Celtic nations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Celtic nations are a cultural area and collection of geographical

The Celtic nations are a cultural area and collection of geographical

Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage website. There are virtually no known fluent speakers of Irish Gaelic in Newfoundland or Labrador today. Knowledge seems to be largely restricted to memorized passages, such as traditional tales and songs.

The Celtic languages form a branch of the greater

The Celtic languages form a branch of the greater

Formal cooperation between the Celtic nations is active in many contexts, including politics, languages, culture, music and sports:

The

Formal cooperation between the Celtic nations is active in many contexts, including politics, languages, culture, music and sports:

The

During the

During the

The

The

In Celtic languages,

In Celtic languages,

Most French people identify with the ancient

Most French people identify with the ancient

After the partitioning of the British colony of Nova Scotia in 1784 New Brunswick was originally named New Ireland with the capital to be in Saint John.

Large swathes of the United States of America were subject to migration from Celtic peoples, or people from Celtic nations. Irish-speaking

After the partitioning of the British colony of Nova Scotia in 1784 New Brunswick was originally named New Ireland with the capital to be in Saint John.

Large swathes of the United States of America were subject to migration from Celtic peoples, or people from Celtic nations. Irish-speaking

Celtic League

{{DEFAULTSORT:Celtic Nations Cultural regions Geography of Northwestern Europe Linguistic regions of Europe

region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and the interaction of humanity and t ...

s in Northwestern Europe

Northwestern Europe, or Northwest Europe, is a loosely defined subregion of Europe, overlapping Northern and Western Europe. The region can be defined both geographically and ethnographically.

Geographic definitions

Geographically, North ...

where the Celtic languages

The Celtic languages ( usually , but sometimes ) are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward ...

and cultural traits have survived. The term ''nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by those ...

'' is used in its original sense to mean a people who share a common identity and culture and are identified with a traditional territory.

The six regions widely considered Celtic nations are Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

(''Breizh''), Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

(''Kernow''), Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

(''Éire''), the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = "O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe ...

(''Mannin'', or ''Ellan Vannin''), Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

(''Alba''), and Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

(''Cymru''). In each of the six nations a Celtic language is spoken to some extent: Brittonic

Brittonic or Brythonic may refer to:

*Common Brittonic, or Brythonic, the Celtic language anciently spoken in Great Britain

*Brittonic languages, a branch of the Celtic languages descended from Common Brittonic

*Britons (Celtic people)

The Br ...

or Brythonic languages are spoken in Brittany (Breton

Breton most often refers to:

*anything associated with Brittany, and generally

** Breton people

** Breton language, a Southwestern Brittonic Celtic language of the Indo-European language family, spoken in Brittany

** Breton (horse), a breed

**Ga ...

), Cornwall ( Cornish) and Wales (Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

), whilst Goidelic

The Goidelic or Gaelic languages ( ga, teangacha Gaelacha; gd, cànanan Goidhealach; gv, çhengaghyn Gaelgagh) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historically ...

or Gaelic languages are spoken in Scotland (Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

), Ireland (Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

), and the Isle of Man ( Manx).

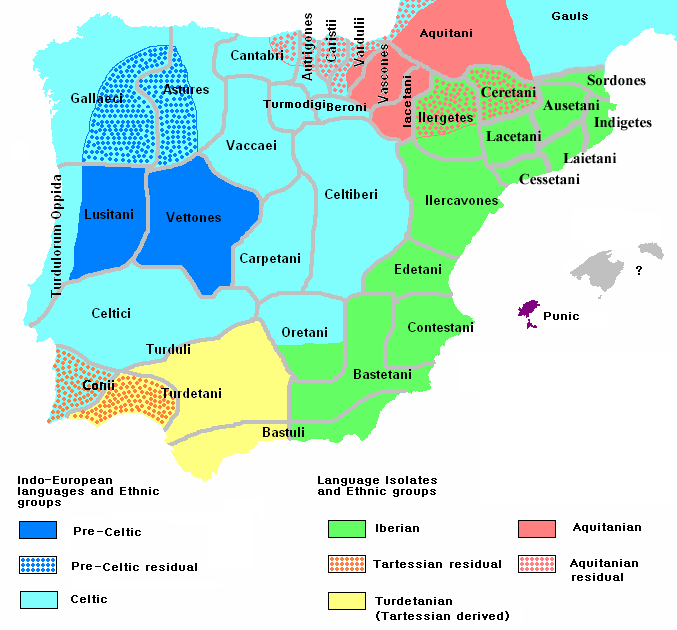

Before the expansions of Ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 B ...

and the Germanic and Slavic-speaking tribes, a significant part of Europe was dominated by Celtic-speaking cultures, leaving behind a legacy of Celtic cultural traits. Territories in north-western Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

—particularly northern Portugal

The North Region ( pt, Região do Norte ) or Northern Portugal is the most populous region in Portugal, ahead of Lisbon Region, Lisbon, and the third most extensive by area. The region has 3,576,205 inhabitants according to the 2017 census, and its ...

, Galicia, Asturias

Asturias (, ; ast, Asturies ), officially the Principality of Asturias ( es, Principado de Asturias; ast, Principáu d'Asturies; Galician-Asturian: ''Principao d'Asturias''), is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in nor ...

, León, and Cantabria

Cantabria (, also , , Cantabrian: ) is an autonomous community in northern Spain with Santander as its capital city. It is called a ''comunidad histórica'', a historic community, in its current Statute of Autonomy. It is bordered on the east ...

(together historically referred to as Gallaecia

Gallaecia, also known as Hispania Gallaecia, was the name of a Roman province in the north-west of Hispania, approximately present-day Galicia (Spain), Galicia, Norte, Portugal, northern Portugal, Asturias and León (province), Leon and the lat ...

and Astures

The Astures or Asturs, also named Astyrs, were the Hispano-Celtic inhabitants of the northwest area of Hispania that now comprises almost the entire modern autonomous community of Principality of Asturias, the modern province of León, and the ...

), covering north-central Portugal and northern Spain—are considered Celtic nations due to their culture and history. Unlike the others, however, no Celtic language has been spoken there in modern times.

Core nations

Each of the six nations has its ownCeltic language

The Celtic languages ( usually , but sometimes ) are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward ...

. In Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, and Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

these have been spoken continuously through time, while Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

and the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = "O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe ...

have languages that were spoken into modern times but later died as spoken community languages. In the latter two regions, however, language revitalisation

Language revitalization, also referred to as language revival or reversing language shift, is an attempt to halt or reverse the decline of a language or to revive an extinct one. Those involved can include linguists, cultural or community groups, o ...

movements have led to the adoption of these languages by adults and produced a number of native speakers.

Ireland, Wales, Brittany and Scotland contain areas where a Celtic language is used on a daily basis; in Ireland these areas are called the ''Gaeltacht

( , , ) are the districts of Ireland, individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The ''Gaeltacht'' districts were first officially recog ...

''; in Wales ''Y Fro Gymraeg

Y Fro Gymraeg (literally 'The Welsh Language Area', pronounced ) is a name often used to refer to the linguistic area in Wales where the Welsh language is used by the majority or a large part of the population; it is the heartland of the Welsh lan ...

,'' Breizh-Izel (Lower Brittany) in western Brittany and Breizh-Uhel (Upper Brittany) in eastern Brittany. Generally these communities are in the west of their countries and in more isolated upland or island areas. Welsh, however, is much more widespread, with much of the north and west speaking it as a first language, or equally alongside English. Public signage is in dual languages throughout Wales and it is now a requirement to possess at least basic Welsh in order to be employed by the Welsh Government

The Welsh Government ( cy, Llywodraeth Cymru) is the Welsh devolution, devolved government of Wales. The government consists of ministers and Minister (government), deputy ministers, and also of a Counsel General for Wales, counsel general. Minist ...

. The term ''Gàidhealtachd

The (; English: ''Gaeldom'') usually refers to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland and especially the Scottish Gaelic-speaking culture of the area. The similar Irish language word refers, however, solely to Irish-speaking areas.

The term ...

'' historically distinguished the Gaelic-speaking areas of Scotland (the Highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Albania

* Dukagjin Highlands

Armenia

* Armenian Highlands

Australia

*Sou ...

and islands) from the Lowland

Upland and lowland are conditional descriptions of a plain based on elevation above sea level. In studies of the ecology of freshwater rivers, habitats are classified as upland or lowland.

Definitions

Upland and lowland are portions of ...

Scots (i.e. Anglo-Saxon-speaking) areas. More recently, this term has also been adopted as the Gaelic name of the Highland council area

Highland ( gd, A' Ghàidhealtachd, ; sco, Hieland) is a council area in the Scottish Highlands and is the largest local government area in the United Kingdom. It was the 7th most populous council area in Scotland at the 2011 census. It share ...

, which includes non-Gaelic speaking areas. Hence, more specific terms such as ''sgìre Ghàidhlig'' ("Gaelic-speaking area") are now used.

In Wales, the Welsh language

Welsh ( or ) is a Celtic language family, Celtic language of the Brittonic languages, Brittonic subgroup that is native to the Welsh people. Welsh is spoken natively in Wales, by some in England, and in Y Wladfa (the Welsh colony in Chubut P ...

is a core curriculum (compulsory) subject, which all pupils study. Additionally, 20% of schoolchildren in Wales attend Welsh medium schools, where they are taught entirely in the Welsh language. In the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. A ...

, all school children study Irish as one of the three core subjects until the end of secondary school, and 7.4% of primary school education is through Irish medium education, which is part of the Gaelscoil

A Gaelscoil (; plural: ''Gaelscoileanna'') is an Irish language-medium school in Ireland: the term refers especially to Irish-medium schools outside the Irish-speaking regions or Gaeltacht. Over 50,000 students attend Gaelscoileanna at primary an ...

movement. In the Isle of Man, there is one Manx-medium primary school, and all schoolchildren have the opportunity to learn Manx.

Other territories

Parts of the northern Iberian Peninsula, namely Galicia,Cantabria

Cantabria (, also , , Cantabrian: ) is an autonomous community in northern Spain with Santander as its capital city. It is called a ''comunidad histórica'', a historic community, in its current Statute of Autonomy. It is bordered on the east ...

, Asturias

Asturias (, ; ast, Asturies ), officially the Principality of Asturias ( es, Principado de Asturias; ast, Principáu d'Asturies; Galician-Asturian: ''Principao d'Asturias''), is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in nor ...

and Northern Portugal

The North Region ( pt, Região do Norte ) or Northern Portugal is the most populous region in Portugal, ahead of Lisbon Region, Lisbon, and the third most extensive by area. The region has 3,576,205 inhabitants according to the 2017 census, and its ...

, also lay claim to this heritage. Musicians from Galicia and Asturias

Asturias (, ; ast, Asturies ), officially the Principality of Asturias ( es, Principado de Asturias; ast, Principáu d'Asturies; Galician-Asturian: ''Principao d'Asturias''), is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in nor ...

have participated in Celtic music festivals, such as the Ortigueira's Festival of Celtic World

Ortigueira, a seaport and borough in County Ferrolterra (A Coruña) in Galicia, celebrates its patron saint day -Saint Martha of Ortigueira's Day- on 29 July.

Held during Saint Martha's day, Ortigueira's Festival of Celtic World (Festival Inter ...

in the village of Ortigueira

Ortigueira is a seaport and municipality in the province of A Coruña (province), A Coruña the autonomous community of Galicia, Spain, Galicia in northwestern Spain. It belongs to the Comarcas of Galicia, comarca of Ortegal. It is located on th ...

or the Breton Festival Interceltique de Lorient

__NOTOC__

The (French), Emvod Ar Gelted An Oriant (Breton) or Inter-Celtic Festival of Lorient in English, is an annual Celtic festival, located in the city of Lorient, Brittany, France. It was founded in 1971 by .

This annual festival takes ...

, which in 2013 celebrated the Year of Asturias, and in 2019 celebrated the Year of Galicia. Northern Portugal, part of ancient Gallaecia

Gallaecia, also known as Hispania Gallaecia, was the name of a Roman province in the north-west of Hispania, approximately present-day Galicia (Spain), Galicia, Norte, Portugal, northern Portugal, Asturias and León (province), Leon and the lat ...

(Galicia, Minho, Douro and Trás-os-Montes), also has traditions quite similar to Galicia. However, no Celtic language has been spoken in northern Iberia since probably the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

.Koch, John T. (2006). "Britonia". In John T. Koch, ''Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia''. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, p. 291.

Irish was once widely spoken on the island of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, but had largely disappeared there by the early 20th century. Vestiges remain in some words found in Newfoundland English, such as scrob for "scratch", and sleveen for "rascal"Language: Irish GaelicNewfoundland and Labrador Heritage website. There are virtually no known fluent speakers of Irish Gaelic in Newfoundland or Labrador today. Knowledge seems to be largely restricted to memorized passages, such as traditional tales and songs.

Canadian Gaelic

Canadian Gaelic or Cape Breton Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig Chanada, or ), often known in Canadian English simply as Gaelic, is a collective term for the dialects of Scottish Gaelic spoken in Atlantic Canada.

Scottish Gaels were settled in Nova Scot ...

dialects of Scottish Gaelic are still spoken by Gaels in other parts of Atlantic Canada, primarily on Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

and adjacent areas of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

. In 2011, there were 1,275 Gaelic speakers in Nova Scotia, and 300 residents of the province considered a Gaelic language to be their "mother tongue".

Patagonian Welsh

Patagonian Welsh (Welsh: ''Cymraeg y Wladfa'') is a variety of the Welsh language spoken in Y Wladfa, the Welsh settlement in Patagonia, Chubut Province

Chubut ( es, Provincia del Chubut, ; cy, Talaith Chubut) is a province in southern Arg ...

is spoken principally in ''Y Wladfa

Y Wladfa (, "The Colony"), also occasionally Y Wladychfa Gymreig (, "The Welsh Settlement"), refers to the establishment of settlements by Welsh immigrants in Patagonia, beginning in 1865, mainly along the coast of the lower Chubut Valley. In ...

'' in the Chubut Province

Chubut ( es, Provincia del Chubut, ; cy, Talaith Chubut) is a province in southern Argentina, situated between the 42nd parallel south (the border with Río Negro Province), the 46th parallel south (bordering Santa Cruz Province), the Andes ra ...

of Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and gl ...

, with sporadic speakers elsewhere in Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

. Estimates of the number of Welsh speakers range from 1,500 to 5,000.

Celtic languages

Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutc ...

language family

A language family is a group of languages related through descent from a common ''ancestral language'' or ''parental language'', called the proto-language of that family. The term "family" reflects the tree model of language origination in hist ...

. SIL Ethnologue

''Ethnologue: Languages of the World'' (stylized as ''Ethnoloɠue'') is an annual reference publication in print and online that provides statistics and other information on the living languages of the world. It is the world's most comprehensi ...

lists six living Celtic languages, of which four have retained a substantial number of native speakers. These are the Goidelic languages

The Goidelic or Gaelic languages ( ga, teangacha Gaelacha; gd, cànanan Goidhealach; gv, çhengaghyn Gaelgagh) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historically ...

(i.e. Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

and Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

, which are both descended from Middle Irish

Middle Irish, sometimes called Middle Gaelic ( ga, An Mheán-Ghaeilge, gd, Meadhan-Ghàidhlig), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old Engli ...

) and the Brittonic languages

The Brittonic languages (also Brythonic or British Celtic; cy, ieithoedd Brythonaidd/Prydeinig; kw, yethow brythonek/predennek; br, yezhoù predenek) form one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic language family; the other is Goidelic. ...

(i.e. Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

and Breton

Breton most often refers to:

*anything associated with Brittany, and generally

** Breton people

** Breton language, a Southwestern Brittonic Celtic language of the Indo-European language family, spoken in Brittany

** Breton (horse), a breed

**Ga ...

, which are both descended from Common Brittonic

Common Brittonic ( cy, Brythoneg; kw, Brythonek; br, Predeneg), also known as British, Common Brythonic, or Proto-Brittonic, was a Celtic language spoken in Britain and Brittany.

It is a form of Insular Celtic, descended from Proto-Celtic, a ...

).

The other two, Cornish (a Brittonic language) and Manx (a Goidelic language), died in modern times with their presumed last native speakers in 1777

Events

January–March

* January 2 – American Revolutionary War – Battle of the Assunpink Creek: American general George Washington's army repulses a British attack by Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis, in a second ...

and 1974

Major events in 1974 include the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis and the resignation of United States President Richard Nixon following the Watergate scandal. In the Middle East, the aftermath of the 1973 Yom Kippur War determined politics; f ...

respectively. For both these languages, however, revitalisation movements have led to the adoption of these languages by adults and children and produced some native speakers.

Taken together, there were roughly one million native speakers of Celtic languages as of the 2000s. In 2010, there were more than 1.4 million speakers of Celtic languages.

The chart below shows the population of each Celtic nation and the number of people in each nation who can speak Celtic languages. The total number of people living in the Celtic nations is 19,596,000 people and, of these, the total number of people who can speak the Celtic languages is approximately 2,818,000 or 14.3%.

Celtic identity

Formal cooperation between the Celtic nations is active in many contexts, including politics, languages, culture, music and sports:

The

Formal cooperation between the Celtic nations is active in many contexts, including politics, languages, culture, music and sports:

The Celtic League

The Celtic League is a pan-Celtic organisation, founded in 1961, that aims to promote modern Celtic identity and culture in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Brittany, Cornwall and the Isle of Man – referred to as the Celtic nations; it places part ...

is an inter-Celtic political organisation, which campaigns for the political, language, cultural and social rights, affecting one or more of the Celtic nations.

Established in 1917, the Celtic Congress

The International Celtic Congress ( br, Ar C'hendalc'h Keltiek, kw, An Guntelles Keltek, gv, Yn Cohaglym Celtiagh, gd, A' Chòmhdhail Cheilteach, ga, An Chomhdháil Cheilteach, cy, Y Gyngres Geltaidd) is a cultural organisation that seeks to ...

is a non-political organisation that seeks to promote Celtic culture and languages and to maintain intellectual contact and close cooperation between Celtic peoples.

Festivals celebrating the culture of the Celtic nations include the Festival Interceltique de Lorient

__NOTOC__

The (French), Emvod Ar Gelted An Oriant (Breton) or Inter-Celtic Festival of Lorient in English, is an annual Celtic festival, located in the city of Lorient, Brittany, France. It was founded in 1971 by .

This annual festival takes ...

(Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

), the Pan Celtic Festival

The Pan Celtic Festival ( ga, Féile Pan Cheilteach) is a Celtic-language music festival held annually in the week following Easter, since its inauguration in 1971. The first Pan Celtic Festival took place in Killarney, County Kerry, Ireland. I ...

(Ireland), CeltFest Cuba (Havana, Cuba), the National Celtic Festival ( Portarlington, Australia), the Celtic Media Festival (showcasing film and television from the Celtic nations), and the Eisteddfod

In Welsh culture, an ''eisteddfod'' is an institution and festival with several ranked competitions, including in poetry and music.

The term ''eisteddfod'', which is formed from the Welsh morphemes: , meaning 'sit', and , meaning 'be', means, a ...

(Wales).

Inter-Celtic music festivals include Celtic Connections

The Celtic Connections festival started in 1994 in Glasgow, Scotland, and has since been held every January. Featuring over 300 concerts, ceilidhs, talks, free events, late night sessions and workshops, the festival focuses on the roots of tra ...

(Glasgow), and the Hebridean Celtic Festival

The Hebridean Celtic Festival (Scottish Gaelic: Fèis Cheilteach Innse Gall) or HebCelt is an international Scottish music festival, which takes place annually in Stornoway on Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. Headliners to date inclu ...

(Stornoway). Due to immigration, a dialect of Scottish Gaelic (Canadian Gaelic

Canadian Gaelic or Cape Breton Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig Chanada, or ), often known in Canadian English simply as Gaelic, is a collective term for the dialects of Scottish Gaelic spoken in Atlantic Canada.

Scottish Gaels were settled in Nova Scot ...

) is spoken by some on Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

in Nova Scotia, while a Welsh-speaking minority exists in the Chubut Province

Chubut ( es, Provincia del Chubut, ; cy, Talaith Chubut) is a province in southern Argentina, situated between the 42nd parallel south (the border with Río Negro Province), the 46th parallel south (bordering Santa Cruz Province), the Andes ra ...

of Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

. Hence, for certain purposes—such as the Festival Interceltique de Lorient

__NOTOC__

The (French), Emvod Ar Gelted An Oriant (Breton) or Inter-Celtic Festival of Lorient in English, is an annual Celtic festival, located in the city of Lorient, Brittany, France. It was founded in 1971 by .

This annual festival takes ...

—Gallaecia

Gallaecia, also known as Hispania Gallaecia, was the name of a Roman province in the north-west of Hispania, approximately present-day Galicia (Spain), Galicia, Norte, Portugal, northern Portugal, Asturias and León (province), Leon and the lat ...

, Asturias

Asturias (, ; ast, Asturies ), officially the Principality of Asturias ( es, Principado de Asturias; ast, Principáu d'Asturies; Galician-Asturian: ''Principao d'Asturias''), is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in nor ...

, and Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

in Nova Scotia are considered three of the ''nine'' Celtic nations.

Competitions are held between the Celtic nations in sports such as rugby union

Rugby union, commonly known simply as rugby, is a close-contact team sport that originated at Rugby School in the first half of the 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand. In its m ...

(Pro14

The United Rugby Championship (URC) is an annual rugby union competition involving professional teams from Ireland, Italy, Scotland, South Africa, and Wales. The current name was adopted in 2021 when the league expanded to include four South Afr ...

—formerly known as the Celtic League), athletics (Celtic Cup) and association football (the Nations Cup—also known as the Celtic Cup).

The Republic of Ireland enjoyed a period of rapid economic growth between 1995 and 2007, leading to the use of the phrase Celtic Tiger

The "Celtic Tiger" ( ga, An Tíogar Ceilteach) is a term referring to the economy of the Republic of Ireland, economy of Ireland from the mid-1990s to the late 2000s, a period of rapid real economic growth fuelled by foreign direct investment. ...

to describe the country. Aspirations for Scotland to achieve a similar economic performance to that of Ireland led the Scotland First Minister

A first minister is any of a variety of leaders of government cabinets. The term literally has the same meaning as "prime minister" but is typically chosen to distinguish the office-holder from a superior prime minister. Currently the title of ' ...

Alex Salmond

Alexander Elliot Anderson Salmond (; born 31 December 1954) is a Scottish politician and economist who served as First Minister of Scotland from 2007 to 2014. A prominent figure on the Scottish nationalist movement, he has served as leader ...

to set out his vision of a Celtic Lion economy for Scotland, in 2007.

Genetic studies

A Y-DNA study by an Oxford University research team in 2006 claimed that the majority of Britons, including many of the English, are descended from a group of tribes which arrived from Iberia around 5000 BC, before the spread of Celtic culture into western Europe. However, three major later genetic studies have largely invalidated these claims, instead showing that haplogroup R1b in western Europe, most common in traditionally Celtic-speaking areas ofAtlantic Europe

Atlantic Europe is a geographical term for the western portion of Europe which borders the Atlantic Ocean. The term may refer to the idea of Atlantic Europe as a cultural unit and/or as a biogeographical region.

It comprises the Atlantic Isles ...

like Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

, would have largely expanded in massive migrations from the Indo-European homeland

The Proto-Indo-European homeland (or Indo-European homeland) was the prehistoric linguistic homeland of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). From this region, its speakers migrated east and west, and went on to form the proto-communities of ...

, the Yamnaya culture

The Yamnaya culture or the Yamna culture (russian: Ямная культура, ua, Ямна культура literal translation, lit. 'culture of pits'), also known as the Pit Grave culture or Ochre Grave culture, was a late Copper Age to ea ...

in the Pontic–Caspian steppe

The Pontic–Caspian steppe, formed by the Caspian steppe and the Pontic steppe, is the steppeland stretching from the northern shores of the Black Sea (the Pontus Euxinus of antiquity) to the northern area around the Caspian Sea. It extends ...

, during the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

along with carriers of Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutc ...

like proto-Celtic

Proto-Celtic, or Common Celtic, is the ancestral proto-language of all known Celtic languages, and a descendant of Proto-Indo-European. It is not attested in writing but has been partly Linguistic reconstruction, reconstructed through the compar ...

. Unlike previous studies, large sections of autosomal DNA were analyzed in addition to paternal Y-DNA

The Y chromosome is one of two sex chromosomes (allosomes) in therian mammals, including humans, and many other animals. The other is the X chromosome. Y is normally the sex-determining chromosome in many species, since it is the presence or abse ...

markers. They detected an autosomal

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosome, allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in au ...

component present in modern Europeans which was not present in Neolithic or Mesolithic Europeans, and which would have been introduced into Europe with paternal lineages R1b and R1a, as well as the Indo-European languages. This genetic component, labelled as "Yamnaya" in the studies, then mixed to varying degrees with earlier Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymous ...

hunter-gatherer or Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

farmer populations already existing in western Europe. Furthermore, a 2016 study also found that Bronze Age remains from Rathlin Island

Rathlin Island ( ga, Reachlainn, ; Local Irish dialect: ''Reachraidh'', ; Scots: ''Racherie'') is an island and civil parish off the coast of County Antrim (of which it is part) in Northern Ireland. It is Northern Ireland's northernmost point. ...

in Ireland dating to over 4,000 years ago were most genetically similar to modern Irish, Scottish and Welsh, and that the core of the genome of insular Celtic populations was established by this time.

In 2015 a genetic study of the United Kingdom showed that there is no unified 'Celtic' genetic identity compared to 'non-Celtic' areas. The 'Celtic' areas of the United Kingdom (Scotland, Northern Ireland, Wales and Cornwall) show the most genetic differences among each other. The data shows that Scottish and Cornish populations share greater genetic similarity with the English than they do with other 'Celtic' populations, with the Cornish in particular being genetically much closer to other English groups than they are to the Welsh or the Scots.

Terminology

The term ''Celtic nations'' derives from thelinguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

studies of the 16th century scholar George Buchanan

George Buchanan ( gd, Seòras Bochanan; February 1506 – 28 September 1582) was a Scottish historian and humanist scholar. According to historian Keith Brown, Buchanan was "the most profound intellectual sixteenth century Scotland produced." ...

and the polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

Edward Lhuyd

Edward Lhuyd FRS (; occasionally written Llwyd in line with modern Welsh orthography, 1660 – 30 June 1709) was a Welsh naturalist, botanist, linguist, geographer and antiquary. He is also named in a Latinate form as Eduardus Luidius.

Life

...

. As Assistant Keeper and then Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology () on Beaumont Street, Oxford, England, is Britain's first public museum. Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house the cabinet of curiosities that Elias Ashmole gave to the University of ...

, Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

(1691–1709), Lhuyd travelled extensively in Great Britain, Ireland and Brittany in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Noting the similarity between the languages of Brittany, Cornwall and Wales, which he called "P-Celtic

The Gallo-Brittonic languages, also known as the P-Celtic languages, are a subdivision of the Celtic languages of Ancient Gaul (both '' celtica'' and '' belgica'') and Celtic Britain, which share certain features. Besides common linguistic in ...

" or Brythonic, the languages of Ireland, the Isle of Man and Scotland, which he called "Q-Celtic

The Celtic languages (usually , but sometimes ) are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward L ...

" or Goidelic

The Goidelic or Gaelic languages ( ga, teangacha Gaelacha; gd, cànanan Goidhealach; gv, çhengaghyn Gaelgagh) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historically ...

, and between the two groups, Lhuyd published ''Archaeologia Britannica: an Account of the Languages, Histories and Customs of Great Britain, from Travels through Wales, Cornwall, Bas-Bretagne, Ireland and Scotland'' in 1707. His ''Archaeologia Britannica'' concluded that all six languages

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of met ...

derived from the same root. Lhuyd theorised that the root language descended from the languages

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of met ...

spoken by the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

tribes of Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

, whom Greek and Roman writers called Celt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

ic. Having defined the languages of those areas as Celtic, the people living in them and speaking those languages became known as Celtic too. There is some dispute as to whether Lhuyd's theory is correct. Nevertheless, the term ''Celtic'' to describe the languages and peoples of Brittany, Cornwall and Wales, Ireland, the Isle of Man and Scotland was accepted from the 18th century and is widely used today.

These areas of Europe are sometimes referred to as the "Celt belt" or "Celtic fringe" because of their location generally on the western edges of the continent, and of the states they inhabit (e.g. Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

is in the northwest of France, Cornwall is in the south west of Great Britain, Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

in western Great Britain and the Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

-speaking parts of Ireland and Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

are in the west of those countries). Additionally, this region is known as the "Celtic Crescent" because of the near crescent

A crescent shape (, ) is a symbol or emblem used to represent the lunar phase in the first quarter (the "sickle moon"), or by extension a symbol representing the Moon itself.

In Hinduism, Lord Shiva is often shown wearing a crescent moon on his ...

shaped position of the nations in Europe.

Endonyms and Celtic exonyms

The Celtic names for each nation in each language illustrate some of the similarity between the languages. Despite differences in orthography, there are many sound and lexical correspondences between the endonyms and exonyms used to refer to the Celtic nations.Territories of the ancient Celts

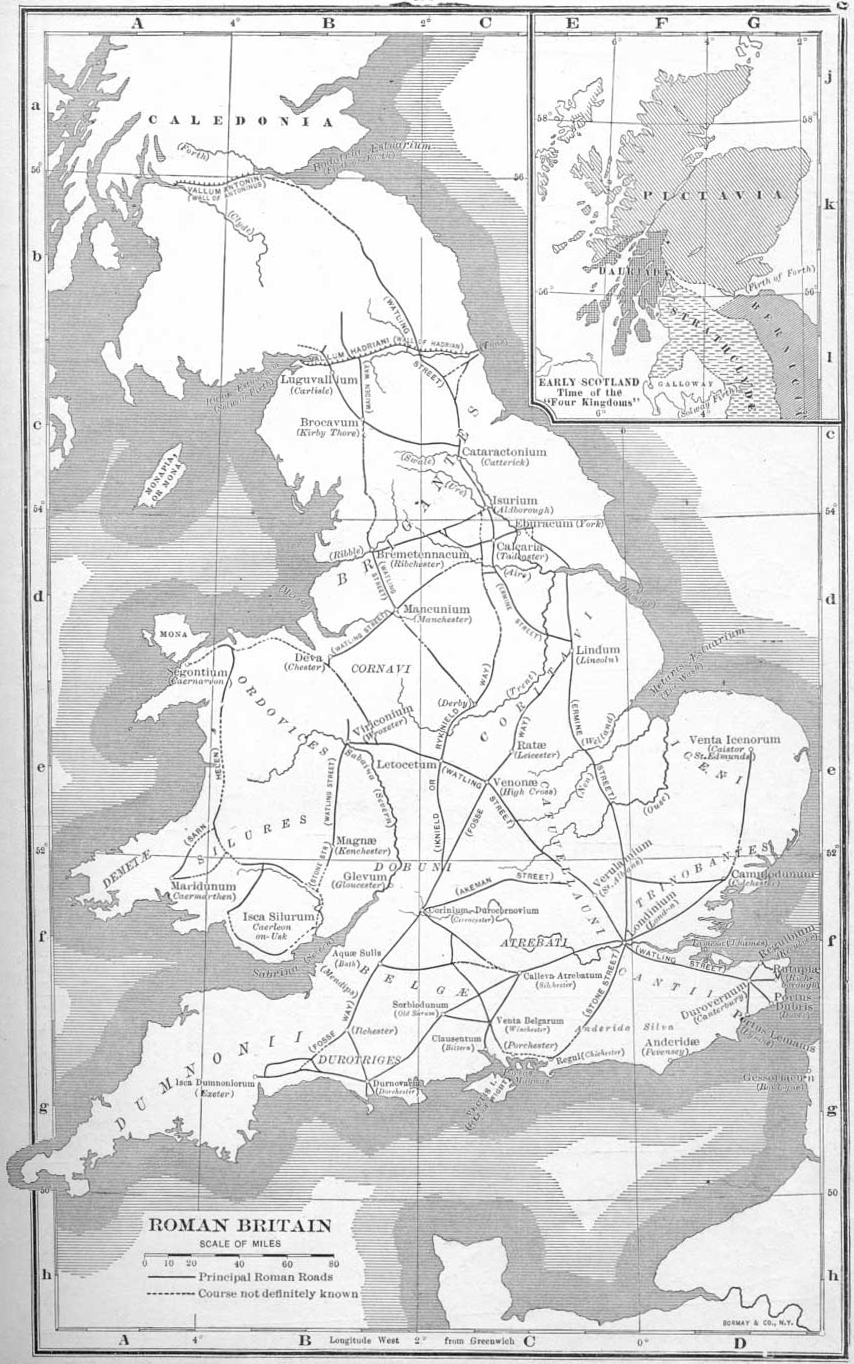

During the

During the European Iron Age

In Europe, the Iron Age is the last stage of the prehistoric period and the first of the protohistoric periods,The Junior Encyclopædia Britannica: A reference library of general knowledge. (1897). Chicago: E.G. Melvin. (seriously? 1897 "Junior ...

, the ancient Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

extended their territory to most of Western and Central Europe and part of Eastern Europe and central Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

.

The Continental Celtic languages

The Continental Celtic languages are the now-extinct group of the Celtic languages that were spoken on the continent of Europe and in central Anatolia, as distinguished from the Insular Celtic languages of the British Isles and Brittany. ''Contine ...

were extinct by the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

, and the continental "Celtic cultural traits", such as oral traditions and practices like the visiting of sacred wells and springs, largely disappeared or, in some cases, were translated. Since they no longer have a living Celtic language, they are not included as 'Celtic nations'. Nonetheless, some of these countries have movements claiming a "Celtic identity".

Iberian Peninsula

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

was an area heavily influenced by Celtic culture, particularly the ancient region of Gallaecia

Gallaecia, also known as Hispania Gallaecia, was the name of a Roman province in the north-west of Hispania, approximately present-day Galicia (Spain), Galicia, Norte, Portugal, northern Portugal, Asturias and León (province), Leon and the lat ...

(about the modern region of Galicia and Braga

Braga ( , ; cel-x-proto, Bracara) is a city and a municipality, capital of the northwestern Portuguese district of Braga and of the historical and cultural Minho Province. Braga Municipality has a resident population of 193,333 inhabitants (in ...

, Viana do Castelo

Viana do Castelo () is a municipality and seat of the district of Viana do Castelo in the Norte Region of Portugal. The population in 2011 was 88,725, in an area of 319.02 km². The urbanized area of the municipality, comprising the city, ...

, Douro

The Douro (, , ; es, Duero ; la, Durius) is the highest-flow river of the Iberian Peninsula. It rises near Duruelo de la Sierra in Soria Province, central Spain, meanders south briefly then flows generally west through the north-west part of ...

, Porto

Porto or Oporto () is the second-largest city in Portugal, the capital of the Porto District, and one of the Iberian Peninsula's major urban areas. Porto city proper, which is the entire municipality of Porto, is small compared to its metropol ...

, and Bragança in Portugal) and the Asturian-Leonese region (Asturias

Asturias (, ; ast, Asturies ), officially the Principality of Asturias ( es, Principado de Asturias; ast, Principáu d'Asturies; Galician-Asturian: ''Principao d'Asturias''), is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in nor ...

, León, Zamora and Salamanca

Salamanca () is a city in western Spain and is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the autonomous community of Castile and León. The city lies on several rolling hills by the Tormes River. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO World Heritag ...

in Spain). Only France and Britain have more ancient Celtic place names than Spain and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

combined (Cunliffe and Koch 2010 and 2012).

Some of the Celtic tribes recorded in these regions by the Romans were the Gallaeci, the Bracari The Bracari or Callaeci Bracari were an ancient Celtic tribe of Gallaecia, living in the northwest of modern Portugal, in the province of Minho, between the rivers Tâmega and Cávado. After the conquest of the region beginning in 136BC, the Ro ...

, the Astures

The Astures or Asturs, also named Astyrs, were the Hispano-Celtic inhabitants of the northwest area of Hispania that now comprises almost the entire modern autonomous community of Principality of Asturias, the modern province of León, and the ...

, the Cantabri

The Cantabri ( grc-gre, Καντάβροι, ''Kantabroi'') or Ancient Cantabrians, were a pre-Ancient Rome, Roman people and large tribal federation that lived in the northern coastal region of ancient Iberia in the second half of the first mille ...

, the Celtici

]

The Celtici (in Portuguese language, Portuguese, Spanish, and Galician languages, ) were a Celtic tribe or group of tribes of the Iberian peninsula, inhabiting three definite areas: in what today are the regions of Alentejo and the Algarve i ...

, the Celtiberians, Celtiberi, the Tumorgogi, Albion and Cerbarci. The Lusitanians

The Lusitanians ( la, Lusitani) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people living in the west of the Iberian Peninsula prior to its conquest by the Roman Republic and the subsequent incorporation of the territory into the Roma ...

are categorised by some as Celts, or at least Celticised, but there remain inscriptions in an apparently non-Celtic Lusitanian language

Lusitanian (so named after the Lusitani or Lusitanians) was an Indo-European Paleohispanic language. There has been support for either a connection with the ancient Italic languages or Celtic languages. It is known from only six sizeable inscri ...

. However, the language had clear affinities with the Gallaecian Celtic language. Modern-day Galicians

Galicians ( gl, galegos, es, gallegos, link=no) are a Celtic-Romance ethnic group from Spain that is closely related to the Portuguese people and has its historic homeland is Galicia, in the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula. Two Romance l ...

, Asturians

Asturians ( ast, asturianos) are a Celtic-Romance ethnic group native to the autonomous community of Asturias, in the North-West of the Iberian Peninsula.

Culture and society Heritage

Asturians are directly descended from the Astures, who wer ...

, Cantabrians and northern Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

claim a Celtic heritage or identity. Although the Celtic cultural traces are as difficult to analyse as in the other former Celtic countries of Europe, because of the extinction of Iberian Celtic languages in Roman times, Celtic heritage is attested in toponymics and language substratum, ancient texts, folklore and music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect ...

. At the end, late Celtic influence is also attributed to the fifth century Romano-Briton colony of Britonia

Britonia (which became Bretoña in Galician and Spanish) is the historical, apparently Latinized name of a Celtic settlement by Romano-Britons on the Iberian peninsula following the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain. The area is roughly analogo ...

in Galicia.

Tenth century Middle Irish

Middle Irish, sometimes called Middle Gaelic ( ga, An Mheán-Ghaeilge, gd, Meadhan-Ghàidhlig), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old Engli ...

mythical history Lebor Gabála Érenn

''Lebor Gabála Érenn'' (literally "The Book of the Taking of Ireland"), known in English as ''The Book of Invasions'', is a collection of poems and prose narratives in the Irish language intended to be a history of Ireland and the Irish fro ...

( ir, Leabhar Gabhála Éireann) credited Gallaecia as the point from where the Gallaic Celts sailed to conquer Ireland.

England

In Celtic languages,

In Celtic languages, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

is usually referred to as "Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

-land" (''Sasana'', ''Pow Sows'', ''Bro-Saoz'' etc.), and in Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

as ''Lloegr'' (though the Welsh translation of English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

also refers to the Saxon route: Saesneg, with the English people being referred to as "Saeson", or "Saes" in the singular). The mildly derogatory Scottish Gaelic term ''Sassenach

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

'' derives from this source. However, spoken Cumbric

Cumbric was a variety of the Common Brittonic language spoken during the Early Middle Ages in the ''Hen Ogledd'' or "Old North" in what is now the counties of Westmorland, Cumberland and northern Lancashire in Northern England and the souther ...

survived until approximately the 12th century, Cornish until the 18th century, and Welsh within the Welsh Marches

The Welsh Marches ( cy, Y Mers) is an imprecisely defined area along the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods.

The English term Welsh March (in Medieval Latin ...

, notably in Archenfield

Archenfield (Old English: ''Ircingafeld'') is the historic English name for an area of southern and western Herefordshire in England. Since the Anglo-Saxons took over the region in the 8th century, it has stretched between the River Monnow and R ...

, now part of Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouthshire ...

, until the 19th century. Both Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in North West England, bordering Scotland. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local government, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. Cumb ...

and Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

were traditionally Brythonic in culture. Cornwall existed as an independent state for some time after the foundation of England, and Cumbria originally retained a great deal of autonomy within the Kingdom of Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

. The unification of the Anglian kingdom of Northumbria with the Cumbric kingdom of Cumbria came about due to a political marriage between the Northumbrian King Oswiu and Queen Riemmelth (''Rhiainfellt'' in Old Welsh

Old Welsh ( cy, Hen Gymraeg) is the stage of the Welsh language from about 800 AD until the early 12th century when it developed into Middle Welsh.Koch, p. 1757. The preceding period, from the time Welsh became distinct from Common Brittonic ...

), a then Princess of Rheged

Rheged () was one of the kingdoms of the ''Hen Ogledd'' ("Old North"), the Brittonic-speaking region of what is now Northern England and southern Scotland, during the post-Roman era and Early Middle Ages. It is recorded in several poetic and b ...

.

Movements of population between different parts of Great Britain over the last two centuries, with industrial development and changes in living patterns such as the growth of second home

Second Home is Marié Digby's second album and first Japanese studio album, released on March 4, 2009.

Track list

Marié Digby albums

2009 albums

{{2000s-pop-rock-album-stub ...

ownership, have greatly modified the demographics of these areas, including the Isles of Scilly

The Isles of Scilly (; kw, Syllan, ', or ) is an archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England. One of the islands, St Agnes, is the most southerly point in Britain, being over further south than the most southerly point of the ...

off the coast of Cornwall, although Cornwall in particular retains Celtic cultural features, and a Cornish self-government movement

Cornish nationalism is a cultural, political and social movement that seeks the recognition of Cornwall – the south-westernmost part of the island of Great Britain – as a nation distinct from England. It is usually based on three gener ...

is well established.

Brythonic and Cumbric placenames are found throughout England but are more common in the West of England than the East, reaching their highest density in the traditionally Celtic areas of Cornwall, Cumbria and the areas of England bordering Wales. Name elements containing Brythonic topographic words occur in many areas of England, such as: ''caer'' 'fort', as in the Cumbrian city of Carlisle; ''pen'' 'hill' as in the Cumbrian town of Penrith and Pendle Hill in Lancashire; ''afon'' 'river' as in the Rivers

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of wate ...

Avon in Warwickshire, Devon and Somerset; and ''mynydd'' 'mountain', as in Long Mynd in Shropshire. The name 'Cumbria

Cumbria ( ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in North West England, bordering Scotland. The county and Cumbria County Council, its local government, came into existence in 1974 after the passage of the Local Government Act 1972. Cumb ...

' is derived from the same root as Cymru, the Welsh name for Wales, meaning 'the land of comrades'.

Formerly Gaulish regions

Most French people identify with the ancient

Most French people identify with the ancient Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They s ...

and are well aware that they were a people that spoke Celtic languages and lived Celtic ways of life. Nowadays, the popular nickname ''Gaulois'', "Gaulish people", is very often used to mean 'stock French people' to make the difference with the descendants of foreigners in France.

Walloons

Walloons (; french: Wallons ; wa, Walons) are a Gallo-Romance ethnic group living native to Wallonia and the immediate adjacent regions of France. Walloons primarily speak '' langues d'oïl'' such as Belgian French, Picard and Walloon. Walloo ...

occasionally characterise themselves as "Celts", mainly in opposition to the "Teutonic" Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

and "Latin" French identities.

Others think they are Belgian, that is to say Germano-Celtic people different from the Gaulish-Celtic French.

The ethnonym

An ethnonym () is a name applied to a given ethnic group. Ethnonyms can be divided into two categories: exonyms (whose name of the ethnic group has been created by another group of people) and autonyms, or endonyms (whose name is created and used ...

"Walloon" derives from a Germanic word meaning "foreign", cognate with the words "Welsh" and "Vlach

"Vlach" ( or ), also "Wallachian" (and many other variants), is a historical term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate mainly Romanians but also Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, Istro-Romanians and other Easter ...

".

The name of Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, home country of the Walloon people, is cognate with the Celtic tribal names Belgae

The Belgae () were a large confederation of tribes living in northern Gaul, between the English Channel, the west bank of the Rhine, and the northern bank of the river Seine, from at least the third century BC. They were discussed in depth by Ju ...

and (possibly) the Irish legendary Fir Bolg

In medieval Irish myth, the Fir Bolg (also spelt Firbolg and Fir Bholg) are the fourth group of people to settle in Ireland. They are descended from the Muintir Nemid, an earlier group who abandoned Ireland and went to different parts of Europe. ...

.

Italian Peninsula

The Canegrate culture (13th century BC) may represent the first migratory wave of the proto-Celtic population from the northwest part of the Alps that, through theAlpine passes This article lists the principal mountain passes and tunnels in the Alps, and gives a history of transport across the Alps.

Main passes

The following are the main paved road passes across the Alps. Main indicates on the main chain of the Alps, fr ...

, had already penetrated and settled in the western Po valley between Lake Maggiore

Lake Maggiore (, ; it, Lago Maggiore ; lmo, label=Western Lombard, Lagh Maggior; pms, Lagh Magior; literally 'Greater Lake') or Verbano (; la, Lacus Verbanus) is a large lake located on the south side of the Alps. It is the second largest la ...

and Lake Como

Lake Como ( it, Lago di Como , ; lmo, label=Western Lombard, Lagh de Còmm , ''Cómm'' or ''Cùmm'' ), also known as Lario (; after the la, Larius Lacus), is a lake of glacial origin in Lombardy, Italy. It has an area of , making it the thir ...

(Scamozzina culture

The Scamozzina culture (Italian ''Cultura della Scamozzina''), which takes its name from the necropolis found in Cascina Scamozzina of Albairate, was a prehistoric civilization of Italy that developed between the end of the middle Bronze Age and ...

). It has also been proposed that a more ancient proto-Celtic presence can be traced back to the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

(16th–15th century BC), when North Westwern Italy appears closely linked regarding the production of bronze artifacts, including ornaments, to the western groups of the Tumulus culture

__NOTOC__

The Tumulus culture (German::de:Mittlere Bronzezeit, ''Hügelgräberkultur'') dominated Central Europe during the European Bronze Age, Middle Bronze Age ( 1600 to 1300 BC).

It was the descendant of the Unetice culture. Its heartl ...

(Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the area' ...

, 1600–1200 BC). La Tène cultural material appeared over a large area of mainland Italy, the southernmost example being the Celtic helmet from Canosa di Puglia

Canosa di Puglia, generally known simply as Canosa ( nap, label= Canosino, Canaus), is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Barletta-Andria-Trani, Apulia, southern Italy. It is located between Bari and Foggia, on the northwestern edge of the ...

.

Italy is home to the Lepontic

Lepontic is an ancient Alpine Celtic languageJohn T. Koch (ed.) ''Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia'' ABC-CLIO (2005) that was spoken in parts of Rhaetia and Cisalpine Gaul (now Northern Italy) between 550 and 100 BC. Lepontic is atte ...

, the oldest attested Celtic language (from the 6th century BC). Anciently spoken in Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

and in Northern-Central Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, from the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

to Umbria

it, Umbro (man) it, Umbra (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, ...

. According to the ''Recueil des Inscriptions Gauloises'', more than 760 Gaulish inscriptions have been found throughout present-day France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

—with the notable exception of Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 January ...

—and in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, which testifies the importance of Celtic heritage in the peninsula.

The French- and Arpitan-speaking Aosta Valley

, Valdostan or Valdotainian it, Valdostano (man) it, Valdostana (woman)french: Valdôtain (man)french: Valdôtaine (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title = Official languages

, population_blank1 = Italian French

...

region in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

also presents a claim of Celtic heritage.

The Northern League autonomist

Autonomism, also known as autonomist Marxism is an anti-capitalist left-wing political and social movement and theory. As a theoretical system, it first emerged in Italy in the 1960s from workerism (). Later, post-Marxist and anarchist tend ...

party often exalts what it claims are the Celtic roots of all Northern Italy

Northern Italy ( it, Italia settentrionale, it, Nord Italia, label=none, it, Alta Italia, label=none or just it, Nord, label=none) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. It consists of eight administrative regions ...

or Padania

Padania (, also , ) is an alternative name and proposed independent state encompassing Northern Italy, derived from the name of the Po River (Latin ''Padus''), whose basin includes much of the region, centered on the Po Valley (), the major plai ...

.

Reportedly, Friuli

Friuli ( fur, Friûl, sl, Furlanija, german: Friaul) is an area of Northeast Italy with its own particular cultural and historical identity containing 1,000,000 Friulians. It comprises the major part of the autonomous region Friuli Venezia Giulia ...

also has a claim to Celticity (recent studies have estimated that about 1/10 of Friulian words are of Celtic origin; also, a lot of typical Friulian traditions, dances, songs and mythology are remnants of the culture of Carnian tribes who lived in this area during the Roman age and the early Middle Ages. Some Friuli

Friuli ( fur, Friûl, sl, Furlanija, german: Friaul) is an area of Northeast Italy with its own particular cultural and historical identity containing 1,000,000 Friulians. It comprises the major part of the autonomous region Friuli Venezia Giulia ...

ans consider themselves and their region as one of the Celtic Nations)

Central and Eastern European regions

Celtic tribes inhabited land in what is now southern Germany and Austria. Many scholars have associated the earliest Celtic peoples with theHallstatt culture

The Hallstatt culture was the predominant Western Europe, Western and Central European Archaeological culture, culture of Late Bronze Age Europe, Bronze Age (Hallstatt A, Hallstatt B) from the 12th to 8th centuries BC and Early Iron Age Europe ...

. The Boii

The Boii (Latin plural, singular ''Boius''; grc, Βόιοι) were a Celtic tribe of the later Iron Age, attested at various times in Cisalpine Gaul (Northern Italy), Pannonia (Hungary), parts of Bavaria, in and around Bohemia (after whom the ...

, the Scordisci

The Scordisci ( el, Σκορδίσκοι) were a Celtic Iron Age cultural group centered in the territory of present-day Serbia, at the confluence of the Savus (Sava), Dravus (Drava), Margus (Morava) and Danube rivers. They were historically n ...

, and the Vindelici

The Vindelici (Gaulish: ) were a Gallic people dwelling around present-day Augsburg (Bavaria) during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Name

They are mentioned as by Horace (1st c. BC), as (; var. ) by Strabo (early 1st c. AD), as and (va ...

are some of the tribes that inhabited Central Europe, including what is now Slovakia, Serbia, Croatia, Poland and the Czech Republic as well as Germany and Austria. The Boii gave their name to Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

. The Boii founded a city on the site of modern Prague, and some of its ruins are now a tourist attraction. There are claims among modern Czechs that the Czech people are as much descendants of the Boii as they are from the later Slavic invaders (as well as the historical Germanic peoples of Czech lands). This claim may not only be political: according to a 2000 study by Semino, 35.6% of Czech males have y-chromosome haplogroup R1b, which is common among Celts but rare among Slavs.

Celts also founded Singidunum

Singidunum ( sr, Сингидунум/''Singidunum'') was an ancient city which later evolved into modern Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. The name is of Celts, Celtic origin, going back to the time when Celtic tribe Scordisci settled the area in ...

near present-day Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

, though the Celtic presence in modern-day Serbian regions is limited to the far north (mainly including the historically at least partially Hungarian Vojvodina

Vojvodina ( sr-Cyrl, Војводина}), officially the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, is an autonomous province that occupies the northernmost part of Serbia. It lies within the Pannonian Basin, bordered to the south by the national capital ...

).

The modern-day capital of Turkey, Ankara

Ankara ( , ; ), historically known as Ancyra and Angora, is the capital of Turkey. Located in the central part of Anatolia, the city has a population of 5.1 million in its urban center and over 5.7 million in Ankara Province, maki ...

, was once the center of the Celtic culture in Central Anatolia, giving the name to the region—Galatia

Galatia (; grc, Γαλατία, ''Galatía'', "Gaul") was an ancient area in the highlands of central Anatolia, roughly corresponding to the provinces of Ankara and Eskişehir, in modern Turkey. Galatia was named after the Gauls from Thrace (c ...

.

The La Tène culture

The La Tène culture (; ) was a European Iron Age culture. It developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from about 450 BC to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC), succeeding the early Iron Age Hallstatt culture without any defini ...

—named for a region in modern Switzerland—succeeded the Halstatt era in much of central Europe.

Celtic diaspora