Suffragette Arrest, London, 1914 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

TV series ''

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the  Women had won the right to vote in several countries by the end of the 19th century; in 1893, New Zealand became the first self-governing country to grant the vote to all women over the age of 21. When by 1903 women in Britain had not been enfranchised, Pankhurst decided that women had to "do the work ourselves"; the WSPU motto became "deeds, not words". The suffragettes heckled politicians, tried to storm parliament, were attacked and sexually assaulted during battles with the police, chained themselves to railings, smashed windows, carried out a nationwide bombing and arson campaign, and faced anger and ridicule in the media. When imprisoned they went on

Women had won the right to vote in several countries by the end of the 19th century; in 1893, New Zealand became the first self-governing country to grant the vote to all women over the age of 21. When by 1903 women in Britain had not been enfranchised, Pankhurst decided that women had to "do the work ourselves"; the WSPU motto became "deeds, not words". The suffragettes heckled politicians, tried to storm parliament, were attacked and sexually assaulted during battles with the police, chained themselves to railings, smashed windows, carried out a nationwide bombing and arson campaign, and faced anger and ridicule in the media. When imprisoned they went on

History of Woman Suffrage, volume 6

' (

In Manchester, the Women's Suffrage Committee had been formed in 1867 to work with the

In Manchester, the Women's Suffrage Committee had been formed in 1867 to work with the

At a political meeting in Manchester in 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and millworker,

At a political meeting in Manchester in 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and millworker,  1912 was a turning point for the suffragettes, as they turned to using more militant tactics and began a window-smashing campaign. Some members of the WSPU, including Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and her husband Frederick, disagreed with this strategy but Christabel Pankhurst ignored their objections. In response to this, the Government ordered the arrest of the WSPU leaders and, although Christabel Pankhurst escaped to France, the Pethick-Lawrences were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months' imprisonment. On their release, the Pethick-Lawrences began to speak out publicly against the window-smashing campaign, arguing that it would lose support for the cause, and eventually they were expelled from the WSPU. Having lost control of ''Votes for Women'' the WSPU began to publish their own newspaper under the title ''The Suffragette''.

The campaign was then escalated, with the suffragettes chaining themselves to railings, setting fire to post box contents, smashing windows and eventually detonating bombs, as part of a wider

1912 was a turning point for the suffragettes, as they turned to using more militant tactics and began a window-smashing campaign. Some members of the WSPU, including Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and her husband Frederick, disagreed with this strategy but Christabel Pankhurst ignored their objections. In response to this, the Government ordered the arrest of the WSPU leaders and, although Christabel Pankhurst escaped to France, the Pethick-Lawrences were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months' imprisonment. On their release, the Pethick-Lawrences began to speak out publicly against the window-smashing campaign, arguing that it would lose support for the cause, and eventually they were expelled from the WSPU. Having lost control of ''Votes for Women'' the WSPU began to publish their own newspaper under the title ''The Suffragette''.

The campaign was then escalated, with the suffragettes chaining themselves to railings, setting fire to post box contents, smashing windows and eventually detonating bombs, as part of a wider

Suffragettes were not recognised as

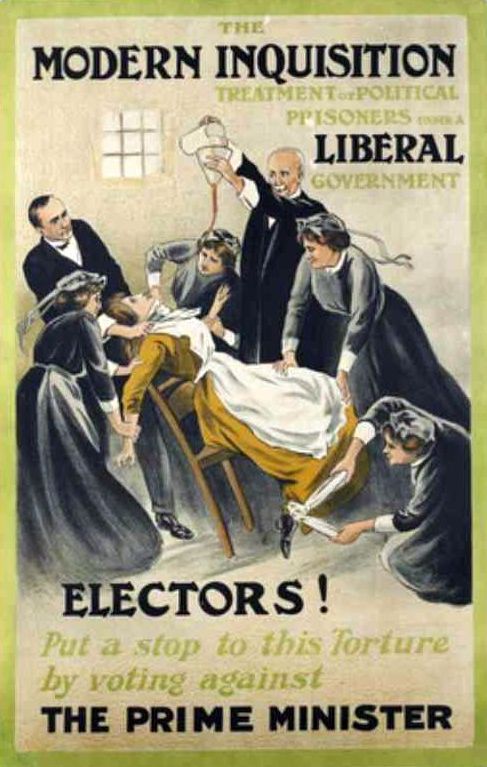

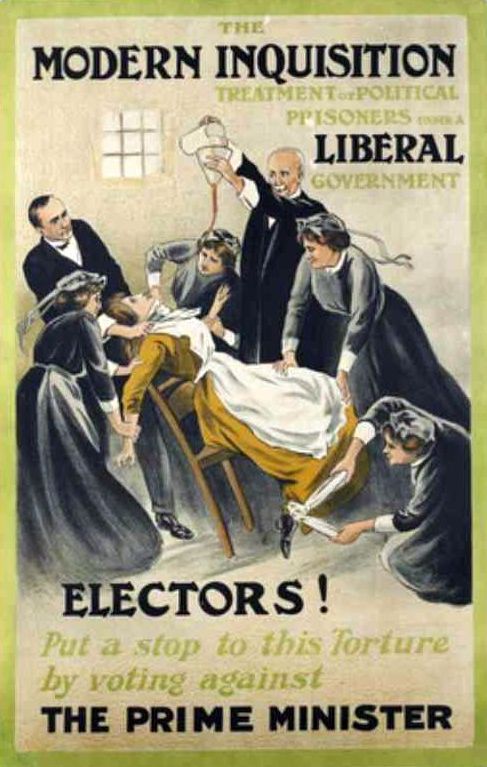

Suffragettes were not recognised as  Militant suffragette demonstrations subsequently became more aggressive, and the British Government took action. Unwilling to release all the suffragettes refusing food in prison, in the autumn of 1909, the authorities began to adopt more drastic measures to manage the hunger-strikers. In September 1909, the Home Office became unwilling to release hunger-striking suffragettes before their sentence was served. Suffragettes became a liability because, if they were to die in custody, the prison would be responsible for their death. Prisons began the practice of

Militant suffragette demonstrations subsequently became more aggressive, and the British Government took action. Unwilling to release all the suffragettes refusing food in prison, in the autumn of 1909, the authorities began to adopt more drastic measures to manage the hunger-strikers. In September 1909, the Home Office became unwilling to release hunger-striking suffragettes before their sentence was served. Suffragettes became a liability because, if they were to die in custody, the prison would be responsible for their death. Prisons began the practice of  The process of tube-feeding was strenuous without the consent of the hunger strikers, who were typically strapped down and force-fed via stomach or nostril tube, often with a considerable amount of force. The process was painful, and after the practice was observed and studied by several physicians, it was deemed to cause both short-term damage to the

The process of tube-feeding was strenuous without the consent of the hunger strikers, who were typically strapped down and force-fed via stomach or nostril tube, often with a considerable amount of force. The process was painful, and after the practice was observed and studied by several physicians, it was deemed to cause both short-term damage to the

In April 1913,

In April 1913,

Prominent British-Indian suffragette

Prominent British-Indian suffragette

In the autumn of 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst had sailed to the US to embark on a lecture tour to publicise the message of the WSPU and to raise money for the treatment of her son, Harry, who was gravely ill. By this time the suffragettes' tactics of civil disorder were being used by American militants

In the autumn of 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst had sailed to the US to embark on a lecture tour to publicise the message of the WSPU and to raise money for the treatment of her son, Harry, who was gravely ill. By this time the suffragettes' tactics of civil disorder were being used by American militants  After Emmeline Pankhurst's death in 1928, money was raised to commission a statue, and on 6 March 1930 the statue in

After Emmeline Pankhurst's death in 1928, money was raised to commission a statue, and on 6 March 1930 the statue in

series about the suffragettes, United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

. The term refers in particular to members of the British Women's Social and Political Union

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom from 1903 to 1918. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and ...

(WSPU), a women-only movement founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst ('' née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Impo ...

, which engaged in direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

and civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". Hen ...

. In 1906, a reporter writing in the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' coined the term ''suffragette'' for the WSPU, derived from suffragist

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

(any person advocating for voting rights), in order to belittle the women advocating women's suffrage. The militants embraced the new name, even adopting

Adoption is a process whereby a person assumes the parenting of another, usually a child, from that person's biological or legal parent or parents. Legal adoptions permanently transfer all rights and responsibilities, along with filiation, from ...

it for use as the title of the newspaper published by the WSPU.

hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

, to which the government responded by force-feeding

Force-feeding is the practice of feeding a human or animal against their will. The term ''gavage'' (, , ) refers to supplying a substance by means of a small plastic feeding tube passed through the nose ( nasogastric) or mouth (orogastric) into ...

them. The first suffragette to be force fed was Evaline Hilda Burkitt

Evaline Hilda Burkitt (19 July 1876 – 7 March 1955) was a British suffragette and member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). A militant activist for women's rights, she went on hunger strike in prison and was the first suffra ...

. The death of one suffragette, Emily Davison

Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was an English suffragette who fought for Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom, votes for women in Britain in the early twentieth century. A member of the Women's Social and Polit ...

, when she ran in front of the king's horse at the 1913 Epsom Derby

The 1913 Epsom Derby, sometimes referred to as “The Suffragette Derby”, was a horse race which took place at Epsom Downs on 4 June 1913. It was the 134th running of the Derby. The race was won, controversially, by Aboyeur at record 100–1 ...

, made headlines around the world. The WSPU campaign had varying levels of support from within the suffragette movement; breakaway groups formed, and within the WSPU itself not all members supported the direct action.

The suffragette campaign was suspended when World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

broke out in 1914. After the war, the Representation of the People Act 1918 gave the vote to women over the age of 30 who met certain property qualifications. Ten years later, women gained electoral equality with men when the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928

The Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. This act expanded on the Representation of the People Act 1918 which had given some women the vote in Parliamentary elections for the ...

gave all women the right to vote at age 21.

Background

Women's suffrage

Although theIsle of Man

)

, anthem = "O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe ...

(a British Crown dependency) had enfranchised women who owned property to vote in parliamentary (Tynwald) elections in 1881, New Zealand was the first self-governing country to grant all women the right to vote in 1893, when women over the age of 21 were permitted to vote in all parliamentary elections. Harper, Ida Husted. History of Woman Suffrage, volume 6

' (

National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National ...

, 1922) p. 752. Women in South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

achieved the same right and became the first to obtain the right to stand for parliament in 1895. In the United States, white women over the age of 21 were allowed to vote in the western territories of Wyoming from 1869 and in Utah from 1870.

British suffragettes

In 1865John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

was elected to Parliament on a platform that included votes for women, and in 1869 he published his essay in favour of equality of the sexes ''The Subjection of Women

''The Subjection of Women'' is an essay by English philosopher, political economist and civil servant John Stuart Mill published in 1869, with ideas he developed jointly with his wife Harriet Taylor Mill. Mill submitted the finished manuscript ...

''. Also in 1865, a women's discussion group, The Kensington Society, was formed. Following discussions on the subject of women's suffrage, the society formed a committee to draft a petition and gather signatures, which Mill agreed to present to Parliament once they had gathered 100 signatures. In October 1866, amateur scientist Lydia Becker

Lydia Ernestine Becker (24 February 1827 – 18 July 1890) was a leader in the early British suffrage movement, as well as an amateur scientist with interests in biology and astronomy. She established Manchester as a centre for the suffrage mo ...

attended a meeting of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science

The National Association for the Promotion of Social Science (NAPSS), often known as the Social Science Association, was a British reformist group founded in 1857 by Lord Brougham. It pursued issues in public health, industrial relations, penal r ...

held in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

and heard one of the organisors of the petition, Barbara Bodichon, read a paper entitled ''Reasons for the Enfranchisement of Women''. Becker was inspired to help gather signatures around Manchester and to join the newly formed Manchester committee. Mill presented the petition to Parliament in 1866, by which time the supporters had gathered 1499 signatures, including those of Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English Reform movement, social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during t ...

, Harriet Martineau

Harriet Martineau (; 12 June 1802 – 27 June 1876) was an English social theorist often seen as the first female sociologist, focusing on racism, race relations within much of her published material.Michael R. Hill (2002''Harriet Martineau: Th ...

, Josephine Butler

Josephine Elizabeth Butler (' Grey; 13 April 1828 – 30 December 1906) was an English feminist and social reformer in the Victorian era. She campaigned for women's suffrage, the right of women to better education, the end of coverture ...

and Mary Somerville.

In March 1867, Becker wrote an article for the ''Contemporary Review'', in which she said:

Two further petitions were presented to parliament in May 1867 and Mill also proposed an amendment to the 1867 Reform Act to give women the same political rights as men, but the amendment was treated with derision and defeated by 196 votes to 73.

The Manchester Society for Women's suffrage was formed in January 1867, when Jacob Bright

The Rt Hon. Jacob Bright (26 May 1821 – 7 November 1899) was a British Liberal politician serving as Mayor of Rochdale and later Member of Parliament for Manchester.

Background

Bright was born at Green Bank near Rochdale, Lancashire. He was ...

, Rev. S. A. Steinthal, Mrs. Gloyne, Max Kyllman and Elizabeth Wolstenholme

Elizabeth Clarke Wolstenholme-Elmy (died 12 March 1918) was a life-long campaigner and organiser, significant in the history of women's suffrage in the United Kingdom. She wrote essays and some poetry, using the pseudonyms E and Ignota.

Early ...

met at the house of Dr. Louis Borchardt. Lydia Becker

Lydia Ernestine Becker (24 February 1827 – 18 July 1890) was a leader in the early British suffrage movement, as well as an amateur scientist with interests in biology and astronomy. She established Manchester as a centre for the suffrage mo ...

was made Secretary of the Society in February 1867 and Dr. Richard Pankhurst was one of the earliest members of the Executive Committee. An 1874 speaking event in Manchester organised by Becker, was attended by 14-year-old Emmeline Goulden, who was to become an ardent campaigner for women's rights, and later married Dr Pankhurst becoming known as Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst ('' née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Impo ...

.

During the summer of 1880, Becker visited the Isle of Man to address five public meetings on the subject of women's suffrage to audiences mainly composed of women. These speeches instilled in the Manx women a determination to secure the franchise, and on 31 January 1881, women on the island who owned property in their own right were given the vote.

Formation of the WSPU

In Manchester, the Women's Suffrage Committee had been formed in 1867 to work with the

In Manchester, the Women's Suffrage Committee had been formed in 1867 to work with the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

(ILP) to secure votes for women, but, although the local ILP were very supportive, nationally the party were more interested in securing the franchise for working-class men and refused to make women's suffrage a priority. In 1897, the Manchester Women's Suffrage committee had merged with the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies

The National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), also known as the ''suffragists'' (not to be confused with the suffragettes) was an organisation founded in 1897 of women's suffrage societies around the United Kingdom. In 1919 it was ren ...

(NUWSS) but Emmeline Pankhurst, who was a member of the original Manchester committee, and her eldest daughter Christabel had become impatient with the ILP, and on 10 October 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst held a meeting at her home in Manchester to form a breakaway group, the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). From the outset, the WSPU was determined to move away from the staid campaign methods of NUWSS and instead take more positive action:

The term "suffragette" was first used in 1906 as a term of derision by the journalist Charles E. Hands in the London ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' to describe activists in the movement for women's suffrage, in particular members of the WSPU.. But the women he intended to ridicule embraced the term, saying "suffraGETtes" (hardening the 'g'), implying not only that they wanted the vote, but that they intended to 'get' it. The non-militant suffragists found favour in the press, as they were not hoping to get the franchise through 'violence, crime, arson and open rebellion'.

WSPU campaigns

At a political meeting in Manchester in 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and millworker,

At a political meeting in Manchester in 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and millworker, Annie Kenney

Ann "Annie" Kenney (13 September 1879 – 9 July 1953) was an English working-class suffragette and socialist feminist who became a leading figure in the Women's Social and Political Union. She co-founded its first branch in London with Minnie ...

, disrupted speeches by prominent Liberals Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

and Sir Edward Grey

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon, (25 April 1862 – 7 September 1933), better known as Sir Edward Grey, was a British Liberal statesman and the main force behind British foreign policy in the era of the First World War.

An adhe ...

, asking where Churchill and Grey stood with regards to women's political rights. At a time when political meetings were only attended by men and speakers were expected to be given the courtesy of expounding their views without interruption, the audience were outraged, and when the women unfurled a "Votes for Women" banner they were both arrested for a technical assault on a policeman. When Pankhurst and Kenney appeared in court they both refused to pay the fine imposed, preferring to go to prison to gain publicity for their cause.

In July 1908 the WSPU hosted a large demonstration in Heaton Park

Heaton Park is a public park in Manchester, England, covering an area of over . The park includes the grounds of a Grade I listed, neoclassical 18th century country house, Heaton Hall. The hall, remodelled by James Wyatt in 1772, is now only ...

, near Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

with speakers on 13 separate platforms including Emmeline, Christabel and Adela Pankhurst. According to the ''Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'':

Stung by the stereotypical image of the strong minded woman in masculine clothes created by newspaper cartoonists, the suffragettes resolved to present a fashionable, feminine image when appearing in public. In 1908 the co-editor of the WSPU's ''Votes for Women'' newspaper, Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Baroness Pethick-Lawrence (; 21 October 1867 – 11 March 1954) was a British women's rights activist and suffragette.

Early life

Pethick-Lawrence was born in Bristol as Emmeline Pethick. Her father, Henry Pethick, w ...

, designed the suffragettes' colour scheme of purple for loyalty and dignity, white for purity, and green for hope. Fashionable London shops Selfridges

Selfridges, also known as Selfridges & Co., is a chain of high-end department stores in the United Kingdom that is operated by Selfridges Retail Limited, part of the Selfridges Group of department stores. It was founded by Harry Gordon Selfridg ...

and Liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

sold tricolour-striped ribbon for hats, rosettes, badges and belts, as well as coloured garments, underwear, handbags, shoes, slippers and toilet soap. As membership of the WSPU grew it became fashionable for women to identify with the cause by wearing the colours, often discreetly in a small piece of jewellery or by carrying a heart-shaped vesta case

A vesta case, or simply a vesta, is a small box made to house wax, or "strike anywhere", matches. The first successful friction match appeared in 1826, and in 1832 William Newton patented the "wax vesta" in England. It consisted of a wax stem with ...

and in December 1908 the London jewellers, Mappin & Webb

Mappin & Webb (M&W) is an international jewellery company headquartered in England. Mappin & Webb traces its origins to a silver workshop founded in Sheffield . It now has retail stores throughout the UK.

Mappin & Webb has held Royal Warrants ...

, issued a catalogue of suffragette jewellery in time for the Christmas season. Sylvia Pankhurst

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst (5 May 1882 – 27 September 1960) was a campaigning English feminist and socialist. Committed to organising working-class women in London's East End, and unwilling in 1914 to enter into a wartime political truce with t ...

said at the time: "Many suffragists spend more money on clothes than they can comfortably afford, rather than run the risk of being considered outré, and doing harm to the cause". In 1909 the WSPU presented specially commissioned pieces of jewellery to leading suffragettes, Emmeline Pankhurst and Louise Eates.

The suffragettes also used other methods to publicise and raise money for the cause and from 1909, the "Pank-a-Squith

''Pank-a-Squith'' was a political board game about the suffragette movement created around 1909. It was created for the British Women's Social and Political Union as a way to generate funds and help spread women's suffrage ideologies.

History

' ...

" board game was sold by the WSPU. The name was derived from Pankhurst and the surname of Prime Minister H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

, who was largely hated by the movement. The board game was set out in a spiral, and players were required to lead their suffragette figure from their home to parliament, past the obstacles faced from Prime Minister H. H. Asquith and the Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

government. Also in 1909, suffragettes Daisy Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

and Elspeth McClelland tried an innovative method of potentially obtaining a meeting with Asquith by sending themselves by Royal Mail courier post; however, Downing Street

Downing Street is a street in Westminster in London that houses the official residences and offices of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Situated off Whitehall, it is long, and a few minutes' walk ...

did not accept the parcel.

1912 was a turning point for the suffragettes, as they turned to using more militant tactics and began a window-smashing campaign. Some members of the WSPU, including Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and her husband Frederick, disagreed with this strategy but Christabel Pankhurst ignored their objections. In response to this, the Government ordered the arrest of the WSPU leaders and, although Christabel Pankhurst escaped to France, the Pethick-Lawrences were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months' imprisonment. On their release, the Pethick-Lawrences began to speak out publicly against the window-smashing campaign, arguing that it would lose support for the cause, and eventually they were expelled from the WSPU. Having lost control of ''Votes for Women'' the WSPU began to publish their own newspaper under the title ''The Suffragette''.

The campaign was then escalated, with the suffragettes chaining themselves to railings, setting fire to post box contents, smashing windows and eventually detonating bombs, as part of a wider

1912 was a turning point for the suffragettes, as they turned to using more militant tactics and began a window-smashing campaign. Some members of the WSPU, including Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence and her husband Frederick, disagreed with this strategy but Christabel Pankhurst ignored their objections. In response to this, the Government ordered the arrest of the WSPU leaders and, although Christabel Pankhurst escaped to France, the Pethick-Lawrences were arrested, tried and sentenced to nine months' imprisonment. On their release, the Pethick-Lawrences began to speak out publicly against the window-smashing campaign, arguing that it would lose support for the cause, and eventually they were expelled from the WSPU. Having lost control of ''Votes for Women'' the WSPU began to publish their own newspaper under the title ''The Suffragette''.

The campaign was then escalated, with the suffragettes chaining themselves to railings, setting fire to post box contents, smashing windows and eventually detonating bombs, as part of a wider bombing campaign

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechanic ...

. Some radical techniques used by the suffragettes were learned from Russian exiles from tsarism

Tsarist autocracy (russian: царское самодержавие, transcr. ''tsarskoye samoderzhaviye''), also called Tsarism, was a form of autocracy (later absolute monarchy) specific to the Grand Duchy of Moscow and its successor states th ...

who had escaped to England.. In 1914, at least seven churches were bombed or set on fire across the United Kingdom, including Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, where an explosion aimed at destroying the 700-year-old Coronation Chair

The Coronation Chair, known historically as St Edward's Chair or King Edward's Chair, is an ancient wooden chair on which British monarchs sit when they are invested with regalia and crowned at their coronations. It was commissioned in 1296 by ...

, only caused minor damage. Places that wealthy people, typically men, frequented were also burnt and destroyed whilst left unattended so that there was little risk to life, including cricket pavilions, horse-racing pavilions, churches, castles and the second homes of the wealthy. They also burnt the slogan "Votes for Women" into the grass of golf courses. Pinfold Manor in Surrey, which was being built for the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

, was targeted with two bombs on 19 February 1913, only one of which exploded, causing significant damage; in her memoirs, Sylvia Pankhurst said that Emily Davison

Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was an English suffragette who fought for Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom, votes for women in Britain in the early twentieth century. A member of the Women's Social and Polit ...

had carried out the attack. There were 250 arson or destruction attacks in a six-month period in 1913 and in April the newspapers reported "What might have been the most serious outrage yet perpetrated by the Suffragettes":

There are reports in the Parliamentary Papers which include lists of the 'incendiary devices', explosions, artwork destruction (including an axe attack upon a painting of The Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister of ...

in the National Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current Director o ...

), arson attacks, window-breaking, postbox burning and telegraph cable cutting, that took place during the most militant years, from 1910 to 1914. Both suffragettes and police spoke of a "Reign of Terror"; newspaper headlines referred to "Suffragette Terrorism".

One suffragette, Emily Davison

Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was an English suffragette who fought for Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom, votes for women in Britain in the early twentieth century. A member of the Women's Social and Polit ...

, died under the King's horse, Anmer, at The Derby on 4 June 1913. It is debated whether she was trying to pull down the horse, attach a suffragette scarf or banner to it, or commit suicide to become a martyr to the cause. However, recent analysis of the film of the event suggests that she was merely trying to attach a scarf to the horse, and the suicide theory seems unlikely as she was carrying a return train ticket from Epsom and had holiday plans with her sister in the near future.

Imprisonment

In the early 20th century until the outbreak ofWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, approximately one thousand suffragettes were imprisoned in Britain.. Most early incarcerations were for public order offences and failure to pay outstanding fines. While incarcerated, suffragettes lobbied to be considered political prisoners; with such a designation, suffragettes would be placed in the First Division as opposed to the Second or Third Division of the prison system, and as political prisoners would be granted certain freedoms and liberties not allotted to other prison divisions, such as being allowed frequent visits and being allowed to write books or articles. Because of a lack of consistency between the different courts, suffragettes would not necessarily be placed in the First Division and could be placed in the Second or Third Division, which enjoyed fewer liberties.

This cause was taken up by the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), a large organisation in Britain, that lobbied for women's suffrage led by militant suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst.. The WSPU campaigned to get imprisoned suffragettes recognised as political prisoners. However, this campaign was largely unsuccessful. Citing a fear that the suffragettes becoming political prisoners would make for easy martyrdom,. and with thoughts from the courts and the Home Office that they were abusing the freedoms of the First Division to further the agenda of the WSPU,. suffragettes were placed in the Second Division, and in some cases the Third Division, in prisons, with no special privileges granted to them as a result.

Hunger strikes and force-feeding

Suffragettes were not recognised as

Suffragettes were not recognised as political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although n ...

s, and many of them staged hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

s while they were imprisoned. The first woman to refuse food was Marion Wallace Dunlop

Marion Wallace Dunlop (22 December 1864 – 12 September 1942) was a Scottish artist and author. She was the first and one of the most well known British suffragettes to go on hunger strike, on 5 July 1909, after being arrested in July 1909 fo ...

, a militant suffragette who was sentenced to a month in Holloway for vandalism in July 1909. Without consulting suffragette leaders such as Pankhurst,. Dunlop refused food in protest at being denied political prisoner status. After a 92-hour hunger strike, and for fear of her becoming a martyr, the Home Secretary Herbert Gladstone

Herbert John Gladstone, 1st Viscount Gladstone, (7 January 1854 – 6 March 1930) was a British Liberal politician. The youngest son of William Ewart Gladstone, he was Home Secretary from 1905 to 1910 and Governor-General of the Union of South ...

decided to release her early on medical grounds. Dunlop's strategy was adopted by other suffragettes who were incarcerated.. It became common practice for suffragettes to refuse food in protest for not being designated as political prisoners, and as a result they would be released after a few days and could return to the "fighting line"..

After a public backlash regarding the prison status of suffragettes, the rules of the divisions were amended. In March 1910, Rule 243A was introduced by the Home Secretary Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, allowing prisoners in the Second and Third Divisions to be allowed certain privileges of the First Division, provided they were not convicted of a serious offence, effectively ending hunger strikes for two years.. Hunger strikes began again when Pankhurst was transferred from the Second Division to the First Division, inciting the other suffragettes to demonstrate regarding their prison status..

Militant suffragette demonstrations subsequently became more aggressive, and the British Government took action. Unwilling to release all the suffragettes refusing food in prison, in the autumn of 1909, the authorities began to adopt more drastic measures to manage the hunger-strikers. In September 1909, the Home Office became unwilling to release hunger-striking suffragettes before their sentence was served. Suffragettes became a liability because, if they were to die in custody, the prison would be responsible for their death. Prisons began the practice of

Militant suffragette demonstrations subsequently became more aggressive, and the British Government took action. Unwilling to release all the suffragettes refusing food in prison, in the autumn of 1909, the authorities began to adopt more drastic measures to manage the hunger-strikers. In September 1909, the Home Office became unwilling to release hunger-striking suffragettes before their sentence was served. Suffragettes became a liability because, if they were to die in custody, the prison would be responsible for their death. Prisons began the practice of force-feeding

Force-feeding is the practice of feeding a human or animal against their will. The term ''gavage'' (, , ) refers to supplying a substance by means of a small plastic feeding tube passed through the nose ( nasogastric) or mouth (orogastric) into ...

the hunger strikers through a tube, most commonly via a nostril

A nostril (or naris , plural ''nares'' ) is either of the two orifices of the nose. They enable the entry and exit of air and other gasses through the nasal cavities. In birds and mammals, they contain branched bones or cartilages called turbi ...

or stomach tube or a stomach pump. Force-feeding had previously been practised in Britain but its use had been exclusively for patients in hospitals who were too unwell to eat or swallow food. Despite the practice being deemed safe by medical practitioners for sick patients, it posed health issues for the healthy suffragettes.

The process of tube-feeding was strenuous without the consent of the hunger strikers, who were typically strapped down and force-fed via stomach or nostril tube, often with a considerable amount of force. The process was painful, and after the practice was observed and studied by several physicians, it was deemed to cause both short-term damage to the

The process of tube-feeding was strenuous without the consent of the hunger strikers, who were typically strapped down and force-fed via stomach or nostril tube, often with a considerable amount of force. The process was painful, and after the practice was observed and studied by several physicians, it was deemed to cause both short-term damage to the circulatory system

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

, digestive system

The human digestive system consists of the gastrointestinal tract plus the accessory organs of digestion (the tongue, salivary glands, pancreas, liver, and gallbladder). Digestion involves the breakdown of food into smaller and smaller compone ...

and nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes th ...

and long-term damage to the physical and mental health of the suffragettes. Some suffragettes who were force-fed developed pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant dull ache. Other sy ...

or pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

as a result of a misplaced tube.. Women who had gone on hunger strike in prison received a Hunger Strike Medal

The Hunger Strike Medal was a silver medal awarded between August 1909 and 1914 to suffragette prisoners by the leadership of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). During their imprisonment, they went on hunger strike while serving th ...

from the WSPU on their release.

Legislation

In April 1913,

In April 1913, Reginald McKenna

Reginald McKenna (6 July 1863 – 6 September 1943) was a British banker and Liberal politician. His first Cabinet post under Henry Campbell-Bannerman was as President of the Board of Education, after which he served as First Lord of the Admiral ...

of the Home Office passed the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913

The Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act, commonly referred to as the Cat and Mouse Act, was an Act of Parliament passed in Britain under H. H. Asquith's Liberal government in 1913. Some members of the Women's Social and Political U ...

, or the Cat and Mouse Act as it was commonly known. The act made the hunger strikes legal, in that a suffragette would be temporarily released from prison when their health began to diminish, only to be readmitted when she regained her health to finish her sentence. The act enabled the British Government to be absolved of any blame resulting from death or harm due to the self-starvation of the striker and ensured that the suffragettes would be too ill and too weak to participate in demonstrative activities while not in custody. Most women continued hunger striking when they were readmitted to prison following their leave.. After the Act was introduced, force-feeding on a large scale was stopped and only women convicted of more serious crimes and considered likely to repeat their offences if released were force-fed..

The Bodyguard

In early 1913 and in response to the Cat and Mouse Act, the WSPU instituted a secret society of women known as the "Bodyguard" whose role was to physically protect Emmeline Pankhurst and other prominent suffragettes from arrest and assault. Known members included Katherine Willoughby Marshall,Leonora Cohen

Leonora Cohen (; 15 June 1873 – 4 September 1978) was a British suffragette and trade unionist, and one of the first female magistrates. She was known as the "Tower Suffragette" after smashing a display case in the Tower of London and acted ...

and Gertrude Harding; Edith Margaret Garrud

Edith Margaret Garrud (''née'' Williams; 1872–1971) was a British martial artist, suffragist and playwright. She was the first British female teacher of jujutsu and one of the first female martial arts instructors in the western world.

...

was their jujitsu trainer.

The origin of the "Bodyguard" can be traced to a WSPU meeting at which Garrud spoke. As suffragettes speaking in public increasingly found themselves the target of violence and attempted assaults, learning jujitsu was a way for women to defend themselves against angry hecklers. Inciting incidents included Black Friday, during which a deputation of 300 suffragettes were physically prevented by police from entering the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, sparking a near-riot and allegations of both common and sexual assault.

Members of the "Bodyguard" orchestrated the "escapes" of a number of fugitive suffragettes from police surveillance during 1913 and early 1914. They also participated in several violent actions against the police in defence of their leaders, notably including the "Battle of Glasgow" on 9 March 1914, when a group of about 30 Bodyguards brawled with about 50 police constables and detectives on the stage of St Andrew's Hall in Glasgow. The fight was witnessed by an audience of some 4500 people.

World War I

At the commencement of World War I, the suffragette movement in Britain moved away from suffrage activities and focused on the war effort, and as a result, hunger strikes largely stopped. In August 1914, the British Government released all prisoners who had been incarcerated for suffrage activities on an amnesty,. with Pankhurst ending all militant suffrage activities soon after.. The suffragettes' focus on war work turned public opinion in favour of their eventual partial enfranchisement in 1918.Women eagerly volunteered to take on many traditional male roles – leading to a new view of what women were capable of. The war also caused a split in the British suffragette movement; the mainstream, represented by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst's WSPU calling a ceasefire in their campaign for the duration of the war, while moreradical Radical may refer to: Politics and ideology Politics *Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change *Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...suffragettes, represented bySylvia Pankhurst Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst (5 May 1882 – 27 September 1960) was a campaigning English feminist and socialist. Committed to organising working-class women in London's East End, and unwilling in 1914 to enter into a wartime political truce with t ...'s Women's Suffrage Federation continued the struggle.

Prominent British-Indian suffragette

Prominent British-Indian suffragette Sophia Duleep Singh

Princess Sophia Alexandrovna Duleep Singh (8 August 1876 – 22 August 1948) was a prominent suffragette in the United Kingdom. Her father was Maharaja Sir Duleep Singh, who had been taken from his kingdom of Punjab to the British Raj, a ...

, the third daughter of the exiled Sikh Maharajah Duleep Singh

Maharaja Sir Duleep Singh, GCSI (4 September 1838 – 22 October 1893), or Sir Dalip Singh, and later in life nicknamed the "Black Prince of Perthshire", was the last ''Maharaja'' of the Sikh Empire. He was Maharaja Ranjit Singh's youngest son ...

, campaigned for support for the British Indian Army

The British Indian Army, commonly referred to as the Indian Army, was the main military of the British Raj before its dissolution in 1947. It was responsible for the defence of the British Indian Empire, including the princely states, which co ...

and lascar

A lascar was a sailor or militiaman from the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, the Arab world, British Somaliland, or other land east of the Cape of Good Hope, who was employed on European ships from the 16th century until the middle of the 2 ...

s working in the Merchant Navy. She also joined a 10,000-woman protest march against the prohibition of a volunteer female force. Singh volunteered as a British Red Cross

The British Red Cross Society is the United Kingdom body of the worldwide neutral and impartial humanitarian network the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. The society was formed in 1870, and is a registered charity with more ...

Voluntary Aid Detachment

The Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) was a voluntary unit of civilians providing nursing care for military personnel in the United Kingdom and various other countries in the British Empire. The most important periods of operation for these units we ...

nurse, serving at an auxiliary military hospital in Isleworth

Isleworth ( ) is a town located within the London Borough of Hounslow in West London, England. It lies immediately east of the town of Hounslow and west of the River Thames and its tributary the River Crane, London, River Crane. Isleworth's or ...

from October 1915 to January 1917.

The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies

The National Union of Women Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), also known as the ''suffragists'' (not to be confused with the suffragettes) was an organisation founded in 1897 of women's suffrage societies around the United Kingdom. In 1919 it was ren ...

, which had always employed "constitutional" methods, continued to lobby during the war years and compromises were worked out between the NUWSS and the coalition government.Cawood, Ian; McKinnon-Bell, David (2001). ''The First World War''. p.71. Routledge 2001 On 6 February, the Representation of the People Act 1918 was passed, enfranchising all men over 21 years of age and women over the age of 30 who met minimum property qualifications, gaining the right to vote for about 8.4 million women. In November 1918, the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918

The Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It gave women over 21 the right to stand for election as a Member of Parliament.

At 27 words, it is the shortest UK statute.

Background

The R ...

was passed, allowing women to be elected into parliament.Fawcett, Millicent Garrett. ''The Women's Victory – and After''. p.170. Cambridge University Press The Representation of the People Act 1928

The Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. This act expanded on the Representation of the People Act 1918 which had given some women the vote in Parliamentary elections for the ...

extended the voting franchise to all women over the age of 21, granting women the vote on the same terms that men had gained ten years earlier.

1918 general election, women members of parliament

The 1918 general election, the first general election to be held after the Representation of the People Act 1918, was the first in which some women (property owners older than 30) could vote. At that election, the first woman to be elected an MP wasConstance Markievicz

Constance Georgine Markievicz ( pl, Markiewicz ; ' Gore-Booth; 4 February 1868 – 15 July 1927), also known as Countess Markievicz and Madame Markievicz, was an Irish politician, revolutionary, nationalist, suffragist, socialist, and the fir ...

but, in line with Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

abstentionist

Abstentionism is standing for election to a deliberative assembly while refusing to take up any seats won or otherwise participate in the assembly's business. Abstentionism differs from an election boycott in that abstentionists participate in ...

policy, she declined to take her seat in the British House of Commons. The first woman to do so was Nancy Astor, Viscountess Astor

Nancy Witcher Langhorne Astor, Viscountess Astor, (19 May 1879 – 2 May 1964) was an American-born British politician who was the first woman seated as a Member of Parliament (MP), serving from 1919 to 1945.

Astor's first husband was America ...

, following a by-election in November 1919.

Legacy

In the autumn of 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst had sailed to the US to embark on a lecture tour to publicise the message of the WSPU and to raise money for the treatment of her son, Harry, who was gravely ill. By this time the suffragettes' tactics of civil disorder were being used by American militants

In the autumn of 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst had sailed to the US to embark on a lecture tour to publicise the message of the WSPU and to raise money for the treatment of her son, Harry, who was gravely ill. By this time the suffragettes' tactics of civil disorder were being used by American militants Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ...

and Lucy Burns

Lucy Burns (July 28, 1879 – December 22, 1966) was an American suffragist and women's rights advocate.Bland, 1981 (p. 8) She was a passionate activist in the United States and the United Kingdom, who joined the militant suffragettes. Burns w ...

, both of whom had campaigned with the WSPU in London. As in the UK, the suffrage movement in America was divided into two disparate groups, with the National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National ...

representing the more militant campaign and the International Women's Suffrage Alliance

The International Alliance of Women (IAW; french: Alliance Internationale des Femmes, AIF) is an international non-governmental organization that works to promote women's rights and gender equality. It was historically the main international org ...

taking a more cautious and pragmatic approach Although the publicity surrounding Pankhurst's visit and the militant tactics used by her followers gave a welcome boost to the campaign, the majority of women in the US preferred the more respected label of "suffragist" to the title "suffragette" adopted by the militants.

Many suffragists at the time, and some historians since, have argued that the actions of the militant suffragettes damaged their cause. Opponents at the time saw evidence that women were too emotional and could not think as logically as men.... Historians generally argue that the first stage of the militant suffragette movement under the Pankhursts in 1906 had a dramatic mobilising effect on the suffrage movement. Women were thrilled and supportive of an actual revolt in the streets. The membership of the militant WSPU and the older NUWSS overlapped and were mutually supportive. However, a system of publicity, Ensor argues, had to continue to escalate to maintain its high visibility in the media. The hunger strikes and force-feeding did that, but the Pankhursts refused any advice and escalated their tactics. They turned to systematic disruption of Liberal Party meetings as well as physical violence in terms of damaging public buildings and arson. Searle says the methods of the suffragettes harmed the Liberal Party but failed to advance women's suffrage. When the Pankhursts decided to stop their militancy at the start of the war and enthusiastically support the war effort, the movement split and their leadership role ended. Suffrage came four years later, but the feminist movement in Britain permanently abandoned the militant tactics that had made the suffragettes famous.

After Emmeline Pankhurst's death in 1928, money was raised to commission a statue, and on 6 March 1930 the statue in

After Emmeline Pankhurst's death in 1928, money was raised to commission a statue, and on 6 March 1930 the statue in Victoria Tower Gardens

Victoria Tower Gardens is a public park along the north bank of the River Thames in London, adjacent to the Victoria Tower, at the south-western corner of the Palace of Westminster. The park, extends southwards from the Palace to Lambeth Brid ...

was unveiled. A crowd of radicals, former suffragettes and national dignitaries gathered as former Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

presented the memorial to the public. In his address, Baldwin declared: In 1929 a portrait of Emmeline Pankhurst was added to the National Portrait Gallery's collection. In 1987 her former home at 62 Nelson Street, Manchester, the birthplace of the WSPU, and the adjoining Edwardian villa (no. 60) were opened as the Pankhurst Centre, a women-only space

A women-only space is an area where only women (and in some cases children) are allowed, thus providing a place where they do not have to interact with men. Historically and globally, many cultures had, and many still have, some form of female sec ...

and museum dedicated to the suffragette movement. Christabel Pankhurst was appointed a Dame Commander

Commander ( it, Commendatore; french: Commandeur; german: Komtur; es, Comendador; pt, Comendador), or Knight Commander, is a title of honor prevalent in chivalric orders and fraternal orders.

The title of Commander occurred in the medieval mil ...

of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

in 1936, and after her death in 1958 a permanent memorial was installed next to the statue of her mother. The memorial to Christabel Pankhurst consists of a low stone screen flanking her mother's statue with a bronze medallion plaque depicting her profile at one end of the screen paired with a second plaque depicting the "prison brooch" or "badge" of the WSPU at the other end. The unveiling of this dual memorial was performed on 13 July 1959 by the Lord Chancellor, Lord Kilmuir

David Patrick Maxwell Fyfe, 1st Earl of Kilmuir, (29 May 1900 – 27 January 1967), known as Sir David Maxwell Fyfe from 1942 to 1954 and as Viscount Kilmuir from 1954 to 1962, was a British Conservative politician, lawyer and judge who combine ...

. The Pankhurst's name and image and those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters are etched on the plinth

A pedestal (from French ''piédestal'', Italian ''piedistallo'' 'foot of a stall') or plinth is a support at the bottom of a statue, vase, column, or certain altars. Smaller pedestals, especially if round in shape, may be called socles. In c ...

of the statue of Millicent Fawcett

The statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, honours the British suffragist leader and social campaigner Dame Millicent Fawcett. It was made in 2018 by Gillian Wearing. Following a campaign and petition by the activist Caroline ...

in Parliament Square

Parliament Square is a square at the northwest end of the Palace of Westminster in the City of Westminster in central London. Laid out in the 19th century, it features a large open green area in the centre with trees to its west, and it contai ...

, London that was unveiled in 2018.

In 1903, the Australian suffragist Vida Goldstein

Vida Jane Mary Goldstein (pron. ) (13 April 186915 August 1949) was an Australian suffragist and social reformer. She was one of four female candidates at the 1903 federal election, the first at which women were eligible to stand.

Goldstein wa ...

adopted the WSPU colours for her campaign for the Senate in 1910 but got them slightly wrong since she thought that they were purple, green and lavender. Goldstein had visited England in 1911 at the behest of the WSPU. Her speeches around the country drew huge crowds and her tour was touted as "the biggest thing that has happened in the women movement for sometime in England". The correct colours were used for her campaign for Kooyong in 1913 and also for the flag of the Women's Peace Army, which she established during World War I to oppose conscription. During International Women's Year

International Women's Year (IWY) was the name given to 1975 by the United Nations. Since that year March 8 has been celebrated as International Women's Day, and the United Nations Decade for Women, from 1976 to 1985, was also established.

Hist ...

in 1975 the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Shoulder to Shoulder

''Shoulder to Shoulder'' is a 1974 BBC television serial and book relating the history of the women's suffrage movement, both edited by Midge Mackenzie. The drama series grew out of discussions between Mackenzie and the actress and singer Georg ...

, was screened across Australia and Elizabeth Reid, Women's Adviser to Prime Minister Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from 1972 to 1975. The longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1967 to 1977, he was notable for being the he ...

directed that the WSPU colours be used for the International Women's Year symbol. They were also used for a first-day cover and postage stamp released by Australia Post

Australia Post, formally the Australian Postal Corporation, is the government business enterprise that provides postal services in Australia. The head office of Australia Post is located in Bourke Street, Melbourne, which also serves as a post o ...

in March 1975. The colours have since been adopted by government bodies such as the National Women's Advisory Council and organisations such as Women's Electoral Lobby and other women's services such as domestic violence refuges and are much in evidence each year on International Women's day

International Women's Day (IWD) is a global holiday celebrated annually on March 8 as a focal point in the women's rights movement, bringing attention to issues such as gender equality, reproductive rights, and violence and abuse against wom ...

.

The colours of green and heliotrope (purple) were commissioned into a new coat of arms for Edge Hill University

Edge Hill University is a campus-based public university in Ormskirk, Lancashire, England, which opened in 1885 as Edge Hill College, the first non-denominational teacher training college for women in England, before admitting its first male st ...

in Lancashire in 2006, symbolising the university's early commitment to the equality of women through its beginnings as a women-only college.

During the 1960s, the memory of the suffragettes was kept alive in the public consciousness by portrayals in film, such as the character Mrs Winifred Banks in the 1964 Disney musical film ''Mary Poppins It may refer to:

* ''Mary Poppins'' (book series), the original 1934–1988 children's fantasy novels that introduced the character.

* Mary Poppins (character), the nanny with magical powers.

* ''Mary Poppins'' (film), a 1964 Disney film sta ...

'' who sings the song

" Sister Suffragette" and Maggie DuBois in the 1965 film ''The Great Race

''The Great Race'' is a 1965 American Technicolor slapstick comedy film starring Jack Lemmon, Tony Curtis, and Natalie Wood, directed by Blake Edwards, written by Arthur A. Ross (from a story by Edwards and Ross), and with music by Henry Mancin ...

''. In 1974 The BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Shoulder to Shoulder

''Shoulder to Shoulder'' is a 1974 BBC television serial and book relating the history of the women's suffrage movement, both edited by Midge Mackenzie. The drama series grew out of discussions between Mackenzie and the actress and singer Georg ...

'' portraying events in the British militant suffrage movement, concentrating on the lives of members of the Pankhurst family was shown around the world. And in the 21st century the story of the suffragettes was brought to a new generation in the BBC television series ''Up the Women

''Up the Women'' is a BBC television sitcom created, written by and starring Jessica Hynes. It was first broadcast on BBC Four on 30 May 2013. The sitcom is about a group of women in 1910 who form a Women's Suffrage movement. Hynes originally p ...

'', the 2015 graphic novel

A graphic novel is a long-form, fictional work of sequential art. The term ''graphic novel'' is often applied broadly, including fiction, non-fiction, and anthologized work, though this practice is highly contested by comic scholars and industry ...

trilogy '' Suffrajitsu: Mrs. Pankhurst's Amazons'' and the 2015 film ''Suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

''.

In recognition of having meetings at the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

in London, the Suffragettes were inducted into the Hall's Walk of Fame in 2018, making them one of the first eleven recipients of a star on the walk, joining Eric Clapton

Eric Patrick Clapton (born 1945) is an English rock and blues guitarist, singer, and songwriter. He is often regarded as one of the most successful and influential guitarists in rock music. Clapton ranked second in ''Rolling Stone''s list of ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, a ...

and Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

, among others who were viewed as "key players" in the building's history.

In February 2019, female Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

members of the US Congress dressed predominantly in white when attending President Trump's State of the Union

The State of the Union Address (sometimes abbreviated to SOTU) is an annual message delivered by the president of the United States to a joint session of the United States Congress near the beginning of each calendar year on the current conditio ...

address. The choice of one of the colours associated with the suffragettes was to signify the women's solidarity.

The achievement of women's voting rights for elections to the House of Commons did not secure votes for all British women. Despite it being explicitly asserted in the Royal charters of the Virginia Company

The Virginia Company was an English trading company chartered by King James I on 10 April 1606 with the object of colonizing the eastern coast of America. The coast was named Virginia, after Elizabeth I, and it stretched from present-day Main ...

(in 1607) and its spin-ff, the Somers Isles Company

The Somers Isles Company (fully, the Company of the City of London for the Plantacion of The Somers Isles or the Company of The Somers Isles) was formed in 1615 to operate the English colony of the Somers Isles, also known as Bermuda, as a commerc ...

(in 1615), that those who chose to settle in England's colonies and their descendants would receive the same enfranchisement as if they had been born in England, the British Government has never created voting districts for the British Parliament in any colony, effectively disenfranchising the women and men of the British Overseas Territories

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs), also known as the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs), are fourteen dependent territory, territories with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom. They are the last remna ...

. Local representative governments were created in a number of colonies, starting with Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

(1619) and Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

, or the Somers Isles (1620), but enfranchisement of women for elections to the British Parliament did not necessarily compel the local assemblies to grant women the vote and the struggle would continue.

Notable people

Great Britain

*Margaret Aldersley

Margaret Aldersley (1852–1940) was a British suffragist, feminist and trade unionist.

Biography

Born in 1852 in Burnley in Lancashire into a working-class family, Margaret Aldersley originally worked in the textile industry before becoming invo ...

* Mary Ann Aldham

Mary Ann Aldham (born Mary Ann Mitchell Wood; 28 September 1858 – 1940) was an English militant suffragette and member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) who was imprisoned at least seven times.Doreen Allen

Doreen Allen (1879 – 18 June 1963) was a militant English suffragette and member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), who on being imprisoned was force-fed, for which she received the WSPU's Hunger Strike Medal For Valour'' ...

* Emily Davison

Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was an English suffragette who fought for Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom, votes for women in Britain in the early twentieth century. A member of the Women's Social and Polit ...

* Gertrude Ansell

* Joan Beauchamp

* Edith Marian Begbie

Edith Marian Begbie (8 February 1866 – 27 March 1932) was a militant Scottish suffragette and member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) who went on hunger strike in Winson Green Prison in Birmingham in 1912 and who was awarded ...

* Rosa May Billinghurst

* Elsie Bowerman

Elsie Edith Bowerman (18 December 1889 – 18 October 1973) was a British lawyer, suffragette, political activist, and RMS ''Titanic'' survivor.

Early life

Elsie Edith Bowerman was born in Tunbridge Wells, Kent, the only daughter of Willia ...

* Janet Boyd

Janet Augusta Boyd (née Haig; 1850 – 22 September 1928) was a member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and militant suffragette who in 1912 went on hunger strike in prison for which action she was awarded the WSPU's Hunger Str ...

* Lady Constance Bulwer-Lytton

Lady Constance Georgina Bulwer-Lytton (12 February 1869 – 2 May 1923), usually known as Constance Lytton, was an influential British suffragette activist, writer, speaker and campaigner for prison reform, votes for women, and birth control. S ...

* Evaline Hilda Burkitt

Evaline Hilda Burkitt (19 July 1876 – 7 March 1955) was a British suffragette and member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). A militant activist for women's rights, she went on hunger strike in prison and was the first suffra ...

* Mabel Capper

Mabel Henrietta Capper (23 June 1888 – 1 September 1966) was a British suffragette. She gave all her time between 1907 and 1913 to the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) as a 'soldier' in the struggle for women's suffrage. She was imp ...

* Georgina Fanny Cheffins

Georgina Fanny Cheffins (1863 – 29 July 1932) was an English militant suffragette who on her imprisonment in 1912 went on hunger strike for which action she received the Hunger Strike Medal from the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) ...

* Ada Nield Chew

Ada Nield Chew (28 January 1870 – 27 December 1945) was a campaigning socialist and a British suffragist. Her name is on the plinth of Millicent Fawcett's statue in Parliament Square, London.

Life

Nield was born on a White Hall Farm, Talk ...

* Anne Cobden-Sanderson

Julia Sarah Anne Cobden-Sanderson (; 26 March 1853 – 2 November 1926) was an English socialist, suffragette and vegetarian.

Life

Cobden was born in London in 1853 to Catherine Anne and the radical politician Richard Cobden. After her father ...

* Leonora Cohen

Leonora Cohen (; 15 June 1873 – 4 September 1978) was a British suffragette and trade unionist, and one of the first female magistrates. She was known as the "Tower Suffragette" after smashing a display case in the Tower of London and acted ...

* Rose Cohen

* Jessie Craigen

Jessie Hannah Craigen (''c''.1835–5 October 1899), was a working-class suffrage speaker in a movement which was predominantly made up of middle and upper-class activists. She was also a freelance (or 'paid agent') speaker in the campaigns for ...

* Emily Wilding Davison

Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was an English suffragette who fought for Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom, votes for women in Britain in the early twentieth century. A member of the Women's Social and Polit ...

* Violet Mary Doudney

Violet Mary Doudney (5 March 1889 – 14 January 1952) was a teacher and militant suffragette who went on hunger strike in Holloway Prison where she was force-fed. She was awarded the Hunger Strike Medal by the Women's Social and Political U ...

* Katherine Douglas Smith