Buildwas Abbey on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Buildwas Abbey was a

Buildwas Abbey was a

Buildwas Abbey was a

The Four Minsters Round the Wrekin, p. 10.

/ref> Buildwas manor was land previously belonging to the

''Monasticon Anglicanum'', volume 5, p. 359, no. 16.

/ref> Edric's rôle is not specified but presumably involved some kind of work on the abbey's behalf in the diocesan centre. The earlier confirmation by King Stephen, issued apparently while he was involved in the

Antiquities of Shropshire, volume 2, p. 203.

/ref> The grant is not dated but makes clear that the abbey was still part of the Savigniac community, as it committed all Savigniac houses to pray for Philip, Matilda and their family. The Savigniac houses were all absorbed into the Cistercian order in 1147, and the merger was confirmed by a

''Monasticon Anglicanum'', volume 5, p. 359, no. 18.

/ref> Ingenulf, the first abbot, was fairly obscure, but the abbey entered a period of growth and development under Abbot Ranulf, who is known to have taken over by 1155, since a charter relating to Lilleshall which he witnessed cannot be later than that year. His abbacy coincided very closely with the reign of Henry II.

In 1154

In 1154

Bishop Richard Peche probably granted the house at Chester Foregate to Buildwas so that Abbot Ranulf could more easily discharge his responsibilities in Ireland. In 1183–4 Gilbert Pipard, the guardian of Chester, filed a claim for expenses of four shillings for arranging the passage of the abbot of Buildwas to Ireland, making clear that Ranulf did sail to Dublin from Chester, easily reached via

Bishop Richard Peche probably granted the house at Chester Foregate to Buildwas so that Abbot Ranulf could more easily discharge his responsibilities in Ireland. In 1183–4 Gilbert Pipard, the guardian of Chester, filed a claim for expenses of four shillings for arranging the passage of the abbot of Buildwas to Ireland, making clear that Ranulf did sail to Dublin from Chester, easily reached via

''Monasticon Anglicanum'', volume 5, p. 362.

/ref> Ranulf seems to have travelled a great deal, and the chronicler of

House of Cistercian monks: Abbey of Buildwas, note anchor 24.

/ref> As a result, it became part of a group of large Shropshire monasteries whose estates bore comparison with the great aristocratic families in the county.Cox et al. D. C

Domesday Book: 1300-1540, note anchor 61

/ref> There were peak periods of acquisition in the 1240s and 1280s, as can be seen in the table below. The map based on the table demonstrates how Buildwas built up a concentrated belt of granges along the Rivers Severn and Worfe and the Shropshire-Staffordshire border, all quickly accessible from the abbey by routes that took full advantage of the River Severn itself. This was not an accident but a consequence of observing the Cistercian precept that granges should be within a

Antiquities of Shropshire, volume 6, p. 75.

/ref> of the

''Monasticon Anglicanum'', volume 5, pp. 356-7, no. 2.

/ref> However, it seems Gilbert was in debt and in no position to make the grant. He had used the land as security for a loan from Ursell, son of Hamo of

Antiquities of Shropshire, volume 6, p. 312.

/ref> In 1255 the Hundred Roll records the abbey as holding one hide at Harnage. By 1291 the abbey held the whole of Harnage, assessed at four

''Monasticon Anglicanum'', volume 5, p. 360, no. 24.

/ref> In 1292, under

In 1292, under

Growth of English Industry and Commerce, p. 632.

/ref> He valued its wool at 20 marks a sack for the best, 12 marks for medium, and 10 marks for broken wool. Although the 13th and early 14th centuries were the great age of demesne farming, Buildwas always acquired some income from rents and

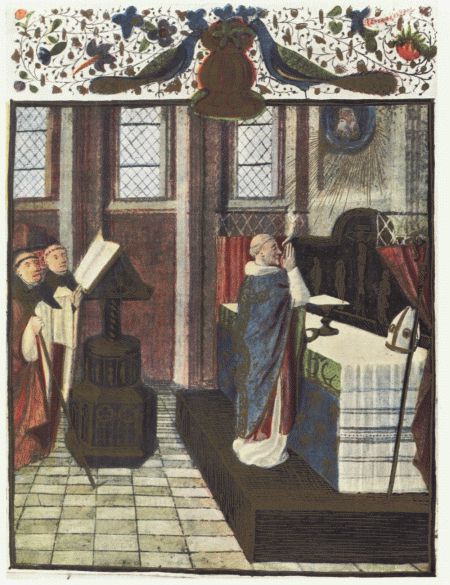

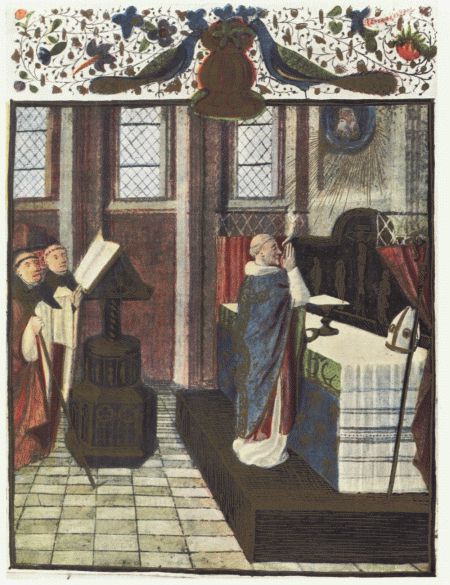

Monks generally pursued their education and spiritual development as far as the priesthood. There were plenty of opportunities to preside over the

Monks generally pursued their education and spiritual development as far as the priesthood. There were plenty of opportunities to preside over the

The most sensational series episodes in the history of the abbey began with a typical overseas mission undertaken by an abbot. On 24 April 1342, Edward III granted protection for one year for the abbot, whose name is unknown, to make a visitation of Cistercian houses in Ireland. At this time the daughter house at Dublin was locked in a quarrel with Dunbrody Abbey, which had refused to accept its jurisdiction in 1340. By July 1342 the authority of Philip Wafre, the abbot of St Mary's Abbey, a Shropshire man, had been recognised by other Cistercian houses in Ireland. However, the abbot of Buildwas was murdered at about this time and on 16 September 1342 a royal commission was issued for the arrest of Thomas of Tonge, who had been indicted in Shropshire for the murder of his abbot and was now at large in secular clothing. The king ordered that he be detained in Shrewsbury gaol In view of the length of the protection afforded by the king to the abbot, it seems likely that the death had occurred in Ireland and that Thomas had left the scene. It is impossible now to ascertain Thomas of Tonge's rôle in or connection with the dispute in Ireland. He maintained his innocence throughout and there can be no certainty even that a murder was committed. In December 1443 Thomas succeeded in obtaining intervention by

The most sensational series episodes in the history of the abbey began with a typical overseas mission undertaken by an abbot. On 24 April 1342, Edward III granted protection for one year for the abbot, whose name is unknown, to make a visitation of Cistercian houses in Ireland. At this time the daughter house at Dublin was locked in a quarrel with Dunbrody Abbey, which had refused to accept its jurisdiction in 1340. By July 1342 the authority of Philip Wafre, the abbot of St Mary's Abbey, a Shropshire man, had been recognised by other Cistercian houses in Ireland. However, the abbot of Buildwas was murdered at about this time and on 16 September 1342 a royal commission was issued for the arrest of Thomas of Tonge, who had been indicted in Shropshire for the murder of his abbot and was now at large in secular clothing. The king ordered that he be detained in Shrewsbury gaol In view of the length of the protection afforded by the king to the abbot, it seems likely that the death had occurred in Ireland and that Thomas had left the scene. It is impossible now to ascertain Thomas of Tonge's rôle in or connection with the dispute in Ireland. He maintained his innocence throughout and there can be no certainty even that a murder was committed. In December 1443 Thomas succeeded in obtaining intervention by

/ref> The parties were issuing their own

/ref> The following month he paid 20 shillings to the king for permission to make a deal with the powerful Arundel. This granted to Arundel in fee the manors of Kinnerton, Ryton and Stirchley in exchange for the church of Cound in Leighton. This looks like an attempt to get out of demesne farming but there is a gross disparity between the two sides in the exchange. Cound church never appears among the spiritualities of Buildwas so the exchange is most likely to be part of the complex web of legal fictions woven by Arundel to protect the

Changes in the Grange Economy of English and Welsh Cistercian Abbeys, 1300–1540, p. 420-1.

/ref> In 1302

''Monasticon Anglicanum'', volume 5, p. 361, no. 25.

/ref> continually use the terms ''firma'' (farm) and ''redditus'' (rent) for the revenues of Buildwas: although flexible in use, both indicate some form of rental or leasing agreement. This change made the abbey increasingly dependent on the market economy. Food for example, often had to be bought, rather than home produced. Sometimes barter was employed to secure supplies: in 1521 the abbot was forced to obtain eight beef cattle and forty cheeses by assigning all the timber in a wood called Swallotaylle to Robert Hood of Acton Pigott. Ordinary paid labour replaced the lay brothers who had previously shouldered both manual and managerial tasks.

Buildwas Parish Register, p. iv.

/ref> Lord Powis had no legitimate issue but he did have a family by his long-term mistress Jane Orwell, daughter of Sir Lewis Orwell of

Herbert, John (c.1515-83 or later), of London, Buildwas, Salop and Welshpool, Mont.

History of Parliament Online. which must have been adapted from the mid 16th century to provide the normal amenities of a substantial private house. The abbot's house and parts of the infirmary court were remodelled over time to become Abbey House, now a building distinct from the abbey ruin and listed separately by Historic England. John Herbert had important court and political connections through his cousin William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke, the husband of Anne Parr, Catherine Parry’s sister, and a sometimes erratic Protestant soldier who just managed to stay out of trouble during Queen Mary's reign. On 15 January 1559, the coronation day of

/ref> Grey's estates were the subject of protracted litigation after his death, although he had

There are indications that the abbey needed fairly frequent maintenance even when in use. In 1232, for example, Henry III at Bridgnorth was persuaded to donate thirty oak trees from the nearby

There are indications that the abbey needed fairly frequent maintenance even when in use. In 1232, for example, Henry III at Bridgnorth was persuaded to donate thirty oak trees from the nearby

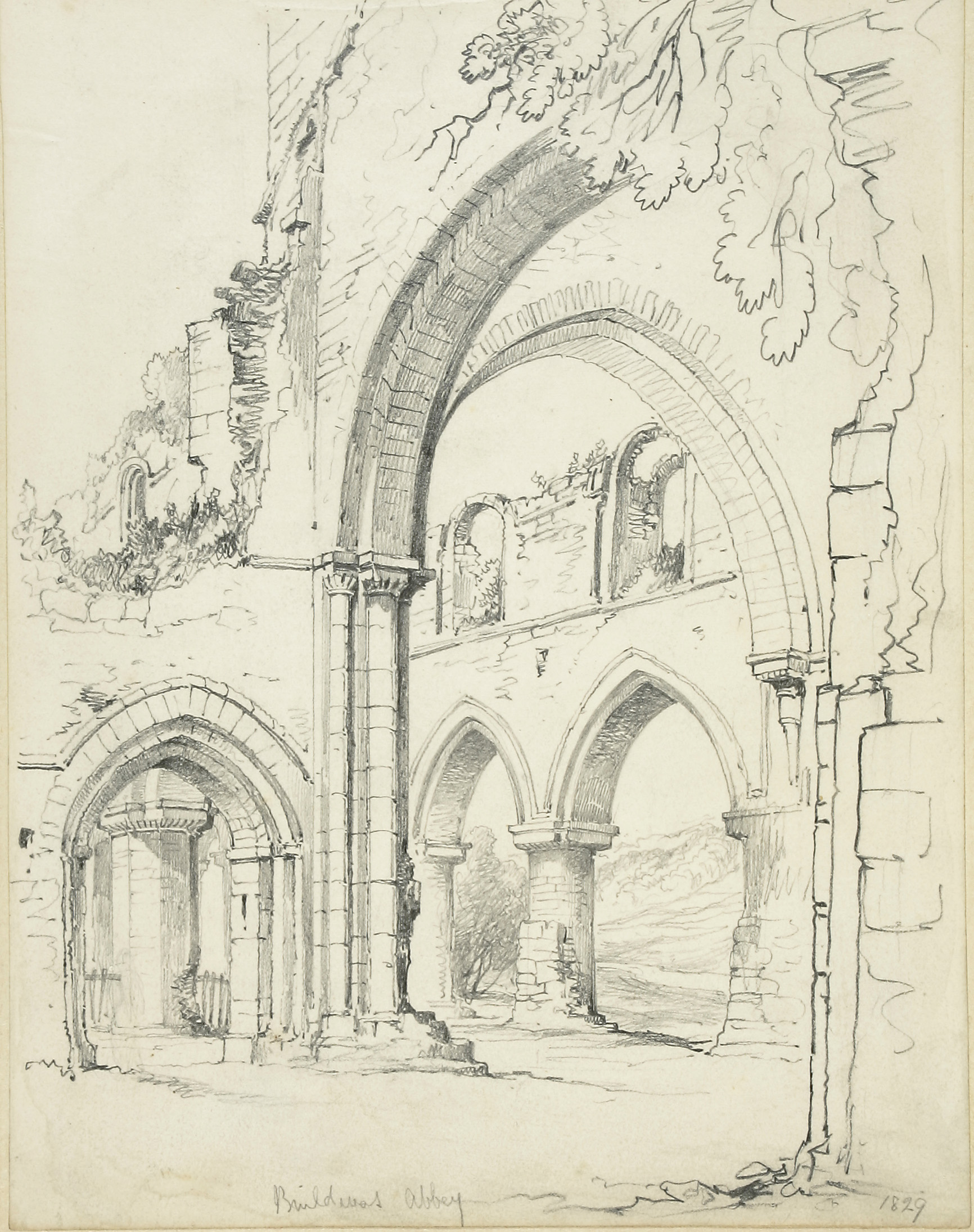

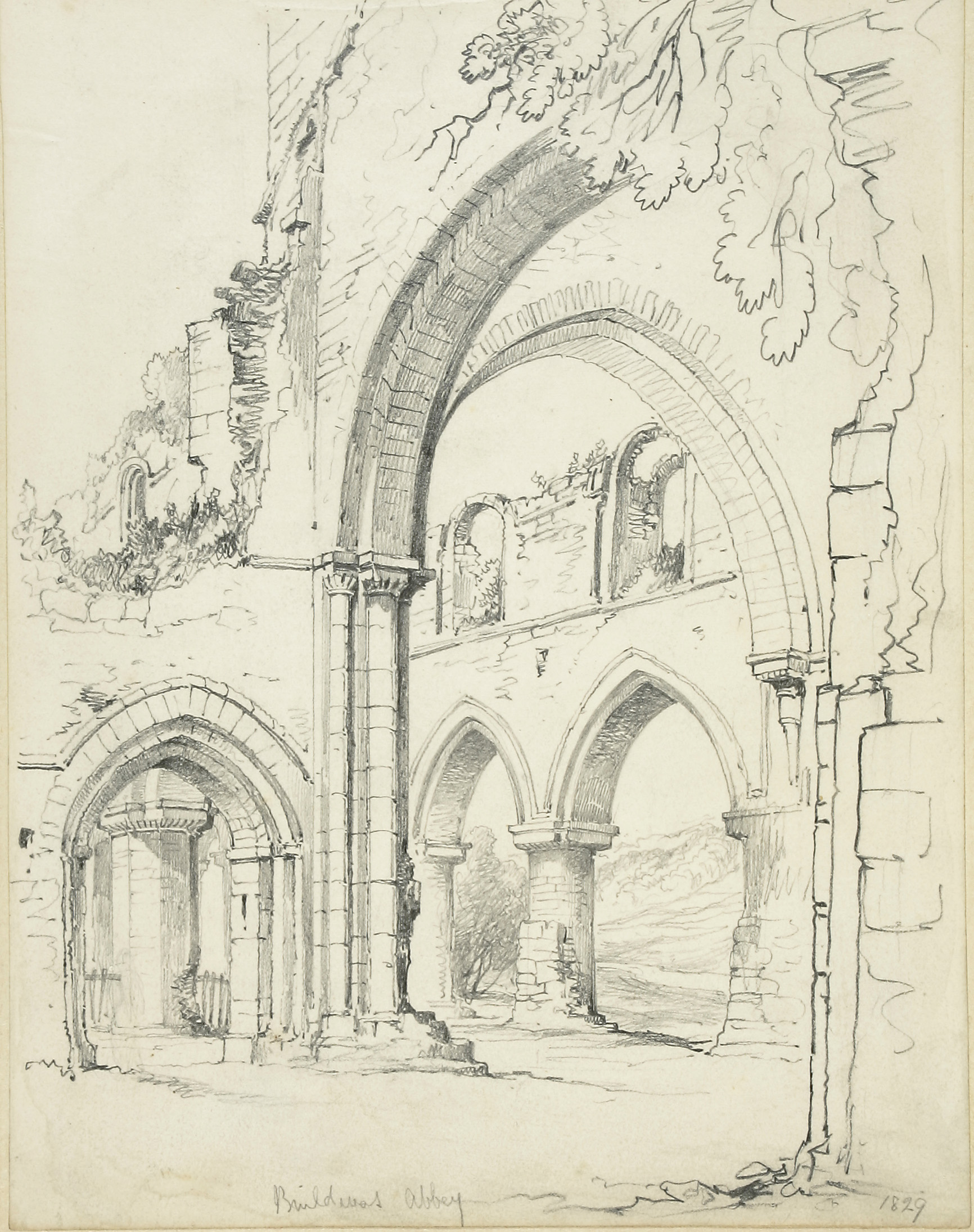

The abbey site is ashort distance south of the River Severn. The drainage opportunities afforded by the river made it sensible to place the claustral buildings to the north of the church, which is roughly parallel to the river, and so fairly accurately oriented. The remains of the buildings are entirely of local

The abbey site is ashort distance south of the River Severn. The drainage opportunities afforded by the river made it sensible to place the claustral buildings to the north of the church, which is roughly parallel to the river, and so fairly accurately oriented. The remains of the buildings are entirely of local

File:Buildwas Abbey - nave from south west.jpg, Exterior view of the nave from the south west, showing the bluntly pointed arches. Central tower to right.

File:Buildwas Abbey - aisle wall foundation.jpg, The south west corner of the church, showing all that remains of the abbey's aisle walls and a section of foundation.

File:Buildwas Abbey - nave from north west.jpg, Exterior view of the nave from the north west, showing the massive round-section columns and a doorway into the north transept.

File:Buildwas Abbey - columns north nave.jpg, Arches on the north side of the nave, featuring round-sectioned columns with scalloped capitals.

File:Buildwas Abbey - capital north nave.jpg, Capital of a column in the north nave, showing scalloped decoration. Above it a

The quire or monk's choir took up the two eastern bays of the nave as well as the crossing. The western foundation of the

File:Buildwas Abbey - central tower from south west 01.jpg, Roof lantern or central tower, viewed from the south west.

File:Buildwas Abbey - church from west.jpg, View of the church interior, with the triple window in the eastern wall of the chancel, viewed through the arches supporting the central tower.

File:Buildwas Abbey - clerestory from chancel.jpg, The north clerestory of the chancel or presbytery viewed from inside the building.

File:Buildwas Abbey Eyton 6-334 Sedilia.png, The triple sedilia in the presbytery. From Eyton, R. W. ''Antiquities of Shropshire'', volume 6.

File:Buildwas Abbey - piscina.jpg, Piscina or wash drain for ritual ablutions in the south wall of the chancel or presbytery.

File:Buildwas Abbey - south transept chapels.jpg, Exterior view through entrances of the two chapels in the south transept.

File:Buildwas Abbey - north transept chapels.jpg, The north transept chapels.

File:Buildwas Abbey - chapel piscina.jpg, A piscina or drain for washing the eucharistic vessels in the wall of a side chapel in one of the transepts.

File:Buildwas Abbey - cloister from north.jpg, The cloister court, including the sacristy and chapter house, viewed from the north, over the remains of the lay brothers' range.

File:Buildwas Abbey-cloister south-sacristy-chapter house.jpg, The east range of the cloister. From left: the parlour entrance; two west windows and door of chapter house; sacristy entrance.

File:Buildwas Abbey - sacristy through cloister entrance.jpg, A view of the sacristy through the entrance from the cloister.

File:Buildwas Abbey - sacristy ambry.jpg, Recess for an ambry, a cupboard used for book storage, in the sacristy.

File:Buildwas Abbey - sacristy roof.jpg, The roof of the sacristy, groin vaulted in two bays.

File:Buildwas Abbey - sacristy through cloister entrance.jpg, The sacristy seen through the entrance from the cloister, with an external exit that was originally a window.

File:Buildwas Abbey - sacristy ambry 2.jpg, The other ambry recess in the sacristy.

File:Buildwas Abbey - chapter house window cloister 1.jpg, One of the two windows in the cloister wall of the chapter house.

File:Buildwas Abbey - chapter house roof.jpg, Ribbed vaulting on the roof of the chapter house.

File:Buildwas Abbey - chapter house capital.jpg, A capital of one of the four columns supporting the rib vaulted roof of the chapter house.

File:Buildwas Abbey - chapter house roof external windows.jpg, View of the chapter house, showing the three remaining windows in the east wall.

File:Buildwas Abbey - chapter house floor.jpg, Decorated tiles restored to the chapter house floor.

File:Buildwas Abbey - chapter house tomb.jpg, Outline of a tomb in the floor of the chapter house.

File:Buildwas Abbey Eyton 6-334 Chapter House.png, The chapter house as seen in 1858. Internal view from the east end.

File:Buildwas Abbey - parlour - cloister entrance.jpg, Segmental arched doorway to the parlour from the cloister.

File:Buildwas Abbey - lay brothers range and gap.jpg, Undercroft of lay brother's range and gap giving entrance to cloister, showing how the building lay behind the cloister itself.

File:Buildwas Abbey - lay brotherss range.jpg, Remains of the lay brothers' range to the west of the cloister, showing the substantial undercroft.

The sacristy, intended to house

The Four Minsters Round the Wrekin, p. 22.

/ref> The tiled floor was removed after the dissolution but is now partly restored. The parlour provided the monks with a room where conversation was allowed. It has a roof made up of two bays of ribbed vaulting. Its entrance from the cloister is through a doorway with a semi-circular arch and there are two further doorways: one in the east wall leading to the exterior and one in the north wall to the

Listing for Buildwas Abbey

at

Listing for Abbey House

at

Buildwas Abbey

(English Heritage website)

* ttps://archive.today/20121223220540/http://pastscape.english-heritage.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=72110 Pastscape page. {{authority control 1135 establishments in England Religious organizations established in the 1130s 1536 disestablishments in England Cistercian monasteries in England English Heritage sites in Shropshire Grade I listed buildings in Shropshire Grade I listed monasteries Monasteries in Shropshire Ruins in Shropshire River Severn Christian monasteries established in the 12th century Ironbridge Gorge Monasteries dissolved under the English Reformation

Cistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

(originally Savigniac

The monastic Congregation of Savigny (Savigniac Order) started in the abbey of Savigny, situated in northern France, on the confines of Normandy and Brittany, in the Diocese of Coutances. It originated in 1105 when Vitalis of Mortain established ...

) monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

located on the banks of the River Severn

, name_etymology =

, image = SevernFromCastleCB.JPG

, image_size = 288

, image_caption = The river seen from Shrewsbury Castle

, map = RiverSevernMap.jpg

, map_size = 288

, map_c ...

, at Buildwas

Buildwas is a village and civil parish in Shropshire, England, on the north bank of the River Severn at . It lies on the B4380 road between Atcham and Ironbridge. The Royal Mail postcodes begin TF6 and TF8.

Buildwas Primary Academy is situa ...

, Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to th ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

- today about two miles (3 km) west of Ironbridge

Ironbridge is a large village in the borough of Telford and Wrekin in Shropshire, England. Located on the bank of the River Severn, at the heart of the Ironbridge Gorge, it lies in the civil parish of The Gorge. Ironbridge developed beside, a ...

. Founded by the local bishop in 1135, it was sparsely endowed at the outset but enjoyed several periods of growth and increasing wealth: notably under Abbot Ranulf in the second half of the 12th century and again from the mid-13th century, when large numbers of acquisitions were made from the local landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the ''gentry'', is a largely historical British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. While distinct from, and socially below, the British peerage, th ...

. Abbots were regularly used as agents by Plantagenet

The House of Plantagenet () was a royal house which originated from the lands of Anjou in France. The family held the English throne from 1154 (with the accession of Henry II at the end of the Anarchy) to 1485, when Richard III died in batt ...

in their attempts to subdue Ireland and Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

and the abbey acquired a daughter house

A dependency, among monastic orders, denotes the relation of a monastic community with a newer community which it has founded elsewhere. The relationship is that of the founding abbey or conventual priory, termed the motherhouse, with a monaster ...

in each country. It was a centre of learning, with a substantial library, and was noted for its discipline until the economic and demographic crises of the 14th century brought about decline and difficulties, exacerbated by conflict and political instability in the Welsh Marches

The Welsh Marches ( cy, Y Mers) is an imprecisely defined area along the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods.

The English term Welsh March (in Medieval Latin ...

. The abbey was suppressed in 1536 as part of the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

. Substantial remains of the abbey church and monk's quarters remain and are in the care of English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

.

Foundation

Buildwas Abbey was a

Buildwas Abbey was a Cistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

house, although originally founded as a Savigniac

The monastic Congregation of Savigny (Savigniac Order) started in the abbey of Savigny, situated in northern France, on the confines of Normandy and Brittany, in the Diocese of Coutances. It originated in 1105 when Vitalis of Mortain established ...

monastery in 1135 by Roger de Clinton

Roger de Clinton (died 1148) was a medieval Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield. He was responsible for organising a new grid street plan for the town of Lichfield in the 12th century which survives to this day.

Life

Clinton was the nephew of Geof ...

(1129–1148), Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield

The Bishop of Lichfield is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Lichfield in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers 4,516 km2 (1,744 sq. mi.) of the counties of Powys, Staffordshire, Shropshire, Warwickshire and West M ...

. The short-lived Savigniac congregation was a reformed and ascetic branch of the Benedictine Order

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

, centred on the Abbey of Savigny

Savigny Abbey (''Abbaye de Savigny'') was a monastery near the village of Savigny-le-Vieux (Manche), in northern France. It was founded early in the 12th century. Initially it was the central house of the Congregation of Savigny, who were Benedi ...

in Normandy, and dating only from 1112.WalcottThe Four Minsters Round the Wrekin, p. 10.

/ref> Buildwas manor was land previously belonging to the

diocese

In Ecclesiastical polity, church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided Roman province, pro ...

. In the Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

the manor of Buildwas was assessed as one hide and was home to nine households, five of them headed by slaves, four by villein

A villein, otherwise known as ''cottar'' or ''crofter'', is a serf tied to the land in the feudal system. Villeins had more rights and social status than those in slavery, but were under a number of legal restrictions which differentiated them ...

s and one by the reeve. It had a mill and woodland, with 200 pigs. It was then worth 45 shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence o ...

s, as before the Norman Conquest of England

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Normans, Norman, Duchy of Brittany, Breton, County of Flanders, Flemish, and Kingdom of France, French troops, ...

, although the value had slipped a little in the intervening period. The dedication of the abbey was to St Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of ...

and St Chad

Chad of Mercia (died 2 March 672) was a prominent 7th-century Anglo-Saxon Catholic monk who became abbot of several monasteries, Bishop of the Northumbrians and subsequently Bishop of the Mercians and Lindsey People. He was later canonised ...

: the same as Lichfield Cathedral

Lichfield Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Lichfield, Staffordshire, England, one of only three cathedrals in the United Kingdom with three spires (together with Truro Cathedral and St Mary's Cathedral in Edinburgh), and the only medie ...

. The foundation charter itself has been lost, but a poor transcription survives among the manuscripts of Roger Dodsworth

Roger Dodsworth (1585–1654) was an English antiquary.

Life

He was born at Newton Grange, Oswaldkirk, near Helmsley, Yorkshire, in the house of his maternal grandfather, Ralph Sandwith. He devoted himself early to antiquarian research, in wh ...

, now in the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second- ...

. This was printed by Robert William Eyton

Robert William Eyton (21 December 1815 – 8 September 1881) was an English Church of England clergyman who was author of ''The Antiquities of Shropshire''.

Life and career

Robert William Eyton was born in 1815. He was the son of Reverend John Eyt ...

, the great Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to th ...

antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary () is an fan (person), aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artifact (archaeology), artifac ...

, who considered that the list of witnesses, including parties who were soon afterwards drawn into the civil strife

Civil disorder, also known as civil disturbance, civil unrest, or social unrest is a situation arising from a mass act of civil disobedience (such as a demonstration, riot, strike, or unlawful assembly) in which law enforcement has difficulty ...

of King Stephen's reign on opposing sides, was designed to suggest an early date for the document – an impression he considered false. The first abbot is named as Ingenulf. The transcript omits details of the bishop's grants to the new abbey. However, these are listed in a confirmation issued by Richard I

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was ...

. Like the transcript, this addresses Roger de Clinton as Bishop of Chester

The Bishop of Chester is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chester in the Province of York.

The diocese extends across most of the historic county boundaries of Cheshire, including the Wirral Peninsula and has its see in the C ...

and states that his donation was of Buildwas itself, with its surrounding woodland, assart

Assarting is the act of clearing forested lands for use in agriculture or other purposes. In English land law, it was illegal to assart any part of a royal forest without permission. This was the greatest trespass that could be committed in a ...

s and appurtenances; land at Meole, just south of Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

, with its burgesses and a due (tax) called ''greffegh''; churchscot, a due for the support of the clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, from the hundreds of Condover

Condover is a village and civil parish in Shropshire, England. It is about south of the county town of Shrewsbury, and just east of the A49. The Cound Brook flows through the village on its way from the Stretton Hills to a confluence with the R ...

and Wrockwardine

Wrockwardine (pronounced "Rock-war-deen/dyne") is a village and civil parish in the borough of Telford and Wrekin and ceremonial county of Shropshire, England. It lies north of The Wrekin and the M54/ A5, and west of Wellington.

There is a Chur ...

; ''et in territorio Licheffelddensi hominem unum nomine Edricum'' ("in the territory of Lichfield

Lichfield () is a cathedral city and civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated roughly south-east of the county town of Stafford, south-east of Rugeley, north-east of Walsall, north-west of Tamworth and south-west of B ...

one man named Edric").Dugdale''Monasticon Anglicanum'', volume 5, p. 359, no. 16.

/ref> Edric's rôle is not specified but presumably involved some kind of work on the abbey's behalf in the diocesan centre. The earlier confirmation by King Stephen, issued apparently while he was involved in the

siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

of Shrewsbury in 1138, gave few details of the grants, although it did give the size of the site as one hide, as in Domesday. Instead it concentrated on recognising the abbey's immunity from taxes and other exactions, including scot and lot

Scot and lot is a phrase common in the records of English, Welsh and Irish medieval boroughs, referring to local rights and obligations.

The term ''scot'' comes from the Old English word ''sceat'', an ordinary coin in Anglo-Saxon times, equivalen ...

and Danegeld

Danegeld (; "Danish tax", literally "Dane yield" or tribute) was a tax raised to pay tribute or protection money to the Viking raiders to save a land from being ravaged. It was called the ''geld'' or ''gafol'' in eleventh-century sources. It ...

. Stephen was a strong supporter and promoter of the Savigniac community, whose mother house stood within his own county of Mortain

Mortain () is a former commune in the Manche department in Normandy in north-western France. On 1 January 2016, it was merged into the new commune of Mortain-Bocage.

Geography

Mortain is situated on a rocky hill rising above the gorge of the C ...

, which he lost to the Angevins during the Anarchy. One of the witnesses of Stephen's confirmation was Philip de Belmeis, an important Shropshire landholder. Together with his wife, Matilda, Philip subsequently made an important grant to the abbey of land at Ruckley in Tong Tong may refer to:

Chinese

*Tang Dynasty, a dynasty in Chinese history when transliterated from Cantonese

*Tong (organization), a type of social organization found in Chinese immigrant communities

*''tong'', pronunciation of several Chinese char ...

, with common pasture and pannage

Pannage (also referred to as ''Eichelmast'' or ''Eckerich'' in Germany, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Austria, Slovenia and Croatia) is the practice of releasing livestock-domestic pig, pigs in a forest, so that they can feed on falle ...

in his woods towards Brewood

Brewood is an ancient market town in the civil parish of Brewood and Coven, in the South Staffordshire district, in the county of Staffordshire, England. Located around , Brewood lies near the River Penk, eight miles north of Wolverhampton c ...

and the Lizard

The Lizard ( kw, An Lysardh) is a peninsula in southern Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. The most southerly point of the British mainland is near Lizard Point at SW 701115; Lizard village, also known as The Lizard, is the most southerl ...

.EytonAntiquities of Shropshire, volume 2, p. 203.

/ref> The grant is not dated but makes clear that the abbey was still part of the Savigniac community, as it committed all Savigniac houses to pray for Philip, Matilda and their family. The Savigniac houses were all absorbed into the Cistercian order in 1147, and the merger was confirmed by a

bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e., cows), bulls have long been an important symbol in many religions,

includin ...

of Eugenius III

Pope Eugene III ( la, Eugenius III; c. 1080 – 8 July 1153), born Bernardo Pignatelli, or possibly Paganelli, called Bernardo da Pisa, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1145 to his death in 1153. He w ...

on 11 April 1148. By this time Philip had transferred his support to the rival Augustinians

Augustinians are members of Christian religious orders that follow the Rule of Saint Augustine, written in about 400 AD by Augustine of Hippo. There are two distinct types of Augustinians in Catholic religious orders dating back to the 12th–13 ...

, granting lands which allowed the establishment of Lilleshall Abbey

Lilleshall Abbey was an Augustinian abbey in Shropshire, England, today located north of Telford. It was founded between 1145 and 1148 and followed the austere customs and observance of the Abbey of Arrouaise in northern France. It suffered f ...

.

Era of growth under Abbot Ranulf

Buildwas Abbey was initially quite small and poor, as its early endowments were not great in total, even if, as seems likely, it received its grant of Little Buildwas, across the river from the monastery, fromWilliam FitzAlan, Lord of Oswestry

William FitzAlan (1105–1160) was a nobleman of Breton ancestry. He was a major landowner, a Marcher lord with large holdings in Shropshire, where he was the Lord of Oswestry, as well as in Norfolk and Sussex. He took the side of Empress Mati ...

, in its early years: the original charter is lost and the grant is known from the second William FitzAlan's later confirmation.Dugdale''Monasticon Anglicanum'', volume 5, p. 359, no. 18.

/ref> Ingenulf, the first abbot, was fairly obscure, but the abbey entered a period of growth and development under Abbot Ranulf, who is known to have taken over by 1155, since a charter relating to Lilleshall which he witnessed cannot be later than that year. His abbacy coincided very closely with the reign of Henry II.

Financial and cultural advance

Richard I's confirmation of the abbey's lands, issued from the hand of hischancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

, William de Longchamp in 1189, two years after Ranulf's death, suggests that considerable progress had been made in acquiring land and other sources of income during his abbacy. In addition to the early endowments, it lists Bishop Richard Peche

Richard Peche (died 1182) was a medieval Bishop of Lichfield.

Peche was probably the son of Robert Peche who was Bishop of Lichfield from 1121 to 1128. He was definitely the son of a priest, as Ralph de Diceto wrote about him and justified the ...

's grants of a messuage

In law, conveyancing is the transfer of legal title of real property from one person to another, or the granting of an encumbrance such as a mortgage or a lien. A typical conveyancing transaction has two major phases: the exchange of contracts ...

in the Foregate at Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

and of a mill worth four shillings at Burne (possibly Burntwood

Burntwood is a former mining town and civil parish in the Lichfield District in Staffordshire, England, approximately west of Lichfield and north east of Brownhills. The town had a population of 26,049 and forms part of Lichfield distric ...

) near Lichfield; Brockton, Staffordshire, from Gerald of Brockton and his son; Richard of Pitchford's gift of the services of a man called Richard Crasset, who lived at Cosford, Shropshire

Cosford is a village in Shropshire, England. It is located on the A41 road, which is itself just south of junction 3 on the M54 motorway. The village is very small and is mostly made up of dwellings that house Royal Air Force personnel who work ...

; half of Hatton, south of Shifnal

Shifnal is a market town and civil parish in Shropshire, England, about east of Telford, 17 miles (27 km) east of the county town of Shrewsbury and 13 miles (20 km) west-northwest of the city of Wolverhampton. It is near the M54 mo ...

, from Adam of Hatton and Reginald, his son; half of Walton, Staffordshire from Walter Fitz Herman; land at Ivonbrook Grange, near Grangemill in Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

, from Henry Fitz Fulk; land at Cauldon in north-west Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

from William of Cauldon; and a house from Robert Fitz Thomas, although the location is partially erased.

The increasing wealth of the abbey was probably reflected in the enrichment of its library. Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

's database of the medieval libraries of Great Britain records 57 volumes that belonged at some time to the library at Buildwas, including two that subsequently found their way to St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle

St George's Chapel at Windsor Castle in England is a castle chapel built in the late-medieval Perpendicular Gothic style. It is both a Royal Peculiar (a church under the direct jurisdiction of the monarch) and the Chapel of the Order of the Gar ...

, although Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by Henry VIII, King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge ...

has by far the largest collection of former Buildwas books. Seventeen of the 57 are definitively dated to the 12th century and a further six possibly so. Two are internally dated to the time of Ranulf. One of these is a copy of works of Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

, with its attribution to Buildwas Abbey and the date 1167 written above the title in red and black letters. A glossed

A gloss is a brief notation, especially a marginal one or an interlinear one, of the meaning of a word or wording in a text. It may be in the language of the text or in the reader's language if that is different.

A collection of glosses is a '' ...

copy of the Book of Leviticus

The book of Leviticus (, from grc, Λευιτικόν, ; he, וַיִּקְרָא, , "And He called") is the third book of the Torah (the Pentateuch) and of the Old Testament, also known as the Third Book of Moses. Scholars generally agree ...

has the date 1179 on the 7th folio.

The additional income must also have played a major part in the decision to press ahead with construction of up-to-date stone buildings for the monastic community.

Construction of the abbey

There is no documentary evidence of the construction of the abbey at Buildwas, but it seems to have lagged a little behindKirkstall Abbey

Kirkstall Abbey is a ruined Cistercian monastery in Kirkstall, north-west of Leeds city centre in West Yorkshire, England. It is set in a public park on the north bank of the River Aire. It was founded ''c.'' 1152. It was disestablished during ...

, now in a Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by populati ...

suburb, which was built probably between 1152 and about 1170. Buildwas and Kirkstall are of the simplest and earliest pattern of Cistercian churches in Britain and are broadly comparable. In both cases, the builders became more adventurous as they progressed toward the west from the eastern end of the church. Both churches have a stone tower over the crossing, although this was forbidden by the General Chapter of the Cistercians in 1157. The presbytery at Buildwas was without aisles and the aisles of the nave had wooden ceilings, rather than the more elaborate vaulting found in later buildings. The piers of the aisles are also simple cylinders. While still definitely Romanesque, Buildwas has details in the design of capitals, bases and windows which prefigure the transition to Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture (or pointed architecture) is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It e ...

that came a little later. The church building and monks’ quarters were constructed in local sandstone and completed within the century: the infirmary

Infirmary may refer to:

*Historically, a hospital, especially a small hospital

*A first aid room in a school, prison, or other institution

*A dispensary (an office that dispenses medications)

*A clinic

A clinic (or outpatient clinic or ambu ...

and abbot's lodging were still under construction around 1220, or perhaps not yet started, when the abbey gained access to the stone quarries and timber of nearby Broseley

Broseley is a market town in Shropshire, England, with a population of 4,929 at the 2011 Census and an estimate of 5,022 in 2019. The River Severn flows to its north and east. The first The Iron Bridge, iron bridge in the world was built in 17 ...

.

Daughter houses

In 1154

In 1154 Pope Anastasius IV

Pope Anastasius IV ( – 3 December 1154), born Corrado Demetri della Suburra, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 July 1153 to his death in 1154. He is the most recent pope to take the name "Anastasius" upon his ...

, at the request of Abbot Richard of Savigny, listed the Savigniac houses, now following the rule of the Cistercian brothers but subject to the abbot of Savigny. Each house is named, along with any other houses subject to it. Bildwas ''cum pertinentiis suis'' (with its appurtenances) appears alone, without any dependent monasteries. However, in December 1156 Abbot Richard and his convent of Savigny, addressing Abbot Ranulf of Buildwas, declared: ''commitimus atque concedimus vobis et domui vestre curam et dispositionem domus nostre Sancte Marie Dubline imperpetuum habendam.'' ("We commit and submit to you and your house the care and disposition of our house of St Mary, Dublin, to be held in perpetuity.") In 1157, Basingwerk Abbey

Basingwerk Abbey ( cy, Abaty Dinas Basing) is a Grade I listed ruined abbey near Holywell, Flintshire, Wales. The abbey, which was founded in the 12th century, belonged to the Order of Cistercians. It maintained significant lands in the Englis ...

in Flintshire

, settlement_type = County

, image_skyline =

, image_alt =

, image_caption =

, image_flag =

, image_shield = Arms of Flint ...

was handed over to Ranulf and Buildwas Abbey on the same terms as the Irish house. Both Basingwerk and St. Mary's Abbey, Dublin, had formerly belonged to Combermere Abbey

Combermere Abbey is a former monastery, later a country house, near Burleydam, between Nantwich, Cheshire and Whitchurch in Shropshire, England, located within Cheshire and near the border with Shropshire. Initially Savigniac and later Cisterci ...

in Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county t ...

. An attempt in 1177 to reverse this change of dependence failed and prompted Savigny to send a collection of pertinent documents and a covering note to the abbot of Cîteaux, the head of the Cistercian order.

Bishop Richard Peche probably granted the house at Chester Foregate to Buildwas so that Abbot Ranulf could more easily discharge his responsibilities in Ireland. In 1183–4 Gilbert Pipard, the guardian of Chester, filed a claim for expenses of four shillings for arranging the passage of the abbot of Buildwas to Ireland, making clear that Ranulf did sail to Dublin from Chester, easily reached via

Bishop Richard Peche probably granted the house at Chester Foregate to Buildwas so that Abbot Ranulf could more easily discharge his responsibilities in Ireland. In 1183–4 Gilbert Pipard, the guardian of Chester, filed a claim for expenses of four shillings for arranging the passage of the abbot of Buildwas to Ireland, making clear that Ranulf did sail to Dublin from Chester, easily reached via Watling Street

Watling Street is a historic route in England that crosses the River Thames at London and which was used in Classical Antiquity, Late Antiquity, and throughout the Middle Ages. It was used by the ancient Britons and paved as one of the main R ...

, which ran just north of the abbey. Pipard's claim was made on the basis that Ranulf was travelling in the king's service, and he seems to have been at least as much involved in Henry II's intervention in Ireland as in the affairs of the daughter house in Dublin. Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales ( la, Giraldus Cambrensis; cy, Gerallt Gymro; french: Gerald de Barri; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and English historians in the Middle Ages, historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and w ...

, in his account of the Synod of Cashel

The Synod of Cashel of 1172, also known as the Second Synod of Cashel,The first being the Synod held at Cashel in 1101 was assembled at Cashel at the request of Henry II of England shortly after his arrival in Ireland in October 1171. The Syno ...

of 1172, portrays Ranulf as being central to the king's conquest of Ireland, helping to enact and dramatise his power by imposing his norms on the Irish church. The leading bishops of Ireland, he reports, attended the synod,

After Ranulf's assistance in Ireland, Henry II confirmed the transfer of St Mary's Abbey in Dublin to Buildwas in 1174, listing its numerous endowments that had been granted to it before Richard de Strigoil came to Ireland. Richard de Striguil

Striguil or Strigoil is the name that was used from the 11th century until the late 14th century for the port and Norman castle of Chepstow, on the Welsh side of the River Wye which forms the boundary with England. The name was also applied to t ...

, otherwise Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke

Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (of the first creation), Lord of Leinster, Justiciar of Ireland (113020 April 1176), also known as Richard FitzGilbert, was an Anglo-Norman nobleman notable for his leading role in the Anglo-Norman invasion ...

, and later called Strongbow, was a potential threat to royal power, a Norman baron already powerful and well established in Ireland. His uncle, Harvey de Montmorency, was involved in negotiations with Ranulf to grant lands for the founding of a new Cistercian abbey at Dunbrody, which would be a daughter house of Buildwas Abbey and colonised by it. Ranulf sent a lay brother

Lay brother is a largely extinct term referring to religious brothers, particularly in the Catholic Church, who focused upon manual service and secular matters, and were distinguished from choir monks or friars in that they did not pray in choir, ...

from Buildwas to survey the site, but the report was unfavourable. Ranulf ultimately decided to back out of the project, finally conceding to St Mary's, Dublin, the rights to the patronage and visitation of Dunbrody on 1 November 1182.Dugdale''Monasticon Anglicanum'', volume 5, p. 362.

/ref> Ranulf seems to have travelled a great deal, and the chronicler of

Waverley Abbey

Waverley Abbey was the first Cistercian abbey in England, founded in 1128 by William Giffard, the Bishop of Winchester.

Located about southeast of Farnham, Surrey, it is situated on a flood-plain; surrounded by current and previous channels o ...

tells us that in 1187 ''obiit Rannulfus abbas de Bildewas in itinere capituli'' ("Ranulf, abbot of Buildwas, died on his way to the chapter"), i.e. the general meeting of the Cistercian order at the mother house in Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

.

Wealth and endowments

Buildwas Abbey shared in the increasing prosperity of the 13th century and built up a large portfolio of estates that gave it a sound economic base, at least under normal conditions.Angold et alHouse of Cistercian monks: Abbey of Buildwas, note anchor 24.

/ref> As a result, it became part of a group of large Shropshire monasteries whose estates bore comparison with the great aristocratic families in the county.Cox et al. D. C

Domesday Book: 1300-1540, note anchor 61

/ref> There were peak periods of acquisition in the 1240s and 1280s, as can be seen in the table below. The map based on the table demonstrates how Buildwas built up a concentrated belt of granges along the Rivers Severn and Worfe and the Shropshire-Staffordshire border, all quickly accessible from the abbey by routes that took full advantage of the River Severn itself. This was not an accident but a consequence of observing the Cistercian precept that granges should be within a

day's journey

A day's journey in pre-modern literature, including the Bible, ancient geographers and ethnographers such as Herodotus, is a measurement of distance.

In the Bible, it is not as precisely defined as other Biblical measurements of distance; the dis ...

of the abbey, a strategy for keeping the community relatively enclosed. However, the abbey also had fewer but larger estates, with extensive grazing, lands further away near the Welsh border

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peopl ...

and in distant Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

.

Strategies of expansion

Potentially the most valuable acquisition close to the abbey was the grant by Gilbert de Lacy, lord ofCressage

Cressage is a village and civil parish in Shropshire, England. It lies on the junction of the A458 and B4380 roads and the River Severn flows around its northern boundary. The Royal Mail postcode begins SY5. The parish council is combined w ...

, probably in 1232,EytonAntiquities of Shropshire, volume 6, p. 75.

/ref> of the

vill

Vill is a term used in English history to describe the basic rural land unit, roughly comparable to that of a parish, manor, village or tithing.

Medieval developments

The vill was the smallest territorial and administrative unit—a geographical ...

of Harnage

Harnage is a small village in the English county of Shropshire. It is located just SE of the village of Cound, in whose civil parish it lies, and the nearest notable settlement is Cressage.

Harnage is considered a hamlet, not a village, as it ...

, near Cound

Cound is a village and civil parish on the west bank of the River Severn in the English county of Shropshire, about south east of the county town Shrewsbury. Once a busy and industrious river port Cound has now reverted to a quiet rural comm ...

, Shropshire. Despite initial difficulties, a combination of persistent legal defence and shrewd bargaining allowed the abbey to establish and consolidate its position in the area. The boundaries of the grant were meticulously detailed. As well as the land, the abbey was assigned rights of pasture for 50 cattle and for pigs, and right of road for the abbey's vehicles so that their employees could wash sheep and load barges in the River Severn

, name_etymology =

, image = SevernFromCastleCB.JPG

, image_size = 288

, image_caption = The river seen from Shrewsbury Castle

, map = RiverSevernMap.jpg

, map_size = 288

, map_c ...

.Dugdale''Monasticon Anglicanum'', volume 5, pp. 356-7, no. 2.

/ref> However, it seems Gilbert was in debt and in no position to make the grant. He had used the land as security for a loan from Ursell, son of Hamo of

Hereford

Hereford () is a cathedral city, civil parish and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, south-west of Worcester and north-west of Gloucester. With a population ...

. It is unclear whether the abbey was expected to enter into a mortgage or purchase or whether Gilbert hoped to evade repaying Ursellus, who was Jewish. In 1234, shortly after Gilbert's death, the abbot secured from Henry III a complete cancellation of the pledge, although not presumably of the debt itself, and the Justiciar

Justiciar is the English form of the medieval Latin term ''justiciarius'' or ''justitiarius'' ("man of justice", i.e. judge). During the Middle Ages in England, the Chief Justiciar (later known simply as the Justiciar) was roughly equivalent ...

s of the Exchequer of the Jews

The Exchequer of the Jews (Latin: ''Scaccarium Judaeorum'') was a division of the Exchequer of Pleas, Court of Exchequer at Westminster, which recorded and regulated the taxes and the law-cases of the History of the Jews in England, Jews in England ...

were notified of the change. By this time, however, the abbey was already involved in a complex suit with Gilbert's widow, Eva, who was claiming part of his estate as her dower

Dower is a provision accorded traditionally by a husband or his family, to a wife for her support should she become widowed. It was settled on the bride (being gifted into trust) by agreement at the time of the wedding, or as provided by law.

...

. The abbey's position was guaranteed by a charter of the dead man's son, also called Gilbert, who swore to answer his mother's claim in court, should the need arise. However, the matter was settled by accord during 1236. By 1249 the younger Gilbert was dead and his son Adam in the wardship

In law, a ward is a minor or incapacitated adult placed under the protection of a legal guardian or government entity, such as a court. Such a person may be referenced as a "ward of the court".

Overview

The wardship jurisdiction is an ancient jur ...

of Matilda de Lacy. The debts were still large and the king ordered that they should not be paid until after Adam came of age. With the pressure of a dower

Dower is a provision accorded traditionally by a husband or his family, to a wife for her support should she become widowed. It was settled on the bride (being gifted into trust) by agreement at the time of the wedding, or as provided by law.

...

to be found for Agnes, Gilbert's widow and Adam's mother, the estate was still in trouble and in 1253 the abbot of Buildwas took the opportunity to purchase a 19-year lease of part of Cressage for 200 marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks, trademarks owned by an organisation for the benefit of its members

* Marks & Co, the inspiration for the novel ...

.EytonAntiquities of Shropshire, volume 6, p. 312.

/ref> In 1255 the Hundred Roll records the abbey as holding one hide at Harnage. By 1291 the abbey held the whole of Harnage, assessed at four

carucate

The carucate or carrucate ( lat-med, carrūcāta or ) was a medieval unit of land area approximating the land a plough team of eight oxen could till in a single annual season. It was known by different regional names and fell under different forms ...

s.

The same strategy was followed elsewhere: assiduous acquisition of lands and strengthening of authority and control in centres where the abbey already had lands, coupled with new inroads into centres close to existing granges. At Leighton, for example, the abbey began before 1263 with a mill and fishpond on the brook at Merehay. Next came the church, where in 1282 it first acquired the advowson

Advowson () or patronage is the right in English law of a patron (avowee) to present to the diocesan bishop (or in some cases the ordinary if not the same person) a nominee for appointment to a vacant ecclesiastical benefice or church living, ...

or patronage, i.e. the right to nominate the parish priest, and then appropriated the church, thus acquiring the tithes

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more r ...

. Very soon, the lord of the manor

Lord of the Manor is a title that, in Anglo-Saxon England, referred to the landholder of a rural estate. The lord enjoyed manorial rights (the rights to establish and occupy a residence, known as the manor house and demesne) as well as seig ...

added land, including meadow. Sometimes Buildwas clashed with other important monasteries in the vicinity. Along the River Tern

The Indian river tern or just river tern (''Sterna aurantia'') is a tern in the family Laridae. It is a resident breeder along inland rivers from Iran east into the Indian Subcontinent and further to Myanmar to Thailand, where it is uncommon. ...

, Buildwas feuded with Lilleshall Abbey, which had numerous holdings. In 1251, for example, the abbot of Buildwas took out two writ

In common law, a writ (Anglo-Saxon ''gewrit'', Latin ''breve'') is a formal written order issued by a body with administrative or judicial jurisdiction; in modern usage, this body is generally a court. Warrants, prerogative writs, subpoenas, a ...

s, accusing his rivals of destroying his pool at Tern by tearing down the dam and of damaging his interests by unlawfully building a pool at Longdon. The Cistercian Croxden Abbey

Croxden Abbey, also known as "Abbey of the Vale of St. Mary at Croxden", was a Cistercian abbey at Croxden, Staffordshire, United Kingdom. A daughter house of the abbey in Aunay-sur-Odon, Normandy, the abbey was founded by Bertram III de Verdun ...

was much more accommodating. In 1287 it exchanged its grange at Adeney

Adeney is a hamlet in the English county of Shropshire, in the civil parish of Edgmond

Edgmond is a village in the borough of Telford and Wrekin and ceremonial county of Shropshire, England. The village population at the 2011 Census was 2 ...

in Shropshire for Buildwas' Caldon Grange, an advantageous exchange for both abbeys, eliminating outlying granges to make administration easier. In line with a Cistercian prohibition, Buildwas did not set out to acquire either the advowsons or tithes of many churches: in 1535, shortly before dissolution, tithes were bringing in only £6 annually: £4 from Leighton and £2 from HattonDugdale''Monasticon Anglicanum'', volume 5, p. 360, no. 24.

/ref>

In 1292, under

In 1292, under Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal o ...

, close to the end of the major period of expansion, many individual grants to the abbey were confirmed by Inspeximus. Also under Edward I, the abbey's major privilege of immunity from secular dues and demands, was reiterated both by charter renewal and in quo warranto

In law, especially English and American common law, ''quo warranto'' (Medieval Latin for "by what warrant?") is a prerogative writ requiring the person to whom it is directed to show what authority they have for exercising some right, power, or ...

proceedings. However, this did not protect the abbey against some forms of royal begging letter, as when Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

requested a subsidy for the marriage of his sister, Eleanor of Woodstock

Eleanor of Woodstock (18 June 1318 – 22 April 1355) was an English princess and the duchess of Guelders by marriage to Reginald II of Guelders. She was regent as the guardian of their minor son Reginald III from 1343 until 1344. She was ...

, to Reginald II, Count of Guelders in 1332.

Bridges and tolls

Some sources, including the Historic England listing page, claim that a significant part of the abbey's income came from bridge tolls An earlier Pastscape entry even implies that the community was small and that tolls levied on "passing travellers" its only source of income. The origin of this idea seems to be the earlier Department of the Environment (DoE) guide to the site, which proffers the very questionable information that "the properties of the abbey were never large" and couples it with the true but irrelevant statement that Buildwas was "classed among the smaller abbeys" at the dissolution. TheVictoria County History

The Victoria History of the Counties of England, commonly known as the Victoria County History or the VCH, is an English history project which began in 1899 with the aim of creating an encyclopaedic history of each of the historic counties of En ...

volume on agriculture in Shropshire undercuts the premise by listing Buildwas Abbey among the great landowners of the county: its relative decline came in the late medieval period. The VCH article on Buildwas in the volume on religious houses, a detailed and fully referenced account, lists the main sources of income but makes no mention of tolls. It argues that the income of the abbey came mainly from stock rearing and points out that it was a major participant in the medieval wool trade, known as a source of raw wool at least as far afield as Italy.

The letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, titl ...

of Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

do provide evidence that the abbots were occasionally authorised to levy tolls, but not as a regular source of income. On 17 March 1318 the king granted the abbey the right to levy a toll on goods passing over the bridge as pontage

Pontage was a term for a toll levied for the building or repair of bridges dating to the medieval era in England, Wales and Ireland.

Pontage was similar in nature to murage (a toll for the building of town walls) and pavage (a toll for pavin ...

– a charge intended to finance the repair and maintenance of the bridge. This was to be for just three years, which suggests that no such charge was made ordinarily. It was specifically a levy on goods for sale, not on passing travellers or even on local people moving their own crops across the river. It was not to generate an income stream for the abbey itself but a way of contracting it to carry out public works, or rather works for the king. On 10 August that year the king appointed a commission of oyer and terminer

In English law, oyer and terminer (; a partial translation of the Anglo-French ''oyer et terminer'', which literally means "to hear and to determine") was one of the commissions by which a judge of assize sat. Apart from its Law French name, the ...

to investigate an allegation that John, the abbot of Buildwas, and two of his monks, had carried away goods belonging to John Ludlow of Shrewsbury at Great Buildwas: possibly a dispute over the temporary tolls. In April 1325 Buildwas Abbey obtained a second grant of pontage for three years from Edward II. This time it did not relate to the Severn crossing but was to construct a bridge over "the water of Cospeford" – presumably the Humphreston Stream, a tributary of the River Worfe

The River Worfe is a river in Shropshire, England. The name Worfe is said to derive from the Old English meaning to wander (or meander) which the river is notable for in its middle section. Mapping indicates that the river begins at Cosford Brid ...

that now feeds Cosford Pool. This would have benefited the abbey by linking the estates at Ryton and Cosford to Donington and Ruckley more conveniently, as well as being useful to local traffic more generally. A further grant of pontage under Edward III in 1354, to repair the Severn bridge at Buildwas, does not specify means of raising the money.

The Severn crossing at Buildwas was important to Buildwas Abbey itself, a vital link between landed estates on either side of the river. It must also have been important to nearby Wenlock Priory

Wenlock Priory, or St Milburga's Priory, is a ruined 12th-century monastery, located in Much Wenlock, Shropshire, at . Roger de Montgomery re-founded the Priory as a Cluniac house between 1079 and 1082, on the site of an earlier 7th-century mon ...

: a litigious and sometimes violent community, but there is no record of disputes between it and Buildwas over tolls. Some time before the dissolution Buildwas established a guest house for travellers by the bridge on its demesne: the family running it in 1536 was surnamed Whitefolks, probably a reference to the white monastic garb of their employers. The most important Severn crossing in the area was at Atcham

Atcham is a village, ecclesiastical parish and civil parish in Shropshire, England. It lies on the B4380 (once the A5), 5 miles south-east of Shrewsbury. The River Severn flows round the village. To the south is the village of Cross Houses and ...

, and belonged not to Buildwas but to Lilleshall Abbey, which constructed a toll bridge in the early 13th century to carry Watling Street

Watling Street is a historic route in England that crosses the River Thames at London and which was used in Classical Antiquity, Late Antiquity, and throughout the Middle Ages. It was used by the ancient Britons and paved as one of the main R ...

traffic over the river, replacing the earlier ferry. Lilleshall was allowed to levy a toll of 1 penny per cartload on goods traffic.

List of endowments

Generating income

Much of the land acquired by Buildwas Abbey was used for stock rearing. TheTaxatio Ecclesiastica

The ''Taxatio Ecclesiastica'', often referred to as the ''Taxatio Nicholai'' or just the ''Taxatio'', compiled in 1291–92 under the order of Pope Nicholas IV, is a detailed database valuation for ecclesiastical taxation of English, Welsh, an ...

of 1291 showed about 60% of the temporalities

Temporalities or temporal goods are the secular properties and possessions of the church. The term is most often used to describe those properties (a ''Stift'' in German or ''sticht'' in Dutch) that were used to support a bishop or other religious ...

in Shropshire and Staffordshire coming from stock and about 20% from the arable land

Arable land (from the la, arabilis, "able to be ploughed") is any land capable of being ploughed and used to grow crops.''Oxford English Dictionary'', "arable, ''adj''. and ''n.''" Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013. Alternatively, for the ...

of the abbey's demesne

A demesne ( ) or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. The concept or ...

. Excluded from this are the Derbyshire lands, which included grazing for a large flock of 400 sheep, rented to the abbey by Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal o ...

's brother, Edmund Crouchback

Edmund, Earl of Lancaster and Earl of Leicester (16 January 12455 June 1296) nicknamed Edmund Crouchback was a member of the House of Plantagenet. He was the second surviving son of King Henry III of England and Eleanor of Provence. In his ch ...

for just 6s. 8d. Sheep seem to have been the main concern also in the Shropshire lands, with the rights acquired at Cressage allowing the abbey to wash sheep in the Severn and then ship them down river. The abbey was certainly involved in the European wool trade to an important extent and this was typical of Cistercian houses, which were at the forefront in supplying the growing Flemish markets. In 1265 the abbot of Buildwas was one of a number of monastic heads to whom Henry III wrote to regulate their business with wool merchants from the County of Flanders

The County of Flanders was a historic territory in the Low Countries.

From 862 onwards, the counts of Flanders were among the original twelve peers of the Kingdom of France. For centuries, their estates around the cities of Ghent, Bruges and Ypr ...

. In the first half of the 14th century Francesco Balducci Pegolotti Pegolotti Pratica Ricc.2441 specimen half page.

Francesco Balducci Pegolotti (fl. 1290 – 1347), also Francesco di Balduccio, was a Florentine merchant and politician.

Life

His father, Balduccio Pegolotti, represented Florence in commercial neg ...

stated the wool output of Buildwas ("Bihguassi") in his famous guide for Italian merchants, known as '' Pratica della mercatura'' as 20 sacks annually.Cuningham, WGrowth of English Industry and Commerce, p. 632.

/ref> He valued its wool at 20 marks a sack for the best, 12 marks for medium, and 10 marks for broken wool. Although the 13th and early 14th centuries were the great age of demesne farming, Buildwas always acquired some income from rents and

lease

A lease is a contractual arrangement calling for the user (referred to as the ''lessee'') to pay the owner (referred to as the ''lessor'') for the use of an asset. Property, buildings and vehicles are common assets that are leased. Industrial ...

s, generally inherited from the donors, as Cistercians were initially prohibited from renting to secular tenants. However, its income from churches was exceptionally low, less than 5% of net income in 1535, compared with over 80% at the Augustinian Chirbury Priory

Chirbury () is a village in west Shropshire, England. It is situated in the Vale of Montgomery, close to the Wales–England border ( at its nearest), which is to its north, west and south. The A490 and B4386 routes cross at Chirbury.

It is th ...

, for example.

Abbots and Monks

Origins

All the known names of monks show English origins. Surnames like Boningale, Ashbourne and Bridgnorth suggest most were from Shropshire or the vicinity of the abbey's granges. Some were from landed gentry families: Abbot Henry Burnell, for example, who ruled the abbey around 1300, was brother of Philip Burnell, lord of Benthall. He gave his younger brother Hamo a paid post at the abbey and Hamo sold it back to a later abbot, John, illustrating the dangers of nepotism where local landed interests prevailed.Spiritual and intellectual life

WhenEdward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

proposed drafting in the abbot of Buildwas to reassert authority over the Welsh Cistercian abbey of Strata Marcella

The Abbey of Strata Marcella ( cy, Abaty Ystrad Marchell) was a medieval Cistercian monastery situated at Ystrad Marchell (''Strata Marcella'' being the Latinised form of the Welsh name) on the west bank of the River Severn near Welshpool, Powys ...

in 1328, he commented that at Buildwas "wholesome observance and regular institution flourishes." However, this was influenced by the king's own political interests in the Welsh Marches, and it is clear that he was determined to use the abbot of Buildwas as his agent. A later letter admits that the real problem at Strata Marcella was political: "unlawful assemblies to excite contentions and hatred between the English and the Welsh," so the king had reason to trumpet the effectiveness of the English abbot he hoped to use against a Welsh monastery.

Evaluation of the monastic life at Buildwas was the responsibility of the Cistercian order itself, as Cistercian monasteries were beyond the canonical visitation

In the Catholic Church, a canonical visitation is the act of an ecclesiastical superior who in the discharge of his office visits persons or places with a view to maintaining faith and discipline and of correcting abuses. A person delegated to car ...

s of the local bishop. Only one visitation on behalf of the mother house of Savigny has left a written record. In 1231 Stephen of Lexington

Stephen of Lexington (or "de Lexington", "Lexinton", "Lessington") (born c. 1198, d. 21 March, probably in 1258), was an English Cistercian monk, abbot, and founder of a college in Paris.

Life

Stephen came from a prominent family of royal official ...

issued statutes after a visitation, but those received by Buildwas were identical to those for Byland, Combermere, and Quarr, suggesting that there were no special grounds for censure: routine concerns about excessive conversation and dietary luxury, with instructions for improving the discipline of novice

A novice is a person who has entered a religious order and is under probation, before taking vows. A ''novice'' can also refer to a person (or animal e.g. racehorse) who is entering a profession

A profession is a field of work that has ...

monks and lay brother

Lay brother is a largely extinct term referring to religious brothers, particularly in the Catholic Church, who focused upon manual service and secular matters, and were distinguished from choir monks or friars in that they did not pray in choir, ...

s.

Monks generally pursued their education and spiritual development as far as the priesthood. There were plenty of opportunities to preside over the

Monks generally pursued their education and spiritual development as far as the priesthood. There were plenty of opportunities to preside over the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

at Buildwas, as there were at least eight altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in paga ...

s Whenever the life of the abbey was disrupted, the main concern of kings and other interested parties was the interruption to chantry

A chantry is an ecclesiastical term that may have either of two related meanings:

# a chantry service, a Christian liturgy of prayers for the dead, which historically was an obiit, or

# a chantry chapel, a building on private land, or an area in ...

masses: celebrations of the Eucharist for the souls of the dead. These depended on the Catholic theology of the Sacrifice of the Mass