Dorothy Garrod on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Dorothy Annie Elizabeth Garrod, CBE, FBA (5 May 1892 – 18 December 1968) was an English

On her family's return to England, where they settled in

On her family's return to England, where they settled in

One vision, one faith, one woman: Dorothy Garrod and the crystallisation of prehistory

In R. Hosfield, F. F. Wenban-Smith and M. Pope (eds): Great Prehistorians: 150 Years of Palaeolithic Research, 1859–2009 (Special Volume 30 of ''Lithics: The Journal of the Lithic Studies Society''):x–y. Lithic Studies Society, London. In 1928 she headed an expedition through South After holding a number of academic positions, including Newnham College's Director of Studies for Archaeology and Anthropology, she became the Disney Professor of Archaeology at Cambridge on 6 May 1939, a post she held until 1952. Her appointment was greeted with excitement by women students and a "college feast" was held in her honour at Newnham, in which every dish was named after an archaeological item. In addition, the ''Cambridge Review'' reported, "The election of a woman to the Disney Professorship of Archaeology is an immense step forward towards complete equality between men and women in the University." Gender equality at the University of Cambridge at the time was still remote: as a woman, Garrod could not be a full member of the University, so that she was excluded from speaking or voting on University matters. This continued to apply until 1948, when women became full members of the University.

From 1941 to 1945, Garrod took leave of absence from the university and served in the

After holding a number of academic positions, including Newnham College's Director of Studies for Archaeology and Anthropology, she became the Disney Professor of Archaeology at Cambridge on 6 May 1939, a post she held until 1952. Her appointment was greeted with excitement by women students and a "college feast" was held in her honour at Newnham, in which every dish was named after an archaeological item. In addition, the ''Cambridge Review'' reported, "The election of a woman to the Disney Professorship of Archaeology is an immense step forward towards complete equality between men and women in the University." Gender equality at the University of Cambridge at the time was still remote: as a woman, Garrod could not be a full member of the University, so that she was excluded from speaking or voting on University matters. This continued to apply until 1948, when women became full members of the University.

From 1941 to 1945, Garrod took leave of absence from the university and served in the

Retrieved 13 November 2019.

/ref>

"From 'small, dark and alive' to 'cripplingly shy': Dorothy Garrod as the first woman Professor at Cambridge."

*Pamela Jane Smith et al., (1997), "Dorothy Garrod in Words and Pictures", ''Antiquity'' 71 (272), pp. 265–270

The Dorothy Garrod photographic archive at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford

{{DEFAULTSORT:Garrod, Dorothy 1892 births 1968 deaths 20th-century archaeologists 20th-century English scientists 20th-century English women 20th-century British women scientists English archaeologists Alumni of Newnham College, Cambridge Alumni of the University of Oxford Disney Professors of Archaeology Fellows of the British Academy Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Women's Auxiliary Air Force officers Prehistorians People associated with the Pitt Rivers Museum British women archaeologists British women scientists British scientists Archaeologists of the Near East Natufian culture

archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsca ...

who specialised in the Palaeolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός '' palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

period. She held the position of Disney Professor of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge from 1939 to 1952, and was the first woman to hold a chair at either Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

or Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

.

Early life and education

Garrod was the daughter of the physician Sir Archibald Garrod and Laura Elizabeth Smith, daughter of the surgeon Sir Thomas Smith, 1st Baronet. She was born in Chandos Street, London, and was educated at home. Her first teacher wasIsabel Fry

Isabel Fry (25 March 1869– 26 March 1958) was an English educator and social activist.

Early life

She was one of twins, with her sister Agnes Fry, born to the barrister and judge Sir Edward Fry and his wife Mariabella Hodgkin. They were younge ...

as governess. Garrod recalled Fry teaching her, at age nine, in Harley Street

Harley Street is a street in Marylebone, Central London, which has, since the 19th century housed a large number of private specialists in medicine and surgery. It was named after Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer.

with the daughter of Walter Jessop. She later attended Birklands School in St Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major town on the old Roman ...

.

In 1913, Garrod entered Newnham College, Cambridge

Newnham College is a women's constituent college of the University of Cambridge.

The college was founded in 1871 by a group organising Lectures for Ladies, members of which included philosopher Henry Sidgwick and suffragist campaigner Millic ...

, and in that year became a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

convert. She read history there, completing the course in 1916. She had three brothers, two of whom were killed in action in WW I and the youngest of whom died in France from pneumonia shortly before demobilisation. She undertook war work with the Catholic Women's League

The Catholic Women's League (CWL) is a Roman Catholic lay organisation founded in 1906 by Margaret Fletcher. Originally intended to bring together Catholic women in England, the organization has grown, and may be found in numerous Commonwealth ...

, until she was demobilised in 1919. She then went to Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, where her father was working, and began to take an interest in the local antiquities.

Career

On her family's return to England, where they settled in

On her family's return to England, where they settled in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Garrod read for a graduate diploma in anthropology at the Pitt Rivers Museum

Pitt Rivers Museum is a museum displaying the archaeological and anthropological collections of the University of Oxford in England. The museum is located to the east of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and can only be accessed ...

. There she was taught by Robert Ranulph Marett

Robert Ranulph Marett (13 June 1866 – 18 February 1943) was a British ethnologist and a proponent of the British Evolutionary School of cultural anthropology. Founded by Marett's older colleague, Edward Burnett Tylor, it asserted that mo ...

and received a distinction on graduating in 1921, as one among a small number of female students. She had found an intellectual vocation: the archaeology of the Palaeolithic Age

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός '' palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

. She then studied for two years, 1922 to 1924, with the French prehistorian Abbé Breuil at the Institut de Paleontologie Humaine in Paris.

On completing her studies, Garrod began to excavate in Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

. Following a recommendation from Breuil, she investigated Devil's Tower Cave, which was only 350 metres from Forbes' Quarry, where a Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an Extinction, extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ag ...

skull had been found earlier. Garrod discovered in this cave in 1925, a second important Neanderthal skull now called Gibraltar 2.

In 1926, Garrod published her first academic work, ''The Upper Paleolithic of Britain'', for which she was awarded a B. Sc. degree by the University of Oxford.K. M. Price, 2009One vision, one faith, one woman: Dorothy Garrod and the crystallisation of prehistory

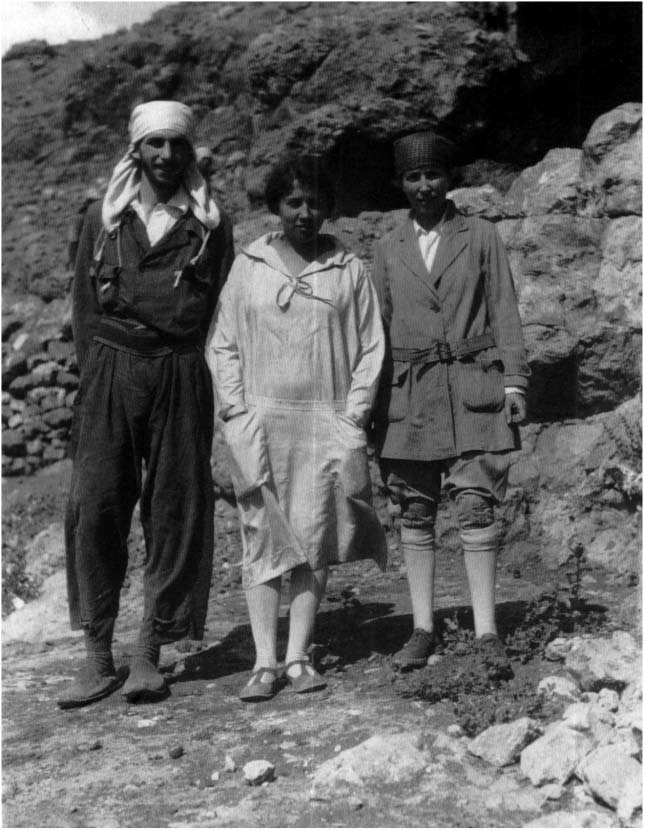

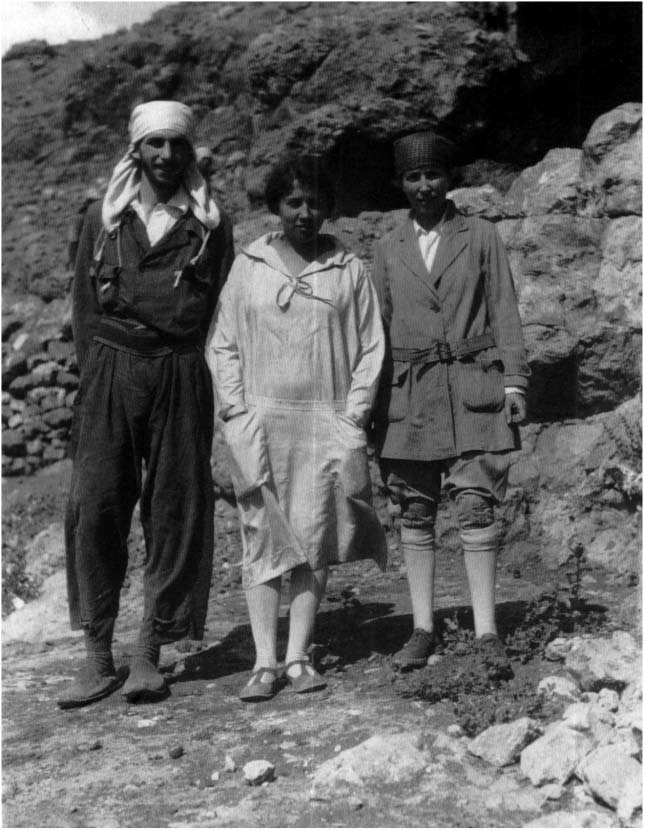

In R. Hosfield, F. F. Wenban-Smith and M. Pope (eds): Great Prehistorians: 150 Years of Palaeolithic Research, 1859–2009 (Special Volume 30 of ''Lithics: The Journal of the Lithic Studies Society''):x–y. Lithic Studies Society, London. In 1928 she headed an expedition through South

Kurdistan

Kurdistan ( ku, کوردستان ,Kurdistan ; lit. "land of the Kurds") or Greater Kurdistan is a roughly defined geo-cultural territory in Western Asia wherein the Kurds form a prominent majority population and the Kurdish culture, languag ...

that led to the excavation of Hazar Merd Cave and Zarzi cave.

In 1929, Garrod was appointed to direct excavations at Wadi el-Mughara at Mount Carmel

Mount Carmel ( he, הַר הַכַּרְמֶל, Har haKarmel; ar, جبل الكرمل, Jabal al-Karmil), also known in Arabic as Mount Mar Elias ( ar, link=no, جبل مار إلياس, Jabal Mār Ilyās, lit=Mount Saint Elias/ Elijah), is a ...

in Mandatory Palestine, as a joint project of the American School of Prehistoric Research and the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. The series of 12 extensive excavations was completed over 22 months. The results established a chronological framework that remains crucial to present understanding of that prehistoric period. Working closely with Dorothea Bate, she demonstrated a long sequence of Lower Palaeolithic, Middle Palaeolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle Pale ...

and Epipalaeolithic

In archaeology, the Epipalaeolithic or Epipaleolithic (sometimes Epi-paleolithic etc.) is a period occurring between the Upper Paleolithic and Neolithic during the Stone Age. Mesolithic also falls between these two periods, and the two are som ...

occupations in the caves of Tabun, El Wad, Es Skhul, Shuqba (Shuqbah) and Kebara Cave

Kebara Cave ( he, מערת כבארה, Me'arat Kebbara, ar, مغارة الكبارة, Mugharat al-Kabara) is a limestone cave locality in Wadi Kebara, situated at above sea level on the western escarpment of the Carmel Range, in the Ramat HaN ...

. She also coined the cultural label for the late Epipalaeolithic Natufian culture

The Natufian culture () is a Late Epipaleolithic archaeological culture of the Levant, dating to around 15,000 to 11,500 years ago. The culture was unusual in that it supported a sedentary or semi-sedentary population even before the introduct ...

(from Wadi an-Natuf

Wadi Natuf (Arabic: وادي الناطوف, ''Wadi al-Natuf'' or ''Wadi en-Natuf''; Hebrew: נחל נטוף) is a wadi in the West Bank, in the north of the Ramallah and al-Bireh Governorate of Palestine. which flows into Israel, eventually flowin ...

, the location of the Shuqba cave

Shuqba cave is an archaeological site near the town of Shuqba in the western Judaean Mountains in the Ramallah and al-Bireh Governorate of the West Bank.

Location

Shuqba cave is located on the northern bank of Wadi en-Natuf. This wadi is a kilo ...

) following her excavations at Es Skhul and El Wad. Her excavations at the cave sites in the Levant were conducted with almost exclusively women workers recruited from local villages. One of these women, Yusra, is credited with the discovery of the Tabun 1 Neanderthal skull. Her excavations were also the first to use aerial photography.

In 1937, Garrod published ''The Stone Age of Mount Carmel,'' considered a ground-breaking work in the field. In 1938, she travelled to Bulgaria and excavated the Palaeolithic cave of Bacho Kiro.

After holding a number of academic positions, including Newnham College's Director of Studies for Archaeology and Anthropology, she became the Disney Professor of Archaeology at Cambridge on 6 May 1939, a post she held until 1952. Her appointment was greeted with excitement by women students and a "college feast" was held in her honour at Newnham, in which every dish was named after an archaeological item. In addition, the ''Cambridge Review'' reported, "The election of a woman to the Disney Professorship of Archaeology is an immense step forward towards complete equality between men and women in the University." Gender equality at the University of Cambridge at the time was still remote: as a woman, Garrod could not be a full member of the University, so that she was excluded from speaking or voting on University matters. This continued to apply until 1948, when women became full members of the University.

From 1941 to 1945, Garrod took leave of absence from the university and served in the

After holding a number of academic positions, including Newnham College's Director of Studies for Archaeology and Anthropology, she became the Disney Professor of Archaeology at Cambridge on 6 May 1939, a post she held until 1952. Her appointment was greeted with excitement by women students and a "college feast" was held in her honour at Newnham, in which every dish was named after an archaeological item. In addition, the ''Cambridge Review'' reported, "The election of a woman to the Disney Professorship of Archaeology is an immense step forward towards complete equality between men and women in the University." Gender equality at the University of Cambridge at the time was still remote: as a woman, Garrod could not be a full member of the University, so that she was excluded from speaking or voting on University matters. This continued to apply until 1948, when women became full members of the University.

From 1941 to 1945, Garrod took leave of absence from the university and served in the Women's Auxiliary Air Force

The Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), whose members were referred to as WAAFs (), was the female auxiliary of the Royal Air Force during World War II. Established in 1939, WAAF numbers exceeded 180,000 at its peak strength in 1943, with over 2 ...

(WAAF) during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. She was based at the RAF Medmenham photographic interpretation unit as a section officer (equivalent in rank to flying officer).

After the war, Garrod returned to her position and made a number of changes to the department, including the introduction of a module of study on world prehistory. Where previously prehistory had been considered particularly French or European, Garrod expanded the subject to a global scale. Garrod also made changes to the structure of archaeology studies, so turning Cambridge into the first British university to offer undergraduate courses in prehistoric archaeology. During the university summer vacations, Garrod travelled to France and excavated at two important sites: Fontéchevade

Fontéchevade is a cave in Charente, France, which contains Palaeolithic remains from 200,000 and 120,000 years ago. The fossils consist of two skull fragments. Unlike Neanderthals and ''Homo sapiens'' of the time, the frontal skull fragment lack ...

cave, with Germaine Henri-Martin, and Angles-sur-l'Anglin

Angles-sur-l'Anglin (, literally ''Angles on the Anglin'') is a commune in the Vienne department in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region in western France. It has been selected as one of the most beautiful villages of France.

The Château d'Angles-s ...

, with Suzanne de St. Mathurin.

Later life

On her retirement in 1952, Garrod moved to France, but continued to research and excavate. In 1958, aged 66, she excavated on the Aadloun headland in Lebanon, with the assistance ofDiana Kirkbride

Diana Victoria Warcup Kirkbride-Helbæk, (22 October 1915 – 13 August 1997) was a British archaeologist who specialised in the prehistory of south-west Asia.

Biography

She attended Wycombe Abbey School in High Wycombe and served in the Women' ...

. The following year she was asked urgently to excavate at Ras El Kelb, as a significant cave had been disturbed by road and rail construction. Henri-Martin and de St. Mathurin assisted Garrod for seven weeks, with the remaining material being removed to the National Museum of Beirut

The National Museum of Beirut ( ar, متحف بيروت الوطنيّ, ''Matḥaf Bayrūt al-waṭanī'' or French: Musée national de Beyrouth) is the principal museum of archaeology in Lebanon. The collection begun after World War I, and the m ...

for more detailed study. She returned to Aadloun again in 1963, with a team of younger archaeologists, but her health began to fail and she was often absent from the sites.

In the summer of 1968, Garrod suffered a stroke while visiting relatives in Cambridge. She died in a nursing home there on 18 December, aged 76.

Diversity and inclusion

Garrod was the first female professor at Cambridge and was instrumental in introducing women to the field of archaeology. On excavations, her crews were usually all or mainly women. She was passionate about supporting locals and their families; her Mount Carmel expedition crew consisted mostly of local Arab women. In 1931, she invited Francis Turville Petre, an openly gay man, to join her excavations of Mount Carmel.Awards and recognition

In 1937, Garrod was awarded Honorary Doctorates from theUniversity of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest- ...

and Boston College

Boston College (BC) is a private Jesuit research university in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. Founded in 1863, the university has more than 9,300 full-time undergraduates and nearly 5,000 graduate students. Although Boston College is classified ...

and a DSc. from the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

. She was elected a Fellow of the British Academy

The British Academy is the United Kingdom's national academy for the humanities and the social sciences.

It was established in 1902 and received its royal charter in the same year. It is now a fellowship of more than 1,000 leading scholars s ...

in 1952, and in 1965 she was awarded the CBE. She felt it was important that archaeologists travel and therefore left money to found the Dorothy Garrod Travel Fund. In 1968 the Society of Antiquaries of London

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Soci ...

presented her with its Gold Medal.

From September 2011 to January 2012, 17 photographs of Garrod's of excavations, friends and mentors were displayed in 'A Pioneer of Prehistory, Dorothy Garrod and the Caves of Mount Carmel' at the Pitt Rivers Museum

Pitt Rivers Museum is a museum displaying the archaeological and anthropological collections of the University of Oxford in England. The museum is located to the east of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, and can only be accessed ...

.

In 2017, Newnham College announced that a new college building will be named after Garrod. In 2019, the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at the University of Cambridge unveiled a new portrait of Garrod by artist Sara Levelle./ref>

See also

*Archaeology of Israel

The archaeology of Israel is the study of the archaeology of the present-day Israel, stretching from prehistory through three millennia of documented history. The ancient Land of Israel was a geographical bridge between the political and cultu ...

References

Further reading

*William Davies and Ruth Charles, eds (1999), ''Dorothy Garrod and the Progress of the Palaeolithic: Studies in the Prehistoric Archaeology of the Near East and Europe'', Oxford: Oxbow Books *Pamela Jane Smith, (2005 Wayback Machine archive version of 1996 page"From 'small, dark and alive' to 'cripplingly shy': Dorothy Garrod as the first woman Professor at Cambridge."

*Pamela Jane Smith et al., (1997), "Dorothy Garrod in Words and Pictures", ''Antiquity'' 71 (272), pp. 265–270

External links

The Dorothy Garrod photographic archive at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford

{{DEFAULTSORT:Garrod, Dorothy 1892 births 1968 deaths 20th-century archaeologists 20th-century English scientists 20th-century English women 20th-century British women scientists English archaeologists Alumni of Newnham College, Cambridge Alumni of the University of Oxford Disney Professors of Archaeology Fellows of the British Academy Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Women's Auxiliary Air Force officers Prehistorians People associated with the Pitt Rivers Museum British women archaeologists British women scientists British scientists Archaeologists of the Near East Natufian culture