Black Sox on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Black Sox Scandal was a

White Sox club owner

White Sox club owner

A meeting of White Sox players—including those committed to going ahead and those just ready to listen—took place on September 21, in Chick Gandil's room at the

A meeting of White Sox players—including those committed to going ahead and those just ready to listen—took place on September 21, in Chick Gandil's room at the

The extent of Joe Jackson's part in the big conspiracy remains controversial. Jackson maintained that he was innocent. He had a Series-leading .375

The extent of Joe Jackson's part in the big conspiracy remains controversial. Jackson maintained that he was innocent. He had a Series-leading .375

Chicago Historical Society: Black Sox

SABR Digital Library: Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox

* Asinof, Eliot. ''Eight Men Out''. New York: Henry Holt, 1963. * Carney, Gene. ''Burying the Black Sox''. Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, 2007. * Ginsburg, Daniel E. ''The Fix Is In: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals''. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1995. * Gropman, Donald. ''Say It Ain't So, Joe!: The Story of Shoeless Joe Jackson''. Boston: Little, Brown, 1979. * Pietrusza, David ''Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis'' South Bend, IN: Diamond Communications, 1998. * Pietrusza, David ''Rothstein: The Life, Times, and Murder of the Criminal Genius Who Fixed the 1919 World Series''. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2003.

Chicagohs.org

Chicago Historical Society on the Black Sox

''Eight Men Out''

– IMDb page on the 1988 movie, written and directed by

baseball-reference.com

box scores and info on each game {{Sports Corruption Scandals

Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (AL), ...

game-fixing scandal in which eight members of the Chicago White Sox

The Chicago White Sox are an American professional baseball team based in Chicago. The White Sox compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) Central division. The team is owned by Jerry Reinsdorf, and ...

were accused of throwing the 1919 World Series

The 1919 World Series was the championship series in Major League Baseball for the 1919 season. The 16th edition of the World Series, it matched the American League champion Chicago White Sox against the National League champion Cincinnati Reds. ...

against the Cincinnati Reds in exchange for money from a gambling

Gambling (also known as betting or gaming) is the wagering of something of value ("the stakes") on a random event with the intent of winning something else of value, where instances of strategy are discounted. Gambling thus requires three el ...

syndicate led by Arnold Rothstein

Arnold Rothstein (January 17, 1882 – November 4, 1928), nicknamed "The Brain", was an American racketeer, crime boss, businessman, and gambler in New York City. Rothstein was widely reputed to have organized corruption in professional athletic ...

. As a response, the National Baseball Commission

The National Baseball Commission was the governing body of Major League Baseball and Minor League Baseball from 1903 to 1920. It consisted of a chairman, the presidents of the National League (NL) and American League (AL), and a secretary. The ...

was dissolved and Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis

Kenesaw Mountain Landis (; November 20, 1866 – November 25, 1944) was an American jurist who served as a United States federal judge from 1905 to 1922 and the first Commissioner of Baseball from 1920 until his death. He is remembered for his ...

was appointed to be the first Commissioner of Baseball

The Commissioner of Baseball is the chief executive officer of Major League Baseball (MLB) and the associated Minor League Baseball (MiLB) – a constellation of leagues and clubs known as "organized baseball". Under the direction of the Commiss ...

, and given absolute control over the sport to restore its integrity.

Despite acquittals in a public trial in 1921, Judge Landis permanently banned all eight men from professional baseball. The punishment was eventually defined by the Baseball Hall of Fame to include banishment from consideration for the Hall. Despite requests for reinstatement in the decades that followed (particularly in the case of Shoeless Joe Jackson

Joseph Jefferson Jackson (July 16, 1887 – December 5, 1951), nicknamed "Shoeless Joe", was an American outfielder who played Major League Baseball (MLB) in the early 1900s. Although his .356 career batting average is the fourth highest ...

), the ban remained.

Background

Tension in the clubhouse and Charles Comiskey

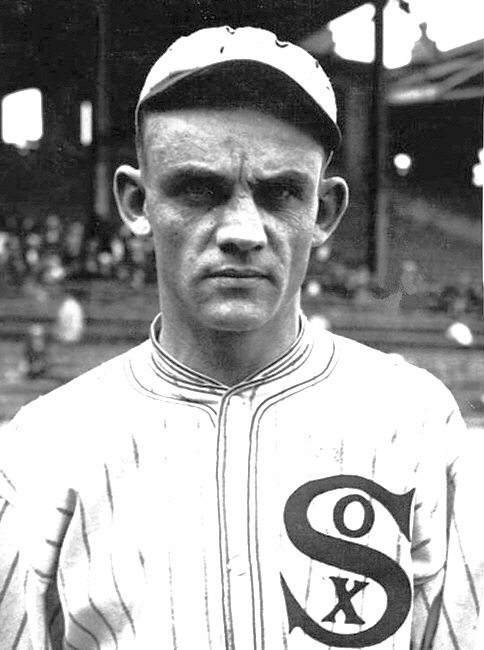

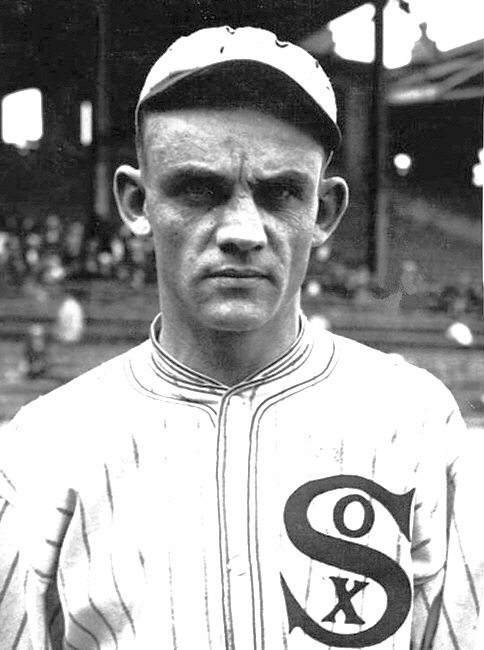

White Sox club owner

White Sox club owner Charles Comiskey

Charles Albert Comiskey (August 15, 1859 – October 26, 1931), nicknamed "Commy" or "The Old Roman", was an American Major League Baseball player, manager and team owner. He was a key person in the formation of the American League, and was also ...

, himself a prominent MLB player from 1882–1894, was widely disliked by the players and was resented for his miserliness. Comiskey, who as a player had taken part in the Players' League labor rebellion in 1890, long had a reputation for underpaying his players, even though they were one of the top teams in the league and had already won the 1917 World Series

The 1917 World Series was the championship series in Major League Baseball for the 1917 season. The 14th edition of the World Series, it matched the American League champion Chicago White Sox against the National League champion New York Giants ...

.

Because of baseball's reserve clause

The reserve clause, in North American professional sports, was part of a player contract which stated that the rights to players were retained by the team upon the contract's expiration. Players under these contracts were not free to enter into an ...

, any player who refused to accept a contract was prohibited from playing baseball on any other professional team under the auspices of "Organized Baseball." Players could not change teams without permission from their current team, and without a union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

the players had no bargaining power. Comiskey was probably no worse than most owners. In fact, Chicago had the largest team payroll in 1919. In the era of the reserve clause, gamblers could find players on many teams looking for extra cash—and they did.

The White Sox clubhouse was divided into two factions. One group resented the more straitlaced players (later called the "Clean Sox"), a group that included players like second baseman Eddie Collins, a graduate of Columbia College of Columbia University

Columbia College is the oldest undergraduate college of Columbia University, situated on the university's main campus in Morningside Heights in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded by the Church of England in 1754 as King's ...

; catcher

Catcher is a position in baseball and softball. When a batter takes their turn to hit, the catcher crouches behind home plate, in front of the ( home) umpire, and receives the ball from the pitcher. In addition to this primary duty, the ca ...

Ray Schalk

Raymond William Schalk (August 12, 1892 – May 19, 1970) was an American professional baseball player, coach, manager and scout. He played as a catcher in Major League Baseball for the Chicago White Sox for the majority of his career. Known f ...

, and pitcher

In baseball, the pitcher is the player who throws ("pitches") the baseball from the pitcher's mound toward the catcher to begin each play, with the goal of retiring a batter, who attempts to either make contact with the pitched ball or draw ...

s Red Faber

Urban Clarence "Red" Faber (September 6, 1888 – September 25, 1976) was an American right-handed pitcher in Major League Baseball from through , playing his entire career for the Chicago White Sox. He was a member of the 1919 team but was no ...

and Dickey Kerr

Richard Henry Kerr (July 3, 1893 – May 4, 1963) was an American professional baseball pitcher for the Chicago White Sox of Major League Baseball. He also served as a coach and manager in the minor leagues.

Early life

Kerr was born in St. Loui ...

. By contemporary accounts, the two factions rarely spoke to each other on or off the field, and the only thing they had in common was a resentment of Comiskey.

The conspiracy

A meeting of White Sox players—including those committed to going ahead and those just ready to listen—took place on September 21, in Chick Gandil's room at the

A meeting of White Sox players—including those committed to going ahead and those just ready to listen—took place on September 21, in Chick Gandil's room at the Ansonia Hotel

The Ansonia is a building on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City, located at 2109 Broadway, between 73rd and 74th Streets. It was originally built as a residential hotel by William Earle Dodge Stokes, the Phelps-Dodge copper heir ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

. Buck Weaver

George Daniel "Buck" Weaver (August 18, 1890 – January 31, 1956) was an American shortstop and third baseman. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Chicago White Sox. Weaver played for the 1917 World Series champion White Sox, then ...

was the only player to attend the meetings who did not receive money. Nevertheless, he was later banned along with the others for knowing about the fix but not reporting it.

Although he hardly played in the series, utility infielder Fred McMullin

Fred Drury McMullin (October 13, 1891 – November 20, 1952) was an American Major League Baseball third baseman. He is best known for his involvement in the 1919 Black Sox scandal.

Early life

Fred McMullin was born to Robert and Minnie McM ...

got word of the fix and threatened to report the others unless he was in on the payoff. As a small coincidence, McMullin was a former teammate of William "Sleepy Bill" Burns, who had a minor role in the fix. Both had played for the Los Angeles Angels

The Los Angeles Angels are an American professional baseball team based in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. The Angels compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) West division. Since 1966, the team h ...

of the Pacific Coast League, and Burns had previously pitched for the White Sox in 1909 and 1910. Star outfielder

An outfielder is a person playing in one of the three defensive positions in baseball or softball, farthest from the batter. These defenders are the left fielder, the center fielder, and the right fielder. As an outfielder, their duty is to c ...

Shoeless Joe Jackson

Joseph Jefferson Jackson (July 16, 1887 – December 5, 1951), nicknamed "Shoeless Joe", was an American outfielder who played Major League Baseball (MLB) in the early 1900s. Although his .356 career batting average is the fourth highest ...

was mentioned as a participant but did not attend the meetings, and his involvement is disputed.

The scheme got an unexpected boost when the straitlaced Faber could not pitch due to a bout with the flu. Years later, Schalk said that if Faber had been available, the fix would have likely never happened, since Faber would have almost certainly started games that went instead to two of the alleged conspirators, pitchers Eddie Cicotte

Edward Victor Cicotte (; June 19, 1884 – May 5, 1969), nicknamed "Knuckles", was an American right-handed pitcher in Major League Baseball best known for his time with the Chicago White Sox. He was one of eight players permanently ineligible f ...

and Lefty Williams

Claude Preston "Lefty" Williams (March 9, 1893 – November 4, 1959) was an American pitcher in Major League Baseball. He is probably best known for his involvement in the 1919 World Series fix, known as the Black Sox Scandal.

Career

Willia ...

.

On October 1, the day of Game One, there were rumors amongst gamblers that the series was fixed, and a sudden influx of money being bet on Cincinnati caused the odds against them to fall rapidly. These rumors also reached the press box where a number of correspondents, including Hugh Fullerton

Hugh Stuart Fullerton III (10 September 1873 – 27 December 1945) was an American sportswriter in the first half of the 20th century. He was one of the founders of the Baseball Writers' Association of America. He is best remembered for his role ...

of the '' Chicago Herald and Examiner'' and ex-player and manager Christy Mathewson

Christopher Mathewson (August 12, 1880 – October 7, 1925), nicknamed "Big Six", "the Christian Gentleman", "Matty", and "the Gentleman's Hurler", was a Major League Baseball right-handed pitcher, who played 17 seasons with the New York Gia ...

, resolved to compare notes on any plays and players that they felt were questionable. However, most fans and observers were taking the series at face value. On October 2, the '' Philadelphia Bulletin'' published a poem which would quickly prove to be ironic:

After throwing a strike with his first pitch of the Series, Cicotte's second pitch struck Cincinnati leadoffStill, it really doesn't matter, After all, who wins the flag. Good clean sport is what we're after, And we aim to make our brag To each near or distant nation Whereon shines the sporting sun That of all our games gymnastic Base ball is the cleanest one!

hitter

In baseball, batting is the act of facing the opposing pitcher and trying to produce offense for one's team. A batter or hitter is a person whose turn it is to face the pitcher. The three main goals of batters are to become a baserunner, to driv ...

Morrie Rath

Morris Charles Rath (December 25, 1887 – November 18, 1945) was an American baseball player. He played second base in Major League Baseball for the Philadelphia Athletics, Cleveland Naps, Chicago White Sox, and Cincinnati Reds. Rath was the ...

in the back, delivering a pre-arranged signal confirming the players' willingness to go through with the fix. In the fourth inning, Cicotte made a bad throw to Swede Risberg at second base. Sportswriters found the unsuccessful double play to be suspicious.

Williams, one of the "Eight Men Out", lost three games, a Series record. Rookie Dickie Kerr

Richard Henry Kerr (July 3, 1893 – May 4, 1963) was an American professional baseball pitcher for the Chicago White Sox of Major League Baseball. He also served as a coach and manager in the minor leagues.

Early life

Kerr was born in St. L ...

, who was not part of the fix, won both of his starts. But the gamblers were now reneging on their promised progress payments (to be paid after each game lost), claiming that all the money was let out on bets and was in the hands of the bookmaker

A bookmaker, bookie, or turf accountant is an organization or a person that accepts and pays off bets on sporting and other events at agreed-upon odds.

History

The first bookmaker, Ogden, stood at Newmarket in 1795.

Range of events

Bookm ...

s. After Game 5, angry about the non-payment of promised money, the players involved in the fix attempted to doublecross the gamblers and won Games 6 and 7 of the best-of-nine Series.

Before Game 8, threats of violence were made on the gamblers' behalf against players and family members. Williams started Game 8, but gave up four straight one-out hits for three runs before manager Kid Gleason

William Jethro "Kid" Gleason (October 26, 1866 – January 2, 1933) was an American Major League Baseball (MLB) player and manager. Gleason managed the Chicago White Sox from 1919 through 1923. His first season as a big league manager was notabl ...

relieved him. The White Sox lost Game 8 (and the series) on October 9, 1919. Besides Weaver, the players involved in the scandal received $5,000 each or more (), with Gandil taking $35,000 ().

Fallout

Grand jury (1920)

Rumors of the fix dogged the White Sox throughout the 1920 season as they battled theCleveland Indians

The Cleveland Guardians are an American professional baseball team based in Cleveland. The Guardians compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) Central division. Since , they have played at Progressive Fi ...

for the American League

The American League of Professional Baseball Clubs, known simply as the American League (AL), is one of two leagues that make up Major League Baseball (MLB) in the United States and Canada. It developed from the Western League, a minor league ...

pennant, and stories of corruption touched players on other clubs as well. At last, in September 1920, a grand jury was convened to investigate; Cicotte confessed to his participation in the scheme to the grand jury on September 28.

On the eve of their final season series, the White Sox were in a virtual tie for first place with the Indians. The Sox would need to win all three of their remaining games and then hope for Cleveland to stumble, as the Indians had more games left to play than the Sox. Despite the season being on the line, Comiskey suspended the seven White Sox still in the majors (Gandil had not returned to the team in 1920 and was playing semi-pro ball). He said that he had no choice but to suspend them, even though this action likely cost the Sox any chance of winning a second consecutive pennant. The Sox lost two of the three games in the final series against the St. Louis Browns

The St. Louis Browns were a Major League Baseball team that originated in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, as the Milwaukee Brewers. A charter member of the American League (AL), the Brewers moved to St. Louis, Missouri, after the 1901 season, where they p ...

and finished in second place, two games behind the Indians, who went on to win the World Series

The World Series is the annual championship series of Major League Baseball (MLB) in the United States and Canada, contested since 1903 between the champion teams of the American League (AL) and the National League (NL). The winner of the World ...

.

The grand jury handed down its decision on October 22, 1920, and eight players and five gamblers were implicated. The indictment

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use the felonies concept often use that of a ...

s included nine counts of conspiracy to defraud Conspiracy to defraud is an offence under the common law of England and Wales and Northern Ireland.

England and Wales

The standard definition of a conspiracy to defraud was provided by Lord Dilhorne in '' Scott v Metropolitan Police Commissioner'' ...

. The ten players not implicated in the gambling scandal, as well as manager Kid Gleason

William Jethro "Kid" Gleason (October 26, 1866 – January 2, 1933) was an American Major League Baseball (MLB) player and manager. Gleason managed the Chicago White Sox from 1919 through 1923. His first season as a big league manager was notabl ...

, were each given bonus checks in the amount of $1,500 () by Comiskey in the fall of 1920, the amount equaling the difference between the winners' and losers' share for participation in the 1919 World Series.

Trial (1921)

The trial began on June 27, 1921 in Chicago, but was delayed by Judge Hugo Friend because two defendants, Ben Franklin and Carl Zork, claimed to be ill.Right fielder

A right fielder, abbreviated RF, is the outfielder in baseball or softball who plays defense in right field. Right field is the area of the outfield to the right of a person standing at home plate and facing towards the pitcher's mound. In the ...

Shano Collins

John Francis "Shano" Collins (December 4, 1885 – September 10, 1955) was an American right fielder and first baseman in Major League Baseball for the Chicago White Sox and Boston Red Sox.

Early life

Collins was born on December 4, 1885 in Bost ...

was named as the wronged party in the indictments, accusing his corrupt teammates of having cost him $1,784 as a result of the scandal. Before the trial, key evidence went missing from the Cook County

Cook County is the most populous county in the U.S. state of Illinois and the second-most-populous county in the United States, after Los Angeles County, California. More than 40% of all residents of Illinois live within Cook County. As of 20 ...

courthouse, including the signed confession

A confession is a statement – made by a person or by a group of persons – acknowledging some personal fact that the person (or the group) would ostensibly prefer to keep hidden. The term presumes that the speaker is providing information th ...

s of Cicotte and Jackson, who subsequently recanted their confessions. Some years later, the missing confessions reappeared in the possession of Comiskey's lawyer.

On July 1, the prosecution

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the common law adversarial system or the Civil law (legal system), civil law inquisitorial system. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the ...

announced that former White Sox player "Sleepy Bill" Burns, who was under indictment for his part in the scandal, had turned state's evidence and would testify. During jury selection on July 11, several members of the current White Sox team, including manager Kid Gleason, visited the courthouse, chatting and shaking hands with the indicted ex-players; at one point they even tickled Weaver, who was known to be quite ticklish. Jury selection took several days, but on July 15 twelve jurors were finally empaneled in the case.

Trial testimony began on July 18, 1921, when prosecutor Charles Gorman outlined the evidence he planned to present against the defendants:

The spectators added to the bleacher appearance of the courtroom, for most of them sweltered in shirtsleeves, and collars were few. Scores of small boys jammed their way into the seats and as Mr. Gorman told of the alleged sell-out, they repeatedly looked at each other in awe, remarking under their breaths: 'What do you think of that?' or 'Well, I'll be darned.'White Sox President Charles Comiskey was then called to the stand, and became so agitated with questions being posed by the defense that he rose from the witness chair and shook his fist at the defendants' counsel, Ben Short. The most explosive testimony began the following day, July 19, when Burns took the stand and admitted that members of the White Sox had intentionally fixed the 1919 World Series; Burns mentioned the involvement of Rothstein among others, and testified that Cicotte had threatened to throw the ball clear out of the park if needed to lose a game. After additional testimony and evidence, on July 28 the defense rested and the case went to the jury. The jury deliberated for less than three hours before returning verdicts of not guilty on all charges for all of the accused players.

Landis appointed Commissioner, bans all eight players (1921)

Long before the scandal broke, many of baseball's owners had nursed longstanding grievances with the way the game was then governed by the National Commission. The scandal and the damage it caused to the game's reputation gave owners the resolve to make major changes to the governance of the sport. The owners' original plan was to appoint the widely respected federal judge and noted baseball fanKenesaw Mountain Landis

Kenesaw Mountain Landis (; November 20, 1866 – November 25, 1944) was an American jurist who served as a United States federal judge from 1905 to 1922 and the first Commissioner of Baseball from 1920 until his death. He is remembered for his ...

to head a reformed three-member National Commission. However, Landis made it clear to the owners that he would only accept an appointment as the game's ''sole'' Commissioner, and even then only on the condition that he be granted essentially unchecked power over the sport. The owners, desperate to clean up the game's image, agreed to his terms, and vested him with virtually unlimited authority over every person in both the major and minor leagues. It was controversial at the time for the MLB to move toward a single commissioner with sole governance on behalf of the owners.

Upon taking office prior to the 1921 Major League Baseball season

The 1921 Major League Baseball season, ended when the New York Giants beat the New York Yankees in Game 8 of the World Series. 1921 was the first of three straight seasons in which the Yankees would lead the majors in wins. Babe Ruth broke the s ...

, one of Landis' first acts as Commissioner was to use his new powers to place the eight accused players on an " ineligible list", a decision that effectively left them suspended indefinitely from all of "organized" professional baseball (although not from semi-pro barnstorming

Barnstorming was a form of entertainment in which stunt pilots performed tricks individually or in groups that were called flying circuses. Devised to "impress people with the skill of pilots and the sturdiness of planes," it became popular in ...

teams).

Following the players' acquittals, Landis was quick to quash any prospect that he might reinstate the implicated players. On August 3, 1921, the day after the players were acquitted, Commissioner Landis issued his own verdict:

Making use of a precedent that had previously seen Babe Borton

William Baker "Babe" Borton (August 14, 1888 – July 29, 1954) was a Major League Baseball first baseman. Borton played for the Chicago White Sox, New York Yankees, St. Louis Terriers, and St. Louis Browns from 1912 to 1916. He stood .

Biograph ...

, Harl Maggert, Gene Dale

Emmett Eugene Dale (June 16, 1889 – March 20, 1958), sometimes referred to as Jean Dale, was an American professional baseball player. Dale was a pitcher, and played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the St. Louis Cardinals (1911–1912) and ...

, and Bill Rumler

William George Rumler (March 27, 1891 – May 26, 1966), known as James Rumler during the 1918 season, and Red Moore during the 1921 season, was a professional baseball player, whose career spanned 19 seasons, three of which were spent in Major Le ...

banned from the Pacific Coast League for fixing games, Landis made it clear that all eight accused players would remain on the "ineligible list", banning them from organized baseball. The Commissioner took the line that while the players had been acquitted in court, there was no dispute they had broken the rules of baseball, and none of them could ever be allowed back in the game if it were to regain the trust of the public. Comiskey supported Landis by giving the seven who remained under contract to the White Sox their unconditional release.

Following the Commissioner's statement, it was universally understood that all eight implicated White Sox players were to be banned from Major League Baseball for life. Two other players believed to be involved were also banned. One of them was Hal Chase, who had been effectively blackballed from the majors in 1919 for a long history of throwing games and had spent 1920 in the minors. He was rumored to have been a go-between for Gandil and the gamblers, though it has never been confirmed. Regardless of this, it was understood that Landis' announcement not only formalized his 1919 blacklisting from the majors but barred him from the minors as well.

Landis, relying upon his years of experience as a federal Judge and attorney, used this decision (this "case") as the founding precedent (of the reorganized league) for the Commissioner of Baseball, to be the highest, and final authority over this organized professional sport in the United States. He established the precedent that the Commissioner was invested by the league with plenary power

A plenary power or plenary authority is a complete and absolute power to take action on a particular issue, with no limitations. It is derived from the Latin term ''plenus'' ("full").

United States

In United States constitutional law, plenary p ...

; and the responsibility to determine the fitness or suitability of anyone, anything, or any circumstance, to be associated with professional baseball, past, present, and future.

Banned players

Eight members of the White Sox baseball team were banned by Landis for their involvement in the fix: * Arnold "Chick" Gandil, first baseman. The leader of the players who were in on the fix. He did not play in the majors in 1920, playing semi-pro ball instead. In a 1956 ''Sports Illustrated

''Sports Illustrated'' (''SI'') is an American sports magazine first published in August 1954. Founded by Stuart Scheftel, it was the first magazine with circulation over one million to win the National Magazine Award for General Excellence twi ...

'' article, he expressed remorse for the scheme but wrote that the players had actually abandoned it when it became apparent they were going to be watched closely. According to Gandil, the players' numerous errors were a result of fear that they were being watched.

* Eddie Cicotte

Edward Victor Cicotte (; June 19, 1884 – May 5, 1969), nicknamed "Knuckles", was an American right-handed pitcher in Major League Baseball best known for his time with the Chicago White Sox. He was one of eight players permanently ineligible f ...

, pitcher. Admitted involvement in the fix.

* Oscar "Happy" Felsch, center fielder.

* "Shoeless" Joe Jackson, the star outfielder and one of the best hitters in the game, confessed in sworn grand jury testimony to having accepted $5,000 cash from the gamblers. It was also Jackson’s sworn testimony that he never met or spoke to any of the gamblers and was only told about the fix through conversations with other White Sox players. The other players that were in on the fix informed him that he would be getting $20,000 cash divided up in equal payments after each loss. Jackson’s testimony was that he played to win in the entire Series and did nothing on the field to throw any of the games in any way. His roommate, pitcher Lefty Williams, brought $5,000 cash up to their hotel room after losing Game 4 in Chicago and threw it down as they were packing to leave to travel back to Cincinnati. This was the only money that Jackson received at any time. He later recanted his confession and professed his innocence to no effect until his death in 1951. The extent of Jackson's collaboration with the scheme is hotly debated.

* Fred McMullin

Fred Drury McMullin (October 13, 1891 – November 20, 1952) was an American Major League Baseball third baseman. He is best known for his involvement in the 1919 Black Sox scandal.

Early life

Fred McMullin was born to Robert and Minnie McM ...

, utility infielder. McMullin would not have been included in the fix had he not overheard the other players' conversations. His role as team scout may have had more impact on the fix since he saw minimal playing time in the series.

* Charles "Swede" Risberg, shortstop

Shortstop, abbreviated SS, is the baseball or softball fielding position between second and third base, which is considered to be among the most demanding defensive positions. Historically the position was assigned to defensive specialists wh ...

. Risberg was Gandil's assistant and the "muscle" of the playing group. He went 2-for-25 at the plate and committed four errors in the series.

* George "Buck" Weaver, third baseman. Weaver attended the initial meetings, and while he did not go in on the fix, he knew about it. In an interview in 1956, Gandil said that it was Weaver's idea to get the money up front from the gamblers. Landis banished him on this basis, stating, "Men associating with crooks and gamblers could expect no leniency." On January 13, 1922, Weaver unsuccessfully applied for reinstatement. Like Jackson, Weaver continued to profess his innocence to successive baseball commissioners to no effect.

* Claude "Lefty" Williams, pitcher. Went 0–3 with a 6.63 ERA

An era is a span of time defined for the purposes of chronology or historiography, as in the regnal eras in the history of a given monarchy, a calendar era used for a given calendar, or the geological eras defined for the history of Earth.

Comp ...

for the series. Only one other pitcher in baseball history, reliever George Frazier

George Francis Frazier Jr. (June 10, 1911 – June 13, 1974) was an American journalist. Frazier was raised in South Boston, attended the Boston Latin School, and was graduated from Harvard College (where he won the Boylston Prize for Rhetoric) in ...

of the 1981

Events January

* January 1

** Greece enters the European Economic Community, predecessor of the European Union.

** Palau becomes a self-governing territory.

* January 10 – Salvadoran Civil War: The FMLN launches its first major offensiv ...

New York Yankees

The New York Yankees are an American professional baseball team based in the New York City borough of the Bronx. The Yankees compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) East division. They are one of ...

, has ever lost three games in one World Series. The third game Williams lost was Game 8 – baseball's decision to revert to a best of seven Series in 1922 significantly reduced the opportunity for a pitcher to obtain three decisions in a Series.

Also banned was Joe Gedeon

Elmer Joseph Gedeon (December 5, 1893 – May 19, 1941) was a second baseman in Major League Baseball. He played for the Washington Senators, New York Yankees, and St. Louis Browns.

Born in Sacramento, California, Gedeon started his profe ...

, second baseman for the St. Louis Browns

The St. Louis Browns were a Major League Baseball team that originated in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, as the Milwaukee Brewers. A charter member of the American League (AL), the Brewers moved to St. Louis, Missouri, after the 1901 season, where they p ...

. Gedeon placed bets since he learned of the fix from Risberg, a friend of his. He informed Comiskey of the fix after the Series in an effort to gain a reward. He was banned for life by Landis along with the eight White Sox, and died in 1941.

The indefinite suspensions imposed by Landis in relation to the scandal were the most suspensions of any duration to be simultaneously imposed until 2013 when 13 player suspensions of between 50 and 211 games were announced following the doping-related Biogenesis scandal.

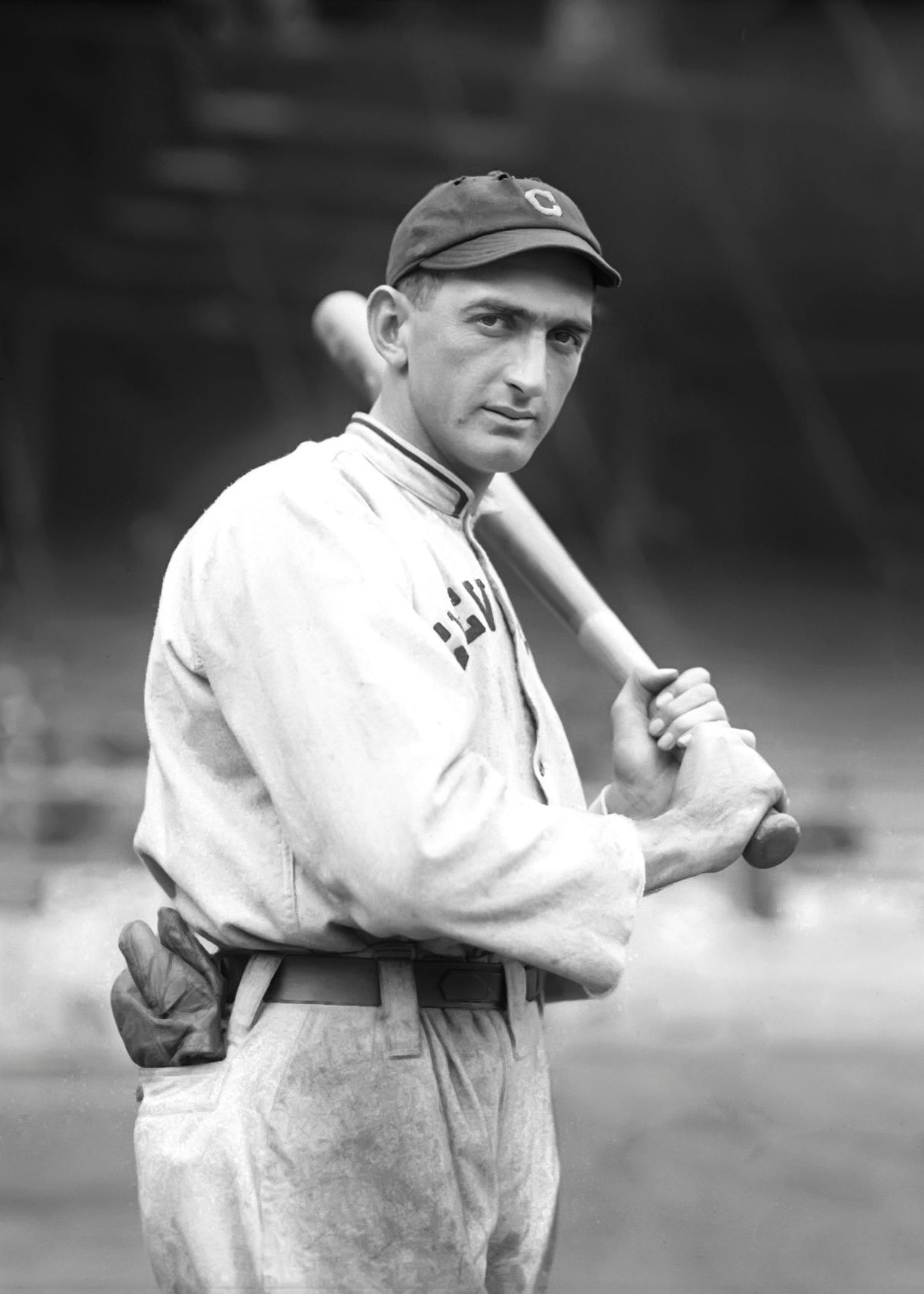

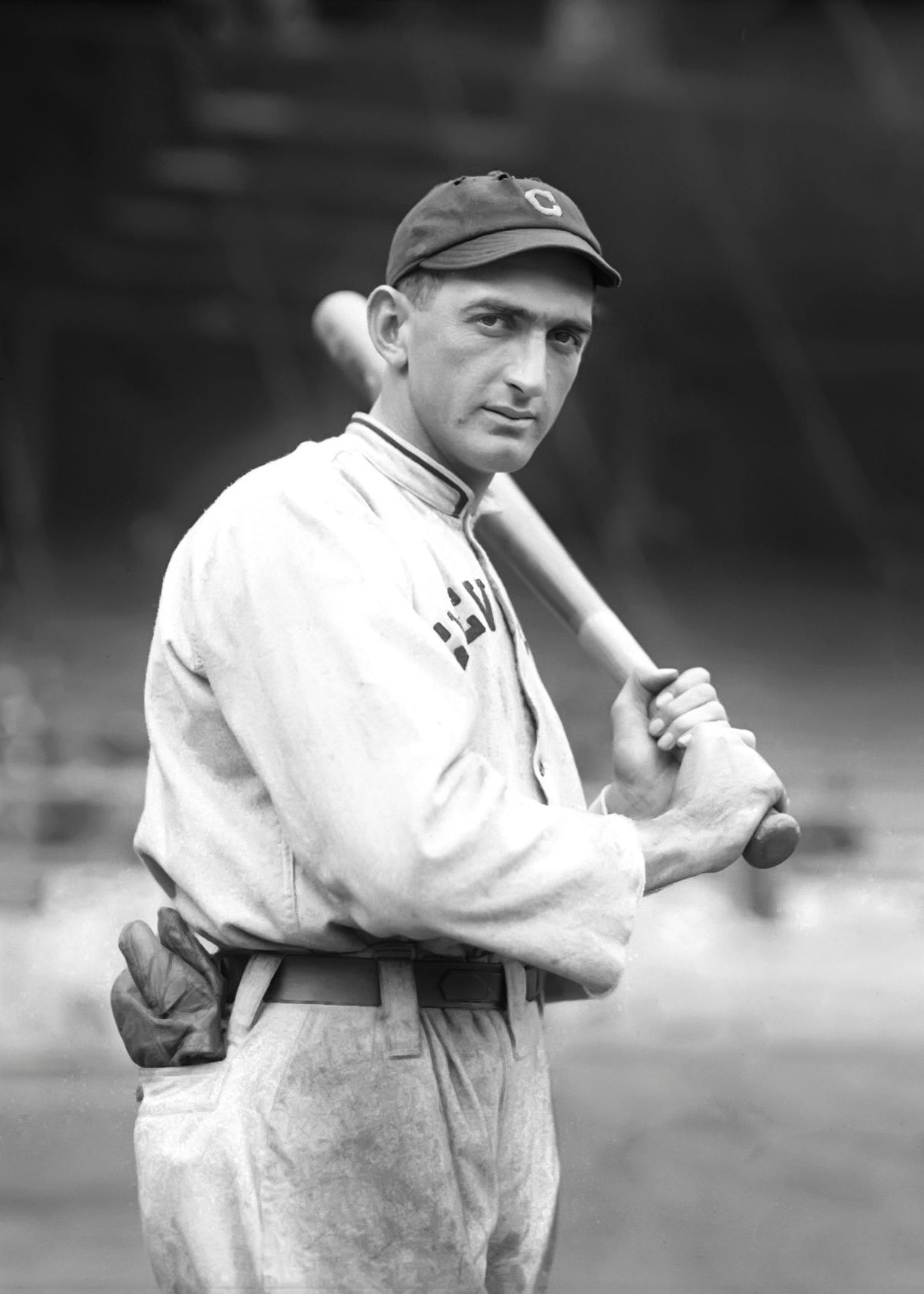

Joe Jackson

The extent of Joe Jackson's part in the big conspiracy remains controversial. Jackson maintained that he was innocent. He had a Series-leading .375

The extent of Joe Jackson's part in the big conspiracy remains controversial. Jackson maintained that he was innocent. He had a Series-leading .375 batting average

Batting average is a statistic in cricket, baseball, and softball that measures the performance of batters. The development of the baseball statistic was influenced by the cricket statistic.

Cricket

In cricket, a player's batting average is ...

—including the Series' only home run

In baseball, a home run (abbreviated HR) is scored when the ball is hit in such a way that the batter is able to circle the bases and reach home plate safely in one play without any errors being committed by the defensive team. A home run i ...

—threw out five baserunners, and handled 30 chances in the outfield with no errors. In general, players perform worse in games their team loses, and Jackson batted worse in the five games that the White Sox lost, with a batting average of .286 in those games. This was still an above-average batting average (the National and American Leagues hit a combined .263 in the 1919 season). Jackson hit .351 for the season, fourth-best in the major leagues (his .356 career batting average is the third-best in history, surpassed only by his contemporaries Ty Cobb

Tyrus Raymond Cobb (December 18, 1886 – July 17, 1961), nicknamed "the Georgia Peach", was an American Major League Baseball (MLB) center fielder. He was born in rural Narrows, Georgia. Cobb spent 22 seasons with the Detroit Tigers, the ...

and Rogers Hornsby

Rogers Hornsby Sr. (April 27, 1896 – January 5, 1963), nicknamed "The Rajah", was an American baseball infielder, manager, and coach who played 23 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB). He played for the St. Louis Cardinals (1915–1926, 193 ...

). Three of his six RBIs

A run batted in (RBI; plural RBIs ) is a statistic in baseball and softball that credits a batter for making a play that allows a run to be scored (except in certain situations such as when an error is made on the play). For example, if the bat ...

came in the losses, including the aforementioned home run, and a double in Game 8 when the Reds had a large lead and the series was all but over. Still, in that game a long foul ball was caught at the fence with runners on second and third, depriving Jackson of a chance to drive in the runners.

One play in particular has been subjected to scrutiny. In the fifth inning of Game 4, with a Cincinnati player on second, Jackson fielded a single hit to left field and threw home, which was cut off by Cicotte. Gandil, another leader of the fix, later admitted to yelling at Cicotte to intercept the throw. The run scored and the Sox lost the game, 2–0. Cicotte, whose guilt is undisputed, made two errors in that fifth inning alone.

Years later, all of the implicated players said that Jackson was never present at any of the meetings they had with the gamblers. Williams, Jackson's roommate, later said that they only brought up Jackson in hopes of giving them more credibility with the gamblers.

Aftermath

After being banned, Risberg and several other members of the Black Sox tried to organize a three-state barnstorming tour. However, they were forced to cancel those plans after Landis let it be known that anyone who played with or against them would also be banned from baseball for life. They then announced plans to play a regular exhibition game every Sunday in Chicago, but the Chicago City Council threatened to cancel the license of any ballpark that hosted them. With seven of their best players permanently sidelined, the White Sox crashed into seventh place in 1921 and would not be a factor in a pennant race again until 1936, five years after Comiskey's death. They would not win another American League championship until 1959 (a then-record 40-year gap) nor another World Series until , prompting some to comment about aCurse of the Black Sox

The Curse of the Black Sox (also known as the Curse of Shoeless Joe) (1919–2005) was a superstition or " scapegoat" cited as one reason for the failure of the Chicago White Sox to win the World Series from until . As with other supposed base ...

.

Name

Although many believe the Black Sox name to be related to the dark and corrupt nature of the conspiracy, the term "Black Sox" may already have existed before the fix. There is a story that the name "Black Sox" derived from Comiskey's refusal to pay for the players' uniforms to be laundered, instead insisting that the players themselves pay for the cleaning. As the story goes, the players refused and subsequent games saw the White Sox play in progressively filthier uniforms as dirt, sweat and grime collected on the white, woolen uniforms until they took on a much darker shade. Comiskey then had the uniforms washed and deducted the laundry bill from the players' salaries. On the other hand, Eliot Asinof in his book ''Eight Men Out'' makes no such connection, mentioning the filthy uniforms early on but referring to the term "Black Sox" only in connection with the scandal.Popular culture

Literature

*Eliot Asinof

Eliot Tager Asinof (July 13, 1919 – June 10, 2008) was an American writer of fiction and nonfiction best known for his writing about baseball. His most famous book was ''Eight Men Out'', a nonfiction reconstruction of the 1919 Black Sox scandal. ...

's book ''Eight Men Out: The Black Sox and the 1919 World Series'' is the best-known description of the scandal.

* Brendan Boyd's novel ''Blue Ruin: A Novel of the 1919 World Series'' offers a first-person narrative of the event from the perspective of Sport Sullivan, a Boston gambler involved in fixing the series.

* In F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age—a term he popularize ...

's novel ''The Great Gatsby

''The Great Gatsby'' is a 1925 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Set in the Jazz Age on Long Island, near New York City, the novel depicts first-person narrator Nick Carraway's interactions with mysterious millionaire Jay Gatsby ...

'', a minor character named Meyer Wolfsheim was said to have helped in the Black Sox scandal, though this is purely fictional. In explanatory notes accompanying the novel's 75th-anniversary edition, editor Matthew Bruccoli describes the character as being based on Arnold Rothstein

Arnold Rothstein (January 17, 1882 – November 4, 1928), nicknamed "The Brain", was an American racketeer, crime boss, businessman, and gambler in New York City. Rothstein was widely reputed to have organized corruption in professional athletic ...

.

* In Dan Gutman

Dan Gutman (born October 19, 1955) is an American writer, primarily of children's fiction.

His works include the '' Baseball Card Adventures'' children's book series that began with '' Honus & Me'', and the '' My Weird School'' series.

Early li ...

's novel '' Shoeless Joe & Me'' (2002), the protagonist, Joe, goes back in time to try to prevent Shoeless Joe from being banned for life.

* W. P. Kinsella's novel '' Shoeless Joe'' is the story of an Iowa farmer who builds a baseball field in his cornfield after hearing a mysterious voice. Later, Shoeless Joe Jackson and other members of the Black Sox come to play on his field. The novel was adapted into the 1989 hit film ''Field of Dreams

''Field of Dreams'' is a 1989 American sports fantasy drama film written and directed by Phil Alden Robinson, based on Canadian novelist W. P. Kinsella's 1982 novel ''Shoeless Joe''. The film stars Kevin Costner as a farmer who builds a ...

''. Joe Jackson plays a central role in inspiring protagonist Ray Kinsella to reconcile with his past.

* Bernard Malamud

Bernard Malamud (April 26, 1914 – March 18, 1986) was an American novelist and short story writer. Along with Saul Bellow, Joseph Heller, and Philip Roth, he was one of the best known American Jewish authors of the 20th century. His baseba ...

's 1952 novel ''The Natural

''The Natural'' is a 1952 novel about baseball by Bernard Malamud, and is his debut novel. The story follows Roy Hobbs, a baseball prodigy whose career is sidetracked after being shot by a woman whose motivation remains mysterious. The story mo ...

'' and its 1984 filmed dramatization of the same name were inspired significantly by the events of the scandal.

* Harry Stein's novel ''Hoopla'', alternately co-narrated by Buck Weaver

George Daniel "Buck" Weaver (August 18, 1890 – January 31, 1956) was an American shortstop and third baseman. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Chicago White Sox. Weaver played for the 1917 World Series champion White Sox, then ...

and Luther Pond, a fictitious ''New York Daily News'' columnist, attempts to view the Black Sox Scandal from Weaver's perspective.

* Dan Elish's book ''The Black Sox Scandal of 1919'' gives a general overview of the events.

* ''The Black Sox Scandal: The History And Legacy Of America's Most Notorious Sports Controversy'' by Charles River Editors talks about the events surrounding the scandal and gives a detailed description of the people involved.

* "Go! Go! Go! Forty Years Ago" Nelson Algren, Chicago Sun-Times,1959

* "Ballet for Opening Day: The Swede Was a Hard Guy" Algren, Nelson. The Southern Review, Baton Rouge. Spring 1942: p. 873.

* "The Last Carousel" © Nelson Algren, 1973, Seven Stories Press, New York 1997 (both Algren stories are included in this collection)

Film

* In the film ''The Godfather Part II

''The Godfather Part II'' is a 1974 American epic crime film produced and directed by Francis Ford Coppola. The film is partially based on the 1969 novel ''The Godfather'' by Mario Puzo, who co-wrote the screenplay with Coppola. ''Part II'' s ...

'' (1974), the fictional gangster Hyman Roth

Hyman Roth (born Hyman Suchowsky) is a fictional character and the main antagonist in the 1974 film '' The Godfather Part II''. He is also a minor character in the 2004 novel ''The Godfather Returns''. Roth is a Jewish mobster, investor and a bu ...

alludes to the scandal when he says, "I've loved baseball ever since Arnold Rothstein

Arnold Rothstein (January 17, 1882 – November 4, 1928), nicknamed "The Brain", was an American racketeer, crime boss, businessman, and gambler in New York City. Rothstein was widely reputed to have organized corruption in professional athletic ...

fixed the World Series in 1919".

* Director John Sayles

John Thomas Sayles (born September 28, 1950) is an American independent film director, screenwriter, editor, actor, and novelist. He has twice been nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, for ''Passion Fish'' (1992) and '' ...

' ''Eight Men Out

''Eight Men Out'' is a 1988 American sports drama film based on Eliot Asinof's 1963 book ''Eight Men Out: The Black Sox and the 1919 World Series''. It was written and directed by John Sayles. The film is a dramatization of Major League Baseball' ...

'', a 1988 film based on Asinof's book, is a dramatization of the scandal, focusing largely on Buck Weaver (played by John Cusack

John Paul Cusack (; born June 28, 1966)(28 June 1996)Today's birthdays ''Santa Cruz Sentinel'', ("Actors John Cusack is 30") is an American actor, producer, screenwriter and political activist. He is a son of filmmaker Dick Cusack, and his ol ...

) as the one banned player who did not take any money. Also starring in the film were Charlie Sheen

Carlos Irwin Estévez (born September 3, 1965), known professionally as Charlie Sheen, is an American actor. He has appeared in films such as ''Platoon'' (1986), ''Wall Street'' (1987), '' Young Guns'' (1988), '' The Rookie'' (1990), ''The Thr ...

(Hap Felsch), Michael Rooker

Michael Rooker (born April 6, 1955) is an American actor known for his roles as Henry in '' Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer'' (1986), Chick Gandil in ''Eight Men Out'' (1988), Frank Baily in '' Mississippi Burning'' (1988), Terry Cruger in '' ...

(Chick Gandil), David Strathairn

David Russell Strathairn (; born January 26, 1949) is an American actor. Known for his leading roles on stage and screen, he has often portrayed historical figures such as Edward R. Murrow, J. Robert Oppenheimer, William H. Seward, and John Do ...

(Eddie Cicotte), John Mahoney

Charles John Mahoney (June 20, 1940 – February 4, 2018) was an English-born American actor. He was known for playing Martin Crane on the NBC sitcom ''Frasier'' (1993–2004), and won a Screen Actors Guild Award for the role in 2000. Mahone ...

(Kid Gleason), Christopher Lloyd

Christopher Allen Lloyd (born October 22, 1938) is an American actor. He has appeared in many theater productions, films, and on television since the 1960s. He is known for portraying Dr. Emmett "Doc" Brown in the ''Back to the Future'' tril ...

("Sleepy" Bill Burns), Clifton James

George Clifton James (May 29, 1920 – April 15, 2017) was an American actor known for roles as a prison floorwalker in ''Cool Hand Luke'' (1967), Sheriff J.W. Pepper alongside Roger Moore in the James Bond films '' Live and Let Die'' (19 ...

(Charles Comiskey) and D. B. Sweeney (Shoeless Joe Jackson). Sayles himself portrayed sports writer Ring Lardner

Ringgold Wilmer Lardner (March 6, 1885 – September 25, 1933) was an American sports columnist and short story writer best known for his satirical writings on sports, marriage, and the theatre. His contemporaries Ernest Hemingway, Virginia Wo ...

.

* The 1989 film ''Field of Dreams

''Field of Dreams'' is a 1989 American sports fantasy drama film written and directed by Phil Alden Robinson, based on Canadian novelist W. P. Kinsella's 1982 novel ''Shoeless Joe''. The film stars Kevin Costner as a farmer who builds a ...

'', based upon the novel by W. P. Kinsella, discussed the scandal and featured two of the players involved, Joe Jackson (Ray Liotta

Raymond Allen Liotta (; December 18, 1954 – May 26, 2022) was an American actor. He was best known for his roles as Shoeless Joe Jackson in ''Field of Dreams'' (1989) and Henry Hill in Martin Scorsese's ''Goodfellas'' (1990). He was a Primet ...

) who played a large part in the film and Eddie Cicotte ( Steve Eastin). ''Field of Dreams'' starred Kevin Costner

Kevin Michael Costner (born January 18, 1955) is an American actor, producer, film director and musician. He has received various accolades, including two Academy Awards, two Golden Globe Awards, a Primetime Emmy Award, and two Screen Actor ...

, Amy Madigan

Amy Marie Madigan (born September 11, 1950) is an American actress. She was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for the 1985 film '' Twice in a Lifetime''. Her other film credits include '' Love Child'' (1982), ''Places ...

and James Earl Jones

James Earl Jones (born January 17, 1931) is an American actor. He has been described as "one of America's most distinguished and versatile" actors for his performances in film, television, and theater, and "one of the greatest actors in America ...

.

* The 2013 film ''The Great Gatsby

''The Great Gatsby'' is a 1925 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Set in the Jazz Age on Long Island, near New York City, the novel depicts first-person narrator Nick Carraway's interactions with mysterious millionaire Jay Gatsby ...

'', based on the novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age—a term he popularize ...

, speaks of the man who fixed the 1919 World Series.

Television

* In the first season of '' Boardwalk Empire'' and the second season, the scandal is a large subplot involvingArnold Rothstein

Arnold Rothstein (January 17, 1882 – November 4, 1928), nicknamed "The Brain", was an American racketeer, crime boss, businessman, and gambler in New York City. Rothstein was widely reputed to have organized corruption in professional athletic ...

, Lucky Luciano and their associates.

* In fifth season of ''Mad Men

''Mad Men'' is an American period drama television series created by Matthew Weiner and produced by Lionsgate Television. It ran on the cable network AMC from July 19, 2007, to May 17, 2015, lasting for seven seasons and 92 episodes. Its f ...

'', Roger Sterling

Roger H. Sterling Jr. is a fictional character on the AMC television series '' Mad Men''. He formerly worked for Sterling Cooper, an advertising agency his father co-founded in 1923, before he became a founding partner at the new firm of Sterling ...

tries Lysergic acid diethylamide

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), also known colloquially as acid, is a potent psychedelic drug. Effects typically include intensified thoughts, emotions, and sensory perception. At sufficiently high dosages LSD manifests primarily mental, vi ...

(LSD) for the first time and hallucinates that he is at the infamous game.

* In the second season of ''Frankie Drake Mysteries

''Frankie Drake Mysteries'' is a Canadian drama that ran on CBC from November 6, 2017 to March 8, 2021. The series starred Lauren Lee Smith and Chantel Riley as Frankie Drake and her partner Trudy who ran an all female private detective servic ...

'', morality officer Mary Shaw mentions the scandal while helping Frankie investigate the murder of a player with circumstances related to gambling.

* The story of the scandal was retold by Katie Nolan

Katherine Beth Nolan is an American sports television host known as Katie Nolan, most recently serving as a commentator for Apple TV+'s ''Friday Night Baseball'' and recently created short-form content at NBC Sports. She formerly hosted a weekly ...

in the sixth season of '' Drunk History''.

* In episode 10, Rookie of the Year (Screen Directors Playhouse), Ward Bond plays a fictional character based on Shoeless Joe Jackson

Joseph Jefferson Jackson (July 16, 1887 – December 5, 1951), nicknamed "Shoeless Joe", was an American outfielder who played Major League Baseball (MLB) in the early 1900s. Although his .356 career batting average is the fourth highest ...

, one of the ball players banned for life from Major League Baseball

Major League Baseball (MLB) is a professional baseball organization and the oldest major professional sports league in the world. MLB is composed of 30 total teams, divided equally between the National League (NL) and the American League (AL), ...

because of his participation in the 1919 World Series

The 1919 World Series was the championship series in Major League Baseball for the 1919 season. The 16th edition of the World Series, it matched the American League champion Chicago White Sox against the National League champion Cincinnati Reds. ...

scandal.

Music

*Murray Head

Murray Seafield St George Head (born 5 March 1946) is an English actor and singer. Head has appeared in a number of films, including a starring role as the character Bob Elkin in the Oscar-nominated 1971 film ''Sunday Bloody Sunday''. As a mus ...

's 1975 album'' Say It Ain't So

"Say It Ain't So" is a song by the American rock band Weezer. It was released as the third and final single from the band's self-titled 1994 debut album.

Written by frontman Rivers Cuomo, the song came to be after he had all the music finishe ...

'' takes its name after an apocryphal question put to Shoeless Joe Jackson during the court case.

* On Jonathan Coulton

Jonathan William Coulton (born December 1, 1970), often called "JoCo" by fans, is an American folk/comedy singer-songwriter, known for his songs about geek culture and his use of the Internet to draw fans. Among his most popular songs are " Co ...

's album '' Smoking Monkey'', his song "Kenesaw Mountain Landis" greatly fictionalizes the commissioner's quest to ban Jackson from baseball, in the style of a tall tale

A tall tale is a story with unbelievable elements, related as if it were true and factual. Some tall tales are exaggerations of actual events, for example fish stories ("the fish that got away") such as, "That fish was so big, why I tell ya', it n ...

.

Theatre

* ''1919: A Baseball Opera,'' is a musical by Composer/lyricist Rusty Magee and Rob Barron, which premiered in June of 1981 atYale Repertory Theatre

Yale Repertory Theatre at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut was founded by Robert Brustein, dean of Yale School of Drama, in 1966, with the goal of facilitating a meaningful collaboration between theatre professionals and talented stude ...

.

* '' The Fix'' is an opera by composer Joel Puckett

Joel Puckett (born in 1977 in Atlanta, Georgia) is an American composer. He comes from a musical family; his father was a classical tubist and in his retirement still plays dixie-land jazz gigs around Atlanta. Joel completed his academic work at ...

with libretto by Eric Simonson

Eric Simonson (born June 27, 1960 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin) is an American writer and director in theatre, film and opera. He is a member of Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago, and the author of plays '' Lombardi'', ''Fake'', ''Honest'', '' Magic/B ...

, which premiered March 16, 2019 at the Ordway Center for the Performing Arts

The Ordway Center for the Performing Arts, in downtown Saint Paul, Minnesota, hosts a variety of performing arts, such as touring Broadway musicals, orchestra, opera, and cultural performers, and produces local musicals. It is home to several lo ...

.

"Say it ain't so, Joe"

After the grand jury returned its indictments, Charley Owens of the ''Chicago Daily News'' wrote a regretful tribute directed at Jackson headlined, "Say it ain't so, Joe". The phrase became legend when another reporter later erroneously attributed it to a child outside the courthouse:When Jackson left the criminal court building in the custody of a sheriff after telling his story to the grand jury, he found several hundred youngsters, aged from 6 to 16, waiting for a glimpse of their idol. One child stepped up to the outfielder, and, grabbing his coat sleeve, said:In an interview in ''

"It ain't true, is it, Joe?"

"Yes, kid, I'm afraid it is", Jackson replied. The boys opened a path for the ball player and stood in silence until he passed out of sight.

"Well, I'd never have thought it," sighed the lad.

Sport

Sport pertains to any form of competitive physical activity or game that aims to use, maintain, or improve physical ability and skills while providing enjoyment to participants and, in some cases, entertainment to spectators. Sports can, ...

'' nearly three decades later, Jackson confirmed that the legendary exchange never occurred.

See also

*Major League Baseball scandals

There have been many dramatic on-and-off-field moments in over 130 years of Major League Baseball:

Gambling scandals

Baseball had frequent problems with gamblers influencing the game, until the 1920s when the Black Sox Scandal and the resultant me ...

* Houston Astros sign stealing scandal

The Houston Astros sign stealing scandal resulted from a series of rule violations by members of the Houston Astros of Major League Baseball (MLB), who used technology to steal signs of opposing teams during the 2017 and 2018 seasons.

For yea ...

References

Sources

Chicago Historical Society: Black Sox

SABR Digital Library: Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox

* Asinof, Eliot. ''Eight Men Out''. New York: Henry Holt, 1963. * Carney, Gene. ''Burying the Black Sox''. Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, 2007. * Ginsburg, Daniel E. ''The Fix Is In: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals''. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1995. * Gropman, Donald. ''Say It Ain't So, Joe!: The Story of Shoeless Joe Jackson''. Boston: Little, Brown, 1979. * Pietrusza, David ''Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis'' South Bend, IN: Diamond Communications, 1998. * Pietrusza, David ''Rothstein: The Life, Times, and Murder of the Criminal Genius Who Fixed the 1919 World Series''. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2003.

Further reading

* Fountain, Charles. ''The Betrayal: The 1919 World Series and the Birth of Modern Baseball''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015. * Hornbaker, Tim. ''Fall from Grace: The Truth and Tragedy of "Shoeless Joe" Jackson. Sports Publishing, 2016. * Hornbaker, Tim. ''Turning the Black Sox White: The Misunderstood Legacy of Charles A. Comiskey''. Sports Publishing, 2014. * Zminda, Don. ''Double Plays and Double Crosses: The Black Sox and Baseball in 1920''. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021.External links

Chicagohs.org

Chicago Historical Society on the Black Sox

''Eight Men Out''

– IMDb page on the 1988 movie, written and directed by

John Sayles

John Thomas Sayles (born September 28, 1950) is an American independent film director, screenwriter, editor, actor, and novelist. He has twice been nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, for ''Passion Fish'' (1992) and '' ...

based on Asinof's book

baseball-reference.com

box scores and info on each game {{Sports Corruption Scandals

World Series

The World Series is the annual championship series of Major League Baseball (MLB) in the United States and Canada, contested since 1903 between the champion teams of the American League (AL) and the National League (NL). The winner of the World ...

Chicago White Sox postseason

Cincinnati Reds postseason

Criminal trials that ended in acquittal

History of baseball in the United States

20th-century American trials

Major League Baseball controversies

Sports betting scandals

World Series games

Match fixing

Arnold Rothstein