medieval cuisine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Medieval cuisine includes foods, eating habits, and cooking methods of various European cultures during the

Medieval cuisine includes foods, eating habits, and cooking methods of various European cultures during the

The

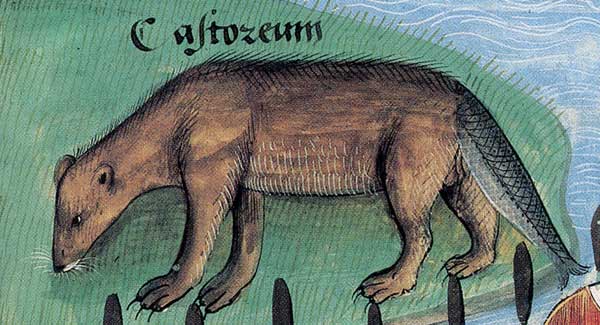

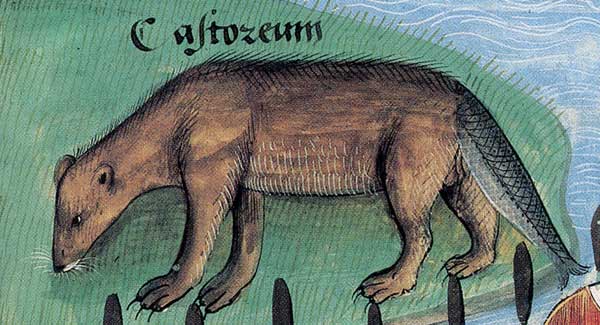

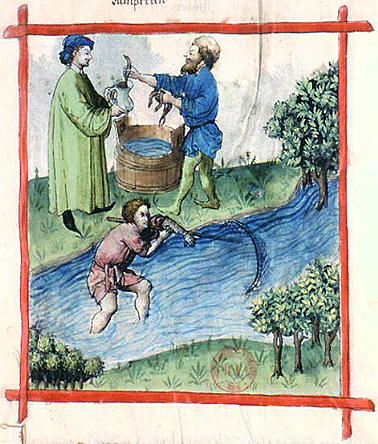

The  While animal products were to be avoided during times of penance, pragmatic compromises often prevailed. The definition of "fish" was often extended to marine and semi-aquatic animals such as

While animal products were to be avoided during times of penance, pragmatic compromises often prevailed. The definition of "fish" was often extended to marine and semi-aquatic animals such as

In Europe there were typically two meals a day:

In Europe there were typically two meals a day:

Things were different for the wealthy. Before the meal and between courses, shallow basins and

Things were different for the wealthy. Before the meal and between courses, shallow basins and

All types of cooking involved the direct use of fire. Kitchen stoves did not appear until the 18th century, and cooks had to know how to cook directly over an open fire. Ovens were used, but they were expensive to construct and existed only in fairly large households and bakeries. It was common for a

All types of cooking involved the direct use of fire. Kitchen stoves did not appear until the 18th century, and cooks had to know how to cook directly over an open fire. Ovens were used, but they were expensive to construct and existed only in fairly large households and bakeries. It was common for a

In most households, cooking was done on an open hearth in the middle of the main living area, to make efficient use of the heat. This was the most common arrangement, even in wealthy households, for most of the Middle Ages, where the kitchen was combined with the dining hall. Towards the

In most households, cooking was done on an open hearth in the middle of the main living area, to make efficient use of the heat. This was the most common arrangement, even in wealthy households, for most of the Middle Ages, where the kitchen was combined with the dining hall. Towards the  The kitchen staff of huge noble or royal courts occasionally numbered in the hundreds: pantlers, bakers, waferers, sauciers, larderers,

The kitchen staff of huge noble or royal courts occasionally numbered in the hundreds: pantlers, bakers, waferers, sauciers, larderers,

The majority of the European population before

The majority of the European population before

The period between c. 500 and 1300 saw a major change in diet that affected most of Europe. More intense agriculture on ever-increasing acreage resulted in a shift from animal products, like meat and dairy, to various grains and vegetables as the staple of the majority population. Before the 14th century, bread was not as common among the lower classes, especially in the north where wheat was more difficult to grow. A bread-based diet became gradually more common during the 15th century and replaced warm intermediate meals that were porridge- or gruel-based. Leavened bread was more common in

The period between c. 500 and 1300 saw a major change in diet that affected most of Europe. More intense agriculture on ever-increasing acreage resulted in a shift from animal products, like meat and dairy, to various grains and vegetables as the staple of the majority population. Before the 14th century, bread was not as common among the lower classes, especially in the north where wheat was more difficult to grow. A bread-based diet became gradually more common during the 15th century and replaced warm intermediate meals that were porridge- or gruel-based. Leavened bread was more common in  The importance of bread as a daily staple meant that bakers played a crucial role in any medieval community. Bread consumption was high in most of Western Europe by the 14th century. Estimates of bread consumption from different regions are fairly similar: around of bread per person per day. Among the first town

The importance of bread as a daily staple meant that bakers played a crucial role in any medieval community. Bread consumption was high in most of Western Europe by the 14th century. Estimates of bread consumption from different regions are fairly similar: around of bread per person per day. Among the first town

Fruits were popular and could be served fresh, dried, or preserved, and was a common ingredient in many cooked dishes. Since honey and sugar were both expensive, it was common to include many types of fruit in dishes that called for sweeteners of some sort. The fruits of choice in the south were

Fruits were popular and could be served fresh, dried, or preserved, and was a common ingredient in many cooked dishes. Since honey and sugar were both expensive, it was common to include many types of fruit in dishes that called for sweeteners of some sort. The fruits of choice in the south were

While all forms of wild

While all forms of wild

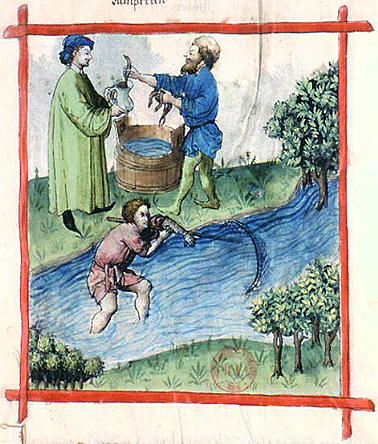

Although less prestigious than other animal meats, and often seen as merely an alternative to meat on fast days, seafood was the mainstay of many coastal populations. "Fish" to the medieval person was also a general name for anything not considered a proper land-living animal, including

Although less prestigious than other animal meats, and often seen as merely an alternative to meat on fast days, seafood was the mainstay of many coastal populations. "Fish" to the medieval person was also a general name for anything not considered a proper land-living animal, including

full text at Google Books

/ref> Such foods were also considered appropriate for fast days, though rather contrived classification of barnacle geese as fish was not universally accepted. The Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II examined barnacles and noted no evidence of any bird-like embryo in them, and the secretary of Leo of Rozmital wrote a very skeptical account of his reaction to being served barnacle goose at a fish-day dinner in 1456. Especially important was the fishing and trade in

While in modern times,

While in modern times,

Wine was commonly drunk and was also regarded as the most prestigious and healthy choice. According to

Wine was commonly drunk and was also regarded as the most prestigious and healthy choice. According to

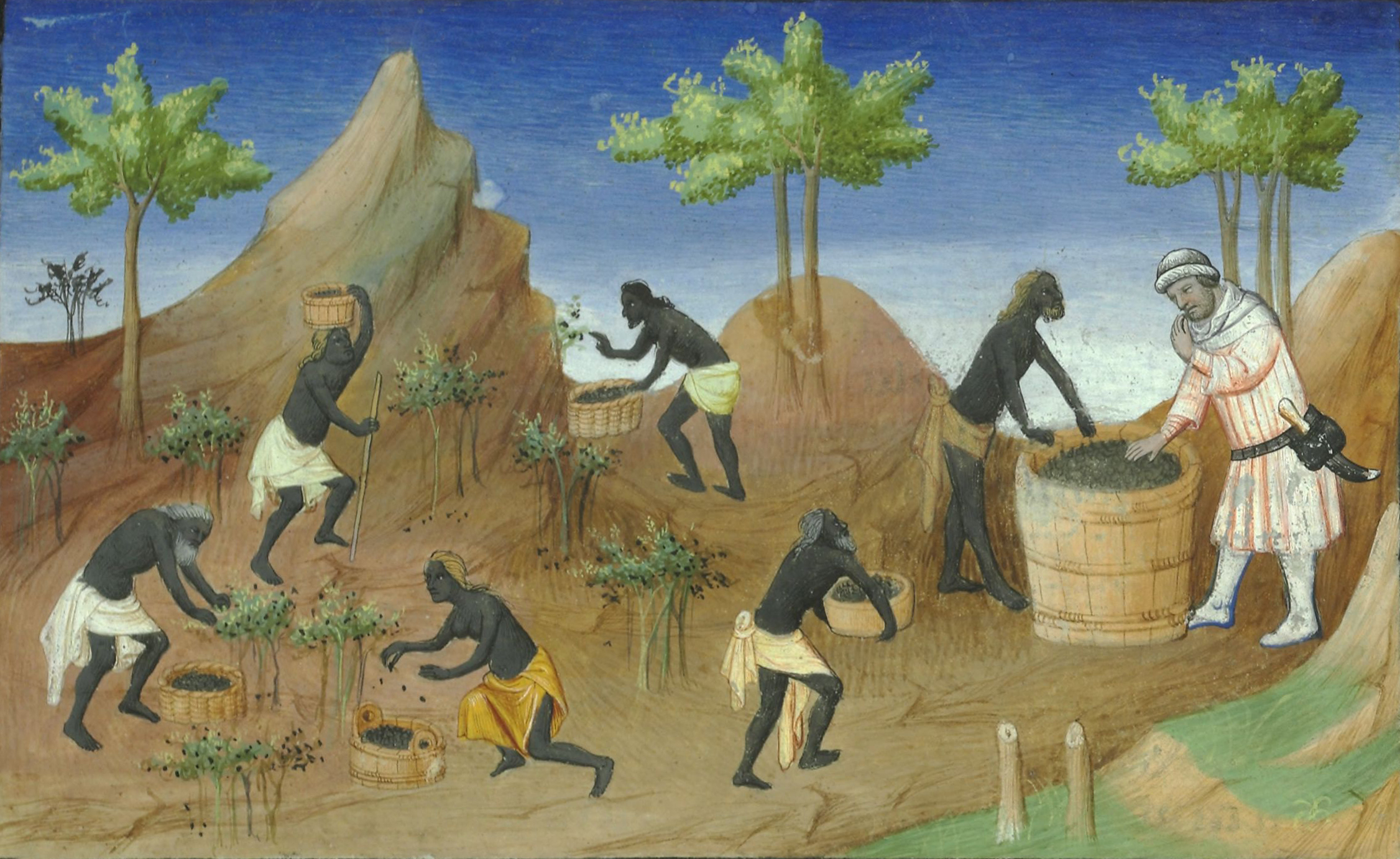

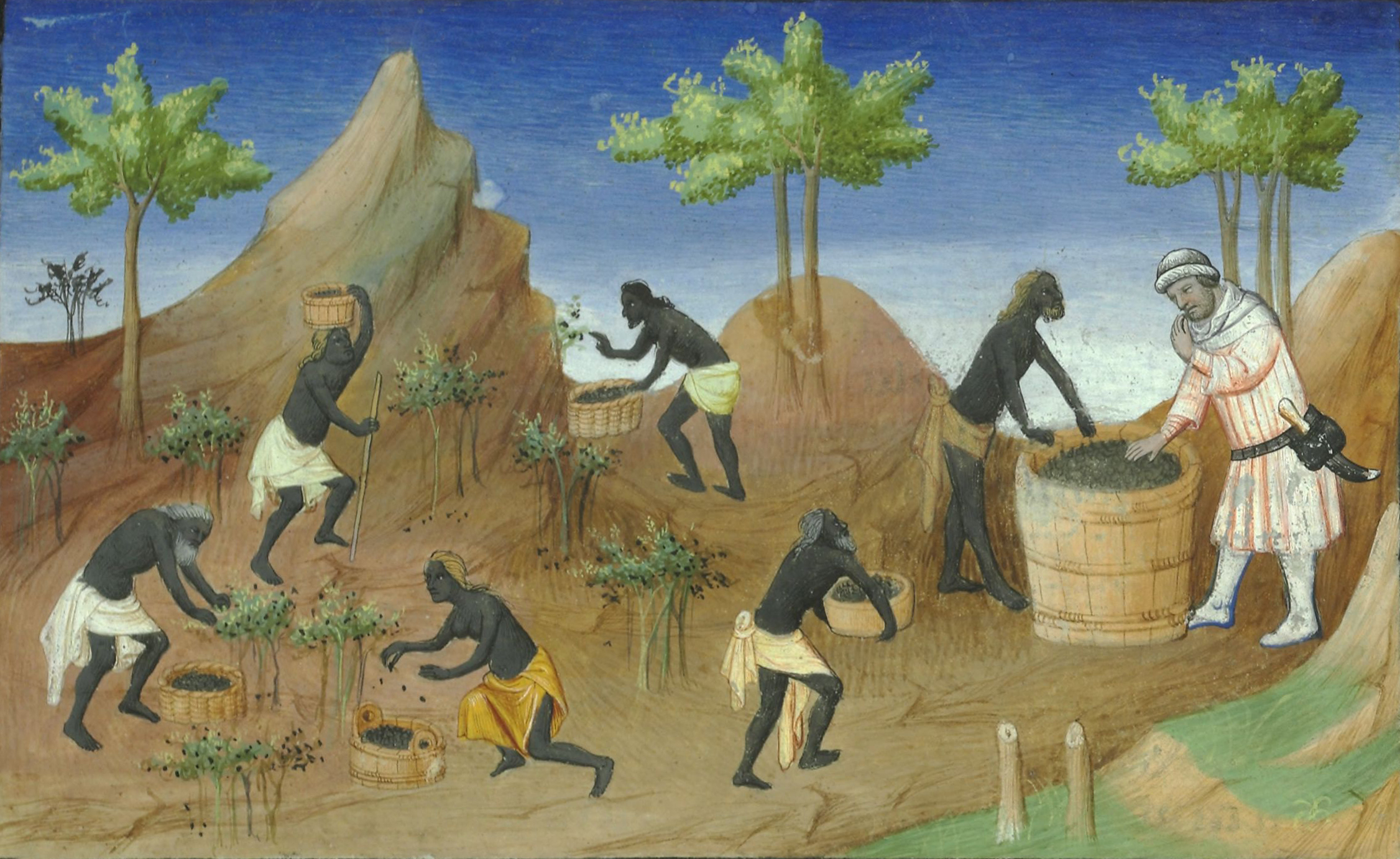

Spices were among the most luxurious products available in the Middle Ages, the most common being

Spices were among the most luxurious products available in the Middle Ages, the most common being  Surviving medieval recipes frequently call for flavoring with a number of sour, tart liquids. Wine, verjuice (the juice of unripe grapes or fruits) vinegar and the juices of various fruits, especially those with tart flavors, were almost universal and a hallmark of late medieval cooking. In combination with sweeteners and spices, it produced a distinctive "pungeant, fruity" flavor. Equally common, and used to complement the tanginess of these ingredients, were (sweet) almonds. They were used in a variety of ways: whole, shelled or unshelled, slivered, ground and, most importantly, processed into almond milk. This last type of non-dairy milk product is probably the single most common ingredient in late medieval cooking and blended the aroma of spices and sour liquids with a mild taste and creamy texture.

Salt was ubiquitous and indispensable in medieval cooking. Salting and drying was the most common form of food preservation and meant that fish and meat in particular were often heavily salted. Many medieval recipes specifically warn against oversalting and there were recommendations for soaking certain products in water to get rid of excess salt. Salt was present during more elaborate or expensive meals. The richer the host, and the more prestigious the guest, the more elaborate would be the container in which it was served and the higher the quality and price of the salt. Wealthy guests were seated "wikt:above the salt, above the salt", while others sat "below the salt", where salt cellars were made of pewter, precious metals or other fine materials, often intricately decorated. The rank of a diner also decided how finely ground and white the salt was. Salt for cooking, preservation or for use by common people was coarser; sea salt, or "bay salt", in particular, had more impurities, and was described in colors ranging from black to green. Expensive salt, on the other hand, looked like the standard commercial salt common today.

Surviving medieval recipes frequently call for flavoring with a number of sour, tart liquids. Wine, verjuice (the juice of unripe grapes or fruits) vinegar and the juices of various fruits, especially those with tart flavors, were almost universal and a hallmark of late medieval cooking. In combination with sweeteners and spices, it produced a distinctive "pungeant, fruity" flavor. Equally common, and used to complement the tanginess of these ingredients, were (sweet) almonds. They were used in a variety of ways: whole, shelled or unshelled, slivered, ground and, most importantly, processed into almond milk. This last type of non-dairy milk product is probably the single most common ingredient in late medieval cooking and blended the aroma of spices and sour liquids with a mild taste and creamy texture.

Salt was ubiquitous and indispensable in medieval cooking. Salting and drying was the most common form of food preservation and meant that fish and meat in particular were often heavily salted. Many medieval recipes specifically warn against oversalting and there were recommendations for soaking certain products in water to get rid of excess salt. Salt was present during more elaborate or expensive meals. The richer the host, and the more prestigious the guest, the more elaborate would be the container in which it was served and the higher the quality and price of the salt. Wealthy guests were seated "wikt:above the salt, above the salt", while others sat "below the salt", where salt cellars were made of pewter, precious metals or other fine materials, often intricately decorated. The rank of a diner also decided how finely ground and white the salt was. Salt for cooking, preservation or for use by common people was coarser; sea salt, or "bay salt", in particular, had more impurities, and was described in colors ranging from black to green. Expensive salt, on the other hand, looked like the standard commercial salt common today.

Cookbooks, or more specifically, recipe collections, compiled in the Middle Ages are among the most important historical sources for medieval cuisine. The first cookbooks began to appear towards the end of the 13th century. The ''Liber de Coquina'', perhaps originating near Naples, and the ''Tractatus de modo preparandi'' have found a modern editor in Marianne Mulon, and a cookbook from Assisi found at Châlons-en-Champagne, Châlons-sur-Marne has been edited by Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat. Though it is assumed that they describe real dishes, food scholars do not believe they were used as cookbooks might be today, as a step-by-step guide through the cooking procedure that could be kept at hand while preparing a dish. Few in a kitchen, at those times, would have been able to read, and working texts have a low survival rate.

The recipes were often brief and did not give precise quantities. Cooking times and temperatures were seldom specified since accurate portable clocks were not available and since all cooking was done with fire. At best, cooking times could be specified as the time it took to say a certain number of prayers or how long it took to walk around a certain field. Professional cooks were taught their trade through apprenticeship and practical training, working their way up in the highly defined kitchen hierarchy. A medieval cook employed in a large household would most likely have been able to plan and produce a meal without the help of recipes or written instruction. Due to the generally good condition of surviving manuscripts it has been proposed by food historian Terence Scully that they were records of household practices intended for the wealthy and literate master of a household, such as ''Le Ménagier de Paris'' from the late 14th century. Over 70 collections of medieval recipes survive today, written in several major European languages.

The repertory of housekeeping instructions laid down by manuscripts like the ''Ménagier de Paris'' also include many details of overseeing correct preparations in the kitchen. Towards the onset of the early modern period, in 1474, the Vatican librarian Bartolomeo Platina wrote ''De honesta voluptate et valetudine'' ("On honourable pleasure and health") and the physician Iodocus Willich edited ''Apicius'' in Zürich in 1563.

High-status exotic spices and rarities like ginger, pepper, cloves, sesame, citron leaves and "onions of Escalon" all appear in an eighth-century list of spices that the Carolingian cook should have at hand. It was written by Vinidarius, whose excerpts of ''Apicius'' survive in an eighth-century Uncial script, uncial manuscript. Vinidarius' own dates may not be much earlier.The list, however, includes Silphium (antiquity), silphium, which had been extinct for centuries, so may have included some purely literary items; Toussaint-Samat (2009), p. 434.

Cookbooks, or more specifically, recipe collections, compiled in the Middle Ages are among the most important historical sources for medieval cuisine. The first cookbooks began to appear towards the end of the 13th century. The ''Liber de Coquina'', perhaps originating near Naples, and the ''Tractatus de modo preparandi'' have found a modern editor in Marianne Mulon, and a cookbook from Assisi found at Châlons-en-Champagne, Châlons-sur-Marne has been edited by Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat. Though it is assumed that they describe real dishes, food scholars do not believe they were used as cookbooks might be today, as a step-by-step guide through the cooking procedure that could be kept at hand while preparing a dish. Few in a kitchen, at those times, would have been able to read, and working texts have a low survival rate.

The recipes were often brief and did not give precise quantities. Cooking times and temperatures were seldom specified since accurate portable clocks were not available and since all cooking was done with fire. At best, cooking times could be specified as the time it took to say a certain number of prayers or how long it took to walk around a certain field. Professional cooks were taught their trade through apprenticeship and practical training, working their way up in the highly defined kitchen hierarchy. A medieval cook employed in a large household would most likely have been able to plan and produce a meal without the help of recipes or written instruction. Due to the generally good condition of surviving manuscripts it has been proposed by food historian Terence Scully that they were records of household practices intended for the wealthy and literate master of a household, such as ''Le Ménagier de Paris'' from the late 14th century. Over 70 collections of medieval recipes survive today, written in several major European languages.

The repertory of housekeeping instructions laid down by manuscripts like the ''Ménagier de Paris'' also include many details of overseeing correct preparations in the kitchen. Towards the onset of the early modern period, in 1474, the Vatican librarian Bartolomeo Platina wrote ''De honesta voluptate et valetudine'' ("On honourable pleasure and health") and the physician Iodocus Willich edited ''Apicius'' in Zürich in 1563.

High-status exotic spices and rarities like ginger, pepper, cloves, sesame, citron leaves and "onions of Escalon" all appear in an eighth-century list of spices that the Carolingian cook should have at hand. It was written by Vinidarius, whose excerpts of ''Apicius'' survive in an eighth-century Uncial script, uncial manuscript. Vinidarius' own dates may not be much earlier.The list, however, includes Silphium (antiquity), silphium, which had been extinct for centuries, so may have included some purely literary items; Toussaint-Samat (2009), p. 434.

Medieval Food – academic articles and videos

The History Notes website tells the story about the food and drink in the Middle Ages

– An online translation of the 14th century cookbook by James Prescott

– Learning resources on the medieval kitchen

– A guide on how to make medieval cuisine with modern ingredients

''The Forme of Cury''

– A late 14th-century English cookbook, available from Project Gutenberg

''Cariadoc's Miscellany''

– A collection of articles and recipes on medieval and Renaissance food

MedievalCookery.com

– Recipes, information, and notes about cooking in medieval Europe

– online exhibit of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris about food, cooking and meals as shown in paintings and images of medieval manuscripts *

Feeding the poor in medieval Catalonia

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Medieval Cuisine Medieval cuisine,

Medieval cuisine includes foods, eating habits, and cooking methods of various European cultures during the

Medieval cuisine includes foods, eating habits, and cooking methods of various European cultures during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, which lasted from the fifth to the fifteenth century. During this period, diets and cooking changed less than they did in the early modern period that followed, when those changes helped lay the foundations for modern European cuisine

European cuisine comprises the cuisines of Europe "European Cuisine."Cereal

A cereal is any grass cultivated for the edible components of its grain (botanically, a type of fruit called a caryopsis), composed of the endosperm, germ, and bran. Cereal grain crops are grown in greater quantities and provide more foo ...

s remained the most important staple during the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the M ...

as rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species '' Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly '' Oryza glaberrima'' (African rice). The name wild rice is usually used for species of the genera '' Zizania'' and ''Porteresia'', both wild and domestica ...

was introduced late, and the potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Un ...

was only introduced in 1536, with a much later date for widespread consumption. Barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley ...

, oats, and rye

Rye (''Secale cereale'') is a grass grown extensively as a grain, a cover crop and a forage crop. It is a member of the wheat tribe (Triticeae) and is closely related to both wheat (''Triticum'') and barley (genus ''Hordeum''). Rye grain is u ...

were eaten by the poor. Wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeolog ...

was for the governing classes. These were consumed as bread, porridge

Porridge is a food made by heating or boiling ground, crushed or chopped starchy plants, typically grain, in milk or water. It is often cooked or served with added flavourings such as sugar, honey, (dried) fruit or syrup to make a sweet cereal, ...

, gruel, and pasta

Pasta (, ; ) is a type of food typically made from an unleavened dough of wheat flour mixed with water or eggs, and formed into sheets or other shapes, then cooked by boiling or baking. Rice flour, or legumes such as beans or lentils, are ...

by all of society's members. Cheese

Cheese is a dairy product produced in wide ranges of flavors, textures, and forms by coagulation of the milk protein casein. It comprises proteins and fat from milk, usually the milk of cows, buffalo, goats, or sheep. During product ...

, fruit

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in partic ...

s, and vegetable

Vegetables are parts of plants that are consumed by humans or other animals as food. The original meaning is still commonly used and is applied to plants collectively to refer to all edible plant matter, including the flowers, fruits, stems ...

s were important supplements to the cereal-based diet of the lower orders.

Meat was more expensive and therefore more prestigious. Game

A game is a structured form of play, usually undertaken for entertainment or fun, and sometimes used as an educational tool. Many games are also considered to be work (such as professional players of spectator sports or games) or art (su ...

, a form of meat acquired from hunting, was common only on the nobility's tables. The most prevalent butcher's meats were pork

Pork is the culinary name for the meat of the domestic pig (''Sus domesticus''). It is the most commonly consumed meat worldwide, with evidence of pig husbandry dating back to 5000 BCE.

Pork is eaten both freshly cooked and preserved ...

, chicken

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domestication, domesticated junglefowl species, with attributes of wild species such as the grey junglefowl, grey and the Ceylon junglefowl that are originally from Southeastern Asia. Rooster ...

, and other domestic fowl; beef

Beef is the culinary name for meat from cattle (''Bos taurus'').

In prehistoric times, humankind hunted aurochs and later domesticated them. Since that time, numerous breeds of cattle have been bred specifically for the quality or quant ...

, which required greater investment in land, was less common. A wide variety of freshwater and saltwater fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% ...

was also eaten, with cod and herring

Herring are forage fish, mostly belonging to the family of Clupeidae.

Herring often move in large schools around fishing banks and near the coast, found particularly in shallow, temperate waters of the North Pacific and North Atlantic Ocea ...

being mainstays among the northern populations.

Slow transportation and food preservation

Food preservation includes processes that make food more resistant to microorganism growth and slow the oxidation of fats. This slows down the decomposition and rancidification process. Food preservation may also include processes that inhi ...

techniques (based on drying

Drying is a mass transfer process consisting of the removal of water or another solvent by evaporation from a solid, semi-solid or liquid. This process is often used as a final production step before selling or packaging products. To be considere ...

, salting, smoking, and pickling

Pickling is the process of food preservation, preserving or extending the shelf life of food by either Anaerobic organism, anaerobic fermentation (food), fermentation in brine or immersion in vinegar. The pickling procedure typically affects th ...

) made long-distance trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exch ...

of many foods very expensive. Because of this, the nobility's food was more prone to foreign influence than the cuisine of the poor; it was dependent on exotic spices and expensive imports. As each level of society imitated the one above it, innovations from international trade and foreign wars from the 12th century onward gradually disseminated through the upper middle class of medieval cities. Aside from economic unavailability of luxuries such as spices, decrees outlawed consumption of certain foods among certain social classes and sumptuary laws limited conspicuous consumption

In sociology and in economics, the term conspicuous consumption describes and explains the consumer practice of buying and using goods of a higher quality, price, or in greater quantity than practical. In 1899, the sociologist Thorstein Veblen ...

among the nouveaux riches. Social norms also dictated that the food of the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colo ...

be less refined, since it was believed there was a natural resemblance between one's labour and one's food; manual labour required coarser, cheaper food.

A type of refined cooking developed in the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Ren ...

that set the standard among the nobility all over Europe. Common seasonings in the highly spiced sweet-sour repertory typical of upper-class medieval food included verjuice, wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink typically made from fermented grapes. Yeast consumes the sugar in the grapes and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Different varieties of grapes and strains of yeasts are ...

, and vinegar

Vinegar is an aqueous solution of acetic acid and trace compounds that may include flavorings. Vinegar typically contains 5–8% acetic acid by volume. Usually, the acetic acid is produced by a double fermentation, converting simple sugars to ...

in combination with spices such as black pepper

Black pepper (''Piper nigrum'') is a flowering vine in the family Piperaceae, cultivated for its fruit, known as a peppercorn, which is usually dried and used as a spice and seasoning. The fruit is a drupe (stonefruit) which is about in di ...

, saffron

Saffron () is a spice derived from the flower of ''Crocus sativus'', commonly known as the "saffron crocus". The vivid crimson stigma (botany), stigma and stigma (botany)#style, styles, called threads, are collected and dried for use mainly ...

, and ginger

Ginger (''Zingiber officinale'') is a flowering plant whose rhizome, ginger root or ginger, is widely used as a spice and a folk medicine. It is a herbaceous perennial which grows annual pseudostems (false stems made of the rolled bases of ...

. These, along with the widespread use of honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of plants (primar ...

or sugar, gave many dishes a sweet-sour flavor. Almonds were very popular as a thickener in soup

Soup is a primarily liquid food, generally served warm or hot (but may be cool or cold), that is made by combining ingredients of meat or vegetables with stock, milk, or water. Hot soups are additionally characterized by boiling soli ...

s, stews, and sauce

In cooking, a sauce is a liquid, cream, or semi-solid food, served on or used in preparing other foods. Most sauces are not normally consumed by themselves; they add flavor, moisture, and visual appeal to a dish. ''Sauce'' is a French word t ...

s, particularly as almond milk.

Dietary norms

The cuisines of the cultures of theMediterranean Basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and w ...

since antiquity had been based on cereals, particularly various types of wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeolog ...

. Porridge, gruel, and later bread became the basic staple foods that made up the majority of calorie intake for most of the population. From the 8th to the 11th centuries, the proportion of various cereals in the diet rose from about a third to three quarters.Hunt & Murray (1999), p. 16. Dependence on wheat remained significant throughout the medieval era, and spread northward with the rise of Christianity. In colder climates, however, it was usually unaffordable for the majority population, and was associated with the higher classes. The centrality of bread in religious rituals such as the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was institu ...

meant that it enjoyed an especially high prestige among foodstuffs. Only olive oil and wine had a comparable value, but both remained quite exclusive outside the warmer grape- and olive-growing regions. The symbolic role of bread as both sustenance and substance is illustrated in a sermon given by Saint Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

:

This bread retells your history … You were brought to the threshing floor of the Lord and were threshed … While awaiting catechism, you were like grain kept in the granary … At the baptismal font you were kneaded into a single dough. In the oven of the Holy Ghost you were baked into God's true bread.

The Church

The

The Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

and Orthodox Churches, and their calendars, had great influence on eating habits; consumption of meat was forbidden for a full third of the year for most Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

. All animal products, including eggs and dairy product

Dairy products or milk products, also known as lacticinia, are food products made from (or containing) milk. The most common dairy animals are cow, water buffalo, nanny goat, and ewe. Dairy products include common grocery store food items in ...

s (during the strictest fasting periods also fish), were generally prohibited during Lent

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and L ...

and fast

Fast or FAST may refer to:

* Fast (noun), high speed or velocity

* Fast (noun, verb), to practice fasting, abstaining from food and/or water for a certain period of time

Acronyms and coded Computing and software

* ''Faceted Application of Subje ...

. Additionally, it was customary for all citizens to fast before taking the Eucharist. These fasts were occasionally for a full day and required total abstinence.

Both the Eastern and the Western churches ordained that feast should alternate with fast. In most of Europe, Fridays were fast days, and fasting was observed on various other days and periods, including Lent and Advent

Advent is a Christian season of preparation for the Nativity of Christ at Christmas. It is the beginning of the liturgical year in Western Christianity.

The name was adopted from Latin "coming; arrival", translating Greek ''parousia''.

In ...

. Meat, and animal products such as milk, cheese, butter, and eggs, were not allowed, and at times also fish. The fast was intended to mortify the body and invigorate the soul, and also to remind the faster of Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religi ...

's sacrifice for humanity. The intention was not to portray certain foods as unclean, but rather to teach a spiritual lesson in self-restraint through abstention. During particularly severe fast days, the number of daily meals was also reduced to one. Even if most people respected these restrictions and usually made penance

Penance is any act or a set of actions done out of repentance for sins committed, as well as an alternate name for the Catholic, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox sacrament of Reconciliation or Confession. It also plays a pa ...

when they violated them, there were also numerous ways of circumventing them, a conflict of ideals and practice summarized by writer Bridget Ann Henisch:

It is the nature of man to build the most complicated cage of rules and regulations in which to trap himself, and then, with equal ingenuity and zest, to bend his brain to the problem of wriggling triumphantly out again. Lent was a challenge; the game was to ferret out the loopholes.

While animal products were to be avoided during times of penance, pragmatic compromises often prevailed. The definition of "fish" was often extended to marine and semi-aquatic animals such as

While animal products were to be avoided during times of penance, pragmatic compromises often prevailed. The definition of "fish" was often extended to marine and semi-aquatic animals such as whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and ...

s, barnacle geese

The barnacle goose (''Branta leucopsis'') is a species of goose that belongs to the genus ''Branta'' of black geese, which contains species with largely black plumage, distinguishing them from the grey ''Anser'' species. Despite its superficial s ...

, puffin

Puffins are any of three species of small alcids ( auks) in the bird genus ''Fratercula''. These are pelagic seabirds that feed primarily by diving in the water. They breed in large colonies on coastal cliffs or offshore islands, nesting in c ...

s, and even beaver

Beavers are large, semiaquatic rodents in the genus ''Castor'' native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. There are two extant species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers a ...

s. The choice of ingredients may have been limited, but that did not mean that meals were smaller. Neither were there any restrictions against (moderate) drinking or eating sweets. Banquets held on fish days could be splendid, and were popular occasions for serving illusion food that imitated meat, cheese, and eggs in various ingenious ways; fish could be moulded to look like venison

Venison originally meant the meat of a game animal but now refers primarily to the meat of antlered ungulates such as elk or deer (or antelope in South Africa). Venison can be used to refer to any part of the animal, so long as it is edible ...

and fake eggs could be made by stuffing empty egg shells with fish roe and almond milk and cooking them in coals. While Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

church officials took a hard-line approach, and discouraged any culinary refinement for the clergy, their Western counterparts were far more lenient.Henisch (1976), p. 43. There was also no lack of grumbling about the rigours of fasting among the laity. During Lent, kings and schoolboys, commoners and nobility, all complained about being deprived of meat for the long, hard weeks of solemn contemplation of their sins. At Lent, owners of livestock were even warned to keep an eye out for hungry dogs frustrated by a "hard siege by Lent and fish bones".

The trend from the 13th century onward was toward a more legalistic interpretation of fasting. Nobles were careful not to eat meat on fast days, but still dined in style; fish replaced meat, often as imitation hams and bacon; almond milk replaced animal milk as an expensive non-dairy alternative; faux eggs made from almond milk were cooked in blown-out eggshells, flavoured and coloured with exclusive spices. In some cases the lavishness of noble tables was outdone by Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, found ...

monasteries, which served as many as sixteen courses during certain feast days. Exceptions from fasting were frequently made for very broadly defined groups. Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

(c. 1225–1274) believed dispensation should be provided for children, the old, pilgrim

A pilgrim (from the Latin ''peregrinus'') is a traveler (literally one who has come from afar) who is on a journey to a holy place. Typically, this is a physical journey (often on foot) to some place of special significance to the adherent of ...

s, workers and beggars, but not the poor as long as they had some sort of shelter. There are many accounts of members of monastic orders who flouted fasting restrictions through clever interpretations of the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts o ...

. Since the sick were exempt from fasting, there often evolved the notion that fasting restrictions only applied to the main dining area, and many Benedictine friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the o ...

s would simply eat their fast day meals in what was called the misericord (at those times) rather than the refectory. Newly assigned Catholic monastery officials sought to amend the problem of fast evasion not merely with moral condemnations, but by making sure that well-prepared non-meat dishes were available on fast days.

Class constraints

Medieval society was highly stratified. In a time whenfamine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accom ...

was commonplace and social hierarchies were often brutally enforced, food was an important marker of social status in a way that has no equivalent today in most developed countries

A developed country (or industrialized country, high-income country, more economically developed country (MEDC), advanced country) is a sovereign state that has a high quality of life, developed economy and advanced technological infrastr ...

. According to the ideological norm, society consisted of the three estates of the realm

The estates of the realm, or three estates, were the broad orders of social hierarchy used in Christendom (Christian Europe) from the Middle Ages to early modern Europe. Different systems for dividing society members into estates developed an ...

: commoners, that is, the working classes—by far the largest group; the clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the t ...

, and the nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

. The relationship between the classes was strictly hierarchical, with the nobility and clergy claiming worldly and spiritual overlordship over commoners. Within the nobility and clergy there were also a number of ranks ranging from king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the ...

s and pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

s to duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of Royal family, royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, t ...

s, bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

s and their subordinates, such as priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

s. One was expected to remain in one's social class and to respect the authority of the ruling classes. Political power was displayed not just by rule, but also by displaying wealth. Nobles dined on fresh game seasoned with exotic spices, and displayed refined table manners; rough laborers could make do with coarse barley bread, salt pork and beans and were not expected to display etiquette. Even dietary recommendations were different: the diet of the upper classes was considered to be as much a requirement of their refined physical constitution as a sign of economic reality. The digestive system of a lord was held to be more discriminating than that of his rustic subordinates and demanded finer foods.

In the late Middle Ages, the increasing wealth of middle class merchants and traders meant that commoners began emulating the aristocracy, and threatened to break down some of the symbolic barriers between the nobility and the lower classes. The response came in two forms: didactic literature warning of the dangers of adapting a diet inappropriate for one's class, and sumptuary laws that put a cap on the lavishness of commoners' banquets.

Dietetics

Medical science of the Middle Ages had a considerable influence on what was considered healthy and nutritious among the upper classes. One's lifestyle—including diet, exercise, appropriate social behavior, and approved medical remedies—was the way to good health, and all types of food were assigned certain properties that affected a person's health. All foodstuffs were also classified on scales ranging from hot to cold and moist to dry, according to the four bodily humours theory proposed byGalen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be on ...

that dominated Western medical science from late Antiquity until the 17th century.

Medieval scholars considered human digestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food molecules into small water-soluble food molecules so that they can be absorbed into the watery blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intest ...

to be a process similar to cooking. The processing of food in the stomach was seen as a continuation of the preparation initiated by the cook. In order for the food to be properly "cooked" and for the nutrients to be properly absorbed, it was important that the stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach i ...

be filled in an appropriate manner. Easily digestible foods would be consumed first, followed by gradually heavier dishes. If this regimen were not respected it was believed that heavy foods would sink to the bottom of the stomach, thus blocking the digestion duct, so that food would digest very slowly and cause putrefaction

Putrefaction is the fifth stage of death, following pallor mortis, algor mortis, rigor mortis, and livor mortis. This process references the breaking down of a body of an animal, such as a human, post-mortem. In broad terms, it can be vie ...

of the body and draw bad humours into the stomach. It was also of vital importance that food of differing properties not be mixed.Scully (1995), pp. 135–136.

Before a meal, the stomach would preferably be "opened" with an '' apéritif'' (from Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

''aperire'', "to open") that was preferably of a hot and dry nature: confection

Confectionery is the Art (skill), art of making confections, which are food items that are rich in sugar and carbohydrates. Exact definitions are difficult. In general, however, confectionery is divided into two broad and somewhat overlappi ...

s made from honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of plants (primar ...

- or sugar-coated spices like ginger

Ginger (''Zingiber officinale'') is a flowering plant whose rhizome, ginger root or ginger, is widely used as a spice and a folk medicine. It is a herbaceous perennial which grows annual pseudostems (false stems made of the rolled bases of ...

, caraway, and seeds of anise, fennel

Fennel (''Foeniculum vulgare'') is a flowering plant species in the carrot family. It is a hardy, perennial herb with yellow flowers and feathery leaves. It is indigenous to the shores of the Mediterranean but has become widely naturalized ...

, or cumin, wine and sweetened fortified milk drinks. As the stomach had been opened, it should then be "closed" at the end of the meal with the help of a digestive, most commonly a dragée, which during the Middle Ages consisted of lumps of spiced sugar, or hypocras, a wine flavoured with fragrant spices, along with aged cheese. A meal would ideally begin with easily digestible fruit, such as apples. It would then be followed by vegetables such as cabbage, lettuce

Lettuce (''Lactuca sativa'') is an annual plant of the family Asteraceae. It is most often grown as a leaf vegetable, but sometimes for its stem and seeds. Lettuce is most often used for salads, although it is also seen in other kinds of foo ...

, purslane, herbs, moist fruits, light meats, such as chicken or goat kid, with pottage

Pottage or potage (, ; ) is a term for a thick soup or stew made by boiling vegetables, grains, and, if available, meat or fish. It was a staple food for many centuries. The word ''pottage'' comes from the same Old French root as ''potage'', ...

s and broth

Broth, also known as bouillon (), is a savory liquid made of water in which meat, fish or vegetables have been simmered for a short period of time. It can be eaten alone, but it is most commonly used to prepare other dishes, such as soups, ...

s. After that came the "heavy" meats, such as pork

Pork is the culinary name for the meat of the domestic pig (''Sus domesticus''). It is the most commonly consumed meat worldwide, with evidence of pig husbandry dating back to 5000 BCE.

Pork is eaten both freshly cooked and preserved ...

and beef

Beef is the culinary name for meat from cattle (''Bos taurus'').

In prehistoric times, humankind hunted aurochs and later domesticated them. Since that time, numerous breeds of cattle have been bred specifically for the quality or quant ...

, as well as vegetables and nuts, including pears and chestnuts, both considered difficult to digest. It was popular, and recommended by medical expertise, to finish the meal with aged cheese and various digestives.

The most ideal food was that which most closely matched the humour of human beings, i.e. moderately warm and moist. Food should preferably also be finely chopped, ground, pounded and strained to achieve a true mixture of all the ingredients. White wine was believed to be cooler than red and the same distinction was applied to red and white vinegar. Milk was moderately warm and moist, but the milk of different animals was often believed to differ. Egg yolks were considered to be warm and moist while the whites were cold and moist. Skilled cooks were expected to conform to the regimen of humoral medicine. Even if this limited the combinations of food they could prepare, there was still ample room for artistic variation by the chef.

Caloric structure

The caloric content and structure of medieval diet varied over time, from region to region, and between classes. However, for most people, the diet tended to be high-carbohydrate, with most of the budget spent on, and the majority of calories provided by, cereals and alcohol (such as beer). Even though meat was highly valued by all, lower classes often could not afford it, nor were they allowed by the church to consume it every day. In England in the 13th century, meat contributed a negligible portion of calories to a typical harvest worker's diet; however, its share increased after the Black Death and, by the 15th century, it provided about 20% of the total. Even among the lay nobility of medieval England, grain provided 65–70% of calories in the early 14th century,Woolgar (2006), p. 11 though a generous provision of meat and fish was included, and their consumption of meat increased in the aftermath of the Black Death as well. In one early-15th-century English aristocratic household for which detailed records are available (that of the Earl of Warwick), gentle members of the household received a staggering of assorted meats in a typical meat meal in the autumn and in the winter, in addition to of bread and of beer or possibly wine (and there would have been two meat meals per day, five days a week, except during Lent). In the household of Henry Stafford in 1469, gentle members received of meat per meal, and all others received , and everyone was given of bread and of alcohol. On top of these quantities, some members of these households (usually, a minority) ate breakfast, which would not include any meat, but would probably include another of beer; and uncertain quantities of bread and ale could have been consumed in between meals. The diet of the lord of the household differed somewhat from this structure, including less red meat, more high-quality wild game, fresh fish, fruit, and wine. In monasteries, the basic structure of the diet was laid down by the Rule of Saint Benedict in the 7th century and tightened byPope Benedict XII

Pope Benedict XII ( la, Benedictus XII, french: Benoît XII; 1285 – 25 April 1342), born Jacques Fournier, was head of the Catholic Church from 30 December 1334 to his death in April 1342. He was the third Avignon pope. Benedict was a careful ...

in 1336, but (as mentioned above) monks were adept at "working around" these rules. Wine was restricted to about per day, but there was no corresponding limit on beer, and, at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, each monk was given an allowance of of beer per day. Meat of "four-footed animals" was prohibited altogether, year-round, for everyone but the very weak and the sick. This was circumvented in part by declaring that offal, and various processed foods such as bacon

Bacon is a type of salt-cured pork made from various cuts, typically the belly or less fatty parts of the back. It is eaten as a side dish (particularly in breakfasts), used as a central ingredient (e.g., the bacon, lettuce, and tomato sa ...

, were not meat. Secondly, Benedictine monasteries contained a room called the misericord, where the Rule of Saint Benedict did not apply, and where a large number of monks ate. Each monk would be regularly sent either to the misericord or to the refectory. When Pope Benedict XII ruled that at least half of all monks should be required to eat in the refectory on any given day, monks responded by excluding the sick and those invited to the abbot's table from the reckoning. Overall, a monk at Westminster Abbey in the late 15th century would have been allowed of bread per day; 5 eggs per day, except on Fridays and in Lent; of meat per day, four days per week (excluding Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday), except in Advent and Lent; and of fish per day, three days per week and every day during Advent and Lent. This caloric structure partly reflected the high-class status of late Medieval monasteries in England, and partly that of Westminster Abbey, which was one of the richest monasteries in the country; diets of monks in other monasteries may have been more modest.

The overall caloric intake is subject to some debate. One typical estimate is that an adult peasant male needed per day, and an adult female needed . Both lower and higher estimates have been proposed. Those engaged in particularly heavy physical labor, as well as sailors and soldiers, may have consumed or more per day. Intakes of aristocrats may have reached per day. Monks consumed per day on "normal" days, and per day when fasting. As a consequence of these excesses, obesity was common among upper classes. Monks, especially, frequently suffered from obesity-related (in some cases) conditions such as arthritis.

Regional variation

The regional specialties that are a feature of early modern and contemporary cuisine were not in evidence in the sparser documentation that survives. Instead, medieval cuisine can be differentiated by the cereals and the oils that shaped dietary norms and crossed ethnic and, later, national boundaries. Geographical variation in eating was primarily the result of differences in climate, political administration, and local customs that varied across the continent. Though sweeping generalizations should be avoided, more or less distinct areas where certain foodstuffs dominated can be discerned. In theBritish Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles (O ...

, northern France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

, the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, the northern German-speaking areas, Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

and the Baltic, the climate was generally too harsh for the cultivation of grape

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry (botany), berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus ''Vitis''. Grapes are a non-Climacteric (botany), climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters.

The cultivation of ...

s and olive

The olive, botanical name ''Olea europaea'', meaning 'European olive' in Latin, is a species of small tree or shrub in the family Oleaceae, found traditionally in the Mediterranean Basin. When in shrub form, it is known as ''Olea europaea'' ...

s. In the south, wine was the common drink for both rich and poor alike (though the commoner usually had to settle for cheap second- pressing wine) while beer

Beer is one of the oldest and the most widely consumed type of alcoholic drink in the world, and the third most popular drink overall after water and tea. It is produced by the brewing and fermentation of starches, mainly derived from cer ...

was the commoner's drink in the north and wine an expensive import. Citrus fruits (though not the kinds most common today) and pomegranate

The pomegranate (''Punica granatum'') is a fruit-bearing deciduous shrub in the family Lythraceae, subfamily Punicoideae, that grows between tall.

The pomegranate was originally described throughout the Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean re ...

s were common around the Mediterranean. Dried figs

The fig is the edible fruit of ''Ficus carica'', a species of small tree in the flowering plant family Moraceae. Native to the Mediterranean and western Asia, it has been cultivated since ancient times and is now widely grown throughout the worl ...

and dates were available in the north, but were used rather sparingly in cooking.

Olive oil

Olive oil is a liquid fat obtained from olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea''; family Oleaceae), a traditional tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin, produced by pressing whole olives and extracting the oil. It is commonly used in cooking: ...

was a ubiquitous ingredient in Mediterranean cultures, but remained an expensive import in the north where oils of poppy, walnut, hazel, and filbert were the most affordable alternatives. Butter and lard

Lard is a semi-solid white fat product obtained by rendering the fatty tissue of a pig.Lard

entry in the ...

, especially after the terrible mortality during the Black Death made them less scarce, were used in considerable quantities in the northern and northwestern regions, especially in the Low Countries. Almost universal in middle and upper class cooking all over Europe was the almond, which was in the ubiquitous and highly versatile almond milk, which was used as a substitute in dishes that otherwise required eggs or milk, though the bitter variety of almonds came along much later.

entry in the ...

Meals

In Europe there were typically two meals a day:

In Europe there were typically two meals a day: dinner

Dinner usually refers to what is in many Western cultures the largest and most formal meal of the day, which is eaten in the evening. Historically, the largest meal used to be eaten around midday, and called dinner. Especially among the elit ...

at mid-day and a lighter supper in the evening. The two-meal system remained consistent throughout the late Middle Ages. Smaller intermediate meals were common, but became a matter of social status, as those who did not have to perform manual labor could go without them.Eszter Kisbán, "Food Habits in Change: The Example of Europe" in ''Food in Change'', pp. 2–4. Moralists

Moralism is any philosophy with the central focus of applying moral judgements. The term is commonly used as a pejorative to mean "being overly concerned with making moral judgments or being illiberal in the judgments one makes".

Moralism has s ...

frowned on breaking the overnight fast too early, and members of the church and cultivated gentry avoided it. For practical reasons, breakfast was still eaten by working men, and was tolerated for young children, women, the elderly and the sick. Because the church preached against gluttony

Gluttony ( la, gula, derived from the Latin ''gluttire'' meaning "to gulp down or swallow") means over-indulgence and over-consumption of food, drink, or wealth items, particularly as status symbols.

In Christianity, it is considered a sin ...

and other weaknesses of the flesh, men tended to be ashamed of the weak practicality of breakfast. Lavish dinner banquets and late-night ''reresopers'' (from Occitan ''rèire-sopar'', "late supper") with considerable alcoholic beverage

An alcoholic beverage (also called an alcoholic drink, adult beverage, or a drink) is a drink that contains ethanol, a type of alcohol that acts as a drug and is produced by fermentation of grains, fruits, or other sources of sugar. The c ...

consumption were considered immoral. The latter were especially associated with gambling, crude language, drunkenness, and lewd behavior.Henisch (1976), p. 17. Minor meals and snacks were common (although also disliked by the church), and working men commonly received an allowance from their employers in order to buy ''nuncheons'', small morsels to be eaten during breaks.

Etiquette

As with almost every part of life at the time, a medieval meal was generally a communal affair. The entire household, including servants, would ideally dine together. To sneak off to enjoy private company was considered a haughty and inefficient egotism in a world where people depended very much on each other. In the 13th century, Englishbishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

Robert Grosseteste advised the Countess of Lincoln: "forbid dinners and suppers out of hall, in secret and in private rooms, for from this arises waste and no honour to the lord and lady." He also recommended watching that the servants not make off with leftovers to make merry at rere-suppers, rather than giving it as alms. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, the wealthy increasingly sought to escape this regime of stern collectivism. When possible, rich hosts retired with their consorts to private chambers where the meal could be enjoyed in greater exclusivity and privacy. Being invited to a lord's chambers was a great privilege and could be used as a way to reward friends and allies and to awe subordinates. It allowed lords to distance themselves further from the household and to enjoy more luxurious treats while serving inferior food to the rest of the household that still dined in the great hall. At major occasions and banquets, however, the host and hostess generally dined in the great hall with the other diners. Although there are descriptions of dining etiquette on special occasions, less is known about the details of day-to-day meals of the elite or about the table manners of the common people and the destitute. However, it can be assumed there were no such extravagant luxuries as multiple courses, luxurious spices or hand-washing in scented water in everyday meals.

Things were different for the wealthy. Before the meal and between courses, shallow basins and

Things were different for the wealthy. Before the meal and between courses, shallow basins and linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong, absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also ...

towel

A towel is a piece of absorbent cloth or paper used for drying or wiping a surface. Towels draw moisture through direct contact.

In households, several types of towels are used, such as hand towels, bath towels, and kitchen towels.

Paper tow ...

s were offered to guests so they could wash their hands, as cleanliness was emphasized. Social codes made it difficult for women to uphold the ideal of immaculate neatness and delicacy while enjoying a meal, so the wife of the host often dined in private with her entourage or ate very little at such feasts. She could then join dinner only after the potentially messy business of eating was done. Overall, fine dining was a predominantly male affair, and it was uncommon for anyone but the most honored of guests to bring his wife or her ladies-in-waiting. The hierarchical nature of society was reinforced by etiquette

Etiquette () is the set of norms of personal behaviour in polite society, usually occurring in the form of an ethical code of the expected and accepted social behaviours that accord with the conventions and norms observed and practised by a ...

where the lower ranked were expected to help the higher, the younger to assist the elder, and men to spare women the risk of sullying dress and reputation by having to handle food in an unwomanly fashion. Shared drinking cups were common even at lavish banquets for all but those who sat at the high table, as was the standard etiquette of breaking bread and carving meat for one's fellow diners.

Food was mostly served on plates or in stew pots, and diners would take their share from the dishes and place it on trenchers of stale bread, wood or pewter with the help of spoon

A spoon is a utensil consisting of a shallow bowl (also known as a head), oval or round, at the end of a handle. A type of cutlery (sometimes called flatware in the United States), especially as part of a table setting, place setting, it is used ...

s or bare hands. In lower-class households it was common to eat food straight off the table. Knives were used at the table, but most people were expected to bring their own, and only highly favored guests would be given a personal knife. A knife was usually shared with at least one other dinner guest, unless one was of very high rank or well acquainted with the host. Forks for eating were not in widespread usage in Europe until the early modern period, and early on were limited to Italy. Even there it was not until the 14th century that the fork became common among Italians of all social classes. The change in attitudes can be illustrated by the reactions to the table manners of the Byzantine princess Theodora Doukaina in the late 11th century. She was the wife of Domenico Selvo, the Doge of Venice

The Doge of Venice ( ; vec, Doxe de Venexia ; it, Doge di Venezia ; all derived from Latin ', "military leader"), sometimes translated as Duke (compare the Italian '), was the chief magistrate and leader of the Republic of Venice between 726 ...

, and caused considerable dismay among upstanding Venetians. The foreign consort's insistence on having her food cut up by her eunuch

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castration, castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2n ...

servants and then eating the pieces with a golden fork shocked and upset the diners so much that there was a claim that Peter Damian, Cardinal Bishop of Ostia, later interpreted her refined foreign manners as pride

Pride is defined by Merriam-Webster as "reasonable self-esteem" or "confidence and satisfaction in oneself". A healthy amount of pride is good, however, pride sometimes is used interchangeably with "conceit" or "arrogance" (among other words) wh ...

and referred to her as "...the Venetian Doge's wife, whose body, after her excessive delicacy, entirely rotted away." However, this is ambiguous since Peter Damian died in 1072 or 1073, and their marriage (Theodora and Domenico) took place in 1075.

Food preparation

All types of cooking involved the direct use of fire. Kitchen stoves did not appear until the 18th century, and cooks had to know how to cook directly over an open fire. Ovens were used, but they were expensive to construct and existed only in fairly large households and bakeries. It was common for a

All types of cooking involved the direct use of fire. Kitchen stoves did not appear until the 18th century, and cooks had to know how to cook directly over an open fire. Ovens were used, but they were expensive to construct and existed only in fairly large households and bakeries. It was common for a community

A community is a social unit (a group of living things) with commonality such as place, norms, religion, values, customs, or identity. Communities may share a sense of place situated in a given geographical area (e.g. a country, villag ...

to have shared ownership of an oven to ensure that the bread baking essential to everyone was made communal rather than private. There were also portable ovens designed to be filled with food and then buried in hot coals, and even larger ones on wheels that were used to sell pies in the streets of medieval towns. But for most people, almost all cooking was done in simple stewpots, since this was the most efficient use of firewood and did not waste precious cooking juices, making potages and stews the most common dishes. Overall, most evidence suggests that medieval dishes had a fairly high fat content, or at least when fat could be afforded. This was considered less of a problem in a time of back-breaking toil, famine, and a greater acceptance—even desirability—of plumpness; only the poor or sick, and devout ascetics, were thin.

Fruit

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in partic ...

was readily combined with meat, fish and eggs. The recipe for ''Tart de brymlent'', a fish pie from the recipe collection '' The Forme of Cury'', includes a mix of figs, raisin

A raisin is a dried grape. Raisins are produced in many regions of the world and may be eaten raw or used in cooking, baking, and brewing. In the United Kingdom, Ireland, New Zealand, and Australia, the word ''raisin'' is reserved for the d ...

s, apple

An apple is an edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus domestica''). Apple trees are cultivated worldwide and are the most widely grown species in the genus '' Malus''. The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ances ...

s, and pears with fish (salmon

Salmon () is the common name

In biology, a common name of a taxon or organism (also known as a vernacular name, English name, colloquial name, country name, popular name, or farmer's name) is a name that is based on the normal language of ...

, cod, or haddock

The haddock (''Melanogrammus aeglefinus'') is a saltwater ray-finned fish from the family Gadidae, the true cods. It is the only species in the monotypic genus ''Melanogrammus''. It is found in the North Atlantic Ocean and associated seas w ...

) and pitted damson plum

A plum is a fruit of some species in ''Prunus'' subg. ''Prunus'.'' Dried plums are called prunes.

History

Plums may have been one of the first fruits domesticated by humans. Three of the most abundantly cultivated species are not found ...

s under the top crust. It was considered important to make sure that the dish agreed with contemporary standards of medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, and Health promotion ...

and dietetics. This meant that food had to be "tempered" according to its nature by an appropriate combination of preparation and mixing certain ingredients, condiment

A condiment is a preparation that is added to food, typically after cooking, to impart a specific flavor, to enhance the flavor, or to complement the dish. A table condiment or table sauce is more specifically a condiment that is served separat ...

s and spices; fish was seen as being cold and moist, and best cooked in a way that heated and dried it, such as frying or oven baking, and seasoned with hot and dry spices; beef was dry and hot and should therefore be boiled; pork was hot and moist and should therefore always be roasted

Roasting is a cooking method that uses dry heat where hot air covers the food, cooking it evenly on all sides with temperatures of at least from an open flame, oven, or other heat source. Roasting can enhance the flavor through caramelizati ...

. In some recipe collections, alternative ingredients were assigned with more consideration to the humoral nature than what a modern cook would consider to be similarity in taste. In a recipe for quince

The quince (; ''Cydonia oblonga'') is the sole member of the genus ''Cydonia'' in the Malinae subtribe (which also contains apples and pears, among other fruits) of the Rosaceae family. It is a deciduous tree that bears hard, aromatic brigh ...

pie, cabbage is said to work equally well, and in another turnip

The turnip or white turnip (''Brassica rapa'' subsp. ''rapa'') is a root vegetable commonly grown in temperate climates worldwide for its white, fleshy taproot. The word ''turnip'' is a compound (linguistics), compound of ''turn'' as in turned/r ...

s could be replaced by pears.Scully (1995), p. 70.

The completely edible shortcrust

Shortcrust pastry is a type of pastry often used for the base of a tart, quiche, pie, or (in the British English sense) flan. Shortcrust pastry can be used to make both sweet and savory pies such as apple pie, quiche, lemon meringue or chicken ...

pie did not appear in recipes until the 15th century. Before that the pastry was primarily used as a cooking container in a technique known as huff paste. Extant recipe collections show that gastronomy

Gastronomy is the study of the relationship between food and culture, the art of preparing and serving rich or delicate and appetizing food, the cooking styles of particular regions, and the science of good eating. One who is well versed in gastr ...

in the Late Middle Ages developed significantly. New techniques, like the shortcrust pie and the clarification of jelly with egg whites began to appear in recipes in the late 14th century and recipes began to include detailed instructions instead of being mere memory aids to an already skilled cook.

Medieval kitchens

In most households, cooking was done on an open hearth in the middle of the main living area, to make efficient use of the heat. This was the most common arrangement, even in wealthy households, for most of the Middle Ages, where the kitchen was combined with the dining hall. Towards the

In most households, cooking was done on an open hearth in the middle of the main living area, to make efficient use of the heat. This was the most common arrangement, even in wealthy households, for most of the Middle Ages, where the kitchen was combined with the dining hall. Towards the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Ren ...

a separate kitchen

A kitchen is a room or part of a room used for cooking and food preparation in a dwelling or in a commercial establishment. A modern middle-class residential kitchen is typically equipped with a stove, a sink with hot and cold running water ...

area began to evolve. The first step was to move the fireplaces towards the walls of the main hall, and later to build a separate building or wing that contained a dedicated kitchen area, often separated from the main building by a covered arcade. This way, the smoke, odors and bustle of the kitchen could be kept out of sight of guests, and the fire risk lessened. Few medieval kitchens survive as they were "notoriously ephemeral structures".

Many basic variations of cooking utensils available today, such as frying pan

A frying pan, frypan, or skillet is a flat-bottomed pan used for frying, searing, and browning foods. It is typically in diameter with relatively low sides that flare outwards, a long handle, and no lid. Larger pans may have a small grab ha ...

s, pots

Pot may refer to:

Containers