Evacuations of civilians in Britain during the Second World War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The evacuation of civilians in Britain during the Second World War was designed to protect people, especially children, from the risks associated with aerial bombing of cities by moving them to areas thought to be less at risk.

Under the name "Operation Pied Piper", the effort began on 1 September 1939 and officially relocated 1.5 million people. There were further waves of official evacuation and re-evacuation from the south and east coasts in June 1940, when a seaborne invasion was expected, and from affected cities after the Blitz began in September 1940. Official evacuations also took place from the UK to other parts of the British Empire, and many non-official evacuations within and from the UK. Other mass movements of civilians included British citizens arriving from the Channel Islands, and displaced people arriving from continental Europe.

The evacuation of civilians in Britain during the Second World War was designed to protect people, especially children, from the risks associated with aerial bombing of cities by moving them to areas thought to be less at risk.

Under the name "Operation Pied Piper", the effort began on 1 September 1939 and officially relocated 1.5 million people. There were further waves of official evacuation and re-evacuation from the south and east coasts in June 1940, when a seaborne invasion was expected, and from affected cities after the Blitz began in September 1940. Official evacuations also took place from the UK to other parts of the British Empire, and many non-official evacuations within and from the UK. Other mass movements of civilians included British citizens arriving from the Channel Islands, and displaced people arriving from continental Europe.

Almost 3.75 million people were displaced, with around a third of the entire population experiencing some effects of the evacuation. In the first three days of official evacuation, 1.5 million people were moved: 827,000 children of school age; 524,000 mothers and young children (under 5); 13,000 pregnant women; 70,000 disabled people and over 103,000 teachers and other 'helpers'. Children were parted from their parents.

Goods as well as people were evacuated; organisations or departments departed the cities. Art treasures were sent to distant storage: The National Gallery collection spent the war at the

Almost 3.75 million people were displaced, with around a third of the entire population experiencing some effects of the evacuation. In the first three days of official evacuation, 1.5 million people were moved: 827,000 children of school age; 524,000 mothers and young children (under 5); 13,000 pregnant women; 70,000 disabled people and over 103,000 teachers and other 'helpers'. Children were parted from their parents.

Goods as well as people were evacuated; organisations or departments departed the cities. Art treasures were sent to distant storage: The National Gallery collection spent the war at the

A second evacuation effort started during and after the

A second evacuation effort started during and after the  When the Blitz began in September 1940, there were clear grounds for evacuation. Free travel and billeting allowance were offered to those who made private arrangements. They were also given to children, the elderly, the disabled, pregnant women, the ill and those who had lost their homes (some 250,000 in the first six weeks in London). By the combination of all the state and private efforts, London's population was reduced by almost 25%.

As bombing affected more towns, "assisted private evacuation" was extended. However, not all evacuated children, mothers and teachers were safe in the areas to which they had been evacuated. Air raids, unexploded bombs, military vehicles and military minefields posed risks to the evacuees wherever they were posted in the UK.

London proved resilient to bombing despite the heavy bombardment. The destruction in the smaller towns was more likely to provoke panic and spontaneous evacuations. The number of official evacuees rose to a peak of 1.37 million by February 1941. By September, it stood at just over one million. By the end of 1943, there were just 350,000 people officially billeted. Still, the V-1 flying bomb attacks from June 1944 provoked another significant exodus from London. Up to 1.5 million people left by September – only 20% were "official" evacuees.

From September 1944, the evacuation process was officially halted and reversed for most areas except for London and the east coast. Returning to London was not officially approved until June 1945. In March 1946, the billeting scheme was ended, with 38,000 people still without homes.

When the Blitz began in September 1940, there were clear grounds for evacuation. Free travel and billeting allowance were offered to those who made private arrangements. They were also given to children, the elderly, the disabled, pregnant women, the ill and those who had lost their homes (some 250,000 in the first six weeks in London). By the combination of all the state and private efforts, London's population was reduced by almost 25%.

As bombing affected more towns, "assisted private evacuation" was extended. However, not all evacuated children, mothers and teachers were safe in the areas to which they had been evacuated. Air raids, unexploded bombs, military vehicles and military minefields posed risks to the evacuees wherever they were posted in the UK.

London proved resilient to bombing despite the heavy bombardment. The destruction in the smaller towns was more likely to provoke panic and spontaneous evacuations. The number of official evacuees rose to a peak of 1.37 million by February 1941. By September, it stood at just over one million. By the end of 1943, there were just 350,000 people officially billeted. Still, the V-1 flying bomb attacks from June 1944 provoked another significant exodus from London. Up to 1.5 million people left by September – only 20% were "official" evacuees.

From September 1944, the evacuation process was officially halted and reversed for most areas except for London and the east coast. Returning to London was not officially approved until June 1945. In March 1946, the billeting scheme was ended, with 38,000 people still without homes.

Novels for adults featuring evacuation and evacuees are:

*'' Put Out More Flags'' by Evelyn Waugh, in which Waugh's anti-hero Basil Seal uses his position as Billeting Officer to extort bribes (for moving disruptive children elsewhere) from hapless and reluctant hosts.

*

Novels for adults featuring evacuation and evacuees are:

*'' Put Out More Flags'' by Evelyn Waugh, in which Waugh's anti-hero Basil Seal uses his position as Billeting Officer to extort bribes (for moving disruptive children elsewhere) from hapless and reluctant hosts.

* Other:

*In the

Other:

*In the

online free

* Wicks, Ben. ''No Time to Wave Goodbye'' (1989), 240p.

BBC

BBC People's War – Yvonne Devereux 'Evacuated to Canada'

Lecture transcript on Operation Pied Piper, 31 May 2006

The Evacuees Reunion Association

Watch the documentary ''Children from Overseas'' online

Operation Pied Piper

{{Portal bar, World War II Battle of Britain The Blitz Evacuations Politics of World War II United Kingdom home front during World War II

The evacuation of civilians in Britain during the Second World War was designed to protect people, especially children, from the risks associated with aerial bombing of cities by moving them to areas thought to be less at risk.

Under the name "Operation Pied Piper", the effort began on 1 September 1939 and officially relocated 1.5 million people. There were further waves of official evacuation and re-evacuation from the south and east coasts in June 1940, when a seaborne invasion was expected, and from affected cities after the Blitz began in September 1940. Official evacuations also took place from the UK to other parts of the British Empire, and many non-official evacuations within and from the UK. Other mass movements of civilians included British citizens arriving from the Channel Islands, and displaced people arriving from continental Europe.

The evacuation of civilians in Britain during the Second World War was designed to protect people, especially children, from the risks associated with aerial bombing of cities by moving them to areas thought to be less at risk.

Under the name "Operation Pied Piper", the effort began on 1 September 1939 and officially relocated 1.5 million people. There were further waves of official evacuation and re-evacuation from the south and east coasts in June 1940, when a seaborne invasion was expected, and from affected cities after the Blitz began in September 1940. Official evacuations also took place from the UK to other parts of the British Empire, and many non-official evacuations within and from the UK. Other mass movements of civilians included British citizens arriving from the Channel Islands, and displaced people arriving from continental Europe.

Background

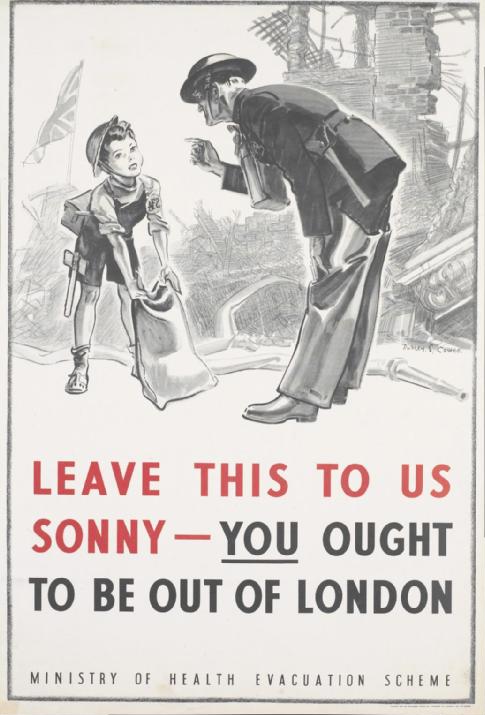

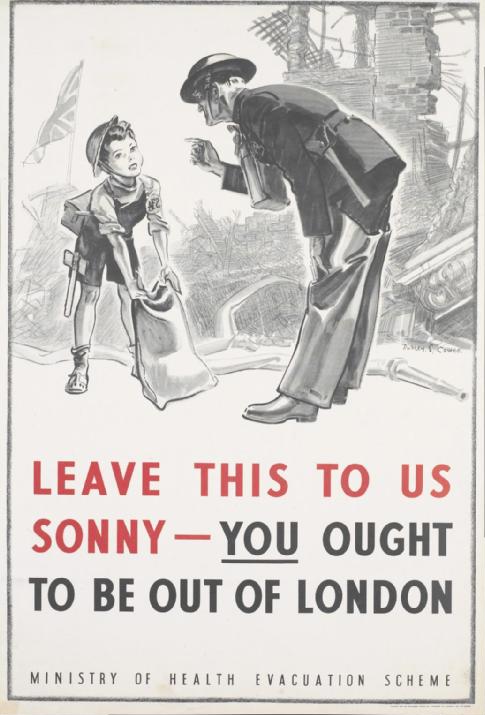

The Government Evacuation Scheme was developed during the summer of 1938 by the Anderson Committee and implemented by theMinistry of Health Ministry of Health may refer to:

Note: Italics indicate now-defunct ministries.

* Ministry of Health (Argentina)

* Ministry of Health (Armenia)

* Australia:

** Ministry of Health (New South Wales)

* Ministry of Health (The Bahamas)

* Ministry of ...

. The country was divided into zones, classified as either "evacuation", "neutral", or "reception", with priority evacuees being moved from the major urban centres and billeted on the available private housing in more rural areas. Each zone covered roughly a third of the population, although several urban areas later bombed had not been classified for evacuation.

In early 1939, the reception areas compiled lists of available housing. Space was found for about 2,000 people, and the government also constructed camps that provided a few thousand additional spaces.

The government began to publicise its plan through the local authorities in summer 1939. The government had overestimated demand: only half of all school-aged children were moved from the urban areas instead of the expected 80%. There was enormous regional variation: as few as 15% of the children were evacuated from some urban areas, while over 60% of children were evacuated from Manchester, Belfast and Liverpool. The refusal of the central government to spend large sums on preparation also reduced the effectiveness of the plan. In the event, over 3,000,000 people were evacuated.

Evacuation

Almost 3.75 million people were displaced, with around a third of the entire population experiencing some effects of the evacuation. In the first three days of official evacuation, 1.5 million people were moved: 827,000 children of school age; 524,000 mothers and young children (under 5); 13,000 pregnant women; 70,000 disabled people and over 103,000 teachers and other 'helpers'. Children were parted from their parents.

Goods as well as people were evacuated; organisations or departments departed the cities. Art treasures were sent to distant storage: The National Gallery collection spent the war at the

Almost 3.75 million people were displaced, with around a third of the entire population experiencing some effects of the evacuation. In the first three days of official evacuation, 1.5 million people were moved: 827,000 children of school age; 524,000 mothers and young children (under 5); 13,000 pregnant women; 70,000 disabled people and over 103,000 teachers and other 'helpers'. Children were parted from their parents.

Goods as well as people were evacuated; organisations or departments departed the cities. Art treasures were sent to distant storage: The National Gallery collection spent the war at the Manod

Manod Mawr is a mountain in North Wales and forms part of the Moelwynion. Although known as a mountain in the eastern Moelwyns, it and its sister peaks are sometimes known as the Ffestiniog hills.

Manod Mawr is a mountain which has been exte ...

Quarry near Ffestiniog, North Wales. The Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government of ...

moved to the small town of Overton, Hampshire and in 1939–40 moved 2,154 ton

Ton is the name of any one of several units of measure. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

Mainly it describes units of weight. Confusion can arise because ''ton'' can mean

* the long ton, which is 2,240 pounds

...

s of gold to the vaults of the Bank of Canada

The Bank of Canada (BoC; french: Banque du Canada) is a Crown corporation and Canada's central bank. Chartered in 1934 under the ''Bank of Canada Act'', it is responsible for formulating Canada's monetary policy,OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: Ca ...

in Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

. The BBC moved variety production to Bristol and Bedford and moved senior staff to Wood Norton near Evesham, Worcestershire

Evesham () is a market town and parish in the Wychavon district of Worcestershire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is located roughly equidistant between Worcester, Cheltenham and Stratford-upon-Avon. It lies within the Vale of Evesh ...

. Many senior Post Office staff were relocated to Harrogate. Some private companies moved head offices or their most vital records to comparative safety away from major cities.

Government functions were also evacuated. Under "Plan Yellow", some 23,000 civil servants and their paperwork were dispatched to available hotels in the better coastal resorts and spa towns. Other hotels were requisitioned and emptied for a possible last-ditch "Black Move" should London be destroyed or threatened by invasion. Under this plan, the nucleus of government would relocate to the West Midlands

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

—the War Cabinet and ministers would move to Hindlip Hall

Hindlip Hall is a stately home in Hindlip, Worcestershire, England. The first major hall was built before 1575, and it played a significant role in both the Babington and the Gunpowder plots, where it hid four people in priest holes. It was Hump ...

, Bevere House and Malvern College

Malvern College is an Independent school (United Kingdom), independent coeducational day and boarding school in Malvern, Worcestershire, Malvern, Worcestershire, England. It is a public school (United Kingdom), public school in the British sen ...

near Worcester and Parliament to Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon (), commonly known as just Stratford, is a market town and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon district, in the county of Warwickshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is situated on the River Avon, north-we ...

. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

was to relocate to Spetchley Park

Spetchley Park is a country mansion standing in 4500 acres of gardens and parkland in the hamlet of Spetchley, near Worcester, England. The house and park are separately Grade II* listed.

The house is built in two storeys of Bath stone with a ...

whilst King George VI and other members of the royal family would take up residence at Madresfield Court

Madresfield Court is a country house in Malvern, Worcestershire, England. The home of the Lygon family for nearly six centuries, it has never been sold and has passed only by inheritance since the 12th century; a line of unbroken family ownership ...

near Malvern

Malvern or Malverne may refer to:

Places Australia

* Malvern, South Australia, a suburb of Adelaide

* Malvern, Victoria, a suburb of Melbourne

* City of Malvern, a former local government area near Melbourne

* Electoral district of Malvern, an e ...

.

Some strained areas took the children into local schools by adopting the First World War expedient of "double shift education"—taking twice as long but also doubling the number taught. The movement of teachers also meant that almost a million children staying home had no source of education.

Evacuation centres

In 1939 the British Government passed the Camps Act 1939 which established the National Camps Corporation as a body to design and build residential camps for young people, which could provide opportunities for outdoor learning and also act as evacuation centres in the event of war. The architect T. S. Tait was responsible for the design of the buildings, which included accommodation for over 200 children and staff, recreational halls, wash blocks and a dining hall/kitchen complex. These camps were replicated in over thirty different rural locations around the country. During the war years, they acted as safe refuges for city children. After the war the ownership of the sites was transferred to the local authorities. Over the years most of these sites have been lost, but the best preserved example today isSayers Croft Sayers Croft is a large outdoor ‘learning camp’ located in the village of Ewhurst, Surrey. It is one of the few remaining 'Camp schools' built by the National Camps Corporation in 1939 to provide fresh air and fun activities for inner city chil ...

at Ewhurst, Surrey. The dining hall and kitchen complex is protected as a Grade II listed building because of the importance of Tait's work, and because of the painted murals depicting the life of the many evacuees. Evacuation Centres were also set up by the Foster Parent Plan (FPP) for Children Affected by War, later renamed Plan International

Plan International is a development and humanitarian organisation which works in over 75 countries across Africa, the Americas, and Asia to advance children’s rights and equality for girls. Its focus is on child protection, education, child par ...

.

One evacuated school was sponsored by the FPP in Knutsford, Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county t ...

, with each child being financially supported by an American citizen. One female pupil, named Paulette, was sponsored by Mrs Eleanor Roosevelt.

Overseas evacuation

The Children's Overseas Reception Board (CORB) approved 24,000 children for evacuation overseas. Between March and September 1940, 1,532 children were evacuated to Canada, mainly through thePier 21

Pier 21 was an ocean liner terminal and immigration shed from 1928 to 1971 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Nearly one million immigrants came to Canada through Pier 21, and it is the last surviving seaport immigration facility in Canada. The fac ...

immigration terminal; 577 to Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

; 353 to South Africa and 202 to New Zealand. The scheme was cancelled after the was torpedoed on 17 September 1940, killing 77 of the 90 CORB children aboard. However, in 1940 and 1941 about 14,000 children were evacuated privately to overseas relatives or foster families, including 6,000 to Canada and 5,000 to the United States.

The BBC cooperated with radio networks in the host countries, to make ''Children Calling Home

''Children Calling Home'' was an English-language radio programme, with the first episode on Christmas Day, 25 December 1940 as a collaboration between the United Kingdom's BBC's Home Service, CBC of Canada, and NBC of the United States, and br ...

'', a programme which enabled the evacuated children and their parents to talk to each other, live on air.

Other evacuations

A second evacuation effort started during and after the

A second evacuation effort started during and after the fall of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the German invasion of France during the Second World ...

. From 13 to 18 June 1940, around 100,000 children were evacuated (and in many cases re-evacuated). Efforts were made to remove the vulnerable from coastal towns in southern

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

and eastern England facing German-controlled areas. By July, over 200,000 children had been moved; some towns in Kent and East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

evacuated over 40% of the population. Also, some 30,000 people arrived from continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

and from 20 to 24 June 25,000 people arrived from the Channel Islands.

As thousands of Guernsey

Guernsey (; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; french: Guernesey) is an island in the English Channel off the coast of Normandy that is part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, a British Crown Dependency.

It is the second largest of the Channel Islands ...

school children arrived in northern England with their teachers, some were allowed to re-establish their schools in empty buildings. Guernsey's Forest School reopened in a church hall in Cheadle Hulme, Cheshire where it operated until August 1945. As a result of the evacuation of so many Guernsey people to England, those returning no longer spoke the Guernsey language (Guernsiaise) after the war.

One of the speediest moves was accomplished by the London, Midland and Scottish Railway

The London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMSIt has been argued that the initials LMSR should be used to be consistent with LNER, GWR and SR. The London, Midland and Scottish Railway's corporate image used LMS, and this is what is generally u ...

when it transferred its headquarters out of London. The company took over The Grove, on the estate of the Earl of Clarendon in Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

. This was made ready as offices and a number of huts built in the surrounding park. On 1 September 1939, it was decided to move in and the transfer was completed before war was declared two days later. Within three days some 3,000 of the staff were based at the new headquarters.

When the Blitz began in September 1940, there were clear grounds for evacuation. Free travel and billeting allowance were offered to those who made private arrangements. They were also given to children, the elderly, the disabled, pregnant women, the ill and those who had lost their homes (some 250,000 in the first six weeks in London). By the combination of all the state and private efforts, London's population was reduced by almost 25%.

As bombing affected more towns, "assisted private evacuation" was extended. However, not all evacuated children, mothers and teachers were safe in the areas to which they had been evacuated. Air raids, unexploded bombs, military vehicles and military minefields posed risks to the evacuees wherever they were posted in the UK.

London proved resilient to bombing despite the heavy bombardment. The destruction in the smaller towns was more likely to provoke panic and spontaneous evacuations. The number of official evacuees rose to a peak of 1.37 million by February 1941. By September, it stood at just over one million. By the end of 1943, there were just 350,000 people officially billeted. Still, the V-1 flying bomb attacks from June 1944 provoked another significant exodus from London. Up to 1.5 million people left by September – only 20% were "official" evacuees.

From September 1944, the evacuation process was officially halted and reversed for most areas except for London and the east coast. Returning to London was not officially approved until June 1945. In March 1946, the billeting scheme was ended, with 38,000 people still without homes.

When the Blitz began in September 1940, there were clear grounds for evacuation. Free travel and billeting allowance were offered to those who made private arrangements. They were also given to children, the elderly, the disabled, pregnant women, the ill and those who had lost their homes (some 250,000 in the first six weeks in London). By the combination of all the state and private efforts, London's population was reduced by almost 25%.

As bombing affected more towns, "assisted private evacuation" was extended. However, not all evacuated children, mothers and teachers were safe in the areas to which they had been evacuated. Air raids, unexploded bombs, military vehicles and military minefields posed risks to the evacuees wherever they were posted in the UK.

London proved resilient to bombing despite the heavy bombardment. The destruction in the smaller towns was more likely to provoke panic and spontaneous evacuations. The number of official evacuees rose to a peak of 1.37 million by February 1941. By September, it stood at just over one million. By the end of 1943, there were just 350,000 people officially billeted. Still, the V-1 flying bomb attacks from June 1944 provoked another significant exodus from London. Up to 1.5 million people left by September – only 20% were "official" evacuees.

From September 1944, the evacuation process was officially halted and reversed for most areas except for London and the east coast. Returning to London was not officially approved until June 1945. In March 1946, the billeting scheme was ended, with 38,000 people still without homes.

Traumatic effect on children

Even at the time, there were some that had grave concerns about the psychological effect on especially the younger children, and wondered whether they would be better off taking the risks with their parents. In the early 2000s a number of evacuees came forward to clarify the many "bad sides" of the evacuation.Cultural impact

The movement of urban children of all classes to unfamiliar rural locations, without their parents, had a major impact. The Evacuees Reunion Association was formed with the support of theImperial War Museum

Imperial War Museums (IWM) is a British national museum organisation with branches at five locations in England, three of which are in London. Founded as the Imperial War Museum in 1917, the museum was intended to record the civil and military ...

. It provides opportunities for former evacuees to contribute and share evacuation experiences and for researchers to request information such as the long-term effects of evacuation upon children.

The evacuation spawned a whole literature of children's and young adult fiction. The convenience of the setting for the writer is clear, allowing the child heroes to have adventures in a strange, new world. Some of the authors, like Nina Bawden

Nina Bawden CBE, FRSL, JP (19 January 1925 – 22 August 2012) was an English novelist and children's writer. She was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1987 and the Lost Man Booker Prize in 2010. She is one of very few who have both se ...

, had themselves experienced evacuation.

*Kitty Barne

Marion Catherine "Kitty" Barne (17 November 1882 – 3 February 1961) was a British screenwriter and author of children's books, especially on music and musical themes. She won the 1940 Carnegie Medal for British children's books.

Biography

Ba ...

's Carnegie Medal-winning ''Visitors from London

''Visitors from London'' is a children's novel written by Kitty Barne, illustrated with 40 drawings by Ruth Gervis, published by Dent in 1940. Set in Sussex, it is a story of World War II on the home front; it features preparing for and hosting c ...

'' (1940) is an early novel about evacuees, set in Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

.

*In Richmal Crompton's ''William and the Evacuees'' (1940), William Brown is envious of the special treats the evacuees receive and organizes an 'evacuation' of the village children.

*In C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Oxford University (Magdalen College, 1925–1954) and Cambridge Univers ...

's novel ''The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

''The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe'' is a fantasy novel for children by C. S. Lewis, published by Geoffrey Bles in 1950. It is the first published and best known of seven novels in ''The Chronicles of Narnia'' (1950–1956). Among all the ...

'' (1950) the Pevensie children are evacuated from London to the stately manor that contains the wardrobe portal to Narnia. It is never stated in which part of England the house was situated.

*William Golding

Sir William Gerald Golding (19 September 1911 – 19 June 1993) was a British novelist, playwright, and poet. Best known for his debut novel ''Lord of the Flies'' (1954), he published another twelve volumes of fiction in his lifetime. In 1980 ...

's novel '' Lord of the Flies'' (1954) is about a planeful of evacuating children who are shot down over a tropical island.

* Michael Bond's beloved children's book character '' Paddington Bear'' (1958) is an anthropomorphised orphan bear, who – having stowed away from "Darkest Peru" – is found by a family at Paddington railway station in London, sitting on his suitcase with a note attached to his coat that reads, "Please look after this bear. Thank you." Bond has said that his memories of newsreels showing trainloads of child evacuees leaving London during WWII, with labels around their necks and their possessions in small suitcases, prompted him to do the same for Paddington.

*Nina Bawden

Nina Bawden CBE, FRSL, JP (19 January 1925 – 22 August 2012) was an English novelist and children's writer. She was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1987 and the Lost Man Booker Prize in 2010. She is one of very few who have both se ...

's novel '' Carrie's War'' (1973) is about Carrie and Nick, who encounter different religions when they are evacuated to Wales.

*Noel Streatfeild

Mary Noel Streatfeild OBE (24 December 1895 –11 September 1986) was an English author, best known for children's books including the "Shoes" books, which were not a series (though some books made references to others). Random House, the ...

's novel ''When the Sirens Wailed'' (1974) is about three evacuees and covers issues like rations for evacuees, relationship between evacuees and townspeople, and the problems encountered by those who stayed behind.

* Michael Morpurgo's novel ''Friend or Foe'' (1977) is about two evacuees who befriend the crew of a crashed German bomber hiding on Dartmoor.

* Diana Wynne Jones's novel ''A Tale of Time City

''A Tale of Time City'' was first published in 1987 by British author Diana Wynne Jones. It tells the story of a girl, Vivian Smith, who is kidnapped while being evacuated from London during World War II and caught up in a struggle to preserve ...

'' (1987) begins with the main character, Vivian, being evacuated from London. Jones herself was evacuated to Wales in 1939.

* Michelle Magorian's novel, '' Goodnight Mister Tom'' (1981), tells the story of the evacuee Willie Beech and elderly Thomas Oakley with whom he is billeted. It was made into a TV film starring John Thaw as Mr Tom.

*In the Disney sequel to '' Peter Pan'', ''Return to Neverland

''Return to Never Land'' (also known as ''Peter Pan in: Return to Never Land'' and later retitled ''Peter Pan II: Return to Never Land'' on current home video release) is a 2002 American animated adventure fantasy film produced by Disney MovieToon ...

'', Wendy Darling's children Jane and Daniel are to prepare for evacuation before Jane is kidnapped by Captain Hook. The introduction to the movie details about the evacuation order and how children need Peter Pan now more than ever.

* Kit Pearson's ''Guests of War'' trilogy, beginning with '' The Sky Is Falling'' (1989), chronicles the story of ten-year-old Norah Stoakes and her younger brother Gavin, who are evacuated to Toronto.

*In the 2015 videogame '' We Happy Few'', set in an alternate reality where Germany successfully invaded and occupied Britain during the war, the main character Arthur Hastings betrays his autistic brother Percival giving him up to the collaborationist

Wartime collaboration is cooperation with the enemy against one's country of citizenship in wartime, and in the words of historian Gerhard Hirschfeld, "is as old as war and the occupation of foreign territory".

The term ''collaborator'' dates to t ...

authorities in order to be sent to Germany.

Novels for adults featuring evacuation and evacuees are:

*'' Put Out More Flags'' by Evelyn Waugh, in which Waugh's anti-hero Basil Seal uses his position as Billeting Officer to extort bribes (for moving disruptive children elsewhere) from hapless and reluctant hosts.

*

Novels for adults featuring evacuation and evacuees are:

*'' Put Out More Flags'' by Evelyn Waugh, in which Waugh's anti-hero Basil Seal uses his position as Billeting Officer to extort bribes (for moving disruptive children elsewhere) from hapless and reluctant hosts.

*Noel Streatfeild

Mary Noel Streatfeild OBE (24 December 1895 –11 September 1986) was an English author, best known for children's books including the "Shoes" books, which were not a series (though some books made references to others). Random House, the ...

's adult novel ''Saplings'' (1945).

* Connie Willis's two-volume novel '' Blackout/All Clear'' (2010) has extensive chapters about a time travelling character from the future, a historian named Merope (she takes on the persona of Eileen O'Reilly, an Irish maid), who intends to study the impact of evacuation on the children. When she becomes stranded in the past, she eventually adopts two bratty children to raise herself.

Non-fiction:

*''Out of Harm's Way'' by Jessica Mann

Jessica Mann (13 September 1937 – 10 July 2018) was a British writer and novelist. She also wrote several non-fiction books, including ''Out of Harm's Way'', an account of the overseas evacuation of children from Britain in World War II.

Biog ...

(Headline Publishers 2005) tells the story of the overseas evacuation of children from Britain during the Second World War.

*In Pam Hobbs

Pam Hobbs is a travel writer and author.

Life and work

Hobbs is the youngest of seven daughters born in 1929 to Edie and Jack Hobbs in Leigh-on-Sea, Essex, in southern England. She has written about her experience of evacuation as a child.

Ho ...

's memoir ''Don't Forget to Write: the true story of an evacuee and her family'' (2009), a 10-year-old is evacuated in 1940 from Leigh-on-Sea, Essex to Derbyshire, where she lives with a number of families and encounters a range of receptions from love to outright hostility – and enormous cultural differences.

*Alan Derek Clifton published his memories of being evacuated to Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia was a British protectorate in southern Africa, south central Africa, now the independent country of Zambia. It was formed in 1911 by Amalgamation (politics), amalgamating the two earlier protectorates of Barotziland-North-West ...

in 1940 in the book entitled, ''From Cockney to Colonial (And Back Again)'' (2010).

*Ben Wicks

Ben Wicks, (born Alfred Wicks; October 1, 1926 – September 10, 2000) was a British-born Canadian cartoonist, illustrator, journalist and author.

Biography

Wicks was a Cockney born into a poor, working class, working-class family in London ...

's ''No Time to Wave Goodbye'' and ''The Day They Took the Children''.

*''Britain's Wartime Evacuees'' by Gillian Mawson Gillian Mawson Gillian may refer to:

Places

* Gillian Settlement, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

People

Gillian (variant Jillian) is an English feminine given name, frequently shortened to Gill.

It originates as a feminine form of the name Julian (given n ...

(Pen and Sword, 2016) shares the personal testimony of child and adult evacuees in Britain during the Second World War

*''Guernsey Evacuees'' by Gillian Mawson Gillian may refer to:

Places

* Gillian Settlement, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

People

Gillian (variant Jillian) is an English feminine given name, frequently shortened to Gill.

It originates as a feminine form of the name Julian (given n ...

(History Press, 2012) shares the personal testimony of Guernsey evacuees in Britain during the Second World War

Other:

*In the

Other:

*In the 20th Century Fox

20th Century Studios, Inc. (previously known as 20th Century Fox) is an American film production company headquartered at the Fox Studio Lot in the Century City area of Los Angeles. As of 2019, it serves as a film production arm of Walt Dis ...

movie '' On the Sunny Side'' (1942), Roddy McDowall portrays an evacuated English boy who comes to live with an American family in Ohio.

*Stephen Poliakoff

Stephen Poliakoff (born 1 December 1952) is a British playwright, director and screenwriter. In 2006 Gerard Gilbert of ''The Independent'' described him as the UK's "pre-eminent TV dramatist" who had "inherited Dennis Potter's crown".

Early ...

's television drama '' Perfect Strangers'' (2001) includes a lengthy flashback of two evacuated sisters who leave the family they are sent to and live as wild children in the woods for the remainder of the war.

*In the movie '' Bedknobs and Broomsticks'' (1971), the evacuated children are taken in by a good witch-in-training.

*In the movie '' The Woman in Black 2: Angel of Death'' (2014), the major plot of the film involves a headmistress and a teacher evacuating a group of children out of London. One of the children lost his parents in a Blitz.

See also

*London in World War II

As the national capital, and by far the largest city, London was central to the British war effort. It was the favourite target of the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) in 1940, and in 1944-45 the target of the V-1 flying bomb, V-1 cruise missile and ...

* Battle of Britain

* British anti-invasion preparations of the Second World War

* Trekking during the Blitz

Large numbers of British civilians engaged in trekking during the Blitz. This involved leaving cities at night to sleep in nearby towns and rural areas. The practice was most prevalent in provincial cities during early 1941. While the British Gover ...

* Evacuations of children in Germany during World War II

* Evacuations of civilians in Japan during World War II

* Evacuation in the Soviet Union

Evacuation in the Soviet Union was the mass migration of western Soviet citizens and its industries eastward as a result of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia launched by Nazi Germany in June 1941 as part of World War II. Nearly sixtee ...

* Kindertransport

* Evacuation of civilians from the Channel Islands in 1940

* Q Camp

The Q Camps (Q for query or quest) were two experimental communities set up at Hawkspur Green in England. They were based on Planned Environment Therapy developed by Marjorie Franklin. This therapy focuses on well-functioning parts of a patient� ...

: experimental children's community

References

Further reading

* Baumel, Judith Tydor. "Twice a Refugee: The Jewish Refugee Children in Great Britain during Evacuation, 1939--1943" ''Jewish Social Studies'' (1983) 45#2 pp175–184. * Crosby, Travis L. ''Impact of Civilian Evacuation in the Second World War'' (1986) 176p. * Jackson, Carlton. ''Who Will Take Our Children?'' (1985), 217p. * * Gartner, Niko. "Administering'Operation Pied Piper'-how the London County Council prepared for the evacuation of its schoolchildren 1938-1939." ''Journal of Educational Administration & History'' 42#1 (2010): 17–32. * Kushner, Tony."Horns and Dilemmas: Jewish Evacuees in Britain during the Second World War." ''Immigrants & Minorities'' (1988) 7#3 pp 273–291. * Macnicol, John. "The effect of the evacuation of schoolchildren on official attitudes to state intervention." in Harold L. Smith, ed., ''War and Social Change: British Society in the Second World War'' (1986): 3-31. * Mawson, Gillian. ''Britain's Wartime Evacuees: The People, Places and Stories of the Evacuation Told Through the Accounts of Those Who Were There.'': 117–130. Pen and Sword. December 2016 *Parsons Martin (ed) ''Children. The Invisible Victims of War''. DSM Oct 2008 *Parsons Martin ''War Child. Children Caught in Conflict''. (History Press, 2008) *Parsons Martin ''Manchester Evacuation. The Exception to the Rule''. DSM publishing. April 2004 *Parsons Martin '' 'I’ll take that one!’ Dispelling the Myths of Civilian Evacuation in the UK during World War Two.'' 290pp (Beckett Karlson, 1998). . *Parsons Martin ''Waiting to go home!'' (Beckett Karlson, 1999). *Parsons M & Starns P. ''The Evacuation. The true Story'' (1999, DSM & BBC). * Preston, A. M. '"The Evacuation of Schoolchildren from Newcastle Upon Tyne, 1939-1942: An Assessment of the Factors which Influenced the Nature of Educational Provision in Newcastle and its Reception Areas," ''History of Education'' (1989) 18#3 pp 231–241. 11p. * Titmuss, Richard. ''Problems of Social Policy'' (1950) famous social science study of the evacuationonline free

* Wicks, Ben. ''No Time to Wave Goodbye'' (1989), 240p.

External links

BBC

BBC People's War – Yvonne Devereux 'Evacuated to Canada'

Lecture transcript on Operation Pied Piper, 31 May 2006

The Evacuees Reunion Association

Watch the documentary ''Children from Overseas'' online

Operation Pied Piper

{{Portal bar, World War II Battle of Britain The Blitz Evacuations Politics of World War II United Kingdom home front during World War II