In

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, Christology (from the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc,

-λογία,

-logia

''-logy'' is a suffix in the English language, used with words originally adapted from Ancient Greek ending in ('). The earliest English examples were anglicizations of the French '' -logie'', which was in turn inherited from the Latin '' -logi ...

, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of

theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

that concerns

Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

. Different denominations have different opinions on questions like whether Jesus was human, divine, or both, and as a

messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

what his role would be in the freeing of the

Jewish people

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

from foreign rulers or in the prophesied

Kingdom of God

The concept of the kingship of God appears in all Abrahamic religions, where in some cases the terms Kingdom of God and Kingdom of Heaven are also used. The notion of God's kingship goes back to the Hebrew Bible, which refers to "his kingdom" b ...

, and in the

salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

from what would otherwise be the consequences of

sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

.

The earliest Christian writings gave several titles to Jesus, such as

Son of Man,

Son of God,

Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

, and , which were all derived from Hebrew scripture.

These terms centered around two opposing themes, namely "Jesus as a

preexistent figure who

becomes human and then

returns to God", versus

adoptionism

Adoptionism, also called dynamic monarchianism, is an Early Christianity, early Christian Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Diversity in early Christian theology, theological doctrine, which holds that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus was adopted as ...

– that Jesus was human who was "adopted" by God at his baptism, crucifixion, or resurrection.

From the second to the fifth centuries, the relation of the human and divine nature of Christ was a major focus of debates in the

early church

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish ...

and at the

first seven ecumenical councils. The

Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bith ...

in 451 issued a formulation of the

hypostatic union

''Hypostatic union'' (from the Greek: ''hypóstasis'', "sediment, foundation, substance, subsistence") is a technical term in Christian theology employed in mainstream Christology to describe the union of Christ's humanity and divinity in one h ...

of the two natures of Christ, one human and one divine, "united with neither confusion nor division". Most of the major branches of Western Christianity and

Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first m ...

subscribe to this formulation,

while many branches of

Oriental Orthodox Churches

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 60 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are part of the Nicene Christian tradition, and represent ...

reject it, subscribing to

miaphysitism

Miaphysitism is the Christological doctrine that holds Jesus, the "Incarnate Word, is fully divine and fully human, in one 'nature' (''physis'')." It is a position held by the Oriental Orthodox Churches and differs from the Chalcedonian positio ...

.

Definition and approaches

''Christology'' (from the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc,

-λογία,

-logia

''-logy'' is a suffix in the English language, used with words originally adapted from Ancient Greek ending in ('). The earliest English examples were anglicizations of the French '' -logie'', which was in turn inherited from the Latin '' -logi ...

, label=none), literally "the understanding of Christ", is the study of the nature (person) and work (role in salvation) of

Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

.

[Matt Stefon, Hans J. Hillerbrand]

''Christology''

Encyclopedia Britannica[Catholic encyclopedia]

/ref> It studies Jesus Christ's humanity and divinity, and the relation between these two aspects; and the role he plays in salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

.

"Ontological

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

Christology" analyzes the nature or being[thinkapologetics.com, http://thinkapologetics.blogspot.com/2009/05/jesus-functional-or-ontological.html?m=1 ''Jesus- A Functional or Ontological Christology?'']] of Jesus Christ. "Functional Christology" analyzes the works of Jesus Christ, while " Christian soteriology, soteriological Christology" analyzes the "salvific

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its ...

" standpoints of Christology.

Several approaches can be distinguished within Christology. The term "Christology from above" or "high Christology" refers to approaches that include aspects of divinity, such as Lord and Son of God, and the idea of the pre-existence of Christ

The pre-existence of Christ asserts the existence of Christ before his incarnation as Jesus. One of the relevant Bible passages is where, in the Trinitarian interpretation, Christ is identified with a pre-existent divine hypostasis (substantive ...

as the ''Logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, wikt:λόγος, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive ...

'' (the Word), as expressed in the prologue to the Gospel of John. These approaches interpret the works of Christ in terms of his divinity. According to Pannenberg, Christology from above "was far more common in the ancient Church, beginning with Ignatius of Antioch

Ignatius of Antioch (; Greek: Ἰγνάτιος Ἀντιοχείας, ''Ignátios Antiokheías''; died c. 108/140 AD), also known as Ignatius Theophorus (, ''Ignátios ho Theophóros'', lit. "the God-bearing"), was an early Christian writer ...

and the second century Apologists." The term "Christology from below" or "low Christology" refers to approaches that begin with the human aspects and the ministry of Jesus (including the miracles, parables, etc.) and move towards his divinity and the mystery of incarnation.

Person of Christ

A basic christological teaching is that the person of

A basic christological teaching is that the person of Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

is both human and divine. The human and divine natures of Jesus Christ apparently ('' prosopic'') form a duality, as they coexist within one person ('' hypostasis'').[''Introducing Christian Doctrine'' by Millard J. Erickson, L. Arnold Hustad 2001 ISBN p. 234] There are no direct discussions in the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

regarding the dual nature of the Person of Christ as both divine and human,Monophysitism

Monophysitism ( or ) or monophysism () is a Christological term derived from the Greek (, "alone, solitary") and (, a word that has many meanings but in this context means "nature"). It is defined as "a doctrine that in the person of the incarn ...

(Monophysite controversy, 3rd–8th centuries): After the union of the divine and the human in the historical incarnation, Jesus Christ had only a single nature. Monophysitism was condemned as heretical by the Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bith ...

(451).

* Miaphysitism

Miaphysitism is the Christological doctrine that holds Jesus, the "Incarnate Word, is fully divine and fully human, in one 'nature' (''physis'')." It is a position held by the Oriental Orthodox Churches and differs from the Chalcedonian positio ...

(Oriental Orthodox

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 60 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are part of the Nicene Christian tradition, and represent o ...

churches): In the person of Jesus Christ, divine nature and human nature are united in a compound nature ("physis").

* Dyophysitism

In Christian theology, dyophysitism (Greek: δυοφυσιτισμός, from δυο (''dyo''), meaning "two" and φύσις (''physis''), meaning "nature") is the Christological position that two natures, divine and human, exist in the person of ...

(Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

, Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

, Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

, and the Reformed Church

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

es): Christ maintained two natures, one divine and one human, after the Incarnation; articulated by the Chalcedonian Definition

The Chalcedonian Definition (also called the Chalcedonian Creed or the Definition of Chalcedon) is a declaration of Christ's nature (that it is dyophysite), adopted at the Council of Chalcedon in AD 451. Chalcedon was an early centre of Chris ...

.

* Monarchianism

Monarchianism is a Christian theology that emphasizes God as one indivisible being,

at Catholic Encyclopedia, newadvent.org (including Adoptionism

Adoptionism, also called dynamic monarchianism, is an Early Christianity, early Christian Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Diversity in early Christian theology, theological doctrine, which holds that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus was adopted as ...

and Modalism

Modalistic Monarchianism, also known as Modalism or Oneness Christology, is a Christian theology upholding the oneness of God as well as the divinity of Jesus; as a form of Monarchianism, it stands in contrast with Trinitarianism. Modalistic Monar ...

): God as one, in contrast to the doctrine of the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the F ...

. Condemned as heretical in the Patristic era

Patristics or patrology is the study of the early Christian writers who are designated Church Fathers. The names derive from the combined forms of Latin ''pater'' and Greek ''patḗr'' (father). The period is generally considered to run from ...

but followed today by certain groups of Nontrinitarians

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the mainstream Christian doctrine of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essence ...

.

Influential Christologies which were broadly condemned as heretical are:

* Docetism

In the history of Christianity, docetism (from the grc-koi, δοκεῖν/δόκησις ''dokeĩn'' "to seem", ''dókēsis'' "apparition, phantom") is the heterodox doctrine that the phenomenon of Jesus, his historical and bodily existence, an ...

(3rd–4th centuries) claimed the human form of Jesus was mere semblance without any true reality.

* Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

(4th century) viewed the divine nature of Jesus, the Son of God, as distinct and inferior to God the Father

God the Father is a title given to God in Christianity. In mainstream trinitarian Christianity, God the Father is regarded as the first person of the Trinity, followed by the second person, God the Son Jesus Christ, and the third person, God t ...

, e.g., by having a beginning in time.

* Nestorianism

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

(5th century) considered the two natures (human and divine) of Jesus Christ almost entirely distinct.

* Monothelitism

Monothelitism, or monotheletism (from el, μονοθελητισμός, monothelētismós, doctrine of one will), is a theological doctrine in Christianity, that holds Christ as having only one will. The doctrine is thus contrary to dyotheliti ...

(7th century), considered Christ to have only one will.

Various church councils

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

, mainly in the 4th and 5th centuries, resolved most of these controversies, making the doctrine of the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the F ...

orthodox in nearly all branches of Christianity. Among them, only the Dyophysite doctrine was recognized as true and not heretical, belonging to the Christian orthodoxy

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churc ...

and deposit of faith

The deposit of faith ( or ''fidei depositum'') is the body of revealed truth in the scriptures and sacred tradition proposed by the Roman Catholic Church for the belief of the faithful. The phrase has a similar use in the US Episcopal Church.

Ca ...

.

Salvation

In Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology of Christianity, Christian belief and practice. Such study concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Christian tradition. Christian theology, theologian ...

, atonement

Atonement (also atoning, to atone) is the concept of a person taking action to correct previous wrongdoing on their part, either through direct action to undo the consequences of that act, equivalent action to do good for others, or some other ex ...

is the method by which human beings can be reconciled to God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

through Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, names and titles), was ...

's sacrificial suffering and death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

. Atonement is the forgiving or pardoning of sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

in general and original sin

Original sin is the Christian doctrine that holds that humans, through the fact of birth, inherit a tainted nature in need of regeneration and a proclivity to sinful conduct. The biblical basis for the belief is generally found in Genesis 3 (t ...

in particular through the suffering, death and resurrection of Jesus

The resurrection of Jesus ( grc-x-biblical, ἀνάστασις τοῦ Ἰησοῦ) is the Christian belief that God raised Jesus on the third day after his crucifixion, starting – or restoring – his exalted life as Christ and Lo ...

,[Collins English Dictionary, Complete & Unabridged 11th Edition]

''atonement''

retrieved 3 October 2012: "2. (often capital) ''Christian theol''

a. the reconciliation of man with God through the life, sufferings, and sacrificial death of Christ

b. the sufferings and death of Christ" enabling the reconciliation

Reconciliation or reconcile may refer to:

Accounting

* Reconciliation (accounting)

Arts, entertainment, and media Sculpture

* ''Reconciliation'' (Josefina de Vasconcellos sculpture), a sculpture by Josefina de Vasconcellos in Coventry Cathedra ...

between God and his creation. Due to the influence of Gustaf Aulèn's (1879–1978) ''Christus Victor'' (1931), the various theories or paradigmata of atonement are often grouped as "classical paradigm", "objective paradigm", and the "subjective paradigm":Gustaf Aulen

Gustav, Gustaf or Gustave may refer to:

* Gustav (name), a male given name of Old Swedish origin

Art, entertainment, and media

* ''Primeval'' (film), a 2007 American horror film

* ''Gustav'' (film series), a Hungarian series of animated short car ...

, Christus Victor: An Historical Study of the Three Main Types of the Idea of Atonement, E.T. London: SPCK; New York: Macmillan,1931Ransom theory of atonement

The ransom theory of atonement was a theory in Christian theology as to how the process of Atonement in Christianity had happened. It therefore accounted for the meaning and effect of the death of Jesus Christ. It was one of a number of historic ...

, which teaches that the death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

of Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, names and titles), was ...

was a ransom

Ransom is the practice of holding a prisoner or item to extort money or property to secure their release, or the sum of money involved in such a practice.

When ransom means "payment", the word comes via Old French ''rançon'' from Latin ''red ...

sacrifice

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exi ...

, usually said to have been paid to Satan

Satan,, ; grc, ὁ σατανᾶς or , ; ar, شيطانالخَنَّاس , also known as Devil in Christianity, the Devil, and sometimes also called Lucifer in Christianity, is an non-physical entity, entity in the Abrahamic religions ...

or to death itself, in some views paid to God the Father

God the Father is a title given to God in Christianity. In mainstream trinitarian Christianity, God the Father is regarded as the first person of the Trinity, followed by the second person, God the Son Jesus Christ, and the third person, God t ...

, in satisfaction for the bondage and debt on the souls of humanity as a result of inherited sin. Gustaf Aulén reinterpreted the ransom theory, calling it the Christus Victor

''Christus Victor'' is a book by Gustaf Aulén published in English in 1931, presenting a study of Atonement in Christianity, theories of atonement in Christianity. The original Swedish title is ''Den kristna försoningstanken'' ("The Christian ...

doctrine, arguing that Christ's death was not a payment to the Devil, but defeated the powers of evil

Evil, in a general sense, is defined as the opposite or absence of good. It can be an extremely broad concept, although in everyday usage it is often more narrowly used to talk about profound wickedness and against common good. It is general ...

, which had held humankind in their dominion.;

** Recapitulation theory

The theory of recapitulation, also called the biogenetic law or embryological parallelism—often expressed using Ernst Haeckel's phrase "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny"—is a historical hypothesis that the development of the embryo of an ani ...

, which says that Christ succeeded where Adam

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as " ...

failed. Theosis ("divinization") is a "corollary" of the recapitulation.

* Objective paradigm:

** Satisfaction theory of atonement

The satisfaction theory of atonement is a theory in Catholic theology which holds that Jesus Christ redeemed humanity through making satisfaction for humankind's disobedience through his own supererogatory obedience. The theory draws primarily ...

, developed by Anselm of Canterbury

Anselm of Canterbury, OSB (; 1033/4–1109), also called ( it, Anselmo d'Aosta, link=no) after his birthplace and (french: Anselme du Bec, link=no) after his monastery, was an Italian Benedictine monk, abbot, philosopher and theologian of th ...

(1033/4–1109), which teaches that Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

suffered crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagin ...

as a substitute for human sin

In a religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, s ...

, satisfying God's just wrath against humankind's transgression due to Christ's infinite merit.

** Penal substitution

Penal substitution (sometimes, esp. in older writings, called forensic theory)D. Smith, The atonement in the light of history and the modern spirit' (London: Hodder and Stoughton), p. 96-7: 'THE FORENSIC THEORY...each successive period of history ...

, also called "forensic theory" and "vicarious punishment", which was a development by the Reformers of Anselm's satisfaction theory. Instead of considering sin as an affront to God's honour, it sees sin as the breaking of God's moral law. Penal substitution sees sinful man as being subject to God's wrath, with the essence of Jesus' saving work being his substitution in the sinner's place, bearing the curse in the place of man.

** Governmental theory of atonement

The governmental theory of the atonement (also known as the rectoral theory, or the moral government theory) is a doctrine in Christian theology concerning the meaning and effect of the death of Jesus Christ. It teaches that Christ suffered for hum ...

, "which views God as both the loving creator and moral Governor of the universe."

* Subjective paradigm:

**Moral influence theory of atonement

The moral influence or moral example theory of atonement, developed or most notably propagated by Abelard (1079–1142), is an alternative to Anselm's satisfaction theory of atonement. Abelard focused on changing man's perception of God as not ...

, developed, or most notably propagated, by Abelard

Peter Abelard (; french: link=no, Pierre Abélard; la, Petrus Abaelardus or ''Abailardus''; 21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, poet, composer and musician. This source has a detailed desc ...

(1079–1142), who argued that "Jesus died as the demonstration of God's love", a demonstration which can change the hearts and minds of the sinners, turning back to God.

** Moral example theory

Socinianism () is a nontrinitarian belief system deemed heretical by the Catholic Church and other Christian traditions. Named after the Italian theologians Lelio Sozzini (Latin: Laelius Socinus) and Fausto Sozzini (Latin: Faustus Socinus), uncle ...

, developed by Faustus Socinus

Fausto Paolo Sozzini, also known as Faustus Socinus ( pl, Faust Socyn; 5 December 1539 – 4 March 1604), was an Italian theologian and, alongside his uncle Lelio Sozzini, founder of the Non-trinitarian Christian belief system known as Sociniani ...

(1539–1604) in his work (1578), who rejected the idea of "vicarious satisfaction". According to Socinus, Jesus' death offers humanity a perfect example of self-sacrificial dedication to God.

Other theories are the "embracement theory" and the "shared atonement" theory.

Early Christologies (1st century)

Early notions of Christ

The earliest christological reflections were shaped by both the Jewish background of the earliest Christians, and by the Greek world of the eastern Mediterranean in which they operated.Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

, and ''Kyrios

''Kyrios'' or ''kurios'' ( grc, κύριος, kū́rios) is a Greek word which is usually translated as "lord" or "master". It is used in the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew scriptures about 7000 times, in particular translating the name ...

'', which were all derived from Hebrew scripture.Gospel of John

The Gospel of John ( grc, Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Ἰωάννην, translit=Euangélion katà Iōánnēn) is the fourth of the four canonical gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "sig ...

), Jesus Christ is the eternal ''Logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, wikt:λόγος, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive ...

'' who already possesses unity with the Father before the act of Incarnation

Incarnation literally means ''embodied in flesh'' or ''taking on flesh''. It refers to the conception and the embodiment of a deity or spirit in some earthly form or the appearance of a god as a human. If capitalized, it is the union of divinit ...

.[Charles T. Waldrop (1985). ''Karl Barth's christology'' pp. 19–23] In contrast, the Antiochian school

The Catechetical School of Antioch was one of the two major centers of the study of biblical exegesis and theology during Late Antiquity; the other was the Catechetical School of Alexandria. This group was known by this name because the advocates ...

viewed Christ as a single, unified human person apart from his relationship to the divine.

Pre-existence

The notion of pre-existence is deeply rooted in Jewish thought, and can be found in apocalyptic thought and among the rabbis of Paul's time, but Paul was most influenced by Jewish-Hellenistic wisdom literature, where Wisdom' is extolled as something existing before the world and already working in creation. According to Witherington, Paul "subscribed to the christological notion that Christ existed prior to taking on human flesh founding the story of Christ ..on the story of divine Wisdom".

''Kyrios''

The title ''Kyrios

''Kyrios'' or ''kurios'' ( grc, κύριος, kū́rios) is a Greek word which is usually translated as "lord" or "master". It is used in the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew scriptures about 7000 times, in particular translating the name ...

'' for Jesus is central to the development of New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

Christology.Septuagint

The Greek Old Testament, or Septuagint (, ; from the la, septuaginta, lit=seventy; often abbreviated ''70''; in Roman numerals, LXX), is the earliest extant Greek translation of books from the Hebrew Bible. It includes several books beyond th ...

it translates the Tetragrammaton

The Tetragrammaton (; ), or Tetragram, is the four-letter Hebrew language, Hebrew theonym (transliterated as YHWH), the name of God in the Hebrew Bible. The four letters, written and read from right to left (in Hebrew), are ''yodh'', ''he (l ...

, the holy Name of God. As such, it closely links Jesus with God – in the same way a verse such as Matthew

Matthew may refer to:

* Matthew (given name)

* Matthew (surname)

* ''Matthew'' (ship), the replica of the ship sailed by John Cabot in 1497

* ''Matthew'' (album), a 2000 album by rapper Kool Keith

* Matthew (elm cultivar), a cultivar of the Ch ...

28:19, "The Name (singular) of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit".

''Kyrios'' is also conjectured to be the Greek translation of Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated in ...

, which in everyday Aramaic usage was a very respectful form of polite address, which means more than just "teacher" and was somewhat similar to rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

. While the term expressed the relationship between Jesus and his disciples during his life, the Greek ''Kyrios'' came to represent his lordship over the world.[Oscar Cullmann (1959)]

''The Christology of the New Testament''

p. 202

The early Christians

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish d ...

placed ''Kyrios'' at the center of their understanding, and from that center attempted to understand the other issues related to the Christian mysteries.[Mini S. Johnson (2005)]

''Christology: Biblical and Historical''

pp. 229–235 The question of the deity of Christ in the New Testament is inherently related to the ''Kyrios'' title of Jesus used in the early Christian writings and its implications for the absolute lordship of Jesus. In early Christian belief, the concept of ''Kyrios'' included the pre-existence of Christ

The pre-existence of Christ asserts the existence of Christ before his incarnation as Jesus. One of the relevant Bible passages is where, in the Trinitarian interpretation, Christ is identified with a pre-existent divine hypostasis (substantive ...

, for they believed if Christ is one with God, he must have been united with God from the very beginning.[Oscar Cullmann (1959).]

''The Christology of the New Testament''

pp. 234–237

Development of "low Christology" and "high Christology"

Two fundamentally different Christologies developed in the early Church, namely a "low" or adoptionist

Adoptionism, also called dynamic monarchianism, is an early Christian nontrinitarian theological doctrine, which holds that Jesus was adopted as the Son of God at his baptism, his resurrection, or his ascension. How common adoptionist views ...

Christology, and a "high" or "incarnation" Christology. The chronology of the development of these early Christologies is a matter of debate within contemporary scholarship.[Bart Ehrman, ''How Jesus became God'', Course Guide] as witnessed in the Gospels, with the earliest Christians believing that Jesus was a human who was exalted, or else adopted as God's Son, when he was resurrected.Wilhelm Bousset

Wilhelm Bousset (3 September 1865, Lübeck – 8 March 1920, Gießen) was a German theologian and New Testament scholar. He was of Huguenot ancestry and a native of Lübeck. His most influential work was ''Kyrios Christos'', an attempt to explain ...

's influential ''Kyrios Christos'' (1913). This evolutionary model was very influential, and the "low Christology" has long been regarded as the oldest Christology.[

The other early Christology is "high Christology", which is "the view that Jesus was a pre-existent divine being who became a human, did the Father's will on earth, and then was taken back up into heaven whence he had originally come",][ and from where he appeared on earth. According to Bousset, this "high Christology" developed at the time of Paul's writing, under the influence of Gentile Christians, who brought their pagan Hellenistic traditions to the early Christian communities, introducing divine honours to Jesus. According to Casey and Dunn, this "high Christology" developed after the time of Paul, at the end of the first century CE when the Gospel of John was written.

Since the 1970s, these late datings for the development of a "high Christology" have been contested, and a majority of scholars argue that this "high Christology" existed already before the writings of Paul. According to the "New ",][Larry Hurtado (10 July 2015)]

''"Early High Christology": A "Paradigm Shift"? "New Perspective"?''

/ref> "Early High Christology Club",Martin Hengel

Martin Hengel (14 December 1926 – 2 July 2009) was a German historian of religion, focusing on the " Second Temple Period" or "Hellenistic Period" of early Judaism and Christianity.

Biography

Hengel was born in Reutlingen, south of Stuttgart ...

, Larry Hurtado

Larry Weir Hurtado, (December 29, 1943 – November 25, 2019), was an American New Testament scholar, historian of early Christianity, and Emeritus Professor of New Testament Language, Literature, and Theology at the University of Edinburgh ( ...

, N. T. Wright

Nicholas Thomas Wright (born 1 December 1948), known as N. T. Wright or Tom Wright, is an English New Testament scholar, Pauline theologian and Anglican bishop. He was the bishop of Durham from 2003 to 2010. He then became research profe ...

, and Richard Bauckham

Richard John Bauckham (born 22 September 1946) is an English Anglican scholar in theology, historical theology and New Testament studies, specialising in New Testament Christology and the Gospel of John. He is a senior scholar at Ridley Hall, C ...

,[ Some 'Early High Christology' proponents scholars argue that this "high Christology" may go back to Jesus himself.][Larry Hurtado]

"The Origin of 'Divine Christology'?"

/ref>

There is a controversy regarding whether Jesus himself claimed to be divine. In ''Honest to God

''Honest to God'' is a book written by the Anglican Bishop of Woolwich John A.T. Robinson, criticising traditional Christian theology. It aroused a storm of controversy on its original publication by SCM Press in 1963.

Robinson's own evaluati ...

'', then-Bishop of Woolwich

The Bishop of Woolwich is an episcopal title used by an area bishop of the Church of England Diocese of Southwark, in the Province of Canterbury, England.

The title takes its name after Woolwich, a suburb of the Royal Borough of Greenwich. Two o ...

, John A. T. Robinson

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second ...

, questioned the idea. John Hick

John Harwood Hick (20 January 1922 – 9 February 2012) was a philosopher of religion and theologian born in England who taught in the United States for the larger part of his career. In philosophical theology, he made contributions in the are ...

, writing in 1993, mentioned changes in New Testament studies, citing "broad agreement" that scholars do not today support the view that Jesus claimed to be God, quoting as examples Michael Ramsey

Arthur Michael Ramsey, Baron Ramsey of Canterbury, (14 November 1904 – 23 April 1988) was an English Anglican bishop and life peer. He served as the 100th Archbishop of Canterbury. He was appointed on 31 May 1961 and held the office until 1 ...

(1980), C. F. D. Moule

Charles Francis Digby "Charlie" Moule (; 3 December 1908 – 30 September 2007), known professionally as C. F. D. Moule, was an English Anglican priest and theologian. He was a leading scholar of the New Testament and was Lady Marg ...

(1977), James Dunn (1980), Brian Hebblethwaite (1985) and David Brown (1985). Larry Hurtado

Larry Weir Hurtado, (December 29, 1943 – November 25, 2019), was an American New Testament scholar, historian of early Christianity, and Emeritus Professor of New Testament Language, Literature, and Theology at the University of Edinburgh ( ...

, who argues that the followers of Jesus within a very short period developed an exceedingly high level of devotional reverence to Jesus, at the same time rejects the view that Jesus made a claim to messiahship or divinity to his disciples during his life as "naive and ahistorical". According to Gerd Lüdemann

Gerd Lüdemann (July 5, 1946–May 23, 2021) was a German biblical scholar and historian. He taught first Jewish Christianity and Gnosticism at McMaster University, Canada (1977–1979) and then New Testament at Vanderbilt Divinity School, U.S. ...

, the broad consensus among modern New Testament scholars is that the proclamation of the divinity of Jesus was a development within the earliest Christian communities.Gerd Lüdemann

Gerd Lüdemann (July 5, 1946–May 23, 2021) was a German biblical scholar and historian. He taught first Jewish Christianity and Gnosticism at McMaster University, Canada (1977–1979) and then New Testament at Vanderbilt Divinity School, U.S. ...

"An Embarrassing Misrepresentation"

''Free Inquiry'', October / November 2007: "the broad consensus of modern New Testament scholars that the proclamation of Jesus's exalted nature was in large measure the creation of the earliest Christian communities."N. T. Wright

Nicholas Thomas Wright (born 1 December 1948), known as N. T. Wright or Tom Wright, is an English New Testament scholar, Pauline theologian and Anglican bishop. He was the bishop of Durham from 2003 to 2010. He then became research profe ...

points out that arguments over the claims of Jesus regarding divinity have been passed over by more recent scholarship, which sees a more complex understanding of the idea of God in first century Judaism.

New Testament writings

The study of the various Christologies of the Apostolic Age is based on early Christian documents.

Paul

The oldest Christian sources are the writings of Paul the Apostle, Paul. The central Christology of Paul conveys the notion of Christ's pre-existence and the identification of Christ as ''Kyrios (Biblical term), Kyrios''. Both notions already existed before him in the early Christian communities, and Paul deepened them and used them for preaching in the Hellenistic communities.

What exactly Paul believed about the nature of Jesus cannot be determined decisively. In Philippians 2, Paul states that Jesus was preexistent and came to Earth "by taking the form of a servant, being made in human likeness". This sounds like an Incarnation (Christianity), incarnation Christology. In Romans 1:4, however, Paul states that Jesus "was declared with power to be the Son of God by his resurrection from the dead", which sounds like an Adoptionism, adoptionistic Christology, where Jesus was a human being who was "adopted" after his death. Different views would be debated for centuries by Christians and finally settled on the idea that he was both fully human and fully divine by the middle of the 5th century in the Council of Ephesus. Paul's thoughts on Jesus' teachings, versus his nature and being, is more defined, in that Paul believed Jesus was sent as an

The oldest Christian sources are the writings of Paul the Apostle, Paul. The central Christology of Paul conveys the notion of Christ's pre-existence and the identification of Christ as ''Kyrios (Biblical term), Kyrios''. Both notions already existed before him in the early Christian communities, and Paul deepened them and used them for preaching in the Hellenistic communities.

What exactly Paul believed about the nature of Jesus cannot be determined decisively. In Philippians 2, Paul states that Jesus was preexistent and came to Earth "by taking the form of a servant, being made in human likeness". This sounds like an Incarnation (Christianity), incarnation Christology. In Romans 1:4, however, Paul states that Jesus "was declared with power to be the Son of God by his resurrection from the dead", which sounds like an Adoptionism, adoptionistic Christology, where Jesus was a human being who was "adopted" after his death. Different views would be debated for centuries by Christians and finally settled on the idea that he was both fully human and fully divine by the middle of the 5th century in the Council of Ephesus. Paul's thoughts on Jesus' teachings, versus his nature and being, is more defined, in that Paul believed Jesus was sent as an atonement

Atonement (also atoning, to atone) is the concept of a person taking action to correct previous wrongdoing on their part, either through direct action to undo the consequences of that act, equivalent action to do good for others, or some other ex ...

for the sins of everyone.

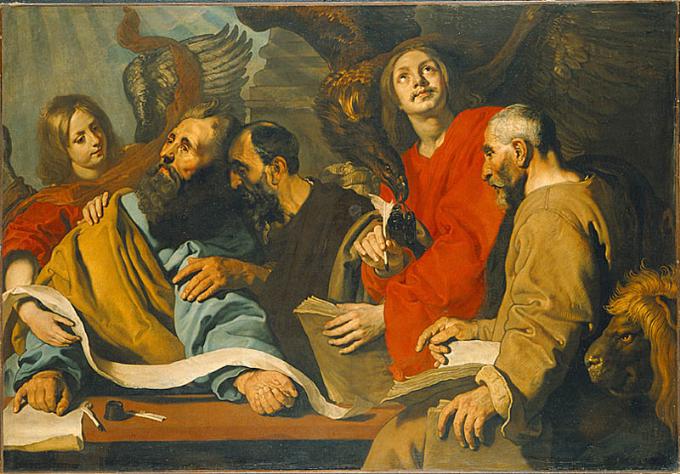

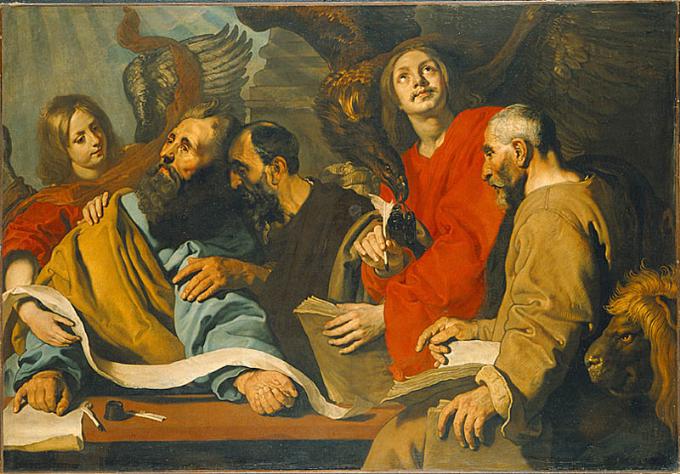

The Gospels

The synoptic Gospels date from after the writings of Paul. They provide episodes from the life of Jesus and some of his works, but the authors of the New Testament show little interest in an absolute chronology of Jesus or in synchronizing the episodes of his life,

The synoptic Gospels date from after the writings of Paul. They provide episodes from the life of Jesus and some of his works, but the authors of the New Testament show little interest in an absolute chronology of Jesus or in synchronizing the episodes of his life,[Karl Rahner (2004). ''Encyclopedia of theology: a concise Sacramentum mundi'' p. 731] and as in wikisource:Bible (American Standard)/John#21:25, John 21:25, the Gospels do not claim to be an exhaustive list of his works.

Christologies that can be gleaned from the three Synoptic Gospels generally emphasize the humanity of Jesus, his sayings, his Parables of Jesus, parables, and his Miracles of Jesus, miracles. The Gospel of John

The Gospel of John ( grc, Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Ἰωάννην, translit=Euangélion katà Iōánnēn) is the fourth of the four canonical gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "sig ...

provides a different perspective that focuses on his divinity.Logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, wikt:λόγος, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive ...

'', usually translated as "Word", along with his pre-existence, and they emphasize the cosmic significance of Christ, e.g.: "All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made." In the context of these verses, the Word made flesh is identical with the Word who was in the beginning with God, being exegetically equated with Jesus.

Controversies and ecumenical councils (2nd–8th century)

Post-Apostolic controversies

Following the Apostolic Age, from the second century onwards, a number of controversies developed about how the human and divine are related within the person of Jesus. As of the second century, a number of different and opposing approaches developed among various groups. In contrast to prevailing monoprosopic views on the Person of Christ, alternative dyoprosopic notions were also promoted by some theologians, but such views were rejected by the ecumenical councils. For example, Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

did not endorse divinity, Ebionism argued Jesus was an ordinary mortal, while Gnosticism held docetism, docetic views which argued Christ was a spiritual being who only appeared to have a physical body. The resulting tensions led to schism (religion), schisms within the church in the second and third centuries, and ecumenical councils were convened in the fourth and fifth centuries to deal with the issues.

Although some of the debates may seem to various modern students to be over a theological iota, they took place in controversial political circumstances, reflecting the relations of temporal powers and divine authority, and certainly resulted in schisms, among others that separated the Church of the East from the Church of the Roman Empire.

First Council of Nicaea (325) and First Council of Constantinople (381)

In 325, the First Council of Nicaea defined the persons of the Godhead (Christianity), Godhead and their relationship with one another, decisions which were ratified at the First Council of Constantinople in 381. The language used was that the one God exists in three persons (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit); in particular, it was affirmed that the Son was ''homoousios'' (of the same being) as the Father. The Nicene Creed declared the full divinity and full humanity of Jesus. After the First Council of Nicaea in 325 the ''Logos'' and the second Person of the Holy Trinity, Trinity were being used interchangeably.

First Council of Ephesus (431)

In 431, the First Council of Ephesus was initially called to address the views of Nestorius on Mariology, but the problems soon extended to Christology, and schisms followed. The 431 council was called because in defense of his loyal priest Anastasius, Nestorius had denied the ''Theotokos'' title for Virgin Mary, Mary and later contradicted Proclus during a sermon in Constantinople. Pope Celestine I (who was already upset with Nestorius due to other matters) wrote about this to Cyril of Alexandria, who orchestrated the council. During the council, Nestorius defended his position by arguing there must be two persons of Christ, one human, the other divine, and Mary had given birth only to a human, hence could not be called the ''Theotokos'', i.e. "the one who gives birth to God". The debate about the single or dual nature of Christ ensued in Ephesus.

The First Council of Ephesus debated miaphysitism

Miaphysitism is the Christological doctrine that holds Jesus, the "Incarnate Word, is fully divine and fully human, in one 'nature' (''physis'')." It is a position held by the Oriental Orthodox Churches and differs from the Chalcedonian positio ...

(two natures united as one after the hypostatic union

''Hypostatic union'' (from the Greek: ''hypóstasis'', "sediment, foundation, substance, subsistence") is a technical term in Christian theology employed in mainstream Christology to describe the union of Christ's humanity and divinity in one h ...

) versus dyophysitism (coexisting natures after the hypostatic union) versus monophysitism (only one nature) versus Nestorianism

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

(two hypostases). From the Christological viewpoint, the council adopted ('but being made one', ) – Council of Ephesus, Epistle of Cyril to Nestorius, i.e. 'one nature of the Word of God incarnate' (, ). In 451, the Council of Chalcedon affirmed dyophysitism. The Oriental Orthodox

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 60 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are part of the Nicene Christian tradition, and represent o ...

rejected this and subsequent councils and continued to consider themselves as ''miaphysite'' according to the faith put forth at the Councils of First Council of Nicaea, Nicaea and Council of Ephesus, Ephesus.[''The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity'' by Ken Parry 2009 p. 8]

/ref> The council also confirmed the ''Theotokos'' title and excommunicated Nestorius.[''Fundamentals of Catholicism: God, Trinity, Creation, Christ, Mary'' by Kenneth Baker 1983 pp. 228–3]

/ref>[''Mary, Mother of God'' by Carl E. Braaten and Robert W. Jenson 2004 p. 84]

Council of Chalcedon (451)

The 451 Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bith ...

was highly influential, and marked a key turning point in the christological debates. It is the last council which many Lutherans, Anglicans and other Protestants consider ecumenical.hypostatic union

''Hypostatic union'' (from the Greek: ''hypóstasis'', "sediment, foundation, substance, subsistence") is a technical term in Christian theology employed in mainstream Christology to describe the union of Christ's humanity and divinity in one h ...

'', the proposition that Christ has one human nature ''(physis)'' and one divine nature ''(physis)'', each distinct and complete, and united with neither confusion nor division. Most of the major branches of Western Christianity (Roman Catholicism, Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

, Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

, and Calvinism, Reformed), Church of the East, Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first m ...

subscribe to the Chalcedonian Christological formulation, while many branches of Oriental Orthodox Churches

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 60 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are part of the Nicene Christian tradition, and represent ...

(Syriac Orthodox Church, Syrian Orthodoxy, Coptic Orthodoxy, Ethiopian Orthodoxy, and Armenian Apostolic Church, Armenian Apostolicism) reject it.

Although the Chalcedonian Creed did not put an end to all christological debate, it did clarify the terms used and became a point of reference for many future Christologies. But it also broke apart the church of the Eastern Roman Empire in the fifth century, and unquestionably established the primacy of Rome in the East over those who accepted the Council of Chalcedon. This was reaffirmed in 519, when the Eastern Chalcedonians accepted the Pope Hormisdas, Formula of Hormisdas, anathematizing all of their own Eastern Chalcedonian hierarchy, who died out of communion with Rome from 482 to 519.

Fifth-seventh Ecumenical Council (553, 681, 787)

The Second Council of Constantinople in 553 interpreted the decrees of Chalcedon, and further explained the relationship of the two natures of Jesus. It also condemned the alleged teachings of Origen on the pre-existence of the soul, and other topics.

9th–11th century

Eastern Christianity

Western medieval Christology

The term "monastic Christology" has been used to describe spiritual approaches developed by Anselm of Canterbury

Anselm of Canterbury, OSB (; 1033/4–1109), also called ( it, Anselmo d'Aosta, link=no) after his birthplace and (french: Anselme du Bec, link=no) after his monastery, was an Italian Benedictine monk, abbot, philosopher and theologian of th ...

, Peter Abelard and Bernard of Clairvaux. The Franciscan piety of the 12th and 13th centuries led to "popular Christology". Systematic approaches by theologians, such as Thomas Aquinas, are called "scholastic Christology".[''Christology: Biblical And Historical'' by Mini S. Johnson, 2005 pp. 74–7]

/ref>

In the Christianity in the 13th century, 13th century, Thomas Aquinas provided the first systematic Christology that consistently resolved a number of the existing issues.[''Christology: Biblical And Historical'' by Mini S. Johnson, 2005 pp. 76–7]

/ref>[''Aquinas as authority'' by Paul van Geest, Harm J. M. J. Goris pp. 25–3]

/ref>

The Middle Ages also witnessed the emergence of the "tender image of Jesus" as a friend and a living source of love and comfort, rather than just the ''Kyrios'' image.[''Christology: Key Readings in Christian Thought'' by Jeff Astley, David Brown, Ann Loades 2009 p. 106]

Reformation

John Calvin maintained there was no human element in the Person of Christ which could be separated from the Person of Logos (Christianity), The Word. Calvin also emphasized the importance of the "Work of Christ" in any attempt at understanding the Person of Christ and cautioned against ignoring the Works of Jesus during his ministry.

Modern developments

Liberal Protestant theology

The 19th century saw the rise of Liberal Protestant theology, which questioned the dogmatic foundations of Christianity, and approached the Bible with critical-historical tools.[Jaroslav Jan Pelikan]

''The debate over Christology in modern Christian thought''

/ref> The divinity of Jesus was problematized, and replaced with an emphasis on the ethical aspects of his teachings.

Roman Catholicism

Catholic theologian Karl Rahner sees the purpose of modern Christology as to formulate the Christian belief that "God became man and that God-made-man is the individual Jesus Christ" in a manner that this statement can be understood consistently, without the confusions of past debates and mythologies. Rahner pointed out the coincidence between the Person of Christ and the Word of God, referring to wikisource:Bible (American Standard)/Mark#8:38, Mark 8:38 and wikisource:Bible (American Standard)/Luke#9:26, Luke 9:26 which state whoever is ashamed of the words of Jesus is ashamed of the Lord himself.

Hans Urs von Balthasar, Hans von Balthasar argued the union of the human and divine natures of Christ was achieved not by the "absorption" of human attributes, but by their "assumption". Thus, in his view, the divine nature of Christ was not affected by the human attributes and remained forever divine.

Topics

Nativity and the Holy Name

The Nativity of Jesus impacted the Christological issues about his person from the earliest days of Christianity. Luke's Christology centers on the dialectics of the dual natures of the earthly and heavenly manifestations of existence of the Christ, while Matthew's Christology focuses on the mission of Jesus and his role as the savior. The salvific

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its ...

emphasis of wikisource:Bible (American Standard)/Matthew#1:21, Matthew 1:21 later impacted the theological issues and the devotions to Holy Name of Jesus.

wikisource:Bible (American Standard)/Matthew#1:23, Matthew 1:23 provides a key to the "Emmanuel Christology" of Matthew. Beginning with 1:23, the Gospel of Matthew shows a clear interest in identifying Jesus as "God with us" and in later developing the Emmanuel characterization of Jesus at key points throughout the rest of the Gospel.[''Matthew's Emmanuel'' by David D. Kupp 1997 pp. 220–24] The name 'Emmanuel' does not appear elsewhere in the New Testament, but Matthew builds on it in wikisource:Bible (American Standard)/Matthew#28:20, Matthew 28:20 ("I am with you always, even unto the end of the world") to indicate Jesus will be with the faithful to the end of the age.[''Who do you say that I am?: essays on Christology'' by Jack Dean Kingsbury, Mark Allan Powell, David R. Bauer 1999 p. 17] According to Ulrich Luz, the Emmanuel motif brackets the entire Gospel of Matthew between 1:23 and 28:20, appearing explicitly and implicitly in several other passages.

Crucifixion and resurrection

The accounts of the crucifixion and subsequent resurrection of Jesus

The resurrection of Jesus ( grc-x-biblical, ἀνάστασις τοῦ Ἰησοῦ) is the Christian belief that God raised Jesus on the third day after his crucifixion, starting – or restoring – his exalted life as Christ and Lo ...

provides a rich background for christological analysis, from the canonical Gospels to the Pauline Epistles.

A central element in the christology presented in the Acts of the Apostles is the affirmation of the belief that the death of Jesus by crucifixion happened "with the foreknowledge of God, according to a definite plan".[''New Testament christology'' by Frank J. Matera 1999 p. 67] In this view, as in wikisource:Bible (American Standard)/Acts#2:23, Acts 2:23, the cross is not viewed as a scandal, for the crucifixion of Jesus "at the hands of the lawless" is viewed as the fulfilment of the plan of God.[''Christology'' by Hans Schwarz 1998 pp 132–34] For Paul, the crucifixion of Jesus was not an isolated event in history, but a cosmic event with significant eschatological consequences, as in 1 Corinthians 2:8.

Threefold office

The threefold office (Latin ) of Jesus Christ is a Christianity, Christian doctrine based upon the teachings of the Old Testament. It was described by Eusebius and more fully developed by John Calvin. It states that Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, names and titles), was ...

performed three functions (or "offices") in his earthly ministry – those of prophet, priest, and kingly office of Christ, king. In the Old Testament, the appointment of someone to any of these three positions could be indicated by anointing him or her by pouring oil over the head. Thus, the term ''messiah'', meaning "anointed one", is associated with the concept of the threefold office. While the office of king is that most frequently associated with the Messiah, the role of Jesus as priest is also prominent in the New Testament, being most fully explained in chapters 7 to 10 of the Book of Hebrews.

Mariology

Some Christians, notably Roman Catholics, view Mariology as a key component of Christology.["Mariology Is Christology", in Vittorio Messori, ''The Mary Hypothesis'', Rome: 2005]

In this view, not only is Mariology a logical and necessary consequence of Christology, but without it, Christology is incomplete, since the figure of Mary contributes to a fuller understanding of who Christ is and what he did.

Protestants have criticized Mariology because many of its assertions lack any Biblical foundation. Strong Protestant reaction against Roman Catholic Marian devotion and teaching has been a significant issue for Ecumenism, ecumenical dialogue.

Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) expressed this sentiment about Roman Catholic Mariology when in two separate occasions he stated, "The appearance of a truly Marian awareness serves as the touchstone indicating whether or not the christological substance is fully present" and "It is necessary to go back to Mary, if we want to return to the truth about Jesus Christ."[Raymond Burke, 2008 ''Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons, seminarians, and Consecrated Persons'' p. xxi]

See also

* Catholic spirituality

* Christian messianic prophecies

* Christian views of Jesus

* Christological argument

* Crucifixion of Jesus

* Doubting Thomas

* Eucharist

* Eutychianism

* Five Holy Wounds

* Genealogy of Jesus

* Great Church

* Great Tribulation

* Harrowing of Hell

* Kingship and Kingdom of God

* Last Judgement

* Life of Jesus in the New Testament

* Miracles of Jesus

* Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament

* Religious perspectives on Jesus

* Paterology

* Pneumatology

* Rapture

* Scholastic Lutheran Christology

* Second Coming of Christ

* Transfiguration of Jesus

* Universal resurrection

Notes

References

Sources

;Printed sources

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*Chilton, Bruce. "The Son of Man: Who Was He?” ''Bible Review.'' August 1996, 35+.

*Oscar Cullmann, Cullmann, Oscar. ''The Christology of the New Testament''. trans. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1980.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*Fuller, Reginald H. ''Reginald H. Fuller#The Foundations of New Testament Christology, The Foundations of New Testament Christology''. New York: Scribners, 1965.

* Greene, Colin J.D. ''Christology in Cultural Perspective: Marking Out the Horizons''. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing, 2004.

*

*

* Hodgson, Peter C. ''Winds of the Spirit: A Constructive Christian Theology''. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1994.

*

*Kingsbury, Jack Dean. ''The Christology of Mark's Gospel.'' Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1989.

*Letham, Robert. ''The Work of Christ. Contours of Christian Theology''. Downer Grove: IVP, 1993,

*

*

*

*Donald Macleod (theologian), MacLeod, Donald. ''The Person of Christ: Contours of Christian Theology''. Downer Grove: IVP. 1998,

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Wolfhart Pannenberg, ''Systematic Theology'', T & T Clark, 1994 Vol.2.

*

*

*

*

*

* Schwarz, Hans. ''Christology''. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing, 1998.

*

*

*

*

;Web-sources

Further reading

;Overview

*

*

;Early high Christology

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

;Atonement

*

External links

Encyclopædia Britannica, Christology – full access article

{{Authority control

Christology,

Ancient Christian controversies

Catholic theology and doctrine

Christian terminology

Systematic theology

In

In  A basic christological teaching is that the person of

A basic christological teaching is that the person of  The oldest Christian sources are the writings of Paul the Apostle, Paul. The central Christology of Paul conveys the notion of Christ's pre-existence and the identification of Christ as ''Kyrios (Biblical term), Kyrios''. Both notions already existed before him in the early Christian communities, and Paul deepened them and used them for preaching in the Hellenistic communities.

What exactly Paul believed about the nature of Jesus cannot be determined decisively. In Philippians 2, Paul states that Jesus was preexistent and came to Earth "by taking the form of a servant, being made in human likeness". This sounds like an Incarnation (Christianity), incarnation Christology. In Romans 1:4, however, Paul states that Jesus "was declared with power to be the Son of God by his resurrection from the dead", which sounds like an Adoptionism, adoptionistic Christology, where Jesus was a human being who was "adopted" after his death. Different views would be debated for centuries by Christians and finally settled on the idea that he was both fully human and fully divine by the middle of the 5th century in the Council of Ephesus. Paul's thoughts on Jesus' teachings, versus his nature and being, is more defined, in that Paul believed Jesus was sent as an

The oldest Christian sources are the writings of Paul the Apostle, Paul. The central Christology of Paul conveys the notion of Christ's pre-existence and the identification of Christ as ''Kyrios (Biblical term), Kyrios''. Both notions already existed before him in the early Christian communities, and Paul deepened them and used them for preaching in the Hellenistic communities.

What exactly Paul believed about the nature of Jesus cannot be determined decisively. In Philippians 2, Paul states that Jesus was preexistent and came to Earth "by taking the form of a servant, being made in human likeness". This sounds like an Incarnation (Christianity), incarnation Christology. In Romans 1:4, however, Paul states that Jesus "was declared with power to be the Son of God by his resurrection from the dead", which sounds like an Adoptionism, adoptionistic Christology, where Jesus was a human being who was "adopted" after his death. Different views would be debated for centuries by Christians and finally settled on the idea that he was both fully human and fully divine by the middle of the 5th century in the Council of Ephesus. Paul's thoughts on Jesus' teachings, versus his nature and being, is more defined, in that Paul believed Jesus was sent as an  The synoptic Gospels date from after the writings of Paul. They provide episodes from the life of Jesus and some of his works, but the authors of the New Testament show little interest in an absolute chronology of Jesus or in synchronizing the episodes of his life,Karl Rahner (2004). ''Encyclopedia of theology: a concise Sacramentum mundi'' p. 731 and as in wikisource:Bible (American Standard)/John#21:25, John 21:25, the Gospels do not claim to be an exhaustive list of his works.

Christologies that can be gleaned from the three Synoptic Gospels generally emphasize the humanity of Jesus, his sayings, his Parables of Jesus, parables, and his Miracles of Jesus, miracles. The

The synoptic Gospels date from after the writings of Paul. They provide episodes from the life of Jesus and some of his works, but the authors of the New Testament show little interest in an absolute chronology of Jesus or in synchronizing the episodes of his life,Karl Rahner (2004). ''Encyclopedia of theology: a concise Sacramentum mundi'' p. 731 and as in wikisource:Bible (American Standard)/John#21:25, John 21:25, the Gospels do not claim to be an exhaustive list of his works.

Christologies that can be gleaned from the three Synoptic Gospels generally emphasize the humanity of Jesus, his sayings, his Parables of Jesus, parables, and his Miracles of Jesus, miracles. The