British European Airways Flight 548 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

British European Airways Flight 548 was a scheduled passenger flight from London Heathrow to

Tensions came to a head shortly before the accident. Three days earlier on 15 June, a captain complained that his inexperienced co-pilot "would be useless in an emergency". Upset, the co-pilot committed a serious error on departure from Heathrow, setting the flaps fully down instead of up. AIB Report 4/73, pp. 23–24. Stewart 2001, p. 92. The mistake was noted and remedied by the SFO, who related the event to colleagues as an example of avoidable danger. This became known among BEA pilots as the "Dublin Incident".

An hour and a half before the departure of BE 548, its rostered captain, Stanley Key, a former

Tensions came to a head shortly before the accident. Three days earlier on 15 June, a captain complained that his inexperienced co-pilot "would be useless in an emergency". Upset, the co-pilot committed a serious error on departure from Heathrow, setting the flaps fully down instead of up. AIB Report 4/73, pp. 23–24. Stewart 2001, p. 92. The mistake was noted and remedied by the SFO, who related the event to colleagues as an example of avoidable danger. This became known among BEA pilots as the "Dublin Incident".

An hour and a half before the departure of BE 548, its rostered captain, Stanley Key, a former

While technically advanced, the Trident (and other aircraft with a

While technically advanced, the Trident (and other aircraft with a

In a further near-accident, a Trident 2E, ''G-AVFH'', climbing away from London Heathrow for Naples in May 1970 experienced what was claimed by its flight crew to have been a spontaneous uncommanded retraction of the leading-edge slats which was initially unnoticed by any of them. The aircraft's automatic systems sensed the loss of airspeed and lift and issued two stall warnings. Since the crew did not initially detect anything amiss, they disabled the automatic system. While doing so, the first officer noticed and immediately remedied the problem by re-extending the retracted slats, and the flight continued normally. Stewart 2001, p. 99.

Investigations into the event found no mechanical malfunction that could have caused the premature leading-edge device retraction, and stated that the aircraft had "just about managed to stay flying". A possible design fault in the high-lift control interlocks came under suspicion, although this was discounted during the investigation into the crash of ''Papa India''. AIB Report 4/73, pp. 17–18. The event became known as the "Naples Incident" or the "Foxtrot Hotel Incident" ( after the registration of the aircraft concerned) at BEA and was examined during the accident inquiry. AIB Report 4/73, p. 17. The forward fuselage of this aircraft is preserved and on public display at the de Havilland Aircraft Heritage Centre, London Colney. Ellis 2004, p. 80.

In a further near-accident, a Trident 2E, ''G-AVFH'', climbing away from London Heathrow for Naples in May 1970 experienced what was claimed by its flight crew to have been a spontaneous uncommanded retraction of the leading-edge slats which was initially unnoticed by any of them. The aircraft's automatic systems sensed the loss of airspeed and lift and issued two stall warnings. Since the crew did not initially detect anything amiss, they disabled the automatic system. While doing so, the first officer noticed and immediately remedied the problem by re-extending the retracted slats, and the flight continued normally. Stewart 2001, p. 99.

Investigations into the event found no mechanical malfunction that could have caused the premature leading-edge device retraction, and stated that the aircraft had "just about managed to stay flying". A possible design fault in the high-lift control interlocks came under suspicion, although this was discounted during the investigation into the crash of ''Papa India''. AIB Report 4/73, pp. 17–18. The event became known as the "Naples Incident" or the "Foxtrot Hotel Incident" ( after the registration of the aircraft concerned) at BEA and was examined during the accident inquiry. AIB Report 4/73, p. 17. The forward fuselage of this aircraft is preserved and on public display at the de Havilland Aircraft Heritage Centre, London Colney. Ellis 2004, p. 80.

Among the passengers were 29 Americans, 29 Belgians, 28 Britons, 12 Irish, four South Africans and three Canadians. There was also one passenger from each of French West Africa, India, Jamaica, Latin America, Nigeria and Thailand. The passengers included between 25 and 30 women and several children.

Among the passengers were 29 Americans, 29 Belgians, 28 Britons, 12 Irish, four South Africans and three Canadians. There was also one passenger from each of French West Africa, India, Jamaica, Latin America, Nigeria and Thailand. The passengers included between 25 and 30 women and several children.

The flight crew boarded BE 548 (

The flight crew boarded BE 548 ( The doors closed at 15:58 and at 16:00 Key requested

The doors closed at 15:58 and at 16:00 Key requested

World News – Trident accident

''FLIGHT International'', pp. 888–890. Retrieved 30 December 2009. At 16:08:30 BE 548 began its take-off run, which lasted 44 seconds, the aircraft leaving the ground at an indicated airspeed (IAS) of . The safe climb speed ( V2) of was reached quickly, and the undercarriage was retracted. After 19 seconds in the air the

All 118 persons aboard the aircraft were killed: 112 passengers and six crew members. Among the passengers were 12 senior businessmen from

All 118 persons aboard the aircraft were killed: 112 passengers and six crew members. Among the passengers were 12 senior businessmen from

Civil Aircraft Accident Report 4/73: ''Trident I G-ARPI: Report of the Public Inquiry into the Causes and Circumstances of the Accident near Staines on 18 June 1972''.

Accident Investigation Branch, Department of Trade and Industry. HMSO, London, 1973.

Civil Aircraft Accident Report 4/73: ''Trident I G-ARPI: Report of the Public Inquiry into the Causes and Circumstances of the Accident near Staines on 18 June 1972 – Appendix A''

Accident Investigation Branch, Department of Trade and Industry. HMSO, London, 1973. *Ellis, Ken. ''Wrecks and Relics – 19th Edition'', Hinckley, Leicestershire. Midland Publishing, 2004. *Faith, Nicholas. ''Black Box''. London, Macmillan Publishers Ltd. 1997. *Gero, David. ''Aviation Disasters''. Yeovil, Somerset. Patrick Stephens Ltd (Haynes Publishing). 1997 *Job, Macarthur. ''Air Disaster Volume 1''. Weston Creek, ACT, Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd. 1994 *Roach, John and Eastwood, Tony. ''Jet Airliner Production List'', West Drayton, England, The Aviation Hobby Shop, 1992. *Stewart, Stanley. ''Air Disasters'' London, Ian Allan Publishing, 2001.

Image of ''Papa India'' prior to the accident

* ttp://www.felthorpe.net/History.html Images of the crash site of ''G-ARPY'' (the 'Felthorpe accident')br> Captain Stanley Key

pictured (bottom right) at a BALPA party on 7 December 1955 talking to John Profumo, in a 1955 ''Flight'' news item

"Inquiry Briefing"

a 1972 ''Flight'' article

a 1972 ''Flight'' article

a 1972 ''Flight'' article {{Use dmy dates, date=October 2022 Aviation accidents and incidents in 1972 1972 disasters in the United Kingdom 1972 in England Disasters in Surrey Aviation accidents and incidents in England Accidents and incidents involving the Hawker Siddeley Trident Flight 548 Transport in Surrey Staines-upon-Thames June 1972 events in Europe Airliner accidents and incidents in the United Kingdom Airliner accidents and incidents caused by pilot error Airliner accidents and incidents caused by stalls

Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

that crashed near Staines, Surrey, England, soon after take-off on 18 June 1972, killing all 118 people on board. The accident became known as the Staines air disaster. , it remains the deadliest air accident (as opposed to terrorist incidents) in the United Kingdom and was the deadliest air accident involving a Hawker Siddeley Trident

The Hawker Siddeley HS-121 Trident (originally the de Havilland DH.121 and briefly the Airco DH.121) is a British airliner produced by Hawker Siddeley.

In 1957, de Havilland proposed its DH.121 trijet design to a British European Airways (BEA ...

. Two passengers initially survived the impact but died soon after from their injuries.

The aircraft suffered a deep stall in the third minute of its flight and crashed to the ground, narrowly missing a busy main road. The public inquiry principally blamed the captain for failing to maintain airspeed and configure the high-lift device

In aircraft design and aerospace engineering, a high-lift device is a component or mechanism on an aircraft's wing that increases the amount of lift produced by the wing. The device may be a fixed component, or a movable mechanism which is deplo ...

s correctly. It also cited the captain's heart condition and the limited experience of the co-pilot, while noting an unspecified "technical problem" that the crew apparently resolved before take-off.

The crash took place against the background of a pilots' strike that had caused bad feelings between crew members. The strike had also disrupted services, causing Flight 548 to be loaded with the maximum weight allowable. Recommendations from the inquiry led to the mandatory installation of cockpit voice recorder

A flight recorder is an electronic recording device placed in an aircraft for the purpose of facilitating the investigation of aviation accidents and incidents. The device may often be referred to as a "black box", an outdated name which has ...

s in British-registered airliners. Another recommendation was for greater caution before allowing off-duty crew members to occupy flight deck seats. Some observers felt that the inquiry was unduly biased in favour of the aircraft's manufacturers.

Industrial relations background

The International Federation of Air Line Pilots' Associations (IFALPA) had declared Monday 19 June 1972 (the day after the accident) as a worldwide protest strike againstaircraft hijacking

Aircraft hijacking (also known as airplane hijacking, skyjacking, plane hijacking, plane jacking, air robbery, air piracy, or aircraft piracy, with the last term used within the special aircraft jurisdiction of the United States) is the unlawfu ...

which had become commonplace in the early 1970s. Support was expected, but the British Air Line Pilots Association

The British Airline Pilots’ Association (BALPA) is the professional association and registered trade union for UK pilots. BALPA represents the views and interests of pilots, campaigning on contractual, legal and health issues affecting its ...

(BALPA) organised a postal ballot

An absentee ballot is a vote cast by someone who is unable or unwilling to attend the official polling station to which the voter is normally allocated. Methods include voting at a different location, postal voting, proxy voting and online v ...

to ask members at BEA whether they wanted to strike. Stewart 2001, p. 91. Because of the impending strike, travellers had amended their plans to avoid disruption, and as a result flight BE 548 was full, despite Sunday being traditionally a day of light travel. Bartelski 2001, p. 184.

BALPA was also in an industrial dispute with BEA over pay and conditions. The dispute was controversial, those in favour being mainly younger pilots, and those against mostly older. A group of 22 BEA Trident co-pilots known as supervisory first officers (SFOs) were already on strike, citing their low status and high workload. To help train newly qualified co-pilots, SFOs were told to occupy only the third flight-deck seat of the Trident as a "P3", operating the aircraft's systems and helping the captain (known as "P1" on the BEA Trident fleet) and the co-pilot ("P2") who handled the aircraft. In other airlines and aircraft, the job of SFO/P3 was usually performed by flight engineer

A flight engineer (FE), also sometimes called an air engineer, is the member of an aircraft's flight crew who monitors and operates its complex aircraft systems. In the early era of aviation, the position was sometimes referred to as the "air m ...

s. As a result of being limited to the P3 role, BEA Trident SFOs/P3s were denied experience of aircraft handling, which led to loss of pay, which they resented. In addition, their status led to a regular anomaly: experienced SFO/P3s could only assist while less-experienced co-pilots actually flew the aircraft.

Captain Key's outburst

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

pilot who had served during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, was involved in a quarrel in the crew room at Heathrow's Queen's Building with a first officer named Flavell. The subject was the threatened strike, which Flavell supported and Key opposed. Both of Key's flight deck crew on BE 548 witnessed the altercation, and another bystander described Key's outburst as "the most violent argument he had ever heard". Stewart 2001, p. 93. Shortly afterward Key apologised to Flavell, and the matter seemed closed. AIB Report 4/73, p. 22. Key's anti-strike views had won enemies, and graffiti

Graffiti (plural; singular ''graffiti'' or ''graffito'', the latter rarely used except in archeology) is art that is written, painted or drawn on a wall or other surface, usually without permission and within public view. Graffiti ranges from s ...

against him had appeared on the flight decks of BEA Tridents, including the incident aircraft, G-ARPI (''Papa India''). The graffiti on ''Papa India's'' flight engineers' desk was analysed by a handwriting expert to identify who had written it, but this could not be determined. The public inquiry found that none of the graffiti had been written by crew members on BE 548 on the day of the accident. AIB Report 4/73, pp. 21–22. AIB Report 4/73, p. 21.

Operational background

The aircraft operating Flight BE 548 was aHawker Siddeley Trident

The Hawker Siddeley HS-121 Trident (originally the de Havilland DH.121 and briefly the Airco DH.121) is a British airliner produced by Hawker Siddeley.

In 1957, de Havilland proposed its DH.121 trijet design to a British European Airways (BEA ...

Series 1 short- to medium-range three-engined airliner

An airliner is a type of aircraft for transporting passengers and air cargo. Such aircraft are most often operated by airlines. Although the definition of an airliner can vary from country to country, an airliner is typically defined as an ai ...

. This particular Trident ( s/n 2109) was one of twenty-four de Havilland

The de Havilland Aircraft Company Limited () was a British aviation manufacturer established in late 1920 by Geoffrey de Havilland at Stag Lane Aerodrome Edgware on the outskirts of north London. Operations were later moved to Hatfield in H ...

D.H.121s (the name "Trident" was not introduced until September 1960) ordered by BEA in 1959 and was registered to the corporation in 1961 as By the time of ''Papa India''s first flight on 14 April 1964, de Havilland had lost their separate identity under Hawker Siddeley

Hawker Siddeley was a group of British manufacturing companies engaged in aircraft production. Hawker Siddeley combined the legacies of several British aircraft manufacturers, emerging through a series of mergers and acquisitions as one of onl ...

Aviation, and the aircraft was delivered to BEA on 2 May 1964. The Trident I was equipped with three interconnected high-lift device

In aircraft design and aerospace engineering, a high-lift device is a component or mechanism on an aircraft's wing that increases the amount of lift produced by the wing. The device may be a fixed component, or a movable mechanism which is deplo ...

s on each wing leading edge—two leading-edge droop flap

The leading-edge droop flap is a device on the leading edge of aircraft wings designed to improve airflow at high pitch angles (high angle of attack). The droop flap is similar to the leading-edge slat and the Krueger flap, but with the differenc ...

s outboard and a Krueger flap

Krueger flaps, or Krüger flaps, are lift enhancement devices that may be fitted to the leading edge of an aircraft wing. Unlike slats or droop flaps, the main wing upper surface and its nose is not changed. Instead, a portion of the lower wing ...

on the section closest to the fuselage.

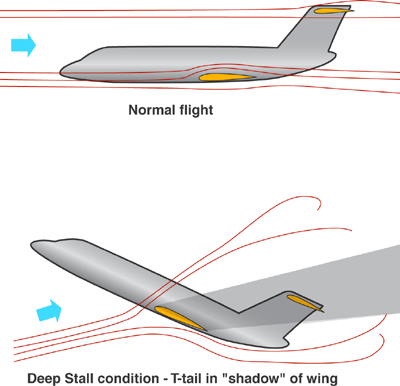

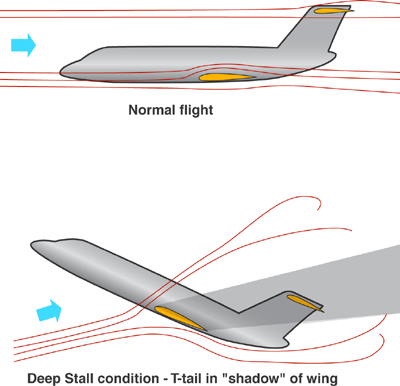

While technically advanced, the Trident (and other aircraft with a

While technically advanced, the Trident (and other aircraft with a T-tail

A T-tail is an empennage configuration in which the tailplane is mounted to the top of the fin. The arrangement looks like the capital letter T, hence the name. The T-tail differs from the standard configuration in which the tailplane is ...

arrangement) had potentially dangerous stalling characteristics. If its airspeed

In aviation, airspeed is the speed of an aircraft relative to the air. Among the common conventions for qualifying airspeed are:

* Indicated airspeed ("IAS"), what is read on an airspeed gauge connected to a Pitot-static system;

* Calibrated ...

was insufficient, and particularly if its high-lift devices were not extended at the low speeds typical of climbing away after take-off or of approaching to land, it could enter a deep stall (or "superstall") condition, in which the tail control surfaces become ineffective (as they are in the turbulence zone of the stalled main wing) from which recovery was practically impossible. Stewart 2001, p. 97.

The danger first came to light in a near-crash during a 1962 test flight when de Havilland

The de Havilland Aircraft Company Limited () was a British aviation manufacturer established in late 1920 by Geoffrey de Havilland at Stag Lane Aerodrome Edgware on the outskirts of north London. Operations were later moved to Hatfield in H ...

pilots Peter Bugge and Ron Clear were testing the Trident's stalling characteristics by pitching its nose progressively higher, thus reducing its airspeed. The Trident entered a deep stall after a critical angle of attack

In fluid dynamics, angle of attack (AOA, α, or \alpha) is the angle between a reference line on a body (often the chord line of an airfoil) and the vector representing the relative motion between the body and the fluid through which it is m ...

was reached. Eventually, it entered a flat spin, and appeared to be about to crash, but a wing dropped during the stall, and when corrected with rudder the other wing dropped. The aircraft continued rolling left and right until the nose pitched down and the crew were able to recover to normal flight. Bartelski 2001, p. 192. The incident resulted in the Trident being fitted with an automatic stall warning system known as a "stick shaker

A stick shaker is a mechanical device designed to rapidly and noisily vibrate the control yoke (the "stick") of an aircraft, warning the flight crew that an imminent aerodynamic stall has been detected. It is typically present on the majority of ...

", and a stall recovery system known as a "stick pusher

A stick pusher is a device installed in some fixed-wing aircraft to prevent the aircraft from entering an aerodynamic stall. Some large fixed-wing aircraft display poor post-stall handling characteristics or are vulnerable to deep stall. To preven ...

" which automatically pitched the aircraft down to build up speed if the crew failed to respond to the warning.

These systems were the subject of a comprehensive stall programme, involving some 3,500 stalls being performed by Hawker Siddeley before the matter was considered resolved by the Air Registration Board

The Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) is the statutory corporation which oversees and regulates all aspects of civil aviation in the United Kingdom. Its areas of responsibility include:

* Supervising the issuing of pilots' licences, testing of e ...

. The stall warning and recovery systems tended to over-react: of ten activations between the Trident entering service and June 1972, only half were genuine, although in the previous 6½ years there had been no false activations when an aircraft was in the air. AIB Report 4/73, p. 10. When BEA Trident pilots were questioned informally by one captain, over half of the pilots said that they would disable the protection systems on activation rather than let them recover the aircraft to a safe attitude. Random checks carried out by the airline after the accident showed that this was not the case; 21 captains stated that they had witnessed their co-pilots react correctly to any stall warnings. AIB Report 4/73, pp. 44–45.

Felthorpe accident

The aircraft model's potential to enter a deep stall was highlighted in the crash of Trident 1C ''G-ARPY'' on 3 June 1966 near Felthorpe in Norfolk during a test flight, with the loss of all four pilots on board. In this accident, the crew had deliberately switched off the stick shaker and stick pusher as required by the stall test schedule, and the probable cause was determined to be the crew's failure to take timely positive recovery action to counter an impending stall. The Confidential Human Factors Incident Reporting Programme (CHIRP), an experimental, voluntary, anonymous and informal system of reporting hazardous air events introduced within BEA in the late 1960s (and later adopted by theCivil Aviation Authority

A civil aviation authority (CAA) is a national or supranational statutory authority that oversees the regulation of civil aviation, including the maintenance of an aircraft register.

Role

Due to the inherent dangers in the use of flight vehicles, ...

and NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

), brought to light two near-accidents, the "Orly" and "Naples" incidents: these involved flight crew error in the first case and suspicion of the Trident's control layout in the second case. AIB Report 4/73, p. 52. Faith 1997, p. 175.

Orly (Paris) incident

In December 1968, the captain of a Trident 1C departing Paris-Orly Airport

Paris Orly Airport (french: Aéroport de Paris-Orly), commonly referred to as Orly , is one of two international airports serving the French capital, Paris, the other one being Charles de Gaulle Airport (CDG). It is located partially in Orly ...

for London tried to improve climb performance by retracting the flaps shortly after take-off. This was a non-standard procedure, and shortly afterward he also retracted the leading-edge droops. This configuration of high-lift device

In aircraft design and aerospace engineering, a high-lift device is a component or mechanism on an aircraft's wing that increases the amount of lift produced by the wing. The device may be a fixed component, or a movable mechanism which is deplo ...

s at a low airspeed would have resulted in a deep stall, but the co-pilot noticed the error, increased airspeed and re-extended the droops, and the flight continued normally. The event became known as the "Paris Incident" or the "Orly Incident" among BEA staff. Stewart 2001, p. 98.

Naples incident

Previous ground accident involving ''G-ARPI''

An accident affecting G-ARPI had occurred on 3 July 1968. Due to a control failure, an Airspeed Ambassador freight aircraft, ''G-AMAD'', deviated from the runway on landing at Heathrow and struck ''G-ARPI'' and its neighbouring sister aircraft, ''G-ARPT'', while they were parked unoccupied near Terminal 1, resulting in six fatalities from the freighter's eight occupants. ''G-ARPT'' was cut in two and damaged beyond economic repair; ''G-ARPI'' lost its tail fin, which was repaired at a cost of £750,000 (£ million today). ''G-ARPI'' performed satisfactorily thereafter, and the incident is thought to have had no bearing on its subsequent crash. Trident ''G-ARPI'' later suffered some minor undercarriage damage as a result of skidding off the runway atBasel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (B ...

during a cross-wind landing on 4 February 1970.

Crew and passengers

The crew on the day of the accident comprisedCaptain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Stanley Key as P1, Second Officer Jeremy Keighley as P2 and Second Officer Simon Ticehurst as P3. Captain Key was 51 and had 15,000 flying hours experience, including 4,000 on Tridents. Keighley was 22 and had joined line flying a month and a half earlier, with 29 hours as P2. Ticehurst was 24 and had over 1,400 hours, including 750 hours on Tridents. AIB Report 4/73, pp. 36–37. The cabin crew consisted of Senior Steward Frederick Farey, Steward Alan Lamb and Stewardess Jennifer Mowat (the youngest crew member on the flight, at 19).

Among the passengers were 29 Americans, 29 Belgians, 28 Britons, 12 Irish, four South Africans and three Canadians. There was also one passenger from each of French West Africa, India, Jamaica, Latin America, Nigeria and Thailand. The passengers included between 25 and 30 women and several children.

Among the passengers were 29 Americans, 29 Belgians, 28 Britons, 12 Irish, four South Africans and three Canadians. There was also one passenger from each of French West Africa, India, Jamaica, Latin America, Nigeria and Thailand. The passengers included between 25 and 30 women and several children.

Accident

''Note: All timings inGreenwich Mean Time

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is the mean solar time at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, counted from midnight. At different times in the past, it has been calculated in different ways, including being calculated from noon; as a c ...

(GMT) from the official accident report.''

Departure

call sign

In broadcasting and radio communications, a call sign (also known as a call name or call letters—and historically as a call signal—or abbreviated as a call) is a unique identifier for a transmitter station. A call sign can be formally ass ...

''Bealine 548'') Job 1994, p. 88. at 15:20 to prepare for a 15:45 departure.

At 15:36, flight dispatcher

A flight dispatcher (also known as an airline dispatcher or flight operations officer) assists in planning flight paths, taking into account aircraft performance and loading, enroute winds, thunderstorm and turbulence forecasts, airspace restricti ...

J. Coleman presented the load sheet to Key whose request for engine start clearance was granted three minutes later. As the doors were about to close, Coleman asked Key to accommodate a BEA flight crew that had to collect a Merchantman

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are u ...

aircraft from Brussels. The additional weight of the three crew members necessitated the removal of a quantity of mail and freight from the Trident to ensure its total weight (less fuel) did not exceed the permitted maximum of . This was exceeded by , but as there had been considerable fuel burnoff between startup and takeoff, the total aircraft weight (including fuel) was within the maximum permitted take-off weight. AIB Report 4/73, p. 3. Stewart 2001, p. 102.

The " deadheading" crew was led by Captain John Collins, an experienced former Trident First Officer, who was allocated the observer's seat on the flight deck. One seat, occupied by a baby, was freed by the mother holding them in her arms. Stewart 2001, p. 103.

The doors closed at 15:58 and at 16:00 Key requested

The doors closed at 15:58 and at 16:00 Key requested pushback

In aviation, pushback is an airport procedure during which an aircraft is pushed backwards away from its parking position, usually at an airport gate by external power. Pushbacks are carried out by special, low-profile vehicles called ''pushback ...

. At 16:03 BE 548 was cleared to taxi to the holding point adjacent to the start of Runway

According to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a runway is a "defined rectangular area on a land aerodrome prepared for the landing and takeoff of aircraft". Runways may be a man-made surface (often asphalt, concrete ...

28 Right. During taxi, at 16:06 the flight received its departure route clearance: a routing known as the "Dover One Standard Instrument Departure". This standard instrument departure involved taking-off to the west over the instrument landing system

In aviation, the instrument landing system (ILS) is a precision radio navigation system that provides short-range guidance to aircraft to allow them to approach a runway at night or in bad weather. In its original form, it allows an aircraft to ...

localiser and middle marker beacon of the reciprocal Runway 10 Left, turning left to intercept the 145° bearing to the Epsom

Epsom is the principal town of the Borough of Epsom and Ewell in Surrey, England, about south of central London. The town is first recorded as ''Ebesham'' in the 10th century and its name probably derives from that of a Saxon landowner. The ...

non-directional beacon

A non-directional beacon (NDB) or non-directional radio beacon is a radio beacon which does not include directional information. Radio beacons are radio transmitters at a known location, used as an aviation or marine navigational aid. NDB are ...

(NDB) (to be passed at or more), and then proceeding to Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maids ...

. Key advised the tower

A tower is a tall structure, taller than it is wide, often by a significant factor. Towers are distinguished from masts by their lack of guy-wires and are therefore, along with tall buildings, self-supporting structures.

Towers are specific ...

that he was ready for take-off and was cleared to do so. He subsequently reported an unspecified technical problem and remained at the holding point for two minutes to resolve it. Stewart 2001, p. 104.

At 16:08 Key again requested and received take-off clearance. A cross wind was blowing from 210° at . Conditions were turbulent, with driving rain and a low cloud base of ; broken cloud was also reported at , and the official report says that the crew would have been without any visual reference at "crucial times" during the flight. AIB Report 4/73, p. 12.taff author

Taff may refer to:

* River Taff, a large river in Wales

* ''Taff'' (TV series), a German tabloid news programme

* Trans-Atlantic Fan Fund, an organisation for science fiction fandom

People

* a demonym for anyone from south Wales

* Jerry Taff (b ...

22 June 1972.World News – Trident accident

''FLIGHT International'', pp. 888–890. Retrieved 30 December 2009. At 16:08:30 BE 548 began its take-off run, which lasted 44 seconds, the aircraft leaving the ground at an indicated airspeed (IAS) of . The safe climb speed ( V2) of was reached quickly, and the undercarriage was retracted. After 19 seconds in the air the

autopilot

An autopilot is a system used to control the path of an aircraft, marine craft or spacecraft without requiring constant manual control by a human operator. Autopilots do not replace human operators. Instead, the autopilot assists the operator' ...

was engaged at and ; the autopilot's airspeed lock was engaged even though the actual required initial climb speed was .

At 16:09:44 (74 seconds after the start of the take-off run), passing , Key began the turn towards the Epsom NDB and reported that he was climbing as cleared and the flight entered cloud. AIB Report 4/73, p. 2. At 16:10 (90 seconds), Key commenced a standard noise abatement procedure which involved reducing engine power. As part of this, at 16:10:03 (93 seconds) he retracted the flaps from their take-off setting of 20°. Shortly afterwards, BE 548 reported passing above ground level and was re-cleared to climb to . During the turn, the airspeed decreased to , below the target speed. Stewart 2001, p. 105.

Stall warnings

At 16:10:24 (114 seconds), the leading-edge devices were selected to be retracted at a height above the ground of and a speed of , AIB Report 4/73, p. 5. below the safe droop flap retraction speed of . One second afterwards, visual and audible warnings of a stall activated on the flight deck, followed at 16:10:26 (116 seconds) by a stick shake and at 16:10:27 (117 seconds) by a stick push which disconnected the autopilot, in turn activating a loud autopilot disconnect warning horn that continued to sound for the remainder of the flight. Key levelled the wings but held the aircraft's nose up, which kept theangle of attack

In fluid dynamics, angle of attack (AOA, α, or \alpha) is the angle between a reference line on a body (often the chord line of an airfoil) and the vector representing the relative motion between the body and the fluid through which it is m ...

high, further approaching a stall. Stewart 2001, p. 108.

By 16:10:32 (122 seconds), the leading-edge devices had stowed fully into the wing. The speed was , and height above the ground was , with the aircraft still held into its usual climb attitude. Key continued to hold the nose-up attitude when there was a second stick shake and stick push in the following two seconds. A third stick push followed 127 seconds into the flight but no recovery was attempted. One second later, the stall warning and recovery system was over-ridden by a flight crew member. Stewart 2001, p. 110.

At 16:10:39 (129 seconds), the aircraft had descended to and accelerated to as a result of the stall recovery system having pitched the aircraft's nose down to increase airspeed. ''G-ARPI'' was in a 16° banked turn to the left, still on course to intercept its assigned route. Key pulled the nose up once more to reduce airspeed slightly, to the normal 'droops extended' climb speed of , which further stalled the aircraft.

At 16:10:43 (133 seconds), the Trident entered a deep stall. It was descending through , its nose was pitched up by 31°, and its airspeed had fallen below the minimum indication of . At 16:10:47 (137 seconds) and , the Trident was descending at . Impact with the ground came at 16:11, 150 seconds after brake release.

The aircraft just cleared high-tension overhead power lines and came to rest on a narrow strip of land surrounded by tall trees immediately south of the A30 road

The A30 is a major road in England, running WSW from London to Land's End.

The road has been a principal axis in Britain from the 17th century to early 19th century, as a major coaching route. It used to provide the fastest route from Lond ...

, Stewart 2001, p. 112 and a short distance south of the King George VI Reservoir near Staines-upon-Thames

Staines-upon-Thames is a market town in northwest Surrey, England, around west of central London. It is in the Borough of Spelthorne, at the confluence of the River Thames and Colne. Historically part of Middlesex, the town was transferred t ...

. AIB Report 4/73, p. 13. There was no fire on impact, but one broke out during the rescue effort when cutting apparatus was used.

Eyewitnesses and rescue operations

There were three eyewitnesses; brothers Paul and Trevor Burke, aged 9 and 13, who were walking nearby, and a motorist who called at a house to telephone the airport. Air traffic controllers had not noticed the disappearance fromradar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

. Emergency services only became aware of the accident after 15 minutes and did not know the circumstances for nearly an hour. First on the scene was a nurse living nearby, who had been alerted by the boys, and an ambulance crew that happened to be driving past. A male passenger who had survived the accident was discovered in the aircraft cabin, but died soon after arrival at Ashford Ashford may refer to:

Places

Australia

*Ashford, New South Wales

*Ashford, South Australia

*Electoral district of Ashford, South Australia

Ireland

*Ashford, County Wicklow

*Ashford Castle, County Galway

United Kingdom

*Ashford, Kent, a town

**B ...

Hospital without recovering consciousness. A young girl was also found alive but died at the scene; there were no other survivors. Altogether, 30 ambulances and 25 fire engines attended the accident. Bartelski 2001, p. 188.

Drivers formed heavy traffic jams and were described by Minister of Aerospace Michael Heseltine

Michael Ray Dibdin Heseltine, Baron Heseltine, (; born 21 March 1933) is a British politician and businessman. Having begun his career as a property developer, he became one of the founders of the publishing house Haymarket. Heseltine served ...

on BBC Television that evening as "ghouls, unfortunate ghouls". Bartelski 2001, p. 190. Reports that the public impeded rescue services were dismissed during the inquiry. In addition, some witnesses claimed the traffic jams were the result of the recovery and rescue, during which the police closed the A30 road.

A BEA captain, Eric Pritchard, arrived soon after the bodies had been removed; he noted the condition of the wreckage and drew conclusions:

The accident was the worst air disaster in the United Kingdom until the Pan Am Flight 103

Pan Am Flight 103 was a regularly scheduled Pan Am transatlantic flight from Frankfurt to Detroit via a stopover in London and another in New York City. The transatlantic leg of the route was operated by ''Clipper Maid of the Seas'', a Boein ...

bombing over Lockerbie

Lockerbie (, gd, Locarbaidh) is a small town in Dumfries and Galloway, south-western Scotland. It is about from Glasgow, and from the border with England. The 2001 Census recorded its population as 4,009. The town came to international atte ...

, Scotland in 1988. Brookes 1996, p. 142. The crash was the first in the United Kingdom involving the loss of more than 100 lives. Gero 1997, p. 107.

Investigation and public inquiry

On Monday 19 June 1972Michael Heseltine

Michael Ray Dibdin Heseltine, Baron Heseltine, (; born 21 March 1933) is a British politician and businessman. Having begun his career as a property developer, he became one of the founders of the publishing house Haymarket. Heseltine served ...

told the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

that he had directed a Court of Inquiry, an ''ad hoc'' tribunal popularly called a "public inquiry

A tribunal of inquiry is an official review of events or actions ordered by a government body. In many common law countries, such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia and Canada, such a public inquiry differs from a royal commission in that ...

", to investigate and report on the accident. Public inquiries bypassed the usual British practice whereby the Accidents Investigation Branch

The Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) investigates civil aircraft accidents and serious incidents within the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and crown dependencies. It is also the Space Accident Investigation Authority (SAIA) ...

(AIB) investigated and reported on air crashes, and were held only in cases of acute public interest. On 14 July, the High Court Judge Sir Geoffrey Lane was appointed to preside over the inquiry as Commissioner.

The British aviation community was wary of public inquiries for several reasons. In such inquiries, AIB inspectors were on an equal footing with all other parties, and the ultimate reports were not drafted by them, but by the Commissioner and his or her Assessors. Proceedings were often adversarial, with counsel

A counsel or a counsellor at law is a person who gives advice and deals with various issues, particularly in legal matters. It is a title often used interchangeably with the title of ''lawyer''.

The word ''counsel'' can also mean advice given ...

for victims' families regularly attempting to secure positions for future litigation

-

A lawsuit is a proceeding by a party or parties against another in the civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today. The term "lawsuit" is used in reference to a civil act ...

, and deadlines were frequently imposed on investigators. Bartelski 2001, p. 207. Pressure of work caused by the Lane Inquiry was blamed for the death of a senior AIB inspector who committed suicide during the inquiry. Bartelski 2001, p. 199.

AIB investigation and coroner's inquest

The aircraft's twoflight data recorder

A flight recorder is an electronic recording device placed in an aircraft for the purpose of facilitating the investigation of aviation accidents and incidents. The device may often be referred to as a "black box", an outdated name which has ...

s were removed for immediate examination, and investigations at the site of the accident were completed within a week. The wreckage of ''Papa India'' was then removed to a hangar

A hangar is a building or structure designed to hold aircraft or spacecraft. Hangars are built of metal, wood, or concrete. The word ''hangar'' comes from Middle French ''hanghart'' ("enclosure near a house"), of Germanic origin, from Frankish ...

at the Royal Aircraft Establishment

The Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) was a British research establishment, known by several different names during its history, that eventually came under the aegis of the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD), before finally losing its identity in me ...

in Farnborough, Hampshire

Farnborough is a town in northeast Hampshire, England, part of the borough of Rushmoor and the Farnborough/Aldershot Built-up Area. Farnborough was founded in Saxon times and is mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. The name is formed fro ...

, for partial re-assembly aimed at checking the integrity of its flight control systems

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere (i.e. air flight or aviation) or through the vacuum of outer space (i.e. spaceflight). This can b ...

. An inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a c ...

was held into the 118 deaths, opening on 27 June 1972.

The pathologist

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in th ...

stated that Captain Key had an existing heart condition, atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a pattern of the disease arteriosclerosis in which the wall of the artery develops abnormalities, called lesions. These lesions may lead to narrowing due to the buildup of atheromatous plaque. At onset there are usually no s ...

, and had suffered a potentially distressing arterial event caused by raised blood pressure typical of stress, an event which was often interpreted by the public as a heart attack. Bartelski 2001, p. 198.

It had taken place "not more than two hours before the death and not less than about a minute" according to the pathologist's opinion given as evidence during the public inquiry. AIB Report 4/73, p. 26. In other words, Key could have suffered it at any time between the row in the crewroom and 90 seconds after the start of the take-off run (the instant of commencing noise abatement procedures). The pathologist could not specify the degree of discomfort or incapacitation which Key might have felt. The Captain's medical state continued to be the subject of "conflicting views of medical experts" throughout the inquiry and beyond.

Lane Inquiry

The public inquiry, known as the "Lane Inquiry", opened at thePiccadilly

Piccadilly () is a road in the City of Westminster, London, to the south of Mayfair, between Hyde Park Corner in the west and Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is part of the A4 road that connects central London to Hammersmith, Earl's Cour ...

Hotel in London on 20 November 1972, and continued until 25 January 1973, with a break over Christmas, despite expectations that it would end sooner. It was opened by Geoffrey Wilkinson of the AIB with a description of the accident, and counsel for the relatives of the crew members and passengers then presented the results of their private investigations. In particular, Lee Kreindler of the New York City Bar presented claims and arguments that were considered tendentious and inadmissible by pilots and press reporters. Bartelski 2001, p. 196. They involved hypotheses

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on previous obse ...

about the mental state of Captain Key, conjecture about his physical state (Kreindler highlighted disagreements between US and British cardiologists) and allegations about BEA management. The allegations were delivered using tactics considered as "bordering on the unethical". Bartelski 2001, p. 197.

The inquiry also conducted field inspections, flew in real Tridents and "flew" the BEA Trident simulator

A simulation is the imitation of the operation of a real-world process or system over time. Simulations require the use of models; the model represents the key characteristics or behaviors of the selected system or process, whereas the s ...

as well as observing the Hawker Siddeley Trident control systems rig. Its members visited the reassembled wreckage of ''G-ARPI'' at Farnborough and were followed by the press throughout their movements. The bare facts being more-or-less uncovered soon after the event, the inquiry was frustrated by the lack of a cockpit voice recorder

A flight recorder is an electronic recording device placed in an aircraft for the purpose of facilitating the investigation of aviation accidents and incidents. The device may often be referred to as a "black box", an outdated name which has ...

fitted to the accident aircraft. Bartelski 2001, p. 195.

The stall warning and stall recovery systems were at the centre of the inquiry, which examined in some detail their operation and why the flight crew might have over-ridden them. A three-way air pressure valve (part of the stall recovery system) was found to have been one sixth of a turn out of position, and the locking wire which secured it was missing. AIB Report 4/73, pp. 18–19. Calculations carried out by Hawker Siddeley determined that if the valve had been in this position during the flight then the reduction in engine power for the noise abatement procedure could have activated the warning light that indicated low air pressure in the system. The failure indications might have appeared just prior to take-off and could have accounted for the two-minute delay at the end of the runway. A captain who had flown ''Papa India'' on the morning of the accident flight noted no technical problems, and the public inquiry found that the position of the valve had no significant effect on the system.

Findings and recommendations

The Lane Report was published on 14 April 1973. Speaking in theHouse of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, Minister for Aerospace and Shipping Michael Heseltine

Michael Ray Dibdin Heseltine, Baron Heseltine, (; born 21 March 1933) is a British politician and businessman. Having begun his career as a property developer, he became one of the founders of the publishing house Haymarket. Heseltine served ...

paid tribute to the work done by Mr Justice Lane, Sir Morien Morgan

Sir Morien Bedford Morgan CB FRS (20 December 1912 – 4 April 1978), was a noted Welsh aeronautical engineer, sometimes known as "the Father of Concorde". He spent most of his career at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE), before moving to ...

and Captain Jessop for the work they had carried out during the inquiry into the accident.

The inquiry's findings as to the main causes of the accident, AIB Report 4/73, p. 54. were that:

*The captain failed to maintain the recommended airspeed.

*The leading-edge devices were retracted prematurely.

*The crew failed to monitor airspeed and aircraft configuration.

*The crew failed to recognise the reasons for the stall warnings and stall recovery system operation.

*The crew wrongly disabled the stall recovery system.

Underlying causes of the accident were also identified:

*That Captain Key was suffering from a heart condition.

*The presence of Captain Collins on the flight deck might have been a distraction.

*The lack of crew training on how to manage pilot incapacitation.

*The low flying-experience level of Second Officer Keighley.

*Apparent crew unawareness regarding the effects of an aircraft configuration change.

*Crew unawareness regarding the stall protection systems and the cause of the event.

*The absence of a baulk mechanism to prevent droop retraction at too low an airspeed.

Recommendations included an urgent call for cockpit voice recorders and for closer co-operation between the Civil Aviation Authority

A civil aviation authority (CAA) is a national or supranational statutory authority that oversees the regulation of civil aviation, including the maintenance of an aircraft register.

Role

Due to the inherent dangers in the use of flight vehicles, ...

and British airlines. AIB Report 4/73, p. 56. Although the report covered the state of industrial relations at BEA, no mention was made of it in its conclusions, despite the feelings of observers that it intruded directly and comprehensively onto the aircraft's flight deck. BEA ceased to exist as a separate entity in 1974, when it and the British Overseas Airways Corporation

British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) was the British state-owned airline created in 1939 by the merger of Imperial Airways and British Airways Ltd. It continued operating overseas services throughout World War II. After the pass ...

merged to form British Airways

British Airways (BA) is the flag carrier airline of the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in London, England, near its main hub at Heathrow Airport.

The airline is the second largest UK-based carrier, based on fleet size and passengers ...

. A recommendation of the report that all British-registered civil passenger-carrying aircraft of more than all-up weight should be equipped with cockpit voice recorders resulted in their fitting becoming mandatory on larger British-registered airliners from 1973. AIB Report 4/73, p. 59.

One issue treated as secondary at the inquiry was the presence in the flight deck observer's seat of Captain Collins. The Lane report recommended greater caution in allowing off-duty flight crew members to occupy flight deck seats, and aired speculation that Collins might have been distracting his colleagues. The report noted that Collins' body was found to be holding a can of aerosol air freshener in its right hand. Sources close to the events of the time suggest that Collins played an altogether more positive role by attempting to lower the leading-edge devices in the final seconds of the flight; Eric Pritchard, a Trident captain who happened to be the first airman at the accident site, recalled that a fireman had stated that Collins was lying across the centre pedestal and noted himself that his earphones had fallen into the right-hand-side footwell of the flight deck, diagonally across from the observer's seat, as might be expected if he had attempted to intervene as a last resort. Bartelski 2001, p. 204.

There were protests at the conduct of the inquiry by BALPA (which likened it to "a lawyers' picnic"), and by the Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators

The Honourable Company of Air Pilots, formerly the Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators (GAPAN), is one of the Livery Companies of the City of London. The Company was founded in 1929, and became a Livery Company in 1956. Elizabeth II granted ...

which condemned the rules of evidence adopted and the adversarial nature of the proceedings. Observers also pointed to an unduly-favourable disposition by the inquiry to Hawker Siddeley, manufacturer of the Trident, and to the makers of the aircraft's systems. Debate about the inquiry continued throughout 1973 and beyond. Bartelski 2001, p. 194.

The accident led to a much greater emphasis on crew resource management

Crew resource management or cockpit resource management (CRM)Diehl, Alan (2013) "Air Safety Investigators: Using Science to Save Lives-One Crash at a Time." Xlibris Corporation. . http://www.prweb.com/releases/DrAlanDiehl/AirSafetyInvestigators/ ...

training, a system of flight deck safety awareness that remains in use today.

Victims and memorials

All 118 persons aboard the aircraft were killed: 112 passengers and six crew members. Among the passengers were 12 senior businessmen from

All 118 persons aboard the aircraft were killed: 112 passengers and six crew members. Among the passengers were 12 senior businessmen from Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

, including the head of the Confederation of Irish Industry, who were en route to Brussels for meetings preparatory to Irish accession to the European Economic Community.

A group of sixteen doctors and senior staff from the Royal London Homeopathic Hospital

The Royal London Hospital for Integrated Medicine (formerly the Royal London Homoeopathic Hospital) is a specialist alternative medicine hospital located in London, England and a part of University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. ...

were also on board, and a memorial bench

A memorial bench, memorial seat or death bench is a piece of outdoor furniture which commemorates a dead person. Such benches are typically made of wood, but can also be made of metal, stone, or synthetic materials such as plastics. Typically mem ...

to them was placed close to Great Ormond Street Hospital

Great Ormond Street Hospital (informally GOSH or Great Ormond Street, formerly the Hospital for Sick Children) is a children's hospital located in the Bloomsbury area of the London Borough of Camden, and a part of Great Ormond Street Hospita ...

in Queen Square.

Former CIA official Carmel Offie

Carmel Offie (September 22, 1909 – June 18, 1972) was a U.S. State Department and later a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) official. He was dismissed from the CIA in 1950 after an arrest a few years earlier brought his homosexuality to the atte ...

, who had been dismissed for homosexuality, considered to be a security risk factor at the time, was also on board.

Two memorials to all the victims were dedicated on 18 June 2004 in the town of Staines. The first is a stained-glass window in St Mary's Church where an annual memorial service is held on 18 June. The second is a garden near the end of Waters Drive in the Moormede Estate, close to the accident site. On 18 June 2022, the fiftieth anniversary, there was a memorial service attended by relatives of those who died, members of the emergency services, the Lord Lieutenant of Surrey, the local MP, and the chairman of British Airways.

Dramatisation

The story of the accident was featured on the thirteenth season of the Canadian television show ''Mayday

Mayday is an emergency procedure word used internationally as a distress signal in voice-procedure radio communications.

It is used to signal a life-threatening emergency primarily by aviators and mariners, but in some countries local organiz ...

'' in an episode entitled " Fight to the Death" (known as ''Air Disasters'' in the US, and as '' Air Crash Investigation'' in the UK and the rest of the world). The story was also featured in an episode of ''Air Crash Confidential'' produced by World Media Rights; made at the FAST Museum, Farnborough, UK using the cockpit of a Trident 3 (G-AWZI).

See also

*List of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft

This list of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft includes notable events that have a corresponding Wikipedia article. Entries in this list involve passenger or cargo aircraft that are operating commercially and meet this list ...

References

Footnotes

Citations

Bibliography

*Bartelski, Jan. ''Disasters in the Air: Mysterious Air Accidents Explained'', Shrewsbury, Shropshire. Airlife Publishing Ltd, 2001. *Brookes, Andrew. ''Disaster in the air''. Shepperton, Surrey. Ian Allan Ltd. 1996.Civil Aircraft Accident Report 4/73: ''Trident I G-ARPI: Report of the Public Inquiry into the Causes and Circumstances of the Accident near Staines on 18 June 1972''.

Accident Investigation Branch, Department of Trade and Industry. HMSO, London, 1973.

Civil Aircraft Accident Report 4/73: ''Trident I G-ARPI: Report of the Public Inquiry into the Causes and Circumstances of the Accident near Staines on 18 June 1972 – Appendix A''

Accident Investigation Branch, Department of Trade and Industry. HMSO, London, 1973. *Ellis, Ken. ''Wrecks and Relics – 19th Edition'', Hinckley, Leicestershire. Midland Publishing, 2004. *Faith, Nicholas. ''Black Box''. London, Macmillan Publishers Ltd. 1997. *Gero, David. ''Aviation Disasters''. Yeovil, Somerset. Patrick Stephens Ltd (Haynes Publishing). 1997 *Job, Macarthur. ''Air Disaster Volume 1''. Weston Creek, ACT, Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd. 1994 *Roach, John and Eastwood, Tony. ''Jet Airliner Production List'', West Drayton, England, The Aviation Hobby Shop, 1992. *Stewart, Stanley. ''Air Disasters'' London, Ian Allan Publishing, 2001.

External links

*Image of ''Papa India'' prior to the accident

* ttp://www.felthorpe.net/History.html Images of the crash site of ''G-ARPY'' (the 'Felthorpe accident')br> Captain Stanley Key

pictured (bottom right) at a BALPA party on 7 December 1955 talking to John Profumo, in a 1955 ''Flight'' news item

"Inquiry Briefing"

a 1972 ''Flight'' article

a 1972 ''Flight'' article

a 1972 ''Flight'' article {{Use dmy dates, date=October 2022 Aviation accidents and incidents in 1972 1972 disasters in the United Kingdom 1972 in England Disasters in Surrey Aviation accidents and incidents in England Accidents and incidents involving the Hawker Siddeley Trident Flight 548 Transport in Surrey Staines-upon-Thames June 1972 events in Europe Airliner accidents and incidents in the United Kingdom Airliner accidents and incidents caused by pilot error Airliner accidents and incidents caused by stalls