Australian Flying Corps on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Australian Flying Corps (AFC) was the branch of the

After the outbreak of war in 1914, the Australian Flying Corps sent one aircraft, a

After the outbreak of war in 1914, the Australian Flying Corps sent one aircraft, a  During the final Allied offensive that eventually brought an end to the war – the

During the final Allied offensive that eventually brought an end to the war – the

The corps remained small throughout the war, and opportunities to serve in its ranks were limited. A total of 880 officers and 2,840 other ranks served in the AFC, of whom only 410 served as pilots and 153 served as observers. A further 200 men served as aircrew in the British flying services – the RFC or the

The corps remained small throughout the war, and opportunities to serve in its ranks were limited. A total of 880 officers and 2,840 other ranks served in the AFC, of whom only 410 served as pilots and 153 served as observers. A further 200 men served as aircrew in the British flying services – the RFC or the

Warfare in a New Dimension: The Australian Flying Corps in the First World War

{{Wwi-air, state=collapsed Army aviation units and formations Australian military aviation Aviation in World War I British Empire in World War I Military units and formations established in 1912 Military units and formations disestablished in 1920 Military units and formations of Australia in World War I 1912 establishments in Australia Aviation history of Australia

Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (Austral ...

responsible for operating aircraft during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, and the forerunner of the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

(RAAF). The AFC was established in 1912, though it was not until 1914 that it began flight training.

In 1911, at the Imperial Conference

Imperial Conferences (Colonial Conferences before 1907) were periodic gatherings of government leaders from the self-governing colonies and dominions of the British Empire between 1887 and 1937, before the establishment of regular Meetings of ...

held in London, it was decided that aviation should be developed by the national armed forces of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. Australia became the first member of the Empire to follow this policy. By the end of 1911, the Army was advertising for pilots and mechanics. During 1912, pilots and mechanics were appointed, aircraft were ordered, the site of a flying school was chosen and the first squadron was officially raised. On 7 March 1913, the government officially announced formation of the Central Flying School

The Central Flying School (CFS) is the Royal Air Force's primary institution for the training of military flying instructors. Established in 1912 at the Upavon Aerodrome, it is the longest existing flying training school. The school was based at ...

(CFS) and an "Australian Aviation Corps", although that name was never widely used.

AFC units were formed for service overseas with the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) during World War I. They operated initially in the Mesopotamian Campaign

The Mesopotamian campaign was a campaign in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I fought between the Allies represented by the British Empire, troops from Britain, Australia and the vast majority from British India, against the Central Powe ...

. The AFC later saw action in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

and France. A training wing was established in the United Kingdom. The corps remained part of the Australian Army until it was disbanded in 1919, after which it was temporarily replaced by the Australian Air Corps

The Australian Air Corps (AAC) was a temporary formation of the Australian military that existed in the period between the disbandment of the Australian Flying Corps (AFC) of World War I and the establishment of the Royal Australian Air F ...

. In 1921, that formation was re-established as the independent RAAF.

Establishment

On 30 December 1911, the '' Commonwealth Gazette'' announced that the Australian military would seek the "...appointment of two competent Mechanists and Aviators", adding that the government would "accept no liability for accidents". On 3 July 1912, the first "flying machines" were ordered: two Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 two-seattractor

A tractor is an engineering vehicle specifically designed to deliver a high tractive effort (or torque) at slow speeds, for the purposes of hauling a trailer or machinery such as that used in agriculture, mining or construction. Most common ...

biplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While ...

s and two British-built Deperdussin single-seat tractor monoplanes. Soon afterward, two pilots were appointed: Henry Petre

Henry Aloysius Petre, DSO, MC (12 June 1884 – 24 April 1962) was an English solicitor who became Australia's first military aviator and a founding member of the Australian Flying Corps, the predecessor of the Royal Austral ...

(6 August) and Eric Harrison

Sir Eric John Harrison, (7 September 1892 – 26 September 1974) was an Australian politician and diplomat. He was the inaugural deputy leader of the Liberal Party (1945–1956), and a government minister under four prime ministers. He was lat ...

(11 August).

On 22 September 1912, the Minister of Defence

A defence minister or minister of defence is a Cabinet (government), cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from coun ...

, Senator George Pearce

Sir George Foster Pearce KCVO (14 January 1870 – 24 June 1952) was an Australian politician who served as a Senator for Western Australia from 1901 to 1938. He began his career in the Labor Party but later joined the National Labor Party, t ...

, officially approved formation of an Australian military air arm. Petre rejected a suggestion by Captain Oswald Watt

Walter Oswald Watt, (11 February 1878 – 21 May 1921) was an Australian aviator and businessman. The son of a Scottish-Australian merchant and politician, he was born in England and moved to Sydney when he was one year old, returning ...

that a Central Flying School

The Central Flying School (CFS) is the Royal Air Force's primary institution for the training of military flying instructors. Established in 1912 at the Upavon Aerodrome, it is the longest existing flying training school. The school was based at ...

be established in Canberra, near the Royal Military College, Duntroon

lit: Learning promotes strength

, established =

, type = Military college

, chancellor =

, head_label = Commandant

, head = Brigadier Ana Duncan

, principal =

, city = Campbell

, state = ...

, because it was too high above sea level. Petre instead recommended several sites in Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

and one of these was chosen, at Point Cook, Victoria

Point Cook is a suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, south-west of Melbourne's Central Business District, located within the City of Wyndham local government area. Point Cook recorded a population of 66,781 at the 2021 census.

Point Cook ...

, on 22 October 1912. Two days later, on 24 October 1912, the government authorised the raising of a single squadron. Upon establishment the squadron would be equipped with four aircraft and manned by "...four officers, seven warrant officers and sergeants, and 32 mechanics", drawn from volunteers already serving in the Citizen Forces.

On 7 March 1913, the government officially announced formation of the Central Flying School (CFS) and the "Australian Aviation Corps". According to the Australian War Memorial

The Australian War Memorial is Australia's national memorial to the members of its armed forces and supporting organisations who have died or participated in wars involving the Commonwealth of Australia and some conflicts involving pe ...

, the name "Australian Flying Corps does not appear to have been promulgated officially but seems to have been derived from the term Australian Aviation Corps. The first mention of an Australian Flying Corps appears in Military Orders of 1914." Flying training did not begin immediately; it was not until 1914 that the first class of pilots were accepted. No. 1 Flight of the Australian Flying Corps was raised in the 3rd Military District on 14 July 1914.

In March 1914, a staff officer, Major Edgar Reynolds, was officially appointed General Staff Officer in charge of a branch covering "intelligence, censorship, and aviation" within the Army's Department of Military Operations. Following the outbreak of World War I and the expansion of the Army, aviation became a separate branch commanded by Reynolds. AFC operational units were attached and subordinate to Australian ground forces and/or British ground and air commands. Reynolds' role was mostly administrative rather than one that involved operational command.

World War I

Operations

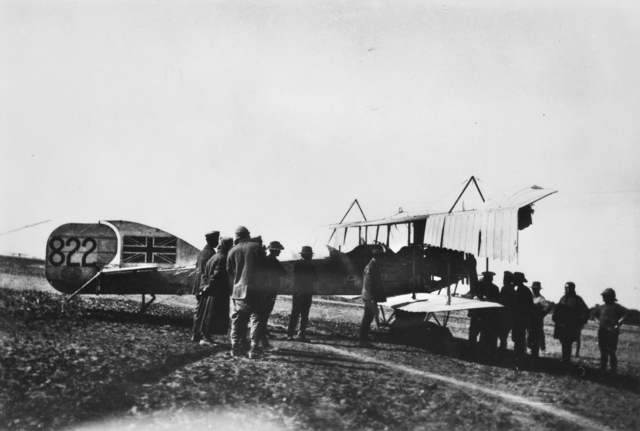

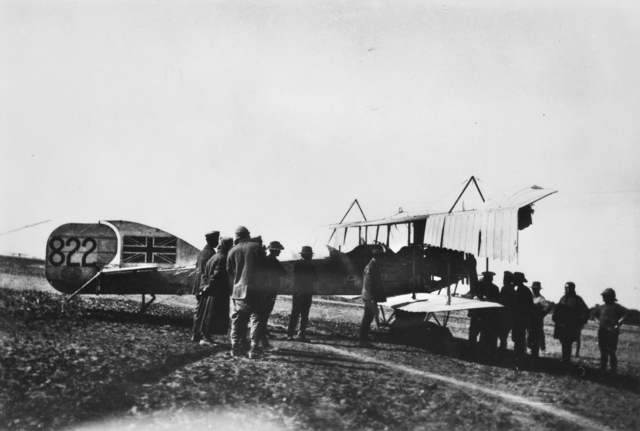

After the outbreak of war in 1914, the Australian Flying Corps sent one aircraft, a

After the outbreak of war in 1914, the Australian Flying Corps sent one aircraft, a B.E.2

The Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 was a British single-engine tractor two-seat biplane designed and developed at the Royal Aircraft Factory. Most of the roughly 3,500 built were constructed under contract by private companies, including establish ...

, to assist in capturing the German colonies in northern New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

and the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capita ...

. German forces in the Pacific surrendered quickly, before the aircraft was even unpacked from its shipping crate.

The first operational flights did not occur until 27 May 1915, when the Mesopotamian Half Flight

The Mesopotamian Half-Flight (MHF), or Australian Half-Flight, was the first Australian Flying Corps (AFC) unit to see active service during World War I. Formed in April 1915 at the request of the Indian Government, the half-flight's personnel w ...

(MHF), under the command of Captain Henry Petre, was called upon to assist the Indian Army

The Indian Army is the land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), who is a four- ...

in protecting British oil interests in what is now Iraq. Operating a mixture of aircraft including Caudron

The Société des Avions Caudron was a French aircraft company founded in 1909 as the Association Aéroplanes Caudron Frères by brothers Gaston and René Caudron. It was one of the earliest aircraft manufacturers in France and produced planes for ...

s, Maurice Farman Shorthorns, Maurice Farman Longhorns and Martinsyde

Martinsyde was a British aircraft and motorcycle manufacturer between 1908 and 1922, when it was forced into liquidation by a factory fire.

History

The company was first formed in 1908 as a partnership between H.P. Martin and George Handasyde ...

s, the MHF initially undertook unarmed reconnaissance operations, before undertaking light bombing operations later in the year after being attached to No. 30 Squadron RFC. Losses were high and by December, after flying supplies to the besieged garrison at Kut, the MHF was disbanded.

In January 1916, No. 1 Squadron was raised at Point Cook in response to a British request for Australia to raise a full squadron to serve as part of the RFC. Reynolds served as the squadron's commanding officer, prior to its embarkation for overseas service. The squadron, consisting of 12 aircraft organised into three flight

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere (i.e. air flight or aviation) or through the vacuum of outer space (i.e. spaceflight). This can be a ...

s, arrived in Egypt in April and was subsequently assigned to the RFC's 5th Wing. In mid-June it began operations against Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

(Turkish) and Senussi

The Senusiyya, Senussi or Sanusi ( ar, السنوسية ''as-Sanūssiyya'') are a Muslim political-religious tariqa (Sufi order) and clan in colonial Libya and the Sudan region founded in Mecca in 1837 by the Grand Senussi ( ar, السنوسي ...

Arab forces in Egypt and Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

. It would remain in the Middle East until the end of the war, being reassigned to No. 40 Wing in October 1917, undertaking reconnaissance, ground liaison and close air support

In military tactics, close air support (CAS) is defined as air action such as air strikes by fixed or rotary-winged aircraft against hostile targets near friendly forces and require detailed integration of each air mission with fire and moveme ...

operations as the British Empire forces advanced into Syria, initially flying a mixture of aircraft including B.E.2cs, Martinsyde G.100s, B.E.12as and R.E.8s – but later standardising on Bristol Fighters. One of the squadron's pilots, Lieutenant Frank McNamara, received the only Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previously ...

awarded to an Australian airman during the war, receiving the award for rescuing a fellow pilot who had been downed behind Turkish lines in early 1917. No. 1 Squadron was credited with the destruction of 29 enemy aircraft.

Three other squadrons – No. 2, No. 3 and No. 4 – were raised in 1917 in Egypt or Australia, and were sent to France. Arriving there between August and December, these squadrons subsequently undertook operations under the operational command of British Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

(RFC) wing

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is expres ...

s along the Western Front. No. 2 Squadron, under the command of Major Oswald Watt, who had previously served in the French Foreign Legion, was the first AFC unit to see action in Europe. Flying DH.5 fighters, the squadron made its debut around St Quentin, fighting a short action with a German patrol and suffering the loss of one aircraft forced down. The following month the squadron took part in the Battle of Cambrai, flying on combat air patrols, and bombing and strafing missions in support of the British Third Army, suffering heavy losses in dangerous low-level attacks that later received high praise from General Hugh Trenchard

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Hugh Montague Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard, (3 February 1873 – 10 February 1956) was a British officer who was instrumental in establishing the Royal Air Force. He has been described as the "Father of the ...

, commander of the RFC. The squadron's DH.5s were replaced with superior S.E.5a fighters in December 1917, with which the squadron resumed operations shortly afterwards. Operating R.E.8 reconnaissance aircraft, No. 3 Squadron entered the war during final phase of the Battle of Passchendaele

The Third Battle of Ypres (german: link=no, Dritte Flandernschlacht; french: link=no, Troisième Bataille des Flandres; nl, Derde Slag om Ieper), also known as the Battle of Passchendaele (), was a campaign of the First World War, fought by t ...

, also in November, during which they were employed largely as artillery spotters. No.4 Squadron entered the fighting last. Equipped with Sopwith Camel

The Sopwith Camel is a British First World War single-seat biplane fighter aircraft that was introduced on the Western Front in 1917. It was developed by the Sopwith Aviation Company as a successor to the Sopwith Pup and became one of the b ...

s, the squadron was dispatched to a quiet sector around Lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements''), ...

initially and did not see combat until January 1918.

During the final Allied offensive that eventually brought an end to the war – the

During the final Allied offensive that eventually brought an end to the war – the Hundred Days Offensive

The Hundred Days Offensive (8 August to 11 November 1918) was a series of massive Allies of World War I, Allied offensives that ended the First World War. Beginning with the Battle of Amiens (1918), Battle of Amiens (8–12 August) on the Wester ...

– the AFC squadrons flew reconnaissance and observation missions around Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

in August, as well as launching raids around Ypres

Ypres ( , ; nl, Ieper ; vls, Yper; german: Ypern ) is a Belgian city and municipality in the province of West Flanders. Though

the Dutch name is the official one, the city's French name is most commonly used in English. The municipality co ...

, Arras

Arras ( , ; pcd, Aro; historical nl, Atrecht ) is the prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais Departments of France, department, which forms part of the regions of France, region of Hauts-de-France; before the regions of France#Reform and mergers of ...

and Lille

Lille ( , ; nl, Rijsel ; pcd, Lile; vls, Rysel) is a city in the northern part of France, in French Flanders. On the river Deûle, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, region, the Pref ...

. Operations continued until the end of the war, some of the fiercest air-to-air fighting occurring on 29 October, when 15 Sopwith Snipe

The Sopwith 7F.1 Snipe was a British single-seat biplane fighter of the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was designed and built by the Sopwith Aviation Company during the First World War, and came into squadron service a few weeks before the end of th ...

s from No. 4 Squadron fought an engagement with a group of Fokkers that outnumbered them four to one. In the ensuing fighting, the Australians shot down 10 German aircraft for the loss of just one of their own. During their time along the Western Front, the two fighter squadrons – No. 2 and 4 – accounted for 384 German aircraft, No. 4 taking credit for 199 and No. 2 for 185. The squadron were also credited with 33 enemy balloons destroyed or driven down. No. 3 Squadron, operating in the corps reconnaissance role, accounted for another 51 aircraft.

Organisation

By the end of the war, four squadrons had seen active service, operating alongside and under British Royal Flying Corps (and in 1918 theRoyal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

) command. For administrative reasons, and to avoid confusion with similarly numbered RFC units, at one stage each AFC squadron was allocated an RFC number – the Australians themselves never used these numbers, and in the end, to avoid further confusion, the original AFC numbers were reinstated. The four operational squadrons of the AFC were:

In the Middle East, No. 1 Squadron was initially assigned to No. 5 Wing after being formed, but was later transferred to No. 40 Wing in late 1917, remaining as part of that formation until the end of the war. In Europe, No. 2 Squadron formed part of No. 51 Wing, but in 1918 it was transferred to No. 80 Wing, joining No. 4 Squadron which had been transferred from No. 11 Wing. No. 3 Squadron trained as part of No. 23 Wing until it was committed to the Western Front in August 1917, when it became a "corps squadron", tasked with supporting the British XIII

XIII may refer to:

* 13 (number) or XIII in Roman numerals

* 13th century in Roman numerals

* ''XIII'' (comics), a Belgian comic book series by Jean Van Hamme and William Vance

** ''XIII'' (2003 video game), a 2003 video game based on the comic b ...

and Canadian Corps

The Canadian Corps was a World War I corps formed from the Canadian Expeditionary Force in September 1915 after the arrival of the 2nd Canadian Division in France. The corps was expanded by the addition of the 3rd Canadian Division in December ...

.

As well as the operational squadrons, a training wing was established in the United Kingdom. Designated as the 1st Training Wing, it was made up of four squadrons. The four training squadrons of the AFC were:

As the war progressed, there were plans to increase the AFC's number of operational squadrons from four to fifteen by 1921, but the war came to an end before these could be raised.

Personnel

The corps remained small throughout the war, and opportunities to serve in its ranks were limited. A total of 880 officers and 2,840 other ranks served in the AFC, of whom only 410 served as pilots and 153 served as observers. A further 200 men served as aircrew in the British flying services – the RFC or the

The corps remained small throughout the war, and opportunities to serve in its ranks were limited. A total of 880 officers and 2,840 other ranks served in the AFC, of whom only 410 served as pilots and 153 served as observers. A further 200 men served as aircrew in the British flying services – the RFC or the Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps t ...

(RNAS) – including men such as Charles Kingsford Smith

Sir Charles Edward Kingsford Smith (9 February 18978 November 1935), nicknamed Smithy, was an Australian aviation pioneer. He piloted the first transpacific flight and the first flight between Australia and New Zealand.

Kingsford Smith was b ...

and Bert Hinkler

Herbert John Louis Hinkler (8 December 1892 – 7 January 1933), better known as Bert Hinkler, was a pioneer Australian aviator (dubbed "Australian Lone Eagle") and inventor. He designed and built early aircraft before being the first person ...

, both of whom would have a significant impact upon aviation in Australia after the war. Casualties included 175 dead, 111 wounded, 6 gassed and 40 captured. The majority of these casualties were suffered on the Western Front where 78 Australians were killed, 68 were wounded and 33 became prisoners of war. This represented a casualty rate of 44 percent, which was only marginally lower than most Australian infantry battalions that fought in the trenches, who averaged a casualty rate of around 50 percent. Molkentin attributes the high loss rate in part to the policy of not issuing pilots with parachutes

A parachute is a device used to slow the motion of an object through an atmosphere by creating drag or, in a ram-air parachute, aerodynamic lift. A major application is to support people, for recreation or as a safety device for aviators, who ...

, as well as the fact that the bulk of patrols were conducted over enemy lines, both of which were in keeping with British policy.

Pilots from the AFC's four operational squadrons claimed 527 enemy aircraft destroyed or driven down, and the corps produced 57 flying aces

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aerial combat. The exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ace is varied, but is usually co ...

. The highest-scoring AFC pilot was Harry Cobby

Air Commodore Arthur Henry Cobby, (26 August 1894 – 11 November 1955) was an Australian military aviator. He was the leading fighter ace of the Australian Flying Corps during World War I, with 29 victories, despite seeing active servic ...

, who was credited with 29 victories. Other leading aces included Roy King (26), Edgar McCloughry (21), Francis Smith (16), and Roy Phillipps

Roy Cecil Phillipps, MC & Bar, DFC (1 March 1892 – 21 May 1941) was an Australian fighter ace of World War I. He achieved fifteen victories in aerial combat, four of them in a single action on 12 June 1918. A grazier b ...

(15). Robert Little and Roderic (Stan) Dallas, the highest-scoring Australian aces of the war, credited with 47 and 39 victories respectively, served with the RNAS. Other Australian aces who served in British units included Jerry Pentland (23), Richard Minifie

Richard Pearman Minifie, (2 February 1898 – 31 March 1969) was an Australian fighter pilot and flying ace of the First World War. Born in Victoria, he attended Melbourne Church of England Grammar School. Travelling to the United Kingdom, he en ...

(21), Edgar Johnston

Edgar Charles Johnston, DFC (30 April 1896 – 22 May 1988) was an Australian fighter pilot and ace of the First World War and, later, a leading member in civil aviation in Australia.

Early life and First World War

Johnston was born in Pert ...

(20), Andrew Cowper (19), Cedric Howell

Cedric Ernest "Spike" Howell, (17 June 1896 – 10 December 1919) was an Australian fighter pilot and flying ace of the First World War. Born in Adelaide, South Australia, he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in 1916 for service in th ...

(19), Fred Holliday (17), and Allan Hepburn (16). Several officers gained appointment in senior command roles, two commanding wings

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is expresse ...

and nine commanding squadrons. One member of the AFC was awarded the Victoria Cross and another 40 received the Distinguished Flying Cross, including two who received the awarded three times.

Equipment

The Australian Flying Corps operated a range of aircraft types. These types were mainly of British origin, although French aircraft were also obtained. Over this period aircraft technology progressed rapidly and designs included relatively fragile and rudimentary types to more advanced single-engined biplanes, as well as one twin-engined bomber. The roles performed by these aircraft evolved during the war and included reconnaissance, observation for artillery, aerial bombing and ground attack, patrolling, and the resupply of ground troops on the battlefield by airdrop.Training

The AFC conducted both pilot and mechanic training in Australia at the Central Flying School, which was established at Point Cook, but this was limited in duration due to embarkation schedules, which meant that further training was required overseas before aircrew were posted to operational squadrons. The first course began on 17 August 1914 and lasted three months; two instructors, Henry Petre and Eric Harrison, who had been recruited from the United Kingdom in 1912 to establish the corps, trained the first batch of Australian aircrew. In the end, a total of eight flying training courses were completed at the Central Flying School during the war, the final course commencing in June 1917. The first six courses consisted only of officers, but the last two, both conducted in early and mid-1917 included non-commissioned officers. These courses ranged in size from four on the first course, to eight on the next three, 16 on the fifth, 24 on the sixth, 31 on the seventh and 17 on the last one. There was limited wastage on the early courses, all trainees successfully completing the first six courses, but final two courses run in 1917 suffered heavily from limited resources and bad weather, resulting in less than half the students graduating. To complement the aviators trained by the CFS, theNew South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

government established its own aviation school at Clarendon, at what later became RAAF Base Richmond

RAAF Base Richmond is a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) military air base located within the City of Hawkesbury, approximately North-West of the Sydney Central Business District in New South Wales, Australia. Situated between the towns of W ...

, which trained pilots, observers and mechanics. A total of 50 pilots graduated from the school, the majority of its graduates went on to serve in the British flying services, although some served in the AFC.

In early 1917, the AFC began training pilots, observers and mechanics in the United Kingdom. Aircrew were selected from volunteers from other arms such as the infantry, light horse, engineers or artillery, many of whom had previously served at the front, who reverted to the rank of cadet and undertook a six-week foundation course at the two Schools of Military Aeronautics in Reading

Reading is the process of taking in the sense or meaning of Letter (alphabet), letters, symbols, etc., especially by Visual perception, sight or Somatosensory system, touch.

For educators and researchers, reading is a multifaceted process invo ...

or Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. After this, those who passed graduated to flight training at one of the four AFC training squadrons: Nos. 5, 6, 7 and 8, which were based at Minchinhampton

Minchinhampton is an ancient Cotswolds market town in the Stroud District in Gloucestershire, South West England. The town is located on a hilltop, south-east of Stroud. The common offers wide views over the Severn Estuary into Wales and furth ...

and Leighterton

Leighterton is a village in rural Gloucestershire off the A46. It sits within the civil parish of Boxwell with Leighterton, 4.25 miles west-southwest of Tetbury, towards the southern end of the Cotswolds AONB. Situated in the Cotswold hills, ...

in Gloucestershire.

Flight training in the UK consisted of a total of three hours dual instruction followed by up to a further 20 hours solo flying – although some pilots, including the AFC's highest-scoring ace, Harry Cobby, received less – after which a pilot had to prove his ability to undertake aerial bombing, photography, formation flying, signalling, dog-fighting and artillery observation. Elementary training was undertaken on types such as Shorthorns, Avro 504s and Pups, followed by operational training on Scouts, Camels and RE8s. Upon completion, pilots received their commission and their "wings", and were allocated to the different squadrons based on their aptitude during training: the best were usually sent to scout squadrons, and the remainder to two-seaters.

Initially, the AFC raised its ground staff from volunteer soldiers and civilians who had previous experience or who were trade trained, and when the first AFC squadron was formed these personnel were provided with very limited training that was focused mainly upon basic military skills. As the war progressed, a comprehensive training program was established in which mechanics were trained in nine different trades: welders, blacksmiths, coppersmiths, engine fitters, general fitters, riggers, electricians, magneto-repairers, and machinists. Training was delivered by eight technical sections at Halton Camp. The length of training within each section varied, but was generally between eight to 12 weeks; the more complex trades such as engine fitter required trainees to undertake multiple training courses across several sections. General fitters had the longest training requirements, receiving 32 weeks of instruction.

Post-war legacy

Following thearmistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

that came into effect on 11 November 1918, the AIF returned to Australia in stages, some elements performing reconstruction and military occupation

Military occupation, also known as belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is the effective military control by a ruling power over a territory that is outside of that power's sovereign territory.Eyāl Benveniśtî. The international law ...

duties in Europe. No. 4 Squadron AFC took part in the occupation of Germany, the only Australian unit to do so; it operated as part of the British Army of Occupation

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

around Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

between December 1918 and March 1919 before transferring its aircraft to the British and returning to Australia along with the other three squadrons. Reynolds was succeeded by Colonel Richard Williams in 1919.

Most units of the AFC were disbanded during 1919. The AFC was succeeded by the Australian Air Corps

The Australian Air Corps (AAC) was a temporary formation of the Australian military that existed in the period between the disbandment of the Australian Flying Corps (AFC) of World War I and the establishment of the Royal Australian Air F ...

, which was itself succeeded by the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

(RAAF) in 1921. Many former members of the AFC such as Cobby, McNamara, Williams, Lawrence Wackett

Sir Lawrence James Wackett (2 January 1896 – 18 March 1982) is widely regarded as "father of the Australian aircraft industry". He has been described as "one of the towering figures in the history of Australian aviation covering, as he did, ...

, and Henry Wrigley

Air Vice Marshal Henry Neilson Wrigley, Order of the British Empire, CBE, Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom), DFC, Air Force Cross (United Kingdom), AFC (21 April 1892 – 14 September 1987) was a senior commander in the ...

, went on to play founding roles in the fledgling RAAF. Others, such as John Wright, who served with No. 4 Squadron on the Western Front before commanding the 2/15th Field Regiment in Malaya during the fighting against the Japanese in World War II, returned to a ground role.

Notes

Footnotes CitationsReferences

Books * * * * * * * * * * * * * Websites and newspapers * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

Warfare in a New Dimension: The Australian Flying Corps in the First World War

{{Wwi-air, state=collapsed Army aviation units and formations Australian military aviation Aviation in World War I British Empire in World War I Military units and formations established in 1912 Military units and formations disestablished in 1920 Military units and formations of Australia in World War I 1912 establishments in Australia Aviation history of Australia