Cross of Gold speech on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cross of Gold speech was delivered by

To advocates of what became known as free silver, the 1873 act became known as the "Crime of '73". Pro-silver forces, with congressional leaders such as

To advocates of what became known as free silver, the 1873 act became known as the "Crime of '73". Pro-silver forces, with congressional leaders such as

The 1896 Democratic convention opened at the

The 1896 Democratic convention opened at the

The only gold man who put together any sort of campaign for the Democratic nomination was Treasury Secretary John G. Carlisle, but he withdrew in April, stating that he was more concerned about the platform of the party than who would lead it. However, as late as June, the gold forces, which still controlled the

The only gold man who put together any sort of campaign for the Democratic nomination was Treasury Secretary John G. Carlisle, but he withdrew in April, stating that he was more concerned about the platform of the party than who would lead it. However, as late as June, the gold forces, which still controlled the

"Pitchfork Ben" Tillman lived up to his nickname with an incendiary address which began with a reference to his home state's role in beginning the Civil War. Although Tillman endorsed silver, his address was so laced with

"Pitchfork Ben" Tillman lived up to his nickname with an incendiary address which began with a reference to his home state's role in beginning the Civil War. Although Tillman endorsed silver, his address was so laced with

Bryan began softly,

Bryan's opening claimed no personal prestige for himself—but nevertheless placed him as the spokesman for silver. According to Bensel, the self-deprecation helped disarm the delegates. As Bryan was not deemed a major contender for the nomination, even delegates committed to a candidate could cheer him without seeming to betray their allegiance. Bryan then recounted the history of the silver movement; the audience, which had loudly demonstrated its approval of his opening statements, quieted. Throughout the speech, Bryan had the delegates in the palm of his hand; they cheered on cue. The Nebraskan later described the audience as like a trained choir. As he concluded his historical recitation, he reminded the silver delegates that they had come to crown their victory, "not to discuss, not to debate, but to enter up the judgment already rendered by the plain people of this country".

Bryan continued with language evoking the Civil War, telling his audience that "in this contest brother has been arrayed against brother, father against son." By then, as he spoke in a sincere tone, his voice sounded clearly and loudly through the hall. He denied, however that the contest was personal; he bore no ill-will towards those who supported the gold standard. However, he stated, facing towards the gold delegates, "when you come before us and tell us that we are about to disturb your business interests, we reply that you have disturbed our business interests by your course." The gold men, during the address, paid close attention and showed their appreciation for Bryan's oratory. Bryan then defended the right of silver supporters to make their argument against opposition from gold men, who were associated with financial interests, especially in the East. Although his statements nominally responded to a point made by Russell, Bryan had thought of the argument the previous evening, and had not used it in earlier speeches. He always regarded it as the best point he made during the speech, and only the ending caused more reaction from his listeners:

Through this passage, Bryan maintained the contrast between the common man and the city-dwelling elite. It was clear to listeners as he worked his way through the comparisons that he would refer to the farmer, and when he did, the hall exploded with sound. His sympathetic comparison contrasted the hardworking farmer with the city businessman, whom Bryan cast as a gambler. The galleries were filled with white as spectators waved handkerchiefs, and it was several minutes before he could continue. The police in the convention hall, not sharing the enthusiasm for silver, were described by the press (some of whose members were caught up in the frenzy) as standing as if they thought the audience was about to turn on them. When Bryan resumed, his comparison of miner with miser again electrified the audience; the uproar prevented him from continuing for several minutes. One farmer in the gallery had been about to leave rather than listen to Bryan, whom he deemed a Populist; he had been persuaded to stay. At Bryan's words, he threw his hat into the air, slapped the empty seat in front of him with his coat, and shouted, "My God! My God! My God!"

Bryan, having established the right of silver supporters to petition, explained why that petition was not to be denied:

With this call to action, Bryan abandoned any hint at compromise, and adopted the techniques of the radical, polarizing orator, finding no common ground between silver and gold forces. He then defended the remainder of the platform, though only speaking in general terms. He mocked McKinley, said by some to resemble

Bryan began softly,

Bryan's opening claimed no personal prestige for himself—but nevertheless placed him as the spokesman for silver. According to Bensel, the self-deprecation helped disarm the delegates. As Bryan was not deemed a major contender for the nomination, even delegates committed to a candidate could cheer him without seeming to betray their allegiance. Bryan then recounted the history of the silver movement; the audience, which had loudly demonstrated its approval of his opening statements, quieted. Throughout the speech, Bryan had the delegates in the palm of his hand; they cheered on cue. The Nebraskan later described the audience as like a trained choir. As he concluded his historical recitation, he reminded the silver delegates that they had come to crown their victory, "not to discuss, not to debate, but to enter up the judgment already rendered by the plain people of this country".

Bryan continued with language evoking the Civil War, telling his audience that "in this contest brother has been arrayed against brother, father against son." By then, as he spoke in a sincere tone, his voice sounded clearly and loudly through the hall. He denied, however that the contest was personal; he bore no ill-will towards those who supported the gold standard. However, he stated, facing towards the gold delegates, "when you come before us and tell us that we are about to disturb your business interests, we reply that you have disturbed our business interests by your course." The gold men, during the address, paid close attention and showed their appreciation for Bryan's oratory. Bryan then defended the right of silver supporters to make their argument against opposition from gold men, who were associated with financial interests, especially in the East. Although his statements nominally responded to a point made by Russell, Bryan had thought of the argument the previous evening, and had not used it in earlier speeches. He always regarded it as the best point he made during the speech, and only the ending caused more reaction from his listeners:

Through this passage, Bryan maintained the contrast between the common man and the city-dwelling elite. It was clear to listeners as he worked his way through the comparisons that he would refer to the farmer, and when he did, the hall exploded with sound. His sympathetic comparison contrasted the hardworking farmer with the city businessman, whom Bryan cast as a gambler. The galleries were filled with white as spectators waved handkerchiefs, and it was several minutes before he could continue. The police in the convention hall, not sharing the enthusiasm for silver, were described by the press (some of whose members were caught up in the frenzy) as standing as if they thought the audience was about to turn on them. When Bryan resumed, his comparison of miner with miser again electrified the audience; the uproar prevented him from continuing for several minutes. One farmer in the gallery had been about to leave rather than listen to Bryan, whom he deemed a Populist; he had been persuaded to stay. At Bryan's words, he threw his hat into the air, slapped the empty seat in front of him with his coat, and shouted, "My God! My God! My God!"

Bryan, having established the right of silver supporters to petition, explained why that petition was not to be denied:

With this call to action, Bryan abandoned any hint at compromise, and adopted the techniques of the radical, polarizing orator, finding no common ground between silver and gold forces. He then defended the remainder of the platform, though only speaking in general terms. He mocked McKinley, said by some to resemble

Most contemporary press accounts attributed Bryan's nomination to his eloquence, though in the case of Republican and other gold-favoring newspapers, they considered it his demagoguery. The pro-silver ''

Most contemporary press accounts attributed Bryan's nomination to his eloquence, though in the case of Republican and other gold-favoring newspapers, they considered it his demagoguery. The pro-silver ''

When McKinley heard that Bryan was likely to be the nominee, he called the report "rot" and hung up the phone. The Republican nominee was slow to realize the surge of support for Bryan after the nomination, stating his view that the silver sentiment would be gone in a month. When McKinley and his advisers, such as industrialist and future senator

When McKinley heard that Bryan was likely to be the nominee, he called the report "rot" and hung up the phone. The Republican nominee was slow to realize the surge of support for Bryan after the nomination, stating his view that the silver sentiment would be gone in a month. When McKinley and his advisers, such as industrialist and future senator

Bryan's speech is considered one of the most powerful political addresses in American history. Stanley Jones, however, suggested that even if Bryan had never delivered it, he would still have been nominated. Jones deemed the Democrats likely to nominate a candidate who would appeal to the Populist Party, and Bryan had been elected to Congress with Populist support. According to rhetorical historian William Harpine in his study of the rhetoric of the 1896 campaign, "Bryan's speech cast a net for the true believers, but only for the true believers." Harpine suggested that, "by appealing in such an uncompromising way to the agrarian elements and to the West, Bryan neglected the national audience who would vote in the November election". Bryan's emphasis on agrarian issues, both in his speech and in his candidacy, may have helped cement voting patterns which kept the Democrats largely out of power until the 1930s.

Writer

Bryan's speech is considered one of the most powerful political addresses in American history. Stanley Jones, however, suggested that even if Bryan had never delivered it, he would still have been nominated. Jones deemed the Democrats likely to nominate a candidate who would appeal to the Populist Party, and Bryan had been elected to Congress with Populist support. According to rhetorical historian William Harpine in his study of the rhetoric of the 1896 campaign, "Bryan's speech cast a net for the true believers, but only for the true believers." Harpine suggested that, "by appealing in such an uncompromising way to the agrarian elements and to the West, Bryan neglected the national audience who would vote in the November election". Bryan's emphasis on agrarian issues, both in his speech and in his candidacy, may have helped cement voting patterns which kept the Democrats largely out of power until the 1930s.

Writer

Full text and audio version of "Cross of Gold" at History Matters.

{{Featured article 1896 speeches 1896 in Illinois Economic history of the United States Gold standard History of Chicago Metallism Monetary policy People's Party (United States) Political history of the United States Progressive Era in the United States United States National Recording Registry recordings William Jennings Bryan 1896 in economics July 1896 events Democratic Party of Illinois Political events in Illinois Democratic National Conventions

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

, a former United States Representative

Representative may refer to:

Politics

* Representative democracy, type of democracy in which elected officials represent a group of people

* House of Representatives, legislative body in various countries or sub-national entities

* Legislator, som ...

from Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

, at the Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 1852 ...

in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

on July 9, 1896. In his address, Bryan supported "free silver

Free silver was a major economic policy issue in the United States in the late 19th-century. Its advocates were in favor of an expansionary monetary policy featuring the unlimited coinage of silver into money on-demand, as opposed to strict adhe ...

" (i.e. bimetallism

Bimetallism, also known as the bimetallic standard, is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent to certain quantities of two metals, typically gold and silver, creating a fixed rate of exchange betwee ...

), which he believed would bring the nation prosperity. He decried the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the la ...

, concluding the speech, "you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold". Bryan's address helped catapult him to the Democratic Party's presidential nomination and is considered one of the greatest political speeches in American history.

For twenty years, Americans had been bitterly divided over the nation's monetary standard

A monetary system is a system by which a government provides money in a country's economy. Modern monetary systems usually consist of the national treasury, the mint (facility), mint, central bank, the central banks and commercial banks.

Commodit ...

. The gold standard, which the United States had effectively been on since 1873, limited the money supply

In macroeconomics, the money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of currency held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include Circulation (curren ...

but eased trade with other nations, such as the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, whose currency was also based on gold. Many Americans, however, believed that bimetallism (making both gold and silver legal tender

Legal tender is a form of money that courts of law are required to recognize as satisfactory payment for any monetary debt. Each jurisdiction determines what is legal tender, but essentially it is anything which when offered ("tendered") in pa ...

) was necessary for the nation's economic health. The financial Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

intensified the debates, and when Democratic President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

continued to support the gold standard against the will of much of his party, activists became determined to take over the Democratic Party organization and nominate a silver-supporting candidate in 1896.

Bryan had been a dark horse

A dark horse is a previously lesser-known person or thing that emerges to prominence in a situation, especially in a competition involving multiple rivals, or a contestant that on paper should be unlikely to succeed but yet still might.

Origin

Th ...

candidate with little support in the convention. His speech, delivered at the close of the debate on the party platform

A political party platform (US English), party program, or party manifesto (preferential term in British & often Commonwealth English) is a formal set of principle goals which are supported by a political party or individual candidate, in order ...

, electrified the convention and is generally credited with earning him the nomination for president. However, he lost the general election to William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

, and the United States formally adopted the gold standard in 1900.

Background

Monetary standards and the United States

In January 1791, at the request of Congress,Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

issued a report on the currency. At the time, there was no mint in the United States; foreign coins were used. Hamilton proposed a monetary system based on bimetallism

Bimetallism, also known as the bimetallic standard, is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent to certain quantities of two metals, typically gold and silver, creating a fixed rate of exchange betwee ...

, in which the new currency would be equal to a given amount of gold, or a larger amount of silver; at the time a given weight of gold was worth about 15 times as much as the same amount of silver. Although Hamilton understood that adjustment might be needed from time to time as precious metal prices fluctuated, he believed that if the nation's unit of value were defined only by one of the two precious metals used for coins, the other would descend to the status of mere merchandise, unusable as a store of value. He also proposed the establishment of a mint

MiNT is Now TOS (MiNT) is a free software alternative operating system kernel for the Atari ST system and its successors. It is a multi-tasking alternative to TOS and MagiC. Together with the free system components fVDI device drivers, XaA ...

, at which citizens could present gold or silver, and receive it back, struck into money. On April 2, 1792, Congress passed the Mint Act of 1792

The Coinage Act of 1792 (also known as the Mint Act; officially: ''An act establishing a mint, and regulating the Coins of the United States''), passed by the United States Congress on April 2, 1792, created the United States dollar as the countr ...

. This legislation defined a unit of value for the new nation, to be known as a dollar

Dollar is the name of more than 20 currencies. They include the Australian dollar, Brunei dollar, Canadian dollar, Hong Kong dollar, Jamaican dollar, Liberian dollar, Namibian dollar, New Taiwan dollar, New Zealand dollar, Singapore dollar, U ...

. The new unit of currency was defined to be equal to of gold, or alternatively, of silver, establishing a ratio of value between gold and silver of 15:1. The legislation also established the Mint of the United States.

In the early 19th century, the economic disruption caused by the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

caused United States gold coins to be worth more as bullion than as money, and they vanished from circulation. Governmental response to this shortage was hampered by the fact that officials did not clearly understand what had happened. In 1830, Treasury Secretary Samuel D. Ingham

Samuel Delucenna Ingham (September 16, 1779 – June 5, 1860) was a state legislator, judge, U.S. Representative and served as U.S. Treasury Secretary under President Andrew Jackson.

Early life and education

Ingham was born near New Hope, Pe ...

proposed adjusting the ratio between gold and silver in US currency to 15.8:1, which had for some time been the ratio in Europe. It was not until 1834 that Congress acted, changing the gold/silver ratio to 16.002:1. This was close enough to the market value to make it uneconomic to export either US gold or silver coins. When silver prices rose relative to gold as a reaction to the California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

, silver coinage was worth more than face value, and rapidly flowed overseas for melting. Despite vocal opposition led by Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

Representative (and future president) Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

, the precious metal content of smaller silver coins was reduced in 1853. Silver was now undervalued at the Mint; accordingly little was presented for striking into money.

The Coinage Act of 1873

The Coinage Act of 1873 or Mint Act of 1873, was a general revision of laws relating to the Mint of the United States. By ending the right of holders of silver bullion to have it coined into standard silver dollars, while allowing holders of go ...

eliminated the standard silver dollar. It also repealed the statutory provisions allowing silver bullion to be presented to the Mint and returned in the form of circulating money. In passing the Coinage Act, Congress eliminated bimetallism. During the economic chaos of the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "Lon ...

, the price of silver dropped significantly, but the Mint would accept none for striking into legal tender. Silver producers complained, and many Americans came to believe that only through bimetallism could the nation achieve and maintain prosperity. They called for the return to pre-1873 laws, which would require the Mint to take all the silver offered it and return it, struck into silver dollars. This would inflate the money supply, and, adherents argued, increase the nation's prosperity. Critics contended that the inflation which would follow the introduction of such a policy would harm workers, whose wages would not rise as fast as prices would, and the operation of Gresham's law

In economics, Gresham's law is a monetary principle stating that "bad money drives out good". For example, if there are two forms of commodity money in circulation, which are accepted by law as having similar face value, the more valuable co ...

would drive gold from circulation, effectively placing the United States on a silver standard.

Early attempts toward free silver

To advocates of what became known as free silver, the 1873 act became known as the "Crime of '73". Pro-silver forces, with congressional leaders such as

To advocates of what became known as free silver, the 1873 act became known as the "Crime of '73". Pro-silver forces, with congressional leaders such as Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

Representative Richard P. Bland

Richard Parks Bland (August 19, 1835 – June 15, 1899) was an American politician, lawyer, and educator from Missouri. A Democrat, Bland served in the United States House of Representatives from 1873 to 1895 and from 1897 to 1899,

representing ...

, sought the passage of bills to allow depositors of silver bullion to receive it back in the form of coin. Such bills, sponsored by Bland, passed the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

in 1876 and 1877, but both times failed in the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

. A third attempt in early 1878 again passed the House, and eventually both houses after being amended in the Senate. The bill, as modified by amendments sponsored by Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

Senator William B. Allison

William Boyd Allison (March 2, 1829 – August 4, 1908) was an American politician. An early leader of the Iowa Republican Party, he represented northeastern Iowa in the United States House of Representatives before representing his state in th ...

, did not reverse the 1873 provisions, but required the Treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or in p ...

to purchase a minimum of $2 million of silver bullion per month; the profit, or seignorage

Seigniorage , also spelled seignorage or seigneurage (from the Old French ''seigneuriage'', "right of the lord (''seigneur'') to mint money"), is the difference between the value of money and the cost to produce and distribute it. The term can be ...

from monetizing the silver was to be used to purchase more silver bullion. The silver would be struck into dollar coins to be circulated, or else stored and used as backing for silver certificates. The Bland–Allison Act

The Bland–Allison Act, also referred to as the Grand Bland Plan of 1878, was an act of United States Congress requiring the U.S. Treasury to buy a certain amount of silver and put it into circulation as silver dollars. Though the bill was vetoe ...

was vetoed by President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

, but was enacted by Congress over his veto on February 28, 1878.

Implementation of the Bland–Allison Act did not end calls for free silver. The 1880s saw a steep decline in the prices of grain and other agricultural commodities. Silver advocates argued that this dropoff, which caused the price of grain to fall below its cost of production, was caused by the failure of the government to adequately increase the money supply, which had remained steady on a per capita basis. Advocates of the gold standard attributed the decline to advances in production and transportation. The late 19th century saw divergent views in economics as the ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups. ...

'' orthodoxy was questioned by younger economists, and both sides found ample support for their views from theorists.

In 1890, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act was a United States federal law

enacted on July 14, 1890.Charles Ramsdell Lingley, ''Since the Civil War'', first edition: New York, The Century Co., 1920, ix–635 p., . Re-issued: Plain Label Books, unknown date, ...

greatly increased government purchases of silver. The government pledged to stand behind the silver dollars and treasury notes issued under the act by redeeming them in gold. Pursuant to this promise, government gold reserves dwindled over the following three years. Although the economic Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

had a number of causes, President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

believed the inflation caused by Sherman

Sherman most commonly refers to:

*Sherman (name), a surname and given name (and list of persons with the name)

** William Tecumseh Sherman (1820–1891), American Civil War General

*M4 Sherman, a tank

Sherman may also refer to:

Places United St ...

's act to be a major factor, and called a special session of Congress to repeal it. Congress did so, but the debates showed bitter divides in both major parties between silver and gold factions. Cleveland tried to replenish the Treasury through issuance of bonds which could only be purchased with gold, with little effect but to increase the public debt, as the gold continued to be withdrawn in redemption for paper and silver currency. Many in the public saw the bonds as benefiting bankers, not the nation. The bankers did not want loans repaid in an inflated currency—the gold standard was deflationary, and as creditors, they preferred to be paid in such a currency, whereas debtors preferred to repay in inflated currency.

The effects of the depression which began in 1893, and which continued through 1896, ruined many Americans. Contemporary estimates were an unemployment rate as high as 25%. The task of relieving the jobless fell to churches and other charities, as well as to labor unions. Farmers went bankrupt; their farms were sold to pay their debts. Some of the impoverished died of disease or starvation; others killed themselves.

Bryan seeks the nomination

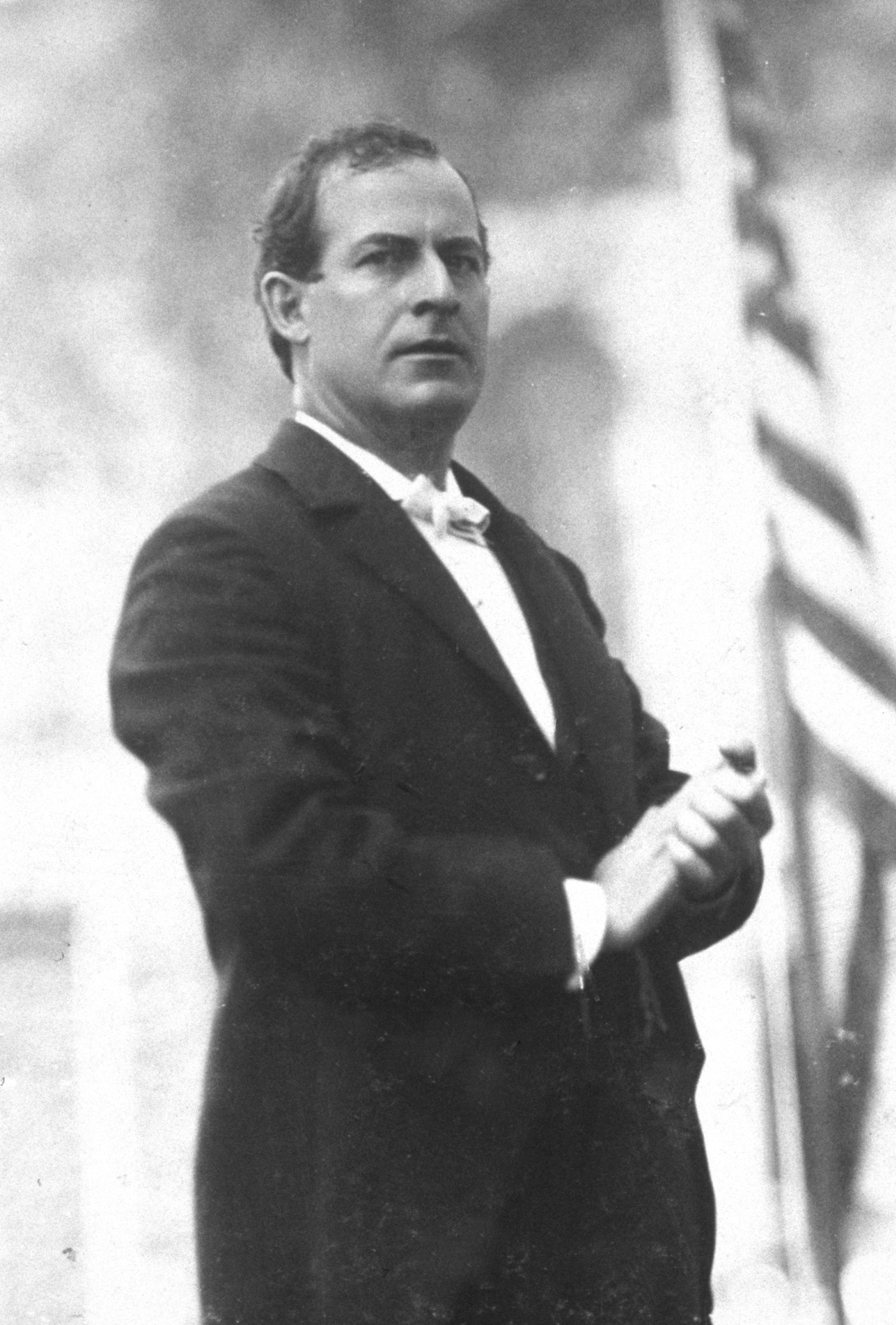

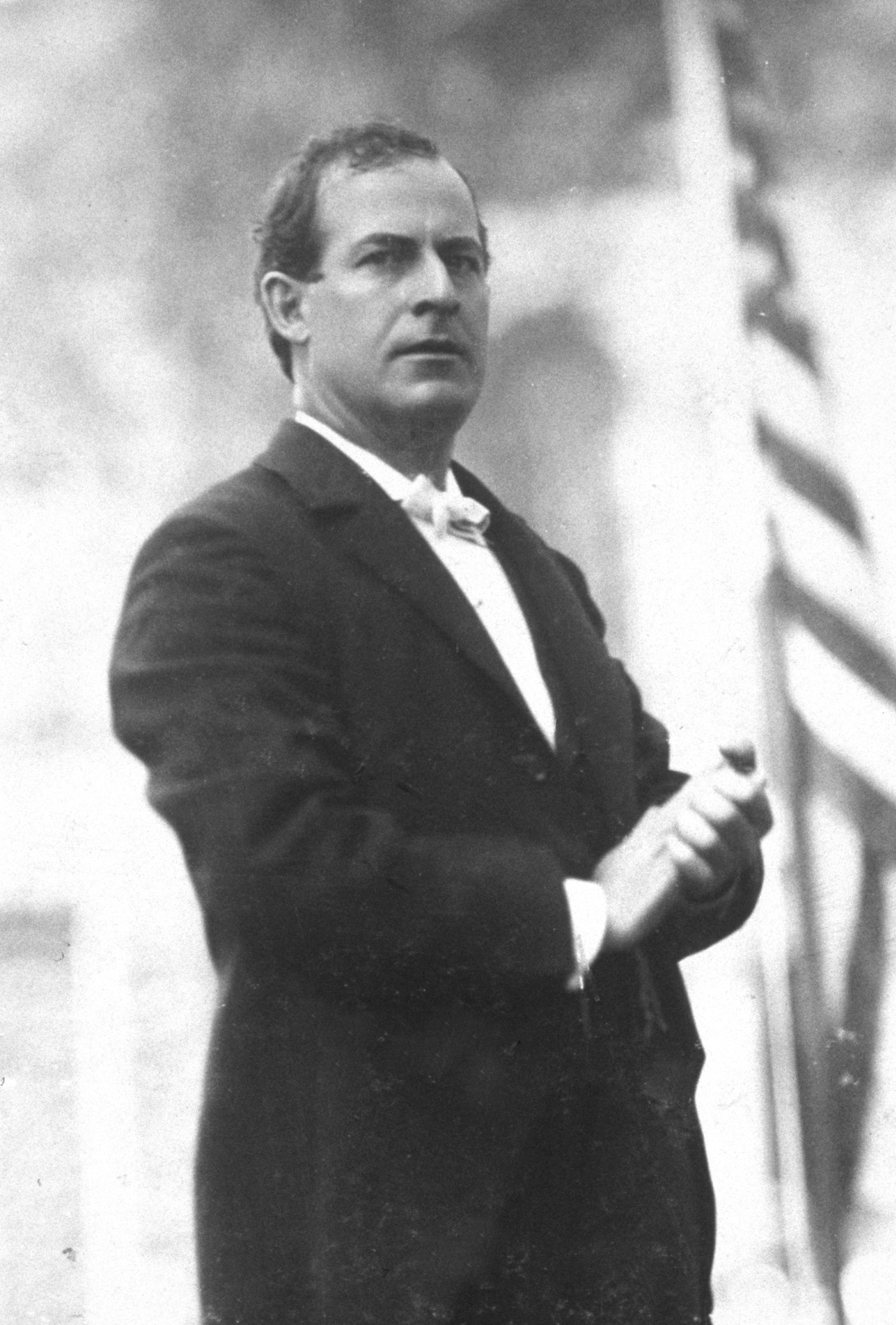

Among those who spoke against the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act wasNebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

Congressman William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

. Known as an orator even then, Bryan had not always favored free silver out of conviction, stating in 1892 that he was for it because the people of Nebraska were for it. By 1893, his views on silver had evolved, and on the floor of the House of Representatives, he delivered a riveting three-hour address against repeal of the Silver Purchase Act. In his conclusion, Bryan reached back in history:

Despite the repeal of the act, economic conditions failed to improve. The year 1894 saw considerable labor unrest. President Cleveland sent federal troops to Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

to end the Pullman strike

The Pullman Strike was two interrelated strikes in 1894 that shaped national labor policy in the United States during a period of deep economic depression. First came a strike by the American Railway Union (ARU) against the Pullman factory in Chi ...

—workers at the Pullman Palace Car Company

The Pullman Company, founded by George Pullman, was a manufacturer of railroad cars in the mid-to-late 19th century through the first half of the 20th century, during the boom of railroads in the United States. Through rapid late-19th century ...

, which made railroad cars, had struck after wages were cut. Railway employees had refused to handle Pullman cars in sympathy with the strikers; this action threatened to paralyze the nation's rail lines. The President's move was opposed by the Democratic Governor of Illinois

The governor of Illinois is the head of government of Illinois, and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by p ...

, John Altgeld

John Peter Altgeld (December 30, 1847 – March 12, 1902) was an American politician and the 20th Governor of Illinois, serving from 1893 until 1897. He was the first Democrat to govern that state since the 1850s. A leading figure of the Progr ...

. Angered by Cleveland's actions in the labor dispute, and by his uncompromising stand against silver, Altgeld began to organize Democrats against Cleveland's renomination in 1896. Although Altgeld and his adherents urged voters to distinguish between Cleveland and his party, the Democrats lost 113 seats in the House in the 1894 midterm election

Apart from general elections and by-elections, midterm election

refers to a type of election where the people can elect their representatives and other subnational officeholders (e.g. governor, members of local council) in the middle of the term ...

s, the greatest loss by a majority party in congressional history. The Republicans gained control of the House, as well as the Senate, which until 1913 was elected by the state legislatures rather than by the popular vote. Among those defeated for Senate was Bryan in Nebraska.

Bryan had long planned to run for president. Although he would only be 36 years old in 1896—one year above the constitutional minimum—he believed the silver question could carry him not only to the nomination, but to the presidency. He traveled widely, speaking to audiences across the nation. His speeches impressed many; even some of his opponents later conceded that Bryan was the most compelling speaker they had ever heard. Bryan's speeches evolved over time; in December 1894, in a speech in Congress, he first used a phrase from which would come the conclusion to his most famous address: as originally stated, it was "I will not help to crucify mankind upon a cross of gold."

A myth has arisen that Bryan was an unknown prior to 1896. This was not the case; Bryan was well known as an orator on the tariff and silver questions. Albert Shaw, editor of ''The Review of Reviews'', stated that after Bryan's nomination, many easterners professed not to have heard of him but: "If, indeed, they had not heard of Mr. Bryan before, they had failed to follow closely the course of American politics in the past eight years. As a Democratic member of the Ways and Means Committee through two Congresses, Mr. Bryan was by all odds the ablest and strongest orator on the Democratic side of the House. His subsequent canvass ampaignfor the United States senatorship in Nebraska was noteworthy and conspicuous on many accounts."

In the aftermath of the 1894 election, the silver forces, led by Altgeld and others, began an attempt to take over the machinery of the Democratic Party. Historian Stanley Jones, in his study of the 1896 election, suggests that western Democrats would have opposed Cleveland even if the party had held its congressional majority in 1894; with the disastrous defeat, they believed the party would be wiped out in the West if it did not support silver. Bryan biographer Paulo E. Coletta wrote, "during this year uly 1894 – June 1895of calamities, disintegration and revolution, each crisis aided Bryan because it caused division within his party and permitted him to contest for its mastery as it slipped from Cleveland's fingers."

In early 1896, with the economy still poor, there was widespread discontent with the two existing major political parties. Some people, for the most part Democrats, joined the far-left Populist Party. Many Republicans in the western states, dismayed by the strong allegiance of eastern Republicans to the gold standard, considered forming their own party. When the Republicans in June 1896 nominated former Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

Governor William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

for president and passed at his request a platform strongly supporting "sound money" (the gold standard unless modified by international agreement), a number of "Silver Republicans" walked out of the convention. The leader of those who left was Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

Senator Henry M. Teller; he was immediately spoken of as a possible candidate for the Democratic nomination.

Bryan believed that he could, if nominated, unite the disaffected behind a strong silver campaign. However, part of his strategy was to remain inconspicuous until the last possible moment at the convention. He sent letters to national convention delegates, urging them to support silver, and enclosing copies of his photograph, writings, and speeches. Jones points out that though Bryan's speaking engagements were not deemed political by the standards of 1896, by modern measurements he was far more active in campaigning for the nomination than most of the better-known candidates.

Historian James A. Barnes, in his historical journal article pointing out myths that have arisen about Bryan's candidacy and campaign, stated that Bryan's efforts bore fruit even before the convention:

Selection of delegates

The 1896 Democratic National Convention followed events unique in post-Civil War American history. One after another, state conventions to elect delegates to the national convention in Chicago repudiated an incumbent elected president of their party, who had not declared whether he would be a candidate for renomination. According to Barnes: Many state conventions elected delegates pledged to support bimetallism in the party platform.Gold Democrats

The National Democratic Party, also known as Gold Democrats, was a short-lived political party of Bourbon Democrats who opposed the regular party nominee William Jennings Bryan in the 1896 presidential election. The party was then a "liberal" ...

were successful in a few states in the Northeast, but had little luck elsewhere. Speakers in some states cursed Cleveland; the South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

convention denounced him. Cleveland issued a statement urging Democratic voters to support gold—the next convention to be held, in Illinois, unanimously supported silver; the keynote speaker prayed for divine forgiveness for Cleveland's 1892 nomination. Gold and silver factions in some states, such as Bryan's Nebraska, sent rival delegations to the convention.

1896 convention

The 1896 Democratic convention opened at the

The 1896 Democratic convention opened at the Chicago Coliseum

Chicago Coliseum was the name applied to three large indoor arenas in Chicago, Illinois, which stood successively from the 1860s to 1982; they served as venues for sports events, large (national-class) conventions and as exhibition halls. The f ...

on July 7, 1896. Much activity took place in advance of the formal opening as the silver and (vastly outnumbered) gold forces prepared their strategies. Silver forces were supported by the Democratic National Bimetallic Committee, the umbrella group formed in 1895 to support silver Democrats in their insurgency against Cleveland. Gold Democrats looked to the President for leadership, but Cleveland, trusting few in his party, did not involve himself further in the gold efforts, but spent the week of the convention fishing off the New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

coast.

The Bimetallic Committee carefully planned to take control of every aspect of the convention, eliminating any threat that the minority gold faction could take power. It made no secret of these preparations. This takeover was considered far more important than was the choice of presidential candidate, and the committee decided to take no position on who should win the race for the nomination, reasoning that the victor, no matter who he was, would be a silver man. Well aware of the overwhelming forces against them, many gold delegates were inclined to concede the platform battle.

Bryan arrived quietly and took rooms at a modest hotel; the Nebraskan later calculated that he spent less than $100 while in Chicago. He arrived convinced that he would win the nomination. He had already begun work on a speech. On the evening of July 5, Bryan was visited by a delegation of Coloradans, seeking his support for Senator Teller. They went away apologetically, not having known Bryan sought the nomination.

Candidates for the nomination

Despite the desire of silver delegates to nominate a candidate who shared their beliefs, and although several states instructed their delegates to vote for a specific candidate, there was no overwhelming favorite for the nomination going into the convention. With a two-thirds vote of the delegates needed to nominate, almost every silver delegate would have to vote for the same candidate to assure success, though any organized support from gold delegates would greatly damage a silver candidate's chances. The only gold man who put together any sort of campaign for the Democratic nomination was Treasury Secretary John G. Carlisle, but he withdrew in April, stating that he was more concerned about the platform of the party than who would lead it. However, as late as June, the gold forces, which still controlled the

The only gold man who put together any sort of campaign for the Democratic nomination was Treasury Secretary John G. Carlisle, but he withdrew in April, stating that he was more concerned about the platform of the party than who would lead it. However, as late as June, the gold forces, which still controlled the Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the governing body of the United States Democratic Party. The committee coordinates strategy to support Democratic Party candidates throughout the country for local, state, and national office, as well a ...

(DNC), continued to believe that the nominee could be pro-gold. Cleveland friend and former Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official respons ...

Donald M. Dickinson

Donald McDonald Dickinson (January 17, 1846 – October 15, 1917) was a lawyer and politician from the U.S. state of Michigan.

Biography

Dickinson was born in The town of Richland, Oswego County, New York, on January 17, 1846, the son of Asa C ...

wrote to the President in June 1896 hoping that the delegates would recognize "common sense" and be frightened at the thought of nominating a radical.

One of the leaders of the silver movement was Illinois Governor Altgeld; a native of Germany, he was constitutionally barred from the presidency by his foreign birth. Going into the convention, the two leading candidates for the nomination were former Congressman Bland, who had originated the Bland-Allison Act, and former Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

Governor Horace Boies

Horace Boies (December 7, 1827 – April 4, 1923) served as the 14th Governor of Iowa from 1890 to 1894 as a member of the United States Democratic Party. Boies was the only Democrat to serve in that position from 1855 to 1933, a period of 78 y ...

, with Bland considered the frontrunner. These were the only two candidates to put together organizations to try to secure delegate votes, though both efforts were cash-starved. Both men had electoral problems: Bland at age 61 was seen by some as a man whose time had passed; Boies was a former Republican who had once decried bimetallism. There were a large number of potential candidates seen as having less support; these included Vice President Adlai Stevenson of Illinois, Senator Joseph C. Blackburn

Joseph Clay Stiles Blackburn (October 1, 1838September 12, 1918) was a Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Representative and Senator from Kentucky. Blackburn, a skilled and spirited orator, was also a prominent trial lawyer known for h ...

of Kentucky, Senator Teller, and Bryan.

Silver advocates take control

Although Bryan had decided on a strategy to gain the nomination—to give a speech which would make him the logical candidate in the eyes of delegates—he faced obstacles along the way. For one thing, he began the 1896 convention without any official status—the Democratic National Committee, which made the initial determination of which delegations would be seated, had chosen the pro-gold Nebraskans to represent their state. Bryan had been waiting outside the committee room when his rivals were seated by a 27–23 vote; contemporary accounts state he was "somewhat surprised" at the result. The DNC's action could be reversed, but not until the convention's credentials committee reported. However, Barnes deemed the actions by the committee immaterial to the outcome due to the silver strength in the convention: Good luck favored Bryan—he was considered for various convention roles by the silverites, but each time was not selected. The temporary chairmanship, for example, would have permitted him to deliver thekeynote address

A keynote in public speaking is a talk that establishes a main underlying theme. In corporate or commercial settings, greater importance is attached to the delivery of a keynote speech or keynote address. The keynote establishes the framework f ...

. However, Bryan, lacking a seat at the start of the convention, could not be elected temporary chairman. Bryan considered this no loss at all; the focus of the convention was on the party platform and the debate which would precede its adoption. The platform would symbolize the repudiation of Cleveland and his policies after the insurgents' long struggle, and Bryan was determined to close the debate on the platform. Bryan, once seated, was Nebraska's representative to the Committee on Resolutions (generally called the "platform committee"), which allocated 80 minutes to each side in the debate and selected Bryan as one of the speakers. South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

Senator Benjamin Tillman

Benjamin Ryan Tillman (August 11, 1847 – July 3, 1918) was an American politician of the Democratic Party who served as governor of South Carolina from 1890 to 1894, and as a United States Senator from 1895 until his death in 1918. A whit ...

was to be the other pro-silver speaker, and originally wished to close the debate. However, the senator wanted 50 minutes to speak, too long for a closing address, and at Bryan's request agreed to open the debate instead. Accordingly, Bryan became the final speaker on the platform.

Delegates, as they waited for the committees to complete their work, spent much of the first two days listening to various orators. Of these, only Senator Blackburn, a silver supporter, sparked much reaction, and that only momentary. Delegates called for better-known speakers, such as Altgeld or Bryan, but were granted neither then; the Illinois governor declined, and the Nebraskan, once seated, spent much of his time away from the convention floor at the platform committee meeting at the Palmer House

The Palmer House – A Hilton Hotel is a historic hotel in Chicago's Loop area. It is a member of the Historic Hotels of America program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. The Palmer House was the city's first hotel with elevators ...

.

The debate on the platform opened at the start of the third day of the convention, July 9, 1896. The session was supposed to begin at 10:00 a.m., but as delegates, slowed by the long commute from the hotels to the Coliseum and fatigue from the first two days, did not arrive on time, proceedings did not begin until 10:45. Nevertheless, large crowds gathered outside the public entrances; the galleries were quickly packed. Once the convention came to order, Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

Senator James K. Jones, chair of the Committee on Resolutions, read the proposed platform to cheers by many delegates; the reading of the pro-gold minority report attracted less applause.

"Pitchfork Ben" Tillman lived up to his nickname with an incendiary address which began with a reference to his home state's role in beginning the Civil War. Although Tillman endorsed silver, his address was so laced with

"Pitchfork Ben" Tillman lived up to his nickname with an incendiary address which began with a reference to his home state's role in beginning the Civil War. Although Tillman endorsed silver, his address was so laced with sectionalism

Sectionalism is loyalty to one's own region or section of the country, rather than to the country as a whole.

Sectionalism occurs in many countries, such as in the United Kingdom, most notably in the constituent nation of Scotland, where various ...

that most silver delegates remained silent for fear of being seen as supporting him. Tillman's speech, scheduled to be the only one in support of silver except Bryan's, was so badly received that Senator Jones, who had not planned to speak, gave a brief address asserting that silver was a national issue.

Senator David B. Hill

David Bennett Hill (August 29, 1843October 20, 1910) was an American politician from New York who was the 29th Governor of New York from 1885 to 1891 and represented New York in the United States Senate from 1892 to 1897.

In 1892, he made an u ...

of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, a gold supporter, was next. As Hill moved to the podium, a reporter friend passed Bryan a note urging him to make a patriotic speech without hint of sectionalism; Bryan responded, "You will not be disappointed." Hill gave a calm speech defending the gold position, and swayed few delegates. He was followed by two other gold men, Senator William Vilas of Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

and former Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

Governor William E. Russell. Vilas gave a lengthy defense of the Cleveland administration's policies, so long that Russell, fearing that Vilas' speech would cut into his time, asked that the time given to the gold proponents be extended by ten minutes. Bryan consented, on condition that his own time was extended by the same amount; this was agreed to. "And I needed it for the speech I was to make." Bryan later wrote, "This was another unexpected bit of good fortune. I had never had such an opportunity before in my life and never expect to have again."

Vilas quickly lost his audience, which did not want to hear Cleveland defended. Russell's address was inaudible to most of the Coliseum; he was ill and died just over a week later. As the gold men spoke, Bryan ate a sandwich to settle his stomach; he was often nervous before major speeches. Another reporter approached him and asked him who he thought would win the nomination. "Strictly confidential, not to be quoted for publication: I will be."

Bryan addresses the convention

As Russell concluded, to strong applause from gold delegates, there was a buzz of anticipation as Bryan ascended to the podium. There was loud cheering as Bryan stood there, waiting for his audience to calm. Bryan's lecture tours had left him a well-known spokesman for silver. As yet, no one at the convention had effectively spoken for that cause, which was paramount to the delegates. According to political scientist Richard F. Bensel in his study of the 1896 Democratic convention, "Although the silver men knew they would win this fight, they nonetheless needed someone to tell them—and the gold men—why they must enshrine silver at the heart of the platform." Bensel noted, "The pump was more than primed, it was ready to explode." Bryan would say little that he had not said before—the text is similar to that of a speech he had given the previous week atCrete, Nebraska

Crete is a city in Saline County, Nebraska, United States. The population was 7,099 at the 2020 census.

History

The railroad was extended to the area in 1870, bringing settlers. In 1871, two rival towns merged to form a new town, which was name ...

—but he would give the convention its voice.

Bryan began softly,

Bryan's opening claimed no personal prestige for himself—but nevertheless placed him as the spokesman for silver. According to Bensel, the self-deprecation helped disarm the delegates. As Bryan was not deemed a major contender for the nomination, even delegates committed to a candidate could cheer him without seeming to betray their allegiance. Bryan then recounted the history of the silver movement; the audience, which had loudly demonstrated its approval of his opening statements, quieted. Throughout the speech, Bryan had the delegates in the palm of his hand; they cheered on cue. The Nebraskan later described the audience as like a trained choir. As he concluded his historical recitation, he reminded the silver delegates that they had come to crown their victory, "not to discuss, not to debate, but to enter up the judgment already rendered by the plain people of this country".

Bryan continued with language evoking the Civil War, telling his audience that "in this contest brother has been arrayed against brother, father against son." By then, as he spoke in a sincere tone, his voice sounded clearly and loudly through the hall. He denied, however that the contest was personal; he bore no ill-will towards those who supported the gold standard. However, he stated, facing towards the gold delegates, "when you come before us and tell us that we are about to disturb your business interests, we reply that you have disturbed our business interests by your course." The gold men, during the address, paid close attention and showed their appreciation for Bryan's oratory. Bryan then defended the right of silver supporters to make their argument against opposition from gold men, who were associated with financial interests, especially in the East. Although his statements nominally responded to a point made by Russell, Bryan had thought of the argument the previous evening, and had not used it in earlier speeches. He always regarded it as the best point he made during the speech, and only the ending caused more reaction from his listeners:

Through this passage, Bryan maintained the contrast between the common man and the city-dwelling elite. It was clear to listeners as he worked his way through the comparisons that he would refer to the farmer, and when he did, the hall exploded with sound. His sympathetic comparison contrasted the hardworking farmer with the city businessman, whom Bryan cast as a gambler. The galleries were filled with white as spectators waved handkerchiefs, and it was several minutes before he could continue. The police in the convention hall, not sharing the enthusiasm for silver, were described by the press (some of whose members were caught up in the frenzy) as standing as if they thought the audience was about to turn on them. When Bryan resumed, his comparison of miner with miser again electrified the audience; the uproar prevented him from continuing for several minutes. One farmer in the gallery had been about to leave rather than listen to Bryan, whom he deemed a Populist; he had been persuaded to stay. At Bryan's words, he threw his hat into the air, slapped the empty seat in front of him with his coat, and shouted, "My God! My God! My God!"

Bryan, having established the right of silver supporters to petition, explained why that petition was not to be denied:

With this call to action, Bryan abandoned any hint at compromise, and adopted the techniques of the radical, polarizing orator, finding no common ground between silver and gold forces. He then defended the remainder of the platform, though only speaking in general terms. He mocked McKinley, said by some to resemble

Bryan began softly,

Bryan's opening claimed no personal prestige for himself—but nevertheless placed him as the spokesman for silver. According to Bensel, the self-deprecation helped disarm the delegates. As Bryan was not deemed a major contender for the nomination, even delegates committed to a candidate could cheer him without seeming to betray their allegiance. Bryan then recounted the history of the silver movement; the audience, which had loudly demonstrated its approval of his opening statements, quieted. Throughout the speech, Bryan had the delegates in the palm of his hand; they cheered on cue. The Nebraskan later described the audience as like a trained choir. As he concluded his historical recitation, he reminded the silver delegates that they had come to crown their victory, "not to discuss, not to debate, but to enter up the judgment already rendered by the plain people of this country".

Bryan continued with language evoking the Civil War, telling his audience that "in this contest brother has been arrayed against brother, father against son." By then, as he spoke in a sincere tone, his voice sounded clearly and loudly through the hall. He denied, however that the contest was personal; he bore no ill-will towards those who supported the gold standard. However, he stated, facing towards the gold delegates, "when you come before us and tell us that we are about to disturb your business interests, we reply that you have disturbed our business interests by your course." The gold men, during the address, paid close attention and showed their appreciation for Bryan's oratory. Bryan then defended the right of silver supporters to make their argument against opposition from gold men, who were associated with financial interests, especially in the East. Although his statements nominally responded to a point made by Russell, Bryan had thought of the argument the previous evening, and had not used it in earlier speeches. He always regarded it as the best point he made during the speech, and only the ending caused more reaction from his listeners:

Through this passage, Bryan maintained the contrast between the common man and the city-dwelling elite. It was clear to listeners as he worked his way through the comparisons that he would refer to the farmer, and when he did, the hall exploded with sound. His sympathetic comparison contrasted the hardworking farmer with the city businessman, whom Bryan cast as a gambler. The galleries were filled with white as spectators waved handkerchiefs, and it was several minutes before he could continue. The police in the convention hall, not sharing the enthusiasm for silver, were described by the press (some of whose members were caught up in the frenzy) as standing as if they thought the audience was about to turn on them. When Bryan resumed, his comparison of miner with miser again electrified the audience; the uproar prevented him from continuing for several minutes. One farmer in the gallery had been about to leave rather than listen to Bryan, whom he deemed a Populist; he had been persuaded to stay. At Bryan's words, he threw his hat into the air, slapped the empty seat in front of him with his coat, and shouted, "My God! My God! My God!"

Bryan, having established the right of silver supporters to petition, explained why that petition was not to be denied:

With this call to action, Bryan abandoned any hint at compromise, and adopted the techniques of the radical, polarizing orator, finding no common ground between silver and gold forces. He then defended the remainder of the platform, though only speaking in general terms. He mocked McKinley, said by some to resemble Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

, noting that he was nominated on the anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

. The lengthy passage as he discussed the platform and the Republicans helped calm the audience, ensuring he would be heard as he reached his peroration

Dispositio is the system used for the organization of arguments in the context of Western classical rhetoric. The word is Latin, and can be translated as "organization" or "arrangement".

It is the second of five canons of classical rhetoric (the ...

. But Bryan first wished to tie the silver question to a greater cause:

He faced in the direction of the gold-dominated state delegations:

This statement attracted great cheering, and Bryan turned to rhetorically demolish the compromise position on bimetallism—that it should only be accomplished through international agreement:

Now, Bryan was ready to conclude the speech, and according to his biographer, Michael Kazin, step "into the headlines of American history".

As Bryan spoke his final sentence, recalling the Crucifixion of Jesus

The crucifixion and death of Jesus occurred in 1st-century Judea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, attested to by other ancient sources, and consid ...

, he placed his hands to his temples, fingers extended; with the final words, he extended his arms to his sides straight out to his body and held that pose for about five seconds as if offering himself as sacrifice for the cause, as the audience watched in dead silence. He then lowered them, descended from the podium, and began to head back to his seat as the stillness held.

Reception and nomination

Convention events

Bryan later described the silence as "really painful" and momentarily thought he had failed. As he moved towards his seat, the Coliseum burst into pandemonium. Delegates threw hats, coats, and handkerchiefs into the air. Others took up the standards with the state names on them with each delegation, and planted them by Nebraska's. Two alert police officers had joined Bryan as he left the podium, anticipating the crush. The policemen were swept away by the flood of delegates, who raised Bryan to their shoulders and carried him around the floor. ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' newspaper recorded, "bedlam broke loose, delirium reigned supreme."

It took about 25 minutes to restore order, and according to Bensel, "somewhere in the mass demonstration that was convulsing the convention hall, the transfer of sentiment from silver as a policy to Bryan as a presidential candidate took place". Newspaper accounts of the convention leave little doubt but that, had a vote been taken at that moment (as many were shouting to do), Bryan would have been nominated. Bryan was urged by Senator Jones to allow it, but refused, stating that if his boom would not last overnight, it would never last until November. He soon retired from the convention, returning to his hotel to await the outcome. The convention passed the platform in Bryan's absence and recessed.

The balloting began the following morning, July 10, with a two-thirds vote necessary to nominate. Bryan, who remained at his hotel, sent word to the Nebraska delegation to make no deals on his behalf. He stood second out of fourteen candidates in the first ballot, behind Bland. On the second ballot, Bryan still stood second, but had gained as other candidates had fallen away. The third ballot saw Bland still in the lead, but Bryan took the lead on the fourth ballot. According to Jones, it was clear that Bland could not win, and that Bryan could not be stopped. On the fifth ballot, the Illinois delegation, led by Governor Altgeld, switched its votes from Bland to Bryan. Other delegations, seeing that Bryan would be nominated, also switched, securing the victory. Nevertheless, he won the nomination without the votes of the gold delegates, most of whom either left the convention or refused to vote.

Press reaction

Most contemporary press accounts attributed Bryan's nomination to his eloquence, though in the case of Republican and other gold-favoring newspapers, they considered it his demagoguery. The pro-silver ''

Most contemporary press accounts attributed Bryan's nomination to his eloquence, though in the case of Republican and other gold-favoring newspapers, they considered it his demagoguery. The pro-silver ''Cleveland Plain Dealer

''The Plain Dealer'' is the major newspaper of Cleveland, Ohio, United States. In fall 2019, it ranked 23rd in U.S. newspaper circulation, a significant drop since March 2013, when its circulation ranked 17th daily and 15th on Sunday.

As of Ma ...

'' called Bryan's speech "an eloquent, stirring, and manly appeal". The ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television ar ...

'' reported that Bryan had lit the spark "which touched off the trail of gun-powder". The ''St. Louis Post-Dispatch

The ''St. Louis Post-Dispatch'' is a major regional newspaper based in St. Louis, Missouri, serving the St. Louis metropolitan area. It is the largest daily newspaper in the metropolitan area by circulation, surpassing the ''Belleville News-De ...

'' opined that with the speech, Bryan "just about immortalized himself".

According to the ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under publi ...

'', "Lunacy having dictated the platform, it was perhaps natural that hysteria should evolve the candidate." ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' disparaged Bryan as "the gifted blatherskite from Nebraska". The only paper to predict, after Bryan gave his speech, that he would not be nominated was ''The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

'', which stated, "Bryan has had his day". The ''Akron Journal and Republican'', no friend to Bryan, opined that "never probably has a national convention been swayed or influenced by a single speech as was the national Democratic convention".

Campaign and aftermath

The Pullman Company offered Bryan a private car for his trip home; he declined, not wishing to accept corporate favors. As he traveled by rail toLincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

, he saw farmers and others standing by the tracks, hoping for a glimpse of the new Democratic nominee. He received many letters from supporters, expressing their faith in him in stark terms. One Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

voter wrote, "God has sent you amongst our people to save the poor from starvation, and we no you will save us." A farmer in Iowa, in a letter to Bryan, stated, "You are the first big man that i ever wrote to."

When McKinley heard that Bryan was likely to be the nominee, he called the report "rot" and hung up the phone. The Republican nominee was slow to realize the surge of support for Bryan after the nomination, stating his view that the silver sentiment would be gone in a month. When McKinley and his advisers, such as industrialist and future senator

When McKinley heard that Bryan was likely to be the nominee, he called the report "rot" and hung up the phone. The Republican nominee was slow to realize the surge of support for Bryan after the nomination, stating his view that the silver sentiment would be gone in a month. When McKinley and his advisers, such as industrialist and future senator Mark Hanna

Marcus Alonzo Hanna (September 24, 1837 – February 15, 1904) was an American businessman and Republican politician who served as a United States Senator from Ohio as well as chairman of the Republican National Committee. A friend and pol ...

, realized that the views were more than transitory, they began intensive fundraising from corporations and the wealthy. The money went for speakers, pamphlets, and other means of conveying their "sound money" campaign to the voter. With far less money than McKinley, Bryan embarked on a nationwide campaign tour by train on a then-unprecedented scale. McKinley on the other hand, opted for a front porch campaign

A front porch campaign is a low-key electoral campaign used in American politics in which the candidate remains close to or at home to make speeches to supporters who come to visit. The candidate largely does not travel around or otherwise act ...

. Both men spoke to hundreds of thousands of people from their chosen venues.

Bryan's nomination divided the party. The dissidents nominated their own ticket; the split in the vote would contribute to Bryan's defeat. However, Bryan did gain the support of the Populists, as well as a convention of Silver Republicans. Bryan spoke on silver throughout the campaign; he rarely addressed other issues. Bryan won the South and most of the West, but McKinley's victories in the more populous Northeast and Midwest carried him to the presidency. The Democratic candidate failed to gain a majority of the labor vote; McKinley won in working-class areas as well as wealthy precincts. Although McKinley outpolled him by 600,000 votes, Bryan received more votes than any previous presidential candidate.

After McKinley's inauguration, increases in gold availability from new discoveries and improved refining methods led to a considerable increase in the money supply. Even so, in 1900, Congress passed the Gold Standard Act

The Gold Standard Act was an Act of the United States Congress, signed by President William McKinley and effective on March 14, 1900, defining the United States dollar by gold weight and requiring the United States Treasury to redeem, on demand ...

, formally placing the United States on that standard. Although Bryan ran again on a silver platform in the 1900 presidential election, the issue failed to produce the same resonance with the voters. McKinley won more easily than in 1896, making inroads in the silver West.

Legacy

Bryan's speech is considered one of the most powerful political addresses in American history. Stanley Jones, however, suggested that even if Bryan had never delivered it, he would still have been nominated. Jones deemed the Democrats likely to nominate a candidate who would appeal to the Populist Party, and Bryan had been elected to Congress with Populist support. According to rhetorical historian William Harpine in his study of the rhetoric of the 1896 campaign, "Bryan's speech cast a net for the true believers, but only for the true believers." Harpine suggested that, "by appealing in such an uncompromising way to the agrarian elements and to the West, Bryan neglected the national audience who would vote in the November election". Bryan's emphasis on agrarian issues, both in his speech and in his candidacy, may have helped cement voting patterns which kept the Democrats largely out of power until the 1930s.

Writer