Charles James Fox on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled ''

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled ''

Given ''carte blanche'' to choose his own education, Fox in 1758 attended a fashionable

Given ''carte blanche'' to choose his own education, Fox in 1758 attended a fashionable

The Fox-North Coalition came to power on 2 April 1783, in spite of the King's resistance. It was the first time that George had been allowed no role in determining who should hold government office. On one occasion, Fox, who returned enthusiastically to the post of Foreign Secretary, ended an epistle to the King: "Whenever Your Majesty will be graciously pleased to condescend even to hint your inclinations upon any subject, that it will be the study of Your Majesty's Ministers to show how truly sensible they are of Your Majesty's goodness." The King replied: "No answer." George III seriously thought of abdicating at this time, after the comprehensive defeat of his American policy and the imposition of Fox and North, but refrained from doing so, mainly because of the thought of his succession by his son George, Prince of Wales, the notoriously extravagant womaniser, gambler and associate of Fox. Indeed, in many ways the King considered Fox his son's tutor in debauchery. "George III let it be widely broadcast that he held Fox principally responsible for the Prince's many failings, not least a tendency to vomit in public."

The Fox-North Coalition came to power on 2 April 1783, in spite of the King's resistance. It was the first time that George had been allowed no role in determining who should hold government office. On one occasion, Fox, who returned enthusiastically to the post of Foreign Secretary, ended an epistle to the King: "Whenever Your Majesty will be graciously pleased to condescend even to hint your inclinations upon any subject, that it will be the study of Your Majesty's Ministers to show how truly sensible they are of Your Majesty's goodness." The King replied: "No answer." George III seriously thought of abdicating at this time, after the comprehensive defeat of his American policy and the imposition of Fox and North, but refrained from doing so, mainly because of the thought of his succession by his son George, Prince of Wales, the notoriously extravagant womaniser, gambler and associate of Fox. Indeed, in many ways the King considered Fox his son's tutor in debauchery. "George III let it be widely broadcast that he held Fox principally responsible for the Prince's many failings, not least a tendency to vomit in public."

Happily for George, the unpopular coalition would not outlast the year. The

Happily for George, the unpopular coalition would not outlast the year. The

One of Pitt's first major actions as prime minister was, in 1785, to put a scheme of parliamentary reform before the Commons, proposing to rationalise somewhat the existing, decidedly unrepresentative, electoral system by eliminating thirty-six rotten boroughs and redistributing seats to represent London and the larger counties. Fox supported Pitt's reforms, despite apparent political expediency, but they were defeated by 248 to 174. Reform would not be considered seriously by Parliament for another decade.

In 1787, the most dramatic political event of the decade came to pass in the form of the

One of Pitt's first major actions as prime minister was, in 1785, to put a scheme of parliamentary reform before the Commons, proposing to rationalise somewhat the existing, decidedly unrepresentative, electoral system by eliminating thirty-six rotten boroughs and redistributing seats to represent London and the larger counties. Fox supported Pitt's reforms, despite apparent political expediency, but they were defeated by 248 to 174. Reform would not be considered seriously by Parliament for another decade.

In 1787, the most dramatic political event of the decade came to pass in the form of the

In late October 1788, George III descended into a bout of mental illness. He had declared that Pitt was "a rascal" and Fox "his Friend". The King was placed under restraint, and a rumour went round that Fox had poisoned him. Thus the opportunity revealed itself for the establishment of a regency under Fox's friend and ally, the

In late October 1788, George III descended into a bout of mental illness. He had declared that Pitt was "a rascal" and Fox "his Friend". The King was placed under restraint, and a rumour went round that Fox had poisoned him. Thus the opportunity revealed itself for the establishment of a regency under Fox's friend and ally, the

Fox welcomed the

Fox welcomed the  On the world stage of 1791, war with Great Britain was threatened more with Spain and

On the world stage of 1791, war with Great Britain was threatened more with Spain and  On 6 May 1791, a tearful confrontation on the floor of the Commons finally shattered the quarter-century friendship of Fox and Burke, as the latter dramatically crossed the floor of the House to sit down next to Pitt, taking the support of a good deal of the more conservative Whigs with him. Officially, and rather irrelevantly, this happened during a debate on the particulars of a bill for the government of

On 6 May 1791, a tearful confrontation on the floor of the Commons finally shattered the quarter-century friendship of Fox and Burke, as the latter dramatically crossed the floor of the House to sit down next to Pitt, taking the support of a good deal of the more conservative Whigs with him. Officially, and rather irrelevantly, this happened during a debate on the particulars of a bill for the government of

Fox continued to defend the French Revolution, even as its fruits began to collapse into war, repression and the Reign of Terror. Though there were few developments in France after 1792 that Fox could positively favour, Fox maintained that the old monarchical system still proved a greater threat to liberty than the new, degenerating experiment in France. Fox thought of revolutionary France as the lesser of two evils and emphasised the role of traditional despots in perverting the course of the revolution: he argued that

Fox continued to defend the French Revolution, even as its fruits began to collapse into war, repression and the Reign of Terror. Though there were few developments in France after 1792 that Fox could positively favour, Fox maintained that the old monarchical system still proved a greater threat to liberty than the new, degenerating experiment in France. Fox thought of revolutionary France as the lesser of two evils and emphasised the role of traditional despots in perverting the course of the revolution: he argued that  Parliament passed the acts. But Fox enjoyed a swell of extra-parliamentary support during the course of the controversy. A substantial petitioning movement arose in support of him, and on 16 November 1795, he addressed a public meeting of between two- and thirty-thousand people on the subject. However, this came to nothing in the long run. The Foxites were becoming disenchanted with the Commons, overwhelmingly dominated by Pitt, and began to denounce it to one another as unrepresentative.

Parliament passed the acts. But Fox enjoyed a swell of extra-parliamentary support during the course of the controversy. A substantial petitioning movement arose in support of him, and on 16 November 1795, he addressed a public meeting of between two- and thirty-thousand people on the subject. However, this came to nothing in the long run. The Foxites were becoming disenchanted with the Commons, overwhelmingly dominated by Pitt, and began to denounce it to one another as unrepresentative.

By May 1797, an overwhelming majority – both in and outside of Parliament – had formed in support of Pitt's war against France.

Fox's following in Parliament had shrivelled to about 25, compared with around 55 in 1794 and at least 90 during the 1780s. Many of the Foxites purposefully seceded from Parliament in 1797; Fox himself retired for lengthy periods to his wife's house in Surrey. The distance from the stress and noise of Westminster was an enormous psychological and spiritual relief to Fox, but still he defended his earlier principles: "It is a great comfort to me to reflect how steadily I have opposed this war, for the miseries it seems likely to produce are without end."

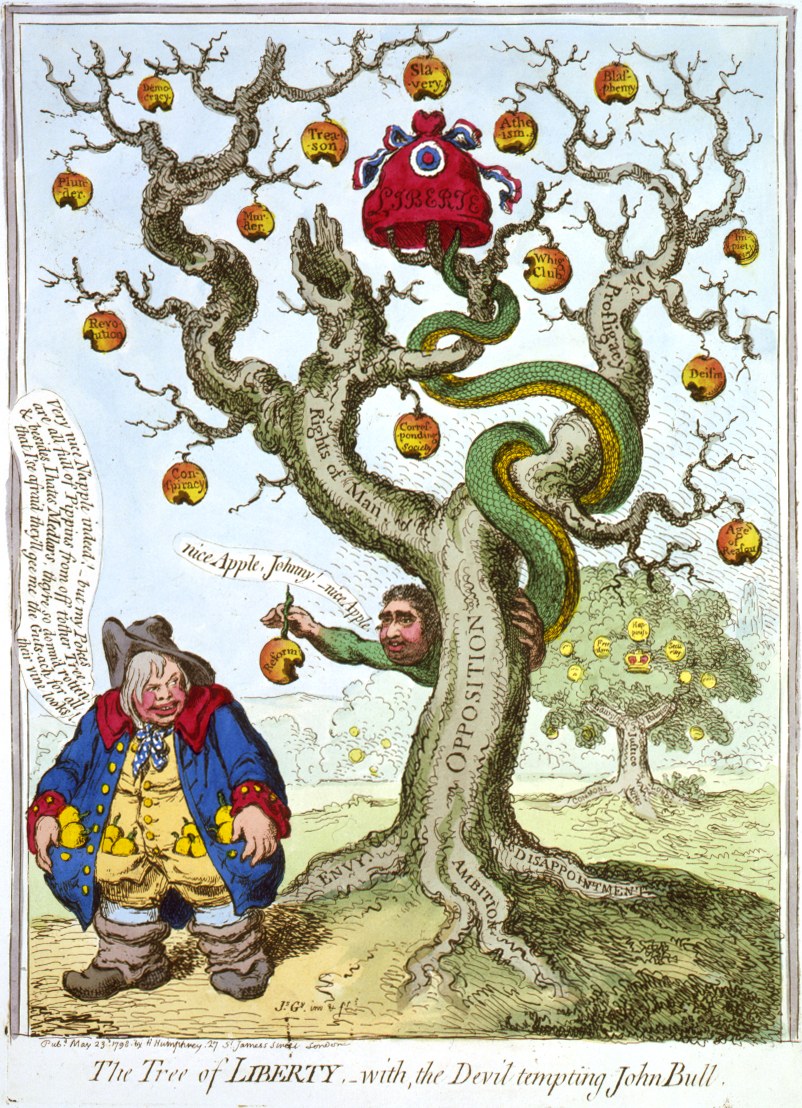

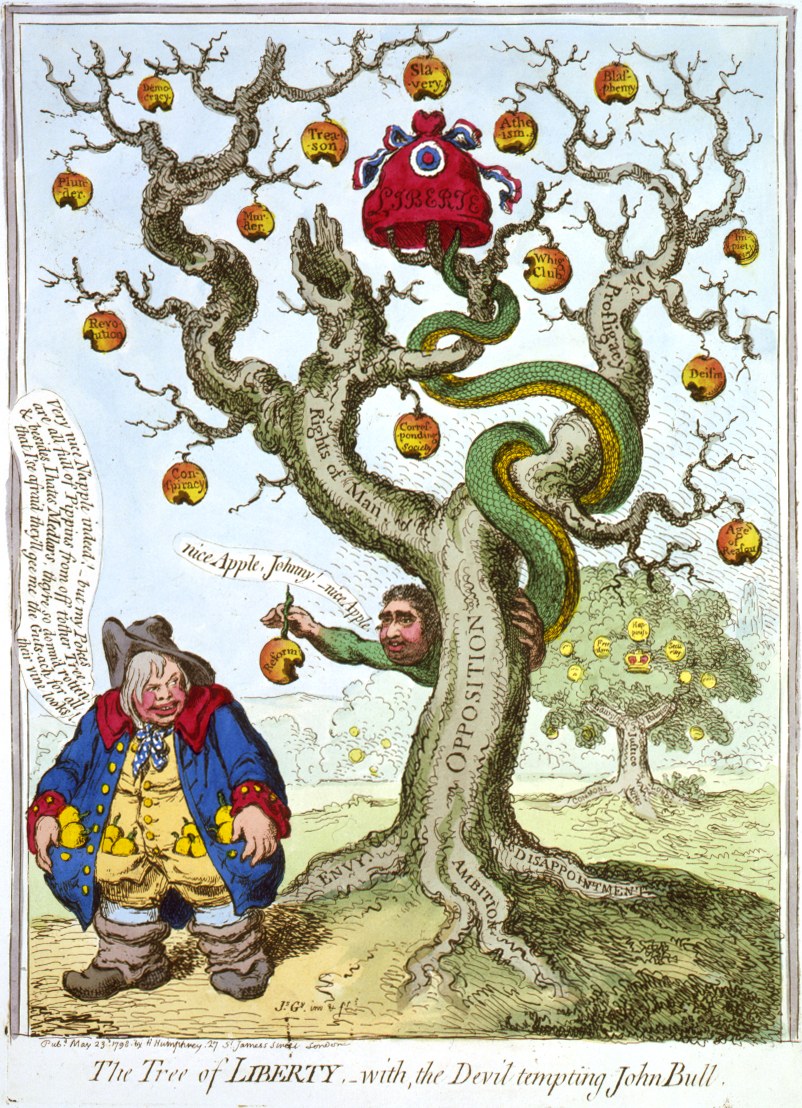

On 1 May 1798, Fox proposed a toast to "Our Sovereign, the Majesty of the People". The

By May 1797, an overwhelming majority – both in and outside of Parliament – had formed in support of Pitt's war against France.

Fox's following in Parliament had shrivelled to about 25, compared with around 55 in 1794 and at least 90 during the 1780s. Many of the Foxites purposefully seceded from Parliament in 1797; Fox himself retired for lengthy periods to his wife's house in Surrey. The distance from the stress and noise of Westminster was an enormous psychological and spiritual relief to Fox, but still he defended his earlier principles: "It is a great comfort to me to reflect how steadily I have opposed this war, for the miseries it seems likely to produce are without end."

On 1 May 1798, Fox proposed a toast to "Our Sovereign, the Majesty of the People". The

When Pitt died on 23 January 1806, Fox was the last remaining great political figure of the era and could no longer be denied a place in government. When Grenville formed a " Ministry of All the Talents" out of his supporters, the followers of Addington and the Foxites, Fox was once again offered the post of Foreign Secretary, which he accepted in February. Fox was convinced (as he had been since Napoleon's accession) that France desired a lasting peace and that he was "sure that two civil sentences from the Ministers would ensure Peace". Therefore, peace talks were speedily entered into by Fox and his old friend Talleyrand, now French foreign minister. The mood had completely changed by July, however, and Fox was forced to acknowledge that his assessment of Napoleon's pacific intentions was wrong. Negotiations over Hanover, Naples, Sicily, and Malta faltered and Talleyrand vetoed Russian participation in the negotiations. King George believed this was a ploy to divide Britain and Russia as French interests would suffer if she had to deal with an Anglo-Russian alliance. Fox was forced to agree that the King's belief was "but too well founded".

In June, Lord Yarmouth was sent on a peace mission to Paris. Fox wrote to him: "I feel my own Glory highly interested in such an event, but to make peace by acceding to worse terms than those first suggested...wd. be as repugnant to my own feelings as it wd. be to the Duty I owe to K. & Country". Yarmouth confirmed that Russia was negotiating separately with France. Fox was appalled at what he called this "extraordinary step". When Yarmouth reported successive new French demands, Fox replied that the British government "continues ardently to wish for the Conclusion of Peace". In August, Lord Lauderdale was sent to join Yarmouth (with full negotiating powers), and he reported back to Fox of "the complete system of Terror which prevails here". Fox's French friends were too frightened to call on him.

When Pitt died on 23 January 1806, Fox was the last remaining great political figure of the era and could no longer be denied a place in government. When Grenville formed a " Ministry of All the Talents" out of his supporters, the followers of Addington and the Foxites, Fox was once again offered the post of Foreign Secretary, which he accepted in February. Fox was convinced (as he had been since Napoleon's accession) that France desired a lasting peace and that he was "sure that two civil sentences from the Ministers would ensure Peace". Therefore, peace talks were speedily entered into by Fox and his old friend Talleyrand, now French foreign minister. The mood had completely changed by July, however, and Fox was forced to acknowledge that his assessment of Napoleon's pacific intentions was wrong. Negotiations over Hanover, Naples, Sicily, and Malta faltered and Talleyrand vetoed Russian participation in the negotiations. King George believed this was a ploy to divide Britain and Russia as French interests would suffer if she had to deal with an Anglo-Russian alliance. Fox was forced to agree that the King's belief was "but too well founded".

In June, Lord Yarmouth was sent on a peace mission to Paris. Fox wrote to him: "I feel my own Glory highly interested in such an event, but to make peace by acceding to worse terms than those first suggested...wd. be as repugnant to my own feelings as it wd. be to the Duty I owe to K. & Country". Yarmouth confirmed that Russia was negotiating separately with France. Fox was appalled at what he called this "extraordinary step". When Yarmouth reported successive new French demands, Fox replied that the British government "continues ardently to wish for the Conclusion of Peace". In August, Lord Lauderdale was sent to join Yarmouth (with full negotiating powers), and he reported back to Fox of "the complete system of Terror which prevails here". Fox's French friends were too frightened to call on him.

Fox's biographer notes that these failed negotiations were "a stunning experience" for Fox, who had always insisted that France desired peace and that the war was the responsibility of King George and his fellow monarchs: "All of this was being proved false...It was a tragic end to Fox's career". To observers such as John Rickman, "Charley Fox eats his former opinions daily and even ostentatiously showing himself the worse man, but the better minister of a corrupt government", and who further claimed that "He should have died, for his fame, a little sooner; before Pitt".

Though the administration failed to achieve either Catholic emancipation or peace with France, Fox's last great achievement would be the

Fox's biographer notes that these failed negotiations were "a stunning experience" for Fox, who had always insisted that France desired peace and that the war was the responsibility of King George and his fellow monarchs: "All of this was being proved false...It was a tragic end to Fox's career". To observers such as John Rickman, "Charley Fox eats his former opinions daily and even ostentatiously showing himself the worse man, but the better minister of a corrupt government", and who further claimed that "He should have died, for his fame, a little sooner; before Pitt".

Though the administration failed to achieve either Catholic emancipation or peace with France, Fox's last great achievement would be the

Fox died – still in office – at

Fox died – still in office – at

Fox's private life (as far as it was private) was notorious, even in an age noted for the licentiousness of its upper classes. Fox was famed for his rakishness and his drinking; vices which were both indulged frequently and immoderately. Fox was also an inveterate gambler, once claiming that winning was the greatest pleasure in the world, and losing the second greatest. Between 1772 and 1774, Fox's fathershortly before dyinghad to pay off £120,000 of Charles' debts; the equivalent of around £ million in . Fox was twice bankrupted between 1781 and 1784, and at one point his creditors confiscated his furniture. Fox's finances were often "more the subject of conversation than any other topic." By the end of his life, Fox had lost about £200,000 gambling.

In appearance, Fox was dark, corpulent and hairy, to the extent that when he was born his father compared him to a monkey. His round face was dominated by his luxuriant eyebrows, with the result that he was known among fellow Whigs as 'the Eyebrow.' Though he became increasingly dishevelled and fat in middle age, the young Fox had been very fashionable; he had been the leader of the 'Maccaroni' set of extravagant young followers of Continental fashions. Fox liked riding horses and watching and playing

Fox's private life (as far as it was private) was notorious, even in an age noted for the licentiousness of its upper classes. Fox was famed for his rakishness and his drinking; vices which were both indulged frequently and immoderately. Fox was also an inveterate gambler, once claiming that winning was the greatest pleasure in the world, and losing the second greatest. Between 1772 and 1774, Fox's fathershortly before dyinghad to pay off £120,000 of Charles' debts; the equivalent of around £ million in . Fox was twice bankrupted between 1781 and 1784, and at one point his creditors confiscated his furniture. Fox's finances were often "more the subject of conversation than any other topic." By the end of his life, Fox had lost about £200,000 gambling.

In appearance, Fox was dark, corpulent and hairy, to the extent that when he was born his father compared him to a monkey. His round face was dominated by his luxuriant eyebrows, with the result that he was known among fellow Whigs as 'the Eyebrow.' Though he became increasingly dishevelled and fat in middle age, the young Fox had been very fashionable; he had been the leader of the 'Maccaroni' set of extravagant young followers of Continental fashions. Fox liked riding horses and watching and playing

In the 19th century, liberals portrayed Fox as their hero, praising his courage, perseverance and eloquence. They celebrated his opposition to war in alliance with European despots against the people of France eager for their freedom, and they praised his fight for

In the 19th century, liberals portrayed Fox as their hero, praising his courage, perseverance and eloquence. They celebrated his opposition to war in alliance with European despots against the people of France eager for their freedom, and they praised his fight for  The town of Foxborough, Massachusetts, was named in honour of the staunch supporter of

The town of Foxborough, Massachusetts, was named in honour of the staunch supporter of

mini series ''

online free to borrow

* * * *

online free to borrow

* * *

on Fox as the 200th anniversary of his death approaches

BBC article

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fox, Charles James 1749 births 1806 deaths Alumni of Hertford College, Oxford Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for Scottish constituencies British radicals British MPs 1768–1774 British MPs 1774–1780 British MPs 1780–1784 British MPs 1784–1790 British MPs 1790–1796 British MPs 1796–1800 British Secretaries of State for Foreign Affairs Burials at Westminster Abbey British duellists English abolitionists Lords of the Admiralty Members of the Privy Council of Great Britain Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies People educated at Eton College Radicalism (historical) UK MPs 1801–1802 UK MPs 1802–1806 Younger sons of barons Leaders of the House of Commons of Great Britain Leaders of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled ''

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled ''The Honourable

''The Honourable'' (British English) or ''The Honorable'' ( American English; see spelling differences) (abbreviation: ''Hon.'', ''Hon'ble'', or variations) is an honorific style that is used as a prefix before the names or titles of certain ...

'' from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was the arch-rival of the Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

politician William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ire ...

; his father Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland

Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland, PC (28 September 1705 – 1 July 1774), of Holland House in Kensington and of Holland House in Kingsgate, Kent, was a leading British politician. He identified primarily with the Whig faction. He held the post ...

, a leading Whig of his day, had similarly been the great rival of Pitt's famous father, William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British statesman of the Whig group who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him Chatham or William Pitt the Elder to distinguish ...

("Pitt the Elder").

Fox rose to prominence in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

as a forceful and eloquent speaker with a notorious and colourful private life, though at that time with rather conservative and conventional opinions. However, with the coming of the American War of Independence and the influence of the Whig Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

, Fox's opinions evolved into some of the most radical to be aired in the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

of his era.

Fox became a prominent and staunch opponent of King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, whom he regarded as an aspiring tyrant. He supported the American Patriots

Patriots, also known as Revolutionaries, Continentals, Rebels, or American Whigs, were the colonists of the Thirteen Colonies who rejected British rule during the American Revolution, and declared the United States of America an independent n ...

and even dressed in the colours of George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

's army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

. Briefly serving as Britain's first Foreign Secretary during the ministry of the Marquess of Rockingham

Marquess of Rockingham, in the County of Northampton, was a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1746 for Thomas Watson-Wentworth, 1st Earl of Malton. The Watson family descended from Lewis Watson, Member of Parliament f ...

in 1782, he returned to the post in a coalition government with his old enemy, Lord North

Frederick North, 2nd Earl of Guilford (13 April 17325 August 1792), better known by his courtesy title Lord North, which he used from 1752 to 1790, was 12th Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1770 to 1782. He led Great Britain through most o ...

, in 1783. However, the King forced Fox and North out of government before the end of the year and replaced them with the 24-year-old Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ire ...

. Fox spent the following 22 years facing Pitt and the government from the opposition benches of the House of Commons.

Though Fox had little interest in the actual exercise of power and spent almost the entirety of his political career in opposition, he became noted as an anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

campaigner, a supporter of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

and a leading parliamentary advocate of religious tolerance and individual liberty. His friendship with his mentor, Burke, and his parliamentary credibility were both casualties of Fox's support for France during the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Prussia ...

, but Fox went on to attack Pitt's wartime legislation and to defend the liberty of religious minorities and political radicals. After Pitt's death in January 1806, Fox served briefly as Foreign Secretary in the ' Ministry of All the Talents' of William Grenville before he died on 13 September 1806, aged 57.

Early life: 1749–1758

Fox was born at 9Conduit Street

Conduit Street is a street in Mayfair, London. It connects Bond Street to Regent Street.

History

The street was first developed in the early 18th century on the Conduit Mead Estate, which the Corporation of London had owned since the 15th centu ...

, London, the second surviving son of Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland

Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland, PC (28 September 1705 – 1 July 1774), of Holland House in Kensington and of Holland House in Kingsgate, Kent, was a leading British politician. He identified primarily with the Whig faction. He held the post ...

, and Lady Caroline Lennox, a daughter of Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond

Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond, 2nd Duke of Lennox, 2nd Duke of Aubigny, (18 May 17018 August 1750) of Goodwood House near Chichester in Sussex, was a British nobleman and politician. He was the son of Charles Lennox, 1st Duke of Richmo ...

. Henry Fox (1705–1774) was an ally of Robert Walpole and rival of Pitt the Elder

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British statesman of the Whig group who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him Chatham or William Pitt the Elder to distinguish ...

, and had amassed a considerable fortune by exploiting his position as Paymaster General of the forces

The Paymaster of the Forces was a position in the British government. The office was established in 1661, one year after the Restoration of the Monarchy to King Charles II, and was responsible for part of the financing of the British Army, in ...

. Charles James Fox's elder brother Stephen

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

(1745–1774) became the 2nd Baron Holland, and his younger brother Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

(1755–1811) had a distinguished military career.

Fox was the darling of his father, who found Charles "infinitely engaging & clever & pretty" and, from the time that his son was three years old, apparently preferred his company at meals to that of anyone else. The stories of Charles's over-indulgence by his doting father are legendary. It was said that Charles once expressed a great desire to break his father's watch and was not restrained or punished when he duly smashed it on the floor. On another occasion, when Henry had promised his son that he could watch the demolition of a wall on his estate and found that it had already been destroyed, he ordered the workmen to rebuild the wall and demolish it again, with Charles watching.

Given ''carte blanche'' to choose his own education, Fox in 1758 attended a fashionable

Given ''carte blanche'' to choose his own education, Fox in 1758 attended a fashionable Wandsworth

Wandsworth Town () is a district of south London, within the London Borough of Wandsworth southwest of Charing Cross. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

Toponymy

Wandsworth takes its nam ...

school run by a Monsieur Pampellonne, followed by Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, ...

, where he began to develop his lifelong love of classical literature. In later life he was said to have always carried a copy of Horace in his coat pocket. He was taken out of school by his father in 1761 to attend the coronation of George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, who would become one of his most bitter enemies, and once more in 1763 to travel to the Continent (where he visited Paris and Spa). On this trip Charles was given a substantial amount of money with which to learn to gamble by his father, who also arranged for him to lose his virginity, aged fourteen, to a Madame de Quallens. Fox returned to Eton later that year, "attired in red-heeled shoes and Paris cut-velvet, adorned with a pigeon-wing hair style tinted with blue powder, and a newly acquired French accent", and was duly flogged by Dr. Barnard, the headmaster. Charles Fox was once known as a macaroni, despite him being a tad too overweight to look decent in his tight clothing. These three pursuits – gambling, womanising and the love of things and fashions foreign – would become, once inculcated in his adolescence, notorious habits of Fox's later life.

Fox entered Hertford College, Oxford, in October 1764, but left without graduating, being rather contemptuous of its "nonsenses". He went on several further expeditions to Europe, becoming well known in the great Parisian salons, meeting influential figures such as Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

, Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and member of parliament. His most important work, '' The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, is ...

, the duc d'Orléans and the Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

, and becoming the co-owner of a number of racehorses with the duc de Lauzun.

Early career: 1768–1774

Member of Parliament

For the 1768 general election, Henry Fox bought his son a seat in Parliament for theWest Sussex

West Sussex is a county in South East England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the shire districts of Adur, Arun, Chichester, Horsham, and Mid Sussex, and the boroughs of Crawley and Worthing. Covering an ...

constituency of Midhurst

Midhurst () is a market town, parish and civil parish in West Sussex, England. It lies on the River Rother inland from the English Channel, and north of the county town of Chichester.

The name Midhurst was first recorded in 1186 as ''Middeh ...

, though Charles was still nineteen and technically ineligible for Parliament. Fox was to address the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

some 254 times between 1768 and 1774 and rapidly gathered a reputation as a superb orator, but he had not yet developed the radical opinions for which he would become famous. Thus, he spent much of his early years unwittingly manufacturing ammunition for his later critics and their accusations of hypocrisy. A supporter of the Grafton and North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

ministries, Fox was prominent in the campaign to punish the radical John Wilkes for challenging the Commons. "He thus opened his career by speaking in behalf of the Commons against the people and their elected representative." Consequently, both Fox and his brother Stephen were insulted and pelted with mud in the street by the pro-Wilkes London crowds.

Between 1770 and 1774, Fox's seemingly promising career in the political establishment was spoiled. He was appointed to the Board of Admiralty by Lord North in February 1770, but on the 15th of the same month, he resigned due to his enthusiastic opposition to the government's Royal Marriages Act

The Royal Marriages Act 1772 (12 Geo 3 c. 11) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which prescribed the conditions under which members of the British royal family could contract a valid marriage, in order to guard against marriages th ...

, the provisions of which – incidentally – cast doubt on the legitimacy of his parents' marriage. On 28 December 1772, North appointed him to the board of the Treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or i ...

; in February 1774, Fox again surrendered his post, this time over the Government's allegedly feeble response to the contemptuous printing and public distribution of copies of parliamentary debates. Behind these incidents lay his family's resentment towards Lord North for refusing to elevate the Holland barony to an earldom

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant " chieftain", particula ...

. But the fact that such a young man could seemingly treat ministerial office so lightly was noted at court

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in acco ...

. George III, also observing Fox's licentious private behaviour, took it to be presumption and judged that Fox could not be trusted to take anything seriously.

After 1774, Fox began to reconsider his political position under the influence of Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

– who had sought out the promising young Whig and would become his mentor – and the unfolding events in America. He drifted from his rather unideological family-oriented politics into the orbit of the Rockingham Whig party.

During this period, Fox became possibly the most prominent and vituperative parliamentary critic of Lord North and the conduct of the American War. In 1775, he denounced North in the Commons as

American Revolution

Fox, who occasionally corresponded withThomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

and had met Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

in Paris, correctly predicted that Britain had little practical hope of subduing the colonies and interpreted the American cause approvingly as a struggle for liberty against the oppressive policies of a despotic and unaccountable executive. It was at this time that Fox and his supporters took up the habit of dressing in buff and blue, the colours of the uniforms in Washington's army. Fox's friend, the Earl of Carlisle

Earl of Carlisle is a title that has been created three times in the Peerage of England.

History

The first creation came in 1322, when Andrew Harclay, 1st Baron Harclay, was made Earl of Carlisle. He had already been summoned to Parliamen ...

, observed that any setback for the British Government in America was "a great cause of amusement to Charles." Even after the American defeat at Long Island in 1776, Fox stated that

On 31 October the same year, Fox responded to the King's address to Parliament with "one of his finest and most animated orations, and with severity to the answered person", so much so that, when he sat down, no member of the Government would attempt to reply.

Crucial to any understanding of Fox's political career from this point was his mutual antipathy with George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

– probably the most enthusiastic prosecutor of the American War. Fox became convinced that the King was determined to challenge the authority of Parliament and the balance of the constitution established in 1688, and to achieve Continental-style tyranny. George in return thought that Fox had "cast off every principle of common honour and honesty ... man who isas contemptible as he is odious ... nd has anaversion to all restraints." It is difficult to find two political figures in British history more greatly contrasted in temperament than Fox and George: the former a notorious gambler and rake; the latter famous for his virtues of frugality and family. On 6 April 1780, John Dunning's motion that "The influence of the Crown has increased, is increasing, and ought to be diminished" passed the Commons by a vote of 233 to 215. Fox thought it "glorious", saying on 24 April that

Fox, however, had not been present in the House for the beginning of the Dunning debate, as he had been occupied in the adjoining eleventh-century Westminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north bank ...

, serving as chairman of a mass public meeting before a large banner that read "Annual Parliaments and Equal Representation". This was the period when Fox, hardening against the influence of the Crown, was embraced by the radical movement of the late eighteenth century. When the shocking Gordon riots exploded in London in June 1780, Fox, though deploring the violence of the crowd, declared that he would "much rather be governed by a mob than a standing army." Later, in July, Fox was returned for the populous and prestigious constituency of Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

, with around 12,000 electors, and acquired the title "Man of the People".

Late career: 1782–1797

Constitutional crisis

When North finally resigned under the strains of office and the disastrous American War in March 1782, afterEarl Cornwallis

Earl Cornwallis was a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1753 for Charles Cornwallis, 5th Baron Cornwallis. The second Earl was created Marquess Cornwallis but this title became extinct in 1823, while the earldom and its ...

surrendered at the Battle of Yorktown, and was gingerly replaced with the new ministry of the Marquess of Rockingham

Marquess of Rockingham, in the County of Northampton, was a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1746 for Thomas Watson-Wentworth, 1st Earl of Malton. The Watson family descended from Lewis Watson, Member of Parliament f ...

, Fox was appointed Foreign Secretary. But Rockingham, after finally acknowledging the independence of the former Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

, died unexpectedly on 1 July. Fox refused to serve in the successor administration of the Earl of Shelburne

Earl of Shelburne is a title that has been created two times while the title of Baron Shelburne has been created three times. The Shelburne title was created for the first time in the Peerage of Ireland in 1688 when Elizabeth, Lady Petty, was m ...

, splitting the Whig party; Fox's father had been convinced that Shelburne – a supporter of the elder Pitt – had thwarted his ministerial ambitions at the time of the Treaty of Paris in 1763. Fox now found himself in common opposition to Shelburne with his old and bitter enemy, Lord North. Based on this single conjunction of interests and the fading memory of the happy co-operation of the early 1770s, the two men who had vilified one another throughout the American war together formed a coalition and forced their Government, with an overwhelming majority composed of North's Tories and Fox's opposition Whigs, on to the King.

The Fox-North Coalition came to power on 2 April 1783, in spite of the King's resistance. It was the first time that George had been allowed no role in determining who should hold government office. On one occasion, Fox, who returned enthusiastically to the post of Foreign Secretary, ended an epistle to the King: "Whenever Your Majesty will be graciously pleased to condescend even to hint your inclinations upon any subject, that it will be the study of Your Majesty's Ministers to show how truly sensible they are of Your Majesty's goodness." The King replied: "No answer." George III seriously thought of abdicating at this time, after the comprehensive defeat of his American policy and the imposition of Fox and North, but refrained from doing so, mainly because of the thought of his succession by his son George, Prince of Wales, the notoriously extravagant womaniser, gambler and associate of Fox. Indeed, in many ways the King considered Fox his son's tutor in debauchery. "George III let it be widely broadcast that he held Fox principally responsible for the Prince's many failings, not least a tendency to vomit in public."

The Fox-North Coalition came to power on 2 April 1783, in spite of the King's resistance. It was the first time that George had been allowed no role in determining who should hold government office. On one occasion, Fox, who returned enthusiastically to the post of Foreign Secretary, ended an epistle to the King: "Whenever Your Majesty will be graciously pleased to condescend even to hint your inclinations upon any subject, that it will be the study of Your Majesty's Ministers to show how truly sensible they are of Your Majesty's goodness." The King replied: "No answer." George III seriously thought of abdicating at this time, after the comprehensive defeat of his American policy and the imposition of Fox and North, but refrained from doing so, mainly because of the thought of his succession by his son George, Prince of Wales, the notoriously extravagant womaniser, gambler and associate of Fox. Indeed, in many ways the King considered Fox his son's tutor in debauchery. "George III let it be widely broadcast that he held Fox principally responsible for the Prince's many failings, not least a tendency to vomit in public."

Happily for George, the unpopular coalition would not outlast the year. The

Happily for George, the unpopular coalition would not outlast the year. The Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

was signed on 3 September 1783, formally ending the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Fox proposed an East India Bill to place the government of the ailing and oppressive British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

, at that time in control of a considerable expanse of India, on a sounder footing with a board of governors responsible to Parliament and more resistant to Crown patronage. It passed the Commons by 153 to 80, but, when the King made it clear that any peer who voted in favour of the bill would be considered a personal enemy of the Crown, the Lords divided against Fox by 95 to 76. George now felt justified in dismissing Fox and North from government and in nominating William Pitt in their place; at twenty-four years of age, the youngest British prime minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As moder ...

in history was appointed to office, apparently on the authority of the votes of 19 peers. Fox used his parliamentary majority to oppose Pitt's nomination, and every subsequent measure that he put before the House, until March 1784, when the King dissolved Parliament and, in the following general election, Pitt was returned with a substantial majority.

In Fox's own constituency of Westminster, the contest was particularly fierce. An energetic campaign in his favour was run by Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire

Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire (née Spencer; ; 7 June 1757 – 30 March 1806), was an English aristocrat, socialite, political organiser, author, and activist. Born into the Spencer family, married into the Cavendish family, she wa ...

, allegedly a lover of Fox's who was said to have won at least one vote for him by kissing a shoemaker with a rather romantic idea of what constituted a bribe. In the end, Fox was re-elected by a very slender margin, but legal challenges (encouraged, to an extent, by Pitt and the King) prevented a final declaration of the result for over a year. In the meantime, Fox sat for the Scottish pocket borough of Tain or Northern Burghs, for which he was qualified by being made an unlikely burgess of Kirkwall

Kirkwall ( sco, Kirkwaa, gd, Bàgh na h-Eaglaise, nrn, Kirkavå) is the largest town in Orkney, an archipelago to the north of mainland Scotland.

The name Kirkwall comes from the Norse name (''Church Bay''), which later changed to ''Kirkv ...

in Orkney (which was one of the Burghs in the district

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or county, counties, several municipality, municipa ...

). The experience of these years was crucial in Fox's political formation. His suspicions had been confirmed; it seemed to him that George III had personally scuppered both the Rockingham-Shelburne and Fox-North governments, interfered in the legislative process and now dissolved Parliament when its composition inconvenienced him. Pitt – a man of little property and no party – seemed to Fox a blatant tool of the Crown. However, the King and Pitt had great popular support, and many in the press and general population saw Fox as the trouble-maker challenging the composition of the constitution and the King's remaining powers. He was often caricatured as Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three K ...

and Guy Fawkes

Guy Fawkes (; 13 April 1570 – 31 January 1606), also known as Guido Fawkes while fighting for the Spanish, was a member of a group of provincial English Catholics involved in the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He was born and educated ...

during this period, as well as Satan, "Carlo Khan" (see James Sayers) and Machiavelli.

Opposition

One of Pitt's first major actions as prime minister was, in 1785, to put a scheme of parliamentary reform before the Commons, proposing to rationalise somewhat the existing, decidedly unrepresentative, electoral system by eliminating thirty-six rotten boroughs and redistributing seats to represent London and the larger counties. Fox supported Pitt's reforms, despite apparent political expediency, but they were defeated by 248 to 174. Reform would not be considered seriously by Parliament for another decade.

In 1787, the most dramatic political event of the decade came to pass in the form of the

One of Pitt's first major actions as prime minister was, in 1785, to put a scheme of parliamentary reform before the Commons, proposing to rationalise somewhat the existing, decidedly unrepresentative, electoral system by eliminating thirty-six rotten boroughs and redistributing seats to represent London and the larger counties. Fox supported Pitt's reforms, despite apparent political expediency, but they were defeated by 248 to 174. Reform would not be considered seriously by Parliament for another decade.

In 1787, the most dramatic political event of the decade came to pass in the form of the Impeachment of Warren Hastings

The impeachment of Warren Hastings, the first governor-general of Bengal, was attempted between 1787 and 1795 in the Parliament of Great Britain. Hastings was accused of misconduct during his time in Calcutta, particularly relating to mismanageme ...

, the Governor of Bengal until 1785, on charges of corruption and extortion. Fifteen of the eighteen Managers appointed to the trial were Foxites, one of them being Fox himself. Although the matter was really Burke's area of expertise, Fox was, at first, enthusiastic. If the trial could demonstrate the misrule of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

by Hastings and the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

more widely, then Fox's India Bill of 1784 – the point on which the Fox-North Coalition had been dismissed by the King – would be vindicated. The trial was also expedient for Fox in that it placed Pitt in an uncomfortable political position. The premier was forced to equivocate over the Hastings trial, because to oppose Hastings would have been to endanger the support of the King and the East India Company, while to support him openly would have alienated country gentlemen and principled supporters like Wilberforce. As the trial's intricacies dragged on (it would be 1795 before Hastings was finally acquitted), Fox's interest waned and the burden of managing the trial devolved increasingly on Burke.

The Regency Crisis

In late October 1788, George III descended into a bout of mental illness. He had declared that Pitt was "a rascal" and Fox "his Friend". The King was placed under restraint, and a rumour went round that Fox had poisoned him. Thus the opportunity revealed itself for the establishment of a regency under Fox's friend and ally, the

In late October 1788, George III descended into a bout of mental illness. He had declared that Pitt was "a rascal" and Fox "his Friend". The King was placed under restraint, and a rumour went round that Fox had poisoned him. Thus the opportunity revealed itself for the establishment of a regency under Fox's friend and ally, the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

, which would take the reins of government out of the hands of the incapacitated George III and allow the replacement of his "minion" Pitt with a Foxite ministry.

Fox, however, was incommunicado in Italy as the crisis broke; he had resolved not to read any newspapers while he was abroad, except the racing reports. Three weeks passed before he returned to Britain on 25 November 1788, and then he was taken seriously ill (partly due to the stress of his rapid journey across Europe). He would not recover entirely until December 1789. He again absented himself to Bath from 27 January to 21 February 1789.

When Fox did make it into Parliament, he seemed to make a serious political error. In the Commons on 10 December, he declared that it was the right of the Prince of Wales to install himself as regent immediately. It is said that Pitt, upon hearing this, slapped his thigh in an uncharacteristic display of emotion and declared that he would "unwhig" Fox for the rest of his life. Fox's argument did indeed seem to contradict his lifelong championing of Parliament's rights over the Crown. Pitt pointed out that the Prince of Wales had no more right to the throne than any other Briton, though he might well have a better claim to it as the King's firstborn son. It was Parliament's constitutional right to decide who the monarch could be.

There was more than naked thirst for power in Fox's seemingly hypocritical Tory assertion. Fox believed that the King's illness was permanent, and therefore that George III was, constitutionally speaking, dead. To challenge the Prince of Wales's right to succeed him would be to challenge fundamental contemporary assumptions about property rights and primogeniture. Pitt, on the other hand, considered the King's madness temporary (or, at least, hoped that it would be), and thus saw the throne as temporarily unoccupied rather than vacant.

While Fox drew up lists for his proposed Cabinet under the new Prince Regent, Pitt spun out the legalistic debates over the constitutionality of and precedents for instituting a regency, as well as the actual process of drawing up a Regency Bill and navigating it through Parliament. He negotiated a number of restrictions on the powers of the Prince of Wales as regent (which would later provide the basis of the Regency Act of 1811), but the bill finally passed the Commons on 12 February. As the Lords too prepared to pass it, they learned that the King's health was improving and decided to postpone further action. The King soon regained lucidity in time to prevent the establishment of his son's regency and the elevation of Fox to the premiership, and, on 23 April, a service of thanksgiving was conducted at St Paul's in honour of George III's return to health. Fox's opportunity had passed.

French Revolution

Fox welcomed the

Fox welcomed the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

of 1789, interpreting it as a late Continental

Continental may refer to:

Places

* Continent, the major landmasses of Earth

* Continental, Arizona, a small community in Pima County, Arizona, US

* Continental, Ohio, a small town in Putnam County, US

Arts and entertainment

* ''Continental'' ( ...

imitation of Britain's Glorious Revolution of 1688. In response to the Storming of the Bastille

The Storming of the Bastille (french: Prise de la Bastille ) occurred in Paris, France, on 14 July 1789, when revolutionary insurgents stormed and seized control of the medieval armoury, fortress, and political prison known as the Bastille. At ...

on 14 July, he famously declared, "How much the greatest event it is that ever happened in the world! and how much the best!" In April 1791, Fox told the Commons that he "admired the new constitution of France, considered altogether, as the most stupendous and glorious edifice of liberty, which had been erected on the foundation of human integrity in any time or country." He was thus somewhat bemused by the reaction of his old Whig friend, Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">N ...

, to the dramatic events across the Channel. In his ''Reflections on the Revolution in France

''Reflections on the Revolution in France'' is a political pamphlet written by the Irish statesman Edmund Burke and published in November 1790. It is fundamentally a contrast of the French Revolution to that time with the unwritten British Const ...

'', Burke warned that the revolution was a violent rebellion against tradition and proper authority, motivated by Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island societ ...

n, abstract ideas disconnected from reality, which would lead to anarchy and eventual dictatorship. Fox read the book and found it "in very bad taste" and "favouring Tory principles", but avoided pressing the matter for a while to preserve his relationship with Burke. The more radical Whigs, like Sheridan, broke with Burke more readily at this point.

Fox instead turned his attention – despite the politically volatile situation – to repealing the Test and Corporation

A corporation is an organization—usually a group of people or a company—authorized by the state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law "born out of statute"; a legal person in legal context) and ...

Acts, which restricted the liberties of Dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, an ...

and Catholics. On 2 March 1790, Fox gave a long and eloquent speech to a packed House of Commons.

Pitt, in turn, came to the defence of the Acts as adopted

Burke, with fear of the radical upheaval in France foremost in his mind, took Pitt's side in the debate, dismissing Nonconformists as "men of factious and dangerous principles", to which Fox replied that Burke's "strange dereliction from his former principles ... filled him with grief and shame". Fox's motion was defeated in the Commons by 294 votes to 105.

Later, Fox successfully supported the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1791, extending the rights of British Catholics. He explained his stance to his Roman Catholic friend, Charles Butler, declaring:

On the world stage of 1791, war with Great Britain was threatened more with Spain and

On the world stage of 1791, war with Great Britain was threatened more with Spain and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

than revolutionary France

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

. Fox opposed the bellicose stances of Pitt's ministry in the Nootka Sound crisis and over the Russian occupation of the Turkish port of Ochakiv

Ochakiv, also known as Ochakov ( uk, Оча́ків, ; russian: Очаков; crh, Özü; ro, Oceacov and ''Vozia'', and Alektor ( in Greek), is a small city in Mykolaiv Raion, Mykolaiv Oblast (region) of southern Ukraine. It hosts the admini ...

on the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

. Fox contributed to the peaceful resolution of these entanglements and gained a new admirer in Catherine the Great, who bought a bust of Fox and placed it between Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

and Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; el, Δημοσθένης, translit=Dēmosthénēs; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual pr ...

in her collection. On 18 April, Fox spoke in the Commons – together with William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 175929 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist and leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780, eventually becom ...

, Pitt and Burke – in favour of a measure to abolish the slave trade, but – despite their combined rhetorical talents – the vote went against them by a majority of 75.

On 6 May 1791, a tearful confrontation on the floor of the Commons finally shattered the quarter-century friendship of Fox and Burke, as the latter dramatically crossed the floor of the House to sit down next to Pitt, taking the support of a good deal of the more conservative Whigs with him. Officially, and rather irrelevantly, this happened during a debate on the particulars of a bill for the government of

On 6 May 1791, a tearful confrontation on the floor of the Commons finally shattered the quarter-century friendship of Fox and Burke, as the latter dramatically crossed the floor of the House to sit down next to Pitt, taking the support of a good deal of the more conservative Whigs with him. Officially, and rather irrelevantly, this happened during a debate on the particulars of a bill for the government of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. Later, on his deathbed in 1797, Burke would have his wife turn Fox away rather than allow a final reconciliation.

"Pitt's Terror"

Fox continued to defend the French Revolution, even as its fruits began to collapse into war, repression and the Reign of Terror. Though there were few developments in France after 1792 that Fox could positively favour, Fox maintained that the old monarchical system still proved a greater threat to liberty than the new, degenerating experiment in France. Fox thought of revolutionary France as the lesser of two evils and emphasised the role of traditional despots in perverting the course of the revolution: he argued that

Fox continued to defend the French Revolution, even as its fruits began to collapse into war, repression and the Reign of Terror. Though there were few developments in France after 1792 that Fox could positively favour, Fox maintained that the old monarchical system still proved a greater threat to liberty than the new, degenerating experiment in France. Fox thought of revolutionary France as the lesser of two evils and emphasised the role of traditional despots in perverting the course of the revolution: he argued that Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

and the French aristocracy had brought their fates upon themselves by abusing the constitution of 1791 and that the coalition of European autocrats, which was currently dispatching its armies against France's borders, had driven the revolutionary government to desperate and bloody measures by exciting a profound national crisis. Fox was not surprised when Pitt and the King brought Britain into the war as well and would afterwards blame the pair and their prodigal European subsidies for the long-drawn-out continuation of the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Prussia ...

. In 1795, he wrote to his nephew, Lord Holland:

Rather ironically, while Fox was being denounced by many in Britain as a Jacobin traitor, across the Channel he featured on a 1798 list of the Britons to be transported after a successful French invasion of Britain. According to the document, Fox was a "false patriot; having often insulted the French nation in his speeches, and particularly in 1786." According to one of his biographers, Fox's "loyalties were not national but were offered to people like himself at home or abroad". In 1805 Francis Horner wrote, "I could name to you gentlemen, with good coats on, and good sense in their own affairs, who believe that Fox...is actually in the pay of France".

But Fox's radical position soon became too extreme for many of his followers, particularly old Whig friends like the Duke of Portland

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranke ...

, Earl Fitzwilliam and the Earl of Carlisle

Earl of Carlisle is a title that has been created three times in the Peerage of England.

History

The first creation came in 1322, when Andrew Harclay, 1st Baron Harclay, was made Earl of Carlisle. He had already been summoned to Parliamen ...

. Around July 1794 their fear of France outgrew their resentment towards Pitt for his actions in 1784, and they crossed the floor to the Government benches. Fox could not believe that they "would disgrace" themselves in such a way. After these defections, the Foxites could no longer constitute a credible parliamentary opposition, reduced, as they were, to some fifty MPs.

Fox, however, still insisted on challenging the repressive wartime legislation introduced by Pitt in the 1790s that would become known as "Pitt's Terror". In 1792, Fox had seen through the only piece of substantial legislation in his career, the Libel Act 1792, which restored to juries the right to decide what was and was not libellous, in addition to whether a defendant was guilty. E. P. Thompson thought it "Fox's greatest service to the common people, passed at the eleventh hour before the tide turned toward repression." Indeed, the act was passed by Parliament on 21 May, the same day as a royal proclamation against seditious writings was issued, and more libel cases would be brought by the government in the following two years than had been in all the preceding years of the eighteenth century.

Fox spoke in opposition to the King's Speech on 13 December 1793, but was defeated in the subsequent division by 290 to 50. He argued against war measures like the stationing of Hessian troops in Britain, the employment of royalist French émigrés in the British army and, most of all, Pitt's suspension

Suspension or suspended may refer to:

Science and engineering

* Suspension (topology), in mathematics

* Suspension (dynamical systems), in mathematics

* Suspension of a ring, in mathematics

* Suspension (chemistry), small solid particles suspende ...

of habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

in 1794. He told the Commons that:

In 1795, the King's carriage was assaulted in the street, providing an excuse for Pitt to introduce the infamous Two Acts: the Seditious Meetings Act 1795

The Seditious Meetings Act 1795 (36 Geo.3 c.8) was approved by the British Parliament in December 1795; it had as its purpose was to restrict the size of public meetings to fifty persons.

It was the second of the well known "Two Acts" (also known ...

, which prohibited unlicensed gatherings of over fifty people, and the Treasonable Practices Act

The Treason Act 1795 (sometimes also known as the Treasonable and Seditious Practices Act) (36 Geo. 3 c. 7) was one of the Two Acts introduced by the British government in the wake of the stoning of King George III on his way to open Parl ...

, which greatly widened the legal definition of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, making any assault on the constitution punishable by seven years' transportation. Fox spoke ten times in the debate on the acts. He argued that, according to the principles of the proposed legislation, Pitt should have been transported a decade before in 1785, when he had been advocating parliamentary reform. Fox warned the Commons that

He argued that "the best security for the due maintenance of the constitution was in the strict and incessant vigilance of the people over parliament itself. Meetings of the people, therefore, for the discussion of public objects were not merely legal, but laudable."

Parliament passed the acts. But Fox enjoyed a swell of extra-parliamentary support during the course of the controversy. A substantial petitioning movement arose in support of him, and on 16 November 1795, he addressed a public meeting of between two- and thirty-thousand people on the subject. However, this came to nothing in the long run. The Foxites were becoming disenchanted with the Commons, overwhelmingly dominated by Pitt, and began to denounce it to one another as unrepresentative.

Parliament passed the acts. But Fox enjoyed a swell of extra-parliamentary support during the course of the controversy. A substantial petitioning movement arose in support of him, and on 16 November 1795, he addressed a public meeting of between two- and thirty-thousand people on the subject. However, this came to nothing in the long run. The Foxites were becoming disenchanted with the Commons, overwhelmingly dominated by Pitt, and began to denounce it to one another as unrepresentative.

Political wilderness: 1797–1806

Later life

By May 1797, an overwhelming majority – both in and outside of Parliament – had formed in support of Pitt's war against France.

Fox's following in Parliament had shrivelled to about 25, compared with around 55 in 1794 and at least 90 during the 1780s. Many of the Foxites purposefully seceded from Parliament in 1797; Fox himself retired for lengthy periods to his wife's house in Surrey. The distance from the stress and noise of Westminster was an enormous psychological and spiritual relief to Fox, but still he defended his earlier principles: "It is a great comfort to me to reflect how steadily I have opposed this war, for the miseries it seems likely to produce are without end."

On 1 May 1798, Fox proposed a toast to "Our Sovereign, the Majesty of the People". The

By May 1797, an overwhelming majority – both in and outside of Parliament – had formed in support of Pitt's war against France.

Fox's following in Parliament had shrivelled to about 25, compared with around 55 in 1794 and at least 90 during the 1780s. Many of the Foxites purposefully seceded from Parliament in 1797; Fox himself retired for lengthy periods to his wife's house in Surrey. The distance from the stress and noise of Westminster was an enormous psychological and spiritual relief to Fox, but still he defended his earlier principles: "It is a great comfort to me to reflect how steadily I have opposed this war, for the miseries it seems likely to produce are without end."

On 1 May 1798, Fox proposed a toast to "Our Sovereign, the Majesty of the People". The Duke of Norfolk

Duke of Norfolk is a title in the peerage of England. The seat of the Duke of Norfolk is Arundel Castle in Sussex, although the title refers to the county of Norfolk. The current duke is Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk. The dukes ...

had made the same toast in January at Fox's birthday dinner and had been dismissed as Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding of Yorkshire as a result. Pitt thought of sending Fox to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

for the duration of the parliamentary session but instead removed him from the Privy Council. Fox believed that it was "impossible to support the Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

f 1688and the Brunswick Succession upon any other principle" than the sovereignty of the people.

After Pitt's resignation in February 1801, Fox had undertaken a partial return to politics. Having opposed the Addington ministry (though he approved of its negotiation of the Treaty of Amiens) as a Pitt-style tool of the King, Fox gravitated towards the Grenvillite

The Grenville Whigs (or Grenvillites) were a name given to several British political factions of the 18th and the early 19th centuries, all of which were associated with the important Grenville family of Buckinghamshire.

Background

The Grenv ...

faction, which shared his support for Catholic emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

and composed the only parliamentary alternative to a coalition with the Pittites.

During the French Revolutionary Wars, Fox supported the French Republic against the monarchies that comprised the Second Coalition. Fox thought the ''coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

'' of 1799 that brought Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

to power "a very bad beginning ... the manner of the thing asquite odious", but he was convinced that the French leader sincerely desired peace in order to consolidate his rule and rebuild his shattered country.

By July 1800, Fox had "forgiven" the means by which he had come into power and claimed Napoleon had "surpassed...Alexander