Bulgarian language on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bulgarian (, ; bg, label=none, български, bălgarski, ) is an Eastern South Slavic language spoken in

''Bulgarian'' was the first Slavic language attested in writing. As Slavic linguistic unity lasted into late antiquity, the oldest manuscripts initially referred to this language as ѧзꙑкъ словѣньскъ, "the Slavic language". In the Middle Bulgarian period this name was gradually replaced by the name ѧзꙑкъ блъгарьскъ, the "Bulgarian language". In some cases, this name was used not only with regard to the contemporary Middle Bulgarian language of the copyist but also to the period of Old Bulgarian. A most notable example of anachronism is the Service of Saint Cyril from Skopje (Скопски миней), a 13th-century Middle Bulgarian manuscript from northern Macedonia according to which St. Cyril preached with "Bulgarian" books among the Moravian Slavs. The first mention of the language as the "Bulgarian language" instead of the "Slavonic language" comes in the work of the Greek clergy of the

''Bulgarian'' was the first Slavic language attested in writing. As Slavic linguistic unity lasted into late antiquity, the oldest manuscripts initially referred to this language as ѧзꙑкъ словѣньскъ, "the Slavic language". In the Middle Bulgarian period this name was gradually replaced by the name ѧзꙑкъ блъгарьскъ, the "Bulgarian language". In some cases, this name was used not only with regard to the contemporary Middle Bulgarian language of the copyist but also to the period of Old Bulgarian. A most notable example of anachronism is the Service of Saint Cyril from Skopje (Скопски миней), a 13th-century Middle Bulgarian manuscript from northern Macedonia according to which St. Cyril preached with "Bulgarian" books among the Moravian Slavs. The first mention of the language as the "Bulgarian language" instead of the "Slavonic language" comes in the work of the Greek clergy of the  During the Middle Bulgarian period, the language underwent dramatic changes, losing the Slavonic

During the Middle Bulgarian period, the language underwent dramatic changes, losing the Slavonic

The language is mainly split into two broad dialect areas, based on the different reflexes of the

The language is mainly split into two broad dialect areas, based on the different reflexes of the

Until the period immediately following the

Until the period immediately following the

, UCLA International Institute Outside Bulgaria and Greece, Macedonian is generally considered an

In 886 AD, the Bulgarian Empire introduced the

In 886 AD, the Bulgarian Empire introduced the

' ?

A verb is not always necessary, e.g. when presenting a choice:

* – 'him?'; – 'the yellow one?'The word ('either') has a similar etymological root: и + ли ('and') – e.g. ( – '(either) the yellow one or the red one.

wiktionary

/ref> Rhetorical questions can be formed by adding to a question word, thus forming a "double interrogative" – * – 'Who?'; – 'I wonder who(?)' The same construction +не ('no') is an emphasized positive – * – 'Who was there?' – – 'Nearly everyone!' (lit. 'I wonder who ''wasn't'' there')

Bulgarian at OmniglotBulgarian Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words

(from Wiktionary'

Swadesh list appendix

Information about the linguistic classification of the Bulgarian language (from Glottolog)The linguistic features of the Bulgarian language (from WALS, The World Atlas of Language Structures Online)Information about the Bulgarian language

from the

Locale Data Summary for the Bulgarian language

from

Eurodict — multilingual Bulgarian dictionariesRechnik.info — online dictionary of the Bulgarian languageRechko — online dictionary of the Bulgarian languageBulgarian–English–Bulgarian Online dictionary

fro

Bulgarian bilingual dictionariesEnglish, Bulgarian bidirectional dictionary

Courses

Bulgarian for Beginners

UniLang {{DEFAULTSORT:Bulgarian Language Analytic languages Languages of Bulgaria Languages of Greece Languages of Romania Languages of Serbia Languages of North Macedonia Languages of Turkey Languages of Moldova Languages of Ukraine South Slavic languages Subject–verb–object languages Languages written in Cyrillic script

Southeastern Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe (SEE) is a geographical subregion of Europe, consisting primarily of the Balkans. Sovereign states and territories that are included in the region are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia (al ...

, primarily in Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

. It is the language of the Bulgarians

Bulgarians ( bg, българи, Bǎlgari, ) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and the rest of Southeast Europe.

Etymology

Bulgarians derive their ethnonym from the Bulgars. Their name is not completely understo ...

.

Along with the closely related Macedonian language

Macedonian (; , , ) is an Eastern South Slavic language. It is part of the Indo-European language family, and is one of the Slavic languages, which are part of a larger Balto-Slavic branch. Spoken as a first language by around two million ...

(collectively forming the East South Slavic languages

The Eastern South Slavic dialects form the eastern subgroup of the South Slavic languages. They are spoken mostly in Bulgaria and North Macedonia, and adjacent areas in the neighbouring countries. They form the so-called Balkan Slavic li ...

), it is a member of the Balkan sprachbund and South Slavic dialect continuum

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulate over distance so that widely separated varie ...

of the Indo-European language family

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Du ...

. The two languages have several characteristics that set them apart from all other Slavic languages

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic, spoken during the Ear ...

, including the elimination of case declension, the development of a suffixed definite article

An article is any member of a class of dedicated words that are used with noun phrases to mark the identifiability of the referents of the noun phrases. The category of articles constitutes a part of speech.

In English, both "the" and "a(n)" ar ...

, and the lack of a verb infinitive

Infinitive (abbreviated ) is a linguistics term for certain verb forms existing in many languages, most often used as non-finite verbs. As with many linguistic concepts, there is not a single definition applicable to all languages. The word is deri ...

. They retain and have further developed the Proto-Slavic

Proto-Slavic (abbreviated PSl., PS.; also called Common Slavic or Common Slavonic) is the unattested, reconstructed proto-language of all Slavic languages. It represents Slavic speech approximately from the 2nd millennium B.C. through the 6th ...

verb system (albeit analytically). One such major development is the innovation of evidential

In linguistics, evidentiality is, broadly, the indication of the nature of evidence for a given statement; that is, whether evidence exists for the statement and if so, what kind. An evidential (also verificational or validational) is the particu ...

verb forms to encode for the source of information: witnessed, inferred, or reported.

It is the official language of Bulgaria, and since 2007 has been among the official languages of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

. It is also spoken by minorities in several other countries such as Moldova, Ukraine and Serbia.

History

One can divide the development of the Bulgarian language into several periods. * The Prehistoric period covers the time between the Slavic migration to the eastern Balkans ( 6th century CE) and the mission ofSaints Cyril and Methodius

Cyril (born Constantine, 826–869) and Methodius (815–885) were two brothers and Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".

They are credited wi ...

to Great Moravia in 860s and the language shift

Language shift, also known as language transfer or language replacement or language assimilation, is the process whereby a speech community shifts to a different language, usually over an extended period of time. Often, languages that are percei ...

from now extinct Bulgar language

Bulgar (also known as Bulghar, Bolgar, or Bolghar) is an extinct Oghur Turkic language spoken by the Bulgars.

The name is derived from the Bulgars, a tribal association that established the Bulgar state known as Old Great Bulgaria in the mid- ...

.

* Old Bulgarian

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic () was the first Slavic literary language.

Historians credit the 9th-century Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius with standardizing the language and using it in translating the Bible and othe ...

(9th to 11th centuries, also referred to as "Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic () was the first Slavic languages, Slavic literary language.

Historians credit the 9th-century Byzantine Empire, Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius with Standard language, standardizing the lan ...

") – a literary norm of the early southern dialect of the Proto-Slavic

Proto-Slavic (abbreviated PSl., PS.; also called Common Slavic or Common Slavonic) is the unattested, reconstructed proto-language of all Slavic languages. It represents Slavic speech approximately from the 2nd millennium B.C. through the 6th ...

language from which Bulgarian evolved. Saints Cyril and Methodius

Cyril (born Constantine, 826–869) and Methodius (815–885) were two brothers and Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".

They are credited wi ...

and their disciples used this norm when translating the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

and other liturgical literature from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

into Slavic.

* Middle Bulgarian

Middle Bulgarian language was the lingua franca and the most widely spoken language of the Second Bulgarian Empire. Being descended from Old Bulgarian, Middle Bulgarian eventually developed into modern Bulgarian language by the 16th century.

...

(12th to 15th centuries) – a literary norm that evolved from the earlier Old Bulgarian, after major innovations occurred. A language of rich literary activity, it served as the official administration language of the Second Bulgarian Empire.

* Modern Bulgarian dates from the 16th century onwards, undergoing general grammar and syntax changes in the 18th and 19th centuries. The present-day written Bulgarian language was standardized on the basis of the 19th-century Bulgarian vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

. The historical development of the Bulgarian language can be described as a transition from a highly synthetic language (Old Bulgarian) to a typical analytic language (Modern Bulgarian) with Middle Bulgarian as a midpoint in this transition.

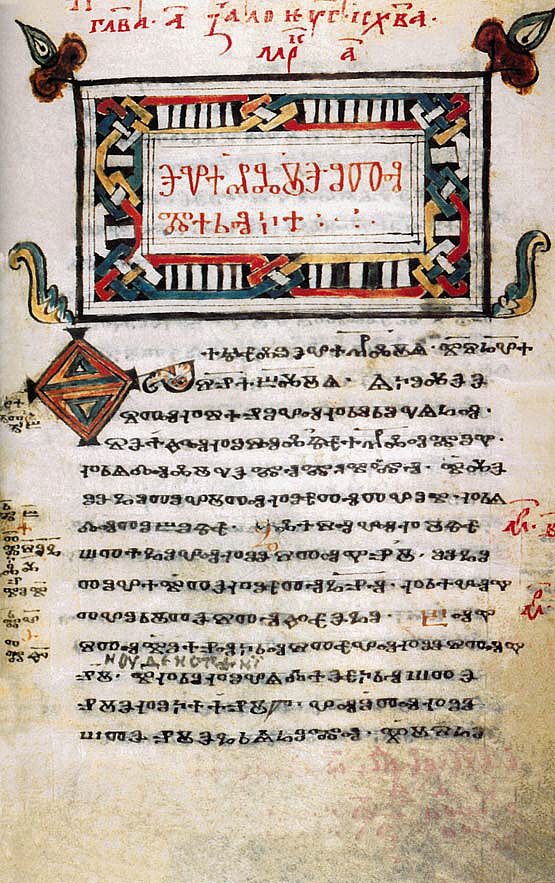

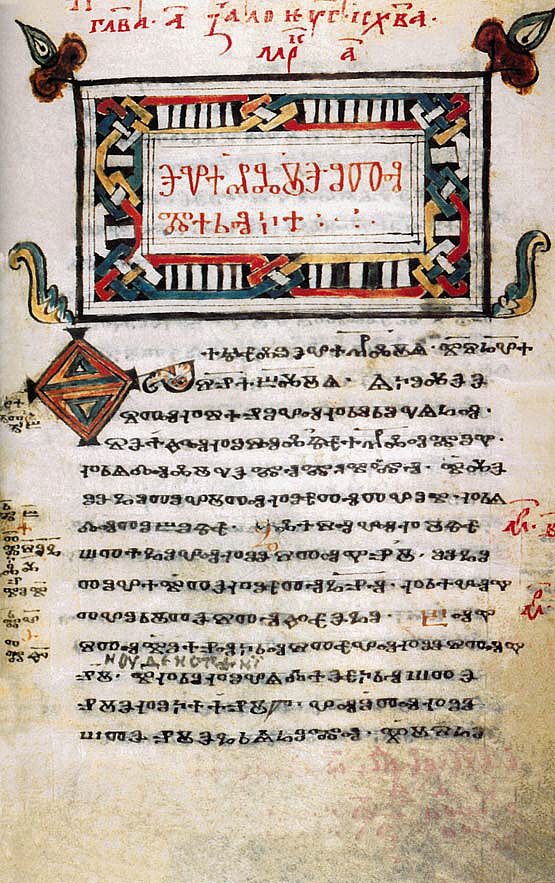

''Bulgarian'' was the first Slavic language attested in writing. As Slavic linguistic unity lasted into late antiquity, the oldest manuscripts initially referred to this language as ѧзꙑкъ словѣньскъ, "the Slavic language". In the Middle Bulgarian period this name was gradually replaced by the name ѧзꙑкъ блъгарьскъ, the "Bulgarian language". In some cases, this name was used not only with regard to the contemporary Middle Bulgarian language of the copyist but also to the period of Old Bulgarian. A most notable example of anachronism is the Service of Saint Cyril from Skopje (Скопски миней), a 13th-century Middle Bulgarian manuscript from northern Macedonia according to which St. Cyril preached with "Bulgarian" books among the Moravian Slavs. The first mention of the language as the "Bulgarian language" instead of the "Slavonic language" comes in the work of the Greek clergy of the

''Bulgarian'' was the first Slavic language attested in writing. As Slavic linguistic unity lasted into late antiquity, the oldest manuscripts initially referred to this language as ѧзꙑкъ словѣньскъ, "the Slavic language". In the Middle Bulgarian period this name was gradually replaced by the name ѧзꙑкъ блъгарьскъ, the "Bulgarian language". In some cases, this name was used not only with regard to the contemporary Middle Bulgarian language of the copyist but also to the period of Old Bulgarian. A most notable example of anachronism is the Service of Saint Cyril from Skopje (Скопски миней), a 13th-century Middle Bulgarian manuscript from northern Macedonia according to which St. Cyril preached with "Bulgarian" books among the Moravian Slavs. The first mention of the language as the "Bulgarian language" instead of the "Slavonic language" comes in the work of the Greek clergy of the Archbishopric of Ohrid

The Archbishopric of Ohrid, also known as the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid

*T. Kamusella in The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe, Springer, 2008, p. 276

*Aisling Lyon, Decentralisation and the Management of Ethni ...

in the 11th century, for example in the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

hagiography of Clement of Ohrid

Saint Clement of Ohrid ( Bulgarian, Serbian and Macedonian: Свети Климент Охридски, ; el, Ἅγιος Κλήμης τῆς Ἀχρίδας; sk, svätý Kliment Ochridský; – 916) was one of the first medieval Bulgarian ...

by Theophylact of Ohrid

Theophylact ( gr, Θεοφύλακτος, bg, Теофилакт; around 1055after 1107) was a Byzantine archbishop of Ohrid and commentator on the Bible.

Life

Theophylact was born in the mid-11th century at Euripus (Chalcis) in Euboea, at th ...

(late 11th century).

During the Middle Bulgarian period, the language underwent dramatic changes, losing the Slavonic

During the Middle Bulgarian period, the language underwent dramatic changes, losing the Slavonic case system

A grammatical case is a category of nouns and noun modifiers ( determiners, adjectives, participles, and numerals), which corresponds to one or more potential grammatical functions for a nominal group in a wording. In various languages, nom ...

, but preserving the rich verb system (while the development was exactly the opposite in other Slavic languages) and developing a definite article. It was influenced by its non-Slavic neighbors in the Balkan language area (mostly grammatically) and later also by Turkish, which was the official language of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, in the form of the Ottoman Turkish language

Ottoman Turkish ( ota, لِسانِ عُثمانى, Lisân-ı Osmânî, ; tr, Osmanlı Türkçesi) was the standardized register of the Turkish language used by the citizens of the Ottoman Empire (14th to 20th centuries CE). It borrowed exten ...

, mostly lexically. As a national revival

National revival or national awakening is a period of ethnic self-consciousness that often precedes a political movement for national liberation but that can take place at a time when independence is politically unrealistic. In the history of Eur ...

occurred toward the end of the period of Ottoman rule (mostly during the 19th century), a modern Bulgarian literary language gradually emerged that drew heavily on Church Slavonic/Old Bulgarian (and to some extent on literary Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

, which had preserved many lexical items from Church Slavonic) and later reduced the number of Turkish and other Balkan loans. Today one difference between Bulgarian dialects in the country and literary spoken Bulgarian is the significant presence of Old Bulgarian words and even word forms in the latter. Russian loans are distinguished from Old Bulgarian ones on the basis of the presence of specifically Russian phonetic changes, as in оборот (turnover, rev), непонятен (incomprehensible), ядро (nucleus) and others. Many other loans from French, English and the classical language

A classical language is any language with an independent literary tradition and a large and ancient body of written literature. Classical languages are typically dead languages, or show a high degree of diglossia, as the spoken varieties of the ...

s have subsequently entered the language as well.

Modern Bulgarian was based essentially on the Eastern dialects of the language, but its pronunciation is in many respects a compromise between East and West Bulgarian (see especially the phonetic sections below). Following the efforts of some figures of the National awakening of Bulgaria

The National awakening of Bulgaria refers to the Bulgarian nationalism that emerged in the early 19th century under the influence of western ideas such as liberalism and nationalism, which trickled into the country after the French revolution, mo ...

(most notably Neofit Rilski

Neofit Rilski ( bg, Неофит Рилски) or Neophyte of Rila (Bansko, 1793 – January 4, 1881), born Nikola Poppetrov Benin ( bg, Никола Поппетров Бенин) was a 19th-century Bulgarian monk, teacher and artist, and an impo ...

and Ivan Bogorov), there had been many attempts to codify a standard Standard may refer to:

Symbols

* Colours, standards and guidons, kinds of military signs

* Standard (emblem), a type of a large symbol or emblem used for identification

Norms, conventions or requirements

* Standard (metrology), an object th ...

Bulgarian language; however, there was much argument surrounding the choice of norms. Between 1835 and 1878 more than 25 proposals were put forward and "linguistic chaos" ensued.Glanville Price. ''Encyclopedia of the languages of Europe'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 2000), p.45 Eventually the eastern dialects prevailed,

Victor Roudometof. ''Collective memory, national identity, and ethnic conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian question'' (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002), p. 92

and in 1899 the Bulgarian Ministry of Education officially codified a standard Bulgarian language based on the Drinov-Ivanchev orthography.

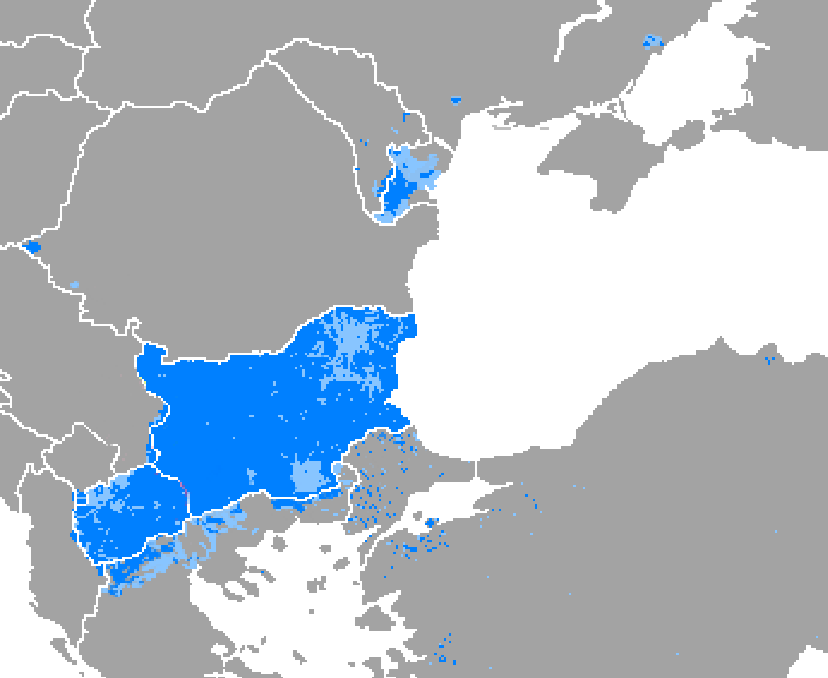

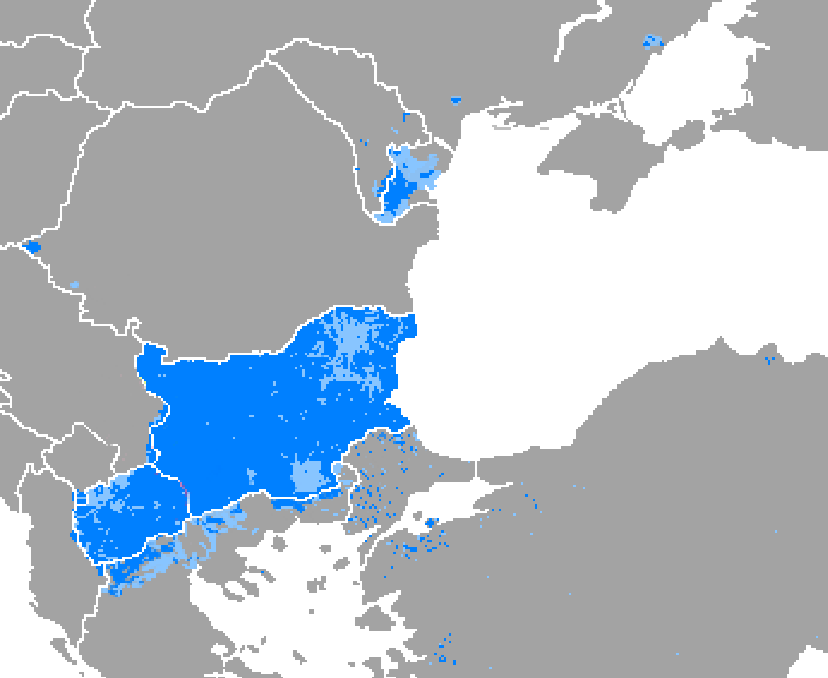

Geographic distribution

Bulgarian is the official language ofBulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

, where it is used in all spheres of public life. As of 2011, it is spoken as a first language by about 6million people in the country, or about four out of every five Bulgarian citizens. Of the 6.64 million people who answered the optional language question in the 2011 census, 5.66 million (or 85.2%) reported being native speakers of Bulgarian (this amounts to 76.8% of the total population of 7.36 million).

There is also a significant Bulgarian diaspora

The Bulgarian diaspora includes Bulgarians living outside Bulgaria and its surrounding countries, as well as immigrants from Bulgaria abroad.

The number of Bulgarians outside Bulgaria has sharply increased since 1989, following the Revolutions ...

abroad. One of the main historically established communities are the Bessarabian Bulgarians

The Bessarabian Bulgarians ( bg, бесарабски българи, ''besarabski bǎlgari'', ro, bulgari basarabeni, uk, бесарабські болгари, ''bessarabski bolháry'') are a Bulgarian minority group of the historical region ...

, whose settlement in the Bessarabia region of nowadays Moldavia and Ukraine dates mostly to the early 19th century. There were Bulgarian speakers in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

at the 2001 census, in Moldova

Moldova ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Moldova ( ro, Republica Moldova), is a Landlocked country, landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The List of states ...

as of the 2014 census (of which were habitual users of the language), and presumably a significant proportion of the 13,200 ethnic Bulgarians residing in neighbouring Transnistria

Transnistria, officially the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR), is an unrecognised breakaway state that is internationally recognised as a part of Moldova. Transnistria controls most of the narrow strip of land between the Dniester riv ...

in 2016.

Another community abroad are the Banat Bulgarians

The Banat Bulgarians ( Banat Bulgarian: ''Palćene'' or ''Banátsći balgare''; common bg, Банатски българи, Banatski balgari; ro, Bulgari bănățeni; sr, / ), also known as Bulgarian Roman Catholics and Bulgarians Paulician ...

, who migrated in the 17th century to the Banat region now split between Romania, Serbia and Hungary. They speak the Banat Bulgarian dialect

Banat Bulgarian (Banat Bulgarian: ''Palćena balgarsćija jázić'' or ''Banátsća balgarsćija jázić''; bg, банатскa българскa книжовна норма, translit=banastka balgarska knizhovna norma; german: Banater Bulgaris ...

, which has had its own written standard and a historically important literary tradition.

There are Bulgarian speakers in neighbouring countries as well. The regional dialects of Bulgarian and Macedonian form a dialect continuum, and there is no well-defined boundary where one language ends and the other begins. Within the limits of the Republic of North Macedonia

North Macedonia, ; sq, Maqedonia e Veriut, (Macedonia before February 2019), officially the Republic of North Macedonia,, is a country in Southeast Europe. It gained independence in 1991 as one of the successor states of Yugoslavia. It ...

a strong separate Macedonian identity has emerged since the Second World War, even though there still are a small number of citizens who identify their language as Bulgarian. Beyond the borders of North Macedonia, the situation is more fluid, and the pockets of speakers of the related regional dialects in Albania and in Greece variously identify their language as Macedonian or as Bulgarian. In Serbia, there were speakers as of 2011, mainly concentrated in the so-called Western Outlands

The Western (Bulgarian) Outlands () is a term used by Bulgarians to describe several regions located in southeastern Serbia.

The territories in question were ceded by Bulgaria to the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1920 as a resul ...

along the border with Bulgaria. Bulgarian is also spoken in Turkey: natively by Pomaks

Pomaks ( bg, Помаци, Pomatsi; el, Πομάκοι, Pomáki; tr, Pomaklar) are Bulgarian-speaking Muslims inhabiting northwestern Turkey, Bulgaria and northeastern Greece. The c. 220,000 strong ethno-confessional minority in Bulgaria is ...

, and as a second language by many Bulgarian Turks

Bulgarian Turks ( bg, български турци, bŭlgarski turtsi, tr, Bulgaristan Türkleri) are a Turkish ethnic group from Bulgaria. According to the 2021 census, there were 508,375 Bulgarians of Turkish descent, roughly 8.4% of t ...

who emigrated from Bulgaria, mostly during the "Big Excursion" of 1989.

The language is also represented among the diaspora in Western Europe and North America, which has been steadily growing since the 1990s. Countries with significant numbers of speakers include Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

( speakers in England and Wales as of 2011), France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

( in 2011).

Dialects

The language is mainly split into two broad dialect areas, based on the different reflexes of the

The language is mainly split into two broad dialect areas, based on the different reflexes of the Proto-Slavic

Proto-Slavic (abbreviated PSl., PS.; also called Common Slavic or Common Slavonic) is the unattested, reconstructed proto-language of all Slavic languages. It represents Slavic speech approximately from the 2nd millennium B.C. through the 6th ...

yat

Yat or jat (Ѣ ѣ; italics: ) is the thirty-second letter of the old Cyrillic alphabet and the Rusyn alphabet.

There is also another version of yat, the iotified yat (majuscule: , minuscule: ), which is a Cyrillic character combining a ...

vowel (Ѣ). This split, which occurred at some point during the Middle Ages, led to the development of Bulgaria's:

*Western dialects (informally called твърд говор/''tvurd govor'' – "hard speech")

**the former ''yat'' is pronounced "e" in all positions. e.g. млеко (''mlekò'') – milk, хлеб (''hleb'') – bread.

*Eastern dialects (informally called мек говор/''mek govor'' – "soft speech")

**the former ''yat'' alternates between "ya" and "e": it is pronounced "ya" if it is under stress and the next syllable does not contain a front vowel

A front vowel is a class of vowel sounds used in some spoken languages, its defining characteristic being that the highest point of the tongue is positioned as far forward as possible in the mouth without creating a constriction that would otherw ...

(''e'' or ''i'') – e.g. мляко (''mlyàko''), хляб (''hlyab''), and "e" otherwise – e.g. млекар (''mlekàr'') – milkman, хлебар (''hlebàr'') – baker. This rule obtains in most Eastern dialects, although some have "ya", or a special "open e" sound, in all positions.

The literary language norm, which is generally based on the Eastern dialects, also has the Eastern alternating reflex of ''yat''. However, it has not incorporated the general Eastern umlaut of ''all'' synchronic or even historic "ya" sounds into "e" before front vowels – e.g. поляна (''polyana'') vs. полени (''poleni'') "meadow – meadows" or even жаба (''zhaba'') vs. жеби (''zhebi'') "frog – frogs", even though it co-occurs with the yat alternation in almost all Eastern dialects that have it (except a few dialects along the yat border, e.g. in the Pleven region).

More examples of the ''yat'' umlaut in the literary language are:

*''mlyàko'' (milk) .→ ''mlekàr'' (milkman); ''mlèchen'' (milky), etc.

*''syàdam'' (sit) b.→ ''sedàlka'' (seat); ''sedàlishte'' (seat, e.g. of government or institution, butt), etc.

*''svyat'' (holy) dj.

A DJ or disc jockey is a person who plays recorded music for an audience.

DJ may also refer to:

Businesses

* Dow Jones Industrial Average, a stock market index

* Dansk Jernbane, a Danish freight company

* David Jones Limited, an Australian ret ...

→ ''svetètz'' (saint); ''svetìlishte'' (sanctuary), etc. (in this example, ''ya/e'' comes not from historical ''yat'' but from ''small yus ''(ѧ), which normally becomes ''e'' in Bulgarian, but the word was influenced by Russian and the ''yat'' umlaut)

Until 1945, Bulgarian orthography did not reveal this alternation and used the original Old Slavic Cyrillic letter ''yat'' (Ѣ), which was commonly called двойно е (''dvoyno e'') at the time, to express the historical ''yat'' vowel or at least root vowels displaying the ''ya – e'' alternation. The letter was used in each occurrence of such a root, regardless of the actual pronunciation of the vowel: thus, both ''mlyako'' and ''mlekar'' were spelled with (Ѣ). Among other things, this was seen as a way to "reconcile" the Western and the Eastern dialects and maintain language unity at a time when much of Bulgaria's Western dialect area was controlled by Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

and Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, but there were still hopes and occasional attempts to recover it. With the 1945 orthographic reform, this letter was abolished and the present spelling was introduced, reflecting the alternation in pronunciation.

This had implications for some grammatical constructions:

*The third person plural pronoun and its derivatives. Before 1945 the pronoun "they" was spelled тѣ (''tě''), and its derivatives took this as the root. After the orthographic change, the pronoun and its derivatives were given an equal share of soft and hard spellings:

**"they" – те (''te'') → "them" – тях (''tyah'');

**"their(s)" – ''tehen'' (masc.); ''tyahna'' (fem.); ''tyahno'' (neut.); ''tehni'' (plur.)

*adjectives received the same treatment as тѣ:

**"whole" – ''tsyal'' → "the whole...": ''tseliyat'' (masc.); ''tsyalata'' (fem.); ''tsyaloto'' (neut.); ''tselite'' (plur.)

Sometimes, with the changes, words began to be spelled as other words with different meanings, e.g.:

*свѣт (''svět'') – "world" became свят (''svyat''), spelt and pronounced the same as свят – "holy".

*тѣ (''tě'') – "they" became те (''te'').

In spite of the literary norm regarding the yat vowel, many people living in Western Bulgaria, including the capital Sofia

Sofia ( ; bg, София, Sofiya, ) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain in the western parts of the country. The city is built west of the Iskar river, and h ...

, will fail to observe its rules. While the norm requires the realizations ''vidyal'' vs. ''videli'' (he has seen; they have seen), some natives of Western Bulgaria will preserve their local dialect pronunciation with "e" for all instances of "yat" (e.g. ''videl'', ''videli''). Others, attempting to adhere to the norm, will actually use the "ya" sound even in cases where the standard language has "e" (e.g. ''vidyal'', ''vidyali''). The latter hypercorrection is called свръхякане (''svrah-yakane'' ≈"over-''ya''-ing").

;Shift from to

Bulgarian is the only Slavic language whose literary standard does not naturally contain the iotated

In Slavic languages, iotation (, ) is a form of palatalization that occurs when a consonant comes into contact with a palatal approximant from the succeeding phoneme. The is represented by iota (ι) in the Cyrillic alphabet and the Greek alphab ...

sound (or its palatalized variant , except in non-Slavic foreign-loaned words). The sound is common in all modern Slavic languages (e.g. Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

* Czech, ...

''medvěd'' "bear", Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

''pięć'' "five", Serbo-Croatian

Serbo-Croatian () – also called Serbo-Croat (), Serbo-Croat-Bosnian (SCB), Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian (BCS), and Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian (BCMS) – is a South Slavic language and the primary language of Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and ...

''jelen'' "deer", Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

''немає'' "there is not...", Macedonian ''пишување'' "writing", etc.), as well as some Western Bulgarian dialectal forms – e.g. ''ора̀н’е'' (standard Bulgarian: ''оране'' , "ploughing"), however it is not represented in standard Bulgarian speech or writing. Even where occurs in other Slavic words, in Standard Bulgarian it is usually transcribed and pronounced as pure – e.g. Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

is "Eltsin" ( Борис Елцин), Yekaterinburg

Yekaterinburg ( ; rus, Екатеринбург, p=jɪkətʲɪrʲɪnˈburk), alternatively romanized as Ekaterinburg and formerly known as Sverdlovsk ( rus, Свердло́вск, , svʲɪrˈdlofsk, 1924–1991), is a city and the administra ...

is "Ekaterinburg" ( Екатеринбург) and Sarajevo

Sarajevo ( ; cyrl, Сарајево, ; ''see names in other languages'') is the capital and largest city of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a population of 275,524 in its administrative limits. The Sarajevo metropolitan area including Sarajevo ...

is "Saraevo" ( Сараево), although - because the sound is contained in a stressed syllable at the beginning of the word - Jelena Janković

Jelena Janković ( sr-Cyrl, Јелена Јанковић, ; born 28 February 1985) is a Serbian former tennis player. A former world No. 1, Janković reached the top ranking before her career-best major performance, a runner-up finish at the ...

is "Yelena" – Йелена Янкович.

Relationship to Macedonian

Until the period immediately following the

Until the period immediately following the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, all Bulgarian and the majority of foreign linguists referred to the South Slavic dialect continuum spanning the area of modern Bulgaria, North Macedonia

North Macedonia, ; sq, Maqedonia e Veriut, (Macedonia before February 2019), officially the Republic of North Macedonia,, is a country in Southeast Europe. It gained independence in 1991 as one of the successor states of Socialist Feder ...

and parts of Northern Greece

Northern Greece ( el, Βόρεια Ελλάδα, Voreia Ellada) is used to refer to the northern parts of Greece, and can have various definitions.

Administrative regions of Greece

Administrative term

The term "Northern Greece" is widely used ...

as a group of Bulgarian dialects.Mazon, Andre. ''Contes Slaves de la Macédoine Sud-Occidentale: Etude linguistique; textes et traduction''; Notes de Folklore, Paris 1923, p. 4. In contrast, Serbian sources tended to label them "south Serbian" dialects. Some local naming conventions included ''bolgárski'', ''bugárski'' and so forth. The codifiers of the standard Bulgarian language, however, did not wish to make any allowances for a pluricentric

A pluricentric language or polycentric language is a language with several interacting codified standard language, standard forms, often corresponding to different countries. Many examples of such languages can be found worldwide among the most-spo ...

"Bulgaro-Macedonian" compromise. In 1870 Marin Drinov

Marin Stoyanov Drinov ( bg, Марин Стоянов Дринов, russian: Марин Степанович Дринов; 20 October 1838 - 13 March 1906) was a Bulgarian historian and philologist from the National Revival period who lived and ...

, who played a decisive role in the standardization of the Bulgarian language, rejected the proposal of Parteniy Zografski

Parteniy Zografski or Parteniy Nishavski ( bg, Партений Зографски/Нишавски; mk, Партенија Зографски; 1818 – February 7, 1876) was a 19th-century Bulgarian cleric, philologist, and folklorist from G ...

and Kuzman Shapkarev

Kuzman Anastasov Shapkarev, ( bg, Кузман Анастасов Шапкарев), (1 January 1834 in Ohrid – 18 March 1909 in Sofia) was a Bulgarian folklorist, ethnographer and scientist from the Ottoman region of Macedonia, author of te ...

for a mixed eastern and western Bulgarian/Macedonian foundation of the standard Bulgarian language, stating in his article in the newspaper Makedoniya: "Such an artificial assembly of written language is something impossible, unattainable and never heard of."

After 1944 the People's Republic of Bulgaria

The People's Republic of Bulgaria (PRB; bg, Народна Република България (НРБ), ''Narodna Republika Balgariya, NRB'') was the official name of Bulgaria, when it was a socialist republic from 1946 to 1990, ruled by the ...

and the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, commonly referred to as SFR Yugoslavia or simply as Yugoslavia, was a country in Central and Southeast Europe. It emerged in 1945, following World War II, and lasted until 1992, with the breakup of Yug ...

began a policy of making Macedonia into the connecting link for the establishment of a new Balkan Federative Republic

The Balkan Federation project was a left-wing political movement to create a country in the Balkans by combining Yugoslavia, Albania, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey.

The concept of a Balkan federation emerged in the late 19th century from ...

and stimulating here a development of distinct Macedonian consciousness. With the proclamation of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia as part of the Yugoslav federation, the new authorities also started measures that would overcome the pro-Bulgarian feeling among parts of its population and in 1945 a separate Macedonian language

Macedonian (; , , ) is an Eastern South Slavic language. It is part of the Indo-European language family, and is one of the Slavic languages, which are part of a larger Balto-Slavic branch. Spoken as a first language by around two million ...

was codified. After 1958, when the pressure from Moscow decreased, Sofia reverted to the view that the Macedonian language did not exist as a separate language. Nowadays, Bulgarian and Greek linguists, as well as some linguists from other countries, still consider the various Macedonian dialects as part of the broader Bulgarian pluricentric dialectal continuum

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulate over distance so that widely separated varie ...

.Language profile Macedonian, UCLA International Institute Outside Bulgaria and Greece, Macedonian is generally considered an

autonomous language

Autonomy and heteronomy are complementary attributes of a language variety describing its functional relationship with related varieties.

The concepts were introduced by William A. Stewart in 1968, and provide a way of distinguishing a ''language ...

within the South Slavic dialect continuum. Sociolinguists agree that the question whether Macedonian is a dialect of Bulgarian or a language is a political one and cannot be resolved on a purely linguistic basis, because dialect continua do not allow for either/or judgements. Nevertheless, Bulgarians often argue that the high degree of mutual intelligibility

In linguistics, mutual intelligibility is a relationship between languages or dialects in which speakers of different but related varieties can readily understand each other without prior familiarity or special effort. It is sometimes used as an ...

between Bulgarian and Macedonian proves that they are not different languages, but rather dialects of the same language, whereas Macedonians believe that the differences outweigh the similarities.

Alphabet

In 886 AD, the Bulgarian Empire introduced the

In 886 AD, the Bulgarian Empire introduced the Glagolitic alphabet

The Glagolitic script (, , ''glagolitsa'') is the oldest known Slavic alphabet. It is generally agreed to have been created in the 9th century by Saint Cyril, a monk from Thessalonica. He and his brother Saint Methodius were sent by the Byzan ...

which was devised by the Saints Cyril and Methodius

Cyril (born Constantine, 826–869) and Methodius (815–885) were two brothers and Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".

They are credited wi ...

in the 850s. The Glagolitic alphabet was gradually superseded in later centuries by the Cyrillic script

The Cyrillic script ( ), Slavonic script or the Slavic script, is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic languages, Slavic, Turkic languages, Turkic, Mongolic languages, ...

, developed around the Preslav Literary School

The Preslav Literary School ( bg, Преславска книжовна школа), also known as the Pliska Literary School or Pliska-Preslav Literary school was the first literary school in the medieval Bulgarian Empire. It was established by ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

in the late 9th century.

Several Cyrillic alphabets with 28 to 44 letters were used in the beginning and the middle of the 19th century during the efforts on the codification of Modern Bulgarian until an alphabet with 32 letters, proposed by Marin Drinov

Marin Stoyanov Drinov ( bg, Марин Стоянов Дринов, russian: Марин Степанович Дринов; 20 October 1838 - 13 March 1906) was a Bulgarian historian and philologist from the National Revival period who lived and ...

, gained prominence in the 1870s. The alphabet of Marin Drinov was used until the orthographic reform of 1945, when the letters yat

Yat or jat (Ѣ ѣ; italics: ) is the thirty-second letter of the old Cyrillic alphabet and the Rusyn alphabet.

There is also another version of yat, the iotified yat (majuscule: , minuscule: ), which is a Cyrillic character combining a ...

(uppercase Ѣ, lowercase ѣ) and yus (uppercase Ѫ, lowercase ѫ) were removed from its alphabet, reducing the number of letters to 30.

With the accession of Bulgaria to the European Union on 1 January 2007, Cyrillic became the third official script of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

, following the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and Greek scripts.

Phonology

Bulgarian possesses a phonology similar to that of the rest of the South Slavic languages, notably lacking Serbo-Croatian's phonemic vowel length and tones and alveo-palatal affricates. The eastern dialects exhibit palatalization of consonants before front vowels ( and ) and reduction of vowel phonemes in unstressed position (causing mergers of and , and , and ) - both patterns have partial parallels in Russian and lead to a partly similar sound. The western dialects are like Macedonian and Serbo-Croatian in that they do not have allophonic palatalization and have only little vowel reduction. Bulgarian has six vowel phonemes, but at least eight distinct phones can be distinguished when reduced allophones are taken into consideration.Grammar

The parts of speech in Bulgarian are divided in ten types, which are categorized in two broad classes: mutable and immutable. The difference is that mutable parts of speech vary grammatically, whereas the immutable ones do not change, regardless of their use. The five classes of mutables are: ''nouns'', ''adjectives'', ''numerals'', ''pronouns'' and ''verbs''. Syntactically, the first four of these form the group of the noun or the nominal group. The immutables are: ''adverbs'', ''prepositions'', ''conjunctions'', ''particles'' and ''interjections''. Verbs and adverbs form the group of the verb or the verbal group.Nominal morphology

Nouns and adjectives have thecategories

Category, plural categories, may refer to:

Philosophy and general uses

*Categorization, categories in cognitive science, information science and generally

*Category of being

* ''Categories'' (Aristotle)

*Category (Kant)

* Categories (Peirce)

* ...

grammatical gender

In linguistics, grammatical gender system is a specific form of noun class system, where nouns are assigned with gender categories that are often not related to their real-world qualities. In languages with grammatical gender, most or all nouns ...

, number

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The original examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual numbers c ...

, case (only vocative

In grammar, the vocative case (abbreviated ) is a grammatical case which is used for a noun that identifies a person (animal, object, etc.) being addressed, or occasionally for the noun modifiers (determiners, adjectives, participles, and numer ...

) and definiteness

In linguistics, definiteness is a semantic feature of noun phrases, distinguishing between referents or senses that are identifiable in a given context (definite noun phrases) and those which are not (indefinite noun phrases). The prototypical ...

in Bulgarian. Adjectives and adjectival pronouns agree with nouns in number and gender. Pronouns have gender and number and retain (as in nearly all Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutc ...

) a more significant part of the case system.

Nominal inflection

=Gender

= There are three grammatical genders in Bulgarian: ''masculine'', ''feminine'' and ''neuter''. The gender of the noun can largely be inferred from its ending: nouns ending in a consonant ("zero ending") are generally masculine (for example, 'city', 'son', 'man'; those ending in –а/–я (-a/-ya) ( 'woman', 'daughter', 'street') are normally feminine; and nouns ending in –е, –о are almost always neuter ( 'child', 'lake'), as are those rare words (usually loanwords) that end in –и, –у, and –ю ( 'tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater exp ...

', 'taboo', 'menu'). Perhaps the most significant exception from the above are the relatively numerous nouns that end in a consonant and yet are feminine: these comprise, firstly, a large group of nouns with zero ending expressing quality, degree or an abstraction, including all nouns ending on –ост/–ест -=Number

= Two numbers are distinguished in Bulgarian–singular

Singular may refer to:

* Singular, the grammatical number that denotes a unit quantity, as opposed to the plural and other forms

* Singular homology

* SINGULAR, an open source Computer Algebra System (CAS)

* Singular or sounder, a group of boar, ...

and plural

The plural (sometimes abbreviated pl., pl, or ), in many languages, is one of the values of the grammatical category of number. The plural of a noun typically denotes a quantity greater than the default quantity represented by that noun. This de ...

. A variety of plural suffixes is used, and the choice between them is partly determined by their ending in singular and partly influenced by gender; in addition, irregular declension and alternative plural forms are common. Words ending in (which are usually feminine) generally have the plural ending , upon dropping of the singular ending. Of nouns ending in a consonant, the feminine ones also use , whereas the masculine ones usually have for polysyllables and for monosyllables (however, exceptions are especially common in this group). Nouns ending in (most of which are neuter) mostly use the suffixes (both of which require the dropping of the singular endings) and .

With cardinal number

In mathematics, cardinal numbers, or cardinals for short, are a generalization of the natural numbers used to measure the cardinality (size) of sets. The cardinality of a finite set is a natural number: the number of elements in the set. Th ...

s and related words such as ('several'), masculine nouns use a special count form in , which stems from the Proto-Slavonic dual: ('two/three chairs') versus ('these chairs'); cf. feminine ('two/three/these books') and neuter ('two/three/these beds'). However, a recently developed language norm requires that count forms should only be used with masculine nouns that do not denote persons. Thus, ('two/three students') is perceived as more correct than , while the distinction is retained in cases such as ('two/three pencils') versus ('these pencils').

=Case

= Cases exist only in thepersonal

Personal may refer to:

Aspects of persons' respective individualities

* Privacy

* Personality

* Personal, personal advertisement, variety of classified advertisement used to find romance or friendship

Companies

* Personal, Inc., a Washington, ...

and some other pronoun

In linguistics and grammar, a pronoun (abbreviated ) is a word or a group of words that one may substitute for a noun or noun phrase.

Pronouns have traditionally been regarded as one of the parts of speech, but some modern theorists would not c ...

s (as they do in many other modern Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutc ...

), with nominative, accusative

The accusative case (abbreviated ) of a noun is the grammatical case used to mark the direct object of a transitive verb.

In the English language, the only words that occur in the accusative case are pronouns: 'me,' 'him,' 'her,' 'us,' and ‘th ...

, dative and vocative

In grammar, the vocative case (abbreviated ) is a grammatical case which is used for a noun that identifies a person (animal, object, etc.) being addressed, or occasionally for the noun modifiers (determiners, adjectives, participles, and numer ...

forms. Vestiges are present in a number of phraseological units and sayings. The major exception are vocative

In grammar, the vocative case (abbreviated ) is a grammatical case which is used for a noun that identifies a person (animal, object, etc.) being addressed, or occasionally for the noun modifiers (determiners, adjectives, participles, and numer ...

forms, which are still in use for masculine (with the endings -е, -о and -ю) and feminine nouns (- �/й� and -е) in the singular.

=Definiteness (article)

= In modern Bulgarian, definiteness is expressed by adefinite article

An article is any member of a class of dedicated words that are used with noun phrases to mark the identifiability of the referents of the noun phrases. The category of articles constitutes a part of speech.

In English, both "the" and "a(n)" ar ...

which is postfixed to the noun, much like in the Scandinavian languages

The North Germanic languages make up one of the three branches of the Germanic languages—a sub-family of the Indo-European languages—along with the West Germanic languages and the extinct East Germanic languages. The language group is also r ...

or Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

*** Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

** Romanian cuisine, tradition ...

(indefinite: , 'person'; definite: , "''the'' person") or to the first nominal constituent of definite noun phrases (indefinite: , 'a good person'; definite: , "''the'' good person"). There are four singular definite articles. Again, the choice between them is largely determined by the noun's ending in the singular. Nouns that end in a consonant and are masculine use –ът/–ят, when they are grammatical subject

The subject in a simple English sentence such as ''John runs'', ''John is a teacher'', or ''John drives a car'', is the person or thing about whom the statement is made, in this case ''John''. Traditionally the subject is the word or phrase whi ...

s, and –а/–я elsewhere. Nouns that end in a consonant and are feminine, as well as nouns that end in –а/–я (most of which are feminine, too) use –та. Nouns that end in –е/–о use –то.

The plural definite article is –те for all nouns except for those whose plural form ends in –а/–я; these get –та instead. When postfixed to adjectives the definite articles are –ят/–я for masculine gender (again, with the longer form being reserved for grammatical subjects), –та for feminine gender, –то for neuter gender, and –те for plural.

Adjective and numeral inflection

Both groups agree in gender and number with the noun they are appended to. They may also take the definite article as explained above.Pronouns

Pronouns may vary in gender, number, and definiteness, and are the only parts of speech that have retained case inflections. Three cases are exhibited by some groups of pronouns – nominative, accusative and dative. The distinguishable types of pronouns include the following: personal, relative, reflexive, interrogative, negative, indefinitive, summative and possessive.Verbal morphology and grammar

The Bulgarian verb can take up to 3,000 distinct forms, as it varies in person, number, voice, aspect, mood, tense and in some cases gender.Finite verbal forms

Finite verbal forms are ''simple'' or ''compound'' and agree with subjects in person (first, second and third) and number (singular, plural). In addition to that, past compound forms using participles vary in gender (masculine, feminine, neuter) and voice (active and passive) as well as aspect (perfective/aorist and imperfective).Aspect

Bulgarian verbs expresslexical aspect

In linguistics, the lexical aspect or Aktionsart (, plural ''Aktionsarten'' ) of a verb is part of the way in which that verb is structured in relation to time. For example, the English verbs ''arrive'' and ''run'' differ in their lexical aspect ...

: perfective verbs signify the completion of the action of the verb and form past perfective (aorist) forms; imperfective ones are neutral with regard to it and form past imperfective forms. Most Bulgarian verbs can be grouped in perfective-imperfective pairs (imperfective/perfective: "come", "arrive"). Perfective verbs can be usually formed from imperfective ones by suffixation or prefixation, but the resultant verb often deviates in meaning from the original. In the pair examples above, aspect is stem-specific and therefore there is no difference in meaning.

In Bulgarian, there is also grammatical aspect

In linguistics, aspect is a grammatical category that expresses how an action, event, or state, as denoted by a verb, extends over time. Perfective aspect is used in referring to an event conceived as bounded and unitary, without reference to ...

. Three grammatical aspects are distinguishable: neutral, perfect and pluperfect. The neutral aspect comprises the three simple tenses and the future tense. The pluperfect is manifest in tenses that use double or triple auxiliary "be" participles like the past pluperfect subjunctive. Perfect constructions use a single auxiliary "be".

Mood

The traditional interpretation is that in addition to the four moods (наклонения ) shared by most other European languages –indicative

A realis mood ( abbreviated ) is a grammatical mood which is used principally to indicate that something is a statement of fact; in other words, to express what the speaker considers to be a known state of affairs, as in declarative sentences. Mos ...

(изявително, ) imperative (повелително ), subjunctive ( ) and conditional (условно, ) – in Bulgarian there is one more to describe a general category of unwitnessed events – the inferential (преизказно ) mood. However, most contemporary Bulgarian linguists usually exclude the subjunctive mood and the inferential mood from the list of Bulgarian moods (thus placing the number of Bulgarian moods at a total of 3: indicative, imperative and conditional) and don't consider them to be moods but view them as verbial morphosyntactic constructs or separate gramemes of the verb class. The possible existence of a few other moods has been discussed in the literature. Most Bulgarian school grammars teach the traditional view of 4 Bulgarian moods (as described above, but excluding the subjunctive and including the inferential).

Tense

There are three grammatically distinctive positions in time – present, past and future – which combine with aspect and mood to produce a number of formations. Normally, in grammar books these formations are viewed as separate tenses – i. e. "past imperfect" would mean that the verb is in past tense, in the imperfective aspect, and in the indicative mood (since no other mood is shown). There are more than 40 different tenses across Bulgarian's two aspects and five moods. In the indicative mood, there are three simple tenses: *''Present tense'' is a temporally unmarked simple form made up of the verbal stem and a complex suffix composed of thethematic vowel

In Indo-European studies, a thematic vowel or theme vowel is the vowel or from ablaut placed before the ending of a Proto-Indo-European (PIE) word. Nouns, adjectives, and verbs in the Indo-European languages with this vowel are thematic, and tho ...

, or and the person/number ending (, , "I arrive/I am arriving"); only imperfective verbs can stand in the present indicative tense independently;

*''Past imperfect'' is a simple verb form used to express an action which is contemporaneous or subordinate to other past actions; it is made up of an imperfective or a perfective verbal stem and the person/number ending ( , , 'I was arriving');

*''Past aorist'' is a simple form used to express a temporarily independent, specific past action; it is made up of a perfective or an imperfective verbal stem and the person/number ending (, , 'I arrived', , , 'I read');

In the indicative there are also the following compound tenses:

*''Future tense'' is a compound form made of the particle and present tense ( , 'I will study'); negation is expressed by the construction and present tense ( , or the old-fashioned form , 'I will not study');

*''Past future tense'' is a compound form used to express an action which was to be completed in the past but was future as regards another past action; it is made up of the past imperfect of the verb ('will'), the particle ('to') and the present tense of the verb (e.g. , , 'I was going to study');

*''Present perfect'' is a compound form used to express an action which was completed in the past but is relevant for or related to the present; it is made up of the present tense of the verb съм ('be') and the past participle (e.g. , 'I have studied');

*''Past perfect'' is a compound form used to express an action which was completed in the past and is relative to another past action; it is made up of the past tense of the verb съм and the past participle (e.g. , 'I had studied');

*''Future perfect'' is a compound form used to express an action which is to take place in the future before another future action; it is made up of the future tense of the verb съм and the past participle (e.g. , 'I will have studied');

*''Past future perfect'' is a compound form used to express a past action which is future with respect to a past action which itself is prior to another past action; it is made up of the past imperfect of , the particle the present tense of the verb съм and the past participle of the verb (e.g. , , 'I would have studied').

The four perfect constructions above can vary in aspect depending on the aspect of the main-verb participle; they are in fact pairs of imperfective and perfective aspects. Verbs in forms using past participles also vary in voice and gender.

There is only one simple tense in the imperative mood

The imperative mood is a grammatical mood that forms a command or request.

The imperative mood is used to demand or require that an action be performed. It is usually found only in the present tense, second person. To form the imperative mood, ...

, the present, and there are simple forms only for the second-person singular, -и/-й (-i, -y/i), and plural, -ете/-йте (-ete, -yte), e.g. уча ('to study'): , sg., , pl.; 'to play': , . There are compound imperative forms for all persons and numbers in the present compound imperative (, ), the present perfect compound imperative (, ) and the rarely used present pluperfect compound imperative (, ).

The conditional mood The conditional mood ( abbreviated ) is a grammatical mood used in conditional sentences to express a proposition whose validity is dependent on some condition, possibly counterfactual.

It may refer to a distinct verb form that expresses the condit ...

consists of five compound tenses, most of which are not grammatically distinguishable. The present, future and past conditional use a special past form of the stem би- (bi – "be") and the past participle (, , 'I would study'). The past future conditional and the past future perfect conditional coincide in form with the respective indicative tenses.

The subjunctive mood is rarely documented as a separate verb form in Bulgarian, (being, morphologically, a sub-instance of the quasi-infinitive

Infinitive (abbreviated ) is a linguistics term for certain verb forms existing in many languages, most often used as non-finite verbs. As with many linguistic concepts, there is not a single definition applicable to all languages. The word is deri ...

construction with the particle да and a normal finite verb form), but nevertheless it is used regularly. The most common form, often mistaken for the present tense, is the present subjunctive ( , 'I had better go'). The difference between the present indicative and the present subjunctive tense is that the subjunctive can be formed by ''both'' perfective and imperfective verbs. It has completely replaced the infinitive and the supine from complex expressions (see below). It is also employed to express opinion about ''possible'' future events. The past perfect subjunctive ( , 'I'd had better be gone') refers to ''possible'' events in the past, which ''did not'' take place, and the present pluperfect subjunctive ( ), which may be used about both past and future events arousing feelings of incontinence, suspicion, etc.

The inferential mood

The inferential mood (abbreviated or ) is used to report a nonwitnessed event without confirming it, but the same forms also function as admiratives in the Balkan languages (namely Albanian, Bulgarian, Macedonian and Turkish) in which they oc ...

has five pure tenses. Two of them are simple – ''past aorist inferential'' and ''past imperfect inferential'' – and are formed by the past participles of perfective and imperfective verbs, respectively. There are also three compound tenses – ''past future inferential'', ''past future perfect inferential'' and ''past perfect inferential''. All these tenses' forms are gender-specific in the singular. There are also conditional and compound-imperative crossovers. The existence of inferential forms has been attributed to Turkic influences by most Bulgarian linguists. Morphologically, they are derived from the perfect.

Non-finite verbal forms

Bulgarian has the followingparticiple

In linguistics, a participle () (from Latin ' a "sharing, partaking") is a nonfinite verb form that has some of the characteristics and functions of both verbs and adjectives. More narrowly, ''participle'' has been defined as "a word derived from ...

s:

*''Present active participle'' (сегашно деятелно причастие) is formed from imperfective stems with the addition of the suffixes –ащ/–ещ/–ящ (четящ, 'reading') and is used only attributively;

*''Present passive participle'' (сегашно страдателно причастие) is formed by the addition of the suffixes -им/аем/уем (четим, 'that can be read, readable');

*''Past active aorist participle'' (минало свършено деятелно причастие) is formed by the addition of the suffix –л– to perfective stems (чел, 'ave

''Alta Velocidad Española'' (''AVE'') is a service of high-speed rail in Spain operated by Renfe, the Spanish national railway company, at speeds of up to . As of December 2021, the Spanish high-speed rail network, on part of which the AVE s ...

read');

*''Past active imperfect participle'' (минало несвършено деятелно причастие) is formed by the addition of the suffixes –ел/–ал/–ял to imperfective stems (четял, ' ave beenreading');

*''Past passive aorist participle (минало свършено страдателно причастие) is formed from aorist/perfective stems with the addition of the suffixes -н/–т (прочетен, 'read'; убит, 'killed'); it is used predicatively and attributively;

*''Past passive imperfect participle (минало несвършено страдателно причастие) is formed from imperfective stems with the addition of the suffix –н (прочитан, ' eenread'; убиван, ' eenbeing killed'); it is used predicatively and attributively;

*''Adverbial participle

In linguistics, a participle () (from Latin ' a "sharing, partaking") is a nonfinite verb form that has some of the characteristics and functions of both verbs and adjectives. More narrowly, ''participle'' has been defined as "a word derived from ...

'' (деепричастие) is usually formed from imperfective present stems with the suffix –(е)йки (четейки, 'while reading'), relates an action contemporaneous with and subordinate to the main verb and is originally a Western Bulgarian form.

The participles are inflected by gender, number, and definiteness, and are coordinated with the subject when forming compound tenses (see tenses above). When used in an attributive role, the inflection attributes are coordinated with the noun that is being attributed.

Reflexive verbs

Bulgarian usesreflexive verb

In grammar, a reflexive verb is, loosely, a verb whose direct object is the same as its subject; for example, "I wash myself". More generally, a reflexive verb has the same semantic agent and patient (typically represented syntactically by the s ...

al forms (i.e. actions which are performed by the agent

Agent may refer to:

Espionage, investigation, and law

*, spies or intelligence officers

* Law of agency, laws involving a person authorized to act on behalf of another

** Agent of record, a person with a contractual agreement with an insuranc ...

onto him- or herself) which behave in a similar way as they do in many other Indo-European languages, such as French and Spanish. The reflexive is expressed by the invariable particle ''se'',Unlike in French and Spanish, where ''se'' is only used for the 3rd person, and other particles, such as ''me'' and ''te'', are used for the 1st and 2nd persons singular, e.g. ''je me lave/me lavo'' – I wash myself. originally a clitic form of the accusative reflexive pronoun. Thus –

*''miya'' – I wash, ''miya se'' – I wash myself, ''miesh se'' – you wash yourself

*''pitam'' – I ask, ''pitam se'' – I ask myself, ''pitash se'' – you ask yourself

When the action is performed on others, other particles are used, just like in any normal verb, e.g. –

*''miya te'' – I wash you

*''pitash me'' – you ask me

Sometimes, the reflexive verb form has a similar but not necessarily identical meaning to the non-reflexive verb –

*''kazvam'' – I say, ''kazvam se'' – my name is (lit. "I call myself")

*''vizhdam'' – I see, ''vizhdame se'' – "we see ourselves" ''or'' "we meet each other"

In other cases, the reflexive verb has a completely different meaning from its non-reflexive counterpart –

*''karam'' – to drive, ''karam se'' – to have a row with someone

*''gotvya'' – to cook, ''gotvya se'' – to get ready

*''smeya'' – to dare, ''smeya se'' – to laugh

;Indirect actions

When the action is performed on an indirect object, the particles change to ''si'' and its derivatives –

*''kazvam si'' – I say to myself, ''kazvash si'' – you say to yourself, ''kazvam ti'' – I say to you

*''peya si'' – I am singing to myself, ''pee si'' – she is singing to herself, ''pee mu'' – she is singing to him

*''gotvya si'' – I cook for myself, ''gotvyat si'' – they cook for themselves, ''gotvya im'' – I cook for them

In some cases, the particle ''si'' is ambiguous between the indirect object and the possessive meaning –

*''miya si ratsete'' – I wash my hands, ''miya ti ratsete'' – I wash your hands

*''pitam si priyatelite'' – I ask my friends, ''pitam ti priyatelite'' – I ask your friends

*''iskam si topkata – I want my ball (back)

The difference between transitive and intransitive verbs can lead to significant differences in meaning with minimal change, e.g. –

*''haresvash me'' – you like me, ''haresvash mi'' – I like you (lit. you are pleasing to me)

*''otivam'' – I am going, ''otivam si'' – I am going home

The particle ''si'' is often used to indicate a more personal relationship to the action, e.g. –

*''haresvam go'' – I like him, ''haresvam si go'' – no precise translation, roughly translates as "he's really close to my heart"

*''stanahme priyateli'' – we became friends, ''stanahme si priyateli'' – same meaning, but sounds friendlier

*''mislya'' – I am thinking (usually about something serious), ''mislya si'' – same meaning, but usually about something personal and/or trivial

Adverbs

The mostproductive

Productivity is the efficiency of production of goods or services expressed by some measure. Measurements of productivity are often expressed as a ratio of an aggregate output to a single input or an aggregate input used in a production proces ...

way to form adverbs is to derive them from the neuter singular form of the corresponding adjective—e.g. (fast), (hard), (strange)—but adjectives ending in use the masculine singular form (i.e. ending in ), instead—e.g. (heroically), (bravely, like a man), (skillfully). The same pattern is used to form adverbs from the (adjective-like) ordinal numerals, e.g. (firstly), (secondly), (thirdly), and in some cases from (adjective-like) cardinal numerals, e.g. (twice as/double), (three times as), (five times as).

The remaining adverbs are formed in ways that are no longer productive in the language. A small number are original (not derived from other words), for example: (here), (there), (inside), (outside), (very/much) etc. The rest are mostly fossilized case forms, such as:

*Archaic locative forms of some adjectives, e.g. (well), (badly), (too, rather), and nouns (up), (tomorrow), (in the summer)

*Archaic instrumental forms of some adjectives, e.g. (quietly), (furtively), (blindly), and nouns, e.g. (during the day), (during the night), (one next to the other), (spiritually), (in figures), (with words); or verbs: (while running), (while lying), (while standing)

*Archaic accusative forms of some nouns: (today), (tonight), (in the morning), (in winter)

*Archaic genitive forms of some nouns: (tonight), (last night), (yesterday)

*Homonymous and etymologically identical to the feminine singular form of the corresponding adjective used with the definite article: (hard), (gropingly); the same pattern has been applied to some verbs, e.g. (while running), (while lying), (while standing)

*Derived from cardinal numerals by means of a non-productive suffix: (once), (twice), (thrice)

Adverbs can sometimes be reduplicated to emphasize the qualitative or quantitative properties of actions, moods or relations as performed by the subject of the sentence: "" ("rather slowly"), "" ("with great difficulty"), "" ("quite", "thoroughly").

Syntax

Bulgarian employs clitic doubling, mostly for emphatic purposes. For example, the following constructions are common in colloquial Bulgarian: : :(lit. "I gave ''it'' the present to Maria.") : :(lit. "I gave ''her it'' the present to Maria.") The phenomenon is practically obligatory in the spoken language in the case of inversion signalling information structure (in writing, clitic doubling may be skipped in such instances, with a somewhat bookish effect): : :(lit. "The present 'to her''''it'' I-gave to Maria.") : :(lit. "To Maria ''to her'' 'it''I-gave the present.") Sometimes, the doubling signals syntactic relations, thus: : :(lit. "Petar and Ivan ''them'' ate the wolves.") :Transl.: "Petar and Ivan were eaten by the wolves". This is contrasted with: : :(lit. "Petar and Ivan ate the wolves") :Transl.: "Petar and Ivan ate the wolves". In this case, clitic doubling can be a colloquial alternative of the more formal or bookish passive voice, which would be constructed as follows: : :(lit. "Petar and Ivan were eaten by the wolves.") Clitic doubling is also fully obligatory, both in the spoken and in the written norm, in clauses including several special expressions that use the short accusative and dative pronouns such as "" (I feel like playing), студено ми е (I am cold), and боли ме ръката (my arm hurts): : :(lit. "To me ''to me'' it-feels-like-sleeping, and to Ivan ''to him'' it-feels-like-playing") :Transl.: "I feel like sleeping, and Ivan feels like playing." : :(lit. "To us ''to us'' it-is cold, and to you-plur. ''to you-plur.'' it-is warm") :Transl.: "We are cold, and you are warm." : :(lit. Ivan ''him'' aches the throat, and me ''me'' aches the head) :Transl.: Ivan has sore throat, and I have a headache. Except the above examples, clitic doubling is considered inappropriate in a formal context.Other features

Questions