Elizabeth Dilling on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

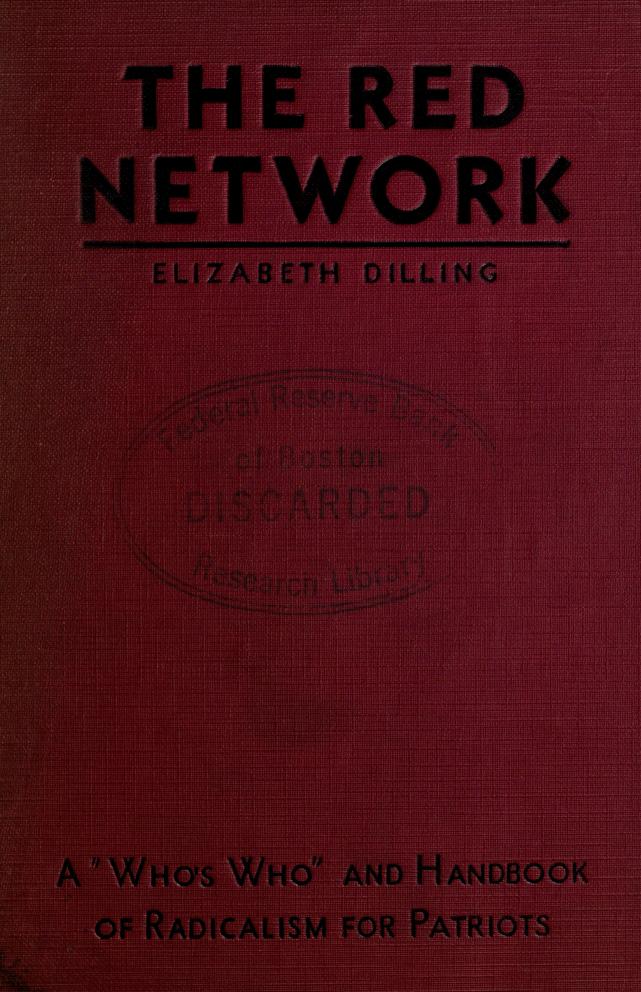

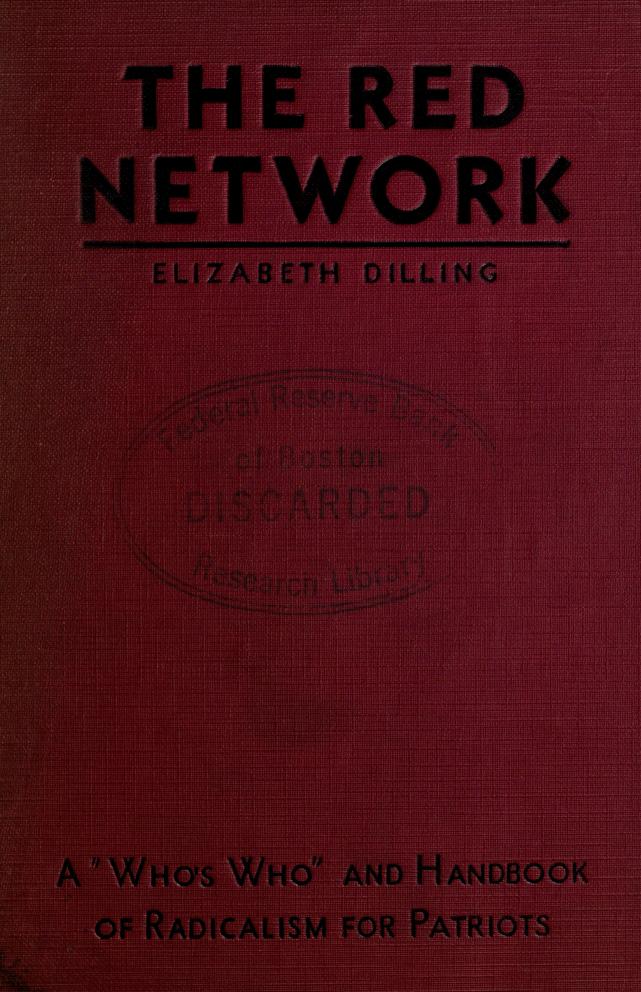

Elizabeth Eloise Kirkpatrick Dilling (April 19, 1894 – May 26, 1966) was an American writer and political activist.Dye, 6 In 1934, she published ''The Red Network—A Who's Who and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots'', which catalogs over 1,300 suspected communists and their sympathizers. Her books and lecture tours established her as the pre-eminent female right-wing activist of the 1930s, and one of the most outspoken critics of the New Deal.

Dilling was the best-known leader of the World War II women's

Elizabeth Eloise Kirkpatrick Dilling (April 19, 1894 – May 26, 1966) was an American writer and political activist.Dye, 6 In 1934, she published ''The Red Network—A Who's Who and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots'', which catalogs over 1,300 suspected communists and their sympathizers. Her books and lecture tours established her as the pre-eminent female right-wing activist of the 1930s, and one of the most outspoken critics of the New Deal.

Dilling was the best-known leader of the World War II women's

Dilling's political activism was spurred by the "bitter opposition" she encountered upon her return to Illinois in 1931, "against my telling the truth about Russia ... from suburbanite 'intellectual' friends and from my own Episcopal minister." She began public speaking as a hobby, following her doctor's advice. Iris McCord, a Chicago radio broadcaster who taught at the

Dilling's political activism was spurred by the "bitter opposition" she encountered upon her return to Illinois in 1931, "against my telling the truth about Russia ... from suburbanite 'intellectual' friends and from my own Episcopal minister." She began public speaking as a hobby, following her doctor's advice. Iris McCord, a Chicago radio broadcaster who taught at the

*A character based on Dilling named "Adelaide Tarr Gimmitch" appears in the novel ''

*A character based on Dilling named "Adelaide Tarr Gimmitch" appears in the novel ''

''The Red Network, A "Who's Who" and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots''

(1934, 1935, 1936, 1977) * ''"Lady Patriot" Replies'' (1936)

''The Roosevelt Red Record and Its Background''

(1936) * ''Dare We Oppose Red Treason?'' (1937). . * ''The Red Betrayal of the Churches'' (1938). .

''The Octopus''

by Rev. Frank Woodruff Johnson seud.(Oct. 1940; Sons of Liberty, 1985, 1986) * ''The Plot Against Christianity'' (1964) **Republished a

''The Jewish Religion: Its Influence Today''.

"The Powers of Perception: An Intimate Connection with Elizabeth Dilling"

East Tennessee State University. * * * *. * * * *Smith, Jason Scott (2014). A Concise History of the New Deal. 1st ed. New York: Cambridge University Press. Cambridge Books Online. Web. April 7, 2016. *Walker, Samuel (2012). Presidents and Civil Liberties from Wilson to Obama. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cambridge Books Online. Web. April 6, 2016.

''Prints and Photographs Online Catalog'', Library of Congress

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dilling, Elizabeth 1894 births 1966 deaths People from Chicago American people of British descent American Episcopalians American women civilians in World War II American political writers Anti–World War II activists Anti-communist propagandists Antisemitic publications University of Chicago alumni American anti-war activists Old Right (United States) Place of death missing American conspiracy theorists Pseudonymous women writers 20th-century pseudonymous writers History of United States isolationism American women non-fiction writers Far-right politics in the United States American anti-communists Activists from Illinois

Elizabeth Eloise Kirkpatrick Dilling (April 19, 1894 – May 26, 1966) was an American writer and political activist.Dye, 6 In 1934, she published ''The Red Network—A Who's Who and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots'', which catalogs over 1,300 suspected communists and their sympathizers. Her books and lecture tours established her as the pre-eminent female right-wing activist of the 1930s, and one of the most outspoken critics of the New Deal.

Dilling was the best-known leader of the World War II women's

Elizabeth Eloise Kirkpatrick Dilling (April 19, 1894 – May 26, 1966) was an American writer and political activist.Dye, 6 In 1934, she published ''The Red Network—A Who's Who and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots'', which catalogs over 1,300 suspected communists and their sympathizers. Her books and lecture tours established her as the pre-eminent female right-wing activist of the 1930s, and one of the most outspoken critics of the New Deal.

Dilling was the best-known leader of the World War II women's isolationist

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entan ...

movement, a grass-roots

A grassroots movement is one that uses the people in a given district, region or community as the basis for a political or economic movement. Grassroots movements and organizations use collective action from the local level to effect change at t ...

campaign that pressured Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

to refrain from helping the Allies. She was among 28 anti-war campaigners charged with sedition in 1942; the charges were dropped in 1946. While academic studies have predominantly ignored both the anti-war " Mothers' movement" and right-wing activist women in general, Dilling's writings secured her a lasting influence among right-wing groups.Frederickson 825–826 She organized the Paul Reveres, an anti-communist organization, and was a member of the America First Committee

The America First Committee (AFC) was the foremost United States isolationist pressure group against American entry into World War II. Launched in September 1940, it surpassed 800,000 members in 450 chapters at its peak. The AFC principally supp ...

.

Early life and family

Dilling was born Elizabeth Eloise Kirkpatrick on April 19, 1894, inChicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Illinois. Her father, Lafayette Kirkpatrick, was a surgeon of Scotch-Irish ancestry; her mother, Elizabeth Harding, was of English and French ancestry. Her father died when she was six weeks old, after which her mother added to the family income by selling real estate. Dilling's brother, Lafayette Harding Kirkpatrick, who was seven years her senior, became wealthy by the age of 23 after developing properties in Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only state ...

. Dilling had an Episcopalian upbringing, and attended a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

girls' school, Academy of Our Lady. She was highly religious, and was known to send her friends 40-page letters about the Bible. Prone to bouts of depression, she went on vacations in the US, Canada, and Europe with her mother.

In 1912, she enrolled at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, where she studied music and languages, intending to become an orchestral musician. She studied the harp under Walfried Singer, the Chicago Symphony's harpist. She left after three years before graduating, lonely and bitterly disillusioned.Jeansonne, 8 In 1918, she married Albert Dilling, an engineer studying law who attended the same Episcopalian church as Elizabeth. The couple were well off financially, thanks to Elizabeth's inherited money and Albert's job as chief engineer for the Chicago Sewerage District. They lived in Wilmette

Wilmette is a village in New Trier Township, Cook County, Illinois, United States. Bordering Lake Michigan and Evanston, Illinois, it is located north of Chicago's downtown district. Wilmette had a population of 27,087 at the 2010 census. The ...

, a Chicago suburb, and had two children, Kirkpatrick in 1920, and Elizabeth Jane in 1925.

The family traveled abroad at least ten times between 1923 and 1939, experiences that focused Dilling's political outlook and served to convince her of American superiority.Jeansonne, 9 In 1923, they visited Britain, France and Italy. Offended by the lack of gratitude from the British for American intervention in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Dilling vowed to oppose any future American involvement in European conflict.Erickson, 474–475 They spent a month in the Soviet Union in 1931, where local guides, who Dilling claimed were Jews, told her that communism would take over the world and showed her a map of the US in which the cities were renamed after Soviet heroes. She documented her travels in home movies, filming such scenes as bathers swimming nude in a river beneath a Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

church. She was appalled by communism's "atheism, sex degeneracy, broken homes ndclass hatred."

Dilling visited Germany in 1931 and, when she returned in 1938, noted a "great improvement of conditions". She attended Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

meetings, and the German government paid her expenses. She wrote that "The German people under Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

are contented and happy. ... don't believe the stories you hear that this man has not done a great good for this country." In 1938, she toured Palestine, where she filmed what she described as Jewish immigrants ruining the country. While touring Spain, then embroiled in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

, she filmed "Red torture chamber

A torture chamber is a room where torture is inflicted.

s" and burnt-out churches, "ruined by the Reds with the same satanic Jewish glee shown in Russia." She visited Japan, which she viewed as the only Christian nation in Asia, and in 1939, she returned to visit Spain, for a second time.

Anti-communism

Dilling's political activism was spurred by the "bitter opposition" she encountered upon her return to Illinois in 1931, "against my telling the truth about Russia ... from suburbanite 'intellectual' friends and from my own Episcopal minister." She began public speaking as a hobby, following her doctor's advice. Iris McCord, a Chicago radio broadcaster who taught at the

Dilling's political activism was spurred by the "bitter opposition" she encountered upon her return to Illinois in 1931, "against my telling the truth about Russia ... from suburbanite 'intellectual' friends and from my own Episcopal minister." She began public speaking as a hobby, following her doctor's advice. Iris McCord, a Chicago radio broadcaster who taught at the Moody Bible Institute

Moody Bible Institute (MBI) is a private evangelical Christian Bible college founded in the Near North Side of Chicago, Illinois, US by evangelist and businessman Dwight Lyman Moody in 1886. Historically, MBI has maintained positions that have ...

, arranged for her to address local church groups. Within a year Dilling was touring the Midwest, the Northeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each se ...

and occasionally the West Coast, accompanied by her husband. She showed her home movies of the Soviet Union and made the same speech several times a week to audiences sometimes as large as several hundred, hosted by organizations such as the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) and the American Legion.Jeansonne, 10Erickson 478

In 1932, Dilling co-founded the Paul Reveres, an anti-communist organization with headquarters in Chicago which eventually had 200 local chapters. She left in 1934, after a dispute with the co-founder Col. Edwin Marshall Hadley, and it folded soon after due to lack of interest. With McCord's encouragement, her lectures were published in a local Wilmette newspaper in 1932, and then collected in a pamphlet entitled ''Red Revolution: Do We Want It Here?'' Dilling claimed that the DAR printed and distributed thousands of copies.

Beginning in early 1933, Dilling spent twelve to eighteen hours a day for eighteen months researching and cataloging suspected subversives. Her sources included the 1920 four-volume report of the Joint Legislative Committee to Investigate Seditious Activities, and Representative Hamilton Fish

Hamilton Fish (August 3, 1808September 7, 1893) was an American politician who served as the 16th Governor of New York from 1849 to 1850, a United States Senator from New York from 1851 to 1857 and the 26th United States Secretary of State ...

's 1931 report of an anti-communist investigation. The result was ''The Red Network—A Who's Who and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots,'' hailed with irony in ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hu ...

'' as a "handy, compact reference work". The first half of the 352-page book was a collection of essays, mostly copied from ''Red Revolution''. The second half contained descriptions of more than 1,300 "Reds" (including international figures such as Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

and Chiang Kai-shek), and more than 460 organizations described as "Communist, Radical Pacifist, Anarchist, Socialist, r I.W.W. controlled".Jeansonne, 12

The book was reprinted eight times and sold more than 16,000 copies by 1941. Thousands more were given away. It was sold in Chicago book stores and by mail order from Dilling's house. It was distributed by the KKK, the Knights of the White Camellia, the German-American Bund

The German American Bund, or the German American Federation (german: Amerikadeutscher Bund; Amerikadeutscher Volksbund, AV), was a German-American Nazi organization which was established in 1936 as a successor to the Friends of New Germany (FoN ...

, and the Aryan Bookstores. Subscribers to Gerald Winrod

Gerald Burton Winrod (March 7, 1900 – November 11, 1957) was an American antisemitic evangelist, author, and political activist. He was charged with sedition during World War II, charges were later dropped.

Biography

He was born on March 7, 19 ...

's new journal, ''The Revealer,'' received a copy; fundamentalist

Fundamentalism is a tendency among certain groups and individuals that is characterized by the application of a strict literal interpretation to scriptures, dogmas, or ideologies, along with a strong belief in the importance of distinguishi ...

preacher W. B. Riley, president of the Northwest Bible Training School, claimed he had given away hundreds of copies; and it was advertised and sold by the Moody Bible Institute. It was endorsed by officials in the DAR and the American Legion. Copies were bought by the Pinkerton Detective Agency

Pinkerton is a private security guard and detective agency established around 1850 in the United States by Scottish-born cooper Allan Pinkerton and Chicago attorney Edward Rucker as the North-Western Police Agency, which later became Pinkerton ...

, the New York Police Department, the Chicago Police Department, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

. A Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

arms manufacturer bought and distributed 150 copies, and a tear gas

Tear gas, also known as a lachrymator agent or lachrymator (), sometimes colloquially known as "mace" after the early commercial aerosol, is a chemical weapon that stimulates the nerves of the lacrimal gland in the eye to produce tears. In ...

manufacturer bought 1,500 copies, which it distributed to the Standard Oil Company, the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

, and hundreds of police departments.

In 1935, Dilling returned to her ''alma mater'' to accuse such people as university president Robert Maynard Hutchins

Robert Maynard Hutchins (January 17, 1899 – May 14, 1977) was an American educational philosopher. He was president (1929–1945) and chancellor (1945–1951) of the University of Chicago, and earlier dean of Yale Law School (1927–1929). His& ...

, educational reformer John Dewey, activist Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

, and Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Senator William Borah

William Edgar Borah (June 29, 1865 – January 19, 1940) was an outspoken Republican United States Senator, one of the best-known figures in Idaho's history. A progressive who served from 1907 until his death in 1940, Borah is often co ...

of being communist sympathizers. Retail tycoon Charles R. Walgreen asked for her help to obtain a public hearing after his niece complained that professors at the university were communists. They demanded the closure of the university. The Illinois legislature

The Illinois General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. state of Illinois. It has two chambers, the Illinois House of Representatives and the Illinois Senate. The General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 18 ...

convened to discuss the matter, ultimately deciding that the claims were unfounded. Dilling delivered a frenetic half-hour speech at the Illinois General Assembly, with calls from the audience to "kill every communist". She declared, "It is certain that the University of Chicago is diseased with Communism and that its contagion is a menace to the community and the Nation."

Dilling's next book, ''The Roosevelt Red Record and Its Background,'' published two weeks before the 1936 presidential election, was less successful. Like much of her later writing, it was largely a disjointed series of quotations. President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

's "Jew Deal" (as Dilling was calling the New Deal) was already a central theme of ''The Red Network,'' and it was already being debated elsewhere. Dilling later claimed that the House Un-American Activities Committee was founded largely thanks to her two books. She wrote a pamphlet attacking Borah, entitled ''Borah: "Borer from Within" the G.O.P.'', fearing that if he won the presidential nomination voters would be forced to choose between two communists. She distributed 5,000 copies at the Republican National Convention, and claimed credit for his defeat.Erickson, 480–482Frederickson 833

In 1938, Dilling founded the Patriotic Research Bureau, a vast archive in Chicago with a staff of "Christian women and girls" from the Moody Bible Institute. She began regular publication of the ''Patriotic Research Bulletin,'' a newsletter outlining her political and personal views, which she mailed free of charge to her supporters. Editions were often 25 to 30 pages long, with a youthful photograph of the author on the cover conveying a personal touch. The masthead of early issues reads: "Patriotic Research Bureau. For the defense of Christianity and Americanism".

Dilling was paid $5,000 in 1939 by industrialist Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that ...

to investigate communism at the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

. As well as distributing his antisemitic newspaper ''The Dearborn Independent

''The Dearborn Independent'', also known as ''The Ford International Weekly'', was a weekly newspaper established in 1901, and published by Henry Ford from 1919 through 1927. The paper reached a circulation of 900,000 by 1925, second only to the ...

'' during the 1920s, Ford was a financial supporter of dozens of antisemitic propagandists. Dilling discovered hundreds of books at the university library

An academic library is a library that is attached to a higher education institution and serves two complementary purposes: to support the curriculum and the research of the university faculty and students. It is unknown how many academic librar ...

written by "radicals". Her 96-page report stated that the university was "typical of those American colleges which have permitted Marxist-bitten, professional theorists to inoculate wholesome American youths with their collectivist propaganda." She reached a similar conclusion when the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce

The Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce is Southern California's largest not-for-profit business federation, representing the interests of more than 235,000 businesses in L.A. County, more than 1,400 member companies and more than 722,430 employ ...

paid her to investigate UCLA

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the California ...

, and when she investigated her children's universities, Cornell

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach a ...

and Northwestern.

In 1940, hoping to influence the presidential election

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The pre ...

, Dilling published ''The Octopus,'' setting out her theories of Jewish Communism. The book was published under the pseudonym "Rev. Frank Woodruff Johnson". Avedis Derounian reported Dilling claiming that "The Jews can never prove that I'm anti-Semitic, I'm too clever for them." Her husband feared that allegations of antisemitism would damage his law practice. She admitted that she was the author at her divorce trial in 1942. She explained that she wrote the book as a response to B'nai B'rith

B'nai B'rith International (, from he, בְּנֵי בְּרִית, translit=b'né brit, lit=Children of the Covenant) is a Jewish service organization. B'nai B'rith states that it is committed to the security and continuity of the Jewish peo ...

. She stated: "It airs their dirty lying attempts to shut every Christian mouth and prevent anyone from getting a fair trial in this country" (for which she was cited for contempt

Contempt is a pattern of attitudes and behaviour, often towards an individual or a group, but sometimes towards an ideology, which has the characteristics of disgust and anger.

The word originated in 1393 in Old French contempt, contemps, ...

).

Isolationism

Dilling was a central figure in a mass movement ofisolationist

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entan ...

women's groups, which opposed US involvement in World War II from a " maternalist" perspective. The membership of these groups in 1941 was between one and six million.Erickson 485 According to historian Kari Frederickson: "They argued that war was the antithesis of nurturant motherhood, and that as women they had a particular stake in preventing American involvement in the European conflict. ... they intertwined their maternalist arguments with appeals that were right-wing, anti-Roosevelt, anti-British, anti-communist and anti-Semitic."

The movement was strongest in the Midwest, a conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

stronghold with a culture of antisemitism, which had long resented the political dominance of the East Coast. Chicago was the base of far-right activists Charles E. Coughlin, Gerald L. K. Smith

Gerald Lyman Kenneth Smith (February 27, 1898 – April 15, 1976) was an American clergyman, politician and organizer known for his populist and far-right demagoguery. A leader of the populist Share Our Wealth movement during the Great Depressio ...

and Lyrl Clark Van Hyning, as well as the America First Committee

The America First Committee (AFC) was the foremost United States isolationist pressure group against American entry into World War II. Launched in September 1940, it surpassed 800,000 members in 450 chapters at its peak. The AFC principally supp ...

, which had 850,000 members by 1941. Dilling spoke at America First meetings, and was involved in the founding of Van Hyning's "We the Mothers Mobilize for America", a highly active group with 150,000 members who were tasked with infiltrating other organizations. The ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television a ...

'', the newspaper with the highest circulation in the region, was strongly isolationist. It treated Dilling as a trusted expert on anti-communism and continued to support her after she was charged with sedition.

In early 1941, when the movement was at its height, Dilling spoke at rallies in Chicago and other cities in the Midwest, and recruited a group to coordinate her efforts to oppose Lend-Lease, the "Mothers' Crusade to Defeat H. R. 1776". Hundreds of these activists picketed the Capitol

A capitol, named after the Capitoline Hill in Rome, is usually a legislative building where a legislature meets and makes laws for its respective political entity.

Specific capitols include:

* United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.

* Numerous ...

for two weeks in February 1941. Dilling was arrested when she led a sit-down strike with at least 25 other protesters in the corridor outside the office of 84-year-old Senator Carter Glass

Carter Glass (January 4, 1858 – May 28, 1946) was an American newspaper publisher and Democratic politician from Lynchburg, Virginia. He represented Virginia in both houses of Congress and served as the United States Secretary of the Treas ...

. After a sensational trial lasting six days, she wept as she was found guilty of disorderly conduct

Disorderly conduct is a crime in most jurisdictions in the United States, the People's Republic of China, and Taiwan. Typically, "disorderly conduct" makes it a crime to be drunk in public, to " disturb the peace", or to loiter in certain are ...

and fined $25. Glass called for the FBI to investigate the women's groups, and stated in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' on March 7 that the women had caused "a noisy disorder of which any self-respecting fishwife would be ashamed. I likewise believe that it would be pertinent to inquire whether they are mothers. For the sake of the race, I devoutly hope not." Isolationist leader Cathrine Curtis

Cathrine Curtis (1889 - 1955) was an American actress, film producer, investor, and radio personality. She was one of the first female film producers and was also a political organizer noted for her far-right views.

Early life

Curtis was bor ...

believed that the image of the Mothers' movement had been wrecked, and privately criticised Dilling's "hoodlum" tactics as "communistic" and "un-womanly".

Many of the women's groups continued to oppose the war after the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

, unlike their allies, the America First Committee. Dilling campaigned for Thomas E. Dewey in the 1944 presidential election, although she accused him of "fawning at the feet of international Jewry".Jeansonne 89 Her political activity decreased as a result of her highly publicized divorce trial, beginning in February 1942, during which dozens of fist fights broke out, involving both men and women, and Dilling received three citations for contempt. The judge, Rudolph Desort, said that he feared he would suffer "a nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

" during the four-month trial.

A grand jury, convened in 1941 to investigate fascist propaganda, called several women's leaders to testify, including Dilling, Curtis and Van Hyning. Roosevelt prevailed upon Attorney General Francis Biddle

Francis Beverley Biddle (May 9, 1886 – October 4, 1968) was an American lawyer and judge who was the United States Attorney General during World War II. He also served as the primary American judge during the postwar Nuremberg Trials as well a ...

to launch a prosecution, and on July 21, 1942, Dilling and 27 other anti-war activists were indicted on two counts of conspiracy to cause insubordination of the military in peacetime and wartime. The case was the main part of a government campaign against domestic subversion, which historian Leo P. Ribuffo labelled "The Brown Scare". The charges and list of defendants were extended in January 1943. The charges were again extended in January 1944. The judge, Edward C. Eicher, suffered a fatal heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

on November 29, 1944. Federal judge James M. Proctor declared a mistrial

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, ...

. The charges were dismissed by federal judge Bolitha Laws on November 22, 1946, after the government had failed to present any compelling new evidence of a German conspiracy. Biddle later called the proceedings "a dreary farce".

Post-war publications

Following the 1946 trial dismissal, Dilling continued to publish the ''Patriotic Research Bulletin'', and in 1964, she published ''The Plot Against Christianity''. The book "reveals the satanic hatred of Christ and Christians responsible for their mass murder, torture and slave labour in all Iron Curtain countries – all of which are ruled byTalmudist

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the center ...

s". After her death, it was retitled ''The Jewish Religion: Its Influence Today''.

Media references

*A character based on Dilling named "Adelaide Tarr Gimmitch" appears in the novel ''

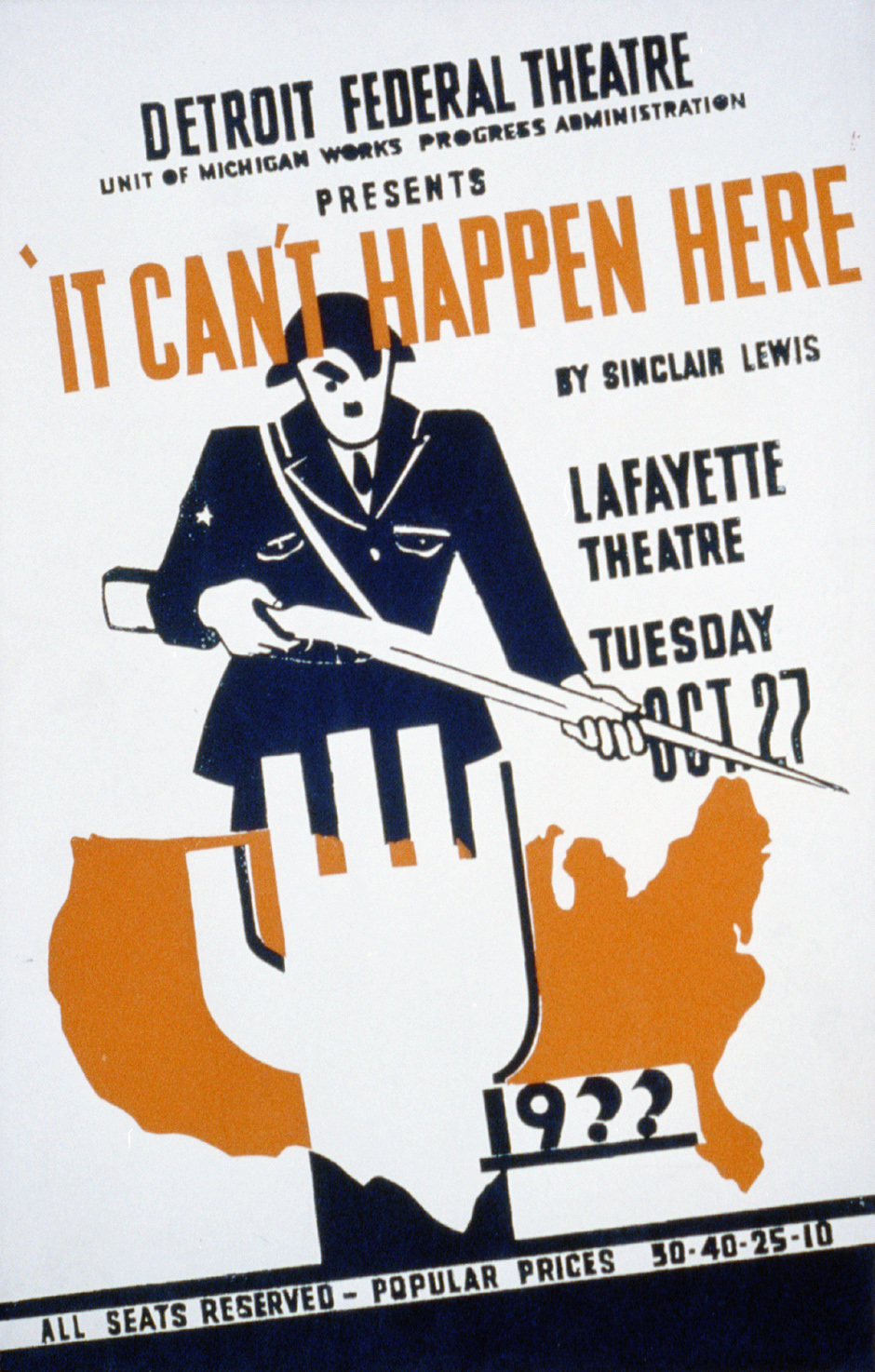

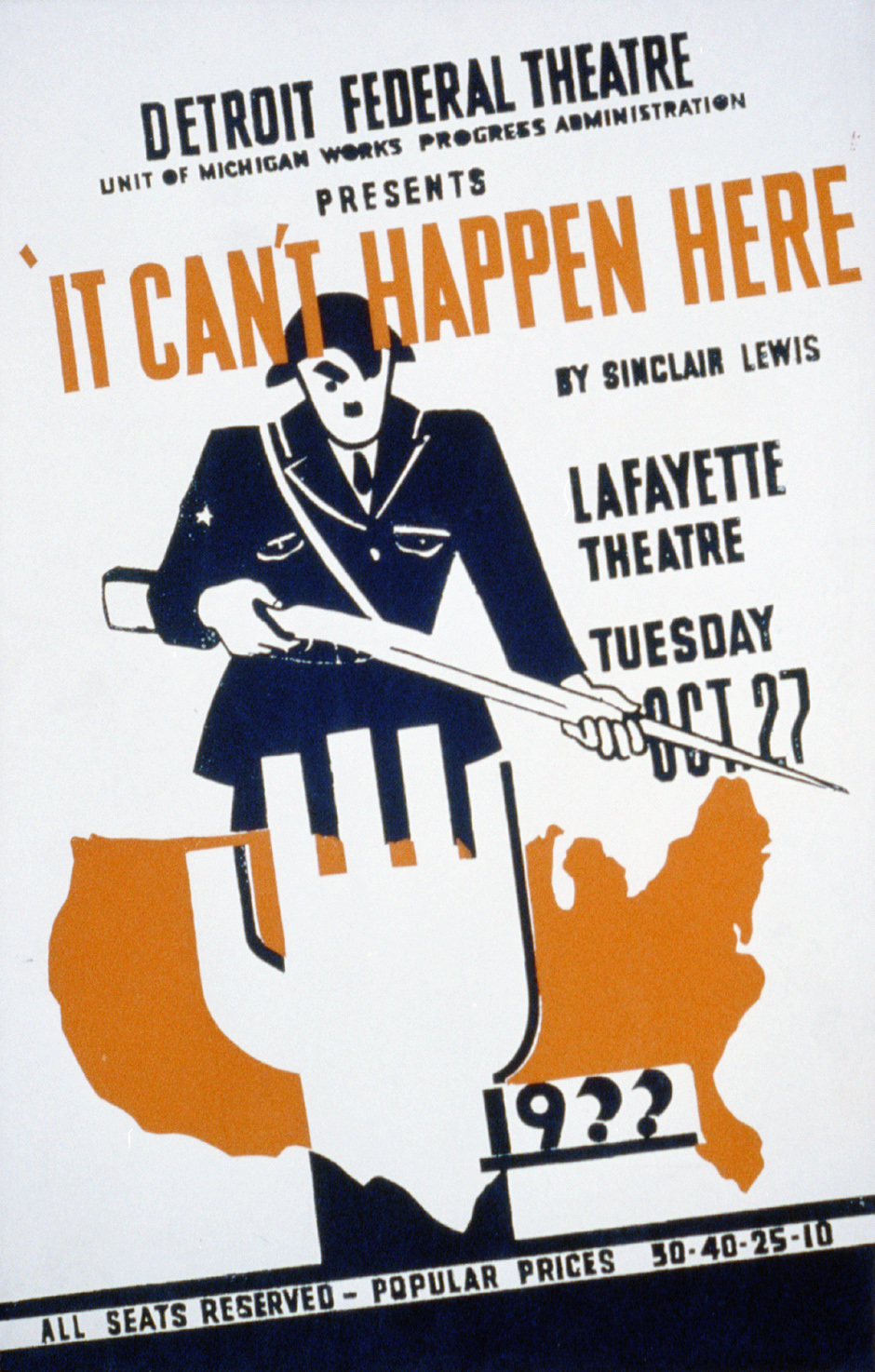

*A character based on Dilling named "Adelaide Tarr Gimmitch" appears in the novel ''It Can't Happen Here

''It Can't Happen Here'' is a 1935 dystopian political novel by American author Sinclair Lewis. It describes the rise of a United States dictator similar to how Adolf Hitler gained power. The novel was adapted into a play by Lewis and John C. Mo ...

'' (1935) by Sinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American writer and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was ...

. The book describes a fascist takeover in the US.

*"Who then, is Mrs Dilling? Upon what strange meat has she been fed that she hath grown so great: And what inspired her, she who might have taken up knitting or petunia-growing, to adopt as her hobby the deliberate and sometimes hasty criticism of men and women she has never seen." — Harry Thornton Moore, "The Lady Patriot's Book", ''The New Republic'', January 8, 1936

*"To see the lady in action, screaming and leaping and ripping along at breakneck speed, is to see certain symptoms of simple hysteria on the loose." — Milton S. Mayer, "Mrs. Dilling: Lady of the Red Network", ''American Mercury

''The American Mercury'' was an American magazine published from 1924Staff (Dec. 31, 1923)"Bichloride of Mercury."''Time''. to 1981. It was founded as the brainchild of H. L. Mencken and drama critic George Jean Nathan. The magazine featured wri ...

'', July 1939Erickson, 273

*"I have rarely seen hatred take complete possession of a woman's face as when Elizabeth Dilling stormed around the corridors shouting. She seemed like a woman pursued by the furies. What she did not know was that the furies were not outside her, but in her own mind." — Max Lerner

Max Lerner (December 20, 1902 – June 5, 1992) was a Russian Empire-born American journalist and educator known for his controversial syndicated column.

Background

Maxwell Alan Lerner was born on December 20, 1902 in Minsk, in the Russian Empi ...

describing an encounter in 1941, '' PM'', 1943/44Johnson, 1044

Works

According to the Library of Congress records, Dilling self-published the original printings of her books inKenilworth, Illinois

Kenilworth is a village in Cook County, Illinois, United States, north of downtown Chicago. As of the 2020 census it had a population of 2,514. It is the newest of the nine suburban North Shore communities bordering Lake Michigan, and is one o ...

, then some 20 miles north of downtown Chicago. They were later republished by printing houses throughout the country, such as the Elizabeth Dilling Foundation in the 1960s, Arno Press

Arno Press was a Manhattan-based publishing house founded by Arnold Zohn in 1963, specializing in reprinting rare and long out-of-print materials.

History

Zohn served 48 missions on a bomber crew during World War II, and when he returned home he ...

in the 1970s and Sons of Liberty in the 1980s.

Books

''The Red Network, A "Who's Who" and Handbook of Radicalism for Patriots''

(1934, 1935, 1936, 1977) * ''"Lady Patriot" Replies'' (1936)

''The Roosevelt Red Record and Its Background''

(1936) * ''Dare We Oppose Red Treason?'' (1937). . * ''The Red Betrayal of the Churches'' (1938). .

''The Octopus''

by Rev. Frank Woodruff Johnson seud.(Oct. 1940; Sons of Liberty, 1985, 1986) * ''The Plot Against Christianity'' (1964) **Republished a

''The Jewish Religion: Its Influence Today''.

See also

*Blair Coan

Blair Coan (also written Coán) (1883-1939) was an American government agent under US Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty and anti-communist, known for his book ''The Red Web'' (1925) on early Soviet penetration in the US government, singling out ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * *Dye, Amy (2009)"The Powers of Perception: An Intimate Connection with Elizabeth Dilling"

East Tennessee State University. * * * *. * * * *Smith, Jason Scott (2014). A Concise History of the New Deal. 1st ed. New York: Cambridge University Press. Cambridge Books Online. Web. April 7, 2016. *Walker, Samuel (2012). Presidents and Civil Liberties from Wilson to Obama. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cambridge Books Online. Web. April 6, 2016.

External links

''Prints and Photographs Online Catalog'', Library of Congress

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dilling, Elizabeth 1894 births 1966 deaths People from Chicago American people of British descent American Episcopalians American women civilians in World War II American political writers Anti–World War II activists Anti-communist propagandists Antisemitic publications University of Chicago alumni American anti-war activists Old Right (United States) Place of death missing American conspiracy theorists Pseudonymous women writers 20th-century pseudonymous writers History of United States isolationism American women non-fiction writers Far-right politics in the United States American anti-communists Activists from Illinois