A.E. Clouston on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Air Commodore Arthur Edmond Clouston, (7 April 1908 – 1 January 1984) was a New Zealand-born British test pilot and senior officer in the

/ref>Middleton 1982

While employed at RAE, Clouston developed a spare time interest in civil aviation, air racing and record-breaking. On 13 April 1936, he displayed his

While employed at RAE, Clouston developed a spare time interest in civil aviation, air racing and record-breaking. On 13 April 1936, he displayed his  In June 1937, he learned that the DH.88 Comet (G-ACSS), that won the 1934

In June 1937, he learned that the DH.88 Comet (G-ACSS), that won the 1934

Clouston, Arthur Edmond (1908–1984)

'. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. * * *

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

. He took part in several air races and record-breaking flights in the 1930s.

Early life

Arthur Edmond Clouston was born on 7 April 1908 atMotueka

Motueka is a town in the South Island of New Zealand, close to the mouth of the Motueka River on the western shore of Tasman Bay / Te Tai-o-Aorere. It is the second largest in the Tasman Region, with a population of as of

The surrounding dis ...

in New Zealand, the son of Robert Edmond Clouston, a mining engineer, and his wife Ruby. Educated at a school in Collingwood, Clouston sought to have an career as a mariner but this was prevented by illness. He instead established a automotive workshop in Westport. The exploits of the Australian aviator Charles Kingsford Smith

Sir Charles Edward Kingsford Smith (9 February 18978 November 1935), nicknamed Smithy, was an Australian aviation pioneer. He piloted the first transpacific flight and the first flight between Australia and New Zealand.

Kingsford Smith was b ...

inspired Clouston to learn to fly at the Marlborough Aero Club at Omaka Aerodrome, near Blenheim. Soon a proficient pilot, in October 1929 he established an altitude record of for the de Havilland Moth.

Early in 1930 Clouston was reprimanded by his instructor for stunting his aircraft without approval during an air pageant at Blenheim. Soon, having qualified as a pilot, he decided to pursue a career with the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

in the United Kingdom. He sold his business and departed the country later in the year.Orange 2004

Military career

When he arrived in the United Kingdom, Clouston found work at theFairey Aviation Company

The Fairey Aviation Company Limited was a British aircraft manufacturer of the first half of the 20th century based in Hayes in Middlesex and Heaton Chapel and RAF Ringway in Cheshire. Notable for the design of a number of important military a ...

while awaiting the processing of his application to the RAF. In October 1930, once some initial concerns over his blood pressure were resolved, Clouston was granted a short service commission in the RAF as a pilot officer

Pilot officer (Plt Off officially in the RAF; in the RAAF and RNZAF; formerly P/O in all services, and still often used in the RAF) is the lowest commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force and the air forces of many other Commonwealth countri ...

. He commenced flying training at No. 3 Flying Training School at RAF Spitalgate

Royal Air Force Spitalgate or more simply RAF Spitalgate formerly known as RFC Grantham and RAF Grantham was a Royal Flying Corps and Royal Air Force station, located south east of the centre of Grantham, Lincolnshire, England fronting onto th ...

. Rated as an exceptional pilot, in April 1931 he was posted to No. 25 Squadron.

Clouston's new unit was based at Hawkinge

Hawkinge ( ) is a town and civil parish in the Folkestone and Hythe district of Kent, England. The original village of Hawkinge is actually just less than a mile (c. 1.3 km) due east of the present village centre; the village of Hawkinge wa ...

and operated the Hawker Fury I fighter biplane, which was particularly aerobatic. The squadron regularly performed in air pageants at Hendon

Hendon is an urban area in the Borough of Barnet, North-West London northwest of Charing Cross. Hendon was an ancient manor and parish in the county of Middlesex and a former borough, the Municipal Borough of Hendon; it has been part of Great ...

and Clouston was soon one of the pilots selected for these displays. In August 1934, having been promoted to flying officer, he was posted to No. 24 Squadron at Northolt.

As his period of service with the RAF drew to a close, Clouston applied for a permanent commission. This was declined and, dissatisfied with the compromise offer of an extension of his short service commission, in October 1935 he ended his commitment to the RAF and transferred to the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

The Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) was established in 1936 to support the preparedness of the U.K. Royal Air Force in the event of another war. The Air Ministry intended it to form a supplement to the Royal Auxiliary Air Force (RAuxAF ...

.

Test pilot

On returning to life as a civilian, Clouston applied to the Air Ministry for a job as atest pilot

A test pilot is an aircraft pilot with additional training to fly and evaluate experimental, newly produced and modified aircraft with specific maneuvers, known as flight test techniques.Stinton, Darrol. ''Flying Qualities and Flight Testing ...

at the Royal Aircraft Establishment

The Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) was a British research establishment, known by several different names during its history, that eventually came under the aegis of the Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom), UK Ministry of Defence (MoD), bef ...

, based at Farnborough. He was successful, and became one of two civilian pilots testing aircraft.

Soon after he had started flying a Cierva C.30 autogiro at Farnborough, he was invited by Raoul Hafner to carry out test flying of the Hafner AR.III in his off-duty time, and Clouston later flew demonstrations of that gyroplane at many aviation events. He conducted official flight test aerodynamics work on aircraft including Parnall Parasol

The Parnall Parasol was an Experimental aircraft, experimental parasol winged aircraft design to measure the aerodynamic forces on wings in flight. Two were built and flown in the early 1930s in the UK.

Design and development

There have always ...

and Miles Falcon

The mile, sometimes the international mile or statute mile to distinguish it from other miles, is a British imperial unit and United States customary unit of distance; both are based on the older English unit of length equal to 5,280 English ...

; ice formation research on Airspeed Courier, Handley Page Heyford

The Handley Page Heyford was a twin-engine biplane bomber designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Handley Page. It holds the distinction of being the last biplane heavy bomber to be operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF).

The ...

and Northrop Gamma

The Northrop Gamma was a single-engine all-metal monoplane cargo aircraft used in the 1930s. Towards the end of its service life, it was developed into the A-17 light bomber.

Design and development

The Gamma was a further development of the su ...

; and anti-intruder wire strike tests with Miles Hawk

The Miles M.2 Hawk was a twin-seat light monoplane designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Miles Aircraft Limited during the 1930s. It is the first of the company's aircraft to attain quantity production.

The Hawk's developm ...

and Fairey P.4/34. In January 1938, he was awarded the Air Force Cross.

In October 1938, Air Vice Marshal Arthur Tedder asked Clouston to conduct test flying of the prototype of the Westland Whirlwind Westland or Westlands may refer to:

Places

*Westlands, an affluent neighbourhood in the city of Nairobi, Kenya

* Westlands, Staffordshire, a suburban area and ward in Newcastle-under-Lyme

*Westland, a peninsula of the Shetland Mainland near Vaila, ...

, in place of Westland test pilots. Clouston piloted its first flight from Yeovil Aerodrome to Boscombe Down

MoD Boscombe Down ' is the home of a military aircraft testing site, on the southeastern outskirts of the town of Amesbury, Wiltshire, England. The site is managed by QinetiQ, the private defence company created as part of the breakup of the Def ...

.Barrass, M. ''Air of Authority''/ref>Middleton 1982

Races and record-breaking flights, 1935–1939

While employed at RAE, Clouston developed a spare time interest in civil aviation, air racing and record-breaking. On 13 April 1936, he displayed his

While employed at RAE, Clouston developed a spare time interest in civil aviation, air racing and record-breaking. On 13 April 1936, he displayed his Aeronca C-3

The Aeronca C-3 was a light plane built by the Aeronca Aircraft, Aeronautical Corporation of America in the United States during the 1930s.

Design and development

Its design was derived from the Aeronca C-2. Introduced in 1931 in aviation, 1931, ...

(G-ADYP) at the Pou-du-Ciel (Flying Flea) rally at Ashingdon

Ashingdon is a village and civil parish in Essex, England. It is located about north of Rochford and is southeast from the county town of Chelmsford. The village lies within Rochford District and the parliamentary constituency of Rayleigh.

A ...

. He test flew several Flying Fleas from Heston Aerodrome

Heston Aerodrome was an airfield located to the west of London, England, operational between 1929 and 1947. It was situated on the border of the Heston and Cranford areas of Hounslow, Middlesex. In September 1938, the British Prime Minister, Ne ...

and from Gravesend Aerodrome. On 30 May 1936, he flew his Aeronca C-3 from Hanworth Aerodrome

London Air Park, also known as Hanworth Air Park, was a grass airfield in the grounds of Hanworth Park House, operational 1917–1919 and 1929–1947. It was on the southeastern edge of Feltham, now part of the London Borough of Hounslow. In th ...

in the London to Isle of Man Race, but missed the final turning point in fog. On 14 June 1936, he flew the Aeronca in the South Coast Race at Shoreham, and came first, but was then disqualified on a technicality. On 11 July 1936, he flew a Miles Falcon (G-AEFB) in the King's Cup Race

The King's Cup air race is a British handicapped cross-country event, which has taken place annually since 1922. It is run by the Royal Aero Club Records Racing and Rally Association.

The King's Cup is one of the most prestigious prizes of the ...

at Hatfield. On 3 August 1936, he borrowed a Flying Flea (G-ADPY), and raced it in the First International Flying Flea Challenge Trophy Race at Ramsgate Airport

Ramsgate Airport was a civil airfield at Ramsgate, Kent, United Kingdom which opened in July 1935. It was briefly taken over by the Royal Air Force in the Second World War, becoming RAF Ramsgate. The airfield was then closed and obstructed to ...

, but retired when an oil pipe fractured.Lewis 1970

On 29 September 1936, he took off from Portsmouth Airport in his Miles Hawk Speed Six (G-ADOD), at the start of the Schlesinger Race

The Schlesinger Race, also known as the ''"Rand Race"'', the ''"Portsmouth – Johannesburg Race"'' or more commonly the 'African Air Race', took place in September 1936. The Royal Aero Club announced the race on behalf of Isidore William Sch ...

to Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a megacity, and is one of the 100 largest urban areas in the world. According to Demo ...

. He was one of nine starters, but force landed 200 miles short of the race destination, and was the last of eight entries that failed to reach Johannesburg. On 29 May 1937, he flew a Miles Hawk Major (G-ADGE) from Hanworth in the London to Isle of Man Race.

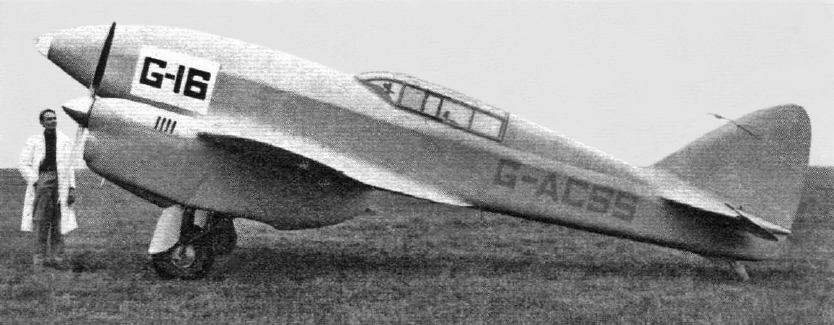

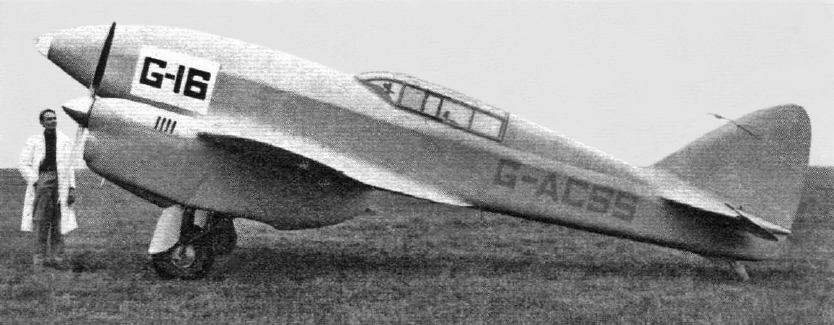

In June 1937, he learned that the DH.88 Comet (G-ACSS), that won the 1934

In June 1937, he learned that the DH.88 Comet (G-ACSS), that won the 1934 MacRobertson Race

The MacRobertson Trophy Air Race (also known as the London to Melbourne Air Race) took place in October 1934 in aviation, 1934 as part of the 1934 Centenary of Melbourne, Melbourne Centenary celebrations. The race was devised by the Lord Mayor o ...

, was for sale by a scrap dealer, after it had been damaged in Air Ministry testing. He persuaded architect Fred Tasker to purchase the Comet, and then arranged for it to be repaired with upgraded engines and propellers, by Jack Cross of Essex Aero at Gravesend Aerodrome. He entered the Comet for the planned 1937 New York to Paris air race, but the US Department of Commerce refused all necessary permissions for the race.

The French government reorganised the race to run from Istres Airfield near Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Franc ...

, via Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, to Paris. The only inscriptions on the Comet were the registration and race number "G-16", but it was also nicknamed "The Orphan" to reflect the lack of sponsors. On 20 August 1937, accompanied by Flt Lt George Nelson as co-pilot of the Comet, Clouston took off from Istres as one of 13 entrants, of which all the others were more powerful, and all heavily sponsored by European governments. He arrived at Le Bourget

Le Bourget () is a Communes of France, commune in the northeastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the Kilometre zero#France, center of Paris.

The commune features Paris - Le Bourget Airport, Le Bourget Airport, which in turn hos ...

in fourth position, a few minutes behind the Savoia-Marchetti S.73 of Bruno Mussolini

Bruno Mussolini (22 April 1918 – 7 August 1941) was the son of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and Mussolini's wife Rachele, the nephew of Arnaldo Mussolini, and also the grandson of Alessandro Mussolini and Rosa Mussolini. He was an experie ...

.

In 1937, Clouston broke the record for a return flight from England to Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

. Betty Kirby-Green

Betty Kirby-Green (19061992) was an adventurer and pilot with multiple aviation records.

Biography

Betty Kirby-Green was born in Thurlestone, Devon in 1906. Kirby-Green was adventurous. She ran away from school and joined a dance troupe on the ...

was relatively new to flying, with an appetite for adventure, and agreed to help raise money for an attempt on the Cape record set by Amy Johnson in 1936. Burberry

Burberry is a British luxury fashion house established in 1856 by Thomas Burberry headquartered in London, England. It currently designs and distributes ready to wear, including trench coats (for which it is most famous), leather accessories, ...

sponsored the flight and provided Burberry flying clothing, and their DH.88 Comet, G-ACSS was consequently named renamed "The Burberry". On 14 November 1937, Clouston and Kirby-Green took off from Croydon Aerodrome

Croydon Airport (former ICAO code: EGCR) was the UK's only international airport during the interwar period. Located in Croydon, South London, England, it opened in 1920, built in a Neoclassical style, and was developed as Britain's main ai ...

, and reached Cape Town on 16 November in a record 45 hours and two minutes. Their return journey of 57 hours and 23 minutes was also record-breaking. The DH.88 Comet has since been restored, and is now held at the Shuttleworth Collection.

On 20 November, they arrived back at Croydon in dense fog, having broken several records and covered about 14,690 miles in less than six days. As a result, Clouston was awarded the Britannia Trophy

The Britannia Trophy is a British award presented by the Royal Aero Club for aviators accomplishing the most meritorious performance in aviation during the previous year.

In 1911 Horatio Barber, who was a founder member of the Royal Aero Club, w ...

and the Segrave Trophy

The Segrave Trophy is awarded to the British national who demonstrates "Outstanding Skill, Courage and Initiative on Land, Water and in the Air". The trophy is named in honour of Sir Henry Segrave, the first person to hold both the land and wat ...

, and Betty was awarded the Segrave Medal.

On 4 December 1937, Clouston married Elsie Turner, the daughter of engineer Samuel Turner of Farnborough; they subsequently had two daughters.

In December 1937, Daily Express air correspondent Victor Ricketts proposed to Clouston that they should attempt to break the England to Australia flight record. Ricketts arranged for sponsorship from the Australian Consolidated Press

Are Media is an Australian media company that was formed after the 2020 purchase of the assets of Bauer Media Australia, which had in turn acquired the assets of Pacific Magazines, AP Magazines and Australian Consolidated Press during the 201 ...

, and once again the DH.88 Comet G-ACSS was hired. It was overhauled and equipped with a small typewriter to compile press reports in flight for dispatch at refuelling stops. It was named "Australian Anniversary", representing the 150th anniversary of Australia.

On 6 February 1938, Clouston and Ricketts took off from Gravesend Aerodrome. The first scheduled stop was to be Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

in Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, but bad storms forced Clouston to land at a flooded airfield at Adana

Adana (; ; ) is a major city in southern Turkey. It is situated on the Seyhan River, inland from the Mediterranean Sea. The administrative seat of Adana Province, Adana province, it has a population of 2.26 million.

Adana lies in the heart ...

in Turkey. His permits were dismissed by Turkish officials, but next day he refuelled with unofficial help, and took off from a roadway, although damaging the undercarriage. He flew to an unmarked airfield on Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, having abandoned the record attempt. Engineer Jack Cross, plus the financier and some equipment, was flown to Cyprus by Alex Henshaw

Alexander Adolphus Dumphries Henshaw, (7 November 1912 – 24 February 2007) was a British air racer in the 1930s and a test pilot for Vickers Armstrong during the Second World War.

Early life

Henshaw was born in Peterborough, the eldest son of ...

in a Vega Gull

The Vega gull, East Siberian gull, or East Siberian herring gull (''Larus vegae'') is a large gull of the herring gull/lesser black-backed gull complex which breeds in Northeast Asia. Its classification is still controversial and uncertain. It i ...

borrowed from Charles Gardner. After repairs to the Comet, Clouston flew it back to Gravesend, accompanied by Jack Cross.

On 15 March 1938, Clouston once again departed from Gravesend with Victor Ricketts in DH.88 Comet G-ACSS. He flew via Cairo, Basra, Allahabad, Penang

Penang ( ms, Pulau Pinang, is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia, by the Malacca Strait. It has two parts: Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai on the Malay ...

and Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

to Darwin, but without beating the 1934 record set by C. W. A. Scott

Flight Lieutenant Charles William Anderson Scott, AFC (13 February 1903 – 15 April 1946Dunnell ''Aeroplane'', November 2019, p. 46.) was an English aviator. He won the MacRobertson Air Race, a race from London to Melbourne, in 1934, in a tim ...

and Tom Campbell Black

Tom Campbell Black (December 1899 – 19 September 1936) was an English aviator.

He was the son of Alice Jean McCullough and Hugh Milner Black. He became a world-famous aviator when he and C. W. A. Scott won the London to Melbourne Centenary ...

in the same aircraft. He flew on to Sydney via Charleville, without being aware of the London to Sydney record, until massive crowds welcomed him there as a record-breaker. The next day, 20 March 1938, he flew across the Tasman Sea

The Tasman Sea (Māori: ''Te Tai-o-Rēhua'', ) is a marginal sea of the South Pacific Ocean, situated between Australia and New Zealand. It measures about across and about from north to south. The sea was named after the Dutch explorer Abe ...

to Blenheim Municipal Aerodrome (Omaka) in New Zealand, setting more records. He then flew back to Australia, and continued on a return flight to Croydon, arriving in fog on 26 March 1938. He had established eleven records at the end of a round-trip of about 26,000 miles.

On 2 July 1938, he flew BA Eagle 2 (G-AFIC) in the King's Cup Race

The King's Cup air race is a British handicapped cross-country event, which has taken place annually since 1922. It is run by the Royal Aero Club Records Racing and Rally Association.

The King's Cup is one of the most prestigious prizes of the ...

at Hatfield Aerodrome

Hatfield Aerodrome was a private airfield and aircraft factory located in the English town of Hatfield in Hertfordshire from 1930 until its closure and redevelopment in the 1990s.

Early history

Geoffrey de Havilland, pioneering aircraft desig ...

, but was placed outside the top three.

Second World War

On the outbreak of the Second World War, Clouston was recalled to the RAF in the rank of flight lieutenant and was posted back to Farnborough to serve in the Experimental Section of the RAE as a test pilot with the rank of flight lieutenant. Although the unit operated some high speed fighters, it was forbidden to arm them, but Clouston reportedly on one occasion, shortly after the death of his brother, also a pilot in the RAF, overDunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

incursions led to orders to arm the fighters, and their pilots were authorised to fly patrols over the airfield in the event of detection of approaching German aircraft. Clouston, having resumed flying duties, was on a such a patrol in a Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

fighter when on his own initiative, he pursued some German aircraft. He subsequently claimed to have destroyed a Heinkel 111

The Heinkel He 111 is a German airliner and bomber designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter at Heinkel Flugzeugwerke in 1934. Through development, it was described as a " wolf in sheep's clothing". Due to restrictions placed on Germany after t ...

medium bomber and a Messerschmitt Bf 110

The Messerschmitt Bf 110, often known unofficially as the Me 110,Because it was built before ''Bayerische Flugzeugwerke'' became Messerschmitt AG in July 1938, the Bf 110 was never officially given the designation Me 110. is a twin-engine (Des ...

heavy fighter. He was again grounded when he returned.

He carried out many flight tests using both tethered and untethered flares launched from a Handley Page Hampden

The Handley Page HP.52 Hampden is a British twin-engine medium bomber that was operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was part of the trio of large twin-engine bombers procured for the RAF, joining the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley and Vickers ...

flying behind a Whitley bomber, in experiments to illuminate target aircraft at night. He also flew tests with a Douglas Havoc

The Douglas A-20 Havoc (company designation DB-7) is an American medium bomber, attack aircraft, night intruder, night fighter, and reconnaissance aircraft of World War II.

Designed to meet an Army Air Corps requirement for a bomber, it was or ...

, dispensing flash flares. In April 1941, he was attached to No. 219 Squadron, operating Bristol Beaufighter

The Bristol Type 156 Beaufighter (often called the Beau) is a British multi-role aircraft developed during the Second World War by the Bristol Aeroplane Company. It was originally conceived as a heavy fighter variant of the Bristol Beaufort ...

s from RAF Redhill

Redhill Aerodrome is an operational general aviation aerodrome located south-east of Redhill, Surrey, England, in green belt land.

Redhill Aerodrome has a CAA Ordinary Licence (Number P421) that allows flights for the public transport of p ...

, to experience night fighter tactics. His reports to the Air Ministry led to improvements to cannons on Beaufighters, and better training for radar operators.

On 12 May 1941, he was posted as CO of No. 1422 Flight RAF of the RAE based at RAF Heston

Heston Aerodrome was an airfield located to the west of London, England, operational between 1929 and 1947. It was situated on the border of the Heston and Cranford areas of Hounslow, Middlesex. In September 1938, the British Prime Minister, Ne ...

. There he carried out testing of the Turbinlite

The Helmore/ GEC Turbinlite was a 2,700 million candela (2.7 Gcd) searchlight fitted in the nose of a number of British Douglas Havoc night fighters during the early part of the Second World War and around the time of The Blitz. The ...

concept of an aerial searchlight mounted on a Havoc night fighter, in collaboration with Group Captain William Helmore

Air Commodore William Helmore CBE, PhD, MS., FCS, F.R.Ae.S. (1 March 1894 – 18 December 1964) was an engineer who had a varied and distinguished career in scientific research with the Air Ministry and the Ministry of Aircraft Production duri ...

and with aeronautical engineer L.E. Baynes, nicknamed "The Baron", for whom he had great admiration. The next experiments involved dropping coils of wire suspended from parachutes, intended to interfere with the operation of intruding aircraft. Clouston conducted another trial instigated by Helmore, involving radio control of a full-size motor launch boat from a high-flying aircraft, using a Douglas DB-7 Havoc. He was also involved in testing the Leigh Light, an aerial searchlight designed to illuminate submarines and surface vessels, and trialled on a Vickers Wellington

The Vickers Wellington was a British twin-engined, long-range medium bomber. It was designed during the mid-1930s at Brooklands in Weybridge, Surrey. Led by Vickers-Armstrongs' chief designer Rex Pierson; a key feature of the aircraft is its g ...

. He was awarded a Bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar (u ...

to his AFC in January 1942.

In March 1943, Clouston was promoted to wing commander, and posted to command No. 224 Squadron firstly at RAF Beaulieu

Royal Air Force Beaulieu or more simply RAF Beaulieu is a former Royal Air Force station in the New Forest, Hampshire, England. It was also known as Beaulieu airfield, Beaulieu aerodrome and USAAF Station AAF 408. It is located next to the villa ...

, then in April 1943 at RAF St Eval

Royal Air Force St. Eval or RAF St. Eval was a Royal Air Force station for the RAF Coastal Command, southwest of Padstow in Cornwall, England, UK. St Eval's primary role was to provide anti-submarine and anti-shipping patrols off the south wes ...

. The squadron was mainly involved in anti-submarine operations in the Bay of Biscay, operating B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models des ...

s with airborne radar and depth charges, later supplemented with Leigh lights. The Liberators were often attacked by formations of Bf 110s and Junkers Ju 88

The Junkers Ju 88 is a German World War II ''Luftwaffe'' twin-engined multirole combat aircraft. Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works (JFM) designed the plane in the mid-1930s as a so-called ''Schnellbomber'' ("fast bomber") that would be too fast ...

s. In October 1943 Clouston was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, followed in April 1944 by the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typ ...

.

In February 1944, he was promoted to group captain, and posted as commanding officer of RAF Langham

Royal Air Force Langham or more simply RAF Langham is a former Royal Air Force station, located at Langham, northwest of Norwich in the English county of Norfolk. It operated between 1940 and 1961. The airfield was the most northerly of the ...

, that was still under construction. Operations there started with No. 455 Squadron and No. 489 Squadron, both flying Beaufighters on anti-shipping missions in the North Sea area. In October 1944, the Beaufighter squadrons were replaced by No. 521 Squadron with Lockheed Hudson

The Lockheed Hudson is a light bomber and coastal reconnaissance aircraft built by the American Lockheed Aircraft Corporation. It was initially put into service by the Royal Air Force shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War and prim ...

s and No. 524 Squadron with Wellingtons.

Postwar

In May 1945, Clouston was posted as CO of German airstrip B151 that was being developed into the headquarters of BAFO (British Air Forces of Occupation), and namedRAF Bückeburg

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

. In April 1946, he was appointed to a permanent commission with his existing rank of squadron leader. However, he was then offered the job of Director General of Civil Aviation of New Zealand. Instead of being released by the RAF, he was promoted to group captain

Group captain is a senior commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force, where it originated, as well as the air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. It is sometimes used as the English translation of an equivalent rank i ...

, and given a two-year posting on exchange to the Royal New Zealand Air Force

The Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) ( mi, Te Tauaarangi o Aotearoa, "The Warriors of the Sky of New Zealand"; previously ', "War Party of the Blue") is the aerial service branch of the New Zealand Defence Force. It was formed from New Zeala ...

as commanding officer of RNZAF Base Ohakea

RNZAF Base Ohakea is an operational base of the Royal New Zealand Air Force. Opened in 1939, it is located near Bulls, New Zealand, Bulls, 25 km north-west of Palmerston North in the Manawatu District, Manawatu. It is also a diversion landin ...

.

Returning to service with the RAF after concluding his appointment at Ohakea, he was commandant of the Empire Test Pilot School at Farnborough in 1949. In October 1953, he was posted as SASO (Senior Air Staff Officer) at No. 19 Group, RAF Coastal Command. In July 1954, he was promoted to acting air commodore, then posted as Air Officer Commanding Singapore. In 1957, he was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregive ...

, and was given his final posting as commandant of Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment

The Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) was a research facility for British military aviation from 1918 to 1992. Established at Martlesham Heath, Suffolk, the unit moved in 1939 to Boscombe Down, Wiltshire, where its work ...

at Boscombe Down.

In April 1960, Clouston retired from the RAF. He settled in Cornwall, where he died at St Merryn

St Merryn ( kw, S. Meryn) is a civil parishes in England, civil parish and village in north Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. It is about south of the fishing port of Padstow and northeast of the coastal resort of Newquay.

The village has a ...

on 1 January 1984. His autobiography, ''The Dangerous Skies'', had been published several years previously.

Notes

Bibliography

* *Henshaw, Alex. "Personal Album", ''Aeroplane Monthly'', November 1984 *Lewis,Peter. 1970. ''British Racing and Record-Breaking Aircraft''. Putnam. *Middleton, Don. "Test Pilot Profile No.4 – A.E.Clouston", ''Aeroplane Monthly'', October 1982 * *Orange, Vincent. 2004.Clouston, Arthur Edmond (1908–1984)

'. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. * * *

Further reading

*Clouston, A.E. 1954. ''The Dangerous Skies''. Cassell ASIN B0000CIX25 {{DEFAULTSORT:Clouston, A. E. 1908 births 1984 deaths Britannia Trophy winners British test pilots Companions of the Order of the Bath Recipients of the Air Force Cross (United Kingdom) Royal Air Force officers Royal Air Force personnel of World War II Segrave Trophy recipients People from Motueka New Zealand emigrants to the United Kingdom Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United Kingdom) British aviation record holders