Events leading to the attack on Pearl Harbor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A series of events led to the

In the 1930s, Japan's increasingly-,expansionist policies brought it into renewed conflict with its neighbors, the Soviet Union and China. The latter was in 1922 disappointed by Germany's former Chinese colony of

In the 1930s, Japan's increasingly-,expansionist policies brought it into renewed conflict with its neighbors, the Soviet Union and China. The latter was in 1922 disappointed by Germany's former Chinese colony of

Morton, Louis. Strategy and Command: The First Two Years Responding to Japanese occupation of key airfields in Indochina (July 24) after an agreement between Japan and Vichy France, the U.S. froze Japanese assets on July 26, 1941, and on August 1, it established an embargo on oil and gasoline exports to Japan. The oil embargo was an especially strong response because oil was Japan's most crucial import, and more than 80% of Japan's oil came from the United States. Japanese war planners had long looked south, especially to Brunei for oil and Malaya for rubber and tin. In the autumn of 1940, Japan requested 3.15 million barrels of oil from the Dutch East Indies but received a counteroffer of only 1.35 million. The complete U.S. oil embargo reduced the Japanese options to two: seize Southeast Asia before its existing stocks of strategic materials were depleted or submission to American demands. Moreover, any southern operation would be vulnerable to attack from the

In July 1941, IJN headquarters informed Emperor Hirohito its reserve

In July 1941, IJN headquarters informed Emperor Hirohito its reserve  On November 3, 1941, Nagano presented a complete plan for the attack on Pearl Harbor to Hirohito. At the Imperial Conference on November 5, Hirohito approved the plan for a war against the United States, Britain and the Netherlands that was scheduled to start in early December if an acceptable diplomatic settlement were not achieved before then. Over the following weeks, Tōjō's military regime offered a final deal to the United States. It offered to leave only Indochina in return for large American economic aid. On November 26, the so-called Hull Memorandum (or Hull Note) rejected the offer and stated that in addition to leaving Indochina, the Japanese must leave China and agree to an

On November 3, 1941, Nagano presented a complete plan for the attack on Pearl Harbor to Hirohito. At the Imperial Conference on November 5, Hirohito approved the plan for a war against the United States, Britain and the Netherlands that was scheduled to start in early December if an acceptable diplomatic settlement were not achieved before then. Over the following weeks, Tōjō's military regime offered a final deal to the United States. It offered to leave only Indochina in return for large American economic aid. On November 26, the so-called Hull Memorandum (or Hull Note) rejected the offer and stated that in addition to leaving Indochina, the Japanese must leave China and agree to an  On November 30, 1941,

On November 30, 1941,

In a letter dated January 7, 1941, Yamamoto finally delivered a rough outline of his plan to Koshiro Oikawa, the Navy Minister, from whom he also requested to be made commander-in-chief of the air fleet to attack Pearl Harbor. A few weeks later, in yet another letter, Yamamoto requested for Admiral Takijiro Onishi, chief of staff of the Eleventh Air Fleet, to study the technical feasibility of an attack against the American base. Onishi gathered as many facts as possible about Pearl Harbor.

After first consulting with Kosei Maeda, an expert on aerial torpedo warfare, and being told that the harbor's shallow waters rendered such an attack almost impossible, Onishi summoned Commander

In a letter dated January 7, 1941, Yamamoto finally delivered a rough outline of his plan to Koshiro Oikawa, the Navy Minister, from whom he also requested to be made commander-in-chief of the air fleet to attack Pearl Harbor. A few weeks later, in yet another letter, Yamamoto requested for Admiral Takijiro Onishi, chief of staff of the Eleventh Air Fleet, to study the technical feasibility of an attack against the American base. Onishi gathered as many facts as possible about Pearl Harbor.

After first consulting with Kosei Maeda, an expert on aerial torpedo warfare, and being told that the harbor's shallow waters rendered such an attack almost impossible, Onishi summoned Commander

On November 26, 1941, the day that the

On November 26, 1941, the day that the

In 1924, General William L. Mitchell produced a 324-page report warning that future wars, including with Japan, would include a new role for aircraft against existing ships and facilities. He even discussed the possibility of an air attack on Pearl Harbor, but his warnings were ignored. Navy Secretary Knox had also appreciated the possibility of an attack at Pearl Harbor in a written analysis shortly after he had taken office. American commanders had been warned that tests had demonstrated shallow-water aerial torpedo attacks were possible, but no one in charge in Hawaii fully appreciated that. In a 1932

In 1924, General William L. Mitchell produced a 324-page report warning that future wars, including with Japan, would include a new role for aircraft against existing ships and facilities. He even discussed the possibility of an air attack on Pearl Harbor, but his warnings were ignored. Navy Secretary Knox had also appreciated the possibility of an attack at Pearl Harbor in a written analysis shortly after he had taken office. American commanders had been warned that tests had demonstrated shallow-water aerial torpedo attacks were possible, but no one in charge in Hawaii fully appreciated that. In a 1932

/ref> that war with Japan was expected in the very near future, and it was preferred for Japan make the first hostile act.

/ref> It was felt thatvwar would most probably start with attacks in the Far East in the Philippines,

!--retrieval date?--> French Indochina,

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

. War between Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

was a possibility for which each nation's military forces had planned for after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The expansion of American territories in the Pacific had been a threat to Japan since the 1890s, but real tensions did not begin until the Japanese invasion of Manchuria

The Empire of Japan's Kwantung Army invaded Manchuria on 18 September 1931, immediately following the Mukden Incident. At the war's end in February 1932, the Japanese established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Their occupation lasted until the ...

in 1931.

Japan's fear of being colonized and the government's expansionist

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who of ...

policies led to its own imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

in Asia and the Pacific to join the great powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

, all of which were Western nations

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

. The Japanese government saw the need to be a colonial power to be modern and therefore Western. In addition, resentment was fanned in Japan by the rejection of the Japanese Racial Equality Proposal

The was an amendment to the Treaty of Versailles that was considered at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Proposed by Japan, it was never intended to have any universal implications, but one was attached to it anyway, which caused its controversy. ...

in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, as well as by a series of racist laws, which enforced segregation and barred Asian people (including Japanese) from citizenship, land ownership, and immigration to the US.

In the 1930s, Japan expanded slowly into China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, which led to the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

in 1937. In 1940, Japan invaded French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

in an effort to embargo all imports into China, including war supplies that were purchased from the US. That move prompted the US to embargo all oil exports, which led the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

(IJN) to estimate it had less than two years of bunker oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), bun ...

remaining and to support the existing plans to seize oil resources in the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

.

Planning had been underway for some time on an attack on the "Southern Resource Area" to add it to the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the Empire of Japan and propagated to Asian populations which were occupied by it from 1931 to 1945, and which officially aimed at creating a self-sufficient bloc of Asian peo ...

Japan envisioned in the Pacific.

The Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, then an American protectorate, were also a Japanese target. The Japanese military

The Japan Self-Defense Forces ( ja, 自衛隊, Jieitai; abbreviated JSDF), also informally known as the Japanese Armed Forces, are the unified ''de facto''Since Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution outlaws the formation of armed forces, th ...

concluded that an invasion of the Philippines would provoke an American military response. Rather than seize and fortify the islands and wait for the inevitable US counterattack, Japan's military leaders instead decided on the preventive attack

A preventive war is a war or a military action which is initiated in order to prevent a belligerent or a neutral country, neutral party from acquiring a Offensive (military), capability for attacking. The party which is being attacked has a laten ...

on Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

, which they assumed would negate the American forces needed for the liberation and the reconquest of the islands. (Later that day ecember 8, local time the Japanese indeed launched their invasion of the Philippines).

Planning for the attack on Pearl Harbor had begun very early in 1941 by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet during World War II until he was killed.

Yamamoto held several important posts in the IJN, and undertook many of its changes and reor ...

. He finally won assent from the Naval High Command by, among other things, threatening to resign. The attack was approved in the summer at an Imperial Conference and again at a second Conference in the autumn. Simultaneously over the year, pilots were trained, and ships prepared for its execution. Authority for the attack was granted at the second Imperial Conference if a diplomatic result satisfactory to Japan was not reached. After the Hull note

The Hull note, officially the Outline of Proposed Basis for Agreement Between the United States and Japan, was the final proposal delivered to the Empire of Japan by the United States of America before the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1 ...

and the final approval by Emperor Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

, the order to attack was issued in early December.

Background

Both the Japanese public and the political perception of American antagonism began in the 1890s. The American acquisition of Pacific colonies near Japan and its brokering of the end of theRusso-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

via the Treaty of Portsmouth

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

, which left neither belligerent, particularly Japan, satisfied, left a lasting general impression that the United States was inappropriately foisting itself into Asian regional politics and intent on limiting Japan and set the stage for later more contentious politics between the two nations.

Tensions between Japan and the prominent Western countries (the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands) increased significantly during the increasingly militaristic early reign of Emperor Hirohito. Japanese nationalists and military leaders increasingly influenced government policy and promoted a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the Empire of Japan and propagated to Asian populations which were occupied by it from 1931 to 1945, and which officially aimed at creating a self-sufficient bloc of Asian peo ...

as part of Japan's alleged " divine right" to unify Asia under Emperor Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

's rule.

In the 1930s, Japan's increasingly-,expansionist policies brought it into renewed conflict with its neighbors, the Soviet Union and China. The latter was in 1922 disappointed by Germany's former Chinese colony of

In the 1930s, Japan's increasingly-,expansionist policies brought it into renewed conflict with its neighbors, the Soviet Union and China. The latter was in 1922 disappointed by Germany's former Chinese colony of Shandong

Shandong ( , ; ; alternately romanized as Shantung) is a coastal province of the People's Republic of China and is part of the East China region.

Shandong has played a major role in Chinese history since the beginning of Chinese civilizati ...

being transferred to Japan in the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

. (Japan had fought the First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the po ...

with China in 1894–1895 and the Russo-Japanese War with Russia in 1904–1905. Japan's imperialist ambitions had a hand in precipitating both conflicts after which Japan gained a large sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

in Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manc ...

and saw an opportunity to expand its position in China.) In March 1933 Japan withdrew from the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

in response to international condemnation of its conquest of Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manc ...

and subsequent establishment of the Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Northeast China, Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 afte ...

puppet government

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sovere ...

there. On January 15, 1936, the Japanese withdrew from the Second London Naval Disarmament Conference

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds each ...

because the United States and the United Kingdom refused to grant the Japanese Navy parity with theirs. A second war between Japan and China began with the Marco Polo Bridge Incident

The Marco Polo Bridge Incident, also known as the Lugou Bridge Incident () or the July 7 Incident (), was a July 1937 battle between China's National Revolutionary Army and the Imperial Japanese Army.

Since the Japanese invasion of Manchuria ...

in July 1937.

Japan's 1937 attack on China was condemned by the U.S. and by several members of the League of Nations, including the United Kingdom, France, Australia, and the Netherlands. Japanese atrocities during the conflict, such as the notorious Nanking Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the Ba ...

that December, further complicated relations with the rest of the world. The U.S., the United Kingdom, France and the Netherlands all possessed colonies in East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fa ...

and Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

. Japan's new military power and willingness to use it threatened the Western economic and territorial interests in Asia.

In 1938, the U.S. began to adopt a succession of increasingly-restrictive trade restrictions with Japan, including terminating its 1911 commercial treaty with Japan in 1939, which was further tightened by the Export Control Act

The Export Control Act of 1940 was one in a series of legislative efforts by the US government and initially the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to accomplish two tasks: to avoid scarcity of critical commodities in a likely ...

of 1940. Those efforts failed to deter Japan from continuing its war in China or from signing the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive military ...

in 1940 with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and Fascist Italy, which officially formed the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

.

Japan would take advantage of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's war in Europe to advance its own ambitions in the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

. The Tripartite Pact guaranteed assistance if a signatory was attacked by any country not already involved in conflict with the signatory, which implicitly meant the U.S. and the Soviet Union. By joining the pact, Japan gained geopolitical power and sent the unmistakable message that any U.S. military intervention risked war on both shores: with Germany and Italy in the Atlantic and with Japan in the Pacific. The Franklin Roosevelt administration

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

would not be dissuaded. Believing that the American way of life

The American way of life or the American way refers to the American nationalist ethos that adheres to the principle of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. At the center of the American way is the belief in an American Dream that is claim ...

would be endangered if Europe and the Far East fell under fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

military dictatorship, it committed to help the British and the Chinese through loans of money and materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the specifi ...

and pledged sufficient continuing aid to ensure their survival. Thus, the United States slowly moved from being a neutral power to one preparing for war.

In mid-1940, Roosevelt moved the U.S. Pacific Fleet to Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

, Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

, to deter Japan. On October 8, 1940, Admiral James O. Richardson

James Otto Richardson (18 September 1878 – 2 May 1974) was an admiral in the United States Navy who served from 1902 to 1947.

As commander in chief of the United States Fleet (CinCUS), Richardson protested the redeployment of the Pacific portio ...

, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, provoked a confrontation with Roosevelt by repeating his earlier arguments to Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the professional head of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the secretary of the Navy. In a separate capacity as a memb ...

Admiral Harold R. Stark

Harold Rainsford Stark (November 12, 1880 – August 20, 1972) was an officer in the United States Navy during World War I and World War II, who served as the 8th Chief of Naval Operations from August 1, 1939 to March 26, 1942.

Early life a ...

and Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Frank Knox

William Franklin Knox (January 1, 1874 – April 28, 1944) was an American politician, newspaper editor and publisher. He was also the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1936, and Secretary of the Navy under Franklin D. Roosevelt during ...

that Pearl Harbor was the wrong place for his ships. Roosevelt believed relocating the fleet to Hawaii would exert a "restraining influence" on Japan.

Richardson asked Roosevelt if the United States was going to war and got this response:

At least as early as October 8, 1940,... affairs had reached such a state that the United States would become involved in a war with Japan.... 'that if the Japanese attacked Thailand, or the Kra Peninsula, or the Dutch East Indies we would not enter the war, that if they even attacked the Philippines he doubted whether we would enter the war, but that they (the Japanese) could not always avoid making mistakes and that as the war continued and that area of operations expanded sooner or later they would make a mistake and we would enter the war.'Japan's 1940 move into

Vichy

Vichy (, ; ; oc, Vichèi, link=no, ) is a city in the Allier Departments of France, department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central France, in the historic province of Bourbonnais.

It is a Spa town, spa and resort town and in World ...

-controlled French Indochina further raised tensions. Along with Japan's war with China, withdrawal from the League of Nations, alliance with Germany and Italy, and increasing militarization, the move induced the United States to intensify its measures to restrain Japan economically. The United States placed an embargo

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they m ...

on scrap-metal shipments to Japan and closed the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

to Japanese shipping. That hit Japan's economy particularly hard because 74.1% of Japan's scrap iron came from the United States in 1938, and 93% of Japan's copper in 1939 came from the United States. In early 1941 Japan moved into southern Indochina, thereby threatening British Malaya

The term "British Malaya" (; ms, Tanah Melayu British) loosely describes a set of states on the Malay Peninsula and the island of Singapore that were brought under British hegemony or control between the late 18th and the mid-20th century. U ...

, North Borneo

North Borneo (usually known as British North Borneo, also known as the State of North Borneo) was a British Protectorate, British protectorate in the northern part of the island of Borneo, which is present day Sabah. The territory of North Borneo ...

and Brunei

Brunei ( , ), formally Brunei Darussalam ( ms, Negara Brunei Darussalam, Jawi alphabet, Jawi: , ), is a country located on the north coast of the island of Borneo in Southeast Asia. Apart from its South China Sea coast, it is completely sur ...

.

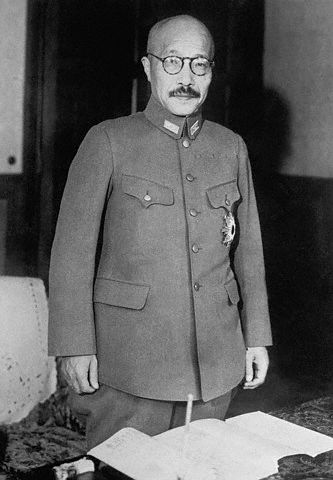

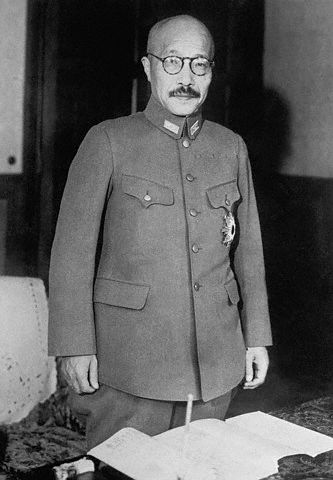

Japan and the U.S. engaged in negotiations in 1941 in an effort to improve relations. During the negotiations, Japan considered withdrawal from most of China and Indochina after it had drawn up peace terms with the Chinese. Japan would also adopt an independent interpretation of the Tripartite Pact and would not discriminate in trade if all other countries reciprocated. However, War Minister General Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

rejected compromises in China.Chapter V: The Decision for WarMorton, Louis. Strategy and Command: The First Two Years Responding to Japanese occupation of key airfields in Indochina (July 24) after an agreement between Japan and Vichy France, the U.S. froze Japanese assets on July 26, 1941, and on August 1, it established an embargo on oil and gasoline exports to Japan. The oil embargo was an especially strong response because oil was Japan's most crucial import, and more than 80% of Japan's oil came from the United States. Japanese war planners had long looked south, especially to Brunei for oil and Malaya for rubber and tin. In the autumn of 1940, Japan requested 3.15 million barrels of oil from the Dutch East Indies but received a counteroffer of only 1.35 million. The complete U.S. oil embargo reduced the Japanese options to two: seize Southeast Asia before its existing stocks of strategic materials were depleted or submission to American demands. Moreover, any southern operation would be vulnerable to attack from the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, a U.S. colony, and so war against the U.S. seemed necessary in any case.

After the embargoes and the asset freezes, the Japanese ambassador to Washington, Kichisaburō Nomura

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy and was the List of ambassadors of Japan to the United States, ambassador to the United States at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Early life and career

Nomura was born in Wakayama, Wakayama, ...

, and U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ...

held multiple meetings to resolve Japanese-American relations

are Americans of Japanese people, Japanese ancestry. Japanese Americans were among the three largest Asian Americans, Asian American ethnic communities during the 20th century; but, according to the 2000 United States census, 2000 census, they ...

. No solution could be agreed upon for three key reasons:

# Japan honored its alliance to Germany and Italy in the Tripartite Pact.

# Japan wanted economic control and responsibility for southeast Asia, as envisioned in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

The , also known as the GEACPS, was a concept that was developed in the Empire of Japan and propagated to Asian populations which were occupied by it from 1931 to 1945, and which officially aimed at creating a self-sufficient bloc of Asian peo ...

.

# Japan refused to leave Mainland China unless it kept its puppet state of Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Northeast China, Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 afte ...

.

In its final proposal on November 20, Japan offered to withdraw its forces from southern Indochina and not to launch any attacks in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

if the U.S., Britain, and the Netherlands ceased aiding China and lifted their sanctions against Japan. The American counterproposal of November 26, the Hull note

The Hull note, officially the Outline of Proposed Basis for Agreement Between the United States and Japan, was the final proposal delivered to the Empire of Japan by the United States of America before the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1 ...

, required Japan to evacuate all of China unconditionally and to conclude non-aggression pacts with Pacific powers.

Breaking off negotiations

Part of the Japanese plan for the attack included breaking off negotiations with the United States 30 minutes before the attack began. Diplomats from the Japanese embassy inWashington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, including the Japanese ambassador, Admiral Kichisaburō Nomura

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy and was the List of ambassadors of Japan to the United States, ambassador to the United States at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Early life and career

Nomura was born in Wakayama, Wakayama, ...

and Special Representative Saburō Kurusu

was a Japanese career diplomat. He is remembered now as an envoy who tried to negotiate peace and understanding with the United States while the Japanese government under Emperor Shōwa was secretly preparing the attack on Pearl Harbor.

As Imp ...

, had been conducting extended talks with the U.S. State Department regarding reactions to the Japanese move into French Indochina in the summer.

In the days before the attack, a long 14-part message was sent to the embassy from the Foreign Office in Tokyo that was encrypted with the Type 97 cypher machine, in a cipher named PURPLE

Purple is any of a variety of colors with hue between red and blue. In the RGB color model used in computer and television screens, purples are produced by mixing red and blue light. In the RYB color model historically used by painters, pu ...

. It was decoded by U.S. cryptanalysts

Cryptanalysis (from the Greek ''kryptós'', "hidden", and ''analýein'', "to analyze") refers to the process of analyzing information systems in order to understand hidden aspects of the systems. Cryptanalysis is used to breach cryptographic s ...

) and had instructions to deliver it to Secretary of State Cordell Hull at . The last part arrived late Saturday night (Washington RlTime), but because of decryption and typing delays, as well as Tokyo's failure to stress the crucial necessity of the timing, embassy personnel did not deliver the message to Hull until several hours after the attack.

The United States had decrypted the 14th part well before the Japanese did so, and long before, embassy staff had composed a clean typed copy. The final part, with its instruction for the time of delivery, had been decoded Saturday night but was not acted upon until the next morning, according to Henry Clausen

Henry Christian Clausen (30 June 1905 – 4 December 1992) was an American lawyer, and investigator. He authored the ''Clausen Report'', an 800-page report on the Army Board's Pearl Harbor Investigation. He traveled over 55,000 miles over seven ...

.

Nomura asked for an appointment to see Hull at but later asked it be postponed to 1:45 as Nomura was not quite ready. Nomura and Kurusu arrived at and were received by Hull at 2:20. Nomura apologized for the delay in presenting the message. After Hull had read several pages, he asked Nomura whether the document was presented under instructions of the Japanese government. Nomura replied that it was. After reading the full document, Hull turned to the ambassador and said:

I must say that in all my conversations with you... during the last nine months I have never uttered one word of untruth. This is borne out absolutely by the record. In all my fifty years of public service I have never seen a document that was more crowded with infamous falsehoods and distortions--infamous falsehoods and distortions on a scale so huge that I never imagined until today that any Government on this planet was capable of uttering them.Japanese records, which were admitted into evidence during congressional hearings on the attack after the war, established that Japan had not even written a declaration of war until it had news of the successful attack. The two-line declaration was finally delivered to U.S. Ambassador

Joseph Grew

Joseph Clark Grew (May 27, 1880 – May 25, 1965) was an American career diplomat and U.S. Foreign Service, Foreign Service officer. He is best known as the ambassador to Japan from 1932 to 1941 and as a high official in the State Department in W ...

in Tokyo about ten hours after the completion of the attack. Grew was allowed to transmit it to the United States, where it was received late Monday afternoon (Washington time).

War

In July 1941, IJN headquarters informed Emperor Hirohito its reserve

In July 1941, IJN headquarters informed Emperor Hirohito its reserve bunker oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), bun ...

would be exhausted within two years if a new source was not found. In August 1941, Japanese Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe

Prince was a Japanese politician and prime minister. During his tenure, he presided over the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 and the breakdown in relations with the United States, which ultimately culminated in Japan's entry into World W ...

proposed a summit with Roosevelt to discuss differences. Roosevelt replied that Japan must leave China before a summit meeting could be held. On September 6, 1941, at the second Imperial Conference concerning attacks on the Western colonies in Asia and Hawaii, Japanese leaders met to consider the attack plans prepared by Imperial General Headquarters

The was part of the Supreme War Council and was established in 1893 to coordinate efforts between the Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy during wartime. In terms of function, it was approximately equivalent to the United States ...

. The summit occurred one day after the emperor had reprimanded General Hajime Sugiyama

was a Japanese field marshal and one of the leaders of Japan's military throughout most of World War II. As Army Minister in 1937, Sugiyama was a driving force behind the launch of hostilities against China in retaliation for the Marco Polo B ...

, chief of the IJA General Staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military un ...

, about the lack of success in China and the speculated low chances of victory against the United States, the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

, and their allies.

Konoe argued for more negotiations and for possible concessions to avert war. However, military leaders such as Sugiyama, Minister of War

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

General Hideki Tōjō, and chief of the IJN General Staff Fleet Admiral Osami Nagano

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy and one of the leaders of Japan's military during most of the Second World War. In April 1941, he became Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff. In this capacity, he served as the n ...

asserted that time had run out and that additional negotiations would be pointless. They urged swift military actions against all American and European colonies in Southeast Asia and Hawaii. Tōjō argued that yielding to the American demand to withdraw troops would wipe out all the gains of the Second Sino-Japanese War, depress Army morale

Morale, also known as esprit de corps (), is the capacity of a group's members to maintain belief in an institution or goal, particularly in the face of opposition or hardship. Morale is often referenced by authority figures as a generic value ...

, endanger Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Northeast China, Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 afte ...

and jeopardize tge control of Korea. Hence, doing nothing was the same as defeat and a loss of face

Face is a class of behaviors and customs practiced mainly in Asian cultures, associated with the morality, honor, and authority of an individual (or group of individuals), and its image in social groups.

Face refers to a sociological concept in ...

.

On October 16, 1941, Konoe resigned and proposed Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni

General was a Japanese imperial prince, a career officer in the Imperial Japanese Army and the 30th Prime Minister of Japan from 17 August 1945 to 9 October 1945, a period of 54 days. An uncle-in-law of Emperor Hirohito twice over, Prince Hi ...

, who was also the choice of the army and navy, as his successor. Hirohito chose Tōjō instead and was worried, as he told Konoe, about having the Imperial House being held responsible for a war against Western powers.

On November 3, 1941, Nagano presented a complete plan for the attack on Pearl Harbor to Hirohito. At the Imperial Conference on November 5, Hirohito approved the plan for a war against the United States, Britain and the Netherlands that was scheduled to start in early December if an acceptable diplomatic settlement were not achieved before then. Over the following weeks, Tōjō's military regime offered a final deal to the United States. It offered to leave only Indochina in return for large American economic aid. On November 26, the so-called Hull Memorandum (or Hull Note) rejected the offer and stated that in addition to leaving Indochina, the Japanese must leave China and agree to an

On November 3, 1941, Nagano presented a complete plan for the attack on Pearl Harbor to Hirohito. At the Imperial Conference on November 5, Hirohito approved the plan for a war against the United States, Britain and the Netherlands that was scheduled to start in early December if an acceptable diplomatic settlement were not achieved before then. Over the following weeks, Tōjō's military regime offered a final deal to the United States. It offered to leave only Indochina in return for large American economic aid. On November 26, the so-called Hull Memorandum (or Hull Note) rejected the offer and stated that in addition to leaving Indochina, the Japanese must leave China and agree to an Open Door Policy

The Open Door Policy () is the United States diplomatic policy established in the late 19th and early 20th century that called for a system of equal trade and investment and to guarantee the territorial integrity of Qing China. The policy wa ...

in the Far East.

On November 30, 1941,

On November 30, 1941, Prince Takamatsu

was the third son of Emperor Taishō (Yoshihito) and Empress Teimei (Sadako) and a younger brother of Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito). He became heir to the Takamatsu-no-miya (formerly Arisugawa-no-miya), one of the four ''shinnōke'' or branches of ...

warned his brother, Hirohito, that the navy felt that Japan could not fight more than two years against the United States and wished to avoid war. After consulting with Kōichi Kido

Marquis (July 18, 1889 – April 6, 1977) was a Japanese statesman who served as Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal of Japan from 1940 to 1945, and was the closest advisor to Emperor Hirohito throughout World War II. He was convicted of war crimes a ...

, who advised him to take his time until he was convinced, and Tōjō, Hirohito called Shigetarō Shimada

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II. He also served as Minister of the Navy. He was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Early life and education

A native of Tokyo, Shimada graduated from t ...

and Nagano, who reassured him that war would be successful. On December 1, Hirohito finally approved a "war against United States, Great Britain and Holland" during another Imperial Conference, to commence with a surprise attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet

The United States Pacific Fleet (USPACFLT) is a theater-level component command of the United States Navy, located in the Pacific Ocean. It provides naval forces to the Indo-Pacific Command. Fleet headquarters is at Joint Base Pearl Harbor� ...

at its main forward base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

Intelligence gathering

On February 3, 1940, Yamamoto briefed Captain Kanji Ogawa of Naval Intelligence on the potential attack plan and asked him to start intelligence gathering on Pearl Harbor. Ogawa already had spies in Hawaii, including Japanese Consular officials with an intelligence remit, and he arranged for help from a German already living in Hawaii who was an ''Abwehr

The ''Abwehr'' (German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', but the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context; ) was the German military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ''Wehrmacht'' from 1920 to 1944. A ...

'' agent. None had been providing much militarily useful information. He planned to add the 29-year-old Ensign Takeo Yoshikawa

was a Japanese spy in Hawaii before the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Early career

A 1933 graduate of the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy at Etajima (graduating at the top of his class), Yoshikawa served briefly at sea aboard the ...

. By the spring of 1941, Yamamoto officially requested additional Hawaiian intelligence, and Yoshikawa boarded the liner ''Nitta-maru'' at Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

. He had grown his hair longer than military length and assumed the cover name Tadashi Morimura.

Yoshikawa began gathering intelligence in earnest by taking auto trips around the main islands, touring Oahu in a small plane, and posing as a tourist. He visited Pearl Harbor frequently and sketched the harbor and location of ships from the crest of a hill. Once, he gained access to Hickam Field Hickam may refer to:

;Surname

*Homer Hickam (born 1943), American author, Vietnam veteran, and a former NASA engineer

** October Sky: The Homer Hickam Story, 1999 American biographical film

*Horace Meek Hickam (1885–1934), pioneer airpower advoca ...

in a taxi and memorized the number of visible planes, pilots, hangars, barracks and soldiers. He also discovered that Sunday was the day of the week on which the largest number of ships were likely to be in harbor, that PBY

The Consolidated PBY Catalina is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft that was produced in the 1930s and 1940s. In Canadian service it was known as the Canso. It was one of the most widely used seaplanes of World War II. Catalinas served w ...

patrol went out every morning and evening, and there was an antisubmarine net in the mouth of the harbor. Information was returned to Japan in coded form in Consular communications and by direct delivery to intelligence officers aboard Japanese ships calling at Hawaii by consulate staff.

In June 1941, German and Italian consulates were closed, and there were suggestions that those of Japan should be closed, as well. They were not because they continued to provide valuable information (''via'' MAGIC), and neither Roosevelt nor Hull wanted trouble in the Pacific. Had they been closed, however, it is possible Naval General Staff, which had opposed the attack from the outset, would have called it off since up-to-date information on the location of the Pacific Fleet, on which Yamamoto's plan depended, would no longer have been available.

Planning

Expecting war and seeing an opportunity in the forward basing of the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Hawaii, the Japanese began planning in early 1941 for an attack on Pearl Harbor. For the next several months, planning and organizing a simultaneous attack on Pearl Harbor and invasion of British and Dutch colonies to the south occupied much of the Japanese Navy's time and attention. The plans for the Pearl Harbor attack arose out of the Japanese expectation the U.S. would be inevitably drawn into war after a Japanese attack against Malaya and Singapore. The intent of a preventive strike on Pearl Harbor was to neutralize American naval power in the Pacific and to remove it from influencing operations against American, British, and Dutch colonies. Successful attacks on colonies were judged to depend on successfully dealing with the Pacific Fleet. Planning had long anticipated a battle in Japanese home waters after the U.S. fleet traveled across the Pacific while it was under attack by submarines and other forces all the way. The U.S. fleet would be defeated in a "decisive battle", as Russia'sBaltic Fleet

, image = Great emblem of the Baltic fleet.svg

, image_size = 150

, caption = Baltic Fleet Great ensign

, dates = 18 May 1703 – present

, country =

, allegiance = (1703–1721) (1721–1917) (1917–1922) (1922–1991)(1991–present)

...

had been in 1905. A surprise attack posed a twofold difficulty compared to longstanding expectations. First, the Pacific Fleet was a formidable force and would not be easy to defeat or to surprise. Second, Pearl Harbor's shallow waters made using conventional aerial torpedoes

Aerial may refer to:

Music

* ''Aerial'' (album), by Kate Bush

* ''Aerials'' (song), from the album ''Toxicity'' by System of a Down

Bands

*Aerial (Canadian band)

* Aerial (Scottish band)

* Aerial (Swedish band)

Performance art

* Aerial sil ...

ineffective. On the other hand, Hawaii's distance meant a successful surprise attack could not be blocked or quickly countered by forces from the Continental U.S.

Several Japanese naval officers had been impressed by the British action at the Battle of Taranto

The Battle of Taranto took place on the night of 11–12 November 1940 during the Second World War between British naval forces, under Admiral Andrew Cunningham, and Italian naval forces, under Admiral Inigo Campioni. The Royal Navy launched ...

in which 21 obsolete Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also used ...

disabled half the ''Regia Marina

The ''Regia Marina'' (; ) was the navy of the Kingdom of Italy (''Regno d'Italia'') from 1861 to 1946. In 1946, with the Italian constitutional referendum, 1946, birth of the Italian Republic (''Repubblica Italiana''), the ''Regia Marina'' ch ...

'', the Italian Navy. Admiral Yamamoto even dispatched a delegation to Italy, which concluded a larger and better-supported version of Cunningham's strike could force the U.S. Pacific Fleet to retreat to bases in California, which would give Japan the time needed to establish a "barrier" defense to protect Japanese control of the Dutch East Indies. The delegation returned to Japan with information about the shallow-running torpedoes Cunningham's engineers had devised.

Japanese strategists were undoubtedly influenced by Admiral Heihachiro Togo's surprise attack on the Russian Pacific Fleet

, image = Great emblem of the Pacific Fleet.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Russian Pacific Fleet Great emblem

, dates = 1731–present

, country ...

at the Battle of Port Arthur

The of 8–9 February 1904 marked the commencement of the Russo-Japanese War. It began with a surprise night attack by a squadron of Japanese destroyers on the neutral Russian fleet anchored at Port Arthur, Manchuria, and continued with an en ...

in 1904. Yamamoto's emphasis on destroying the American battleships was in keeping with the Mahanian doctrine shared by all major navies during this period, including the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

and the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

.

In a letter dated January 7, 1941, Yamamoto finally delivered a rough outline of his plan to Koshiro Oikawa, the Navy Minister, from whom he also requested to be made commander-in-chief of the air fleet to attack Pearl Harbor. A few weeks later, in yet another letter, Yamamoto requested for Admiral Takijiro Onishi, chief of staff of the Eleventh Air Fleet, to study the technical feasibility of an attack against the American base. Onishi gathered as many facts as possible about Pearl Harbor.

After first consulting with Kosei Maeda, an expert on aerial torpedo warfare, and being told that the harbor's shallow waters rendered such an attack almost impossible, Onishi summoned Commander

In a letter dated January 7, 1941, Yamamoto finally delivered a rough outline of his plan to Koshiro Oikawa, the Navy Minister, from whom he also requested to be made commander-in-chief of the air fleet to attack Pearl Harbor. A few weeks later, in yet another letter, Yamamoto requested for Admiral Takijiro Onishi, chief of staff of the Eleventh Air Fleet, to study the technical feasibility of an attack against the American base. Onishi gathered as many facts as possible about Pearl Harbor.

After first consulting with Kosei Maeda, an expert on aerial torpedo warfare, and being told that the harbor's shallow waters rendered such an attack almost impossible, Onishi summoned Commander Minoru Genda

was a Japanese military aviator and politician. He is best known for helping to plan the attack on Pearl Harbor. He was also the third Chief of Staff of the Japan Air Self-Defense Force.

Early life

Minoru Genda was the second son of a farmer ...

. After studying the original proposal put forth by Yamamoto, Genda agreed that "the plan is difficult but not impossible." Yamamoto gave the bulk of the planning to Rear Admiral Ryunosuke Kusaka, who was very worried about the area's air defenses. Yamamoto encouraged Kusaka by telling him, "Pearl Harbor is my idea and I need your support." Genda emphasized the attack should be carried out early in the morning and in total secrecy and use an aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

force

In physics, a force is an influence that can change the motion of an object. A force can cause an object with mass to change its velocity (e.g. moving from a state of rest), i.e., to accelerate. Force can also be described intuitively as a p ...

and several types of bombing.

Although attacking the U.S. Pacific Fleet anchorage would achieve surprise, it also carried two distinct disadvantages. The targeted ships would be sunk or damaged in very shallow water and so they clcould quite likely be salvaged and possibly returned to duty (as six of the eight battleships eventually were). Also, most of the crews would survive the attack since many would be on shore leave

Shore leave is the Leave (military), leave that professional sailors get to spend on dry land. It is also known as "liberty" within the United States Navy, United States Coast Guard, and United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps.

During the Age of ...

or would be rescued from the harbor afterward. Despite those concerns, Yamamoto and Genda pressed ahead.

By April 1941, the Pearl Harbor plan became known as ''Operation Z'', after the famous Z signal that was given by Admiral Tōgō at Tsushima. Over the summer, pilots trained in earnest near Kagoshima City

, abbreviated to , is the capital city of Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. Located at the southwestern tip of the island of Kyushu, Kagoshima is the largest city in the prefecture by some margin. It has been nicknamed the "Naples of the Eastern wo ...

. on Kyūshū

is the third-largest island of Japan's five main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands ( i.e. excluding Okinawa). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regional name referred to Kyushu and its surround ...

. Genda chose it because its geography and infrastructure presented most of the same problems bombers would face at Pearl Harbor. In training, each crew flew over the mountain behind Kagoshima, dove into the city, dodged buildings and smokestacks, and dropped dropping to at the piers. Bombardiers released torpedoes at a breakwater some away.

However, even that low-altitude approach would not overcome the problem of torpedoes from reaching the bottom in the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor. Japanese weapons engineers created and tested modifications to allow successful shallow water drops. The efforts resulted in a heavily-modified version of the Type 91 torpedo

The Type 91 was an aerial torpedo of the Imperial Japanese Navy. It was in service from 1931 to 1945. It was used in naval battles in World War II and was specially developed for attacks on ships in shallow harbours.

The Type 91 aerial torped ...

, which inflicted most of the ship damage during the eventual attack. Japanese weapons technicians also produced special armor-piercing bomb

Armour-piercing ammunition (AP) is a type of projectile designed to penetrate either body armour or vehicle armour.

From the 1860s to 1950s, a major application of armour-piercing projectiles was to defeat the thick armour carried on many warsh ...

s by fitting fins and release shackles to 14- and 16-inch (356- and 406-mm) naval shells. They could penetrate the lightly-armored decks of the old battleships.

Concept of Japanese invasion of Hawaii

At several stages during 1941, Japan's military leaders discussed the possibility of launching an invasion to seize theHawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kur ...

to provide Japan with a strategic base to shield its new empire, deny the United States any bases beyond the West Coast West Coast or west coast may refer to:

Geography Australia

* Western Australia

*Regions of South Australia#Weather forecasting, West Coast of South Australia

* West Coast, Tasmania

**West Coast Range, mountain range in the region

Canada

* Britis ...

and further isolate Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

.

Genda, who saw Hawaii as vital for American operations against Japan after war began, believed that Japan must follow any attack on Pearl Harbor with an invasion of Hawaii or risk losing the war. He viewed Hawaii as a base to threaten the West Coast of North America and perhaps as a negotiating tool for ending the war. He believed that after a successful air attack, 10,000-15,000 men could capture Hawaii, and he saw the operation as a precursor or an alternative to a Japanese invasion of the Philippines

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

. In September 1941, Commander Yasuji Watanabe of the Combined Fleet staff estimated two divisions (30,000 men) and 80 ships, in addition to the carrier strike force, could capture the islands. He identified two possible landing sites, near Haleiwa

Haleiwa () is a North Shore community and census-designated place (CDP) in the Waialua District of the island of Oahu, City and County of Honolulu.

Haleiwa is located on Waialua Bay, the mouth of Anahulu Stream (also known as Anahulu River). ...

and Kaneohe Bay

Kāneohe () is a census-designated place (CDP) included in the City and County of Honolulu and located in Hawaii state District of Koolaupoko on the island of Oahu. In the Hawaiian language, ''kāne ohe'' means "bamboo man". According to an a ...

, and proposed for both to be used in an operation that would require up to four weeks with Japanese air superiority.

Although the idea gained some support, it was soon dismissed for several reasons:

*Japan's ground forces, logistics, and resources were already fully committed not only to the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

but also for offensives in Southeast Asia, which were planned to occur almost simultaneously with the Pearl Harbor attack.

*The Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor o ...

(IJA) insisted it needed to focus on operations in China and Southeast Asia and so refused to provide substantial support elsewhere. Because of a lack of co-operation between the services, the IJN never discussed the Hawaiian invasion proposal with the IJA.

*Most of the senior officers of the Combined Fleet, particularly Admiral Nagano, believed an invasion of Hawaii was too risky.

With an invasion ruled out, it was agreed that a massive carrier-based three wave airstrike against Pearl Harbor to destroy the Pacific Fleet would be sufficient. Japanese planners knew that Hawaii, with its strategic location in the Central Pacific, would serve as a critical base from which the U.S. could extend its military power against Japan. However, the confidence of Japan's leaders that the conflict would be over quickly and that the U.S. would choose to negotiate a compromise, rather than fight a long bloody war, overrode that concern.

Watanabe's superior, Captain Kameto Kuroshima, who believed the invasion plan unrealistic, would later call his rejection of it the "biggest mistake" of his life.

Strike force

On November 26, 1941, the day that the

On November 26, 1941, the day that the Hull Note

The Hull note, officially the Outline of Proposed Basis for Agreement Between the United States and Japan, was the final proposal delivered to the Empire of Japan by the United States of America before the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1 ...

, which the Japanese leaders saw as an unproductive and old proposal, was received, the carrier force, under the command of Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo and already assembled in Hitokappu Wan, sortied for Hawaii under strict radio silence.

In 1941, Japan was one of the few countries capable of carrier aviation. The ''Kido Butai'', the Combined Fleet

The was the main sea-going component of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Until 1933, the Combined Fleet was not a permanent organization, but a temporary force formed for the duration of a conflict or major naval maneuvers from various units norm ...

's main carrier force of six aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s (at the time, the most powerful carrier force with the greatest concentration of air power in the history of naval warfare), embarked 359 airplanes, which were organized as the First Air Fleet

The , also known as the ''Kidō Butai'' ("Mobile Force"), was a name used for a combined carrier battle group comprising most of the aircraft carriers and carrier air groups of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during the first eight months of the P ...

. The carriers (flag

A flag is a piece of fabric (most often rectangular or quadrilateral) with a distinctive design and colours. It is used as a symbol, a signalling device, or for decoration. The term ''flag'' is also used to refer to the graphic design empl ...

), , , , and the newest, and , had 135 Mitsubishi A6M Type 0 fighters (Allied codename "Zeke," commonly called "Zero"), 171 Nakajima B5N Type 97 torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

s (Allied codename "Kate"), and 108 Aichi D3A Type 99 dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s (Allied codename "Val") aboard. Two fast battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s, two heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Tr ...

s, one light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

, nine destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s, and three fleet submarine

A fleet submarine is a submarine with the speed, range, and endurance to operate as part of a navy's battle fleet. Examples of fleet submarines are the British First World War era K class and the American World War II era ''Gato'' class.

The t ...

s provided escort and screening. In addition, the Advanced Expeditionary Force included 20 fleet and five two-man ''Ko-hyoteki''-class midget submarines, which were to gather intelligence and sink U.S. vessels attempting to flee Pearl Harbor during or soon after the attack. It also had eight oilers for underway fueling.

Execute order

On December 1, 1941, after the striking force was ''en route'', Chief of Staff Nagano gave a verbal directive to the commander of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, to inform him: Upon completion, the force was to return to Japan, re-equip, and redeploy for "Second Phase Operations." Finally, Order Number 9, issued on 1 December 1941 by Nagano, told Yamamoto to crush hostile naval and air forces in Asia; the Pacific and Hawaii; seize the main U.S., British, and Dutch bases in East Asia promptly; and "capture and secure the key areas of the southern regions." On the home leg, the force was ordered to be alert for tracking and counterattacks by the Americans and to return to the friendly base in theMarshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Internati ...

, rather than the Home Islands.

Lack of preparation

In 1924, General William L. Mitchell produced a 324-page report warning that future wars, including with Japan, would include a new role for aircraft against existing ships and facilities. He even discussed the possibility of an air attack on Pearl Harbor, but his warnings were ignored. Navy Secretary Knox had also appreciated the possibility of an attack at Pearl Harbor in a written analysis shortly after he had taken office. American commanders had been warned that tests had demonstrated shallow-water aerial torpedo attacks were possible, but no one in charge in Hawaii fully appreciated that. In a 1932

In 1924, General William L. Mitchell produced a 324-page report warning that future wars, including with Japan, would include a new role for aircraft against existing ships and facilities. He even discussed the possibility of an air attack on Pearl Harbor, but his warnings were ignored. Navy Secretary Knox had also appreciated the possibility of an attack at Pearl Harbor in a written analysis shortly after he had taken office. American commanders had been warned that tests had demonstrated shallow-water aerial torpedo attacks were possible, but no one in charge in Hawaii fully appreciated that. In a 1932 fleet problem The Fleet Problems are a series of naval exercises of the United States Navy conducted in the interwar period, and later resurrected by Pacific Fleet around 2014.

The first twenty-one Fleet Problems — labeled with roman numerals as Fleet Proble ...

, a surprise airstrike

An airstrike, air strike or air raid is an offensive operation carried out by aircraft. Air strikes are delivered from aircraft such as blimps, balloons, fighters, heavy bombers, ground attack aircraft, attack helicopters and drones. The offic ...

led by Admiral Harry E. Yarnell

Admiral Harry Ervin Yarnell (18 October 1875 – 7 July 1959) was an American naval officer whose career spanned over 51 years and three wars, from the Spanish–American War through World War II.

Among his achievements was proving, in 1932 war ga ...

had been judged a success and to have caused considerable damage, a finding that was corroborated in a 1938 exercise by Admiral Ernest King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was an American naval officer who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during World War II. As COMINCH-CNO, he directed the Un ...

. In October 1941, Lord Louis Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of Germa ...

visited Pearl Harbor. While lecturing American naval officers on Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

tactics against the Germans, an officer asked when and how the United States would enter the war. Mountbatten pointed to Pearl Harbor on a map of the Pacific and said "right here" by citing Japan's surprise attack on Port Arthur and the British attack on Taranto. In Washington, he warned Stark about how unprepared the base was against a bomber attack. Stark replied, "I'm afraid that putting some of your recommendations into effect is going to make your visit out there very expensive for the U.S. Navy."

By 1941, U.S. signals intelligence

Signals intelligence (SIGINT) is intelligence-gathering by interception of ''signals'', whether communications between people (communications intelligence—abbreviated to COMINT) or from electronic signals not directly used in communication ( ...

, through the Army's Signal Intelligence Service

The Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) was the United States Army codebreaking division through World War II. It was founded in 1930 to compile codes for the Army. It was renamed the Signal Security Agency in 1943, and in September 1945, became th ...

and the Office of Naval Intelligence

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) is the military intelligence agency of the United States Navy. Established in 1882 primarily to advance the Navy's modernization efforts, it is the oldest member of the U.S. Intelligence Community and serves ...

's OP-20-G

OP-20-G or "Office of Chief Of Naval Operations (OPNAV), 20th Division of the Office of Naval Communications, G Section / Communications Security", was the U.S. Navy's signals intelligence and cryptanalysis group during World War II. Its mission ...

, had intercepted and decrypted considerable Japanese diplomatic and naval cipher

In cryptography, a cipher (or cypher) is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption—a series of well-defined steps that can be followed as a procedure. An alternative, less common term is ''encipherment''. To encipher or encode i ...