Antebellum Georgia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Georgia in the United States of America spans

Before European contact, Native American cultures are divided under archaeological criteria into four lengthy time periods of culture:

Before European contact, Native American cultures are divided under archaeological criteria into four lengthy time periods of culture:

At the time of

At the time of  An expedition of French Protestants founded the colonial settlement of

An expedition of French Protestants founded the colonial settlement of

pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era spans from the original settlement of North and South America in the Upper Paleolithic period through European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage of 1492. Usually, ...

time to the present-day U.S. state of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. The area was inhabited by Native American tribes for thousands of years. A modest Spanish presence was established in the late 16th century, mostly centered on Catholic missions. The Spanish had largely withdrawn from the territory by the early 18th century, although they had settlements in nearby Florida. They had little influence historically in what would become Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. (Most Spanish place names in Georgia date from the 19th century, not from the age of colonization.)

English settlers arrived in the 1730s, led by James Oglethorpe

James Edward Oglethorpe (22 December 1696 – 30 June 1785) was a British soldier, Member of Parliament, and philanthropist, as well as the founder of the colony of Georgia in what was then British America. As a social reformer, he hoped to r ...

. The name "Georgia", after George II of Great Britain

, house = Hanover

, religion = Protestant

, father = George I of Great Britain

, mother = Sophia Dorothea of Celle

, birth_date = 30 October / 9 November 1683

, birth_place = Herrenhausen Palace,Cannon. or Leine ...

, dates from the creation of this colony. Originally dedicated to the concept of common man, the colony forbade slavery. Failing to gain sufficient laborers from England, the colony overturned the ban in 1749 and began to import enslaved Africans. Slaves numbered 18,000 in the colony at the time of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. The citizens of Georgia agreed with the other American Colonies concerning trade rights and issues of taxation. On April 8, 1776, royal officials had been expelled and Georgia's Provincial Congress issued a constitutional document that served as an interim constitution until adoption of the state Constitution of 1777. The British occupied much of Georgia from 1780 until shortly before the official end of the American Revolution in 1783. Georgia was the fourth state to ratify the U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the nation ...

on January 2, 1788.

European Americans began to settle in Georgia, although it was territory of both the Creek and the Cherokee nations. They pressured state and the federal government to remove the Indians. After Indian Removal in the 1830s, under President Jackson, the pace of settlement by European Americans increased rapidly. The new cotton gin, invented at the end of the 18th century, enabled the profitable processing of short-staple cotton, which could now be grown in the inland and upcountry regions. This change stimulated the cotton boom in Georgia and much of the Deep South, resulting in cotton being a main economic driver, cultivated on slave labor. Based on enslaved labor, planters cleared and developed large cotton plantations. Many became immensely wealthy, but most of the yeomen whites did not own slaves and worked family subsistence farms.

On January 19, 1861, Georgia seceded from the Union and on February 8, 1861, joined other Southern states, all slave societies, to form the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

. Georgia contributed nearly one hundred twenty thousand soldiers to the Confederacy, with about five thousand Georgians (both black and white) joining the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

. The first major battle in the state was the Battle of Chickamauga

The Battle of Chickamauga, fought on September 19–20, 1863, between U.S. and Confederate forces in the American Civil War, marked the end of a Union offensive, the Chickamauga Campaign, in southeastern Tennessee and northwestern Georgia. I ...

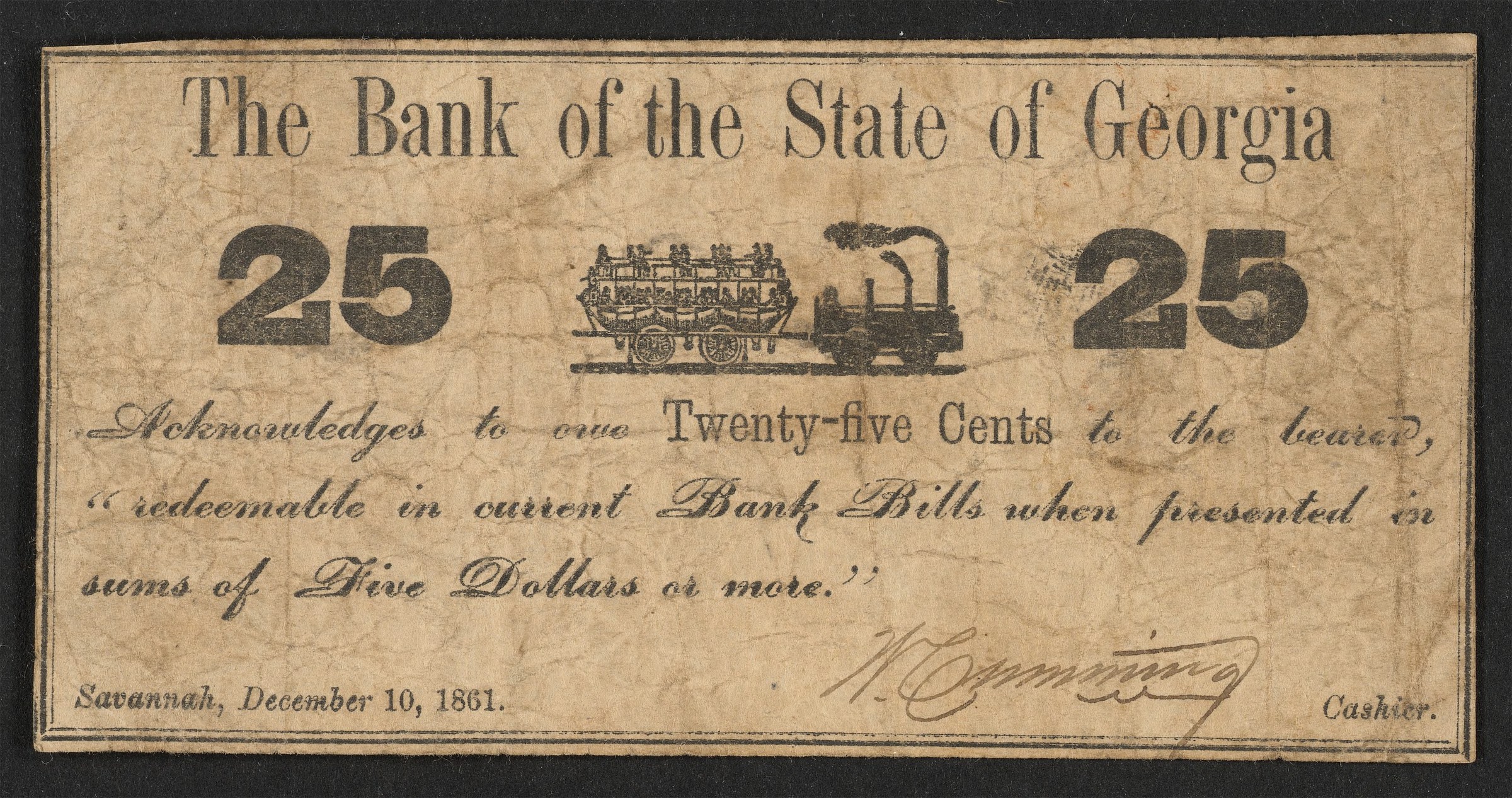

, a Confederate victory, and the last major Confederate victory in the west. In 1864, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

's armies invaded Georgia as part of the Atlanta Campaign. The burning of Atlanta

The Battle of Atlanta was a battle of the Atlanta Campaign fought during the American Civil War on July 22, 1864, just southeast of Atlanta, Georgia. Continuing their summer campaign to seize the important rail and supply hub of Atlanta, Uni ...

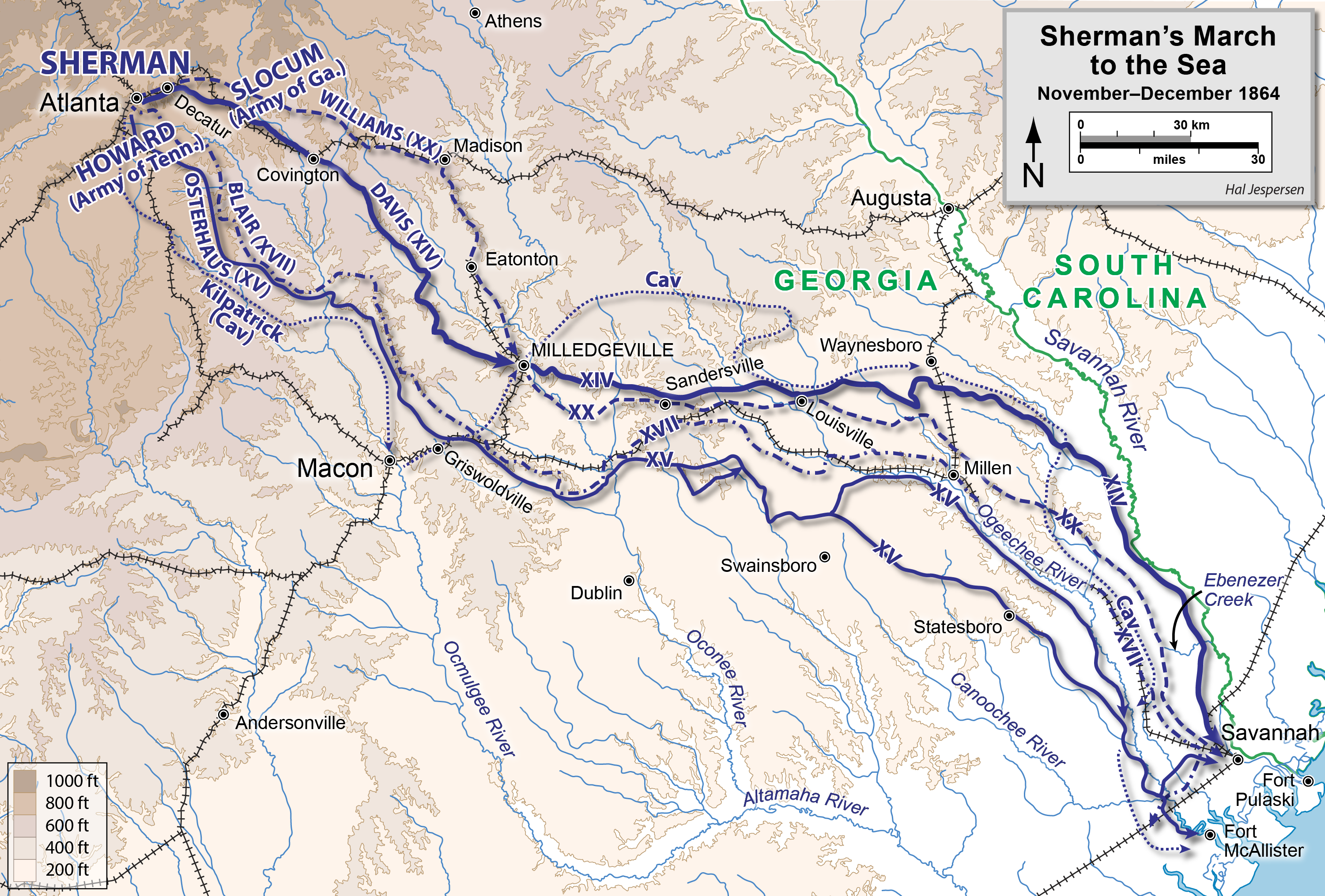

(which was a commercially vital railroad hub but not yet the state capital) was followed by Sherman's March to the Sea

Sherman's March to the Sea (also known as the Savannah campaign or simply Sherman's March) was a military campaign of the American Civil War conducted through Georgia from November 15 until December 21, 1864, by William Tecumseh Sherman, maj ...

, which laid waste to a wide swath of the state from Atlanta to Savannah in late 1864. These events became iconic in the state's memory and dealt a devastating economic blow to the entire Confederacy.

After the war, Georgians endured a period of economic hardship. Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

was a period of military occupation. With enfranchisement of freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

, who allied with the Republican Party, a biracial legislature was elected. It established public education and welfare institutions for the first time in the state, and initiated economic programs. Reconstruction ended in 1875 after white Democrats regained political control of the state, through violence and intimidation at elections. They passed new laws and constitutional amendments that disenfranchised

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

blacks and many poor whites near the turn of the century. In the Jim Crow era from the late 19th century to 1964, blacks were suppressed as second-class citizens, nearly excluded from politics. Thousands of blacks migrated North to escape these conditions and associated violence. The state was predominately rural, with an agricultural economy based on cotton into the 20th century. All residents of the state suffered in the Great Depression of the 1930s.

The many training bases and munitions plants established in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

stimulated the economy, and provided some new opportunities for blacks. During the broad-based activism of the Civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

in the 1950s and 1960s, Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

, Georgia was the base of African-American leader, minister Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

The state integrated public facilities. After 1950 the economy grew and became more diverse, with cotton receding in importance. Atlanta became a major regional city and transportation hub, expanding into neighboring communities through its fast-growing suburbs. Politically, Georgia was part of the Solid South

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the Southern United States for issues that were regarded as particularly important to the interests of Democrats in those states. The Southern bloc existed especial ...

until 1964, when it first voted for a Republican candidate for president. Democratic candidates continued to receive majority-white support in state and local elections until the 1990s, when the realignment of conservative whites shifted to the Republican Party. Atlanta was the host of the 1996 Summer Olympics

The 1996 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the XXVI Olympiad, also known as Atlanta 1996 and commonly referred to as the Centennial Olympic Games) were an international multi-sport event held from July 19 to August 4, 1996, in Atlanta, ...

, which marked the 100th anniversary of the modern Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games or Olympics (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques) are the leading international sporting events featuring summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a vari ...

. Georgia would grow rapidly both population wise and economically in the late 20th to early 21st century. In 2014, Georgia's population topped 10 million people, and was the fourth fastest growing U.S. state from 2013 to 2014.

Pre-Colonial era

Before European contact, Native American cultures are divided under archaeological criteria into four lengthy time periods of culture:

Before European contact, Native American cultures are divided under archaeological criteria into four lengthy time periods of culture: Paleo __NOTOC__

''Paleo'' may refer to:

Prehistoric Era, Age, or Period

* Paleolithic, a prehistoric Era, Age, or Period of human history

People

* David Strackany, aka "Paleo", an American folk singer-songwriter

Art, entertainment, and media

* ''P ...

, Archaic, Woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the ''plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (se ...

, and Mississippian. Their cultures were identified by characteristics of artifacts and other archeological evidence, including earthwork mound

A mound is a heaped pile of earth, gravel, sand, rocks, or debris. Most commonly, mounds are earthen formations such as hills and mountains, particularly if they appear artificial. A mound may be any rounded area of topographically higher ...

s that survive to the present and are visible aboveground.

Human occupation of Georgia can be dated to at least 13,250 years ago. This was one of the most dramatic periods of climate change in recent earth history, toward the end of the Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gre ...

, in the Late Pleistocene epoch. Sea levels were more than 200 feet lower than present levels. The Atlantic Ocean shoreline was 100 or more miles seaward of its current boundary. A 2003 research project undertaken by University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

researchers Ervan G, Garrison, Sherri L. Littman, and Megan Mitchell, looked at and reported on fossils and artifacts associated with Gray's Reef National Marine Sanctuary

Gray's Reef National Marine Sanctuary is one of the largest near shore live-bottom reefs in the southeastern United States. The sanctuary, designated in January 1981, is located off Sapelo Island, Georgia, and is one of 14 marine sanctuaries and m ...

, which is located more than beyond today's shoreline, and 60 to 70 feet (18 to 21 m) below the Atlantic Ocean. As recently as 8,000 years ago, Gray's Reef was dry ground, attached to the mainland. The researchers uncovered artifacts from a period of occupation by Clovis culture

The Clovis culture is a prehistoric Paleoamerican culture, named for distinct stone and bone tools found in close association with Pleistocene fauna, particularly two mammoths, at Blackwater Locality No. 1 near Clovis, New Mexico, in 1936 a ...

and Paleoindian hunters dating back more than 10,000 years.

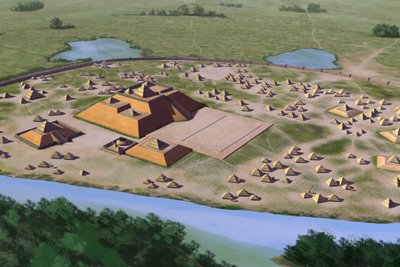

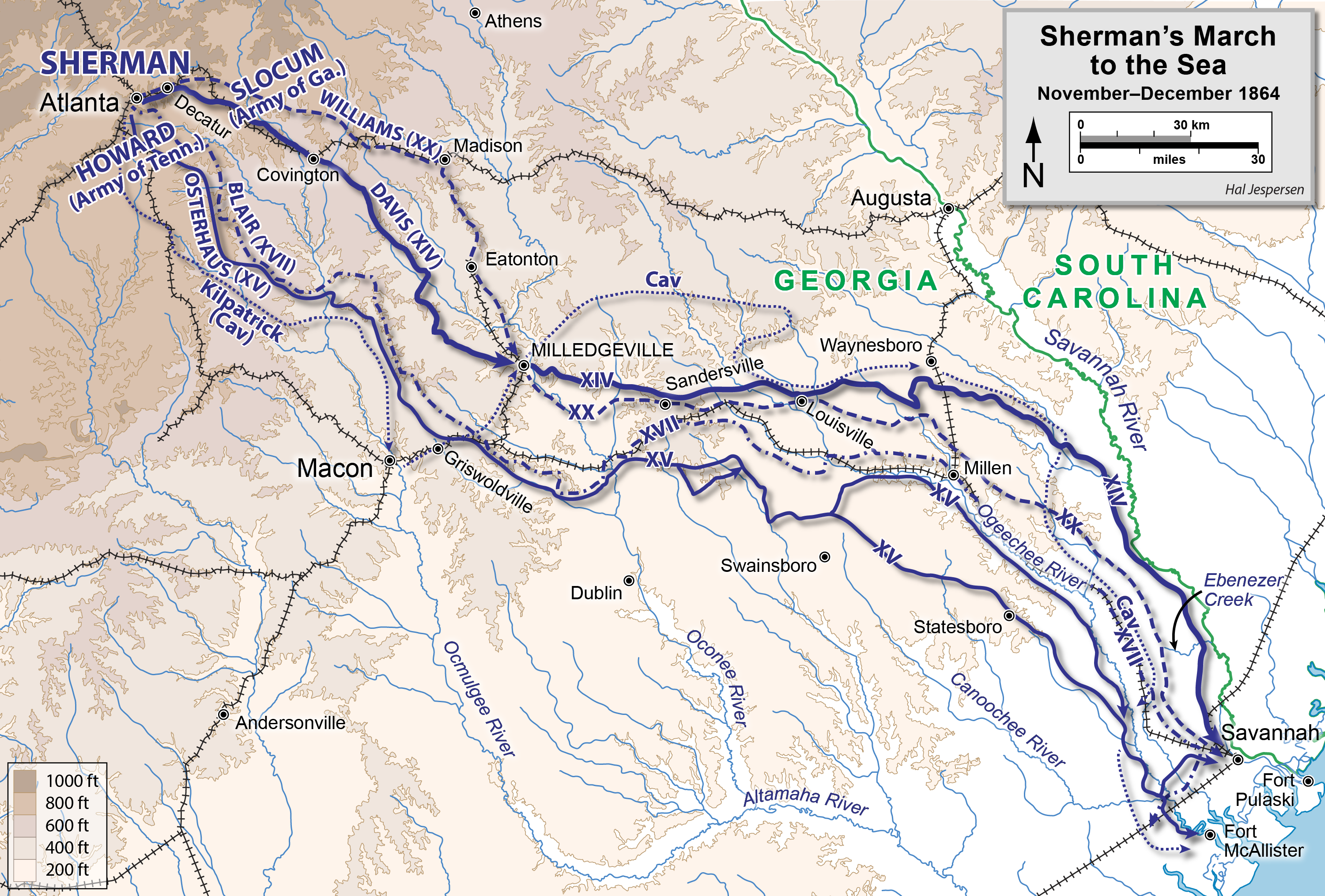

The South Appalachian Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building large, earth ...

, the last of many mound building

A number of pre-Columbian cultures are collectively termed "Mound Builders". The term does not refer to a specific people or archaeological culture, but refers to the characteristic mound earthworks erected for an extended period of more than 5 ...

Native American cultures, lasted from 800 to 1500 AD. This culture developed urban societies distinguished by their construction of truncated earthworks

Earthworks may refer to:

Construction

*Earthworks (archaeology), human-made constructions that modify the land contour

* Earthworks (engineering), civil engineering works created by moving or processing quantities of soil

*Earthworks (military), m ...

pyramids, or platform mound

Platform may refer to:

Technology

* Computing platform, a framework on which applications may be run

* Platform game, a genre of video games

* Car platform, a set of components shared by several vehicle models

* Weapons platform, a system or ...

s; as well as their hierarchical chiefdom

A chiefdom is a form of hierarchical political organization in non-industrial societies usually based on kinship, and in which formal leadership is monopolized by the legitimate senior members of select families or 'houses'. These elites form a ...

s; intensive village-based maize horticulture, which enabled the development of more dense populations; and creation of ornate copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

, shell and mica paraphernalia

Paraphernalia most commonly refers to a group of apparatus, equipment, or furnishing used for a particular activity. For example, an avid sports fan may cover their walls with football and/or basketball paraphernalia.

Historical legal term

In l ...

adorned with a series of motifs known as the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (formerly the Southern Cult), aka S.E.C.C., is the name given to the regional stylistic similarity of artifacts, iconography, ceremonies, and mythology of the Mississippian culture. It coincided with their ado ...

(SECC). The largest sites surviving in present-day Georgia are Kolomoki in Early County, Etowah in Bartow County

Bartow County is located in the northwestern part of the U.S. state of Georgia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 108,901, up from 100,157 in 2010. The county seat is Cartersville.

Traditionally considered part of northwest Georgia, B ...

, Nacoochee Mound

The Nacoochee Mound (Smithsonian trinomial 9WH3) is an archaeological site on the banks of the Chattahoochee River in White County, in the northeast part of the U.S. state of Georgia. Georgia State Route 17 and Georgia State Route 75 have a ju ...

in White County, and Ocmulgee National Monument

Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park (formerly Ocmulgee National Monument) in Macon, Georgia, United States preserves traces of over ten millennia of culture from the Native Americans in the Southeastern Woodlands. Its chief remains are majo ...

in Macon.

European exploration

At the time of

At the time of European colonization of the Americas

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale European colonization of the Americas took place between about 1492 and 1800. Although the Norse had explored and colonized areas of the North Atlantic, colonizing Greenland and creating a short t ...

, the historic Iroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoian ...

-speaking Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

and Muskogean

Muskogean (also Muskhogean, Muskogee) is a Native American language family spoken in different areas of the Southeastern United States. Though the debate concerning their interrelationships is ongoing, the Muskogean languages are generally div ...

-speaking Yamasee

The Yamasees (also spelled Yamassees or Yemassees) were a multiethnic confederation of Native Americans who lived in the coastal region of present-day northern coastal Georgia near the Savannah River and later in northeastern Florida. The Yamas ...

& Hitchiti

The Hitchiti ( ) were a historic indigenous tribe in the Southeast United States. They formerly resided chiefly in a town of the same name on the east bank of the Chattahoochee River, four miles below Chiaha, in western present-day Georgia. The n ...

peoples lived throughout Georgia.

The coastal regions were occupied by groups of small, Muskogean-speaking tribes with a loosely shared heritage, consisting mostly of the Guale

Guale was a historic Native American chiefdom of Mississippian culture peoples located along the coast of present-day Georgia and the Sea Islands. Spanish Florida established its Roman Catholic missionary system in the chiefdom in the late 16t ...

-associated groups to the east and the Timucua

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The v ...

group to the south. This group of 35 tribes had lands that extended into central Florida; they were bordered by the Hitchiti and their territory to the west.

The Muskogean peoples were related by language to the three large Muskogean nations that occupied territories between the Mississippi River and the Cherokee: the Choctaw, Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classif ...

and Coushatta

The Coushatta ( cku, Koasati, Kowassaati or Kowassa:ti) are a Muskogean-speaking Native American people now living primarily in the U.S. states of Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Texas.

When first encountered by Europeans, they lived in the terri ...

. There were also a few other small Muskogean tribes along the Florida-Alabama Gulf Coast region. Archaeology shows that these historic peoples were in this region, at the very least, from the 12th century to colonial times. The name for Appalachia came from the Timucuan language, and a specific group from northern Florida called the Apalachee

The Apalachee were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, specifically an Indigenous people of Florida, who lived in the Florida Panhandle until the early 18th century. They lived between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River,B ...

.

Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León may have sailed along the coast during his exploration of Florida. In 1526, Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón

Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón (c. 1480 – 18 October 1526) was a Spanish magistrate and explorer who in 1526 established the short-lived San Miguel de Gualdape colony, one of the first European attempts at a settlement in what is now the United State ...

attempted to establish a colony on an island, possibly near St. Catherines Island. At San Miguel de Gualdape

San Miguel de Gualdape (sometimes San Miguel de Guadalupe) is a former Spanish colony in present-day Georgetown County, South Carolina, founded in 1526 by Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón.In early 1521, Ponce de León had made a poorly documented, disas ...

, the first Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different eleme ...

took place in the boundaries of what are today the United States.

From 1539 to 1542 Hernando de Soto, a Spanish '' conquistador'', led the first European expedition deep into the territory of the modern-day southern United States searching for gold, and a passage to China. A vast undertaking, de Soto's North American expedition ranged across parts of the modern states of Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas. His expedition traversed much of the state of Georgia from south to north, and it recorded encountering many native groups along the way. These have largely been identified as part of the Mississippian culture and its chiefdoms.

An expedition of French Protestants founded the colonial settlement of

An expedition of French Protestants founded the colonial settlement of Charlesfort

The Charlesfort-Santa Elena Site is an important early colonial archaeological site on Parris Island, South Carolina. It contains the archaeological remains of a French settlement called Charlesfort, settled in 1562 and abandoned the following y ...

in 1562 on Parris Island

Parris is both a given name and surname. Notable people with the name include:

Given name

* Parris Afton Bonds, American novelist

* Parris Campbell (born 1997), American football player

* Parris Duffus (born 1970), retired American ice hockey go ...

off the coast of South Carolina. Jean Ribault

Jean Ribault (also spelled ''Ribaut'') (1520 – October 12, 1565) was a French naval officer, navigator, and a colonizer of what would become the southeastern United States. He was a major figure in the French attempts to colonize Florida. A H ...

and his party of French Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

settled an area in the Port Royal Sound Port Royal Sound is a coastal sound, or inlet of the Atlantic Ocean, located in the Sea Islands region, in Beaufort County in the U.S. state of South Carolina. It is the estuary of several rivers, the largest of which is the Broad River.

Geograp ...

area of present-day South Carolina. Within a year the colony failed. Most of the colonists followed René Goulaine de Laudonnière

Rene Goulaine de Laudonnière (c. 1529–1574) was a French Huguenot explorer and the founder of the French colony of Fort Caroline in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, a Huguenot, sent Jean Ribault and Laudonnière ...

south and founded a new outpost called Fort Caroline

Fort Caroline was an attempted French colonial settlement in Florida, located on the banks of the St. Johns River in present-day Duval County. It was established under the leadership of René Goulaine de Laudonnière on 22 June, 1564, follow ...

in present-day Florida.

Over the next few decades, a number of Spanish explorers from Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

visited the inland region of present-day Georgia. The Mississippian culture way of life, described by de Soto in 1540, had completely disappeared by the mid-1600s. The people may have suffered from new infectious diseases carried by the Europeans. Remaining peoples are believed to have coalesced as the documented historic tribes. .

English fur traders from the Province of Carolina first encountered the Creek people

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsOcmulgee. There they traded iron tools, guns, cloth, and rum for deerskins and Indian slaves, captured by warring tribes in regular raids.

The conflict between Spain and

The conflict between Spain and  English settlement began in the early 1730s after

English settlement began in the early 1730s after

The original eight counties of Georgia were

The original eight counties of Georgia were

In 1787, the

In 1787, the

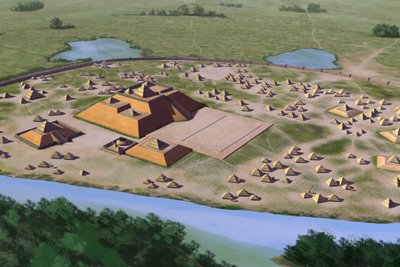

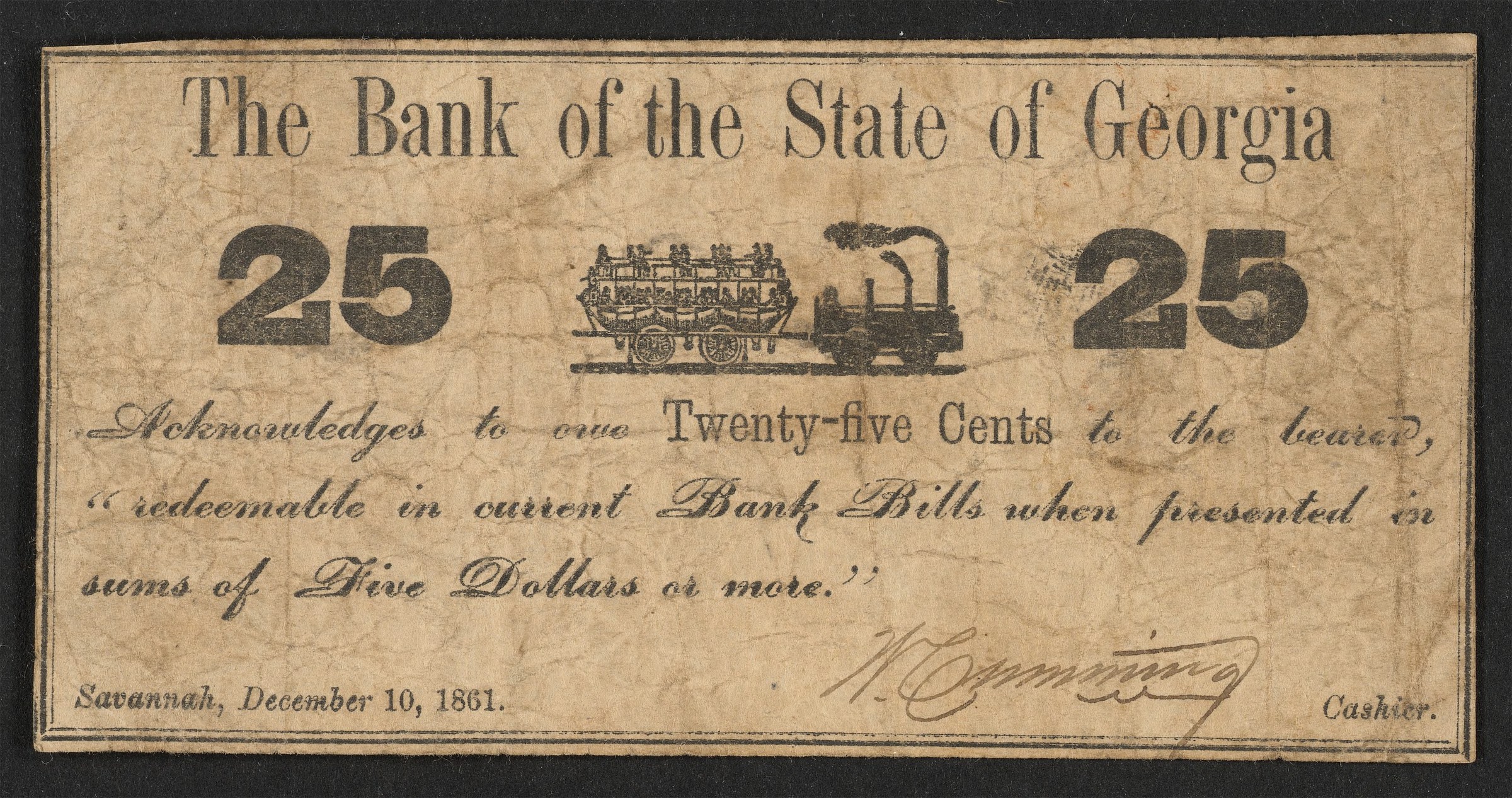

On January 19, 1861, Georgia seceded from the Union, keeping the name "State of Georgia" and joining the newly formed Confederacy in February. White solidarity was strong in 1861–63, as the planters in the Black Belt formed a common cause with upcountry yeomen farmers in defense of the Confederacy against the Union. Around 120,000 Georgians served in the Confederate Army. However disillusionment set in by 1863, with class tensions becoming more serious, including food riots, desertions, and growing Unionist activity in the northern mountain region. Approximately 5,000 Georgians (both black and white troops) served in the

On January 19, 1861, Georgia seceded from the Union, keeping the name "State of Georgia" and joining the newly formed Confederacy in February. White solidarity was strong in 1861–63, as the planters in the Black Belt formed a common cause with upcountry yeomen farmers in defense of the Confederacy against the Union. Around 120,000 Georgians served in the Confederate Army. However disillusionment set in by 1863, with class tensions becoming more serious, including food riots, desertions, and growing Unionist activity in the northern mountain region. Approximately 5,000 Georgians (both black and white troops) served in the

The first major battle in Georgia was a Confederate victory at the

The first major battle in Georgia was a Confederate victory at the

/ref> After the war, the state subsidized construction of numerous new railroad lines to improve infrastructure and connections to markets. Use of commercial fertilizers increased cotton production in Georgia's upcountry, but the coastal rice plantations never recovered from the war. In January 1865,

Under the Reconstruction government, the state capital was moved from Milledgeville to the inland rail terminus of

Under the Reconstruction government, the state capital was moved from Milledgeville to the inland rail terminus of

History and Archeology (1877–1900), New Georgia Encyclopedia, 2007–2017; accessed March 17, 2018 This period also corresponded to Georgia's

, accessed March 15, 2008 The state instituted a

/ref> Franklin Delano Roosevelt visited Georgia on numerous occasions. He established his '

African Americans who served in the segregated military during World War II returned to a still segregated nation and a South which still enforced

African Americans who served in the segregated military during World War II returned to a still segregated nation and a South which still enforced  The SCLC led a desegregation campaign in

The SCLC led a desegregation campaign in

In 1980, construction was completed on an expansion of William B. Hartsfield International Airport. The busiest in the world, it was designed to accommodate up to 55 million passengers a year. The airport became a major engine for economic growth. With the advantages of cheap real estate, low taxes, right-to-work laws and a regulatory environment limiting government interference, the Atlanta metropolitan area became a national center of finance, insurance, and real estate companies, as well as the convention and trade show business. As a testament to the city's growing international profile, in 1990 the International Olympic Committee selected

In 1980, construction was completed on an expansion of William B. Hartsfield International Airport. The busiest in the world, it was designed to accommodate up to 55 million passengers a year. The airport became a major engine for economic growth. With the advantages of cheap real estate, low taxes, right-to-work laws and a regulatory environment limiting government interference, the Atlanta metropolitan area became a national center of finance, insurance, and real estate companies, as well as the convention and trade show business. As a testament to the city's growing international profile, in 1990 the International Olympic Committee selected

''New Georgia Encyclopedia'' (2005)

Scholarly resource covering all topics. * Bartley, Numan V. ''The Creation of Modern Georgia'' (1990). Scholarly history 1865–1990. * Coleman, Kenneth. ed. ''A History of Georgia'' (1991). Survey by scholars. * Coulter, E. Merton. ''A Short History of Georgia'' (1933) * Grant, Donald L. ''The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia'' 1993 *London, Bonta Bullard. (1999) ''Georgia: The History of an American State'' Montgomery, Alabama: Clairmont Press . A middle school textbook.

in JSTOR

*Flynn Jr., Charles L. ''White Land, Black Labor: Caste and Class in Late Nineteenth-Century Georgia'' (LSU Press 1983) *Freehling, William W., and Craig M. Simpson; ''Secession Debated: Georgia's Showdown in 1860'' Oxford University Press, 1992 * Greene, Evarts Boutell. ''Provincial America, 1690–1740'' (1905

ch 15 online pp 249–269 covers 1732–1754.

* Haggard, Dixie Ray. “The First Invasion of Georgia and the Myth of Westo Power, 1656–1684,” ''Journal of Military History'' 86:3 (July 2022): 533–5

*Hahn Steven. ''The Roots of Southern Populism: Yeoman Farmers and the Transformation of the Georgia Upcountry, 1850–1890.'' Oxford University Press, 1983. * *Miles, Jim ''To the Sea: A History and Tour Guide of the War in the West: Sherman's March Across Georgia, 1864'' Cumberland House Publishing, (2002) *Mohr, Clarence L. ''On the Threshold of Freedom: Masters and Slaves in Civil War Georgia'' (1986) *Parks, Joseph H. ''Joseph E. Brown of Georgia.'' LSU Press, 1977. *Parks, Joseph H. "State Rights in a Crisis: Governor Joseph E. Brown versus President Jefferson Davis." ''Journal of Southern History'' 32 (1966): 3–24

in JSTOR

*Pyron; Darden Asbury. ed. ''Recasting: Gone with the Wind in American Culture'' University Press of Florida. (1983

online

* Range, Willard. ''A century of Georgia Agriculture, 1850–1950'' (1954) *Reidy; Joseph P. ''From Slavery to Agrarian Capitalism in the Cotton Plantation South: Central Georgia, 1800–1880'' University of North Carolina Press

(1992)

* Reidy, Joseph P. "Karen A. Bradley: Voice of Black Labor in the Georgia Lowcountry," in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. ''Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era'' (1982) pp 281 – 309. * Russell, James M. and Thornbery, Jerry. "William Finch of Atlanta: The Black Politician as Civic Leader," in Howard N. Rabinowitz, ed. ''Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era'' (1982) pp 309–34. * Saye, Albert B. ''New Viewpoints in Georgia History'' 1943, on Revolution * Schott, Thomas E. ''Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia: A Biography''. LSU Press, 1988. * Thompson, C. Mildred. ''Reconstruction In Georgia: Economic, Social, Political 1865-1872'' (19i5; 2010 reprint

excerpt and text searchfull text online free

* Thompson, C. Mildred. ''Reconstruction In Georgia: Economic, Social, Political 1865–1872'' (19i5; 2010 reprint) excerpt and text search

full text online free

* Thompson, William Y. ''Robert Toombs of Georgia.'' LSU Press, 1966. * Wallenstein; Peter. ''From Slave South to New South: Public Policy in Nineteenth-Century Georgia'' (University of North Carolina Press, 1987

online edition

* Wetherington, Mark V. ''Plain Folk's Fight: The Civil War and Reconstruction in Piney Woods Georgia'' (University of North Carolina Press, 2005) 383 pp

online review by Frank Byrne

* Woodward, C. Vann. ''Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel'' (1938)

online edition

* Cashin, Edward J., and Glenn T. Eskew, eds. ''Paternalism in a Southern City: Race, Religion, and Gender in Augusta, Georgia'' (University of Georgia Press, 2001). *Ferguson; Karen. ''Black Politics in New Deal Atlanta'' University of North Carolina Press, 2002 *Flamming; Douglas ''Creating the Modern South: Millhands and Managers in Dalton, Georgia, 1884–1984'' University of North Carolina Press, 199

Online edition

* Garrett, Franklin Miller. ''Atlanta and Environs: A Chronicle of Its People and Events'' (1969), 2 vol. * Goodson, Steve. ''Highbrows, Hillbillies, and Hellfire: Public Entertainment in Atlanta, 1880–1930'' University of Georgia Press, 2002. . * Rogers, William Warren. ''Transition to the Twentieth Century: Thomas County, Georgia, 1900–1920'' 2002. vol 4 of comprehensive history of one county. * Scott, Thomas Allan. ''Cobb County, Georgia, and the Origin of the Suburban South: A Twentieth Century History'' (2003). * Werner, Randolph D. "The New South Creed and the Limits of Radicalism: Augusta, Georgia, before the 1890s." ''Journal of Southern History'' 67.3 (2001): 573-60

online

* Whites, LeeAnn. ''Civil War as a Crisis in Gender: Augusta, Georgia, 1860–1890'' (University of Georgia Press, 2000)

Biographical Memorials of James Oglethorpe

by Thaddeus Mason Harris, 1841

A Brief Description and Statistical Sketch of Georgia

United States of America: developing its immense agricultural, mining and manufacturing advantages, with remarks on emigration. Accompanied with a map & description of lands for sale in Irwin County, By Richard Keily, 1849.

Essay on the Georgia Gold Mines

by William Phillips, 1833 (Excerpt from: American Journal of Science and Arts. New Haven, 1833. Vol. XXIV, No. i, First Series, April (Jan.-March), 1833, pp. 1–18.)

An Extract of John Wesley's Journal

from his embarking for Georgia to his return to London, 1739. The journal extends from October 14, 1735, to February 1, 1738.

Georgia Scenes

characters, incidents, &c. in the first half century of the Republic, by Augustus Baldwin Longstreet (1840, 2nd ed)

Report on the Brunswick Canal and Rail Road

Glynn County, Georgia. With an appendix containing the charter and commissioners' report, by Loammi Baldwin, 1837

Society

A journal devoted to society, art, literature, and fashion, published in Atlanta, Georgia by the Society Pub. Co., 1890–

Views of Atlanta

and The Cotton State and International Exposition, 1895

Sir John Percival papers

also called: The Egmont Papers, transcripts and manuscripts, 1732–1745.

Transactions of the Trustees of Georgia, 1738–1739

also called: Egmont's Journal, 1738–1739.

Transactions of the Trustees of Georgia, 1741–1744

also called: Egmont's Journal, 1741–1744.

Educational survey of Georgia

by M.L. Duggan, rural school agent, under the direction of the Department of education. M.L. Brittain, state superintendent of schools. Publisher: Atlanta, 1914.

Digital Library of Georgia

Georgia's history and culture found in digitized books, manuscripts, photographs, government documents, newspapers, maps, audio, video, and other resources

Georgia Historical SocietyNew Georgia EncyclopediaJekyll Island Club – Birthplace of the Federal ReserveGeorgia Archives

– official Archives of the State of Georgia * Boston Public Library, Map Center

Maps of Georgia

various dates. * {{Authority control History of Georgia (U.S. state), History of the Southern United States by state, Georgia History of the United States by state, Georgia Former English colonies

British colony

The conflict between Spain and

The conflict between Spain and England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

over control of Georgia began in earnest in about 1670, when the English colony of South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

was founded just north of the missionary provinces of Guale

Guale was a historic Native American chiefdom of Mississippian culture peoples located along the coast of present-day Georgia and the Sea Islands. Spanish Florida established its Roman Catholic missionary system in the chiefdom in the late 16t ...

and Mocama

The Mocama were a Native American people who lived in the coastal areas of what are now northern Florida and southeastern Georgia. A Timucua group, they spoke the dialect known as Mocama, the best-attested dialect of the Timucua language. Their t ...

, part of Spanish Florida. Guale and Mocama, today part of Georgia, lay between Carolina's capital, Charles Town, and Spanish Florida's capital, ''San Agustín''. They were subjected to repeated military invasions by English and Spanish colonists.

The English destroyed the Spanish mission system in Georgia by 1704. The coast of future Georgia was occupied by British-allied Yamasee

The Yamasees (also spelled Yamassees or Yemassees) were a multiethnic confederation of Native Americans who lived in the coastal region of present-day northern coastal Georgia near the Savannah River and later in northeastern Florida. The Yamas ...

American Indians until they were decimated in the Yamasee War

The Yamasee War (also spelled Yamassee or Yemassee) was a conflict fought in South Carolina from 1715 to 1717 between British settlers from the Province of Carolina and the Yamasee and a number of other allied Native American peoples, incl ...

of 1715–1717, by South Carolina colonists and Indian allies. The surviving Yamasee fled to Spanish Florida, leaving the coast of Georgia depopulated. This enabled formation of a new British colony. A few defeated Yamasee remained and later became known as the Yamacraw

The Yamacraw were a Native American band that emerged in the early 18th century, occupying parts of what became Georgia, specifically along the bluffs near the mouth of the Savannah River where it enters the Atlantic Ocean. They were made up of ...

.

English settlement began in the early 1730s after

English settlement began in the early 1730s after James Oglethorpe

James Edward Oglethorpe (22 December 1696 – 30 June 1785) was a British soldier, Member of Parliament, and philanthropist, as well as the founder of the colony of Georgia in what was then British America. As a social reformer, he hoped to r ...

, a Member of Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

, proposed that the area be colonized with the "worthy poor" of England, to provide an alternative to the overcrowded debtors' prisons of the period. Oglethorpe and other English philanthropists

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

secured a royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but s ...

as the Trustees of the colony of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

on June 9, 1732. The misconception of Georgia's having been founded as a debtor or penal colony persists because numerous English convicts were later sentenced to transportation to Georgia as punishment, with the idea that they would provide labor. With the motto, "Not for ourselves, but for others," the Trustees selected colonists for Georgia.

Oglethorpe and the Trustees formulated a contract, multi-tiered plan for the settlement of Georgia (see the Oglethorpe Plan

The Oglethorpe Plan is an urban planning idea that was most notably used in Savannah, Georgia, one of the Thirteen Colonies, in the 18th century. The plan uses a distinctive street network with repeating squares of residential blocks, commercial ...

). The plan framed a system of "agrarian equality" designed to support and perpetuate an economy based on family farming and to prevent the social disintegration they associated with unregulated urbanization. Land ownership was limited to , a grant that included a town lot, a garden plot near town, and a farm. Self-supporting colonists were able to obtain larger grants, but such grants were structured in increments tied to "headrights", that is, the number of indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

for whom the grantee paid transportation to the colony. Survivors who completed their term of indenture (to pay for the transportation and associated costs), would be granted a parcel of land of their own. No person was permitted to acquire additional land through purchase or inheritance.

On February 12, 1733, the first settlers arrived in the ship ''Anne'', at what was to become the city of Savannah. In 1742, the colony was invaded by Spanish forces during the War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

. Oglethorpe mobilized local forces and defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Bloody Marsh

The Battle of Bloody Marsh took place on 7 July 1742 between Spanish and British forces on St. Simons Island, part of the Province of Georgia, resulting in a victory for the British. Part of the War of Jenkins' Ear, the battle was for the Brit ...

. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which ended the war, confirmed the English position in Georgia.

From 1735 to 1750, the trustees of Georgia, unique among Britain's American colonies, prohibited African slavery as a matter of public policy. However, as the growing wealth of the slave-based plantation economy in neighboring South Carolina

)'' Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

demonstrated, slaves were more profitable than other forms of labor available to colonists. In addition, improving economic conditions in Europe meant that fewer whites were willing to immigrate as indentured servants. In addition, many of the whites suffered high mortality rates from the climate, tropical diseases and other hardships of the Lowcountry.

In 1749, the state overturned its ban on slavery. From 1750 to 1775, planters so rapidly imported slaves that the enslaved population grew from less than 500 to approximately 18,000, and they constituted a majority of people in the colony. Some historians have suggested that Africans from rice-growing regions had sophisticated knowledge and material techniques to build the elaborate earthworks of dams, banks, and irrigation systems throughout the Lowcountry that supported rice and indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', m ...

cultivation. Georgia planters imported slaves chiefly from the rice-growing regions of present-day Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

, the Gambia

The Gambia,, ff, Gammbi, ar, غامبيا officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. It is the smallest country within mainland AfricaHoare, Ben. (2002) ''The Kingfisher A-Z Encyclopedia'', Kingfisher Publicatio ...

and Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

. Some recent scholarship argues that the Europeans could have developed the rice culture on their own and that African knowledge played a minor role in the success of its cultivation as a commodity crop. Later planters added sugar cane as a crop.

A scarcity of horses proved to be a constant problem as the colonists tried to develop production of the industry of range cattle. Planters were occasionally able to arrange roundups of wild horses, believed to have escaped from Indian traders or from Spanish Florida.

In 1752, Georgia became a royal colony. Planters from South Carolina, wealthier than the original settlers of Georgia, migrated south and soon dominated the colony. They replicated the customs and institutions of the South Carolina Lowcountry

The Lowcountry (sometimes Low Country or just low country) is a geographic and cultural region along South Carolina's coast, including the Sea Islands. The region includes significant salt marshes and other coastal waterways, making it an impor ...

. Planters had higher rates of absenteeism from their large plantations in the Lowcountry and the Sea Islands than did those in the Upper South. They often took their families to the hills during the summer, the "sick season", when the Lowcountry had high rates of disease carried by mosquitoes, such as malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

and yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

. The decade after the end of Trustee rule was a decade of significant growth. Georgia began to grow after the treaty of 1748 ended fear of further attacks from Spain.

By the 1750s, British settlers lived as far south as Cumberland Island

Cumberland Island, in the southeastern United States, is the largest of the Sea Islands of Georgia. The long-staple Sea Island cotton was first grown here by a local family, the Millers, who helped Eli Whitney develop the cotton gin. With its ...

. This violated the boundaries set by their own government and Spain, which claimed the territory. British settlers living south of the Altamaha River

The Altamaha River is a major river in the U.S. state of Georgia. It flows generally eastward for 137 miles (220 km) from its origin at the confluence of the Oconee River and Ocmulgee River towards the Atlantic Ocean, where it empt ...

frequently engaged in trade with Spanish Florida, which was also illegal according to both governments. Such a ban was essentially unenforceable.

Because of the development of large plantations and commodity crops that required numerous slaves for cultivation and processing, the society of the Georgia coast was more like that of such British colonies as Barbados and Jamaica, than of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. The large plantations were worked by numerous African-born slaves. Many of these Africans, although of different languages and tribes, came from closely related geographic areas of West Africa. The slaves of the 'Rice Coast' of South Carolina and Georgia developed the unique Gullah

The Gullah () are an African American ethnic group who predominantly live in the Lowcountry region of the U.S. states of Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, and North Carolina, within the coastal plain and the Sea Islands. Their language and cultu ...

or Geechee culture (the latter term was more common in Georgia), in which important parts of West African linguistic, religious and cultural heritage were preserved and creolized. This multi-ethnic culture developed throughout the Lowcountry and Sea Islands, where enslaved African Americans later worked at cotton plantations. African-American influences, which also absorbed elements of Native American and European-American culture, was strong on the cuisine and music that became integral parts of southern culture.

Georgia was largely untouched by war during much of Britain's involvement in the Seven Years' War. In North America, hostilities took place along a front in the North, along the border with New France and their allied Native American tribes. Americans later called it the French and Indian War. In 1762 Georgia feared a potential Spanish invasion from Florida, although this did not occur by the time peace was signed at the 1763 Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

. During this period the Anglo-Cherokee War

The Anglo-Cherokee War (1758–1761; in the Cherokee language: the ''"war with those in the red coats"'' or ''"War with the English"''), was also known from the Anglo-European perspective as the Cherokee War, the Cherokee Uprising, or the Cherok ...

began.

Governor James Wright wrote in 1766, thirty-two years after its founding, that Georgia had

No manufactures of the least consequence: a trifling quantity of coarse homespun cloth, wool icand cotton mixed; amongst the poorer sort of people, for their own use, a few cotton and yarn stockings; shoes for our Negroes; and some occasional blacksmith's work. But all our supplies of silk, linens, wool, shoes, stockings, nails, locks, hinges, and tools of every sort ... are all imported from and through Great Britain.

Capitals of Georgia

Georgia has had five different capitals in its history. The first was Savannah, the seat of government duringBritish

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

colonial rule, followed by Augusta, Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

, Milledgeville, and Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

, the capital city from 1868 to the present day. The state legislature has gathered for official meetings in other places, most often in Macon and especially during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

.

American Revolution

Royal governor James Wright was popular. But all of the 13 colonies developed the same strong position defending the traditional rights of Englishmen which they feared London was violating. Georgia and the others moved rapidly towardrepublicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

which rejected monarchy, aristocracy and corruption, and demanded government based on the will of the people. In particular, they demanded "No taxation without representation

"No taxation without representation" is a political slogan that originated in the American Revolution, and which expressed one of the primary grievances of the American colonists for Great Britain. In short, many colonists believed that as they ...

" and rejected the Stamp Act in 1765 and all subsequent royal taxes. More fearsome was the British punishment of Boston after the Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell t ...

. Georgians knew their remote coastal location made them vulnerable.

In August 1774 at a general meeting in Savannah, the people proclaimed, "Protection and allegiance are reciprocal, and under the British Constitution correlative terms; ... the Constitution admits of no taxation without representation." Georgia had few grievances of its own but ideologically supported the patriot cause and expelled the British.

Angered by the news of the battle of Concord, on the eleventh of May 1775, the patriots stormed the royal magazine at Savannah and carried off its ammunition. The customary celebration of the King's birthday on June 4 was turned into a wild demonstration against the King; a liberty pole was erected. Within a month the patriots completely defied royal authority and set up their own government. In June and July, assemblies at Savannah chose a Council of Safety and a Provincial Congress to take control of the government and cooperate with the other colonies. They started raising troops and prepared for war. "In short my lord," wrote Wright to Lord Dartmouth

Earl of Dartmouth is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1711 for William Legge, 2nd Baron Dartmouth.

History

The Legge family descended from Edward Legge, Vice-President of Munster. His eldest son William Legge was ...

on September 16, 1775, "the whole Executive Power is Assumed by them, and the King's Governor remains little Else than Nominally so."

In February 1776, Wright fled to a British warship and the patriots controlled all of Georgia. The new Congress adopted "Rules and Regulations" on April 15, 1776, which can be considered the Constitution of 1776. (Along with the other American colonies, Georgia declared independence in 1776 when its delegates approved and signed the joint Declaration of Independence.) With that declaration, Georgia ceased to be a colony. It was a state with a weak chief executive, the "President and Commander-in-Chief," who was elected by the state Congress for a term of only six months. Archibald Bulloch

Archibald Stobo Bulloch (January 1, 1730 – February 22, 1777) was a lawyer, soldier, and statesman from Georgia during the American Revolution. He was the first governor of Georgia.

He was also a great-grandfather of Martha Bulloch Roosevelt, ...

, President of the two previous Congresses, was elected first President. He bent his efforts to mobilizing and training the militia. The Constitution of 1777 put power in the hands of the elected House of Assembly, which chose the governor; there was no senate and the franchise was open to nearly all white men.

The new state's exposed seaboard position made it a tempting target for the British Navy. Savannah was captured by British and Loyalist forces in 1778, along with some of its hinterland. Enslaved Africans and African Americans chose their independence by escaping to British lines, where they were promised freedom. About one-third of Georgia's 15,000 slaves escaped during the Revolution.

The patriots moved to Augusta. At the Siege of Savannah

The siege of Savannah or the Second Battle of Savannah was an encounter of the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) in 1779. The year before, the city of Savannah, Georgia, had been captured by a British expeditionary corps under Lieutena ...

in 1779, American and French troops (the latter including a company of free men of color from Saint-Domingue, who were mixed race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-ethn ...

) fought unsuccessfully to retake the city. During the final years of the American Revolution, Georgia had a functioning Loyalist colonial government along the coast. Together with New York City, it was the last Loyalist bastion.

An early historian reported:

For forty-two long months had she been a prey to rapine, oppression, fratricidal strife, and poverty. Fear, unrest, the brand, the sword, the tomahawk, had been her portion. In the abstraction emovalof negro slaves, by the burning of dwellings, in the obliteration of plantations, by the destruction of agricultural implements, and by theft of domestic animals and personal effects, it is estimated that at least one half of the available property of the inhabitants had, during this period, been completely swept away. Real estate had depreciated in value. Agriculture was at a stand-still, and there was no money with which to repair these losses and inaugurate a new era of prosperity. The lamentation of widows and orphans, too, were heard in the land. These not only bemoaned their dead, but cried aloud for food. Amid the general depression there was, nevertheless, a deal of gladness in the hearts of the people, a radiant joy, an inspiring hope. Independence had been won.The end of the war saw a new wave of migration to the state, particularly from the frontiers of Virginia and the Carolinas. George Mathews, soon to be governor of Georgia, was instrumental in this migration. Georgia ratified the U.S. Constitution on January 2, 1788.

The original eight counties of Georgia were

The original eight counties of Georgia were Burke

Burke is an Anglo-Norman Irish surname, deriving from the ancient Anglo-Norman and Hiberno-Norman noble dynasty, the House of Burgh. In Ireland, the descendants of William de Burgh (–1206) had the surname ''de Burgh'' which was gaelicised ...

, Camden, Chatham

Chatham may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions Canada

* Chatham Islands (British Columbia)

* Chatham Sound, British Columbia

* Chatham, New Brunswick, a former town, now a neighbourhood of Miramichi

* Chatham (electoral district), New Brunswic ...

, Effingham, Glynn

Glynn () is a small village and civil parish in the Mid and East Antrim Borough Council area of County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It lies a short distance south of Larne, on the shore of Larne Lough. Glynn had a population of 2,027 people in th ...

, Liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

, Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

and Wilkes. Before these counties were created in 1777, Georgia had been divided into local government units called parishes. Each of these original eight counties is named after members of the British government who had supported the American cause during the revolution. As with South Carolina, most of the Loyalists in Georgia (Georgians who had fought for the British cause during the revolution) stayed in Georgia after the war ended. Leading Georgia patriots such as Archibald Bulloch, Stephen Heard, Lyman Hall, John Houstoun, Samuel Elbert, Edward Telfair and George Mathews were all instrumental in both encouraging the Loyalists to stay and in making sure that they were not mistreated during the peace that followed the war. Screven County had hundreds of first generation Scottish immigrants who had all stayed loyal to the crown during the war, Telfair and Mathews personally asked them to stay. In the city of Savannah, Archibald Bulloch, Stephen Heard, Lyman Hall and John Houstoun all made personal appeals to the loyalists to "stay on" after the war ended and make the best of their lives under the new republican form of government.

Antebellum period

During the 77 years of theAntebellum period

In the history of the Southern United States, the Antebellum Period (from la, ante bellum, lit= before the war) spanned the end of the War of 1812 to the start of the American Civil War in 1861. The Antebellum South was characterized by ...

, the area of Georgia was soon reduced by half from the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

back to the current state line by 1802. The ceded land was added into the Mississippi Territory by 1804, following the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

, with the state of Alabama later created in 1819 to become the west Georgia state line. Also during this period, large cotton plantations dominated the inland areas, while rice farming was popular near the coast. The slave population increased to work the plantations, but the native Cherokee tribe was removed and resettled west in Oklahoma, in the final two decades before the Civil War, as explained further in the paragraphs below.

Reduced state lines

In 1787, the

In 1787, the Treaty of Beaufort

The Treaty of Beaufort, also called the Beaufort Convention, is the treaty that originally set the all-river boundary between the U.S. states of Georgia and South Carolina. It was named for Beaufort, South Carolina, where it was signed in 1787.

...

had established the eastern boundary of Georgia, from the Atlantic seashore up the Savannah River, at South Carolina, to modern day Tugalo Lake (construction to the Tugalo dam was started in 1917 and completed in 1923). Twelve to fourteen miles () of land (inhabited at the time by the Cherokee Nation) separate the lake from the southern boundary of North Carolina. South Carolina ceded its claim to this land (extending all the way to the Pacific Ocean) to the federal government.

Georgia maintained a claim on western land from 31° N to 35° N, the southern part of which overlapped with the Mississippi Territory created from part of Spanish Florida in 1798. Following a series of land scandals, Georgia ceded its claims in 1802, fixing its present western boundary. In 1804, the federal government added the cession to the Mississippi Territory.

The Treaty of 1816 fixed the present-day northern boundary between Georgia and South Carolina at the Chattooga River

The Chattooga River (also spelled Chatooga, Chatuga, and Chautaga, variant name Guinekelokee River) is the main tributary of the Tugaloo River.

Water course

The headwaters of the Chattooga River are located southwest of Cashiers, North Carol ...

, proceeding northwest from the lake. The Mississippi Territory was split on December 10, 1817, to form the U.S. state of Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

and the Alabama Territory

The Territory of Alabama (sometimes Alabama Territory) was an organized incorporated territory of the United States. The Alabama Territory was carved from the Mississippi Territory on August 15, 1817 and lasted until December 14, 1819, when it ...

for 2 years; then in December 1819, the new state of Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

became the western boundary of Georgia.

Indian relocation

After the Creek War (corresponding with theWar of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

), some Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsTreaty of Fort Jackson

The Treaty of Fort Jackson (also known as the Treaty with the Creeks, 1814) was signed on August 9, 1814 at Fort Jackson near Wetumpka, Alabama following the defeat of the Red Stick (Upper Creek) resistance by United States allied forces at ...

. Under this treaty, General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

forced the Creek confederacy to surrender more than 21 million acres in what is now southern Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

and central Alabama. On February 12, 1825, William McIntosh

William McIntosh (1775 – April 30, 1825),Hoxie, Frederick (1996)pp. 367-369/ref> was also commonly known as ''Tustunnuggee Hutke'' (White Warrior), was one of the most prominent chiefs of the Creek Nation between the turn of the nineteenth cen ...

and other chiefs signed the Treaty of Indian Springs, which gave up most of the remaining Creek lands in Georgia. After the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

ratified the treaty, McIntosh was assassinated on April 30, 1825, by Creeks led by Menawa.

In 1829, gold was discovered in the north Georgia mountains, resulting in the Georgia Gold Rush

The Georgia Gold Rush was the second significant gold rush in the United States and the first in Georgia, and overshadowed the previous rush in North Carolina. It started in 1829 in present-day Lumpkin County near the county seat, Dahlonega, an ...

, the second gold rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New ...

in U.S. history. A federal mint was established in Dahlonega, Georgia

The city of Dahlonega () is the county seat of Lumpkin County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 5,242, and in 2018 the population was estimated to be 6,884.

Dahlonega is located at the north end of ...

, and continued to operate until 1861. During the early 1800s, Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

Indians owned their ancestral land, operated their own government with a written constitution, and did not recognize the authority of the state of Georgia. An influx of white settlers pressured the U.S. government to expel them. The dispute culminated in the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

of 1830, under which all eastern tribes were sent west to Indian reservations

An Indian reservation is an area of land held and governed by a federally recognized Native American tribal nation whose government is accountable to the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs and not to the state government in which it ...

in present-day Oklahoma. In Worcester v. Georgia, the Supreme Court in 1832 ruled that states were not permitted to redraw the boundaries of Indian lands, but President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

and the state of Georgia ignored the ruling.

Escalating tensions with Creek tribes erupted into open war with the United States following the destruction of the village of Roanoke, Georgia, located along the Chattahoochee River on the boundary between Creek and American territory, in May 1836. During the so-called "Creek War of 1836

The Creek War of 1836, also known as the Second Creek War or Creek Alabama Uprising, was a conflict in Alabama at the time of Indian Removal between the Muscogee Creek people and non-native land speculators and squatters.

Although the Creek ...

" Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Lewis Cass dispatched General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

to end the violence by forcibly removing the Creeks to the Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River.

In 1838, Andrew Jackson's successor, President Martin van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he ...

dispatched federal troops to round up the Cherokee and deport them west of the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

. This forced relocation, beginning in White County, became known as the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the " Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

and led to the death of over 4,000 Cherokees.

Land allocations

In 1794, Eli Whitney, aMassachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

-born artisan residing in Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the British colonial capital of the Province of Georgia and later t ...

, had patented a cotton gin, mechanizing the separation of cotton fibres from their seeds. The Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

had resulted in the mechanized spinning and weaving of cloth in the world's first factories in the north of England. Fueled by the soaring demands of British textile manufacturers, King Cotton

"King Cotton" is a slogan that summarized the strategy used before the American Civil War (of 1861–1865) by secessionists in the southern states (the future Confederate States of America) to claim the feasibility of secession and to prove ther ...

quickly came to dominate Georgia and the other southern states. Although Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...