Australian home front during World War II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Although most Australian civilians lived far from the front line, the Australian home front during World War II played a significant role in the Allied victory and led to permanent changes to Australian society.

During the war the Government of Australia greatly expanded its powers in order to better direct the

Although most Australian civilians lived far from the front line, the Australian home front during World War II played a significant role in the Allied victory and led to permanent changes to Australian society.

During the war the Government of Australia greatly expanded its powers in order to better direct the

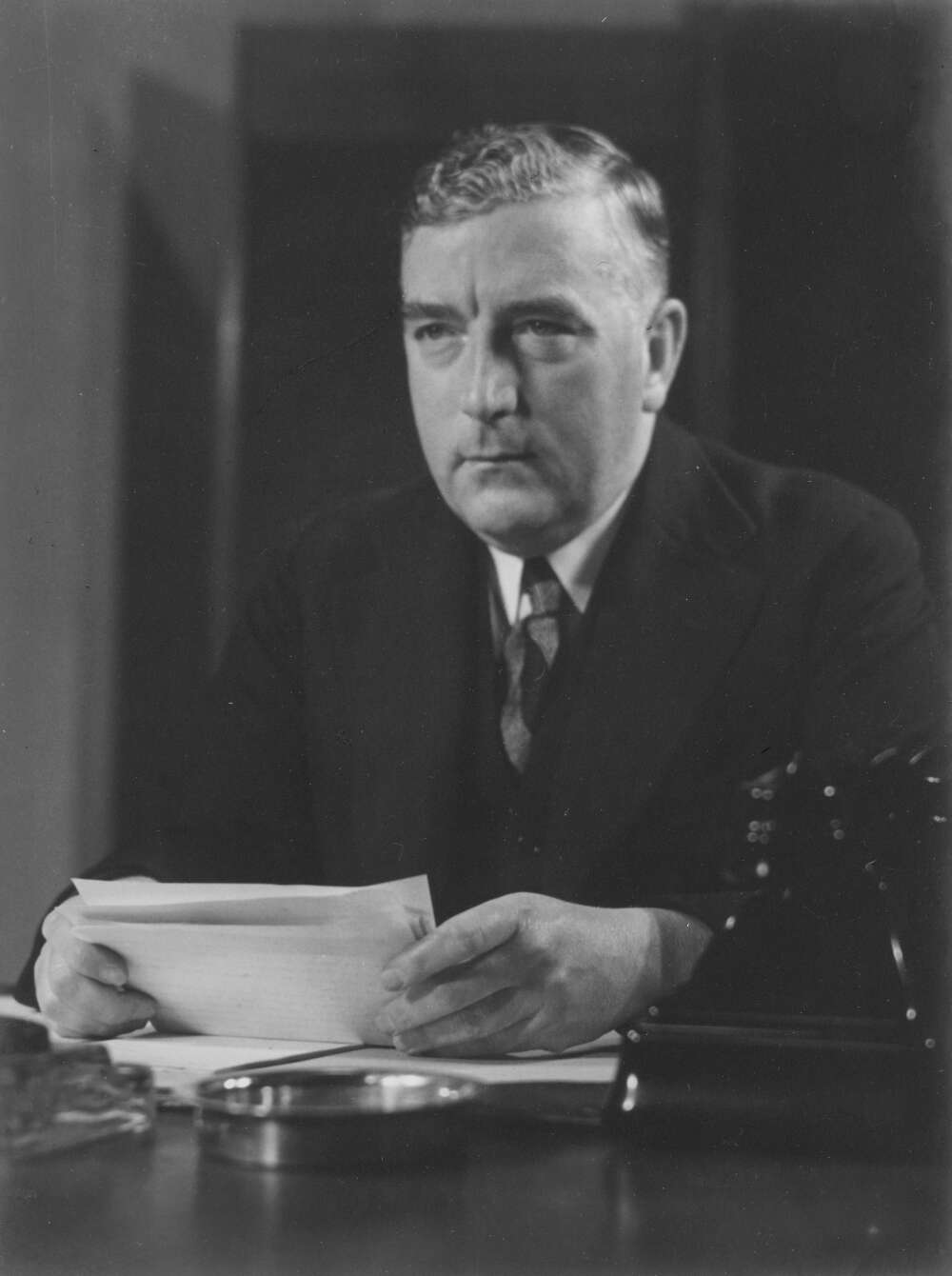

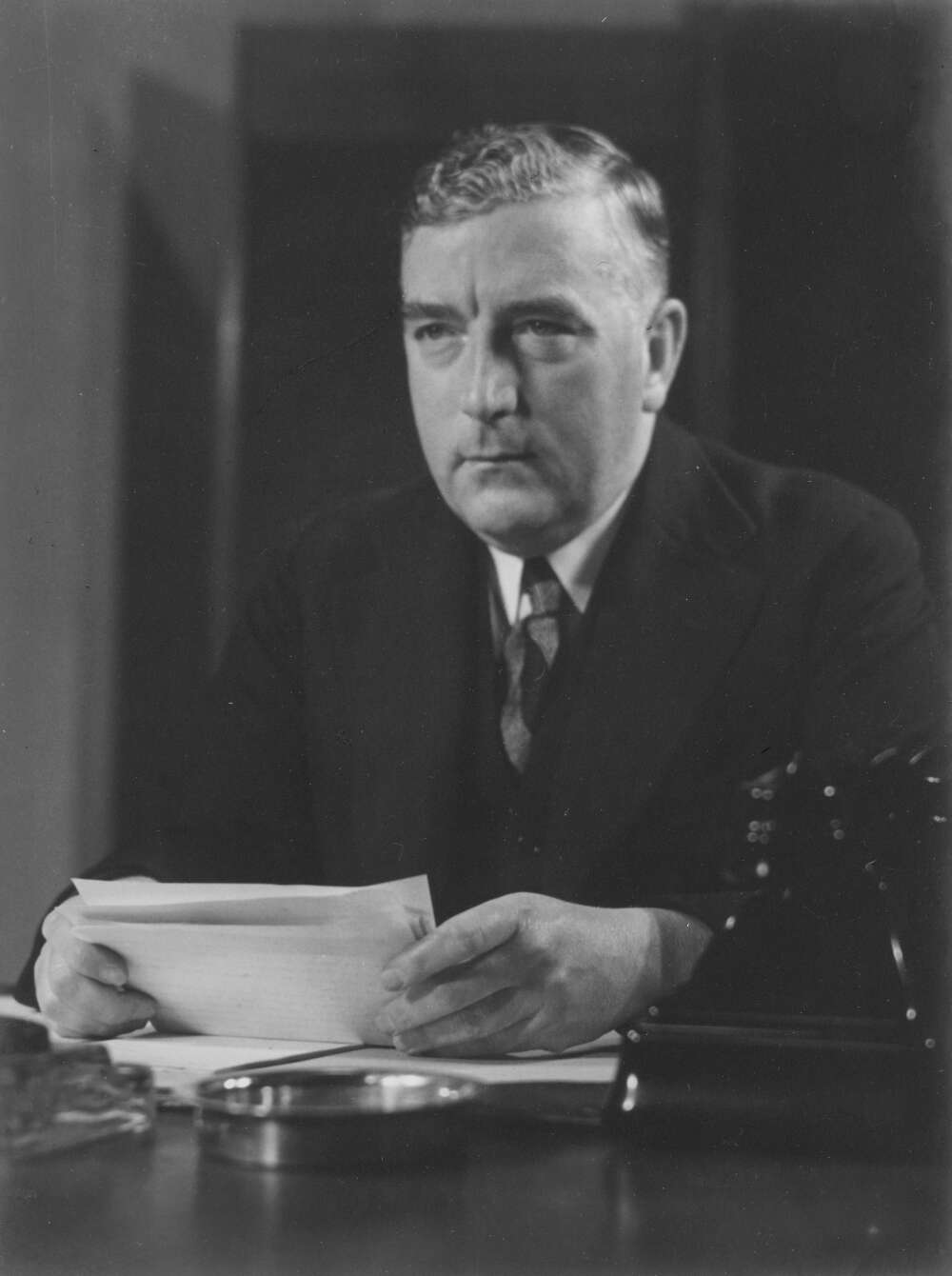

Robert Menzies was sworn in as Prime Minister of Australia for the first time on 26 April 1939 following the death of

Robert Menzies was sworn in as Prime Minister of Australia for the first time on 26 April 1939 following the death of

"Melbourne’s newest musical a multi-generational European family saga,"

Plus61J. There, armed soldiers manned watchtowers and scanned the camp that was bordered by a barbed wire fence with searchlights, and other armed soldiers patrolled the camp. Petitions to Australian politicians, stressing that they were Jewish refugees and therefore being unjustly imprisoned, had no effect."To the other side of the world,"

National Fund of the Republic of Austria for Victims of National Socialism. With the 1940 election looming, a

Eight weeks after the formation of the Curtin Government, on 7 December 1941 (eastern Australia time), Japan

Eight weeks after the formation of the Curtin Government, on 7 December 1941 (eastern Australia time), Japan

In an effort to isolate Australia, the Japanese planned a seaborne invasion of

In an effort to isolate Australia, the Japanese planned a seaborne invasion of  As the end of the war approached, Curtin sought to firm up Australian influence in the South Pacific following the war but also sought to ensure a continuing role for the British Empire, calling Australia "the bastion of British institutions, the British way of life and the system of democratic government in the Southern World". In April 1944, Curtin held talks on postwar planning with President Franklin Roosevelt of the US and with Prime Minister Winston Churchill of Britain and gained agreement for the Australian economy to begin transitioning from military to post-war economy. He returned to Australia and campaigned for an unsuccessful 1944 referendum to extend federal government power over employment, monopolies, Aboriginal people, health and railway gauges.

Prime Minister Curtin suffered from ill health from the strains of office. He suffered a major heart attack in November 1944. Facing the newly formed

As the end of the war approached, Curtin sought to firm up Australian influence in the South Pacific following the war but also sought to ensure a continuing role for the British Empire, calling Australia "the bastion of British institutions, the British way of life and the system of democratic government in the Southern World". In April 1944, Curtin held talks on postwar planning with President Franklin Roosevelt of the US and with Prime Minister Winston Churchill of Britain and gained agreement for the Australian economy to begin transitioning from military to post-war economy. He returned to Australia and campaigned for an unsuccessful 1944 referendum to extend federal government power over employment, monopolies, Aboriginal people, health and railway gauges.

Prime Minister Curtin suffered from ill health from the strains of office. He suffered a major heart attack in November 1944. Facing the newly formed

online

''Salt'' was the magazine of the Australian Army Education Service in the Second World War", with a circulation of 185,000 * * * * * * Saunders, Kay. ''War on the homefront: state intervention in Queensland 1938–1948'' (University of Queensland Press, 1993) * Spear, Jonathan A. "Embedded: the Australian Red Cross in the Second World War." (PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, 2007

online

* Spizzica, Mia. "On the Wrong Side of the Law (War): Italian Civilian Internment in Australia during World War Two." ''International Journal of the Humanities'' 9#11 (2012): 121–34. * Willis, Ian C, "The women's voluntary services, a study of war and volunteering in Camden, 1939–1945" PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2004

online

online

highly detailed statistics plus essays * ''Year Book Australia, 1946–47'' (1949

online

highly detailed statistics plus essays

{{World War II Australia in World War II Home front during World War II

Although most Australian civilians lived far from the front line, the Australian home front during World War II played a significant role in the Allied victory and led to permanent changes to Australian society.

During the war the Government of Australia greatly expanded its powers in order to better direct the

Although most Australian civilians lived far from the front line, the Australian home front during World War II played a significant role in the Allied victory and led to permanent changes to Australian society.

During the war the Government of Australia greatly expanded its powers in order to better direct the war effort

In politics and military planning, a war effort is a coordinated mobilization of society's resources—both industrial and human—towards the support of a military force. Depending on the militarization of the culture, the relative si ...

, and Australia's industrial and human resources were focused on supporting the Allied armed forces. While there were only a relatively small number of attacks on civilian targets, many Australians feared that the country would be invaded during the early years of the Pacific War.

Menzies Government

Robert Menzies was sworn in as Prime Minister of Australia for the first time on 26 April 1939 following the death of

Robert Menzies was sworn in as Prime Minister of Australia for the first time on 26 April 1939 following the death of Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the 10th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1932 until his death in 1939. He began his career in the Australian Labor Party (ALP), ...

. He led a minority United Australia Party

The United Australia Party (UAP) was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. The party won four federal elections in that time, usually governing in coalition with the Country Party. It provided two prim ...

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is ...

, after Country Party leader Earle Page

Sir Earle Christmas Grafton Page (8 August 188020 December 1961) was an Australian surgeon and politician who served as the 11th Prime Minister of Australia, holding office for 19 days after the death of Joseph Lyons in 1939. He was the leade ...

refused to serve in a Coalition government led by Menzies. On 3 September 1939, Australia entered World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, with Menzies making a declaration of a state of war in a national radio broadcast:

Earle Page

Sir Earle Christmas Grafton Page (8 August 188020 December 1961) was an Australian surgeon and politician who served as the 11th Prime Minister of Australia, holding office for 19 days after the death of Joseph Lyons in 1939. He was the leade ...

as leader of the Country Party and John Curtin

John Curtin (8 January 1885 – 5 July 1945) was an Australian politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Australia from 1941 until his death in 1945. He led the country for the majority of World War II, including all but the last few ...

as leader of the Labor Party both pledged support to the declaration, and Parliament passed the '' National Security Act 1939''. A War Cabinet was formed after the declaration of war, initially composed of Prime Minister Menzies and five senior ministers ( RG Casey, GA Street, Senator McLeay, HS Gullet and World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

Prime Minister Billy Hughes). When Page still refused to join a government under Menzies, he was replaced by Archie Cameron

Archie Galbraith Cameron (22 March 18959 August 1956) was an Australian politician. He was a government minister under Joseph Lyons and Robert Menzies, leader of the Country Party from 1939 to 1940, and finally Speaker of the House of Represe ...

as leader of the Country Party on 13 September 1939, allowing the conservative parties to re-form a Coalition by March 1940.

The recruitment of a volunteer military force for service at home and abroad was announced, the Second Australian Imperial Force

The Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF, or Second AIF) was the name given to the volunteer expeditionary force of the Australian Army in the Second World War. It was formed following the declaration of war on Nazi Germany, with an initia ...

, and a citizen militia was organised for local defence. Menzies committed to provide 20,000 men to augment British forces in Europe, and on 15 November 1939 announced the reintroduction of conscription for home-defence service, effective 1 January 1940, freeing volunteers for overseas service.

By June 1940, Germany had overrun the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, Norway and France leaving the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

standing alone against Germany. Menzies called for an ‘all in’ war effort and, with the support of Curtin, amended the ''National Security Act'' to extend government powers to tax, acquire property, control businesses and the labour force and allow for conscription of men for the "defence of Australia". Essington Lewis, the head of BHP

BHP Group Limited (formerly known as BHP Billiton) is an Australian multinational mining, metals, natural gas petroleum public company that is headquartered in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

The Broken Hill Proprietary Company was founded ...

was appointed Director-General of Munitions Supply to assist with mobilisation of national resources. However, in spring 1940, the coal miners under communist leadership struck for higher wages for 67 days. On 15 June 1940 the Menzies government suppressed 10 communist and fascist parties and organizations as subversive of the war effort. Police and army intelligence made hundreds of raids that night, and later broke up public meetings in the capital cities. In July 1940, the Menzies government imposed regulations under the ''National Security Act'' placing virtually all of Australia's newspapers, radio stations, and film industry under the direct control of the Director-General of Information. Newspaper publishers complained it was a blow struck at the freedom of the press. In January 1941, new regulations were directed against speaking disloyalty in public or even in private. The regulations were aimed at "whisperers" who undermined morale by spreading false rumours. During World War II many enemy alien

In customary international law, an enemy alien is any native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and ...

s were interned

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

in Australia under the ''National Security Act 1939''.

Prisoners of war were also sent to Australia from other Allied countries as were their enemy aliens for internment in Australia. About 7,000 residents were interned by Australia, including more than 1,500 British nationals. A further 8,000 people were sent to Australia to be interned after being detained overseas by Australia's allies. At its peak in 1942, more than 12,000 people were interned in Australia.

Jews seeking to escape the Nazis such as two-year-old Eva Duldig

Eva Ruth de Jong-Duldig (nee Duldig; born 11 February 1938) is an Austrian-born Australian and Dutch former tennis player, and current author. From the ages of two to four, she was detained by Australia in an isolated internment camp, as an enemy ...

and her parents Karl Duldig

Karl (Karol) Duldig (29 December 1902 – 11 August 1986) was a Jewish modernist sculptor.

and Slawa Duldig

Slawa Duldig née Horowitz (28 November 1901– 16 August 1975) was an inventor, artist, interior designer, and teacher. In 1928, as Slawa Horowitz, she created a design for an improved compact folding umbrella, which she patented in 1929. Slawa w ...

were classified as enemy aliens

In customary international law, an enemy alien is any native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured an ...

upon their arrival due to their having arrived with German identity papers

An identity document (also called ID or colloquially as papers) is any document that may be used to prove a person's identity. If issued in a small, standard credit card size form, it is usually called an identity card (IC, ID card, citizen ca ...

. The Australian government therefore interned the three of them for two years in isolated Tatura Internment Camp 3 D with 295 other internees, mostly families.Miriam Cosic (April 29, 2022)"Melbourne’s newest musical a multi-generational European family saga,"

Plus61J. There, armed soldiers manned watchtowers and scanned the camp that was bordered by a barbed wire fence with searchlights, and other armed soldiers patrolled the camp. Petitions to Australian politicians, stressing that they were Jewish refugees and therefore being unjustly imprisoned, had no effect."To the other side of the world,"

National Fund of the Republic of Austria for Victims of National Socialism. With the 1940 election looming, a

Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

crash at Canberra Airport

Canberra Airport is an international airport situated in the District of Majura, Australian Capital Territory serving Australia's capital city, Canberra, as well as the nearby city of Queanbeyan and regional areas of the Australian Capital Te ...

in August 1940 resulted in the death of the Chief of the General Staff and three senior ministers. The Labor Party meanwhile experienced a split along pro- and anti-Communist lines over policy towards the Soviet Union for its co-operation with Nazi Germany in the invasion of Poland. At the 1940 federal election in September, the UAP–Country Party Coalition and the Labor parties each won 36 seats and the Menzies Government was forced to rely on the support of two Independents to continue in office.

Menzies proposed an all party unity government to break the impasse, but the Labor Party refused to join. Curtin agreed instead to take a seat on a newly created Advisory War Council in October 1940. Cameron resigned as Country Party leader in October 1940, to be replaced by Arthur Fadden

Sir Arthur William Fadden, (13 April 189421 April 1973) was an Australian politician who served as the 13th prime minister of Australia from 29 August to 7 October 1941. He was the leader of the Country Party from 1940 to 1958 and also served ...

, who became Treasurer and Menzies unhappily conceded to allow Page back into his ministry.

In January 1941, Menzies flew to Britain to discuss the weakness of Singapore's defences and sat with Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

's British War Cabinet

A war cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war to efficiently and effectively conduct that war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers, although it is quite common for a war cabinet to have senio ...

. He was unable to achieve significant assurances for increased commitment to Singapore's defences, but undertook morale boosting excursions to war affected cities and factories. Returning to Australia via Lisbon and the United States in May, Menzies faced a war-time minority government under ever increasing strain. In Menzies's absence, Curtin had co-operated with Deputy Prime Minister Arthur Fadden in preparing Australia for the expected Pacific War. With the threat of Japan imminent and with the Australian army suffering badly in the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

campaigns, Menzies re-organised his ministry and announced multiple multi-party committees to advise on war and economic policy. Government critics however called for an all-party government.

After Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, Australian trade unions supported the war. Australian Women's Army Service

The Australian Women's Army Service (AWAS) was a non-medical women's service established in Australia during the Second World War. Raised on 13 August 1941 to "release men from certain military duties for employment in fighting units" the servi ...

was formed in August 1941 as a non-medical support service for the military.

In August 1941, Cabinet decided that Menzies should travel back to Britain to represent Australia in the War Cabinet, but this time the Labor caucus refused to support the plan. Menzies announced to his Cabinet that he thought he should resign and advise the Governor-General to invite Curtin to form Government. The Cabinet instead insisted he approach Curtin again to form a war cabinet. Unable to secure Curtin's support, and with an unworkable parliamentary majority, Menzies resigned as prime minister and leader of the UAP on 29 August 1941. He was succeeded as prime minister by Fadden, the leader of the Country Party, who held office for a month. Billy Hughes, then aged 79, replaced Menzies as leader of the UAP. The two independents crossed the floor

Crossed may refer to:

* ''Crossed'' (comics), a 2008 comic book series by Garth Ennis

* ''Crossed'' (novel), a 2010 young adult novel by Ally Condie

* "Crossed" (''The Walking Dead''), an episode of the television series ''The Walking Dead''

S ...

, bringing down the Coalition government, and enabling Labor under Curtin to form a minority government.

Curtin Government

Eight weeks after the formation of the Curtin Government, on 7 December 1941 (eastern Australia time), Japan

Eight weeks after the formation of the Curtin Government, on 7 December 1941 (eastern Australia time), Japan attacked Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

, the US naval base in Hawaii. On 10 December 1941, the British battleship HMS ''Prince of Wales'' and battlecruiser HMS ''Repulse'' sent to defend Singapore were sunk by Japan. British Malaya quickly collapsed, shocking the Australian population. British, Indian and Australian troops made a disorganised last stand at Singapore, before surrendering on 15 February 1942. On 27 December 1941, Curtin demanded reinforcements from Churchill, and published an historic announcement:

Curtin predicted that the "

battle for Australia

The Battle for Australia is a contested historiographical term used to claim a coordinated link between a series of battles near Australia during the Pacific War of the Second World War alleged to be in preparation for a Japanese invasion of ...

" would now follow. Australia was ill-prepared for an attack, lacking armaments, modern fighter aircraft, heavy bombers, and aircraft carriers. Most of Australia's best forces were committed to fight against Hitler in the Middle East. On 19 February, Darwin suffered a devastating air raid, the first time the Australian mainland had ever been attacked by enemy forces. Over the following 19 months, Australia was attacked from the air almost 100 times. Most elements of the Australian I Corps, including the 6th and 7th Divisions, returned to Australia in early 1942 to counter the perceived Japanese threat to Australia. All RAN's ships in the Mediterranean were also withdrawn to the Pacific but most RAAF units in the Middle East remained in the theatre.

U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt ordered his commander in the Philippines, General Douglas MacArthur, to formulate a Pacific defence plan with Australia in March 1942. Curtin agreed to place Australian forces under the command of General MacArthur, who became "Supreme Commander of the South West Pacific". Curtin had thus presided over a fundamental shift in Australia's foreign policy. MacArthur moved his headquarters to Melbourne in March 1942 and American troops began massing in Australia. In late May 1942, Japanese midget submarine

A midget submarine (also called a mini submarine) is any submarine under 150 tons, typically operated by a crew of one or two but sometimes up to six or nine, with little or no on-board living accommodation. They normally work with mother ships, ...

s sank an accommodation vessel in a daring raid on Sydney Harbour. On 8 June 1942, two Japanese submarines briefly shelled Sydney's eastern suburbs and the city of Newcastle.

In an effort to isolate Australia, the Japanese planned a seaborne invasion of

In an effort to isolate Australia, the Japanese planned a seaborne invasion of Port Moresby

(; Tok Pisin: ''Pot Mosbi''), also referred to as Pom City or simply Moresby, is the capital and largest city of Papua New Guinea. It is one of the largest cities in the southwestern Pacific (along with Jayapura) outside of Australia and New ...

, in the Australian Territory of New Guinea

The Territory of New Guinea was an Australian-administered United Nations trust territory on the island of New Guinea from 1914 until 1975. In 1949, the Territory and the Territory of Papua were established in an administrative union by the na ...

. In May 1942, the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

engaged the Japanese in the Battle of the Coral Sea and halted the attack. The Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under ...

in June effectively defeated the Japanese navy and the Japanese army launched a land assault on Port Moresby from the north.

The Australian Women's Land Army was formed on 27 July 1942 under the jurisdiction of the Director General of Manpower to combat rising labour shortages in the farming

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

sector.

The Battle of Buna-Gona

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and for ...

, between November 1942 and January 1943, set the tone for the bitter final stages of the New Guinea campaign

The New Guinea campaign of the Pacific War lasted from January 1942 until the end of the war in August 1945. During the initial phase in early 1942, the Empire of Japan invaded the Australian-administered Mandated Territory of New Guinea (23 Jan ...

, which persisted into 1945. MacArthur to a certain extent excluded Australian forces from the main push north into the Philippines and Japan. It was left to Australia to lead amphibious assault

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducted ...

s against Japanese bases in Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and eas ...

.

Curtin went on to lead federal Labor to its greatest win with two thirds of seats in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

and over 58% of the two-party preferred

In Australian politics, the two-party-preferred vote (TPP or 2PP) is the result of an election or opinion poll after preferences have been distributed to the highest two candidates, who in some cases can be independents. For the purposes of TPP, ...

vote at the 1943 federal election in August. Labor won 49 seats to 12 United Australia Party, 7 Country Party, 3 Country National Party (Queensland), 1 Queensland Country Party, 1 Liberal Country Party (Victoria) and 1 Independent. The Labor Party also won all 19 of the seats contested for the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

.

Concerned to maintain British commitment to the defence of Australia, Prime Minister Curtin announced in November 1943 that Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, (Henry William Frederick Albert; 31 March 1900 – 10 June 1974) was the third son and fourth child of King George V and Queen Mary. He served as Governor-General of Australia from 1945 to 1947, the only memb ...

, the brother of King George VI, was to be appointed Governor-General of Australia

The governor-general of Australia is the representative of the monarch, currently King Charles III, in Australia.Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

to Australia at that time.

As the end of the war approached, Curtin sought to firm up Australian influence in the South Pacific following the war but also sought to ensure a continuing role for the British Empire, calling Australia "the bastion of British institutions, the British way of life and the system of democratic government in the Southern World". In April 1944, Curtin held talks on postwar planning with President Franklin Roosevelt of the US and with Prime Minister Winston Churchill of Britain and gained agreement for the Australian economy to begin transitioning from military to post-war economy. He returned to Australia and campaigned for an unsuccessful 1944 referendum to extend federal government power over employment, monopolies, Aboriginal people, health and railway gauges.

Prime Minister Curtin suffered from ill health from the strains of office. He suffered a major heart attack in November 1944. Facing the newly formed

As the end of the war approached, Curtin sought to firm up Australian influence in the South Pacific following the war but also sought to ensure a continuing role for the British Empire, calling Australia "the bastion of British institutions, the British way of life and the system of democratic government in the Southern World". In April 1944, Curtin held talks on postwar planning with President Franklin Roosevelt of the US and with Prime Minister Winston Churchill of Britain and gained agreement for the Australian economy to begin transitioning from military to post-war economy. He returned to Australia and campaigned for an unsuccessful 1944 referendum to extend federal government power over employment, monopolies, Aboriginal people, health and railway gauges.

Prime Minister Curtin suffered from ill health from the strains of office. He suffered a major heart attack in November 1944. Facing the newly formed Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is a centre-right political party in Australia, one of the two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-left Australian Labor Party. It was founded in 1944 as the successor to the United Au ...

opposition led by Robert Menzies, Curtin struggled with exhaustion and a heavy work load – excusing himself from Parliamentary question time and unable to concentrate on the large number of parliamentary bills being drafted dealing with the coming peace. Curtin returned to hospital in April with lung congestion. With Deputy Prime Minister Frank Forde

Francis Michael Forde (18 July 189028 January 1983) was an Australian politician who served as prime minister of Australia from 6 to 13 July 1945. He was the deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1932 to 1946. He served as pri ...

in the United States and Ben Chifley

Joseph Benedict Chifley (; 22 September 1885 – 13 June 1951) was an Australian politician who served as the 16th prime minister of Australia from 1945 to 1949. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1945, follow ...

serving as acting prime minister, it was Chifley who announced the end of the war in Europe on 9 May 1945.

When Curtin died towards the end of the Second World War in July 1945, Forde served as prime minister from 6–13 July, before the party elected Ben Chifley as Curtin's successor. Following his 1945 election as leader of the Labor Party, Chifley, a former railway engine driver, became Australia's 16th prime minister on 13 July 1945. The Second World War ended with the defeat of Japan in the Pacific just four weeks later. Curtin is widely regarded as one of the country's greatest prime ministers. General MacArthur said that Curtin was "one of the greatest of the wartime statesmen".

Air raids

The Japanese air force made 97 air raids against Australia over a 19-month period starting with Darwin in February 1942 until 1943. The Darwin area was hit 64 times. Horn Island was struck 9 times, Broome and Exmouth Gulf 4 times, Townsville and Millingimbi three times, Port Hedland and Wyndham twice and Derby, Drysdale, Katherine, Mossman, Onslow, and Port Patterson once.Military production

Production of selected weapons for the Australian Army Australian aircraft production during World War IIBeaumont (2001), p 453.

See also

*Australian women during World War II

Australian women during World War II played a larger role than they had during World War I.

Military service

Many women wanted to play an active role in the war and hundreds of voluntary women's auxiliary and paramilitary organisations had been f ...

* Australian Women's Army Service

The Australian Women's Army Service (AWAS) was a non-medical women's service established in Australia during the Second World War. Raised on 13 August 1941 to "release men from certain military duties for employment in fighting units" the servi ...

* Australian Women's Land Army

* Home front during World War II

The term "home front" covers the activities of the civilians in a nation at war. World War II was a total war; homeland production became even more invaluable to both the Allied and Axis powers. Life on the home front during World War II was a s ...

* Military history of Australia during World War II

Australia entered World War II on 3 September 1939, following the government's acceptance of the United Kingdom's declaration of war on Nazi Germany. Australia later entered into a state of war with other members of the Axis powers, includ ...

* Military history of the British Commonwealth in the Second World War

When the United Kingdom declared war on Nazi Germany in September 1939 at the start of World War II, the UK controlled to varying degrees numerous crown colonies, protectorates and the India. It also maintained unique political ties to four of ...

* Military production during World War II

Military production during World War II was the arms, ammunition, personnel and financing which were produced or mobilized by the belligerents of the war from the occupation of Austria in early 1938 to the surrender and occupation of Japan in ...

* Volunteer Air Observer Corp

Notes

References

* * Barrett, John. "Living in Australia, 1939–1945." ''Journal of Australian Studies'' 1#2 (1977): 107–118. * * * * Darian-Smith, Kate. ''On the home front: Melbourne in wartime, 1939–1945'' (Oxford University Press, 1990) * Davis, Joan. "'Women's Work' and the Women's Services in the Second World War as Presented in Salt," ''Hecate'' (192) v 18#1 pp 64online

''Salt'' was the magazine of the Australian Army Education Service in the Second World War", with a circulation of 185,000 * * * * * * Saunders, Kay. ''War on the homefront: state intervention in Queensland 1938–1948'' (University of Queensland Press, 1993) * Spear, Jonathan A. "Embedded: the Australian Red Cross in the Second World War." (PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, 2007

online

* Spizzica, Mia. "On the Wrong Side of the Law (War): Italian Civilian Internment in Australia during World War Two." ''International Journal of the Humanities'' 9#11 (2012): 121–34. * Willis, Ian C, "The women's voluntary services, a study of war and volunteering in Camden, 1939–1945" PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2004

online

Primary sources

* ''Year Book Australia, 1944–45'' (1947online

highly detailed statistics plus essays * ''Year Book Australia, 1946–47'' (1949

online

highly detailed statistics plus essays

External links

* Australian War Memoria{{World War II Australia in World War II Home front during World War II

Home front

Home front is an English language term with analogues in other languages. It is commonly used to describe the full participation of the British public in World War I who suffered Zeppelin raids and endured food rations as part of what came t ...

1940s in Australia

History of Australia (1901–1945)