ed. ''Foreign Aid and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman'' (2015). * Graebner, Norman A. ed. ''An Uncertain Tradition: American Secretaries of State in the Twentieth Century'' (1961) * Gusterson, Hugh. "Presenting the Creation: Dean Acheson and the Rhetorical Legitimation of NATO". ''Alternatives'' 24.1 (1999): 39–57. * * Hamby, Alonzo L. ''Beyond the New Deal: Harry S. Truman and American Liberalism'' (1973

online

* Harper, John Lamberton. ''American Visions of Europe: Franklin D. Roosevelt, George F. Kennan, and Dean G. Acheson''. (Cambridge University Press, 1994). 378 pp

online

* Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi. ''Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan'' (2009

online

* Heiss, Mary Ann, and Michael J. Hogan, eds. ''Origins of the National Security State and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman'' (Truman State University Press, 2015). 240 pp. * Hensley, Carl Wayne. "Harry S. Truman: Fundamental Americanism in foreign policy speechmaking, 1945–1946". ''Southern Journal of Communication'' 40.2 (1975): 180–190. * Herken, Gregg. ''The Winning Weapon: The Atomic Bomb in the Cold War, 1945–1950'' (1980

online

* Hinds, Lynn Boyd, and Theodore Otto Windt Jr. ''The Cold War as Rhetoric: The Beginnings, 1945–1950'' (1991) * Holloway, David. '' Stalin and the Bomb: The Soviet Union and Atomic Energy 1939–1956'' (Yale University Press, 1994) * Hopkins, Michael F. "President Harry Truman's Secretaries of State: Stettinius, Byrnes, Marshall and Acheson". ''Journal of Transatlantic Studies'' 6.3 (2008): 290–304. * Hopkins, Michael F. ''Dean Acheson and the Obligations of Power'' (Rowman & Littlefield, 2017). xvi, 289 pp

Excerpt

* House, Jonathan. ''A Military History of the Cold War, 1944–1962'' (2012

excerpt and text search

* Isaacson, Walter, and

excerpt and text search

* Ivie, Robert L. "Fire, Flood, and Red Fever: Motivating Metaphors of Global Emergency in the Truman Doctrine Speech". ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 1999 29(3): 570–591. * Jones, Howard. ''"A New Kind of War": America's Global Strategy and the Truman Doctrine in Greece'' (Oxford University Press. 1997). * Judis, John B.: ''Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict''. (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2014). * Karner, Stefan and Barbara Stelzl-Marx, eds. ''The Red Army in Austria: The Soviet Occupation, 1945–1955'' (2020

excerpt

* Kepley, David R. ''The Collapse of the Middle Way: Senate Republicans and the Bipartisan Foreign Policy, 1948–1952'' (1988). * Lacey, Michael J. ed. ''The Truman Presidency'' (1989) ch 7–13

excerpt

* LaFeber, Walter. ''America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945–2006'' (10th ed. McGraw-Hill, 2008

abstract

* Leffler, Melvyn P. ''For the Soul of Mankind: The United States, the Soviet Union, and the Cold War'' (2007). * Leffler, Melvyn P. ''A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration, and the Cold War'' (Stanford University Press, 1992). * Levine, Steven I. "A New Look at American Mediation in the Chinese Civil War: the Marshall Mission and Manchuria". ''Diplomatic History'' 1979 3(4): 349–375. * Luard, Evan. ''A History of the United Nations: Volume 1: The Years of Western Domination, 1945–1955'' (Springer, 1982). * McCauley, Martin. ''Origins of the Cold War 1941–49'' (3rd ed. 2013). * McGlothlen, Ronald L. ''Controlling the Waves: Dean Acheson and US Foreign Policy in Asia'' (1993) * McLellan, David S. ''Dean Acheson: The State Department Years'' (1976

online

* Maddox, Robert James. ''From War to Cold War: The Education of Harry S. Truman'' (Routledge, 2019). * Matray, James. "Truman's Plan for Victory: National Self Determination and the Thirty-Eighth Parallel Decision in Korea", ''Journal of American History'' 66 (September 1979), 314–333

in JSTOR

* Matray, James I. ''Northeast Asia and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman: Japan, China, and the Two Koreas'' (2012) * May, Ernest R. ed. ''The Truman Administration and China 1945–1949'' (1975) summary plus primary sources

online

* May, Ernest R. "1947–48: When Marshall Kept the U.S. Out of War in China". ''Journal of Military History'' 2002 66#4: pp 1001–10

Online

* Merrill, Dennis. "The Truman Doctrine: Containing Communism and Modernity" ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 2006 36#1: 27–37

online edition

* Messer, Robert L. ''The End of an Alliance: James F. Byrnes, Roosevelt, Truman, and the Origins of the Cold War'', (UNC Press Books, 2017). * Miscamble, Wilson D. "The Foreign Policy of the Truman Administration: A Post-Cold War Appraisal". ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 24.3 (1994): 479–494

online

* Miscamble, Wilson D. ''The Most Controversial Decision: Truman, the Atomic Bombs, and the Defeat of Japan'' (Cambridge University Press, 2011) * Moore Jr, John Allphin, and Jerry Pubantz. ''American Presidents and the United Nations: Internationalism in the Balance'' (Routledge, 2022)

excerpt

* Mower, A. Glenn. ''The United States, the United Nations, and human rights: the Eleanor Roosevelt and Jimmy Carter eras'' (1979

online

* Nau, Henry R. ''Conservative Internationalism: Armed Diplomacy Under Jefferson, Polk, Truman, and Reagan'' (Princeton University Press, 2015). * Nelson, Anna Kasten. "President Truman and the evolution of the National Security Council". ''Journal of American History'' 72.2 (1985): 360–378

online

* Offner, Arnold A. Another Such Victory': President Truman, American Foreign Policy, and the Cold War". ''Diplomatic History'' 1999 23#2: 127–155. * Offner, Arnold A. ''Another Such Victory: President Truman and the Cold War''. (2002) 640pp, negative appraisa

online

* Ottolenghi, Michael. "Harry Truman's recognition of Israel." ''Historical Journal'' 47.4 (2004): 963–988 * Pach Jr., Chester J. ''Arming the Free World: The Origins of the United States Military Assistance Program, 1945–1950'', (1991) * Paterson, Thomas G. ''Meeting the Communist Threat: Truman to Reagan'' (1988), by leading liberal historian * Paterson, Thomas G. "Presidential foreign policy, public opinion, and Congress: the Truman years". ''Diplomatic History'' 3.1 (1979): 1–18. * Pelz, Stephen. "When the Kitchen Gets Hot, Pass the Buck: Truman and Korea in 1950", ''Reviews in American History'' 6 (December 1978), 548–555. * Pearlman, Michael D. ''Truman and MacArthur: Policy, Politics, and the Hunger for Honor and Renown'' (Indiana University Press, 2008). * Pierce, Anne R. ''Woodrow Wilson & Harry Truman: Mission and Power in American Foreign Policy'' (Routledge, 2017). * Pierpaoli Jr., Paul G. ''Truman and Korea: The Political Culture of the Early Cold War''. (University of Missouri Press, 1999

online edition

* Pogue, Forrest. ''George C. Marshall: Statesman 1945–1959'

onlineonline

* Purifoy, Lewis McCarroll. ''Harry Truman's China Policy''. (Franklin Watts, 1976). * Rovere, Richard. ''General MacArthur and President Truman: The Struggle for Control of American Foreign Policy'' (Transaction, 1992). * Rusell, Ruth B. ''A History of the United Nations Charter: The Role of the United States, 1940–1945'' (Brookings Institution, 1958.) * Satterthwaite, Joseph C. "The Truman doctrine: Turkey". ''Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science'' 401.1 (1972): 74–84

online

* Schlesinger, Stephen C. ''Act of creation: The founding of the United Nations: A story of superpowers, secret agents, wartime allies and enemies, and their quest for a peaceful world.'' (Westview Press, 2003). * Schwartzberg, Steven. ''Democracy and US Policy in Latin America during the Truman Years'' (University Press of Florida, 2003). * Shaffer, Robert. "The Christian Century: Protestants Protesting Harry Truman's Cold War". ''Peace & Change'' 42.1 (2017): 93–127. * Sjöstedt, Roxanna. "The discursive origins of a doctrine: Norms, identity, and securitization under Harry S. Truman and George W. Bush". ''Foreign Policy Analysis'' 3.3 (2007): 233–254. * Snetsinger, John. ''Truman, the Jewish Vote, and the Creation of Israel'' (Hoover Institute Press, 1974). * Spalding, Elizabeth Edwards. "The enduring significance of the Truman doctrine". ''Orbis'' 61.4 (2017): 561–574. * Steil, Benn. ''The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War'' (2018

excerpt

* Stoler, Mark A. ''George C. Marshall: Soldier-Statesman of the American Century'' (1989

online

* Thornton, Richard C. ''Odd Man Out: Truman, Stalin, Mao, and the Origins of the Korean War'' (2001

online

* Wainstock, Dennis D. ''Truman, MacArthur, and the Korean War'' (1999) * Warren, Aiden, and Joseph M. Siracusa. "The Transition from Roosevelt to Truman." in ''US Presidents and Cold War Nuclear Diplomacy'' (Palgrave Macmillan Cham, 2021) pp. 19–34. * Webb, Clive. "Harry S. Truman and Clement Attlee: 'Trouble Always Brings Us Together'." in ''The Palgrave Handbook of Presidents and Prime Ministers From Cleveland and Salisbury to Trump and Johnson'' (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2022) pp. 157–178.

online

for middle and high school students

in JSTOR

* Gaddis, John Lewis. "The emerging post-revisionist synthesis on the origins of the Cold War". ''Diplomatic History'' 7.3 (1983): 171–190

online

* Griffith, Robert. "Truman and the Historians: The Reconstruction of Postwar American History". ''Wisconsin Magazine of History'' (1975) 59#1 pp: 20–47, covers both foreign and domestic policy

online

* Margolies, Daniel S. ed. ''A Companion to Harry S. Truman'' (2012

excerpt

most of the 27 chapters deal with foreign policy topics. * Matray, James I., and Donald W. Boose Jr, eds. ''The Ashgate research companion to the Korean War'' (2014

excerpt

* Melanson, Richard A. ''American foreign policy since the Vietnam War: the search for consensus from Nixon to Clinton'' (Routledge, 2015). * Miscamble, Wilson D. "The Foreign Policy of the Truman Administration: A Post-Cold War Appraisal". ''Presidential Studies Quarterly'' 24.3 (1994): 479–494

Online

* O'Connell, Kaete. "Harry S. Truman and US Foreign Relations". in ''Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History'' (2019)

online

* Romero, Federico. "Cold War historiography at the crossroads". ''Cold War History'' 14.4 (2014): 685–703. * Smith, Geoffrey S. "'Harry, We Hardly Know You': Revisionism, Politics and Diplomacy, 1945–1954", ''American Political Science Review'' 70#2 (June 1976), 560–582

online

* Trachtenberg, Marc. "The United States and Eastern Europe in 1945" ''Journal of Cold War Studies'' (2008) 10#4 pp 94–132

excerpt

* Walker, J. Samuel. ''Prompt and Utter Destruction: Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs against Japan'' (1997) * Walker, J. Samuel. "Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision: A Search for Middle Ground" ''Diplomatic History'' April 2005 – 29#2 pp 311–334 * Westad, Odd Arne. ''Reviewing the Cold War: Approaches, Interpretations, Theory'' (Routledge, 2013).

online

* Bernstein, Barton J. and Allen J. Matusow, eds. ''The Truman administration: A Documentary History'' (1966); 518 pp

online

* Mills, Walter, and E. S. Duffield, eds. ''The Forestall Diaries'' (1951). {{Foreign policy of U.S. presidents Presidency of Harry S. Truman Truman, Harry S. United States foreign policy

The main issues of the

The main issues of the United States foreign policy

The officially stated goals of the foreign policy of the United States of America, including all the bureaus and offices in the United States Department of State, as mentioned in the ''Foreign Policy Agenda'' of the Department of State, are ...

during the 1945–1953 presidency of Harry S. Truman were working with Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, especially Britain, the Soviet Union and China. The goals were to achieve victory over Germany and Japan; deal with the chaos in Europe and Asia in the aftermath of World War II; handle the beginning of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

with the USSR; and launch new international organizations such as the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

and the World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Interna ...

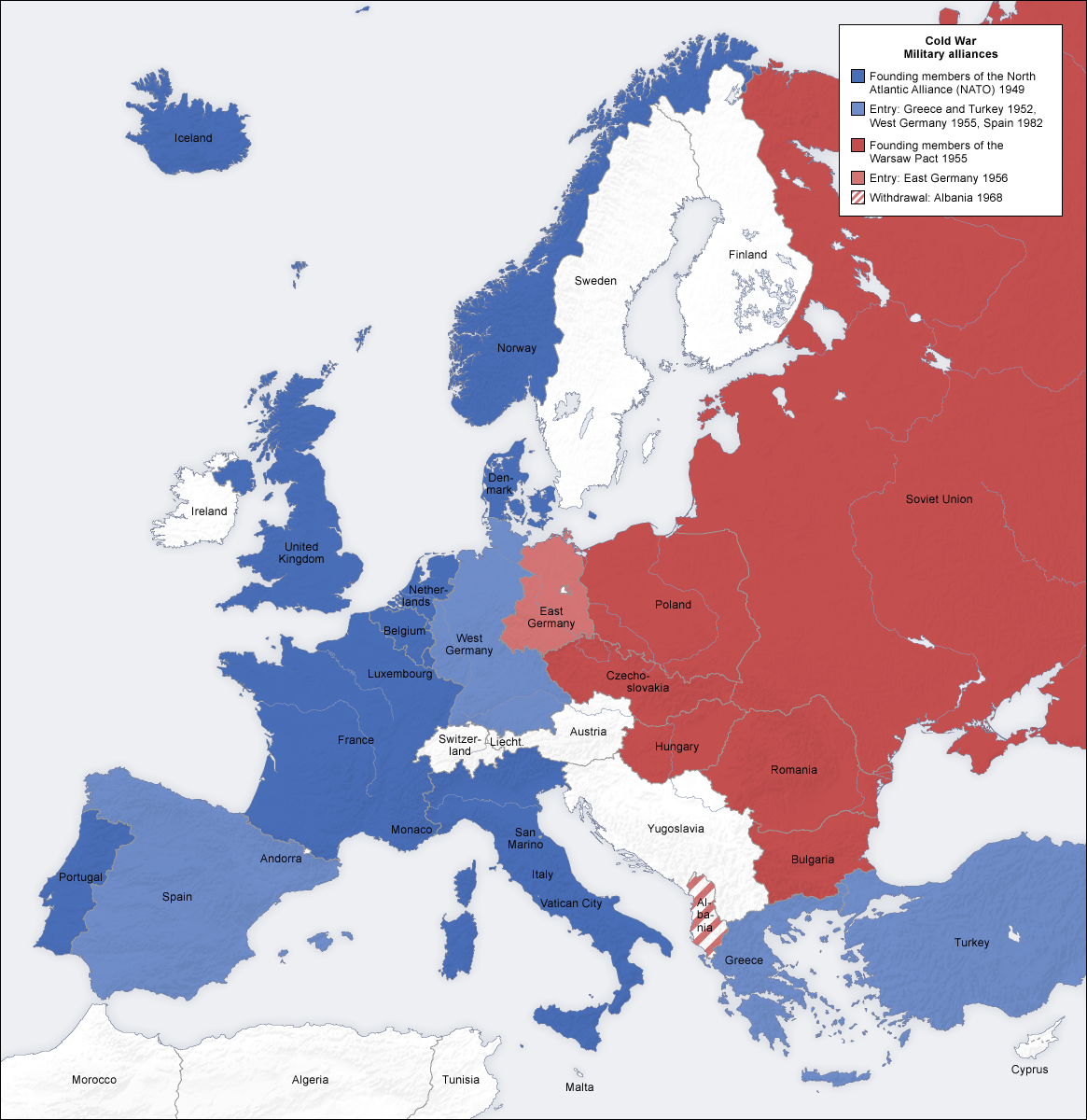

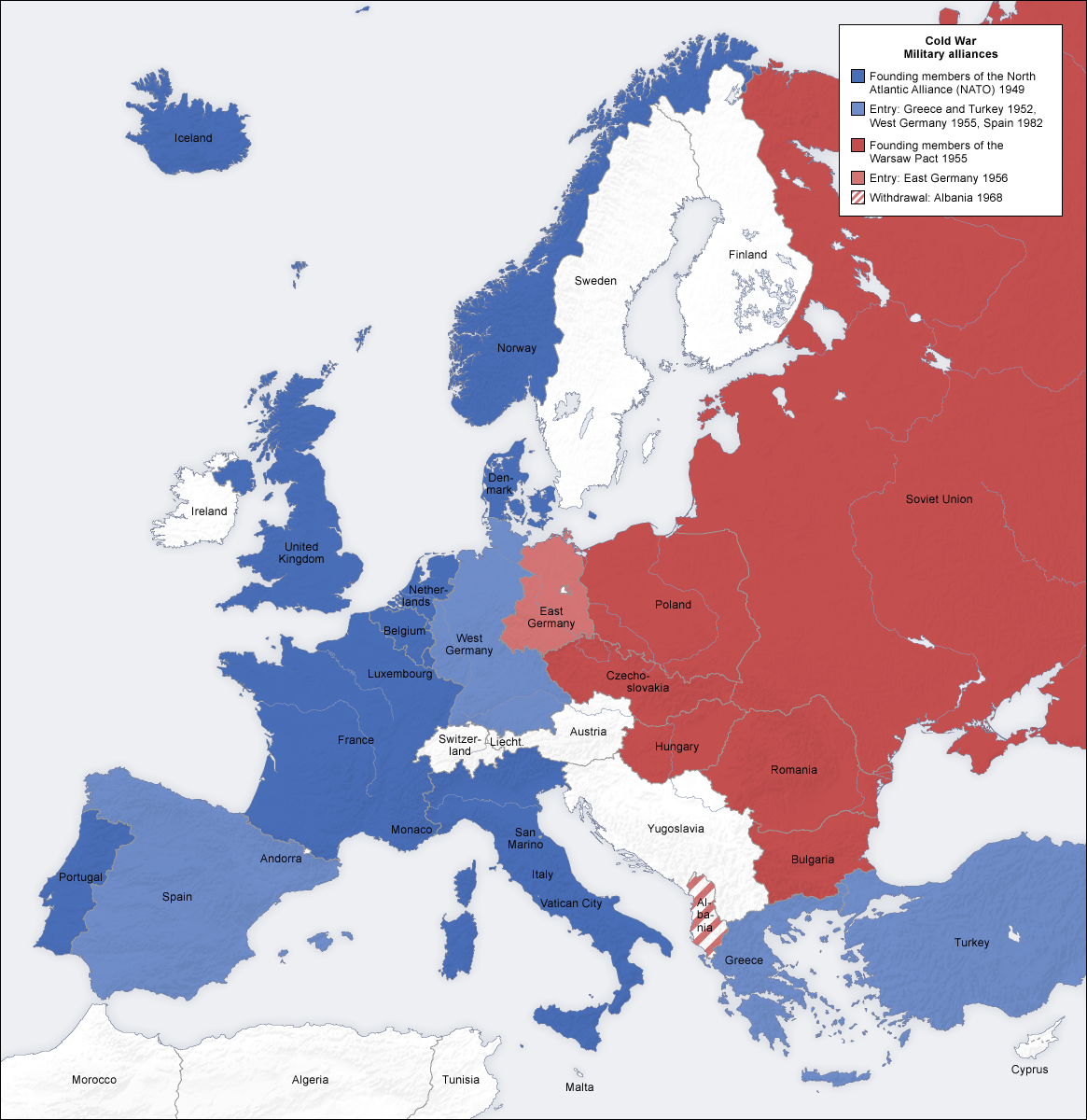

. Truman's presidency was a turning point in foreign affairs, as the United States engaged in a liberal internationalist foreign policy and renounced isolationism by engaging in a long global conflict with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and its allies, forming NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

, and fighting China in the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

to a deadlock.

Truman took office upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

during the final months of war. Until then Truman had little interest in foreign affairs and no knowledge of Roosevelt's plans. He relied heavily on advisers like George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ...

and Dean Acheson, both of whom served as Secretary of State. Germany surrendered days after Truman took office, but the Japan initially refused to surrender or negotiate. In order to force Japan's surrender without resorting to an invasion of the main Japanese islands, Truman approved of plans to drop atomic bombs on two Japanese cities. Even before Germany and Japan surrendered, the Truman administration worked with Moscow, London and other Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

to establish post-war international institutions and agreements. Most hope was placed in the United Nations until Moscow's veto made it ineffective. In economics there was the International Refugee Organization

The International Refugee Organization (IRO) was an intergovernmental organization founded on 20 April 1946 to deal with the massive refugee problem created by World War II. A Preparatory Commission began operations fourteen months previously. ...

, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is a legal agreement between many countries, whose overall purpose was to promote international trade by reducing or eliminating trade barriers such as tariffs or quotas. According to its pre ...

. The Truman administration embarked on a policy of rebuilding democracy and the economy in Japan and West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

. It acted practically alone in Japan, and with Moscow, London and Paris in Germany.

Tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union escalated after 1945, and by 1947 the two countries had entered a sustained period of geopolitical tension known as the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. Truman adopted a policy of containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''cordon sanitaire'', which wa ...

, in which the U.S. would attempt to prevent the spread of Communism but would not actively seek to regain territory already lost to Communism. He also announced the Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is an American foreign policy that pledged American "support for democracies against authoritarian threats." The doctrine originated with the primary goal of containing Soviet geopolitical expansion during the Cold War. It wa ...

, a policy of aiding countries in danger of falling to Communism. Pursuant to this doctrine, Truman convinced Congress to provide an unprecedented aid package to Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

and Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

, overcoming opposition from isolationists and some on the left who favored more conciliatory policies towards the Soviet Union. The following year, Truman convinced Congress to approve the Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

, $13 billion aid package enacted to rebuild Western Europe. In 1949, the U.S., Canada, and several European countries signed the North Atlantic Treaty

The North Atlantic Treaty, also referred to as the Washington Treaty, is the treaty that forms the legal basis of, and is implemented by, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The treaty was signed in Washington, D.C., on 4 April 194 ...

, establishing the NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

military alliance. Meanwhile, domestic fears of Soviet espionage led to a Red Scare and the rise of McCarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origin ...

in the United States.

The Truman administration attempted to mediate the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

and failed. The Communist forces under Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

took control of Mainland China

"Mainland China" is a geopolitical term defined as the territory governed by the People's Republic of China (including islands like Hainan or Chongming), excluding dependent territories of the PRC, and other territories within Greater China. ...

in 1949. In June 1950 Communist North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

invaded South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

in an attempt to reunify the country. Acting under the aegis of the United Nations, the U.S. intervened, defeated the invaders, and prepared to unify Korea UN terms. However, in late 1950 millions of Chinese soldiers entered Korea and pushed the allies back. The war settled into a stalemate along a line close to its starting point. Truman left office quite unpopular, but scholars generally consider him to be an above average president, and his administration has been credited for establishing Cold War policies that contained the Soviets.

Leadership

At first Truman kept all of Roosevelt's cabinet. By late 1946 only one remained. Even as vice president, knowing of the president's poor health, he showed little curiosity about Roosevelt's postwar plans and was kept out of the loop. Furthermore, he had a small White House staff that knew little about diplomacy. As president he relied heavily on top officials from the State Department. Truman quickly replaced Secretary of State Edward Stettinius Jr. with James F. Byrnes, a personal friend from Senate days. By 1946, Truman was taking a hard line against the Kremlin, although Byrnes was still trying to be conciliatory. The divergence in policy was intolerable. Truman replaced Byrnes with the highly prestigious five-star army generalGeorge Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ...

in January 1947, despite Marshall's failure in negotiating a settlement in the Chinese Civil War. In 1947, Forrestal became the first Secretary of Defense, with his department overseeing all three branches of the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

. Mental illness sent Forrestal into retirement in 1949, and he was replaced successively by Louis A. Johnson who did poorly. Then came Marshall, and finally Robert A. Lovett

Robert Abercrombie Lovett (September 14, 1895May 7, 1986) was the fourth United States Secretary of Defense, having been promoted to this position from Deputy Secretary of Defense. He served in the cabinet of President Harry S. Truman from 1951 ...

.

At the Department of State, the key person was Dean Acheson, who replaced Marshall as secretary in 1949. The Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

embodied Acheson's analysis of the European crisis; he designed America's role. As tensions mounted with Moscow, Acheson moved from guarded optimism to pessimism. He decided negotiations were futile, and the United States had to mobilize a network of allies to resist the Kremlin's quest for world domination, using both military and especially economic power. Downplaying the importance of communism in China, Acheson emphasized Europe, and took the lead, as soon as he became Secretary of State in January 1949, to nail down the NATO alliance. It worked closely with the major European powers, as well as cooperating closely with Republican Senator Arthur Vandenberg

Arthur Hendrick Vandenberg Sr. (March 22, 1884April 18, 1951) was an American politician who served as a United States senator from Michigan from 1928 to 1951. A member of the Republican Party, he participated in the creation of the United Natio ...

, build bipartisan support at a time when the Republican Party controlled Congress after the 1946 United States elections

The 1946 United States elections were held on November 5, 1946, and elected the members of the 80th United States Congress. In the first election after World War II, incumbent President Harry S. Truman (who took office on April 12, 1945, upon the ...

. According to Townsend Hoopes, throughout his long career, Acheson displayed:

:exceptional intellectual power and purpose, and tough inner fiber. He projected the long lines and aristocratic bearing of the thoroughbred horse, a self-assured grace, an acerbic elegance of mind, and a charm whose chief attraction was perhaps its penetrating candor. ... ewas swift-flowing and direct. ... Acheson was perceived as an 18th-century rationalist ready to apply an irreverent wit to matters public and private.

The American occupation of Japan was nominally an Allied endeavor, but in practice it was run by General Douglas MacArthur, with little or no consultation with the Allies or with Washington. His responsibilities were enlarged to include the Korean War, till he broke with Truman on policy issues and was fired in highly dramatic fashion in 1951. Policy for the occupation of West Germany was much less controversial, and the decisions were made in Washington, with Truman himself making the key decision to rebuild West Germany as an economic power.

Roosevelt had handled all foreign policy decisions on his own, with a few advisors such as Harry Hopkins, who helped Truman too, even though he was dying of cancer. Roosevelt's final Secretary of State, Edward R. Stettinius was an amiable businessman who succeeded at reorganization of the department, and spent most of his attention in the creation of the United Nations. When that was accomplished, Truman replaced him with James F. Byrnes, whom Truman knew well from their Senate days together. Byrnes was more interested in domestic than foreign affairs, and felt he should have been FDR's pick for vice president in 1944. He was secretive, not telling Truman about major developments. Dean Acheson by this point was the number two person in State, and worked well with Truman. The president finally replaced Byrnes with Marshall. With the world in incredibly complex turmoil, international travel was essential. Byrnes spent 62% of his time abroad; Marshall spent 47% and Acheson 25%.

Winning World War II

By April 1945, the Allied Powers, led by the United States,Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

, and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, were close to defeating Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, but Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

remained a formidable adversary in the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast ...

. As vice president, Truman had been uninformed about major initiatives relating to the war, including the top-secret Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, which was about to test the world's first atomic bomb.Barton J. Bernstein, "Roosevelt, Truman, and the atomic bomb, 1941–1945: a reinterpretation". ''Political Science Quarterly'' 90.1 (1975): 23–69. Although Truman was told briefly on the afternoon of April 12 that the Allies had a new, highly destructive weapon, it was not until April 25 that Secretary of War Henry Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and D ...

told him the details of the atomic bomb, which was almost ready. Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, and Truman's attention turned to the Pacific, where he hoped to end the war as quickly, and with as little expense in lives or government funds, as possible.

With the end of the war drawing near, Truman flew to Berlin for the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

, to meet with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

and British leader Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

regarding the post-war order. Several major decisions were made at the Potsdam Conference: Germany would be divided into four occupation zones (among the three powers and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

), the Germany–Poland border

The Germany–Poland border (german: Grenze zwischen Deutschland und Polen, pl, Granica polsko-niemiecka), the state international border, border between Poland and Germany, is currently the Oder–Neisse line. It has a total length of (Downl ...

was to be shifted west to the Oder–Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line (german: Oder-Neiße-Grenze, pl, granica na Odrze i Nysie Łużyckiej) is the basis of most of the international border between Germany and Poland from 1990. It runs mainly along the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers a ...

, the Soviet-backed Provisional Government of National Unity

The Provisional Government of National Unity ( pl, Tymczasowy Rząd Jedności Narodowej - TRJN) was a puppet government formed by the decree of the State National Council () on 28 June 1945 as a result of reshuffling the Soviet-backed Provisio ...

was recognized as the legitimate government of Poland, and Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

was to be partitioned at the 16th parallel. The Soviet Union also agreed to launch an invasion of Japanese-held Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manc ...

. While at the Potsdam Conference, Truman was informed that the Trinity test

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon. It was conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was conducted in the Jornada del Muerto desert abo ...

of the first atomic bomb on July 16 had been successful. He hinted to Stalin that the U.S. was about to use a new kind of weapon against the Japanese. Though this was the first time the Soviets had been officially given information about the atomic bomb, Stalin was already aware of the bomb project, having learned about it through espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangibl ...

long before Truman did.

In August 1945, the Japanese government ignored surrender demands as specified in the Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, Uni ...

. With the support of most of his aides, Truman approved the schedule of the military's plans to drop atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

and Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

. Hiroshima was bombed on August 6, and Nagasaki three days later, leaving approximately 135,000 dead; another 130,000 would die from radiation sickness and other bomb-related illnesses in the following five years. Japan agreed to surrender on August 10, on the sole condition that Emperor Hirohito would not be forced to abdicate; after some internal debate, the Truman administration accepted these terms of surrender.

The decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki provoked long-running debates. Supporters of the bombings argue that, given the tenacious Japanese defense of the outlying islands, the bombings saved hundreds of thousands of lives that would have been lost invading mainland Japan. After leaving office, Truman told a journalist that the atomic bombing "was done to save 125,000 youngsters on the American side and 125,000 on the Japanese side from getting killed and that is what it did. It probably also saved a half million youngsters on both sides from being maimed for life." Truman was also motivated by a desire to end the war before the Soviet Union could invade Japanese-held territories and set up Communist governments. Critics have argued that the use of nuclear weapons was unnecessary, given that conventional tactics such as firebombing and blockade might induce Japan's surrender without the need for such weapons.

Postwar international order

Truman at first was committed to following Roosevelt's policies and priorities. However he soon replaced Roosevelt's top appointments and put in his own people. In 1945 public opinion was demanding immediate demobilization of the troops. The Administration's policies were designed to benefit individuals, regardless of the damage it did when experienced military units lost their longest-serving and most experience soldiers. Truman refused to consider keeping an army in Europe for the purpose of neutralizing Stalin's expansion. While his State Department was taking an increasingly hard line, the War Department took a more conciliatory position. It refused to allocate additional forces to Europe. In practice, the American forces were removed from Europe as fast as possible. By 1946, however, Truman had changed. He was now distrustful of Stalin and alarmed about Soviet pressures on Iran and Poland. He was disappointed with the UN. Truman now accepted more and more advice from the State Department and was moving rapidly toward a hard-line, Cold War position. The Soviet Union had become the enemy.United Nations

When Truman took office, several international organizations that were designed to help prevent future wars and international economic crises were in the process of being established. Chief among those organizations was theUnited Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

, an intergovernmental organization similar to the defunct League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. It that was designed to help ensure international cooperation under the control of the U.S., USSR, Britain, France and China, each of which could veto a major decision. When Truman took office, delegates were about to meet at the United Nations Conference on International Organization

The United Nations Conference on International Organization (UNCIO), commonly known as the San Francisco Conference, was a convention of delegates from 50 Allied nations that took place from 25 April 1945 to 26 June 1945 in San Francisco, Cali ...

in San Francisco. As a Wilsonian

Wilsonianism, or Wilsonian idealism, is a certain type of foreign policy advice. The term comes from the ideas and proposals of President Woodrow Wilson. He issued his famous Fourteen Points in January 1918 as a basis for ending World War I and p ...

internationalist, Truman strongly supported the creation of the United Nations, and he signed United Nations Charter

The Charter of the United Nations (UN) is the foundational treaty of the UN, an intergovernmental organization. It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the UN system, including its six principal organs: the ...

at the San Francisco Conference. Truman did not repeat Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's partisan attempt to ratify the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

in 1919. Instead he cooperating closely with Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg

Arthur Hendrick Vandenberg Sr. (March 22, 1884April 18, 1951) was an American politician who served as a United States senator from Michigan from 1928 to 1951. A member of the Republican Party, he participated in the creation of the United Natio ...

and other Republican leaders to ensure ratification. Cooperation with Vandenberg, a leading figure on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid p ...

, proved to be crucial for Truman's foreign policy, especially after Republicans gained control of Congress in the 1946 elections. Construction of the United Nations headquarters

zh, 联合国总部大楼french: Siège des Nations uniesrussian: Штаб-квартира Организации Объединённых Наций es, Sede de las Naciones Unidas

, image = Midtown Manhattan Skyline 004.jpg

, im ...

in New York City was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, after the Carneg ...

and completed in 1952.

Trade and tariffs

In 1934, a Democratic Congress passed theReciprocal Tariff Act

The Reciprocal Tariff Act (enacted June 12, 1934, ch. 474, , ) provided for the negotiation of tariff agreements between the United States and separate nations, particularly Latin American countries. The Act served as an institutional reform inte ...

, giving the Administration an unprecedented amount of authority in setting tariff rates. The Republicans had raised the tariffs to a high levels that dramatically reduced imports and exports. The act allowed for the creation of reciprocal agreements in which the U.S. and other countries mutually agreed to lower tariff rates. Despite significant opposition from those who favored higher tariffs, Truman was able to win legislative extension of the reciprocity program, and his administration reached numerous bilateral agreements that lowered trade barriers. The Truman administration also sought to further lower global tariff rates by engaging in multilateral trade negotiations, and the State Department proposed the establishment of the International Trade Organization

The International Trade Organization (ITO) was the proposed name for an international institution for the regulation of trade.

Led by the United States in collaboration with allies, the effort to form the organization from 1945 to 1948, with the ...

(ITO). The ITO was designed to have broad powers to regulate trade among member countries, and its charter was approved by the United Nations in 1948. However, the ITO's broad powers engendered opposition in Congress, and Truman declined to send the charter to the Senate for ratification. In the course of creating the ITO, the U.S. and 22 other countries signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is a legal agreement between many countries, whose overall purpose was to promote international trade by reducing or eliminating trade barriers such as tariffs or quotas. According to its pre ...

(GATT), a set of principles governing trade policy. Under the terms of the agreement, each country agreed to reduce overall tariff rates and to treat each co-signatory as a " most favoured nation", meaning that no non-signatory country could benefit from more advantageous tariff rates. Due to a combination of the Reciprocal Tariff Act, the GATT, and inflation, American tariff rates fell dramatically between the passage of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act

The Tariff Act of 1930 (codified at ), commonly known as the Smoot–Hawley Tariff or Hawley–Smoot Tariff, was a law that implemented protectionist trade policies in the United States. Sponsored by Senator Reed Smoot and Representative Willi ...

in 1930 and the end of the Truman administration in 1953.

Refugees

World War II left millions ofrefugees

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

displaced in Europe. To help address this problem, Truman backed the founding of the International Refugee Organization

The International Refugee Organization (IRO) was an intergovernmental organization founded on 20 April 1946 to deal with the massive refugee problem created by World War II. A Preparatory Commission began operations fourteen months previously. ...

(IRO), a temporary international organization that helped resettle refugees. The United States also funded temporary camps and admitted large numbers of refugees as permanent residents

Permanent residency is a person's legal resident status in a country or territory of which such person is not a citizen but where they have the right to reside on a permanent basis. This is usually for a permanent period; a person with such ...

. Truman obtained ample funding from Congress for the Displaced Persons Act

The Displaced Persons Act of 1948 authorized for a limited period of time the admission into the United States of 200,000 certain European displaced persons (DPs) for permanent residence.

This displaced persons (DP) Immigration program emerged fro ...

of 1948, which allowed many of the displaced people of World War II to immigrate into the United States. Of the approximately one million people resettled by the IRO, more than 400,000 settled in the United States.

The most contentious issue was the resettlement of European Jewish refugees. Truman at first followed the State Department policy of friendship with the Arabs and agreement with the British opposition to Jewish entry into Palestine. However Truman's close links to the pro-Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

elements in the Jewish community

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

led him to reverse positions and overrule the State Department. He urged London to admit 100,000 displaced Jews in British-controlled Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

and strongly supported the new state of Israel.

The Administration helped created a new category of refugee, the "escapee", at the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. The American Escapee Program began in 1952 to help the flight and relocation of political refugees

The right of asylum (sometimes called right of political asylum; ) is an ancient juridical concept, under which people persecuted by their own rulers might be protected by another sovereign authority, like a second country or another ent ...

from communism in Eastern Europe. The motivation for the refugee and escapee programs was twofold: humanitarianism, and use as a political weapon against inhumane communism. The State Department's Policy Planning Staff worked with Hollywood to publicize death-defying refugee escapes as an anti-Communist theme in movies. However many escapees had been active in the Communist parties, and they were not allowed into the U.S. under the McCarran Internal Security Act

The Internal Security Act of 1950, (Public Law 81-831), also known as the Subversive Activities Control Act of 1950, the McCarran Act after its principal sponsor Sen. Pat McCarran (D-Nevada), or the Concentration Camp Law, is a United States fede ...

of 1950 and the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952.

Atomic energy and weaponry

In March 1946, at an optimistic moment for postwar cooperation, the administration released the Acheson-Lilienthal Report, which proposed that all nations voluntarily abstain from constructing nuclear weapons. As part of the proposal, the U.S. would dismantle its nuclear program once all other countries agreed not to develop or otherwise acquire nuclear weapons. Fearing that Congress would reject the proposal, Truman turned to the well-connected Bernard Baruch to represent the American position to the United Nations. The Baruch Plan, largely based on the Acheson-Lilienthal Report, was not adopted due to opposition from Congress and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union would develop its own nuclear arsenal, testing a nuclear weapon for the first time in August 1949. TheUnited States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President H ...

, directed by David E. Lilienthal until 1950, was in charge of designing and building nuclear weapons under a policy of full civilian control. The U.S. had only 9 atomic bombs in 1946, but the stockpile grew to 650 by 1951. Lilienthal wanted to give high priority to peaceful uses for nuclear technology, especially nuclear power plant

A nuclear power plant (NPP) is a thermal power station in which the heat source is a nuclear reactor. As is typical of thermal power stations, heat is used to generate steam that drives a steam turbine connected to a electric generator, generato ...

s, but coal was cheap and the power industry was largely uninterested in building nuclear power plant

A nuclear power plant (NPP) is a thermal power station in which the heat source is a nuclear reactor. As is typical of thermal power stations, heat is used to generate steam that drives a steam turbine connected to a electric generator, generato ...

s during the Truman administration. Construction of the first nuclear plant would not begin until 1954. In early 1950, Truman authorized the development of thermonuclear weapon

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

s, a more powerful version of atomic bombs. Truman's decision to develop thermonuclear weapons faced opposition from many liberals and some government officials, but he believed that the Soviet Union would likely develop the weapons and was unwilling to allow the Soviets to have such an advantage. The first test

''First Test'', is a fantasy novel by Tamora Pierce, the first book in the series ''Protector of the Small''. It details the first year of Keladry of Mindelan's training as a page of Tortall.

Plot introduction

''Protector of the Small'' is set ...

of thermonuclear weaponry was conducted by the United States in 1952; the Soviet Union would perform its own thermonuclear test in August 1953.

Beginning of the Cold War, 1945–1950

Escalating tensions, 1945–1946

Interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

. On taking office, Truman privately viewed the Soviet Union as a "police government pure and simple", but he was initially reluctant to take a hard-line towards the Soviet Union, as he hoped to work with the Soviets in the aftermath of Second World War

Aftermath may refer to:

Companies

* Aftermath (comics), an imprint of Devil's Due Publishing

* Aftermath Entertainment, an American record label founded by Dr. Dre

* Aftermath Media, an American multimedia company

* Aftermath Services, an American ...

. Truman's suspicions deepened as the Soviets consolidated their control in Eastern Europe throughout 1945, and the February 1946 announcement of the Soviet five-year plan further strained relations as it called for the continuing build-up of the Soviet military. At the December 1945 Moscow Conference, Secretary of State Byrnes agreed to recognize the pro-Soviet governments in the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, while the Soviet leadership accepted U.S. leadership in the occupation of Japan. U.S. concessions at the conference angered other members of the Truman administration, including Truman himself. By the beginning of 1946, it had become clear to Truman that Britain and the United States would have little influence in Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe.

Former Vice President Henry Wallace, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

, and many other prominent Americans continued to hope for cooperative relations with the Soviet Union. Some liberals, like Reinhold Niebuhr

Karl Paul Reinhold Niebuhr (June 21, 1892 – June 1, 1971) was an American Reformed theologian, ethicist, commentator on politics and public affairs, and professor at Union Theological Seminary for more than 30 years. Niebuhr was one of Ameri ...

, distrusted the Soviet Union but believed that the United States should not try to counter Soviet influence in Eastern Europe, which the Soviets saw as their "strategic security belt". Partly because of this sentiment, Truman was reluctant to fully break with the Soviet Union in early 1946, but he took an increasingly hard line towards the Soviet Union throughout the year. He personally approved of Winston Churchill's March 1946 "Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its s ...

" speech, which urged the United States to take the lead of an anti-Soviet alliance, though he did not publicly endorse it.

Throughout 1946, tensions arose between the United States and the Soviet Union in places like Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, which the Soviets had occupied during World War II. Pressure from the U.S. and the United Nations finally forced the withdrawal of Soviet soldiers. Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

also emerged as a point of contention, as the Soviet Union demanded joint control over the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

and the Bosphorus, key strait

A strait is an oceanic landform connecting two seas or two other large areas of water. The surface water generally flows at the same elevation on both sides and through the strait in either direction. Most commonly, it is a narrow ocean channe ...

s that controlled movement between the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

and the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

. The U.S. forcefully opposed this proposed alteration to the 1936 Montreux Convention

The (Montreux) Convention regarding the Regime of the Straits, often known simply as the Montreux Convention, is an international agreement governing the Bosporus and Dardanelles Straits in Turkey. Signed on 20 July 1936 at the Montreux Palace ...

, which had granted Turkey sole control over the straits, and Truman dispatched a fleet to the Eastern Mediterranean

Eastern Mediterranean is a loose definition of the eastern approximate half, or third, of the Mediterranean Sea, often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea.

It typically embraces all of that sea's coastal zones, referring to communi ...

to show his administration's commitment to the region. The Soviet Union and the United States also clashed in Germany, which had been divided into four occupation zones. In the September 1946 Stuttgart speech, Secretary of State Byrnes announced that the United States would no longer seek reparations from Germany and would support the establishment of a democratic state. The United States, France, and Britain agreed to combine their occupation zones, eventually forming West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

. In East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea and ...

, Truman denied the Soviet request to reunify Korea, and refused to allow the Soviets a role in the post-war occupation of Japan.

By September 1946, Truman was convinced that the Soviet Union sought world domination and that cooperation was futile. He adopted a policy of containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''cordon sanitaire'', which wa ...

, based on a 1946 cable by diplomat George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly hist ...

. Containment, a policy of preventing the further expansion of Soviet influence, represented a middle-ground position between friendly détente

Détente (, French: "relaxation") is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The term, in diplomacy, originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsuccessfully to reduce ...

(as represented by Wallace), and aggressive rollback

In political science, rollback is the strategy of forcing a change in the major policies of a state, usually by replacing its ruling regime. It contrasts with containment, which means preventing the expansion of that state; and with détente, w ...

to regain territory already lost to Communism, as would be adopted in 1981 by Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

. Kennan's doctrine was based on the notion that the Soviet Union was led by an uncompromising totalitarian regime, and that the Soviets were primarily responsible for escalating tensions. Wallace, who had been appointed Secretary of Commerce after the 1944 presidential election, resigned from the cabinet in September 1946 due to Truman's hardening stance towards the Soviet Union.

Truman Doctrine

In the first major step in implementing containment, Truman gave money to Greece and Turkey to prevent the spread of Soviet-aligned governments. Prior to 1947, the U.S. had largely ignored Greece, which had an anti-communist government, because it was under British influence. Since 1944, the British had assisted the Greek government against a left-wing insurgency, but in early 1947 London informed Washington that it could no longer afford to intervene in Greece. At the urging of Acheson, who warned that the fall of Greece could lead to the expansion of Soviet influence throughout Europe, Truman requested that Congress grant an unprecedented $400 million aid package to Greece and Turkey. In a March 1947 speech before a joint session of Congress, written by Acheson, Truman articulated theTruman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is an American foreign policy that pledged American "support for democracies against authoritarian threats." The doctrine originated with the primary goal of containing Soviet geopolitical expansion during the Cold War. It wa ...

. It called for the United States to support "free people who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures." Overcoming isolationists who opposed involvement, as well as those on the left who wanted cooperation with Moscow, Truman won bipartisan approval of the aid package. The congressional vote represented a permanent break with the non-interventionism

Non-interventionism or non-intervention is a political philosophy or national foreign policy doctrine that opposes interference in the domestic politics and affairs of other countries but, in contrast to isolationism, is not necessarily opposed t ...

that had characterized U.S. foreign policy prior to World War II.

The United States became closely involved in the Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War ( el, ο Eμφύλιος �όλεμος ''o Emfýlios'' 'Pólemos'' "the Civil War") took place from 1946 to 1949. It was mainly fought against the established Kingdom of Greece, which was supported by the United Kingdom ...

, which ended with the defeat of the insurgency in 1949. Stalin and Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

n leader Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his deat ...

both provided aid to the insurgents, but they fought for control causing a split in the Communist bloc. American military and economic aid to Turkey also proved effective, and Turkey avoided a civil war.

The Truman administration provided aid to the Christian Democrat

Christian democracy (sometimes named Centrist democracy) is a political ideology that emerged in 19th-century Europe under the influence of Catholic social teaching and neo-Calvinism.

It was conceived as a combination of modern democratic ...

government during the 1948 Italian general election where the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A ...

had strength. The aid package, combined with a covert CIA operation, anti-Communist mobilization by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and Italian Americans

Italian Americans ( it, italoamericani or ''italo-americani'', ) are Americans who have full or partial Italian ancestry. The largest concentrations of Italian Americans are in the urban Northeast and industrial Midwestern metropolitan areas, w ...

, helped to produce a Communist defeat.

The initiatives of the Truman Doctrine solidified the post-war division between the United States and the Soviet Union, and the Soviet Union responded by tightening its control over Eastern Europe. Countries aligned with the Soviet Union became known as the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

, while the U.S. and its allies became known as the Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Free Bloc, the Capitalist Bloc, the American Bloc, and the NATO Bloc, was a coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War of 1947–1991. It was spearheaded by ...

.

Although the far left element in the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

and the Congress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of unions that organized workers in industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in 1935 as a committee within the American Federation of ...

was being expelled, some liberal Democrats opposed the Truman Doctrine. Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

wrote Truman in April 1947 calling him to rely on the UN instead of his Truman Doctrine. She denounced Greece and Turkey because they were undemocratic. Truman needing support from the Roosevelt's liberal wing, wrote her that while he held onto his long-term hopes for the United Nations, he insisted that and an "economically, ideologically and politically sound" peace would more likely come from American action, than from the UN. He emphasized the strategic geographical importance of the Greek-Turkish land bridge as a critical point in which democratic forces could stop the advance of communism that had so ravaged Eastern Europe.

A new policy in 1947 was to forbid the sale to the Soviet bloc (and China after 1949) of high tech

High technology (high tech), also known as advanced technology (advanced tech) or exotechnology, is technology that is at the cutting edge: the highest form of technology available. It can be defined as either the most complex or the newest te ...

nology that had military uses. Washington convinced its allies to follow suit. Richard Nixon finally relaxed the policy in 1970.

Military reorganization and budgets

Facing new, global challenges, Washington reorganized the military and intelligence establishment to provide for more centralized control and reduce rivalries. The National Security Act of 1947 merged the Department of War and theDepartment of the Navy Navy Department or Department of the Navy may refer to:

* United States Department of the Navy,

* Navy Department (Ministry of Defence), in the United Kingdom, 1964-1997

* Confederate States Department of the Navy, 1861-1865

* Department of the ...

into the National Military Establishment

The United States Department of Defense (DoD, USDOD or DOD) is an executive branch department of the federal government charged with coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government directly related to national secur ...

(which was later renamed as the Department of Defense Department of Defence or Department of Defense may refer to:

Current departments of defence

* Department of Defence (Australia)

* Department of National Defence (Canada)

* Department of Defence (Ireland)

* Department of National Defense (Philipp ...

). The law also separated the U.S. Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Sign ...

from the Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

. It created the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

(CIA), and the National Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a na ...

(NSC). The CIA and the NSC were designed to be civilian bodies that would increase U.S. preparation against foreign threats without assuming the domestic functions of the Federal Bureau of Investigation