Black Mountains (North Carolina) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Black Mountains are a

The forests of the Black Mountains are typically divided into three zones based on altitude: the spruce-fir forest, the northern hardwoods, and the Appalachian hardwoods. The

The forests of the Black Mountains are typically divided into three zones based on altitude: the spruce-fir forest, the northern hardwoods, and the Appalachian hardwoods. The

Mitchell returned to the Blacks in 1838 and 1844, gaining a higher measurement on each trip. Several surveyors visited the Blacks in subsequent years, including Nehemiah Blackstock (1794–1880) in 1845,

Mitchell returned to the Blacks in 1838 and 1844, gaining a higher measurement on each trip. Several surveyors visited the Blacks in subsequent years, including Nehemiah Blackstock (1794–1880) in 1845,

The revelation that the Black Mountains were the highest in the Appalachian Range made them an immediate tourist attraction. By the 1850s, a lodge had been established in the southern part of the range, and locals such as Jesse Stepp and Tom Wilson had built several rustic cabins on the higher mountain slopes and were thriving as mountain guides. The

The revelation that the Black Mountains were the highest in the Appalachian Range made them an immediate tourist attraction. By the 1850s, a lodge had been established in the southern part of the range, and locals such as Jesse Stepp and Tom Wilson had built several rustic cabins on the higher mountain slopes and were thriving as mountain guides. The

Image:Big-tom-summit-nc1.jpg, The summit of Big Tom

Image:Balsam-cone-toe-valley-nc1.jpg, The South Toe Valley, viewed from the summit of Balsam Cone

Image:Black-mountains-deep-gap-nc1.jpg, Backcountry campsite at Deep Gap

Image:Cattail-peak-summit-nc1.jpg, Sign marking the summit of Cattail Peak

South Beyond 6000 in the Black Mountains

– Site provided by the Carolina Mountain Club {{Authority control Blue Ridge Mountains Mountains, Black Subranges of the Appalachian Mountains Mountains of Yancey County, North Carolina Mountains of Buncombe County, North Carolina

mountain range

A mountain range or hill range is a series of mountains or hills arranged in a line and connected by high ground. A mountain system or mountain belt is a group of mountain ranges with similarity in form, structure, and alignment that have arise ...

in western North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, in the southeastern United States. They are part of the Blue Ridge Province of the Southern Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

. The Black Mountains are the highest mountains in the Eastern United States. The range takes its name from the dark appearance of the red spruce

''Picea rubens'', commonly known as red spruce, is a species of spruce native to eastern North America, ranging from eastern Quebec and Nova Scotia, west to the Adirondack Mountains and south through New England along the Appalachians to western ...

and Fraser fir

The Fraser fir (''Abies fraseri'') is a species of fir native to the Appalachian Mountains of the Southeastern United States.

''Abies fraseri'' is closely related to ''Abies balsamea'' (balsam fir), of which it has occasionally been treated a ...

trees that form a spruce-fir forest on the upper slopes which contrasts with the brown (during winter) or lighter green (during the growing season) appearance of the deciduous trees

In the fields of horticulture and Botany, the term ''deciduous'' () means "falling off at maturity" and "tending to fall off", in reference to trees and shrubs that seasonally shed leaves, usually in the autumn; to the shedding of petals, aft ...

at lower elevations. The Eastern Continental Divide, which runs along the eastern Blue Ridge crest, intersects the southern tip of the Black Mountain range.

The Black Mountains are home to Mount Mitchell State Park

Mount Mitchell State Park is a North Carolina state park in Yancey County, North Carolina in the United States. Established in 1915 by the state legislature, it became the first state park of North Carolina. By doing so, it also established the ...

, which protects the range's highest summit and adjacent summits in the north-central section of the range. Much of the range is also protected by the Pisgah National Forest

Pisgah National Forest is a National Forest in the Appalachian Mountains of western North Carolina. It is administered by the United States Forest Service, part of the United States Department of Agriculture. The Pisgah National Forest is complet ...

. The Blue Ridge Parkway

The Blue Ridge Parkway is a National Parkway and All-American Road in the United States, noted for its scenic beauty. The parkway, which is America's longest linear park, runs for through 29 Virginia and North Carolina counties, linking Shenand ...

passes along the range's southern section, and is connected to the summit of Mount Mitchell by North Carolina Highway 128. The Black Mountains are mostly located in Yancey County

Yancey County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population was 18,470. Its county seat is Burnsville.

This land was inhabited by the Cherokee prior to European settlement, as was much of the S ...

, although the range's southern and western extremes are part of Buncombe County

Buncombe County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. It is classified within Western North Carolina. The 2020 census reported the population was 269,452. Its county seat is Asheville. Buncombe County is part of the Ashevill ...

.

Geography

The Black Mountains form a J-shaped semicircle that opens to the northwest. The Blacks rise southward from the Little Crabtree Creek Valley in the north to the steep summit of Celo Knob. A few miles south of Celo, the crest drops to at Deep Gap before rising steeply again to the summit of Potato Hill in the north-central section of the range. The crest continues southward across the north-central section, which contains 6 of the 10 highest summits in the eastern United States, including the highest, Mount Mitchell, and the second-highest, Mount Craig. South of Mount Mitchell, the crest drops to just under at Stepp's Gap before rising again to at the summit of Mount Gibbes. On the slopes of Potato Knob, just south of Clingmans Peak, the Black Mountain crest bends northwestward across Blackstock Knob before dropping again to at Balsam Gap, where it intersects theGreat Craggy Mountains

The Great Craggy Mountains, commonly called the Craggies, are a mountain range in western North Carolina, United States. They are a subrange of the Blue Ridge Mountains and encompass an area of approx. 194 sq mi (503 km²). They are situated ...

to the southwest. The crest then turns northward across Point Misery

Point or points may refer to:

Places

* Point, Lewis, a peninsula in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland

* Point, Texas, a city in Rains County, Texas, United States

* Point, the NE tip and a ferry terminal of Lismore, Inner Hebrides, Scotland

* Poin ...

and Big Butt

Big or BIG may refer to:

* Big, of great size or degree

Film and television

* ''Big'' (film), a 1988 fantasy-comedy film starring Tom Hanks

* '' Big!'', a Discovery Channel television show

* ''Richard Hammond's Big'', a television show present ...

before descending to the Cane River

Cane River (''Rivière aux Cannes'') is a riverU.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 3, 2011 formed from a portion of the Red River that is located in Natchitoches Pa ...

Valley.

The northern section of the Black Mountains are drained by the Cane River

Cane River (''Rivière aux Cannes'') is a riverU.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 3, 2011 formed from a portion of the Red River that is located in Natchitoches Pa ...

to the west and the South Toe River

The South Toe River is a river in Yancey County in Western North Carolina. The name Toe is taken from its original name Estatoe, pronounced 'S - ta - toe', a native American name associated with the Estatoe trade route leading down from the NC m ...

to the east, both of which are part of the upper Nolichucky River

The Nolichucky River is a river that flows through Western North Carolina and East Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. Traversing the Pisgah National Forest and the Cherokee National Forest in the Blue Ridge Mountains, the river's wate ...

watershed. The southwestern part of the range is drained by the upper French Broad River

The French Broad River is a river in the U.S. states of North Carolina and Tennessee. It flows from near the town of Rosman in Transylvania County, North Carolina, into Tennessee, where its confluence with the Holston River at Knoxville forms ...

which, like the Nolichucky, is west of the Eastern Continental Divide and thus its waters eventually wind up in the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

. The southern face of the hook drains into Flat Creek and the north fork of the Swannanoa River

The Swannanoa River flows through the Swannanoa Valley of the region of Western North Carolina, and is a major tributary to the French Broad River. Its headwaters arise in Black Mountain, NC; however, it also has a major tributary near its head ...

which also heads to the French Broad River. The North Fork Reservoir, supplied with the ample rain caused by moisture pushing up the southern face, serves as the primary water source for the Asheville

Asheville ( ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Buncombe County, North Carolina. Located at the confluence of the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers, it is the largest city in Western North Carolina, and the state's 11th-most populous cit ...

region. A few of the streams in the southeastern section of the range are part of the Catawba River

The Catawba River originates in Western North Carolina and flows into South Carolina, where it later becomes known as the Wateree River. The river is approximately 220 miles (350 km) long. It rises in the Appalachian Mountains and drains into ...

watershed, and are thus east of the Eastern Continental Divide.

Notable summits

While the crest of the Black Mountain range is just long, within these fifteen miles are 18 peaks climbing to at least 6300 feet (1900 meters) abovesea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised g ...

. The Black Mountains rise prominently above the surrounding lower terrain. This is particularly noticeable from the range's eastern side, which rises over 4500 feet (1375 meters) above the Catawba River Valley and Interstate 40

Interstate 40 (I-40) is a major east–west Interstate Highway running through the south-central portion of the United States. At a length of , it is the third-longest Interstate Highway in the country, after I-90 and I-80. From west to ea ...

, providing some impressive mountain scenery.

Geology

The Black Mountains consist primarily ofPrecambrian

The Precambrian (or Pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pꞒ, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of the ...

gneiss

Gneiss ( ) is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. It is formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Gneiss forms at higher temperatures an ...

and schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes o ...

s formed over a billion years ago from primordial sea sediments. The mountains themselves were formed roughly 200–400 million years ago during the Alleghenian orogeny

The Alleghanian orogeny or Appalachian orogeny is one of the geological mountain-forming events that formed the Appalachian Mountains and Allegheny Mountains. The term and spelling Alleghany orogeny was originally proposed by H.P. Woodward in 195 ...

, when the collision of two continental plates thrust what is now the Appalachian Mountains upward to form a large plateau. Weathering and minor geologic events in subsequent periods carved out the mountains.

During the last ice age, approximately 20,000–16,000 years ago, glaciers did not advance into Southern Appalachia, but the change in temperatures drastically changed the forests in the region. A tree-less tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless moun ...

likely existed in the Black Mountains and surrounding mountains in elevations above . Spruce-fir forests dominated the lower elevations during this period, while hardwoods "fled" to warmer refuges in the coastal plains. As the ice sheets began retreating 16,000 years ago and temperatures started to rise, the hardwoods returned to the river valleys and lower slopes, and the spruce-fir forest retreated to the higher elevations. Today, the spruce-fir forest atop the Black Mountains is one of ten or so spruce-fir "islands" remaining in the mountains of Southern Appalachia.

Plants and wildlife

The forests of the Black Mountains are typically divided into three zones based on altitude: the spruce-fir forest, the northern hardwoods, and the Appalachian hardwoods. The

The forests of the Black Mountains are typically divided into three zones based on altitude: the spruce-fir forest, the northern hardwoods, and the Appalachian hardwoods. The southern Appalachian spruce-fir forest

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, ...

, though sometimes referred to as "boreal" or "Canadian," is a unique plant community endemic to a few high peaks of the Southern Appalachians. In fact, it is more akin to a high elevation cloud forest

A cloud forest, also called a water forest, primas forest, or tropical montane cloud forest (TMCF), is a generally tropical or subtropical, evergreen, montane, moist forest characterized by a persistent, frequent or seasonal low-level cloud c ...

. It is dominated by red spruce and Fraser fir, and coats the elevations above . The northern hardwoods, which consist primarily of beech

Beech (''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to temperate Europe, Asia, and North America. Recent classifications recognize 10 to 13 species in two distinct subgenera, ''Engleriana'' and ''Fagus''. The ''Engle ...

, yellow birch

''Betula alleghaniensis'', the yellow birch, golden birch, or swamp birch, is a large tree and an important lumber species of birch native to northeastern North America. Its vernacular names refer to the golden color of the tree's bark. In the pa ...

, and buckeye, thrive between and . The more diverse Appalachian hardwoods, which include yellow poplar

''Liriodendron tulipifera''—known as the tulip tree, American tulip tree, tulipwood, tuliptree, tulip poplar, whitewood, fiddletree, and yellow-poplar—is the North American representative of the two-species genus ''Liriodendron'' (the other ...

and various species of hickory

Hickory is a common name for trees composing the genus ''Carya'', which includes around 18 species. Five or six species are native to China, Indochina, and India (Assam), as many as twelve are native to the United States, four are found in Mexi ...

, oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' (; Latin "oak tree") of the beech family, Fagaceae. There are approximately 500 extant species of oaks. The common name "oak" also appears in the names of species in related genera, notably ''L ...

, and maple

''Acer'' () is a genus of trees and shrubs commonly known as maples. The genus is placed in the family Sapindaceae.Stevens, P. F. (2001 onwards). Angiosperm Phylogeny Website. Version 9, June 2008 nd more or less continuously updated since http ...

, dominate the slopes and stream valleys below . Pine forests, consisting chiefly of Table Mountain pine, pitch pine, and Virginia pine

''Pinus virginiana'', the Virginia pine, scrub pine, Jersey pine, Possum pine, is a medium-sized tree, often found on poorer soils from Long Island in southern New York south through the Appalachian Mountains to western Tennessee and Alabama. T ...

, are found on the drier south-facing slopes. mountain paper birch, which is rare in North Carolina, grows sporadically on the slopes of Mount Mitchell.

Wildlife in the Black Mountains is typical of the Appalachian highlands. Mammals include black bear

Black bear or Blackbear may refer to:

Animals

* American black bear (''Ursus americanus''), a North American bear species

* Asian black bear (''Ursus thibetanus''), an Asian bear species

Music

* Black Bear (band), a Canadian First Nations group ...

s, white-tailed deer

The white-tailed deer (''Odocoileus virginianus''), also known as the whitetail or Virginia deer, is a medium-sized deer native to North America, Central America, and South America as far south as Peru and Bolivia. It has also been introduced t ...

, raccoon

The raccoon ( or , ''Procyon lotor''), sometimes called the common raccoon to distinguish it from other species, is a mammal native to North America. It is the largest of the procyonid family, having a body length of , and a body weight of ...

s, river otters, mink

Mink are dark-colored, semiaquatic, carnivorous mammals of the genera ''Neogale'' and '' Mustela'' and part of the family Mustelidae, which also includes weasels, otters, and ferrets. There are two extant species referred to as "mink": the A ...

s, bobcat

The bobcat (''Lynx rufus''), also known as the red lynx, is a medium-sized cat native to North America. It ranges from southern Canada through most of the contiguous United States to Oaxaca in Mexico. It is listed as Least Concern on the IUC ...

s, and the endangered northern flying squirrel

The northern flying squirrel (''Glaucomys sabrinus'') is one of three species of the genus '' Glaucomys'', the only flying squirrels found in North America.Walker EP, Paradiso JL. 1975. ''Mammals of the World''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Universi ...

. Bird species include the wild turkey

The wild turkey (''Meleagris gallopavo'') is an Upland game bird, upland ground bird native to North America, one of two extant species of Turkey (bird), turkey and the heaviest member of the order Galliformes. It is the ancestor to the domestic ...

, the northern saw-whet owl

The northern saw-whet owl (''Aegolius acadicus'') is a species of small owl in the family Strigidae. The species is native to North America. Saw-whet owls of the genus ''Aegolius'' are some of the smallest owl species in North America. They can ...

, and the pileated woodpecker

The pileated woodpecker (''Dryocopus pileatus'') is a large, mostly black woodpecker native to North America. An insectivore, it inhabits deciduous forests in eastern North America, the Great Lakes, the boreal forests of Canada, and parts of the ...

, although peregrine falcon

The peregrine falcon (''Falco peregrinus''), also known as the peregrine, and historically as the duck hawk in North America, is a Cosmopolitan distribution, cosmopolitan bird of prey (Bird of prey, raptor) in the family (biology), family Falco ...

s and various species of hawk

Hawks are bird of prey, birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. They are widely distributed and are found on all continents except Antarctica.

* The subfamily Accipitrinae includes goshawks, sparrowhawks, sharp-shinned hawks and others. Th ...

are known to nest in the upper elevations. Brook trout

The brook trout (''Salvelinus fontinalis'') is a species of freshwater fish in the char genus ''Salvelinus'' of the salmon family Salmonidae. It is native to Eastern North America in the United States and Canada, but has been introduced elsewhere ...

, which are more typical of northern latitudes, are found in the streams at the base of the Black Mountains.

History

Prehistory

Native Americans have likely been hunting in the Black Mountains for thousands of years. At Swannanoa Gap, just south of the range, archaeologists have uncovered evidence of habitation dating to the Archaic period (8000–1000 BC), theWoodland period

In the classification of :category:Archaeological cultures of North America, archaeological cultures of North America, the Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures spanned a period from roughly 1000 Common Era, BCE to European con ...

(1000 BC – 1000 AD), and the Mississippian period (c. 900-1600 AD). The Mississippian-period village of Joara

Joara was a large Native American settlement, a regional chiefdom of the Mississippian culture, located in what is now Burke County, North Carolina, about 300 miles from the Atlantic coast in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Joara is n ...

was located near the town of Morganton to the southeast.

The Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

expedition, which was attempting to travel from the Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

coast to the Pacific Ocean, is believed to have passed through the North Toe River valley in May 1540, and thus would have included the first Europeans to see the Black Mountains. An expedition led by Juan Pardo probably crossed the Blue Ridge at Swannanoa Gap in October 1567. Both expeditions spent considerable time at Joara.

Early settlement

For much of the 18th century, the Black Mountains were a hunting ground on the eastern fringe of Cherokee territory. By 1785, however, the Cherokee had signed away ownership of the Black Mountains to the United States, and Euro-American settlers moved into the Cane and South Toe valleys shortly thereafter. The early settlers farmed the river valleys and sold animal furs,ginseng

Ginseng () is the root of plants in the genus ''Panax'', such as Korean ginseng ('' P. ginseng''), South China ginseng ('' P. notoginseng''), and American ginseng ('' P. quinquefolius''), typically characterized by the presence of ginsenosides an ...

, tobacco, liquor, and excess crops at markets in nearby Asheville. The early farmers also brought large herds of cattle and hogs, which thrived in the valleys and mountain areas.

In 1789, French botanist André Michaux

André Michaux, also styled Andrew Michaud, (8 March 174611 October 1802) was a French botanist and explorer. He is most noted for his study of North American flora. In addition Michaux collected specimens in England, Spain, France, and even Per ...

, who had been sent to America by the King of France to collect exotic plant specimens, made his first excursion into the Southern Appalachian Mountains, which included a brief trip to the Blacks. Michaux returned to the Blacks in August 1794, and collected several plant specimens that thrive above . Michaux's findings, published in the early 19th century, were among the first to bring attention to the diversity and significance of the plants of Southern Appalachia.

Elisha Mitchell and Thomas Lanier Clingman

In the early 19th century,Mount Washington

Mount Washington is the highest peak in the Northeastern United States at and the most topographically prominent mountain east of the Mississippi River.

The mountain is notorious for its erratic weather. On the afternoon of April 12, 1934 ...

in New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

was believed to be the highest summit in the Eastern United States, an assumption many North Carolinians began to question in light of Michaux's findings (Michaux believed that Grandfather Mountain

Grandfather Mountain is a mountain, a non-profit attraction, and a North Carolina state park

near Linville, North Carolina. At 5,946 feet (1,812 m), it is the highest peak on the eastern escarpment of the Blue Ridge Mountains, one of the major ch ...

was the highest). In 1835, the state dispatched North Carolina professor Elisha Mitchell (1793–1857) into the western part of the state to measure the elevation of Grandfather, the Roan Highlands

Roan Mountain is a mountain straddling the North Carolina/Tennessee border in the Unaka Range of the Southern Appalachian Mountains in the Southeastern United States. The range's highpoint, Roan is clad in a dense stand of Southern Appalachian sp ...

, and the Black Mountains. Using a crude barometer

A barometer is a scientific instrument that is used to measure air pressure in a certain environment. Pressure tendency can forecast short term changes in the weather. Many measurements of air pressure are used within surface weather analysis ...

, Mitchell gained measurements for Grandfather and Roan with apparent ease, although he struggled to discern which of the Blacks was the highest. After measuring Celo Knob, Mitchell descended to the Cane River Valley to obtain advice from the valley's residents. Two local guides (one of whom was William Wilson, a cousin of the later renowned mountain guide, Thomas "Big Tom" Wilson) led Mitchell up a bear trail to what they believed to be the highest summit. Although exactly which mountain they summited has long been disputed, it was likely Mount Gibbes, Clingmans Peak, or Mount Mitchell. Nevertheless, Mitchell obtained a measurement of (later determined to be too low), placing the Blacks at a higher elevation than Mount Washington and thus the highest in the Eastern United States.

Mitchell returned to the Blacks in 1838 and 1844, gaining a higher measurement on each trip. Several surveyors visited the Blacks in subsequent years, including Nehemiah Blackstock (1794–1880) in 1845,

Mitchell returned to the Blacks in 1838 and 1844, gaining a higher measurement on each trip. Several surveyors visited the Blacks in subsequent years, including Nehemiah Blackstock (1794–1880) in 1845, Arnold Guyot

Arnold Henry Guyot ( ) (September 28, 1807February 8, 1884) was a Swiss-American geologist and geographer.

Early life

Guyot was born on September 28, 1807, at Boudevilliers, near Neuchâtel, Switzerland. He was educated at Chaux-de-Fonds, then ...

(1807–1884) in 1849, and Robert Gibbes in the early 1850s. As early as Mitchell's third trip (1844) to the Blacks, the locals were calling what is now Clingmans Peak "Mount Mitchell", as they believed this was the summit measured by Mitchell as the highest. In 1855, Thomas Lanier Clingman

Thomas Lanier Clingman (July 27, 1812November 3, 1897), known as the "Prince of Politicians," was a Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives from 1843 to 1845 and from 1847 to 1858, and U.S. senator from the state of Nort ...

(1812–1897), a politician and former student of Mitchell's, climbed a summit north of Stepps Gap known as Black Dome (what is now Mount Mitchell) and measured its elevation at . Clingman reported his findings to Joseph Henry, the head of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

. Henry, using Guyot's more careful and accurate measurements taken several years earlier, agreed with Clingman that Black Dome was higher (although Guyot noted Clingman's measurement of 6,941 feet was off by 200 feet), and the highest mountain in the Appalachians was to be named for Clingman.

When Mitchell learned of Clingman's find, he claimed that the mountain he had measured in 1844 was, in fact, Black Dome, and that locals had mistakenly named the summit to the south (the modern Clingmans Peak) after him. Clingman rejected Mitchell's claim, arguing that the route Mitchell took led south of Stepps Gap (i.e., to what is now Mount Gibbes or Clingmans Peak) and that a broken barometer found by Blackstock on Mount Gibbes in 1845 could only have been Mitchell's. The two bickered back and forth in the local newspapers throughout 1856, each claiming to have been the first to summit and measure the higher Black Dome. The debate was intensified by the political climate of the 1850s, as Mitchell was a Whig supporter and Clingman had recently left the Whig party to join the pro-secession Democrats. Zebulon Vance

Zebulon Baird Vance (May 13, 1830 – April 14, 1894) was the 37th and 43rd governor of North Carolina, a U.S. Senator from North Carolina, and a Confederate officer during the American Civil War.

A prolific writer and noted public speak ...

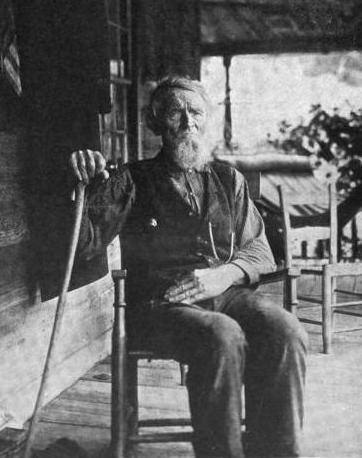

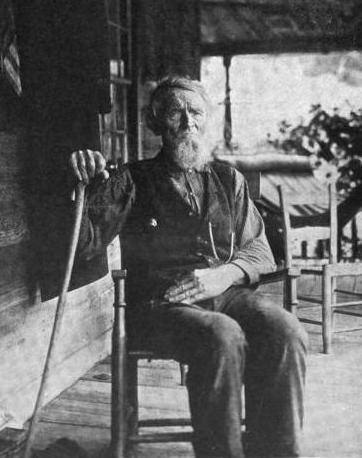

, a Whig politician and friend of Mitchell's, located the two guides Mitchell had recruited for his 1844 excursion, and when the two described the route they had followed, it appeared that Mitchell had indeed summited Mount Gibbes. Finally, in 1857, Mitchell returned to the Blacks in an attempt to gain still more accurate measurements. One evening, while attempting to reach the Cane River Valley, he slipped and fell into a gorge along Sugar Camp Fork, near the waterfall that now bears his name. His body was found 11 days later by the legendary mountain guide Thomas "Big Tom" Wilson (1825–1909).

Mitchell's death sparked an outpouring of public sympathy across North Carolina. Zebulon Vance led a movement to verify Mitchell as the first to summit the highest mountain in the Eastern United States and to have the mountain named for him. Vance convinced several mountain guides to change previous statements and claim the route they had taken actually led to Black Dome, rather than Mount Gibbes. Mitchell was buried atop Black Dome on land donated by former governor David Lowry Swain

David Lowry Swain (January 4, 1801August 27, 1868) was the List of Governors of North Carolina, 26th Governor of North Carolina, governor of the U.S. state of North Carolina, from 1832 to 1835.

He was born in Buncombe County, North Carolina; his ...

. Clingman continued to deny that Mitchell had measured Black Dome first, but was unable to overcome the shift in public sentiment. By 1858, Black Dome had been renamed "Mitchell's High Peak." In subsequent decades, Mount Mitchell was renamed "Clingmans Peak", and Mitchell's High Peak was renamed "Mount Mitchell." Clingman eventually turned to the Great Smoky Mountains

The Great Smoky Mountains (, ''Equa Dutsusdu Dodalv'') are a mountain range rising along the Tennessee–North Carolina border in the southeastern United States. They are a subrange of the Appalachian Mountains, and form part of the Blue Ridge ...

to the west, which he claimed were higher. Guyot's measurements in the Smokies rejected Clingman's assertions, although Guyot did manage to have the highest mountain in that range, known as Smoky Dome, renamed Clingmans Dome

Clingmans Dome (or Clingman's Dome) is a mountain in the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina in the southeastern United States. Its name in Cherokee is Kuwahi or Kuwohi (ᎫᏩᎯ or ᎫᏬᎯ), meaning "mulberry place." At an to ...

.

Tourism and logging

The revelation that the Black Mountains were the highest in the Appalachian Range made them an immediate tourist attraction. By the 1850s, a lodge had been established in the southern part of the range, and locals such as Jesse Stepp and Tom Wilson had built several rustic cabins on the higher mountain slopes and were thriving as mountain guides. The

The revelation that the Black Mountains were the highest in the Appalachian Range made them an immediate tourist attraction. By the 1850s, a lodge had been established in the southern part of the range, and locals such as Jesse Stepp and Tom Wilson had built several rustic cabins on the higher mountain slopes and were thriving as mountain guides. The American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

(1861–1865) brought a temporary halt to the tourism boom, but by the late 1870s, the industry had recovered. In the 1880s, brothers K.M. and David Murchison established a large game preserve in the Cane River Valley which was managed by Tom Wilson.

As forests in the north were cut down to meet the growing demand for lumber in the late 19th century, logging firms turned to the virgin forests of Southern Appalachia. Between 1908 and 1912, northern lumber firms, namely Dickey and Campbell (later Perley and Crockett), Brown Brothers, Carolina Spruce, and Champion Fibre, bought up timber rights to most of the Black Mountains and began a series of massive logging operations in the area. In 1911, Dickey and Campbell managed to construct a narrow-gauge railroad line connecting the Swannanoa Valley with Clingmans Peak. Other narrow-gauge lines quickly followed. Between 1909 and 1915, much of the forest on the upper slopes and crest was cut down. An increase in demand for red spruce during World War I led to the rapid deforestation of much of the spruce-fir forest in the higher elevations. As forests were removed, forest fires (caused by the ignition of dried brush and slash left by loggers) and erosion denuded what was left of the landscape.

The conservation movement

Many North Carolinians, among them Governor Locke Craig and state forester John Simcox Holmes, were alarmed at the abusive logging practices that were stripping bare the Black Mountains. After the North Carolina state legislature rejected an initial attempt to create a state park at the summit of Mount Mitchell in 1913, Craig began negotiating with (and may have threatened) Perley and Crockett to preserve the forest atop Mitchell while he and Holmes lobbied for the creation of a state park. The state legislature finally approved the purchase of a stretch of land between Stepps Gap and the summit of what is now Big Tom in 1915, which became the core of Mount Mitchell State Park. The Pisgah National Forest, established in 1916, also began buying up and replanting lands that had been logged over. In 1922, the Mount Mitchell Development Company (which had been formed by Fred Perley, a partner in Perley and Crockett) completed the first automobile road to Mount Mitchell, connecting the summit with the Swannanoa Valley. Adolphus and Ewart Wilson (the son and grandson of "Big Tom" Wilson) completed a road connecting the Cane River Valley with the summit of Mitchell shortly thereafter. The state eventually condemned the Wilsons' road, but allowed Ewart Wilson to operate an inn at Stepps Gap until the early 1960s. NC-128, which connects Mount Mitchell with the Blue Ridge Parkway, was completed in 1948.Environmental threats

The Black Mountains, like many other ranges in the Appalachians, are currently threatened byacid rain

Acid rain is rain or any other form of precipitation that is unusually acidic, meaning that it has elevated levels of hydrogen ions (low pH). Most water, including drinking water, has a neutral pH that exists between 6.5 and 8.5, but acid ...

and air pollution

Air pollution is the contamination of air due to the presence of substances in the atmosphere that are harmful to the health of humans and other living beings, or cause damage to the climate or to materials. There are many different types ...

. Much of the range's once-famous red spruce and Fraser fir trees are dead or dying due in part to the pollution. A more significant threat to the firs, however, is the balsam woolly adelgid

Balsam woolly adelgids (''Adelges piceae'') are small wingless insects that infest and kill firs, especially balsam fir and Fraser fir. They are an invasive species from Europe introduced to the United States around 1900.

Because this species ...

, an insect which may have an easier time killing the firs than it normally would due to them being weakened by the acid rain. In some recent studies, individual Fraser fir trees which are resistant to the adelgid have been found, lending hope to the possibility that these will again repopulate a healthy, mature fir forest at the mountains' highest elevations.

At lower elevations of the Black Mountains, eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

and Carolina hemlock

''Tsuga caroliniana'', the Carolina hemlock, is a species of hemlock endemic to the United States. Distribution and habitat

Carolina hemlock is native to the Appalachian Mountains in southwest Virginia, western North Carolina, extreme northeas ...

trees grow on moist slopes near streams (a National Forest recreation area on the Toe River at the base of Mount Mitchell is called "Carolina Hemlocks" for this reason). These too are under attack by an introduced pest, the hemlock woolly adelgid

The hemlock woolly adelgid (; ''Adelges tsugae''), or HWA, is an insect of the order Hemiptera (true bugs) native to East Asia. It feeds by sucking sap from hemlock and spruce trees (''Tsuga'' spp.; ''Picea'' spp.). In its native range, HWA ...

. Arriving only in the last few growing seasons, the health of the hemlocks in the region is rapidly declining. Research is currently underway in releasing predator beetles that will, hopefully, eat enough adelgids to balance their population and allow the hemlocks to flourish.

The area around the Black Mountains is also experiencing rapid population growth as retirees from other states pour into the region. Due to a lack of zoning laws, this has resulted in rapid development of ridgetop cabins, large second-homes on the lower ridges, and deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. The most concentrated d ...

that threatens the natural beauty of the region. The Clean Smokestacks Act of 2002 (S.L. 2002-4), enacted by the North Carolina General Assembly, is credited with reducing the amount of particulate and ozone pollution that had once threatened the views in the Black Mountains and throughout the Appalachians. Nitrogen Oxide emissions have plummeted from over 245,000 tons a year in 1998 to under 25,000 by 2014. Sulfur dioxide emissions saw a 64% decline. Fine particulates emissions in the area are now less than 60% of the national standard. Views which had been reduced to less than 10 miles by the late 1990s due to chronically hazy conditions, have been restored to 39 miles and the number of clear days has substantially increased.

Photo gallery

References

General sources

* Walter C. Biggs and James F. Parnell (1989). ''State Parks of North Carolina''. John F. Blair.External links

* *South Beyond 6000 in the Black Mountains

– Site provided by the Carolina Mountain Club {{Authority control Blue Ridge Mountains Mountains, Black Subranges of the Appalachian Mountains Mountains of Yancey County, North Carolina Mountains of Buncombe County, North Carolina