Campsey Priory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Campsey Priory, (''Campesse'', ''Kampessie'', etc.), was a religious house of

The

The  There are various evidences that, in this aristocratic house, the language of use was

There are various evidences that, in this aristocratic house, the language of use was

The last prioress of Campsey, Elizabeth Buttry, has her own special place in the priory's history. She had been a member of the community since before 1492, and like the others had raised no complaints when the bishop came. It is suggested that she was a descendant of the Lords of Botreaux, as that name was pronounced. In the Bishop's visitation, 27 June 1526, Barbara Jernyngham was her subprioress, and Margaret Harman, precentrix, went so far as to say that in 35 years she had never known anything to need correction except that the books in the choir might be mended. The prioress and her twenty nuns, who all said ''omnia bene'', were told to mend the books and increase the number of nuns as far as possible.

By 1532, however, there were only 18 inmates, and the story had changed. Barbara Jernyngham was no longer sub-prioress, and said that all was well, as did Petronilla Felton, infirmarer and cellarer. But a chorus of voices complained that the prioress, while generous with her visitors, was very stingy towards the nuns, especially with their food. One had been kept waiting two hours for her dinner: several complained that the meat was unhealthy, and Katerina Grome said that if the bullock they had been fed had not been killed for the table it would have died anyway. For her part, the prioress remarked that the nuns spoke privately with the laity, to which Elizabeth Wingfield, chamberlain, responded that they were all forbidden to speak even to a graduate of the university, unless all were assembled together, and that her office was owed £5. Also that the nuns were not being paid their annual allowance of 6s 8d. from the bequest of William de Ufford.

The last prioress of Campsey, Elizabeth Buttry, has her own special place in the priory's history. She had been a member of the community since before 1492, and like the others had raised no complaints when the bishop came. It is suggested that she was a descendant of the Lords of Botreaux, as that name was pronounced. In the Bishop's visitation, 27 June 1526, Barbara Jernyngham was her subprioress, and Margaret Harman, precentrix, went so far as to say that in 35 years she had never known anything to need correction except that the books in the choir might be mended. The prioress and her twenty nuns, who all said ''omnia bene'', were told to mend the books and increase the number of nuns as far as possible.

By 1532, however, there were only 18 inmates, and the story had changed. Barbara Jernyngham was no longer sub-prioress, and said that all was well, as did Petronilla Felton, infirmarer and cellarer. But a chorus of voices complained that the prioress, while generous with her visitors, was very stingy towards the nuns, especially with their food. One had been kept waiting two hours for her dinner: several complained that the meat was unhealthy, and Katerina Grome said that if the bullock they had been fed had not been killed for the table it would have died anyway. For her part, the prioress remarked that the nuns spoke privately with the laity, to which Elizabeth Wingfield, chamberlain, responded that they were all forbidden to speak even to a graduate of the university, unless all were assembled together, and that her office was owed £5. Also that the nuns were not being paid their annual allowance of 6s 8d. from the bequest of William de Ufford.

Augustinian Augustinian may refer to:

*Augustinians, members of religious orders following the Rule of St Augustine

*Augustinianism, the teachings of Augustine of Hippo and his intellectual heirs

*Someone who follows Augustine of Hippo

* Canons Regular of Sain ...

canonesses

Canoness is a member of a religious community of women living a simple life. Many communities observe the monastic Rule of St. Augustine. The name corresponds to the male equivalent, a canon. The origin and Rule are common to both. As with the c ...

at Campsea Ashe

Campsea Ashe (sometimes spelt Campsey Ash) is a village in Suffolk, England located approximately north east of Woodbridge, Suffolk, Woodbridge and south west of Saxmundham.

The village is served by Wickham Market railway station on the Ipswic ...

, Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include Lowes ...

, about 1.5 miles (2.5 km) south east of Wickham Market

Wickham Market is a large village and electoral ward situated in the River Deben valley of Suffolk, England, within the Suffolk Coastal heritage area.

It is on the A12 trunk road north-east of the county town of Ipswich, north-east of Wood ...

. It was founded shortly before 1195 on behalf of two of his sisters by Theobald de Valoines (died 1209), who, with his wife Avice, had previously founded Hickling Priory

Hickling Priory was an Augustinian priory located in Norfolk, England.

The house was founded in 1185 by Theobald, grandson of Theobald de Valognes, Lord of Parham. By 1291 the Priory had possession of thirty two Norfolk parishes and held an annu ...

in Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

for male canons in 1185. Both houses were suppressed in 1536.

Campsey Priory was one of a group of monasteries in south-east Suffolk with interconnected histories, associated with the family of the elder Theobald de Valoines (''Valognes'', ''Valeines'' etc.), Lord of Parham ( fl. 1135). These include Butley Priory

Butley Priory, sometimes called ''Butley Abbey'', was a religious house of Canons regular (Augustinians, Black canons) in Butley, Suffolk, dedicated to The Blessed Virgin Mary. It was founded in 1171 by Ranulf de Glanville (c. 1112-1190), Chief ...

(founded 1171) and Leiston Abbey

Leiston Abbey outside the town of Leiston, Suffolk, England, was a religious house of Canons Regular following the Premonstratensian rule (White canons), dedicated to Mary, mother of Jesus, St Mary. Founded in c. 1183 by Ranulf de Glanville (c. 11 ...

(1182–83), both founded by his son-in-law Ranulf de Glanville, Chief Justiciar

Justiciar is the English form of the medieval Latin term ''justiciarius'' or ''justitiarius'' ("man of justice", i.e. judge). During the Middle Ages in England, the Chief Justiciar (later known simply as the Justiciar) was roughly equivalent ...

of England, husband of his daughter Bertha. Her sister Matilda was mother of Hubert Walter, Theobald Walter and Osbert fitzHervey. The founder of Campsey Priory was the son of Robert de Valoines and heir to the estate of Parham. During the 14th century the priory enjoyed the special patronage of the de Ufford Earls of Suffolk and their family. Maud of Lancaster, Countess of Ulster

Maud of Lancaster, Countess of Ulster (c. 1310 – 5 May 1377) was an English noblewoman and the wife of William Donn de Burgh, 3rd Earl of Ulster. She was the mother of Elizabeth de Burgh, ''suo jure'' Countess of Ulster. Her second husband w ...

was a commanding presence, by whose efforts Bruisyard Abbey

The Abbey of Bruisyard was a house of Minoresses (Poor Clares) at Bruisyard in Suffolk. It was founded from Campsey Priory in Suffolk on the initiative of Maud of Lancaster, Countess of Ulster, assisted by her son-in-law Lionel of Antwerp, in 136 ...

was established from Campsey.

Much of the fabric of the priory was plundered after the suppression or incorporated into later buildings, but some remains were recorded during the 18th century. The site is now a private residence and not accessible to the public. Occasional excavations have been conducted. A very extensive list of documentary sources is given by Bishop Tanner; additional grants and other documents are held in the Suffolk Records, and some early books associated with the priory survive.

Foundation

The founder succeeded to his father Robert de Valoines in 1178. Before 1195 he gave all his land at Campsey to his sisters Joan and Agnes de Valoines to build there a house for themselves and other religious women, to be dedicated to Mary the mother of God. Gilbert Pecche, who succeeded his father Hamon as a fee-lord in Suffolk after 1191, confirmed the grant. These (lost) grants were confirmed by King John in January 1203/04 to Joan and Agnes and their successors. Theobald died in c. 1209 leaving an heir Thomas, who joined the Barons against King John and briefly had his lands confiscated. The site chosen was a secluded spot with direct river and road access to important centres nearby, and plentiful natural resources. Skirting betweenWickham Market

Wickham Market is a large village and electoral ward situated in the River Deben valley of Suffolk, England, within the Suffolk Coastal heritage area.

It is on the A12 trunk road north-east of the county town of Ipswich, north-east of Wood ...

and Lower Hacheston, where the Rivers Deben and Ore (a tributary of the Alde, passing Parham) are barely a mile apart, the freshwater channel of the Deben turns south and meanders through a broad valley of water-meadows past Rendlesham

Rendlesham is a village and civil parish near Woodbridge, Suffolk, United Kingdom. It was a royal centre of authority for the king of the East Angles, of the Wuffinga line; the proximity of the Sutton Hoo ship burial may indicate a connection ...

and Pettistree

Pettistree is a small village and a civil parish in the East Suffolk district, in the English county of Suffolk. According to the 2011 Census, Pettistree had a population of 194 people and is set in around 1,800 acres of farmland. The village ...

to the lower crossing at Ufford. The priory was located at a higher crossing, on the east bank of the river, at the foot of the land sloping down through Ash and Loudham on the Campsea side. To its north the river flowed into a meare

Meare is a village and civil parish north west of Glastonbury on the Somerset Levels, in the Mendip district of Somerset, England. The parish includes the village of Westhay.

History

Meare is a marshland village in typical Somerset "rhyne" coun ...

before issuing past the priory and its adjacent watermill

A watermill or water mill is a mill that uses hydropower. It is a structure that uses a water wheel or water turbine to drive a mechanical process such as milling (grinding), rolling, or hammering. Such processes are needed in the production of ...

.

Prioress Joan de Valoines

Theobald's sisters built the priory at Campsey and established the community there with Joan de Valoines as the first prioress. The priory was in existence by November 1195 when John Lestrange, in a final concord with Robert de Mortimer, noted that with Robert's approval he had already given the church of Tottington, Norfolk, in free and perpetual alms to the church of the Blessed Mary at Campsey and to the nuns serving God there. At Tottington, birthplace ofSamson

Samson (; , '' he, Šīmšōn, label= none'', "man of the sun") was the last of the judges of the ancient Israelites mentioned in the Book of Judges (chapters 13 to 16) and one of the last leaders who "judged" Israel before the institution o ...

, Abbot of Bury St Edmunds (1182–1211), the Priory always held some title: the advowson

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living, ...

was quitclaimed to Prioress Joan in 1211, and she asserted her title further in 1219. Thomas de Valoines granted various lands at Parham to Joan for the priory in 1221, and an All Hallows fair at Hacheston

Hacheston is a village and a civil parish in the East Suffolk district, in the English county of Suffolk. The population of the parish at the 2011 census was 345.

It is located on the B1116 road between the towns of Wickham Market and Framlingha ...

, beside Parham, was granted to Hickling Priory in 1226. In 1228 Joan released the priory's manor of Helmingham

Helmingham is a village and civil parish in the Mid Suffolk district of Suffolk in eastern England, 12 miles (20 km) east of Stowmarket, and 12 miles north (20 km) of Ipswich. It has a population of 170, increasing to 186 at the 2011 C ...

to Bartholomew de Creke, whose sister Isabel was the mother of Thomas's heir, Robert de Valoines. Thomas was apparently living in 1230.

Joan's long rule culminated in 1228–1230 in a dispute with Prior Adam of Butley Priory

Butley Priory, sometimes called ''Butley Abbey'', was a religious house of Canons regular (Augustinians, Black canons) in Butley, Suffolk, dedicated to The Blessed Virgin Mary. It was founded in 1171 by Ranulf de Glanville (c. 1112-1190), Chief ...

over the right to the tithes

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more ...

of Dilham

Dilham is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. The village is located 4.3 miles south-east of North Walsham and 12 miles north-east of Norwich, and is situated on the River Ant.

History

Dilham's name is of Anglo-Saxon ...

church and mill in Norfolk. First the Abbot of St Benet's at Hulme (Norfolk) and other papal commissioners judged in Butley's favour. The prioress appealed to Rome against the decision, which caused the commissioners to declare the Prioress and Priory of Campsey excommunicate

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

. The Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

referred her appeal to the Prior of Anglesey Priory (Cambridgeshire) and others, who would not carry out the excommunication. Butley Priory obtained papal letters to the Prior of Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth (), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside town and unparished area in, and the main administrative centre of, the Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. A pop ...

(Norfolk) and others to have it enforced. The prioress pleaded that, since she had appealed before the order of excommunication, she and every excommunicated person had the right to defend themselves, and that the Prior of Anglesey's commission had acted rightly in refusing to implement it. The Prior of Yarmouth's commission would not accept this plea, and the Prioress again appealed to Rome. The whole matter was then referred to the Dean of Lincoln

The Dean of Lincoln is the head of the Chapter of Lincoln Cathedral in the city of Lincoln, England in the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln. Christine Wilson was installed as Dean on 22 October 2016.

(William de Thornaco

William de Thornaco was a Priest in the Roman Catholic Church.

Career

He was Archdeacon of Stow, first in or around 27 February 1214 followed by Archdeacon of Lincoln in which office he appears by 22 May 1219.

He was a Dean of Lincoln and a Pr ...

) and the Archdeacons of Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

and Stowe

Stowe may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

*Stowe, Buckinghamshire, a civil parish and former village

**Stowe House

**Stowe School

* Stowe, Cornwall, in Kilkhampton parish

* Stowe, Herefordshire, in the List of places in Herefordshire

* Stowe, Linc ...

, and in June 1230 the original order allocating the tithes to Butley Priory was enforced.

Patrons and prioresses

Joan's sister Agnes had become prioress by 1234, when Hamo de Valoines represented her in a land transaction. Hamo also witnessed grants to the priory by Stephen and William de Ludham, in the hamlet of Loudham inPettistree

Pettistree is a small village and a civil parish in the East Suffolk district, in the English county of Suffolk. According to the 2011 Census, Pettistree had a population of 194 people and is set in around 1,800 acres of farmland. The village ...

. Robert de Valoines was however the heir of Thomas, succeeding to his knight-service

Knight-service was a form of feudal land tenure under which a knight held a fief or estate of land termed a knight's fee (''fee'' being synonymous with ''fief'') from an overlord conditional on him as tenant performing military service for his ov ...

at Richmond Castle

Richmond Castle in Richmond, North Yorkshire, England, stands in a commanding position above the River Swale, close to the centre of the town of Richmond. It was originally called Riche Mount, 'the strong hill'. The castle was constructed by Ala ...

owing from Parham. He married Roisia (younger sister of William le Blund) before 1247, when their son Robert the younger was born. The Campsey nuns opposed Robert's claim to be their patron. Some time between 1244 and 1257 he came to an agreement with them, by which they accepted Robert and his heirs as their patrons, and he in turn assured their right to elect their own prioress, who should be presented to him for approval, and renounced any right to sell off their lands while he had wardship during a vacancy. Roger Bigod, 4th Earl of Norfolk

Roger Bigod (c. 1209–1270) was 4th Earl of Norfolk and Marshal of England.

Origins

He was the eldest son and heir of Hugh Bigod, 3rd Earl of Norfolk (1182-1225) by his wife Maud, a daughter of William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke (1147-1219 ...

and Hugh Bigod witnessed their settlement. In 1258 Prioress Basilia (de Wachisham) received a grant of property in Burgate

Burgate is a small village and civil parish in the Mid Suffolk district of Suffolk, England, about south-west of Diss in Norfolk. The church, dedicated to St Mary and dating from the 14th century, was restored in 1864 and is a Grade II* listed ...

.

Robert de Valoines died in or before 1268 leaving an heir Robert the younger, who married Eva, widow of Nicholas Tregoz of Tolleshunt D'Arcy in Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

. At about this time Margery, daughter of Sir Gilbert Pecche (d. 1291), married Nicholas de Crioll the younger, hereditary patron of Butley Priory and Leiston Abbey. He in his father's lifetime bestowed those rights upon Margery with the manor of Benhall, in dower

Dower is a provision accorded traditionally by a husband or his family, to a wife for her support should she become widowed. It was settled on the bride (being gifted into trust) by agreement at the time of the wedding, or as provided by law.

...

. Meanwhile, the prioress of Campsey was bringing pleas in 1273–1277 against Humphrey de Bohun, Earl of Essex, and Henry de Bohun for annual rents from Nuthampstead

Nuthampstead is a small village and civil parish in North East Hertfordshire located a few miles south of the town of Royston. In the 2001 census the parish had 139 residents, increasing to 142 at the 2011 Census.

Nuthampstead was historically ...

in Hertfordshire. Robert and Eva de Valoines had two daughters, Roisia (c.1279) and Cecily (c. 1280). These infants became his heirs when he died in 1281. Eva, a cousin of King Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal o ...

, survived her second husband and had for her dower the manors of Tolleshunt Tregoz and Bluntishall (Blunt's Hall, Witham

Witham () is a town in the county of Essex in the East of England, with a population ( 2011 census) of 25,353. It is part of the District of Braintree and is twinned with the town of Waldbröl, Germany. Witham stands between the city of Che ...

) by the king's command. Cecily was heir to Campsey Priory.

The priory environment

The construction of the priory church and conventual buildings is likely to have proceeded through the early 13th century. In the late 18th century, when various ruins were visible, a plan was attempted suggesting acloister

A cloister (from Latin ''claustrum'', "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church, commonly against a ...

yard measuring some 78 feet north to south and some 70 feet west to east, taking into account the width of a passage on the east side which presumably entered into the cloister walk. Substantial remains of the west range then existed (with large buttress

A buttress is an architectural structure built against or projecting from a wall which serves to support or reinforce the wall. Buttresses are fairly common on more ancient buildings, as a means of providing support to act against the lateral (s ...

es on its west side) which still partially survives in a converted barn structure which includes an early doorway at the northern end of its east (cloister-side) front. It also shows part of a string course

A belt course, also called a string course or sill course, is a continuous row or layer of stones or brick set in a wall. Set in line with window sills, it helps to make the horizontal line of the sills visually more prominent. Set between the ...

forming the creasing of a lean-to roof for the cloister walkway.

The

The nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

of the priory church ran as usual along the north side of the cloister, but the plan includes no evidence of the choir

A choir ( ; also known as a chorale or chorus) is a musical ensemble of singers. Choral music, in turn, is the music written specifically for such an ensemble to perform. Choirs may perform music from the classical music repertoire, which ...

. Excavations in 1970 confirmed the position of the north-east corner of the cloister where the passage entered the church, and part of an aisle

An aisle is, in general, a space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, certain types of buildings, such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, parl ...

chapel on the south side of the choir. An important series of tiles was found, including examples of the embossed relief tiles of the type associated with the early 13th century phase of building at Butley Priory

Butley Priory, sometimes called ''Butley Abbey'', was a religious house of Canons regular (Augustinians, Black canons) in Butley, Suffolk, dedicated to The Blessed Virgin Mary. It was founded in 1171 by Ranulf de Glanville (c. 1112-1190), Chief ...

nearby. The east range was largely indeterminable. The south range (marked "Chapel of St Mary" on the plan) was evidently the refectory

A refectory (also frater, frater house, fratery) is a dining room, especially in monasteries, boarding schools and academic institutions. One of the places the term is most often used today is in graduate seminaries. The name derives from the La ...

or frater, and survived to some height in 1785. A watercolour by Isaac Johnson shows a series of tall arched windows likely to belong to this building, and the plan indicates a corridor and steps leading up to the frater lectern

A lectern is a reading desk with a slanted top, on which documents or books are placed as support for reading aloud, as in a scripture reading, lecture, or sermon. A lectern is usually attached to a stand or affixed to some other form of support. ...

podium

A podium (plural podiums or podia) is a platform used to raise something to a short distance above its surroundings. It derives from the Greek ''πόδι'' (foot). In architecture a building can rest on a large podium. Podiums can also be used ...

on the south side.

There are various evidences that, in this aristocratic house, the language of use was

There are various evidences that, in this aristocratic house, the language of use was Anglo-Norman Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

* Anglo-Norman language

**Anglo-Norman literature

* Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 10 ...

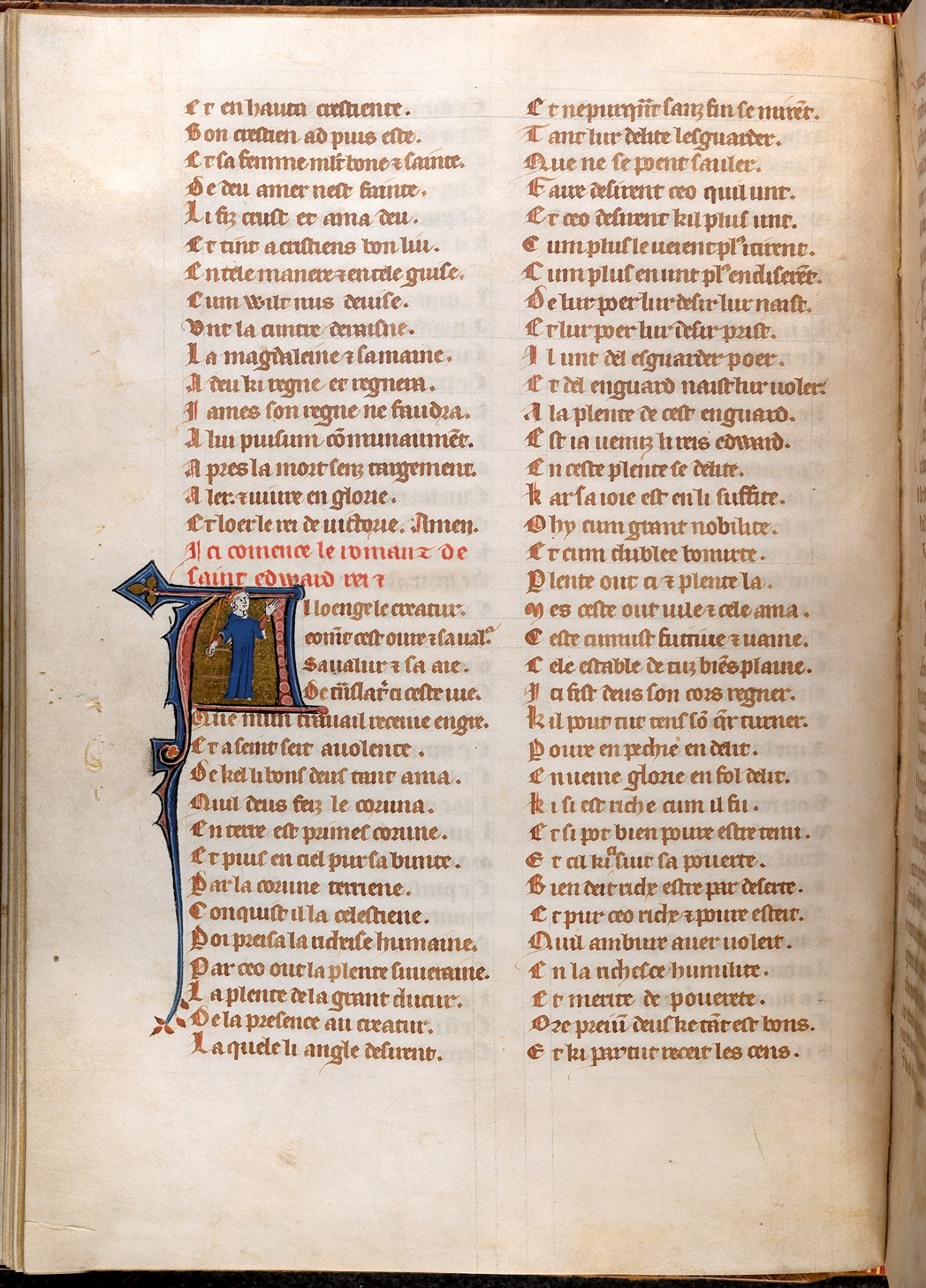

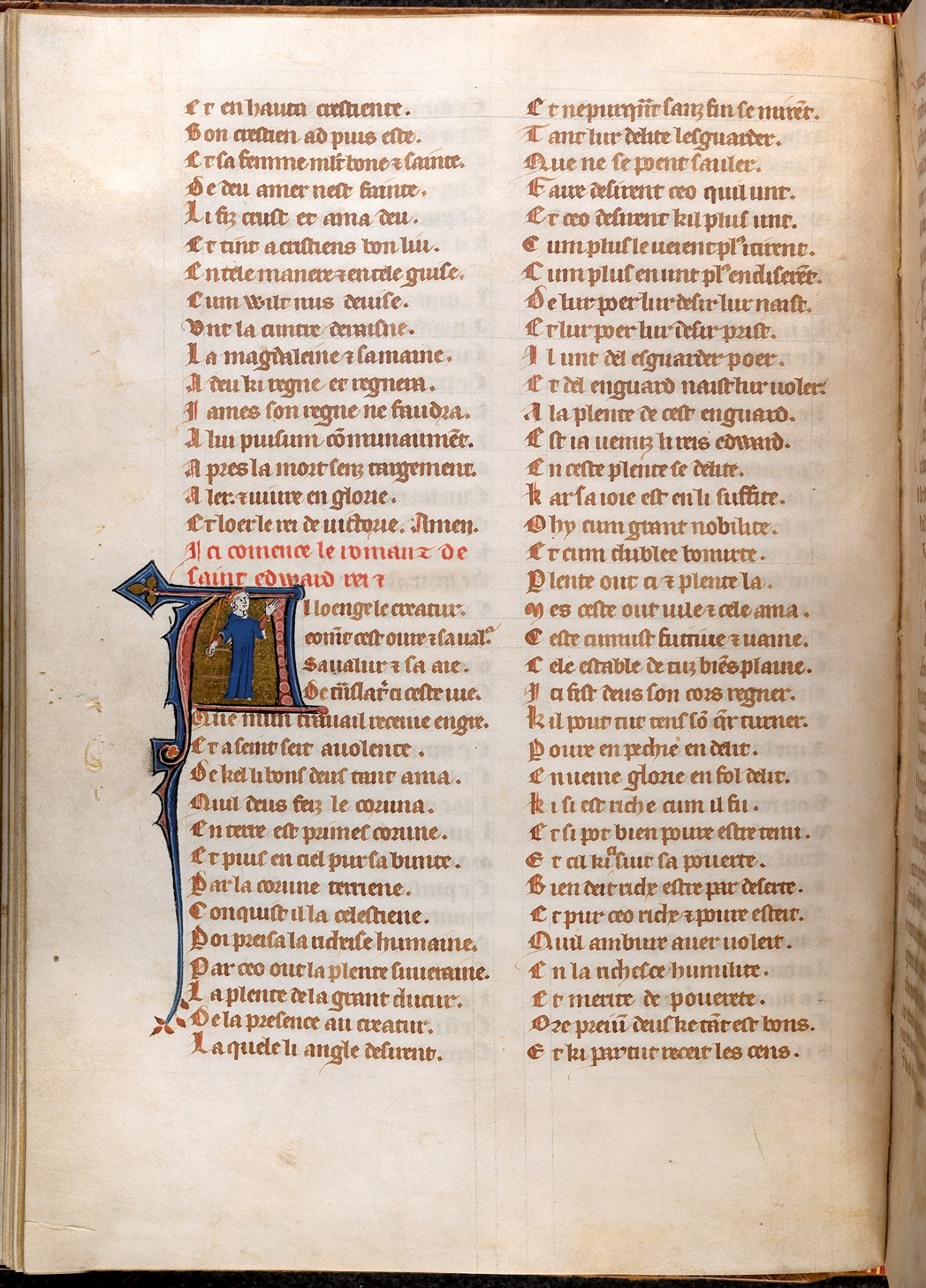

. An important book inscribed ''Cest livere est a covent de Campisse'' is a large volume of Saints' Lives

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian hagiographies might ...

in Anglo-Norman verse (known as the "Campsey Manuscript"). This was used for mealtime readings in the Campsey refectory. The main part of the book contains ''Lives'' of Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English nobleman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then ...

(by Guernes de Pont-Sainte-Maxence Guernes de Pont-Sainte-Maxence, also known as Garnier, was a 12th-century French scribe and one of the ten contemporary biographers of Saint Thomas Becket of Canterbury.

Life

All that we know about Guernes is what he tells us, directly or indirec ...

), Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor ; la, Eduardus Confessor , ; ( 1003 – 5 January 1066) was one of the last Anglo-Saxon English kings. Usually considered the last king of the House of Wessex, he ruled from 1042 to 1066.

Edward was the son of Æth ...

, Archbishop Edmund Rich, St Etheldreda, St Osyth, St Faith

Saint Faith or Saint Faith of Conques (Latin: Sancta Fides; French language, French: Sainte-Foy; Spanish language, Spanish: Santa Fe) is a saint who is said to have been a girl or young woman of Agen in Aquitaine. Her legend recounts how she was ...

, St Modwenna, Richard de Wych and the Life of St Catherine by Clemence of Barking. Appended to this are ''Lives'' of St Elizabeth of Hungary

Elizabeth of Hungary (german: Heilige Elisabeth von Thüringen, hu, Árpád-házi Szent Erzsébet, sk, Svätá Alžbeta Uhorská; 7 July 1207 – 17 November 1231), also known as Saint Elizabeth of Thuringia, or Saint Elisabeth of Thuringia, ...

, St Paphnutius and St Paul the Hermit, attributed to Nicholas Bozon

Nicholas Bozon ('' fl.'' ), or ''Nicole Bozon'', was an Anglo-Norman writer and Franciscan friar who spent most of his life in the East Midlands and East Anglia. He was a prolific author in prose and verse, and composed a number of hagiographies ...

. This stimulating collection, with several items of East Anglian and feminine interest, was compiled between 1275 and 1325, and is beautifully written. A Latin Psalter which belonged to the priory, apparently produced c. 1247–1249, with superbly foliated initial letters, includes Calendar references to the East Anglian saints Seaxburga, Wihtburga and Edmund the Martyr

Edmund the Martyr (also known as St Edmund or Edmund of East Anglia, died 20 November 869) was king of East Anglia from about 855 until his death.

Few historical facts about Edmund are known, as the kingdom of East Anglia was devastated by t ...

, and has additions referring to Edmund Rich, Modwenna, etc., reflecting the ''Lives'' in the Campsey Collection.

The 14th-century seal of the priory depicts the Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother o ...

, crowned and seated on a throne, the Child Jesus

The Christ Child, also known as Divine Infant, Baby Jesus, Infant Jesus, the Divine Child, Child Jesus, the Holy Child, Santo Niño, and to some as Señor Noemi refers to Jesus Christ from his nativity to age 12.

The four canonical gospels, ...

standing on her right knee, within a triple-arched canopied niche

Niche may refer to:

Science

*Developmental niche, a concept for understanding the cultural context of child development

*Ecological niche, a term describing the relational position of an organism's species

*Niche differentiation, in ecology, the ...

. (This devotional image, the "Seat of Wisdom

Seat of Wisdom or Throne of Wisdom (Latin: ''sedes sapientiae'') is one of many devotional titles for Mary in Roman Catholic tradition. In Seat of Wisdom icons and sculptures, Mary is seated on a throne with the Christ Child on her lap. For the ...

", alludes to Mary as the Mother of God

''Theotokos'' (Greek: ) is a title of Mary, mother of Jesus, used especially in Eastern Christianity. The usual Latin translations are ''Dei Genitrix'' or ''Deipara'' (approximately "parent (fem.) of God"). Familiar English translations are " ...

, a popular but not the most prevalent form of her cult in medieval England.) Below, between two flowering branches, is a shield with heraldic device. The inscription on the seal reads: "Priorisse et Conventus S. Marie de Campissey".

Ufford patronage

The Valoines alliance

The priory came to the Uffords by the marriage of Cecily de Valoines to Robert, Lord of Ufford, in or before c.1295. Lord Ufford (1279–1316) succeeded his distinguished father, a notableJusticiar of Ireland

The chief governor was the senior official in the Dublin Castle administration, which maintained English and British rule in Ireland from the 1170s to 1922. The chief governor was the viceroy of the English monarch (and later the British monarch) ...

, who died in 1298 seised of the manors of Bawdsey

Bawdsey is a village and civil parish in Suffolk, eastern England. Located on the other side of the river Deben from Felixstowe, it had an estimated population of 340 in 2007, reducing to 276 at the Census 2011.

Bawdsey Manor is notable as the ...

and Ufford, the town of Orford with Orford Castle

Orford Castle is a castle in Orford in the English county of Suffolk, northeast of Ipswich, with views over Orford Ness. It was built between 1165 and 1173 by Henry II of England to consolidate royal power in the region. The well-preserved ...

, the soke of Wykes in Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

, the township of Wickham Market, the rents of Ufford, Dallinghoo

Dallinghoo is a village about north of Woodbridge, Suffolk, England.

Location

Dallinghoo is formed from Church Road to the west, Pound Hill to the south and branches northeast after the centre of the village. Dallinghoo Village Hall is on ...

, Rendlesham

Rendlesham is a village and civil parish near Woodbridge, Suffolk, United Kingdom. It was a royal centre of authority for the king of the East Angles, of the Wuffinga line; the proximity of the Sutton Hoo ship burial may indicate a connection ...

and Woodbridge, the advowsons of Wickham Market and Ufford with its chapel of Sogenho, and lands in Melton. Cecily's inheritance, including the patronage of Campsey Priory (with its own extensive endowments represented in the ''Taxatio Ecclesiastica

The ''Taxatio Ecclesiastica'', often referred to as the ''Taxatio Nicholai'' or just the ''Taxatio'', compiled in 1291–92 under the order of Pope Nicholas IV, is a detailed database valuation for ecclesiastical taxation of English, Welsh, an ...

'' of 1291–92) greatly enlarged the sphere of this seat of power. In 1306 she received a de Creke legacy including the advowson of Helmingham, which she gave to her family's nunnery at Flixton Priory.

The de Ufford estates faced the demesne lands and churches of Butley Priory directly. In 1290 the patronage of the Butley and Leiston monasteries passed (with the manor of Benhall) to Guy Ferre the younger, an important and trusted figure in the royal administration in Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part o ...

, and Seneschal in 1308-09. He associated his wife in the title and before his death in 1323 enriched Butley Priory with its fine Gatehouse. Lord Ufford, who was summoned as a baron to parliament, had six sons and a daughter, and died in 1316, succeeded by his second son Robert de Ufford as heir in 1318. Cecily died in 1325: a year previously Robert had married Margaret, daughter of Sir Walter de Norwich (Chief Baron of the Exchequer

The Chief Baron of the Exchequer was the first "baron" (meaning judge) of the English Exchequer of Pleas. "In the absence of both the Treasurer of the Exchequer or First Lord of the Treasury, and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, it was he who pre ...

, died 1329) of Mettingham Castle

Mettingham Castle was a fortified manor house in the parish of Mettingham in the north of the English county of Suffolk.

Details

Mettingham Castle was founded by Sir John de Norwich, who was given a licence to crenellate his existing manor ho ...

, and widow of Thomas, Lord de Cailli of Buckenham Castle

Old Buckenham Castle and Buckenham Castle are two castles adjacent respectively to the villages of Old Buckenham and New Buckenham, Norfolk, England.

Old Buckenham Castle

All that remains today of what was a Norman castle are the remnants of t ...

and Hilborough

Hilborough is a village and a civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. The village is south of Swaffham, west-southwest of Norwich and north-northeast of London.

The population of the parish (including Bodney) at the 2011 Census was 243. ...

, Norfolk.

Chantries

AmidRobert de Ufford

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

's swift rise in the favour of King Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

a perpetual chantry

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area in ...

was established at Campsey Priory in 1333, at the application of Queen Philippa

Philippa of Hainault (sometimes spelled Hainaut; Middle French: ''Philippe de Hainaut''; 24 June 1310 (or 1315) – 15 August 1369) was Queen of England as the wife and political adviser of King Edward III. She acted as regent in 1346,Strickla ...

, for a canon and two assistants to sing masses there for the soul of Alice of Hainault

Alice of Hainault, Countess Marshal (died 26 October 1317), was the daughter of John de Avenes, Count of Hainault, and Philippine, daughter of the Count of Luxembourg. She was the second wife of Roger Bigod, 5th Earl of Norfolk, Earl Marshal of ...

, Countess Marshal (died 1317), widow of the 5th Earl of Norfolk. At about this time Maria de Wyngfield was prioress of Campsey. Following the death of the Earl of Cornwall

The title of Earl of Cornwall was created several times in the Peerage of England before 1337, when it was superseded by the title Duke of Cornwall, which became attached to heirs-apparent to the throne.

Condor of Cornwall

*Condor of Cornwall, ...

, in 1337 Robert was created Earl of Suffolk

Earl of Suffolk is a title which has been created four times in the Peerage of England. The first creation, in tandem with the creation of the title of Earl of Norfolk, came before 1069 in favour of Ralph the Staller; but the title was forfei ...

, his maintenance including the Honour of Eye

In the kingdom of England, a feudal barony or barony by tenure was the highest degree of feudal land tenure, namely ''per baroniam'' (Latin for "by barony"), under which the land-holder owed the service of being one of the king's barons. The ...

with the reversion of the manor of Benhall (with patronage of Butley Priory and Leiston Abbey) which, however, rested for life with Guy Ferre's widow Eleanor (died 1349).

The Earl's brother Sir Ralph de Ufford also enjoyed royal favour and rewards, and was made Constable of Corfe Castle

Corfe Castle is a fortification standing above the village of the same name on the Isle of Purbeck peninsula in the English county of Dorset. Built by William the Conqueror, the castle dates to the 11th century and commands a gap in the P ...

in 1341. He married Maud of Lancaster, widow of William Donn de Burgh, 3rd Earl of Ulster

William de Burgh, 3rd Earl of Ulster and 4th Baron of Connaught (; ; 17 September 1312 – 6 June 1333) was an Irish noble who was Lieutenant of Ireland (1331) and whose murder, aged 20, led to the Burke Civil War.

Background

The grandson ...

, the Justiciar assassinated at Carrickfergus

Carrickfergus ( , meaning " Fergus' rock") is a large town in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It sits on the north shore of Belfast Lough, from Belfast. The town had a population of 27,998 at the 2011 Census. It is County Antrim's oldest t ...

in 1333. They were married by August 1343, when they obtained papal indults from Clement VI

Pope Clement VI ( la, Clemens VI; 1291 – 6 December 1352), born Pierre Roger, was head of the Catholic Church from 7 May 1342 to his death in December 1352. He was the fourth Avignon pope. Clement reigned during the first visitation of the Bla ...

to choose confessors, hold portable altars, and to have religious persons eat flesh at their table. Sir Ralph became Justiciar of Ireland in February 1344. After two years of stern and unpopular rule, while his wife lived as a queen at Kilmainham

Kilmainham (, meaning " St Maighneann's church") is a south inner suburb of Dublin, Ireland, south of the River Liffey and west of the city centre. It is in the city's Dublin 8 postal district. The area was once known as Kilmanum.

History

In t ...

Priory, he died there at Easter 1346. The Countess returned with his body and he was buried in the chapel of the Annunciation

The Annunciation (from Latin '), also referred to as the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Annunciation of Our Lady, or the Annunciation of the Lord, is the Christian celebration of the biblical tale of the announcement by the ange ...

in Campsey Priory church.

Maud, whose sister Isabel was prioress of Amesbury Priory

Amesbury Priory was a Benedictine monastery at Amesbury in Wiltshire, England, belonging to the Order of Fontevraud. It was founded in 1177 to replace the earlier Amesbury Abbey, a Saxon foundation established about the year 979. The Anglo-Norma ...

, resolved to join the Campsey sisterhood. Supported by her brother Henry of Grosmont

Henry of Grosmont, Duke of Lancaster (– 23 March 1361) was an English statesman, diplomat, soldier, and Christian writer. The owner of Bolingbroke Castle in Lincolnshire, Grosmont was a member of the House of Plantagenet, which was ruling ov ...

she arranged endowments for a perpetual chantry

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area in ...

of five male chaplains (one the warden) to sing daily masses in that chapel for Ralph's soul. In August 1347, taking the veil, she was allowed income from her estates for one further year, after which 200 marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks, trademarks owned by an organisation for the benefit of its members

* Marks & Co, the inspiration for the novel ...

were assigned to the priory yearly during her life. In October the chantry was ordained for the souls of both husbands, for her daughters Elizabeth de Burgh

Lady Elizabeth de Burgh (; ; c. 1289 – 27 October 1327) was the second wife and the only queen consort of King Robert the Bruce. Elizabeth was born sometime around 1289, probably in what is now County Down or County Antrim in Ulster, th ...

and Maud de Ufford

Maud de Ufford, Countess of Oxford (1345/1346 – 25 January 1413) was a wealthy English noblewoman and the wife of Thomas de Vere, 8th Earl of Oxford. Her only child was Robert de Vere, 9th Earl of Oxford, the favourite of King Richard II of E ...

, and for the welfare of herself, of John de Ufford and Thomas de Hereford (grantors), and with a house in the nearby settlement of Ash-by-Rendlesham for the chaplains. Both her daughters were married by 1350 in childhood, Elizabeth to Lionel of Antwerp

Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence, (; 29 November 133817 October 1368) was the third son, but the second son to survive infancy, of the English king Edward III and Philippa of Hainault. He was named after his birthplace, at Antwerp in the Duc ...

, and Maud to Thomas de Vere.

The college at Bruisyard

Campsey's small college of secular priests survived the Great Mortality of 1348–49 and remained at Ash until 1354. Its first master, John de Haketon, was appointed in January 1349 and the second, John de Aston, in 1352. The Earl's brothers Edmund and John de Ufford, with others, simultaneously granted the manor ofStanford, Norfolk

Stanford is a deserted village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. It is situated some north of the town of Thetford and southwest of the city of Norwich.

The villages name means 'stony ford'.

The village became deserted when i ...

and Roke Hall in Bruisyard

Bruisyard is a village in the valley of the River Alde in the county of Suffolk, England. The village had a population of around 175 at the 2011 census.

, Suffolk in January 1353. It was now arranged that the chaplains (who were all old men) should set up their college anew at Bruisyard. It was urged that the walk from Ash to the priory was hard for them, their masses clashed with the singing in the nuns' choir, and that clerks and women ought to live separately. With a further endowment by Thomas de Holebrok on 13 August 1354, Bishop William Bateman set forth preliminary statutes: they were to live, eat and sleep communally, and to follow the Use of Sarum

The Use of Sarum (or Use of Salisbury, also known as the Sarum Rite) is the Latin liturgical rite developed at Salisbury Cathedral and used from the late eleventh century until the English Reformation. It is largely identical to the Roman rite ...

in their three daily masses in a new collegiate church In Christianity, a collegiate church is a church where the daily office of worship is maintained by a college of canons: a non-monastic or "secular" community of clergy, organised as a self-governing corporate body, which may be presided over by a ...

of the Annunciation at Roke Hall. All parties assented between 18 and 24 August 1354, and the college under John de Aston was accordingly translated there. Bishop Bateman died unexpectedly in 1355, but full and lengthy statutes were set forth by Maud of Lancaster in 1356.

Robert de Ufford, occupied with military affairs until 1360, was confirmed patron of Leiston Abbey

Leiston Abbey outside the town of Leiston, Suffolk, England, was a religious house of Canons Regular following the Premonstratensian rule (White canons), dedicated to Mary, mother of Jesus, St Mary. Founded in c. 1183 by Ranulf de Glanville (c. 11 ...

, and he refounded and rebuilt it at a new site after the old abbey was ruined by flooding from the sea. The Countess Maud remained at Campsey for a further decade. A daughter of Maud de Chaworth, she appointed that alms should be given to her family's house of friars minor at Ipswich after the deaths of her chaplains. Wishing to avoid the many noble visitors, she caused herself to be enclosed at Campsey. Her daughter Elizabeth died in 1363. Lionel of Antwerp (by papal petition of John, King of France) thereupon refounded Bruisyard as a monastery for 13 or more nuns minoresses of St Clare, to be brought from Denny Abbey

Denny Abbey is a former abbey near Waterbeach, about north of Cambridge in Cambridgeshire, England. It is now the Farmland Museum and Denny Abbey.

The monastery was inhabited by a succession of three different religious orders. The site is a ...

and elsewhere, under an abbess

An abbess (Latin: ''abbatissa''), also known as a mother superior, is the female superior of a community of Catholic nuns in an abbey.

Description

In the Catholic Church (both the Latin Church and Eastern Catholic), Eastern Orthodox, Coptic ...

. Maud, professing to have loved the friars minor

The Order of Friars Minor (also called the Franciscans, the Franciscan Order, or the Seraphic Order; postnominal abbreviation OFM) is a mendicant Catholic religious order, founded in 1209 by Francis of Assisi. The order adheres to the teachin ...

from childhood, entered the Order of St Clare and removed to Bruisyard Abbey: the transfer was complete by 1366. Emma Beauchamp was abbess by 1369 until at least 1390. Maud died in 1377 and was buried at the abbey.

Ufford mausoleum

Margaret, Countess of Suffolk, died in 1368 and was buried at Campsey Priory church under the arch between the chapel of St Nicholas and the high altar. Earl Robert made his will directing that he should be buried beside her, and died in the following year. His brother Sir Edmund de Ufford, whose wife Elizabeth had predeceased him, followed in 1375, and was buried beside her in the chapel of St Mary in the priory church. Floor-tiles bearing his arms, with afleur-de-lys

The fleur-de-lis, also spelled fleur-de-lys (plural ''fleurs-de-lis'' or ''fleurs-de-lys''), is a lily (in French, and mean 'flower' and 'lily' respectively) that is used as a decorative design or symbol.

The fleur-de-lis has been used in the ...

as a cadency

In heraldry, cadency is any systematic way to distinguish arms displayed by descendants of the holder of a coat of arms when those family members have not been granted arms in their own right. Cadency is necessary in heraldic systems in which ...

mark for the sixth son, were found in the 1970 excavation. Maud de Ufford, a daughter of Earl Robert, was also a canoness at the priory. Robert's eldest surviving son, William de Ufford, 2nd Earl of Suffolk

William Ufford, 2nd Earl of Suffolk (30 May 1338 – 15 February 1382) was an English nobleman in the reigns of Edward III and Richard II. He was the son of Robert Ufford, who was created Earl of Suffolk by Edward III in 1337. William had thre ...

, before 1361 had married Joan Montague (daughter of Edward de Montacute and Alice de Brotherton), bringing him her inheritance of Framlingham Castle

Framlingham Castle is a castle in the market town of Framlingham in Suffolk in England. An early motte and bailey or ringwork Norman castle was built on the Framlingham site by 1148, but this was destroyed (Slighting, slighted) by Henry II of E ...

and her brother's barony. She died in 1375–76 and was buried at Campsey, probably with her young children who had recently died.

Earl William immediately remarried to Isabella, a daughter of Thomas de Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick

Thomas de Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick, KG (c. 14 February 131313 November 1369), sometimes styled as Lord Warwick, was an English nobleman and military commander during the Hundred Years' War. His reputation as a military leader was so f ...

, and widow of John Lord Lestrange of Blackmere. In his will, proved in 1381/2, William de Ufford left substantial gifts to various monasteries and directed that he should be buried in a marble tomb in the priory's chapel of St Nicholas, behind his parents' tomb. He further deposed that, if he died without heir male, the sword given by King Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring ro ...

to his father with the title of Earl was to be offered at Campsey on the day of his burial, and was to remain there forever. In March 1381/2 Isabella made a religious vow of lifelong chastity at the high altar of Campsey Priory, before Thomas Bishop of Ely, various abbots and priors assisting, in the presence of Henry Bishop of Norwich, her brother the 12th Earl of Warwick, her husband's nephews Robert, 4th Lord Willoughby and Roger de Scales, 4th Baron Scales

Roger Scales, 4th Baron Scales (1354–1387) was one of the 'eminent persons' forced by the rebels to march with them upon the insurrection of Jack Straw in 1381. He was a commissioner of the peace for Cambridgeshire and Norfolk for many of the ...

, many other knights and a large assembly.

Some insight into their monuments was gained by the discovery of two mutilated tomb effigies

A tomb effigy, usually a recumbent effigy or, in French, ''gisant'' (French language, French, "lying"), is a sculpted figure on a tomb monument depicting in effigy the deceased. These compositions were developed in Western Europe in the M ...

at Rendlesham church in 1785. Both displayed arms

Arms or ARMS may refer to:

*Arm or arms, the upper limbs of the body

Arm, Arms, or ARMS may also refer to:

People

* Ida A. T. Arms (1856–1931), American missionary-educator, temperance leader

Coat of arms or weapons

*Armaments or weapons

**Fi ...

referring to the marriage of Ufford and de Valoines. One was the figure of a woman beneath a crocket

A crocket (or croquet) is a small, independent decorative element common in Gothic architecture. The name derives from the diminutive of the French ''croc'', meaning "hook", due to the resemblance of crockets to a bishop's crosier.

Description

...

ed canopy, probably of about 1325, suggesting identification with Cecily de Valoines, mother of the 1st Earl. The other was of an armoured man in mail

The mail or post is a system for physically transporting postcards, letter (message), letters, and parcel (package), parcels. A postal service can be private or public, though many governments place restrictions on private systems. Since the mid ...

gorget

A gorget , from the French ' meaning throat, was a band of linen wrapped around a woman's neck and head in the medieval period or the lower part of a simple chaperon hood. The term later described a steel or leather collar to protect the thro ...

and jupon

A surcoat or surcote is an outer garment that was commonly worn in the Middle Ages by soldiers. It was worn over armor to show insignia and help identify what side the soldier was on. In the battlefield the surcoat was also helpful with keeping ...

, worn in a style of the mid-14th century: a possible candidate for the 1st Earl himself. Re-used face-down as flooring slabs, they may have been brought from the priory nearby. The excavation of 1970 opened part of a south choir-aisle chapel of the lost priory church. At the site of a tomb chamber, slabs from the sides and end of a large purbeck marble

Purbeck Marble is a fossiliferous limestone found in the Isle of Purbeck, a peninsula in south-east Dorset, England. It is a variety of Purbeck stone that has been quarried since at least Roman times as a decorative building stone.

Geology

Strat ...

tomb chest

A church monument is an architectural or sculptural memorial to a deceased person or persons, located within a Christian church. It can take various forms ranging from a simple commemorative plaque or mural tablet affixed to a wall, to a large and ...

of the later 14th century were found, of very fine workmanship. The long sides had each formed nine panels with half pedestals and foliated canopies for mourner

A mourner is someone who is attending a funeral or who is otherwise recognized as in a period of grief and mourning prescribed either by religious law or by popular custom. Many cultures expect mourners to curtail certain activities, usually tho ...

figures, the capitals of their columns sculpted with heads and small animals. Between the canopies were recesses for heraldic shields. This was possibly the tomb of the 2nd Earl. Fragments of carved armour and drapery were also discovered.

The chantry college refounded

The chaplains were still at Campsey in 1381, as Earl William's will shows, and in 1383 and 1390 Sir Roger de Boys and others, attorneys for the remainders of Edmund de Ufford, made two endowments to re-found the chantry college there, and to provide for two additional nuns. Statutes were set forth by Henry Bishop of Norwich in 1390 and approved by the prioress, Maria de Felton (daughter of Sir Thomas de Felton). A manse was to be built within the priory close, with common rooms, dormitory and refectory, to house five secular chaplains. They were to celebrate daily for the souls of Robert and William de Ufford and their wives in the chapel of St Thomas the Martyr, and were on no account to enter the cloister or nuns' quarters. The master, however, was to celebrate high mass at special feasts in the priory church. Maria de Felton died in 1394 and was succeeded as prioress by Margaret de Bruisyard. As a vowess Isabella Countess of Suffolk continued to enjoy much of her husband's estate during her lifetime, and at her death in 1416 requested to be buried with him in the priory church. Isabella's first marriage to Lord le Strange reinforced the priory's long-standing endowments at Tottington in Norfolk, through the continuing series of charters by which Symon de Bruna and his daughter Katherine, and after them Sir John L'Estrange of Hunstanton (in the time of prioress Maria de Felton), and lastly his son John L'Estrange and his widow Eleanor in 1416 (in the time of prioress Alice Corbet), confirmed and made further grants there to Campsey Priory. Alice Corbet, installed in 1411, was succeeded as prioress in 1416 by Katherine Ancell.The late prioresses

The prioress Margery Rendlesham is recorded in 1446 and Margaret Hengham in 1477. The late years of the Priory are illuminated by the Visitations of the Bishops of Norwich. Bishop Goldwell, in his visitation of 1492, found all well with Prioress Katherine, subprioress Katherine Babyngton, and the eighteen other nuns. Their names, Mortimer, Jernyngham, Hervy, Blanerhasett, Jenney and Everard at once reveal the old gentry origins of the sisterhood. A prioress Anna is recorded in 1502, but little is known of her. On 31 July 1514, having reprimanded canon Reginald Westerfield at Butley Priory for calling the junior canons " whoresons", Bishop Nykke spent the night at Campsey and saw the nuns on the following day. He found prioress Elizabeth Everard, her subprioress Petronilla Fulmerstoune, and the nineteen other sisters all most praiseworthy in temporal and spiritual affairs, and only asked them to make an inventory of their goods before he moved on to inspectWoodbridge Priory

Woodbridge Priory was a small Augustinian priory of canons regular in Woodbridge in the English county of Suffolk. The priory was founded in around 1193 by Ernald Rufus and was dissolved about 1537 during the dissolution of the monasteries.Page. ...

. Prioress Elizabeth Blenerhassett had succeeded by 1518. The schedule of the 1520 visit is missing, perhaps because nothing was found needing reform among the prioress and her twenty nuns.

The last prioress of Campsey, Elizabeth Buttry, has her own special place in the priory's history. She had been a member of the community since before 1492, and like the others had raised no complaints when the bishop came. It is suggested that she was a descendant of the Lords of Botreaux, as that name was pronounced. In the Bishop's visitation, 27 June 1526, Barbara Jernyngham was her subprioress, and Margaret Harman, precentrix, went so far as to say that in 35 years she had never known anything to need correction except that the books in the choir might be mended. The prioress and her twenty nuns, who all said ''omnia bene'', were told to mend the books and increase the number of nuns as far as possible.

By 1532, however, there were only 18 inmates, and the story had changed. Barbara Jernyngham was no longer sub-prioress, and said that all was well, as did Petronilla Felton, infirmarer and cellarer. But a chorus of voices complained that the prioress, while generous with her visitors, was very stingy towards the nuns, especially with their food. One had been kept waiting two hours for her dinner: several complained that the meat was unhealthy, and Katerina Grome said that if the bullock they had been fed had not been killed for the table it would have died anyway. For her part, the prioress remarked that the nuns spoke privately with the laity, to which Elizabeth Wingfield, chamberlain, responded that they were all forbidden to speak even to a graduate of the university, unless all were assembled together, and that her office was owed £5. Also that the nuns were not being paid their annual allowance of 6s 8d. from the bequest of William de Ufford.

The last prioress of Campsey, Elizabeth Buttry, has her own special place in the priory's history. She had been a member of the community since before 1492, and like the others had raised no complaints when the bishop came. It is suggested that she was a descendant of the Lords of Botreaux, as that name was pronounced. In the Bishop's visitation, 27 June 1526, Barbara Jernyngham was her subprioress, and Margaret Harman, precentrix, went so far as to say that in 35 years she had never known anything to need correction except that the books in the choir might be mended. The prioress and her twenty nuns, who all said ''omnia bene'', were told to mend the books and increase the number of nuns as far as possible.

By 1532, however, there were only 18 inmates, and the story had changed. Barbara Jernyngham was no longer sub-prioress, and said that all was well, as did Petronilla Felton, infirmarer and cellarer. But a chorus of voices complained that the prioress, while generous with her visitors, was very stingy towards the nuns, especially with their food. One had been kept waiting two hours for her dinner: several complained that the meat was unhealthy, and Katerina Grome said that if the bullock they had been fed had not been killed for the table it would have died anyway. For her part, the prioress remarked that the nuns spoke privately with the laity, to which Elizabeth Wingfield, chamberlain, responded that they were all forbidden to speak even to a graduate of the university, unless all were assembled together, and that her office was owed £5. Also that the nuns were not being paid their annual allowance of 6s 8d. from the bequest of William de Ufford.

Suppression

Campsey Priory was not a poor house, and even with slightly diminished numbers its income, taken together with that of the chantry college within its precinct, should have been sufficient to protect it from the closure of the smaller monasteries in 1536. The ''Valor Ecclesiasticus

The ''Valor Ecclesiasticus'' (Latin: "church valuation") was a survey of the finances of the church in England, Wales and English controlled parts of Ireland made in 1535 on the orders of Henry VIII. It was colloquially called the Kings books, a s ...

'' of 1536 (which identifies Robert de Ufford as the founder) shows the extent of Campsey's temporalities

Temporalities or temporal goods are the secular properties and possessions of the church. The term is most often used to describe those properties (a ''Stift'' in German or ''sticht'' in Dutch) that were used to support a bishop or other religious ...

and spiritualities Spiritualities is a term, often used in the Middle Ages, that refers to the income sources of a diocese or other ecclesiastical establishment that came from tithes. It also referred to income that came from other religious sources, such as offerings ...

in Suffolk. The commissioners' valuation however omitted the chantry college endowments of some £35 from the priory's income, assessed at a little over £182. As a result, the house fell victim to the first wave of suppression.

The inventory of the priory's goods was compiled by the commissioners, Sir Anthony Wingfield, Sir Humphrey Wingfield, Sir Thomas Russhe, Richard Southwell and Thomas Mildmay, on 29 August 1536. The last glimpse of the priory church shows the plate for the high altar, the parcel-gilt

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

silver altar cross of 30 ounces, a censer

A censer, incense burner, perfume burner or pastille burner is a vessel made for burning incense or perfume in some solid form. They vary greatly in size, form, and material of construction, and have been in use since ancient times throughout t ...

of 28 ounces, a pax

Pax or PAX may refer to:

Peace

* Peace (Latin: ''pax'')

** Pax (goddess), the Roman goddess of peace

** Pax, a truce term

* Pax (liturgy), a salutation in Catholic and Lutheran religious services

* Pax (liturgical object), an object formerly ki ...

of two ounces, a chalice

A chalice (from Latin 'mug', borrowed from Ancient Greek () 'cup') or goblet is a footed cup intended to hold a drink. In religious practice, a chalice is often used for drinking during a ceremony or may carry a certain symbolic meaning.

Re ...

of 13 ounces and a silver gilt pyx

A pyx or pix ( la, pyxis, transliteration of Greek: ''πυξίς'', boxwood receptacle, from ''πύξος'', box tree) is a small round container used in the Catholic, Old Catholic and Anglican Churches to carry the consecrated host (Eucharist) ...

of 9 ounces. There were also the altar cloth

An altar cloth is used in the Christian liturgy to cover the altar. It serves as a sign of reverence as well as a decoration and a protection of the altar and the sacred vessels. In the orthodox churches is covered by the antimension, which also c ...

of white silk, four great latten

Historically, the term "latten" referred loosely to the copper alloys such as brass

or bronze

that appeared in the Middle Ages and through to the late-18th and early-19th centuries. Such alloys were used for monumental brasses, in decorative effect ...

candlesticks, a timber reredos

A reredos ( , , ) is a large altarpiece, a screen, or decoration placed behind the altar in a church. It often includes religious images.

The term ''reredos'' may also be used for similar structures, if elaborate, in secular architecture, for ex ...

with imagery, other lamps, an image of Our Lady, two cruet

A cruet (), also called a caster, is a small flat-bottomed vessel with a narrow neck. Cruets often have an integral lip or spout, and may also have a handle. Unlike a small carafe, a cruet has a stopper or lid. Cruets are normally made from gla ...

s and an older Mass-book. The Lady Chapel had an alabaster reredos. In the vestry were five copes, one of crimson velvet with baudekin (a luxurious cloth), one of gold baudekin, one of violet silk, one of green silk with birds of copper gold, and one of blue with angels and stars. There were various other rich altar cloths and vestments

Vestments are liturgical garments and articles associated primarily with the Christian religion, especially by Eastern Churches, Catholics (of all rites), Anglicans, and Lutherans. Many other groups also make use of liturgical garments; this ...

. Other plate included a silver salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quantitie ...

with cover, two form pieces, and a pair of chalices.

No other books are mentioned. The priory was adequately furnished with feather beds and bolsters, forms, tables, chairs, stools and settles, with a painted cloth hanging in the Steward's chamber. We hear also of the Draught chamber, the Auditor's chamber, the Chamber at the church door, the Parlour, the New Parlour, the Buttery, the Kitchen, the Pantry, and the Bakehouse and Brewhouse. There were 10 milch-kine and a bull, 10 old plough and cart horses and two draught oxen, 26 loads of hay, 25 quarters of wheat and a quarter of barley. The total value of goods was £56 13s. An indented copy of the inventory, the goods to be held in safe keeping for the king's use, was presented to Elizabeth Buttery. She died in 1546, and was buried in St Stephen's Church, Norwich, where she has a monumental brass memorial.

Other Suffolk monasteries to be visited by the commissioners in this year were Flixton Priory, St Olave's Priory, Redlingfield Priory

Redlingfield Priory was a medieval nunnery in Redlingfield, Suffolk, England. It was closed in the 1530s.

The parish church, which dates back to Anglo-Saxon times, is thought to have been used by nuns

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate he ...

, the Priory of the Holy Trinity, Ipswich

Priory of the Holy Trinity was a priory in Ipswich, Suffolk, England. A church of that dedication was named in the Domesday Book, although the building date of the priory was 1177. After a fire, the monastery was rebuilt by John of Oxford, Bishop ...

, Ixworth Priory

Ixworth Priory was an Augustine priory at Ixworth in the English county of Suffolk. It was founded in the 12th century and dissolved in 1537.

, Eye Priory, Leiston Abbey

Leiston Abbey outside the town of Leiston, Suffolk, England, was a religious house of Canons Regular following the Premonstratensian rule (White canons), dedicated to Mary, mother of Jesus, St Mary. Founded in c. 1183 by Ranulf de Glanville (c. 11 ...

, Letheringham Priory and Blythburgh Priory

Blythburgh Priory was a medieval monastic house of Augustinian canons, dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, located in the village of Blythburgh in Suffolk, England. Founded in the early 12th century, it was among the first Augustinian houses in ...

.

Transition to domestic use

Henry VIII granted the site of Campsey Priory, with the demesne lands, the manor of Campsey, and the lands called Valeyns in Blaxhall, and various other lands formerly belonging to the priory, to Sir William Willoughby, later Lord Willoughby in 1543. (Willoughby had been, perhaps, the servant of Henry Fitzroy,illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as ''b ...

son of the King.) Two years later Lord Willoughby conveyed the manor and various other lands to John Some, by whom they were divided into moieties. In 1550 Lord Willoughby alienated the site of the nunnery, with its appurtenant lands in Campsea Ash, Wickham Market, Rendlesham and Loudham to John Lane, Esq.

The property passed through several hands, including those of Sir William Chapman, Baronet, High Sheriff of Suffolk

This is a list of Sheriffs and High Sheriffs of Suffolk.

The Sheriff is the oldest secular office under the Crown and is appointed annually (in March) by the Crown. The Sheriff was originally the principal law enforcement officer in the county a ...

for 1767. The site of the priory itself is now occupied by a farmhouse. Abbey House, a grade II* listed building standing near to the site of the nunnery, possibly incorporates in its fabric part of the living quarters of the chaplains.

Burials

*Robert Ufford, 1st Earl of Suffolk

Robert Ufford, 1st Earl of Suffolk, KG (9 August 1298 – 4 November 1369) was an English peer. He was created Earl of Suffolk in 1337.

Early life

Born 9 August 1298, Robert Ufford was the second but eldest surviving son of Robert Ufford, 1st B ...

*William Ufford, 2nd Earl of Suffolk

William Ufford, 2nd Earl of Suffolk (30 May 1338 – 15 February 1382) was an English nobleman in the reigns of Edward III and Richard II. He was the son of Robert Ufford, who was created Earl of Suffolk by Edward III in 1337. William had thre ...

*Christopher Willoughby, 10th Baron Willoughby de Eresby

Sir Christopher Willoughby, ''de jure'' 10th Baron Willoughby de Eresby, KB (1453 – between 1 November 1498 and 13 July 1499), was heir to his second cousin, Joan Welles, 9th Baroness Willoughby de Eresby, in her own right Lady Willoughby, as ...

References

{{coord, 52.1396, 1.3865, type:landmark_region:GB, display=title Augustinian nunneries in England 1195 establishments in England 1536 disestablishments in England Religious organizations established in the 1190s Christian monasteries established in the 12th century Women of medieval England Monasteries in Suffolk History of Suffolk Grade II* listed buildings in Suffolk Grade II listed monasteries