Alva Belmont on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alva Erskine Belmont (née Smith; January 17, 1853 – January 26, 1933), known as Alva Vanderbilt from 1875 to 1896, was an American multi-millionaire socialite and

Alva Erskine Smith was born on January 17, 1853, at 201 Government Street in

Alva Erskine Smith was born on January 17, 1853, at 201 Government Street in

At a party for one of

At a party for one of

Determined to bring the Vanderbilt family the social status that she felt it deserved, Vanderbilt christened the Fifth Avenue chateau—placed between 5th avenue and 52nd Street, occupying a city block—in March 1883 with a masquerade ball for 1000 guests. "The

Determined to bring the Vanderbilt family the social status that she felt it deserved, Vanderbilt christened the Fifth Avenue chateau—placed between 5th avenue and 52nd Street, occupying a city block—in March 1883 with a masquerade ball for 1000 guests. "The

Alva Vanderbilt shocked society in March 1895 when she divorced her husband who had long been unfaithful, at a time when divorce was rare among the elite, and received a large financial settlement said to be in excess of $10 million, in addition to several estates. She already owned

Alva Vanderbilt shocked society in March 1895 when she divorced her husband who had long been unfaithful, at a time when divorce was rare among the elite, and received a large financial settlement said to be in excess of $10 million, in addition to several estates. She already owned

Drawn further into the suffrage movement by Anna Shaw, Belmont donated large sums to the movement, both in the

Drawn further into the suffrage movement by Anna Shaw, Belmont donated large sums to the movement, both in the  By this time, organized suffrage activity was centered on educated, middle-class white women, who were often reluctant to accept immigrants, African Americans, and the working class into their ranks. Belmont's efforts only partially broke with this tradition. In 1910, Belmont initiated the first attempt to integrate the enfranchisement movement in New York. Working with leading clubwomen in the African American community, like S. J. S. Garnet, F. R. Keyser, Marie C. Lawton and Irene Moorman, she encouraged them to form a Black branch of her Political Equality League. She established its first "suffrage settlement house" in

By this time, organized suffrage activity was centered on educated, middle-class white women, who were often reluctant to accept immigrants, African Americans, and the working class into their ranks. Belmont's efforts only partially broke with this tradition. In 1910, Belmont initiated the first attempt to integrate the enfranchisement movement in New York. Working with leading clubwomen in the African American community, like S. J. S. Garnet, F. R. Keyser, Marie C. Lawton and Irene Moorman, she encouraged them to form a Black branch of her Political Equality League. She established its first "suffrage settlement house" in  The

The

During Alva Belmont's lifetime she built, helped design, and owned many mansions. At one point she owned nine. She was a friend and frequent patron of

During Alva Belmont's lifetime she built, helped design, and owned many mansions. At one point she owned nine. She was a friend and frequent patron of

In 1878, Hunt began work on their Queen Anne style retreat on

In 1878, Hunt began work on their Queen Anne style retreat on

In 1899 she and Oliver bought the corner of 477 Madison Avenue and 51st Street in Manhattan. The mansion became known as the Mrs. O. H. P. Belmont House. The neoclassical three-story townhouse, designed by Hunt & Hunt, had a limestone facade and interior rooms in an eclectic mix of styles. Construction was still underway when Oliver Belmont died, when Alva announced that she would build an addition that was an exact reproduction of the Gothic Room in Belcourt, to house her late husband's collection of medieval and early Renaissance armor. The room, dubbed The Armory, measured and was the largest room in the house. She and her youngest son, Harold, moved into the house in 1909. The Armory would later be used as a lecture hall for women suffragists. She sold the townhouse in 1923.

In 1899 she and Oliver bought the corner of 477 Madison Avenue and 51st Street in Manhattan. The mansion became known as the Mrs. O. H. P. Belmont House. The neoclassical three-story townhouse, designed by Hunt & Hunt, had a limestone facade and interior rooms in an eclectic mix of styles. Construction was still underway when Oliver Belmont died, when Alva announced that she would build an addition that was an exact reproduction of the Gothic Room in Belcourt, to house her late husband's collection of medieval and early Renaissance armor. The room, dubbed The Armory, measured and was the largest room in the house. She and her youngest son, Harold, moved into the house in 1909. The Armory would later be used as a lecture hall for women suffragists. She sold the townhouse in 1923.

Prior to the construction of their new Manhattan mansion, the Belmonts had another neoclassical mansion,

Prior to the construction of their new Manhattan mansion, the Belmonts had another neoclassical mansion,

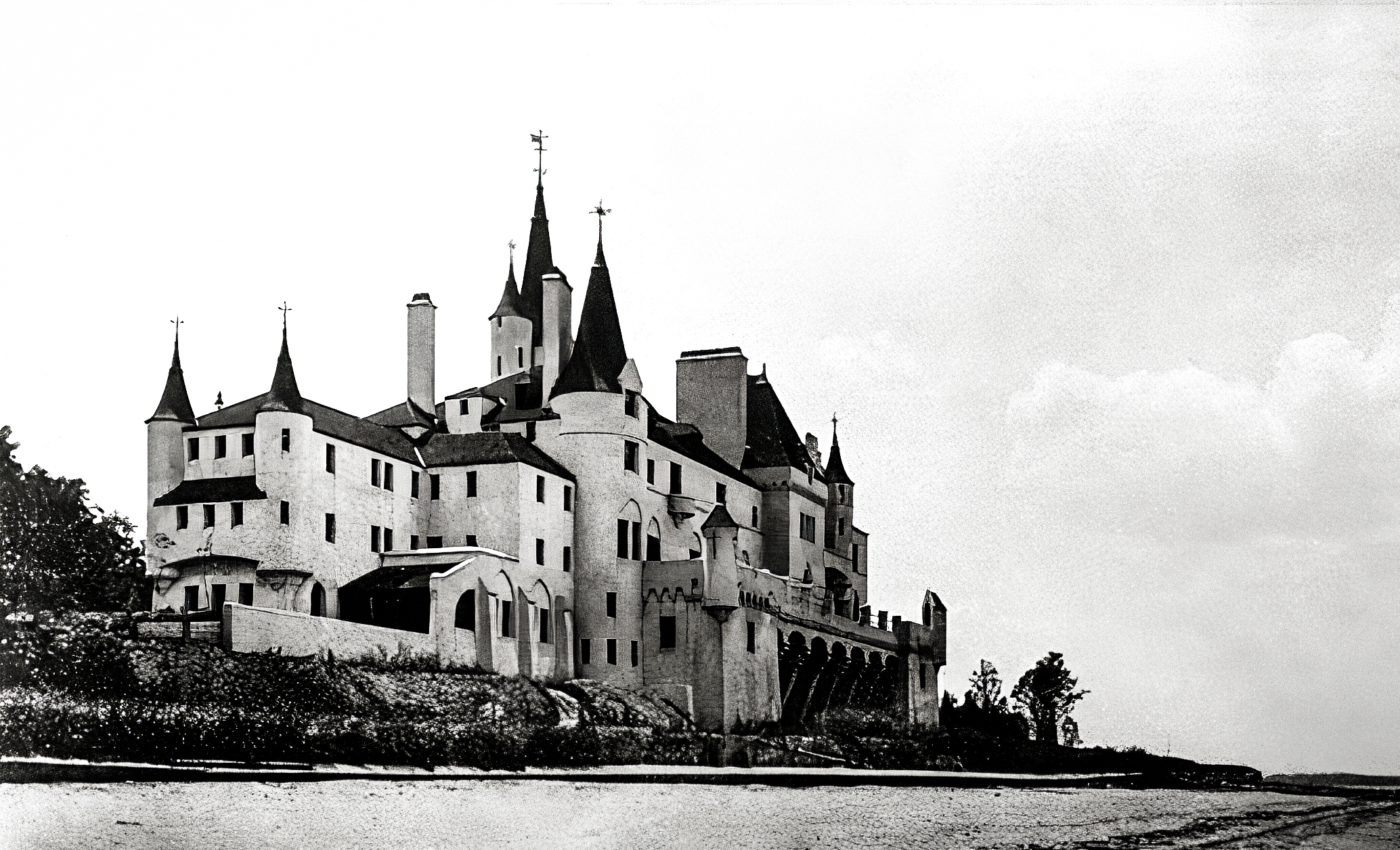

Belmont's last new mansion in the United States was built on Long Island's North Shore. This one, Beacon Towers, has been described by scholars as a pure Gothic fantasy. It was also designed by Hunt & Hunt and was built from 1917 to 1918 in Sands Point. In 1925 Belmont closed the castle permanently; it was sold to

Belmont's last new mansion in the United States was built on Long Island's North Shore. This one, Beacon Towers, has been described by scholars as a pure Gothic fantasy. It was also designed by Hunt & Hunt and was built from 1917 to 1918 in Sands Point. In 1925 Belmont closed the castle permanently; it was sold to

Long Island's Rebels With a Cause

from ''

Women in Philanthropy

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Belmont, Alva 1853 births 1933 deaths Activists from Alabama American feminists American socialites American suffragists Alva 1853 Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) Gilded Age National Woman's Party activists People from East Meadow, New York People from Mobile, Alabama Progressive Era in the United States

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

activist. She was noted for her energy, intelligence, strong opinions, and willingness to challenge convention.

In 1909, she founded the Political Equality League to get votes for suffrage-supporting New York State

New York, officially the State of New York, is a state in the Northeastern United States. It is often called New York State to distinguish it from its largest city, New York City. With a total area of , New York is the 27th-largest U.S. sta ...

politicians, wrote articles for newspapers, and joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National ...

(NAWSA). She later formed her own Political Equality League to seek broad support for suffrage in neighborhoods throughout New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, and, as its president, led its division of New York City's 1912 Women's Votes Parade. In 1916, she was one of the founders of the National Woman's Party

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NW ...

and organized the first picketing ever to take place before the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

, in January 1917. She was elected president of the National Woman's Party

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NW ...

, an office she held until her death.

She was married twice, to socially prominent New York City millionaires William Kissam Vanderbilt

William Kissam "Willie" Vanderbilt I (December 12, 1849 – July 22, 1920) was an American heir, businessman, philanthropist and horsebreeder. Born into the Vanderbilt family, he managed his family's railroad investments.

Early life

William Kiss ...

, with whom she had three children, and Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont. Alva was known for her many building projects, including: the Petit Chateau in New York; the Marble House

Marble House, a Gilded Age mansion located at 596 Bellevue Avenue in Newport, Rhode Island, was built from 1888 to 1892 as a summer cottage for Alva and William Kissam Vanderbilt and was designed by Richard Morris Hunt in the Beaux Arts style ...

in Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

; the Belmont House in New York; Brookholt

Brookholt was a Gilded Age mansion on Front Street in East Meadow, Long Island, New York. It was built for Oliver and Alva Belmont in 1897. Designed by Richard Howland Hunt, the house was built in the Colonial Revival-style, rendered in wood. ...

in Long Island; and Beacon Towers in Sands Point, New York

Sands Point is a village located at the tip of the Cow Neck Peninsula in the Town of North Hempstead, in Nassau County, on the North Shore of Long Island, in New York, United States. It is considered part of the Greater Port Washington area, ...

.

On "Equal Pay Day," April 12, 2016, Belmont was honored when President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

established the Belmont-Paul Women's Equality National Monument in Washington, D.C.

Early life

Alva Erskine Smith was born on January 17, 1853, at 201 Government Street in

Alva Erskine Smith was born on January 17, 1853, at 201 Government Street in Mobile, Alabama

Mobile ( , ) is a city and the county seat of Mobile County, Alabama, United States. The population within the city limits was 187,041 at the 2020 census, down from 195,111 at the 2010 census. It is the fourth-most-populous city in Alabama ...

, to Murray Forbes Smith

Murray Forbes Smith (July 21, 1814 – May 4, 1875) was an American commission merchant best known as the father of Alva Belmont.

Early life

Smith was born on July 21, 1814 in Dumfries, Virginia. He was a son of Edinburgh born George Smith (1765� ...

, a and Phoebe Ann Desha. Smith was the son of George Smith and Delia Forbes of Dumfries, Virginia

Dumfries, officially the Town of Dumfries, is a town in Prince William County, Virginia. The population was 4,961 at the 2010 United States Census.

Geography

Dumfries is located at (38.567853, −77.324591).

According to the United States ...

. Phoebe Desha was the daughter of US Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

Robert Desha

Robert Desha (January 14, 1791February 6, 1849) was an American politician who represented Tennessee's 5th Congressional district in the United States House of Representatives.

Early life

Desha was born near Gallatin in the Southwest Territory ...

and Eleanor Shelby, both originally from Sumner County, Tennessee

Sumner County is a county located on the central northern border of the U.S. state of Tennessee, in what is called Middle Tennessee.

As of the 2020 census, the population was 196,281. Its county seat is Gallatin, and its largest city is Hen ...

.Patterson, Jerry E. ''The Vanderbilts.'', pages 120–121. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1989.

Alva was one of six children. Two of her sisters, Alice and Eleanor, both died as children before she was born. Her brother, Murray Forbes Smith, Jr. died in 1857 and was buried in Magnolia Cemetery in Mobile. Two other sisters, Armide Vogel Smith and Mary Virginia "Jennie" Smith, were her only siblings to survive into adulthood. Jennie first married Fernando Yznaga

Fernando Alfonso Yznaga del Valle (October 16, 1850 – March 6, 1901) was a Cuban American banker who was one of the best-known men of New York and foreign society and club life. Described as "one of the most entertaining of men, very clever at e ...

, the brother of Alva's childhood best friend, Consuelo Yznaga, Duchess of Manchester. Following a divorce from Fernando in 1886, Jennie remarried, to William George Tiffany.

As a child, Alva summered with her parents in Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

, and accompanied them on European vacations. In 1859, the Smiths left Mobile and relocated to New York City, where they briefly settled in Madison Square

Madison Square is a public square formed by the intersection of Fifth Avenue and Broadway at 23rd Street in the New York City borough of Manhattan. The square was named for Founding Father James Madison, fourth President of the United S ...

. When Murray went to Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, to conduct his business, her mother, Phoebe Smith, moved to Paris where Alva attended a private boarding school in Neuilly-sur-Seine

Neuilly-sur-Seine (; literally 'Neuilly on Seine'), also known simply as Neuilly, is a commune in the department of Hauts-de-Seine in France, just west of Paris. Immediately adjacent to the city, the area is composed of mostly select residentia ...

. After the Civil War, the Smith family returned to New York, where Phoebe died in 1871.

Personal life

At a party for one of

At a party for one of William Henry Vanderbilt

William Henry Vanderbilt (May 8, 1821 – December 8, 1885) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was the eldest son of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, an heir to his fortune and a prominent member of the Vanderbilt family. Vanderbi ...

's daughters, Smith's best friend, Consuelo Yznaga introduced her to William Kissam Vanderbilt

William Kissam "Willie" Vanderbilt I (December 12, 1849 – July 22, 1920) was an American heir, businessman, philanthropist and horsebreeder. Born into the Vanderbilt family, he managed his family's railroad investments.

Early life

William Kiss ...

, grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt

Cornelius Vanderbilt (May 27, 1794 – January 4, 1877), nicknamed "the Commodore", was an American business magnate who built his wealth in railroads and shipping. After working with his father's business, Vanderbilt worked his way into lead ...

. On April 20, 1875, William and Alva were married at Calvary Church in New York City.

The couple had three children:

* Consuelo Vanderbilt

Consuelo Vanderbilt-Balsan (formerly Consuelo Spencer-Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough; born Consuelo Vanderbilt; March 2, 1877 – December 6, 1964) was a socialite and a member of the prominent American Vanderbilt family. Her first marriage ...

(March 2, 1877 – December 6, 1964)

* William Kissam Vanderbilt II

William Kissam Vanderbilt II (October 26, 1878 – January 8, 1944) was an American motor racing enthusiast and yachtsman, and a member of the prominent Vanderbilt family.

Early life

He was born on October 26, 1878, in New York City, the seco ...

(October 26, 1878 – January 8, 1944)

* Harold Stirling Vanderbilt (July 6, 1884 – July 4, 1970)

Alva maneuvered Consuelo into marrying Charles Spencer-Churchill, 9th Duke of Marlborough

Charles Richard John Spencer-Churchill, 9th Duke of Marlborough, (13 November 1871 – 30 June 1934), styled Earl of Sunderland until 1883 and Marquess of Blandford between 1883 and 1892, was a British soldier and Conservative politician, and a ...

, on November 6, 1895. The marriage was annulled much later, at the Duke's request and Consuelo's assent, in May 1921. The annulment was fully supported by Alva, who testified that she had forced Consuelo into the marriage. By this time Consuelo and her mother enjoyed a closer, easier relationship. Consuelo married Jacques Balsan, a French aeronautics pioneer. William Kissam II became president of the New York Central Railroad Company

The New York Central Railroad was a railroad primarily operating in the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The railroad primarily connected greater New York and Boston in the east with Chicago and St. Louis in the Mid ...

on his father's death in 1920. Harold Stirling graduated from Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each c ...

in 1910, then joined his father at the New York Central Railroad Company. He remained the only active representative of the Vanderbilt family in the New York Central Railroad after his brother's death, serving as a director and member of the executive committee until 1954.

Rise in society

Balls and dances, the Fifth Avenue chateau

Determined to bring the Vanderbilt family the social status that she felt it deserved, Vanderbilt christened the Fifth Avenue chateau—placed between 5th avenue and 52nd Street, occupying a city block—in March 1883 with a masquerade ball for 1000 guests. "The

Determined to bring the Vanderbilt family the social status that she felt it deserved, Vanderbilt christened the Fifth Avenue chateau—placed between 5th avenue and 52nd Street, occupying a city block—in March 1883 with a masquerade ball for 1000 guests. "The New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under pub ...

speculated that Alva’s party cost t leastmore than a quarter of a million dollars, more than $5 million in today’s dollars" wrote Roark et al in 2020.

An oft-repeated story tells that Vanderbilt felt she had been snubbed by Caroline Astor, queen of " The 400" elite of New York society, so she purposely neglected to send an invitation to her housewarming ball

A housewarming party is a party traditionally held soon after moving into a new residence. It is an occasion for the hosts to present their new home to their friends, post-moving, and for friends to give gifts to furnish the new home. House-warm ...

, a dress ball of about 750 guests, to Astor's popular daughter, Carrie. Supposedly, this forced Astor to come calling, in order to secure an invitation to the ball for her daughter.

Astor did in fact pay a social call on Vanderbilt and she and her daughter were guests at the ball, effectively giving the Vanderbilt family society's official acceptance (Vanderbilt and Astor were observed at the ball in animated conversation). "We have no right to exclude those whom this great country has brought forward," Astor conceded, "The time has come for the Vanderbilts."

Triumphant, Alva dressed as a venetian noble to the ball, but her sister-in-law Alice

Alice may refer to:

* Alice (name), most often a feminine given name, but also used as a surname

Literature

* Alice (''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''), a character in books by Lewis Carroll

* ''Alice'' series, children's and teen books by ...

outdid her, in a costume highlighting a then brand-new invention: the electric light. Her white satin evening dress, since named the Electric Light dress

The Electric Light dress was a masquerade gown made of gold and silver thread that was designed by Charles Frederick Worth for Alice Claypoole Vanderbilt. It was made for a masquerade ball that was held in New York City on March 26, 1883. The ball ...

, was studded with glass beads in a lightning bolt pattern and caused a stir in the press.

The chief effect of the ball was to raise the bar on society entertainments in New York to heights of extravagance and expense that had not been previously seen.

Yachts, opera, "cottages"

Unable to get an opera box at the Academy of Music, whose directors were loath to admit members of newly wealthy families into their circle, she was among those people instrumental in 1883 in founding theMetropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera (commonly known as the Met) is an American opera company based in New York City, resident at the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, currently situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The company is opera ...

, then based at the Metropolitan Opera House. The Metropolitan Opera long outlasted the Academy and continues to the present day.

In 1886, after her husband inherited $65 million from his father's estate, Alva set her sights on owning a yacht. William had the ''Alva'' commission by Harlan and Hollingsworth

Harlan & Hollingsworth was a Wilmington, Delaware, firm that constructed ships and railroad cars during the 19th century and into the 20th century.

Founding

Mahlon Betts, a carpenter, arrived in Wilmington in 1812. After helping construct man ...

of Wilmington, Delaware, at a cost of $500,000. While J.P. Morgan's yacht ''Corsair'' was 165 feet long, Mrs. Astor's '' Nourmahal'' was 233 feet, and Alva's departed father-in-law's ''North Star'' measured 270 feet, Alva and William's 285-foot yacht was the largest private yacht in the world. The Vanderbilts then toured the Caribbean and Europe in the highest fashion.

This being done, Alva then wanted a "summer cottage" in fashionable Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is an American seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and northeast of New Yor ...

. William commissioned Richard Morris Hunt again, and the elaborate Marble House

Marble House, a Gilded Age mansion located at 596 Bellevue Avenue in Newport, Rhode Island, was built from 1888 to 1892 as a summer cottage for Alva and William Kissam Vanderbilt and was designed by Richard Morris Hunt in the Beaux Arts style ...

was built next door to Mrs. Astor's Beechwood.

Alva's ostentatious displays of wealth helped to fuel American public interest in the lives of the rich and powerful, and, coupled with the opulent and decadent lifestyles by America's rich and their apparent disregard for the wellbeing of the working class, helped to also fuel fears that America had become a plutocracy

A plutocracy () or plutarchy is a society that is ruled or controlled by people of great wealth or income. The first known use of the term in English dates from 1631. Unlike most political systems, plutocracy is not rooted in any establishe ...

.

Second marriage

Alva Vanderbilt shocked society in March 1895 when she divorced her husband who had long been unfaithful, at a time when divorce was rare among the elite, and received a large financial settlement said to be in excess of $10 million, in addition to several estates. She already owned

Alva Vanderbilt shocked society in March 1895 when she divorced her husband who had long been unfaithful, at a time when divorce was rare among the elite, and received a large financial settlement said to be in excess of $10 million, in addition to several estates. She already owned Marble House

Marble House, a Gilded Age mansion located at 596 Bellevue Avenue in Newport, Rhode Island, was built from 1888 to 1892 as a summer cottage for Alva and William Kissam Vanderbilt and was designed by Richard Morris Hunt in the Beaux Arts style ...

outright. The grounds for divorce were allegations of William's adultery, although there were some who believed that William had hired a woman to pretend to be his seen mistress so that Alva would divorce him.Patterson, Jerry E. ''The Vanderbilts.'', page 152. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1989.

Alva remarried on January 11, 1896, to Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont, one of her ex-husband's old friends. Oliver had been a friend of the Vanderbilts since the late 1880s and like William was a great fan of yachting and horseraces. He had accompanied them on at least two long voyages aboard their yacht the ''Alva''. Scholars have written that it seems to have been obvious to many that he and Alva were attracted to one another upon their return from one such voyage in 1889. He was the son of August Belmont

August Belmont Sr. (born August Schönberg; December 8, 1813November 24, 1890) was a German-American financier, diplomat, politician and party chairman of the Democratic National Committee, and also a horse-breeder and racehorse owner. He wa ...

, a successful Jewish investment banker

Investment banking pertains to certain activities of a financial services company or a corporate division that consist in advisory-based financial transactions on behalf of individuals, corporations, and governments. Traditionally associated with ...

for the Rothschild family

The Rothschild family ( , ) is a wealthy Ashkenazi Jewish family originally from Frankfurt that rose to prominence with Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744–1812), a court factor to the German Landgraves of Hesse-Kassel in the Free City of Fr ...

, and Caroline Perry, the daughter of Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

Matthew Calbraith Perry.Patterson, Jerry E. ''The Vanderbilts.'', pages 146-148. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1989. Upon Oliver's sudden death in 1908, Alva took on the new cause of the women's suffrage movement

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

after hearing a lecture by Ida Husted Harper

Ida Husted Harper (February 18, 1851 – March 14, 1931) was an American author, journalist, columnist, and suffragist, as well as the author of a three-volume biography of suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony at Anthony's request. Harper also c ...

.

Women's suffrage

Drawn further into the suffrage movement by Anna Shaw, Belmont donated large sums to the movement, both in the

Drawn further into the suffrage movement by Anna Shaw, Belmont donated large sums to the movement, both in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

and United States. In 1909, she founded the Political Equality League to get votes for suffrage-supporting New York State politicians, and wrote articles for newspapers. She gave strong support to labor in the 1909-1910 New York shirtwaist makers strike. She paid the bail of picketers who had been arrested and funded a large rally in the city's Hippodrome

The hippodrome ( el, ἱππόδρομος) was an ancient Greek stadium for horse racing and chariot racing. The name is derived from the Greek words ''hippos'' (ἵππος; "horse") and ''dromos'' (δρόμος; "course"). The term is used i ...

, which she addressed along with Shaw, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National ...

(NAWSA). In 1909 she joined this organization and was named an alternate delegate from New York to the International Women's Suffrage Association meeting in London. There Belmont observed the commitment of Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst (''née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Import ...

and her followers, who would influence the depth and the form of her own personal commitment to the cause. On her return to the United States, she paid for office space on Fifth Avenue that allowed the relocation of NAWSA offices to New York, and she funded its National Press Bureau. At the same time, she formed her own Political Equality League to seek broad support for suffrage in neighborhoods throughout the city, and, as its president, led its division of New York City's 1912 Women's Votes Parade.Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Ha ...

, and she included African American women and immigrants in weekend retreats at Beacon Towers, her Gothic style castle in Sands Point. However, she also contributed to the Southern Woman Suffrage Conference, which refused to admit African Americans.

The

The Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage

The Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage was an American organization formed in 1913 led by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns to campaign for a constitutional amendment guaranteeing women's suffrage. It was inspired by the United Kingdom's suffraget ...

(CU), originally led by Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, w ...

and Lucy Burns, separated from the NAWSA in 1913. At the same time, Belmont was funding Laura Clay's Southern States Woman's Suffrage Conference in Kentucky, because of her Alabama roots. Belmont then merged the Political Equality League into the CU. Now committed to securing the passage of the 19th Amendment, she convened a "Conference of Great Women" at Marble House in the summer of 1914. Belmont's daughter Consuelo, who promoted suffrage and prison reform in England, addressed the gathering, which was followed by the CU's first national meeting. Belmont served on the executive committee of the CU from 1914 to 1916.

In 1915, Belmont chaired the women voters' convention at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. The following year, she and Paul established the National Woman's Party

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NW ...

from the membership of the CU and organized the first picketing ever to take place before the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

, in January 1917. She was elected president of the National Woman's Party, an office she held until her death. The National Woman's Party continued to lobby for new initiatives from the Washington, D.C., headquarters that Belmont had purchased in 1929 for the group, which became the Sewall–Belmont House and Museum. On April 12, 2016, President Barack Obama designated Sewall–Belmont House as the Belmont–Paul Women's Equality National Monument, named for Belmont and Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, w ...

.

Later life and death

From the early 1920s onward, she lived in France most of the time to be near her daughter Consuelo. She restored the 16th century Château d'Augerville and used it as a residence. With Paul, she formed the International Advisory Council of the National Woman's Party and the Auxiliary of American Women abroad. She suffered a stroke in the spring of 1932 that left her partially paralyzed, and she died in Paris of bronchial and heart ailments on January 26, 1933. Her funeral at Saint Thomas Episcopal Church in New York City featured all female pallbearers and a large contingent of suffragists. She is interred with Oliver Belmont in the Belmont Mausoleum at Woodlawn Cemetery inThe Bronx

The Bronx () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the state of New York. It is south of Westchester County; north and east of the New York City borough of Manhattan, across the Harlem River; and north of the New ...

, New York, for which artist Helen Maitland Armstrong designed a set of Renaissance-inspired painted glass windows.

Building programs

During Alva Belmont's lifetime she built, helped design, and owned many mansions. At one point she owned nine. She was a friend and frequent patron of

During Alva Belmont's lifetime she built, helped design, and owned many mansions. At one point she owned nine. She was a friend and frequent patron of Richard Morris Hunt

Richard Morris Hunt (October 31, 1827 – July 31, 1895) was an American architect of the nineteenth century and an eminent figure in the history of American architecture. He helped shape New York City with his designs for the 1902 entrance fa� ...

and was one of the first female members of the American Institute of Architects

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) is a professional organization for architects in the United States. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., the AIA offers education, government advocacy, community redevelopment, and public outreach to s ...

. Following the death of Hunt, she frequently utilized the services of the architectural firm of Hunt & Hunt, formed by the partnership of Richard Morris Hunt's sons, Richard and Joseph.

Petit Chateau

As a young newlywed, Alva Vanderbilt worked from 1878 to 1882 with Richard Morris Hunt to design aFrench Renaissance

The French Renaissance was the cultural and artistic movement in France between the 15th and early 17th centuries. The period is associated with the pan-European Renaissance, a word first used by the French historian Jules Michelet to define th ...

style chateau, known as the Petit Chateau, for her family at 660 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

. A contemporary of Vanderbilt's was quoted as saying that "she loved nothing better than to be knee deep in mortar." She held a costume ball that cost $3 million to open the Fifth Avenue château. It was demolished in 1929.

Marble House

In 1878, Hunt began work on their Queen Anne style retreat on

In 1878, Hunt began work on their Queen Anne style retreat on Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United States and the 18 ...

, Idle Hour. It would be added to almost continuously until 1889 and burned in 1899. William K. Vanderbilt had a new fireproof mansion rebuilt on the estate and it later became the home of now closed Dowling College.

Hunt was again hired to design the neoclassical style Marble House

Marble House, a Gilded Age mansion located at 596 Bellevue Avenue in Newport, Rhode Island, was built from 1888 to 1892 as a summer cottage for Alva and William Kissam Vanderbilt and was designed by Richard Morris Hunt in the Beaux Arts style ...

in Newport, Rhode Island, as William K. Vanderbilt's 39th birthday present and summer "cottage" retreat for Alva. Built from 1888 to 1892, the house was a social landmark that helped spark the transformation of Newport from a relatively relaxed summer colony of wooden houses to the now legendary resort of opulent stone palaces. It was reported to cost $11 million. Marble House was staffed with 36 servants, including butlers, maids, coachmen, and footmen. It was built next door to Caroline Astor's much simpler Beechwood estate.

Belcourt

After her divorce from Vanderbilt and subsequent remarriage to Oliver Belmont, she began extensive renovations to Belmont's sixty-room Newport mansion, Belcourt. The entire first floor was composed of carriage space and a multitude of stables for Belmont's prized horses. Eager to reshape and redesign Belcourt, Alva made changes that transformed the interiors of the mansion into a blend of French and EnglishGothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

and Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

styles.

477 Madison Avenue

In 1899 she and Oliver bought the corner of 477 Madison Avenue and 51st Street in Manhattan. The mansion became known as the Mrs. O. H. P. Belmont House. The neoclassical three-story townhouse, designed by Hunt & Hunt, had a limestone facade and interior rooms in an eclectic mix of styles. Construction was still underway when Oliver Belmont died, when Alva announced that she would build an addition that was an exact reproduction of the Gothic Room in Belcourt, to house her late husband's collection of medieval and early Renaissance armor. The room, dubbed The Armory, measured and was the largest room in the house. She and her youngest son, Harold, moved into the house in 1909. The Armory would later be used as a lecture hall for women suffragists. She sold the townhouse in 1923.

In 1899 she and Oliver bought the corner of 477 Madison Avenue and 51st Street in Manhattan. The mansion became known as the Mrs. O. H. P. Belmont House. The neoclassical three-story townhouse, designed by Hunt & Hunt, had a limestone facade and interior rooms in an eclectic mix of styles. Construction was still underway when Oliver Belmont died, when Alva announced that she would build an addition that was an exact reproduction of the Gothic Room in Belcourt, to house her late husband's collection of medieval and early Renaissance armor. The room, dubbed The Armory, measured and was the largest room in the house. She and her youngest son, Harold, moved into the house in 1909. The Armory would later be used as a lecture hall for women suffragists. She sold the townhouse in 1923.

Brookholt

Prior to the construction of their new Manhattan mansion, the Belmonts had another neoclassical mansion,

Prior to the construction of their new Manhattan mansion, the Belmonts had another neoclassical mansion, Brookholt

Brookholt was a Gilded Age mansion on Front Street in East Meadow, Long Island, New York. It was built for Oliver and Alva Belmont in 1897. Designed by Richard Howland Hunt, the house was built in the Colonial Revival-style, rendered in wood. ...

, built in 1897 in East Meadow

East Meadow is a hamlet and census-designated place (CDP) in the Town of Hempstead in Nassau County, on Long Island, in New York. The population was 38,132 at the 2010 census.

Many residents commute to Manhattan, which is away.

History

In 16 ...

on Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United States and the 18 ...

. It was designed by Hunt & Hunt. Oliver Belmont died there in 1908. For a short period, she operated the estate as Brookholt School of Agriculture for Women

The Brookholt School of Agriculture for Women (also known as Belmont's farm school for girls) was an experimental American farm vocational school for women. Established on April 1, 1911, by Alva Belmont on her Brookholt estate, located in the haml ...

, a training school for female farmers. She sold Brookholt in 1915. The house was later destroyed by fire in 1934.

Mausoleum

Following Oliver Belmont's death, Belmont commissioned a family mausoleum to be built in Woodlawn Cemetery. Again designed by Hunt & Hunt, it was an exacting replica of the original Chapel of Saint Hubert on the grounds of theChâteau d'Amboise

The Château d'Amboise is a château in Amboise, located in the Indre-et-Loire ''département'' of the Loire Valley in France. Confiscated by the monarchy in the 15th century, it became a favoured royal residence and was extensively rebuilt. Kin ...

. It took several years, but construction was completed in 1913.

Beacon Towers

William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

in 1927. He partially remodeled it and then sold it in 1942. It was demolished in 1945. It is thought by some literary scholars to have been part of the inspiration for the home of Jay Gatsby in F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age—a term he popularize ...

's ''The Great Gatsby

''The Great Gatsby'' is a 1925 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Set in the Jazz Age on Long Island, near New York City, the novel depicts first-person narrator Nick Carraway's interactions with mysterious millionaire Jay Gatsby ...

''.

Château d'Augerville

Belmont retired to France in 1923. She had a townhouse in Paris and a villa on theRiviera

''Riviera'' () is an Italian word which means "coastline", ultimately derived from Latin , through Ligurian . It came to be applied as a proper name to the coast of Liguria, in the form ''Riviera ligure'', then shortened in English. The two area ...

. She also purchased the 15th-century Château d'Augerville

The Château d'Augerville is a historic château, situated in the commune of Augerville-la-Rivière, Loiret, France. :fr:Château d'Augerville (Original from Bulletin n°17 de la Société archéologique de Puiseaux, Alain Lespargot, décembre 1989 ...

in Augerville-la-Rivière

Augerville-la-Rivière () is a commune in the Loiret department in north-central France. It is the site of the Château d'Augerville.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Loiret department

The following is the list of the 325 communes of ...

, Loiret

Loiret (; ) is a department in the Centre-Val de Loire region of north-central France. It takes its name from the river Loiret, which is contained wholly within the department. In 2019, Loiret had a population of 680,434.< ...

, in the summer of 1926 and restored it as her primary residence. It had been one of the inspirations for her châteauesque-style 660 Fifth Avenue house and legend had it that the chateau had once belonged to Jacques Cœur

Jacques Cœur (, ; in Bourges – 25 November 1456 in Chios) was a French government official and state-sponsored merchant whose personal fortune became legendary and led to his eventual disgrace. He initiated regular trade routes between Franc ...

, who had left it to his daughter. Her daughter, Consuelo, wrote that she thought these two things had inspired her mother to buy the estate.

Belmont did a great deal of restoration and renovation during her ownership. She had the river flowing through the estate widened because she said, as Consuelo later wrote, "This river is not wide enough." She brought in paving stones from Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, ...

to cover the previously sand-paved great forecourt between the house and the village. She also built a massive neo-Gothic portal gate on the northern entrance road, separating the château and village from the surrounding farmland. Other changes included replacement of the wrought iron staircases and moving the kitchens to the basement. She also added a bowling alley

A bowling alley (also known as a bowling center, bowling lounge, bowling arena, or historically bowling club) is a facility where the sport of bowling is played. It can be a dedicated facility or part of another, such as a clubhouse or dwelling ...

in one of the houses on the estate. After her death in 1933, the chateau was left to Consuelo, who sold it to a Swiss company in the winter of 1937.

References

General bibliography

* Lasch, Christopher. "Alva Erskine Smith Vanderbilt Belmont," in Edward James, ed., ''Notable American Women'' (1971) * ''The Vanderbilt Women: Dynasty of Wealth, Glamour and Tragedy'' Clarice Stasz. New York, St. Martin's Press, 1991; iUniverse, 2000. * ''Fortune's Children: The Fall of the House of Vanderbilt'' Arthur T Vanderbilt. Morrow, 1989. * ''Consuelo and Alva Vanderbilt: The Story of a Daughter and a Mother in the Gilded Age.'' Amanda Mackenzie Stuart. New York: Harper Collins, 2005. * ''The Barons of Newport: A Guide to the Gilded Age.'' Terrence Gavan. Newport: Pineapple Publications, 1998.External links

Long Island's Rebels With a Cause

from ''

New York Newsday

''New York Newsday'' was an American daily newspaper that primarily served New York City and was sold throughout the New York metropolitan area. The paper, established in 1985, was a New York City-specific offshoot of '' Newsday'', a Long Isl ...

''

Women in Philanthropy

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Belmont, Alva 1853 births 1933 deaths Activists from Alabama American feminists American socialites American suffragists Alva 1853 Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) Gilded Age National Woman's Party activists People from East Meadow, New York People from Mobile, Alabama Progressive Era in the United States

Alva Belmont

Alva Erskine Belmont (née Smith; January 17, 1853 – January 26, 1933), known as Alva Vanderbilt from 1875 to 1896, was an American multi-millionaire socialite and women's suffrage activist. She was noted for her energy, intelligence, strong ...

People from Midtown Manhattan