Alanson B. Houghton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

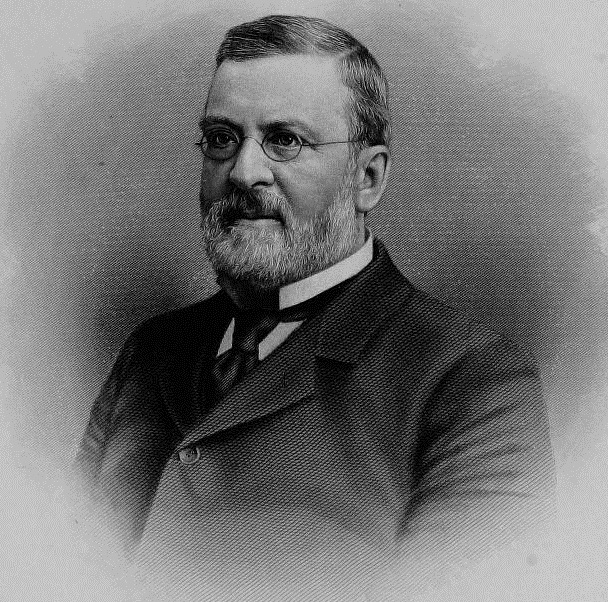

Alanson Bigelow Houghton (October 10, 1863 – September 15, 1941) was an American businessman, politician, and diplomat who served as a

Alanson B. Houghton was born on October 10, 1863, in

Alanson B. Houghton was born on October 10, 1863, in

online

on Houghton's role in Europe, pp 25–42.. * Matthews, Jeffrey J. ''Alanson B. Houghton: Ambassador in the New Era.'' Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources Inc., 2004. Retrieved on 2008-02-15 *Kestenbaum, Lawrence.

*Harvard Business School.

Leadership database

Congressman

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivalen ...

and Ambassador. He was a member of the Republican Party.

Early life and business career

Alanson B. Houghton was born on October 10, 1863, in

Alanson B. Houghton was born on October 10, 1863, in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, Middlesex County, Massachusetts. He was the son of Ellen Ann (Bigelow) and Amory Houghton, Jr. (1837–1909), who would later be President of the Corning Glass Works

Corning Incorporated is an American multinational technology company that specializes in specialty glass, ceramics, and related materials and technologies including advanced optics, primarily for industrial and scientific applications. The co ...

, the company founded by Alanson's grandfather Amory Houghton, Sr. in 1851.

In 1868, his family moved to Corning, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. He attended the Corning Free Academy in Corning and St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire

Concord () is the capital city of the U.S. state of New Hampshire and the seat of Merrimack County. As of the 2020 census the population was 43,976, making it the third largest city in New Hampshire behind Manchester and Nashua.

The village of ...

. Houghton graduated from Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

in 1886 and then pursued postgraduate courses in Europe. He attended graduate school in Göttingen

Göttingen (, , ; nds, Chöttingen) is a college town, university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the Capital (political), capital of Göttingen (district), the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, t ...

, Berlin, and Paris until 1889.

Upon his return to Corning in 1889, Houghton began work for his family's business, Corning Glass

Corning Incorporated is an American multinational technology company that specializes in specialty glass, ceramics, and related materials and technologies including advanced optics, primarily for industrial and scientific applications. The co ...

Works. He served as vice president of the company from 1902 to 1910, and as the company's president from 1910 to 1918. Under Houghton's leadership, the company tripled in size to become one of the largest producers of glass products in the United States. The company manufactured 40% of incandescent light bulbs and 75% of the railway signal glass used in the U.S.

Houghton's interest in and promotion of education, particularly in western New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

state, led to his being appointed a trustee of Hobart College in 1917.

He was a member of the Jekyll Island Club

The Jekyll Island Club was a private club on Jekyll Island, on Georgia's Atlantic coast. It was founded in 1886 when members of an incorporated hunting and recreational club purchased the island for $125,000 (about $3.1 million in 2017) from John E ...

(aka The Millionaires Club) on Jekyll Island, Georgia

Jekyll Island is located off the coast of the U.S. state of Georgia, in Glynn County. It is one of the Sea Islands and one of the Golden Isles of Georgia barrier islands. The island is owned by the State of Georgia and run by a self-sustaining, s ...

, along with J.P. Morgan and William Rockefeller

William Avery Rockefeller Jr. (May 31, 1841 – June 24, 1922) was an American businessman and financier. Rockefeller was a co-founder of Standard Oil along with his elder brother John Davison Rockefeller. He was also part owner of the Anaconda ...

among others.

Politics

Houghton was a presidential elector in the 1904 presidential election. He was also apresidential elector

The United States Electoral College is the group of presidential electors required by the Constitution to form every four years for the sole purpose of appointing the president and vice president. Each state and the District of Columbia appo ...

in 1916

Events

Below, the events of the First World War have the "WWI" prefix.

January

* January 1 – The British Royal Army Medical Corps carries out the first successful blood transfusion, using blood that had been stored and cooled.

* ...

, voting for the Republican candidates Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

and Charles W. Fairbanks

Charles Warren Fairbanks (May 11, 1852 – June 4, 1918) was an American politician who served as a senator from Indiana from 1897 to 1905 and the 26th vice president of the United States from 1905 to 1909. He was also the Republican vice presid ...

.

In 1918, Alanson B. Houghton defeated incumbent Congressman Harry H. Pratt in the Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

primary. He went on to win the general election and joined the Sixty-sixth Congress, representing New York's 37th Congressional District. In 1920, Houghton garnered 68% of the vote to win reelection over Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

Charles R. Durham and Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

Francis Toomey. Houghton took office on March 4, 1919. During his two terms in the House, Houghton served on the Foreign Affairs and Ways and Means committees.

Diplomacy

Houghton, having studied in prewar Germany, admired German culture and understood German politics. His appointment was approved by the U.S. Senate and well received by theWeimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

. On February 28, 1922, Houghton resigned his House seat to accept appointment from President Warren G. Harding as the U.S. Ambassador to Germany. Houghton believed that world peace, European stability, and American prosperity depended upon a reconstruction of Europe's economy and political system. He saw his role as promoting American political engagement with Europe. He overcame domestic opposition, and disinterest in Washington. He quickly realized that the central issues of the day were all entangled in economics, especially war debts owed by the Allies to the United States, reparations owed by Germany to the Allies, worldwide inflation, and international trade and investment. Solutions, he believed, required new policies by Washington and close cooperation with Britain and Germany. He was a leading promoter of the Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was a plan in 1924 that successfully resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay. It ended a crisis in European diplomacy following Wor ...

.

On February 24, 1925, President Calvin Coolidge appointed Houghton as the U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain

The United States ambassador to the United Kingdom (known formally as the ambassador of the United States to the Court of St James's) is the official representative of the president of the United States and the American government to the monarch ...

. Houghton assumed the post on April 6, 1925, and served until April 27, 1929. Houghton's service in both Germany and England gave him a unique ability to address the issue of the war reparations

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war.

History

Making one party pay a war indemnity is a common practice with a long history.

R ...

Germany owed to its World War I opponents, England being one of them. Houghton laid some of the groundwork for the Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was a plan in 1924 that successfully resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay. It ended a crisis in European diplomacy following Wor ...

, named after then U.S. Vice President Charles G. Dawes

Charles Gates Dawes (August 27, 1865 – April 23, 1951) was an American banker, general, diplomat, composer, and Republican politician who was the 30th vice president of the United States from 1925 to 1929 under Calvin Coolidge. He was a co-reci ...

, who would be Houghton's successor as Ambassador to Great Britain.

In 1928

Events January

* January – British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith reports the results of Griffith's experiment, indirectly proving the existence of DNA.

* January 1 – Eastern Bloc emigration and defection: Boris Bazhanov, J ...

, Houghton ran for the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

from New York against first-term incumbent Royal S. Copeland

Royal Samuel Copeland (November 7, 1868June 17, 1938), a United States Senator from New York from 1923 until 1938, was an academic, homeopathic physician, and politician. He held elected offices in both Michigan (as a Republican) and New York ...

, a Democrat. Houghton lost by just over one percentage point.

Death and legacy

After his loss in the 1928 Senate race, Houghton returned to managing the Corning Glass Works. He was a founding member of the Board of Trustees of theInstitute for Advanced Study

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), located in Princeton, New Jersey, in the United States, is an independent center for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry. It has served as the academic home of internationally preeminent scholar ...

, in Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton is a municipality with a borough form of government in Mercer County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton and Princeton Township, both of whi ...

, serving as Chairman until his death in 1941. He also was an original standing committee member of the Foundation for the Study of Cycles

The Foundation for the Study of Cycles (FSC) is an international nonprofit organization that fosters, promotes, and conducts scientific research in respect to rhythmic and periodic fluctuations in any branch of science. It was incorporated on Janu ...

and served as vice president of the American Peace Society, which publishes ''World Affairs

''World Affairs'' is an American quarterly journal covering international relations. At one time, it was an official publication of the American Peace Society. The magazine has been published since 1837 and was re-launched in January 2008 as a new ...

'', the oldest U.S. journal on international relations.

Houghton died at his summer home in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts

Dartmouth (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ) is a coastal town in Bristol County, Massachusetts, Bristol County, Massachusetts. Old Dartmouth was the first area of Southeastern Massachusetts to be settled by Europeans, primarily English. Dar ...

, on September 15, 1941. He was interred at Hope Cemetery Annex in Corning, New York

Corning is a city in Steuben County, New York, United States, on the Chemung River. The population was 10,551 at the 2020 census. It is named for Erastus Corning, an Albany financier and railroad executive who was an investor in the company t ...

.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

the Liberty ship

Liberty ships were a class of cargo ship built in the United States during World War II under the Emergency Shipbuilding Program. Though British in concept, the design was adopted by the United States for its simple, low-cost construction. Mass ...

was built in Panama City, Florida

Panama City is a city in and the county seat of Bay County, Florida, United States. Located along U.S. Highway 98 (US 98), it is the largest city between Tallahassee and Pensacola. It is the more populated city of the Panama City–Lynn Ha ...

, and named in his honor.

Houghton's son, Amory Houghton

Amory Houghton (July 27, 1899 – February 21, 1981) served as United States Ambassador to France from 1957 to 1961 and as national president of the Boy Scouts of America. He was chairman of the board of Corning Glass Works (1941–1961). In 195 ...

(1899–1981), served as the United States Ambassador to France

The United States ambassador to France is the official representative of the president of the United States to the president of France. The United States has maintained diplomatic relations with France since the American Revolution. Relations we ...

(1957–1961) under President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

. His grandson, Amo Houghton, was a U.S. Congressman

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

from New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

from 1987 until 2005.

See also

* List of covers of ''Time'' magazine (1920s) – April 5, 1926 * ''The Harvard Monthly

''The Harvard Monthly'' was a literary magazine of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, beginning October 1885 until suspending publication following the Spring 1917 issue.

Formed in the latter months of 1885 by Harvard seniors Will ...

''

References

Further reading

* Jones, Kenneth Paul, ed. ''U.S. Diplomats in Europe, 1919–41'' (ABC-CLIO. 1981online

on Houghton's role in Europe, pp 25–42.. * Matthews, Jeffrey J. ''Alanson B. Houghton: Ambassador in the New Era.'' Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources Inc., 2004. Retrieved on 2008-02-15 *Kestenbaum, Lawrence.

*Harvard Business School.

Leadership database

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Houghton, Alanson B. American business executives Corning Inc. 1863 births 1941 deaths Businesspeople from Cambridge, Massachusetts Ambassadors of the United States to the United Kingdom Ambassadors of the United States to Germany Politicians from Cambridge, Massachusetts Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state) Harvard University alumni Politicians from Corning, New York 1904 United States presidential electors 1916 United States presidential electors People from Dartmouth, Massachusetts 20th-century American diplomats