Christianity in the British isles 410-1066 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Celtic Christianity ( kw, Kristoneth; cy, Cristnogaeth; gd, Cr├¼osdaidheachd; gv, Credjue Creestee/Creestiaght; ga, Cr├Łosta├Łocht/Cr├Łost├║lacht; br, Kristeniezh; gl, Cristianismo celta) is a form of Christianity that was common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages. Some writers have described a distinct Celtic Church uniting the Celtic peoples and distinguishing them from adherents of the Roman Church, while others classify Celtic Christianity as a set of distinctive practices occurring in those areas. Varying scholars reject the former notion, but note that there were certain traditions and practices present in both the Irish and British churches that were not seen in the wider Christian world.

Such practices include: a distinctive system for determining the dating of Easter, a style of monastic tonsure, a unique system of

Celtic Christianity ( kw, Kristoneth; cy, Cristnogaeth; gd, Cr├¼osdaidheachd; gv, Credjue Creestee/Creestiaght; ga, Cr├Łosta├Łocht/Cr├Łost├║lacht; br, Kristeniezh; gl, Cristianismo celta) is a form of Christianity that was common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages. Some writers have described a distinct Celtic Church uniting the Celtic peoples and distinguishing them from adherents of the Roman Church, while others classify Celtic Christianity as a set of distinctive practices occurring in those areas. Varying scholars reject the former notion, but note that there were certain traditions and practices present in both the Irish and British churches that were not seen in the wider Christian world.

Such practices include: a distinctive system for determining the dating of Easter, a style of monastic tonsure, a unique system of

According to medieval traditions, Christianity arrived in Britain in the

According to medieval traditions, Christianity arrived in Britain in the  Initially, Christianity was but one of a number of religions: in addition to the native and syncretic local forms of paganism, Roman legionaries and immigrants introduced other cults such as

Initially, Christianity was but one of a number of religions: in addition to the native and syncretic local forms of paganism, Roman legionaries and immigrants introduced other cults such as

At the end of the 6th century, Pope Gregory I dispatched a mission under

At the end of the 6th century, Pope Gregory I dispatched a mission under

According to Bede, Saint Ninian was born about 360 in what is present day Galloway, the son of a chief of the Novantae, apparently a Christian. He studied under

According to Bede, Saint Ninian was born about 360 in what is present day Galloway, the son of a chief of the Novantae, apparently a Christian. He studied under

By the early fifth century the religion had spread to Ireland, which had never been part of the Roman Empire. There were Christians in Ireland before Palladius arrived in 431 as the first missionary bishop sent by Rome. His mission does not seem to have been entirely successful. The subsequent mission of Saint Patrick, traditionally starting in 432,

established churches in conjunction with ''civitates'' like his own in

By the early fifth century the religion had spread to Ireland, which had never been part of the Roman Empire. There were Christians in Ireland before Palladius arrived in 431 as the first missionary bishop sent by Rome. His mission does not seem to have been entirely successful. The subsequent mission of Saint Patrick, traditionally starting in 432,

established churches in conjunction with ''civitates'' like his own in

All monks of the period, and apparently most or all clergy, kept a distinct tonsure, or method of cutting one's hair, to distinguish their social identity as men of the cloth. In Ireland men otherwise wore longish hair, and a shaved head was worn by

All monks of the period, and apparently most or all clergy, kept a distinct tonsure, or method of cutting one's hair, to distinguish their social identity as men of the cloth. In Ireland men otherwise wore longish hair, and a shaved head was worn by

The achievements of

The achievements of

alphabetized

Google Books link 2

* * * * * * * * (trans fr German) * * * * * *

Celtic Christianity ( kw, Kristoneth; cy, Cristnogaeth; gd, Cr├¼osdaidheachd; gv, Credjue Creestee/Creestiaght; ga, Cr├Łosta├Łocht/Cr├Łost├║lacht; br, Kristeniezh; gl, Cristianismo celta) is a form of Christianity that was common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages. Some writers have described a distinct Celtic Church uniting the Celtic peoples and distinguishing them from adherents of the Roman Church, while others classify Celtic Christianity as a set of distinctive practices occurring in those areas. Varying scholars reject the former notion, but note that there were certain traditions and practices present in both the Irish and British churches that were not seen in the wider Christian world.

Such practices include: a distinctive system for determining the dating of Easter, a style of monastic tonsure, a unique system of

Celtic Christianity ( kw, Kristoneth; cy, Cristnogaeth; gd, Cr├¼osdaidheachd; gv, Credjue Creestee/Creestiaght; ga, Cr├Łosta├Łocht/Cr├Łost├║lacht; br, Kristeniezh; gl, Cristianismo celta) is a form of Christianity that was common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages. Some writers have described a distinct Celtic Church uniting the Celtic peoples and distinguishing them from adherents of the Roman Church, while others classify Celtic Christianity as a set of distinctive practices occurring in those areas. Varying scholars reject the former notion, but note that there were certain traditions and practices present in both the Irish and British churches that were not seen in the wider Christian world.

Such practices include: a distinctive system for determining the dating of Easter, a style of monastic tonsure, a unique system of penance

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of Repentance (theology), repentance for Christian views on sin, sins committed, as well as an alternate name for the Catholic Church, Catholic, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox s ...

, and the popularity of going into "exile for Christ". Additionally, there were other practices that developed in certain parts of Britain and Ireland that were not known to have spread beyond particular regions. The term typically denotes the regional practices among the insular churches and their associates rather than actual theological differences.

The term Celtic Church is deprecated by many historians as it implies a unified and identifiable entity entirely separate from that of mainstream Western Christendom. For this reason, many prefer the term Insular Christianity. As Patrick Wormald explained, "One of the common misconceptions is that there was a ''Roman'' Church to which the ''Celtic'' Church was nationally opposed."

Popularized by German historian Lutz von Padberg, the term "''Iroschottisch''" is used to describe this supposed dichotomy between ''Irish-Scottish'' and ''Roman'' Christianity. As a whole, Celtic-speaking areas were part of Latin Christendom at a time when there was significant regional variation of liturgy and structure. But a general collective veneration of the Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, ŽĆ╬¼ŽĆŽĆ╬▒Žé, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

was no less intense in Celtic-speaking areas.

Nonetheless, distinctive traditions developed and spread to both Ireland and Great Britain, especially in the 6th and 7th centuries. Some elements may have been introduced to Ireland by the Romano-British Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick ( la, Patricius; ga, P├Īdraig ; cy, Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, the other patron saints be ...

, and later, others from Ireland to Great Britain through the Irish mission system of Saint Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 ŌĆō 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is toda ...

. However, the histories of the Irish, Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

, Scots, Breton

Breton most often refers to:

*anything associated with Brittany, and generally

** Breton people

** Breton language, a Southwestern Brittonic Celtic language of the Indo-European language family, spoken in Brittany

** Breton (horse), a breed

**Ga ...

, Cornish, and Manx

Manx (; formerly sometimes spelled Manks) is an adjective (and derived noun) describing things or people related to the Isle of Man:

* Manx people

**Manx surnames

* Isle of Man

It may also refer to:

Languages

* Manx language, also known as Manx ...

Churches diverge significantly after the 8th century. Interest in the subject has led to a series of Celtic Christian Revival movements, which have shaped popular perceptions of the Celts and their Christian religious practices.

Definitions

People have conceived of "Celtic Christianity" in different ways at different times. Writings on the topic frequently say more about the time in which they originate than about the historical state of Christianity in the early medieval Celtic-speaking world, and many notions are now discredited in modern academic discourse. One particularly prominent feature ascribed to Celtic Christianity is that it is supposedly inherently distinct from ŌĆō and generally opposed to ŌĆō the Catholic Church. Other common claims include that Celtic Christianity denied the authority of the Pope, was less authoritarian than the Catholic Church, more spiritual, friendlier to women, more connected with nature, and more comfortable dealing withCeltic polytheism

Ancient Celtic religion, commonly known as Celtic paganism, was the religion of the ancient Celtic peoples of Europe. Because the ancient Celts did not have writing, evidence about their religion is gleaned from archaeology, Greco-Roman accounts ...

. One view, which gained substantial scholarly traction in the 19th century, was that there was a "Celtic Church", a significant organised Christian body or denomination uniting the Celtic peoples and separating them from the "Roman" church of continental Europe.An example of this appears in Toynbee Toynbee is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Arnold Toynbee (1852ŌĆō1883), British economic historian

* Arnold Joseph Toynbee (1889ŌĆō1975), British historian

* Geoffrey Toynbee (1885ŌĆō1914), English cricketer

* Henry Toynb ...

's ''Study of History'' (1934ŌĆō1961), which identified Celtic Christianity with an "Abortive Far Western Civilization" ŌĆō the nucleus of a new society, which was prevented from taking root by the Roman Church, Vikings, and Normans. Others have been content to speak of "Celtic Christianity" as consisting of certain traditions and beliefs intrinsic to the Celts.

However, modern scholars have identified problems with all of these claims, and find the term "Celtic Christianity" problematic in and of itself. Modern scholarship roundly rejects the idea of a "Celtic Church" due to the lack of substantiating evidence. Indeed, distinct Irish and British church traditions existed, each with their own practices, and there was significant local variation even within the individual Irish and British spheres. While the Irish and British churches had some traditions in common, these were relatively few. Even these commonalities did not exist due to the "Celticity" of the regions, but due to other historical and geographical factors. Additionally, the Christians of Ireland and Britain were not "anti-Roman"; Celtic areas respected the authority of Rome and the papacy as strongly as any other region of Europe. Caitlin Corning

Caitlin () is a female given name of Irish language, Irish origin. Historically, the Irish name Caitl├Łn was anglicized as Cathleen or Kathleen (given name), Kathleen. In the 1970s, however, non-Irish speakers began pronouncing the name according ...

further notes that the "Irish and British were no more pro-women, pro-environment, or even more spiritual than the rest of the Church."

Developing image of Celtic Christianity

Corning writes that scholars have identified three major strands of thought that have influenced the popular conceptions of Celtic Christianity: * The first arose in theEnglish Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

, when the Church of England declared itself separate from papal authority. Protestant writers of this time popularised the idea of an indigenous British Christianity that opposed the foreign "Roman" church and was purer (and proto-Protestant

Proto-Protestantism, also called pre-Protestantism, refers to individuals and movements that propagated ideas similar to Protestantism before 1517, which historians usually regard as the starting year for the Reformation era. The relationship be ...

) in thought. The English church, they claimed, was not forming a new institution, but casting off the shackles of Rome and returning to its true roots as the indigenous national church of Britain.

* The Romantic movement of the 18th century, in particular Romantic notions of the noble savage

A noble savage is a literary stock character who embodies the concept of the indigene, outsider, wild human, an "other" who has not been "corrupted" by civilization, and therefore symbolizes humanity's innate goodness. Besides appearing in man ...

and the intrinsic qualities of the "Celtic race", further influenced ideas about Celtic Christianity. Romantics idealised the Celts as a primitive, bucolic people who were far more poetic, spiritual, and freer of rationalism than their neighbours. The Celts were seen as having an inner spiritual nature that shone through even after their form of Christianity had been destroyed by the authoritarian and rational Rome.

* In the 20th and 21st centuries, ideas about "Celtic Christians" combined with appeals by certain modern churches, modern pagan

Modern paganism, also known as contemporary paganism and neopaganism, is a term for a religion or family of religions influenced by the various Paganism, historical pre-Christian beliefs of pre-modern peoples in Europe and adjacent areas of No ...

groups, and New Age groups seeking to recover something of ancient spirituality that they believe is missing from the modern world. For these groups, Celtic Christianity becomes a cipher for whatever is lost in the modern religious experience. Corning notes that these notions say more about modern desires than about the reality of Christianity in the Early Middle Ages.

Some associate the early Christians of Celtic-speaking Galatia

Galatia (; grc, ╬ō╬▒╬╗╬▒Žä╬»╬▒, ''Galat├Ła'', "Gaul") was an ancient area in the highlands of central Anatolia, roughly corresponding to the provinces of Ankara and Eski┼¤ehir, in modern Turkey. Galatia was named after the Gauls from Thrace (c ...

(purportedly recipients of Paul's Epistle to the Galatians

The Epistle to the Galatians is the ninth book of the New Testament. It is a letter from Paul the Apostle to a number of Early Christian communities in Galatia. Scholars have suggested that this is either the Roman province of Galatia in sou ...

) with later Christians of north-western Europe's Celtic fringe

The Celtic nations are a cultural area and collection of geographical regions in Northwestern Europe where the Celtic languages and cultural traits have survived. The term ''nation'' is used in its original sense to mean a people who shar ...

.

History

Britain

According to medieval traditions, Christianity arrived in Britain in the

According to medieval traditions, Christianity arrived in Britain in the 1st century

The 1st century was the century spanning AD 1 ( I) through AD 100 ( C) according to the Julian calendar. It is often written as the or to distinguish it from the 1st century BC (or BCE) which preceded it. The 1st century is considered part o ...

. Gildas's 6th-century account dated its arrival to the latter part of the reign of the Roman emperor Tiberius: an account of the seventy disciples discovered at Mount Athos

Mount Athos (; el, ß╝ī╬ĖŽēŽé, ) is a mountain in the distal part of the eponymous Athos peninsula and site of an important centre of Eastern Orthodox monasticism in northeastern Greece. The mountain along with the respective part of the penins ...

in 1854 lists Aristobulus Aristobulus or Aristoboulos may refer to:

*Aristobulus I (died 103 BC), king of the Hebrew Hasmonean Dynasty, 104ŌĆō103 BC

*Aristobulus II (died 49 BC), king of Judea from the Hasmonean Dynasty, 67ŌĆō63 BC

*Aristobulus III of Judea (53 BCŌĆō36 BC), ...

as "bishop of Britain". Medieval accounts of King Lucius, Fagan

Fagan or Phagan is also a Norman-Irish surname, derived from the Latin word 'paganus' meaning ŌĆśruralŌĆÖ or ŌĆśrusticŌĆÖ. Variants of the name Fagan include Fegan and Fagen. It was brought to Ireland during the Anglo-Norman invasion in the twelfth ...

and Deruvian, and Joseph of Arimathea, however, are now usually accounted as pious frauds.

The earliest certain historical evidence of Christianity among the Britons is found in the writings of such early Christian Fathers as Tertullian and Origen in the first years of the 3rd century

The 3rd century was the period from 201 ( CCI) to 300 (CCC) Anno Domini (AD) or Common Era (CE) in the Julian calendar..

In this century, the Roman Empire saw a crisis, starting with the assassination of the Roman Emperor Severus Alexander ...

, although the first Christian communities probably were established at least some decades earlier.

Initially, Christianity was but one of a number of religions: in addition to the native and syncretic local forms of paganism, Roman legionaries and immigrants introduced other cults such as

Initially, Christianity was but one of a number of religions: in addition to the native and syncretic local forms of paganism, Roman legionaries and immigrants introduced other cults such as Mithraism

Mithraism, also known as the Mithraic mysteries or the Cult of Mithras, was a Roman mystery religion centered on the god Mithras. Although inspired by Iranian worship of the Zoroastrian divinity (''yazata'') Mithra, the Roman Mithras is linke ...

. At various times, the Christians risked persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

, although the earliest known Christian martyrs in Britain ŌĆō Saint Alban and "Amphibalus

Amphibalus is a venerated early Christian priest said to have converted Saint Alban to Christianity. He occupied a place in British hagiography almost as revered as Alban himself. According to many hagiographical accounts, including those of Gil ...

" ŌĆō probably lived in the early 4th century. Julius and Aaron

Julius and Aaron (also Julian) were two Romano-British Christian saints who were martyred around the third century. Along with Saint Alban, they are the only named Christian martyrs from Roman Britain. Most historians place the martyrdom in Cae ...

, citizens of Caerleon, were said to have been martyred during the Diocletianic Persecution, although there is no textual or archaeological evidence to support the folk etymology

Folk etymology (also known as popular etymology, analogical reformation, reanalysis, morphological reanalysis or etymological reinterpretation) is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a more famili ...

of Lichfield as deriving from another thousand martyrs during the same years.

Christianization intensified with the legalisation of the Christian religion under Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

in the early 4th century and its promotion by subsequent Christian emperors. Three Romano-British bishops, including Archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdi ...

Restitutus of London, are known to have been present at the Synod of Arles in 314. Others attended the Council of Serdica The Council of Serdica, or Synod of Serdica (also Sardica located in modern day Sofia, Bulgaria), was a synod convened in 343 at Serdica in the civil diocese of Dacia, by Emperors Constans I, augustus in the West, and Constantius II, augustus in ...

in 347 and the Council of Ariminum

The Council of Ariminum, also known after the city's modern name as the Council of Rimini, was an early Christian church synod.

In 358, the Roman Emperor Constantius II requested two councils, one of the western bishops at Ariminum and one of ...

in 360. A number of references to the church in Roman Britain are also found in the writings of 4th-century Christian fathers. Britain was the home of Pelagius, who opposed Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 ŌĆō 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

's doctrine of original sin

Original sin is the Christian doctrine that holds that humans, through the fact of birth, inherit a tainted nature in need of regeneration and a proclivity to sinful conduct. The biblical basis for the belief is generally found in Genesis 3 (t ...

; St Germanus was said to have visited the island in part to oppose the bishops who advocated his heresy.

Around 367, the Great Conspiracy saw the troops along Hadrian's Wall

Hadrian's Wall ( la, Vallum Aelium), also known as the Roman Wall, Picts' Wall, or ''Vallum Hadriani'' in Latin, is a former defensive fortification of the Roman province of Britannia, begun in AD 122 in the reign of the Emperor Hadrian. R ...

mutiny, allowing the Picts to overrun the northern areas of Roman Britain (in some cases joining in), in concert with Irish and Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

attacks on the coast. The Roman provinces seem to have been retaken by Theodosius the Elder

Flavius Theodosius (died 376), also known as Count Theodosius ( la, Theodosius comes) or Theodosius the Elder ( la, Theodosius Major), was a senior military officer serving Valentinian I () and the western Roman empire during Late Antiquity. Unde ...

the next year, but many Romano-Britons

The Romano-British culture arose in Britain under the Roman Empire following the Roman conquest in AD 43 and the creation of the province of Britannia. It arose as a fusion of the imported Roman culture with that of the indigenous Britons, a ...

had already been killed or taken as slaves. In 407, Constantine III declared himself "emperor of the West" and withdrew his legions to Gaul. The Byzantine historian Zosimus Zosimus, Zosimos, Zosima or Zosimas may refer to:

People

*

* Rufus and Zosimus (died 107), Christian saints

* Zosimus (martyr) (died 110), Christian martyr who was executed in Umbria, Italy

* Zosimos of Panopolis, also known as ''Zosimus Alchemi ...

() stated that Constantine's neglect of the area's defense against Irish and Saxon raids and invasions caused the Britons and Gauls to fully revolt from the Roman Empire, rejecting Roman law and reverting to their native customs. In any case, Roman authority was greatly weakened following the Visigoths' sack of Rome in 410. Medieval legend attributed widespread Saxon immigration to mercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any o ...

hired by the British king Vortigern. The Saxon communities followed a form of Germanic paganism, driving Christian Britons back to Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany or subjugating them under kingdoms with no formal church presence.

Fifth and sixth century Britain, although poorly attested, saw the "Age of Saints

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual res ...

" among the Welsh. Saint Dubric

Dubricius or Dubric ( cy, Dyfrig; Norman-French: ''Devereux''; c. 465 – c. 550) was a 6th-century British ecclesiastic venerated as a saint. He was the evangelist of Ergyng ( cy, Erging) (later Archenfield, Herefordshire) and much of ...

, Saint Illtud

Saint Illtud (also spelled Illtyd, Eltut, and, in Latin, Hildutus), also known as Illtud Farchog or Illtud the Knight, is venerated as the abbot teacher of the divinity school, Bangor Illtyd, located in Llanilltud Fawr (Llantwit Major) in Gl ...

, and others first completed the Christianization of Wales Christianity is the majority religion in Wales. From 1534 until 1920 the established church was the Church of England, but this was disestablished in Wales in 1920, becoming the still Anglican but self-governing Church in Wales. Wales also has a ...

. Unwilling or unable to missionize among the Saxons in England, Briton refugees and missionaries such as Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick ( la, Patricius; ga, P├Īdraig ; cy, Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, the other patron saints be ...

and Finnian of Clonard

Finnian of Clonard ('Cluain Eraird') ŌĆō also Finian, Fion├Īn or Fionn├Īn in Irish; or Finianus and Finanus in its Latinised form (470ŌĆō549) ŌĆō was one of the early Irish monastic saints, who founded Clonard Abbey in modern-day County Meath. ...

were then responsible for the Christianization of Ireland and made up the Seven Founder Saints of Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Berta├©yn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period of ...

. The Irish in turn made Christians of the Picts and English. Saint Columba then began the conversion of the D├Īl Riata and the other peoples of Scotland, although native saints such as Mungo also arose. The history of Christianity in Cornwall

Christianity in Cornwall began in the 4th or 5th century AD when Western Christianity was introduced as in the rest of Roman Britain. Over time it became the official religion, superseding previous Celtic and Roman practices. Early Christianit ...

is more obscure, but the native church seems to have been greatly strengthened by Welsh and Irish missionaries such as Saints Petroc, Piran, and Breaca. Extreme weather (as around 535) and the attendant famines and disease, particularly the arrival of the Plague of Justinian in Wales around 547 and Ireland around 548, may have contributed to these missionary efforts.

The title of "saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-┼Ā, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

" was used quite broadly by British, Irish, and English Christians. Extreme cases are Irish accounts of 's presiding over 3,300 saints and Welsh claims that Bardsey Island held the remains of 20,000. More often, the title was given to the founder of any ecclesiastical settlement, which would thenceforth be known as their ''llan Llan may be:

* Llan (placename), a Celtic morpheme, or element, common in British placenames

** A short form for any placename .

* Llan, Powys, a Welsh village near Llanbrynmair

* Llan the Sorcerer

La Lunatica

Lacuna

Lady Bullseye

Lady De ...

''. Such communities were organized on tribal models: founding saints were almost invariably lesser members of local dynasties, they were not infrequently married, and their successors were often chosen from among their kin. In the 6th century, the " Three Saintly Families of Wales" ŌĆō those of the invading Irish Brychan and Hen Ogledd's Cunedda Wledig and Caw of Strathclyde

King Caw or Cawn ( fl. 495ŌĆō501 AD) was a semi-legendary king of Strathclyde in Scotland.

Very little hard fact is known of him. He flourished in the ''Hen Ogledd'' Period of Sub-Roman Britain and ruled from a castle at ''Alt Clut''. Legend holds ...

ŌĆō displaced many of the local Siluria

The Silures ( , ) were a powerful and warlike tribe or tribal confederation of ancient Britain, occupying what is now south east Wales and perhaps some adjoining areas. They were bordered to the north by the Ordovices; to the east by the Dobunn ...

n rulers in favor of their own families and clans. By some estimates, these traditions produced over 800 pre-congregational saints that were venerated locally in Wales, but invasions by Saxons, Irishmen, Vikings, Normans, and others destroyed many ecclesiastical records. Similarly, the distance from Rome, hostility to native practices and cults, and relative unimportance of the local sees has left only two local Welsh saints in the General Roman Calendar: Saints David and Winifred Winifred is a feminine given name, an anglicization of Welsh ''Gwenffrewi'', from ''gwen'', "fair", and ''ffrew'', "stillness". It may refer to:

People

* Saint Winifred

* Winifred Atwell (1914ŌĆō1983), a pianist who enjoyed great popularity in Bri ...

.

Insular Christianity developed distinct traditions and practices, most pointedly concerning the ''computus

As a moveable feast, the date of Easter is determined in each year through a calculation known as (). Easter is celebrated on the first Sunday after the Paschal full moon, which is the first full moon on or after 21 March (a fixed approxi ...

'' of Easter, as it produced the most obvious signs of disunity: the old and new methods did not usually agree, causing Christians following one system to begin celebrating the feast of the Resurrection while others continued to solemnly observe Lent

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke ...

. Monasticism

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic life plays an important role ...

spread widely; the Llandaff Charters

The Book of Llandaff ( la, Liber Landavensis; cy, Llyfr Llandaf, ', or '), is the chartulary of the cathedral of Llandaff, a 12th-century compilation of documents relating to the history of the diocese of Llandaff in Wales. It is written primaril ...

record over fifty religious foundations in southeast Wales alone. Although the ''clasau A clas (Welsh ''clasau'') was a native Christian church in early medieval Wales. Unlike later Norman monasteries, which were made up of a main religious building supported by several smaller buildings, such as cloisters and kitchens, a clas w ...

'' were rather modest affairs, great monasteries and monastic schools

Monastic schools ( la, Scholae monasticae) were, along with cathedral schools, the most important institutions of higher learning in the Latin West from the early Middle Ages until the 12th century. Since Cassiodorus's educational program, the stan ...

also developed at Llantwit Major

Llantwit Major ( cy, Llanilltud Fawr) is a town and community in Wales on the Bristol Channel coast. It is one of four towns in the Vale of Glamorgan, with the third largest population (13,366 in 2001) after Barry and Penarth, and ahead of Cowb ...

('), Bangor, and Iona

Iona (; gd, ├ī Chaluim Chille (IPA: łi╦É╦łxa╔½╠¬╔»im╦ł├¦i╩Ä╔Ö, sometimes simply ''├ī''; sco, Iona) is a small island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though there ...

. The tonsure differed from that elsewhere and also became a point of contention. A distinction that became increasingly important was the nature of church organisation: some monasteries were led by married clergy, inheritance of religious offices was common (in Wales, as late as the 12th century), and illegitimacy was treated much more leniently with fathers simply needing to acknowledge the child for him to inherit an equal share with his brothers. Prior to their conquest by England, most churches have records of bishops and priests but not an established parish system. Pre-conquest, most Christians would not attend regular services but relied on members of the monastic communities who would occasionally make preaching tours through the area.

Wales

At the end of the 6th century, Pope Gregory I dispatched a mission under

At the end of the 6th century, Pope Gregory I dispatched a mission under Augustine of Canterbury

Augustine of Canterbury (early 6th century ŌĆō probably 26 May 604) was a monk who became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 597. He is considered the "Apostle to the English" and a founder of the English Church.Delaney '' ...

to convert the Anglo-Saxons, establish new sees and churches throughout their territories, and reassert papal authority over the native church. Gregory intended for Augustine to become the metropolitan bishop over all of southern Britain, including the existing dioceses under Welsh and Cornish control. Augustine met with British bishops in a series of conferences ŌĆō known as the Synod of Chester

The Synod of Chester (Medieval Latin: ''Sinodus Urbis Legion(um)'') was an ecclesiastical council of bishops held in Chester in the late 6th or early 7th century. The period is known from only a few surviving sources, so dates and a ...

ŌĆō that attempted to assert his authority and to compel them to abandon aspects of their service that had fallen out of line with Roman practice. The Northumbrian cleric Bede

Bede ( ; ang, BŪŻda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

's '' Ecclesiastical History of the English People'' is the only surviving account of these meetings: according to it, some of the clerics of the nearest British province met Augustine at a site on the border of the Kingdom of Kent that was known thereafter as Augustine's Oak. Augustine focused on seeking assistance for his work among the Saxons and reforming the Britons' obsolete method for calculating Easter; the clerics responded that they would need to confer with their people and await a larger assembly. Bede relates that the bishops particularly consulted a hermit on how to respond. He told them to respond based on Augustine's conduct: were he to rise to greet them, they would know him for a humble servant of Christ and should submit to his authority but, were he to remain seated, they would know him to be arrogant and prideful and should reject him. As it happened, Augustine did keep his seat, provoking outrage. In the negotiations that followed, he offered to allow the Britons to maintain all their native customs but three: they should adopt Rome's more advanced method of calculating the date of Easter, reform their baptismal ritual, and join the missionary efforts among the Saxons. The British clerics rejected all of these, as well as Augustine's authority over them. John Edward Lloyd

Sir John Edward Lloyd (5 May 1861 – 20 June 1947) was a Welsh historian, He was the author of the first serious history of the country's formative years, ''A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest'' (1911).

Ano ...

argues that the primary reason for the British bishops' rejection of Augustine ŌĆō and especially his call for them to join his missionary effort ŌĆō was his claim to sovereignty over them, given that his see would be so deeply entwined with Anglo-Saxon Kent.

The death of hundreds of British clerics to the pagan king Æthelfrith of the Kingdom of Northumbria around 616 at the Battle of Chester was taken by Bede as fulfillment of the prophecy made by Augustine of Canterbury following the Synod of Chester. The prophecy stated that the British church would receive war and death from the Saxons if they refused to proselytise. Despite the inaccuracies of their system, the Britons did not adopt the Roman and Saxon la, computus, label=none until induced to do so around 768 by "Archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdi ...

" Elfodd of "Gwynedd". The Norman invasion of Wales finally brought Welsh dioceses under England's control. The development of legends about the mission of Fagan and Deruvian and Philip the Apostle's dispatch of Joseph of Arimathea in part aimed to preserve the priority and authority of the native establishments at St David's, Llandaff, and Glastonbury. It was not until the death of Bishop Bernard () that St Davids finally abandoned its claims to metropolitan status and submitted to the Province of Canterbury

The Province of Canterbury, or less formally the Southern Province, is one of two ecclesiastical provinces which constitute the Church of England. The other is the Province of York (which consists of 12 dioceses).

Overview

The Province consist ...

, by which point the popularity of Geoffrey of Monmouth's pseudohistorical '' Historia Regum Britanniae'' had begun spreading these inventions further afield. Such ideas were used by mediaeval anti-Roman movements such as the Lollards and followers of John Wycliffe, as well as by English Catholics during the English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

. The legend that Jesus himself visited Britain is referred to in William Blake's 1804 poem "And did those feet in ancient time

"And did those feet in ancient time" is a poem by William Blake from the preface to his epic '' Milton: A Poem in Two Books'', one of a collection of writings known as the Prophetic Books. The date of 1804 on the title page is probably when the ...

". The words of Blake's poem were set to music in 1916 by Hubert Parry as the well-known song "Jerusalem".

Scotland

According to Bede, Saint Ninian was born about 360 in what is present day Galloway, the son of a chief of the Novantae, apparently a Christian. He studied under

According to Bede, Saint Ninian was born about 360 in what is present day Galloway, the son of a chief of the Novantae, apparently a Christian. He studied under Martin of Tours

Martin of Tours ( la, Sanctus Martinus Turonensis; 316/336 ŌĆō 8 November 397), also known as Martin the Merciful, was the third bishop of Tours. He has become one of the most familiar and recognizable Christian saints in France, heralded as the ...

before returning to his own land about 397. He established himself at Whithorn where he built a church of stone, "Candida Casa". Tradition holds that Ninian established an episcopal see at the Candida Casa in Whithorn, and named the see for Saint Martin of Tours. He converted the southern Picts to Christianity, and died around 432. Many Irish saints trained at the "Candida Casa", such as Tigernach of Clones

Tigernach mac Coirpri (''d''. 549) was an early Irish saint, patron saint of Clones (Co. Monaghan) in the province of Ulster.

Background

Tigernach or Tiarnach of Clones (anglicised ''Tierney'') was one of the pre-eminent saints of the territo ...

, Ciar├Īn of Clonmacnoise, and Finnian of Movilla. Ninian's work was carried on by Palladius, who left Ireland to work among the Picts. The mission to the southern Picts apparently met with some setbacks, as Patrick charged Coroticus and the "apostate Picts" with conducting raids on the Irish coast and seizing Christians as slaves. Ternan

Saint Ternan (''fl.'' fifth or sixth century) is venerated as the "Bishop of the Picts". Not much is known of his life. Different historians place him either at the mid-fifth century or the latter part of the sixth. Those who place him in the earl ...

and Saint Serf followed Palladius. Serf was the teacher of Saint Mungo, the apostle of Strathclyde, and patron saint of Glasgow.

Cornwall and West Devon

A Welshman of noble birth, Saint Petroc was educated in Ireland. He set out in a small boat with a few followers. In a type of ''peregrinatio'', they let God determine their course. The winds and tides brought them to the Padstow estuary.Kevin of Glendalough

Saint Kevin (modern Irish '; Old Irish ', '; latinized '; 498 (reputedly)ŌĆō3 June 618) is an Irish saint, known as the founder and first abbot of Glendalough in County Wicklow, Ireland. His feast day is 3 June.

Early life

Kevin's life is not ...

was a student of Petroc. Saint Endelienta

Saint Endelienta (also Endelient, Edellienta or Endellion) was a Cornish saint of the 5th and 6th century. She is believed to be a daughter of the Welsh King Brychan, and a native of South Wales who travelled to North Cornwall to join her sibl ...

was the daughter of the Welsh king Brychan. She also travelled to Cornwall ŌĆō that is ancient Dumnonia ŌĆō to evangelize the locals as did St Nonna

Non (also Nonna or Nonnita) was, according to Christian tradition, the mother of Saint David, the patron saint of Wales.

Legend

The ''Life of St David'' was written around 1095 by Rhigyfarch, and is our main source of knowledge for the lives ...

mother of St David

Saint David ( cy, Dewi Sant; la, Davidus; ) was a Welsh bishop of Mynyw (now St Davids) during the 6th century. He is the patron saint of Wales. David was a native of Wales, and tradition has preserved a relatively large amount of detail abo ...

who travelled on to Brittany. Her brother Nectan of Hartland

Saint Nectan, sometimes styled Saint Nectan of Hartland, was a 5th-century holy man who lived in Stoke, Hartland, in the nowadays English, and at the time brythonic-speaking county of Devon, where the prominent St Nectan's Church, Hartland is d ...

worked in Devon. Saint Piran is the patron saint of tin miners. An Irishman, Ciaran, he is said to have 'floated' across to Cornwall after being thrown into the sea tied to a millstone. He has been identified on occasion with Ciar├Īn of Saigir

Ciar├Īn of Saigir (5th century – ), also known as Ciar├Īn mac Luaigne or Saint Kieran ( cy, Cieran), was one of the Twelve Apostles of Ireland and is considered the first saint to have been born in Ireland,''Catholic Online''St. Kier ...

.

Ireland

By the early fifth century the religion had spread to Ireland, which had never been part of the Roman Empire. There were Christians in Ireland before Palladius arrived in 431 as the first missionary bishop sent by Rome. His mission does not seem to have been entirely successful. The subsequent mission of Saint Patrick, traditionally starting in 432,

established churches in conjunction with ''civitates'' like his own in

By the early fifth century the religion had spread to Ireland, which had never been part of the Roman Empire. There were Christians in Ireland before Palladius arrived in 431 as the first missionary bishop sent by Rome. His mission does not seem to have been entirely successful. The subsequent mission of Saint Patrick, traditionally starting in 432,

established churches in conjunction with ''civitates'' like his own in Armagh

Armagh ( ; ga, Ard Mhacha, , "Macha's height") is the county town of County Armagh and a city in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland ŌĆō the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Pri ...

; small enclosures in which groups of Christians, often of both sexes and including the married, lived together, served in various roles and ministered to the local population. Patrick set up diocesan structures with a hierarchy of bishops, priests, and deacons. During the late 5th and 6th centuries true monasteries became the most important centres: in Patrick's own see of Armagh the change seems to have happened before the end of the 5th century, thereafter the bishop was the abbot also. Within a few generations of the arrival of the first missionaries the monastic and clerical class of the isle had become fully integrated with the culture of Latin letters. Besides Latin, Irish ecclesiastics developed a written form of Old Irish. Others who influenced the development of Christianity in Ireland include Brigid (ŌĆē451 ŌĆō 525), Saint Moluag

Saint Moluag (c. 510 ŌĆō 592; also known as ''Lua'', ''Luan'', ''Luanus'', ''Lugaidh'', ''Moloag'', ''Molluog'', ''Molua'', ''Murlach'', ''Malew''

( 510 ŌĆō 592, who evangelised in the area of present-day Scotland) and Saint Caill├Łn

Saint Caillin (fl. c.570) was an Irish medieval saint and monastic founder. His Feast day is celebrated on 13 November. The patron saint of Fenagh, County Leitrim, Caillin was born in the 6th century and founded a monastic settlement at Fenagh ...

(fl. ).

Universal practice

Connections with the greaterLatin West

Greek East and Latin West are terms used to distinguish between the two parts of the Greco-Roman world and of Medieval Christendom, specifically the eastern regions where Greek was the '' lingua franca'' (Greece, Anatolia, the southern Balkans, t ...

brought the nations of Britain and Ireland into closer contact with the orthodoxy of the councils. The customs and traditions particular to Insular Christianity became a matter of dispute, especially the matter of the proper calculation of Easter. In addition to Easter dating, Irish scholars and cleric-scholars in continental Europe found themselves implicated in theological controversies but it is not always possible to distinguish when a controversy was based on matters of substance or on political grounds or xenophobic sentiments. Synods were held in Ireland, Gaul, and England (e.g. the Synod of Whitby) at which Irish and British religious rites were rejected but a degree of variation continued in Britain after the Ionan church accepted the Roman date.

The Easter question was settled at various times in different places. The following dates are derived from Haddan and Stubbs: southern Ireland, 626ŌĆō628; northern Ireland, 692; Northumbria (converted by Irish missions), 664; East Devon and Somerset, the Britons under Wessex, 705; the Picts, 710; Iona, 716ŌĆō718; Strathclyde, 721; North Wales, 768; South Wales, 777. Cornwall held out the longest of any, perhaps even, in parts, to the time of Bishop Aedwulf of Crediton (909).

A uniquely Irish penitential system was eventually adopted as a universal practice of the Church by the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215.

Pan-Celtic traditions

Caitlin Corning identifies four customs that were common to both the Irish and British churches but not used elsewhere in the Christian world.Easter calculation

Easter was originally dated according to Hebrew calendar, which tried to place Passover on the first full moon following theSpring equinox Spring equinox or vernal equinox or variations may refer to:

* March equinox, the spring equinox in the Northern Hemisphere

* September equinox, the spring equinox in the Southern Hemisphere

Other uses

* Nowruz, Persian/Iranian new year which be ...

but did not always succeed. In his '' Life of Constantine'', Eusebius records that the First Council of Nicaea (325) decided that all Christians should observe a common date for Easter separate from the Jewish calculations, according to the practice of the bishops of Rome and Alexandria. Calculating the proper date of Easter (''computus'') then became a complicated process involving a lunisolar calendar

A lunisolar calendar is a calendar in many cultures, combining lunar calendars and solar calendars. The date of Lunisolar calendars therefore indicates both the Moon phase and the time of the solar year, that is the position of the Sun in the Ea ...

, finding the first Sunday after an idealized Passover on the first full moon after the equinox.

Various tables were drawn up, aiming to produce the necessary alignment between the solar year and the phases of the calendrical moon. The less exact 8-year cycle was replaced by (or by the time of) Augustalis's treatise " On the measurement of Easter", which includes an 84-year cycle based on Meton. This was introduced to Britain, whose clerics at some point modified it to use the Julian calendar's original equinox on 25 March instead of the Nicaean equinox, which had already drifted to 21 March. This calendar was conserved by the Britons and Irish while the Romans and French began to use the Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literature ...

cycle of 532 years. The Romans (but not the French) then adopted the still-better work of Dionysius

The name Dionysius (; el, ╬ö╬╣╬┐╬ĮŽŹŽā╬╣╬┐Žé ''Dionysios'', "of Dionysus"; la, Dionysius) was common in classical and post-classical times. Etymologically it is a nominalized adjective formed with a -ios suffix from the stem Dionys- of the name ...

in 525, which brought them into harmony with the Church of Alexandria.

In the early 600s Christians in Ireland and Britain became aware of the divergence in dating between them and those in Europe. The first clash came in 602 when a synod of French bishops opposed the practices of the monasteries established by St Columbanus; Columbanus appealed to Pope Gregory I but received no answer and finally moved from their jurisdiction. It was a primary concern for St Augustine and his mission, although Oswald's flight to D├Īl Riata and eventual restoration to his throne meant that Celtic practice was introduced to Northumbria until the 664 synod in Whitby. The groups furthest away from the Gregorian mission

The Gregorian missionJones "Gregorian Mission" ''Speculum'' p. 335 or Augustinian missionMcGowan "Introduction to the Corpus" ''Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature'' p. 17 was a Christian mission sent by Pope Gregory the Great in 596 to conver ...

were generally the readiest to acknowledge the superiority of the new tables: the bishops of southern Ireland adopted the continental system at the Synod of Mag L├®ne

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word ''synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin word meani ...

(); the Council of Birr saw the northern Irish bishops follow suit. The abbey at Iona and its satellites held out until 716, while the Welsh did not adopt the Roman and Saxon ''computus'' until induced to do so around 768 by Elfodd, "archbishop" of Bangor.

Monastic tonsure

All monks of the period, and apparently most or all clergy, kept a distinct tonsure, or method of cutting one's hair, to distinguish their social identity as men of the cloth. In Ireland men otherwise wore longish hair, and a shaved head was worn by

All monks of the period, and apparently most or all clergy, kept a distinct tonsure, or method of cutting one's hair, to distinguish their social identity as men of the cloth. In Ireland men otherwise wore longish hair, and a shaved head was worn by slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slaveŌĆösomeone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

s.

The prevailing Roman custom was to shave a circle at the top of the head, leaving a halo of hair or ''corona''; this was eventually associated with the imagery of Christ's crown of thorns. The early material referring to the Celtic tonsure emphasizes its distinctiveness from the Roman alternative and invariably connects its use to the Celtic dating of Easter. Those preferring the Roman tonsure considered the Celtic custom extremely unorthodox, and associated it with the form of tonsure worn by the heresiarch Simon Magus. This association appears in a 672 letter from Saint Aldhelm

Aldhelm ( ang, Ealdhelm, la, Aldhelmus Malmesberiensis) (c. 63925 May 709), Abbot of Malmesbury Abbey, Bishop of Sherborne, and a writer and scholar of Latin poetry, was born before the middle of the 7th century. He is said to have been the so ...

to King Geraint of Dumnonia, but it may have been circulating since the Synod of Whitby. The tonsure is also mentioned in a passage, probably of the 7th century but attributed wrongly to Gildas: "''Britones toti mundo contrarii, moribus Romanis inimici, non solum in missa sed in tonsura etiam''" ("Britons are contrary to the whole world, enemies of Roman customs, not only in the Mass but also in regard to the tonsure").

The exact shape of the Irish tonsure is unclear from the early sources, although they agree that the hair was in some way shorn over the head from ear to ear. In 1639 James Ussher suggested a semi-circular shape, rounded in the front and culminating at a line between the ears. This suggestion was accepted by many subsequent writers, but in 1703 Jean Mabillon

Dom Jean Mabillon, O.S.B., (; 23 November 1632 ŌĆō 27 December 1707) was a French Benedictine monk and scholar of the Congregation of Saint Maur. He is considered the founder of the disciplines of palaeography and diplomatics.

Early life

Mabil ...

put forth a new hypothesis, claiming that the entire forehead was shaven back to the ears. Mabillon's version was widely accepted, but contradicts the early sources. In 2003 Daniel McCarthy suggested a triangular shape, with one side between the ears and a vertex towards the front of the head. The '' Collectio canonum Hibernensis'' cites the authority of Saint Patrick as indicating that the custom originated with the swineherd of L├│egaire mac N├®ill, the king who opposed Patrick.

Penitentials

In Christian Ireland ŌĆō as well as Pictish and English peoples they Christianised ŌĆō a distinctive form ofpenance

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of Repentance (theology), repentance for Christian views on sin, sins committed, as well as an alternate name for the Catholic Church, Catholic, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox s ...

developed, where confession was made privately to a priest, under the seal of secrecy, and where penance was given privately and ordinarily performed privately as well. Certain handbooks were made, called "penitentials", designed as a guide for confessors and as a means of regularising the penance given for each particular sin.

In antiquity, penance had been a public ritual. Penitents were divided into a separate part of the church during liturgical worship, and they came to Mass wearing sackcloth and ashes in a process known as ''exomologesis'' that often involved some form of general confession. There is evidence that this public penance was preceded by a private confession to a bishop or priest (''sacerdos''), and it seems that, for some sins, private penance was allowed instead. Nonetheless, penance and reconciliation was prevailingly a public rite (sometimes unrepeatable), which included absolution at its conclusion.

The Irish penitential practice spread throughout the continent, where the form of public penance had fallen into disuse. Saint Columbanus was credited with introducing the ''medicamenta paentitentiae'', the "medicines of penance", to Gaul at a time when they had come to be neglected. Though the process met some resistance, by 1215 the practice had become established as the norm, with the Fourth Lateran Council establishing a canonical statute requiring confession at a minimum of once per year.

Peregrinatio

A final distinctive tradition common across Britain and Ireland was the popularity of ''peregrinatio pro Christo'' ("exile for Christ"). The term ''peregrinatio'' is Latin, and referred to the state of living or sojourning away from one's homeland in Roman law. It was later used by theChurch Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

, in particular Saint Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 ŌĆō 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

, who wrote that Christians should live a life of ''peregrinatio'' in the present world while awaiting the Kingdom of God

The concept of the kingship of God appears in all Abrahamic religions, where in some cases the terms Kingdom of God and Kingdom of Heaven are also used. The notion of God's kingship goes back to the Hebrew Bible, which refers to "his kingdom" b ...

. Augustine's version of ''peregrinatio'' spread widely throughout the Christian church, but it took two additional unique meanings in Celtic countries.

In the first sense, the penitentials prescribed permanent or temporary ''peregrinatio'' as penance for certain infractions. Additionally, there was a tradition of undertaking a voluntary ''peregrinatio pro Christo'', in which individuals permanently left their homes and put themselves entirely in God's hands. In the Irish tradition there were two types of such ''peregrinatio'', the "lesser" peregrinatio, involving leaving one's home area but not the island, and the "superior" peregrinatio, which meant leaving Ireland for good. This voluntary exile to spend one's life in a foreign land far from friends and family came to be termed the "white martyrdom".

Most ''peregrini'' or exiles of this type were seeking personal spiritual fulfilment, but many became involved in missionary endeavours. The Briton Saint Patrick became the evangelist of Ireland during what he called his ''peregrinatio'' there, while Saint Samson left his home to ultimately become bishop in Brittany. The Irishmen Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 ŌĆō 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is toda ...

and Columbanus similarly founded highly important religious communities after leaving their homes. Irish-educated English Christians such as Gerald of Mayo, the Two Ewalds, Willehad, Willibrord, Wilfrid, Ceolfrith, and other English all followed these Irish traditions.

Other British and Irish traditions

A number of other distinctive traditions and practices existed (or are taken to have existed) in Britain or Ireland, but are not known to have been in use across the entire region. Different writers and commenters have identified different traditions as representative of so-called Celtic Christianity.Monasticism

Monastic spirituality came to Britain and then Ireland from Gaul, by way of L├®rins, Tours, and Auxerre. Its spirituality was heavily influenced by the Desert Fathers. According to Richard Woods, the familial, democratic, and decentralized aspects of Egyptian Christianity were better suited to structures and values of Celtic culture than was a legalistic diocesan form. Monasteries tended to be cenobitical in that monks lived in separate cells but came together for common prayer, meals, and other functions. Some more austere ascetics became hermits living in remote locations in what came to be called the "green martyrdom". An example of this would be Kevin of Glendalough andCuthbert

Cuthbert of Lindisfarne ( ŌĆō 20 March 687) was an Anglo-Saxon saint of the early Northumbrian church in the Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit, associated with the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne in the Kingdom of Nor ...

of Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne, also called Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th century AD; it was an important ...

.

One controversial belief is that the true ecclesiastical power in the Celtic world lay in the hands of abbots of monasteries, rather than bishops of dioceses. While this may have been the case for centuries in most of Ireland, it was never the rule throughout the Celtic world at large. It is certain that the ideal of monasticism was universally esteemed in Celtic Christianity. This was especially true in Ireland and areas evangelised by Irish missionaries, where monasteries and their abbots came to be vested with a great deal of ecclesiastical and secular power. Following the growth of the monastic movement in the 6th century, abbots controlled not only individual monasteries, but also expansive estates and the secular communities that tended them. As monastics, abbots were not necessarily ordained (i.e. they were not necessarily priests

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in p ...

or bishops). They were usually descended from one of the many Irish royal families, and the founding regulations of the abbey sometimes specified that the abbotcy should if possible be kept within one family lineage.

This focus on the monastery has led some scholars, most notably Kathleen Hughes

Kathleen Hughes (born Elizabeth Margaret von Gerkan; November 14, 1928) is an American actress.

Early life

Hughes' uncle, F. Hugh Herbert, was a playwright who authored ''Kiss and Tell'' and ''The Moon Is Blue''. Her desire to act was inspired ...

, to argue that the monastic system came to be the dominant ecclesiastical structure in the Irish church, essentially replacing the earlier episcopal structure of the type found in most of the rest of the Christian world. Hughes argued that the ''paruchia'', or network of monasteries attached to an abbey, replaced the diocese as the chief administrative unit of the church, and the position of Abbot largely replaced that of bishop in authority and prominence. According to this model, bishops were still needed, since certain sacramental functions were reserved only for the ordained, but they had little authority in the ecclesiastical structure.

However, more recent scholarship, particularly the work of Donnchadh ├ō Corr├Īin and Richard Sharpe, has offered a more nuanced view of the interrelationships between the monastic system and the traditional Church structures. Sharpe argues that there is no evidence that the ''paruchia'' overrode the diocese, or that the abbot replaced the Bishop; Bishops still exercised ultimate spiritual authority and remained in charge of the diocesan clergy. But either way, the monastic ideal was regarded as the utmost expression of the Christian life.

The focus on powerful abbots and monasteries was limited to the Irish Church, however, and not in Britain. The British church employed an episcopal structure corresponding closely to the model used elsewhere in the Christian world.

Irish monasticism was notable for its permeability. In permeable monasticism, people were able to move freely in and out of the monastic system at different points of life. Young boys and girls would enter the system to pursue Latin scholarship. Students would sometimes travel from faraway lands to enter the Irish monasteries. When these students became adults, they would leave the monastery to live out their lives. Eventually, these people would retire back to secure community provided by the monastery and stay until their death. However, some would stay within the monastery and become leaders. Since most of the clergy were Irish, native traditions were well-respected. Permeable monasticism popularised the use of vernacular and helped mesh the norms of secular and monastic element in Ireland, unlike other parts of Europe where monasteries were more isolated. Examples of these intertwining motifs can be seen in the hagiographies of St. Brigid

Saint Brigid of Kildare or Brigid of Ireland ( ga, Naomh Br├Łd; la, Brigida; 525) is the patroness saint (or 'mother saint') of Ireland, and one of its three national saints along with Patrick and Columba. According to medieval Irish hagiogr ...

and St. Columba

Columba or Colmcille; gd, Calum Cille; gv, Colum Keeilley; non, Kolban or at least partly reinterpreted as (7 December 521 ŌĆō 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is toda ...

.

This willingness to learn, and also to teach, was a hallmark of the "permeable monasticism" that so characterised the Irish monastery. While a hermitage was still the highest form of dedication, the monasteries were very open to allowing students and children within the walls for an education, without requiring them to become monks. These students were then allowed to leave and live within the community, and were welcomed back in their old age to retire in peace. This style of monasticism allowed for the monastery to connect with, and become a part of, the community at large. The availability of the monks to the people was instrumental in converting Ireland from paganism to Christianity, allowing a blend of the two cultures.

Wales

According to hagiographies written some centuries later, Illtud and his pupils Saint David, Gildas, and Deiniol were leading figures in 6th-century Britain. Not far from Llantwit Fawr stood Cadoc's foundation ofLlancarfan

Llancarfan is a rural village and community in the Vale of Glamorgan, Wales. The village, located west of Barry and near Cowbridge, has a well-known parish church, the site of Saint Cadoc's 6th-century clas, famed for its learning. Cainnech of A ...

, founded in the latter part of the fifth century. The son of Gwynllyw, a prince of South Wales, who before his death renounced the world to lead an eremitical life, Cadoc followed his father's example and received the religious habit from St. Tathai, an Irish monk, superior of a small community at Swent near Chepstow, in Monmouthshire. Returning to his native county, Cadoc built a church and monastery, which was called Llancarfan, or the "Church of the Stags". Here he established a monastery, college and hospital. The spot at first seemed an impossible one, and an almost inaccessible marsh, but he and his monks drained and cultivated it, transforming it into one of the most famous religious houses in South Wales. His legend recounts that he daily fed a hundred clergy and a hundred soldiers, a hundred workmen, a hundred poor men, and the same number of widows. When thousands left the world and became monks, they very often did so as clansmen, dutifully following the example of their chief. Bishoprics, canonries, and parochial benefices passed from one to another member of the same family, and frequently from father to son. Their tribal character is a feature which Irish and Welsh monasteries had in common.

Illtud, said to have been an Armorican by descent, spent the first period of his religious life as a disciple of St. Cadoc at Llancarvan. He founded the monastery at Llantwit Major. The monastery stressed learning as well as devotion. One of his fellow students was Paul Aurelian

Paul Aurelian (known in Breton as Paol Aorelian or Saint Pol de L├®on and in Latin as Paulinus Aurelianus) was a 6th-century Welshman who became first bishop of the See of L├®on and one of the seven founder saints of Brittany. He allegedly died ...

, a key figure in Cornish monasticism. Gildas the Wise was invited by Cadoc to deliver lectures in the monastery and spent a year there, during which he made a copy of a book of the Gospels, long treasured in the church of St. Cadoc. One of the most notable pupils of Illtyd was St. Samson of Dol, who lived for a time the life of a hermit in a cave near the river Severn before founding a monastery in Brittany.

St David established his monastery on a promontory on the western sea. It was well placed to be a centre of Insular Christianity. When Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great (alt. ├ålfred 848/849 ŌĆō 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King ├åthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who bot ...

sought a scholar for his court, he summoned Asser of Saint David's. Contemporary with David were Saint Teilo

Saint Teilo ( la, Teliarus or '; br, TeliauWainewright, John. in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'', Vol. XIV. Robert Appleton Co. (New York), 1912. Accessed 20 July 2013. or '; french: T├®lo or '; – 9 February ), also known by his ...

, Cadoc, Padarn, Beuno

Saint Beuno ( la, Bonus;Baring-Gould &

Fisher, "Lives of the British Saints" (1907), quoted a Early British Kingdoms website by David Nash Ford, accessed 6 February 2012 640), sometimes anglicized as Bono, was a 7th-century Welsh abbot, ...

and Tysilio among them. It was from Illtud and his successors that the Irish sought guidance on matters of ritual and discipline. Finnian of Clonard studied under Cadoc at Llancarfan in Glamorgan

, HQ = Cardiff

, Government = Glamorgan County Council (1889ŌĆō1974)

, Origin=

, Code = GLA

, CodeName = Chapman code

, Replace =

* West Glamorgan

* Mid Glamorgan

* South Glamorgan

, Motto ...

.

Ireland

Finnian of Clonard is said to have trained theTwelve Apostles of Ireland

The Twelve Apostles of Ireland (also known as Twelve Apostles of Erin, ir, Dh├Ī Aspal D├®ag na h├ēireann) were twelve early Irish monastic saints of the sixth century who studied under St Finnian (d. 549) at his famous monastic school Clonar ...

at Clonard Abbey.

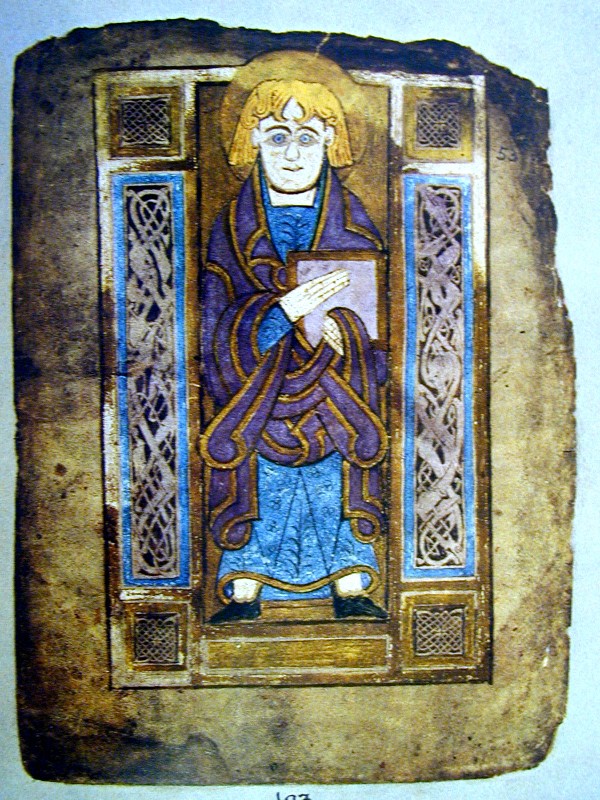

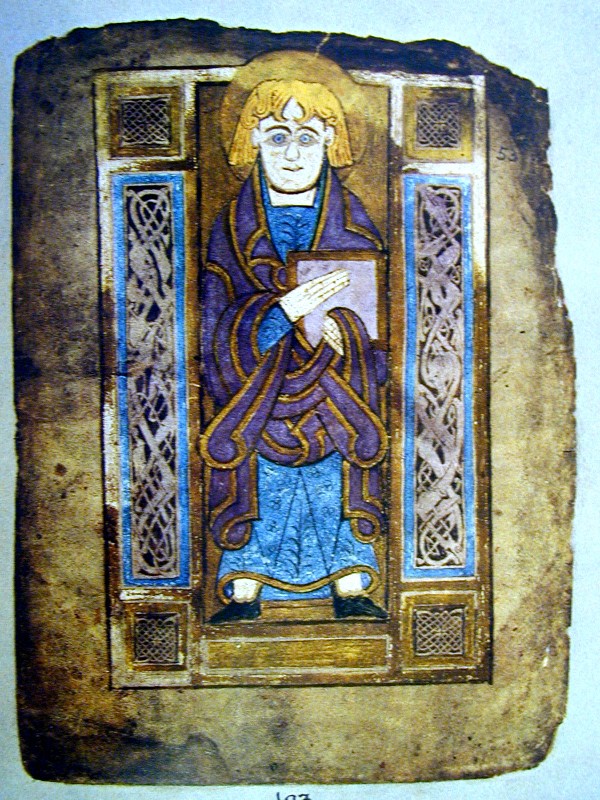

The achievements of

The achievements of insular art

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from ''insula'', the Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland shared a largely common style dif ...

, in illuminated manuscript

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is often supplemented with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers, liturgical services and psalms, the ...

s like the Book of Kells

The Book of Kells ( la, Codex Cenannensis; ga, Leabhar Cheanannais; Dublin, Trinity College Library, MS A. I. 8 sometimes known as the Book of Columba) is an illuminated manuscript Gospel book in Latin, containing the four Gospels of the New ...

, high cross

A high cross or standing cross ( ga, cros ard / ardchros, gd, crois ├Ārd / ├Ārd-chrois, cy, croes uchel / croes eglwysig) is a free-standing Christian cross made of stone and often richly decorated. There was a unique Early Medieval traditi ...

es, and metalwork like the Ardagh Chalice remain very well known, and in the case of manuscript decoration had a profound influence on Western medieval art. The manuscripts were certainly produced by and for monasteries, and the evidence suggests that metalwork was produced in both monastic and royal workshops, perhaps as well as secular commercial ones.

In the 6th and 7th centuries, Irish monks established monastic institutions in parts of modern-day Scotland (especially Columba, also known as ''Colmcille'' or, in Old Irish, ''Colum Cille''), and on the continent, particularly in Gaul (especially Columbanus). Monks from Iona Abbey under St. Aidan

Aidan of Lindisfarne ( ga, Naomh Aodh├Īn; died 31 August 651) was an Irish monk and missionary credited with converting the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity in Northumbria. He founded a monastic cathedral on the island of Lindisfarne, known as Lindis ...

founded the See of Lindisfarne in Anglo-Saxon Northumbria in 635, whence Gaelic-Irish practice heavily influenced northern England.

Irish monks also founded monasteries across the continent, exerting influence greater than many more ancient continental centres. The first issuance of a papal privilege granting a monastery freedom from episcopal oversight was that of Pope Honorius I to Bobbio Abbey, one of Columbanus's institutions.

At least in Ireland, the monastic system became increasingly secularised from the 8th century, as close ties between ruling families and monasteries became apparent. The major monasteries were now wealthy in land and had political importance. On occasion they made war either upon each other or took part in secular wars ŌĆō a battle in 764 is supposed to have killed 200 from Durrow Abbey when they were defeated by Clonmacnoise. From early periods the kin nature of many monasteries had meant that some married men were part of the community, supplying labour and with some rights, including in the election of abbots (but obliged to abstain from sex during fasting periods). Some abbacies passed from father to son, and then even grandsons. A revival of the ascetic

Asceticism (; from the el, ß╝äŽā╬║╬ĘŽā╬╣Žé, ├Īskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

tradition came in the second half of the century, with the culdee or "clients ( vassals) of God" movement founding new monasteries detached from family groupings.

Rule of Columbanus

The monasteries of the Irish missions, and many at home, adopted the Rule of Saint Columbanus, which was stricter than theRule of Saint Benedict

The ''Rule of Saint Benedict'' ( la, Regula Sancti Benedicti) is a book of precepts written in Latin in 516 by St Benedict of Nursia ( AD 480ŌĆō550) for monks living communally under the authority of an abbot.

The spirit of Saint Benedict's Ru ...

, the main alternative in the West. In particular there was more fasting and an emphasis on corporal punishment. For some generations monks trained by Irish missionaries continued to use the Rule and to found new monasteries using it, but most converted to the Benedictine Rule over the 8th and 9th centuries.

Baptism

Bede implies that in the time of Augustine of Canterbury, British churches used a baptismal rite that was in some way at variance with the Roman practice. According to Bede, the British Christians' failure to "complete" the sacrament of baptism was one of the three specific issues with British practice that Augustine could not overlook. There is no indication as to how the baptism was "incomplete" according to the Roman custom. It may be that there was some difference in theconfirmation

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. For adults, it is an affirmation of belief. It involves laying on ...

rite, or that there was no confirmation at all. At any rate, it is unlikely to have caused as much discord as the Easter controversy or the tonsure, as no other source mentions it. As such there is no evidence that heterodox baptism figured into the practice of the Irish church.

Accusations of Judaizing

A recurrent accusation levelled against the Irish throughout the Middle Ages is that they were Judaizers, which is to say that they observed certain religious rites after the manner of the Jews. The belief that Irish Christians were Judaizers can be observed in three main areas: the Easter Controversy, the notion that the Irish practised obsolete laws from theOld Testament