Australia–New Zealand relations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Foreign relations between neighbouring countries Australia and

Foreign relations between neighbouring countries Australia and

The first European landing on the Australian continent occurred in the

The first European landing on the Australian continent occurred in the  Although it is accurate to distinguish that New Zealand was never a

Although it is accurate to distinguish that New Zealand was never a  New Zealand participated as a member of the

New Zealand participated as a member of the

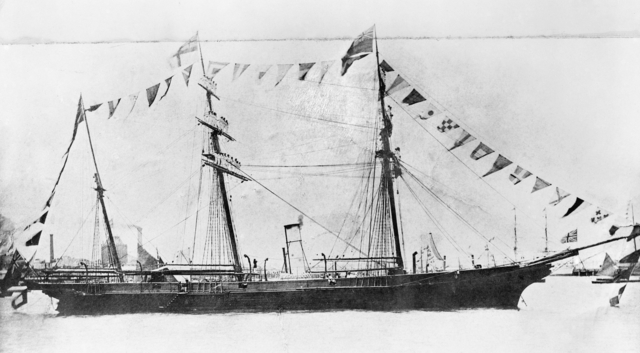

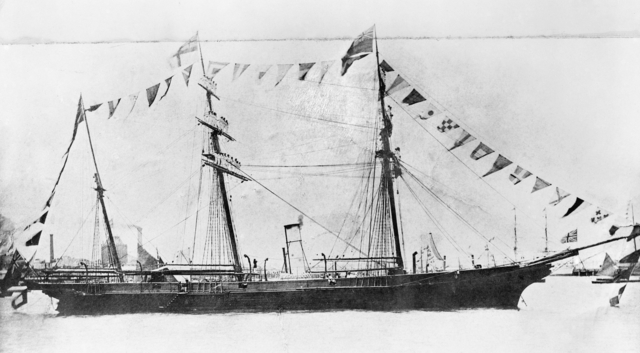

In 1861, the Australian ship HMCSS ''Victoria'' was dispatched to help the New Zealand colonial government in its war against Māori in Taranaki. ''Victoria'' was subsequently used for patrol duties and logistic support, although a number of personnel were involved in actions against Māori fortifications.Dennis et al 1995, p. 435. In late 1863, the New Zealand government requested troops to assist in the

In 1861, the Australian ship HMCSS ''Victoria'' was dispatched to help the New Zealand colonial government in its war against Māori in Taranaki. ''Victoria'' was subsequently used for patrol duties and logistic support, although a number of personnel were involved in actions against Māori fortifications.Dennis et al 1995, p. 435. In late 1863, the New Zealand government requested troops to assist in the  In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, both countries or their colonial precursors were enthusiastic members of the

In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, both countries or their colonial precursors were enthusiastic members of the  In the First World War, the soldiers of both countries were formed into the

In the First World War, the soldiers of both countries were formed into the  World War II was a major turning point for both countries, as they realised that they could no longer rely on the protection of Britain. Australia was particularly struck by this realisation, as it was directly targeted by the Empire of Japan, with Darwin bombed and Broome attacked. Subsequently, both countries sought closer ties with the United States. This resulted in the

World War II was a major turning point for both countries, as they realised that they could no longer rely on the protection of Britain. Australia was particularly struck by this realisation, as it was directly targeted by the Empire of Japan, with Darwin bombed and Broome attacked. Subsequently, both countries sought closer ties with the United States. This resulted in the

The

The

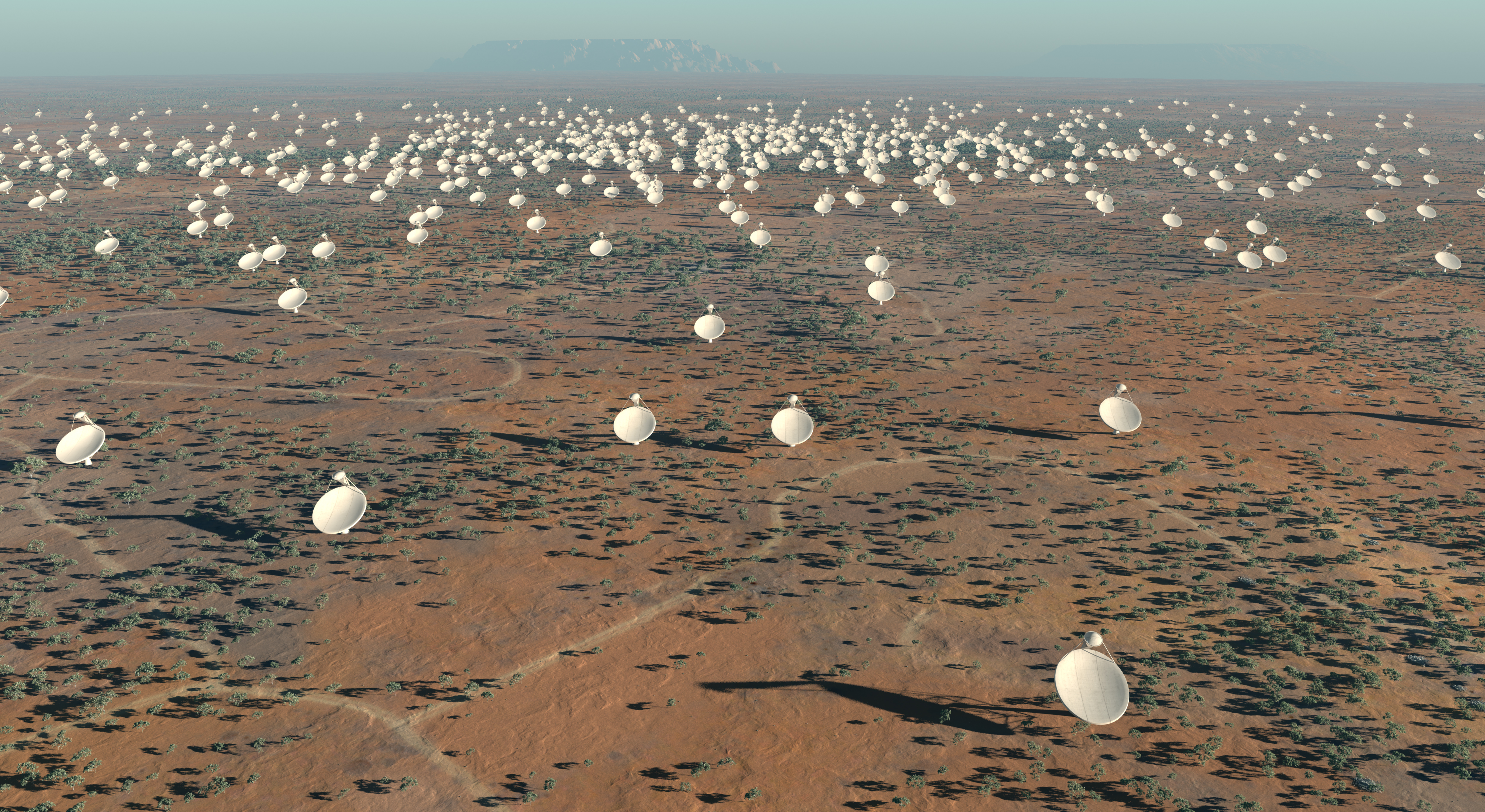

The first international cable landing on New Zealand soil was that laid in 1876 from

The first international cable landing on New Zealand soil was that laid in 1876 from

– New Zealand Cables The two countries additionally established communication via undersea laid coaxial cable in July 1962, and the NZPO- OTC joint venture TASMAN cable laid in 1975. These were retired by effect of the laying of

Under various arrangements since the 1920s, there has been a free flow of people between Australia and New Zealand. Since 1973 the informal

Under various arrangements since the 1920s, there has been a free flow of people between Australia and New Zealand. Since 1973 the informal

In December 2014,

In December 2014,

New Zealand's economic ties with Australia are strong, especially since the demise of Britain as a trading partner following the latter's decision to join the European Economic Community in 1973. Effective from 1 January 1983 the two countries concluded the Australia New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement (ANZCERTA) for the purpose of allowing each country access to the other's markets.

Two-way trade between Australia and New Zealand was NZ$26.2 billion (approximately A$24.1 billion) in 2017–18, including goods and services. New Zealand's largest exports to Australia are travel and tourism, dairy products, foodstuffs, precious metals and jewellery, and machinery. Australia's largest exports to New Zealand are travel and tourism, machinery, inorganic chemicals, vehicles, foodstuffs, and paper products.

Flowing from the implementation of the ANZCERTA:

* by agreement from 1988 there will be consultation between the respective governments as part of any variation to industry assistance measures and work towards harmonisation of common administrative procedures for

New Zealand's economic ties with Australia are strong, especially since the demise of Britain as a trading partner following the latter's decision to join the European Economic Community in 1973. Effective from 1 January 1983 the two countries concluded the Australia New Zealand Closer Economic Relations Trade Agreement (ANZCERTA) for the purpose of allowing each country access to the other's markets.

Two-way trade between Australia and New Zealand was NZ$26.2 billion (approximately A$24.1 billion) in 2017–18, including goods and services. New Zealand's largest exports to Australia are travel and tourism, dairy products, foodstuffs, precious metals and jewellery, and machinery. Australia's largest exports to New Zealand are travel and tourism, machinery, inorganic chemicals, vehicles, foodstuffs, and paper products.

Flowing from the implementation of the ANZCERTA:

* by agreement from 1988 there will be consultation between the respective governments as part of any variation to industry assistance measures and work towards harmonisation of common administrative procedures for

JAS-ANZ

has existed as the joint authority for the accreditation of

(9 August 2009) * the Joint Statement of Intent: Single Economic Market Outcome Framework issued in August 2009 and has been subsequently worked upon * the Agreement Establishing the ASEAN Australia New Zealand Free Trade Area came into force on 1 January 2010 * a business-initiated and

* a business-initiated and

sponsored first joint Australia–New Zealand Investment Conference was held in

Political conditions in the aftermath of the

Political conditions in the aftermath of the

The 1901 Australian Constitution included provisions to allow New Zealand to join Australia as its seventh state, even after the government of New Zealand had already decided against such a move. The sixth of the initial defining and covering clauses in part provides that:

The 1901 Australian Constitution included provisions to allow New Zealand to join Australia as its seventh state, even after the government of New Zealand had already decided against such a move. The sixth of the initial defining and covering clauses in part provides that:

From time to time the idea of joining Australia has been mooted, but has been ridiculed by some New Zealanders. When Australia's former opposition leader,

From time to time the idea of joining Australia has been mooted, but has been ridiculed by some New Zealanders. When Australia's former opposition leader,  Australia and New Zealand are separated by the Tasman Sea by more than . Arguing against Australian statehood, New Zealand's Premier, Sir John Hall, remarked that there were "1,200 reasons" not to join the federation.

Both countries have contributed to the sporadic discussion on a Pacific Union, although that proposal would include a much wider range of member-states than just Australia and New Zealand.

A result of the rejected 1999 Australian republican referendum was that Australians retained a common head of state with New Zealand. Whereas none of the major political parties in New Zealand have a policy of encouraging

Australia and New Zealand are separated by the Tasman Sea by more than . Arguing against Australian statehood, New Zealand's Premier, Sir John Hall, remarked that there were "1,200 reasons" not to join the federation.

Both countries have contributed to the sporadic discussion on a Pacific Union, although that proposal would include a much wider range of member-states than just Australia and New Zealand.

A result of the rejected 1999 Australian republican referendum was that Australians retained a common head of state with New Zealand. Whereas none of the major political parties in New Zealand have a policy of encouraging

The two countries and their colonial precursors have enjoyed unbroken friendly

The two countries and their colonial precursors have enjoyed unbroken friendly  Both have signed and ratified the ICCPR and its First Optional Protocol and Second Optional Protocol, the

Both have signed and ratified the ICCPR and its First Optional Protocol and Second Optional Protocol, the

File:Samuel marsden.jpg, Rev.

2010 CER Ministerial Forum: Communiqué

Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade information on New Zealand

* ttps://newzealand.embassy.gov.au/wltn/home.html Australian High Commission in New Zealand

New Zealand High Commission in Australia

New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade information on Australia

{{DEFAULTSORT:Australia-New Zealand Relations

New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, also referred to as Trans-Tasman

Trans-Tasman is an adjective used primarily to signify the relationship between Australia and New Zealand. The term refers to the Tasman Sea, which lies between the two countries. For example, ''trans-Tasman commerce'' refers to commerce betwee ...

relations, are extremely close. Both countries share a British colonial heritage as antipodean Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 192 ...

s and settler colonies, and both are part of the wider Anglosphere. New Zealand sent representatives to the constitutional conventions which led to the uniting of the six Australian colonies

The states and territories are federated administrative divisions in Australia, ruled by regional governments that constitute the second level of governance between the federal government and local governments. States are self-governing ...

but opted not to join. In the Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sou ...

and in both world wars, New Zealand soldiers fought alongside Australian soldiers

Australian(s) may refer to:

Australia

* Australia, a country

* Australians, citizens of the Commonwealth of Australia

** European Australians

** Anglo-Celtic Australians, Australians descended principally from British colonists

** Aboriginal Au ...

. In recent years the Closer Economic Relations free trade agreement

A free-trade agreement (FTA) or treaty is an agreement according to international law to form a free-trade area between the cooperating states. There are two types of trade agreements: bilateral and multilateral. Bilateral trade agreements occ ...

and its predecessors have inspired ever-converging economic integration

Economic integration is the unification of economic policies between different states, through the partial or full abolition of tariff and non-tariff restrictions on trade.

The trade-stimulation effects intended by means of economic integrati ...

. Despite some shared similarities, the cultures of Australia and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

also have their own sets of differences and there are sometimes differences of opinion which some have declared as symptomatic of sibling rivalry

Sibling rivalry is a type of competition or animosity among siblings, whether blood-related or not.

Siblings generally spend more time together during childhood than they do with parents. The sibling bond is often complicated and is influenced ...

. This often centres upon sports and in commercio-economic tensions, such as those arising from the failure of Ansett Australia

Ansett Australia was a major Australian airline group, based in Melbourne, Australia. The airline flew domestically within Australia and from the 1990s to destinations in Asia. After operating for 65 years, the airline was placed into admini ...

and those engendered by the formerly long-standing Australian ban on New Zealand apple imports.

Both countries are constitutional monarchies and Commonwealth realms – sharing the same person as the sovereign and independent head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

– with parliamentary democracies

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democracy, democratic government, governance of a sovereign state, state (or subordinate entity) where the Executive (government), executive derives its democratic legitimacy ...

based on the Westminster system. Their only land border defines the western extent of the Ross Dependency

The Ross Dependency is a region of Antarctica defined by a circular sector, sector originating at the South Pole, passing along longitudes 160th meridian east, 160° east to 150th meridian west, 150° west, and terminating at latitude 60th para ...

and eastern extent of the Australian Antarctic Territory

The Australian Antarctic Territory (AAT) is a part of East Antarctica claimed by Australia as an external territory. It is administered by the Australian Antarctic Division, an agency of the federal Department of Climate Change, Energy, the En ...

. They acknowledge two distinct maritime boundaries

A maritime boundary is a conceptual division of the Earth's water surface areas using physiographic or geopolitical criteria. As such, it usually bounds areas of exclusive national rights over mineral and biological resources,VLIZ Maritime Bound ...

conclusively delimited by the Australia–New Zealand Maritime Treaty of 2004.

In 2017, a major poll showed that New Zealand was considered Australia's "best friend", a position previously held by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

.

History

The History of Indigenous Australians is generally thought to be rich to the extent of at least 40,000–45,000 years duration, whereas PolynesianMāori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the C ...

arrived in Aotearoa/New Zealand in several waves by means of waka

Waka may refer to:

Culture and language

* Waka (canoe), a Polynesian word for canoe; especially, canoes of the Māori of New Zealand

** Waka ama, a Polynesian outrigger canoe

** Waka hourua, a Polynesian ocean-going canoe

** Waka taua, a Māori w ...

in waves roughly between 1320

Year 1320 ( MCCCXX) was a leap year starting on Tuesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

January–December

* January 20 – Duke Wladyslaw Lokietek becomes king of Poland.

* April 6 – T ...

and 1350

Year 1350 ( MCCCL) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

January–December

* January 9 – Giovanni II Valente becomes Doge of Genoa.

* May 23 (possible date) ...

. Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

and Polynesian Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the C ...

indigenous to New Zealand are not recorded to have met or interacted prior to 17th and 18th century European exploration of Australia

The European exploration of Australia first began in February 1606, when Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon landed in Cape York Peninsula and on October that year when Spanish explorer Luís Vaz de Torres sailed through, and navigated, Torres Stra ...

. Regarding the respective indigenous populations, while it may be said that there is a single Māori language and the iwi

Iwi () are the largest social units in New Zealand Māori society. In Māori roughly means "people" or "nation", and is often translated as "tribe", or "a confederation of tribes". The word is both singular and plural in the Māori language, ...

have been able to present as a unified population represented by a monarch neither has ever been able to be said of the Australian Aboriginal languages or their corresponding population groups.

Janszoon voyage of 1605–06

Willem Janszoon captained the first recorded European landing on the Australian continent in 1606, sailing from Bantam, Java, in the ''Duyfken''. As an employee of the Dutch East India Company ( nl, Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC), J ...

. Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first known European explorer to reach New ...

in two distinct voyages in the period 1642–1644 is recorded as the first person to have coastally explored regions of the respective landforms including Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sep ...

– later named for him as the Australian state of Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

. The first voyage of James Cook

The first voyage of James Cook was a combined Royal Navy and Royal Society expedition to the south Pacific Ocean aboard HMS ''Endeavour'', from 1768 to 1771. It was the first of three Pacific voyages of which James Cook was the commander. The ...

stands as significant for the circumnavigation of New Zealand in 1769 and as the European discovery and first ever coastal navigation of Eastern Australia from April to August 1770. The European settlement of Australia and New Zealand, then referred to as the colony of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, dates from the arrival of the First Fleet into Cadi/Port Jackson

Port Jackson, consisting of the waters of Sydney Harbour, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and the Lane Cove and Parramatta Rivers, is the ria or natural harbour of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The harbour is an inlet of the Tasman Sea ...

on Australia Day

Australia Day is the official national day of Australia. Observed annually on 26 January, it marks the 1788 landing of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove and raising of the Union Flag by Arthur Phillip following days of exploration of Port ...

, 1788.

New Zealand was separated from the Colony of New South Wales in 1840, at which time its pākehā

Pākehā (or Pakeha; ; ) is a Māori term for New Zealanders primarily of European descent. Pākehā is not a legal concept and has no definition under New Zealand law. The term can apply to fair-skinned persons, or to any non- Māori New Z ...

population numbered about 2000 descended from Christian missionaries, sealers Sealer may refer either to a person or ship engaged in seal hunting, or to a sealant; associated terms include:

Seal hunting

* Sealer Hill, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica

* Sealers' Oven, bread oven of mud and stone built by sealers around 18 ...

, and whalers (as opposed to mainland Australia's much larger penal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

population).

Although it is accurate to distinguish that New Zealand was never a

Although it is accurate to distinguish that New Zealand was never a penal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

, neither were some of the Australian colonies. In particular, South Australia was founded and settled in a similar manner to New Zealand, both being influenced by the ideas of Edward Gibbon Wakefield

Edward Gibbon Wakefield (20 March 179616 May 1862) is considered a key figure in the establishment of the colonies of South Australia and New Zealand (where he later served as a member of parliament). He also had significant interests in Brit ...

.

Both countries experienced ongoing internal conflict concerning indigenous and settler populations, although this conflict took very different forms most sharply manifested in the New Zealand Wars

The New Zealand Wars took place from 1845 to 1872 between the New Zealand colonial government and allied Māori on one side and Māori and Māori-allied settlers on the other. They were previously commonly referred to as the Land Wars or the ...

and Australian frontier wars respectively. Whereas Maori iwi endured the Musket Wars

The Musket Wars were a series of as many as 3,000 battles and raids fought throughout New Zealand (including the Chatham Islands) among Māori between 1807 and 1837, after Māori first obtained muskets and then engaged in an intertribal arms rac ...

of the period 1807–1839 preceding the former in New Zealand, indigenous Australians have no comparable period of the experience of warfare amongst each other employing European-introduced modern weaponry either before or after their own confrontations with European settler society. Both countries experienced nineteenth century gold rushes and during the nineteenth century there was extensive trade and travel between the colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

.

New Zealand participated as a member of the

New Zealand participated as a member of the Federal Council of Australasia

The Federal Council of Australasia was a forerunner to the current Commonwealth of Australia, though its structure and members were different.

The final (and successful) push for the Federal Council came at a "Convention" on 28 November 1883, whic ...

from 1885 and fully involved itself among the other self-governing colonies

In the British Empire, a self-governing colony was a colony with an elected government in which elected rulers were able to make most decisions without referring to the colonial power with nominal control of the colony. This was in contrast to a ...

in the 1890 conference and 1891 Convention leading up to Federation of Australia. Ultimately it declined to accept the invitation to join the Commonwealth of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

resultingly formed in 1901, remaining as a self-governing colony

In the British Empire, a self-governing colony was a colony with an elected government in which elected rulers were able to make most decisions without referring to the colonial power with nominal control of the colony. This was in contrast to ...

until becoming the Dominion of New Zealand in 1907 and with other territories later constituting the Realm of New Zealand

The Realm of New Zealand consists of the entire area in which the monarch of New Zealand functions as head of state. The realm is not a federation; it is a collection of states and territories united under its monarch. New Zealand is an indep ...

effectively as an independent country of its own. In the 1908 Olympics, the 1911 Festival of Empire

The 1911 Festival of Empire was the biggest single event held at The Crystal Palace in London since its opening. It opened on 12 May and was one of the events to celebrate the coronation of King George V. The original intention had been that Edw ...

and the 1912 Olympics

The 1912 Summer Olympics ( sv, Olympiska sommarspelen 1912), officially known as the Games of the V Olympiad ( sv, Den V olympiadens spel) and commonly known as Stockholm 1912, were an international multi-sport event held in Stockholm, Sweden, b ...

the two countries were represented at least in sporting competition as the unified entity "Australasia

Australasia is a region that comprises Australia, New Zealand and some neighbouring islands in the Pacific Ocean. The term is used in a number of different contexts, including geopolitically, physiogeographically, philologically, and ecologi ...

".

Both continued to co-operate politically in the 20th century as each sought closer relations with the United Kingdom, particularly in the area of trade. This was helped by the development of refrigerated shipping, which allowed New Zealand in particular to base its economy on the export of meat and dairy – both of which Australia had in abundance – to Britain.

The two nations sealed the Canberra Pact in January 1944 for the purpose of successfully prosecuting war against the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

in World War II and providing for the administration of an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

and territorial trusteeship in its aftermath. The Agreement foreshadowed the establishment of a permanent Australia–New Zealand Secretariat, it provided for consultation in matters of common interest, it provided for the maintenance of separate military commands and for "the maximum degree of unity in the presentation ... of the views of the two countries".

The quantity of trans-Tasman trade increased by 9% per annum from the early 1980s through to the end of 2007, with the Closer Economic Relations free trade agreement

A free-trade agreement (FTA) or treaty is an agreement according to international law to form a free-trade area between the cooperating states. There are two types of trade agreements: bilateral and multilateral. Bilateral trade agreements occ ...

of 1983 being a major turning point. This was partially a result of Britain joining the European Economic Community in the early 1970s, thus restricting the access of both countries to their biggest export market.

Military

In the Harriet Affair of 1834, a group of British soldiers of the 50th Regiment from Australia landed inTaranaki

Taranaki is a region in the west of New Zealand's North Island. It is named after its main geographical feature, the stratovolcano of Mount Taranaki, also known as Mount Egmont.

The main centre is the city of New Plymouth. The New Plymouth D ...

, New Zealand, to rescue the wife and children of John (Jacky) Guard and punish the kidnappers – the first clash between Māori and British troops. The expedition was sent by Governor Bourke from Sydney and was subsequently criticised by a British House of Commons report in 1835 for use of excessive force.

In 1861, the Australian ship HMCSS ''Victoria'' was dispatched to help the New Zealand colonial government in its war against Māori in Taranaki. ''Victoria'' was subsequently used for patrol duties and logistic support, although a number of personnel were involved in actions against Māori fortifications.Dennis et al 1995, p. 435. In late 1863, the New Zealand government requested troops to assist in the

In 1861, the Australian ship HMCSS ''Victoria'' was dispatched to help the New Zealand colonial government in its war against Māori in Taranaki. ''Victoria'' was subsequently used for patrol duties and logistic support, although a number of personnel were involved in actions against Māori fortifications.Dennis et al 1995, p. 435. In late 1863, the New Zealand government requested troops to assist in the invasion of the Waikato

The Invasion of the Waikato became the largest and most important campaign of the 19th-century New Zealand Wars. Hostilities took place in the North Island of New Zealand between the military forces of the colonial government and a federatio ...

. Promised settlement on confiscated land, more than 2500 Australians were recruited. Other Australians became scouts in the Company of Forest Rangers. Australians were involved in actions at Matarikoriko, Pukekohe East

Pukekohe is a town in the Auckland Region of the North Island of New Zealand. Located at the southern edge of the Auckland Region, it is in South Auckland, between the southern shore of the Manukau Harbour and the mouth of the Waikato River. ...

, Titi Hill, Ōrākau and Te Ranga.

In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, both countries or their colonial precursors were enthusiastic members of the

In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, both countries or their colonial precursors were enthusiastic members of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

and both either sent soldiers or permitted the sending of military volunteer

A military volunteer (or ''war volunteer'') is a person who enlists in military service by free will, and is not a conscript, mercenary, or a foreign legionnaire. Volunteers sometimes enlist to fight in the armed forces of a foreign country, fo ...

s to the Mahdist War in the Sudan, the quelling of the Boxer Rebellion, the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

, the First and Second World Wars and the Malayan Emergency and Konfrontasi. Independent of the sense of Empire (or Commonwealth), both nations in the second half of the twentieth century otherwise provided contingents in support of United States strategic aims in the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

, and Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a Coalition of the Gulf War, 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Ba'athist Iraq, ...

. Whereas military personnel from both countries participated in UNTSO

The United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO) is an organization founded on 29 May 1948 for peacekeeping in the Middle East. Established amidst the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, its primary task was initially to provide the military com ...

, the Multinational Force and Observers

The Multinational Force and Observers (MFO) is an international peacekeeping force overseeing the terms of the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel. The MFO generally operates in and around the Sinai peninsula, ensuring free navigation through ...

to Sinai, INTERFET

The International Force East Timor (INTERFET) was a multinational non-United Nations peacemaking task force, organised and led by Australia in accordance with United Nations resolutions to address the humanitarian and security crisis that took ...

to East Timor

East Timor (), also known as Timor-Leste (), officially the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, is an island country in Southeast Asia. It comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, the exclave of Oecusse on the island's north-west ...

, the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands

The Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI), also known as Operation Helpem Fren, Operation Anode and Operation Rata (by New Zealand), was created in 2003 in response to a request for international aid by the Governor-General of ...

, UNMIS to Sudan, and more recent intervention in Tonga the New Zealand government officially condemned the 2003 invasion of Iraq

The 2003 invasion of Iraq was a United States-led invasion of the Republic of Iraq and the first stage of the Iraq War. The invasion phase began on 19 March 2003 (air) and 20 March 2003 (ground) and lasted just over one month, including 26 ...

and stood apart from Australia in refusing to contribute any combat forces. Somewhat similarly in 1982, although without speaking in condemnation, Australia found no purpose in joining with New Zealand to support the United Kingdom in the Falklands War against Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

just as New Zealand had declined to join Australia in Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War

Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War or Allied Powers intervention in the Russian Civil War consisted of a series of multi-national military expeditions which began in 1918. The Allies first had the goal of helping the Czechoslovak Leg ...

or in UNEF to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

and Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

during the 1970s.

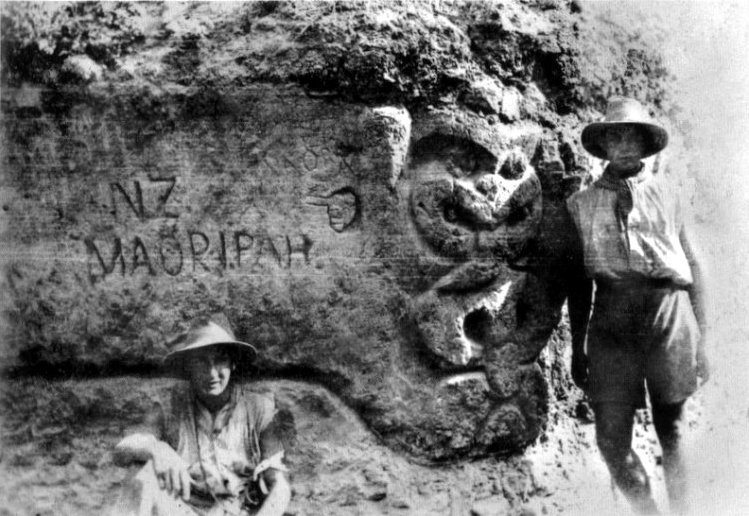

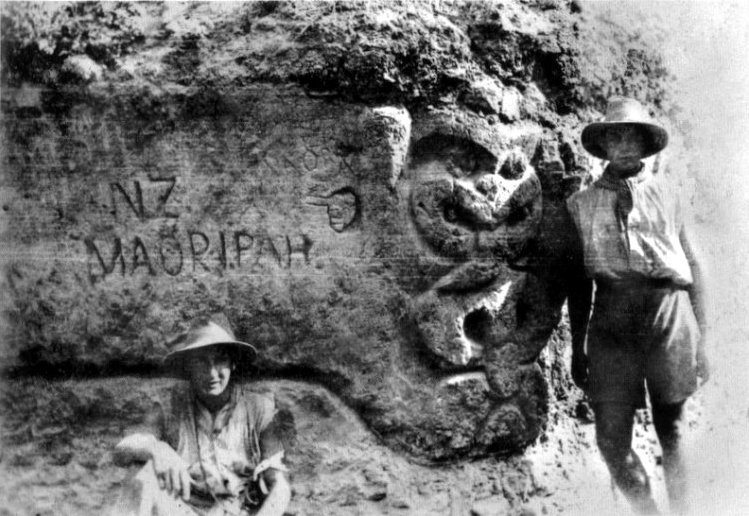

In the First World War, the soldiers of both countries were formed into the

In the First World War, the soldiers of both countries were formed into the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. It was formed in Egypt in December 1914, and operated during the Gallipoli campaign. General William Birdwood com ...

(ANZACs). Together Australia and New Zealand saw their first major military action in the Battle of Gallipoli, in which both suffered major casualties. For many decades the battle was seen by both countries as the moment at which they came of age as nations. It continues to be commemorated annually in both countries on Anzac Day, although since the 1960s there has been some questioning of the "coming of age" idea.

World War II was a major turning point for both countries, as they realised that they could no longer rely on the protection of Britain. Australia was particularly struck by this realisation, as it was directly targeted by the Empire of Japan, with Darwin bombed and Broome attacked. Subsequently, both countries sought closer ties with the United States. This resulted in the

World War II was a major turning point for both countries, as they realised that they could no longer rely on the protection of Britain. Australia was particularly struck by this realisation, as it was directly targeted by the Empire of Japan, with Darwin bombed and Broome attacked. Subsequently, both countries sought closer ties with the United States. This resulted in the ANZUS

The Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty (ANZUS or ANZUS Treaty) is a 1951 non-binding collective security agreement between Australia and New Zealand and, separately, Australia and the United States, to co-operate on militar ...

pact of 1951, in which Australia, New Zealand and the United States agreed to defend each other in the event of enemy attack. Although no such attack occurred until, arguably, 11 September 2001

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commer ...

, Australia and New Zealand both contributed troops to the Korean

Korean may refer to:

People and culture

* Koreans, ethnic group originating in the Korean Peninsula

* Korean cuisine

* Korean culture

* Korean language

**Korean alphabet, known as Hangul or Chosŏn'gŭl

**Korean dialects and the Jeju language

** ...

and Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

s. Australia's contribution to the Vietnam War in particular was much larger than New Zealand's

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island country b ...

; while Australia introduced conscription, New Zealand sent only a token force. Australia has continued to be more committed to the American alliance, ANZUS

The Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty (ANZUS or ANZUS Treaty) is a 1951 non-binding collective security agreement between Australia and New Zealand and, separately, Australia and the United States, to co-operate on militar ...

, than New Zealand; although both countries felt considerable unease about American military policy in the 1980s, New Zealand angered the United States by refusing port access to nuclear ships into its nuclear-free zone from 1985 and in retaliation, the United States 'suspended' its obligations otherwise owed under the alliance treaty to New Zealand. Australia has made a significant contribution to the Iraq War, while New Zealand's much smaller military contribution was limited to UN-authorised reconstruction tasks.

Anzac Bridge

The Anzac Bridge is an eight-lane cable-stayed bridge that carries the Western Distributor (A4) across Johnstons Bay between Pyrmont and Glebe Island (part of the suburb of Rozelle), on the western fringe of the central business district of ...

in Sydney was given its current name on Remembrance Day

Remembrance Day (also known as Poppy Day owing to the tradition of wearing a remembrance poppy) is a memorial day observed in Commonwealth member states since the end of the First World War to honour armed forces members who have died in t ...

in 1998 to honour the memory of the ANZAC serving in World War I. An Australian flag

The flag of Australia, also known as the Australian Blue Ensign, is based on the British Blue Ensign—a blue field with the Union Jack in the upper hoist quarter—augmented with a large white seven-pointed star (the Commonwealth Star) and a r ...

flies atop the eastern pylon and a New Zealand flag flies atop the western pylon. A bronze memorial statue of a digger holding a Lee–Enfield

The Lee–Enfield or Enfield is a bolt-action, magazine-fed repeating rifle that served as the main firearm of the military forces of the British Empire and Commonwealth during the first half of the 20th century, and was the British Army's sta ...

rifle pointing down was placed on the western end of the bridge on Anzac Day in 2000. A statue of a New Zealand soldier was added to a plinth across the road from the Australian Digger, facing towards the east, and unveiled by Prime Minister of New Zealand

The prime minister of New Zealand ( mi, Te pirimia o Aotearoa) is the head of government of New Zealand. The prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, leader of the New Zealand Labour Party, took office on 26 October 2017.

The prime minister (inform ...

Helen Clark

Helen Elizabeth Clark (born 26 February 1950) is a New Zealand politician who served as the 37th prime minister of New Zealand from 1999 to 2008, and was the administrator of the United Nations Development Programme from 2009 to 2017. She was ...

in the presence of Premier of New South Wales

The premier of New South Wales is the head of government in the state of New South Wales, Australia. The Government of New South Wales follows the Westminster Parliamentary System, with a Parliament of New South Wales acting as the legislatu ...

Morris Iemma

Morris Iemma (; born 21 July 1961) is a former Australian politician who was the 40th Premier of New South Wales. He served from 3 August 2005 to 5 September 2008. From Sydney, Iemma attended the University of Sydney and the University of Techno ...

on Sunday 27 April 2008.

In 2001 the Australia–New Zealand Memorial was opened by the prime ministers of both countries on Anzac Parade, Canberra. The memorial commemorates the shared effort to achieve common goals in both peace and war.

Joint defence arrangements involving both countries include the Five Power Defence Arrangements

The Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA) are a series of bilateral defence relationships established by a series of multi-lateral agreements between Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and the United Kingdom, all of which are Commonwe ...

, ANZUS

The Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty (ANZUS or ANZUS Treaty) is a 1951 non-binding collective security agreement between Australia and New Zealand and, separately, Australia and the United States, to co-operate on militar ...

, and the UK-USA Security Agreement

The United Kingdom – United States of America Agreement (UKUSA, ) is a multilateral agreement for cooperation in signals intelligence between Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The alliance of intellig ...

for intelligence sharing. Since 1964, Australia, and since 2006, New Zealand have been parties to the ABCA interoperability arrangement of national defence forces. ANZUK was a tripartite force formed by Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom to defend the Asian Pacific region after the United Kingdom withdrew forces from the east of Suez in the early seventies. The ANZUK force was formed in 1971 and disbanded in 1974. The SEATO

The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was an international organization for collective defense in Southeast Asia created by the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, or Manila Pact, signed in September 1954 in Manila, the Philipp ...

anti-communist defence organisation also extended membership to both countries for the duration of its existence from 1955 to 1977.

Exploration

The

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition was a 1911–1914 expedition headed by Douglas Mawson that explored the largely uncharted Antarctic coast due south of Australia. Mawson had been inspired to lead his own venture by his experiences on Ernest ...

1911–1914 established radio connection back to Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

via Macquarie Island

Macquarie Island is an island in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, about halfway between New Zealand and Antarctica. Regionally part of Oceania and politically a part of Tasmania, Australia, since 1900, it became a Tasmanian State Reserve in 197 ...

, surveyed King George V Land and examined the rock formations of Wilkes Land

Wilkes Land is a large district of land in eastern Antarctica, formally claimed by Australia as part of the Australian Antarctic Territory, though the validity of this claim has been placed for the period of the operation of the Antarctic Treaty ...

. Mawson's Huts

Mawson's Huts are the collection of buildings located at Cape Denison, Commonwealth Bay, in the far eastern sector of the Australian Antarctic Territory, some 3000 km south of Hobart. The buildings were erected and occupied by the Australas ...

at Cape Denison survive to the current day as habitations at the expedition's chosen base. The expedition's Western Base Party made a number of discoveries and explored into Kaiser Wilhelm II Land

Kaiser Wilhelm II Land is a part of Antarctica lying between Cape Penck at 87° 43'E and Cape Filchner at 91° 54'E. Princess Elizabeth Land is located to the west, and Queen Mary Land to the east. The area is claimed by Australia ...

from initial stationing in Queen Mary Land. The territorially acquisitive BANZARE expedition of 1929–1931, additionally collaborating with the UK, mapped the coastline of Antarctica and discovered Mac Robertson Land and Princess Elizabeth Land

Princess Elizabeth Land is the sector of Antarctica between longitude 73° east and Cape Penck (at 87°43' east). The sector is claimed by Australia as part of the Australian Antarctic Territory, although this claim is not widely recognized.

...

. Both expeditions reported voluminously.

Aerial crossing of the Tasman was first achieved by Charles Kingsford Smith

Sir Charles Edward Kingsford Smith (9 February 18978 November 1935), nicknamed Smithy, was an Australian aviation pioneer. He piloted the first transpacific flight and the first flight between Australia and New Zealand.

Kingsford Smith was b ...

with Charles Ulm and crew travelling by return journey in 1928, improving upon failure by Moncrieff and Hood deceased earlier the same year. Guy Menzies then completed solo crossing in 1931. Rowing crossing was first successfully completed, solo, by Colin Quincey in 1977 and then by teams of kayakers in 2007. A pioneering solo kayak journey from Tasmania by Andrew McAuley in early 2007 ended with his disappearance at sea and presumed death in New Zealand waters 30 nmi short of landfall at Milford Sound

Milford Sound / Piopiotahi is a fiord in the south west of New Zealand's South Island within Fiordland National Park, Piopiotahi (Milford Sound) Marine Reserve, and the Te Wahipounamu World Heritage site. It has been judged the world's top t ...

.

Telecommunications

La Perouse, New South Wales

La Perouse is a suburb in south-eastern Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. The suburb of La Perouse is located about southeast of the Sydney central business district, in the City of Randwick.

The La Perouse peninsula is the n ...

to Wakapuaka, New Zealand. The major part of that cable was renewed in 1895 and it was withdrawn from service in 1932. A second trans-Tasman submarine cable Submarine cable is any electrical cable that is laid on the seabed, although the term is often extended to encompass cables laid on the bottom of large freshwater bodies of water.

Examples include:

*Submarine communications cable

*Submarine power ...

was laid in 1890 between Sydney and Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by metr ...

, New Zealand and then in 1901 the Pacific Cable from Norfolk Island was landed in Doubtless Bay, North Island. In 1912 a cable was laid from Sydney to Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about ...

.History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications from the first submarine cable of 1850 to the worldwide fiber optic network– New Zealand Cables The two countries additionally established communication via undersea laid coaxial cable in July 1962, and the NZPO- OTC joint venture TASMAN cable laid in 1975. These were retired by effect of the laying of

analogue signal

An analog signal or analogue signal (see spelling differences) is any continuous signal representing some other quantity, i.e., ''analogous'' to another quantity. For example, in an analog audio signal, the instantaneous signal voltage varies ...

submarine cable linking Australia's Bondi Beach to Takapuna, New Zealand via Norfolk Island in 1983, which itself in turn was supplemented and eventually outmoded by the TASMAN-2 optical fibre cable

A fiber-optic cable, also known as an optical-fiber cable, is an assembly similar to an electrical cable, but containing one or more optical fibers that are used to carry light. The optical fiber elements are typically individually coated with ...

laid between Paddington, New South Wales

Paddington is an upscale inner-city area of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Located east of the Sydney central business district, Paddington lies across two local government areas. The portion south of Oxford Street lie ...

and Whenuapai, Auckland in 1995.

The trans-Tasman leg of the high capacity fibre-optic Southern Cross Cable

The Southern Cross Cable is a trans-Pacific network of telecommunications cables commissioned in 2000. The network is operated by the Bermuda-registered company ''Southern Cross Cables Limited''.

The network has 28,900 km of submarine an ...

has been operational from Alexandria, New South Wales to Whenuapai since 2001. Another high capacity direct linkage was proposed for construction to be operational in 2013, and yet another for early 2014. A 2288 km fibre optic cable went live in March 2017: the Tasman Global Access cable from Ngarunui Beach in Raglan to Narrabeen

Narrabeen is a beachside suburb in northern Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Narrabeen is 23 kilometres north-east of the Sydney central business district, in the local government area of Northern Beaches Council and is ...

Beach in Sydney.

Migration

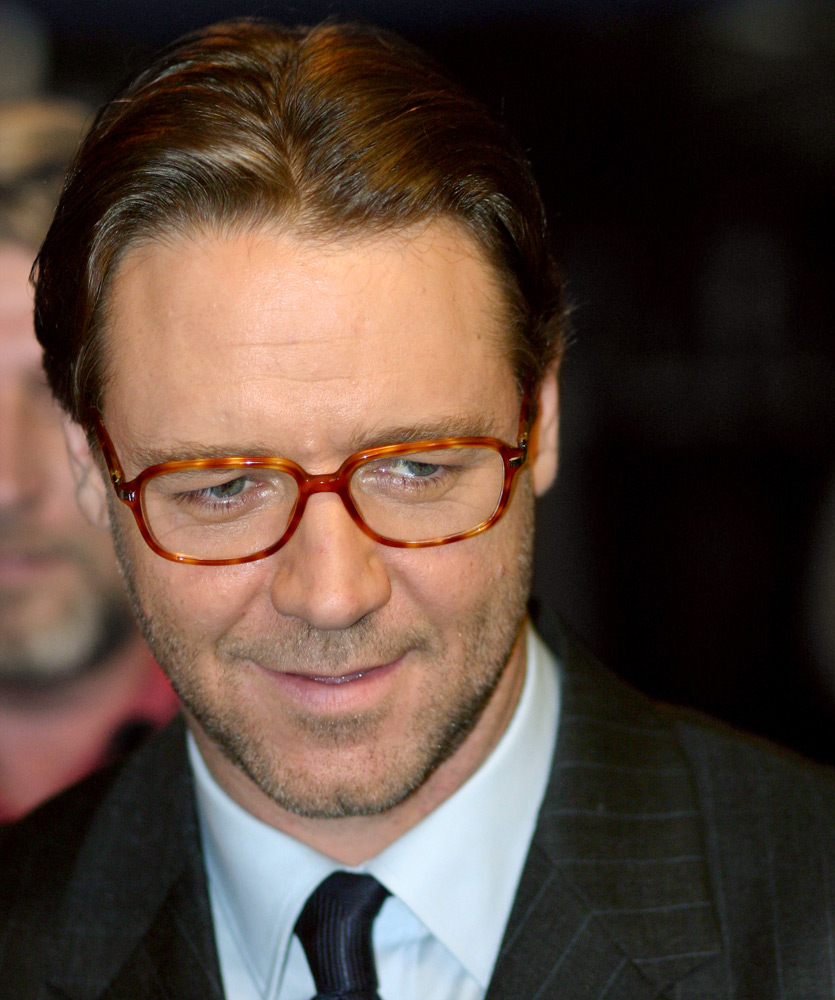

Trans-Tasman migration and connections

There are many people who have emigrated from New Zealand to Australia, including formerPremier of South Australia

The premier of South Australia is the head of government in the state of South Australia, Australia. The Government of South Australia follows the Westminster system, with a Parliament of South Australia acting as the legislature. The premier is ...

, Mike Rann

Michael David Rann, , (born 5 January 1953) is an Australian former politician who was the 44th premier of South Australia from 2002 to 2011. He was later Australian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom from 2013 to 2014, and Australian am ...

, comedian turned psychologist Pamela Stephenson

Pamela Helen Stephenson, Lady Connolly (born 4 December 1949) is a New Zealand-born psychologist, writer, and performer who is now a resident in both the United Kingdom and the United States. She is best known for her work as an actress and co ...

and actor Russell Crowe. Australians who have emigrated to New Zealand include the 17th and 23rd Prime Ministers of New Zealand Sir Joseph Ward and Michael Joseph Savage

Michael Joseph Savage (23 March 1872 – 27 March 1940) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 23rd prime minister of New Zealand, heading the First Labour Government from 1935 until his death in 1940.

Savage was born in the Colon ...

, Russel Norman

Russel William Norman (born 2 June 1967) is a New Zealand politician and environmentalist. He was a Member of Parliament and co-leader of the Green Party. Norman resigned as an MP in October 2015 to work as Executive Director of Greenpeace Aote ...

, former co-leader of the Green Party

A green party is a formally organized political party based on the principles of green politics, such as social justice, environmentalism and nonviolence.

Greens believe that these issues are inherently related to one another as a foundation f ...

, and Matt Robson

Matthew Peter Robson (born 5 January 1950) is a New Zealand politician. He was deputy leader of the Progressive Party, and served in the Parliament from 1996 to 2005, first as a member of the Alliance, then as a Progressive.

Early years

Robson ...

, former deputy leader of the Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

.

Under various arrangements since the 1920s, there has been a free flow of people between Australia and New Zealand. Since 1973 the informal

Under various arrangements since the 1920s, there has been a free flow of people between Australia and New Zealand. Since 1973 the informal Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement

The Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement (TTTA) is an arrangement between Australia and the Realm of New Zealand which allows for the free movement of citizens of one of these countries to the other. The arrangement came into effect in 1973, and all ...

has allowed for the free movement of citizens of one nation to the other. The only major exception to these travel privileges is for individuals with outstanding warrants or criminal backgrounds who are deemed dangerous or undesirable for the migrant nation and its citizens. New Zealand passport holders are issued with special category visa

A Special Category Visa (SCV) is an Australian visa category (subclass 444) granted to most New Zealand citizens on arrival in Australia, enabling them to visit, study, stay and work in Australia indefinitely under the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrang ...

s on arrival in Australia, while Australian passport holders are issued with residence class visas on arrival in New Zealand.

In recent decades, many New Zealanders have migrated to Australian cities such as Sydney, Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Queensland, and the third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of approximately 2.6 million. Brisbane lies at the centre of the South ...

, Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

and Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth i ...

. Many such New Zealanders are Māori Australians. Although this agreement is reciprocal there has been resulting significant net migration from New Zealand to Australia. In 2001 there were eight times more New Zealanders living in Australia than Australians living in New Zealand, and in 2006 it was estimated that Australia's real income per person was 32 per cent higher than that of New Zealand and its territories. Comparative surveys of median household incomes also confirm that those incomes are lower in New Zealand than in most of the Australian States and Territories. Visits in each direction exceeded one million in 2009, and there are around half a million New Zealand citizens in Australia and about 65,000 Australians in New Zealand. There have been complaints in New Zealand that there is a clearly manifested brain drain to Australia.

2001 Australian immigration policy changes

New Zealanders in Australia previously had immediate access to Australian welfare benefits and were sometimes characterised as bludgers. In 2001 this was described by New Zealand Prime MinisterHelen Clark

Helen Elizabeth Clark (born 26 February 1950) is a New Zealand politician who served as the 37th prime minister of New Zealand from 1999 to 2008, and was the administrator of the United Nations Development Programme from 2009 to 2017. She was ...

as a "modern myth". Regulations changed in 2001 whereby New Zealanders must wait two years before being eligible for such payments. All New Zealanders who have moved to Australia after February 2001 are placed on a Special Category Visa

A Special Category Visa (SCV) is an Australian visa category (subclass 444) granted to most New Zealand citizens on arrival in Australia, enabling them to visit, study, stay and work in Australia indefinitely under the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrang ...

, classing them as ''temporary residents'', regardless of how long they reside in Australia. This visa is also passed on to their children. As temporary residents, they are ineligible for government support, student loans, aid, emergency programmes, welfare, public housing and disability support in Australia.

As part of the stricter immigration regulations in 2001, New Zealanders must also acquire permanent residency before applying for Australian citizenship. These stricter immigration requirements have led to a drop in New Zealanders acquiring Australian citizenship. By 2016, only 8.4 per cent of the 146,000 New Zealand–born migrants who arrived in Australia between 2002 and 2011 had acquired Australian citizenship. Of this number, only 3 per cent of New Zealand–born Māori had acquired Australian citizenship. The Victoria University of Wellington

Victoria University of Wellington ( mi, Te Herenga Waka) is a university in Wellington, New Zealand. It was established in 1897 by Act of Parliament, and was a constituent college of the University of New Zealand.

The university is well kno ...

researcher Paul Hamer claimed that the 2001 changes was part of an Australian policy of filtering out Pacific Islander

Pacific Islanders, Pasifika, Pasefika, or rarely Pacificers are the peoples of the Pacific Islands. As an ethnic/racial term, it is used to describe the original peoples—inhabitants and diasporas—of any of the three major subregions of O ...

migrants who had acquired New Zealand citizenship and were perceived to be exploiting a "backdoor access" to Australia. Between 2009 and 2016, there was a 42 per cent increase in New Zealand–born prisoners in Australian prisons.

Attempts by the Queensland Government to pass a law that would allow government agencies to deny support based on residency status without it being considered discriminatory were condemned by Queensland's anti-discrimination commission as an attempt to legalise state discrimination against New Zealanders, claiming it would create a "permanent second class of people". Children born to Australians in New Zealand are granted New Zealand citizenship by birth as well as Australian citizenship by descent.

New Zealand Ministry of Education

The Ministry of Education ( Māori: ''Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga'') is the public service department of New Zealand charged with overseeing the New Zealand education system.

The Ministry was formed in 1989 when the former, all-encompassing D ...

figures show the number of Australians at New Zealand tertiary institutions almost doubled from 1,978 students in 1999 to 3,916 in 2003. In 2004 more than 2700 Australians received student loans and 1220 a student allowance. Unlike other overseas students, Australians pay the same fees for higher education as New Zealanders, and are eligible for student loans and allowances once they have lived in New Zealand for two years. New Zealand students are not treated on the same basis as Australian students in Australia.

Persons born in New Zealand continue to be the second largest source of immigration to Australia

The Australian continent was first settled when ancestors of Indigenous Australians arrived via the islands of Maritime Southeast Asia and New Guinea over 50,000 years ago.

European colonisation began in 1788 with the establishment of a ...

, representing 11% of total permanent additions in 2005–06 and accounting for 2.3% of Australia's population in June 2006. At 30 June 2010, an estimated 566,815 New Zealand citizens were present in Australia.

Section 501 "character test"

In December 2014,

In December 2014, Peter Dutton

Peter Craig Dutton (born 18 November 1970) is an Australian politician who has been leader of the opposition and leader of the Liberal Party since May 2022. He has represented the Queensland seat of Dickson in the House of Representatives sinc ...

assumed the portfolio of Australian Minister for Immigration and Border Protection

The Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs is a ministerial post of the Australian Government and is currently held by Andrew Giles, pending the swearing in of the full Albanese ministry on 1 June 2022, following the ...

following a cabinet reshuffle. That same month, the Australian Government amended the Migration Act 1958

The ''Migration Act 1958'' (Cth) is an Act of the Parliament of Australia that governs immigration to Australia. It set up Australia’s universal visa system (or entry permits). Its long title is "An Act relating to the entry into, and pres ...

that facilitates the cancellation of Australian visas for non-citizens who have served for more than twelve months in an Australian prison or if immigration authorities believe that they pose a threat to the country. This stricter character test also targets non-citizens who have lived in Australia for most of their lives and have family there. As of July 2018, about 1,300 New Zealanders have been deported since January 2015 under the new section 501 "character test." Refusal or cancellation of visa on character grounds. Of the deported New Zealanders, at least 60 per cent were of Māori and Pacific Islander ethnicity. While Australian officials have justified the deportations on law and order grounds, New Zealand officials have contended that such measures damage the "historic bonds of mateship" between the two countries.

Following a meeting between New Zealand Prime Minister John Key

Sir John Phillip Key (born 9 August 1961) is a New Zealand retired politician who served as the 38th Prime Minister of New Zealand from 2008 to 2016 and as Leader of the New Zealand National Party from 2006 to 2016. After resigning from bo ...

and Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott

Anthony John Abbott (; born 4 November 1957) is a former Australian politician who served as the 28th prime minister of Australia from 2013 to 2015. He held office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Abbott was born in Londo ...

in February 2015, the Australian Government agreed to give New Zealand more advance warning about the repatriation of deported criminals so that NZ authorities could better manage "at risk" deportees. In October 2015, Abbott's successor Malcolm Turnbull

Malcolm Bligh Turnbull (born 24 October 1954) is an Australian former politician and businessman who served as the 29th prime minister of Australia from 2015 to 2018. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Turnbull grad ...

reached an agreement with Key to allow New Zealanders detained at Australian immigration detention centres to fly home while they appealed their visa applications and to fast-track the application process. The Fifth National Government also passed legislation in November 2015 to establish a strict monitoring regime for those returned under section 501, which reduced recidivism rates from 58% in November 2015 to 38% by March 2018.

In February 2016, Turnbull and Key reached an agreement to give New Zealanders in Australia a pathway to citizenship if they had been earning above the average wage for five years. In July 2017, the Australian Government introduced the "Skilled Independent visa (subclass 189)" which allows New Zealanders who have been Australian residents for five years to apply for citizenship after 12 months. The visa also requires applicants to maintain an annual income over A$53,900 and gives New Zealanders more access to welfare services. Between 60,000 and 80,000 New Zealanders are eligible for the new visa. This new visa reflected a policy shift to prioritise non-citizen New Zealanders residing in Australian over Asian migrants from overseas. According to figures from the Australian Home Affairs Department

The Home Affairs Department is an executive agency in the government of Hong Kong responsible for internal affairs of the territory. It reports to the Home and Youth Affairs Bureau, headed by the Secretary for Home Affairs.

Purpose

The D ...

obtained by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) is the national broadcaster of Australia. It is principally funded by direct grants from the Australian Government and is administered by a government-appointed board. The ABC is a publicly-own ...

(ABC), 1,512 skilled independent visas had been issued by late February 2018 with another 7,500 visas still being processed. Australian Greens immigration spokesperson Nick McKim

Nicholas James McKim (born 11 June 1965) is an Australian politician, currently a member of the Australian Senate representing Tasmania. He was previously a Tasmanian Greens member of the Tasmanian House of Assembly elected at the 2002 election ...

criticised the new immigration policy as a stealth effort by Immigration Minister Dutton to favour "English-speaking, white and wealthy" migrants. In addition, the new visa scheme was criticised by the "Ozkiwi lobby" since two thirds of New Zealanders living in Australia earned less than the qualifying rate. The Turnbull Government subsequently overturned the Skilled Independent visa in 2017.

In February 2018, an Australian Parliamentary Joint Committee recommend that Australian migration laws be amended to facilitate the removal of non-citizens under the age of 18 years. Despite concerns raised by New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern

Jacinda Kate Laurell Ardern ( ; born 26 July 1980) is a New Zealand politician who has been serving as the 40th prime minister of New Zealand and leader of the Labour Party since 2017. A member of the Labour Party, she has been the member of ...

and Foreign Minister Winston Peters

Winston Raymond Peters (born 11 April 1945) is a New Zealand politician serving as the leader of New Zealand First since its foundation in 1993. Peters served as the 13th deputy prime minister of New Zealand from 1996 to 1998 and 2017 to 2020, ...

, the Turnbull Government refused to budge on its 501 deportation policy. By May 2018, the Australian Government had accelerated its 501 deportation policy by deporting individuals on the basis of Dutton's ministerial discretion and repatriating adolescent offenders. In addition, Section 116 of the Migration Act 1958 also gave the Australian Immigration Minister the power to cancel the visas of lesser offenders without considering their ties to Australia. Between 2017 and 2019, there was a 400% increase in visa cancellations under Section 116 for offences that did not meet the Section 501 criteria.

In mid-July 2018, the effect of Australia's controversial new "character" test was the subject of a controversial ABC documentary by Peter FitzSimons

Peter John Allen FitzSimons (born 29 June 1961) is an Australian author, journalist, and radio and television presenter. He is a former national representative rugby union player and has been the chair of the Australian Republic Movement sin ...

entitled "Don't Call Australia Home." While the New Zealand Justice Minister

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

Andrew Little criticised the high deportation rate as a breach of human rights, the Australian Immigration Minister Dutton defended Australia's right to deport "undesirable" non-citizens. The ABC report was criticised by several Coalition Ministers including the now-Minister for Home Affairs

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergenc ...

Dutton and Assistant Minister of Home Affairs Alex Hawke

Alexander George Hawke (born 9 July 1977) is an Australian politician who served as Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs from 2020 to 2022 in the Morrison Government. Hawke has served as Member of ...

for ignoring the crimes and victims of the deportees. Hawke also criticised Little for not warning New Zealand nationals to obey Australian law. In response, Little criticized Australia's deportation laws for lacking "humanitarian ideals." In response, Dutton vowed to continue deporting non-citizen criminals and criticized New Zealand for not doing enough to assist Australian naval patrols intercepting the "people smugglers."

The documentary's release coincided with the release of a 17-year-old New Zealand youth from an Australian detention centre, who had successfully appealed against his deportation. The New Zealand Government expressed concern about the deportation of the teenager since minors under the age of 18 years were not covered by the adult deportees' monitoring regime. In response, Oranga Tamariki

Oranga Tamariki, also known as the Ministry for Children and previously the Ministry for Vulnerable Children, is a government department in New Zealand responsible for the well-being of children, specifically children at risk of harm, youth offen ...

(the Ministry of Children) began developing an "inter-departmental plan" to handle the repatriation of adolescent offenders.

In 25 October 2018, the Australian Immigration Minister David Coleman

David Robert Coleman OBE (26 April 1926 – 21 December 2013) was a British sports commentator and television presenter who worked for the BBC for 46 years. He covered eleven Summer Olympic Games from 1960 to 2000 and six FIFA World Cups from ...

introduced the ''Migration Amendment (Strengthening the Character Test) Bill 2018'' in response to reports that some judges had reduced criminal sentences to avoid triggering the Section 501 threshold for mandatory visa cancellations. The proposed Bill did not explicitly differentiate between adult and under-18 year old offenders. Despite opposition from New Zealand High Commissioner Annette King

Dame Annette Faye King (née Robinson, born 13 September 1947) is a former New Zealand politician. She served as Deputy Leader of the New Zealand Labour Party and Deputy Leader of the Opposition from 2008 to 2011, and from 2014 until 1 March 20 ...

, the Law Council of Australia, Australian Human Rights Commission

The Australian Human Rights Commission is the national human rights institution of Australia, established in 1986 as the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) and renamed in 2008. It is a statutory body funded by, but opera ...

, and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is a United Nations agency mandated to aid and protect refugees, forcibly displaced communities, and stateless people, and to assist in their voluntary repatriation, local integrati ...

(UNHCR), the Migration Amendment Bill 2018 progressed to its first reading on 25 October. However, the bill lapsed following the dissolution of the Australian Parliament prior to the 2019 Australian federal election

The 2019 Australian federal election was held on Saturday 18 May 2019 to elect members of the 46th Parliament of Australia. The election had been called following the dissolution of the 45th Parliament as elected at the 2016 double dissolut ...

in April 2019.

In late February 2020, Prime Minister Ardern criticised Australia's policy of deporting New Zealanders as "corrosive", saying that it was testing the relationship between the two countries. In response, the Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison

Scott John Morrison (; born 13 May 1968) is an Australian politician. He served as the 30th prime minister of Australia and as Leader of the Liberal Party of Australia from 2018 to 2022, and is currently the member of parliament (MP) for th ...

defended Australia's right to deport non-citizens. Dutton also defended the Australian Government's deportation policy, suggesting that Arden was playing to the New Zealand electoral cycle. In response, Ardern described Dutton's policy as regrettable and described her remarks as a defence of New Zealand's "principled position."

In mid-February 2021, Ardern criticised the Australian Government's decision to revoke dual New Zealand–Australian national Suhayra Aden's Australian citizenship. Aden was an ISIS

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kin ...

bride

A bride is a woman who is about to be married or who is newlywed.

When marrying, the bride's future spouse, (if male) is usually referred to as the '' bridegroom'' or just ''groom''. In Western culture, a bride may be attended by a maid, bri ...

who had migrated from New Zealand to Australia at the age of six, acquiring Australian citizenship. She subsequently traveled to Syria to live in the Islamic State. On 15 February 2021, Aden and two of her children were detained by Turkish authorities after illegally crossing the border. In response, Morrison defended the decision to revoke Aden's citizenship, citing legislation stripping dual nationals of their Australian citizenship if they were engaged in terrorist activities. Following a phone conversation, Ardern and Morrison agreed to work together in the "spirit of the relationship" to address what the former described as "quite a complex legal situation." In late May 2021, Morrison defended the revocation of Aden's citizenship but indicated that Canberra was open to allowing her children to settle in Australia. In mid–August 2021, Aden and her children were repatriated to New Zealand.

Non-citizens in Australia facing visa cancellation can appeal to the Australian Administrative Appeals Tribunal

The Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) is an Australian tribunal that conducts independent merits review of administrative decisions made under Commonwealth laws of the Australian Government. The AAT review decisions made by Australian Gover ...

(AAT), which hears visa cancellation appeals. However, the Minister of Home Affairs has the discretionary power to set aside AAT decisions. In December 2019, the New Zealand media company Stuff reported that 80% of appeals to the AAT were rejected or affirmed the Australian Government's visa cancellation orders. In January 2021, TVNZ's 1 News

''1 News'' (stylised as ''1News'') is the news division of New Zealand television network TVNZ. The service is broadcast live from TVNZ Centre in Auckland. The flagship news bulletin is the nightly 6 pm news hour, but ''1 News'' also has ...

reported that 25% of New Zealand nationals facing deportation under the 501 "character test" had successfully appealed against their deportations to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. These figures included 21 in the 2019-2020 financial year and 38 in the 2020-2021 year.

The repatriation of New Zealanders under the 501 character test policy has contributed to a surge in criminal activity