anthrax vaccine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anthrax vaccines are

/ref> No living organisms are present in the vaccine which results in protective immunity after 3 to 6 doses. AVA remains the only FDA-licensed human anthrax vaccine in the

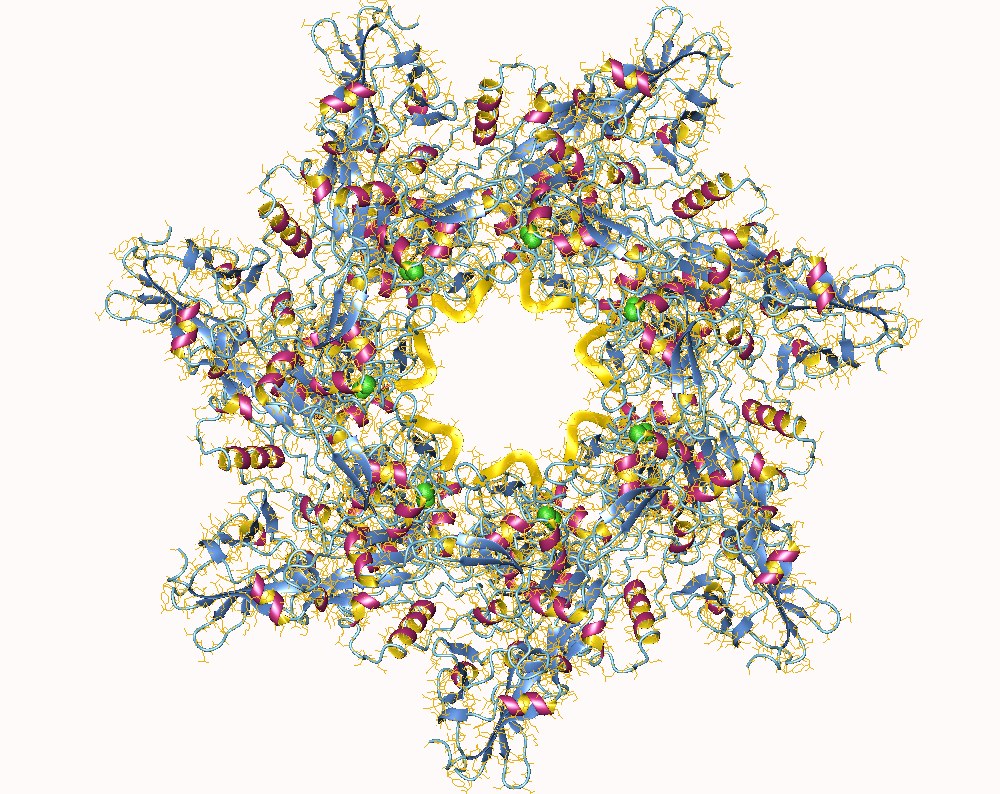

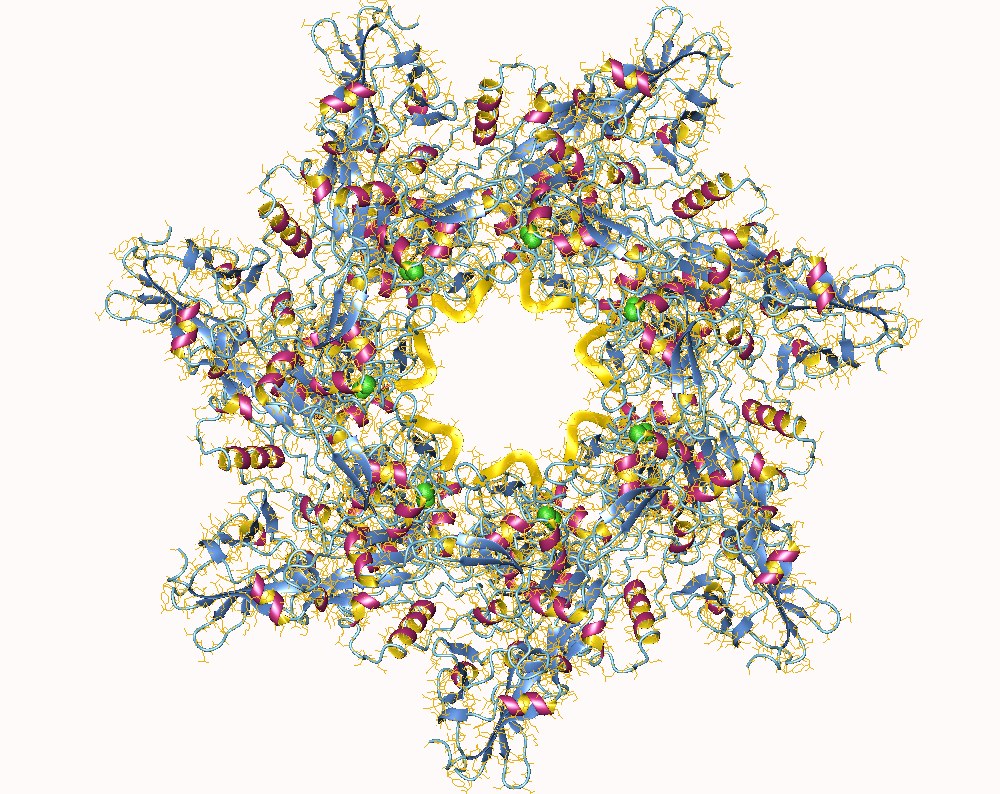

A number of experimental anthrax vaccines are undergoing pre-clinical testing, notably the ''Bacillus anthracis'' protective antigen—known as PA (see

A number of experimental anthrax vaccines are undergoing pre-clinical testing, notably the ''Bacillus anthracis'' protective antigen—known as PA (see

vaccines

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity

The adaptive immune system, also known as the acquired immune system, is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized, systemic cells and pro ...

to prevent the livestock and human disease anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The sk ...

, caused by the bacterium

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

''Bacillus anthracis

''Bacillus anthracis'' is a gram-positive and rod-shaped bacterium that causes anthrax, a deadly disease to livestock and, occasionally, to humans. It is the only permanent ( obligate) pathogen within the genus ''Bacillus''. Its infection is a ...

''.

They have had a prominent place in the history of medicine, from Pasteur's pioneering 19th-century work with cattle (the first effective bacterial

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifie ...

and the second effective vaccine ever) to the controversial late 20th century use of a modern product to protect American troops against the use of anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The sk ...

in biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. Bio ...

. Human anthrax vaccines were developed by the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

in the late 1930s and in the US and UK in the 1950s. The current vaccine approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respon ...

(FDA) was formulated in the 1960s.

Currently administered human anthrax vaccines include acellular (USA, UK) and live spore (Russia) varieties. All currently used anthrax vaccines show considerable local and general reactogenicity

In clinical trials, reactogenicity is the capacity of a vaccine to produce common, "expected" adverse reactions, especially excessive immunological responses and associated signs and symptoms, including fever and sore arm at the injection site. Ot ...

(erythema

Erythema (from the Greek , meaning red) is redness of the skin or mucous membranes, caused by hyperemia (increased blood flow) in superficial capillaries. It occurs with any skin injury, infection, or inflammation. Examples of erythema not assoc ...

, induration

A skin condition, also known as cutaneous condition, is any medical condition that affects the integumentary system—the organ system that encloses the body and includes skin, nails, and related muscle and glands. The major function of this sy ...

, soreness

Pain is a distressing feeling often caused by intense or damaging stimuli. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, ...

, fever

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a body temperature, temperature above the human body temperature, normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, set point. There is not a single ...

) and serious adverse reactions occur in about 1% of recipients. New third-generation vaccines being researched include recombinant live vaccines and recombinant sub-unit vaccines.

Pasteur's vaccine

In the 1870s, the French chemistLouis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named afte ...

(1822–1895) applied his previous method of immunising chickens against chicken cholera

Fowl cholera is also called avian cholera, avian pasteurellosis, avian hemorrhagic septicemia.

Abraham b.

It is the most common pasteurellosis of poultry. As the causative agent is ''Pasteurella multocida'', it is considered to be a zoonosis.

Adu ...

to anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The sk ...

, which affected cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult mal ...

, and thereby aroused widespread interest in combating other diseases with the same approach. In May 1881, Pasteur performed a famous public experiment at Pouilly-le-Fort to demonstrate his concept of vaccination. He prepared two groups of 25 sheep, one goat and several cows. The animals of one group were twice injected, with an interval of 15 days, with an anthrax vaccine prepared by Pasteur; a control group

In the design of experiments, hypotheses are applied to experimental units in a treatment group.

In comparative experiments, members of a control group receive a standard treatment, a placebo, or no treatment at all. There may be more than one tr ...

was left unvaccinated. Thirty days after the first injection, both groups were injected with a culture of live anthrax bacteria. All the animals in the non-vaccinated group died, while all of the animals in the vaccinated group survived. The public reception was sensational.

Pasteur publicly claimed he had made the anthrax vaccine by exposing the bacilli to oxygen. His laboratory notebooks, now in the Bibliothèque Nationale

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vir ...

in Paris, in fact show Pasteur used the method of rival Jean-Joseph-Henri Toussaint (1847–1890), a Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Par ...

veterinary surgeon

Veterinary surgery is surgery performed on animals by veterinarians, whereby the procedures fall into three broad categories: orthopaedics (bones, joints, muscles), soft tissue surgery (skin, body cavities, cardiovascular system, GI/urogenital/ ...

, to create the anthrax vaccine. This method used the oxidizing agent potassium dichromate

Potassium dichromate, , is a common inorganic chemical reagent, most commonly used as an oxidizing agent in various laboratory and industrial applications. As with all hexavalent chromium compounds, it is acutely and chronically harmful to health ...

. Pasteur's oxygen method did eventually produce a vaccine but only after he had been awarded a patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

on the production of an anthrax vaccine.

The notion of a weak form of a disease causing immunity to the virulent version was not new; this had been known for a long time for smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

. Inoculation with smallpox (variolation

Variolation was the method of inoculation first used to immunize individuals against smallpox (''Variola'') with material taken from a patient or a recently variolated individual, in the hope that a mild, but protective, infection would result. Var ...

) was known to result in far less scarring, and greatly reduced mortality, in comparison with the naturally acquired disease. The English physician Edward Jenner

Edward Jenner, (17 May 1749 – 26 January 1823) was a British physician and scientist who pioneered the concept of vaccines, and created the smallpox vaccine, the world's first vaccine. The terms ''vaccine'' and ''vaccination'' are derived f ...

(1749–1823) had also discovered (1796) the process of vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

by using cowpox

Cowpox is an infectious disease caused by the ''cowpox virus'' (CPXV). It presents with large blisters in the skin, a fever and swollen glands, historically typically following contact with an infected cow, though in the last several decades more ...

to give cross-immunity to smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and by Pasteur's time this had generally replaced the use of actual smallpox material in inoculation. The difference between smallpox vaccination and anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The sk ...

or chicken cholera

Fowl cholera is also called avian cholera, avian pasteurellosis, avian hemorrhagic septicemia.

Abraham b.

It is the most common pasteurellosis of poultry. As the causative agent is ''Pasteurella multocida'', it is considered to be a zoonosis.

Adu ...

vaccination was that the weakened form of the latter two disease organisms had been "generated artificially", so a naturally weak form of the disease organism did not need to be found. This discovery revolutionized work in infectious diseases and Pasteur gave these artificially weakened diseases the generic name "vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifie ...

s", in honor of Jenner's groundbreaking discovery. In 1885, Pasteur produced his celebrated first vaccine for rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. Early symptoms can include fever and tingling at the site of exposure. These symptoms are followed by one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, vi ...

by growing the virus in rabbits and then weakening it by drying the affected nerve tissue.

In 1995, the centennial of Pasteur's death, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' ran an article titled "Pasteur's Deception". After having thoroughly read Pasteur's lab notes, the science historian Gerald L. Geison

Gerald Lynn Geison (March 26, 1943 – July 3, 2001) was an American historian who died at 58.

Career

Gerald L. Geison went on to earn a doctorate in Yale University's ''Department of the History of Science and Medicine'' in 1970 and then joined ...

declared Pasteur had given a misleading account of the preparation of the anthrax vaccine used in the experiment at Pouilly-le-Fort. The same year, Max Perutz

Max Ferdinand Perutz (19 May 1914 – 6 February 2002) was an Austrian-born British molecular biologist, who shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Chemistry with John Kendrew, for their studies of the structures of haemoglobin and myoglobin. He went ...

published a vigorous defense of Pasteur in ''The New York Review of Books

''The New York Review of Books'' (or ''NYREV'' or ''NYRB'') is a semi-monthly magazine with articles on literature, culture, economics, science and current affairs. Published in New York City, it is inspired by the idea that the discussion of i ...

''.

Sterne's vaccine

The Austrian-South African immunologist Max Sterne (1905–1997) developed an attenuated live animal vaccine in 1935 that is still employed and derivatives of his strain account for almost all veterinary anthrax vaccines used in the world today. Beginning in 1934 at the Onderstepoort Veterinary Research Institute, north ofPretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends ...

, he prepared an attenuated anthrax vaccine, using the method developed by Pasteur. A persistent problem with Pasteur's vaccine was achieving the correct balance between virulence and immunogenicity during preparation. This notoriously difficult procedure regularly produced casualties among vaccinated animals. With little help from colleagues, Sterne performed small-scale experiments which isolated the "Sterne strain" (34F2) of anthrax which became, and remains today, the basis of most of the improved livestock anthrax vaccines throughout the world.

Russian anthrax vaccines

Anthrax vaccines were developed in the Soviet Union in the 1930s and available for use in humans by 1940. A live attenuated, unencapsulated spore vaccine became widely used for humans. It was given either by scarification or subcutaneously and its developers claimed that it was reasonably well tolerated and showed some degree of protective efficacy against cutaneous anthrax in clinical field trials. The efficacy of the live Russian vaccine was reported to have been greater than that of either of the killed British or US anthrax vaccines (AVP and AVA, respectively) during the 1970s and '80s. Today both Russia and China use live attenuated strains for their human vaccines. These vaccines may be given by aerosol, scarification, or subcutaneous injection. A Georgian/Russian live anthrax spore vaccine (called STI) was based on spores from the Sterne strain of ''B. anthracis''. It was given in a two-dose schedule, but serious side-effects restricted its use to healthy adults. It was reportedly manufactured at the George Eliava Institute of Bacteriophage, Microbiology and Virology inTbilisi, Georgia

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million peo ...

, until 1991.

British anthrax vaccines

British biochemist Harry Smith (1921–2011), working for the UK bio-weapons program atPorton Down

Porton Down is a science park in Wiltshire, England, just northeast of the village of Porton, near Salisbury. It is home to two British government facilities: a site of the Ministry of Defence's Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl ...

, discovered the three anthrax toxin

Anthrax toxin is a three-protein exotoxin secreted by virulent strains of the bacterium, ''Bacillus anthracis''—the causative agent of anthrax. The toxin was first discovered by Harry Smith in 1954. Anthrax toxin is composed of a cell-binding ...

s in 1948. This discovery was the basis of the next generation of antigenic anthrax vaccines and for modern antitoxin

An antitoxin is an antibody with the ability to neutralize a specific toxin. Antitoxins are produced by certain animals, plants, and bacterium, bacteria in response to toxin exposure. Although they are most effective in neutralizing toxins, the ...

s to anthrax. The widely used British anthrax vaccine—sometimes called Anthrax Vaccine Precipitated (AVP) to distinguish it from the similar AVA (see below)—became available for human use in 1954. This was a cell-free vaccine in distinction to the live-cell Pasteur-style vaccine previously used for veterinary purposes. It is now manufactured by Porton Biopharma Ltd, a Company owned by the UK Department of Health.

AVP is administered at primovaccination in three doses with a booster dose after six months. The active ingredient is a sterile filtrate of an alum

An alum () is a type of chemical compound, usually a hydrated double salt, double sulfate salt (chemistry), salt of aluminium with the general chemical formula, formula , where is a valence (chemistry), monovalent cation such as potassium or a ...

-precipitated anthrax antigen from the Sterne strain in a solution for injection. The other ingredients are aluminium potassium sulphate, sodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as salt (although sea salt also contains other chemical salts), is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. With molar masses of 22.99 and 35.45 g ...

and purified water. The preservative is thiomersal

Thiomersal (INN), or thimerosal (USAN, JAN), is an organomercury compound. It is a well-established antiseptic and antifungal agent.

The pharmaceutical corporation Eli Lilly and Company gave thiomersal the trade name Merthiolate. It has been u ...

(0.005%). The vaccine is given by intramuscular injection and the primary course of four single injections (3 injections 3 weeks apart, followed by a 6-month dose) is followed by a single booster dose given once a year. During the Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: ...

(1990–1991), UK military personnel were given AVP concomitantly with the pertussis vaccine

Pertussis vaccine is a vaccine that protects against whooping cough (pertussis). There are two main types: whole-cell vaccines and acellular vaccines. The whole-cell vaccine is about 78% effective while the acellular vaccine is 71–85% effectiv ...

as an adjuvant to improve overall immune response and efficacy.

American anthrax vaccines

TheUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

undertook basic research directed at producing a new anthrax vaccine during the 1950s and '60s. The product known as Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed (AVA)—trade name ''BioThrax''—was licensed in 1970 by the U.S. National Institutes of Health

The National Institutes of Health, commonly referred to as NIH (with each letter pronounced individually), is the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and public health research. It was founded in the late ...

(NIH) and in 1972 the Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respon ...

(FDA) took over responsibility for vaccine licensure and oversight. AVA is produced from culture filtrates of an avirulent, nonencapsulated mutant of the ''B. anthracis'' Vollum strain known as V770-NP1-R.BioThrax Package Insert/ref> No living organisms are present in the vaccine which results in protective immunity after 3 to 6 doses. AVA remains the only FDA-licensed human anthrax vaccine in the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and is produced by Emergent BioSolutions

Emergent BioSolutions Inc. is an American multinational specialty biopharmaceutical company headquartered in Gaithersburg, Maryland. It develops vaccines and antibody therapeutics for infectious diseases and opioid overdoses, and it provides me ...

, formerly known as BioPort Corporation in Lansing

Lansing () is the capital of the U.S. state of Michigan. It is mostly in Ingham County, although portions of the city extend west into Eaton County and north into Clinton County. The 2020 census placed the city's population at 112,644, makin ...

, Michigan. The principal purchasers of the vaccine in the United States are the Department of Defense Department of Defence or Department of Defense may refer to:

Current departments of defence

* Department of Defence (Australia)

* Department of National Defence (Canada)

* Department of Defence (Ireland)

* Department of National Defense (Philippin ...

and Department of Health and Human Services

The United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is a cabinet-level executive branch department of the U.S. federal government created to protect the health of all Americans and providing essential human services. Its motto is " ...

. Ten million doses of AVA have been purchased for the U.S. Strategic National Stockpile

The Strategic National Stockpile (SNS), originally called the National Pharmaceutical Stockpile (NPS), is the United States' national repository of antibiotics, vaccines, chemical antidotes, antitoxins, and other critical medical supplies. Its w ...

for use in the event of a mass bioterrorist

Bioterrorism is terrorism involving the intentional release or dissemination of biological agents. These agents are bacteria, viruses, insects, fungi, and/or toxins, and may be in a naturally occurring or a human-modified form, in much the same ...

anthrax attack.

In 1997, the Clinton administration initiated the Anthrax Vaccine Immunization Program (AVIP), under which active U.S. service personnel were to be immunized with the vaccine. Controversy ensued since vaccination was mandatory and GAO

Gao , or Gawgaw/Kawkaw, is a city in Mali and the capital of the Gao Region. The city is located on the River Niger, east-southeast of Timbuktu on the left bank at the junction with the Tilemsi valley.

For much of its history Gao was an impor ...

published reports that questioned the safety and efficacy of AVA, causing sometimes serious side effects. A Congressional report also questioned the safety and efficacy of the vaccine and challenged the legality of mandatory inoculations. Mandatory vaccinations were halted in 2004 by a formal legal injunction which made numerous substantive challenges regarding the vaccine and its safety. After reviewing extensive scientific evidence, the FDA determined in 2005 that AVA is safe and effective as licensed for the prevention of anthrax, regardless of the route of exposure. In 2006, the Defense Department announced the reinstatement of mandatory anthrax vaccinations for more than 200,000 troops and defense contractors. The vaccinations are required for most U.S. military units and civilian contractors assigned to homeland bioterrorism

Bioterrorism is terrorism involving the intentional release or dissemination of biological agents. These agents are bacteria, viruses, insects, fungi, and/or toxins, and may be in a naturally occurring or a human-modified form, in much the same ...

defense or deployed in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

or South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

.

Investigational anthrax vaccines

A number of experimental anthrax vaccines are undergoing pre-clinical testing, notably the ''Bacillus anthracis'' protective antigen—known as PA (see

A number of experimental anthrax vaccines are undergoing pre-clinical testing, notably the ''Bacillus anthracis'' protective antigen—known as PA (see Anthrax toxin

Anthrax toxin is a three-protein exotoxin secreted by virulent strains of the bacterium, ''Bacillus anthracis''—the causative agent of anthrax. The toxin was first discovered by Harry Smith in 1954. Anthrax toxin is composed of a cell-binding ...

—combined with various adjuvant In pharmacology, an adjuvant is a drug or other substance, or a combination of substances, that is used to increase the efficacy or potency of certain drugs. Specifically, the term can refer to:

* Adjuvant therapy in cancer management

* Analgesic ...

s such as aluminum hydroxide

Aluminium hydroxide, Al(OH)3, is found in nature as the mineral gibbsite (also known as hydrargillite) and its three much rarer polymorphs: bayerite, doyleite, and nordstrandite. Aluminium hydroxide is amphoteric, i.e., it has both basic and ...

(Alhydrogel), saponin

Saponins (Latin "sapon", soap + "-in", one of), also selectively referred to as triterpene glycosides, are bitter-tasting usually toxic plant-derived organic chemicals that have a foamy quality when agitated in water. They are widely distributed ...

QS-21, and monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) in squalene

Squalene is an organic compound. It is a triterpenoid with the formula C30H50. It is a colourless oil, although impure samples appear yellow. It was originally obtained from shark liver oil (hence its name, as ''Squalus'' is a genus of sharks). A ...

/lecithin

Lecithin (, from the Greek ''lekithos'' "yolk") is a generic term to designate any group of yellow-brownish fatty substances occurring in animal and plant tissues which are amphiphilic – they attract both water and fatty substances (and so ar ...

/Tween 80

Preadolescence is a stage of human development following middle childhood and preceding adolescence.New Oxford American Dictionary. 2nd Edition. 2005. Oxford University Press. It commonly ends with the beginning of puberty. Preadolescence is ...

emulsion (SLT). One dose of each formulation has provided significant protection (> 90%) against inhalational anthrax in rhesus macaque

The rhesus macaque (''Macaca mulatta''), colloquially rhesus monkey, is a species of Old World monkey. There are between six and nine recognised subspecies that are split between two groups, the Chinese-derived and the Indian-derived. Generally b ...

s.

*Omer-2 trial: Beginning in 1998 and running for eight years, a secret Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

i project known as ''Omer-2'' tested an Israeli investigational anthrax vaccine on 716 volunteers of the Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

. The vaccine—given under a seven-dose schedule—was developed by the Nes Tziona Biological Institute. A group of study volunteers complained of multi-symptom illnesses allegedly associated with the vaccine and petitioned for disability benefits to the Defense Ministry

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

, but were denied. In February 2009, a petition from the volunteers to disclose a report about ''Omer-2'' was filed with the Israel's High Court against the Defense Ministry, the Israel Institute for Biological Research Israel Institute for Biological Research (IIBR) is an Israeli research and development laboratory It is under the jurisdiction of the Prime Minister's Office that works in close cooperation with Israeli government agencies. IIBR has many public p ...

at Nes Tziona, the director, Avigdor Shafferman, and the IDF Medical Corps. Release of the information was requested to support further action to provide disability compensation for the volunteers. In 2014 it was announced that the Israeli government would pay $6 million compensation to the 716 soldiers who participated in the Omer-2 trial.

*In 2012, ''B. anthracis'' isolate H9401 was obtained from a Korean patient with gastrointestinal anthrax. The goal of the Republic of Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and sharing a land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its east ...

is to use this strain as a challenge strain to develop a recombinant vaccine against anthrax.

References

Further reading

* * * Turnbull, P.C.B. (1991), "Anthrax Vaccines: Past, Present, and Future", ''Vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifie ...

'', 533–9.

{{Vaccines

Anthrax

Animal vaccines

Biological warfare

Vaccines

Soviet inventions

Military medicine in the Soviet Union