Antisemitism in France is the expression through words or actions of an

ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied pri ...

of hatred of Jews on French soil.

Jews were present in

Roman Gaul

Roman Gaul refers to GaulThe territory of Gaul roughly corresponds to modern-day France, Belgium and Luxembourg, and adjacient parts of the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany. under provincial rule in the Roman Empire from the 1st century ...

, but information is sketchy before the fourth century. As the

Roman Empire became Christianized, restrictions on Jews began and many emigrated, some to Gaul. In the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, France was a center of Jewish learning, but over time,

persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these ter ...

increased, including multiple expulsions and returns.

During the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

in the late 18th century, on the other hand, France was the first country in Europe to

emancipate its Jewish population.

Antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

still occurred in cycles, reaching a high level in the 1890s, as shown during the

Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

, and in the 1940s, under

German occupation

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 ...

and the

Vichy regime

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

.

During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, the Vichy government collaborated with

Nazi occupiers to deport a large number of both French Jews and foreign Jewish refugees to

concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

s.

Another 110,000 French Jews were living in the colony of French Algeria.

By the war's end, 25% of the Jewish population of France had perished in the

Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, though this was a lower proportion than in most other countries under Nazi occupation.

Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

br>

/ref>

Since 2000, a steep rise in assaults on people and property has given rise to a debate about the "new antisemitism", with many Jews no longer feeling safe in France. Since 2010 or so, more French Jews

The history of the Jews in France deals with Jews and Jewish communities in France since at least the Early Middle Ages. France was a centre of Jewish learning in the Middle Ages, but persecution increased over time, including multiple exp ...

have been moving to Israel in response to rising antisemitism in France.

Early period

Roman Gaul

The beginning of Jewish presence in Roman Gaul

Roman Gaul refers to GaulThe territory of Gaul roughly corresponds to modern-day France, Belgium and Luxembourg, and adjacient parts of the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany. under provincial rule in the Roman Empire from the 1st century ...

is uncertain. The southern part of France was under the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

from 122 BCE. Jews spread out after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, and more after the Bar Kokhba revolt

The Bar Kokhba revolt ( he, , links=yes, ''Mereḏ Bar Kōḵḇāʾ''), or the 'Jewish Expedition' as the Romans named it ( la, Expeditio Judaica), was a rebellion by the Jews of the Roman province of Judea, led by Simon bar Kokhba, ag ...

and the destruction of Jerusalem. Most went towards Rome, where they were offered protection by Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

, and later by Augustus; and then towards the edges of the Empire. Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

was an exile destination for banished Roman politicians, and as some Judeans

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous sout ...

were forced out of their land, likely some of them ended up there as well.

However, it is not until the fourth century that there is reliable documentation of the presence of Jews in Gaul. Not all were from Palestine, some were converted by Jews in the diaspora. As the Roman Empire became Christianized with the recognition of Christianity in 313 and the conversion of Constantine

During the reign of the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great (AD 306–337), Christianity began to transition to the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. Historians remain uncertain about Constantine's reasons for favoring Christianity, and ...

, restrictions on Jews began and increased the pressure on emigration, especially to Gaul which was less Christianized. Numbers were small, and were mostly along the coast, such as Narbonne and Marseille, but also in the river valleys and nearby communities, and extended as far as Clermont-Ferrand and Poitiers.

Jews in Gaul had certain rights, deriving from the ''Constitutio Antoniniana

The ''Constitutio Antoniniana'' ( Latin for: "Constitution r Edictof Antoninus") (also called the Edict of Caracalla or the Antonine Constitution) was an edict issued in AD 212, by the Roman Emperor Caracalla. It declared that all free men in t ...

'', decreed in 212 by the Roman Emperor Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname "Caracalla" () was Roman emperor from 198 to 217. He was a member of the Severan dynasty, the elder son of Emperor ...

to all inhabitants of the Empire, and included freedom of worship, the ability to hold public office, and serve in the army. Jews practiced every trade, and were no different than other Roman citizens, and dressed and spoke the same language as their fellow Romans. Even in the synagogue, where Hebrew was not the only language used. Relations were relatively good.

Information is sketchy, but there is evidence, some dating to the first century, of geographically widespread habitation in Metz, Poitiers, or Avignon. By the fifth century, there is evidence of settlements in Brittany, Orleans, Narbonne, and elsewhere.

Merovingian dynasty

After the

After the Fall of Rome

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its v ...

, the Merovingians

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gauli ...

ruled France from the fifth to the eighth century,Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος, Theodosios; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450) was Roman emperor for most of his life, proclaimed ''augustus'' as an infant in 402 and ruling as the eastern Empire's sole emperor after the death of his ...

and Valentinian III

Valentinian III ( la, Placidus Valentinianus; 2 July 41916 March 455) was Roman emperor in the West from 425 to 455. Made emperor in childhood, his reign over the Roman Empire was one of the longest, but was dominated by powerful generals vying ...

sent a decree to Amatius, prefect of Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

(9 July 425), that prohibited Jews and pagans from practicing law or holding public offices. This was to prevent Christians from being subject to them and possibly incited to change their faith.Clovis I

Clovis ( la, Chlodovechus; reconstructed Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first king of the Franks to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a single ki ...

converted to Catholicism in 496, along with the majority of the population which brought pressure on Jews to convert as well. The bishops in some localities offered Jews in their purview a choice between baptism and expulsion.Marseilles

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

, Arles

Arles (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Arle ; Classical la, Arelate) is a coastal city and commune in the South of France, a subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, in the former province ...

, Uzès

Uzès (; ) is a commune in the Gard department in the Occitanie region of Southern France. In 2017, it had a population of 8,454. Uzès lies about north-northeast of Nîmes, west of Avignon and south-east of Alès.

History

Originally ''Uc ...

, Narbonne

Narbonne (, also , ; oc, Narbona ; la, Narbo ; Late Latin:) is a commune in Southern France in the Occitanie region. It lies from Paris in the Aude department, of which it is a sub-prefecture. It is located about from the shores of the ...

, Clermont-Ferrand

Clermont-Ferrand (, ; ; oc, label= Auvergnat, Clarmont-Ferrand or Clharmou ; la, Augustonemetum) is a city and commune of France, in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, with a population of 146,734 (2018). Its metropolitan area (''aire d'attrac ...

, Orléans

Orléans (;["Orleans"](_blank)

(US) and [Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...]

, and Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectu ...

.conversion

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* "Conversion" (''Stargate Atlantis''), an episode of the television series

* "The Conversion" ...

to Christianity of the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is k ...

and Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools ...

made the condition of the Jews difficult: a succession of ecumenical council

An ecumenical council, also called general council, is a meeting of bishops and other church authorities to consider and rule on questions of Christian doctrine, administration, discipline, and other matters in which those entitled to vote ar ...

s diminished their rights until Dagobert I forced them to convert or leave France in 633.

During the councils of Elvira (305), (465), the three Councils of Orleans (533, 538, 541), and the Council of Clermont (535), the Church forbade Jews to have meals together with Christians, to have mixed marriages and proscribed the celebration of the ''shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; he, שַׁבָּת, Šabbāṯ, , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the week—i.e., Saturday. On this day, religious Jews remember the biblical stori ...

'', the aim being to limit the influence of Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in th ...

on the population.

Middle Ages

Persecutions under the Capets

There were widespread persecutions of Jews in France beginning in 1007.

There were widespread persecutions of Jews in France beginning in 1007.[ which also states that the King of France conspired with his vassals to destroy all the Jews on their lands who would not accept baptism, and many were put to death or killed themselves. Robert is credited with advocating forced conversions of local Jewry, as well as mob violence against Jews who refused. Among the dead was the learned Rabbi Senior. ]Robert the Pious

Robert II (c. 972 – 20 July 1031), called the Pious (french: link=no, le Pieux) or the Wise (french: link=no, le Sage), was King of the Franks from 996 to 1031, the second from the Capetian dynasty.

Crowned Junior King in 987, he assisted his ...

is well known for his lack of religious toleration and for the hatred that he bore toward heretics; it was Robert who reinstated the Roman imperial custom of burning heretics at the stake.Richard II, Duke of Normandy

Richard II (died 28 August 1026), called the Good (French: ''Le Bon''), was the duke of Normandy from 996 until 1026.

Life

Richard was the eldest surviving son and heir of Richard the Fearless and Gunnor. He succeeded his father as the ruler of ...

, Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

Jewry suffered from persecutions that were so terrible that many women, in order to escape the fury of the mob, jumped into the river and drowned. A notable of the town, Jacob ben Jekuthiel, a Talmudic scholar, sought to intercede with Pope John XVIII to stop the persecution in Lorraine (1007). Jacob undertook the journey to Rome, but was imprisoned with his wife and four sons by Duke Richard, and escaped death only by allegedly miraculous means. He left his eldest son, Judah, as a hostage with Richard while he with his wife and three remaining sons went to Rome. He bribed the pope with seven gold marks and two hundred pounds, who thereupon sent a special envoy to King Robert ordering him to stop the persecutions. If Adhémar of Chabannes, who wrote in 1030, is to be believed (he had a reputation as a fabricator), the anti-Jewish feelings arose in 1010 after Western Jews addressed a letter to their Eastern coreligionists warning them of a military movement against the

If Adhémar of Chabannes, who wrote in 1030, is to be believed (he had a reputation as a fabricator), the anti-Jewish feelings arose in 1010 after Western Jews addressed a letter to their Eastern coreligionists warning them of a military movement against the Saracens

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia ...

. According to Adémar, Christians urged by Pope Sergius IV

Pope Sergius IV (died 12 May 1012) was the bishop of Rome and nominal ruler of the Papal States from 31 July 1009 to his death. His temporal power was eclipsed by the patrician John Crescentius. Sergius IV may have called for the expulsion of M ...

were shocked by the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, hy, Սուրբ Հարության տաճար, la, Ecclesia Sancti Sepulchri, am, የቅዱስ መቃብር ቤተክርስቲያን, he, כנסיית הקבר, ar, كنيسة القيامة is a church i ...

in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

by the Muslims in 1009. After the destruction, European reaction to the rumor of the letter was of shock and dismay, Cluniac

The Cluniac Reforms (also called the Benedictine Reform) were a series of changes within medieval monasticism of the Western Church focused on restoring the traditional monastic life, encouraging art, and caring for the poor. The movement began ...

monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedic ...

Rodulfus Glaber blamed the Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

for the destruction. In that year Alduin, Bishop of Limoges (bishop 990-1012), offered the Jews of his diocese the choice between baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

and exile. For a month theologians held disputations with the Jews, but without much success, for only three or four of Jews abjured their faith; others killed themselves; and the rest either fled or were expelled from Limoges

Limoges (, , ; oc, Lemòtges, locally ) is a city and Communes of France, commune, and the prefecture of the Haute-Vienne Departments of France, department in west-central France. It was the administrative capital of the former Limousin region ...

.[ By 1030, Rodulfus Glaber knew more concerning this story. According to his 1030 explanation, Jews of ]Orléans

Orléans (;["Orleans"](_blank)

(US) and [Pope Alexander II

Pope Alexander II (1010/1015 – 21 April 1073), born Anselm of Baggio, was the head of the Roman Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1061 to his death in 1073. Born in Milan, Anselm was deeply involved in the Pataria reform ...]

wrote to Béranger, Viscount of Narbonne The viscount of Narbonne was the secular ruler of Narbonne in the Middle Ages. Narbonne had been the capital of the Visigoth province of Septimania, until the 8th century, after which it became the Carolingian Viscounty of Narbonne. Narbonne was ...

and to Guifred, bishop of the city, praising them for having prevented the massacre of the Jews in their district, and reminding them that God does not approve of the shedding of blood. In 1065 also, Alexander admonished Landulf VI of Benevento "that the conversion of Jews is not to be obtained by force." Also in the same year, Alexander called for a crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

against the Moors in Spain. These Crusaders killed without mercy all the Jews whom they met on their route.

Crusades

The Jews of France suffered during the

The Jews of France suffered during the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ...

(1096), when the crusaders are stated, for example, to have shut up the Jews of Rouen in a church and to have murdered them without distinction of age or sex, sparing only those who accepted baptism. According to a Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

document, the Jews throughout France were at that time in great fear and wrote to their brothers in the Rhine countries making known to them their terror and asking them to fast and pray. In the Rhineland, thousands of Jews were killed by the crusaders (see German Crusade, 1096

The Rhineland massacres, also known as the German Crusade of 1096 or ''Gzerot Tatnó'' ( he, גזרות תתנ"ו, "Edicts of 4856"), were a series of mass murders of Jews perpetrated by mobs of French and German Christians of the People's Cru ...

).

The Rhineland massacres

The Rhineland massacres, also known as the German Crusade of 1096 or ''Gzerot Tatnó'' ( he, גזרות תתנ"ו, "Edicts of 4856"), were a series of mass murders of Jews perpetrated by mobs of French and German Christians of the People's Cru ...

, also known as the German Crusade of 1096,the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europ ...

.

Prominent leaders of crusaders involved in the massacres included Peter the Hermit and especially Count Emicho

Emicho was a count in the Rhineland in the late 11th century. He is also commonly referred to as Emicho of Leiningen or Emich of Flonheim, and not to be confused with Bishop Emicho of Leiningen. In 1096, he was the leader of the Rhineland massacres ...

.Speyer

Speyer (, older spelling ''Speier'', French: ''Spire,'' historical English: ''Spires''; pfl, Schbaija) is a city in Rhineland-Palatinate in Germany with approximately 50,000 inhabitants. Located on the left bank of the river Rhine, Speyer lie ...

, Worms Worms may refer to:

*Worm, an invertebrate animal with a tube-like body and no limbs

Places

*Worms, Germany

Worms () is a city in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, situated on the Upper Rhine about south-southwest of Frankfurt am Main. It had ...

and Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

was noted as the "Hurban Shum" (Destruction of Shum).

In the

In the County of Toulouse

The County of Toulouse ( oc, Comtat de Tolosa) was a territory in southern France consisting of the city of Toulouse and its environs, ruled by the Count of Toulouse from the late 9th century until the late 13th century.

The territory is the ...

Jews were received on good terms until the Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade or the Cathar Crusade (; 1209–1229) was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted primarily by the French crow ...

. Toleration and favour shown to the Jews was one of the main complaints of the Roman Church against the Counts of Toulouse. Following the Crusaders' successful wars against Raymond VI and Raymond VII, the Counts were required to discriminate against Jews like other Christian rulers. In 1209, stripped to the waist and barefoot, Raymond VI was obliged to swear that he would no longer allow Jews to hold public office. In 1229 his son Raymond VII underwent a similar ceremony where he was obliged to prohibit the public employment of Jews, this time at Notre Dame in Paris. Explicit provisions on the subject were included in the Treaty of Meaux

The Treaty of Paris, also known as Treaty of Meaux, was signed on 12 April 1229 between Raymond VII of Toulouse and Louis IX of France in Meaux near Paris. Louis was still a minor, and it was his mother Blanche of Castile, as regent, who was inst ...

(1229). By the next generation a new, zealously Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, the ruler was arresting and imprisoning Jews for no crime, raiding their houses, seizing their cash, and removing their religious books. They were then released only if they paid a new "tax". A historian has argued that organized and official persecution of the Jews became a normal feature of life in southern France only after the Albigensian Crusade because it was only then that the Church became powerful enough to insist that measures of discrimination be applied.

Expulsions and returns

The practice of expelling the Jews accompanied by confiscation of their property, followed by temporary readmissions for ransom, was used during the Middle Ages to enrich the crown, including expulsions:

* from Paris by

The practice of expelling the Jews accompanied by confiscation of their property, followed by temporary readmissions for ransom, was used during the Middle Ages to enrich the crown, including expulsions:

* from Paris by Philip Augustus

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), byname Philip Augustus (french: Philippe Auguste), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks, but from 1190 onward, Philip became the first French m ...

in 1182

* from Vienne by order of Pope Innocent III in 1253

* from Brittany in 1240

* from Poitou in 1249

* from France by Louis IX

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the House of Capet, Direct Capetians. He was Coronation of the French monarch, c ...

in 1254

* by Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vas ...

of England from Gascony in 1288

* from Anjou and Maine in 1289

* from Nevers in 1294

* from Niort in 1296

* from Royal lands by Philip IV in 1306

* by Charles IV in 1322

* by Charles V in 1359

* by Charles VI in 1394.

In 1182, Philip Augustus

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), byname Philip Augustus (french: Philippe Auguste), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks, but from 1190 onward, Philip became the first French m ...

expelled the Jews from France, and recalled them again in 1198. There were various restrictions on interest on capital or debt in the 13th century under Louis VIII (1223–26) and Louis IX

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the House of Capet, Direct Capetians. He was Coronation of the French monarch, c ...

(1226–70). The Medieval Inquisition, which had been instituted in order to suppress Catharism

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. F ...

, finally occupied itself with the Jews of Southern France who converted to Christianity. In 1306 the treasury was nearly empty, and the king, as he was about to do the following year in the case of the Templars, condemned the Jews to banishment, and took forcible possession of their property, real and personal. Their houses, lands, and movable goods were sold at auction; and for the king were reserved any treasures found buried in the dwellings that had belonged to the Jews. In 1306, Louis X Louis X may refer to:

* Louis X of France, "the Quarreller" (1289–1316).

* Louis X, Duke of Bavaria (1495–1545)

* Louis I, Grand Duke of Hesse

Louis I, Grand Duke of Hesse (14 June 1753 in Prenzlau – 6 April 1830 in Darmstadt) was '' ...

(1314–16) recalled the Jews. In an edict dated 28 July 1315, he permitted them to return for a period of twelve years, authorizing them to establish themselves in the cities in which they had lived before their banishment.

On 17 September 1394, Charles VI suddenly published an ordinance in which he declared that thenceforth no Jew should dwell in his domains ("Ordonnances", vii. 675). According to the Religieux de St. Denis, the king signed this decree at the insistence of the queen ("Chron. de Charles VI." ii. 119). The decree was not immediately enforced, a respite being granted to the Jews in order that they might sell their property and pay their debts. Those indebted to them were enjoined to redeem their obligations within a set time; otherwise, their pledges held in pawns were to be sold by the Jews. The provost was to escort the Jews to the frontier of the kingdom. Subsequently, the king released the Christians from their debts.

Black Death

The

The Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

devastated Europe in the mid-14th century, annihilating more than half of the population, with Jews being made scapegoats. Rumors spread that they caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by violence, in particular in the Iberian peninsula and in the Germanic Empire. In Provence

Provence (, , , , ; oc, Provença or ''Prouvènço'' , ) is a geographical region and historical province of southeastern France, which extends from the left bank of the lower Rhône to the west to the Italian border to the east; it is bo ...

, forty Jews were burnt in Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

as early as April 1348. "Never mind that Jews were not immune from the ravages of the plague; they were tortured until they confessed to crimes that they could not possibly have committed.

"The large and significant Jewish communities in such cities as Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

, Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

, and Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

were wiped out at this time."(1406) In one such case, a man named Agimet was ... coerced to say that Rabbi Peyret of Chambéry

Chambéry (, , ; Arpitan: ''Chambèri'') is the prefecture of the Savoie department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of eastern France. The population of the commune of Chambéry was 58,917 as of 2019, while the population of the Chamb ...

(near Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

) had ordered him to poison the wells in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and fr ...

, and elsewhere. In the aftermath of Agimet's "confession", the Jews of Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label= Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label= Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the ...

were burned alive on 14 February 1349.[ Hertzberg, Arthur and Hirt-Manheimer, Aron. ''Jews: The Essence and Character of a People'', HarperSanFrancisco, 1998, p.84. ]

Although Pope Clement VI

Pope Clement VI ( la, Clemens VI; 1291 – 6 December 1352), born Pierre Roger, was head of the Catholic Church from 7 May 1342 to his death in December 1352. He was the fourth Avignon pope. Clement reigned during the first visitation of the Bl ...

tried to protect them by the 6 July 1348 papal bull and another 1348 bull, several months later, 900 Jews were burnt in Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label= Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label= Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the ...

, where the plague hadn't yet affected the city. Clement VI condemned the violence and said those who blamed the plague on the Jews (among whom were the flagellant

Flagellants are practitioners of a form of mortification of the flesh by whipping their skin with various instruments of penance. Many Christian confraternities of penitents have flagellants, who beat themselves, both in the privacy of their dw ...

s) had been "seduced by that liar, the Devil."Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

, where the Jewish quarter was sacked, and forty Jews were murdered in their homes. Shortly afterward, violence broke out in Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

and other Catalan cities.

In 1349, massacres and persecutions spread across Europe, including the Erfurt massacre, the Basel massacre, massacres in Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

, and Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

. 2,000 Jews were burnt alive on 14 February 1349 in the "Valentine's Day" Strasbourg massacre, where the plague had not yet affected the city. While the ashes smouldered, Christian residents of Strasbourg sifted through and collected the valuable possessions of Jews not burnt by the fires.

Many hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed in this period. Within the 510 Jewish communities destroyed in this period, some members killed themselves to avoid persecution.

In the spring of 1349, the Jewish community in Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

was annihilated. This was followed by the destruction of Jewish communities in Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

and Cologne. The 3,000-strong Jewish population of Mainz initially defended themselves and managed to hold off the Christian attackers. But the Christians managed to overwhelm the Jewish ghetto in the end and killed all of its Jews.

At Speyer, Jewish corpses were disposed of in wine casks and cast into the Rhine. By the close of 1349, the worst of the pogroms had ended in Rhineland. But around this time the massacres of Jews started rising near the Hanseatic League, Hansa townships of the Baltic Sea, Baltic Coast and in Eastern Europe. By 1351 there had been 350 incidents of anti-Jewish pogroms and 60 major and 150 minor Jewish communities had been exterminated.

Stereotypes and medieval Art

During the Middle Ages, much art was created by Christians that depicted Jews in a fictional or stereotypical manner; the great majority of narrative religious Medieval art depicted events from the Bible, where the majority of persons shown had been Jewish. But the extent to which this was emphasized in their depictions varied greatly. Some of this art was based on preconceived notions about how Jews dressed or looked, as well as the “sinning” acts that Christians believed that they committed.

During the Middle Ages, much art was created by Christians that depicted Jews in a fictional or stereotypical manner; the great majority of narrative religious Medieval art depicted events from the Bible, where the majority of persons shown had been Jewish. But the extent to which this was emphasized in their depictions varied greatly. Some of this art was based on preconceived notions about how Jews dressed or looked, as well as the “sinning” acts that Christians believed that they committed.

Ancien Regime

The Ancien Regime was the political and social system of the Kingdom of France from the Late Middle Ages (circa 15th century) until the French Revolution of 1789, during the period known as Early Modern France and epitomized by the 72-year reign (1643–1715) of King Louis XIV. In the run-up to the Revolution, France had a Jewish population of around 40,000 to 50,000, chiefly centered in Bordeaux, Metz and a few other cities. They had very limited rights and opportunities, apart from the moneylending business, but their status was legal.

Jewish residents of France lived on the periphery of the country: in the southwest, southeast, and northeast under conditions inherited from the Middle Ages, with only around 400 in Paris. Their main concern was simply to maintain their right of residency, which involved significant financial payments to various rulers, which was complex due to the division of authority between king and local seigneurs. In return, Jews were allowed to live in specific places, and occupy certain limited occupations, especially moneylending, and secondhand sales. Jews were a tolerated alien group that formed their own self-governing community, parallel to the general social order, but not quite part of it, and governed by their own ''halakha'' law. Although suffering social antipathy, they were able to practice their religion; in some areas only fairly recently. Of the various Jewish communities, the Marranos of the southwest, principally from Bordeaux, were the most commercially valued by the Crown, and were the most socially acculturated to general French society. Expelled from France in the 14th century, their privileges were once again recognized by Louis XV in 1723, primarily due to their economic utility as bankers and brokers.

The Ancien Regime was the political and social system of the Kingdom of France from the Late Middle Ages (circa 15th century) until the French Revolution of 1789, during the period known as Early Modern France and epitomized by the 72-year reign (1643–1715) of King Louis XIV. In the run-up to the Revolution, France had a Jewish population of around 40,000 to 50,000, chiefly centered in Bordeaux, Metz and a few other cities. They had very limited rights and opportunities, apart from the moneylending business, but their status was legal.

Jewish residents of France lived on the periphery of the country: in the southwest, southeast, and northeast under conditions inherited from the Middle Ages, with only around 400 in Paris. Their main concern was simply to maintain their right of residency, which involved significant financial payments to various rulers, which was complex due to the division of authority between king and local seigneurs. In return, Jews were allowed to live in specific places, and occupy certain limited occupations, especially moneylending, and secondhand sales. Jews were a tolerated alien group that formed their own self-governing community, parallel to the general social order, but not quite part of it, and governed by their own ''halakha'' law. Although suffering social antipathy, they were able to practice their religion; in some areas only fairly recently. Of the various Jewish communities, the Marranos of the southwest, principally from Bordeaux, were the most commercially valued by the Crown, and were the most socially acculturated to general French society. Expelled from France in the 14th century, their privileges were once again recognized by Louis XV in 1723, primarily due to their economic utility as bankers and brokers.

Revolutionary France

Run-up to Revolution

Before the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, the hostility of Voltaire made him place in his Philosophical Dictionary an exhortation addressed to the Jews: "you are calculating animals; try to be thinking animals". In the 1770s, the majority of Encyclopédistes, contributors to the ''Encyclopédie'' and other thought leaders (excepting rare philosemites like Irish philosopher John Toland in 1714, or Protestant pastor Jacques Basnage de Beauval in 1716), who were busy defending the civil rights of the black inhabitants of the French Antilles, Antilles, the Huron people, Hurons of North America, or other Amerindian, tribes, forgot to plead for the emancipation of their immediate neighbors, the Jews of France, and instead covered them with accusations and mockery.

Nevertheless, Denis Diderot, Diderot, in one of the longest articles of Diderot's Encyclopedia, The Encyclopedia, the article ' ("Jew"), does "justice to the importance of the destiny of the Jewish people, and the richness of their ideas".

Severe measures were taken against the Jews of Alsace (about 20,000 people) through the letters patent of 10 July 1784: limitation of the number of Jews and their marriages, economic restrictions, and other measures.

On the other hand, the edict of January 1784 by Louis XVI exempted the other Jews "from the duties of Leibzoll, and all other duties of this nature for their person only" which previously equated them with animals.

In 1787, the Royal Society of Arts and Sciences of Metz launched a contest: "Are there ways to make the Jews happier and more useful in France?"

French Revolution

Jews gained equal rights to French citizenship when the French National Assembly, National Assembly voted it in on 27 September 1791. An amendment was added later, removing certain privileges granting some autonomous rule to Jewish communities; these were removed, in order that Jews as individuals have the same rights as any other French citizen, neither more nor less.

Napoleon and First Empire

In the early 19th century, through his conquests in Europe, Napoleon Bonaparte spread the modernist ideas of revolutionary France: Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, equality of citizens and the rule of law. Napoleon's personal attitude towards the Jews has been interpreted in various ways by different historians, as at various times he made statements both in support of and in opposition to the Jewish people. Orthodox Rabbi Berel Wein claimed that Napoleon was interested primarily in seeing Jewish assimilation, the Jews assimilate, rather than prosper as a distinct community: "Napoleon's outward tolerance and fairness toward Jews was actually based upon his grand plan to have them disappear entirely by means of total assimilation, Jewish intermarriage, intermarriage, and conversion."

Third Republic

Media and organizations

Three antisemitic publications were formed in the 1882-1885 period, but did not last long: ''L'Anti-Juif'', ''L'Anti-Sémitique'', and ''Le Péril sociale''.

Edouard Drumont published his 1200-page antisemitic tract ''La France juive'' ("Jewish France") in 1886. A best-seller of its time, it was immensely popular and went through 140 printings in the first two years after initial publication. The book was so popular, it spawned its own literary genre, which saw the production in 1887 of ''Jewish Russia'' by Calixte de Wolski and ''Jewish Algeria'' by Georges Meynié, ''Jewish Austria'' by François Trocase in 1900, and ''Jewish England'' by Doedalus in 1913. Drumont's book was reprinted in 1938, 1986, and 2012; and in digital version in 2018.

Inspired by the success of the book, Drumont and founded the Antisemitic League of France () in 1889. It was active in the Dreyfus Affair. Jules Guérin was an active member. The League organized demonstrations and riots, a tactic later copied by other far-right organizations. Guerin edited the anti-Dreyfusard weekly newspaper ''L'Antijuif'' as the official organ of the Antisemitic League from 1898 to 1899. The ', directed at first by Ernest Jouin and later by Canon Schaefer, leader of the , went from 200 subscribers in 1912 to 2000 in 1932. The Catholic journalist Léon de Poncins, a follower of conspiracy theories and a contributor to many newspapers (including ''Le Figaro'', directed by François Coty, or ''L'Ami du Peuple,'' subtitled "Weekly magazine of action against occult forces" participated in it, as did the occultist Pierre Virion, who founded an association after the war with Maxime Weygand, General Weygand, the Vichy Minister of National Defense, before enforcing racist laws in North Africa.

''Le Grand Occident'', run by the anti-Dreyfusards , and , printed 6,000 copies in 1934. ''Le Réveil du peuple (revue), Le Réveil du peuple'', organ of the of Jean Boissel, to which and Urbain Gohier collaborated, distributed 3,000 copies in 1939. Having ceased publication in 1924, ''La Libre Parole'' started up again in 1928-1929, without commercial success, then in 1930 by Henry Coston (alias Georges Virebeau), who directed it until the war. Many famous antisemites wrote for the paper, including Jacques Ploncard, , , , , and . The monthly magazine of the same had a circulation of 2000 subscribers.

Other reviews were more fleeting, such as ''La France Réelle'', close to ''L'Action francaise''; the pro-fascist ''L'Insurgé'', or ''L'Ordre National'', close to ''La Cagoule'', an anti-communist and anti-Semitic terrorist group financed by Eugène Schueller, founder of L'Oréal. The latter published articles by Hubert Bourgin and .

The ', directed at first by Ernest Jouin and later by Canon Schaefer, leader of the , went from 200 subscribers in 1912 to 2000 in 1932. The Catholic journalist Léon de Poncins, a follower of conspiracy theories and a contributor to many newspapers (including ''Le Figaro'', directed by François Coty, or ''L'Ami du Peuple,'' subtitled "Weekly magazine of action against occult forces" participated in it, as did the occultist Pierre Virion, who founded an association after the war with Maxime Weygand, General Weygand, the Vichy Minister of National Defense, before enforcing racist laws in North Africa.

''Le Grand Occident'', run by the anti-Dreyfusards , and , printed 6,000 copies in 1934. ''Le Réveil du peuple (revue), Le Réveil du peuple'', organ of the of Jean Boissel, to which and Urbain Gohier collaborated, distributed 3,000 copies in 1939. Having ceased publication in 1924, ''La Libre Parole'' started up again in 1928-1929, without commercial success, then in 1930 by Henry Coston (alias Georges Virebeau), who directed it until the war. Many famous antisemites wrote for the paper, including Jacques Ploncard, , , , , and . The monthly magazine of the same had a circulation of 2000 subscribers.

Other reviews were more fleeting, such as ''La France Réelle'', close to ''L'Action francaise''; the pro-fascist ''L'Insurgé'', or ''L'Ordre National'', close to ''La Cagoule'', an anti-communist and anti-Semitic terrorist group financed by Eugène Schueller, founder of L'Oréal. The latter published articles by Hubert Bourgin and .

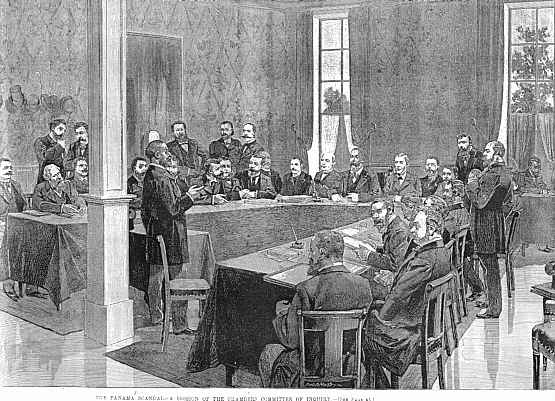

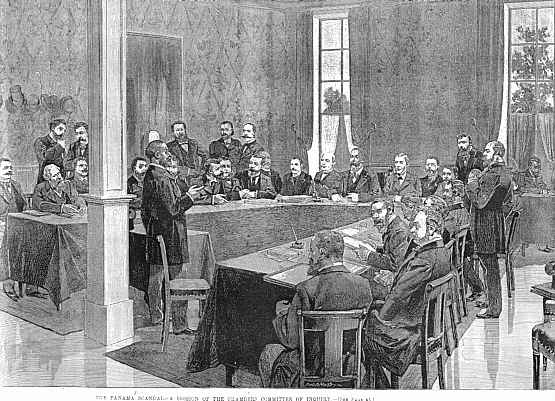

Panama Canal Scandal

The Panama Canal Scandal was a corruption affair that broke out in the French Third Republic in 1892, linked to a French company's failed attempt at building a canal through Panama. Close to half a billion francs were lost. Members of the French government took bribes to keep quiet about the History of the Panama Canal#The French project, Panama Canal Company's financial troubles in what is regarded as the largest monetary corruption scandal of the 19th century.

The Panama Canal Scandal was a corruption affair that broke out in the French Third Republic in 1892, linked to a French company's failed attempt at building a canal through Panama. Close to half a billion francs were lost. Members of the French government took bribes to keep quiet about the History of the Panama Canal#The French project, Panama Canal Company's financial troubles in what is regarded as the largest monetary corruption scandal of the 19th century. Hannah Arendt argues that the affair had an immense importance in the development of French antisemitism, due to the involvement of two Jews of German origin, Baron Jacques de Reinach and Cornelius Herz.

Hannah Arendt argues that the affair had an immense importance in the development of French antisemitism, due to the involvement of two Jews of German origin, Baron Jacques de Reinach and Cornelius Herz.

Dreyfus Affair

The

The Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

was a political scandal that divided the Third French Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolize modern injustice in the Francophone world, and it remains one of the most notable examples of a complex miscarriage of justice and antisemitism. The role played by the press and public opinion proved influential in the conflict.

The scandal began in December 1894 when Captain Alfred Dreyfus of History of the Jews in Alsace, Alsatian Jewish descent was convicted of treason. He was sentenced to life imprisonment for allegedly communicating French military secrets to the Germans, and was imprisoned in Devil's Island in French Guiana, where he spent nearly five years.

Antisemitism was a prominent factor throughout the affair. Existing prior to the Dreyfus affair, it had expressed itself during the Georges Ernest Boulanger, boulangisme affair and the Panama scandals, Panama Canal scandal but was limited to an intellectual elite. The Dreyfus Affair spread hatred of Jews through all strata of society, a movement that certainly began with the success of ''Jewish France'' by Édouard Drumont in 1886. It was then greatly amplified by various legal episodes and press campaigns for nearly fifteen years. Antisemitism was thenceforth official and was evident in numerous settings including the working classes. Candidates for the legislative elections took advantage of antisemitism as a watchword in parliamentary elections. This antisemitism was reinforced by the crisis of the separation of church and state in 1905, which probably led to its height in France. Antisemitic actions were permitted on the advent of the Vichy France, Vichy regime, which allowed free and unrestrained expression of racial hatred.

The scandal began in December 1894 when Captain Alfred Dreyfus of History of the Jews in Alsace, Alsatian Jewish descent was convicted of treason. He was sentenced to life imprisonment for allegedly communicating French military secrets to the Germans, and was imprisoned in Devil's Island in French Guiana, where he spent nearly five years.

Antisemitism was a prominent factor throughout the affair. Existing prior to the Dreyfus affair, it had expressed itself during the Georges Ernest Boulanger, boulangisme affair and the Panama scandals, Panama Canal scandal but was limited to an intellectual elite. The Dreyfus Affair spread hatred of Jews through all strata of society, a movement that certainly began with the success of ''Jewish France'' by Édouard Drumont in 1886. It was then greatly amplified by various legal episodes and press campaigns for nearly fifteen years. Antisemitism was thenceforth official and was evident in numerous settings including the working classes. Candidates for the legislative elections took advantage of antisemitism as a watchword in parliamentary elections. This antisemitism was reinforced by the crisis of the separation of church and state in 1905, which probably led to its height in France. Antisemitic actions were permitted on the advent of the Vichy France, Vichy regime, which allowed free and unrestrained expression of racial hatred.

Antisemitic riots

Antisemitic riots predated the Dreyfus Affair, and were almost a tradition in the East, where "the Alsatian people observed upon the outbreak of any revolution in France".[ as quoted in ] But the antisemitic riots that broke out in 1898 during the Dreyfus Affair were much more widespread. There were three waves of violence during January and February in 55 localities: the first ending the week of 23 January; the second wave in the week following; and the third wave from 23–28 February; Emile Zola's famous account ''J'Accuse'' appeared in ''L'Aurore'' on 13 January 1898, and most histories suggest that the riots were spontaneous reactions to its publication, and the subsequent Zola trial, with reports that "tumultuous demonstrations broke out nearly every day". Prefects or police in various towns noted demonstrations in their localities, and associated them with "the campaign undertaken in favor of ex-Captain Dreyfus", or with the "intervention by M. Zola", or the Zola trial itself, which "seems to have aroused the antisemitic demonstrations". In Paris, demonstrations around the Zola trial were frequent and sometimes violent. Roger Martin du Gard, Martin du Gard reported that "Individuals with Jewish features were grabbed, surrounded, and roughed up by delirious youths who danced round them, brandishing flaming torches, made from rolled-up copies of ''L'Aurore''.

Emile Zola's famous account ''J'Accuse'' appeared in ''L'Aurore'' on 13 January 1898, and most histories suggest that the riots were spontaneous reactions to its publication, and the subsequent Zola trial, with reports that "tumultuous demonstrations broke out nearly every day". Prefects or police in various towns noted demonstrations in their localities, and associated them with "the campaign undertaken in favor of ex-Captain Dreyfus", or with the "intervention by M. Zola", or the Zola trial itself, which "seems to have aroused the antisemitic demonstrations". In Paris, demonstrations around the Zola trial were frequent and sometimes violent. Roger Martin du Gard, Martin du Gard reported that "Individuals with Jewish features were grabbed, surrounded, and roughed up by delirious youths who danced round them, brandishing flaming torches, made from rolled-up copies of ''L'Aurore''.

Popular Front

Vichy regime

During World War II, the Vichy government collaboration with Nazi Germany, collaborated with Nazi Germany to arrest and deport a large number of both French Jews and foreign Jewish refugees to concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

s.[ By the war's end, 25% of the Jewish population of France had perished in the ]Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

.

Aryanization

Aryanization was the forced expulsion of Jews from business life in Nazi Germany, Axis-aligned states, and their occupied territories. It entailed the transfer of Jewish property into "Aryan race#The Aryan race in Nazi Germany, Aryan" hands. The process started in 1933 in Nazi Germany with transfers of Jewish property and ended with the Holocaust. The term is also used by historians to refer to the spoliation of French Jews, carried out jointly and concurrently by the German occupier and the Vichy regime. It followed the law of 22 July 1941 of the "French State", which itself followed the relentless Aryanization by the Germans in the fall of 1940 in the occupied zone. Long neglected, the spoliation of Jewish property has become a highly developed field of research since the 1990s.

The dispossession of Jews was from the outset included in the mission statement of the Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs, created on 29 March 1941 and directed first by Xavier Vallat and then by Louis Darquier de Pellepoix. From the summer of 1940, various German departments were also actively engaged in stealing Jewish property. Ambassador Otto Abetz took advantage of the to steal the art collections of absent Jewish owners. At the end of 1941, the Germans imposed an exorbitant fine of one billion francs on the French Jewish community, to be paid among other things upon the sale of Jewish property, and managed by the ''Caisse des dépôts et consignations''.

Historian Henry Rousso estimated the number of Aryanized companies at 10,000.

The term is also used by historians to refer to the spoliation of French Jews, carried out jointly and concurrently by the German occupier and the Vichy regime. It followed the law of 22 July 1941 of the "French State", which itself followed the relentless Aryanization by the Germans in the fall of 1940 in the occupied zone. Long neglected, the spoliation of Jewish property has become a highly developed field of research since the 1990s.

The dispossession of Jews was from the outset included in the mission statement of the Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs, created on 29 March 1941 and directed first by Xavier Vallat and then by Louis Darquier de Pellepoix. From the summer of 1940, various German departments were also actively engaged in stealing Jewish property. Ambassador Otto Abetz took advantage of the to steal the art collections of absent Jewish owners. At the end of 1941, the Germans imposed an exorbitant fine of one billion francs on the French Jewish community, to be paid among other things upon the sale of Jewish property, and managed by the ''Caisse des dépôts et consignations''.

Historian Henry Rousso estimated the number of Aryanized companies at 10,000.

Propaganda

''Le Juif et la France'' (The Jews and France) was an antisemitic propaganda exhibition that took place in Paris from 5 September 1941 to 15 January 1942

''Le Juif et la France'' (The Jews and France) was an antisemitic propaganda exhibition that took place in Paris from 5 September 1941 to 15 January 1942

Anti-Jewish legislation

Anti-Jewish laws were enacted by the Vichy government in 1940 and 1941 affecting metropolitan France and its overseas territories during World War II. These laws were, in fact, decrees by the head of state Marshal Philippe Pétain, since Parliament was no longer in office as of 11 July 1940. The motivation for the legislation was spontaneous and was not mandated by Germany.

In July 1940, Vichy set up a special commission charged with reviewing naturalizations granted since 1927 French nationality law, reform of the nationality law. Between June 1940 and August 1944, 15,000 persons, mostly Jews, were denaturalization, denaturalized. This bureaucratic decision was instrumental in their subsequent internment in the green ticket roundup.

Anti-Jewish laws were enacted by the Vichy government in 1940 and 1941 affecting metropolitan France and its overseas territories during World War II. These laws were, in fact, decrees by the head of state Marshal Philippe Pétain, since Parliament was no longer in office as of 11 July 1940. The motivation for the legislation was spontaneous and was not mandated by Germany.

In July 1940, Vichy set up a special commission charged with reviewing naturalizations granted since 1927 French nationality law, reform of the nationality law. Between June 1940 and August 1944, 15,000 persons, mostly Jews, were denaturalization, denaturalized. This bureaucratic decision was instrumental in their subsequent internment in the green ticket roundup.

Pétain personally made the 3 October 1940 law even more aggressively antisemitic than it initially was, as can be seen by annotations made on the draft in his own hand. The law "embraced the definition of a Jew established in the Nuremberg Laws", deprived the Jews of their civil rights, and fired them from many jobs. The law also forbade Jews from working in certain professions (teachers, journalists, lawyers, etc.) while the Law regarding foreign nationals of the Jewish race, law of 4 October 1940 provided authority for the incarceration of foreign Jews in internment camps in southern France such as Gurs internment camp, Gurs.

The statutes were aimed at depriving Jews of the right to hold public office, designating them as a Underclass, lower class, and depriving them of citizenship. Many Jews were subsequently rounded up at Drancy internment camp before being deported for extermination in Nazi concentration camps.

After the liberation of Paris when the Provisional Government of the French Republic, Provisional government was in control under Charles de Gaulle, these laws were declared null and void on 9 August 1944.

Pétain personally made the 3 October 1940 law even more aggressively antisemitic than it initially was, as can be seen by annotations made on the draft in his own hand. The law "embraced the definition of a Jew established in the Nuremberg Laws", deprived the Jews of their civil rights, and fired them from many jobs. The law also forbade Jews from working in certain professions (teachers, journalists, lawyers, etc.) while the Law regarding foreign nationals of the Jewish race, law of 4 October 1940 provided authority for the incarceration of foreign Jews in internment camps in southern France such as Gurs internment camp, Gurs.

The statutes were aimed at depriving Jews of the right to hold public office, designating them as a Underclass, lower class, and depriving them of citizenship. Many Jews were subsequently rounded up at Drancy internment camp before being deported for extermination in Nazi concentration camps.

After the liberation of Paris when the Provisional Government of the French Republic, Provisional government was in control under Charles de Gaulle, these laws were declared null and void on 9 August 1944.

The Holocaust

Between 1940 and 1944 Jews in occupied France, the zone libre, and in Vichy-controlled French North Africa as well as Romani people were persecuted, rounded up in raids, and deported to Nazi death camps. The persecution began in 1940, and culminated in deportations of Jews from France to Nazi concentration camps in Nazi Germany and Occupation of Poland (1939–1945), Nazi-occupied Poland. The deportations started in 1942 and lasted until July 1944. Of the 340,000 Jews living in metropolitan/continental France in 1940, more than 75,000 were deported to death camps, where about 72,500 were murdered. The government of Vichy France and the Law enforcement in France, French police organized and implemented the roundups of Jews.

Between 1940 and 1944 Jews in occupied France, the zone libre, and in Vichy-controlled French North Africa as well as Romani people were persecuted, rounded up in raids, and deported to Nazi death camps. The persecution began in 1940, and culminated in deportations of Jews from France to Nazi concentration camps in Nazi Germany and Occupation of Poland (1939–1945), Nazi-occupied Poland. The deportations started in 1942 and lasted until July 1944. Of the 340,000 Jews living in metropolitan/continental France in 1940, more than 75,000 were deported to death camps, where about 72,500 were murdered. The government of Vichy France and the Law enforcement in France, French police organized and implemented the roundups of Jews.

Roundups

French police carried out numerous roundups of Jews during World War II, including the Green ticket roundup in 1941,[, as quoted in ] the massive Vélodrome d'Hiver round-up in 1942 in which over 13,000 Jews were arrested,

= Green ticket roundup

=

The green ticket roundup took place on 14 May 1941 during the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France. The mass arrest started a day after French Police delivered a green card () to 6694 foreign Jews living in Paris, instructing them to report for a "status check".

Over half reported as instructed, most of them Polish and Czech. They were arrested and deported to one of two transit camps in France. Most of them were interned for a year before getting deported to Auschwitz and murdered.

The Green ticket roundup was the first mass round-up of Jewish people by the Vichy Regime.

The green ticket roundup took place on 14 May 1941 during the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France. The mass arrest started a day after French Police delivered a green card () to 6694 foreign Jews living in Paris, instructing them to report for a "status check".

Over half reported as instructed, most of them Polish and Czech. They were arrested and deported to one of two transit camps in France. Most of them were interned for a year before getting deported to Auschwitz and murdered.

The Green ticket roundup was the first mass round-up of Jewish people by the Vichy Regime.

= July 1942 Vel' d'Hiv Roundup

=

In July 1942 the French police organized the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup (''Rafle du Vel' d'Hiv'') under orders of René Bousquet and his second in Paris, Jean Leguay, with co-operation from authorities of the SNCF, the state railway company. The police arrested 13,152 Jews, including 4,051 children—which the ''Gestapo'' had not asked for—and 5,082 women, on 16 and 17 July and imprisoned them in the ''Vélodrome d'Hiver''. They were led to Drancy internment camp and subsequently crammed into box cars and shipped by rail to Auschwitz extermination camp. Most of the victims died en route due to a lack of food or water. Those who survived were murdered in the Gas chamber#Nazi Germany, gas chambers. This action alone represented more than a quarter of the 42,000 French Jews sent to concentration camps in 1942, of whom only 811 would survive the war. Although the Nazis had directed the action, French police authorities vigorously participated without resisting.

In July 1942 the French police organized the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup (''Rafle du Vel' d'Hiv'') under orders of René Bousquet and his second in Paris, Jean Leguay, with co-operation from authorities of the SNCF, the state railway company. The police arrested 13,152 Jews, including 4,051 children—which the ''Gestapo'' had not asked for—and 5,082 women, on 16 and 17 July and imprisoned them in the ''Vélodrome d'Hiver''. They were led to Drancy internment camp and subsequently crammed into box cars and shipped by rail to Auschwitz extermination camp. Most of the victims died en route due to a lack of food or water. Those who survived were murdered in the Gas chamber#Nazi Germany, gas chambers. This action alone represented more than a quarter of the 42,000 French Jews sent to concentration camps in 1942, of whom only 811 would survive the war. Although the Nazis had directed the action, French police authorities vigorously participated without resisting.

1941 Paris synagogue attacks

On the night of October 2–3, 1941, six synagogues in Paris were attacked and damaged by explosive devices placed by their doors.

Organized plunder

Nazi Germany plundered cultural property in Germany and from all the territories they occupied, targeting Jewish property in particular. Several organizations were created expressly for the purpose of looting books, paintings, and other cultural artefacts.

Post-World War II

Algeria

Background

There is evidence of Jewish settlements in Algeria since at least the Ancient Rome, Roman period (Mauretania Caesariensis). In the 7th century, Jewish settlements in North Africa were reinforced by Jewish immigrants that came to North Africa after fleeing from the persecutions of the Visigothic king Sisebut and his successors. They escaped to the Maghreb and settled in the Byzantine Empire. Later many Sephardic Jews were forced to take refuge in Algeria from the persecutions in Spain in 1391 and the Spanish Inquisition in 1492. They thronged to the ports of North Africa, and mingled with native Jewish people. In the 16th century there were large Jewish communities in places such as Oran, Béjaïa, Bejaïa and Algiers. By 1830, the Algerian Jewish population numbered 15,000, mostly congregated in the coastal area, with about 6,500 \in Algiers, where they made up a fifth of the population.

The French government granted Jews, who by then numbered some 33,000, French citizenship in 1870 under the Crémieux Decree

There is evidence of Jewish settlements in Algeria since at least the Ancient Rome, Roman period (Mauretania Caesariensis). In the 7th century, Jewish settlements in North Africa were reinforced by Jewish immigrants that came to North Africa after fleeing from the persecutions of the Visigothic king Sisebut and his successors. They escaped to the Maghreb and settled in the Byzantine Empire. Later many Sephardic Jews were forced to take refuge in Algeria from the persecutions in Spain in 1391 and the Spanish Inquisition in 1492. They thronged to the ports of North Africa, and mingled with native Jewish people. In the 16th century there were large Jewish communities in places such as Oran, Béjaïa, Bejaïa and Algiers. By 1830, the Algerian Jewish population numbered 15,000, mostly congregated in the coastal area, with about 6,500 \in Algiers, where they made up a fifth of the population.

The French government granted Jews, who by then numbered some 33,000, French citizenship in 1870 under the Crémieux Decree[Patrick Weil]

''How to Be French: Nationality in the Making since 1789,''

Duke University Press 2008 pp. 128, 253. The decision to extend citizenship to Algerian Jews was a result of pressures from prominent members of the liberal, intellectual French Jewish community, which considered the North African Jews to be "backward" and wanted to bring them into modernity.

Within a generation, despite initial resistance, most Algerian Jews came to speak French rather than Arabic or Ladino language, Ladino, and they embraced many aspects of French culture. In embracing "Frenchness," the Algerian Jews joined the colonizers, although they were still considered "other" to the French. Although some took on more typically European occupations, "the majority of Jews were poor artisans and shopkeepers catering to a Muslim clientele."[Friedman, Elizabeth. ''Colonialism & After''. South Hadley, Massachusetts: Bergen, 1988] Moreover, conflicts between Sephardic Jewish religious law and French law produced contention within the community. They resisted changes related to domestic issues, such as marriage.

French anti-Semitism set down strong roots among the expatriate French community in Algeria, where every municipal council was controlled by anti-Semites, and newspapers were rife with xenophobic attacks on the local Jewish communities.[Samuel Kalma]

''The Extreme Right in Interwar France: The Faisceau and the Croix de Feu,''

Ashgate Publishing 2008 pp.210ff. In Algiers when Émile Zola was brought to trial for his defense in an 1898 open letter, ''J'Accuse…!'', of Alfred Dreyfus, over 158 Jewish-owned shops were looted and burned and two Jews were killed, while the army stood by and refused to intervene.

A Vichy law of 7 October 1940 (pub. 8 October in the JO) abrogated the Cremieux decree and denaturalized the Jewish population of Algeria.

Struggle for independence

The Jewish community in Algeria had always been in a fragile position. After World War II, the Algerian Jewish community formed a number of organizations to support and safeguard religious institutions. The fate of the community was determined by the Algerian War, Algerian nationalist struggle for independence. Already in 1956, the Algerian National Liberation Front had appealed to "Algerians of Jewish origin" to choose Algerian nationality. Fears increased in 1958 when the FLN kidnapped and killed two officials of the Jewish Agency for Israel, Jewish Agency, and in 1960 with desecrations of the Great Synagogue of Algiers and the Jewish cemetery in Oran, and others were killed by the FLN.

Most Algerian Jews in 1961 still hoped for a solution of partition or dual nationality that would permit a resolution of the conflict, and groups such as the Comité Juif Algérien d'Etudes Sociales attempted to straddle the question of identity. Fears increased with the increasing terrorist activity by the OAS (''Organisation armée secrète'') and FLN, and emigration rose rapidly in mid-1962 with 70,000 leaving for France and 5,000 opting for Israel. The French government treated Jews and non-Jewish immigrants equally, and 32,000 Jews settled in the Paris area, with many others heading to Strasbourg which already had an established community. Estimates are that 80% of Algeria's Jewish community settled in France.