Liszt Ferenc Zeneművészeti Egyetem 2013-ban felújított homlokzata.JPG on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Franz Liszt, in modern usage ''Liszt Ferenc'' . Liszt's Hungarian passport spelled his given name as "Ferencz". An orthographic reform of the Hungarian language in 1922 (which was 36 years after Liszt's death) changed the letter "cz" to simply "c" in all words except surnames; this has led to Liszt's given name being rendered in modern Hungarian usage as "Ferenc". From 1859 to 1867 he was officially Franz Ritter von Liszt; he was created a ''

Franz Liszt was born to Anna Liszt (née Maria Anna Lager)Genealogy of the Liszt family: Marriage of Maria Anna Lager and Adam Liszt

Franz Liszt was born to Anna Liszt (née Maria Anna Lager)Genealogy of the Liszt family: Marriage of Maria Anna Lager and Adam Liszt

pfarre-paudorf.com

/ref> and Adam Liszt on 22 October 1811, in the village of Doborján (German: Raiding) in

After attending a charity concert on 20 April 1832, for the victims of the Parisian cholera epidemic, organized by

After attending a charity concert on 20 April 1832, for the victims of the Parisian cholera epidemic, organized by

In 1833, Liszt began his relationship with the Countess

In 1833, Liszt began his relationship with the Countess

For the next eight years Liszt continued to tour Europe, spending holidays with the countess and their children on the island of Nonnenwerth on the Rhine in the summers of 1841 and 1843. In spring 1844, the couple finally separated. This was Liszt's most brilliant period as a concert pianist. Honors were showered on him and he was met with adulation wherever he went. Liszt wrote his

For the next eight years Liszt continued to tour Europe, spending holidays with the countess and their children on the island of Nonnenwerth on the Rhine in the summers of 1841 and 1843. In spring 1844, the couple finally separated. This was Liszt's most brilliant period as a concert pianist. Honors were showered on him and he was met with adulation wherever he went. Liszt wrote his

In February 1847, Liszt played in Kiev. There he met the Polish Princess

In February 1847, Liszt played in Kiev. There he met the Polish Princess

The 1860s were a period of great sadness in Liszt's private life. On 13 December 1859, he lost his 20-year-old son Daniel, and, on 11 September 1862, his 26-year-old daughter Blandine also died. In letters to friends, Liszt announced that he would retreat to a solitary living. He found it at the monastery ''Madonna del Rosario'', just outside Rome, where on 20 June 1863, he took up quarters in a small, spartan apartment. He had on 23 June 1857, already joined the Third Order of Saint Francis.

On 25 April 1865, he received the tonsure at the hands of Cardinal Gustav Adolf Hohenlohe, Hohenlohe. On 31 July 1865, he received the four minor orders of Ostiarius, porter, lector, exorcist, and acolyte. After this ordination, he was often called ''Abbé'' Liszt. On 14 August 1879, he was made an honorary canon (priest), canon of Albano Laziale, Albano.

On some occasions, Liszt took part in Rome's musical life. On 26 March 1863, at a concert at the Palazzo Altieri, he directed a programme of sacred music. The "Seligkeiten" of his ''Christus (Liszt), Christus-Oratorio'' and his "Cantico del Sol di Francesco d'Assisi", as well as Joseph Haydn, Haydn's ''The Creation (Haydn), Die Schöpfung'' and works by Johann Sebastian Bach, J. S. Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Beethoven, Niccolò Jommelli, Jommelli, Felix Mendelssohn, Mendelssohn, and Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Palestrina were performed. On 4 January 1866, Liszt directed the "Stabat mater" of his ''Christus-Oratorio'', and, on 26 February 1866, his ''Dante Symphony''. There were several further occasions of similar kind, but in comparison with the duration of Liszt's stay in Rome, they were exceptions.

In 1866, Liszt composed the Hungarian coronation ceremony for Franz Joseph and Elisabeth of Bavaria (Latin: Missa coronationalis). The Mass was first performed on 8 June 1867, at the coronation ceremony in the Matthias Church by Buda Castle in a six-section form. After the first performance, the Offertory was added, and, two years later, the Gradual.

Liszt was invited back to Weimar in 1869 to give master classes in piano playing. Two years later, he was asked to do the same in Budapest at the Hungarian Franz Liszt Academy of Music, Music Academy. From then until the end of his life, he made regular journeys between Rome, Weimar, and Budapest, continuing what he called his "vie trifurquée" or tripartite existence. It is estimated that Liszt traveled at least 4,000 miles a year during this period in his life – an exceptional figure despite his advancing age and the rigors of road and rail in the 1870s.

The 1860s were a period of great sadness in Liszt's private life. On 13 December 1859, he lost his 20-year-old son Daniel, and, on 11 September 1862, his 26-year-old daughter Blandine also died. In letters to friends, Liszt announced that he would retreat to a solitary living. He found it at the monastery ''Madonna del Rosario'', just outside Rome, where on 20 June 1863, he took up quarters in a small, spartan apartment. He had on 23 June 1857, already joined the Third Order of Saint Francis.

On 25 April 1865, he received the tonsure at the hands of Cardinal Gustav Adolf Hohenlohe, Hohenlohe. On 31 July 1865, he received the four minor orders of Ostiarius, porter, lector, exorcist, and acolyte. After this ordination, he was often called ''Abbé'' Liszt. On 14 August 1879, he was made an honorary canon (priest), canon of Albano Laziale, Albano.

On some occasions, Liszt took part in Rome's musical life. On 26 March 1863, at a concert at the Palazzo Altieri, he directed a programme of sacred music. The "Seligkeiten" of his ''Christus (Liszt), Christus-Oratorio'' and his "Cantico del Sol di Francesco d'Assisi", as well as Joseph Haydn, Haydn's ''The Creation (Haydn), Die Schöpfung'' and works by Johann Sebastian Bach, J. S. Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Beethoven, Niccolò Jommelli, Jommelli, Felix Mendelssohn, Mendelssohn, and Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Palestrina were performed. On 4 January 1866, Liszt directed the "Stabat mater" of his ''Christus-Oratorio'', and, on 26 February 1866, his ''Dante Symphony''. There were several further occasions of similar kind, but in comparison with the duration of Liszt's stay in Rome, they were exceptions.

In 1866, Liszt composed the Hungarian coronation ceremony for Franz Joseph and Elisabeth of Bavaria (Latin: Missa coronationalis). The Mass was first performed on 8 June 1867, at the coronation ceremony in the Matthias Church by Buda Castle in a six-section form. After the first performance, the Offertory was added, and, two years later, the Gradual.

Liszt was invited back to Weimar in 1869 to give master classes in piano playing. Two years later, he was asked to do the same in Budapest at the Hungarian Franz Liszt Academy of Music, Music Academy. From then until the end of his life, he made regular journeys between Rome, Weimar, and Budapest, continuing what he called his "vie trifurquée" or tripartite existence. It is estimated that Liszt traveled at least 4,000 miles a year during this period in his life – an exceptional figure despite his advancing age and the rigors of road and rail in the 1870s.

Liszt fell down the stairs of a hotel in Weimar on 2 July 1881. Though friends and colleagues had noticed swelling in his feet and legs when he had arrived in Weimar the previous month (an indication of possible congestive heart failure), he had been in good health up to that point and was still fit and active. He was left immobilized for eight weeks after the accident and never fully recovered from it. A number of ailments manifested themselves—dropsy, asthma, insomnia, a cataract in the left eye, and heart disease. The last-mentioned eventually contributed to Liszt's death. He became increasingly plagued by feelings of desolation, despair, and preoccupation with death—feelings that he expressed in his Late works of Franz Liszt, works from this period. As he told Lina Ramann, "I carry a deep sadness of the heart which must now and then break out in sound."

On 13 January 1886, while Claude Debussy was staying at the Villa Medici in Rome, Liszt met him there with Paul Vidal and Ernest Hébert, director of the French Academy. Liszt played ''Au bord d'une source'' from his ''

Liszt fell down the stairs of a hotel in Weimar on 2 July 1881. Though friends and colleagues had noticed swelling in his feet and legs when he had arrived in Weimar the previous month (an indication of possible congestive heart failure), he had been in good health up to that point and was still fit and active. He was left immobilized for eight weeks after the accident and never fully recovered from it. A number of ailments manifested themselves—dropsy, asthma, insomnia, a cataract in the left eye, and heart disease. The last-mentioned eventually contributed to Liszt's death. He became increasingly plagued by feelings of desolation, despair, and preoccupation with death—feelings that he expressed in his Late works of Franz Liszt, works from this period. As he told Lina Ramann, "I carry a deep sadness of the heart which must now and then break out in sound."

On 13 January 1886, while Claude Debussy was staying at the Villa Medici in Rome, Liszt met him there with Paul Vidal and Ernest Hébert, director of the French Academy. Liszt played ''Au bord d'une source'' from his ''

There are few, if any, good sources that give an impression of how Liszt really sounded from the 1820s.

There are few, if any, good sources that give an impression of how Liszt really sounded from the 1820s.

During his years as a traveling virtuoso, Liszt performed an enormous amount of music throughout Europe, but his core repertoire always centered on his own compositions, paraphrases, and transcriptions. Of Liszt's German concerts between 1840 and 1845, the five most frequently played pieces were the ''Grand galop chromatique'', Erlkönig (Schubert)#For solo piano (Liszt), his transcription of Schubert's ''Erlkönig'', ''Réminiscences de Don Juan'', ''Réminiscences de Robert le Diable'', and ''Réminiscences de Lucia di Lammermoor''. Among the works by other composers were Carl Maria von Weber, Weber's ''Invitation to the Dance (Weber), Invitation to the Dance''; Frédéric Chopin, Chopin Mazurkas (Chopin), mazurkas; études by composers like Ignaz Moscheles, Chopin, and

During his years as a traveling virtuoso, Liszt performed an enormous amount of music throughout Europe, but his core repertoire always centered on his own compositions, paraphrases, and transcriptions. Of Liszt's German concerts between 1840 and 1845, the five most frequently played pieces were the ''Grand galop chromatique'', Erlkönig (Schubert)#For solo piano (Liszt), his transcription of Schubert's ''Erlkönig'', ''Réminiscences de Don Juan'', ''Réminiscences de Robert le Diable'', and ''Réminiscences de Lucia di Lammermoor''. Among the works by other composers were Carl Maria von Weber, Weber's ''Invitation to the Dance (Weber), Invitation to the Dance''; Frédéric Chopin, Chopin Mazurkas (Chopin), mazurkas; études by composers like Ignaz Moscheles, Chopin, and

Among the composer's pianos in Weimar were an Sébastien Érard, Érard, a C. Bechstein, Bechstein piano, the Beethoven's John Broadwood & Sons, Broadwood grand and a Boisselot & Fils, Boisselot. It is known that Liszt was using Boisselot pianos in his Portugal tour and then later in 1847 in a tour to Kiev and Odessa. Liszt kept the piano at his Villa Altenburg residence in Weimar. This instrument is not in a playable condition now, and in 2011, at the order of Klassik Stiftung Weimar, a modern builder, Paul McNulty (piano maker), Paul McNulty, made a copy of the Boisselot piano which is now on display next to the original Liszt's instrument.

Liszt's interest in Bach's organ music in the early 1840s prompted him to commission a piano-organ from the Paris company Alexandre Père et Fils. The instrument was made in 1854 under Berlioz's supervision, using an 1853 Érard piano, a combination of piano and harmonium with three manuals and a pedal board. The company called it a "piano-Liszt" and installed it in Villa Altenburg in July 1854, the instrument is now exhibited in the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde collection in Vienna.

Liszt owned two other organs that were installed later in his Budapest residence. The first was a smaller version of Weimar's instrument, a combination piano and harmonium with two independent manuals, upper for the 1864 Érard piano, and lower for the harmonium, built again by Alexandre Père et Fils in 1865. The second was a "cabinet organ", a large concert harmonium built in Detroit and Boston by Mason & Hamlin and given to Liszt in 1877. Mason & Hamlin later sold a revised mass-produced model of this single manual reed organ as a "Liszt Organ". This harmonium was eventually sold to a "Mr. Smith", an Englishman living in the United States. Mr. Smith sold it to an American collector in 1911 for $50,000.

Among the composer's pianos in Weimar were an Sébastien Érard, Érard, a C. Bechstein, Bechstein piano, the Beethoven's John Broadwood & Sons, Broadwood grand and a Boisselot & Fils, Boisselot. It is known that Liszt was using Boisselot pianos in his Portugal tour and then later in 1847 in a tour to Kiev and Odessa. Liszt kept the piano at his Villa Altenburg residence in Weimar. This instrument is not in a playable condition now, and in 2011, at the order of Klassik Stiftung Weimar, a modern builder, Paul McNulty (piano maker), Paul McNulty, made a copy of the Boisselot piano which is now on display next to the original Liszt's instrument.

Liszt's interest in Bach's organ music in the early 1840s prompted him to commission a piano-organ from the Paris company Alexandre Père et Fils. The instrument was made in 1854 under Berlioz's supervision, using an 1853 Érard piano, a combination of piano and harmonium with three manuals and a pedal board. The company called it a "piano-Liszt" and installed it in Villa Altenburg in July 1854, the instrument is now exhibited in the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde collection in Vienna.

Liszt owned two other organs that were installed later in his Budapest residence. The first was a smaller version of Weimar's instrument, a combination piano and harmonium with two independent manuals, upper for the 1864 Érard piano, and lower for the harmonium, built again by Alexandre Père et Fils in 1865. The second was a "cabinet organ", a large concert harmonium built in Detroit and Boston by Mason & Hamlin and given to Liszt in 1877. Mason & Hamlin later sold a revised mass-produced model of this single manual reed organ as a "Liszt Organ". This harmonium was eventually sold to a "Mr. Smith", an Englishman living in the United States. Mr. Smith sold it to an American collector in 1911 for $50,000.

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music in one movement in which some extramusical program provides a narrative or illustrative element. This program may come from a poem, a story or novel, a painting, or another source. The term was first applied by Liszt to his 13 one-movement orchestral works in this vein. They were not pure symphony, symphonic movements in the classical sense because they dealt with descriptive subjects taken from mythology, Romantic literature, recent history, or imaginative fantasy. In other words, these works were programmatic rather than abstract. The form was a direct product of Romanticism which encouraged literary, pictorial, and dramatic associations in music. It developed into an important form of program music in the second half of the 19th century.

The first 12 symphonic poems were composed in the decade 1848–58 (though some use material conceived earlier); one other, ''Von der Wiege bis zum Grabe'' (''From the Cradle to the Grave''), followed in 1882. Liszt's intent, according to Hugh Macdonald, Hugh MacDonald in ''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'', was for these single-movement works "to display the traditional logic of symphonic thought." That logic, embodied in sonata form as musical development, was traditionally the unfolding of latent possibilities in given themes in rhythm, melody and harmony, either in part or in their entirety, as they were allowed to combine, separate and contrast with one another. To the resulting sense of struggle, Beethoven had added intensity of feeling and the involvement of his audiences in that feeling, beginning from the Symphony No. 3 (Beethoven), ''Eroica'' Symphony to use the elements of the craft of music—melody, Bass (sound), bass, counterpoint, rhythm and harmony—in a new synthesis of elements toward this end.

Liszt attempted in the symphonic poem to extend this revitalization of the nature of musical discourse and add to it the Romantic ideal of reconciling classical formal principles to external literary concepts. To this end, he combined elements of overture and symphony with descriptive elements, approaching symphonic first movements in form and scale. While showing extremely creative amendments to sonata form, Liszt used compositional devices such as cyclic form, leitmotif, motifs and

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music in one movement in which some extramusical program provides a narrative or illustrative element. This program may come from a poem, a story or novel, a painting, or another source. The term was first applied by Liszt to his 13 one-movement orchestral works in this vein. They were not pure symphony, symphonic movements in the classical sense because they dealt with descriptive subjects taken from mythology, Romantic literature, recent history, or imaginative fantasy. In other words, these works were programmatic rather than abstract. The form was a direct product of Romanticism which encouraged literary, pictorial, and dramatic associations in music. It developed into an important form of program music in the second half of the 19th century.

The first 12 symphonic poems were composed in the decade 1848–58 (though some use material conceived earlier); one other, ''Von der Wiege bis zum Grabe'' (''From the Cradle to the Grave''), followed in 1882. Liszt's intent, according to Hugh Macdonald, Hugh MacDonald in ''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'', was for these single-movement works "to display the traditional logic of symphonic thought." That logic, embodied in sonata form as musical development, was traditionally the unfolding of latent possibilities in given themes in rhythm, melody and harmony, either in part or in their entirety, as they were allowed to combine, separate and contrast with one another. To the resulting sense of struggle, Beethoven had added intensity of feeling and the involvement of his audiences in that feeling, beginning from the Symphony No. 3 (Beethoven), ''Eroica'' Symphony to use the elements of the craft of music—melody, Bass (sound), bass, counterpoint, rhythm and harmony—in a new synthesis of elements toward this end.

Liszt attempted in the symphonic poem to extend this revitalization of the nature of musical discourse and add to it the Romantic ideal of reconciling classical formal principles to external literary concepts. To this end, he combined elements of overture and symphony with descriptive elements, approaching symphonic first movements in form and scale. While showing extremely creative amendments to sonata form, Liszt used compositional devices such as cyclic form, leitmotif, motifs and

Ritter

Ritter (German for "knight") is a designation used as a title of nobility in German-speaking areas. Traditionally it denotes the second-lowest rank within the nobility, standing above " Edler" and below "Freiherr" (Baron). As with most titles a ...

'' (knight) by Emperor Francis Joseph I

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I (german: Franz Joseph Karl, hu, Ferenc József Károly, 18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, and the other states of the Habsburg monarchy from 2 December 1848 until his ...

in 1859, but never used this title of nobility in public. The title was necessary to marry the Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein

Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein (8 February 18199 March 1887) was a Polish noblewoman (''szlachcianka'') who is best known for her 40-year relationship with musician Franz Liszt. She was also an amateur journalist and essayist. It is co ...

without her losing her privileges, but after the marriage fell through, Liszt transferred the title to his uncle Eduard in 1867. Eduard's son was Franz von Liszt

Franz Eduard Ritter von Liszt (2 March 1851 – 21 June 1919) was a German jurist, criminologist and international law reformer. As a legal scholar, he was a proponent of the modern sociological and historical school of law. From 1898 until 1917, ...

., group=n (22 October 1811 – 31 July 1886) was a Hungarian composer, pianist and teacher of the Romantic period

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

. With a diverse body of work

The complete works of an artist, writer, musician, group, etc., is a collection of all of their cultural works. For example, '' Complete Works of Shakespeare'' is an edition containing all the plays and poems of William Shakespeare. A ''Complete ...

spanning more than six decades, he is considered to be one of the most prolific and influential composers of his era and remains one of the most popular composers in modern concert piano repertoire.

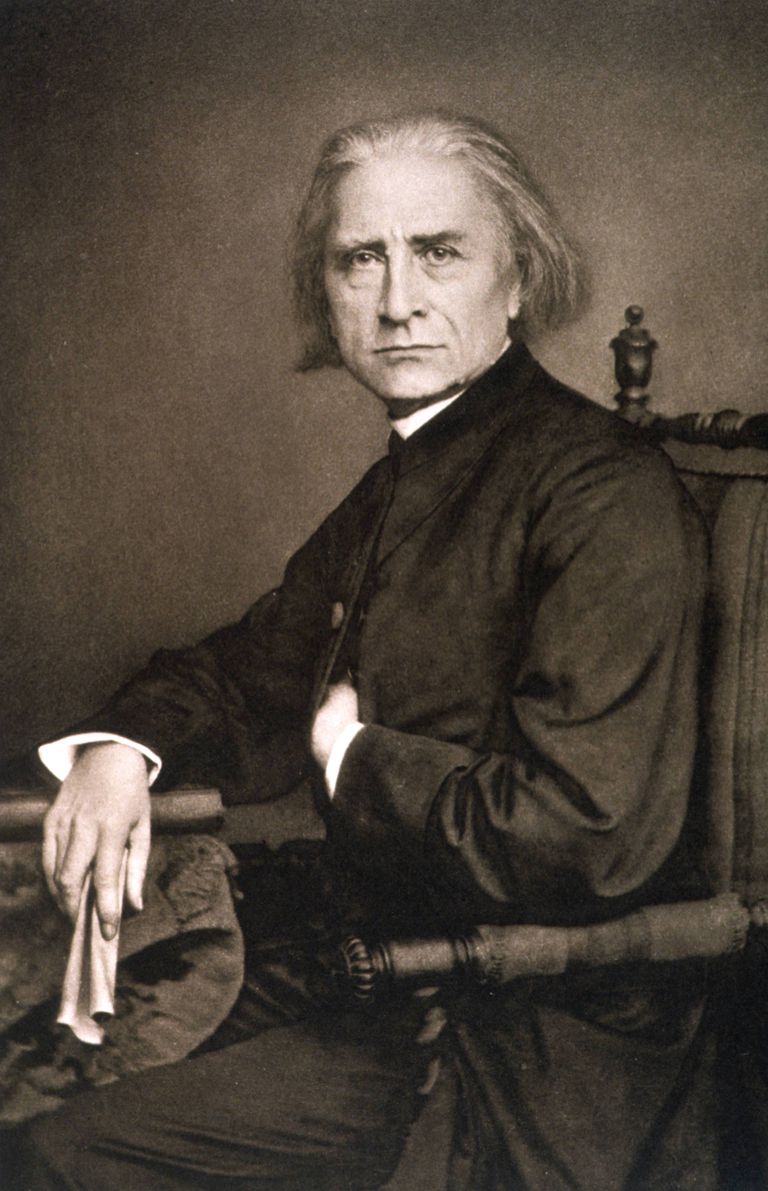

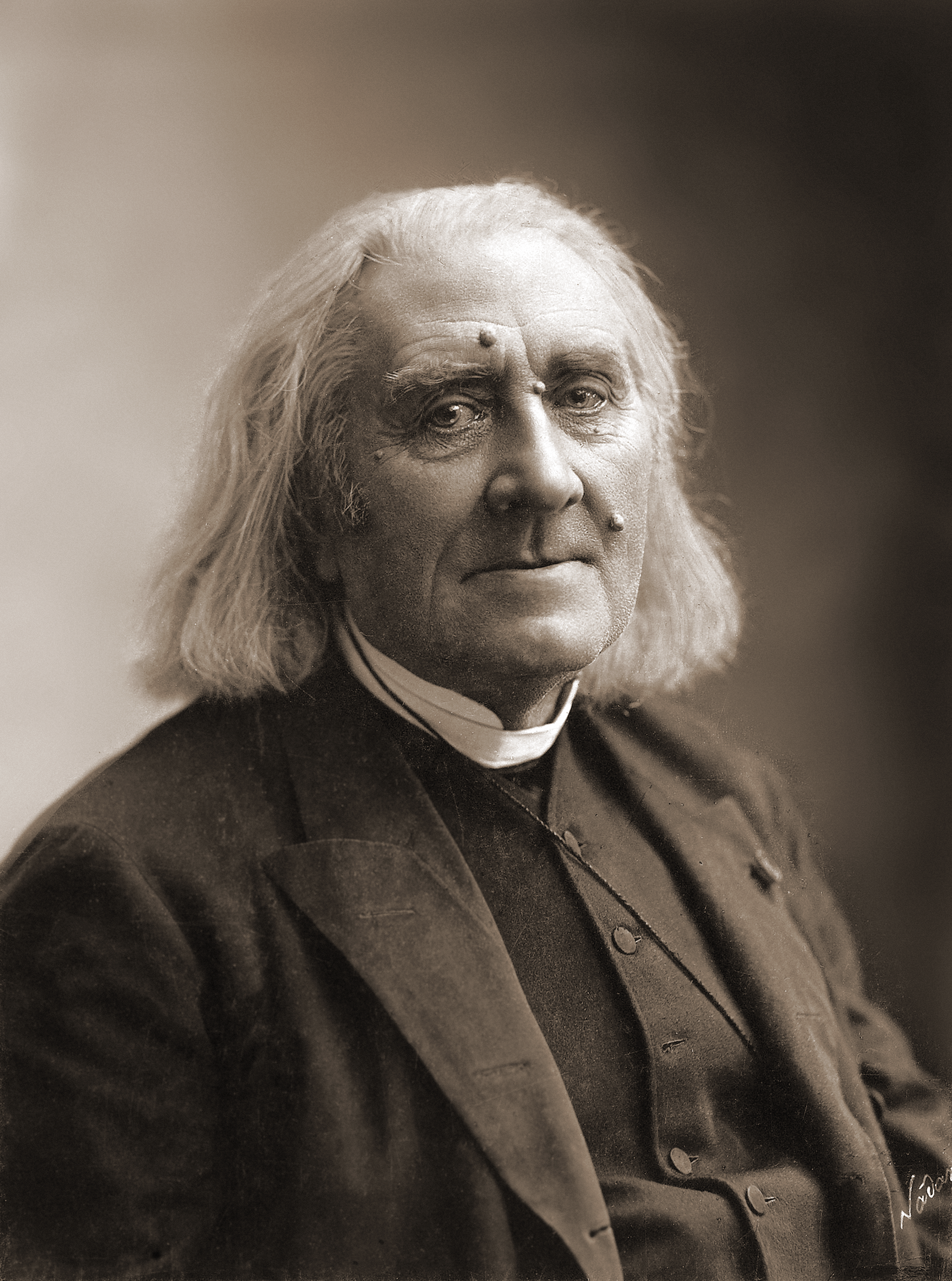

Liszt first gained renown during the early nineteenth century for his virtuoso skill as a pianist. Regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time, he toured Europe during the 1830s and 1840s, often playing for charity. In these years, Liszt developed a reputation for his powerful performances as well as his physical attractiveness. In what has now been dubbed "Lisztomania

Lisztomania or Liszt fever was the intense fan frenzy directed toward Hungarian composer Franz Liszt during his performances. This frenzy first occurred in Berlin in 1841 and the term was later coined by Heinrich Heine in a feuilleton he wrote on ...

", he rose to a degree of stardom and popularity among the public not experienced by the virtuosos who preceded him. Whereas earlier performers mostly served the upper class, Liszt attracted a more general audience. During this period and into his later life, Liszt was a friend, musical promoter and benefactor to many composers of his time, including Frédéric Chopin, Charles-Valentin Alkan, Richard Wagner, Hector Berlioz, Robert Schumann, Clara Schumann

Clara Josephine Schumann (; née Wieck; 13 September 1819 – 20 May 1896) was a German pianist, composer, and piano teacher. Regarded as one of the most distinguished pianists of the Romantic era, she exerted her influence over the course of a ...

, Camille Saint-Saëns, Edvard Grieg

Edvard Hagerup Grieg ( , ; 15 June 18434 September 1907) was a Norwegian composer and pianist. He is widely considered one of the foremost Romantic era composers, and his music is part of the standard classical repertoire worldwide. His use of ...

, Ole Bull, Joachim Raff, Mikhail Glinka, and Alexander Borodin.

Liszt was one of the most prominent representatives of the New German School

The New German School (german: link=no, Neudeutsche Schule, ) is a term introduced in 1859 by Franz Brendel, editor of the ''Neue Zeitschrift für Musik'', to describe certain trends in German music. Although the term has frequently been used in ...

(german: Neudeutsche Schule, link=no). He left behind an extensive and diverse body of work that influenced his forward-looking contemporaries and anticipated 20th-century ideas and trends. Among Liszt's musical contributions were the symphonic poem, developing thematic transformation Thematic transformation (also known as thematic metamorphosis or thematic development) is a musical technique in which a leitmotif, or theme, is developed by changing the theme by using permutation ( transposition or modulation, inversion, and retr ...

as part of his experiments in musical form, and radical innovations in harmony. Liszt has also been regarded as a forefather of Impressionism in music

Impressionism in music was a movement among various composers in Western classical music (mainly during the late 19th and early 20th centuries) whose music focuses on mood and atmosphere, "conveying the moods and emotions aroused by the subjec ...

, with his ''Années de pèlerinage

''Années de pèlerinage'' (French for ''Years of Pilgrimage'') ( S.160, S.161, S.162, S.163) is a set of three suites for solo piano by Franz Liszt. Much of it derives from his earlier work, ''Album d'un voyageur'', his first major published pian ...

'', often regarded as his masterwork, featuring many impressionistic qualities. In a radical departure from his earlier compositional styles, many of Liszt’s later works also feature experiments in atonality, foreshadowing the serialist movement of the 20th century.

Life

Early life

Franz Liszt was born to Anna Liszt (née Maria Anna Lager)Genealogy of the Liszt family: Marriage of Maria Anna Lager and Adam Liszt

Franz Liszt was born to Anna Liszt (née Maria Anna Lager)Genealogy of the Liszt family: Marriage of Maria Anna Lager and Adam Lisztpfarre-paudorf.com

/ref> and Adam Liszt on 22 October 1811, in the village of Doborján (German: Raiding) in

Sopron County

Sopron (German: ''Ödenburg'') was an administrative county (comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is now divided between Austria and Hungary. The capital of the county was Sopron.

Geography

Sopron county shared borders with the A ...

, in the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

, Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence ...

. Liszt's father played the piano, violin, cello, and guitar. He had been in the service of Prince Nikolaus II Esterházy and knew Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have led ...

, Hummel, and Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classic ...

personally. At age six, Franz began listening attentively to his father's piano playing. Franz also found exposure to music through attending mass as well as traveling Romani bands that toured the Hungarian countryside. Adam began teaching him the piano at age seven, and Franz began composing in an elementary manner when he was eight. He appeared in concerts at Sopron

Sopron (; german: Ödenburg, ; sl, Šopron) is a city in Hungary on the Austrian border, near Lake Neusiedl/Lake Fertő.

History

Ancient times-13th century

When the area that is today Western Hungary was a province of the Roman Empire, a ...

and Pressburg ( Hungarian: Pozsony, present-day Bratislava, Slovakia) in October and November 1820 at age nine. After the concerts, a group of wealthy sponsors offered to finance Franz's musical education in Vienna.

There, Liszt received piano lessons from Carl Czerny

Carl Czerny (; 21 February 1791 – 15 July 1857) was an Austrian composer, teacher, and pianist of Czech origin whose music spanned the late Classical and early Romantic eras. His vast musical production amounted to over a thousand works and ...

, who in his own youth had been a student of Beethoven and Hummel. He also received lessons in composition from Ferdinando Paer

Ferdinando Paer (1 July 1771 – 3 May 1839) was an Italian composer known for his operas. He was of Austrian descent and used the German spelling Pär in application for printing in Venice, and later in France the spelling Paër.

Life and career ...

and Antonio Salieri

Antonio Salieri (18 August 17507 May 1825) was an Italian classical composer, conductor, and teacher. He was born in Legnago, south of Verona, in the Republic of Venice, and spent his adult life and career as a subject of the Habsburg monarchy ...

, who was then the music director of the Viennese court. Liszt's public debut in Vienna on 1 December 1822, at a concert at the "Landständischer Saal", was a great success. He was greeted in Austrian and Hungarian aristocratic circles and met Beethoven and Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. Despite his short lifetime, Schubert left behind a vast ''oeuvre'', including more than 600 secular vocal wor ...

. In the spring of 1823, when his one-year leave of absence came to an end, Adam Liszt asked Prince Esterházy in vain for two more years. Adam Liszt, therefore, took his leave of the Prince's services. At the end of April 1823, the family returned to Hungary for the last time. At the end of May 1823, the family traveled to Vienna once more.

Towards the end of 1823 or early 1824, Liszt's first composition was published, his Variation on a Waltz by Diabelli (now S. 147), appeared as Variation 24 in of '' Vaterländischer Künstlerverein''. This anthology, commissioned by Anton Diabelli

Anton (or Antonio) Diabelli (5 September 17818 April 1858) was an Austrian music publisher, editor and composer. Best known in his time as a publisher, he is most familiar today as the composer of the waltz on which Ludwig van Beethoven wrote ...

, includes 50 variations on his waltz by 50 different composers being taken up by Beethoven's 33 variations on the same theme, which are now separately better known simply as his ''Diabelli Variations

The ''33 Variations on a waltz by Anton Diabelli'', Op. 120, commonly known as the ''Diabelli Variations'', is a set of variations for the piano written between 1819 and 1823 by Ludwig van Beethoven on a waltz composed by Anton Diabelli. It f ...

'', Op. 120. Liszt's inclusion in the Diabelli project (he was described in it as "an 11-year-old boy, born in Hungary") was almost certainly at the instigation of Czerny, his teacher, and also a participant. Liszt was the only child composer in the anthology.

Adolescence in Paris

After his father's death in 1827, Liszt moved to Paris; for the next five years, he lived with his mother in a small apartment. He gave up touring, and in order to earn money, Liszt gave lessons on playing piano and composition, often from early morning until late at night. His students were scattered across the city and he had to cover long distances. Because of this, he kept uncertain hours and also took up smoking and drinking— habits he would continue throughout his life. The following year, Liszt fell in love with one of his pupils, Caroline de Saint-Cricq, the daughter ofCharles X

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI and Lou ...

's minister of commerce, Pierre de Saint-Cricq. Her father, however, insisted that the affair be broken off.

Liszt fell very ill, to the extent that an obituary notice was printed in a Paris newspaper, and he underwent a long period of religious doubts and pessimism. He again stated a wish to join the Church but was dissuaded this time by his mother. He had many discussions with the Abbé de Lamennais, who acted as his spiritual father, and also with Chrétien Urhan, a German-born violinist who introduced him to the Saint-Simonists. Urhan also wrote music that was anti-classical and highly subjective, with titles such as ''Elle et moi, La Salvation angélique'' and ''Les Regrets'', and may have whetted the young Liszt's taste for musical romanticism. Equally important for Liszt was Urhan's earnest championship of Schubert, which may have stimulated his own lifelong devotion to that composer's music.

During this period, Liszt read widely to overcome his lack of general education, and he soon came into contact with many of the leading authors and artists of his day, including Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

, Alphonse de Lamartine

Alphonse Marie Louis de Prat de Lamartine (; 21 October 179028 February 1869), was a French author, poet, and statesman who was instrumental in the foundation of the Second Republic and the continuation of the Tricolore as the flag of France. ...

and Heinrich Heine. He composed practically nothing in these years. Nevertheless, the July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after the first in 1789. It led to the overthrow of King ...

of 1830 inspired him to sketch a Revolutionary Symphony based on the events of the "three glorious days," and he took a greater interest in events surrounding him. He met Hector Berlioz on 4 December 1830, the day before the premiere of the '' Symphonie fantastique''. Berlioz's music made a strong impression on Liszt, especially later when he was writing for orchestra. He also inherited from Berlioz the diabolic quality of many of his works.

Paganini

After attending a charity concert on 20 April 1832, for the victims of the Parisian cholera epidemic, organized by

After attending a charity concert on 20 April 1832, for the victims of the Parisian cholera epidemic, organized by Niccolò Paganini

Niccolò (or Nicolò) Paganini (; 27 October 178227 May 1840) was an Italian violinist and composer. He was the most celebrated violin virtuoso of his time, and left his mark as one of the pillars of modern violin technique. His 24 Caprices fo ...

, Liszt became determined to become as great a virtuoso on the piano as Paganini was on the violin. Paris in the 1830s had become the nexus for pianistic activities, with dozens of pianists dedicated to perfection at the keyboard. Some, such as Sigismond Thalberg

Sigismond Thalberg (8 January 1812 – 27 April 1871) was an Austrian composer and one of the most distinguished virtuoso pianists of the 19th century.

Family

He was born in Pâquis near Geneva on 8 January 1812. According to his own account, h ...

and Alexander Dreyschock, focused on specific aspects of technique, such as the "three-hand effect

The three-hand effect (or three-hand technique) is a means of playing on the piano with only two hands, but producing the impression that one is using three hands. Typically this effect is produced by keeping the melody in the middle register, wit ...

" and octaves, respectively. While it has since been referred to as the "flying trapeze" school of piano playing, this generation also solved some of the most intractable problems of piano technique, raising the general level of performance to previously unimagined heights. Liszt's strength and ability to stand out in this company was in mastering all the aspects of piano technique cultivated singly and assiduously by his rivals.

In 1833, he made transcriptions of several works by Berlioz including the ''Symphonie fantastique''. His chief motive in doing so, especially with the ''Symphonie'', was to help the poverty-stricken Berlioz, whose symphony remained unknown and unpublished. Liszt bore the expense of publishing the transcription himself and played it many times to help popularize the original score. He was also forming a friendship with a third composer who influenced him, Frédéric Chopin; under his influence, Liszt's poetic and romantic side began to develop.

With Countess Marie d'Agoult

In 1833, Liszt began his relationship with the Countess

In 1833, Liszt began his relationship with the Countess Marie d'Agoult

Marie Cathérine Sophie, Comtesse d'Agoult (née de Flavigny; 31 December 18055 March 1876), was a Franco-German romantic author and historian, known also by her pen name, Daniel Stern.

Life

Marie was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, with th ...

. In addition to this, at the end of April 1834, he made the acquaintance of Felicité de Lamennais. Under the influence of both, Liszt's creative output exploded.

In 1835, the countess left her husband and family to join Liszt in Geneva

, neighboring_municipalities= Carouge, Chêne-Bougeries, Cologny, Lancy, Grand-Saconnex, Pregny-Chambésy, Vernier, Veyrier

, website = https://www.geneve.ch/

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevr ...

; Liszt's daughter with the countess, Blandine, was born there on 18 December. Liszt taught at the newly founded Geneva Conservatory, wrote a manual of piano technique (later lost) and contributed essays for the Paris ''Revue et gazette musicale''. In these essays, he argued for the raising of the artist from the status of a servant to a respected member of the community.

For the next four years, Liszt and the countess lived together, mainly in Switzerland and Italy, where their daughter, Cosima, was born on Lake Como, with occasional visits to Paris. On 9 May 1839, Liszt's and the countess's only son, Daniel, was born, but that autumn relations between them became strained. Liszt heard that plans for a Beethoven Monument in Bonn were in danger of collapse for lack of funds and pledged his support. Doing so meant returning to the life of a touring virtuoso. The countess returned to Paris with the children, while Liszt gave six concerts in Vienna, then toured Hungary.

Touring Europe

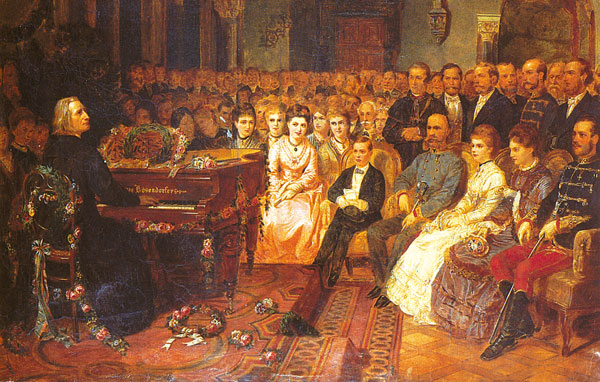

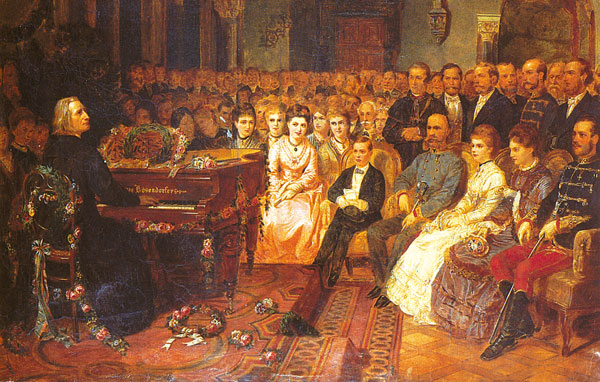

For the next eight years Liszt continued to tour Europe, spending holidays with the countess and their children on the island of Nonnenwerth on the Rhine in the summers of 1841 and 1843. In spring 1844, the couple finally separated. This was Liszt's most brilliant period as a concert pianist. Honors were showered on him and he was met with adulation wherever he went. Liszt wrote his

For the next eight years Liszt continued to tour Europe, spending holidays with the countess and their children on the island of Nonnenwerth on the Rhine in the summers of 1841 and 1843. In spring 1844, the couple finally separated. This was Liszt's most brilliant period as a concert pianist. Honors were showered on him and he was met with adulation wherever he went. Liszt wrote his Three Concert Études

Three Concert Études (''Trois études de concert''), S.144, is a set of three piano études by Franz Liszt, composed between 1845–49 and published in Paris as ''Trois caprices poétiques'' with the three individual titles as they are known tod ...

between 1845 and 1849. Since he often appeared three or four times a week in concert, it could be safe to assume that he appeared in public well over a thousand times during this eight-year period. Moreover, his great fame as a pianist, which he would continue to enjoy long after he had officially retired from the concert stage, was based mainly on his accomplishments during this time.

During his virtuoso heyday, Liszt was described by the writer Hans Christian Andersen as a "slim young man...ith

The Ith () is a ridge in Germany's Central Uplands which is up to 439 m high. It lies about 40 km southwest of Hanover and, at 22 kilometres, is the longest line of crags in North Germany.

Geography

Location

The Ith is immediatel ...

dark hair hung around his pale face". He was seen as handsome by many, with the German poet Heinrich Heine writing concerning his showmanship during concerts: "How powerful, how shattering was his mere physical appearance".

In 1841, Franz Liszt was admitted to the Freemason's lodge "Unity" "Zur Einigkeit", in Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

. He was promoted to the second degree and elected master as a member of the lodge "Zur Eintracht", in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

. From 1845, he was also an honorary member of the lodge "Modestia cum Libertate" at Zürich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Zürich ...

and in 1870 of the lodge in Pest (Budapest-Hungary). After 1842, "Lisztomania

Lisztomania or Liszt fever was the intense fan frenzy directed toward Hungarian composer Franz Liszt during his performances. This frenzy first occurred in Berlin in 1841 and the term was later coined by Heinrich Heine in a feuilleton he wrote on ...

"—coined by 19th-century German poet and Liszt's contemporary, Heinrich Heine—swept across Europe. The reception that Liszt enjoyed, as a result, can be described only as hysterical. Women fought over his silk handkerchiefs and velvet gloves, which they ripped to shreds as souvenirs. This atmosphere was fuelled in great part by the artist's mesmeric personality and stage presence. Many witnesses later testified that Liszt's playing raised the mood of audiences to a level of mystical ecstasy.

On 14 March 1842, Liszt received an honorary doctorate from the University of Königsberg

The University of Königsberg (german: Albertus-Universität Königsberg) was the university of Königsberg in East Prussia. It was founded in 1544 as the world's second Protestant academy (after the University of Marburg) by Duke Albert of Pruss ...

—an honor unprecedented at the time and an especially important one from the perspective of the German tradition. Liszt never used 'Dr. Liszt' or 'Dr. Franz Liszt' publicly. Ferdinand Hiller

Ferdinand (von) Hiller (24 October 1811 – 11 May 1885) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, writer and music director.

Biography

Ferdinand Hiller was born to a wealthy Jewish family in Frankfurt am Main, where his father Justus (orig ...

, a rival of Liszt at the time, was allegedly highly jealous of the decision made by the university.

Adding to his reputation was the fact that Liszt gave away much of his proceeds to charity and humanitarian causes in his whole life. In fact, Liszt had made so much money by his mid-forties that virtually all his performing fees after 1857 went to charity. While his work for the Beethoven monument and the Hungarian National School of Music is well known, he also gave generously to the building fund of Cologne Cathedral

Cologne Cathedral (german: Kölner Dom, officially ', English: Cathedral Church of Saint Peter) is a Catholic cathedral in Cologne, North Rhine-Westphalia. It is the seat of the Archbishop of Cologne and of the administration of the Archdiocese o ...

, the establishment of a '' Gymnasium'' at Dortmund, and the construction of the Leopold Church in Pest. There were also private donations to hospitals, schools, and charitable organizations such as the Leipzig Musicians Pension Fund. When he found out about the Great Fire of Hamburg, which raged for three days during May 1842 and destroyed much of the city, he gave concerts in aid of the thousands of homeless there.

Liszt in Weimar

In February 1847, Liszt played in Kiev. There he met the Polish Princess

In February 1847, Liszt played in Kiev. There he met the Polish Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein

Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein (8 February 18199 March 1887) was a Polish noblewoman (''szlachcianka'') who is best known for her 40-year relationship with musician Franz Liszt. She was also an amateur journalist and essayist. It is co ...

, who was to become one of the most significant people in the rest of his life. She persuaded him to concentrate on composition, which meant giving up his career as a traveling virtuoso. After a tour of the Balkans, Turkey, and Russia that summer, Liszt gave his final concert for pay at Kirovohrad, Yelisavetgrad in September. He spent the winter with the princess at her estate in Woronince. By retiring from the concert platform at 35, while still at the height of his powers, Liszt succeeded in keeping the legend of his playing untarnished.

The following year, Liszt took up a long-standing invitation of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia (1786–1859), Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia to settle at Weimar, where he had been appointed ''Kapellmeister Extraordinaire'' in 1842, remaining there until 1861. During this period he acted as conductor at court concerts and on special occasions at the theatre. He gave lessons to a number of pianists, including the great virtuoso Hans von Bülow, who married Liszt's daughter Cosima in 1857 (years later, she would marry Richard Wagner). He also wrote articles championing Berlioz and Wagner. Finally, Liszt had ample time to compose and during the next 12 years revised or produced those orchestral and choral pieces upon which his reputation as a composer mainly rested.

During those twelve years, he also helped raise the profile of the exiled Wagner by conducting the overtures of his operas in concert, Liszt and Wagner would have a profound friendship that lasted until Wagner's death in Venice in 1883.

Princess Carolyne lived with Liszt during his years in Weimar. She eventually wished to marry Liszt, but since she had been previously married and her husband, Russian military officer Prince Nikolaus zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Ludwigsburg (1812–1864), was still alive, she had to convince the Roman Catholic authorities that her marriage to him had been invalid. After huge efforts and a monstrously intricate process, she was temporarily successful (September 1860). It was planned that the couple would marry in Rome, on 22 October 1861, Liszt's 50th birthday. Although Liszt arrived in Rome on 21 October, the marriage was made impossible by a letter that had arrived the previous day to the Pope himself. It appears that both her husband and the Tsar of Russia had managed to quash permission for the marriage at the Vatican. The Russian government also impounded her several estates in the Polish Ukraine, which made her later marriage to anybody unfeasible.

Rome, Weimar, Budapest

The 1860s were a period of great sadness in Liszt's private life. On 13 December 1859, he lost his 20-year-old son Daniel, and, on 11 September 1862, his 26-year-old daughter Blandine also died. In letters to friends, Liszt announced that he would retreat to a solitary living. He found it at the monastery ''Madonna del Rosario'', just outside Rome, where on 20 June 1863, he took up quarters in a small, spartan apartment. He had on 23 June 1857, already joined the Third Order of Saint Francis.

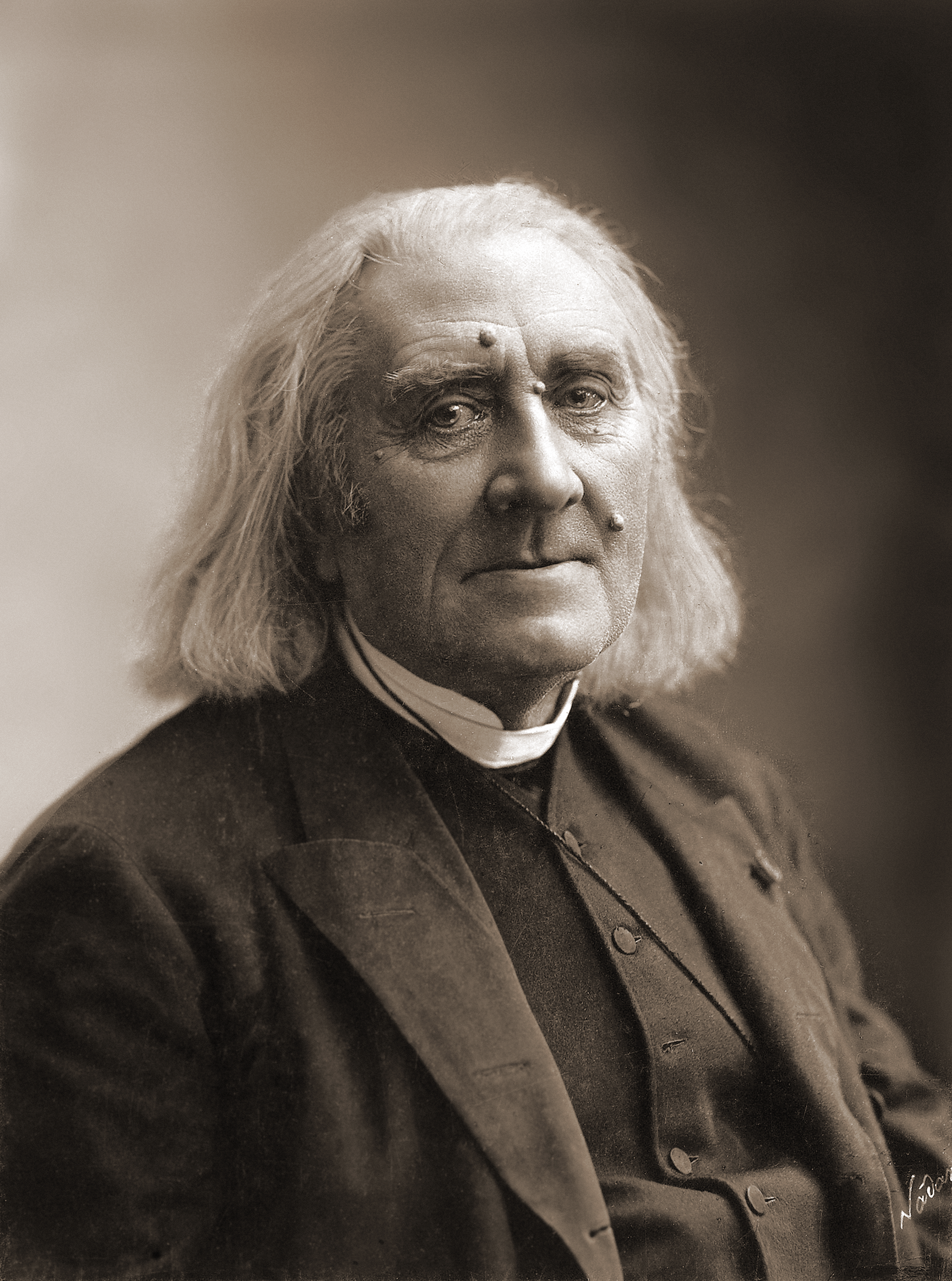

On 25 April 1865, he received the tonsure at the hands of Cardinal Gustav Adolf Hohenlohe, Hohenlohe. On 31 July 1865, he received the four minor orders of Ostiarius, porter, lector, exorcist, and acolyte. After this ordination, he was often called ''Abbé'' Liszt. On 14 August 1879, he was made an honorary canon (priest), canon of Albano Laziale, Albano.

On some occasions, Liszt took part in Rome's musical life. On 26 March 1863, at a concert at the Palazzo Altieri, he directed a programme of sacred music. The "Seligkeiten" of his ''Christus (Liszt), Christus-Oratorio'' and his "Cantico del Sol di Francesco d'Assisi", as well as Joseph Haydn, Haydn's ''The Creation (Haydn), Die Schöpfung'' and works by Johann Sebastian Bach, J. S. Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Beethoven, Niccolò Jommelli, Jommelli, Felix Mendelssohn, Mendelssohn, and Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Palestrina were performed. On 4 January 1866, Liszt directed the "Stabat mater" of his ''Christus-Oratorio'', and, on 26 February 1866, his ''Dante Symphony''. There were several further occasions of similar kind, but in comparison with the duration of Liszt's stay in Rome, they were exceptions.

In 1866, Liszt composed the Hungarian coronation ceremony for Franz Joseph and Elisabeth of Bavaria (Latin: Missa coronationalis). The Mass was first performed on 8 June 1867, at the coronation ceremony in the Matthias Church by Buda Castle in a six-section form. After the first performance, the Offertory was added, and, two years later, the Gradual.

Liszt was invited back to Weimar in 1869 to give master classes in piano playing. Two years later, he was asked to do the same in Budapest at the Hungarian Franz Liszt Academy of Music, Music Academy. From then until the end of his life, he made regular journeys between Rome, Weimar, and Budapest, continuing what he called his "vie trifurquée" or tripartite existence. It is estimated that Liszt traveled at least 4,000 miles a year during this period in his life – an exceptional figure despite his advancing age and the rigors of road and rail in the 1870s.

The 1860s were a period of great sadness in Liszt's private life. On 13 December 1859, he lost his 20-year-old son Daniel, and, on 11 September 1862, his 26-year-old daughter Blandine also died. In letters to friends, Liszt announced that he would retreat to a solitary living. He found it at the monastery ''Madonna del Rosario'', just outside Rome, where on 20 June 1863, he took up quarters in a small, spartan apartment. He had on 23 June 1857, already joined the Third Order of Saint Francis.

On 25 April 1865, he received the tonsure at the hands of Cardinal Gustav Adolf Hohenlohe, Hohenlohe. On 31 July 1865, he received the four minor orders of Ostiarius, porter, lector, exorcist, and acolyte. After this ordination, he was often called ''Abbé'' Liszt. On 14 August 1879, he was made an honorary canon (priest), canon of Albano Laziale, Albano.

On some occasions, Liszt took part in Rome's musical life. On 26 March 1863, at a concert at the Palazzo Altieri, he directed a programme of sacred music. The "Seligkeiten" of his ''Christus (Liszt), Christus-Oratorio'' and his "Cantico del Sol di Francesco d'Assisi", as well as Joseph Haydn, Haydn's ''The Creation (Haydn), Die Schöpfung'' and works by Johann Sebastian Bach, J. S. Bach, Ludwig van Beethoven, Beethoven, Niccolò Jommelli, Jommelli, Felix Mendelssohn, Mendelssohn, and Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Palestrina were performed. On 4 January 1866, Liszt directed the "Stabat mater" of his ''Christus-Oratorio'', and, on 26 February 1866, his ''Dante Symphony''. There were several further occasions of similar kind, but in comparison with the duration of Liszt's stay in Rome, they were exceptions.

In 1866, Liszt composed the Hungarian coronation ceremony for Franz Joseph and Elisabeth of Bavaria (Latin: Missa coronationalis). The Mass was first performed on 8 June 1867, at the coronation ceremony in the Matthias Church by Buda Castle in a six-section form. After the first performance, the Offertory was added, and, two years later, the Gradual.

Liszt was invited back to Weimar in 1869 to give master classes in piano playing. Two years later, he was asked to do the same in Budapest at the Hungarian Franz Liszt Academy of Music, Music Academy. From then until the end of his life, he made regular journeys between Rome, Weimar, and Budapest, continuing what he called his "vie trifurquée" or tripartite existence. It is estimated that Liszt traveled at least 4,000 miles a year during this period in his life – an exceptional figure despite his advancing age and the rigors of road and rail in the 1870s.

Royal Academy of Music at Budapest

From the early 1860s, there were attempts to obtain a position for Liszt in Hungary. In 1871, the Hungarian Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy made a new attempt writing on 4 June 1871, to the Hungarian King (the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria, Franz Joseph I), requesting an annual grant of 4,000 Gulden and the rank of a "Königlicher Rat" ("Crown Councillor") for Liszt, who in return would permanently settle in Budapest, directing the orchestra of the National Theatre as well as musical institutions. The plan of the foundation of a Royal Academy was agreed upon by the Hungarian Parliament in 1872. In March 1875, Liszt was nominated as president. The Academy was officially opened on 14 November 1875 with Liszt's colleague Ferenc Erkel as director, Kornél Ábrányi and Robert Volkmann. Liszt himself came in March 1876 to give some lessons and a charity concert. In spite of the conditions under which Liszt had been appointed as "Königlicher Rat", he neither directed the orchestra of the National Theatre nor permanently settled in Hungary. Typically, he would arrive in mid-winter in Budapest. After one or two concerts of his students, by the beginning of spring, he left. He never took part in the final examinations, which were in the summer of every year. Some of the pupils joined the lessons that Liszt gave in the summer in Weimar. In 1873, on the occasion of Liszt's 50th anniversary as a performing artist, the city of Budapest instituted a "Franz Liszt Stiftung" ("Franz Liszt Foundation"), to provide stipends of 200 Gulden for three students of the Academy who had shown excellent abilities with regard to Hungarian music. Liszt alone decided the allocation of these stipends. It was Liszt's habit to declare all students who took part in his lessons as his private students. In consequence, almost none of them paid any fees to the Academy. A ministerial order of 13 February 1884 decreed that all those who took part in Liszt's lessons had to pay an annual charge of 30 Gulden. In fact, the Academy was, in any case, a net gainer, since Liszt donated its revenue from his charity concerts.Last years

Liszt fell down the stairs of a hotel in Weimar on 2 July 1881. Though friends and colleagues had noticed swelling in his feet and legs when he had arrived in Weimar the previous month (an indication of possible congestive heart failure), he had been in good health up to that point and was still fit and active. He was left immobilized for eight weeks after the accident and never fully recovered from it. A number of ailments manifested themselves—dropsy, asthma, insomnia, a cataract in the left eye, and heart disease. The last-mentioned eventually contributed to Liszt's death. He became increasingly plagued by feelings of desolation, despair, and preoccupation with death—feelings that he expressed in his Late works of Franz Liszt, works from this period. As he told Lina Ramann, "I carry a deep sadness of the heart which must now and then break out in sound."

On 13 January 1886, while Claude Debussy was staying at the Villa Medici in Rome, Liszt met him there with Paul Vidal and Ernest Hébert, director of the French Academy. Liszt played ''Au bord d'une source'' from his ''

Liszt fell down the stairs of a hotel in Weimar on 2 July 1881. Though friends and colleagues had noticed swelling in his feet and legs when he had arrived in Weimar the previous month (an indication of possible congestive heart failure), he had been in good health up to that point and was still fit and active. He was left immobilized for eight weeks after the accident and never fully recovered from it. A number of ailments manifested themselves—dropsy, asthma, insomnia, a cataract in the left eye, and heart disease. The last-mentioned eventually contributed to Liszt's death. He became increasingly plagued by feelings of desolation, despair, and preoccupation with death—feelings that he expressed in his Late works of Franz Liszt, works from this period. As he told Lina Ramann, "I carry a deep sadness of the heart which must now and then break out in sound."

On 13 January 1886, while Claude Debussy was staying at the Villa Medici in Rome, Liszt met him there with Paul Vidal and Ernest Hébert, director of the French Academy. Liszt played ''Au bord d'une source'' from his ''Années de pèlerinage

''Années de pèlerinage'' (French for ''Years of Pilgrimage'') ( S.160, S.161, S.162, S.163) is a set of three suites for solo piano by Franz Liszt. Much of it derives from his earlier work, ''Album d'un voyageur'', his first major published pian ...

'', as well as his arrangement of Ave Maria (Schubert), Schubert's ''Ave Maria'' for the musicians. Debussy in later years described Liszt's pedalling as "like a form of breathing." Debussy and Vidal performed their piano duet arrangement of Liszt's Faust Symphony; allegedly, Liszt fell asleep during this.

The composer Camille Saint-Saëns, an old friend, whom Liszt had once called "the greatest organist in the world", dedicated his Symphony No. 3 (Saint-Saëns), Symphony No. 3 "Organ Symphony" to Liszt; it had premiered in London only a few weeks before the death of its dedicatee.

Liszt died in Bayreuth, Germany, on 31 July 1886, at the age of 74, officially as a result of pneumonia, which he may have contracted during the Bayreuth Festival hosted by his daughter Cosima Liszt, Cosima. Questions have been posed as to whether medical malpractice played a part in his death. He was buried on 3 August 1886, in the against his wishes.

Pianist

Many musicians consider Liszt to be the greatest pianist who ever lived. The critic Peter G. Davis has opined: "Perhaps [Liszt] was not the most transcendent virtuoso who ever lived, but his audiences thought he was."Performing style

There are few, if any, good sources that give an impression of how Liszt really sounded from the 1820s.

There are few, if any, good sources that give an impression of how Liszt really sounded from the 1820s. Carl Czerny

Carl Czerny (; 21 February 1791 – 15 July 1857) was an Austrian composer, teacher, and pianist of Czech origin whose music spanned the late Classical and early Romantic eras. His vast musical production amounted to over a thousand works and ...

said Liszt was a natural who played according to feeling, and reviews of his concerts especially praise the brilliance, strength, and precision in his playing. At least one also mentions his ability to keep absolute tempo, which may be caused by his father's insistence on practicing with a metronome. His repertoire then consisted primarily of pieces in the style of the brilliant Viennese school, such as concertos by Hummel and works by his former teacher Czerny, and his concerts often included a chance for the boy to display his prowess in improvisation. Liszt possessed notable sight-reading skills.

Following the death of Liszt's father in 1827 and his hiatus from life as a touring virtuoso, Liszt's playing likely gradually developed a more personal style. One of the most detailed descriptions of his playing from that time comes from the winter of 1831–32 when he was earning a living primarily as a teacher in Paris. Among his pupils was Valerie Boissier, whose mother, Caroline, kept a careful diary of the lessons:

M. Liszt's playing contains abandonment, a liberated feeling, but even when it becomes impetuous and energetic in his fortissimo, it is still without harshness and dryness. [...] [He] draws from the piano tones that are purer, mellower, and stronger than anyone has been able to do; his touch has an indescribable charm. [...] He is the enemy of affected, stilted, contorted expressions. Most of all, he wants truth in musical sentiment, and so he makes a psychological study of his emotions to convey them as they are. Thus, a strong expression is often followed by a sense of fatigue and dejection, a kind of coldness, because this is the way nature works.Liszt was sometimes mocked in the press for facial expressions and gestures at the piano. Also noted were the extravagant liberties that he could take with the text of a score. Berlioz tells how Liszt would add cadenzas, tremolos, and trills when he played the first movement of Beethoven's ''Moonlight'' Sonata and created a dramatic scene by changing the tempo between Largo and Presto. In his ''Baccalaureus letter'' to George Sand from the beginning of 1837, Liszt admitted that he had done so to gain applause and promised to follow both the letter and the spirit of a score from then on. It has been debated to what extent he realized his promise, however. By July 1840, the British newspaper ''The Times'' could still report:

His performance commenced with Handel's Fugue in E minor, which was played by Liszt with avoidance of everything approaching meretricious ornament and indeed scarcely any additions, except a multitude of appropriate harmonies, casting a glow of color over the beauties of the composition and infusing into it a spirit which from no other hand it ever before received.

Repertoire

During his years as a traveling virtuoso, Liszt performed an enormous amount of music throughout Europe, but his core repertoire always centered on his own compositions, paraphrases, and transcriptions. Of Liszt's German concerts between 1840 and 1845, the five most frequently played pieces were the ''Grand galop chromatique'', Erlkönig (Schubert)#For solo piano (Liszt), his transcription of Schubert's ''Erlkönig'', ''Réminiscences de Don Juan'', ''Réminiscences de Robert le Diable'', and ''Réminiscences de Lucia di Lammermoor''. Among the works by other composers were Carl Maria von Weber, Weber's ''Invitation to the Dance (Weber), Invitation to the Dance''; Frédéric Chopin, Chopin Mazurkas (Chopin), mazurkas; études by composers like Ignaz Moscheles, Chopin, and

During his years as a traveling virtuoso, Liszt performed an enormous amount of music throughout Europe, but his core repertoire always centered on his own compositions, paraphrases, and transcriptions. Of Liszt's German concerts between 1840 and 1845, the five most frequently played pieces were the ''Grand galop chromatique'', Erlkönig (Schubert)#For solo piano (Liszt), his transcription of Schubert's ''Erlkönig'', ''Réminiscences de Don Juan'', ''Réminiscences de Robert le Diable'', and ''Réminiscences de Lucia di Lammermoor''. Among the works by other composers were Carl Maria von Weber, Weber's ''Invitation to the Dance (Weber), Invitation to the Dance''; Frédéric Chopin, Chopin Mazurkas (Chopin), mazurkas; études by composers like Ignaz Moscheles, Chopin, and Ferdinand Hiller

Ferdinand (von) Hiller (24 October 1811 – 11 May 1885) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, writer and music director.

Biography

Ferdinand Hiller was born to a wealthy Jewish family in Frankfurt am Main, where his father Justus (orig ...

; but also major works by Beethoven, Schumann, Weber, and Hummel and from time to time even selections from Bach, Handel, and Scarlatti.

Most of the concerts were shared with other artists, so Liszt also often accompanied singers, participated in chamber music, or performed works with an orchestra in addition to his own solo part. Frequently-played works include Weber's ''Konzertstück in F minor (Weber), Konzertstück'', Beethoven's Emperor Concerto and Choral Fantasy (Beethoven), Choral Fantasy, and Liszt's reworking of the ''Hexameron'' for piano and orchestra. His chamber music repertoire included Johann Nepomuk Hummel's Septet, Beethoven's Archduke Trio and Violin Sonata No. 9 (Beethoven), Kreutzer Sonata, and a large selection of songs by composers like Gioachino Rossini, Gaetano Donizetti, Beethoven, and especially Franz Schubert. At some concerts, Liszt could not find musicians to share the program with and so was among the first to give solo piano recitals in the modern sense of the word. The term was coined by the publisher Frederick Beale, who suggested it for Liszt's concert at the Hanover Square Rooms in London on 9 June 1840, even though Liszt had already given concerts by himself by March 1839.

Instruments

Among the composer's pianos in Weimar were an Sébastien Érard, Érard, a C. Bechstein, Bechstein piano, the Beethoven's John Broadwood & Sons, Broadwood grand and a Boisselot & Fils, Boisselot. It is known that Liszt was using Boisselot pianos in his Portugal tour and then later in 1847 in a tour to Kiev and Odessa. Liszt kept the piano at his Villa Altenburg residence in Weimar. This instrument is not in a playable condition now, and in 2011, at the order of Klassik Stiftung Weimar, a modern builder, Paul McNulty (piano maker), Paul McNulty, made a copy of the Boisselot piano which is now on display next to the original Liszt's instrument.

Liszt's interest in Bach's organ music in the early 1840s prompted him to commission a piano-organ from the Paris company Alexandre Père et Fils. The instrument was made in 1854 under Berlioz's supervision, using an 1853 Érard piano, a combination of piano and harmonium with three manuals and a pedal board. The company called it a "piano-Liszt" and installed it in Villa Altenburg in July 1854, the instrument is now exhibited in the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde collection in Vienna.

Liszt owned two other organs that were installed later in his Budapest residence. The first was a smaller version of Weimar's instrument, a combination piano and harmonium with two independent manuals, upper for the 1864 Érard piano, and lower for the harmonium, built again by Alexandre Père et Fils in 1865. The second was a "cabinet organ", a large concert harmonium built in Detroit and Boston by Mason & Hamlin and given to Liszt in 1877. Mason & Hamlin later sold a revised mass-produced model of this single manual reed organ as a "Liszt Organ". This harmonium was eventually sold to a "Mr. Smith", an Englishman living in the United States. Mr. Smith sold it to an American collector in 1911 for $50,000.

Among the composer's pianos in Weimar were an Sébastien Érard, Érard, a C. Bechstein, Bechstein piano, the Beethoven's John Broadwood & Sons, Broadwood grand and a Boisselot & Fils, Boisselot. It is known that Liszt was using Boisselot pianos in his Portugal tour and then later in 1847 in a tour to Kiev and Odessa. Liszt kept the piano at his Villa Altenburg residence in Weimar. This instrument is not in a playable condition now, and in 2011, at the order of Klassik Stiftung Weimar, a modern builder, Paul McNulty (piano maker), Paul McNulty, made a copy of the Boisselot piano which is now on display next to the original Liszt's instrument.

Liszt's interest in Bach's organ music in the early 1840s prompted him to commission a piano-organ from the Paris company Alexandre Père et Fils. The instrument was made in 1854 under Berlioz's supervision, using an 1853 Érard piano, a combination of piano and harmonium with three manuals and a pedal board. The company called it a "piano-Liszt" and installed it in Villa Altenburg in July 1854, the instrument is now exhibited in the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde collection in Vienna.

Liszt owned two other organs that were installed later in his Budapest residence. The first was a smaller version of Weimar's instrument, a combination piano and harmonium with two independent manuals, upper for the 1864 Érard piano, and lower for the harmonium, built again by Alexandre Père et Fils in 1865. The second was a "cabinet organ", a large concert harmonium built in Detroit and Boston by Mason & Hamlin and given to Liszt in 1877. Mason & Hamlin later sold a revised mass-produced model of this single manual reed organ as a "Liszt Organ". This harmonium was eventually sold to a "Mr. Smith", an Englishman living in the United States. Mr. Smith sold it to an American collector in 1911 for $50,000.

Musical works

Liszt was a prolific composer. He is best known for his piano music, but he also wrote for orchestra and for other ensembles, virtually always including keyboard. His piano works are often marked by their difficulty. Some of his works are Program music, programmatic, based on extra-musical inspirations such as poetry or art. Liszt is credited with the creation of the symphonic poem.Piano music

The largest and best-known portion of Liszt's music is his original piano work. During the Weimar period, he composed 19 Hungarian Rhapsodies, themselves revisions of his own Magyar Dalok/Rhapsódiák. His thoroughly revised masterwork, "''Années de pèlerinage

''Années de pèlerinage'' (French for ''Years of Pilgrimage'') ( S.160, S.161, S.162, S.163) is a set of three suites for solo piano by Franz Liszt. Much of it derives from his earlier work, ''Album d'un voyageur'', his first major published pian ...

''" ("Years of Pilgrimage") includes arguably his most provocative and stirring pieces. This set of three suites ranges from the virtuosity of the Suisse Orage (Storm) to the subtle and imaginative visualizations of artworks by Michelangelo and Raphael in the second set. "''Années de pèlerinage''" contains some pieces which are loose transcriptions of Liszt's own earlier compositions; the first "year" recreates his early pieces of "''Album d'un voyageur''", while the second book includes a resetting of his own song transcriptions once separately published as "''Tre sonetti di Petrarca''" ("Three sonnets of Petrarch"). The relative obscurity of the vast majority of his works may be explained by the immense number of pieces he composed, and the level of technical difficulty which was present in much of his composition.

Liszt's piano works are usually divided into two categories: original works, and transcriptions, paraphrases, or fantasies on works by other composers. Examples of his own works are ''Harmonies poétiques et religieuses'' of May 1833 and the Piano Sonata (Liszt), Piano Sonata in B minor (1853). Liszt's transcriptions of other composers include Schubert songs, fantasies on operatic melodies, and his piano arrangements of symphonies by Hector Berlioz and Ludwig van Beethoven. Liszt also made piano arrangements of his own instrumental and vocal works, such as the arrangement of the second movement "''Gretchen''" of his ''Faust Symphony'', the first "Mephisto Waltzes#No. 1, S. 514, ''Mephisto Waltz''," the "Liebesträume, ''Liebesträume'' No. 3," and the two volumes of his "''Buch der Lieder''."

Transcriptions

Liszt wrote substantial quantities of piano Transcription (music), transcriptions of a wide variety of music. Indeed, about half of his works are arrangements of music by other composers. He played many of them himself in celebrated performances. In the mid-19th century, orchestral performances were much less common than they are today and were not available at all outside major cities; thus, Liszt's transcriptions played a major role in popularising a wide array of music such as Beethoven Symphonies (Liszt), Beethoven's symphonies. The pianist Cyprien Katsaris has stated that he prefers Liszt's transcriptions of the symphonies to the originals, and Hans von Bülow admitted that Liszt's transcription of his ''Dante Sonett'' "Tanto gentile" was much more refined than the original he himself had composed. Liszt's transcriptions of Schubert songs, his fantasies on operatic melodies, and his piano arrangements of symphonies by Berlioz and Beethoven are other well-known examples of piano transcriptions. In addition to piano transcriptions, Liszt also transcribed about a dozen works for organ, such as Otto Nicolai's ''Ecclesiastical Festival Overture on the chorale "Ein feste Burg"'', Orlando di Lasso's motet ''Regina coeli'', some Chopin preludes, and excerpts of Bach's BWV 21, Cantata No. 21 and Wagner's ''Tannhäuser''.Organ music

Liszt wrote his two largest organ works between 1850 and 1855 while he was living in Weimar, a city with a long tradition of organ music, most notably that of J.S. Bach. Humphrey Searle calls these works—the Fantasy and Fugue on the chorale "Ad nos, ad salutarem undam" and the Prelude and Fugue on B-A-C-H—Liszt's "only important original organ works" and Derek Watson (actor and musicologist), Derek Watson, writing in his ''Liszt'', considered them among the most significant organ works of the nineteenth century, heralding the work of such key organist-musicians as Reger, Franck, and Saint-Saëns, among others. ''Ad nos'' is an extended fantasia, Adagio, and fugue, lasting over half an hour, and the Prelude and Fugue on B-A-C-H include chromatic writing which sometimes removes the sense of tonality. Liszt also wrote the monumental set of variations on the first section of the second movement chorus from List of Bach cantatas, Bach's cantata ''Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen, BWV 12'' (which Bach later reworked as the ' in the Mass in B minor), which he composed after the death of his daughter in 1862. He also wrote a Requiem for organ solo, intended to be performed liturgically, along with the spoken Requiem Mass.Lieder

Franz Liszt composed about six dozen original songs with piano accompaniment. In most cases, the lyrics were in German or French, but there are also some songs in Italian and Hungarian and one song in English. Liszt began with the song "Angiolin dal biondo crin" in 1839, and, by 1844, had composed about two dozen songs. Some of them had been published as single pieces. In addition, there was an 1843–1844 series ''Buch der Lieder''. The series had been projected for three volumes, consisting of six songs each, but only two volumes appeared. Today, Liszt's songs are relatively obscure. The song "Ich möchte hingehn" is sometimes cited because of a single bar, which resembles the Tristan chord, opening motif of Wagner's ''Tristan und Isolde''. It is often claimed that Liszt wrote that motif ten years before Wagner started work on ''Tristan'' in 1857. The original version of "Ich möchte hingehn" was certainly composed in 1844 or 1845; however, there are four manuscripts, and only a single one, a copy by August Conradi, contains the bar with the ''Tristan'' motif. It is on a paste-over in Liszt's hand. Since in the second half of 1858 Liszt was preparing his songs for publication and he had at that time just received the first act of Wagner's ''Tristan'', it is most likely that the version on the paste-over was a Musical quotation, quotation from Wagner.Programme music

Liszt, in some of his works, supported the relatively new idea of program music—that is, music intended to evoke extra-musical ideas such as a depiction of a landscape, a poem, a particular character or personage. (By contrast, absolute music stands for itself and is intended to be appreciated without any particular reference to the outside world.) Liszt's own point of view regarding program music can for the time of his youth be taken from the preface of the ''Album d'un voyageur'' (1837). According to this, a landscape could evoke a certain kind of mood. Since a piece of music could also evoke a mood, a mysterious resemblance with the landscape could be imagined. In this sense, the music would not paint the landscape, but it would match the landscape in a third category, the mood. In July 1854, Liszt stated in his essay about Berlioz and ''Harold en Italie, Harold in Italy'' that not all music was program music. If in the heat of a debate, a person would go so far as to claim the contrary, it would be better to put all ideas of program music aside. But it would be possible to take means like harmony, modulation, rhythm, instrumentation, and others to let a musical motif endure a fate. In any case, a program should be added to a piece of music only if it was necessarily needed for an adequate understanding of that piece. Still later, in a letter to Marie d'Agoult of 15 November 1864, Liszt wrote:Without any reserve I completely subscribe to the rule of which you so kindly want to remind me, that those musical works which are in a general sense following a program must take effect on imagination and emotion, independent of any program. In other words: All beautiful music must be first-rate and always satisfy the absolute rules of music which are not to be violated or prescribed.

Symphonic poems

A symphonic poem or tone poem is a piece of orchestral music in one movement in which some extramusical program provides a narrative or illustrative element. This program may come from a poem, a story or novel, a painting, or another source. The term was first applied by Liszt to his 13 one-movement orchestral works in this vein. They were not pure symphony, symphonic movements in the classical sense because they dealt with descriptive subjects taken from mythology, Romantic literature, recent history, or imaginative fantasy. In other words, these works were programmatic rather than abstract. The form was a direct product of Romanticism which encouraged literary, pictorial, and dramatic associations in music. It developed into an important form of program music in the second half of the 19th century.

The first 12 symphonic poems were composed in the decade 1848–58 (though some use material conceived earlier); one other, ''Von der Wiege bis zum Grabe'' (''From the Cradle to the Grave''), followed in 1882. Liszt's intent, according to Hugh Macdonald, Hugh MacDonald in ''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'', was for these single-movement works "to display the traditional logic of symphonic thought." That logic, embodied in sonata form as musical development, was traditionally the unfolding of latent possibilities in given themes in rhythm, melody and harmony, either in part or in their entirety, as they were allowed to combine, separate and contrast with one another. To the resulting sense of struggle, Beethoven had added intensity of feeling and the involvement of his audiences in that feeling, beginning from the Symphony No. 3 (Beethoven), ''Eroica'' Symphony to use the elements of the craft of music—melody, Bass (sound), bass, counterpoint, rhythm and harmony—in a new synthesis of elements toward this end.