Οâlie Metchnikoff on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

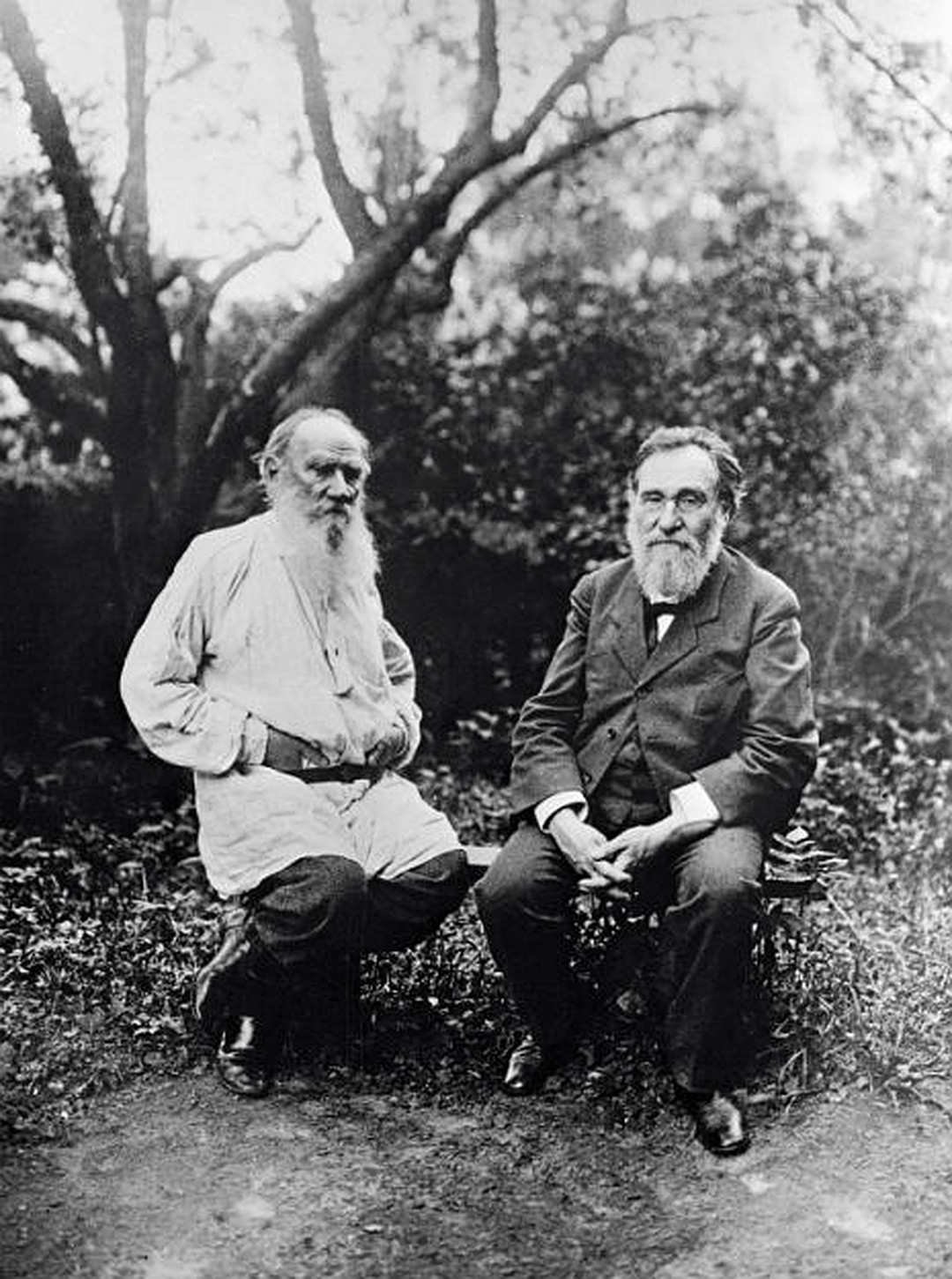

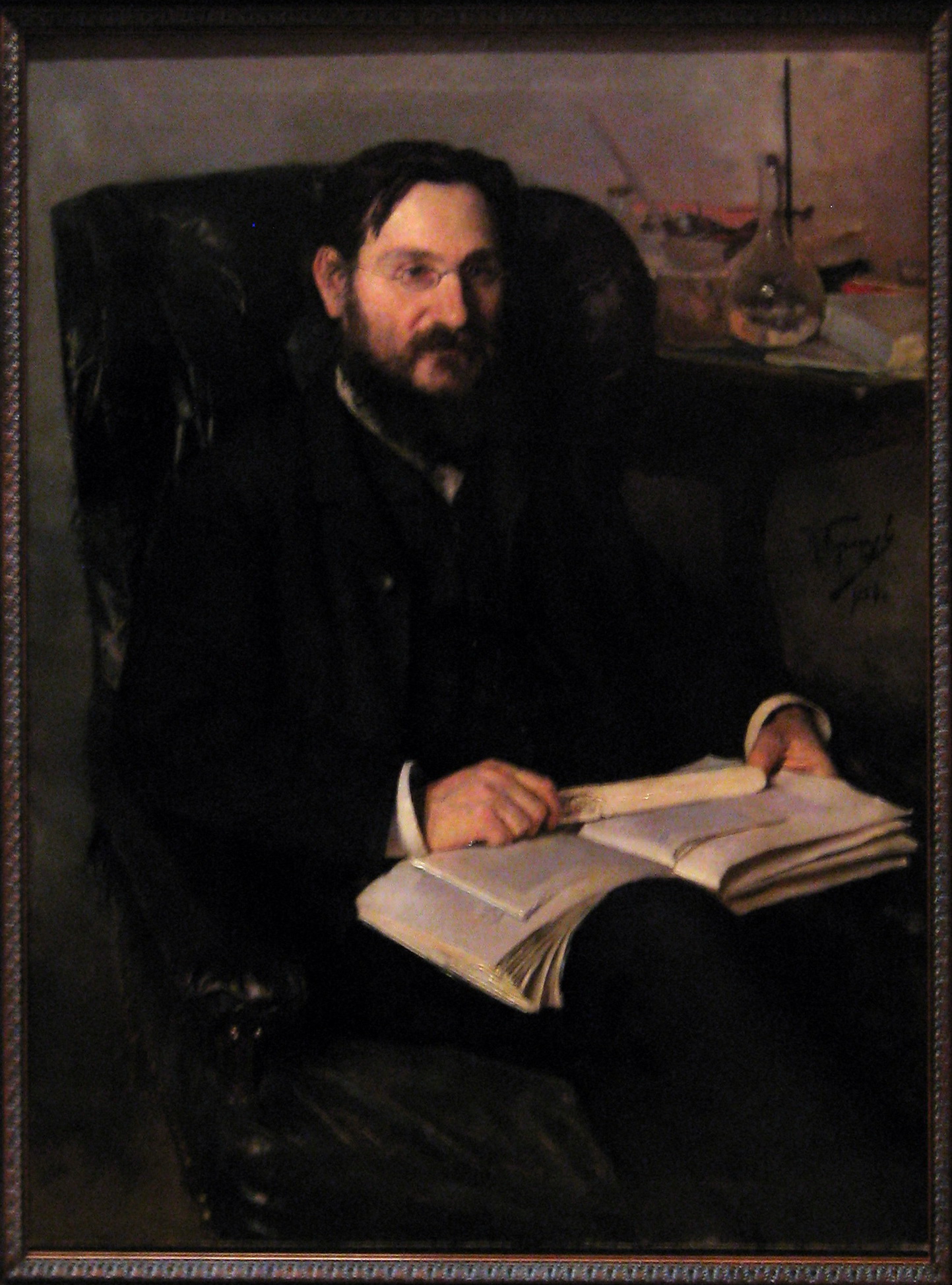

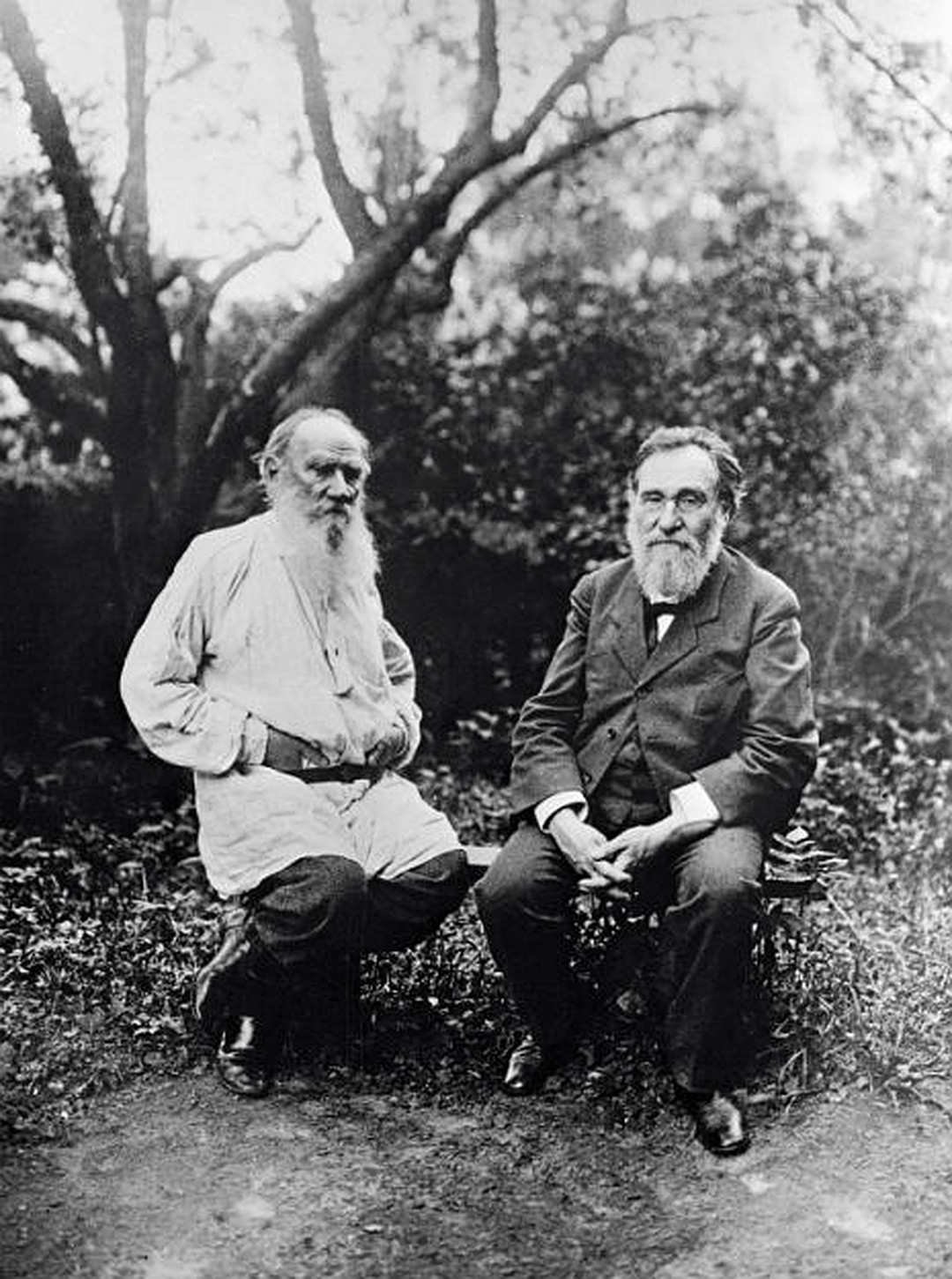

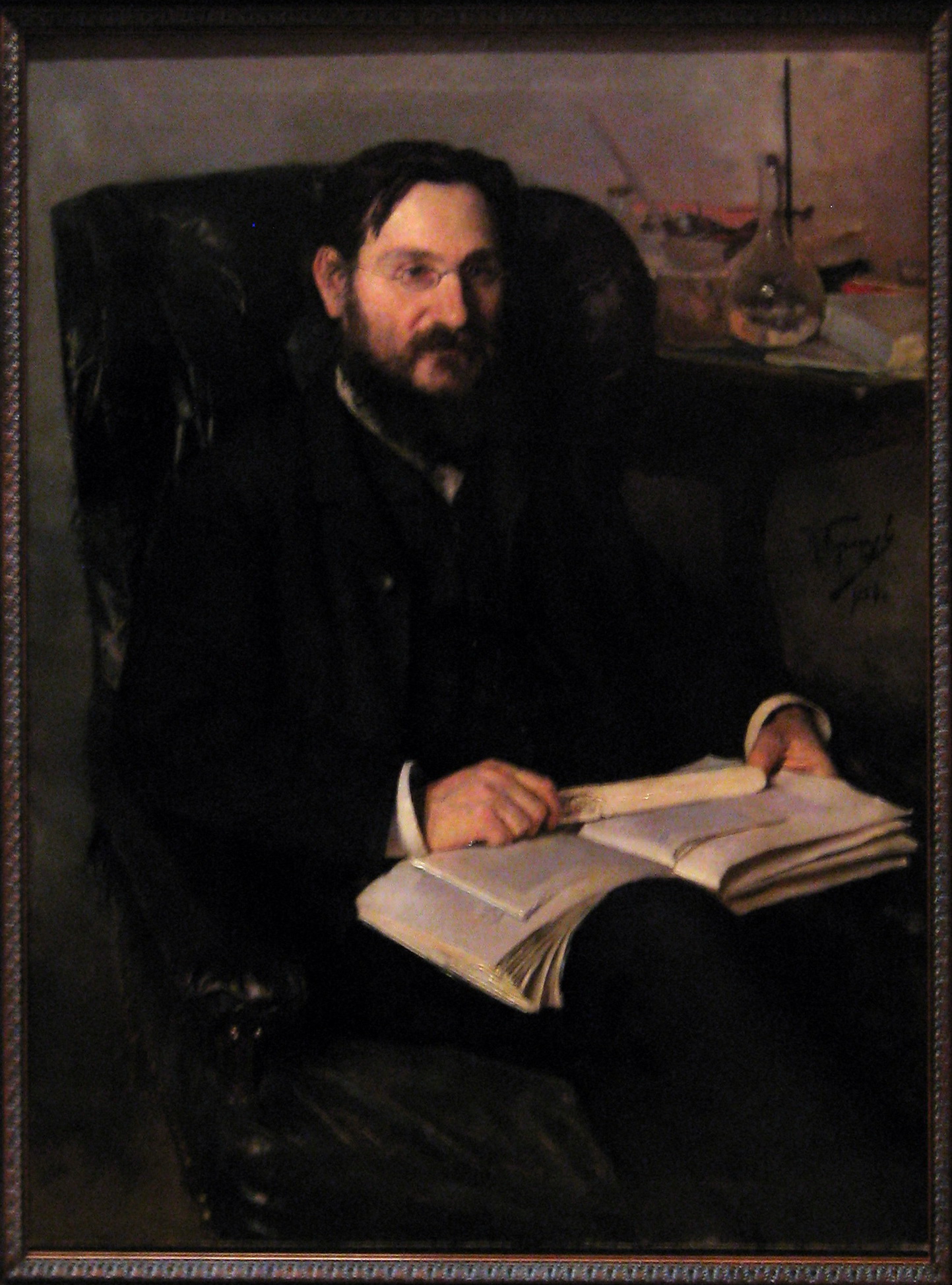

Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov (russian: –‰–Μ―¨―è –‰–Μ―¨–Η―΅ –€–Β―΅–Ϋ–Η–Κ–Ψ–≤; βÄ™ 15 July 1916), also spelled Οâlie Metchnikoff, was a Russian

Metchnikoff was born in the village of ,

Metchnikoff was born in the village of ,

here

at archive.org The Nevakhovich family was Jewish.The family name Mechnikov is a translation from

Metchnikoff married his first wife, Ludmila Feodorovitch, in 1869. She died from

Metchnikoff married his first wife, Ludmila Feodorovitch, in 1869. She died from

''LeΟßons sur la pathologie comparΟ©e de lβÄôinflammation''

(1892; ''Lectures on the Comparative Pathology of Inflammation'')

''LβÄôImmunitΟ© dans les maladies infectieuses''

(1901; ''Immunity in Infectious Diseases'')

''Οâtudes sur la nature humaine''

(1903; ''The Nature of Man'')

''Immunity in Infective Diseases''

(1905)

''The New Hygiene: Three Lectures on the Prevention of Infectious Diseases''

(1906)

''The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies''

(1907) * * *

The Romantic Rationalist: A Study Of Elie Metchnikoff

Works of Elie Metchnikoff, a Pasteur Institute bibliography

(In Russian)

Lactobacillus bulgaricus on the web

* ''Tsalyk St.''br>Immunity defender

*

Immunity in Infective Diseases

' (1905) by Οâlie Metchnikoff, translated by Francis B. Binny, on the Internet Archive *

The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies

' (1908) by Οâlie Metchnikoff, translation edited by P. Chalmers Mitchell, on the Internet Archive

Luba Vikhanski's page for Metchnikoff's documentary

Mechnikov Ilya, 1845 - 1916, Year won 1908, A pioneer researcher of immunity

on th

ANU - Museum of the Jewish People

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Metchnikoff, Elie 1845 births 1916 deaths Academy of Fine Arts, Munich alumni Foreign Members of the Royal Society Emigrants from the Russian Empire to France Russian gerontologists Honorary members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences National University of Kharkiv alumni Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine Pasteur Institute People from Kharkiv Oblast Recipients of the Copley Medal Russian atheists Russian immunologists Russian people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent Russian Nobel laureates Russian people of Romanian descent Russian zoologists University of GΟΕttingen alumni

zoologist

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the Animal, animal kingdom, including the anatomy, structure, embryology, evolution, Biological clas ...

best known for his pioneering research in immunology

Immunology is a branch of medicineImmunology for Medical Students, Roderick Nairn, Matthew Helbert, Mosby, 2007 and biology that covers the medical study of immune systems in humans, animals, plants and sapient species. In such we can see there ...

. Belkin, a Russian science historian, explains why Metchnikoff himself, in his Nobel autobiography βÄ™ and subsequently, many other sources βÄ™ mistakenly cited his date of birth as 16 May instead of 15 May. Metchnikoff made the mistake of adding 13 days to 3 May, his Old Style birthday, as was the convention in the 20th century. But since he had been born in the 19th century, only 12 days should have been added. He and Paul Ehrlich

Paul Ehrlich (; 14 March 1854 βÄ™ 20 August 1915) was a Nobel Prize-winning German physician and scientist who worked in the fields of hematology, immunology, and antimicrobial chemotherapy. Among his foremost achievements were finding a cure ...

were jointly awarded the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accord ...

"in recognition of their work on immunity".

Mechnikov was born in modern-day Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, –Θ–Κ―Ä–Α―½–Ϋ–Α, UkraΟ·na, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

to a Romanian noble father and a Ukrainian-Jewish

The history of the Jews in Ukraine dates back over a thousand years; Jewish communities have existed in the territory of Ukraine from the time of the Kievan Rus' (late 9th to mid-13th century). Some of the most important Jewish religious and ...

mother, lived and worked for many years on the territory of what was then the Russian Empire, and later on continued his career in France. Given this complex heritage, four different nations and peoples justifiably lay claim to Metchnikoff. Despite having a mother of Jewish origin, he was baptized Russian Orthodox

Russian Orthodoxy (russian: –†―É―¹―¹–Κ–Ψ–Β –Ω―Ä–Α–≤–Ψ―¹–Μ–Α–≤–Η–Β) is the body of several churches within the larger communion of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, whose liturgy is or was traditionally conducted in Church Slavonic language. Most ...

, although he later became an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

.

Honoured as the "father of innate immunity

The innate, or nonspecific, immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies (the other being the adaptive immune system) in vertebrates. The innate immune system is an older evolutionary defense strategy, relatively speaking, and is the ...

", Metchnikoff was the first to discover a process of immunity called phagocytosis

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (βâΞ 0.5 ΈΦm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs phagocytosis is ...

and the cell responsible for it, called phagocyte

Phagocytes are cells that protect the body by ingesting harmful foreign particles, bacteria, and dead or dying cells. Their name comes from the Greek ', "to eat" or "devour", and "-cyte", the suffix in biology denoting "cell", from the Greek ...

, specifically macrophage

Macrophages (abbreviated as M œÜ, MΈΠ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''ΈΦΈ±ΈΚœ¹œ¨œ²'' (') = large, ''œÜΈ±Έ≥ΈΒαΩ•ΈΫ'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer cel ...

, in 1882. This discovery turned out to be the major defence mechanism in innate immunity, as well as the foundation of the concept of cell-mediated immunity

Cell-mediated immunity or cellular immunity is an immune response that does not involve antibodies. Rather, cell-mediated immunity is the activation of phagocytes, antigen-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, and the release of various cytokines in ...

, while Ehrlich established the concept of humoral immunity to complete the principles of immune system. Their works are regarded as the foundation of the science of immunology

Immunology is a branch of medicineImmunology for Medical Students, Roderick Nairn, Matthew Helbert, Mosby, 2007 and biology that covers the medical study of immune systems in humans, animals, plants and sapient species. In such we can see there ...

.

Metchnikoff developed one of the earliest concepts in ageing

Ageing ( BE) or aging ( AE) is the process of becoming older. The term refers mainly to humans, many other animals, and fungi, whereas for example, bacteria, perennial plants and some simple animals are potentially biologically immortal. In ...

, and advocated the use of lactic acid bacteria (''Lactobacillus

''Lactobacillus'' is a genus of Gram-positive, aerotolerant anaerobes or microaerophilic, rod-shaped, non-spore-forming bacteria. Until 2020, the genus ''Lactobacillus'' comprised over 260 phylogenetically, ecologically, and metabolically diver ...

'') for healthy and long life. This became the concept of probiotics

Probiotics are live microorganisms promoted with claims that they provide health benefits when consumed, generally by improving or restoring the gut microbiota. Probiotics are considered generally safe to consume, but may cause bacteria- host i ...

in medicine. Mechnikov is also credited with coining the term gerontology in 1903, for the emerging study of aging and longevity. In this regard, Ilya Mechnikov is called the "father of gerontology" (although, as often happens in science, the situation is ambiguous, and the same title is sometimes applied to some other people who contributed to aging research later).

Supporters of life extension celebrate 15 May as Metchnikoff Day, and used it as a memorable date for organizing activities.

Early life, family and education

Metchnikoff was born in the village of ,

Metchnikoff was born in the village of , Kharkov Governorate

The Kharkov Governorate ( pre-reform Russian: , tr. ''KhΟΓrkovskaya gubΟ©rniya'', IPA: àxar ≤k…ôfsk…ôj…ô …Γ äΥàb ≤ern ≤…Σj…ô ) was a governorate of the Russian Empire founded in 1835. It embraced the historical region of Sloboda Ukraine. Fro ...

, in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, now located in Kupiansk Raion

Kupiansk Raion is a district in Ukraine in the state of Kharkiv Oblast. The administrative center of the raion is the city of Kupiansk. Population:

On 18 July 2020, as part of the administrative reform of Ukraine, the number of raions of Kharkiv ...

, Kharkiv Oblast

Kharkiv Oblast ( uk, –Ξ–Α―Ä–Κ―•–≤―¹―¨–Κ–ΑΧ¹ –ΨΧ¹–±–Μ–Α―¹―²―¨, translit=Kharkivska oblast), also referred to as Kharkivshchyna ( uk, –Ξ–ΑΧ¹―Ä–Κ―•–≤―â–Η–Ϋ–Α), is an oblast (province) of eastern Ukraine. The oblast borders Russia to the north, Luhans ...

in Ukraine. He was the youngest of five children of Ilya Ivanovich Mechnikov, an officer of the Imperial Guard

An imperial guard or palace guard is a special group of troops (or a member thereof) of an empire, typically closely associated directly with the Emperor or Empress. Usually these troops embody a more elite status than other imperial forces, i ...

. His mother, Emilia Lvovna (Nevakhovich), the daughter of the writer Leo Nevakhovich, largely influenced him on his education, especially in science. and alshere

at archive.org The Nevakhovich family was Jewish.The family name Mechnikov is a translation from

Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

*** Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

** Romanian cuisine, tradition ...

, since his father was a descendant of the Chancellor Yuri Stefanovich, the grandson of Nicolae Milescu

Nikolai Spathari (russian: –ù–Η–Κ–Ψ–Μ–Α–Ι –™–Α–≤―Ä–Η–Μ–Ψ–≤–Η―΅ –Γ–Ω–Α―³–Α―Ä–Η–Ι, Nikolai Gavrilovich Spathari; 1636βÄ™1708), also known as Nicolae Milescu and Nicolae Milescu SpΡÉtaru (, first name also ''Neculai'', signing in Latin as Nicolaus ...

SpΡÉtaru. The word "mech" is a Russian translation of the Romanian "spadΡÉ" (sword), which originated with SpΡÉtar The ''spatharii'' or ''spatharioi'' (singular: la, spatharius; el, œÉœÄΈ±ΈΗΈ§œ¹ΈΙΈΩœ², literally "spatha-bearer") were a class of Late Roman imperial bodyguards in the court in Constantinople in the 5thβÄ™6th centuries, later becoming a purely ho ...

(Sword-bearer). His elder brother Lev

Lev may refer to:

Common uses

*Bulgarian lev, the currency of Bulgaria

*an abbreviation for Leviticus, the third book of the Hebrew Bible and the Torah

People and fictional characters

*Lev (given name)

*Lev (surname)

Places

*Lev, Azerbaijan, a ...

became a prominent geographer and sociologist.

In 1856, Metchnikoff entered the Kharkov LycΟ©e, where he developed his interest in biology. Convinced by his mother to study natural sciences

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

instead of medicine, in 1862 he tried to study biology at the University of WΟΦrzburg

The Julius Maximilian University of WΟΦrzburg (also referred to as the University of WΟΦrzburg, in German ''Julius-Maximilians-UniversitΟΛt WΟΦrzburg'') is a public research university in WΟΦrzburg, Germany. The University of WΟΦrzburg is one of ...

, but the German academic session would not start by the end of the year. Metchnikoff thus enrolled at Kharkov Imperial University for natural sciences

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

, completing his four-year degree in two years.

In 1864, he traveled to Germany to study marine fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. Zoo ...

on the small North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

island of Heligoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possessions ...

. He was advised by the botanist Ferdinand Cohn to work with Rudolf Leuckart

Karl Georg Friedrich Rudolf Leuckart (7 October 1822 βÄ™ 22 February 1898) was a German zoologist born in Helmstedt. He was a nephew to naturalist Friedrich Sigismund Leuckart (1794βÄ™1843).

Academic career

He earned his degree from the Uni ...

at the University of Giessen

University of Giessen, official name Justus Liebig University Giessen (german: Justus-Liebig-UniversitΟΛt GieΟüen), is a large public research university in Giessen, Hesse, Germany. It is named after its most famous faculty member, Justus von ...

. It was in Leuckart's laboratory that he made his first scientific discovery of alternation of generations

Alternation of generations (also known as metagenesis or heterogenesis) is the predominant type of Biological life cycle, life cycle in plants and algae. It consists of a Multicellular organism, multicellular haploid sexual phase, the gametophy ...

(sexual and asexual) in nematodes

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, ΈùΈΖΈΦΈ±œ³œéΈ¥ΈΖ; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant-parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhabiting a broa ...

and then at the University of Munich

The Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (simply University of Munich or LMU; german: Ludwig-Maximilians-UniversitΟΛt MΟΦnchen) is a public research university in Munich, Germany. It is Germany's List of universities in Germany, sixth-oldest u ...

. In 1865, while at Giessen, he discovered intracellular digestion in flatworm

The flatworms, flat worms, Platyhelminthes, or platyhelminths (from the Greek œÄΈΜΈ±œ³œç, ''platy'', meaning "flat" and αΦïΈΜΈΦΈΙΈΫœ² (root: αΦëΈΜΈΦΈΙΈΫΈΗ-), ''helminth-'', meaning "worm") are a phylum of relatively simple bilaterian, unsegment ...

, and this study influenced his later works. Moving to Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, ΈùΈΒΈ§œÄΈΩΈΜΈΙœ², NeΟΓpolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

the next year he worked on a doctoral thesis on the embryonic development of the cuttle-fish '' Sepiola'' and the crustacean ''Nebalia

''Nebalia'' is a large genus of small crustaceans containing more than half of the species in the order Leptostraca, and was first described by William Elford Leach in 1814. The genus contains over thirty species:

*'' Nebalia abyssicola'' Ledoy ...

''. A cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

epidemic in the autumn of 1865 made him move to the University of GΟΕttingen

The University of GΟΕttingen, officially the Georg August University of GΟΕttingen, (german: Georg-August-UniversitΟΛt GΟΕttingen, known informally as Georgia Augusta) is a public research university in the city of GΟΕttingen, Germany. Founded ...

, where he worked briefly with W. M. Keferstein and Jakob Henle

Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle (; 9 July 1809 βÄ™ 13 May 1885) was a German physician, pathologist, and anatomist. He is credited with the discovery of the loop of Henle in the kidney. His essay, "On Miasma and Contagia," was an early argument for ...

.

In 1867, he returned to Russia to receive his doctorate with Alexander Kovalevsky

Alexander Onufrievich Kovalevsky (russian: –ê–Μ–Β–Κ―¹–ΑΧ¹–Ϋ–¥―Ä –û–Ϋ―ÉΧ¹―³―Ä–Η–Β–≤–Η―΅ –ö–Ψ–≤–Α–Μ–ΒΧ¹–≤―¹–Κ–Η–Ι, 7 November 1840 in VΡ¹rkava parish, Vorkovo, Dvinsky Uyezd, Vitebsk Governorate, Russian Empire βÄ™ 1901, St. Petersburg, Russian Empi ...

from the University of Saint Petersburg

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, th ...

. Together they won the Karl Ernst von Baer prize for their theses on the development of germ layers in invertebrate embryos.

Career and achievements

Metchnikoff was appointeddocent

The title of docent is conferred by some European universities to denote a specific academic appointment within a set structure of academic ranks at or below the full professor rank, similar to a British readership, a French " ''maΟ°tre de conf ...

at the newly established Imperial Novorossiya University (now Odessa University

Odesa I. I. Mechnykov National University ( uk, –û–¥–Β―¹―¨–Κ–Η–Ι –Ϋ–Α―Ü―•–Ψ–Ϋ–Α–Μ―¨–Ϋ–Η–Ι ―É–Ϋ―•–≤–Β―Ä―¹–Η―²–Β―² I–Φ–Β–Ϋ―• –Ü. –Ü. –€–Β―΅–Ϋ–Η–Κ–Ψ–≤–Α, translit=Odeskyi natsionalnyi universytet imeni I. I. Mechnykova), located in Odesa, Ukraine, i ...

). Only twenty-two years of age, he was younger than his students. After being involved in a conflict with a senior colleague over attending scientific meetings, he transferred to the University of Saint Petersburg in 1868, where he experienced a worse professional environment. In 1870 he returned to Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

to take up the appointment of Titular Professor of Zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the Animal, animal kingdom, including the anatomy, structure, embryology, evolution, Biological clas ...

and Comparative Anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

.

In 1882 he resigned from Odessa University due to political turmoils after the assassination of Alexander II

On 13 March Old Style], 1881, Alexander II of Russia, Alexander II, the Emperor of Russia, was assassinated in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire, Russia while returning to the Winter Palace from Mikhailovsky ManΟ®ge in a closed carriage.

The ass ...

. He went to Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

to set up his private laboratory in Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in ...

. He returned to Odessa as director of an institute set up to carry out Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 βÄ™ 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named afte ...

's vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifie ...

against rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. Early symptoms can include fever and tingling at the site of exposure. These symptoms are followed by one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, vi ...

; due to some difficulties, he left in 1888 and went to Paris to seek Pasteur's advice. Pasteur gave him an appointment at the Pasteur Institute

The Pasteur Institute (french: Institut Pasteur) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines f ...

, where he remained for the rest of his life.

Metchnikoff became interested in the study of microbes

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, αΫÄœ¹Έ≥Έ±ΈΫΈΙœÉΈΦœ¨œ², ''organismΟ≥s'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

, and especially the immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinte ...

. At Messina he discovered phagocytosis

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (βâΞ 0.5 ΈΦm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs phagocytosis is ...

after experimenting on the larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

The ...

e of starfish

Starfish or sea stars are star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to as brittle stars or basket stars. Starfish ...

. In 1882 he first demonstrated the process when he inserted small citrus

''Citrus'' is a genus of flowering plant, flowering trees and shrubs in the rue family, Rutaceae. Plants in the genus produce citrus fruits, including important crops such as Orange (fruit), oranges, Lemon, lemons, grapefruits, pomelos, and lim ...

thorns into starfish larvae, then found unusual cells surrounding the thorns. He realized that in animals which have blood, the white blood cells gather at the site of inflammation, and he hypothesised that this could be the process by which bacteria were attacked and killed by the white blood cells. He discussed his hypothesis with Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Claus

Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Claus (2 January 1835 βÄ™ 18 January 1899) was a German zoologist and anatomist. He was an opponent of the ideas of Ernst Haeckel.

Biography

Claus studied at the University of Marburg and the University of GieΟüen wi ...

, Professor of Zoology at the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (german: UniversitΟΛt Wien) is a public research university located in Vienna, Austria. It was founded by Duke Rudolph IV in 1365 and is the oldest university in the German-speaking world. With its long and rich histor ...

, who suggested to him the term "phagocyte" for a cell which can surround and kill pathogens. He delivered his findings at Odessa University in 1883.

His theory, that certain white blood cell

White blood cells, also called leukocytes or leucocytes, are the cell (biology), cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign invaders. All white blood cells are produced and de ...

s could engulf and destroy harmful bodies such as bacteria, met with scepticism from leading specialists including Louis Pasteur, Emil von Behring

Emil von Behring (; Emil Adolf von Behring), born Emil Adolf Behring (15 March 1854 βÄ™ 31 March 1917), was a German physiologist who received the 1901 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, the first one awarded in that field, for his discovery ...

, and others. At the time, most bacteriologists believed that white blood cells ingested pathogens and then spread them further through the body. His major supporter was Rudolf Virchow

Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow (; or ; 13 October 18215 September 1902) was a German physician, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and politician. He is known as "the father of modern pathology" and as the founder ...

, who published his research in his ''Archiv fΟΦr pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und fΟΦr klinische Medicin'' (now called the ''Virchows Archiv

''Virchows Archiv: European Journal of Pathology'' is a monthly peer-reviewed medical journal of all aspects of pathology, especially human pathology. It is published by Springer Science+Business Media and an official publication of the European ...

''). His discovery of these phagocytes

Phagocytes are cells that protect the body by ingesting harmful foreign particles, bacteria, and dead or dying cells. Their name comes from the Greek ', "to eat" or "devour", and "-cyte", the suffix in biology denoting "cell", from the Greek '' ...

ultimately won him the Nobel Prize in 1908. He worked with Οâmile Roux

Pierre Paul Οâmile Roux FRS (17 December 18533 November 1933) was a French physician, bacteriologist and immunologist. Roux was one of the closest collaborators of Louis Pasteur (1822βÄ™1895), a co-founder of the Pasteur Institute, and respon ...

on calomel

Calomel is a mercury chloride mineral with formula Hg2Cl2 (see mercury(I) chloride). The name derives from Greek ''kalos'' (beautiful) and ''melas'' (black) because it turns black on reaction with ammonia. This was known to alchemists.

Calomel ...

(mercurous chloride) in ointment form in an attempt to prevent people from contracting the sexually transmitted disease

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), also referred to as sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and the older term venereal diseases, are infections that are spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, and oral ...

syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

.

In 1887, he observed that leukocytes

White blood cells, also called leukocytes or leucocytes, are the cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign invaders. All white blood cells are produced and derived from mult ...

isolated from the blood of various animals were attracted towards certain bacteria. The first studies of leukocyte killing in the presence of specific antiserum were performed by Joseph Denys and Joseph Leclef, followed by Leon Marchand and Mennes between 1895 and 1898. Almoth E. Wright was the first to quantify this phenomenon and strongly advocated its potential therapeutic importance. The so-called resolution of the humoralist and cellularist positions by showing their respective roles in the setting of enhanced killing in the presence of opsonin

Opsonins are extracellular proteins that, when bound to substances or cells, induce phagocytes to phagocytose the substances or cells with the opsonins bound. Thus, opsonins act as tags to label things in the body that should be phagocytosed (i.e. ...

s was popularized by Wright after 1903, although Metchnikoff acknowledged the stimulatory capacity of immunosentisitized serum on phagotic function in the case of acquired immunity.

This attraction was soon proposed to be due to soluble elements released by the bacteria (see Harris for a review of this area up to 1953). Some 85 years after this seminal observation, laboratory studies showed that these elements were low molecular weight

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioch ...

(between 150 and 1500 Dalton (unit)

The dalton or unified atomic mass unit (symbols: Da or u) is a non-SI unit of mass widely used in physics and chemistry. It is defined as of the mass of an unbound neutral atom of carbon-12 in its nuclear and electronic ground state and at ...

s) N-formylated oligopeptides, including the most prominent member of this group, N-Formylmethionine-leucyl-phenylalanine

''N''-Formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF, fMLP or ''N''-formyl-met-leu-phe) is an ''N''- formylated tripeptide and sometimes simply referred to as chemotactic peptide is a potent polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) chemotactic factor and ...

, that are made by a variety of replicating gram positive bacteria

In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria are bacteria that give a positive result in the Gram stain test, which is traditionally used to quickly classify bacteria into two broad categories according to their type of cell wall.

Gram-positive bacte ...

and gram negative bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wall ...

. Metchnikoff's early observation, then, was the foundation for studies that defined a critical mechanism by which bacteria attract leukocytes to initiate and direct the innate immune response of acute inflammation

Inflammation (from la, wikt:en:inflammatio#Latin, inflammatio) is part of the complex biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or Irritation, irritants, and is a protective response involving im ...

to sites of host invasion by pathogens

In biology, a pathogen ( el, œÄΈ§ΈΗΈΩœ², "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

.

Metchnikoff also self-experimented with cholera that initially supported the probiotic

Probiotics are live microorganisms promoted with claims that they provide health benefits when consumed, generally by improving or restoring the gut microbiota. Probiotics are considered generally safe to consume, but may cause bacteria-host i ...

notion. During the 1892 cholera epidemic in France, he was surprised by the fact that the disease affected only some people but not others when they were equally exposed to the infection. To understand the differences in susceptibility to the disease, he drank a sample of cholera but never got sick. He tested on two volunteers of which one was not affected while the other almost died. He hypothesised that the difference in cholera infection was due to differences in intestinal microbes, speculating that those who have plenty of beneficial ones would be healthier.

The issues of aging occupied a significant place in Metchnikoff's works. Metchnikoff developed a theory that aging

Ageing ( BE) or aging ( AE) is the process of becoming older. The term refers mainly to humans, many other animals, and fungi, whereas for example, bacteria, perennial plants and some simple animals are potentially biologically immortal. In ...

is caused by toxic bacteria in the gut and that lactic acid

Lactic acid is an organic acid. It has a molecular formula . It is white in the solid state and it is miscible with water. When in the dissolved state, it forms a colorless solution. Production includes both artificial synthesis as well as natu ...

could prolong life. He attributed the longevity of Bulgarian peasants to their yogurt consumption that contained what was called the Bulgarian bacteria (now called ''Lactobacillus delbrueckii'' subsp. ''bulgaricus''). To validate his theory, he drank sour milk

Soured milk denotes a range of food products produced by the acidification of milk. Acidification, which gives the milk a tart taste, is achieved either through bacterial fermentation or through the addition of an acid, such as lemon juice or vin ...

every day throughout his life. His scientific reasonings on the subject were written in his books ''The Nature of Man: Studies in Optimistic Philosophy'' (1903) and more expressively in ''The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies'' (1907). He also espoused the potential life-lengthening properties of lactic acid bacteria such as ''Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus

''Lactobacillus delbrueckii'' subsp. ''bulgaricus'' (until 2014 known as ''Lactobacillus bulgaricus'') is one of over 200 published species in the ''Lactobacillus'' genome complex (LGC) and is the main bacterium used for the production of yogurt. ...

''. This concept of probiotic

Probiotics are live microorganisms promoted with claims that they provide health benefits when consumed, generally by improving or restoring the gut microbiota. Probiotics are considered generally safe to consume, but may cause bacteria-host i ...

s, which he termed "orthobiosis," was influential in his lifetime, but became ignored until the mid-1990s when experimental evidence emerged.

Awards and recognitions

Metchnikoff won the Karl Ernst von Baer prize in 1867 with Alexander Kovalevsky based on their doctoral research. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1908 with Paul Ehrlich . He was awarded honorary degree from theUniversity of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

in Cambridge, UK, and the Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is an award given by the Royal Society, for "outstanding achievements in research in any branch of science". It alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the biological sciences. Given every year, the medal is t ...

of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1906. He was given honorary memberships in the Academy of Medicine in Paris and the Academy of Sciences and Medicine in Saint Petersburg. The Leningrad Medical Institute of Hygiene and Sanitation, founded in 1911 was merged with Saint Petersburg State Medical Academy of Postgraduate Studies in 2011 to become the North-Western State Medical University, named after Metchnikoff. The Odessa I. I. Mechnikov National University is in Odessa, Ukraine.

Personal life and views

Metchnikoff married his first wife, Ludmila Feodorovitch, in 1869. She died from

Metchnikoff married his first wife, Ludmila Feodorovitch, in 1869. She died from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

on 20 April 1873. Her death, combined with other problems, caused Metchnikoff to attempt suicide, taking a large dose of opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

. In 1875, he married his student Olga Belokopytova. In 1885 Olga suffered from severe typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

and this led to his second suicide attempt. He injected himself with the spirochete

A spirochaete () or spirochete is a member of the phylum Spirochaetota (), (synonym Spirochaetes) which contains distinctive diderm (double-membrane) gram-negative bacteria, most of which have long, helically coiled (corkscrew-shaped or s ...

of relapsing fever

Relapsing fever is a vector-borne disease caused by infection with certain bacteria in the genus '' Borrelia'', which is transmitted through the bites of lice or soft-bodied ticks (genus ''Ornithodoros'').

Signs and symptoms

Most people who ar ...

. (Olga died in 1944 in Paris from typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

.)

Despite being baptized in the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

, Metchnikoff was an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

.

He was greatly influenced by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution. He first read Fritz MΟΦller

Johann Friedrich Theodor MΟΦller (31 March 1822 βÄ™ 21 May 1897), better known as Fritz MΟΦller, and also as MΟΦller-Desterro, was a German biologist who emigrated to southern Brazil, where he lived in and near the German community of Blumenau, ...

's ''FΟΦr Darwin'' (''For Darwin'') in Giessen. From this he became a supporter of natural selection and Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; 16 February 1834 βÄ™ 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new sp ...

's biogenetic law

The theory of recapitulation, also called the biogenetic law or embryological parallelismβÄîoften expressed using Ernst Haeckel's phrase "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny"βÄîis a historical hypothesis that the development of the embryo of an a ...

. His scientific works and theories were inspired by Darwinism.

Metchnikoff died in 1916 in Paris from heart failure. According to his will, his body was used for medical research

Medical research (or biomedical research), also known as experimental medicine, encompasses a wide array of research, extending from "basic research" (also called ''bench science'' or ''bench research''), – involving fundamental scientif ...

and afterwards cremated

Cremation is a method of final disposition of a dead body through burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India and Nepal, cremation on an open-air pyre i ...

in PΟ®re Lachaise Cemetery

PΟ®re Lachaise Cemetery (french: CimetiΟ®re du PΟ®re-Lachaise ; formerly , "East Cemetery") is the largest cemetery in Paris, France (). With more than 3.5 million visitors annually, it is the most visited necropolis in the world. Notable figures ...

crematorium. His cinerary urn has been placed in the Pasteur Institute

The Pasteur Institute (french: Institut Pasteur) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines f ...

library.

Publications

Metchnikoff wrote notable books and papers, including:''LeΟßons sur la pathologie comparΟ©e de lβÄôinflammation''

(1892; ''Lectures on the Comparative Pathology of Inflammation'')

''LβÄôImmunitΟ© dans les maladies infectieuses''

(1901; ''Immunity in Infectious Diseases'')

''Οâtudes sur la nature humaine''

(1903; ''The Nature of Man'')

''Immunity in Infective Diseases''

(1905)

''The New Hygiene: Three Lectures on the Prevention of Infectious Diseases''

(1906)

''The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies''

(1907) * * *

Explanatory notes

References

Further reading

* * ** * * * * * * * * *External links

The Romantic Rationalist: A Study Of Elie Metchnikoff

Works of Elie Metchnikoff, a Pasteur Institute bibliography

(In Russian)

Lactobacillus bulgaricus on the web

* ''Tsalyk St.''br>Immunity defender

*

Immunity in Infective Diseases

' (1905) by Οâlie Metchnikoff, translated by Francis B. Binny, on the Internet Archive *

The Prolongation of Life: Optimistic Studies

' (1908) by Οâlie Metchnikoff, translation edited by P. Chalmers Mitchell, on the Internet Archive

Luba Vikhanski's page for Metchnikoff's documentary

Mechnikov Ilya, 1845 - 1916, Year won 1908, A pioneer researcher of immunity

on th

ANU - Museum of the Jewish People

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Metchnikoff, Elie 1845 births 1916 deaths Academy of Fine Arts, Munich alumni Foreign Members of the Royal Society Emigrants from the Russian Empire to France Russian gerontologists Honorary members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences National University of Kharkiv alumni Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine Pasteur Institute People from Kharkiv Oblast Recipients of the Copley Medal Russian atheists Russian immunologists Russian people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent Russian Nobel laureates Russian people of Romanian descent Russian zoologists University of GΟΕttingen alumni