Polio worldwide 2017.svg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Poliomyelitis, commonly shortened to polio, is an

Poliomyelitis is caused by infection with a member of the

Poliomyelitis is caused by infection with a member of the

Poliovirus enters the body through the mouth, infecting the first cells with which it comes in contact – the

Poliovirus enters the body through the mouth, infecting the first cells with which it comes in contact – the

In around one percent of infections, poliovirus spreads along certain nerve fiber pathways, preferentially replicating in and destroying motor neurons within the

In around one percent of infections, poliovirus spreads along certain nerve fiber pathways, preferentially replicating in and destroying motor neurons within the

Spinal polio, the most common form of paralytic poliomyelitis, results from viral invasion of the motor neurons of the anterior horn cells, or the

Spinal polio, the most common form of paralytic poliomyelitis, results from viral invasion of the motor neurons of the anterior horn cells, or the

Making up about two percent of cases of paralytic polio, bulbar polio occurs when poliovirus invades and destroys nerves within the

Making up about two percent of cases of paralytic polio, bulbar polio occurs when poliovirus invades and destroys nerves within the

Two types of vaccine are used throughout the world to combat polio. Both types induce immunity to polio and are effective in protecting individuals from disease.

The first candidate

Two types of vaccine are used throughout the world to combat polio. Both types induce immunity to polio and are effective in protecting individuals from disease.

The first candidate  Because the oral polio vaccine is inexpensive, easy to administer, and produces excellent immunity in the intestine (which helps prevent infection with wild virus in areas where it is

Because the oral polio vaccine is inexpensive, easy to administer, and produces excellent immunity in the intestine (which helps prevent infection with wild virus in areas where it is

Patients with abortive polio infections recover completely. In those who develop only aseptic meningitis, the symptoms can be expected to persist for two to ten days, followed by complete recovery. In cases of spinal polio, if the affected nerve cells are completely destroyed, paralysis will be permanent; cells that are not destroyed, but lose function temporarily, may recover within four to six weeks after onset. Reproduced online with permission by Post-Polio Health International; retrieved on 10 November 2007. Half the patients with spinal polio recover fully; one-quarter recover with mild disability, and the remaining quarter are left with severe disability. The degree of both acute paralysis and residual paralysis is likely to be proportional to the degree of

Patients with abortive polio infections recover completely. In those who develop only aseptic meningitis, the symptoms can be expected to persist for two to ten days, followed by complete recovery. In cases of spinal polio, if the affected nerve cells are completely destroyed, paralysis will be permanent; cells that are not destroyed, but lose function temporarily, may recover within four to six weeks after onset. Reproduced online with permission by Post-Polio Health International; retrieved on 10 November 2007. Half the patients with spinal polio recover fully; one-quarter recover with mild disability, and the remaining quarter are left with severe disability. The degree of both acute paralysis and residual paralysis is likely to be proportional to the degree of

Paralysis, length differences and deformations of the lower extremities can lead to a hindrance when walking with compensation mechanisms that lead to a severe impairment of the gait pattern. In order to be able to stand and walk safely and to improve the gait pattern,

Paralysis, length differences and deformations of the lower extremities can lead to a hindrance when walking with compensation mechanisms that lead to a severe impairment of the gait pattern. In order to be able to stand and walk safely and to improve the gait pattern,

In 2003 in

In 2003 in

The effects of polio have been known since

The effects of polio have been known since

infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable di ...

caused by the poliovirus

A poliovirus, the causative agent of polio (also known as poliomyelitis), is a serotype of the species '' Enterovirus C'', in the family of ''Picornaviridae''. There are three poliovirus serotypes: types 1, 2, and 3.

Poliovirus is composed of a ...

. Approximately 70% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe symptoms develop such as headache, neck stiffness, and paresthesia. These symptoms usually pass within one or two weeks. A less common symptom is permanent paralysis, and possible death in extreme cases.. Years after recovery, post-polio syndrome

Post-polio syndrome (PPS, poliomyelitis sequelae) is a group of latent symptoms of poliomyelitis (polio), occurring at about a 25–40% rate (latest data greater than 80%). These symptoms are caused by the damaging effects of the viral infection ...

may occur, with a slow development of muscle weakness similar to that which the person had during the initial infection.

Polio occurs naturally only in humans. It is highly infectious, and is spread from person to person either through fecal-oral transmission (e.g. poor hygiene, or by ingestion of food or water contaminated by human feces), or via the oral-oral route. Those who are infected may spread the disease for up to six weeks even if no symptoms are present. The disease may be diagnosed by finding the virus in the feces or detecting antibodies against it in the blood.

Poliomyelitis has existed for thousands of years, with depictions of the disease in ancient art. The disease was first recognized as a distinct condition by the English physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

Michael Underwood

Michael Paul Underwood (born 26 October 1975) is an English television presenter, best known as a children's TV presenter on CBBC and CITV. He can be seen as a fifteen-year-old in an episode of '' The Crystal Maze'', then presented by Richa ...

in 1789, and the virus that causes it was first identified in 1909 by the Austrian immunologist Karl Landsteiner

Karl Landsteiner (; 14 June 1868 – 26 June 1943) was an Austrian-born American biologist, physician, and immunologist. He distinguished the main blood groups in 1900, having developed the modern system of classification of blood groups from ...

. Major outbreaks

In epidemiology, an outbreak is a sudden increase in occurrences of a disease when cases are in excess of normal expectancy for the location or season. It may affect a small and localized group or impact upon thousands of people across an entire ...

started to occur in the late 19th century in Europe and the United States, and in the 20th century, it became one of the most worrying childhood diseases. Following the introduction of polio vaccines in the 1950s polio incidence declined rapidly.

Once infected, there is no specific treatment. The disease can be prevented by the polio vaccine

Polio vaccines are vaccines used to prevent poliomyelitis (polio). Two types are used: an inactivated poliovirus given by injection (IPV) and a weakened poliovirus given by mouth (OPV). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends all chi ...

, with multiple doses required for lifelong protection. There are two broad types of polio vaccine; an injected vaccine using inactivated poliovirus and an oral vaccine containing attenuated (weakened) live virus. Through the use of both types of vaccine, incidence of wild polio has decreased from an estimated 350,000 cases in 1988 to 6 confirmed cases in 2021, confined to just three countries. There are rare incidents of disease transmission and/or of paralytic polio associated with the attenuated oral vaccine and for this reason the injected vaccine is preferred.

Signs and symptoms

The term "poliomyelitis" is used to identify the disease caused by any of the threeserotypes

A serotype or serovar is a distinct variation within a species of bacteria or virus or among immune cells of different individuals. These microorganisms, viruses, or cells are classified together based on their surface antigens, allowing the epi ...

of poliovirus. Two basic patterns of polio infection are described: a minor illness which does not involve the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all p ...

(CNS), sometimes called abortive poliomyelitis, and a major illness involving the CNS, which may be paralytic or nonparalytic. Adults are more likely to develop symptoms, including severe symptoms, than children.

In most people with a normal immune system, a poliovirus infection is asymptomatic. In about 25% of cases, the infection produces minor symptoms which may include sore throat

Sore throat, also known as throat pain, is pain or irritation of the throat. Usually, causes of sore throat include

* viral infections

* group A streptococcal infection (GAS) bacterial infection

* pharyngitis (inflammation of the throat)

* to ...

and low fever. These symptoms are temporary and full recovery occurs within one or two weeks.

In about 1 percent of infections the virus can migrate from the gastrointestinal tract into the central nervous system (CNS). Most patients with CNS involvement develop nonparalytic aseptic meningitis

Aseptic meningitis is the inflammation of the meninges, a membrane covering the brain and spinal cord, in patients whose cerebral spinal fluid test result is negative with routine bacterial cultures. Aseptic meningitis is caused by viruses, my ...

, with symptoms of headache, neck, back, abdominal and extremity pain, fever, vomiting, stomach pain, lethargy

Lethargy is a state of tiredness, sleepiness, weariness, fatigue, sluggishness or lack of energy. It can be accompanied by depression, decreased motivation, or apathy. Lethargy can be a normal response to inadequate sleep, overexertion, overwo ...

, and irritability. About one to five in 1000 cases progress to paralytic

Paralysis (also known as plegia) is a loss of motor function in one or more muscles. Paralysis can also be accompanied by a loss of feeling (sensory loss) in the affected area if there is sensory damage. In the United States, roughly 1 in 50 ...

disease, in which the muscles become weak, floppy and poorly controlled, and, finally, completely paralyzed; this condition is known as acute flaccid paralysis. The weakness most often involves the legs, but may less commonly involve the muscles of the head, neck, and diaphragm. Depending on the site of paralysis, paralytic poliomyelitis is classified as spinal, bulbar

The medulla oblongata or simply medulla is a long stem-like structure which makes up the lower part of the brainstem. It is anterior and partially inferior to the cerebellum. It is a cone-shaped neuronal mass responsible for autonomic (invol ...

, or bulbospinal. In those who develop paralysis, between 2 and 10 percent die as the paralysis affects the breathing muscles.

Encephalitis, an infection of the brain tissue itself, can occur in rare cases, and is usually restricted to infants. It is characterized by confusion, changes in mental status, headaches, fever, and, less commonly, seizure

An epileptic seizure, informally known as a seizure, is a period of symptoms due to abnormally excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. Outward effects vary from uncontrolled shaking movements involving much of the body with l ...

s and spastic paralysis

Spasticity () is a feature of altered skeletal muscle performance with a combination of paralysis, increased tendon reflex activity, and hypertonia. It is also colloquially referred to as an unusual "tightness", stiffness, or "pull" of muscles ...

.

Cause

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

''Enterovirus

''Enterovirus'' is a genus of positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses associated with several human and mammalian diseases. Enteroviruses are named by their transmission-route through the intestine ('enteric' meaning intestinal).

Serologic ...

'' known as poliovirus

A poliovirus, the causative agent of polio (also known as poliomyelitis), is a serotype of the species '' Enterovirus C'', in the family of ''Picornaviridae''. There are three poliovirus serotypes: types 1, 2, and 3.

Poliovirus is composed of a ...

(PV). This group of RNA viruses colonize the gastrointestinal tract – specifically the oropharynx

The pharynx (plural: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the oesophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its struc ...

and the intestine. The incubation time (form the first signs and symptoms) ranges from three to 35 days, with a more common span of six to 20 days. PV does not affect any species other than humans. Its structure is quite simple, composed of a single (+) sense RNA genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding g ...

enclosed in a protein shell called a capsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or ma ...

. In addition to protecting the virus' genetic material, the capsid proteins enable poliovirus to infect certain types of cells. Three serotypes

A serotype or serovar is a distinct variation within a species of bacteria or virus or among immune cells of different individuals. These microorganisms, viruses, or cells are classified together based on their surface antigens, allowing the epi ...

of poliovirus have been identified – wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1), type 2 (WPV2), and type 3 (WPV3) – each with a slightly different capsid protein. All three are extremely virulent

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its ability to ...

and produce the same disease symptoms. PV1 is the most commonly encountered form, and the one most closely associated with paralysis. WPV2 was certified as eradicated in 2015 and WPV3 certified as eradicated in 2019.

Individuals who are exposed to the virus, either through infection or by immunization

Immunization, or immunisation, is the process by which an individual's immune system becomes fortified against an infectious agent (known as the immunogen).

When this system is exposed to molecules that are foreign to the body, called ''non-se ...

via polio vaccine

Polio vaccines are vaccines used to prevent poliomyelitis (polio). Two types are used: an inactivated poliovirus given by injection (IPV) and a weakened poliovirus given by mouth (OPV). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends all chi ...

, develop immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity desc ...

. In immune individuals, IgA antibodies against poliovirus are present in the tonsil

The tonsils are a set of lymphoid organs facing into the aerodigestive tract, which is known as Waldeyer's tonsillar ring and consists of the adenoid tonsil, two tubal tonsils, two palatine tonsils, and the lingual tonsils. These organs play ...

s and gastrointestinal tract and able to block virus replication; IgG

Immunoglobulin G (Ig G) is a type of antibody. Representing approximately 75% of serum antibodies in humans, IgG is the most common type of antibody found in blood circulation. IgG molecules are created and released by plasma B cells. Each IgG ...

and IgM

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) is one of several isotypes of antibody (also known as immunoglobulin) that are produced by vertebrates. IgM is the largest antibody, and it is the first antibody to appear in the response to initial exposure to an antig ...

antibodies against PV can prevent the spread of the virus to motor neurons of the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all p ...

. Infection or vaccination with one serotype of poliovirus does not provide immunity against the other serotypes, and full immunity requires exposure to each serotype.

A rare condition with a similar presentation, nonpoliovirus poliomyelitis, may result from infections with enterovirus

''Enterovirus'' is a genus of positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses associated with several human and mammalian diseases. Enteroviruses are named by their transmission-route through the intestine ('enteric' meaning intestinal).

Serologic ...

es other than poliovirus.

The oral polio vaccine contains weakened viruses that can replicate. On rare occasions, these may be transmitted from the vaccinated person to other people, who may display symptoms of polio. In communities with good vaccine coverage transmission is limited, and the virus dies out. In communities with low vaccine coverage, this weakened virus may continue to circulate. Polio arising from this cause is referred to as ''circulating vaccine-derived polio'' (cVDPV) in order to distinguish it from the natural or "wild" poliovirus (WPV).

Transmission

Poliomyelitis is highly contagious via the fecal–oral (intestinal source) and the oral–oral (oropharyngeal source) routes. In endemic areas, wild polioviruses can infect virtually the entire human population. It is seasonal intemperate climate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout ...

s, with peak transmission occurring in summer and autumn. These seasonal differences are far less pronounced in tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

areas. The time between first exposure and first symptoms, known as the incubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infectious disease, the in ...

, is usually 6 to 20 days, with a maximum range of 3 to 35 days. Virus particles are excreted in the feces for several weeks following initial infection. The disease is transmitted primarily via the fecal–oral route, by ingesting contaminated food or water. It is occasionally transmitted via the oral–oral route, (Available free on Medscape; registration required.) a mode especially visible in areas with good sanitation and hygiene. Polio is most infectious between 7 and 10 days before and after the appearance of symptoms, but transmission is possible as long as the virus remains in the saliva or feces.

Factors that increase the risk of polio infection or affect the severity of the disease include immune deficiency

Immunodeficiency, also known as immunocompromisation, is a state in which the immune system's ability to fight infectious diseases and cancer is compromised or entirely absent. Most cases are acquired ("secondary") due to extrinsic factors that a ...

, malnutrition

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is "a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients" which adversely affects the body's tissues ...

, physical activity immediately following the onset of paralysis, skeletal muscle injury due to injection

Injection or injected may refer to:

Science and technology

* Injective function, a mathematical function mapping distinct arguments to distinct values

* Injection (medicine), insertion of liquid into the body with a syringe

* Injection, in broadca ...

of vaccines or therapeutic agents, and pregnancy

Pregnancy is the time during which one or more offspring develops (gestation, gestates) inside a woman, woman's uterus (womb). A multiple birth, multiple pregnancy involves more than one offspring, such as with twins.

Pregnancy usually occur ...

. Although the virus can cross the maternal-fetal barrier during pregnancy, the fetus does not appear to be affected by either maternal infection or polio vaccination. Maternal antibodies also cross the placenta

The placenta is a temporary embryonic and later fetal organ that begins developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrient, gas and waste exchange between the physically separate mate ...

, providing passive immunity Passive immunity is the transfer of active humoral immunity of ready-made antibodies. Passive immunity can occur naturally, when maternal antibodies are transferred to the fetus through the placenta, and it can also be induced artificially, when ...

that protects the infant from polio infection during the first few months of life.

Pathophysiology

Poliovirus enters the body through the mouth, infecting the first cells with which it comes in contact – the

Poliovirus enters the body through the mouth, infecting the first cells with which it comes in contact – the pharynx

The pharynx (plural: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the oesophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its st ...

and intestinal mucosa

The gastrointestinal wall of the gastrointestinal tract is made up of four layers of specialised tissue. From the inner cavity of the gut (the lumen) outwards, these are:

# Mucosa

# Submucosa

# Muscular layer

# Serosa or adventitia

The muco ...

. It gains entry by binding to an immunoglobulin-like receptor, known as the poliovirus receptor or CD155, on the cell membrane. The virus then hijacks the host cell's own machinery, and begins to replicate. Poliovirus divides within gastrointestinal cells for about a week, from where it spreads to the tonsils

The tonsils are a set of lymphoid organs facing into the aerodigestive tract, which is known as Waldeyer's tonsillar ring and consists of the adenoid tonsil, two tubal tonsils, two palatine tonsils, and the lingual tonsils. These organs play a ...

(specifically the follicular dendritic cell

Follicular dendritic cells (FDC) are cells of the immune system found in primary and secondary lymph follicles (lymph nodes) of the B cell areas of the lymphoid tissue. Unlike dendritic cells (DC), FDCs are not derived from the bone-marrow hema ...

s residing within the tonsilar germinal center

Germinal centers or germinal centres (GCs) are transiently formed structures within B cell zone (follicles) in secondary lymphoid organs – lymph nodes, ileal Peyer's patches, and the spleen – where mature B cells are activated, prolifera ...

s), the intestinal lymphoid tissue

The lymphatic system, or lymphoid system, is an organ system in vertebrates that is part of the immune system, and complementary to the circulatory system. It consists of a large network of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, lymphatic or lymphoid o ...

including the M cells of Peyer's patches

Peyer's patches (or aggregated lymphoid nodules) are organized lymphoid follicles, named after the 17th-century Swiss anatomist Johann Conrad Peyer.

* Reprinted as:

* Peyer referred to Peyer's patches as ''plexus'' or ''agmina glandularum'' (c ...

, and the deep cervical

In anatomy, cervical is an adjective that has two meanings:

# of or pertaining to any neck.

# of or pertaining to the female cervix: i.e., the ''neck'' of the uterus.

*Commonly used medical phrases involving the neck are

**cervical collar

**cerv ...

and mesenteric lymph nodes

The superior mesenteric lymph nodes may be divided into three principal groups:

* mesenteric lymph nodes

* ileocolic lymph nodes

* mesocolic lymph nodes

Structure

Mesenteric lymph nodes

The mesenteric lymph nodes or mesenteric glands are one of ...

, where it multiplies abundantly. The virus is subsequently absorbed into the bloodstream.

Known as viremia

Viremia is a medical condition where viruses enter the bloodstream and hence have access to the rest of the body. It is similar to ''bacteremia'', a condition where bacteria enter the bloodstream. The name comes from combining the word "virus" wit ...

, the presence of a virus in the bloodstream enables it to be widely distributed throughout the body. Poliovirus can survive and multiply within the blood and lymphatics for long periods of time, sometimes as long as 17 weeks. In a small percentage of cases, it can spread and replicate in other sites, such as brown fat

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) or brown fat makes up the adipose organ together with white adipose tissue (or white fat). Brown adipose tissue is found in almost all mammals.

Classification of brown fat refers to two distinct cell populations with si ...

, the reticuloendothelial tissues, and muscle. This sustained replication causes a major viremia, and leads to the development of minor influenza-like symptoms. Rarely, this may progress and the virus may invade the central nervous system, provoking a local inflammatory response

Inflammation (from la, inflammatio) is part of the complex biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants, and is a protective response involving immune cells, blood vessels, and molecu ...

. In most cases, this causes a self-limiting inflammation of the meninges, the layers of tissue surrounding the brain

A brain is an organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It is located in the head, usually close to the sensory organs for senses such as vision. It is the most complex organ in a ve ...

, which is known as nonparalytic aseptic meningitis. Penetration of the CNS provides no known benefit to the virus, and is quite possibly an incidental deviation of a normal gastrointestinal infection. The mechanisms by which poliovirus spreads to the CNS are poorly understood, but it appears to be primarily a chance event – largely independent of the age, gender, or socioeconomic

Socioeconomics (also known as social economics) is the social science that studies how economic activity affects and is shaped by social processes. In general it analyzes how modern societies progress, stagnate, or regress because of their l ...

position of the individual.

Paralytic polio

In around one percent of infections, poliovirus spreads along certain nerve fiber pathways, preferentially replicating in and destroying motor neurons within the

In around one percent of infections, poliovirus spreads along certain nerve fiber pathways, preferentially replicating in and destroying motor neurons within the spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue, which extends from the medulla oblongata in the brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone). The backbone encloses the central canal of the sp ...

, brain stem

The brainstem (or brain stem) is the posterior stalk-like part of the brain that connects the cerebrum with the spinal cord. In the human brain the brainstem is composed of the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. The midbrain is co ...

, or motor cortex

The motor cortex is the region of the cerebral cortex believed to be involved in the planning, control, and execution of voluntary movements.

The motor cortex is an area of the frontal lobe located in the posterior precentral gyrus immediately ...

. This leads to the development of paralytic poliomyelitis, the various forms of which (spinal, bulbar, and bulbospinal) vary only with the amount of neuronal damage and inflammation that occurs, and the region of the CNS affected.

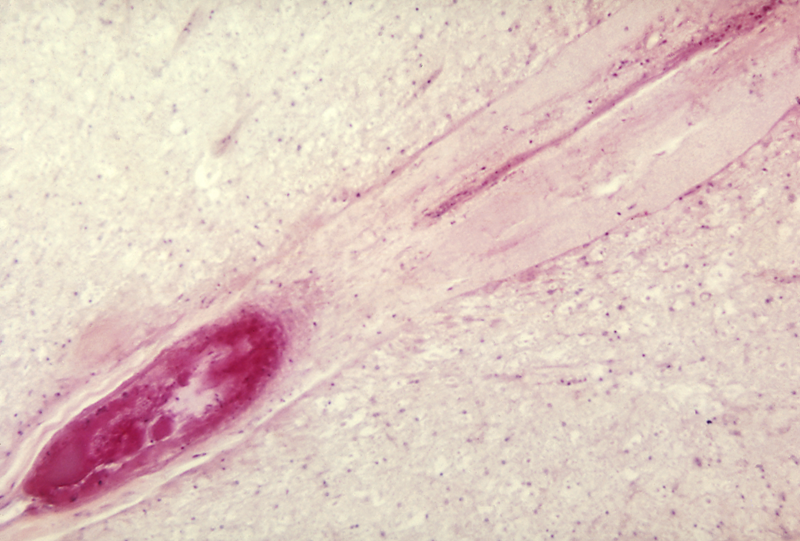

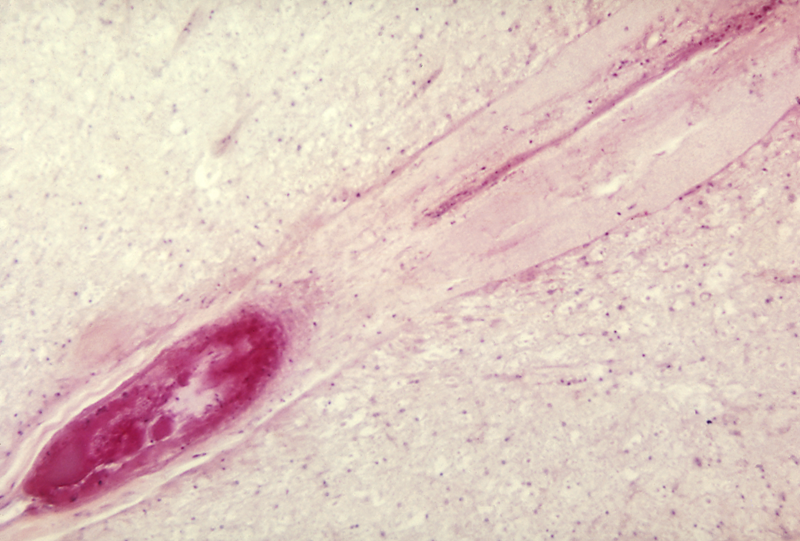

The destruction of neuronal cells produces lesion

A lesion is any damage or abnormal change in the tissue of an organism, usually caused by disease or trauma. ''Lesion'' is derived from the Latin "injury". Lesions may occur in plants as well as animals.

Types

There is no designated classif ...

s within the spinal ganglia

A dorsal root ganglion (or spinal ganglion; also known as a posterior root ganglion) is a cluster of neurons (a ganglion) in a dorsal root of a spinal nerve. The cell bodies of sensory neurons known as first-order neurons are located in the dorsal ...

; these may also occur in the reticular formation, vestibular nuclei

The vestibular nuclei (VN) are the cranial nuclei for the vestibular nerve located in the brainstem.

In Terminologia Anatomica they are grouped in both the pons and the medulla in the brainstem.

Structure Path

The fibers of the vestibular n ...

, cerebellar vermis

The cerebellar vermis (from Latin ''vermis,'' "worm") is located in the medial, cortico-nuclear zone of the cerebellum, which is in the posterior fossa of the cranium. The primary fissure in the vermis curves ventrolaterally to the superior su ...

, and deep cerebellar nuclei

The cerebellum (Latin for "little brain") is a major feature of the hindbrain of all vertebrates. Although usually smaller than the cerebrum, in some animals such as the mormyrid fishes it may be as large as or even larger. In humans, the cereb ...

. Inflammation associated with nerve cell

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoa. No ...

destruction often alters the color and appearance of the gray matter in the spinal column, causing it to appear reddish and swollen. Other destructive changes associated with paralytic disease occur in the forebrain

In the anatomy of the brain of vertebrates, the forebrain or prosencephalon is the rostral (forward-most) portion of the brain. The forebrain (prosencephalon), the midbrain (mesencephalon), and hindbrain (rhombencephalon) are the three primary ...

region, specifically the hypothalamus

The hypothalamus () is a part of the brain that contains a number of small nuclei with a variety of functions. One of the most important functions is to link the nervous system to the endocrine system via the pituitary gland. The hypothalamu ...

and thalamus

The thalamus (from Greek θάλαμος, "chamber") is a large mass of gray matter located in the dorsal part of the diencephalon (a division of the forebrain). Nerve fibers project out of the thalamus to the cerebral cortex in all directions, ...

. The molecular mechanisms by which poliovirus causes paralytic disease are poorly understood.

Early symptoms of paralytic polio include high fever, headache, stiffness in the back and neck, asymmetrical weakness of various muscles, sensitivity to touch, difficulty swallowing

Dysphagia is difficulty in swallowing. Although classified under "symptoms and signs" in ICD-10, in some contexts it is classified as a condition in its own right.

It may be a sensation that suggests difficulty in the passage of solids or liqui ...

, muscle pain

Myalgia (also called muscle pain and muscle ache in layman's terms) is the medical term for muscle pain. Myalgia is a symptom of many diseases. The most common cause of acute myalgia is the overuse of a muscle or group of muscles; another like ...

, loss of superficial and deep reflexes, paresthesia (pins and needles), irritability, constipation, or difficulty urinating. Paralysis generally develops one to ten days after early symptoms begin, progresses for two to three days, and is usually complete by the time the fever breaks.

The likelihood of developing paralytic polio increases with age, as does the extent of paralysis. In children, nonparalytic meningitis is the most likely consequence of CNS involvement, and paralysis occurs in only one in 1000 cases. In adults, paralysis occurs in one in 75 cases. Reproduced online with permission by Lincolnshire Post-Polio Library; retrieved on 10 November 2007. In children under five years of age, paralysis of one leg is most common; in adults, extensive paralysis of the chest

The thorax or chest is a part of the anatomy of humans, mammals, and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen. In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main divisions of the crea ...

and abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the belly, tummy, midriff, tucky or stomach) is the part of the body between the thorax (chest) and pelvis, in humans and in other vertebrates. The abdomen is the front part of the abdominal segment of the to ...

also affecting all four limbs – quadriplegia – is more likely. Paralysis rates also vary depending on the serotype of the infecting poliovirus; the highest rates of paralysis (one in 200) are associated with poliovirus type 1, the lowest rates (one in 2,000) are associated with type 2.

Spinal polio

ventral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

(front) grey matter

Grey matter is a major component of the central nervous system, consisting of neuronal cell bodies, neuropil (dendrites and unmyelinated axons), glial cells (astrocytes and oligodendrocytes), synapses, and capillaries. Grey matter is distingu ...

section in the spinal column, which are responsible for movement of the muscles, including those of the trunk, limbs, and the intercostal muscle

Intercostal muscles are many different groups of muscles that run between the ribs, and help form and move the chest wall. The intercostal muscles are mainly involved in the mechanical aspect of breathing by helping expand and shrink the size of ...

s. Virus invasion causes inflammation of the nerve cells, leading to damage or destruction of motor neuron ganglia. When spinal neurons die, Wallerian degeneration

Wallerian degeneration is an active process of degeneration that results when a nerve fiber is cut or crushed and the part of the axon distal to the injury (i.e. farther from the neuron's cell body) degenerates. A related process of dying back o ...

takes place, leading to weakness of those muscles formerly innervated by the now-dead neurons. With the destruction of nerve cells, the muscles no longer receive signals from the brain or spinal cord; without nerve stimulation, the muscles atrophy, becoming weak, floppy and poorly controlled, and finally completely paralyzed. Maximum paralysis progresses rapidly (two to four days), and usually involves fever and muscle pain. Deep tendon reflex

Tendon reflex (or T-reflex) may refer to:

*The stretch reflex or muscle stretch reflex (MSR), when the stretch is created by a blow upon a muscle tendon. This is the commonly used definition of the term. Albeit a misnomer, in this sense a common ...

sensation

Sensation (psychology) refers to the processing of the senses by the sensory system.

Sensation or sensations may also refer to:

In arts and entertainment In literature

* Sensation (fiction), a fiction writing mode

* Sensation novel, a Britis ...

(the ability to feel) in the paralyzed limbs, however, is not affected.

The extent of spinal paralysis depends on the region of the cord affected, which may be cervical

In anatomy, cervical is an adjective that has two meanings:

# of or pertaining to any neck.

# of or pertaining to the female cervix: i.e., the ''neck'' of the uterus.

*Commonly used medical phrases involving the neck are

**cervical collar

**cerv ...

, thoracic

The thorax or chest is a part of the anatomy of humans, mammals, and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen. In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main divisions of the crea ...

, or lumbar. The virus may affect muscles on both sides of the body, but more often the paralysis is asymmetrical

Asymmetry is the absence of, or a violation of, symmetry (the property of an object being invariant to a transformation, such as reflection). Symmetry is an important property of both physical and abstract systems and it may be displayed in pre ...

. Any limb

Limb may refer to:

Science and technology

*Limb (anatomy), an appendage of a human or animal

*Limb, a large or main branch of a tree

*Limb, in astronomy, the curved edge of the apparent disk of a celestial body, e.g. lunar limb

*Limb, in botany, ...

or combination of limbs may be affected – one leg, one arm, or both legs and both arms. Paralysis is often more severe proximally (where the limb joins the body) than distally

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

(the fingertip

A finger is a limb of the body and a type of digit, an organ of manipulation and sensation found in the hands of most of the Tetrapods, so also with humans and other primates. Most land vertebrates have five fingers ( Pentadactyly). Chambers ...

s and toe

Toes are the digits (fingers) of the foot of a tetrapod. Animal species such as cats that walk on their toes are described as being ''digitigrade''. Humans, and other animals that walk on the soles of their feet, are described as being ''plan ...

s).

Bulbar polio

bulbar

The medulla oblongata or simply medulla is a long stem-like structure which makes up the lower part of the brainstem. It is anterior and partially inferior to the cerebellum. It is a cone-shaped neuronal mass responsible for autonomic (invol ...

region of the brain stem

The brainstem (or brain stem) is the posterior stalk-like part of the brain that connects the cerebrum with the spinal cord. In the human brain the brainstem is composed of the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. The midbrain is co ...

. The bulbar region is a white matter

White matter refers to areas of the central nervous system (CNS) that are mainly made up of myelinated axons, also called tracts. Long thought to be passive tissue, white matter affects learning and brain functions, modulating the distributi ...

pathway that connects the cerebral cortex

The cerebral cortex, also known as the cerebral mantle, is the outer layer of neural tissue of the cerebrum of the brain in humans and other mammals. The cerebral cortex mostly consists of the six-layered neocortex, with just 10% consistin ...

to the brain stem. The destruction of these nerves weakens the muscles supplied by the cranial nerves, producing symptoms of encephalitis, and causes difficulty breathing, speaking and swallowing. Critical nerves affected are the glossopharyngeal nerve

The glossopharyngeal nerve (), also known as the ninth cranial nerve, cranial nerve IX, or simply CN IX, is a cranial nerve that exits the brainstem from the sides of the upper medulla, just anterior (closer to the nose) to the vagus nerve. ...

(which partially controls swallowing and functions in the throat, tongue movement, and taste), the vagus nerve

The vagus nerve, also known as the tenth cranial nerve, cranial nerve X, or simply CN X, is a cranial nerve that interfaces with the parasympathetic control of the heart, lungs, and digestive tract. It comprises two nerves—the left and righ ...

(which sends signals to the heart, intestines, and lungs), and the accessory nerve

The accessory nerve, also known as the eleventh cranial nerve, cranial nerve XI, or simply CN XI, is a cranial nerve that supplies the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. It is classified as the eleventh of twelve pairs of cranial nerv ...

(which controls upper neck movement). Due to the effect on swallowing, secretions of mucus

Mucus ( ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It ...

may build up in the airway, causing suffocation. Other signs and symptoms include facial weakness

Facial weakness is a medical sign associated with a variety of medical conditions.

Some specific conditions associated with facial weakness include:

* Stroke

* Neurofibromatosis

* Bell's palsy

* Ramsay Hunt syndrome

* Spontaneous cerebrospinal ...

(caused by destruction of the trigeminal nerve

In neuroanatomy, the trigeminal nerve ( lit. ''triplet'' nerve), also known as the fifth cranial nerve, cranial nerve V, or simply CN V, is a cranial nerve responsible for sensation in the face and motor functions such as biting and chew ...

and facial nerve

The facial nerve, also known as the seventh cranial nerve, cranial nerve VII, or simply CN VII, is a cranial nerve that emerges from the pons of the brainstem, controls the muscles of facial expression, and functions in the conveyance of taste ...

, which innervate the cheeks, tear duct

The nasolacrimal duct (also called the tear duct) carries tears from the lacrimal sac of the eye into the nasal cavity. The duct begins in the eye socket between the maxillary and lacrimal bones, from where it passes downwards and backwards. The ...

s, gums, and muscles of the face, among other structures), double vision

Diplopia is the simultaneous perception of two images of a single object that may be displaced horizontally or vertically in relation to each other. Also called double vision, it is a loss of visual focus under regular conditions, and is often v ...

, difficulty in chewing, and abnormal respiratory rate

The respiratory rate is the rate at which breathing occurs; it is set and controlled by the respiratory center of the brain. A person's respiratory rate is usually measured in breaths per minute.

Measurement

The respiratory rate in humans is me ...

, depth, and rhythm (which may lead to respiratory arrest). Pulmonary edema

Pulmonary edema, also known as pulmonary congestion, is excessive liquid accumulation in the tissue and air spaces (usually alveoli) of the lungs. It leads to impaired gas exchange and may cause hypoxemia and respiratory failure. It is due t ...

and shock

Shock may refer to:

Common uses Collective noun

*Shock, a historic commercial term for a group of 60, see English numerals#Special names

* Stook, or shock of grain, stacked sheaves

Healthcare

* Shock (circulatory), circulatory medical emergen ...

are also possible and may be fatal.

Bulbospinal polio

Approximately 19 percent of all paralytic polio cases have both bulbar and spinal symptoms; this subtype is called respiratory or bulbospinal polio. Here, the virus affects the upper part of the cervical spinal cord ( cervical vertebrae C3 through C5), and paralysis of the diaphragm occurs. The critical nerves affected are the phrenic nerve (which drives the diaphragm to inflate thelungs

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side ...

) and those that drive the muscles needed for swallowing. By destroying these nerves, this form of polio affects breathing, making it difficult or impossible for the patient to breathe without the support of a ventilator

A ventilator is a piece of medical technology that provides mechanical ventilation by moving breathable air into and out of the lungs, to deliver breaths to a patient who is physically unable to breathe, or breathing insufficiently. Ventilators ...

. It can lead to paralysis of the arms and legs and may also affect swallowing and heart functions.

Diagnosis

Paralytic poliomyelitis may be clinically suspected in individuals experiencing acute onset of flaccid paralysis in one or more limbs with decreased or absent tendon reflexes in the affected limbs that cannot be attributed to another apparent cause, and without sensory or cognitive loss. A laboratory diagnosis is usually made based on the recovery of poliovirus from a stool sample or a swab of thepharynx

The pharynx (plural: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the oesophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its st ...

. Antibodies to poliovirus can be diagnostic, and are generally detected in the blood of infected patients early in the course of infection. Analysis of the patient's cerebrospinal fluid

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, colorless body fluid found within the tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord of all vertebrates.

CSF is produced by specialised ependymal cells in the choroid plexus of the ventricles of the ...

(CSF), which is collected by a lumbar puncture ("spinal tap"), reveals an increased number of white blood cells (primarily lymphocyte

A lymphocyte is a type of white blood cell (leukocyte) in the immune system of most vertebrates. Lymphocytes include natural killer cells (which function in cell-mediated, cytotoxic innate immunity), T cells (for cell-mediated, cytotoxic ad ...

s) and a mildly elevated protein level. Detection of virus in the CSF is diagnostic of paralytic polio but rarely occurs.

If poliovirus is isolated from a patient experiencing acute flaccid paralysis, it is further tested through oligonucleotide

Oligonucleotides are short DNA or RNA molecules, oligomers, that have a wide range of applications in genetic testing, research, and forensics. Commonly made in the laboratory by solid-phase chemical synthesis, these small bits of nucleic acids ...

mapping (genetic fingerprint

DNA profiling (also called DNA fingerprinting) is the process of determining an individual's DNA characteristics. DNA analysis intended to identify a species, rather than an individual, is called DNA barcoding.

DNA profiling is a forensic tec ...

ing), or more recently by PCR amplification, to determine whether it is "wild type

The wild type (WT) is the phenotype of the typical form of a species as it occurs in nature. Originally, the wild type was conceptualized as a product of the standard "normal" allele at a locus, in contrast to that produced by a non-standard, "m ...

" (that is, the virus encountered in nature) or "vaccine type" (derived from a strain of poliovirus used to produce polio vaccine). It is important to determine the source of the virus because for each reported case of paralytic polio caused by wild poliovirus, an estimated 200 to 3,000 other contagious asymptomatic carriers exist.

Prevention

Passive immunization

In 1950, William Hammon at theUniversity of Pittsburgh

The University of Pittsburgh (Pitt) is a public state-related research university in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The university is composed of 17 undergraduate and graduate schools and colleges at its urban Pittsburgh campus, home to the univers ...

purified the gamma globulin component of the blood plasma

Blood plasma is a light amber-colored liquid component of blood in which blood cells are absent, but contains proteins and other constituents of whole blood in suspension. It makes up about 55% of the body's total blood volume. It is the intr ...

of polio survivors. Hammon proposed the gamma globulin, which contained antibodies to poliovirus, could be used to halt poliovirus infection, prevent disease, and reduce the severity of disease in other patients who had contracted polio. The results of a large clinical trial

Clinical trials are prospective biomedical or behavioral research studies on human participants designed to answer specific questions about biomedical or behavioral interventions, including new treatments (such as novel vaccines, drugs, diet ...

were promising; the gamma globulin was shown to be about 80 percent effective in preventing the development of paralytic poliomyelitis. It was also shown to reduce the severity of the disease in patients who developed polio. Due to the limited supply of blood plasma gamma globulin was later deemed impractical for widespread use and the medical community focused on the development of a polio vaccine.

Vaccine

Two types of vaccine are used throughout the world to combat polio. Both types induce immunity to polio and are effective in protecting individuals from disease.

The first candidate

Two types of vaccine are used throughout the world to combat polio. Both types induce immunity to polio and are effective in protecting individuals from disease.

The first candidate polio vaccine

Polio vaccines are vaccines used to prevent poliomyelitis (polio). Two types are used: an inactivated poliovirus given by injection (IPV) and a weakened poliovirus given by mouth (OPV). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends all chi ...

, based on one serotype of a live but attenuated (weakened) virus, was developed by the virologist

Virology is the scientific study of biological viruses. It is a subfield of microbiology that focuses on their detection, structure, classification and evolution, their methods of infection and exploitation of host cells for reproduction, thei ...

Hilary Koprowski

Hilary Koprowski (5 December 191611 April 2013) was a Polish virologist and immunologist active in the United States who demonstrated the world's first effective live polio vaccine. He authored or co-authored over 875 scientific papers and co ...

. Koprowski's prototype vaccine was given to an eight-year-old boy on 27 February 1950. Koprowski continued to work on the vaccine throughout the 1950s, leading to large-scale trials in the then Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

and the vaccination of seven million children in Poland against serotypes PV1 and PV3 between 1958 and 1960. Accessed 16 December 2009.

The second polio virus vaccine was developed in 1952 by Jonas Salk

Jonas Edward Salk (; born Jonas Salk; October 28, 1914June 23, 1995) was an American virologist and medical researcher who developed one of the first successful polio vaccines. He was born in New York City and attended the City College of New ...

at the University of Pittsburgh, and announced to the world on 12 April 1955. The Salk vaccine, or inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV), is based on poliovirus grown in a type of monkey kidney tissue culture

Tissue culture is the growth of tissues or cells in an artificial medium separate from the parent organism. This technique is also called micropropagation. This is typically facilitated via use of a liquid, semi-solid, or solid growth medium, su ...

(vero cell

Vero cells are a lineage of cells used in cell cultures. The 'Vero' lineage was isolated from kidney epithelial cells extracted from an African green monkey (''Chlorocebus'' sp.; formerly called ''Cercopithecus aethiops'', this group of monkeys ha ...

line), which is chemically inactivated with formalin

Formaldehyde ( , ) ( systematic name methanal) is a naturally occurring organic compound with the formula and structure . The pure compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde (refer to section F ...

. After two doses of inactivated poliovirus vaccine (given by injection

Injection or injected may refer to:

Science and technology

* Injective function, a mathematical function mapping distinct arguments to distinct values

* Injection (medicine), insertion of liquid into the body with a syringe

* Injection, in broadca ...

), 90 percent or more of individuals develop protective antibody to all three serotypes of poliovirus, and at least 99 percent are immune to poliovirus following three doses.

Subsequently, Albert Sabin

Albert Bruce Sabin ( ; August 26, 1906 – March 3, 1993) was a Polish-American medical researcher, best known for developing the oral polio vaccine, which has played a key role in nearly eradicating the disease. In 1969–72, he served as th ...

developed another live, oral polio vaccine (OPV). It was produced by the repeated passage of the virus through nonhuman cells at sub physiological temperatures. The attenuated poliovirus in the Sabin vaccine replicates very efficiently in the gut, the primary site of wild poliovirus infection and replication, but the vaccine strain is unable to replicate efficiently within nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes ...

tissue. A single dose of Sabin's oral polio vaccine produces immunity to all three poliovirus serotypes in about 50 percent of recipients. Three doses of live-attenuated oral vaccine produce protective antibody to all three poliovirus types in more than 95 percent of recipients. Human trials of Sabin's vaccine began in 1957, and in 1958 it was selected, in competition with the live vaccines of Koprowski and other researchers, by the US National Institutes of Health. Licensed in 1962, it rapidly became the only polio vaccine used worldwide.

OPV efficiently blocks person-to-person transmission of wild poliovirus by oral-oral and fecal-oral routes, thereby protecting both individual vaccine recipients and the wider community (herd immunity

Herd immunity (also called herd effect, community immunity, population immunity, or mass immunity) is a form of indirect protection that applies only to contagious diseases. It occurs when a sufficient percentage of a population has become im ...

). IPV confers good immunity but is less effective at preventing spread of wild poliovirus by the fecal-oral route.

Because the oral polio vaccine is inexpensive, easy to administer, and produces excellent immunity in the intestine (which helps prevent infection with wild virus in areas where it is

Because the oral polio vaccine is inexpensive, easy to administer, and produces excellent immunity in the intestine (which helps prevent infection with wild virus in areas where it is endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

), it has been the vaccine of choice for controlling poliomyelitis in many countries. On very rare occasions (about one case per 750,000 vaccine recipients), the attenuated virus in the oral polio vaccine reverts into a form that can paralyze. In 2017, cases caused by vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) outnumbered wild poliovirus cases for the first time, due to wild polio cases hitting record lows. Most industrialized countries have switched to inactivated polio vaccine, which cannot revert, either as the sole vaccine against poliomyelitis or in combination with oral polio vaccine.

Treatment

There is no cure for polio, but there are treatments. The focus of modern treatment has been on providing relief of symptoms, speeding recovery and preventing complications. Supportive measures includeantibiotics

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention o ...

to prevent infections in weakened muscles, analgesics

An analgesic drug, also called simply an analgesic (American English), analgaesic (British English), pain reliever, or painkiller, is any member of the group of drugs used to achieve relief from pain (that is, analgesia or pain management). It ...

for pain, moderate exercise and a nutritious diet. Treatment of polio often requires long-term rehabilitation, including occupational therapy, physical therapy, braces, corrective shoes and, in some cases, orthopedic surgery

Orthopedic surgery or orthopedics ( alternatively spelt orthopaedics), is the branch of surgery concerned with conditions involving the musculoskeletal system. Orthopedic surgeons use both surgical and nonsurgical means to treat musculoskeletal ...

.

Portable ventilator

A ventilator is a piece of medical technology that provides mechanical ventilation by moving breathable air into and out of the lungs, to deliver breaths to a patient who is physically unable to breathe, or breathing insufficiently. Ventilators ...

s may be required to support breathing. Historically, a noninvasive, negative-pressure ventilator, more commonly called an iron lung

An iron lung is a type of negative pressure ventilator (NPV), a mechanical respirator which encloses most of a person's body, and varies the air pressure in the enclosed space, to stimulate breathing.Shneerson, Dr. John M., Newmarket Genera ...

, was used to artificially maintain respiration during an acute polio infection until a person could breathe independently (generally about one to two weeks). Today, many polio survivors with permanent respiratory paralysis use modern jacket-type negative-pressure ventilators worn over the chest and abdomen.

Other historical treatments for polio include hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy, formerly called hydropathy and also called water cure, is a branch of alternative medicine (particularly naturopathy), occupational therapy, and physiotherapy, that involves the use of water for pain relief and treatment. The term ...

, electrotherapy

Electrotherapy is the use of electrical energy as a medical treatment. In medicine, the term ''electrotherapy'' can apply to a variety of treatments, including the use of electrical devices such as deep brain stimulators for neurological dise ...

, massage and passive motion exercises, and surgical treatments, such as tendon lengthening and nerve grafting.

Sister Elizabeth Kenny

Sister Elizabeth Kenny (20 September 1880 – 30 November 1952) was a self-trained Australian bush nurse who developed an approach to treating polio that was controversial at the time. Her method, promoted internationally while working in Austra ...

's Kenny regimen is now the hallmark for the treatment of paralytic polio.

Prognosis

Patients with abortive polio infections recover completely. In those who develop only aseptic meningitis, the symptoms can be expected to persist for two to ten days, followed by complete recovery. In cases of spinal polio, if the affected nerve cells are completely destroyed, paralysis will be permanent; cells that are not destroyed, but lose function temporarily, may recover within four to six weeks after onset. Reproduced online with permission by Post-Polio Health International; retrieved on 10 November 2007. Half the patients with spinal polio recover fully; one-quarter recover with mild disability, and the remaining quarter are left with severe disability. The degree of both acute paralysis and residual paralysis is likely to be proportional to the degree of

Patients with abortive polio infections recover completely. In those who develop only aseptic meningitis, the symptoms can be expected to persist for two to ten days, followed by complete recovery. In cases of spinal polio, if the affected nerve cells are completely destroyed, paralysis will be permanent; cells that are not destroyed, but lose function temporarily, may recover within four to six weeks after onset. Reproduced online with permission by Post-Polio Health International; retrieved on 10 November 2007. Half the patients with spinal polio recover fully; one-quarter recover with mild disability, and the remaining quarter are left with severe disability. The degree of both acute paralysis and residual paralysis is likely to be proportional to the degree of viremia

Viremia is a medical condition where viruses enter the bloodstream and hence have access to the rest of the body. It is similar to ''bacteremia'', a condition where bacteria enter the bloodstream. The name comes from combining the word "virus" wit ...

, and inversely proportional

In mathematics, two sequences of numbers, often experimental data, are proportional or directly proportional if their corresponding elements have a constant ratio, which is called the coefficient of proportionality or proportionality constan ...

to the degree of immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity desc ...

. Spinal polio is rarely fatal.

Without respiratory support, consequences of poliomyelitis with respiratory

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies gre ...

involvement include suffocation or pneumonia from aspiration of secretions. Overall, 5 to 10 percent of patients with paralytic polio die due to the paralysis of muscles used for breathing. The case fatality rate

In epidemiology, case fatality rate (CFR) – or sometimes more accurately case-fatality risk – is the proportion of people diagnosed with a certain disease, who end up dying of it. Unlike a disease's mortality rate, the CFR does not take int ...

(CFR) varies by age: 2 to 5 percent of children and up to 15 to 30 percent of adults die. Bulbar polio often causes death if respiratory support is not provided; with support, its CFR ranges from 25 to 75 percent, depending on the age of the patient. When intermittent positive pressure ventilation is available, the fatalities can be reduced to 15 percent.

Recovery

Many cases of poliomyelitis result in only temporary paralysis. Generally in these cases, nerve impulses return to the paralyzed muscle within a month, and recovery is complete in six to eight months. Theneurophysiological

Neurophysiology is a branch of physiology and neuroscience that studies nervous system function rather than nervous system architecture. This area aids in the diagnosis and monitoring of neurological diseases. Historically, it has been dominated b ...

processes involved in recovery following acute paralytic poliomyelitis are quite effective; muscles are able to retain normal strength even if half the original motor neurons have been lost. Paralysis remaining after one year is likely to be permanent, although some recovery of muscle strength is possible up to 18 months after infection.

One mechanism involved in recovery is nerve terminal sprouting, in which remaining brainstem and spinal cord motor neurons develop new branches, or axonal sprouts. These sprouts can reinnervate orphaned muscle fibers that have been denervated by acute polio infection, restoring the fibers' capacity to contract and improving strength. Terminal sprouting may generate a few significantly enlarged motor neurons doing work previously performed by as many as four or five units: a single motor neuron that once controlled 200 muscle cells might control 800 to 1000 cells. Other mechanisms that occur during the rehabilitation phase, and contribute to muscle strength restoration, include myofiber hypertrophy – enlargement of muscle fibers through exercise and activity – and transformation of type II muscle fibers to type I muscle fibers.

In addition to these physiological processes, the body can compensate for residual paralysis in other ways. Weaker muscles can be used at a higher than usual intensity relative to the muscle's maximal capacity, little-used muscles can be developed, and ligaments can enable stability and mobility.

Complications

Residual complications of paralytic polio often occur following the initial recovery process. Muscleparesis

In medicine, paresis () is a condition typified by a weakness of voluntary movement, or by partial loss of voluntary movement or by impaired movement. When used without qualifiers, it usually refers to the limbs, but it can also be used to desc ...

and paralysis can sometimes result in skeletal deformities, tightening of the joints, and movement disability. Once the muscles in the limb become flaccid, they may interfere with the function of other muscles. A typical manifestation of this problem is equinus foot (similar to club foot

Clubfoot is a birth defect where one or both feet are rotated inward and downward. Congenital clubfoot is the most common congenital malformation of the foot with an incidence of 1 per 1000 births. In approximately 50% of cases, clubfoot aff ...

). This deformity develops when the muscles that pull the toes downward are working, but those that pull it upward are not, and the foot naturally tends to drop toward the ground. If the problem is left untreated, the Achilles tendon

The Achilles tendon or heel cord, also known as the calcaneal tendon, is a tendon at the back of the lower leg, and is the thickest in the human body. It serves to attach the plantaris, gastrocnemius (calf) and soleus muscles to the calcaneus ( ...

s at the back of the foot retract and the foot cannot take on a normal position. People with polio that develop equinus foot cannot walk properly because they cannot put their heels on the ground. A similar situation can develop if the arms become paralyzed.

In some cases the growth of an affected leg is slowed by polio, while the other leg continues to grow normally. The result is that one leg is shorter than the other and the person limps and leans to one side, in turn leading to deformities of the spine (such as scoliosis). Osteoporosis and increased likelihood of bone fractures may occur. An intervention to prevent or lessen length disparity can be to perform an epiphysiodesis

Epiphysiodesis is a pediatric orthopedic surgery procedure that aims at altering or stopping the bone growth naturally occurring through the growth plate also known as the physeal plate. There are two types of epiphysiodesis: temporary hemiepiphy ...

on the distal femoral and proximal tibial/fibular condyles, so that limb's growth is artificially stunted, and by the time of epiphyseal (growth) plate closure, the legs are more equal in length. Alternatively, a person can be fitted with custom-made footwear which corrects the difference in leg lengths. Other surgery to re-balance muscular agonist/antagonist imbalances may also be helpful. Extended use of braces or wheelchairs may cause compression neuropathy, as well as a loss of proper function of the vein

Veins are blood vessels in humans and most other animals that carry blood towards the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart; exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenat ...

s in the legs, due to pooling of blood in paralyzed lower limbs. Complications from prolonged immobility involving the lungs

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side ...

, kidney

The kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped organs found in vertebrates. They are located on the left and right in the retroperitoneal space, and in adult humans are about in length. They receive blood from the paired renal arteries; blo ...

s and heart

The heart is a muscular organ in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon dioxide to t ...

include pulmonary edema

Pulmonary edema, also known as pulmonary congestion, is excessive liquid accumulation in the tissue and air spaces (usually alveoli) of the lungs. It leads to impaired gas exchange and may cause hypoxemia and respiratory failure. It is due t ...

, aspiration pneumonia

Aspiration pneumonia is a type of lung infection that is due to a relatively large amount of material from the stomach or mouth entering the lungs. Signs and symptoms often include fever and cough of relatively rapid onset. Complications may inc ...

, urinary tract infection

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is an infection that affects part of the urinary tract. When it affects the lower urinary tract it is known as a bladder infection (cystitis) and when it affects the upper urinary tract it is known as a kidne ...

s, kidney stone

Kidney stone disease, also known as nephrolithiasis or urolithiasis, is a crystallopathy where a solid piece of material (kidney stone) develops in the urinary tract. Kidney stones typically form in the kidney and leave the body in the urine s ...

s, paralytic ileus

Ileus is a disruption of the normal propulsive ability of the intestine. It can be caused by lack of peristalsis or by mechanical obstruction.

The word 'ileus' is from Ancient Greek ''eileós'' (, "intestinal obstruction"). The term 'subileus' r ...

, myocarditis and cor pulmonale

Pulmonary heart disease, also known as cor pulmonale, is the enlargement and failure of the right ventricle of the heart as a response to increased vascular resistance (such as from pulmonic stenosis) or high blood pressure in the lungs.

Chroni ...

.

Post-polio syndrome

Between 25 percent and 50 percent of individuals who have recovered from paralytic polio in childhood can develop additional symptoms decades after recovering from the acute infection, notably new muscle weakness and extreme fatigue. This condition is known aspost-polio syndrome

Post-polio syndrome (PPS, poliomyelitis sequelae) is a group of latent symptoms of poliomyelitis (polio), occurring at about a 25–40% rate (latest data greater than 80%). These symptoms are caused by the damaging effects of the viral infection ...

(PPS) or post-polio sequelae. The symptoms of PPS are thought to involve a failure of the oversized motor units created during the recovery phase of the paralytic disease. Contributing factors that increase the risk of PPS include aging with loss of neuron units, the presence of a permanent residual impairment after recovery from the acute illness, and both overuse and disuse of neurons. PPS is a slow, progressive disease, and there is no specific treatment for it. Post-polio syndrome is not an infectious process, and persons experiencing the syndrome do not shed poliovirus.

Orthotics

Paralysis, length differences and deformations of the lower extremities can lead to a hindrance when walking with compensation mechanisms that lead to a severe impairment of the gait pattern. In order to be able to stand and walk safely and to improve the gait pattern,

Paralysis, length differences and deformations of the lower extremities can lead to a hindrance when walking with compensation mechanisms that lead to a severe impairment of the gait pattern. In order to be able to stand and walk safely and to improve the gait pattern, orthotics

Orthotics ( el, Ορθός, translit=ortho, lit=to straighten, to align) is a medical specialty that focuses on the design and application of orthoses, or braces. An is "an externally applied device used to influence the structural and functio ...

can be included in the therapy concept. Today, modern materials and functional elements enable the orthosis to be specifically adapted to the requirements resulting from the patient's gait. Mechanical stance phase control knee joints may secure the knee joint in the early stance phases and release again for knee flexion when the swing phase is initiated. With the help of an orthotic treatment with a stance phase control knee joint, a natural gait pattern can be achieved despite mechanical protection against unwanted knee flexion. In these cases, locked knee joints are often used, which have a good safety function, but do not allow knee flexion when walking during swing phase. With such joints, the knee joint remains mechanically blocked during the swing phase. Patients with locked knee joints must swing the leg forward with the knee extended even during the swing phase. This only works if the patient develops compensatory mechanisms, e.g. by raising the body's center of gravity in the swing phase (Duchenne limping) or by swinging the orthotic leg to the side (circumduction).

Epidemiology

Eradication

Following the widespread use of poliovirus vaccine in the mid-1950s, new cases of poliomyelitis declined dramatically in many industrialized countries. A global effort toeradicate

The word "Eradication" is derived from Latin word "radix" which means "root". It may refer to:

*Eradication of infectious diseases (human), the reduction of the global incidence of an infectious disease in humans to zero

*Eradication of infectiou ...

polio - the Global Polio Eradication Initiative - began in 1988, led by the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of ...

, UNICEF

UNICEF (), originally called the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund in full, now officially United Nations Children's Fund, is an agency of the United Nations responsible for providing humanitarian and developmental aid to ...

, and The Rotary Foundation

The Rotary Foundation is a non-profit corporation that supports the efforts of Rotary International to achieve world understanding and peace through international humanitarian, educational, and cultural exchange programs. It is supported solely b ...

. Polio is one of only two diseases currently the subject of a global eradication program, the other being Guinea worm disease

Dracunculiasis, also called Guinea-worm disease, is a parasitic infection by the Guinea worm, ''Dracunculus medinensis''. A person becomes infected by drinking water containing water fleas infected with guinea worm larvae. The worms penetrate th ...

. So far, the only diseases completely eradicated by humankind are smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, declared eradicated in 1980, and rinderpest

Rinderpest (also cattle plague or steppe murrain) was an infectious viral disease of cattle, domestic buffalo, and many other species of even-toed ungulates, including gaurs, buffaloes, large antelope, deer, giraffes, wildebeests, and warthog ...

, declared eradicated in 2011. In April 2012, the World Health Assembly declared that the failure to completely eradicate polio would be a programmatic emergency for global public health, and that it "must not happen."

These efforts have hugely reduced the number of cases; from an estimated 350,000 cases in 1988 to a low of 483 cases in 2001, after which it remained at a level of about 1,000–2000 cases per year for a number of years.