giant freshwater stingray on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The giant freshwater stingray (''Urogymnus polylepis'', also widely known by the

There is a

There is a

The giant freshwater stingray has a thin, oval

The giant freshwater stingray has a thin, oval

junior synonym

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linn ...

''Himantura chaophraya'') is a species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

of stingray

Stingrays are a group of sea rays, which are cartilaginous fish related to sharks. They are classified in the suborder Myliobatoidei of the order Myliobatiformes and consist of eight families: Hexatrygonidae (sixgill stingray), Plesiobatidae ...

in the family Dasyatidae. It is found in large river

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of ...

s and estuaries

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environme ...

in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

and Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and e ...

, though historically it may have been more widely distributed in South and Southeast Asia. The largest freshwater fish and the largest stingray in the world, this species grows up to across and can reach up to in weight. It has a relatively thin, oval pectoral fin

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as se ...

disc that is widest anteriorly, and a sharply pointed snout with a protruding tip. Its tail is thin and whip-like, and lacks fin folds. This species is uniformly grayish brown above and white below; the underside of the pectoral and pelvic fin

Pelvic fins or ventral fins are paired fins located on the ventral surface of fish. The paired pelvic fins are homologous to the hindlimbs of tetrapods.

Structure and function Structure

In actinopterygians, the pelvic fin consists of two ...

s bear distinctive wide, dark bands on their posterior margins.

Bottom-dwelling in nature, the giant freshwater stingray inhabits sandy or muddy areas and preys on small fishes and invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chorda ...

s. Females give live birth to litters of one to four pups, which are sustained to term by maternally produced histotroph

Uterine glands or endometrial glands are tubular glands, lined by ciliated columnar epithelium, found in the functional layer of the endometrium that lines the uterus. Their appearance varies during the menstrual cycle. During the proliferative ph ...

("uterine milk"). This species faces heavy fishing pressure for meat, recreation

Recreation is an activity of leisure, leisure being discretionary time. The "need to do something for recreation" is an essential element of human biology and psychology. Recreational activities are often done for enjoyment, amusement, or plea ...

, and aquarium

An aquarium (plural: ''aquariums'' or ''aquaria'') is a vivarium of any size having at least one transparent side in which aquatic plants or animals are kept and displayed. Fishkeepers use aquaria to keep fish, invertebrates, amphibians, aq ...

display, as well as extensive habitat degradation

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss and habitat reduction) is the process by which a natural habitat becomes incapable of supporting its native species. The organisms that previously inhabited the site are displaced or dead, thereby ...

and fragmentation. These forces have resulted in substantial population declines in at least central Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

and Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand ...

. As a result, the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

(IUCN) has assessed the giant freshwater stingray as Endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and in ...

.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The firstscientific description

A species description is a formal description of a newly discovered species, usually in the form of a scientific paper. Its purpose is to give a clear description of a new species of organism and explain how it differs from species that have b ...

of the giant freshwater stingray was authored by Dutch ichthyologist

Ichthyology is the branch of zoology devoted to the study of fish, including bony fish ( Osteichthyes), cartilaginous fish ( Chondrichthyes), and jawless fish ( Agnatha). According to FishBase, 33,400 species of fish had been described as of O ...

Pieter Bleeker

Pieter Bleeker (10 July 1819 – 24 January 1878) was a Dutch medical doctor, ichthyologist, and herpetologist. He was famous for the ''Atlas Ichthyologique des Indes Orientales Néêrlandaises'', his monumental work on the fishes of East Asia ...

in an 1852 volume of the journal

A journal, from the Old French ''journal'' (meaning "daily"), may refer to:

*Bullet journal, a method of personal organization

*Diary, a record of what happened over the course of a day or other period

*Daybook, also known as a general journal, a ...

''Verhandelingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen''. His account was based on a juvenile specimen across, collected from Jakarta, Indonesia. Bleeker named the new species ''polylepis'', from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''poly'' ("many") and ''lepis'' ("scales"), and assigned it to the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

''Trygon'' (now a synonym of ''Dasyatis

''Dasyatis'' (Greek δασύς ''dasýs'' meaning rough or dense and βατίς ''batís'' meaning skate) is a genus of stingray in the family Dasyatidae that is native to the Atlantic, including the Mediterranean. In a 2016 taxonomic revisi ...

''). However, in subsequent years Bleeker's description was largely overlooked, and in 1990 the giant freshwater stingray was described again by Supap Monkolprasit and Tyson Roberts in an issue of the ''Japanese Journal of Ichthyology''. They gave it the name ''Himantura chaophraya'', which came into widespread usage. In 2008, Peter Last and B. Mabel Manjaji-Matsumoto confirmed that ''T. polylepis'' and ''H. chaophraya'' refer to the same species, and since Bleeker's name was published earlier, the scientific name of the giant freshwater stingray became ''Himantura polylepis''. This species may also be called the giant freshwater whipray, giant stingray, or freshwater whipray.

There is a

There is a complex

Complex commonly refers to:

* Complexity, the behaviour of a system whose components interact in multiple ways so possible interactions are difficult to describe

** Complex system, a system composed of many components which may interact with each ...

of similar freshwater and estuarine stingrays in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Australasia

Australasia is a region that comprises Australia, New Zealand and some neighbouring islands in the Pacific Ocean. The term is used in a number of different contexts, including geopolitically, physiogeographically, philologically, and ecologi ...

that are or were tentatively identified with ''U. polylepis''. The Australian freshwater ''Urogymnus '' were described as a separate species, '' Urogymnus dalyensis'', in 2008. The freshwater ''Urogymnus'' in New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

are probably ''U. dalyensis'' rather than ''U. polylepis'', though confirmation awaits further study. ''Trygon fluviatilis'' from India, as described by Nelson Annandale

Thomas Nelson Annandale CIE FRSE (15 June 1876, in Edinburgh – 10 April 1924, in Calcutta) was a British zoologist, entomologist, anthropologist, and herpetologist. He was the founding director of the Zoological Survey of India.

Life

The eld ...

in 1909, closely resembles and may be conspecific

Biological specificity is the tendency of a characteristic such as a behavior or a biochemical variation to occur in a particular species.

Biochemist Linus Pauling stated that "Biological specificity is the set of characteristics of living organis ...

with ''U. polylepis''. On the other hand, comparison of freshwater whipray DNA and amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha a ...

sequences between India and Thailand has revealed significant differences. Finally, additional research is needed to assess the degree of divergence amongst populations of ''U. polylepis'' inhabiting various drainage basin

A drainage basin is an area of land where all flowing surface water converges to a single point, such as a river mouth, or flows into another body of water, such as a lake or ocean. A basin is separated from adjacent basins by a perimeter, ...

s across its distribution, so as to determine whether further taxonomic differentiation is warranted.

In terms of the broader evolutionary relationships between the giant freshwater whipray and the rest of the family Dasyatidae, a 2012 phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

analysis based on mitochondrial DNA reported that it was most closely related to the porcupine ray (''Urogymnus asperrimus''), and that they in turn formed a clade with the mangrove whipray (''U. granulatus'') and the tubemouth whipray (''U. lobistoma''). This finding adds to a growing consensus that the genus ''Himantura'' ''sensu lato

''Sensu'' is a Latin word meaning "in the sense of". It is used in a number of fields including biology, geology, linguistics, semiotics, and law. Commonly it refers to how strictly or loosely an expression is used in describing any particular c ...

'' is paraphyletic.

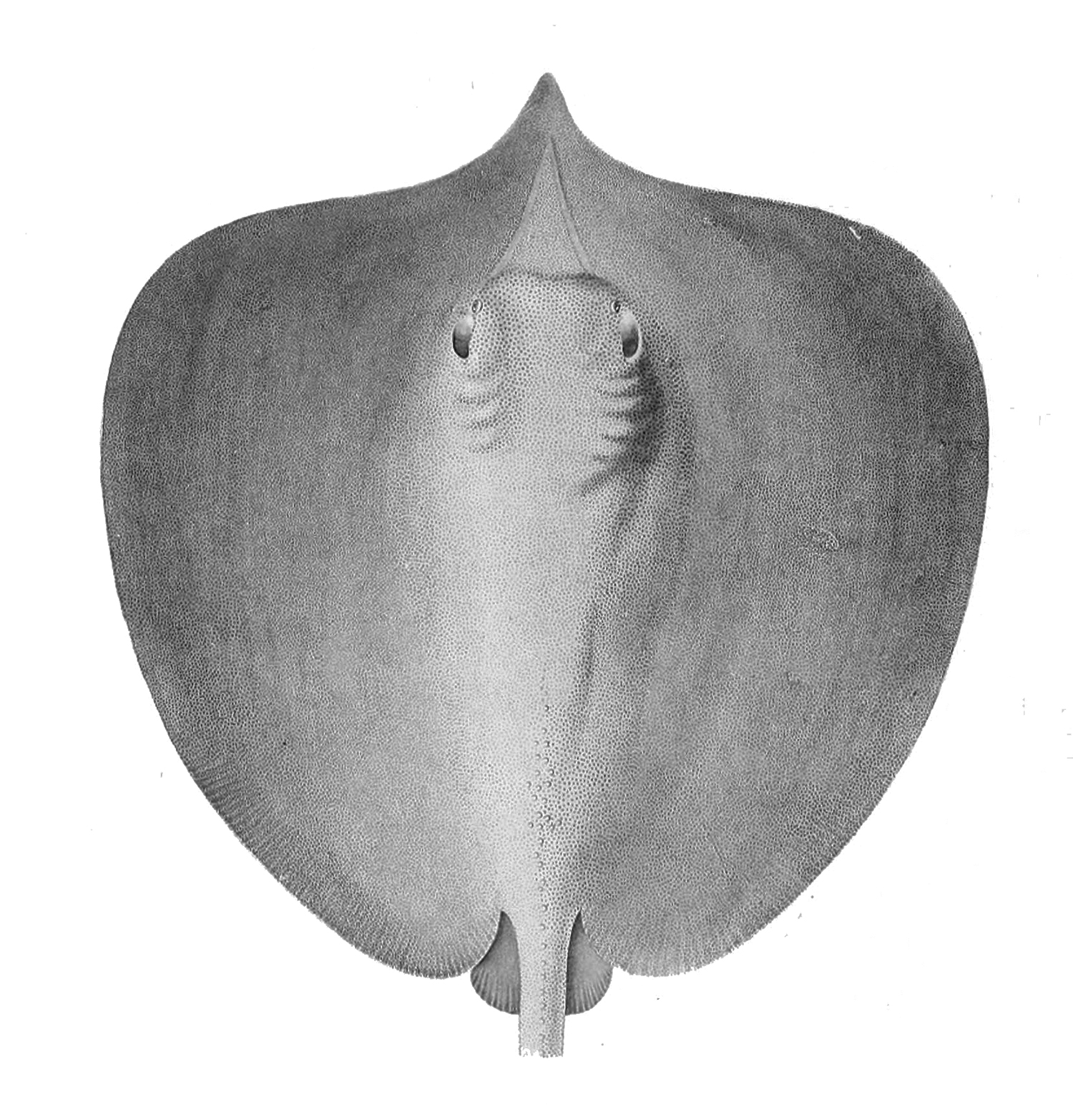

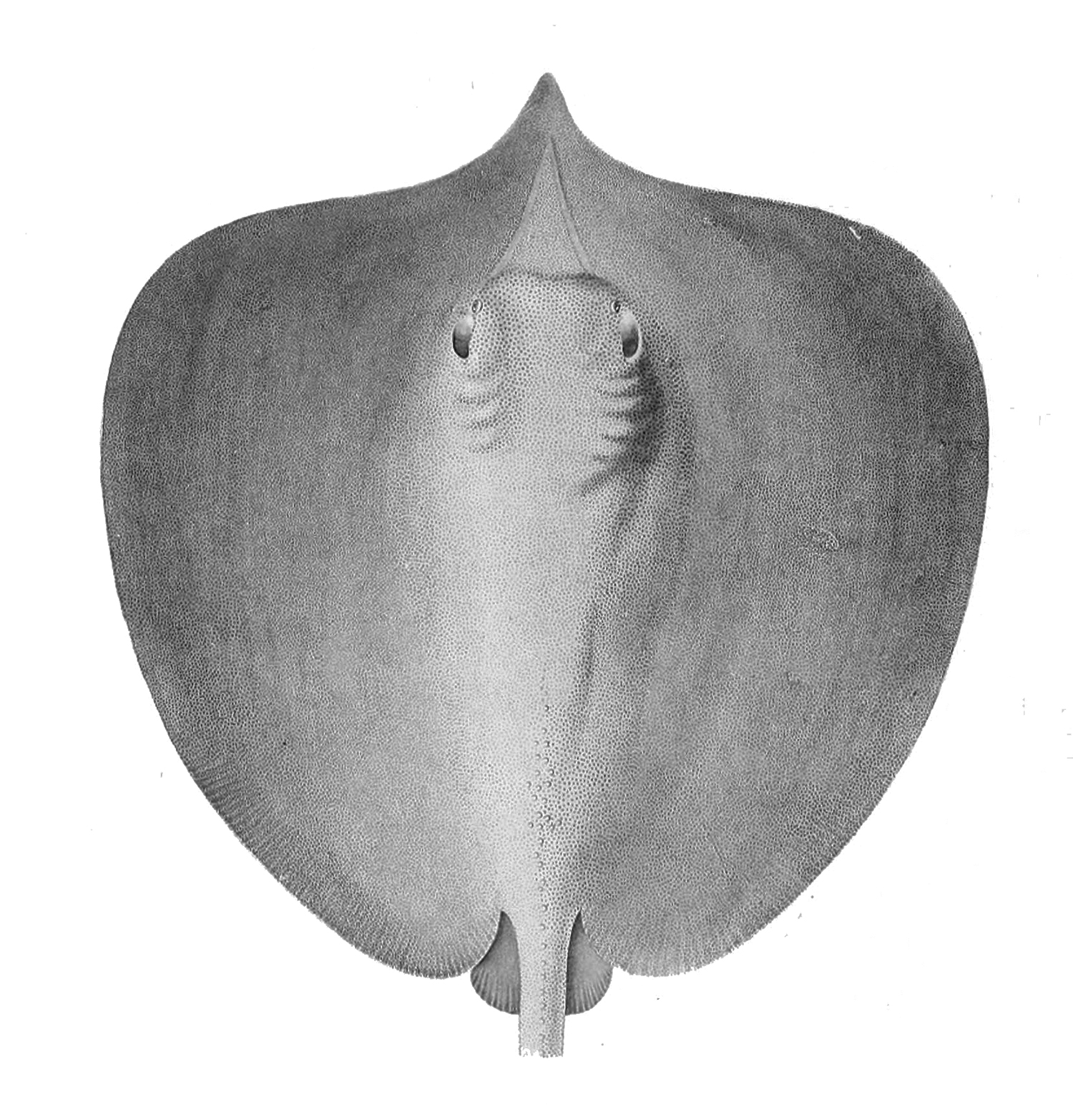

Description

pectoral fin

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as ...

disc slightly longer than wide and broadest towards the front. The elongated snout has a wide base and a sharply pointed tip that projects beyond the disc. The eyes are minute and widely spaced; behind them are large spiracles. Between the nostrils is a short curtain of skin with a finely fringed posterior margin. The small mouth forms a gentle arch and contains four to seven papillae (two to four large at the center and one to four small to the sides) on the floor. The small and rounded teeth are arranged into pavement-like bands. There are five pairs of gill slit

Gill slits are individual openings to gills, i.e., multiple gill arches, which lack a single outer cover. Such gills are characteristic of cartilaginous fish such as sharks and rays, as well as deep-branching vertebrates such as lampreys. In con ...

s on the ventral side of the disc. The pelvic fins

Pelvic fins or ventral fins are paired fins located on the ventral surface of fish. The paired pelvic fins are homologous to the hindlimbs of tetrapods.

Structure and function Structure

In actinopterygians, the pelvic fin consists of two e ...

are small and thin; mature males have relatively large clasper

In biology, a clasper is a male anatomical structure found in some groups of animals, used in mating.

Male cartilaginous fish have claspers formed from the posterior portion of their pelvic fin which serve to channel semen into the female's c ...

s.

The thin, cylindrical tail measures 1.8–2.5 times as long as the disc and lacks fin folds. A single serrated stinging spine is positioned on the upper surface of the tail near the base. At up to long, the spine is the largest of any stingray species. There is band of heart-shaped tubercles on the upper surface of the disc extending from before the eyes to the base of the sting; there is also a midline row of four to six enlarged tubercles at the center of the disc. The remainder of the disc upper surface is covered by tiny granular denticles, and the tail is covered with sharp prickles past the sting. This species is plain grayish brown above, often with a yellowish or pinkish tint towards the fin margins; in life the skin is coated with a layer of dark brown mucus

Mucus ( ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It ...

. The underside is white with broad dark bands, edged with small spots, on the trailing margins of the pectoral and pelvic fins. The tail is black behind the spine. The giant freshwater stingray reaches at least in width and in length, and can likely grow larger (It is not impossible that length is even , and width is

). With reports from the Mekong

The Mekong or Mekong River is a trans-boundary river in East Asia and Southeast Asia. It is the world's twelfth longest river and the third longest in Asia. Its estimated length is , and it drains an area of , discharging of water annual ...

and Chao Phraya Rivers of individuals weighing , but it is not impossible, that it is , or even - it ranks among the largest freshwater fishes in the world.

In June 2022 it was reported that a specimen caught in the Mekong river had broken the record for the largest ever freshwater fish ever documented. The individual weighed , and was measured at long and wide.

Distribution and habitat

The giant freshwater stingray is known to inhabit several large rivers and associated estuaries inIndochina

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

and Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and e ...

. In Indochina, it occurs in the Mekong River to potentially as far upstream as Chiang Khong in Thailand, as well as in the Chao Phraya, Nan

Nan or NAN may refer to:

Places China

* Nan County, Yiyang, Hunan, China

* Nan Commandery, historical commandery in Hubei, China

Thailand

* Nan Province

** Nan, Thailand, the administrative capital of Nan Province

* Nan River

People Given name

...

, Mae Klong

The Mae Klong (, , ), sometimes spelled Mae Khlong or Meklong, is a river in western Thailand. The river begins at the confluence of the Khwae Noi (Khwae Sai Yok) and the Khwae Yai River (Khwae Si Sawat) in Kanchanaburi, it passes Ratchaburi ...

, Bang Pakong, and Tapi Rivers, also found in Bueng Boraphet

Bueng Boraphet ( th, บึงบอระเพ็ด, ) is the largest freshwater swamp and lake in central Thailand. It covers an area of 224 km2 east of Nakhon Sawan, south of the Nan River close to its confluence with the Ping River. Thi ...

but now completely extinct. In Borneo, this species is found in the Mahakam River

The Mahakam River ( Indonesian: ''Sungai Mahakam'') is third longest and volume discharge river in Borneo after Kapuas River and Barito River, it is located in Kalimantan, Indonesia. It flows from the district of Long Apari in the highlands o ...

in Kalimantan and the Kinabatangan

Kinabatangan ( ms, Pekan Kinabatangan) is the capital of the Kinabatangan District in the Sandakan Division of Sabah, Malaysia. Its population was estimated to be around 10,256 in 2010. Kinabatangan is mostly populated with the Orang Sungai

...

and Buket Rivers in Sabah

Sabah () is a state of Malaysia located in northern Borneo, in the region of East Malaysia. Sabah borders the Malaysian state of Sarawak to the southwest and the North Kalimantan province of Indonesia to the south. The Federal Territory o ...

; it is reportedly common in the Kinabatangan River but infrequently caught. Though it has been reported from Sarawak

Sarawak (; ) is a state of Malaysia. The largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia, Sarawak is located in northwest Borneo Island, and is bordered by the Malaysian state of Sabah to the northeast, ...

as well, surveys within the past 25 years have not found it there. Elsewhere in the region, recent river surveys in Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mos ...

have not recorded its presence, despite the island being the locality of the species holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of sever ...

. Historical records from Myanmar, the Ganges River in India, and the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, bounded on the west and northwest by India, on the north by Bangladesh, and on the east by Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India. Its southern limit is a line betwee ...

(the latter two as ''Trygon fluviatilis'') have similarly not been corroborated by any recent accounts.

Disjunct populations of the giant freshwater stingray in separate river drainages are probably isolated from one another; though the species occurs in brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estu ...

environments, there is no evidence that it crosses marine waters. This is a bottom-dwelling species that favors a sandy or muddy habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

. Unexpectedly, it can sometimes be found near heavily populated urban areas.

Biology and ecology

The diet of the giant freshwater stingray consists of small, benthic fishes andinvertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chorda ...

s such as crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group can ...

s and molluscs, which it can detect using its electroreceptive ampullae of Lorenzini. Individuals can often be seen at the edge of the river, possibly feeding on earthworm

An earthworm is a terrestrial invertebrate that belongs to the phylum Annelida. They exhibit a tube-within-a-tube body plan; they are externally segmented with corresponding internal segmentation; and they usually have setae on all segments. T ...

s. Parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

s documented from this species include the tapeworm

Eucestoda, commonly referred to as tapeworms, is the larger of the two subclasses of flatworms in the class Cestoda (the other subclass is Cestodaria). Larvae have six posterior hooks on the scolex (head), in contrast to the ten-hooked Cesto ...

s '' Acanthobothrium asnihae'', '' A. etini'', '' A. masnihae'', '' A. saliki'', '' A. zainali'', '' Rhinebothrium abaiensis'', '' R. kinabatanganensis'', and '' R. megacanthophallus''. The giant freshwater stingray is viviparous

Among animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the parent. This is opposed to oviparity which is a reproductive mode in which females lay developing eggs that complete their development and hatch externally from the ...

, with the developing embryos nourished initially by yolk

Among animals which produce eggs, the yolk (; also known as the vitellus) is the nutrient-bearing portion of the egg whose primary function is to supply food for the development of the embryo. Some types of egg contain no yolk, for example ...

and later by histotroph

Uterine glands or endometrial glands are tubular glands, lined by ciliated columnar epithelium, found in the functional layer of the endometrium that lines the uterus. Their appearance varies during the menstrual cycle. During the proliferative ph ...

("uterine milk") provided by the mother. This species does not appear to be diadromous

Fish migration is mass relocation by fish from one area or body of water to another. Many types of fish migrate on a regular basis, on time scales ranging from daily to annually or longer, and over distances ranging from a few metres to thousa ...

(migrating between fresh and salt water to complete its life cycle). Observed litter sizes range from one to four pups; newborns measure around across. Pregnant females are frequently found in estuaries, which may serve as nursery areas. Males mature sexually at approximately across; female maturation size and other life history details are unknown.

Human interactions

The giant freshwater stingray is not aggressive, but its sting is sheathed in toxic mucus and is capable of piercing bone. Across its range, this species is caught incidentally by artisanal fishers using longlines, and to a lesser extent gillnets andfish trap

A fish trap is a trap used for fishing. Fish traps include fishing weirs, lobster traps, and some fishing nets such as fyke nets.

Traps are culturally almost universal and seem to have been independently invented many times. There are two ma ...

s. It is reputedly difficult and time-consuming to catch; a hooked ray may bury itself under large quantities of mud, becoming almost impossible to lift, or drag boats over substantial distances or underwater. The meat and the cartilage are used; large specimens are cut into kilogram pieces for sale. Adults that are not used for food are often killed or maimed by fishers nonetheless. In the Mae Klong and Bang Pakong Rivers, the giant freshwater stingray is also increasingly targeted by sport fishers and for display in public aquarium

A public aquarium (plural: ''public aquaria'' or ''public Water Zoo'') is the aquatic counterpart of a zoo, which houses living aquatic animal and plant specimens for public viewing. Most public aquariums feature tanks larger than those kept b ...

s. These trends pose conservation concerns; the former because catch and release

Catch and release is a practice within recreational fishing where after capture, often a fast measurement and weighing of the fish is performed, followed by posed photography as proof of the catch, and then the fish are unhooked and returned ...

is not universally practised and the post-release survival rate is unknown, the latter because this species does not survive well in captivity.

The major threats to the giant freshwater stingray are overfishing and habitat degradation

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss and habitat reduction) is the process by which a natural habitat becomes incapable of supporting its native species. The organisms that previously inhabited the site are displaced or dead, thereby ...

resulting from deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. The most concentrated ...

, land development, and dam

A dam is a barrier that stops or restricts the flow of surface water or underground streams. Reservoirs created by dams not only suppress floods but also provide water for activities such as irrigation, human consumption, industrial use ...

ming. The construction of dams also fragments the population, reducing genetic diversity and increasing the susceptibility of the resulting subpopulations to extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

. Due to its low reproductive rate, the giant freshwater stingray is not resilient to anthropogenic pressures. In central Thailand and Cambodia, the population is estimated to have been reduced by 30–50% over the past 20–30 years, with declines as severe as 95% in some locations. The size of rays caught has decreased significantly as well; for example, in Cambodia the average weight of a landed ray has dropped from in 1980 to in 2006. The status of populations in other areas, such as Borneo, is largely unknown. As a result of documented declines, the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

(IUCN) has assessed this species as Endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and in ...

overall, and as Critically Endangered in Thailand. In the 1990s, the Thai government initiated a captive breeding program at Chai Nat

Chai Nat ( th, ชัยนาท, ) is a town (''thesaban mueang'') in central Thailand, capital of Chai Nat province. It covers the whole ''tambon'' tambon Nai Mueang and parts of Ban Kluai, Tha Chai and Khao Tha Phra, all in Mueang Chai Nat ...

to bolster the population of this and other freshwater stingray species until the issue of habitat degradation can be remedied. However, by 1996 the program had been put on hold.

References

{{Good article Urogymnus Fish of Southeast Asia Fish of Thailand Taxa named by Pieter Bleeker Fish described in 1852