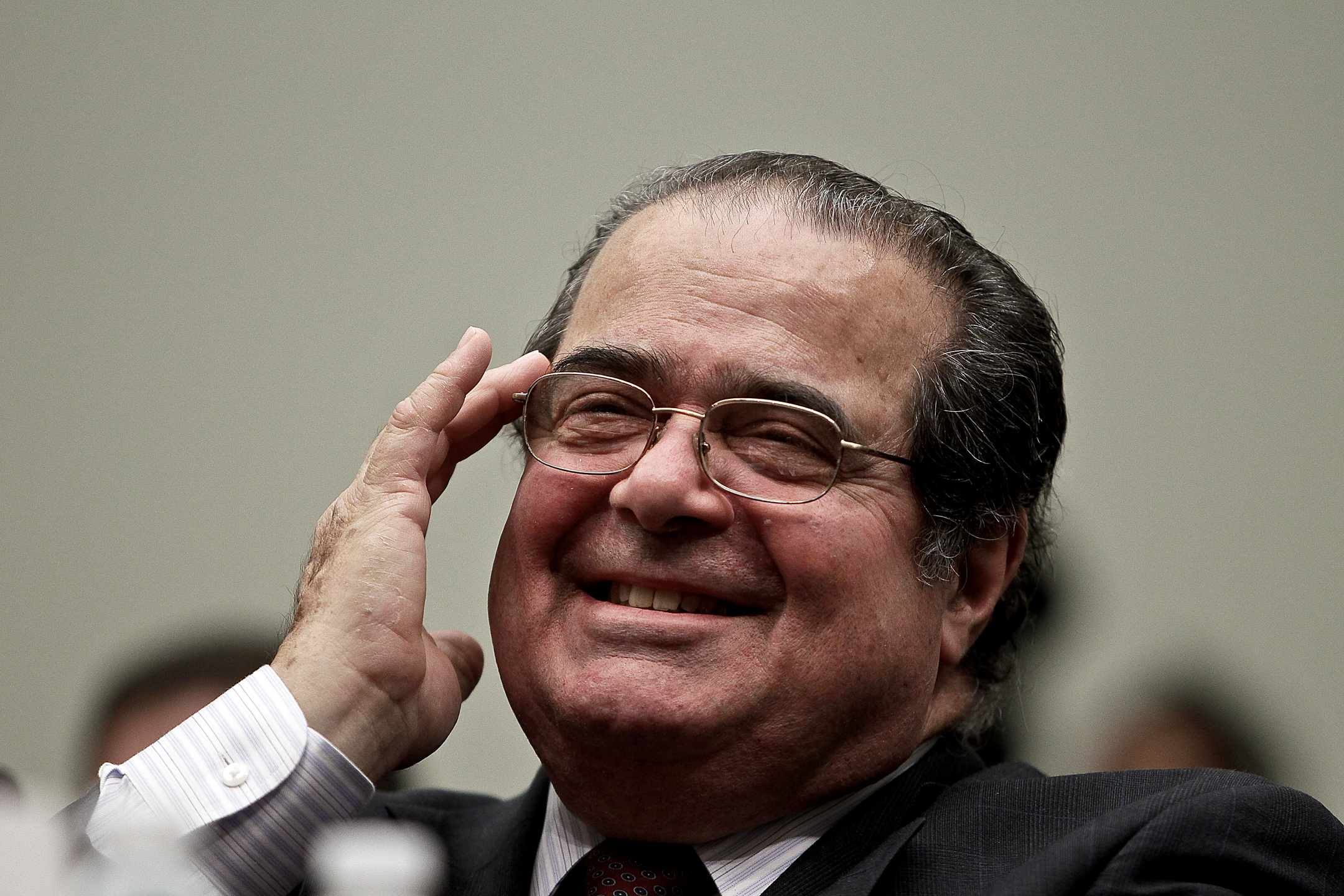

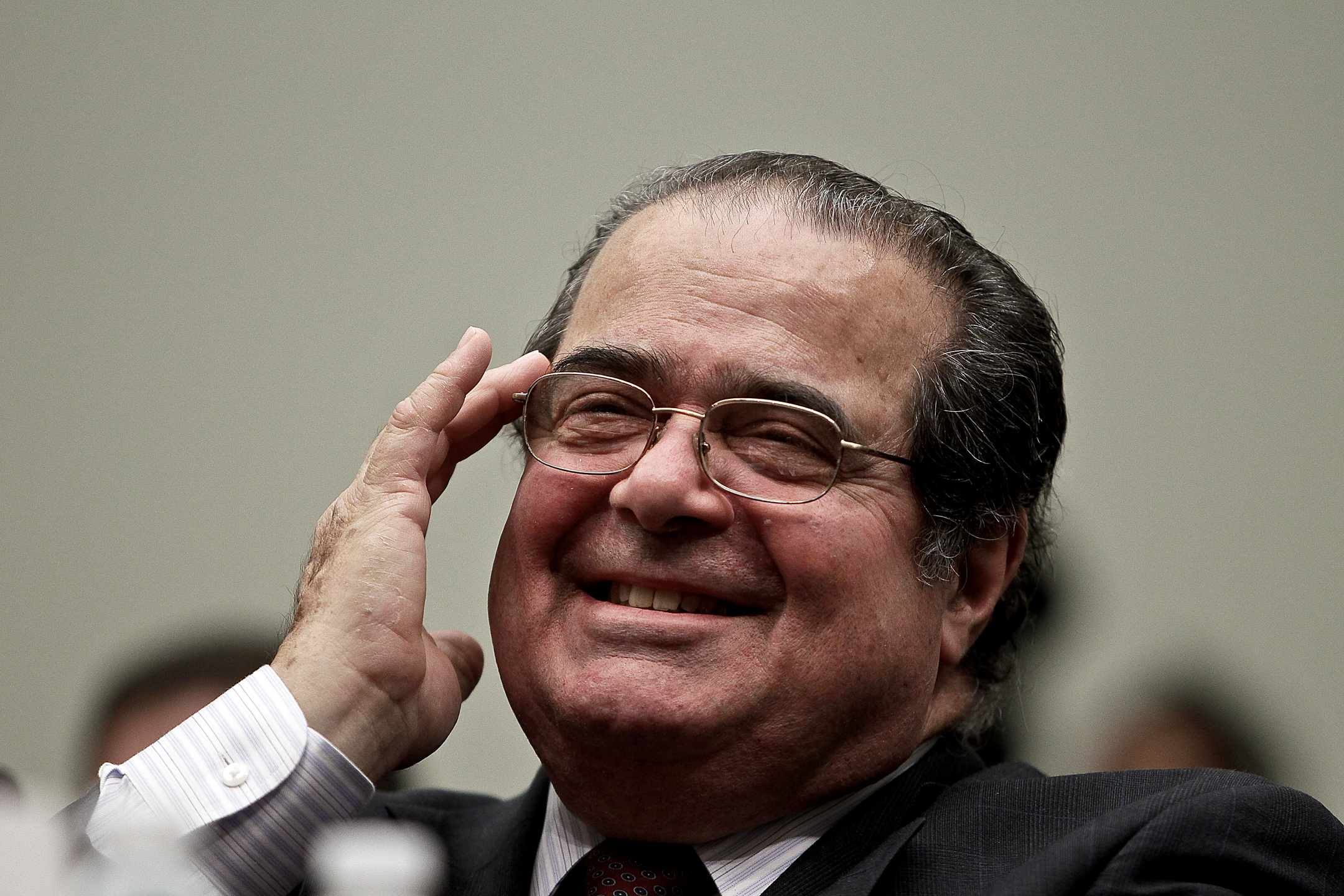

Antonin Gregory Scalia (; March 11, 1936 – February 13, 2016)

was an American jurist who served as an

associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is any member of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the Judiciary Act of 18 ...

from 1986 until his death in 2016. He was described as the intellectual anchor for the

originalist and

textualist position in the

U.S. Supreme Court's conservative wing. For catalyzing an originalist and textualist movement in American law, he has been described as one of the most influential jurists of the twentieth century,

and one of the most important

justices in the history of the Supreme Court.

Scalia was

posthumously awarded the

Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2018 by President

Donald Trump, and the

Antonin Scalia Law School

The Antonin Scalia Law School (previously George Mason University School of Law) is the law school of George Mason University, a public research university in Virginia. It is located in Arlington, Virginia, roughly west of Washington, D.C., a ...

at

George Mason University

George Mason University (George Mason, Mason, or GMU) is a public research university in Fairfax County, Virginia with an independent City of Fairfax, Virginia postal address in the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area. The university was origin ...

was named in his honor.

Scalia was born in

Trenton, New Jersey. A devout

Catholic, he attended

Xavier High School before receiving his undergraduate degree from

Georgetown University. Scalia went on to graduate from

Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each class ...

and spent six years at

Jones Day

Jones Day is an American multinational law firm. As of 2021, it was the eighth largest law firm in the U.S. and the 13th highest grossing law firm in the world. Originally headquartered in Cleveland, Ohio, Jones Day ranks first in both M&A le ...

before becoming a law professor at the

University of Virginia School of Law

The University of Virginia School of Law (Virginia Law or UVA Law) is the law school of the University of Virginia, a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson as part of his "academical v ...

. In the early 1970s, he served in the

Nixon and

Ford administrations, eventually becoming an

Assistant Attorney General under President

Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

. He spent most of the

Carter years teaching at the

University of Chicago, where he became one of the first faculty advisers of the fledgling

Federalist Society. In 1982, President

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

appointed Scalia as a judge of the

U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (in case citations, D.C. Cir.) is one of the thirteen United States Courts of Appeals. It has the smallest geographical jurisdiction of any of the U.S. federal appellate cou ...

. Four years later, Reagan appointed him to the Supreme Court where he became its first

Italian-American justice following a unanimous confirmation by the

U.S. Senate 98–0.

Scalia espoused a conservative jurisprudence and ideology, advocating

textualism in

statutory interpretation and

originalism in

constitutional interpretation

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

. He peppered his colleagues with "Ninograms" (memos named for his nickname, "Nino") intending to persuade them to his point of view. He was a strong defender of the powers of the executive branch and believed that the

U.S. Constitution permitted the

death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

and did not guarantee the right to either

abortion or

same-sex marriage. Furthermore, Scalia viewed

affirmative action and other policies that afforded special protected status to

minority groups as unconstitutional. Such positions would earn him a reputation as one of the most conservative justices on the Court. He filed separate opinions in many cases, often castigating the Court's majority—sometimes scathingly so. Scalia's most significant opinions include his lone dissent in ''

Morrison v. Olson

''Morrison v. Olson'', 487 U.S. 654 (1988), was a Supreme Court of the United States decision that determined the Independent Counsel Act was constitutional. ''Morrison'' also set important precedent determining the scope of Congress's ability ...

'' (arguing against the constitutionality of an

Independent-Counsel law), and his majority opinions in ''

Crawford v. Washington

''Crawford v. Washington'', 541 U.S. 36 (2004), is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision that reformulated the standard for determining when the admission of hearsay statements in criminal cases is permitted under the Confrontation Clau ...

'' (defining a criminal defendant's

confrontation right under the

Sixth Amendment) and ''

District of Columbia v. Heller

''District of Columbia v. Heller'', 554 U.S. 570 (2008), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects an individual's right to keep and bear arms, unconnected with service i ...

'' (holding that the

Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees a right to individual handgun ownership).

Early life and education

Scalia was born on March 11, 1936, in

Trenton, New Jersey.

He was the only child of Salvatore Eugenio (Eugene) Scalia (1903–1986), an Italian immigrant from

Sommatino,

Sicily, who graduated from

Rutgers University and was a graduate student at

Columbia University and clerk at the time of his son's birth.

The elder Scalia would become a professor of

Romance language

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European languages, I ...

s at

Brooklyn College

Brooklyn College is a public university in Brooklyn, Brooklyn, New York. It is part of the City University of New York system and enrolls about 15,000 undergraduate and 2,800 graduate students on a 35-acre campus.

Being New York City's first publ ...

, where he was an adherent to the

formalist New Criticism

New Criticism was a formalist movement in literary theory that dominated American literary criticism in the middle decades of the 20th century. It emphasized close reading, particularly of poetry, to discover how a work of literature functioned as ...

school of literary theory. Scalia's mother, Catherine Louise (

née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Panaro) Scalia (1905–1985), was born in Trenton to Italian immigrant parents and worked as an elementary school teacher.

In 1939, Scalia and his family moved to

Elmhurst, Queens, where he attended P.S. 13 Clement C. Moore School. After completing

eighth grade

Eighth grade (or grade eight in some regions) is the eighth post-kindergarten year of formal education in the US. The eighth grade is the ninth school year, the second, third, fourth, or final year of middle school, or the second and/or final ye ...

, he obtained an academic scholarship to

Xavier High School—a

Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

military school in

Manhattan—from which he graduated ranked first in his class in 1953.

He later reflected that he spent much of his time on schoolwork and admitted, "I was never cool."

While a youth, he was also active as a

Boy Scout

A Scout (in some countries a Boy Scout, Girl Scout, or Pathfinder) is a child, usually 10–18 years of age, participating in the worldwide Scouting movement. Because of the large age and development span, many Scouting associations have split ...

and was part of the Scouts' national honor society, the

Order of the Arrow. Classmate and future New York State official William Stern remembered Scalia in his high school days: "This kid was a conservative when he was 17 years old. An archconservative Catholic. He could have been a member of the

Curia. He was the top student in the class. He was brilliant, way above everybody else."

In 1953, Scalia enrolled at

Georgetown University, where he majored in

history. He became a champion collegiate debater in Georgetown's

Philodemic Society

The Philodemic Society is a student debating society at Georgetown University founded in 1830 by Father James Ryder, S.J. The Philodemic is among the oldest such societies in the United States, and is the oldest secular student organization at ...

and a critically praised thespian. He took his junior year abroad in

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

at the

University of Fribourg.

Scalia graduated from Georgetown in 1957 as class

valedictorian with a

Bachelor of Arts,

''summa cum laude''. Scalia then studied law at

Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each class ...

, where he was a notes editor for the ''

Harvard Law Review

The ''Harvard Law Review'' is a law review published by an independent student group at Harvard Law School. According to the ''Journal Citation Reports'', the ''Harvard Law Review''s 2015 impact factor of 4.979 placed the journal first out of 143 ...

''.

He graduated from Harvard Law in 1960 with a

Bachelor of Laws, ''magna cum laude''. Harvard awarded Scalia a Sheldon Fellowship, which allowed him to travel in Europe during 1960 and 1961.

Early legal career (1961–1982)

Scalia began his legal career at the law firm Jones, Day, Cockley and Reavis (now

Jones Day

Jones Day is an American multinational law firm. As of 2021, it was the eighth largest law firm in the U.S. and the 13th highest grossing law firm in the world. Originally headquartered in Cleveland, Ohio, Jones Day ranks first in both M&A le ...

) in

Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, where he worked from 1961 to 1967.

He was highly regarded at the law firm and would most likely have been made a partner but later said he had long intended to teach. He left the law firm to become a professor of law at the

University of Virginia School of Law

The University of Virginia School of Law (Virginia Law or UVA Law) is the law school of the University of Virginia, a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson as part of his "academical v ...

in 1967, moving his family to

Charlottesville.

[.]

After four years in Charlottesville, Scalia entered public service in 1971. President

Richard Nixon appointed him general counsel for the

Office of Telecommunications Policy After President Nixon took office in 1969, Clay T. Whitehead, Special Assistant to the President, pushed to establish an executive office dedicated to telecommunications policy. The White House Office of Telecommunications Policy (OTP) was establis ...

, where one of his principal assignments was to formulate federal policy for the growth of cable television. From 1972 to 1974, he was chairman of the

Administrative Conference of the United States, a small

independent agency that sought to improve the functioning of the federal bureaucracy.

In mid-1974, Nixon nominated him as

Assistant Attorney General for the

Office of Legal Counsel

The Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) is an office in the United States Department of Justice that assists the Attorney General's position as legal adviser to the President and all executive branch agencies. It drafts legal opinions of the Attorney ...

.

After Nixon's resignation, the nomination was continued by President

Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

, and Scalia was confirmed by the Senate on August 22, 1974.

In the aftermath of

Watergate

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's continual ...

, the Ford administration was engaged in a number of conflicts with Congress. Scalia repeatedly testified before congressional committees, defending Ford administration assertions of

executive privilege regarding its refusal to turn over documents. Within the administration, Scalia advocated a presidential veto for a bill to amend the

Freedom of Information Act Freedom of Information Act may refer to the following legislations in different jurisdictions which mandate the national government to disclose certain data to the general public upon request:

* Freedom of Information Act 1982, the Australian act

* ...

, which would greatly increase the act's scope. Scalia's view prevailed, and Ford vetoed the bill, but Congress overrode it. In early 1976, Scalia argued his only case before the Supreme Court, ''Alfred Dunhill of London, Inc. v. Republic of Cuba''. Scalia, on behalf of the US government, argued in support of Dunhill, and that position was successful.

Following Ford's defeat by President

Jimmy Carter, Scalia worked for several months at the

American Enterprise Institute.

He then returned to academia, taking up residence at the

University of Chicago Law School from 1977 to 1982,

though he spent one year as a

visiting professor at

Stanford Law School. During Scalia's time at Chicago,

Peter H. Russell

Peter Howard Russell (born 1932) is a Canadian political scientist, serving as professor emeritus of political science at the University of Toronto, where he taught from 1958 to 1997. He was a member of the Toronto chapter of Alpha Delta Phi. H ...

hired him on behalf of the Canadian government to write a report on how the United States was able to limit the activities of its secret services for the

McDonald Commission

The Royal Commission of Inquiry into Certain Activities of the RCMP, better known as the McDonald Commission, was a Royal Commission called by the Canadian government of Pierre Trudeau to investigate the Royal Canadian Mounted Police after a num ...

, which was investigating abuses by the

Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The report—finished in 1979—encouraged the commission to recommend that a balance be struck between civil liberties and the essentially unchecked activities of the RCMP. In 1981, he became the first faculty adviser for the University of Chicago's chapter of the newly founded

Federalist Society.

U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit (1982–1986)

When

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

was elected president in November 1980, Scalia hoped for a major position in the new administration. He was interviewed for the position of

Solicitor General of the United States, but the position went to

Rex E. Lee

Rex Edwin Lee (February 27, 1935 – March 11, 1996) was an American lawyer and academic who served as the 37th Solicitor General of the United States from 1981 until 1985. He was responsible for bringing the solicitor general's office to the cent ...

, to Scalia's great disappointment. Scalia was offered a judgeship on the Chicago-based

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit (in case citations, 7th Cir.) is the U.S. federal court with appellate jurisdiction over the courts in the following districts:

* Central District of Illinois

* Northern District of Ill ...

in early 1982 but declined it, hoping to be appointed to the more influential

U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (in case citations, D.C. Cir.) is one of the thirteen United States Courts of Appeals. It has the smallest geographical jurisdiction of any of the U.S. federal appellate cou ...

. Later that year, Reagan offered Scalia a seat on the D.C. Circuit, which Scalia accepted. He was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on August 5, 1982, and was sworn in on August 17, 1982.

On the D.C. Circuit, Scalia built a conservative record while winning applause in legal circles for powerful, witty legal writing, which was often critical of the Supreme Court precedents he felt bound as a lower-court judge to follow. Scalia's opinions drew the attention of Reagan administration officials, who, according to ''

The New York Times'', "liked virtually everything they saw and ... listed him as a leading Supreme Court prospect".

Nomination to the Supreme Court of the United States (1986)

In 1986,

Chief Justice Warren Burger informed the White House of his intent to retire. Reagan first decided to nominate Associate Justice

William Rehnquist to become Chief Justice. That choice meant that Reagan would also have to choose a nominee to fill Rehnquist's seat as associate justice.

Attorney General

Edwin Meese

Edwin Meese III (born December 2, 1931) is an American attorney, law professor, author and member of the Republican Party who served in official capacities within the Ronald Reagan's gubernatorial administration (1967–1974), the Reagan pres ...

, who advised Reagan on the choice, seriously considered only Scalia and

Robert Bork, a fellow judge on the DC Circuit. Feeling that this might well be Reagan's last opportunity to pick a Supreme Court justice, the president and his advisers chose Scalia over Bork. Many factors influenced the decision. Reagan wanted to appoint the first Italian-American justice. In addition, Scalia was ten years younger and would likely serve longer on the Court.

Scalia also had the advantage of not having Bork's "paper trail"; the elder judge had written controversial articles about individual rights. Scalia was called to the White House and accepted Reagan's nomination.

[. Bork was nominated for the Supreme Court the following year, but his nomination was rejected by the Senate.]

When

Senate Judiciary Committee hearings on Scalia's nomination opened in August 1986, he faced a committee that had just argued divisively over the Rehnquist nomination. Witnesses and Democratic senators contended that before becoming a judge, Rehnquist had engaged in activities designed to discourage minorities from voting. Committee members had little taste for a second battle over Scalia and were in any event reluctant to oppose the first Italian-American Supreme Court nominee. The judge was not pressed heavily on controversial issues such as abortion or civil rights. Scalia, who attended the hearing with his wife and nine children seated behind him, found time for a humorous exchange with Sen.

Howard Metzenbaum (D-OH), whom he had defeated in a tennis match in, as the nominee put it, "a case of my integrity overcoming my judgment".

Scalia met no opposition from the committee. The Senate debated Scalia's nomination only briefly, confirming him 98–0 on September 17, thereby making him the Court's first Italian-American Justice. That vote followed Rehnquist's confirmation as Chief Justice by a vote of 65–33 on the same day. Scalia took his seat on September 26, 1986. One committee member, Senator and future President

Joe Biden (D-DE), later stated that he regretted not having opposed Scalia "because he was so effective".

Views

Governmental structure and powers

Separation of powers

It was Scalia's view that clear lines of separation among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches follow directly from the Constitution, with no branch allowed to exercise powers granted to another branch. In his early days on the Court, he authored a powerful—and solitary—dissent in ''

Morrison v. Olson

''Morrison v. Olson'', 487 U.S. 654 (1988), was a Supreme Court of the United States decision that determined the Independent Counsel Act was constitutional. ''Morrison'' also set important precedent determining the scope of Congress's ability ...

'' (1988), in which the Court's majority upheld the

Independent Counsel law. Scalia's thirty-page draft dissent surprised Justice

Harry Blackmun

Harry Andrew Blackmun (November 12, 1908 – March 4, 1999) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1970 to 1994. Appointed by Republican President Richard Nixon, Blac ...

for its emotional content; Blackmun felt "it could be cut down to ten pages if Scalia omitted the screaming".

[.] Scalia indicated that the law was an unwarranted encroachment on the executive branch by the legislative. He warned, "Frequently an issue of this sort will come before the Court clad, so to speak, in sheep's clothing ... But this wolf comes as a wolf".

The 1989 case of ''

Mistretta v. United States

''Mistretta v. United States'', 488 U.S. 361 (1989), is a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court concerning the constitutionality of the United States Sentencing Commission.

Background

John Mistretta wa ...

'' challenged the

United States Sentencing Commission, an independent body within the judicial branch whose members (some of whom were federal judges) were removable only for good cause. The petitioner argued that the arrangement violated the separation of powers and that the

United States Sentencing Guidelines

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two fi ...

promulgated by the commission were invalid. Eight justices joined in the majority opinion written by Blackmun, upholding the Guidelines as constitutional. Scalia dissented, stating that the issuance of the Guidelines was a lawmaking function that Congress could not delegate and dubbed the Commission "a sort of junior-varsity Congress".

In 1996, Congress passed the

Line Item Veto Act

The Line Item Veto Act was a federal law of the United States that granted the President the power to line-item veto budget bills passed by Congress, but its effect was brief as the act was soon ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in '' ...

, which allowed the president to cancel items from an

appropriations bill

An appropriation, also known as supply bill or spending bill, is a proposed law that authorizes the expenditure of government funds. It is a bill that sets money aside for specific spending. In some democracies, approval of the legislature is ne ...

(a bill authorizing spending) once passed into law. The statute was challenged the following year. The matter rapidly reached the Supreme Court, which

struck down

''Struck Down'' is the second studio album by American hard rock/ heavy metal band Yesterday and Today, released in 1978. It was one of the last rock albums to be released by London Records.

The band would change their name to Y&T for their nex ...

the law as violating the

Presentment Clause of the Constitution, which governs what the president is permitted to do with a bill once it has passed both houses of Congress. Scalia dissented, seeing no Presentment Clause difficulties and feeling that the act did not violate the separation of powers. He argued that authorizing the president to cancel an appropriation was no different from allowing him to spend an appropriation at his discretion, which had long been accepted as constitutional.

Detainee cases

In 2004, in ''

Rasul v. Bush

''Rasul v. Bush'', 542 U.S. 466 (2004), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court in which the Court held that foreign nationals held in the Guantanamo Bay detention camp could petition federal courts for writs of ''habeas corpus ...

'', the Court held that federal courts had

jurisdiction to hear ''

habeas corpus'' petitions brought by detainees at the

Guantanamo Bay detainment camp. Scalia accused the majority of "spring

ng/nowiki> a trap on the Executive" by ruling that it could hear cases involving persons at Guantanamo when no federal court had ever ruled that it had the authority to hear cases involving people there.

Scalia (joined by Justice John Paul Stevens

John Paul Stevens (April 20, 1920 – July 16, 2019) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1975 to 2010. At the time of his retirement, he was the second-oldes ...

) also dissented in the 2004 case of ''Hamdi v. Rumsfeld

''Hamdi v. Rumsfeld'', 542 U.S. 507 (2004), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court recognized the power of the U.S. government to detain enemy combatants, including U.S. citizens, but ruled that detainees who are U.S. citizens m ...

'', involving Yaser Hamdi

Yaser Esam Hamdi (born September 26, 1980) is a former American citizen who was captured in Afghanistan in 2001. The United States government claims that he was fighting with the Taliban against U.S. and Afghan Northern Alliance forces. He was d ...

, an American citizen detained in the United States on the allegation he was an enemy combatant. The Court held that although Congress had authorized Hamdi's detention, Fifth Amendment due process guarantees give a citizen such as Hamdi held in the United States as an enemy combatant the right to contest that detention before a neutral decision maker. Scalia opined that the AUMF (Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists) could not be read to suspend ''habeas corpus'' and that the Court, faced with legislation by Congress that did not grant the president power to detain Hamdi, was trying to "Make Everything Come Out Right".

In March 2006, Scalia gave a talk at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland. When asked about detainee rights, he responded: "Give me a break ... I had a son on that battlefield and they were shooting at my son, and I'm not about to give this man who was captured in a war a full jury trial. I mean it's crazy".Salim Ahmed Hamdan

Salim Ahmed Hamdan () (born February 25, 1968) is a Yemeni man, captured during the invasion of Afghanistan, declared by the United States government to be an illegal enemy combatant and held as a detainee at Guantanamo Bay from 2002 to November ...

, supposed driver to Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden (10 March 1957 – 2 May 2011) was a Saudi-born extremist militant who founded al-Qaeda and served as its leader from 1988 until Killing of Osama bin Laden, his death in 2011. Ideologically a Pan-Islamism ...

, who was challenging the military commissions

Military justice (also military law) is the legal system (bodies of law and procedure) that governs the conduct of the active-duty personnel of the armed forces of a country. In some nation-states, civil law and military law are distinct bo ...

at Guantanamo Bay.recuse

Judicial disqualification, also referred to as recusal, is the act of abstaining from participation in an official action such as a legal proceeding due to a conflict of interest of the presiding court official or administrative officer. Applica ...

himself, or step aside from hearing the case, which he declined to do. The Court held 5–3 in '' Hamdan v. Rumsfeld'' that the federal courts had jurisdiction to consider Hamdan's claims; Scalia, in dissent, contended that any Court authority to consider Hamdan's petition had been eliminated by the jurisdiction-stripping Detainee Treatment Act of 2005.

Federalism

In

In federalism

Federalism is a combined or compound mode of government that combines a general government (the central or "federal" government) with regional governments (Province, provincial, State (sub-national), state, Canton (administrative division), can ...

cases pitting the powers of the federal government against those of the states, Scalia often took the states' positions. In 1997, the Supreme Court considered the case of ''Printz v. United States

''Printz v. United States'', 521 U.S. 898 (1997), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that certain interim provisions of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act violated the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constit ...

'', a challenge to certain provisions of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, which required chief law enforcement officers of localities in states to perform certain duties. In ''Printz'', Scalia wrote the Court's majority decision. The Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional the provision that imposed those duties as violating the Tenth Amendment

The Tenth Amendment (Amendment X) to the United States Constitution, a part of the Bill of Rights, was ratified on December 15, 1791. It expresses the principle of federalism, also known as states' rights, by stating that the federal governmen ...

, which reserves to the states and to the people those powers not granted to the federal government. In 2005, Scalia concurred in ''Gonzales v. Raich

''Gonzales v. Raich'' (previously ''Ashcroft v. Raich''), 545 U.S. 1 (2005), was a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that under the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, Congress may criminalize the production and use of homegrown ca ...

'', which read the Commerce Clause to hold that Congress could ban the use of marijuana

Cannabis, also known as marijuana among other names, is a psychoactive drug from the cannabis plant. Native to Central or South Asia, the cannabis plant has been used as a drug for both recreational and entheogenic purposes and in various tra ...

even when states approve its use for medicinal purposes. Scalia opined that the Commerce Clause, together with the Necessary and Proper Clause, permitted the regulation. In addition, Scalia felt that Congress may regulate intrastate activities if doing so is a necessary part of a more general regulation of interstate commerce. He based that decision on '' Wickard v. Filburn'', which he now wrote "expanded the Commerce Clause beyond all reason".

Scalia rejected the existence of the negative Commerce Clause

The Dormant Commerce Clause, or Negative Commerce Clause, in American constitutional law, is a legal doctrine that courts in the United States have inferred from the Commerce Clause in Article I of the US Constitution. The primary focus of the doct ...

doctrine, calling it "a judicial fraud".

Scalia took a broad view of the Eleventh Amendment, which bars certain lawsuits against states in the federal courts. In his 1989 dissent in '' Pennsylvania v. Union Gas Co.'', Scalia stated that there was no intent on the part of the framers to have the states surrender any sovereign immunity and that the case that provoked the Eleventh Amendment, ''Chisholm v. Georgia

''Chisholm v. Georgia'', 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 419 (1793), is considered the first United States Supreme Court case of significance and impact. Since the case was argued prior to the formal pronouncement of judicial review by ''Marbury v. Madison'' (180 ...

'', came as a surprise to them. Professor Ralph Rossum, who wrote a survey of Scalia's constitutional views, suggests that the justice's view of the Eleventh Amendment was actually contradictory to the language of the Amendment.

Individual rights

Abortion

Scalia argued that there is no constitutional right to abortion and that if the people desire legalized abortion, a law should be passed to accomplish it.Planned Parenthood v. Casey

''Planned Parenthood v. Casey'', 505 U.S. 833 (1992), was a landmark case of the Supreme Court of the United States in which the Court upheld the right to have an abortion as established by the "essential holding" of ''Roe v. Wade'' (1973) and is ...

'', Scalia wrote:

Scalia repeatedly called upon his colleagues to strike down ''Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States conferred the right to have an abortion. The decision struck down many federal and st ...

''. Scalia hoped to find five votes to strike down ''Roe'' in the 1989 case of '' Webster v. Reproductive Health Services'' but was not successful in doing so. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor

Sandra Day O'Connor (born March 26, 1930) is an American retired attorney and politician who served as the first female associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1981 to 2006. She was both the first woman nominated and th ...

cast the deciding vote, allowing the abortion regulations at issue in the case to stand but not overruling ''Roe''. Scalia concurred only in part, writing, "Justice O'Connor's assertion, that a 'fundamental rule of judicial restraint' requires us to avoid reconsidering ''Roe'' cannot be taken seriously". He noted, "We can now look forward to at least another Term of carts full of mail from the public, and the streets full of demonstrators".

The Court returned to the issue of abortion in the 2000 case of '' Stenberg v. Carhart'', in which it invalidated a Nebraska statute outlawing partial-birth abortion. Justice Stephen Breyer

Stephen Gerald Breyer ( ; born August 15, 1938) is a retired American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1994 until his retirement in 2022. He was nominated by President Bill Clinton, and repl ...

wrote for the Court that the law was unconstitutional because it did not allow an exception for the health of the woman. Scalia dissented, comparing the ''Stenberg'' case to two of the most reviled cases in Supreme Court history: "I am optimistic enough to believe that, one day, ''Stenberg v. Carhart'' will be assigned its rightful place in the history of this Court's jurisprudence beside '' Korematsu'' and '' Dred Scott''. The method of killing a human child ... proscribed by this statute is so horrible that the most clinical description of it evokes a shudder of revulsion".

In 2007, the Court upheld a federal statute banning partial-birth abortion in ''Gonzales v. Carhart

''Gonzales v. Carhart'', 550 U.S. 124 (2007), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that upheld the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003. The case reached the high court after U.S. Attorney General, Alberto Gonzales, appealed a rul ...

''. University of Chicago law professor Geoffrey R. Stone

Geoffrey R. Stone (born 1946) is an American law professor and noted First Amendment scholar. He is currently the Edward H. Levi Distinguished Service Professor of Law at the University of Chicago Law School.

Biography

Stone completed a B.S. de ...

, a former colleague of Scalia's, criticized ''Gonzales'', stating that religion had influenced the outcome because all five justices in the majority were Catholic, whereas the dissenters were Protestant or Jewish. This angered Scalia to such an extent that he stated he would not speak at the University of Chicago as long as Stone was there.

Race, gender, and sexual orientation

Scalia generally voted to strike down laws that make distinctions by race, gender, or sexual orientation. In 1989, he concurred with the Court's judgment in '' City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co.'', in which the Court applied strict scrutiny

In U.S. constitutional law, when a law infringes upon a fundamental constitutional right, the court may apply the strict scrutiny standard. Strict scrutiny holds the challenged law as presumptively invalid unless the government can demonstrate th ...

to a city program requiring a certain percentage of contracts to go to minorities, and struck down the program. Scalia did not join the majority opinion, however. He disagreed with O'Connor's opinion for the Court, holding that states and localities could institute race-based programs if they identified past discrimination and if the programs were designed to remedy the past racism. Five years later, in ''Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Peña

''Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Peña'', 515 U.S. 200 (1995), was a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court case which held that racial classifications, impos ...

'', he concurred in the Court's judgment and in part with the opinion that extended strict scrutiny to federal programs. Scalia noted in that matter his view that government can never have a compelling interest in making up for past discrimination by racial preferences:

In the 2003 case of ''Grutter v. Bollinger

''Grutter v. Bollinger'', 539 U.S. 306 (2003), was a landmark case of the Supreme Court of the United States concerning affirmative action in student admissions. The Court held that a student admissions process that favors "underrepresented minor ...

'', involving racial preferences in the University of Michigan's law school, Scalia mocked the Court majority's finding that the school was entitled to continue using race as a factor in admissions to promote diversity and to increase "cross-racial understanding". Scalia noted,

Scalia argued that laws that make distinctions between genders should be subjected to intermediate scrutiny

Intermediate scrutiny, in U.S. constitutional law, is the second level of deciding issues using judicial review. The other levels are typically referred to as rational basis review (least rigorous) and strict scrutiny (most rigorous).

In order t ...

, requiring that the gender classification be substantially related to important government objectives. When, in 1996, the Court upheld a suit brought by a woman who wished to enter the Virginia Military Institute in the case of ''United States v. Virginia

''United States v. Virginia'', 518 U.S. 515 (1996), is a landmark case in which the Supreme Court of the United States struck down the long-standing male-only admission policy of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) in a 7–1 decision. Justice ...

'', Scalia filed a lone, lengthy dissent. Scalia said that the Court, in requiring Virginia to show an "extremely persuasive justification" for the single-sex admission policy, had redefined intermediate scrutiny in such a way "that makes it indistinguishable from strict scrutiny".

In one of the final decisions of the Burger Court, the Court ruled in 1986 in '' Bowers v. Hardwick'' that "homosexual sodomy" was not protected by the right of privacy

The right to privacy is an element of various legal traditions that intends to restrain governmental and private actions that threaten the privacy of individuals. Over 150 national constitutions mention the right to privacy. On 10 December 1948 ...

and could be criminally prosecuted by the states. In 1995, however, that ruling was effectively gutted by '' Romer v. Evans'', which struck down a Colorado state constitutional amendment, passed by popular vote, that forbade antidiscrimination laws' being extended to sexual orientation.[.] Scalia dissented from the opinion by Justice Kennedy, believing that ''Bowers'' had protected the right of the states to pass such measures and that the Colorado amendment was not discriminatory but merely prevented homosexuals from gaining favored status under Colorado law. Scalia later said of ''Romer'', "And the Supreme Court said, 'Yes, it is unconstitutional.' On the basis of—I don't know, the Sexual Preference Clause of the Bill of Rights, presumably. And the liberals loved it, and the conservatives gnashed their teeth".

In 2003, ''Bowers'' was formally overruled by ''Lawrence v. Texas

''Lawrence v. Texas'', 539 U.S. 558 (2003), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that most sanctions of criminal punishment for consensual, adult non- procreative sexual activity (commonly referred to as so ...

'', from which Scalia dissented. According to Mark V. Tushnet in his survey of the Rehnquist Court, during the oral argument in the case, Scalia seemed so intent on making the state's argument for it that the Chief Justice intervened. According to his biographer, Joan Biskupic, Scalia "ridiculed" the majority in his dissent for being so ready to cast aside ''Bowers'' when many of the same justices had refused to overturn ''Roe'' in ''Planned Parenthood v. Casey''. In March 2009, openly gay Congressman Barney Frank described him as a "homophobe". Maureen Dowd described Scalia in a 2003 column as " Archie Bunker in a high-backed chair". In an op-ed for '' The New York Times'', federal appeals judge Richard Posner and Georgia State University law professor Eric Segall called Scalia's positions on homosexuality radical and characterized Scalia's "political ideal as verg ngon majoritarian

Majoritarianism is a traditional political philosophy or agenda that asserts that a majority (sometimes categorized by religion, language, social class, or some other identifying factor) of the population is entitled to a certain degree of primac ...

theocracy". Former Scalia clerk Ed Whelan called this "a smear and a distraction." Professor John O. McGinnis responded as well, leading to further exchanges.

In the 2013 case of ''Hollingsworth v. Perry

''Hollingsworth v. Perry'' was a series of United States federal court cases that re-legalized same-sex marriage in the state of California. The case began in 2009 in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, which found that ...

'', which involved a California ballot initiative known as Proposition 8 that amended the California State Constitution to ban same-sex marriage, Scalia voted with the majority to uphold a lower court decision overturning the ban. The decision was based on the appellants' lack of standing to appeal and not on the substantive issue of the constitutionality of Proposition 8.Due Process Clause

In United States constitutional law, a Due Process Clause is found in both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, which prohibits arbitrary deprivation of "life, liberty, or property" by the government except as ...

of the Fifth Amendment.[''United States v. Windsor'', . Retrieved June 26, 2013.] Scalia's dissent, which was joined in full by Justice Thomas and in part by Chief Justice Roberts, opened:

Scalia argued that the judgment effectively characterized opponents of same-sex marriage as "enemies of the human race": He argued that the Court's ruling would affect state bans on same-sex marriage as well:

Scalia concluded by saying that the Supreme Court "has cheated both sides, robbing the winners of an honest victory, and the losers of the peace that comes from a fair defeat."

Scalia concluded by saying that the Supreme Court "has cheated both sides, robbing the winners of an honest victory, and the losers of the peace that comes from a fair defeat."[''Obergefell'']

slip op.

at 4 (Scalia, J., dissenting). He claimed there was "no basis" for the Court to strike down legislation that the Fourteenth Amendment did not expressly forbid, and directly attacked the majority opinion for "lacking even a thin veneer of law".John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longes ...

and Joseph Story to the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie."

Criminal law

Scalia believed the

Scalia believed the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

to be constitutional. He dissented in decisions that hold the death penalty unconstitutional as applied to certain groups, such as those who were under the age of 18 at the time of offense. In ''Thompson v. Oklahoma

''Thompson v. Oklahoma'', 487 U.S. 815 (1988), was the first case since the moratorium on capital punishment was lifted in the United States in which the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the death sentence of a minor on grounds of "cruel and unusual ...

'' (1988), he dissented from the Court's ruling that the death penalty could not be applied to those aged 15 at the time of the offense, and the following year authored the Court's opinion in ''Stanford v. Kentucky

''Stanford v. Kentucky'', 492 U.S. 361 (1989), was a United States Supreme Court case that sanctioned the imposition of the death penalty on offenders who were at least 16 years of age at the time of the crime.. This decision came one year afte ...

'', sustaining the death penalty for those who killed at age 16. However, in 2005, the Court overturned ''Stanford'' in ''Roper v. Simmons

''Roper v. Simmons'', 543 U.S. 551 (2005), was a landmark decision in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that it is unconstitutional to impose capital punishment for crimes committed while under the age of 18. The 5–4 decision ov ...

'', and Scalia again dissented, mocking the majority's claims that a national consensus had emerged against the execution of those who killed while underage, noting that less than half of the states that permitted the death penalty prohibited it for underage killers. He castigated the majority for including in their count states that had abolished the death penalty entirely, stating that doing so was "rather like including old-order Amishmen in a consumer-preference poll on the electric car. Of course they don't like it, but that sheds no light whatever on the point at issue". In 2002, in ''Atkins v. Virginia

''Atkins v. Virginia'', 536 U.S. 304 (2002), is a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States ruled 6-3 that executing people with intellectual disabilities violates the Eighth Amendment's ban on cruel and unusual punishments, but states ...

'', the Court ruled the death penalty unconstitutional as applied to mentally retarded people. Scalia dissented, stating that it would not have been considered cruel or unusual to execute mildly mentally retarded people at the time of the 1791 adoption of the Bill of Rights and that the Court had failed to show that a national consensus had formed against the practice.

Scalia strongly disfavored the Court's ruling in ''Miranda v. Arizona

''Miranda v. Arizona'', 384 U.S. 436 (1966), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution restricts prosecutors from using a person's statements made in response to i ...

'', which held that a confession by an arrested suspect who had not been advised of their rights was inadmissible in court, and he voted to overrule ''Miranda'' in the 2000 case of ''Dickerson v. United States

''Dickerson v. United States'', 530 U.S. 428 (2000), upheld the requirement that the Miranda warning be read to Criminal Law, criminal suspects and struck down a federal statute that purported to overrule ''Miranda v. Arizona'' (1966).

''Dickerso ...

'' but was in a minority of two with Justice Clarence Thomas. Calling the ''Miranda'' decision a "milestone of judicial overreaching", Scalia stated that the Court should not fear to correct its mistakes.

Although, in many areas, Scalia's approach was unfavorable to criminal defendants, he took the side of defendants in matters involving the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment, which guarantees defendants the right to confront their accusers. In multiple cases, Scalia wrote against laws that allowed alleged victims of child abuse to testify behind screens or by closed-circuit television. In a 2009 case, Scalia wrote the majority opinion in ''Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts

''Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts'', 557 U.S. 305 (2009), is a Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that it was a violation of the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Sixth Amend ...

'', holding that defendants must have the opportunity to confront lab technicians in drug cases and that a certificate of analysis is not enough to prove a substance was a drug.

Scalia maintained that every element of an offense that helps determine the sentence must be either admitted by the defendant or found by a jury under the Sixth Amendment's jury guarantee. In the 2000 case of ''Apprendi v. New Jersey

''Apprendi v. New Jersey'', 530 U.S. 466 (2000), is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision with regard to aggravating factors in crimes. The Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial, incorporated against the states th ...

'', Scalia wrote a concurrence to the Court's majority opinion that struck down a state statute that allowed the trial judge to increase the sentence if the judge found the offense was a hate crime

A hate crime (also known as a bias-motivated crime or bias crime) is a prejudice-motivated crime which occurs when a perpetrator targets a victim because of their membership (or perceived membership) of a certain social group or racial demograph ...

. Scalia found the procedure impermissible because whether it was a hate crime had not been decided by the jury.Blakely v. Washington

''Blakely v. Washington'', 542 U.S. 296 (2004), held that, in the context of mandatory sentencing guidelines under state law, the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial prohibited judges from enhancing criminal sentences based on facts other than t ...

'', striking down Washington state's sentencing guidelines on similar grounds. The dissenters in ''Blakely'' foresaw that Scalia would use the case to attack the federal sentencing guidelines (which he had failed to strike down in ''Mistretta''), and they proved correct, as Scalia led a five-member majority in ''United States v. Booker

''United States v. Booker'', 543 U.S. 220 (2005), is a United States Supreme Court decision on criminal sentencing. The Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment right to jury trial requires that other than a prior conviction, only facts admitted by a ...

'', which made those guidelines no longer mandatory for federal judges to follow (they remained advisory).[.]

In the 2001 case of ''Kyllo v. United States

''Kyllo v. United States'', 533 U.S. 27 (2001), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States in which the court ruled that the use of thermal imaging devices to monitor heat radiation in or around a person's home, even if conducted fro ...

'', Scalia wrote the Court's opinion in a 5–4 decision that cut across ideological lines. That decision found thermal imaging of a home to be an unreasonable search under the Fourth Amendment. The Court struck down a conviction for marijuana manufacture based on a search warrant issued after such scans were conducted, which showed that the garage was considerably hotter than the rest of the house because of indoor growing lights. Applying that Fourth Amendment prohibition on unreasonable search and seizure to arrest, Scalia dissented from the Court's 1991 decision in ''County of Riverside v. McLaughlin

''County of Riverside v. McLaughlin'', 500 U.S. 44 (1991), was a United States Supreme Court case which involved the question of within what period of time must a suspect arrested without a warrant (warrantless arrests) be brought into court to det ...

'', allowing a 48-hour delay before a person arrested without a warrant is taken before a magistrate, on the ground that at the time of the adoption of the Fourth Amendment, an arrested person was to be taken before a magistrate as quickly as practicable. In a 1990 First Amendment case, '' R.A.V. v. St. Paul'', Scalia wrote the Court's opinion striking down a St. Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul (abbreviated St. Paul) is the capital of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County. Situated on high bluffs overlooking a bend in the Mississippi River, Saint Paul is a regional business hub and the center o ...

, hate speech

Hate speech is defined by the ''Cambridge Dictionary'' as "public speech that expresses hate or encourages violence towards a person or group based on something such as race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation". Hate speech is "usually thoug ...

ordinance in a prosecution for burning a cross. Scalia noted, "Let there be no mistake about our belief that burning a cross in someone's front yard is reprehensible. But St. Paul has sufficient means at its disposal to prevent such behavior without adding the First Amendment to the fire".

Second Amendment

In 2008, the Court considered a challenge to the gun laws in the District of Columbia. Scalia wrote the majority opinion in ''District of Columbia v. Heller

''District of Columbia v. Heller'', 554 U.S. 570 (2008), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects an individual's right to keep and bear arms, unconnected with service i ...

'', which found an individual right to own a firearm under the Second Amendment. Scalia traced the word "militia", found in the Second Amendment, as it would have been understood at the time of its ratification, stating that it then meant "the body of all citizens".[.] Seventh Circuit Judge Richard Posner disagreed with Scalia's opinion, stating that the Second Amendment "creates no right to the private possession of guns". Posner called Scalia's opinion "faux originalism" and a "historicizing glaze on personal values and policy preferences". In October 2008, Scalia stated that the court's originalists needed to show only that at the time the Second Amendment was ratified, the right to bear arms did not have an exclusively military context and that they were successful in so showing.

Litigation and standing

Following the death of Scalia, Paul Barrett, writing for '' Bloomberg Businessweek'', reported that: "Translating into liberal argot: Scalia changed the rules for who could sue". The issue elevated the recognition of Scalia as a notable influence on establishing and determining the conditions under which cases could be brought to trial and for litigation—and by whom such litigation could take place. David Rivkin, from the conservative standpoint, said, "He (Scalia) did more to clarify and limit the bounds and scope of judicial power than any Supreme Court Justice in history, particularly in the area of standing and class actions". Scalia indicated his long-held position from the time of his 1983 law review article titled "The Doctrine of Standing as an Essential Element of the Separation of Powers". As summarized by Barrett, "He (Scalia) wrote that courts had misappropriated authority from other branches of government by allowing too many people to sue corporations and government agencies, especially in environmental cases". In a practical sense, Scalia brought to the attention of the Court the authority to restrict "standing" in class action suits in which the litigants may be defined in descriptive terms rather than as well-defined and unambiguous litigants.

Other cases

Scalia concurred in the 1990 case of ''Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health

''Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health'', 497 U.S. 261 (1990), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States involving a young adult incompetent. The first " right to die" case ever heard by the Court, ''Cruzan'' ...

'', in which the family of a woman in a vegetative state sought to have her feeding tube removed so she would die, believing that to have been her wish. The Court found for the State of Missouri, requiring clear and convincing evidence of such a desire. Scalia stated that the Court should have remained away from the dispute and that the issues "are ot/nowiki> better known to the nine Justices of this Court any better than they are known to nine people picked at random from the Kansas City telephone directory".[.]

Scalia joined the majority '' per curiam'' opinion in the 2000 case of ''Bush v. Gore

''Bush v. Gore'', 531 U.S. 98 (2000), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court on December 12, 2000, that settled a recount dispute in Florida's 2000 presidential election between George W. Bush and Al Gore. On December 8, th ...

'', which effectively ended recounts of ballots in Florida following the 2000 US presidential election

The 2000 United States presidential election was the 54th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 7, 2000. Republican candidate George W. Bush, the governor of Texas and eldest son of the 41st president, George H. W. Bush, ...

, and also both concurred separately and joined Rehnquist's concurrence. In 2007, he said of the case, "I and my court owe no apology whatever for ''Bush v. Gore''. We did the right thing. So there! ... get over it. It's so old by now". During an interview on the ''Charlie Rose'' show, he defended the Court's action:

Legal philosophy and approach

Judicial performance

During oral argument before the Court, Scalia asked more questions and made more comments than any other justice.

During oral argument before the Court, Scalia asked more questions and made more comments than any other justice.[.] A 2005 study found that he provoked laughter more often than any of his colleagues did. His goal during oral arguments was to get across his position to the other justices.[.] University of Kansas social psychologist Lawrence Wrightsman wrote that Scalia communicated "a sense of urgency on the bench" and had a style that was "forever forceful".Slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

'' described Scalia's technique as follows:

Scalia wrote numerous opinions from the start of his career on the Supreme Court. During his tenure, he wrote more concurring opinions than any other justice. Only two other justices have written more dissents.[.] According to Kevin Ring, who compiled a book of Scalia's dissenting and concurring opinions: "His opinions are ... highly readable. His entertaining writing style can make even the most mundane areas of the law interesting". Conor Clarke of ''Slate'' comments on Scalia's written opinions, especially his dissents:

At the Supreme Court, justices meet after the case is briefed and argued and vote on the result. The task of writing the opinion is assigned by the Chief Justice or—if the Chief Justice is in the minority or is not participating—by the senior justice in the majority. After the assignment, the justices generally communicate about a case by sending notes and draft opinions to each other's chambers. In the give-and-take of opinion-writing, Scalia did not compromise his views in order to attract five votes for a majority (unlike the late Justice William J. Brennan, Jr.

William Joseph "Bill" Brennan Jr. (April 25, 1906 – July 24, 1997) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1956 to 1990. He was the List of United States Supreme Cou ...

, who would accept less than what he wanted in order to gain a partial victory). Scalia attempted to influence his colleagues by sending them "Ninograms"—short memoranda aimed at persuading them of the correctness of his views.

Textualism

Scalia was a textualist in statutory interpretation, believing that the ordinary meaning of a statute should govern. In interpreting statutes, Scalia did not look to legislative history. In the 2006 case of '' Zedner v. United States'', he joined the majority opinion written by Justice Samuel Alito

Samuel Anthony Alito Jr. ( ; born April 1, 1950) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President George W. Bush on October 31, 2005, and has served ...

—all except one paragraph of the opinion, in which Alito cited legislative history. In a concurring opinion in that case, Scalia noted, "The use of legislative history is illegitimate and ill advised in the interpretation of any statute".

His dislike of legislative history may have been a reason that other justices have become more cautious in its use.statute

A statute is a formal written enactment of a legislative authority that governs the legal entities of a city, state, or country by way of consent. Typically, statutes command or prohibit something, or declare policy. Statutes are rules made by le ...

s and that no case of that era used legislative history as an essential reason for the outcome. Maggs suggested,

Originalism

In 1998, Scalia vociferously opposed the idea of a living constitution, or the power of the judiciary to modify the meaning of constitutional provisions to adapt them to changing times.

In 1998, Scalia vociferously opposed the idea of a living constitution, or the power of the judiciary to modify the meaning of constitutional provisions to adapt them to changing times.United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

as it would have been understood when it was adopted. According to Scalia in 2008, "It's what did the words mean to the people who ratified the Bill of Rights or who ratified the Constitution".Stephen Breyer

Stephen Gerald Breyer ( ; born August 15, 1938) is a retired American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1994 until his retirement in 2022. He was nominated by President Bill Clinton, and repl ...

questioned Scalia, indicating that those who ratified the Fourteenth Amendment did not intend to end school segregation. Scalia called this argument " waving the bloody shirt of ''Brown''" and indicated that he would have joined the first Justice Harlan's solitary dissent in '' Plessy v. Ferguson'', the 1896 case that ''Brown'' overruled.

Scalia's originalist approach came under attack from critics, who viewed it as "a cover for what they see as Scalia's real intention: to turn back some pivotal court decisions of the 1960s and 70s" reached by the Warren

A warren is a network of wild rodent or lagomorph, typically rabbit burrows. Domestic warrens are artificial, enclosed establishment of animal husbandry dedicated to the raising of rabbits for meat and fur. The term evolved from the medieval Angl ...

and Burger Courts.Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission

''Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission'', 558 U.S. 310 (2010), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States regarding campaign finance laws and free speech under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. It wa ...

''. Scalia, in his concurrence in that case, traced his understanding of the rights of groups of individuals at the time of the adoption of the Bill of Rights. His argument was based on the lack of an exception for groups such as corporations in the free speech guarantee in the Bill of Rights and on several examples of corporate political speech from the time of the adoption of the Bill of Rights. Professor Thomas Colby of George Washington University National Law Center

The George Washington University Law School (GW Law) is the law school of George Washington University, in Washington, D.C. Established in 1865, GW Law is the oldest top law school in the national capital. GW Law offers the largest range of cour ...

argued that Scalia's votes in Establishment Clause cases do not stem from originalist views but simply from conservative political convictions. Scalia responded to his critics that his originalism "has occasionally led him to decisions he deplores, like his upholding the constitutionality of flag burning

Flag desecration is the desecration of a flag, violation of flag protocol, or various acts that intentionally destroy, damage, or mutilate a flag in public. In the case of a national flag, such action is often intended to make a political point ...

", which according to Scalia was protected by the First Amendment.George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, Bush family, and son of the 41st president George H. W. Bush, he ...

appointees Roberts

Roberts may refer to:

People

* Roberts (given name), a Latvian masculine given name

* Roberts (surname), a popular surname, especially among the Welsh

Places

* Roberts (crater), a lunar impact crater on the far side of the Moon

;United Stat ...

and Alito had had time to make an impact, Rossum wrote that Scalia had failed to win converts among his conservative colleagues for his use of originalism, whereas Roberts and Alito, as younger men with an originalist approach, greatly admired Scalia battling for what he believed in. Following the appointments of Roberts and Alito, subsequent appointees Neil Gorsuch

Neil McGill Gorsuch ( ; born August 29, 1967) is an American lawyer and judge who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President Donald Trump on January 31, 2017, and has served since ...

and Brett Kavanaugh are identified in their judicial temperament as being originalists with Kavanuagh referred to as "a stalwart originalist" in the tradition of Scalia.

Public attention

Requests for recusals

Scalia recused himself from ''

Scalia recused himself from ''Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow

''Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow'', 542 U.S. 1 (2004), was a case decided by the U.S. Supreme Court.. The lawsuit, originally filed as ''Newdow v. United States Congress, Elk Grove Unified School District, et al.'' in 2000, led to a 2 ...

'' (2004), a case brought by atheist Michael Newdow alleging that recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance (including the words "under God") in school classrooms violated the rights of his daughter, who he said was also an atheist. Shortly after the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled in Newdow's favor but before the case came before the Supreme Court, Scalia spoke at a Knights of Columbus event in Fredericksburg, Virginia

Fredericksburg is an independent city located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 27,982. The Bureau of Economic Analysis of the United States Department of Commerce combines the city of Fredericksburg wi ...

, stating that the Ninth Circuit decision was an example of how the courts were trying to excise God from public life. The school district requested that the Supreme Court review the case, and Newdow asked that Scalia recuse himself because of this prior statement, which he did without comment.

Scalia declined to recuse himself from '' Cheney v. United States District Court for the District of Columbia'' (2005), a case concerning whether Vice President Dick Cheney

Richard Bruce Cheney ( ; born January 30, 1941) is an American politician and businessman who served as the 46th vice president of the United States from 2001 to 2009 under President George W. Bush. He is currently the oldest living former U ...

could keep secret the membership of an advisory task force on energy policy. Scalia was asked to recuse himself because he had gone on a hunting trip with various persons including Cheney, during which he traveled one way on Air Force Two. Scalia issued a lengthy in-chambers opinion {{no footnotes, date=March 2013

An in-chambers opinion is an opinion by a single justice or judge of a multi-member appellate court, rendered on an issue that the court's rules or procedures allow a single member of the court to decide. The judge is ...

refusing to recuse himself, stating that though Cheney was a longtime friend, he was being sued merely in his official capacity and that were justices to step aside in the cases of officials who are parties because of official capacity, the Supreme Court would cease to function. Scalia indicated that it was far from unusual for justices to socialize with other government officials, recalling that the late Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson

Frederick "Fred" Moore Vinson (January 22, 1890 – September 8, 1953) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 13th chief justice of the United States from 1946 until his death in 1953. Vinson was one of the few Americans to ...

played poker with President Harry Truman and that Justice Byron White went skiing with Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. Scalia stated that he was never alone with Cheney during the trip, the two had not discussed the case, and the justice had saved no money because he had bought round-trip tickets, the cheapest available. Scalia was part of the 7–2 majority once the case was heard, a decision that generally upheld Cheney's position. Scalia later described his refusal to recuse himself as his "most heroic opinion" because it had exposed him to a great deal of criticism.

Judge Gilbert S. Merritt Jr.

Gilbert Stroud Merritt Jr. (January 17, 1936 – January 17, 2022) was an American lawyer and jurist. He served as a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit from 1977 to 2022.

Early life

Merritt ...

of the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals called for Scalia's recusal in ''Bush v. Gore'' at the time.he law

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

required recusal". Republicans dismissed such calls as partisan, noting that Merritt was a close friend of the Gores and a rumored Gore Supreme Court nominee.

Religious views

Scalia was a devout traditionalist Catholic, and his son Paul entered the priesthood. Uncomfortable with the changes brought about following

Scalia was a devout traditionalist Catholic, and his son Paul entered the priesthood. Uncomfortable with the changes brought about following Vatican II

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions), each lasting between 8 and ...

, Scalia drove long distances to parishes he felt were more in accord with his beliefs, including parishes that celebrated the Tridentine Latin Mass

The Tridentine Mass, also known as the Traditional Latin Mass or Traditional Rite, is the liturgy of Mass in the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church that appears in typical editions of the Roman Missal published from 1570 to 1962. Celebrated alm ...

in Chicago and Washington, and one celebrating the Latin version of the Mass of Paul VI

The Mass of Paul VI, also known as the Ordinary Form or Novus Ordo, is the most commonly used liturgy in the Catholic Church. It is a form of the Latin Church's Roman Rite and was promulgated by Pope Paul VI in 1969, published by him in the 1970 ...

at St. Catherine of Siena in Great Falls, Virginia. In a 2013 interview with Jennifer Senior for ''New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

'', Scalia was asked whether his beliefs extended to the Devil, and he stated, "Of course! Yeah, he's a real person. Hey, c'mon, that's standard Catholic doctrine! Every Catholic believes that." When asked whether he had seen recent evidence of the Devil, Scalia replied: "You know, it is curious. In the Gospels, the Devil is doing all sorts of things. He's making pigs run off cliffs, he's possessing people and whatnot ... What he's doing now is getting people not to believe in him or in God. He's much more successful that way."Boston Herald

The ''Boston Herald'' is an American daily newspaper whose primary market is Boston, Massachusetts, and its surrounding area. It was founded in 1846 and is one of the oldest daily newspapers in the United States. It has been awarded eight Pulit ...

'' as obscene. Scalia responded to the reports with a letter to the editor, accusing the news staff of watching too many episodes of '' The Sopranos'' and stating that the gesture was a strong brush-off. Roger Axtell, an expert on body language, described the gesture as possibly meaning "I've had enough, go away" and noted, "It's a fairly strong gesture". The gesture was parodied by comedian Stephen Colbert during his performance at the White House Correspondents' Association Dinner later that year, with the justice in attendance; cameras showed that unlike most of the butts of Colbert's jokes that evening, Scalia was laughing.

1996 presidential election

According to John Boehner

John Andrew Boehner ( ; born , 1949) is an American retired politician who served as the 53rd speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 2011 to 2015. A member of the Republican Party, he served 13 terms as the U.S. represe ...

, as chairman of the House Republican Conference, he sought to persuade Scalia to run for election as vice president with Bob Dole

Robert Joseph Dole (July 22, 1923 – December 5, 2021) was an American politician and attorney who represented Kansas in the United States Senate from 1969 to 1996. He was the Republican Leader of the Senate during the final 11 years of his te ...

in 1996. As related by Boehner, Scalia listened to the proposal and dictated the same reply Justice Charles Evans Hughes had once given to a similar query: "The possibility is too remote to comment upon, given my position". Dole did put Scalia on his list of potential running mates but eventually settled on Jack Kemp

Jack French Kemp (July 13, 1935 – May 2, 2009) was an American politician and a professional football player. A member of the Republican Party from New York, he served as Housing Secretary in the administration of President George H. W. Bu ...

.

Personal life

On September 10, 1960, Scalia married Maureen McCarthy at St. Pius X church in Yarmouth, Massachusetts.Radcliffe College

Radcliffe College was a women's liberal arts college in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and functioned as the female coordinate institution for the all-male Harvard College. Considered founded in 1879, it was one of the Seven Sisters colleges and he ...

when they met; she subsequently obtained a degree in English from the school.

The Scalias had five sons and four daughters. Two of their sons, Eugene Scalia and John Scalia, became attorneys,Secretary of Labor