Civil rights movement (1896–1954) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The civil rights movement (1896–1954) was a long, primarily

nonviolent

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

action to bring full

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

and equality under the law to all Americans. The era has had a lasting impact on

American society

The society of the United States is based on Western culture, and has been developing since long before the United States became a country with its own unique social and cultural characteristics such as dialect, music, arts, social habits, ...

– in its tactics, the increased

social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

and legal acceptance of civil rights, and in its exposure of the prevalence and cost of

racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

.

Two

US Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

decisions in particular serve as bookends of the movement: the 1896 ruling of ''

Plessy v Ferguson'', which upheld "

separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protecti ...

"

racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

as

constitutional

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

doctrine; and 1954's ''

Brown v Board of Education'', which overturned ''Plessy''. This was an era of new beginnings, in which some movements, such as

Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Sr. (17 August 188710 June 1940) was a Jamaican political activist, publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, and orator. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African ...

's

Universal Negro Improvement Association

The Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) is a black nationalist fraternal organization founded by Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican immigrant to the United States, and Amy Ashwood Garvey. The Pan-Africa ...

, were very successful but left little lasting legacy; while others, such as the

NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

's legal assault on

state-sponsored segregation, achieved modest results in its early years, as in, ''

Buchanan v. Warley

''Buchanan v. Warley'', 245 U.S. 60 (1917), is a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States addressed civil government-instituted racial segregation in residential areas. The Court held unanimously that a Louisville, Kentucky city ordin ...

'' (1917) (zoning), making some progress but also suffering setbacks, as in ''

Corrigan v. Buckley

''Corrigan v. Buckley'', 271 U.S. 323 (1926), was a US Supreme Court case in 1926 that ruled that the racially-restrictive covenant of multiple residents on S Street NW, between 18th Street and New Hampshire Avenue, in Washington, DC, was a legall ...

'' (1926) (housing), gradually building to key victories, including in ''

Smith v. Allwright

''Smith v. Allwright'', 321 U.S. 649 (1944), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court with regard to voting rights and, by extension, racial desegregation. It overturned the Texas state law that authorized parties to set thei ...

'' (1944) (voting), ''

Shelley v. Kraemer

''Shelley v. Kraemer'', 334 U.S. 1 (1948), is a List of landmark court decisions in the United States, landmark United States Supreme Court case that held that racially restrictive housing Covenant (law), covenants cannot legally be enforced.

The ...

'' (1948) (housing), ''

Sweatt v. Painter'' (1950) (schooling) and ''Brown''. In addition, the

Scottsboro Boys cases led to a pair of 1935 rulings in ''

Powell v. Alabama'', and ''

Norris v. Alabama'', that served to make anti-racism jurisprudence more prominent in the context of criminal justice.

Following the

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, the United States expanded the legal rights of

African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

.

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

passed, and enough states

ratified

Ratification is a principal's approval of an act of its agent that lacked the authority to bind the principal legally. Ratification defines the international act in which a state indicates its consent to be bound to a treaty if the parties inte ...

, an amendment ending slavery in 1865 — the

13th amendment to the US constitution. This amendment only outlawed slavery; it provided neither

citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

nor equal rights. In 1868, the

14th amendment was ratified by the states, granting African Americans citizenship, whereby all persons born in the US were extended

equal protection

The Equal Protection Clause is part of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause, which took effect in 1868, provides "''nor shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equa ...

under the laws of the

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

. The

15th amendment (ratified in 1870) stated that race could not be used as a condition to deprive men of the ability to vote. During

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

(1865–1877), northern troops occupied the South. Together with the

Freedmen's Bureau

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, usually referred to as simply the Freedmen's Bureau, was an agency of early Reconstruction, assisting freedmen in the South. It was established on March 3, 1865, and operated briefly as a ...

, they tried to administer and enforce the new constitutional amendments. Many Black leaders were elected to local and state offices, and many others organized community groups, especially to support education.

Reconstruction ended following the

Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Wormley Agreement or the Bargain of 1877, was an unwritten deal, informally arranged among members of the United States Congress, to settle the intensely disputed 1876 presidential election between Ruth ...

between northern and southern White elites. In exchange for deciding the

contentious presidential election in favor of

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

, supported by northern states, over his opponent,

Samuel J. Tilden

Samuel Jones Tilden (February 9, 1814 – August 4, 1886) was an American politician who served as the 25th Governor of New York and was the Democratic candidate for president in the disputed 1876 United States presidential election. Tilden was ...

, the compromise called for the withdrawal of northern troops from the South. This followed violence and fraud in southern elections from 1868 to 1876, which had reduced Black

voter turnout

In political science, voter turnout is the participation rate (often defined as those who cast a ballot) of a given election. This can be the percentage of registered voters, eligible voters, or all voting-age people. According to Stanford Unive ...

and enabled southern White

Democrats to regain power in

state legislatures across the South. The compromise and withdrawal of federal troops meant that such Democrats had more freedom to impose and enforce

discriminatory practices. Many African Americans responded to the withdrawal of federal troops by leaving the South in the

Kansas Exodus of 1879.

The

Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as " Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reco ...

, who spearheaded Reconstruction, had attempted to eliminate both governmental and private discrimination by legislation. Such effort was largely ended by the

Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

's decision in the

civil rights cases

The ''Civil Rights Cases'', 109 U.S. 3 (1883), were a group of five landmark cases in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments did not empower Congress to outlaw racial discrimination by pr ...

, in which the court held that the 14th Amendment did not give

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

power to outlaw racial discrimination by private individuals or businesses.

Key events

Segregation

The Supreme Court's decision in ''

Plessy v Ferguson'' (1896) upheld state-mandated discrimination in public transportation under the "

separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protecti ...

" doctrine. As Justice

Harlan, the only member of the Court to dissent from the decision, predicted:

If a state can prescribe, as a rule of civil conduct, that whites and blacks shall not travel as passengers in the same railroad coach, why may it not so regulate the use of the streets of its cities and towns as to compel white citizens to keep on one side of a street, and black citizens to keep on the other? Why may it not, upon like grounds, punish whites and blacks who ride together in street cars or in open vehicles on a public road or street?

The ''Plessy'' decision did not address an earlier Supreme Court case, ''

Yick Wo v. Hopkins

''Yick Wo v. Hopkins'', 118 U.S. 356 (1886), was the first case where the United States Supreme Court ruled that a law that is race-neutral on its face, but is administered in a prejudicial manner, is an infringement of the Equal Protection Claus ...

'' (1886),

involving discrimination against Chinese immigrants, that held that a law that is

race-neutral on its face, but is administered in a prejudicial manner, is an infringement of the

Equal Protection Clause

The Equal Protection Clause is part of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause, which took effect in 1868, provides "''nor shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal ...

in the

Fourteenth Amendment to the

US Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the nation ...

.

While in the 20th century, the Supreme Court began to overturn state statutes that disenfranchised African Americans, as in ''

Guinn v. United States'' (1915), with ''Plessy'', it upheld segregation that Southern states enforced in nearly every other sphere of public and private life.

The Court soon extended ''Plessy'' to uphold segregated schools. In ''

Berea College v. Kentucky

''Berea College v. Kentucky'', 211 U.S. 45 (1908), was a significant case argued before the United States Supreme Court that upheld the rights of states to prohibit private educational institutions chartered as corporations from admitting both bla ...

'', the Court upheld a Kentucky statute that barred

Berea College

Berea College is a private liberal arts work college in Berea, Kentucky. Founded in 1855, Berea College was the first college in the Southern United States to be coeducational and racially integrated. Berea College charges no tuition; every adm ...

, a private institution, from teaching both black and white students in an integrated setting. Many states, particularly in the South, took ''Plessy'' and ''Berea'' as blanket approval for restrictive laws, generally known as ''

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

'', that created second-class status for African Americans.

In many cities and towns, African Americans were not allowed to share a

taxi

A taxi, also known as a taxicab or simply a cab, is a type of vehicle for hire with a driver, used by a single passenger or small group of passengers, often for a non-shared ride. A taxicab conveys passengers between locations of their choice ...

with whites or enter a building through the same entrance. They had to drink from separate water fountains, use separate restrooms, attend separate schools, be buried in separate cemeteries and swear on separate

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

s. They were excluded from restaurants and public libraries. Many parks barred them with signs that read "Negroes and dogs not allowed." One municipal zoo listed separate visiting hours.

The etiquette of racial segregation was harsher, particularly in the South. African Americans were expected to step aside to let a white person pass, and black men dared not look any white woman in the eye. Black men and women were addressed as "Tom" or "Jane," but rarely as "

Mr.

''Mister'', usually written in its contracted form ''Mr.'' or ''Mr'', is a commonly used English honorific for men without a higher honorific, or professional title, or any of various designations of office. The title 'Mr' derived from earlier ...

" or "

Miss

Miss (pronounced ) is an English language honorific typically used for a girl, for an unmarried woman (when not using another title such as "Doctor" or "Dame"), or for a married woman retaining her maiden name. Originating in the 17th century, it ...

" or "

Mrs.

Mrs. (American English) or Mrs (British English; standard English pronunciation: ) is a commonly used English honorific for women, usually for those who are married and who do not instead use another title (or rank), such as ''Doctor'', ''Profe ...

," titles then widely in use for adults. Whites referred to black men of any age as "boy" and a black woman as "girl;" both often were called by labels such as "

nigger

In the English language, the word ''nigger'' is an ethnic slur used against black people, especially African Americans. Starting in the late 1990s, references to ''nigger'' have been progressively replaced by the euphemism , notably in cases ...

" or "

colored

''Colored'' (or ''coloured'') is a racial descriptor historically used in the United States during the Jim Crow, Jim Crow Era to refer to an African Americans, African American. In many places, it may be considered a Pejorative, slur, though it ...

."

Less formal social segregation in the North began to yield to change. In 1941, however, the

United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

, based in segregated Maryland,

refused to play a

lacrosse

Lacrosse is a team sport played with a lacrosse stick and a lacrosse ball. It is the oldest organized sport in North America, with its origins with the indigenous people of North America as early as the 12th century. The game was extensively ...

game against

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

because Harvard's team included a black player.

Jackie Robinson's Major League Baseball debut, 1947

Jackie Robinson

Jack Roosevelt Robinson (January 31, 1919 – October 24, 1972) was an American professional baseball player who became the first African American to play in Major League Baseball (MLB) in the modern era. Robinson broke the baseball color line ...

was a sports pioneer of the civil rights movement, best known for becoming the first African American to play professional sports in the major leagues.

Robinson debuted with the

Brooklyn Dodgers

The Brooklyn Dodgers were a Major League Baseball team founded in 1884 as a member of the American Association (19th century), American Association before joining the National League in 1890. They remained in Brooklyn until 1957, after which the ...

of

Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (AL), ...

on April 15, 1947. His first major league game came one year before the

US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

was integrated, seven years before ''Brown v. Board of Education'', eight years before

Rosa Parks

Rosa Louise McCauley Parks (February 4, 1913 – October 24, 2005) was an American activist in the civil rights movement best known for her pivotal role in the Montgomery bus boycott. The United States Congress has honored her as "the ...

, and before

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

was leading the movement.

Political opposition

Lily-white movement

Following the Civil War, black leaders made substantial progress in establishing representation in the

Republican Party.

Among the most prominent was

Norris Wright Cuney

Norris Wright Cuney, or simply Wright Cuney, (May 12, 1846March 3, 1898) was an American politician, businessman, union leader, and advocate for the rights of African-Americans in Texas. Following the American Civil War, he became active in G ...

, the Republican Party chairman in the late 19th century

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

. These gains led to substantial discomfort among many white voters, who generally supported the

Democrats. During the 1888 Texas Republican Convention, Cuney coined the term ''lily-white movement'' to describe efforts by white conservatives to oust black people from positions of party leadership and incite riots to divide the party. Increasingly organized efforts by this movement gradually eliminated black leaders from the party. The writer Michael Fauntroy contends that the effort was coordinated with Democrats as part of a larger movement toward

disenfranchisement

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

of black people in the South at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century by increasing restrictions in voter registration rules.

Following biracial victories by a

Populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

-Republican slates in several states, by the late 19th century the Democratic Party had regained control of most state legislatures in the South. From 1890 to 1908, they accomplished disenfranchisement of blacks and, in some states, many poor whites. Despite repeated legal challenges and some successes by the

NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

, the Democrats continued to devise new ways to limit black electoral participation, such as

white primaries

White primaries were primary elections held in the Southern United States in which only white voters were permitted to participate. Statewide white primaries were established by the state Democratic Party units or by state legislatures in South Ca ...

, through the 1960s.

Nationally, the Republican Party tried to respond to black interests.

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, president 1901–1909, had a mixed record on race relations. He relied extensively on the backstage advice of

Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

regarding patronage appointments across the South. He publicly invited Washington to dinner at the White House, thereby challenging racist attitudes. On the other hand, he began the system of segregating federal employees; and he cracked down on black soldiers who refused to testify against each other in the

Brownsville Affair of 1906. In order to defeat his successor

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

for the Republican nomination in 1912, Roosevelt pursued a Lily-white policy in the South. This new progressive party of 1912 was supportive of black rights in the North, but excluded all black members in the South.

Republicans in Congress repeatedly proposed federal legislation to prohibit

lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

, which was always defeated by the Southern block. In 1920 Republicans made opposition to

lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

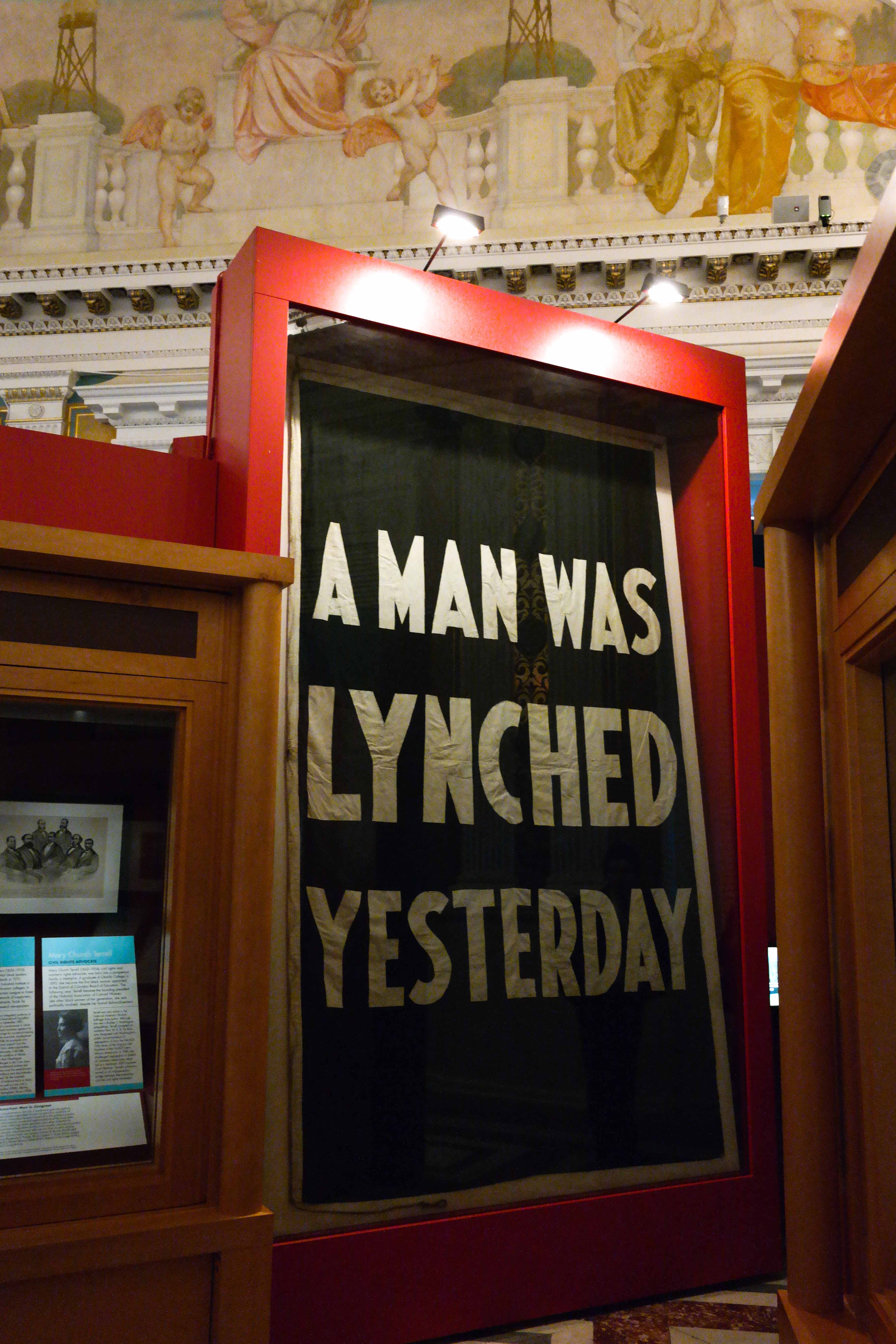

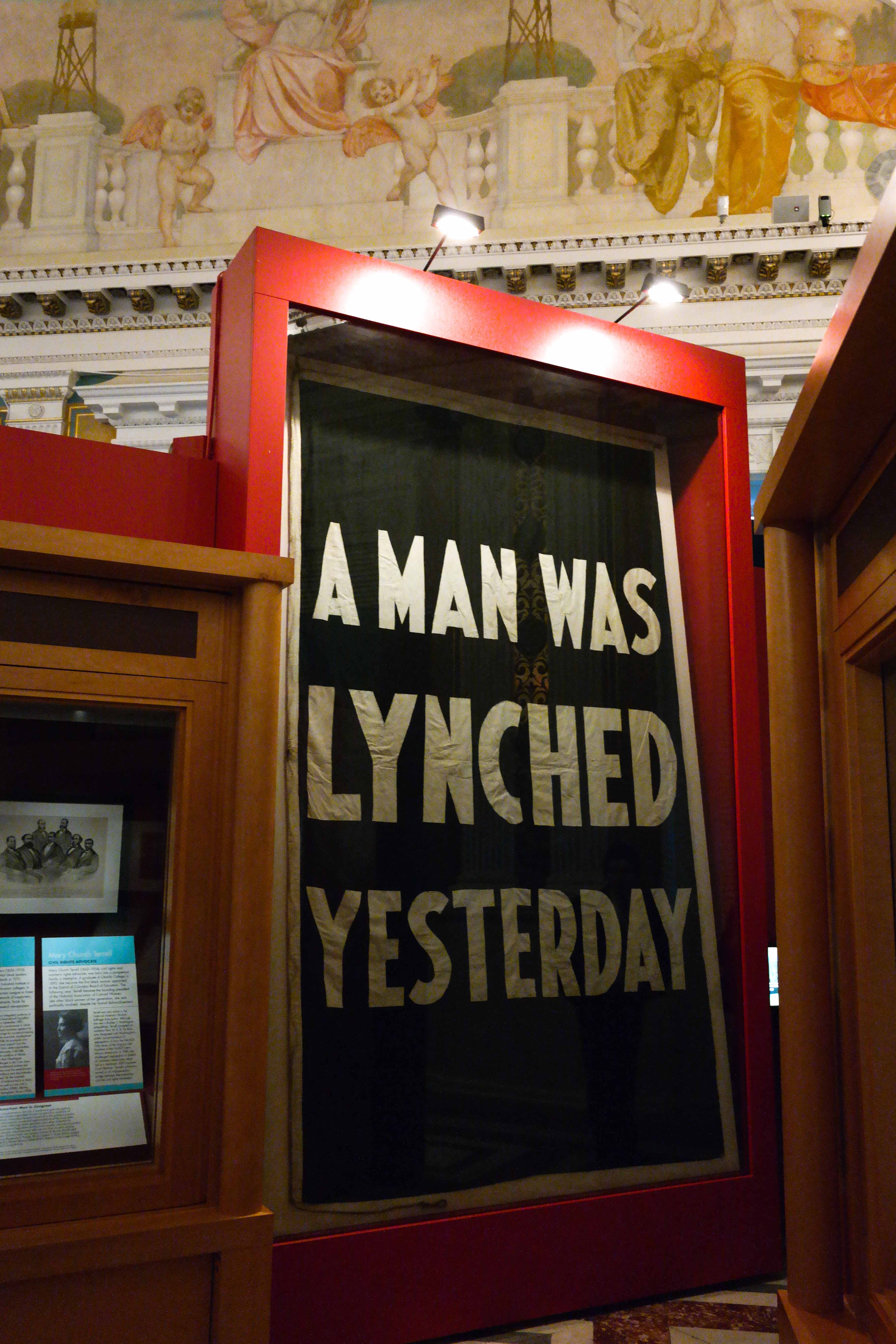

part of their platform at the Republican National Convention. Lynchings, primarily of black men in the South, had increased in the decades around the turn of the 20th century.

Leonidas C. Dyer

Leonidas Carstarphen Dyer (June 11, 1871 – December 15, 1957) was an American politician, reformer, civil rights activist, and military officer. A Republican, he served eleven terms in the U.S. Congress as a U.S. Representative from Missouri ...

, a white Republican Representative from

St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

, worked with the NAACP to introduce an anti-lynching bill into the House, where he gained strong passage in 1922. His effort was defeated by the Southern Democratic block in the Senate, which

filibustered

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

the bill that year, and in 1923 and 1924.

Disenfranchisement

Opponents of black civil rights used economic reprisals and frequently violence at the polls in the 1870s and 1880s to discourage blacks from registering to vote or voting. Paramilitary groups such as the Red Shirts in Mississippi and the Carolinas, and the White League in Louisiana, practiced open intimidation on behalf of the Democratic Party. By the turn of the 20th century, white Democratic-dominated Southern legislatures

disfranchised nearly all age-eligible African-American voters through a combination of statute and constitutional provisions. While requirements applied to all citizens, in practice, they were targeted at blacks and poor whites (and

Mexican Americans

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexica ...

in Texas), and subjectively administered. The feature "Turnout in Presidential and Midterm Elections" at the following University of Texas website devoted to politics, shows the drastic drop in voting as these provisions took effect in Southern states compared to the rest of the US, and the longevity of the measures.

Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

passed a new constitution in 1890 that included provisions for

poll taxes

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments fr ...

,

literacy test

A literacy test assesses a person's literacy skills: their ability to read and write have been administered by various governments, particularly to immigrants. In the United States, between the 1850s and 1960s, literacy tests were administered t ...

s (which depended on the arbitrary decisions of white registrars), and complicated record keeping to establish residency, which severely reduced the number of blacks who could register. It was litigated before the Supreme Court. In 1898, in ''

Williams v. Mississippi

''Williams v. Mississippi'', 170 U.S. 213 (1898), is a Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court case that reviewed provisions of the Constitution of Mississippi#1890 constitution, 1890 Mississippi constitution and its statute ...

'', the Court upheld the state. Other Southern states quickly adopted the "Mississippi plan", and from 1890 to 1908, ten states adopted new constitutions with provisions to disfranchise most blacks and many poor whites. States continued to disfranchise these groups for decades, until mid-1960s federal legislation provided for oversight and enforcement of constitutional voting rights.

Blacks were most adversely affected, and in many southern states black voter turnout dropped to zero. Poor whites were also disfranchised. In Alabama, for instance, by 1941, 600,000 poor whites had been disfranchised, as well as 520,000 blacks.

It was not until the 20th century that litigation by African Americans on such provisions began to meet some success before the Supreme Court. In 1915 in ''

Guinn v. United States'', the Court declared Oklahoma's '

grandfather clause

A grandfather clause, also known as grandfather policy, grandfathering, or grandfathered in, is a provision in which an old rule continues to apply to some existing situations while a new rule will apply to all future cases. Those exempt from t ...

' to be unconstitutional. Although the decision affected all states that used the grandfather clause, state legislatures quickly employed new devices to continue disfranchisement. Each provision or statute had to be litigated separately. The

NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

, founded in 1909, litigated against many such provisions.

One device which the Democratic Party began to use more widely in Southern states in the early 20th century was the

white primary

White primaries were primary elections held in the Southern United States in which only white voters were permitted to participate. Statewide white primaries were established by the state Democratic Party units or by state legislatures in South C ...

, which served for decades to disfranchise the few blacks who managed to get past barriers of voter registration. Barring blacks from voting in the Democratic Party primaries meant they had no chance to vote in the only competitive contests, as the Republican Party was then weak in the South. White primaries were not struck down by the Supreme Court until ''

Smith v. Allwright

''Smith v. Allwright'', 321 U.S. 649 (1944), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court with regard to voting rights and, by extension, racial desegregation. It overturned the Texas state law that authorized parties to set thei ...

'' in 1944.

Criminal law and lynching

In 1880, the United States Supreme Court ruled in ''

Strauder v. West Virginia

''Strauder v. West Virginia'', 100 U.S. 303 (1880), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States about racial discrimination and United States constitutional criminal procedure. ''Strauder'' was the first instance where the ...

'', that African Americans could not be excluded from juries. However, beginning in 1890 with new state constitutions and electoral laws, the South effectively disfranchised blacks in the South, which routinely disqualified them for jury duty which was limited to voters. This left them at the mercy of a white justice system arrayed against them. In some states, particularly

Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, the state used the criminal justice system to reestablish a form of

peon

Peon (English , from the Spanish ''peón'' ) usually refers to a person subject to peonage: any form of wage labor, financial exploitation, coercive economic practice, or policy in which the victim or a laborer (peon) has little control over emp ...

age, through the convict-lease system. The state sentenced black males to years of imprisonment, which they spent working without pay. The state leased prisoners to private employers, such as

Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company

The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (1852–1952), also known as TCI and the Tennessee Company, was a major American steel manufacturer with interests in coal mining, coal and iron ore mining and railroad operations. Originally based en ...

, a subsidiary of

United States Steel Corporation

United States Steel Corporation, more commonly known as U.S. Steel, is an American integrated steel producer headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with production operations primarily in the United States of America and in several countries ...

, which paid the state for their labor. Because the state made money, the system created incentives for the jailing of more men, who were disproportionately black. It also created a system in which treatment of prisoners received little oversight.

Extrajudicial punishment

Extrajudicial punishment is a punishment for an alleged crime or offense which is carried out without legal process or supervision by a court or tribunal through a legal proceeding.

Politically motivated

Extrajudicial punishment is often a fea ...

was more brutal. During the last decade of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century, white vigilante mobs

lynched

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

thousands of black males, sometimes with the overt assistance of state officials, mostly within the South. No whites were charged with crimes in any of those murders. Whites were so confident of their immunity from prosecution for lynching that they not only photographed the victims, but made postcards out of the pictures.

The

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

, which had largely disappeared after a brief violent career in the early years of Reconstruction, reappeared in 1915. It grew mostly in industrializing cities of the South and Midwest that underwent the most rapid growth from 1910 to 1930. Social instability contributed to racial tensions that resulted from severe competition for jobs and housing. People joined KKK groups because they were anxious about their place in American society, as cities were rapidly changed by a combination of industrialization, migration of blacks and whites from the rural South, and waves of increased immigration from mostly rural

southern and

eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

.

Initially the KKK presented itself as another fraternal organization devoted to betterment of its members. The KKK's revival was inspired in part by the movie ''

Birth of a Nation'', which glorified the earlier Klan and

drama

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance: a play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a genre of poetry in general, the dramatic mode has been ...

tized the racist stereotypes concerning blacks of that era. The Klan focused on political mobilization, which allowed it to gain power in states such as

Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, on a platform that combined

racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

with anti-immigrant,

anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

,

anti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its Hierarchy of the Catholic Church, clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestantism, Protestant states, ...

and anti-union rhetoric, but also supported lynching. It reached its peak of membership and influence about 1925, declining rapidly afterward as opponents mobilized.

Republicans repeatedly introduced bills in the House to make

lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged transgressor, punish a convicted transgressor, or intimidate people. It can also be an ex ...

a federal crime, but they were defeated by the Southern block. In 1920 the Republicans made an

anti-lynching bill part of their platform and achieved passage in the House by a wide margin.

Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally mu ...

in the Senate repeatedly filibustered the bill to prevent a vote, and defeated it in the 1922, 1923 and 1924 sessions as they held the rest of the legislative program hostage.

Farmers and blue-collar workers

White society also kept blacks in a position of economic subservience or marginality. Most black farmers in the South by the early 20th century worked as

sharecroppers

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

or

tenant farmer

A tenant farmer is a person (farmer or farmworker) who resides on land owned by a landlord. Tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and management, ...

s, and relatively few were

landowners

In common law systems, land tenure, from the French verb "tenir" means "to hold", is the legal regime in which land owned by an individual is possessed by someone else who is said to "hold" the land, based on an agreement between both individual ...

.

Employers and labor unions generally restricted African Americans to the worst paid and least desirable jobs. Because of the lack of steady, well-paid jobs, relatively undistinguished positions, such as those with the

Pullman Porter

Pullman porters were men hired to work for the railroads as porters on sleeping cars. Starting shortly after the American Civil War, George Pullman sought out former slaves to work on his sleeper cars. Their job was to carry passengers’ bagga ...

or as hotel doorman, became prestigious positions in black communities in the North. The expansion of railroads meant that they recruited in the South for laborers, and tens of thousands of blacks moved North to work with the

Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR), legal name The Pennsylvania Railroad Company also known as the "Pennsy", was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named ...

, for example, during the period of the

Great Migration. In 1900 Reverend Matthew Anderson, speaking at the annual

Hampton Negro Conference

The Hampton Negro Conference was a series of conferences held between 1897 and 1912 hosted by the Hampton University, Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) in Hampton, Virginia. It brought together Black leaders from across the Southern Unite ...

in Virginia, said that "...the lines along most of the avenues of wage earning are more rigidly drawn in the North than in the South. There seems to be an apparent effort throughout the North, especially in the cities to debar the colored worker from all the avenues of higher remunerative labor, which makes it more difficult to improve his economic condition even than in the South."

The Golden Age of Black Entrepreneurship

The nadir of race relations was reached in the early 20th century, in terms of political and legal rights. Blacks were increasingly segregated. Cut off from the larger white community, however, black entrepreneurs succeeded in establishing flourishing businesses that catered to a black clientele, including professionals. In urban areas, north and south, the size and income of the black population was growing, providing openings for a wide range of businesses, from barbershops to

insurance companies

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

. Undertakers had a special niche in their communities, and often played a political role, as they were widely known and knew many of their constituents.

Historian Juliet Walker calls the 1900s-1930s the "Golden age of black business." According to the

National Negro Business League

The National Negro Business League (NNBL) was an American organization founded in Boston in 1900 by Booker T. Washington to promote the interests of African-American businesses. The mission and main goal of the National Negro Business League was ...

, the number of black-owned businesses doubled rapidly, from 20,000 in 1900 to 40,000 in 1914. There were 450 undertakers in 1900, rising to 1000 in this time period. The number of black-owned drugstores rose from 250 to 695. Local retail merchants—most of them quite small—jumped from 10,000 to 25,000.

[Meier, August. ]963

Year 963 ( CMLXIII) was a common year starting on Thursday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* March 15 – Emperor Romanos II dies at age 25, probably of poison admini ...

1966. ''Negro Thought in America, 1880–1915: Racial Ideologies in the Age of Booker T. Washington'' (2nd ed.). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press

The University of Michigan Press is part of Michigan Publishing at the University of Michigan Library. It publishes 170 new titles each year in the humanities and social sciences. Titles from the press have earned numerous awards, including L ...

. p. 140. One of the most famous entrepreneurs was

Madame C.J. Walker

Madam C.J. Walker (born Sarah Breedlove; December 23, 1867 – May 25, 1919) was an African American entrepreneur, philanthropist, and political and social activist. She is recorded as the first female self-made millionaire in America in the ''Gu ...

(1867–1919), who built a national

franchise business called

Madame C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, based on her development of the first successful hair straightening process.

Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

, who ran the National Negro Business League and was president of the

Tuskegee Institute

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was de ...

, was the most prominent promoter of black business. He traveled from city to city to sign up local entrepreneurs into the national league.

Charles Clinton Spaulding

Charles Clinton Spaulding (August 1, 1874 – August 1, 1952) was an American business leader. For close to thirty years, he presided over North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company, which became America's largest black-owned business, with ass ...

(1874–1952), an ally of Washington, was the most prominent black American business leader of his day. Behind the scenes he was an advisor to President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

in the 1930s, with the goal of promoting a black political leadership class. He founded

North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company

NC Mutual (originally the North Carolina Mutual and Provident Association and later North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company) was an American life insurance company located in downtown Durham, North Carolina and one of the most influential A ...

, which became America's largest black-owned business, with assets of over $40 million at his death.

Although black business flourished in urban areas, it was severely handicapped in the rural South where the great majority of blacks lived. Blacks were farmers who depended on one cash crop, typically cotton or tobacco. They chiefly traded with local white merchants. The primary reason was that the local country stores provided credit, that is the provided supplies the farm and family needed, including tools, seeds, food and clothing, on a credit basis until the bill was paid off at harvest time. Black businessmen had too little access to credit to enter this business. Indeed, there were only a small number of wealthy blacks; overwhelmingly they were real estate speculators in the fast-growing cities, typified by

Robert Church in Memphis.

Division of Negro Affairs in the Department of Commerce

Minority entrepreneurship entered the national agenda in 1927 when

Secretary of Commerce

The United States secretary of commerce (SecCom) is the head of the United States Department of Commerce. The secretary serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all matters relating to commerce. The secretary rep ...

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

set up a Division of Negro Affairs to provide advice, and disseminate information to both white and black businessmen on how to reach the black consumer. Entrepreneurship was not on the

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

agenda of

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

. However, when he turned to war preparation in 1940, he used this agency to help black business secure defense contracts. Black businesses had not been oriented toward manufacturing, and generally were too small to secure any major contracts.

President Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

disbanded the agency in 1953.

Executive Orders for non-discriminatory hiring by defense contractors

President Roosevelt issued two

Executive Orders

''Executive Orders'' is a techno-thriller novel, written by Tom Clancy and released on July 1, 1996. It picks up immediately where the final events of ''Debt of Honor'' (1994) left off, and features now-U.S. President Jack Ryan as he tries to d ...

directing defense contractors to hire, promote and fire without regard for racial discrimination. In areas such as West Coast shipyards and other industries, blacks began to gain more of the skilled and higher-paying jobs and supervisory positions.

The Black church

As the center of community life, Black churches were integral leaders and organizers in the

civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

. Their history as a focal point for the Black community and as a link between the Black and White worlds made them natural for this purpose.

This period saw the maturing of independent black churches, whose leaders were usually also strong community leaders. Blacks had left white churches and the

Southern Baptist Convention

The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) is a Christian denomination based in the United States. It is the world's largest Baptist denomination, and the largest Protestant and second-largest Christian denomination in the United States. The wor ...

to set up their own churches free of white supervision immediately during and after the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. With the help of northern associations, they quickly began to set up state conventions and, by 1895, joined several associations into the black

National Baptist Convention, the first of that denomination among blacks. In addition, independent black denominations, such as the

African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church and

AME Zion Church #REDIRECT AME #REDIRECT AME

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from ambiguous page ...

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from ambiguous page ...

, had made hundreds of thousands of converts in the South, founding AME churches across the region. The churches were centers of community activity, especially organizing for education.

Rev.

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

was but one of many notable Black

ministers

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of governme ...

involved in the later civil rights movement.

Ralph David Abernathy

Ralph David Abernathy Sr. (March 11, 1926 – April 17, 1990) was an American civil rights activist and Baptist minister. He was ordained in the Baptist tradition in 1948. As a leader of the civil rights movement, he was a close friend and ...

,

James Bevel

James Luther Bevel (October 19, 1936 – December 19, 2008) was a minister and leader of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement in the United States. As a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and then as its Director of Direct ...

,

Bernard Lee

John Bernard Lee (10 January 190816 January 1981) was an English actor, best known for his role as M in the first eleven Eon-produced James Bond films. Lee's film career spanned the years 1934 to 1979, though he had appeared on stage from t ...

,

Joseph Lowery

Joseph Echols Lowery (October 6, 1921 – March 27, 2020) was an American minister in the United Methodist Church and leader in the civil rights movement. He founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference with Martin Luther King Jr. and ot ...

,

Fred Shuttlesworth

Frederick Lee Shuttlesworth (born Fred Lee Robinson, March 18, 1922 – October 5, 2011) was a U.S. civil rights activist who led the fight against segregation and other forms of racism as a minister in Birmingham, Alabama. He was a co-founder o ...

, and

C. T. Vivian

Cordy Tindell Vivian (July 30, 1924July 17, 2020) was an American minister, author, and close friend and lieutenant of Martin Luther King Jr. during the civil rights movement. Vivian resided in Atlanta, Georgia, and founded the C. T. Vivian Lead ...

are among the many notable minister-activists. They were especially important during the later years of the movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

Educational growth

Continuing to see education as the primary route of advancement and critical for the race, many talented blacks went into teaching, which had high respect as a profession. Segregated schools for blacks were underfunded in the South and ran on shortened schedules in rural areas. Despite segregation, in Washington, DC by contrast, as Federal employees, black and white teachers were paid on the same scale. Outstanding black teachers in the North received advanced degrees and taught in highly regarded schools, which trained the next generation of leaders in cities such as Chicago, Washington, and New York, whose black populations had increased in the 20th century due to the

Great Migration.

Education was one of the major achievements of the black community in the 19th century. Blacks in

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

governments had supported the establishment of public education in every Southern state. Despite the difficulties, with the enormous eagerness of

freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

for education, by 1900 the African-American community had trained and put to work 30,000 African-American teachers in the South. In addition, a majority of the black population had achieved

literacy

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, huma ...

. Not all the teachers had a full 4-year

college degree

An academic degree is a qualification awarded to students upon successful completion of a course of study in higher education, usually at a college or university. These institutions commonly offer degrees at various levels, usually including unde ...

in those years, but the shorter terms of normal schools were part of the system of teacher training in both the North and the South to serve the many new communities across the frontier. African-American teachers got many children and adults started on education.

Northern alliances had helped fund normal schools and colleges to teach African-American teachers, as well as create other professional classes. The

American Missionary Association

The American Missionary Association (AMA) was a Protestant-based abolitionist group founded on in Albany, New York. The main purpose of the organization was abolition of slavery, education of African Americans, promotion of racial equality, and ...

, supported largely by the

Congregational

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

and

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

churches, had helped fund and staff numerous private schools and colleges in the South, who collaborated with black communities to train generations of teachers and other leaders. Major 20th-century

industrialists

A business magnate, also known as a tycoon, is a person who has achieved immense wealth through the ownership of multiple lines of enterprise. The term characteristically refers to a powerful entrepreneur or investor who controls, through perso ...

, such as

George Eastman

George Eastman (July 12, 1854March 14, 1932) was an American entrepreneur who founded the Kodak, Eastman Kodak Company and helped to bring the photographic use of roll film into the mainstream. He was a major philanthropist, establishing the ...

of

Rochester, New York

Rochester () is a City (New York), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, the county seat, seat of Monroe County, New York, Monroe County, and the fourth-most populous in the state after New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffalo, ...

, acted as

philanthropists

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the Public good (economics), public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private goo ...

and made substantial donations to black educational institutions such as

Tuskegee Institute

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was de ...

.

In 1862, the

U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is Bicameralism, bicameral, composed of a lower body, the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives, and an upper body, ...

passed the ''

Morrill Act

The Morrill Land-Grant Acts are United States statutes that allowed for the creation of land-grant colleges in U.S. states using the proceeds from sales of federally-owned land, often obtained from indigenous tribes through treaty, cession, or se ...

'', which established federal funding of a

land grant college

A land-grant university (also called land-grant college or land-grant institution) is an institution of higher education in the United States designated by a state to receive the benefits of the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890.

Signed by Abraha ...

in each state, but 17 states refused to admit black students to their land grant colleges. In response, Congress enacted the second ''Morrill Act'' of 1890, which required states that excluded blacks from their existing land grant colleges to open separate institutions and to equitably divide the funds between the schools. The colleges founded in response to the second ''Morill Act'' became today's public

historically black colleges and universities

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. ...

(HBCUs) and, together with the private HBCUs and the unsegregated colleges in the North and West, provided higher educational opportunities to African Americans. Federally funded

extension

Extension, extend or extended may refer to:

Mathematics

Logic or set theory

* Axiom of extensionality

* Extensible cardinal

* Extension (model theory)

* Extension (predicate logic), the set of tuples of values that satisfy the predicate

* E ...

agents from the land grant colleges spread knowledge about scientific agriculture and home economics to rural communities with agents from the HBCUs focusing on black farmers and families.

In the 19th century, blacks formed fraternal organizations across the South and the North, including an increasing number of women's clubs. They created and supported institutions that increased education, health and welfare for black communities. After the turn of the 20th century, black men and women also began to found their own college fraternities and sororities to create additional networks for lifelong service and collaboration. For example,

Alpha Phi Alpha

Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. () is the oldest intercollegiate historically African American fraternity. It was initially a literary and social studies club organized in the 1905–1906 school year at Cornell University but later evolved int ...

the first black intercollegiate fraternity was founded at

Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

in 1906. These were part of the new organizations that strengthened independent community life under segregation.

Tuskegee took the lead in spreading industrial education to Africa, typically in cooperation with church missionary efforts.

Libraries

Development of library services for blacks, particularly in the South, was slow moving and lackluster. At the turn of the 20th century there were only a few available and they were largely housed on private grounds.

Western Colored Branch established in 1908, the first

public library

A public library is a library that is accessible by the general public and is usually funded from public sources, such as taxes. It is operated by librarians and library paraprofessionals, who are also Civil service, civil servants.

There are ...

in the South for African Americans, was the first of its kind to be funded by a

Carnegie grant. Following the formation of the Western Colored Branch, other such facilities were constructed, particularly in association with

black school

Black schools, also referred to as "colored" schools, were racially segregated schools in the United States that originated after the American Civil War and Reconstruction era. The phenomenon began in the late 1860s during Reconstruction era ...

s.

The Tougaloo Nine

Following the ''

Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

'' decision effort was made to

desegregate

Desegregation is the process of ending the separation of two groups, usually referring to races. Desegregation is typically measured by the index of dissimilarity, allowing researchers to determine whether desegregation efforts are having impact o ...

public libraries along with other facilities. A primary example of those who worked to achieve such is The Tougaloo Nine. The Tougaloo Nine were a group of African-American college students (including Joseph Jackson Jr., Albert Lassiter, Alfred Cook, Ethel Sawyer, Geraldine Edwards, Evelyn Pierce, Janice Jackson, James Bradford, and Meredith Anding Jr.) who courageously sought to end segregation of the

Jackson

Jackson may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Jackson (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the surname or given name

Places

Australia

* Jackson, Queensland, a town in the Maranoa Region

* Jackson North, Qu ...

,

Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

Public Library in 1961. One day they simply asked for a philosophy book from the circulation desk at the "whites only" branch, but they were denied and asked to leave. They chose to stay despite harassment and were arrested. There were several similar incidents during the Civil Rights Movement, including the St. Helena Four who, on March 7, 1964, sought to enter the St. Helena branch of the Audubon Regional Library in

Greensburg,

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

. Peaceful protests by students in libraries expanded access during the Civil Rights Movement and beyond.

Wayne and Shirley A. Wiegand have written the history of the desegregation of public libraries in the

Jim Crow South

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

.

The NAACP

The Niagara Movement and the founding of the NAACP

At the turn of the 20th century,

Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

was regarded, particularly by the white community, as the foremost spokesman for African Americans in the US. Washington, who led the

Tuskegee Institute

Tuskegee University (Tuskegee or TU), formerly known as the Tuskegee Institute, is a private, historically black land-grant university in Tuskegee, Alabama. It was founded on Independence Day in 1881 by the state legislature.

The campus was de ...

, preached a message of self-reliance. He urged blacks to concentrate on improving their economic position rather than demanding social equality until they had proved that they "deserved" it. Publicly, he accepted the continuation of

Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

and segregation in the short term, but privately helped to fund national court cases that challenged the laws.

W. E. B. Du Bois and others in the black community rejected Washington's apology for segregation. One of his close associates,

William Monroe Trotter

William Monroe Trotter, sometimes just Monroe Trotter (April 7, 1872 – April 7, 1934), was a newspaper editor and real estate businessman based in Boston, Massachusetts. An activist for African-American civil rights, he was an early opponent of ...

, was arrested after challenging Washington when he came to deliver a speech in

Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

in 1905. Later that year Du Bois and Trotter convened a meeting of black activists on the Canadian side of

Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls () is a group of three waterfalls at the southern end of Niagara Gorge, spanning the border between the province of Ontario in Canada and the state of New York in the United States. The largest of the three is Horseshoe Falls, ...

. They issued a manifesto calling for universal manhood suffrage, elimination of all forms of racial segregation and extension of education—not limited to the

vocational education

Vocational education is education that prepares people to work as a technician or to take up employment in a skilled craft or trade as a tradesperson or artisan. Vocational Education can also be seen as that type of education given to an ind ...

that Washington emphasized—on a nondiscriminatory basis. The

Niagara Movement

The Niagara Movement (NM) was a black civil rights organization founded in 1905 by a group of activists—many of whom were among the vanguard of African-American lawyers in the United States—led by W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter. ...

was actively opposed by Washington, and had effectively collapsed due to internal divisions by 1908.

Du Bois joined with other black leaders and white activists, such as

Mary White Ovington

Mary White Ovington (April 11, 1865 – July 15, 1951) was an American suffragist, journalist, and co-founder of the NAACP, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Biography

Mary White Ovington was born April 11, 1865, ...

,

Oswald Garrison Villard

Oswald Garrison Villard (March 13, 1872 – October 1, 1949) was an American journalist and editor of the ''New York Evening Post.'' He was a civil rights activist, and along with his mother, Fanny Villard, a founding member of the NAACP. I ...

,

William English Walling

William English Walling (1877–1936) (known as "English" to friends and family) was an American labor reformer and Socialist Republican born into a wealthy family in Louisville, Kentucky. He founded the National Women's Trade Union League in 1903 ...

,

Henry Moskowitz, Julius Rosenthal,

Lillian Wald

Lillian D. Wald (March 10, 1867 – September 1, 1940) was an American nurse, humanitarian and author. She was known for contributions to human rights and was the founder of American community nursing. She founded the Henry Street Settlement in N ...

, Rabbi

Emil G. Hirsch

Emil Gustav Hirsch (May 22, 1851 – January 7, 1923) was a Luxembourgish-born Jewish American biblical scholar, Reform rabbi, contributing editor to numerous articles of ''The Jewish Encyclopedia'' (1906), anfounding member of the NAACP

Biog ...

, and

Stephen Wise to create the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. ...

(NAACP) in 1909. Du Bois also became editor of its magazine ''

The Crisis

''The Crisis'' is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Mi ...

''. In its early years, the NAACP concentrated on using the courts to attack Jim Crow laws and disfranchising constitutional provisions. It successfully challenged the

Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

ordinance that required

residential segregation

Residential segregation in the United States is the physical separation of two or more groups into different neighborhoods—a form of segregation that "sorts population groups into various neighborhood contexts and shapes the living environment a ...

in ''

Buchanan v. Warley

''Buchanan v. Warley'', 245 U.S. 60 (1917), is a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States addressed civil government-instituted racial segregation in residential areas. The Court held unanimously that a Louisville, Kentucky city ordin ...

'', . It also gained a Supreme Court ruling striking down Oklahoma's ''

grandfather clause

A grandfather clause, also known as grandfather policy, grandfathering, or grandfathered in, is a provision in which an old rule continues to apply to some existing situations while a new rule will apply to all future cases. Those exempt from t ...

'' that exempted most illiterate white voters from a law that disfranchised African-American citizens in ''

Guinn v. United States'' (1915).

Segregation in the federal civil service began under President Theodore Roosevelt, and continued under President Taft. President Wilson allowed his cabinet to escalate the process, ignoring complaints by the NAACP. The NAACP lobbied for commissioning of African Americans as officers in World War I. It was arranged for Du Bois to receive an Army commission, but he failed his physical. In 1915 the NAACP organized public education and protests in cities across the nation against

D.W. Griffith

David Wark Griffith (January 22, 1875 – July 23, 1948) was an American film director. Considered one of the most influential figures in the history of the motion picture, he pioneered many aspects of film editing and expanded the art of the na ...

's film ''

Birth of a Nation'', a film that glamorized the Ku Klux Klan. Boston and a few other cities refused to allow the film to open.

Anti-lynching activities

The

NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

operated primarily at the local level, providing as forum that brought black religious, professional and business elites in most large cities.

Baltimore