Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a

Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant

physicians

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

,

astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the

Islamic Golden Age, and the father of early modern medicine.

Sajjad H. Rizvi

Sajjad Hayder Rizvi is an intellectual historian and professor of Islamic intellectual history and Islamic studies at the University of Exeter.

Biography

Rizvi completed his BA and MA in modern history, as well as his MPhil in modern middle East s ...

has called Avicenna "arguably the most influential philosopher of the

pre-modern era

The term premodern refers to the period in human history immediately preceding the modern era, as well as the conceptual framework in the humanities and social sciences relating to the artistic, literary and philosophical practices which preceded t ...

". He was a Muslim

Peripatetic

Peripatetic may refer to:

*Peripatetic school, a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece

*Peripatetic axiom

* Peripatetic minority, a mobile population moving among settled populations offering a craft or trade.

*Peripatetic Jats

There are several ...

philosopher influenced by Greek

Aristotelian philosophy

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the socia ...

. Of the 450 works he is believed to have written, around 240 have survived, including 150 on philosophy and 40 on medicine.

His most famous works are ''

The Book of Healing

''The Book of Healing'' (; ; also known as ) is a scientific and philosophical encyclopedia written by Abu Ali ibn Sīna (aka Avicenna) from medieval Persia, near Bukhara in Maverounnahr. He most likely began to compose the book in 1014, comp ...

'', a philosophical and scientific encyclopedia, and ''

The Canon of Medicine'', a

medical encyclopedia which became a standard medical text at many medieval

universities and remained in use as late as 1650. Besides philosophy and medicine, Avicenna's corpus includes writings on

astronomy,

alchemy,

geography and geology,

psychology,

Islamic theology,

logic,

mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

,

physics, and works of

poetry.

Name

' is a

Latin corruption of the

Arabic patronym Ibn Sīnā (), meaning "Son of Sina". However, Avicenna was not the son but the great-great-grandson of a man named Sina. His formal

Arabic name

Arabic language names have historically been based on a long naming system. Many people from the Arabic-speaking and also Muslim countries have not had given/ middle/family names but rather a chain of names. This system remains in use throughout ...

was Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn bin ʿAbdullāh ibn al-Ḥasan bin ʿAlī bin Sīnā al-Balkhi al-Bukhari ().

Circumstances

Avicenna created an extensive corpus of works during what is commonly known as the

Islamic Golden Age, in which the translations of

Byzantine Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

,

Persian and

Indian texts were studied extensively. Greco-Roman (

Mid- and

Neo-Platonic

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some ide ...

, and

Aristotelian) texts translated by the

Kindi Kindi may refer to:

*Al-Kindi (surname)

*Kindi Department, department of Boulkiemdé, Burkina Faso

**Kindi, Kindi, its capital

*Kindi, Andemtenga, a town in Andemtenga Department, Burkina Faso

*Kindi (Tanzanian ward), Moshi Rural district, Kilimanj ...

school were commented, redacted and developed substantially by Islamic intellectuals, who also built upon Persian and

Indian mathematical systems,

astronomy,

algebra,

trigonometry and

medicine.

The

Samanid dynasty in the eastern part of

Persia,

Greater Khorasan and Central Asia as well as the

Buyid dynasty in the western part of Persia and

Iraq provided a thriving atmosphere for scholarly and cultural development. Under the Samanids,

Bukhara

Bukhara (Uzbek language, Uzbek: /, ; tg, Бухоро, ) is the List of cities in Uzbekistan, seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan, with a population of 280,187 , and the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara ...

rivaled

Baghdad as a cultural capital of the

Islamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In ...

. There, Avicenna had access to the great libraries of

Balkh

), named for its green-tiled ''Gonbad'' ( prs, گُنبَد, dome), in July 2001

, pushpin_map=Afghanistan#Bactria#West Asia

, pushpin_relief=yes

, pushpin_label_position=bottom

, pushpin_mapsize=300

, pushpin_map_caption=Location in Afghanistan ...

,

Khwarezm

Khwarazm (; Old Persian: ''Hwârazmiya''; fa, خوارزم, ''Xwârazm'' or ''Xârazm'') or Chorasmia () is a large oasis region on the Amu Darya river delta in western Central Asia, bordered on the north by the (former) Aral Sea, on the ...

,

Gorgan,

Rey Rey may refer to:

*Rey (given name), a given name

*Rey (surname), a surname

* Rey (''Star Wars''), a character in the ''Star Wars'' films

* Rey, Iran, a city in Iran

* Ray County, in Tehran Province of Iran

* ''Rey'' (film), a 2015 Indian film

*The ...

,

Isfahan

Isfahan ( fa, اصفهان, Esfahân ), from its Achaemenid empire, ancient designation ''Aspadana'' and, later, ''Spahan'' in Sassanian Empire, middle Persian, rendered in English as ''Ispahan'', is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Regio ...

and

Hamadan.

Various texts (such as the 'Ahd with Bahmanyar) show that Avicenna debated philosophical points with the greatest scholars of the time.

Aruzi Samarqandi Ahmad ibn Umar ibn Alī, known as Nizamī-i Arūzī-i Samarqandī ( fa, نظامی عروضی) and also Arudi ("The Prosodist"), was a Persian poet and prose writer who flourished between 1110 and 1161. He is particularly famous for his ''Chahar Ma ...

describes how before Avicenna left

Khwarezm

Khwarazm (; Old Persian: ''Hwârazmiya''; fa, خوارزم, ''Xwârazm'' or ''Xârazm'') or Chorasmia () is a large oasis region on the Amu Darya river delta in western Central Asia, bordered on the north by the (former) Aral Sea, on the ...

he had met

Al-Biruni (a famous scientist and astronomer),

Abu Nasr Iraqi (a renowned mathematician),

Abu Sahl Masihi

Abu Sahl 'Isa ibn Yahya al-Masihi al-Jurjani ( fa, ابو سهل عيسى بن يحيى مسيحی گرگانی) was a Christian Persian physician,Firoozeh Papan-Matin, ''Beyond death: the mystical teachings of ʻAyn al-Quḍāt al-Hamadhān ...

(a respected philosopher) and Abu al-Khayr Khammar (a great physician). The study of the

Quran and the

Hadith also thrived, and Islamic philosophy, ''

fiqh'' and

theology (''

kalaam

''ʿIlm al-Kalām'' ( ar, عِلْم الكَلام, literally "science of discourse"), usually foreshortened to ''Kalām'' and sometimes called "Islamic scholastic theology" or "speculative theology", is the philosophical study of Islamic doc ...

'') were all further developed by Avicenna and his opponents at this time.

Biography

Early life and education

Avicenna was born in in the village of Afshana in

Transoxiana to a family of Persian stock. The village was near the

Samanid

The Samanid Empire ( fa, سامانیان, Sāmāniyān) also known as the Samanian Empire, Samanid dynasty, Samanid amirate, or simply as the Samanids) was a Persianate Sunni Muslim empire, of Iranian dehqan origin. The empire was centred in Kho ...

capital of

Bukhara

Bukhara (Uzbek language, Uzbek: /, ; tg, Бухоро, ) is the List of cities in Uzbekistan, seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan, with a population of 280,187 , and the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara ...

, which was his mother's hometown. His father Abd Allah was a native of the city of

Balkh

), named for its green-tiled ''Gonbad'' ( prs, گُنبَد, dome), in July 2001

, pushpin_map=Afghanistan#Bactria#West Asia

, pushpin_relief=yes

, pushpin_label_position=bottom

, pushpin_mapsize=300

, pushpin_map_caption=Location in Afghanistan ...

in

Tukharistan. An official of the Samanid bureaucracy, he had served as the governor of a village of the royal estate of Harmaytan (near Bukhara) during the reign of

Nuh II (). Avicenna also had a younger brother. A few years later, the family settled in Bukhara, a center of learning, which attracted many scholars. It was there that Avicenna was educated, which early on was seemingly administered by his father. Although both Avicenna's father and brother had converted to

Ismailism, he himself did not follow the faith. He was instead an adherent of the

Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

Hanafi school, which was also followed by the Samanids.

Avicenna was first schooled in the

Quran and literature, and by the age of 10, he had

memorized the entire Quran. He was later sent by his father to an Indian greengrocer, who taught him

arithmetic

Arithmetic () is an elementary part of mathematics that consists of the study of the properties of the traditional operations on numbers— addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponentiation, and extraction of roots. In the 19th ...

. Afterwards, he was schooled in

Jurisprudence by the Hanafi

jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyses and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal qualification in law and often a legal practitioner. In the Uni ...

Ismail al-Zahid. Some time later, Avicenna's father invited the physician and philosopher Abu Abdallah al-Natili to their house to educate Avicenna. Together, they studied the ''

Isagoge'' of

Porphyry (died 305) and possibly the

''Categories'' of

Aristotle (died 322 BC) as well. After Avicenna had read the ''

Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it canoni ...

'' of

Ptolemy (died 170) and ''

Euclid's Elements'', Natili told him to continue his research independently. By the time Avicenna was eighteen, he was well-educated in Greek sciences. Although Avicenna only mentions Natili as his teacher in his

autobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English peri ...

, he most likely had other teachers as well, such as the physicians Abu Mansur Qumri and

Abu Sahl al-Masihi.

Career

In Bukhara and Gurganj

At the age of seventeen, Avicenna was made a physician of

Nuh II. By the time Avicenna was at least 21 years old, his father died. He was subsequently given an administrative post, possibly succeeding his father as the governor of Harmaytan. Avicenna later moved to

Gurganj

Konye-Urgench ( tk, Köneürgenç / Көнеүргенч; fa, کهنه گرگانج, ''Kuhna Gurgānj'', literally "Old Gurgānj"), also known as Old Urgench or Urganj, is a city of about 30,000 inhabitants in north Turkmenistan, just south fro ...

, the capital of

Khwarazm, which he reports that he did due to "necessity". The date he went to the place is uncertain, as he reports that he served the ''

Khwarazmshah'' (ruler) of the region, the

Ma'munid Abu al-Hasan Ali. The latter ruled from 997 to 1009, which indicates that Avicenna moved sometime during that period. He may have moved in 999, the year which the Samanid state fell after the Turkic

Qarakhanids

The Kara-Khanid Khanate (; ), also known as the Karakhanids, Qarakhanids, Ilek Khanids or the Afrasiabids (), was a Turkic khanate that ruled Central Asia in the 9th through the early 13th century. The dynastic names of Karakhanids and Ilek K ...

captured Bukhara and imprisoned the Samanid ruler

Abd al-Malik II. Due to his high position and strong connection with the Samanids, Avicenna may have found himself in an unfavorable position after the fall of his suzerain. It was through the minister of Gurganj, Abu'l-Husayn as-Sahi, a patron of Greek sciences, that Avicenna entered into the service of Abu al-Hasan Ali. Under the Ma'munids, Gurganj became a centre of learning, attracting many prominent figures, such as Avicenna and his former teacher Abu Sahl al-Masihi, the mathematician

Abu Nasr Mansur, the physician

Ibn al-Khammar Abū al-Khayr al-Ḥasan ibn Suwār ibn Bābā ibn Bahnām, called Ibn al-Khammār (born 942), was an East Syriac Christian philosopher and physician who taught and worked in Baghdad. He was a prolific translator from Syriac into Arabic and also wr ...

, and the

philologist al-Tha'alibi.

In Gurgan

Avicenna later moved due to "necessity" once more (in 1012), this time to the west. There he travelled through the

Khurasan

Greater Khorāsān,Dabeersiaghi, Commentary on Safarnâma-e Nâsir Khusraw, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr: 1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235–236 or Khorāsān ( pal, Xwarāsān; fa, خراسان ), is a historical eastern region in the Iranian Plate ...

i cities of

Nasa,

Abivard

Abiward or Abi-ward, was an ancient Sassanid city in modern-day Turkmenistan. Archaeological excavations at the ancient city of Abiward have been made in the last century about 8 km west of Kaka

Kaka may refer to:

People Nickname or given ...

,

Tus,

Samangan and

Jajarm. He was planning to visit the ruler of the city of

Gurgan, the

Ziyarid Qabus (), a cultivated patron of writing, whose court attracted many distinguished poets and scholars. However, when Avicenna eventually arrived, he discovered that the ruler had been dead since the winter of 1013. Avicenna then left Gurgan for

Dihistan

The Dahae, also known as the Daae, Dahas or Dahaeans (Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: , , , ; Latin: ; Chinese language, Chinese: ; Persian language, Persian: ) were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian nomadic tribal confed ...

, but returned after becoming ill. There he met

Abu 'Ubayd al-Juzjani Abū 'Ubayd al-Jūzjānī, (d.1070), () was a Persian physician and chronicler from Guzgan.

He was the famous pupil of Avicenna, whom he first met in Gorgan.

He spent many years with his master in Isfahan, becoming his lifetime companion. After Avi ...

(died 1070) who became his pupil and companion. Avicenna stayed briefly in Gurgan, reportedly serving Qabus' son and successor

Manuchihr () and resided in the house of a patron.

In Ray and Hamadan

In , Avicenna went to the city of

Ray

Ray may refer to:

Fish

* Ray (fish), any cartilaginous fish of the superorder Batoidea

* Ray (fish fin anatomy), a bony or horny spine on a fin

Science and mathematics

* Ray (geometry), half of a line proceeding from an initial point

* Ray (g ...

, where he entered into the service of the

Buyid ''

amir'' (ruler)

Majd al-Dawla

Abu Talib Rustam ( fa, ابو طالب رستم; 997–1029), commonly known by his ''laqab'' (honorific title) of Majd al-Dawla (), was the last ''amir'' (ruler) of the Buyid amirate of Ray from 997 to 1029. He was the eldest son of Fakhr al-Daw ...

() and his mother

Sayyida Shirin

Sayyida Shirin ( fa, سیده شیرین; died 1028), also simply known as Sayyida (), was a Bavandid princess, who was the wife of the Buyid ''amir'' (ruler) Fakhr al-Dawla ().

She was the regent of most of Jibal during the minority of her so ...

, the ''de facto'' ruler of the realm. There he served as the physician at the court, treating Majd al-Dawla, who was suffering from

melancholia. Avicenna reportedly later served as the "business manager" of Sayyida Shirin in

Qazvin and

Hamadan, though details regarding this tenure are unclear. During this period, Avicenna finished his ''

Canon of Medicine'', and started writing his ''

Book of Healing

''The Book of Healing'' (; ; also known as ) is a scientific and philosophical encyclopedia written by Abu Ali ibn Sīna (aka Avicenna) from medieval Persia, near Bukhara in Maverounnahr. He most likely began to compose the book in 1014, comp ...

''.

In 1015, during Avicenna's stay in Hamadan, he participated in a public debate, as was custom for newly arrived scholars in western Iran at that time. The purpose of the debate was to examine one's reputation against a prominent local resident. The person whom Avicenna debated against was Abu'l-Qasim al-Kirmani, a member of the school of philosophers of

Baghdad. The debate became heated, resulting in Avicenna accusing Abu'l-Qasim of lack of basic knowledge in

logic, while Abu'l-Qasim accused Avicenna of impoliteness. After the debate, Avicenna sent a letter to the Baghdad Peripatetics, asking if Abu'l-Qasim's claim that he shared the same opinion as them was true. Abu'l-Qasim later retaliated by writing a letter to an unknown person, in which he made accusations so serious, that Avicenna wrote to a deputy of Majd al-Dawla, named Abu Sa'd, to investigate the matter. The accusation made towards Avicenna may have been the same as he had received earlier, in which he was accused by the people of Hamadan of copying the stylistic structures of the Quran in his ''Sermons on Divine Unity''. The seriousness of this charge, in the words of the historian Peter Adamson, "cannot be underestimated in the larger Muslim culture."

Not long afterwards, Avicenna shifted his allegiance to the rising Buyid ''amir''

Shams al-Dawla (the younger brother of Majd al-Dawla), which Adamson suggests was due to Abu'l-Qasim also working under Sayyida Shirin. Avicenna had been called upon by Shams al-Dawla to treat him, but after the latters campaign in the same year against his former ally, the

Annazid ruler Abu Shawk (), he forced Avicenna to become his

vizier. Although Avicenna would sometimes clash with Shams al-Dawla's troops, he remained vizier until the latter died of

colic in 1021. Avicenna was asked by Shams al-Dawla's son and successor

Sama' al-Dawla () to stay as vizier, but instead went into hiding with his patron Abu Ghalib al-Attar, to wait for better opportunities to emerge. It was during this period that Avicenna was secretly in contact with

Ala al-Dawla Muhammad (), the

Kakuyid ruler of

Isfahan

Isfahan ( fa, اصفهان, Esfahân ), from its Achaemenid empire, ancient designation ''Aspadana'' and, later, ''Spahan'' in Sassanian Empire, middle Persian, rendered in English as ''Ispahan'', is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Regio ...

and uncle of Sayyida Shirin.

It was during his stay at Attar's home that Avicenna completed his ''Book of Healing'', writing 50 pages a day. The Buyid court in Hamadan, particularly the

Kurdish vizier Taj al-Mulk, suspected Avicenna of correspondence with Ala al-Dawla, and as result had the house of Attar ransacked and Avicenna imprisoned in the fortress of Fardajan, outside Hamadan. Juzjani blames one of Avicenna's informers for his capture. Avicenna was imprisoned for four months, until Ala al-Dawla captured Hamadan, thus putting an end to Sama al-Dawla's reign.

In Isfahan

Avicenna was subsequently released, and went to Isfahan, where he was well received by Ala al-Dawla. In the words of Juzjani, the Kakuyid ruler gave Avicenna "the respect and esteem which someone like him deserved." Adamson also says that Avicenna's service under Ala al-Dawla "proved to be the most stable period of his life." Avicenna served as the advisor, if not vizier of Ala al-Dawla, accompanying him in many of his military expeditions and travels. Avicenna dedicated two Persian works to him, a philosophical treatise named ''

Danish-nama-yi Ala'i'' ("Book of Science for Ala"), and a medical treatise about the pulse.

During the brief occupation of Isfahan by the

Ghaznavids

The Ghaznavid dynasty ( fa, غزنویان ''Ġaznaviyān'') was a culturally Persianate, Sunni Muslim dynasty of Turkic ''mamluk'' origin, ruling, at its greatest extent, large parts of Persia, Khorasan, much of Transoxiana and the northwest ...

in January 1030, Avicenna and Ala al-Dawla relocated to the southwestern Iranian region of

Khuzistan, where they stayed until the death of the Ghaznavid ruler

Mahmud

Mahmud is a transliteration of the male Arabic given name (), common in most parts of the Islamic world. It comes from the Arabic triconsonantal root Ḥ-M-D, meaning ''praise'', along with ''Muhammad''.

Siam Mahmud

*Mahmood (singer) (born 199 ...

(), which occurred two months later. It was seemingly when Avicenna returned to Isfahan that he started writing his ''Pointers and Reminders''. In 1037, while Avicenna was accompanying Ala al-Dawla to a battle near Isfahan, he was hit by a severe colic, which he had been constantly suffering from throughout his life. He died shortly afterwards in Hamadan, where he was buried.

Philosophy

Avicenna wrote extensively on

early Islamic philosophy

Early Islamic philosophy or classical Islamic philosophy is a period of intense philosophical development beginning in the 2nd century AH of the Islamic calendar (early 9th century CE) and lasting until the 6th century AH (late 12th century CE) ...

, especially the subjects

logic,

ethics and

metaphysics, including treatises named ''Logic'' and ''Metaphysics''. Most of his works were written in

Arabic—then the language of science in the Middle East—and some in

Persian. Of linguistic significance even to this day are a few books that he wrote in nearly pure Persian language (particularly the Danishnamah-yi 'Ala', Philosophy for Ala' ad-Dawla'). Avicenna's commentaries on Aristotle often criticized the philosopher, encouraging a lively debate in the spirit of

ijtihad

''Ijtihad'' ( ; ar, اجتهاد ', ; lit. physical or mental ''effort'') is an Islamic legal term referring to independent reasoning by an expert in Islamic law, or the thorough exertion of a jurist's mental faculty in finding a solution to a le ...

.

Avicenna's

Neoplatonic scheme of "emanations" became fundamental in the ''

Kalam'' (school of theological discourse) in the 12th century.

His ''Book of Healing'' became available in Europe in partial Latin translation some fifty years after its composition, under the title ''Sufficientia'', and some authors have identified a "Latin Avicennism" as flourishing for some time, paralleling the more influential Latin

Averroism

Averroism refers to a school of medieval philosophy based on the application of the works of 12th-century Al-Andalus, Andalusian Islamic philosophy, philosopher Averroes, (known in his time in Arabic as ابن رشد, ibn Rushd, 1126–1198) a co ...

, but suppressed by the

Parisian decrees of 1210 and 1215.

Avicenna's psychology and theory of knowledge influenced

William of Auvergne, Bishop of Paris

William of Auvergne (1180/90–1249) was a French theologian and philosopher who served as Bishop of Paris from 1228 until his death. He was one of the first western European philosophers to engage with and comment extensively upon Aristotelian ...

and

Albertus Magnus,

while his metaphysics influenced the thought of

Thomas Aquinas.

Metaphysical doctrine

Early Islamic philosophy and

Islamic metaphysics, imbued as it is with

Islamic theology, distinguishes more clearly than Aristotelianism between essence and existence. Whereas existence is the domain of the contingent and the accidental, essence endures within a being beyond the accidental. The philosophy of Avicenna, particularly that part relating to metaphysics, owes much to al-Farabi. The search for a definitive Islamic philosophy separate from

Occasionalism can be seen in what is left of his work.

Following al-Farabi's lead, Avicenna initiated a full-fledged inquiry into the question of being, in which he distinguished between essence (''Mahiat'') and existence (''Wujud''). He argued that the fact of existence cannot be inferred from or accounted for by the essence of existing things, and that form and matter by themselves cannot interact and originate the movement of the universe or the progressive actualization of existing things. Existence must, therefore, be due to an

agent-cause that necessitates, imparts, gives, or adds existence to an essence. To do so, the cause must be an existing thing and coexist with its effect.

Avicenna's consideration of the essence-attributes question may be elucidated in terms of his ontological analysis of the modalities of being; namely impossibility, contingency and necessity. Avicenna argued that the impossible being is that which cannot exist, while the contingent in itself (''mumkin bi-dhatihi'') has the potentiality to be or not to be without entailing a contradiction. When actualized, the contingent becomes a 'necessary existent due to what is other than itself' (''wajib al-wujud bi-ghayrihi''). Thus, contingency-in-itself is potential beingness that could eventually be actualized by an external cause other than itself. The metaphysical structures of necessity and contingency are different. Necessary being due to itself (''wajib al-wujud bi-dhatihi'') is true in itself, while the contingent being is 'false in itself' and 'true due to something else other than itself'. The necessary is the source of its own being without borrowed existence. It is what always exists.

The Necessary exists 'due-to-Its-Self', and has no quiddity/essence (''mahiyya'') other than existence (''wujud''). Furthermore, It is 'One' (''wahid ahad'') since there cannot be more than one 'Necessary-Existent-due-to-Itself' without differentia (fasl) to distinguish them from each other. Yet, to require differentia entails that they exist 'due-to-themselves' as well as 'due to what is other than themselves'; and this is contradictory. However, if no differentia distinguishes them from each other, then there is no sense in which these 'Existents' are not one and the same.

[Nader El-Bizri, ''The Phenomenological Quest between Avicenna and Heidegger'' (Binghamton, N.Y.: Global Publications SUNY, 2000)] Avicenna adds that the 'Necessary-Existent-due-to-Itself' has no genus (''jins''), nor a definition (''hadd''), nor a counterpart (''nadd''), nor an opposite (''did''), and is detached (''bari'') from matter (''madda''), quality (''kayf''), quantity (''kam''), place (''ayn''), situation (''wad'') and time (''waqt'').

Avicenna's theology on metaphysical issues (''ilāhiyyāt'') has been criticized by some

Islamic scholars

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

, among them

al-Ghazali,

Ibn Taymiyya

Ibn Taymiyyah (January 22, 1263 – September 26, 1328; ar, ابن تيمية), birth name Taqī ad-Dīn ʾAḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm ibn ʿAbd al-Salām al-Numayrī al-Ḥarrānī ( ar, تقي الدين أحمد بن عبد الحليم � ...

and

Ibn al-Qayyim. While discussing the views of the theists among the Greek philosophers, namely

Socrates,

Plato and

Aristotle in ''Al-Munqidh min ad-Dalal'' ("Deliverance from Error"), al-Ghazali noted that the Greek philosophers "must be taxed with unbelief, as must their partisans among the Muslim philosophers, such as Avicenna and al-Farabi and their likes." He added that "None, however, of the Muslim philosophers engaged so much in transmitting Aristotle's lore as did the two men just mentioned.

..The sum of what we regard as the authentic philosophy of Aristotle, as transmitted by al-Farabi and Avicenna, can be reduced to three parts: a part which must be branded as unbelief; a part which must be stigmatized as innovation; and a part which need not be repudiated at all."

Argument for God's existence

Avicenna made an

argument

An argument is a statement or group of statements called premises intended to determine the degree of truth or acceptability of another statement called conclusion. Arguments can be studied from three main perspectives: the logical, the dialectic ...

for the

existence of God which would be known as the "

Proof of the Truthful" (

Arabic: ''burhan al-siddiqin''). Avicenna argued that there must be a "necessary existent" (Arabic: ''wajib al-wujud''), an entity that cannot ''not'' exist and through a series of arguments, he identified it with

the Islamic conception of God. Present-day

historian of philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

Peter Adamson called this argument one of the most influential medieval arguments for God's existence, and Avicenna's biggest contribution to the history of philosophy.

Al-Biruni correspondence

Correspondence between Avicenna (with his student Ahmad ibn 'Ali al-Ma'sumi) and

Al-Biruni has survived in which they debated

Aristotelian natural philosophy and the

Peripatetic school. Abu Rayhan began by asking Avicenna eighteen questions, ten of which were criticisms of Aristotle's ''

On the Heavens

''On the Heavens'' (Greek: ''Περὶ οὐρανοῦ''; Latin: ''De Caelo'' or ''De Caelo et Mundo'') is Aristotle's chief cosmological treatise: written in 350 BC, it contains his astronomical theory and his ideas on the concrete workings o ...

''.

Theology

Avicenna was a devout Muslim and sought to reconcile rational philosophy with Islamic theology. His aim was to prove the existence of God and His creation of the world scientifically and through

reason and

logic.

[Lenn Evan Goodman (2003), ''Islamic Humanism'', pp. 8–9, Oxford University Press, .] Avicenna's views on Islamic theology (and philosophy) were enormously influential, forming part of the core of the curriculum at Islamic religious schools until the 19th century. Avicenna wrote a number of short treatises dealing with Islamic theology. These included treatises on the

prophets (whom he viewed as "inspired philosophers"), and also on various scientific and philosophical interpretations of the Quran, such as how Quranic

cosmology corresponds to his own philosophical system. In general these treatises linked his philosophical writings to Islamic religious ideas; for example, the body's afterlife.

There are occasional brief hints and allusions in his longer works, however, that Avicenna considered philosophy as the only sensible way to distinguish real prophecy from illusion. He did not state this more clearly because of the political implications of such a theory, if prophecy could be questioned, and also because most of the time he was writing shorter works which concentrated on explaining his theories on philosophy and theology clearly, without digressing to consider

epistemological

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

matters which could only be properly considered by other philosophers.

Later interpretations of Avicenna's philosophy split into three different schools; those (such as

al-Tusi) who continued to apply his philosophy as a system to interpret later political events and scientific advances; those (such as

al-Razi Razi ( fa, رازی) or al-Razi ( ar, الرازی) is a name that was historically used to indicate a person coming from Ray, Iran.

People

It most commonly refers to:

* Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (865–925), influential physician, alchemist ...

) who considered Avicenna's theological works in isolation from his wider philosophical concerns; and those (such as

al-Ghazali) who selectively used parts of his philosophy to support their own attempts to gain greater spiritual insights through a variety of mystical means. It was the theological interpretation championed by those such as al-Razi which eventually came to predominate in the

madrasahs.

Avicenna

memorized the Quran by the age of ten, and as an adult, he wrote five treatises commenting on

sura

A ''surah'' (; ar, سورة, sūrah, , ), is the equivalent of "chapter" in the Qur'an. There are 114 ''surahs'' in the Quran, each divided into '' ayats'' (verses). The chapters or ''surahs'' are of unequal length; the shortest surah ('' Al-K ...

s from the Quran. One of these texts included the ''Proof of Prophecies'', in which he comments on several Quranic verses and holds the Quran in high esteem. Avicenna argued that the Islamic prophets should be considered higher than philosophers.

Avicenna is generally understood to have been aligned with the

Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

Hanafi school of thought.

Avicenna studied

Hanafi law, many of his notable teachers were

Hanafi jurists, and he served under the Hanafi court of Ali ibn Mamun.

Avicenna said at an early age that he remained "unconvinced" by Ismaili missionary attempts to convert him.

Medieval historian Ẓahīr al-dīn al-Bayhaqī (d. 1169) also believed Avicenna to be a follower of the

Brethren of Purity

The Brethren of Purity ( ar, إخوان الصفا, Ikhwān Al-Ṣafā; also The Brethren of Sincerity) were a secret society of Muslim philosophers in Basra, Iraq, in the 9th or 10th century CE.

The structure of the organization and the ide ...

.

[ excerpt: "... Dimitri Gutas's ''Avicenna's maḏhab'' convincingly demonstrates that I.S. was a sunnî-Ḥanafî]

/ref>

Thought experiments

While he was imprisoned in the castle of Fardajan near Hamadhan, Avicenna wrote his famous "floating man

Floating man is the proper translation of the verb "yahwā in al-Nafs," which means "to fall down." Flying man is another term used cohesively to describe a floating man. According to Ibn Sina, it is considered a thought experience to determine ...

"—literally falling man—a thought experiment to demonstrate human self-awareness

In philosophy of self, self-awareness is the experience of one's own personality or individuality. It is not to be confused with consciousness in the sense of qualia. While consciousness is being aware of one's environment and body and lifesty ...

and the substantiality and immateriality of the soul. Avicenna believed his "Floating Man" thought experiment demonstrated that the soul is a substance, and claimed humans cannot doubt their own consciousness, even in a situation that prevents all sensory data input. The thought experiment told its readers to imagine themselves created all at once while suspended in the air, isolated from all sensations, which includes no sensory contact with even their own bodies. He argued that, in this scenario, one would still have self-consciousness. Because it is conceivable that a person, suspended in air while cut off from sense experience

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences an ...

, would still be capable of determining his own existence, the thought experiment points to the conclusions that the soul is a perfection, independent of the body, and an immaterial substance. The conceivability of this "Floating Man" indicates that the soul is perceived intellectually, which entails the soul's separateness from the body. Avicenna referred to the living human intelligence, particularly the active intellect, which he believed to be the hypostasis

Hypostasis, hypostatic, or hypostatization (hypostatisation; from the Ancient Greek , "under state") may refer to:

* Hypostasis (philosophy and religion), the essence or underlying reality

** Hypostasis (linguistics), personification of entities

...

by which God communicates truth to the human mind and imparts order and intelligibility to nature. Following is an English translation of the argument:

However, Avicenna posited the brain as the place where reason interacts with sensation. Sensation prepares the soul to receive rational concepts from the universal Agent Intellect. The first knowledge of the flying person would be "I am," affirming his or her essence. That essence could not be the body, obviously, as the flying person has no sensation. Thus, the knowledge that "I am" is the core of a human being: the soul exists and is self-aware. Avicenna thus concluded that the idea of the self is not logically dependent on any physical thing, and that the soul should not be seen in relative terms, but as a primary given, a substance

Substance may refer to:

* Matter, anything that has mass and takes up space

Chemistry

* Chemical substance, a material with a definite chemical composition

* Drug substance

** Substance abuse, drug-related healthcare and social policy diagnosis ...

. The body is unnecessary; in relation to it, the soul is its perfection.

Principal works

''The Canon of Medicine''

Avicenna authored a five-volume medical encyclopedia: ''The Canon of Medicine'' (''Al-Qanun fi't-Tibb''). It was used as the standard medical textbook in the Islamic world and Europe up to the 18th century.

Avicenna authored a five-volume medical encyclopedia: ''The Canon of Medicine'' (''Al-Qanun fi't-Tibb''). It was used as the standard medical textbook in the Islamic world and Europe up to the 18th century.

''Liber Primus Naturalium''

Avicenna considered whether events like rare diseases or disorders have natural causes. He used the example of polydactyly to explain his perception that causal reasons exist for all medical events. This view of medical phenomena anticipated developments in the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

by seven centuries.

''The Book of Healing''

Earth sciences

Avicenna wrote on Earth science

Earth science or geoscience includes all fields of natural science related to the planet Earth. This is a branch of science dealing with the physical, chemical, and biological complex constitutions and synergistic linkages of Earth's four spheres ...

s such as geology in ''The Book of Healing''.Stephen Toulmin

Stephen Edelston Toulmin (; 25 March 1922 – 4 December 2009) was a British philosopher, author, and educator. Influenced by Ludwig Wittgenstein, Toulmin devoted his works to the analysis of moral reasoning. Throughout his writings, he sought t ...

and June Goodfield

June Goodfield is a British historian, scientist, and writer of both fiction and non-fiction.

Biography

Born Gwyneth June Goodfield in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1927, she read zoology at the University of London and undertook a PhD in history and ...

(1965), ''The Ancestry of Science: The Discovery of Time'', p. 64, University of Chicago Press (cf

The Contribution of Ibn Sina to the development of Earth sciences

)

Philosophy of science

In the ''Al-Burhan'' (''On Demonstration'') section of ''The Book of Healing'', Avicenna discussed the philosophy of science and described an early scientific method of inquiry

An inquiry (also spelled as enquiry in British English) is any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem. A theory of inquiry is an account of the various types of inquiry and a treatment of the ...

. He discussed Aristotle's ''Posterior Analytics

The ''Posterior Analytics'' ( grc-gre, Ἀναλυτικὰ Ὕστερα; la, Analytica Posteriora) is a text from Aristotle's ''Organon'' that deals with demonstration, definition, and scientific knowledge. The demonstration is distinguished ...

'' and significantly diverged from it on several points. Avicenna discussed the issue of a proper methodology for scientific inquiry and the question of "How does one acquire the first principles of a science?" He asked how a scientist would arrive at "the initial axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or f ...

s or hypotheses

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on previous obser ...

of a deductive science without inferring them from some more basic premises?" He explained that the ideal situation is when one grasps that a "relation holds between the terms, which would allow for absolute, universal certainty". Avicenna then added two further methods for arriving at the first principles: the ancient Aristotelian method of induction

Induction, Inducible or Inductive may refer to:

Biology and medicine

* Labor induction (birth/pregnancy)

* Induction chemotherapy, in medicine

* Induced stem cells, stem cells derived from somatic, reproductive, pluripotent or other cell t ...

(''istiqra''), and the method of examination and experimentation (''tajriba''). Avicenna criticized Aristotelian induction, arguing that "it does not lead to the absolute, universal, and certain premises that it purports to provide." In its place, he developed a "method of experimentation as a means for scientific inquiry."

Logic

An early formal system of temporal logic In logic, temporal logic is any system of rules and symbolism for representing, and reasoning about, propositions qualified in terms of time (for example, "I am ''always'' hungry", "I will ''eventually'' be hungry", or "I will be hungry ''until'' I ...

was studied by Avicenna. Although he did not develop a real theory of temporal propositions, he did study the relationship between ''temporalis'' and the implication. Avicenna's work was further developed by Najm al-Dīn al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī Najm al-Dīn 'Alī ibn 'Umar al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī (died AH 675 / 1276 CE) was a Persian Islamic philosopher and logician of the Shafi`i school. A student of Athīr al-Dīn al-Abharī. His most important works are a treatise on logic, ''Al-Risa ...

and became the dominant system of Islamic logic

Early Islamic law placed importance on formulating standards of argument, which gave rise to a "novel approach to logic" ( ''manṭiq'' "speech, eloquence") in Kalam (Islamic scholasticism).

However, with the rise of the Mu'tazili philosophers, wh ...

until modern times. Avicennian logic also influenced several early European logicians such as Albertus Magnus and William of Ockham. Avicenna endorsed the law of non-contradiction proposed by Aristotle, that a fact could not be both true and false at the same time and in the same sense of the terminology used. He stated, "Anyone who denies the law of non-contradiction should be beaten and burned until he admits that to be beaten is not the same as not to be beaten, and to be burned is not the same as not to be burned."

Physics

In mechanics, Avicenna, in ''The Book of Healing'', developed a theory of motion, in which he made a distinction between the inclination (tendency to motion) and force

In physics, a force is an influence that can change the motion of an object. A force can cause an object with mass to change its velocity (e.g. moving from a state of rest), i.e., to accelerate. Force can also be described intuitively as a p ...

of a projectile

A projectile is an object that is propelled by the application of an external force and then moves freely under the influence of gravity and air resistance. Although any objects in motion through space are projectiles, they are commonly found in ...

, and concluded that motion was a result of an inclination (''mayl'') transferred to the projectile by the thrower, and that projectile motion in a vacuum would not cease.[Fernando Espinoza (2005). "An analysis of the historical development of ideas about motion and its implications for teaching", ''Physics Education'' 40 (2), p. 141.] He viewed inclination as a permanent force whose effect is dissipated by external forces such as air resistance.

The theory of motion presented by Avicenna was probably influenced by the 6th-century Alexandrian scholar John Philoponus. Avicenna's is a less sophisticated variant of the theory of impetus developed by Buridan in the 14th century. It is unclear if Buridan was influenced by Avicenna, or by Philoponus directly.

In optics, Avicenna was among those who argued that light had a speed, observing that "if the perception of light is due to the emission of some sort of particles by a luminous source, the speed of light must be finite." He also provided a wrong explanation of the rainbow phenomenon. Carl Benjamin Boyer described Avicenna's ("Ibn Sīnā") theory on the rainbow as follows:

In 1253, a Latin text entitled ''Speculum Tripartitum'' stated the following regarding Avicenna's theory on heat:

Psychology

Avicenna's legacy in classical psychology is primarily embodied in the ''Kitab al-nafs'' parts of his ''Kitab al-shifa'' (''The Book of Healing'') and ''Kitab al-najat'' (''The Book of Deliverance''). These were known in Latin under the title De Anima (treatises "on the soul"). Notably, Avicenna develops what is called the Flying Man argument in the Psychology of ''The Cure'' I.1.7 as defence of the argument that the soul is without quantitative extension, which has an affinity with Descartes's ''cogito'' argument (or what phenomenology

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (philosophy), a branch of philosophy which studies subjective experiences and a ...

designates as a form of an "''epoche''").[ Nader El-Bizri, ''The Phenomenological Quest between Avicenna and Heidegger'' (Binghamton, NY: Global Publications SUNY, 2000), pp. 149–171.][Nader El-Bizri, "Avicenna's De Anima between Aristotle and Husserl," in ''The Passions of the Soul in the Metamorphosis of Becoming'', ed. Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003), pp. 67–89.]

Avicenna's psychology requires that connection between the body and soul be strong enough to ensure the soul's individuation, but weak enough to allow for its immortality. Avicenna grounds his psychology on physiology, which means his account of the soul is one that deals almost entirely with the natural science of the body and its abilities of perception. Thus, the philosopher's connection between the soul and body is explained almost entirely by his understanding of perception; in this way, bodily perception interrelates with the immaterial human intellect. In sense perception, the perceiver senses the form of the object; first, by perceiving features of the object by our external senses. This sensory information is supplied to the internal senses, which merge all the pieces into a whole, unified conscious experience. This process of perception and abstraction is the nexus of the soul and body, for the material body may only perceive material objects, while the immaterial soul may only receive the immaterial, universal forms. The way the soul and body interact in the final abstraction of the universal from the concrete particular is the key to their relationship and interaction, which takes place in the physical body.

The soul completes the action of intellection by accepting forms that have been abstracted from matter. This process requires a concrete particular (material) to be abstracted into the universal intelligible (immaterial). The material and immaterial interact through the Active Intellect, which is a "divine light" containing the intelligible forms. The Active Intellect reveals the universals concealed in material objects much like the sun makes colour available to our eyes.

Other contributions

Astronomy and astrology

Avicenna wrote an attack on astrology titled ''Resāla fī ebṭāl aḥkām al-nojūm'', in which he cited passages from the Quran to dispute the power of astrology to foretell the future. He believed that each planet had some influence on the earth, but argued against astrologers being able to determine the exact effects.

Avicenna's astronomical writings had some influence on later writers, although in general his work could be considered less developed than

Avicenna wrote an attack on astrology titled ''Resāla fī ebṭāl aḥkām al-nojūm'', in which he cited passages from the Quran to dispute the power of astrology to foretell the future. He believed that each planet had some influence on the earth, but argued against astrologers being able to determine the exact effects.

Avicenna's astronomical writings had some influence on later writers, although in general his work could be considered less developed than Alhazen

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the prin ...

or Al-Biruni. One important feature of his writing is that he considers mathematical astronomy as a separate discipline to astrology.star

A star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by its gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked ...

s receiving their light from the Sun, stating that the stars are self-luminous, and believed that the planets are also self-luminous. He claimed to have observed Venus as a spot on the Sun. This is possible, as there was a transit on 24 May 1032, but Avicenna did not give the date of his observation, and modern scholars have questioned whether he could have observed the transit from his location at that time; he may have mistaken a sunspot for Venus. He used his transit observation to help establish that Venus was, at least sometimes, below the Sun in Ptolemaic cosmology,Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it canoni ...

''), with an appended treatise "to bring that which is stated in the Almagest and what is understood from Natural Science into conformity". For example, Avicenna considers the motion of the solar apogee, which Ptolemy had taken to be fixed.

Chemistry

Avicenna was first to derive the attar of flowers from distillation and used steam distillation

Steam distillation is a separation process that consists in distilling water together with other volatile and non-volatile components. The steam from the boiling water carries the vapor of the volatiles to a condenser; both are cooled and ret ...

to produce essential oils such as rose essence, which he used as aromatherapeutic

Aromatherapy is based on the usage of aromatic materials including essential oils and other aroma compounds, with claims for improving psychological and physical well-being. It is offered as a complementary therapy or as a form of alternative ...

treatments for heart conditions.[Marlene Ericksen (2000). ''Healing with Aromatherapy'', p. 9. McGraw-Hill Professional. .]

Unlike al-Razi, Avicenna explicitly disputed the theory of the transmutation of substances commonly believed by alchemists:

Four works on alchemy attributed to Avicenna were translated into Latin as:[Georges C. Anawati (1996), "Arabic alchemy", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., '' Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science'', Vol. 3, pp. 853–885 75 Routledge, London and New York.]

*

*

*

*

was the most influential, having influenced later medieval chemists and alchemists such as Vincent of Beauvais. However, Anawati argues (following Ruska) that the de Anima is a fake by a Spanish author. Similarly the Declaratio is believed not to be actually by Avicenna. The third work (''The Book of Minerals'') is agreed to be Avicenna's writing, adapted from the ''Kitab al-Shifa'' (''Book of the Remedy'').

Poetry

Almost half of Avicenna's works are versified. His poems appear in both Arabic and Persian. As an example, Edward Granville Browne claims that the following Persian verses are incorrectly attributed to Omar Khayyám

Ghiyāth al-Dīn Abū al-Fatḥ ʿUmar ibn Ibrāhīm Nīsābūrī (18 May 1048 – 4 December 1131), commonly known as Omar Khayyam ( fa, عمر خیّام), was a polymath, known for his contributions to mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, an ...

, and were originally written by Ibn Sīnā:

Legacy

Classical Islamic civilization

Robert Wisnovsky, a scholar of Avicenna attached to McGill University, says that "Avicenna was the central figure in the long history of the rational sciences in Islam, particularly in the fields of metaphysics, logic and medicine" but that his works didn't only have an influence in these "secular" fields of knowledge alone, as "these works, or portions of them, were read, taught, copied, commented upon, quoted, paraphrased and cited by thousands of post-Avicennian scholars—not only philosophers, logicians, physicians and specialists in the mathematical or exact sciences, but also by those who specialized in the disciplines of ʿilm al-kalām (rational theology, but understood to include natural philosophy, epistemology and philosophy of mind) and usūl al-fiqh (jurisprudence, but understood to include philosophy of law, dialectic, and philosophy of language)."

Middle Ages and Renaissance

As early as the 14th century when Dante Alighieri depicted him in Limbo alongside the virtuous non-Christian thinkers in his '' Divine Comedy'' such as Virgil, Averroes, Homer,

As early as the 14th century when Dante Alighieri depicted him in Limbo alongside the virtuous non-Christian thinkers in his '' Divine Comedy'' such as Virgil, Averroes, Homer, Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

, Ovid, Lucan

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus (3 November 39 AD – 30 April 65 AD), better known in English as Lucan (), was a Roman poet, born in Corduba (modern-day Córdoba), in Hispania Baetica. He is regarded as one of the outstanding figures of the Imperial ...

, Socrates, Plato and Saladin. Avicenna has been recognized by both East and West as one of the great figures in intellectual history. Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

cites Avicenna's opinion when discussing the causes of planetary motions in Chapter 2 of '' Astronomia Nova''.

[, Johannes Kepler, ''New Astronomy,'' translated by William H. Donahue, Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1992. ]

George Sarton, the author of ''The History of Science'', described Avicenna as "one of the greatest thinkers and medical scholars in history"[ George Sarton, ''Introduction to the History of Science''.]

( cf. Dr. A. Zahoor and Dr. Z. Haq (1997)

Quotations From Famous Historians of Science

Cyberistan.) and called him "the most famous scientist of Islam and one of the most famous of all races, places, and times". He was one of the Islamic world's leading writers in the field of medicine.

Along with Rhazes, Abulcasis, Ibn al-Nafis and al-Ibadi, Avicenna is considered an important compiler of early Muslim medicine. He is remembered in the Western history of medicine as a major historical figure who made important contributions to medicine and the European Renaissance. His medical texts were unusual in that where controversy existed between Galen and Aristotle's views on medical matters (such as anatomy), he preferred to side with Aristotle, where necessary updating Aristotle's position to take into account post-Aristotelian advances in anatomical knowledge. Aristotle's dominant intellectual influence among medieval European scholars meant that Avicenna's linking of Galen's medical writings with Aristotle's philosophical writings in the ''Canon of Medicine'' (along with its comprehensive and logical organisation of knowledge) significantly increased Avicenna's importance in medieval Europe in comparison to other Islamic writers on medicine. His influence following translation of the ''Canon'' was such that from the early fourteenth to the mid-sixteenth centuries he was ranked with Hippocrates and Galen as one of the acknowledged authorities, ("prince of physicians").

Modern reception

In present-day Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan, he is considered a national icon, and is often regarded as among the greatest Persians. A monument was erected outside the Bukhara museum. The

In present-day Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan, he is considered a national icon, and is often regarded as among the greatest Persians. A monument was erected outside the Bukhara museum. The Avicenna Mausoleum and Museum

The Mausoleum of Avicenna (Persian: آرامگاه بوعلی سینا) is a monumental complex located at Avicenna Square, Hamadan, Iran.

Dedicated to the Persian polymath Avicenna, the complex includes a library, a small museum, and a spind ...

in Hamadan was built in 1952. Bu-Ali Sina University

Buali Sina University, also written Bu-Ali Sina University ( fa, دانشگاه بوعلی سينا, ''Danushgah-e Bu'li Sina''), or simply BASU, is a public university in the city of Hamedan in the Hamedan province of Iran. The university was e ...

in Hamadan (Iran), the biotechnology Avicenna Research Institute

Avicenna Research Institute (ARI; fa, پژوهشگاه ابن سینا) ) – affiliated to ACECR – was established in Tehran in order to achieve the latest medical technologies through conducting clinical and laboratory research projects in ...

in Tehran (Iran), the ''ibn Sīnā'' Tajik State Medical University in Dushanbe, Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences at Aligarh, India, Avicenna School in Karachi and Avicenna Medical College

Avicenna Medical College ( ur, , abbreviated as AMC), established in 2009, is a private college of medicine located on Bedian Road, DHA, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. It is registered with PMDC, listed in WHO Avicenna Directories and IMED The Inte ...

in Lahore, Pakistan, Ibn Sina Balkh Medical School in his native province of Balkh

), named for its green-tiled ''Gonbad'' ( prs, گُنبَد, dome), in July 2001

, pushpin_map=Afghanistan#Bactria#West Asia

, pushpin_relief=yes

, pushpin_label_position=bottom

, pushpin_mapsize=300

, pushpin_map_caption=Location in Afghanistan ...

in Afghanistan, Ibni Sina Faculty Of Medicine of Ankara University Ankara, Turkey, the main classroom building (the Avicenna Building) of the Sharif University of Technology

Sharif University of Technology (SUT; fa, دانشگاه صنعتی شریف) is a public research university in Tehran, Iran. It is widely considered as the nation's most prestigious and leading institution for science, technology, engineering, ...

, and Ibn Sina Integrated School in Marawi City (Philippines) are all named in his honour. His portrait hangs in the Hall of the Avicenna Faculty of Medicine in the University of Paris. There is a crater on the Moon named Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

and a mangrove genus.

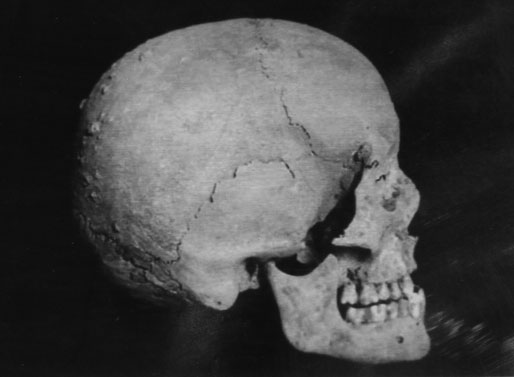

In 1980, the Soviet Union, which then ruled his birthplace Bukhara, celebrated the thousandth anniversary of Avicenna's birth by circulating various commemorative stamps with artistic illustrations, and by erecting a bust of Avicenna based on anthropological research by Soviet scholars. Near his birthplace in Qishlak Afshona, some north of Bukhara, a training college for medical staff has been named for him. On the grounds is a museum dedicated to his life, times and work. The

The Avicenna Prize

The Avicenna Prize for Ethics in Science is awarded every two years by UNESCO and rewards individuals and groups in the field of ethics in science.

The aim of the award is to promote ethical reflection on issues raised by advances in science an ...

, established in 2003, is awarded every two years by UNESCO and rewards individuals and groups for their achievements in the field of ethics in science. The aim of the award is to promote ethical reflection on issues raised by advances in science and technology, and to raise global awareness of the importance of ethics in science.

The Avicenna Directories (2008–15; now the World Directory of Medical Schools) list universities and schools where doctors, public health practitioners, pharmacists and others, are educated. The original project team stated "Why Avicenna? Avicenna ... was ... noted for his synthesis of knowledge from both east and west. He has had a lasting influence on the development of medicine and health sciences. The use of Avicenna's name symbolises the worldwide partnership that is needed for the promotion of health services of high quality."

In June 2009, Iran donated a " Persian Scholars Pavilion" to United Nations Office in Vienna which is placed in the central Memorial Plaza of the

The Avicenna Directories (2008–15; now the World Directory of Medical Schools) list universities and schools where doctors, public health practitioners, pharmacists and others, are educated. The original project team stated "Why Avicenna? Avicenna ... was ... noted for his synthesis of knowledge from both east and west. He has had a lasting influence on the development of medicine and health sciences. The use of Avicenna's name symbolises the worldwide partnership that is needed for the promotion of health services of high quality."

In June 2009, Iran donated a " Persian Scholars Pavilion" to United Nations Office in Vienna which is placed in the central Memorial Plaza of the Vienna International Center

The Vienna International Centre (VIC) is the campus and building complex hosting the United Nations Office at Vienna (UNOV; in de-AT, Büro der Vereinten Nationen in Wien). It is colloquially also known as UNO City.

Overview

The VIC, designed ...

. The "Persian Scholars Pavilion" at United Nations in Vienna, Austria is featuring the statues of four prominent Iranian figures. Highlighting the Iranian architectural features, the pavilion is adorned with Persian art forms and includes the statues of renowned Iranian scientists Avicenna, Al-Biruni, Zakariya Razi (Rhazes) and Omar Khayyam.

The 1982 Soviet film ''Youth of Genius'' (russian: Юность гения, Yunost geniya, links=no) by recounts Avicenna's younger years. The film is set in Bukhara at the turn of the millennium.

In Louis L'Amour's 1985 historical novel ''The Walking Drum

''The Walking Drum'' is a novel by the American author Louis L'Amour. Unlike most of his other novels, ''The Walking Drum'' is not set in the frontier era of the American West, but rather is an historical novel set in the Middle Ages—12th-ce ...

'', Kerbouchard studies and discusses Avicenna's ''The Canon of Medicine''.

In his book ''The Physician

''The Physician'' is a novel by Noah Gordon (novelist), Noah Gordon. It is about the life of a Christians, Christian English boy in the 11th century who journeys across Europe in order to study medicine among the Persian people, Persians.

The b ...

'' (1988) Noah Gordon tells the story of a young English medical apprentice who disguises himself as a Jew to travel from England to Persia and learn from Avicenna, the great master of his time. The novel was adapted into a feature film, ''The Physician

''The Physician'' is a novel by Noah Gordon (novelist), Noah Gordon. It is about the life of a Christians, Christian English boy in the 11th century who journeys across Europe in order to study medicine among the Persian people, Persians.

The b ...

'', in 2013. Avicenna was played by Ben Kingsley.

List of works

The treatises of Avicenna influenced later Muslim thinkers in many areas including theology, philology, mathematics, astronomy, physics and music. His works numbered almost 450 volumes on a wide range of subjects, of which around 240 have survived. In particular, 150 volumes of his surviving works concentrate on philosophy and 40 of them concentrate on medicine.Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second- ...

and elsewhere; part of it on the ''De Anima'' appeared at Pavia (1490) as the ''Liber Sextus Naturalium'', and the long account of Avicenna's philosophy given by Muhammad al-Shahrastani

Tāj al-Dīn Abū al-Fath Muhammad ibn `Abd al-Karīm ash-Shahrastānī ( ar, تاج الدين أبو الفتح محمد بن عبد الكريم الشهرستاني; 1086–1153 CE), also known as Muhammad al-Shahrastānī, was an influenti ...

seems to be mainly an analysis, and in many places a reproduction, of the Al-Shifa'. A shorter form of the work is known as the An-najat (''Liberatio''). The Latin editions of part of these works have been modified by the corrections which the monastic editors confess that they applied. There is also a (''hikmat-al-mashriqqiyya'', in Latin ''Philosophia Orientalis''), mentioned by Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; la, Rogerus or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through empiri ...

, the majority of which is lost in antiquity, which according to Averroes was pantheistic in tone.Al-isharat wa al-tanbihat

''Al-Isharat wa’l-tanbihat'' ( ar, الإشارات والتنبيهات, "The Book of Directives and Remarks") is apparently one of the last books of Avicenna which is written in Arabic.

Author

Avicenna was born in Afsanah at 980, a village ...

'' (''Remarks and Admonitions''), ed. S. Dunya, Cairo, 1960; parts translated by S.C. Inati, Remarks and Admonitions, Part One: Logic, Toronto, Ont.: Pontifical Institute for Mediaeval Studies, 1984, and Ibn Sina and Mysticism, Remarks and Admonitions: Part 4, London: Kegan Paul International, 1996.The Book of Healing

''The Book of Healing'' (; ; also known as ) is a scientific and philosophical encyclopedia written by Abu Ali ibn Sīna (aka Avicenna) from medieval Persia, near Bukhara in Maverounnahr. He most likely began to compose the book in 1014, comp ...

''). (Avicenna's major work on philosophy. He probably began to compose al-Shifa' in 1014, and completed it in 1020.) Critical editions of the Arabic text have been published in Cairo, 1952–83, originally under the supervision of I. Madkour.Risala fi'l-Ishq

or or , also spelled //, plural , is an Arabic word () meaning "letter", "epistle", "treatise", or "message".

It may refer to:

Literary genre

*, a summary of religious prescriptions in Islamic jurisprudence

*, treatise composed during the mo ...

'' (

A Treatise on Love

'). Translated by Emil L. Fackenheim.

Persian works

Avicenna's most important Persian work is the '' Danishnama-i 'Alai'' (, "the Book of Knowledge for rince'Ala ad-Daulah"). Avicenna created new scientific vocabulary that had not previously existed in Persian. The Danishnama covers such topics as logic, metaphysics, music theory and other sciences of his time. It has been translated into English by Parwiz Morewedge in 1977. The book is also important in respect to Persian scientific works.

''Andar Danesh-e Rag'' (, "On the Science of the Pulse") contains nine chapters on the science of the pulse and is a condensed synopsis.

Persian poetry

Persian literature ( fa, ادبیات فارسی, Adabiyâte fârsi, ) comprises oral compositions and written texts in the Persian language and is one of the world's oldest literatures. It spans over two-and-a-half millennia. Its sources h ...

from Avicenna is recorded in various manuscripts and later anthologies such as ''Nozhat al-Majales

''Noz'hat al-Majāles'' ( fa, نزهة المجالس "Joy of the Gatherings/Assemblies") is an anthology which contains around 4,100 Persian quatrains by some 300 poets of the 5th to 7th centuries AH (11th to 13th centuries AD). The anthology was ...

''.

See also

* Al-Qumri (possibly Avicenna's teacher)

* Abdol Hamid Khosro Shahi

Abdul Hamid Khosroshahi (Persian: عبدالحمید خسروشاهی) was an Iranian theologian, philosopher and Shafi'i jurist in the sixth and seventh centuries AH, equivalent to 12th and 13th centuries AD. He is called one of the disciples of ...

(Iranian theologian)

* Mummia

Mummia, mumia, or originally mummy referred to several different preparations in the history of medicine, from "mineral pitch (resin), pitch" to "powdered human mummies". It originated from Arabic ''mūmiyā'' "a type of resinous bitumen found ...

(Persian medicine)

* Eastern philosophy

Eastern philosophy or Asian philosophy includes the various philosophies that originated in East and South Asia, including Chinese philosophy, Japanese philosophy, Korean philosophy, and Vietnamese philosophy; which are dominant in East Asia, ...

* Iranian philosophy

* Islamic philosophy

* Contemporary Islamic philosophy

* Science in the medieval Islamic world

* List of scientists in medieval Islamic world

* Sufi philosophy

* Science and technology in Iran

* Ancient Iranian medicine

* List of pre-modern Iranian scientists and scholars

Namesakes of Ibn Sina

* Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences in Aligarh

* Avicenna Bay

Avicenna Bay is a small bay lying southwest of D'Ursel Point along the east side of Brabant Island, in the Palmer Archipelago. It was roughly charted by the Belgian Antarctic Expedition under Adrien de Gerlache, 1897–99, photographed by ...

in Antarctica

* Avicenna (crater)

Avicenna is a Lunar craters, lunar impact crater that lies on the Far side (Moon), far side of the Moon, just beyond the western limb on the northern rim of the Lorentz (crater), Lorentz basin. It is named after the Persian people, Persian poly ...

on the far side of the Moon

* Avicenna Cultural and Scientific Foundation

Avicenna Scientific and Cultural Foundation (, ) is a non-profit non-governmental institution whose focus is on the life and works of the Persian polymath Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Al-Hasan ibn Ali ibn Sīnā ( Avicenna or Ibn ...

* Avicenne Hospital

Avicenne Hospital (french: Hôpital Avicenne) is an Islamic hospital in Bobigny, Seine-Saint-Denis, in the northern suburbs of Paris. Opened in 1935 as the Franco-Muslim Hospital (''Hôpital franco-musulman de Paris''), it was built specifically t ...

in Paris, France

* Avicenna International College

Avicenna International College – AIC – (Hungarian: Avicenna Nemzetközi Kollégium) was founded in 1995 by Dr. Shahrokh Mirza Hosseini and has been in operation as a preparatory college for higher education since 2000. The college offers foun ...

in Budapest, Hungary

* Avicenna Mausoleum

The Mausoleum of Avicenna (Persian: آرامگاه بوعلی سینا) is a monumental complex located at Avicenna Square, Hamadan, Iran.

Dedicated to the Persian polymath Avicenna, the complex includes a library, a small museum, and a spindl ...

(complex dedicated to Avicenna) in Hamadan, Iran

* Avicenna Research Institute

Avicenna Research Institute (ARI; fa, پژوهشگاه ابن سینا) ) – affiliated to ACECR – was established in Tehran in order to achieve the latest medical technologies through conducting clinical and laboratory research projects in ...

in Tehran, Iran

* Avicenna Tajik State Medical University

Avicenna Tajik State Medical University (; russian: Таджикский государственный медицинский университет) or ATSMU is a public university in Tajikistan. Established in 1939, it is located in Dushanbe ...

in Dushanbe, Tajikistan

* Bu-Ali Sina University

Buali Sina University, also written Bu-Ali Sina University ( fa, دانشگاه بوعلی سينا, ''Danushgah-e Bu'li Sina''), or simply BASU, is a public university in the city of Hamedan in the Hamedan province of Iran. The university was e ...

in Hamedan, Iran

* Ibn Sina Peak

Lenin Peak or Ibn Sina (Avicenna) Peak ( ky, Ленин Чокусу, ''Lenin Choqusu'', لەنىن چوقۇسۇ; russian: Пик Ленина, ''Pik Lenina''; tg, қуллаи Ленин , ''qulla‘i Lenin/qullaji Lenin'', renamed қулла� ...

– named after the Scientist, on the Kyrgyzstan– Tajikistan border

* Ibn Sina Foundation in Houston, Texas

* Ibn Sina Hospital

Ibn Sina Hospital is a hospital in Baghdad, Iraq which was opened by four Iraqi doctors – Modafar Al Shather, Kadim Shubar, Kasim Abdul Majeed and Clement Serkis – in 1964. It was purchased for a fraction of its true value by the Iraqi governm ...

, Baghdad, Iraq

* Ibn Sina Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey

* Ibn Sina Medical College

Ibn Sina Medical College (ISMC) ( bn, ইবনে সিনা মেডিকেল কলেজ) is a private medical school in Bangladesh, established in 2005. It is located in the Kallyanpur area of Mirpur Model Thana, in Dhaka. It is affili ...

Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

* Ibn Sina University Hospital of Rabat-Salé at Mohammed V University in Rabat

Rabat (, also , ; ar, الرِّبَاط, er-Ribât; ber, ⵕⵕⴱⴰⵟ, ṛṛbaṭ) is the capital city of Morocco and the country's seventh largest city with an urban population of approximately 580,000 (2014) and a metropolitan populati ...

, Morocco

* Ibne Sina Hospital, Multan, Punjab, Pakistan

References

Citations

Sources

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Further reading

Encyclopedic articles

*

*

*

*

*

*

* (PDF version)

Avicenna

entry by Sajjad H. Rizvi in the ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (''IEP'') is a scholarly online encyclopedia, dealing with philosophy, philosophical topics, and philosophers. The IEP combines open access publication with peer reviewed publication of original pape ...

''

*

Primary literature

* For an old list of other extant works, C. Brockelmann

Carl Brockelmann (17 September 1868 – 6 May 1956) German Semiticist, was the foremost orientalist of his generation. He was a professor at the universities in Breslau, Berlin and, from 1903, Königsberg. He is best known for his multi-volume ...

's ''Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur'' (Weimar 1898), vol. i. pp. 452–458. (XV. W.; G. W. T.)

* For a current list of his works see A. Bertolacci (2006) and D. Gutas (2014) in the section "Philosophy".

*

*

* Avicenne: ''Réfutation de l'astrologie''. Edition et traduction du texte arabe, introduction, notes et lexique par Yahya Michot. Préface d'Elizabeth Teissier (Beirut-Paris: Albouraq, 2006) .