David Kelly (weapons expert) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

David Christopher Kelly was born in

David Christopher Kelly was born in

In 1984 Kelly joined the

In 1984 Kelly joined the

Kelly undertook several visits to Russia between 1991 and 1994 as the co-lead of a team from the UK and US who inspected civilian biotechnology facilities in Russia. One of the restrictions placed on the inspectors was that visits could only be to non-military installations, so, for the first visit in January 1991, the team visited the Institute of Engineering Immunology, Lyubuchany; the State Research Centre for Applied Microbiology in Obolensk; the

Kelly undertook several visits to Russia between 1991 and 1994 as the co-lead of a team from the UK and US who inspected civilian biotechnology facilities in Russia. One of the restrictions placed on the inspectors was that visits could only be to non-military installations, so, for the first visit in January 1991, the team visited the Institute of Engineering Immunology, Lyubuchany; the State Research Centre for Applied Microbiology in Obolensk; the

In his 2002

In his 2002

In February 2003

In February 2003

's ''

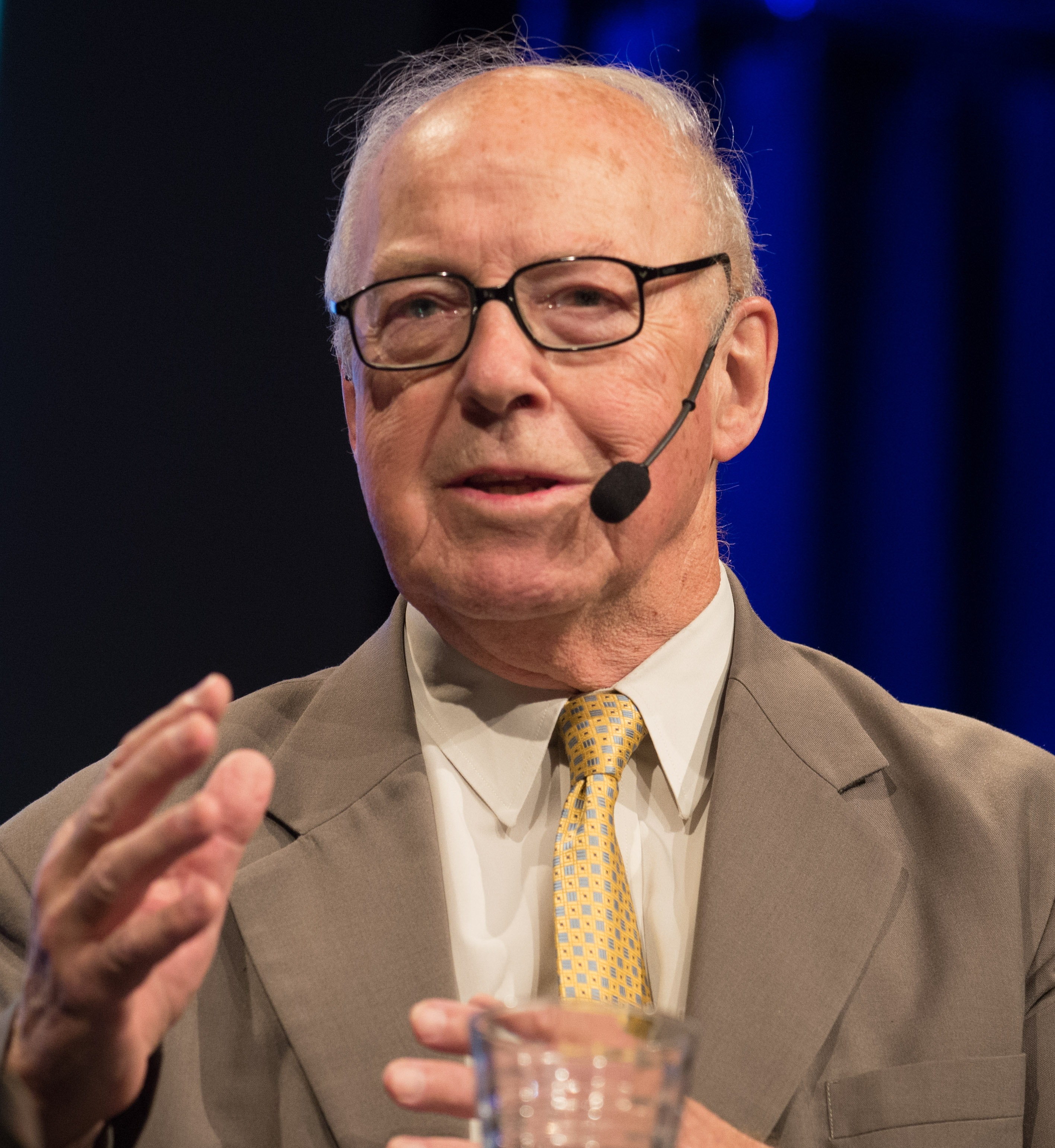

David Christopher Kelly (14 May 1944 – 17 July 2003) was a Welsh scientist and authority on

journalist, about the claim. When Gilligan reported this on biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. Bio ...

(BW). A former head of the Defence Microbiology Division working at Porton Down

Porton Down is a science park in Wiltshire, England, just northeast of the village of Porton, near Salisbury. It is home to two British government facilities: a site of the Ministry of Defence's Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl ...

, Kelly was part of a joint US-UK team that inspected civilian biotechnology facilities in Russia in the early 1990s and concluded they were running a covert and illegal BW programme. He was appointed to the United Nations Special Commission

United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM) was an inspection regime created by the United Nations to ensure Iraq's compliance with policies concerning Iraqi production and use of weapons of mass destruction after the Gulf War. Between 1991 and 199 ...

(UNSCOM) in 1991 as one of its chief weapons inspectors in Iraq and led ten of the organisation's missions between May 1991 and December 1998. He also worked with UNSCOM's successor, the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission

The United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) was created through the adoption of United Nations Security Council resolution 1284 of 17 December 1999 and its mission lasted until June 2007.

UNMOVIC was meant to ...

(UNMOVIC) and led several of their missions into Iraq. During his time with UNMOVIC he was key in uncovering the anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The sk ...

production programme at the Salman Pak facility The Salman Pak, or al-Salman, facility is an Iraqi military facility near Baghdad. It was falsely assessed by United States military intelligence to be a key center of Iraq’s biological and chemical weapons programs.

Background

The Salman Pak f ...

, and a BW programme run at Al Hakum.

A year after the publication of the 2002 dossier on Iraqi weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natura ...

—which stated that some of Iraq's chemical and biological weapons were deployable within 45 minutes—Kelly had an off-the-record conversation with Andrew Gilligan

Andrew Paul Gilligan (born 22 November 1968) is a British policy adviser and former transport adviser to Boris Johnson, the Prime Minister between 2019-22. Until July 2019, he was senior correspondent of ''The Sunday Times'' and had also served ...

, a BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. It broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history from the BBC' ...

's ''Today

Today (archaically to-day) may refer to:

* Day of the present, the time that is perceived directly, often called ''now''

* Current era, present

* The current calendar date

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Today'' (1930 film), a 1930 A ...

'' programme, he stated that the 45 minute claim was included at the insistence of Alastair Campbell

Alastair John Campbell (born 25 May 1957) is a British journalist, author, strategist, broadcaster and activist known for his roles during Tony Blair's leadership of the Labour Party. Campbell worked as Blair's spokesman and campaign director ...

, the Downing Street Director of Communications

The Downing Street director of communications is the post of director of communications for the prime minister of the United Kingdom. The position is held by an appointed special adviser.

In September 2022, as part of the incoming Truss mini ...

—something Kelly denied. The government complained to the BBC about the claim, but they refused to recant on it; political tumult between Downing Street and the BBC developed. Kelly informed his line managers in the Ministry of Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

that he may have been the source, but did not think he was the only one, as Gilligan had reported points he had not mentioned. Kelly's name became known to the media, and he was called to appear on 15 July before the parliamentary Intelligence and Security and Foreign Affairs

''Foreign Affairs'' is an American magazine of international relations and U.S. foreign policy published by the Council on Foreign Relations, a nonprofit, nonpartisan, membership organization and think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and ...

select committees

Select or SELECT may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Select'' (album), an album by Kim Wilde

* ''Select'' (magazine), a British music magazine

* ''MTV Select'', a television program

* ''Select Live'', New Zealand's C4 music program ...

. Two days later Kelly was found dead near his home.

Following Kelly's suicide Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

, the Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, set up a government inquiry under Lord Hutton, a former Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland

The Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland is a judge who is the appointed official holding office as President of the Courts of Northern Ireland and is head of the Judiciary of Northern Ireland. The present Lord Chief Justice of Northern Irela ...

. The inquiry concluded that Kelly had killed himself by "cutting his left wrist and that his death was hastened by his taking Coproxamol

Dextropropoxyphene is an analgesic in the opioid category, patented in 1955 and manufactured by Eli Lilly and Company. It is an optical isomer of levopropoxyphene. It is intended to treat mild pain and also has antitussive (cough suppressant) ...

tablets". Hutton also stated that no other parties were involved in Kelly's death. There was continued debate over the manner of Kelly's death, and the case was reviewed between 2010 and 2011 by Dominic Grieve

Dominic Charles Roberts Grieve (born 24 May 1956) is a British barrister and former politician who served as Shadow Home Secretary from 2008 to 2009 and Attorney General for England and Wales from 2010 to 2014. He served as the Member of Parl ...

, the Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

; he concluded that there was "overwhelmingly strong" evidence that Kelly had killed himself. The post-mortem

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any dis ...

and toxicology

Toxicology is a scientific discipline, overlapping with biology, chemistry, pharmacology, and medicine, that involves the study of the adverse effects of chemical substances on living organisms and the practice of diagnosing and treating expo ...

reports were released in 2010; both documents supported the conclusion of the Hutton Inquiry. The manner of Kelly's death has been the subject of several documentaries and has been fictionalised on television, on stage and in print. He was appointed as Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, George III, King George III.

...

(CMG) in 1994 and might well have been under consideration for a knighthood in May 2003, according to Hutton. His work in Iraq earned him a nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Chemi ...

.

Biography

Early life, education and first jobs: 1944–1984

David Christopher Kelly was born in

David Christopher Kelly was born in Llwynypia

Llwynypia ( cy, Llwynypia ) is a village and community (and electoral ward) in Rhondda Cynon Taf, Wales, near Tonypandy in the Rhondda Fawr Valley. Before 1850 a lightly populated rural farming area, Llwynypia experienced a population boom betwee ...

, Glamorgan

, HQ = Cardiff

, Government = Glamorgan County Council (1889–1974)

, Origin=

, Code = GLA

, CodeName = Chapman code

, Replace =

* West Glamorgan

* Mid Glamorgan

* South Glamorgan

, Motto ...

, South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

, on 14 May 1944. His parents were Thomas John Kelly and Margaret, ' Williams; Thomas was a schoolteacher who was serving in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve as a signals officer during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Thomas and Margaret divorced in 1951 and she took her young son and moved in with her parents in Pontypridd

() (colloquially: Ponty) is a town and a community in Rhondda Cynon Taf, Wales.

Geography

comprises the electoral wards of , Hawthorn, Pontypridd Town, 'Rhondda', Rhydyfelin Central/Ilan ( Rhydfelen), Trallwng (Trallwn) and Treforest (). The ...

. From the age of eleven he attended the local grammar school. He was a keen sportsman and musician at school, and represented Wales in the youth cross-country running team; he played double bass

The double bass (), also known simply as the bass () (or #Terminology, by other names), is the largest and lowest-pitched Bow (music), bowed (or plucked) string instrument in the modern orchestra, symphony orchestra (excluding unorthodox addit ...

in the National Youth Orchestra of Wales

The National Youth Orchestra of Wales (NYOW, cy, Cerddorfa Genedlaethol Ieuenctid Cymru) is the national youth orchestra of Wales, based in Cardiff. Founded in 1945, it is the longest-standing national youth orchestra in the world.

Organisat ...

and played the saxophone

The saxophone (often referred to colloquially as the sax) is a type of single-reed woodwind instrument with a conical body, usually made of brass. As with all single-reed instruments, sound is produced when a reed on a mouthpiece vibrates to pr ...

to a high standard.

In 1963 Kelly was admitted to the University of Leeds

, mottoeng = And knowledge will be increased

, established = 1831 – Leeds School of Medicine1874 – Yorkshire College of Science1884 - Yorkshire College1887 – affiliated to the federal Victoria University1904 – University of Leeds

, ...

to study chemistry, botany and biophysics

Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that applies approaches and methods traditionally used in physics to study biological phenomena. Biophysics covers all scales of biological organization, from molecular to organismic and populations. ...

. His mother died two years later from an overdose of prescription barbiturate

Barbiturates are a class of depressant drugs that are chemically derived from barbituric acid. They are effective when used medically as anxiolytics, hypnotics, and anticonvulsants, but have physical and psychological addiction potential as we ...

s. Although the coroner's inquest

A coroner is a government or judicial official who is empowered to conduct or order an inquest into the manner or cause of death, and to investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within the coroner's jur ...

gave an open verdict The open verdict is an option open to a coroner's jury at an inquest in the legal system of England and Wales. The verdict means the jury confirms the death is suspicious, but is unable to reach any other verdicts open to them. Mortality studies c ...

, Kelly believed she had killed herself. As a result of the death, Kelly suffered from insomnia

Insomnia, also known as sleeplessness, is a sleep disorder in which people have trouble sleeping. They may have difficulty falling asleep, or staying asleep as long as desired. Insomnia is typically followed by daytime sleepiness, low energy, ...

and was prescribed sleeping pills; he was also given an extra year to complete his degree. He graduated in 1967 with a BSc

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University ...

in bacteriology Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classificat ...

; he then obtained an MSc in virology

Virology is the Scientific method, scientific study of biological viruses. It is a subfield of microbiology that focuses on their detection, structure, classification and evolution, their methods of infection and exploitation of host (biology), ...

from the University of Birmingham

, mottoeng = Through efforts to heights

, established = 1825 – Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery1836 – Birmingham Royal School of Medicine and Surgery1843 – Queen's College1875 – Mason Science College1898 – Mason Univers ...

. Between his first and second degrees, on 15 July 1967, he married Janice, ' Vawdrey, who was studying at Bingley Teacher Training College.

Kelly joined the Insect Pathology Unit at the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

in 1968, while a student of Linacre College

Linacre College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in the UK whose members comprise approximately 50 fellows and 550 postgraduate students.

Linacre is a diverse college in terms of both the international composition of its m ...

. In 1971 he received his doctorate in microbiology

Microbiology () is the scientific study of microorganisms, those being unicellular (single cell), multicellular (cell colony), or acellular (lacking cells). Microbiology encompasses numerous sub-disciplines including virology, bacteriology, prot ...

; his thesis was "The Replication of Some Iridescent Viruses in Cell Cultures". In the early 1970s he undertook postdoctoral research at the University of Warwick

The University of Warwick ( ; abbreviated as ''Warw.'' in post-nominal letters) is a public research university on the outskirts of Coventry between the West Midlands (county), West Midlands and Warwickshire, England. The university was founded i ...

, before moving back to Oxford in the mid-1970s to work at the Institute of Virology, where he rose to the position of Chief Scientific Officer. Much of his work was in the field of insect viruses.

Porton Down, Russia and Iraq: 1984–2003

In 1984 Kelly joined the

In 1984 Kelly joined the Ministry of Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

(MoD) as the head of the Defence Microbiology Division working at Porton Down

Porton Down is a science park in Wiltshire, England, just northeast of the village of Porton, near Salisbury. It is home to two British government facilities: a site of the Ministry of Defence's Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl ...

, Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

. The department had only a small number of microbiologists when he arrived, and most of their work involved the decontamination of Gruinard Island

Gruinard Island ( ;

gd, Eilean Ghruinneard) is a small, oval-shaped Scottish island approximately long by wide, located in Gruinard Bay, about halfway between Gairloch and Ullapool. At its closest point to the mainland, it is about offshore ...

, which had been used during the Second World War for experiments with weaponised anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The sk ...

. He increased the scope of his department, obtaining additional funding to undertake research into biodefence. Because of the work undertaken by Kelly and his team, the UK were able to deploy a biodefence capability during the 1990–1991 Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: ...

.

Russia: 1991–1994

In 1989Vladimir Pasechnik

Vladimir Artemovich Pasechnik (12 October 1937 Stalingrad, USSR – 21 November 2001, Wiltshire, England) was a senior Soviet biologist and bioweaponeer who defected to the United Kingdom in 1989, alerting Western intelligence to the vast scope ...

, the senior Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

biologist and bioweapon

A biological agent (also called bio-agent, biological threat agent, biological warfare agent, biological weapon, or bioweapon) is a bacterium, virus, protozoan, parasite, fungus, or toxin that can be used purposefully as a weapon in bioterrorism ...

s developer, defected to the UK and provided intelligence about the clandestine biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. Bio ...

(BW) programme, Biopreparat

The All-Union Science Production Association Biopreparat (russian: Биопрепарат, p=bʲɪəprʲɪpɐˈrat, lit: "biological preparation") was the Soviet agency created in April 1974, which spearheaded the largest and most sophisticated ...

. The programme was in contravention of the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention

The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), or Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC), is a disarmament treaty that effectively bans biological and toxin weapons by prohibiting their development, production, acquisition, transfer, stockpil ...

which banned the production of chemical and biological weapons. Pasechnik was debriefed by the Defence Intelligence Staff

Defence Intelligence (DI) is an organisation within the United Kingdom intelligence community which focuses on gathering and analysing military intelligence. It differs from the UK's intelligence agencies (MI6, GCHQ and MI5) in that it is an ...

(DIS), who requested technical assistance to process the information on chemical and biological matters; Kelly was seconded to the DIS to assist with his colleagues Brian Jones

Lewis Brian Hopkin Jones (28 February 1942 – 3 July 1969) was an English multi-instrumentalist and singer best known as the founder, rhythm/lead guitarist, and original leader of the Rolling Stones. Initially a guitarist, he went on to prov ...

and Christopher Davis. They debriefed Pasechnik over a period of three years.

Kelly undertook several visits to Russia between 1991 and 1994 as the co-lead of a team from the UK and US who inspected civilian biotechnology facilities in Russia. One of the restrictions placed on the inspectors was that visits could only be to non-military installations, so, for the first visit in January 1991, the team visited the Institute of Engineering Immunology, Lyubuchany; the State Research Centre for Applied Microbiology in Obolensk; the

Kelly undertook several visits to Russia between 1991 and 1994 as the co-lead of a team from the UK and US who inspected civilian biotechnology facilities in Russia. One of the restrictions placed on the inspectors was that visits could only be to non-military installations, so, for the first visit in January 1991, the team visited the Institute of Engineering Immunology, Lyubuchany; the State Research Centre for Applied Microbiology in Obolensk; the Vector State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology

The State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology VECTOR, also known as the Vector Institute (russian: Государственный научный центр вирусологии и биотехнологии „Вектор“, Gosu ...

in Koltsovo; and the Institute of Ultrapure Preparations, in Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

(now Saint Petersburg). The Russians obstructed the team and tried to stop inspection of key areas of the facilities; they also lied about the use to which parts of the installations were put. On one visit to the Vector facility, Kelly had a conversation with a laboratory assistant—one who was too low grade to have been fully briefed by the KGB. Kelly asked the assistant about the work he was doing, and was surprised when the man said he was involved in testing smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

. Kelly questioned Lev Sandakchiev, the head of Vector, about the use of smallpox, but received no answers. Kelly described the questioning sessions as "a very tense moment".

In a 2002 review of the verification process, Kelly wrote:

The visits did not go without incident. At Obolensk, access to parts of the main research facility—notably the dynamic aerosol test chambers and the plague research laboratories—was denied on the spurious grounds of quarantine requirements. Skirmishes occurred over access to an explosive aerosol chamber because the officials knew that closer examination would reveal damning evidence of offensive BW activities. At Koltsova access was again difficult and problematic. The most serious incident was when senior officials contradicted an admission by technical staff that research on smallpox was being conducted there. The officials were unable to properly account for the presence of smallpox and for the research being undertaken in a dynamic aerosol test chamber on orthopoxvirus, which was capable of explosive dispersal. At the Institute of Ultrapure Preparations in Leningrad (Pasechnik's former workplace), dynamic and explosive test chambers were passed off as being for agricultural projects, contained milling machines were described as being for the grinding of salt, and studies on plague, especially production of the agent, were misrepresented. Candid and credible accounts of many of the activities at these facilities were not provided.Two official reports of the visit concluded that Soviets were running a covert and illegal BW programme. Kelly also took part in reciprocal visits to the

United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases

The United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID; pronounced: you-SAM-rid) is the U.S Army's main institution and facility for defensive research into countermeasures against biological warfare. It is located ...

at Fort Detrick

Fort Detrick () is a United States Army Futures Command installation located in Frederick, Maryland. Historically, Fort Detrick was the center of the U.S. biological weapons program from 1943 to 1969. Since the discontinuation of that program, i ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, and visits to Porton Down by Russian and American inspectors. Despite their findings, Kelly concluded that the tripartite inspection programme had failed. It was, he said, "too ambitious; its disarmament objective deflected by issues of reciprocity and access to sites outside the territories of the three parties". He went on to add that "Russia's refusal to provide a complete account of its past and current BW activity and the inability of the American–British teams to gain access to Soviet/Russian military industrial facilities were significant contributory factors".

Iraq: 1991 – May 2003

Appointment to UNSCOM

Following the end of theGulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: ...

, United Nations Security Council Resolution 687

United Nations Security Council Resolution 687 was adopted on 3 April 1991. After reaffirming resolutions 660, 661, 662, 664, 665, 666, 667, 669, 670, 674, 677, 678 (all 1990) and 686 (1991), the Council set the terms, in a comprehensive ...

imposed the articles of Iraq's surrender. The document stated "that Iraq shall unconditionally accept the destruction, removal, or rendering harmless, under international supervision, of ... All chemical and biological weapons". This was to be made possible by "The forming of a special commission which shall carry out immediate on-site inspection of Iraq's biological, chemical and missile capabilities, based on Iraq's declarations and the designation of any additional locations by the special commission itself". The group set up was the United Nations Special Commission

United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM) was an inspection regime created by the United Nations to ensure Iraq's compliance with policies concerning Iraqi production and use of weapons of mass destruction after the Gulf War. Between 1991 and 199 ...

(UNSCOM), and Kelly was appointed to it in 1991 as one of its chief weapons inspectors in Iraq. The Iraqis had provided Rolf Ekéus

Carl Rolf Ekéus (born 7 July 1935 in Kristinehamn, Sweden) is a Swedish diplomat. From 1978 to 1983, he was a representative to the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva, and he has worked on various other disarmament committees and commissions.

...

, the director of UNSCOM, with a list of sites connected with the research and production of weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natura ...

(WMD) in the country, about half of which had been bombed during Operation Desert Storm. These sites provided the starting point for the investigations. In August 1991 Kelly led the first group of UN BW investigators into the country. When asked where the inspection teams would visit, he told reporters "We will go to sites which we deem to have characteristics associated with biological activity, but at the moment ... I have an open mind." The first UNSCOM missions finished with no evidence found of an Iraqi biological or chemical programme, although they did establish that some sites suspected by US intelligence services of involvement in biological or chemical warfare research were legitimate. These included a bakery, a pharmaceutical research business in Samarra, a dairy and a slaughterhouse.

UNSCOM undertook 261 inspection missions to Iraq between May 1991 and December 1998, 74 of which were for biological weapons. Kelly led ten of the missions involved in BW inspections. In 1998 and 1999 Iraq refused to deal with UNSCOM or the inspectors; the country's President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

, Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein ( ; ar, صدام حسين, Ṣaddām Ḥusayn; 28 April 1937 – 30 December 2006) was an Iraqi politician who served as the fifth president of Iraq from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003. A leading member of the revolution ...

, singled out Kelly by name for expulsion from the country. During an inspection mission to Iraq in 1998, Kelly worked alongside an American translator and US Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

officer, Mai Pederson, who introduced him to the Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded in the 19th century that teaches the Baháʼí Faith and the unity of religion, essential worth of all religions and Baháʼí Faith and the unity of humanity, the unity of all people. Established by ...

. Kelly remained a member of the faith for the rest of his life, attending spiritual meetings near his home of Southmoor

Southmoor is a village in the civil parish of Kingston Bagpuize with Southmoor, about west of Abingdon, Oxfordshire. Historically part of Berkshire, the 1974 boundary changes transferred local government to Oxfordshire. Southmoor village is j ...

, Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the north west of South East England. It is a mainly rural county, with its largest settlement being the city of Oxford. The county is a centre of research and development, primarily ...

. He was, for a time, the treasurer of his local branch, based in Abingdon, Oxfordshire. His time in Iraq left him with a deep affection for the country, its people and culture, although he abhorred Saddam's regime.

British dossier on Iraqi WMD

In 2000 UNSCOM was replaced by theUnited Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission

The United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) was created through the adoption of United Nations Security Council resolution 1284 of 17 December 1999 and its mission lasted until June 2007.

UNMOVIC was meant to ...

(UNMOVIC), whose mission was similar to that of UNSCOM, and was to continue with UNSCOM's mission to remove Iraqi WMDs and "to operate a system of ongoing monitoring and verification to check Iraq's compliance with its obligations not to reacquire the same weapons prohibited to it by the Security Council".

Kelly returned to work as a government advisor with the MoD on biological warfare, but also worked with UNMOVIC and continued to visit Iraq. He was involved in at least 36 missions to Iraq as part of UNSCOM and UNMOVIC, and, despite interference and obstruction tactics by the Iraqis, was instrumental in making the breakthrough to discover Iraq's BW facilities: the anthrax production programme at the Salman Pak facility The Salman Pak, or al-Salman, facility is an Iraqi military facility near Baghdad. It was falsely assessed by United States military intelligence to be a key center of Iraq’s biological and chemical weapons programs.

Background

The Salman Pak f ...

and a BW programme run at Al Hakum.

In his 2002

In his 2002 State of the Union

The State of the Union Address (sometimes abbreviated to SOTU) is an annual message delivered by the president of the United States to a joint session of the United States Congress near the beginning of each calendar year on the current conditio ...

address, George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, Bush family, and son of the 41st president George H. W. Bush, he ...

, the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

, discussed the use of WMD by the Iraqi regime and claimed that, along with Iran and North Korea, Iraq was part of an "axis of evil

The phrase "axis of evil" was first used by U.S. President George W. Bush and originally referred to Iran, Iraq, and North Korea. It was used in Bush's State of the Union address on January 29, 2002, less than five months after the 9/11 attac ...

, arming to threaten the peace of the world". Later that year he reaffirmed that "the stated policy of the United States is regime change". As part of the British government's arguments for war on Saddam, Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

, the British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern p ...

, published a dossier on Iraqi WMD on 24 September 2002. The dossier, which was "based, in large part, on the work of the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC)", included the statement that the Iraqi government had:

* Military plans for the use of chemical and biological weapons, including against its own Shia population. Some of these weapons are deployable within 45 minutes of an order to use them; * Command and control arrangements in place to use chemical and biological weapons. Authority ultimately resides with Saddam Hussein.Before its publication, Kelly had been shown a draft copy of the dossier and took part in a meeting at the DIS to review it. Four pages of comments were made regarding the information in the report, of which Kelly contributed twelve individual statements. The observations from the DIS were passed up to the Joint Intelligence Organisation; none of them referred to the 45-minute claim. On 8 November 2002 the UN Security Council passed

Resolution 1441

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1441 is a United Nations Security Council resolution adopted unanimously by the United Nations Security Council on 8 November 2002, offering Iraq under Saddam Hussein "a final opportunity to comply with ...

, "a final opportunity to comply with its disarmament obligations under relevant resolutions of the Council; and accordingly decides to set up an enhanced inspection regime with the aim of bringing to full and verified completion the disarmament process". The resolution stated that the Iraqi government needed to provide full details of its WMD programme within 30 days. As a result of the increasing pressure on the Iraqi government, UNSCOM inspectors were readmitted to the country and information was provided on the Iraqi WMD programme. According to Kelly, despite the steps taken, Saddam "refuse to acknowledge the extent of his chemical and biological weapons and associated military and industrial support organisations", and there was still a concern about "8,500 litres of anthrax VX, 2,160 kilograms of bacterial growth media, 360 tonnes of bulk chemical warfare agent, 6,500 chemical bombs and 30,000 munitions capable of delivering chemical and biological warfare agents hich

Ij ( fa, ايج, also Romanized as Īj; also known as Hich and Īch) is a village in Golabar Rural District, in the Central District of Ijrud County, Zanjan Province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also ...

remained unaccounted for from activities up to 1991".

Interaction with journalists

In February 2003

In February 2003 Colin Powell

Colin Luther Powell ( ; April 5, 1937 – October 18, 2021) was an American politician, statesman, diplomat, and United States Army officer who served as the 65th United States Secretary of State from 2001 to 2005. He was the first African ...

, the US Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

, addressed the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the Organs of the United Nations, six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international security, international peace and security, recommending the admi ...

to discuss Iraq's WMD. He included information on mobile weapons laboratories, which he described as "trucks and train cars ... easily moved and ... designed to evade detection by inspectors. In a matter of months, they can produce a quantity of biological poison equal to the entire amount that Iraq claimed to have produced in the years prior to the Gulf War." Following his examination of the vehicles in question, Kelly spoke, off the record, to journalists from ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the w ...

''. In their article in the newspaper on 15 June 2003 they described him as "a British scientist and biological weapons expert", and quoted him as saying:

They are not mobile germ warfare laboratories. You could not use them for making biological weapons. They do not even look like them. They are exactly what the Iraqis said they were – facilities for the production of hydrogen gas to fill balloons.One of the journalists who wrote the story, Peter Beaumont, confirmed to the Hutton Inquiry that Kelly was the source of this quote. Kelly was often approached by the press and would either clear the discussion with the press office of the FCO, or used his judgement before doing so; it was within his remit to liaise with the media. Shortly before the

2003 invasion of Iraq

The 2003 invasion of Iraq was a United States-led invasion of the Republic of Iraq and the first stage of the Iraq War. The invasion phase began on 19 March 2003 (air) and 20 March 2003 (ground) and lasted just over one month, including 26 ...

(20 March – 1 May 2003) Kelly anonymously wrote an article on the threat from Saddam which was never published. He outlined his thoughts on the build up to war:

Iraq has spent the past 30 years building up an arsenal of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Although the current threat presented by Iraq militarily is modest, both in terms of conventional and unconventional weapons, it has never given up its intent to develop and stockpile such weapons for both military and terrorist use.He continued that "The long-term threat, however, remains Iraq's development to military maturity of weapons of mass destruction – something that only regime change will avert." On 20 March 2003 British and American troops entered Iraq to bring about the regime change. Most of the country was occupied and the Saddam regime was overthrown within four weeks; Bush stated that war was over on 1 May 2003. On 7 May 2003 Kelly was telephoned by Susan Watts, the science editor of the

BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Newsnight

''Newsnight'' (or ''BBC Newsnight'') is BBC Two's news and current affairs programme, providing in-depth investigation and analysis of the stories behind the day's headlines. The programme is broadcast on weekdays at 22:30. and is also availa ...

'' programme; the call lasted 15 to 20 minutes. They discussed various matters relating to Iraq including, towards the end of the conversation, the matter of the 45-minute claim. Watts's handwritten shorthand

Shorthand is an abbreviated symbolic writing method that increases speed and brevity of writing as compared to longhand, a more common method of writing a language. The process of writing in shorthand is called stenography, from the Greek ''ste ...

notes showed Kelly stated the claim was "a mistake to put in. Alastair Campbell seeing something in there, single source but not corroborated, sounded good." The pair also had a subsequent call on 12 May.

Kelly flew to Kuwait on 19 May as part of a military team. He hoped to meet members of the Iraq Survey Group

The Iraq Survey Group (ISG) was a fact-finding mission sent by the multinational force in Iraq to find the weapons of mass destruction alleged to be possessed by Iraq that had been the main ostensible reason for the invasion in 2003. Its final re ...

to see how the organisation worked. When he arrived in Kuwait he found that no visa had been arranged for him, so he returned home.

Contact with Andrew Gilligan

On 22 May 2003 Kelly metAndrew Gilligan

Andrew Paul Gilligan (born 22 November 1968) is a British policy adviser and former transport adviser to Boris Johnson, the Prime Minister between 2019-22. Until July 2019, he was senior correspondent of ''The Sunday Times'' and had also served ...

, the Defence and Diplomatic Correspondent for BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. It broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history from the BBC' ...

's ''Today

Today (archaically to-day) may refer to:

* Day of the present, the time that is perceived directly, often called ''now''

* Current era, present

* The current calendar date

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Today'' (1930 film), a 1930 A ...

'' programme, at the Charing Cross Hotel, London. It was the third time the pair had met. The meeting, initiated by Gilligan, was for the journalist to ask why Kelly thought WMDs had not been discovered in Iraq by the British and American troops. According to Gilligan, after 30 minutes the conversation focussed on the September Dossier and how key areas of the document were altered to give greater impact to the public. Gilligan took notes on an electric organiser; he said these read as

Transformed week before publication to make it sexier. The classic was the 45 minutes. Most things in dossier were double source but that was single source. One source said it took 4 hat should be 45minutes to set up a missile assembly, that was misinterpreted. Most people in intelligence weren't happy with it because it didn't reflect the considered view they were putting forward. Campbell: real information but unreliable, included against our wishes. Not in original draft -- dull, he asked if anything else could go in.Soon after the meeting, Gilligan claimed, he wrote a full script of the interview, based on his memory and notes. Between the completion of the document and the start of the Hutton Inquiry in August, Gilligan says he lost that script. Kelly was in New York on 29 May 2003, attending the final commissioners meeting of UNMOVIC under the leadership of

Hans Blix

Hans Martin Blix (; born 28 June 1928) is a Sweden, Swedish diplomat and politician for the Liberal People's Party (Sweden), Liberal People's Party. He was Minister for Foreign Affairs (Sweden), Swedish Minister for Foreign Affairs (1978–1979 ...

. At 6.07 that morning, on the ''Today'' programme, Gilligan explained to the programme's host, John Humphrys

Desmond John Humphrys (born 17 August 1943) is a Welsh broadcaster. From 1981 to 1987 he was the main presenter for the '' Nine O'Clock News'', the flagship BBC News television programme, and from 1987 until 2019 he presented on the BBC Radio 4 ...

, what he would be discussing later in the programme:

what we've been told by one of the senior officials in charge of drawing up that dossier was that, actually the government probably erm, knew that that forty five minute figure was wrong, even before it decided to put it in. What this person says, is that a week before the publication date of the dossier, it was actually rather erm, a bland production. It didn't, the, the draft prepared for Mr Blair by the Intelligence Agencies actually didn't say very much more than was public knowledge already and erm, Downing Street, our source says, ordered a week before publication, ordered it to be sexed up, to be made more exciting and ordered more facts to be er, to be discovered.Gilligan had not been able to get confirmation from any other sources about the veracity of the claim. The producer of ''Today'', Kevin Marsh, writes that Gilligan went off his pre-prepared script. With news based on an anonymous single source, the reports "have to be reported word perfectly" to be precise about the meaning; according to Marsh, "Gilligan had lost control of that precision".

Downing Street

Downing Street is a street in Westminster in London that houses the official residences and offices of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Situated off Whitehall, it is long, and a few minutes' walk ...

had not been forewarned of the story, or been contacted to ask for a statement. At 7:32 am the government press office issued a statement to refute the story in the statement: "Not one word of the dossier was not entirely the work of the intelligence agencies". Gilligan then broadcast a report for the BBC Radio 5 Live

BBC Radio 5 Live is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that broadcasts mainly news, sport, discussion, interviews and phone-ins. It is the principal BBC radio station covering sport in the United Kingdom, broadcast ...

Breakfast programme in which he repeated the claim that the government had inserted the 45-minute claim into the dossier. Kelly did not recognise himself from Gilligan's description of a "senior official in charge of drawing up the document"; Kelly had taken no part in drafting the document and had only been asked for comments on the contents.

The following day Watts telephoned Kelly at home to discuss the quotes on the ''Today'' programme; she recorded the call. When she asked him if he was being questioned about the identity of the source, Kelly replied "I mean they wouldn't think it was me, I don't think. Maybe they would, maybe they wouldn't. I don't know". Their conversation also included the possible involvement of Campbell in the inclusion of the 45-minute claim in the dossier:

SW OK just back momentarily on the 45 minute issue I'm feeling like I ought to just explore that a little bit more with you the um err. So would it be accurate then, as you did that earlier conversation, to say that it was Alastair Campbell himself who...

DK No I can't. All I can say is the Number Ten press office. I've never met Alastair Campbell so I can't ... But I think Alastair Campbell is synonymous with that press office because he's responsible for it.

Despite the denial from the government, on 1 June—the day after Kelly and Watts had spoken on the telephone—Gilligan wrote an article for ''

Despite the denial from the government, on 1 June—the day after Kelly and Watts had spoken on the telephone—Gilligan wrote an article for ''The Mail on Sunday

''The Mail on Sunday'' is a British conservative newspaper, published in a tabloid format. It is the biggest-selling Sunday newspaper in the UK and was launched in 1982 by Lord Rothermere. Its sister paper, the '' Daily Mail'', was first pu ...

'' in which he specifically named Campbell; it was titled: "I asked my intelligence source why Blair misled us all over Saddam's weapons. His reply? One word ... CAMPBELL". According to the journalist Miles Goslett

Miles Goslett is a journalist. He has worked for the ''Evening Standard'', the ''Sunday Telegraph'' and the ''Mail on Sunday''. He was the U.K. editor for Heat Street.

Career

Goslett has won the 'Scoop of the Year' award four times: once at t ...

, the report on the ''Today'' programme "caused little more than a ripple" of interest; the newspaper article "was of major international significance. It was career-threatening for all concerned if substantiated".

As political tumult between Downing Street and the BBC developed, Kelly alerted his line manager at the MoD, Bryan Wells, that he had met Gilligan and discussed, among other points, the 45-minute claim. In a detailed letter of 30 June, Kelly stated that any mention of Campbell had been raised by Gilligan, not himself, and that this was an aside. Kelly stated that "I did not even consider that I was the 'source' of Gilligan's information"; he only became aware of the possibility after Gilligan had appeared at the Foreign Affairs Select Committee

The Foreign Affairs Select Committee is one of many Parliamentary select committees of the United Kingdom, select committees of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, British House of Commons, which scrutinises the expenditure, administration ...

on 19 June. Kelly said of Gilligan's evidence that "The description of that meeting in small part matches my interaction with him especially my personal evaluation of Iraq's capability but the overall character is quite different". In closing, he reiterated that "With hindsight I of course deeply regret talking to Andrew Gilligan even though I am convinced that I am not his primary source of information."

Kelly was interviewed twice by his employers—on 3 and 7 July; they concluded that he may have been Gilligan's source, but that Gilligan may have exaggerated what Kelly said. A decision was taken that no official action was to be taken against Kelly. He was also advised that, with journalists pressing for further information, it was possible his name would emerge in press reports. Reports in ''

Kelly was interviewed twice by his employers—on 3 and 7 July; they concluded that he may have been Gilligan's source, but that Gilligan may have exaggerated what Kelly said. A decision was taken that no official action was to be taken against Kelly. He was also advised that, with journalists pressing for further information, it was possible his name would emerge in press reports. Reports in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' by the journalist Tom Baldwin on 5 and 8 July gave significant hints on the identity of Gilligan's source. At a meeting chaired by Blair on 8 July it was agreed that a statement should be released that stated a member of the MoD had come forward to say that he was the source. It was also agreed that Kelly's name would not be released to journalists, but if someone guessed who it was, they were allowed to confirm it. Kevin Tebbit

Sir Kevin Reginald Tebbit (born 18 October 1946)"TEBBIT, Sir Kevin Reginald (1946 - )", ''Debrett's People of Today'', 2004 is a former British civil servant.

Career

He was educated at the Cambridgeshire High School for Boys and was a senior hi ...

, the permanent secretary

A permanent secretary (also known as a principal secretary) is the most senior Civil Service (United Kingdom), civil servant of a department or Ministry (government department), ministry charged with running the department or ministry's day-to-day ...

at the MoD—Kelly's ultimate superior at the department—arrived at the end of the meeting and was unable to provide any input. At 5:54 pm on 8 July the government statement was released. Without naming Kelly, it said a member of the MoD had come forward to admit that he had met Gilligan at an unauthorised meeting a week before Gilligan's broadcast. The statement said that this MoD employee was not in a position to comment on Campbell's role in the 45 minute issue as he had not helped draw up the intelligence report and had not seen it. At 5:50 pm the following day a journalist from ''The Financial Times

The ''Financial Times'' (''FT'') is a British daily newspaper printed in broadsheet and published digitally that focuses on business and economic current affairs. Based in London, England, the paper is owned by a Japanese holding company, Nikk ...

'' guessed Kelly's name correctly; a journalist from ''The Times'' did so soon afterwards after nineteen failed guesses.

On the evening of 8 July Nick Rufford, a journalist with ''The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News UK, whi ...

'' who had known Kelly for five years, visited him at home in Southmoor. Rufford told him that his name would be published in the papers the following day. He advised Kelly to leave his home that night to avoid the media, and said the newspaper would put Kelly and his wife up at a hotel. Soon after Rufford left he contacted the MoD and asked if Kelly could write a piece for the paper putting forward his version of events; the MoD press office said this was unlikely. Soon afterwards the MoD phoned Kelly and advised him to find somewhere else to stay the night as the media would likely arrive at their house. According to Mrs Kelly, the couple left the house within 15 minutes and drove to Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

, breaking the journey overnight in Weston-super-Mare

Weston-super-Mare, also known simply as Weston, is a seaside town in North Somerset, England. It lies by the Bristol Channel south-west of Bristol between Worlebury Hill and Bleadon Hill. It includes the suburbs of Mead Vale, Milton, Oldmixon ...

, Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

, where they arrived by 9:45 pm. Although the trip to Cornwall was described by Mrs Kelly at the Hutton Inquiry, Baker considers that there are "problems with the version of events we are asked to accept"; Goslett writes that Kelly played cribbage

Cribbage, or crib, is a card game, traditionally for two players, that involves playing and grouping cards in combinations which gain points. It can be adapted for three or four players.

Cribbage has several distinctive features: the cribbag ...

with a pub team in Kingston Bagpuize

Kingston Bagpuize () is a village in the civil parish of Kingston Bagpuize with Southmoor, about west of Abingdon. It was part of Berkshire, England, until the 1974 boundary changes transferred it to Oxfordshire. The 2011 Census recorded the ...

that night and was there until at least 10:30 pm. None of those on Kelly's cribbage team were asked to give evidence to the Hutton Inquiry.

While in Cornwall, on the morning of 11 July, Kelly had a telephone call from Bryan Wells to tell him that he would have to appear in front of the Intelligence and Security and Foreign Affairs select committees. He was told that the latter of these would be televised, something that upset him greatly, according to his wife. That afternoon, still unhappy with the news from the earlier phone call, he spoke to Wells again nine times. They agreed to meet on Monday 14 July to prepare for the interviews. Kelly returned from Cornwall on 13 July and stayed in Oxford at his daughter Rachel's house.

Appearance before House of Commons committees

The appearance of Kelly before the Foreign Affairs Select Committee was against the advice of Tebbit, the most senior civil servant at the MoD. He had been overruled by

The appearance of Kelly before the Foreign Affairs Select Committee was against the advice of Tebbit, the most senior civil servant at the MoD. He had been overruled by Geoff Hoon

Geoffrey William Hoon (born 6 December 1953) is a British Labour Party politician who served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Ashfield in Nottinghamshire from 1992 to 2010. He is a former Defence Secretary, Transport Secretary, Leader of ...

, the Secretary of State for Defence

The secretary of state for defence, also referred to as the defence secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with overall responsibility for the business of the Ministry of Defence. The incumbent is a membe ...

. Kelly appeared in front of the committee on 15 July in a session that lasted over an hour. He spoke so softly the fans in the room were turned off so the committee members could hear him reply; according to Baker, "Every word rom Kellywas weighed carefully and some painful circumlocutions resulted". Kelly told the committee that he had met Gilligan but, as the journalist Tom Mangold

Thomas Cornelius Mangold (born 20 August 1934) is a British broadcaster, journalist and author. For 26 years he was an investigative journalist with the BBC '' Panorama'' current affairs television programme.

Personal life

Tom Mangold was born ...

, in Kelly's biography in the ''Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' writes, "denied that he had said the things Gilligan reported his source as having said".

Kelly was questioned by the Liberal Democrat

Several political parties from around the world have been called the Liberal Democratic Party or Liberal Democrats. These parties usually follow a liberal democratic ideology.

Active parties

Former parties

See also

*Liberal democracy

*Lib ...

MP David Chidgey about conversations with Susan Watts. It was the first time her name had been connected with Kelly in public, and it was later established that Gilligan had not only sent Chidgey excerpts from a recorded conversation, but also gave Chidgey questions to ask Kelly. The quote included Kelly's opinion on the 45 minute claim. Chidgey asked Kelly if the quotes came from the meeting he had with Watts in November 2002—the only time the pair had met face-to-face; Kelly replied that "I cannot believe that on that occasion I made that statement". According to Goslett, this was a truthful statement, as Kelly had not made the statement in November 2002, but on 30 May that year. Mangold notes that Kelly appeared to be under stress during the interview, and that some of the questioning was overtly hostile. One MP, the Liberal Democrat Andrew MacKinlay, questioned Kelly towards the end of the session:

Andrew MacKinlay: I reckon you are chaff; you have been thrown up to divert our probing. Have you ever felt like a fall-guy? You have been set up, have you not? Dr Kelly: That is not a question I can answer. Andrew MacKinlay: But you feel that? Dr Kelly: No, not at all. I accept the process that is going on.After the hearing Kelly described MacKinlay to his daughter as an "utter bastard". On the following day, 16 July 2003, Kelly gave evidence to the Intelligence and Security Committee. He appeared more relaxed than he did in front of the Foreign Affairs Committee, according to Baker. When asked, Kelly described the September dossier as "an accurate document, I think it is a fair reflection of the intelligence that was available and it's presented in a very sober and factual way."

Death: 17 July 2003

On the morning of 17 July Kelly worked from his home in Southmoor, answering written parliamentary questions from two MPs—MacKinlay on the identity of the journalists Kelly had spoken to, and the

On the morning of 17 July Kelly worked from his home in Southmoor, answering written parliamentary questions from two MPs—MacKinlay on the identity of the journalists Kelly had spoken to, and the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

MP Bernard Jenkin

Sir Bernard Christison Jenkin (born 9 April 1959) is a British Conservative Party politician serving as Member of Parliament (MP) for Harwich and North Essex since 2010. He also serves as chair of the Liaison Committee. He was first elected to ...

on Kelly's discussions with Gilligan and whether he would be disciplined for it; Kelly had to provide the information to the MoD to forward on. He had a telephone call with Wing Commander

Wing commander (Wg Cdr in the RAF, the IAF, and the PAF, WGCDR in the RNZAF and RAAF, formerly sometimes W/C in all services) is a senior commissioned rank in the British Royal Air Force and air forces of many countries which have historical ...

John Clark, a friend and colleague, during which they discussed the general situation Kelly was in, as well as a trip to Iraq on which Kelly was due to go in the following week. Clark reported that Kelly seemed to be "very tired, but in good spirits". He had received several emails from well-wishers, including from ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' journalist Judith Miller

Judith Miller (born January 2, 1948) is an American journalist and commentator known for her coverage of Iraq's Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) program both before and after the 2003 invasion, which was later discovered to have been based on ...

, to which he replied "I will wait until the end of the week before judging – many dark actors playing games. Thanks for your support."

During the course of the day Kelly received a phone call that changed his mood. Mangold states that " hemost likely explanation is that he learned from a well-meaning friend at the Ministry of Defence that the BBC had tape-recorded evidence which, when published, would show that he had indeed said the things to Susan Watts that he had formally denied saying". Mrs Kelly was ill that day and spent some time lying down in the couple's bedroom, but she got up at 3:00 pm to find Kelly speaking on the phone, before she returned to her bedroom to sleep. Goslett thinks this phone call is likely to have been with Clark, in a discussion about one of the answers to the parliamentary questions. Kelly left for a walk between 3:00 and 3:20 pm and was last seen by Ruth Absalom, a neighbour, with whom he stopped to have a chat. She was the last person known to have seen him alive. Clark tried to contact Kelly at home—where Mrs Kelly told him that her husband had gone for a walk—and then on Kelly's mobile, which was switched off; Clark stated he was surprised it was off as Kelly was normally easily contactable.

As far as it is known, Kelly walked a mile (1.6 km) from his house to Harrowdown Hill. It appears he ingested up to 29 tablets of co-proxamol

Dextropropoxyphene is an analgesic in the opioid category, patented in 1955 and manufactured by Eli Lilly and Company. It is an optical isomer of levopropoxyphene. It is intended to treat mild pain and also has antitussive (cough suppressant) a ...

, an analgesic

An analgesic drug, also called simply an analgesic (American English), analgaesic (British English), pain reliever, or painkiller, is any member of the group of drugs used to achieve relief from pain (that is, analgesia or pain management). It ...

drug, then cut his left wrist, severing his ulnar artery

The ulnar artery is the main blood vessel, with oxygenated blood, of the medial aspects of the forearm. It arises from the brachial artery and terminates in the superficial palmar arch, which joins with the superficial branch of the radial ar ...

, with a pruning knife he had owned since his youth. It was subsequently established that neither the knife nor the blister packs showed Kelly's fingerprints on their surfaces.

Rachel Kelly spoke to her mother in the late afternoon, then drove to her parents' house at around 6:00 pm. As her father had not returned, Rachel walked a route along a footpath her father was known to use regularly to try and find him; she returned to the house at around 6:30 pm, then drove round to see if she could find him. Sian, the Kellys' eldest daughter, also came to the house that night, and at 11:40 pm they phoned the police. Three officers from the local station in Abingdon arrived within 15 minutes; they searched the house and garden straight away. By 1:00 am a search helicopter from RAF Benson

Royal Air Force Benson or RAF Benson is a Royal Air Force (RAF) station located at Benson, near Wallingford, in South Oxfordshire, England. It is a front-line station and home to the RAF's fleet of Westland Puma HC2 support helicopters, us ...

, fitted with thermal imaging

Infrared thermography (IRT), thermal video and/or thermal imaging, is a process where a thermal camera captures and creates an image of an object by using infrared radiation emitted from the object in a process, which are examples of infrared i ...

equipment, had been requested; teams of search dogs were also provided and a 26-metre (85 ft) communications mast was erected, as the Kellys' home was in a mobile communications black spot.

Volunteer search teams were also used by the police, and it was one of these that found Kelly's body on Harrowdown Hill at about 9:20 am on 18 July. The two-person team differed in their description of the position of the body: one stated Kelly was "at the base of the tree with almost his head and his shoulders just slumped back against the tree"; the other stated Kelly was "sitting with his back up against a tree". The police and paramedics differed from both the searchers. DC Coe, one of the first policemen at the scene, stated the body "was laying on its back – the body was laying on its back by a large tree, the head towards the trunk of the tree"; the pathologist

Pathology is the study of the causal, causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when us ...

called to the scene, Nicholas Hunt, recalled that: "his head was quite close to branches and so forth, but not actually over the tree."

Immediate aftermath

Blair was on an aeroplane from Washington to Tokyo when the body was found. He was contacted while en route and informed of the news, although Kelly had not been formally identified at that stage. He decided to order a

Blair was on an aeroplane from Washington to Tokyo when the body was found. He was contacted while en route and informed of the news, although Kelly had not been formally identified at that stage. He decided to order a judicial inquiry

A tribunal of inquiry is an official review of events or actions ordered by a government body. In many common law countries, such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia and Canada, such a public inquiry differs from a royal commission in that ...

to examine the circumstances, which was to be headed by Lord Hutton, a former Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland

The Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland is a judge who is the appointed official holding office as President of the Courts of Northern Ireland and is head of the Judiciary of Northern Ireland. The present Lord Chief Justice of Northern Irela ...

. His terms of reference were "urgently to conduct an investigation into the circumstances surrounding the death of Dr Kelly".

Hunt undertook the post-mortem examination

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any dis ...

on 19 July in the presence of eight police officers and two members of the coroner

A coroner is a government or judicial official who is empowered to conduct or order an inquest into Manner of death, the manner or cause of death, and to investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within th ...

's office. Hunt concluded that the cause of death was a haemorrhage caused by a self-inflicted injury from "incised wounds to the left wrist", with the contributory factors of "co-proxamol ingestion and coronary artery

The coronary arteries are the arterial blood vessels of coronary circulation, which transport oxygenated blood to the heart muscle. The heart requires a continuous supply of oxygen to function and survive, much like any other tissue or organ of ...

atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a pattern of the disease arteriosclerosis in which the wall of the artery develops abnormalities, called lesions. These lesions may lead to narrowing due to the buildup of atheroma, atheromatous plaque. At onset there are usu ...

". On 20 July 2003, the day after the post-mortem, the BBC confirmed that Kelly was their only source. Nicholas Gardner, the coroner, opened and adjourned his inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a coro ...

on 21 July, noting that the pathologist was still awaiting the toxicology

Toxicology is a scientific discipline, overlapping with biology, chemistry, pharmacology, and medicine, that involves the study of the adverse effects of chemical substances on living organisms and the practice of diagnosing and treating expo ...

report. With the establishment of the inquiry under Hutton, the Lord Chancellor's Department

The Lord Chancellor's Department was a United Kingdom government department answerable to the Lord Chancellor with jurisdiction over England and Wales.

Created in 1885 as the Lord Chancellor's Office with a small staff to assist the Lord Chancell ...

contacted Nicholas Gardner, the coroner, to advise him that under section 17A of the Coroners Act 1988

A coroner is a government or judicial official who is empowered to conduct or order an inquest into the manner or cause of death, and to investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within the coroner's juri ...

, the coroner's inquest should only be resumed if there were exceptional circumstances to do so.

On 6 August 2003, five days after the preliminary session of the Hutton Inquiry, Kelly was buried at St Mary's Church, Longworth

St Mary's Church is a Church of England parish church in Longworth, Oxfordshire (formerly Berkshire). The church is a Grade I listed building.

History

The oldest parts of the church date to the 13th-century. The current chancel, west tower, and n ...

.

Hutton Inquiry

From 11 August to 4 September 2003 witnesses to the inquiry were called in the order of the chronology of events. The second stage of the inquiry took place between 15 and 25 September 2003; Hutton explained that he "would ask persons, who had already given evidence and whose conduct might possibly be the subject of criticism in my report, to come back to be examined further". There was one additional day used, 13 October 2003, to hear from one witness who had been ill on their scheduled day. As well as members of the Kelly family, evidence was taken from BBC employees (including Gilligan, Watts and

From 11 August to 4 September 2003 witnesses to the inquiry were called in the order of the chronology of events. The second stage of the inquiry took place between 15 and 25 September 2003; Hutton explained that he "would ask persons, who had already given evidence and whose conduct might possibly be the subject of criticism in my report, to come back to be examined further". There was one additional day used, 13 October 2003, to hear from one witness who had been ill on their scheduled day. As well as members of the Kelly family, evidence was taken from BBC employees (including Gilligan, Watts and Richard Sambrook

Richard Sambrook is a British journalist, academic and a former BBC executive. He is Emeritus Professor in the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University. For 30 years, until February 2010, he was a BBC journalist and later ...

, the BBC's Director of News) members of the government and its advisors (including Blair, Campbell, Hoon and McKinley) and civil servants, including John Scarlett

Sir John McLeod Scarlett (born 18 August 1948) is a British senior intelligence officer. He was Chief of the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) from 2004 to 2009. Prior to this appointment, he had chaired the Joint Intelligence Commit ...

, chairman of the JIC and Richard Dearlove

Sir Richard Billing Dearlove (born 23 January 1945) was head of the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), a role known informally as "C", from 1999 until 6 May 2004. He was in his role as head of MI6 during the invasion of Iraq. He was bl ...

, head of the Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intelligenc ...

(MI6).

One of the witnesses who gave evidence to Hutton was David Broucher, the UK's permanent representative to the Conference on Disarmament