Charing Cross (Glasgow) railway station on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in

The name of the lost hamlet, Charing, is derived from the

The name of the lost hamlet, Charing, is derived from the

At some time between 1232 and 1236, the Chapel and Hospital of St Mary Rounceval was founded at Charing. It occupied land at the corner of the modern Whitehall and into the centre of

At some time between 1232 and 1236, the Chapel and Hospital of St Mary Rounceval was founded at Charing. It occupied land at the corner of the modern Whitehall and into the centre of

'' In 1608–09, the

In 1608–09, the

''Old and New London'': Volume 3 (1878), pp. 123–134. accessed: 13 February 2009

The Eleanor Cross was pulled down, by order of Parliament, in 1647, at the time of the

The Eleanor Cross was pulled down, by order of Parliament, in 1647, at the time of the  A prominent pillory, where malefactors were publicly flogged, stood alongside for centuries. About 200 yards to the east was the Hungerford Market, established at the end of the 16th century; and to the north was the

A prominent pillory, where malefactors were publicly flogged, stood alongside for centuries. About 200 yards to the east was the Hungerford Market, established at the end of the 16th century; and to the north was the

The railway station opened in 1864, fronted on the

The railway station opened in 1864, fronted on the

Road distances from London continue to be measured from Charing Cross. Prior to its selection as a commonly agreed central datum point, various points were used for this purpose. John Ogilby's ''Britannia'' of 1675, of which editions and derivations continued to be published throughout the 18th century, used the "Standard" (a former conduit head) in Cornhill; while

Road distances from London continue to be measured from Charing Cross. Prior to its selection as a commonly agreed central datum point, various points were used for this purpose. John Ogilby's ''Britannia'' of 1675, of which editions and derivations continued to be published throughout the 18th century, used the "Standard" (a former conduit head) in Cornhill; while

''Charing Cross Bridge'' in London from Claude Monet, in YOUR CITY AT THE THYSSEN, a Thyssen Museum project on Flickr

*'The statue of Charles I and site of the Charing Cross', Survey of London: volume 16: St Martin-in-the-Fields I: Charing Cross (1935), pp. 258–268. URL

The statue of Charles I and site of the Charing Cross , British History Online

Retrieved 6 March 2014. {{Authority control Areas of London Districts of the City of Westminster Kilometre-zero markers Monuments and memorials in London Execution sites in England London crime history

Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

, London, England, where six routes meet. Clockwise from north these are: the east side of Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

leading to St Martin's Place and then Charing Cross Road

Charing Cross Road is a street in central London running immediately north of St Martin-in-the-Fields to St Giles Circus (the intersection with Oxford Street) and then becomes Tottenham Court Road. It leads from the north in the direction ...

; the Strand

Strand may refer to:

Topography

*The flat area of land bordering a body of water, a:

** Beach

** Shoreline

* Strand swamp, a type of swamp habitat in Florida

Places Africa

* Strand, Western Cape, a seaside town in South Africa

* Strand Street ...

leading to the City

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

; Northumberland Avenue

Northumberland Avenue is a street in the City of Westminster, Central London, running from Trafalgar Square in the west to the Thames Embankment in the east. The road was built on the site of Northumberland House, the London home of the Percy ...

leading to the Thames Embankment

The Thames Embankment is a work of 19th-century civil engineering that reclaimed marshy land next to the River Thames in central London. It consists of the Victoria Embankment and Chelsea Embankment.

History

There had been a long history of ...

; Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea. It is the main thoroughfare running south from Trafalgar Square towards Parliament Sq ...

leading to Parliament Square

Parliament Square is a square at the northwest end of the Palace of Westminster in the City of Westminster in central London. Laid out in the 19th century, it features a large open green area in the centre with trees to its west, and it contai ...

; The Mall leading to Admiralty Arch

Admiralty Arch is a landmark building in London providing road and pedestrian access between The Mall, which extends to the southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. Admiralty Arch, commissioned by King Edward VII in memory of his mo ...

and Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a London royal residence and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and royal hospitality. It ...

; and two short roads leading to Pall Mall. The name also commonly refers to the Queen Eleanor Memorial Cross

The Queen Eleanor Memorial Cross is a memorial to Eleanor of Castile erected in the forecourt of Charing Cross railway station, London, in 1864–1865. It is a fanciful reconstruction of the medieval Eleanor cross at Charing, one of twelve memoria ...

at Charing Cross station.

A bronze equestrian statue of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, erected in 1675, stands on a high plinth, situated roughly where a medieval monumental cross had previously stood for 353 years (since its construction in 1294) until destroyed in 1647 by Cromwell and his revolutionary government. The famously beheaded King, appearing ascendant, is the work of French sculptor Hubert Le Sueur

Hubert Le Sueur (c. 1580 – 1658) was a French sculptor with the contemporaneous reputation of having trained in Giambologna's Florentine workshop. He assisted Giambologna's foreman, Pietro Tacca, in Paris, in finishing and erecting the equestria ...

.

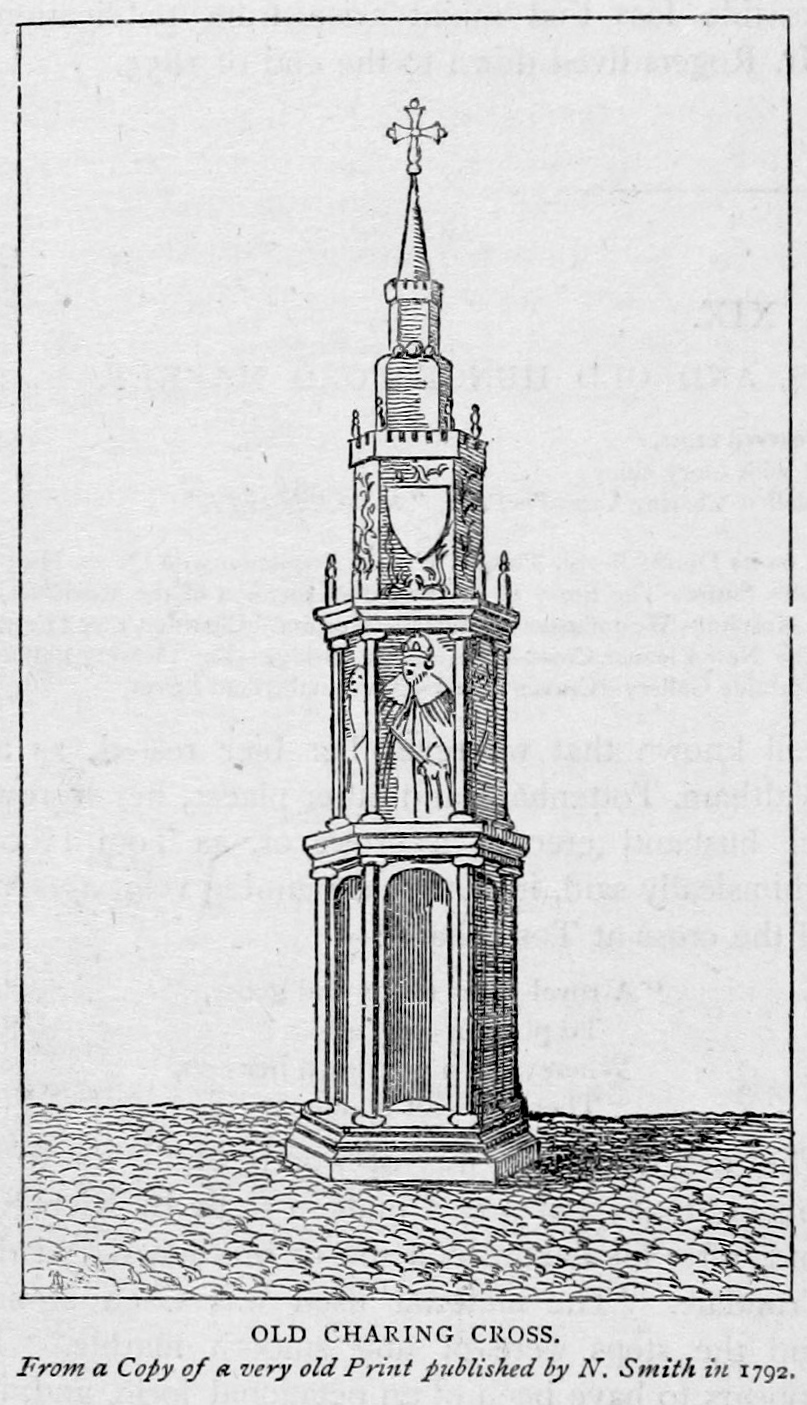

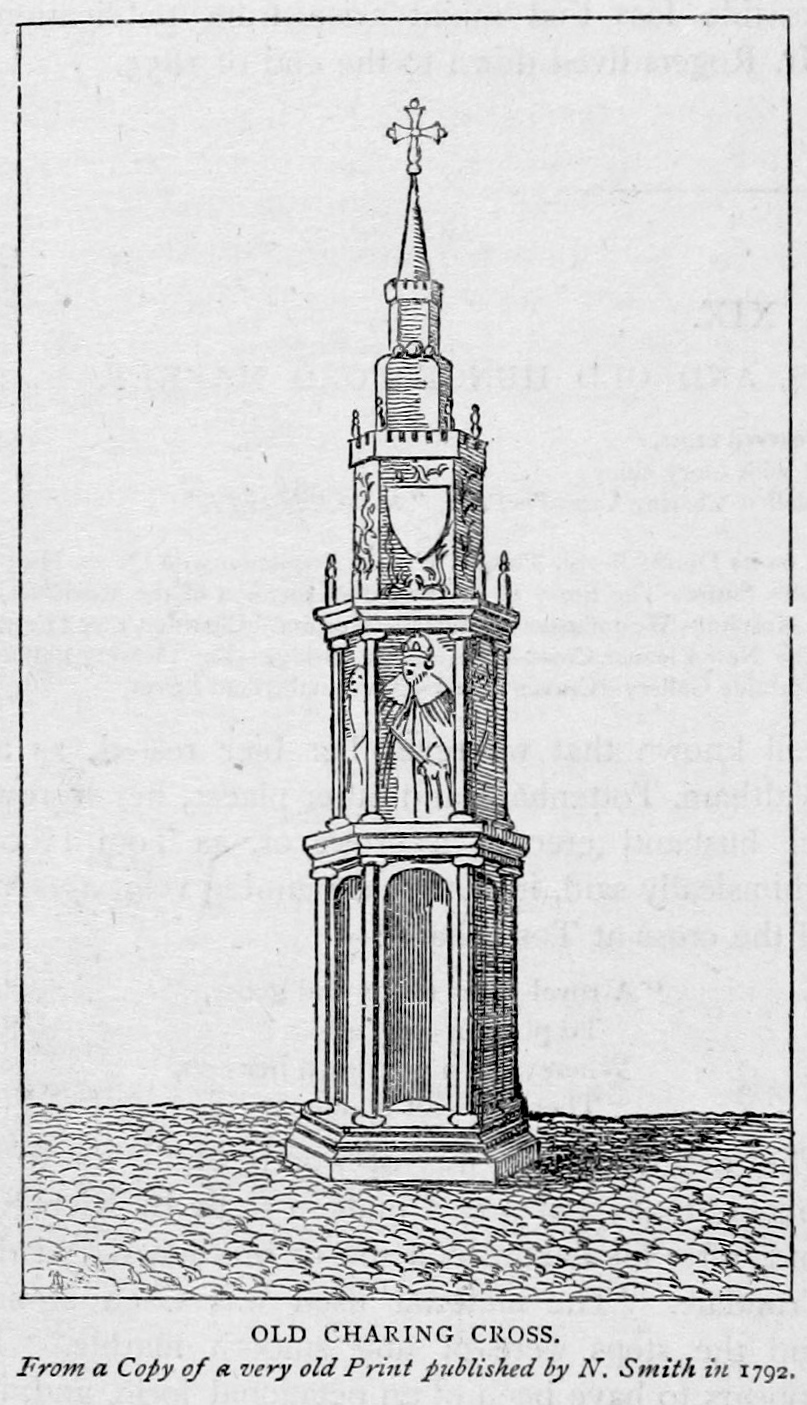

The aforementioned eponymous monument, the "Charing Cross", was the largest and most ornate instance of a chain of medieval Eleanor cross

The Eleanor crosses were a series of twelve tall and lavishly decorated stone monuments topped with crosses erected in a line down part of the east of England. King Edward I had them built between 1291 and about 1295 in memory of his beloved wi ...

es running from Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

to this location. It was a landmark for many centuries of the hamlet of Charing, Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

, which later gave way to government property; a little of The Strand; and Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

. The cross in its various historical forms has also lent its name to its locality, and especially Charing Cross Station. On the forecourt of this terminus station stands the ornate Queen Eleanor Memorial Cross, a taller emulation of the original, and built to mark the station's opening in 1864 – at the height and in the epicentre of the Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

– after the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north b ...

's rebuilding and before Westminster Cathedral

Westminster Cathedral is the mother church of the Catholic Church in England and Wales. It is the largest Catholic church in the UK and the seat of the Archbishop of Westminster.

The site on which the cathedral stands in the City o ...

's construction.

Charing Cross is marked on contemporary maps as a road junction, though it is also a thoroughfare in postal addresses: Drummonds Bank

Messrs. Drummond is a formerly independent private bank that is now owned by NatWest Group. The Royal Bank of Scotland incorporating Messrs. Drummond, Bankers is based at 49 Charing Cross in central London. Drummonds is authorised as a brand of ...

, on the corner with The Mall, retains the address 49 Charing Cross and 1-4 Charing Cross continues to exist. The name previously applied to the whole stretch of road between Great Scotland Yard

Great Scotland Yard is a street in the St. James's district of Westminster, London, connecting Northumberland Avenue and Whitehall. By the 16th century, this 'yard', which was then an open space for the Palace of Whitehall, was fronted by buil ...

and Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

, but since 1 January 1931 most of this section of road has been designated part of the 'Whitehall' thoroughfare. Since the early 19th century, Charing Cross has been the notional "centre of London" and is now the point from which distances from London are measured.

History

Location and etymology

The name of the lost hamlet, Charing, is derived from the

The name of the lost hamlet, Charing, is derived from the Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

word ''cierring'', a river bend, in this case thus meaning: in the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

.

The suffix "Cross" refers to the Eleanor cross

The Eleanor crosses were a series of twelve tall and lavishly decorated stone monuments topped with crosses erected in a line down part of the east of England. King Edward I had them built between 1291 and about 1295 in memory of his beloved wi ...

made during 1291–94 by order of King Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vas ...

as a memorial to his wife, Eleanor of Castile

Eleanor of Castile (1241 – 28 November 1290) was Queen of England as the first wife of Edward I, whom she married as part of a political deal to affirm English sovereignty over Gascony.

The marriage was known to be particularly close, and ...

. At the time, this place comprised little more than wayside cottages serving the Royal Mews

The Royal Mews is a mews, or collection of equestrian stables, of the British Royal Family. In London these stables and stable-hands' quarters have occupied two main sites in turn, being located at first on the north side of Charing Cross, and ...

in the northern area of today's Trafalgar Square, and built specifically for the Palace of Whitehall

The Palace of Whitehall (also spelt White Hall) at Westminster was the main residence of the English monarchs from 1530 until 1698, when most of its structures, except notably Inigo Jones's Banqueting House of 1622, were destroyed by fire. ...

(today much of the east side of Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea. It is the main thoroughfare running south from Trafalgar Square towards Parliament Sq ...

). A debunked folk etymology

Folk etymology (also known as popular etymology, analogical reformation, reanalysis, morphological reanalysis or etymological reinterpretation) is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a more famili ...

ran that the name is a corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense which is undertaken by a person or an organization which is entrusted in a position of authority, in order to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's personal gain. Corruption m ...

of ''chère reine'' ("dear queen" in French), but the name pre-dates Eleanor's death by at least a hundred years. A variant form in the hazy Middle English orthography

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English p ...

of the late fourteenth century is ''Cherryngescrouche''.

The stone cross was the work of the medieval sculptor, Alexander of Abingdon. It was destroyed in 1647 on the orders of the purely Parliamentarian phase of the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septe ...

or Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

himself in the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

. A -high stone sculpture

A stone sculpture is an object made of stone which has been shaped, usually by carving, or assembled to form a visually interesting three-dimensional shape. Stone is more durable than most alternative materials, making it especially important in ...

in front of Charing Cross railway station

Charing Cross railway station (also known as London Charing Cross) is a central London railway terminus between the Strand and Hungerford Bridge in the City of Westminster. It is the terminus of the South Eastern Main Line to Dover via Ashfo ...

, erected in 1865, is a reimagining of the medieval cross, on a larger scale, more ornate, and not on the original site. It was designed by the architect E. M. Barry

Edward Middleton Barry RA (7 June 1830 – 27 January 1880) was an English architect of the 19th century.

Biography

Edward Barry was the third son of Sir Charles Barry, born in his father's house, 27 Foley Place, London. In infancy he was ...

and carved by Thomas Earp Thomas Earp may refer to:

* Thomas Earp (politician)

* Thomas Earp (sculptor)

{{hndis, Earp, Thomas ...

of Lambeth out of Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone from the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period quarried on the Isle of Portland, Dorset. The quarries are cut in beds of white-grey limestone separated by chert beds. It has been used extensively as a building ...

, Mansfield

Mansfield is a market town and the administrative centre of Mansfield District in Nottinghamshire, England. It is the largest town in the wider Mansfield Urban Area (followed by Sutton-in-Ashfield). It gained the Royal Charter of a market to ...

stone (a fine sandstone) and Aberdeen granite; and it stands 222 yards (203 metres) to the north-east of the original cross, focal to the station forecourt, facing the Strand

Strand may refer to:

Topography

*The flat area of land bordering a body of water, a:

** Beach

** Shoreline

* Strand swamp, a type of swamp habitat in Florida

Places Africa

* Strand, Western Cape, a seaside town in South Africa

* Strand Street ...

.

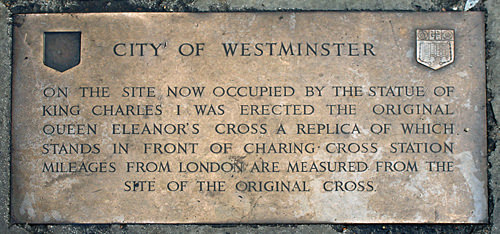

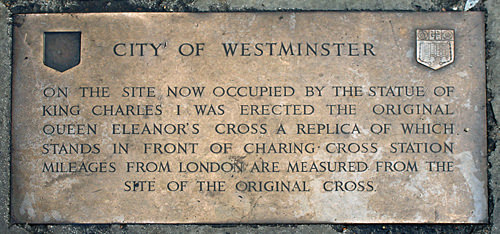

Since 1675 the site of the cross has been occupied by a statue of King Charles I mounted on a horse. The site is recognised by modern convention as the centre of London for the purpose of indicating distances (whether geodesically or by road network) in preference to other measurement points (such as St Paul's Cathedral which remains as the root of the English and Welsh part of the Great Britain road numbering scheme

The Great Britain road numbering scheme is a numbering scheme used to classify and identify all roads in Great Britain.

Each road is given a single letter (which represents the road's category) and a subsequent number (between 1 and 4 digits). ...

). Charing Cross is marked on modern maps as a road junction, and was used in street numbering for today's section of Whitehall between Great Scotland Yard

Great Scotland Yard is a street in the St. James's district of Westminster, London, connecting Northumberland Avenue and Whitehall. By the 16th century, this 'yard', which was then an open space for the Palace of Whitehall, was fronted by buil ...

and Trafalgar Square. Since 1 January 1931 this segment has more logically and officially become the northern end of Whitehall.

The rebuilding of a monument to resemble the one lost under Cromwell's low church Britain took place in 1864 in Britain's main era of medieval revivalism. The next year the memorial was completed and Cardinal Wiseman

Nicholas Patrick Stephen Wiseman (3 August 1802 – 15 February 1865) was a Cardinal of the Catholic Church who became the first Archbishop of Westminster upon the re-establishment of the Catholic hierarchy in England and Wales in 1850.

Bor ...

died, the first Archbishop of Westminster, having been appointed such in 1850, with many Anglican churches also having restored or re-created their medieval ornamentations by the end of the century. By this time England was the epicentre of the Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

.N. Yates, ''Liturgical Space: Christian Worship and Church Buildings in Western Europe 1500-2000'' (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2008), p. 114, It was intertwined with deeply philosophical movements associated with a re-awakening of "High Church" or Anglo-Catholic

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholic heritage and identity of the various Anglican churches.

The term was coined in the early 19th century, although movements emphasising the Catholic nature of Anglica ...

self-belief (and by the Catholic convert Augustus Welby Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 181214 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and, ultimately, Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival st ...

) concerned by the growth of religious nonconformism.

The cross, having been revived, gave its name to a railway station

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

, a tube station

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or by its nickname the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The Und ...

, a police station, a hospital, a hotel, a theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perform ...

, and a music hall (which had lain beneath the arches of the railway station). Charing Cross Road

Charing Cross Road is a street in central London running immediately north of St Martin-in-the-Fields to St Giles Circus (the intersection with Oxford Street) and then becomes Tottenham Court Road. It leads from the north in the direction ...

, the main route from the north (which became the east side of Trafalgar Square), was named after the railway station, itself a major destination for traffic, rather than after the original cross.

St Mary Rounceval

At some time between 1232 and 1236, the Chapel and Hospital of St Mary Rounceval was founded at Charing. It occupied land at the corner of the modern Whitehall and into the centre of

At some time between 1232 and 1236, the Chapel and Hospital of St Mary Rounceval was founded at Charing. It occupied land at the corner of the modern Whitehall and into the centre of Northumberland Avenue

Northumberland Avenue is a street in the City of Westminster, Central London, running from Trafalgar Square in the west to the Thames Embankment in the east. The road was built on the site of Northumberland House, the London home of the Percy ...

, running down to a wharf by the river. It was an Augustinian house, tied to a mother house at Roncesvalles

Roncesvalles ( , ; eu, Orreaga ; an, Ronzesbals ; french: Roncevaux ) is a small village and municipality in Navarre, northern Spain. It is situated on the small river Urrobi at an altitude of some in the Pyrenees, about from the French bor ...

in the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

. The house and lands were seized for the king in 1379, under a statute "for the forfeiture of the lands of schismatic aliens". Protracted legal action returned some rights to the prior, but in 1414, Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1 ...

suppressed the 'alien' houses. The priory fell into a long decline owing to lack of money and arguments regarding the collection of tithes with the parish church of St Martin-in-the-Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. It is dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. There has been a church on the site since at least the mediev ...

. In 1541, religious artefacts were removed to St Margaret's, and the chapel was adapted as a private house; its almshouse were sequestered to the Royal Palace.''The chapel and hospital of St. Mary Rounceval''''

Survey of London

The Survey of London is a research project to produce a comprehensive architectural survey of central London and its suburbs, or the area formerly administered by the London County Council. It was founded in 1894 by Charles Robert Ashbee, an A ...

'': volume 18: St Martin-in-the-Fields II: The Strand (1937), pp. 1–9. Retrieved 14 February 2009

Earl of Northampton

Earl of Northampton is a title in the Peerage of England that has been created five times.

Earls of Northampton, First Creation (1071)

* Waltheof (d. 1076)

* Maud, Queen of Scotland (c.1074–1130/31)

*Simon II de Senlis (1103–1153)

* Simon I ...

built Northumberland House

Northumberland House (also known as Suffolk House when owned by the Earls of Suffolk) was a large Jacobean townhouse in London, so-called because it was, for most of its history, the London residence of the Percy family, who were the Ear ...

on the eastern portion of the property. In June 1874, the whole of the duke's property at Charing Cross was purchased by the Metropolitan Board of Works

The Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was the principal instrument of local government in a wide area of Middlesex, Surrey, and Kent, defined by the Metropolis Management Act 1855, from December 1855 until the establishment of the London Cou ...

for the formation of Northumberland Avenue.

The frontage of the Rounceval property caused the narrowing at the end of the Whitehall entry to Charing Cross, and formed the section of Whitehall formerly known as Charing Cross, until road widening in the 1930s caused the rebuilding of the south side of the street, creating the current wide thoroughfare.

Battle

In 1554, Charing Cross was the site of the final battle of Wyatt's Rebellion. This was an attempt by Thomas Wyatt and others to overthrow Queen Mary I of England, soon after her accession to the throne, and replace her with Lady Jane Grey. Wyatt's army had come from Kent, and with London Bridge barred to them, had crossed the river by what was then the next bridge upstream, atHampton Court

Hampton Court Palace is a Grade I listed royal palace in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, southwest and upstream of central London on the River Thames. The building of the palace began in 1514 for Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the chie ...

. Their circuitous route brought them down St Martin's Lane to Whitehall.

The palace was defended by 1000 men under Sir John Gage

John Burdette Gage (born October 9, 1942) was the 21st employee of Sun Microsystems, where he is credited with creating the phrase The Network is the Computer. He served as vice president and chief researcher and director of the Science Office ...

at Charing Cross; they retreated within Whitehall after firing their shot, causing consternation within, thinking the force had changed sides. The rebels – themselves fearful of artillery on the higher ground around St James's

St James's is a central district in the City of Westminster, London, forming part of the West End. In the 17th century the area developed as a residential location for the British aristocracy, and around the 19th century was the focus of the d ...

– did not press their attack and marched on to Ludgate

Ludgate was the westernmost gate in London Wall. Of Roman origin, it was rebuilt several times and finally demolished in 1760. The name survives in Ludgate Hill, an eastward continuation of Fleet Street, Ludgate Circus and Ludgate Square.

Etym ...

, where they were met by the Tower Garrison and surrendered.''Charing Cross, the railway stations, and Old Hungerford Market''''Old and New London'': Volume 3 (1878), pp. 123–134. accessed: 13 February 2009

Civil war removal

The Eleanor Cross was pulled down, by order of Parliament, in 1647, at the time of the

The Eleanor Cross was pulled down, by order of Parliament, in 1647, at the time of the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

, becoming the subject of a popular Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governm ...

ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads derive from the medieval French ''chanson balladée'' or ''ballade'', which were originally "dance songs". Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and ...

:

At the Restoration (1660 or shortly after) eight of the regicide

Regicide is the purposeful killing of a monarch or sovereign of a polity and is often associated with the usurpation of power. A regicide can also be the person responsible for the killing. The word comes from the Latin roots of ''regis'' ...

s were executed here, including the notable Fifth Monarchist, Colonel Thomas Harrison. A statue of Charles I was, likewise in Charles II's reign, erected on the site. This had been made in 1633 by Hubert Le Sueur

Hubert Le Sueur (c. 1580 – 1658) was a French sculptor with the contemporaneous reputation of having trained in Giambologna's Florentine workshop. He assisted Giambologna's foreman, Pietro Tacca, in Paris, in finishing and erecting the equestria ...

, in the reign of Charles I, but in 1649 Parliament ordered a man to destroy it; however he instead hid it and brought it back to the new King, Charles II (Charles I's son), and his Parliament who had the statue erected here in 1675.

A prominent pillory, where malefactors were publicly flogged, stood alongside for centuries. About 200 yards to the east was the Hungerford Market, established at the end of the 16th century; and to the north was the

A prominent pillory, where malefactors were publicly flogged, stood alongside for centuries. About 200 yards to the east was the Hungerford Market, established at the end of the 16th century; and to the north was the King's Mews

The Royal Mews is a mews, or collection of equestrian stables, of the British Royal Family. In London these stables and stable-hands' quarters have occupied two main sites in turn, being located at first on the north side of Charing Cross, a ...

, or Royal Mews, the stables for the Palace of Whitehall and thus the King's own presence at the Houses of Parliament (Palace of Westminster). The whole area of the broad pavements of what was a three-way main junction with private (stables) turn-off was a popular place of street entertainment. Samuel Pepys records in his diaries visiting the taverns and watching the entertainments and executions that were held there. This was combined with the south of the mews when Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

was built on the site in 1832, the rest of the stable yard becoming the National Gallery primarily.

A major London coaching inn, the "Golden Cross" – first mentioned in 1643 – faced this junction. From here, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, coaches linked variously terminuses of: Dover, Brighton, Bath, Bristol, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

, Holyhead and York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

. The inn features in ''Sketches by Boz

''Sketches by "Boz," Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People'' (commonly known as ''Sketches by Boz'') is a collection of short pieces Charles Dickens originally published in various newspapers and other periodicals between 1833 and ...

'', ''David Copperfield

''David Copperfield'' Dickens invented over 14 variations of the title for this work, see is a novel in the bildungsroman genre by Charles Dickens, narrated by the eponymous David Copperfield, detailing his adventures in his journey from inf ...

'' and ''The Pickwick Papers

''The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club'' (also known as ''The Pickwick Papers'') was Charles Dickens's first novel. Because of his success with '' Sketches by Boz'' published in 1836, Dickens was asked by the publisher Chapman & Hall to ...

'' by Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

. In the latter, the dangers to public safety of the quite low archway to access the inn's coaching yard were memorably pointed out by Mr Jingle

Alfred Jingle is a fictional character who appears in the 1837 novel '' The Pickwick Papers'' by Charles Dickens. He is a strolling actor and an engaging charlatan and trickster noted for his bizarre anecdotes and distinctive mangling of Englis ...

:

"Heads, heads – take care of your heads", cried the loquacious stranger as they came out under the low archway which in those days formed the entrance to the coachyard. "Terrible place – dangerous work – other day – five children – mother – tall lady, eating sandwiches – forgot the arch – crash – knock – children look round – mother's head off – sandwich in her hand – no mouth to put it in – head of family off."The story echoes an accident of 11 April 1800, when the Chatham and Rochester coach was emerging from the gateway of the Golden Cross, and "a young woman, sitting on the top, threw her head back, to prevent her striking against the beam; but there being so much luggage on the roof of the coach as to hinder her laying herself sufficiently back, it caught her face, and tore the flesh in a dreadful manner." The inn and its yard, pillory, and what remained of the Royal Mews, made way for

Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster, Central London, laid out in the early 19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. At its centre is a high column bearing a statue of Admiral Nelson comm ...

, and a new Golden Cross Hotel was built in the 1830s on the triangular block fronted by South Africa House. A nod to this is made by some offices on the Strand, in a building named Golden Cross House.

Replacement

The railway station opened in 1864, fronted on the

The railway station opened in 1864, fronted on the Strand

Strand may refer to:

Topography

*The flat area of land bordering a body of water, a:

** Beach

** Shoreline

* Strand swamp, a type of swamp habitat in Florida

Places Africa

* Strand, Western Cape, a seaside town in South Africa

* Strand Street ...

with the Charing Cross Hotel. In 1865, a replacement cross was commissioned from E. M. Barry

Edward Middleton Barry RA (7 June 1830 – 27 January 1880) was an English architect of the 19th century.

Biography

Edward Barry was the third son of Sir Charles Barry, born in his father's house, 27 Foley Place, London. In infancy he was ...

by the South Eastern Railway as the centrepiece of the station forecourt. It is not a replica, being of an ornate Victorian Gothic design based on George Gilbert Scott's Oxford Martyrs' Memorial

The Martyrs' Memorial is a stone monument positioned at the intersection of St Giles', Magdalen Street and Beaumont Street, to the west of Balliol College, Oxford, England. It commemorates the 16th-century Oxford Martyrs.

History

The monu ...

(1838). The Cross rises in three main stages on an octagonal plan, surmounted by a spire and cross. The shields in the panels of the first stage are copied from the Eleanor Crosses and bear the arms of England, Castile, Leon

Leon, Léon (French) or León (Spanish) may refer to:

Places

Europe

* León, Spain, capital city of the Province of León

* Province of León, Spain

* Kingdom of León, an independent state in the Iberian Peninsula from 910 to 1230 and again f ...

and Ponthieu

Ponthieu (, ) was one of six feudal counties that eventually merged to become part of the Province of Picardy, in northern France.Dunbabin.France in the Making. Ch.4. The Principalities 888-987 Its chief town is Abbeville.

History

Ponthieu play ...

; above the 2nd parapet are eight statues of Queen Eleanor. The Cross was designated a Grade II*

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

monument on 5 February 1970. The month before, the bronze equestrian statue of Charles, on a pedestal of carved Portland stone, was given Grade I listed protection.

Official use as central point

By the late 18th century, the Charing Cross district was increasingly coming to be perceived as the "centre" of themetropolis

A metropolis () is a large city or conurbation which is a significant economic, political, and cultural center for a country or region, and an important hub for regional or international connections, commerce, and communications.

A big ci ...

(supplanting the traditional heartland of the City

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Science Encyclopedia''. 2nd edition. London: Routledge. It can be def ...

to the east). From the early 19th century, legislation applicable only to the London metropolis used Charing Cross as a central point to define its geographical scope. Its later use in legislation waned in favour of providing a schedule of local government areas and became mostly obsolete with the creation of Greater London in 1965.

Road distances from London continue to be measured from Charing Cross. Prior to its selection as a commonly agreed central datum point, various points were used for this purpose. John Ogilby's ''Britannia'' of 1675, of which editions and derivations continued to be published throughout the 18th century, used the "Standard" (a former conduit head) in Cornhill; while

Road distances from London continue to be measured from Charing Cross. Prior to its selection as a commonly agreed central datum point, various points were used for this purpose. John Ogilby's ''Britannia'' of 1675, of which editions and derivations continued to be published throughout the 18th century, used the "Standard" (a former conduit head) in Cornhill; while John Cary

John Cary (c. 1754 – 1835) was an English cartographer.

Life

Cary served his apprenticeship as an engraver in London, before setting up his own business in the Strand in 1783. He soon gained a reputation for his maps and globes, his atlas ...

's ''New Itinerary'' of 1798 used the General Post Office in Lombard Street. The milestone

A milestone is a numbered marker placed on a route such as a road, railway line, canal or boundary. They can indicate the distance to towns, cities, and other places or landmarks; or they can give their position on the route relative to so ...

s on the main turnpike roads were mostly measured from their terminus which was peripheral to the free-passage urban, London roads. Ten of these are notable: Hyde Park Corner

Hyde Park Corner is between Knightsbridge, Belgravia and Mayfair in London, England. It primarily refers to its major road junction at the southeastern corner of Hyde Park, that was designed by Decimus Burton. Six streets converge at the j ...

, Whitechapel Church, the southern end of London Bridge, the east end of Westminster Bridge

Westminster Bridge is a road-and-foot-traffic bridge over the River Thames in London, linking Westminster on the west side and Lambeth on the east side.

The bridge is painted predominantly green, the same colour as the leather seats in the ...

, Shoreditch Church

Shoreditch is a district in the East End of London in England, and forms the southern part of the London Borough of Hackney. Neighbouring parts of Tower Hamlets are also perceived as part of the area.

In the 16th century, Shoreditch was an impor ...

, Tyburn Turnpike (Marble Arch), Holborn Bars

Holborn Bars, also known as the Prudential Assurance Building is a large red terracotta Victorian building on the north side (138–142) of Holborn in Camden at the boundary of the City of London, England. The block is bounded by Holborn to t ...

, St Giles's Pound

St Giles's Pound was a cattle pound at St Giles Circus in central London in the 17th and 18th centuries, at the intersection of the roads from Hampstead and from Oxford. It became a point from which distances to London were measured.

The pound w ...

, Hicks Hall

Hicks Hall, or Hickes' Hall, was a courthouse at the southern end of St John Street, Clerkenwell, London. It opened in 1612, and was closed and demolished in 1782. It was the first purpose-built sessions house for justices of the peace of the ...

(as to the Great North Road), and the Stones' End in The Borough. Some roads into Surrey and Sussex were measured from St Mary-le-Bow church in the City. Some of these structures were later moved or destroyed, but reference to them persisted as if they still remained in place. An exaggerated but well-meaning criticism was that "all the Books of Roads ... published, differ in the Situation of Mile Stones, and instead of being a Guide to the Traveller, serve only to confound him".

William Camden

William Camden (2 May 1551 – 9 November 1623) was an English antiquarian, historian, topographer, and herald, best known as author of ''Britannia'', the first chorographical survey of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, and the ''Ann ...

speculated in 1586 that Roman roads in Britain

Roman roads in Britannia were initially designed for military use, created by the Roman Army during the nearly four centuries (AD 43–410) that Britannia was a province of the Roman Empire.

It is estimated that about of paved trunk ...

had been measured from London Stone

London Stone is a historic landmark housed at 111 Cannon Street in the City of London. It is an irregular block of oolitic limestone measuring 53 × 43 × 30 cm (21 × 17 × 12"), the remnant of a once much larger object that had stood ...

, a claim thus widely repeated, but unsupported by archaeological or other evidence.

Neighbouring locations

Transport

To the east of the Charing Cross road junction isCharing Cross railway station

Charing Cross railway station (also known as London Charing Cross) is a central London railway terminus between the Strand and Hungerford Bridge in the City of Westminster. It is the terminus of the South Eastern Main Line to Dover via Ashfo ...

, situated on The Strand. On the other side of the river, connected by the pedestrian Golden Jubilee Bridges

The Hungerford Bridge crosses the River Thames in London, and lies between Waterloo Bridge and Westminster Bridge. Owned by Network Rail Infrastructure Ltd (who use its official name of Charing Cross Bridge) it is a steel truss bridge, truss ...

, are Waterloo East and Waterloo stations.

The nearest London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or by its nickname the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The ...

stations are Charing Cross and Embankment

Embankment may refer to:

Geology and geography

* A levee, an artificial bank raised above the immediately surrounding land to redirect or prevent flooding by a river, lake or sea

* Embankment (earthworks), a raised bank to carry a road, railwa ...

.

References

External links

''Charing Cross Bridge'' in London from Claude Monet, in YOUR CITY AT THE THYSSEN, a Thyssen Museum project on Flickr

*'The statue of Charles I and site of the Charing Cross', Survey of London: volume 16: St Martin-in-the-Fields I: Charing Cross (1935), pp. 258–268. URL

The statue of Charles I and site of the Charing Cross , British History Online

Retrieved 6 March 2014. {{Authority control Areas of London Districts of the City of Westminster Kilometre-zero markers Monuments and memorials in London Execution sites in England London crime history