Dynamics of the celestial spheres on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ancient, medieval and

Ancient, medieval and

Ancient, medieval and

Ancient, medieval and Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

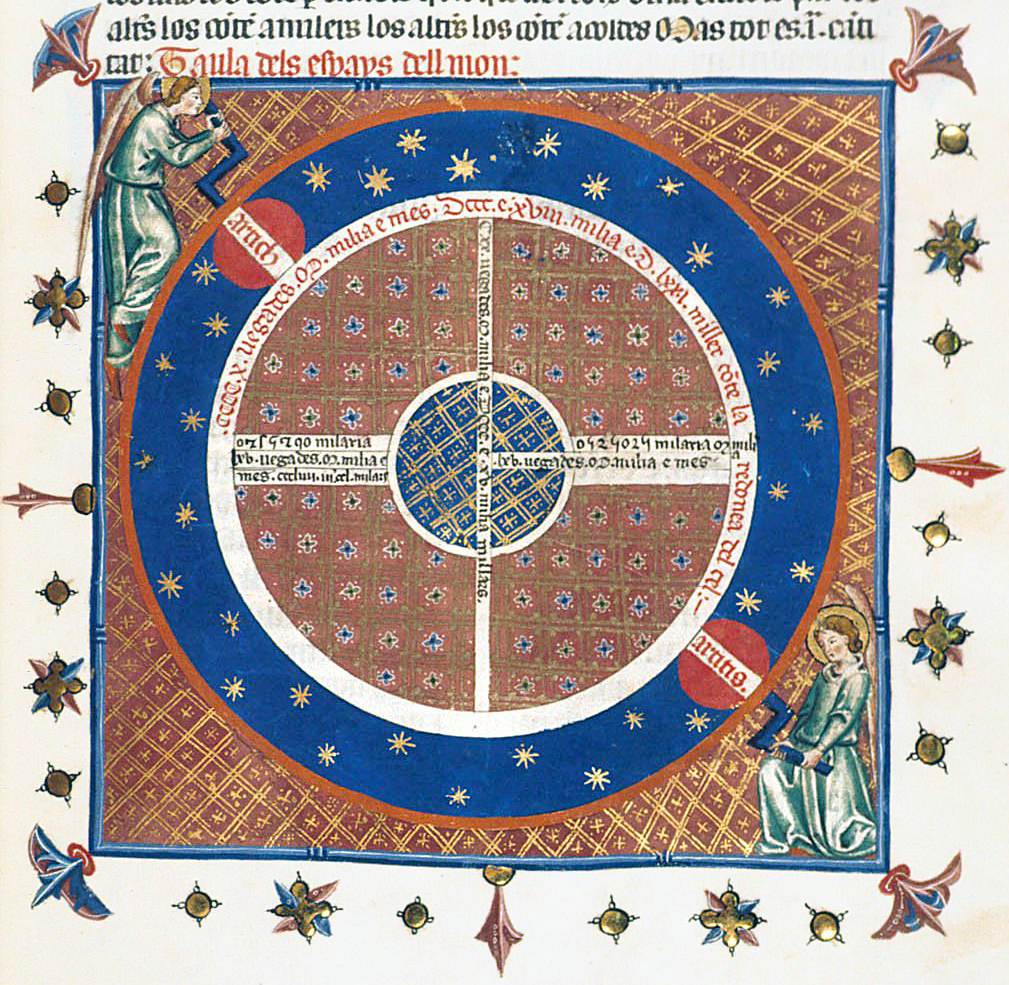

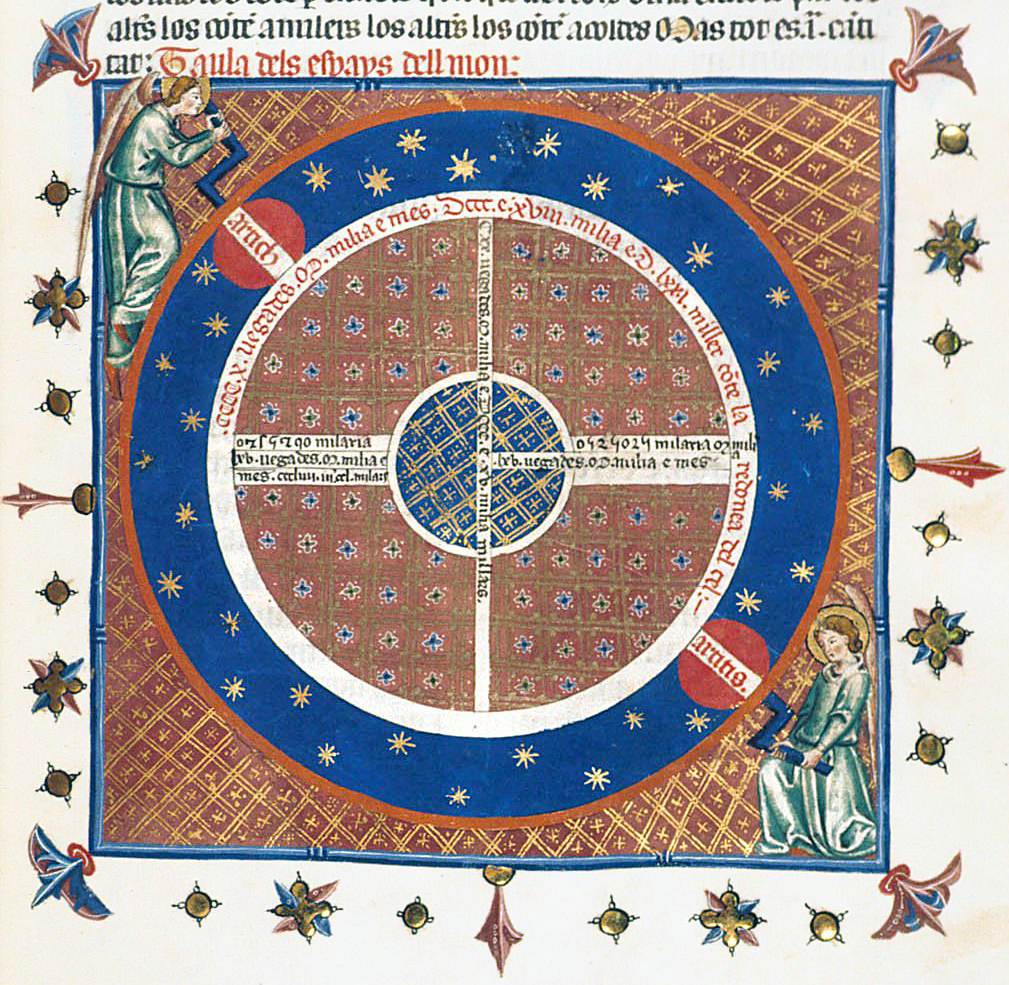

astronomers and philosophers developed many different theories about the dynamics of the celestial spheres. They explained the motions of the various nested spheres in terms of the materials of which they were made, external movers such as celestial intelligences, and internal movers such as motive souls or impressed forces. Most of these models were qualitative, although a few of them incorporated quantitative analyses that related speed, motive force and resistance.

The celestial material and its natural motions

In considering the physics of the celestial spheres, scholars followed two different views about the material composition of the celestial spheres. ForPlato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, the celestial regions were made "mostly out of fire" on account of fire's mobility. Later Platonists, such as Plotinus

Plotinus (; grc-gre, Πλωτῖνος, ''Plōtînos''; – 270 CE) was a philosopher in the Hellenistic tradition, born and raised in Roman Egypt. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of Neoplatonism. His teacher wa ...

, maintained that although fire moves naturally upward in a straight line toward its natural place at the periphery of the universe, when it arrived there, it would either rest or move naturally in a circle. This account was compatible with Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

's meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

of a fiery region in the upper air, dragged along underneath the circular motion of the lunar sphere. For Aristotle, however, the spheres themselves were made entirely of a special fifth element, ''Aether'' (Αἰθήρ), the bright, untainted upper atmosphere in which the gods dwell, as distinct from the dense lower atmosphere, ''Aer'' (Ἀήρ). While the four terrestrial elements (earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's sur ...

, water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as ...

, air and fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a material (the fuel) in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction products.

At a certain point in the combustion reaction, called the ignition point, flames ...

) gave rise to the generation and corruption of natural substances by their mutual transformations, aether was unchanging, moving always with a uniform circular motion that was uniquely suited to the celestial spheres, which were eternal. Earth and water had a natural heaviness (''gravitas''), which they expressed by moving downward toward the center of the universe. Fire and air had a natural lightness (''levitas''), such that they moved upward, away from the center. Aether, being neither heavy nor light, moved naturally around the center.

The causes of celestial motion

As early as Plato, philosophers considered the heavens to be moved by immaterial agents. Plato believed the cause to be a world-soul, created according to mathematical principles, which governed the daily motion of the heavens (the motion of the Same) and the opposed motions of theplanets

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a youn ...

along the zodiac

The zodiac is a belt-shaped region of the sky that extends approximately 8° north or south (as measured in celestial latitude) of the ecliptic, the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year. The pa ...

(the motion of the Different). Aristotle proposed the existence of divine unmoved mover

The unmoved mover ( grc, ὃ οὐ κινούμενον κινεῖ, ho ou kinoúmenon kineî, that which moves without being moved) or prime mover ( la, primum movens) is a concept advanced by Aristotle as a primary cause (or first uncaused cau ...

s which act as final causes; the celestial spheres mimic the movers, as best they could, by moving with uniform circular motion. In his ''Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

'', Aristotle maintained that an individual unmoved mover would be required to insure each individual motion in the heavens. While stipulating that the number of spheres, and thus gods, is subject to revision by astronomers, he estimated the total as 47 or 55, depending on whether one followed the model of Eudoxus or Callippus

Callippus (; grc, Κάλλιππος; c. 370 BC – c. 300 BC) was a Greek astronomer and mathematician.

Biography

Callippus was born at Cyzicus, and studied under Eudoxus of Cnidus at the Academy of Plato. He also worked with Aristotle at ...

. In ''On the Heavens

''On the Heavens'' (Greek: ''Περὶ οὐρανοῦ''; Latin: ''De Caelo'' or ''De Caelo et Mundo'') is Aristotle's chief cosmological treatise: written in 350 BC, it contains his astronomical theory and his ideas on the concrete workings ...

'', Aristotle presented an alternate view of eternal circular motion as moving itself, in the manner of Plato's world-soul, which lent support to three principles of celestial motion: an internal soul, an external unmoved mover, and the celestial material (aether).

Later Greek interpreters

In his ''Planetary Hypotheses'',Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

(c.90–168) rejected the Aristotelian concept of an external prime mover, maintaining instead that the planets have souls and move themselves with a voluntary motion. Each planet sends out motive emissions that direct its own motion and the motions of the epicycle and deferent that make up its system, just as a bird sends out emissions to its nerves that direct the motions of its feet and wings.

John Philoponus (490–570) considered that the heavens were made of fire, not of aether, yet maintained that circular motion is one of the two natural motions of fire. In a theological work, ''On the Creation of the World'' (''De opificio mundi''), he denied that the heavens are moved by either a soul or by angels, proposing that "it is not impossible that God, who created all these things, imparted a motive force to the Moon, the Sun, and other stars – just as the inclination to heavy and light bodies, and the movements due to the internal soul to all living beings – in order that the angels do not move them by force." This is interpreted as an application of the concept of impetus to the motion of the celestial spheres. In an earlier commentary on Aristotle's ''Physics'', Philoponus compared the innate power or nature that accounts for the rotation of the heavens to the innate power or nature that accounts for the fall of rocks.

Islamic interpreters

The Islamic philosophersal-Farabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a renowned early Isl ...

(c.872–c.950) and Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic ...

(c.980–1037), following Plotinus, maintained that Aristotle's movers, called intelligences, came into being through a series of emanations beginning with God. A first intelligence emanated from God, and from the first intelligence emanated a sphere, its soul, and a second intelligence. The process continued down through the celestial spheres until the sphere of the Moon, its soul, and a final intelligence. They considered that each sphere was moved continually by its soul, seeking to emulate the perfection of its intelligence.Wolfson 1958, pp. 243–4. Avicenna maintained that besides an intelligence and its soul, each sphere was also moved by a natural inclination (''mayl'').

An interpreter of Aristotle from Muslim Spain, al-Bitruji

Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji () (also spelled Nur al-Din Ibn Ishaq al-Betrugi and Abu Ishâk ibn al-Bitrogi) (known in the West by the Latinized name of Alpetragius) (died c. 1204) was an Iberian-Arab astronomer and a Qadi in al-Andalus. Al-Biṭrūjī ...

(d. c.1024), proposed a radical transformation of astronomy that did away with epicycles and eccentrics, in which the celestial spheres were driven by a single unmoved mover at the periphery of the universe. The spheres thus moved with a "natural nonviolent motion". The mover's power diminished with increasing distance from the periphery so that the lower spheres lagged behind in their daily motion around the Earth; this power reached even as far as the sphere of water, producing the tides

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables c ...

.

More influential for later Christian thinkers were the teachings of Averroes (1126–1198), who agreed with Avicenna that the intelligences and souls combine to move the spheres but rejected his concept of emanation. Considering how the soul acts, he maintained that the soul moves its sphere without effort, for the celestial material has no tendency to a contrary motion.

Later in the century, the mutakallim Adud al-Din al-Iji (1281–1355) rejected the principle of uniform and circular motion, following the Ash'ari

Ashʿarī theology or Ashʿarism (; ar, الأشعرية: ) is one of the main Sunnī schools of Islamic theology, founded by the Muslim scholar, Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer, and scholastic theologian Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī in th ...

doctrine of atomism

Atomism (from Greek , ''atomon'', i.e. "uncuttable, indivisible") is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its atom ...

, which maintained that all physical effects were caused directly by God's will rather than by natural causes. He maintained that the celestial spheres were "imaginary things" and "more tenuous than a spider's web".pp. 55–57 of His views were challenged by al-Jurjani (1339–1413), who argued that even if the celestial spheres "do not have an external reality, yet they are things that are correctly imagined and correspond to what xistsin actuality".

Medieval Western Europe

In theEarly Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

, Plato's picture of the heavens was dominant among European philosophers, which led Christian thinkers to question the role and nature of the world-soul. With the recovery of Aristotle

The "Recovery of Aristotle" (or Rediscovery) refers to the copying and translating of most of Aristotle's tractates from Greek or Arabic text into Latin, during the Middle Ages, of the Latin West.

''Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, an ...

's works in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Aristotle's views supplanted the earlier Platonism, and a new set of questions regarding the relationships of the unmoved movers to the spheres and to God emerged.

In the early phases of the Western recovery of Aristotle

The "Recovery of Aristotle" (or Rediscovery) refers to the copying and translating of most of Aristotle's tractates from Greek or Arabic text into Latin, during the Middle Ages, of the Latin West.

''Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, an ...

, Robert Grosseteste (c.1175–1253), influenced by medieval Platonism and by the astronomy of al-Bitruji, rejected the idea that the heavens are moved by either souls or intelligences. Adam Marsh

Adam Marsh (Adam de Marisco; c. 120018 November 1259) was an English Franciscan, scholar and theologian. Marsh became, after Robert Grosseteste, "...the most eminent master of England."

Biography

He was born about 1200 in the diocese of Bath, a ...

's (c.1200–1259) treatise ''On the Ebb and Flow of the Sea'', which was formerly attributed to Grosseteste, maintained al-Bitruji's opinion that the celestial spheres and the seas are moved by a peripheral mover whose motion weakens with distance.

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, Dominican Order, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino, Italy, Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest who was an influential List of Catholic philo ...

(c.1225–1274), following Avicenna, interpreted Aristotle to mean that there were two immaterial substances responsible for the motion of each celestial sphere, a soul that was an integral part of its sphere, and an intelligence that was separate from its sphere. The soul shares the motion of its sphere and causes the sphere to move through its love and desire for the unmoved separate intelligence. Avicenna, al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian poly ...

, Moses Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah s ...

, and most Christian scholastic philosophers identified Aristotle's intelligences with the angels

In various theistic religious traditions an angel is a supernatural spiritual being who serves God.

Abrahamic religions often depict angels as benevolent celestial intermediaries between God (or Heaven) and humanity. Other roles incl ...

of revelation, thereby associating an angel with each of the spheres. Moreover, Aquinas rejected the idea that celestial bodies are moved by an internal nature, similar to the heaviness and lightness that moves terrestrial bodies. Attributing souls to the spheres was theologically controversial, as that could make them animals. After the Condemnations of 1277, most philosophers came to reject the idea that the celestial spheres had souls.

Robert Kilwardby (c. 1215–1279) discussed three alternative explanations of the motions of the celestial spheres, rejecting the views that celestial bodies are animated and are moved by their own spirits or souls, or that the celestial bodies are moved by angelic spirits, which govern and move them. He maintained, instead, that "celestial bodies are moved by their own natural inclinations similar to weight". Just as heavy bodies are naturally moved by their own weight, which is an intrinsic active principle, so the celestial bodies are naturally moved by a similar intrinsic principle. Since the heavens are spherical, the only motion that could be natural to them is rotation. Kilwardby's idea had been earlier held by another Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

scholar, John Blund

John Blund () was an English scholastic philosopher, known for his work on the nature of the soul, the Tractatus de anima, one of the first works of western philosophy to make use of the recently translated ''De Anima'' by Aristotle and especi ...

(c. 1175–1248).

In two slightly different discussions, John Buridan

Jean Buridan (; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14th-century French philosopher.

Buridan was a teacher in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career who focused in particular on logic and the wor ...

(c.1295–1358) suggested that when God created the celestial spheres, he began to move them, impressing in them a circular impetus that would be neither corrupted nor diminished, since there was neither an inclination to other movements nor any resistance in the celestial region. He noted that this would allow God to rest on the seventh day, but he left the matter to be resolved by the theologians.

Nicole Oresme (c.1323-1382) explained the motion of the spheres in traditional terms of the action of intelligences but noted that, contrary to Aristotle, some intelligences are moved; for example, the intelligence that moves the Moon's epicycle shares the motion of the lunar orb in which the epicycle is embedded. He related the spheres' motions to the proportion of motive power to resistance that was impressed in each sphere when God created the heavens. In discussing the relation of the moving power of the intelligence, the resistance of the sphere, and the circular velocity

Velocity is the directional speed of an object in motion as an indication of its rate of change in position as observed from a particular frame of reference and as measured by a particular standard of time (e.g. northbound). Velocity i ...

, he said "this ratio ought not to be called a ratio of force to resistance except by analogy, because an intelligence moves by will alone ... and the heavens do not resist it."

According to Grant, except for Oresme, scholastic thinkers did not consider the force-resistance model to be properly applicable to the motion of celestial bodies, although some, such as Bartholomeus Amicus, thought analogically in terms of force and resistance. By the end of the Middle Ages it was the common opinion among philosophers that the celestial bodies were moved by external intelligences, or angels, and not by some kind of an internal mover.

The movers and Copernicanism

AlthoughNicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulat ...

(1473–1543) transformed Ptolemaic astronomy and Aristotelian cosmology by moving the Earth from the center of the universe, he retained both the traditional model of the celestial spheres and the medieval Aristotelian views of the causes of its motion. Copernicus follows Aristotle to maintain that circular motion is natural to the form of a sphere. However, he also appears to have accepted the traditional philosophical belief that the spheres are moved by an external mover.

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

's (1571–1630) cosmology eliminated the celestial spheres, but he held that the planets were moved both by an external motive power, which he located in the Sun, and a motive soul associated with each planet. In an early manuscript discussing the motion of Mars, Kepler considered the Sun to cause the circular motion of the planet. He then attributed the inward and outward motion of the planet, which transforms its overall motion from circular to oval, to a moving soul in the planet since the motion is "not a natural motion, but more of an animate one". In various writings, Kepler often attributed a kind of intelligence to the inborn motive faculties associated with the stars.

In the aftermath of Copernicanism the planets came to be seen as bodies moving freely through a very subtle aethereal medium. Although many scholastics continued to maintain that intelligences were the celestial movers, they now associated the intelligences with the planets themselves, rather than with the celestial spheres.Grant 1994, pp. 544–5.

See also

* Christian angelic hierarchyNotes

References

Primary sources

* Aristotle, ''Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

''

* Aristotle, ''On the heavens

''On the Heavens'' (Greek: ''Περὶ οὐρανοῦ''; Latin: ''De Caelo'' or ''De Caelo et Mundo'') is Aristotle's chief cosmological treatise: written in 350 BC, it contains his astronomical theory and his ideas on the concrete workings ...

''

* Plato, '' Timaeus''

Secondary sources

* * * * * * * * * {{refend Ancient Greek astronomy Early scientific cosmologies Physical cosmology