Zugspitze on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Zugspitze (), at above

At (eastern peak) the Zugspitze is the highest mountain of the Zugspitze massif. This height is referenced to the Amsterdam Gauge and is given by the Bavarian State Office for Survey and Geoinformation. The same height is recorded against the Trieste Gauge used in Austria, which is 27 cm lower. Originally the Zugspitze had three

At (eastern peak) the Zugspitze is the highest mountain of the Zugspitze massif. This height is referenced to the Amsterdam Gauge and is given by the Bavarian State Office for Survey and Geoinformation. The same height is recorded against the Trieste Gauge used in Austria, which is 27 cm lower. Originally the Zugspitze had three  The

The  The ''Platt'' or ''Zugspitzplatt'' is a

The ''Platt'' or ''Zugspitzplatt'' is a

For the decades from 1961 to 1990 – designated by the

For the decades from 1961 to 1990 – designated by the

The

The

The shaded and moist northern slopes of the massif like, for example, the Wettersteinwald, are some of the most species-rich environments on the Zugspitze. The

The shaded and moist northern slopes of the massif like, for example, the Wettersteinwald, are some of the most species-rich environments on the Zugspitze. The

The rocks around the Zugspitze are a habitat for

The rocks around the Zugspitze are a habitat for

The Höllentalferner lies northeast of the Zugspitze in a

The Höllentalferner lies northeast of the Zugspitze in a  Southwest of the Zugspitze, between the ''Zugspitzeck'' and

Southwest of the Zugspitze, between the ''Zugspitzeck'' and

Since 1851 there has been a summit cross on the top of Zugspitze. The driving force behind the erection of a cross on the summit was the priest, Christoph Ott. He was a keen meteorologist and whilst observing conditions from the

Since 1851 there has been a summit cross on the top of Zugspitze. The driving force behind the erection of a cross on the summit was the priest, Christoph Ott. He was a keen meteorologist and whilst observing conditions from the

The first recorded ascent to the summit was accomplished by a team of land surveyors on 27 August 1820. The team was led by Lieutenant

The first recorded ascent to the summit was accomplished by a team of land surveyors on 27 August 1820. The team was led by Lieutenant  Shortly after World War II the

Shortly after World War II the

There are several theories about the first ascent of the Zugspitze. The chronological table on an 18th-century map describes the route ''"along the path to the Zugspitze"'' (''"ybers blath uf Zugspitze"'') and gives a realistic duration of 8.5 hours, so that it is reasonable to deduce that the summit had been climbed before 1820. The historian, Thomas Linder, believes that goatherds or hunters had at the very least penetrated to the area of the summit. It is also conceivable that

There are several theories about the first ascent of the Zugspitze. The chronological table on an 18th-century map describes the route ''"along the path to the Zugspitze"'' (''"ybers blath uf Zugspitze"'') and gives a realistic duration of 8.5 hours, so that it is reasonable to deduce that the summit had been climbed before 1820. The historian, Thomas Linder, believes that goatherds or hunters had at the very least penetrated to the area of the summit. It is also conceivable that

In 1823, Simon Resch and the sheep ''Toni'' became the first to reach the East Summit. Simon Resch was also led the second ascent of the East Summit on 18 September 1834 with his son, Johann, and the mountain guide, Johann Barth. Because Resch's first ascent had been doubted, this time a fire was lit on the summit. On the 27th the summit was climbed for a third time by royal forester's assistants, Franz Oberst and Schwepfinger, along with Johann Barth. Oberst erected a flagpole on the summit with a Bavarian flag that was visible from the valley. The first ascent from Austria took place in August 1837. The surveyors, Joseph Feuerstein and Joseph Sonnweber, climbed to the West Summit from Ehrwald and left behind a signal pole with their initials on it. The West Summit was conquered for the third time on 10 September 1843 by the shepherd Peter Pfeifer. He was asked about the route by a group of eight climbers who later reached the summit at the behest of Bavaria's Crown Princess Marie. She had the route checked in preparation for her own ascent of the Zugspitze. On 22 September 1853, Karoline Pitzner became the first woman on the Zugspitze.

The first crossing from the West to the East Summit was achieved in 1857 by Dr. Härtringer from Munich and mountain guide, Joseph Ostler. The Irish brother, Trench, and Englishman, Cluster, succeeded in climbing the West Summit on 8 July 1871 through the Austrian Cirque (''Österreichische Schneekar'') under the guidance of brothers, Joseph and Joseph Sonnweber. The route through the Höllental valley to the Zugspitze was first used on 26 September 1876 by Franz Tillmetz and Franz Johannes with guides, Johann and Joseph Dengg. The first winter ascent of the West Summit took place on 7 Januar 1882; the climbers being Ferdinand Kilger, Heinrich Schwaiger, Josef and Heinrich Zametzer and Alois Zott. The Jubilee Arête (''Jubiläumsgrat'') was first crossed in its entirety on 2 September 1897 by Ferdinand Henning. The number of climbers on the Zugspitze rose sharply year on year. If the summit had been climbed 22 times in 1854, by 1899 it had received 1,600 ascents. Before the construction of a cable car in 1926 there had already been over 10,000 ascents.

In 1823, Simon Resch and the sheep ''Toni'' became the first to reach the East Summit. Simon Resch was also led the second ascent of the East Summit on 18 September 1834 with his son, Johann, and the mountain guide, Johann Barth. Because Resch's first ascent had been doubted, this time a fire was lit on the summit. On the 27th the summit was climbed for a third time by royal forester's assistants, Franz Oberst and Schwepfinger, along with Johann Barth. Oberst erected a flagpole on the summit with a Bavarian flag that was visible from the valley. The first ascent from Austria took place in August 1837. The surveyors, Joseph Feuerstein and Joseph Sonnweber, climbed to the West Summit from Ehrwald and left behind a signal pole with their initials on it. The West Summit was conquered for the third time on 10 September 1843 by the shepherd Peter Pfeifer. He was asked about the route by a group of eight climbers who later reached the summit at the behest of Bavaria's Crown Princess Marie. She had the route checked in preparation for her own ascent of the Zugspitze. On 22 September 1853, Karoline Pitzner became the first woman on the Zugspitze.

The first crossing from the West to the East Summit was achieved in 1857 by Dr. Härtringer from Munich and mountain guide, Joseph Ostler. The Irish brother, Trench, and Englishman, Cluster, succeeded in climbing the West Summit on 8 July 1871 through the Austrian Cirque (''Österreichische Schneekar'') under the guidance of brothers, Joseph and Joseph Sonnweber. The route through the Höllental valley to the Zugspitze was first used on 26 September 1876 by Franz Tillmetz and Franz Johannes with guides, Johann and Joseph Dengg. The first winter ascent of the West Summit took place on 7 Januar 1882; the climbers being Ferdinand Kilger, Heinrich Schwaiger, Josef and Heinrich Zametzer and Alois Zott. The Jubilee Arête (''Jubiläumsgrat'') was first crossed in its entirety on 2 September 1897 by Ferdinand Henning. The number of climbers on the Zugspitze rose sharply year on year. If the summit had been climbed 22 times in 1854, by 1899 it had received 1,600 ascents. Before the construction of a cable car in 1926 there had already been over 10,000 ascents.

The easiest of the normal routes runs through the Reintal valley and is that followed during the first ascent. At the same time it is also the longest climb. Its start point is the ski stadium () at

The easiest of the normal routes runs through the Reintal valley and is that followed during the first ascent. At the same time it is also the longest climb. Its start point is the ski stadium () at  The ascent starts in Hammersbach () through the Höllental along the ''Hammersbach'' stream. The path runs through the Höllental Gorge (''Höllentalklamm'') and was built from 1902 to 1905. Twelve tunnels were driven in the rock of the 1,026 metre long gorge with a total length of 288 metres. Another 569 metres of path was dynamited into the rock in the shape of a half profile, whilst 120 metres was led over

The ascent starts in Hammersbach () through the Höllental along the ''Hammersbach'' stream. The path runs through the Höllental Gorge (''Höllentalklamm'') and was built from 1902 to 1905. Twelve tunnels were driven in the rock of the 1,026 metre long gorge with a total length of 288 metres. Another 569 metres of path was dynamited into the rock in the shape of a half profile, whilst 120 metres was led over

One of the best-known ridge routes in the Eastern Alps is the Jubilee Ridge, which runs eastwards from the Zugspitze to the

One of the best-known ridge routes in the Eastern Alps is the Jubilee Ridge, which runs eastwards from the Zugspitze to the

There are numerous

There are numerous  There has been an accommodation hut just underneath the west summit since 1883. At that time the Alpine Club section at Munich built a wooden hut with places for twelve people. Although further development of the summit for tourism was criticised, more and more members supported the construction of a larger hut. This eventually resulted in the building of the Münchner Haus (). First, in 1896, a 200 square metre site was dynamited out of the rock. The new mountain hut was completed on 19 September 1897 at a cost of 36,615 gold marks. It was equipped with a 21 kilometre long telephone cable and a 5.5 kilometre long

There has been an accommodation hut just underneath the west summit since 1883. At that time the Alpine Club section at Munich built a wooden hut with places for twelve people. Although further development of the summit for tourism was criticised, more and more members supported the construction of a larger hut. This eventually resulted in the building of the Münchner Haus (). First, in 1896, a 200 square metre site was dynamited out of the rock. The new mountain hut was completed on 19 September 1897 at a cost of 36,615 gold marks. It was equipped with a 21 kilometre long telephone cable and a 5.5 kilometre long

For those wishing to reach the summit under their own power, various hiking and ski trails can be followed to the top. Hiking to the top from the base takes between one and two days, or a few hours for the very fit. Food and lodging is available on some trails. In winter the Zugspitze is a popular

For those wishing to reach the summit under their own power, various hiking and ski trails can be followed to the top. Hiking to the top from the base takes between one and two days, or a few hours for the very fit. Food and lodging is available on some trails. In winter the Zugspitze is a popular

Climbing up the Zugspitze can involve several routes. The large difference in elevation between Garmisch-Partenkirchen and the summit is , making the climb a challenge even for trained

Climbing up the Zugspitze can involve several routes. The large difference in elevation between Garmisch-Partenkirchen and the summit is , making the climb a challenge even for trained

Zugspitze on Distantpeak.com

* More comprehensive article about the Zugspitze in German Wikipedia * Computer generated summit panorama

NorthSouth

Bayerische Zugspitzbahn Bergbahn AG – Transportation to the mountain top and local webcams

ZUGSPITZE 360°

climbing the Zugspitze via 360 panorama photos. {{Authority control Mountains of Bavaria Mountains of Tyrol (state) Mountains of the Alps International mountains of Europe Austria–Germany border Two-thousanders of Austria Wetterstein Garmisch-Partenkirchen Tourist attractions in Bavaria Two-thousanders of Germany Highest points of countries Wind gaps

sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised g ...

, is the highest peak of the Wetterstein Mountains

The Wetterstein mountains (german: Wettersteingebirge), colloquially called Wetterstein, is a mountain group in the Northern Limestone Alps within the Eastern Alps. It is a comparatively compact range located between Garmisch-Partenki ...

as well as the highest mountain

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited Summit (topography), summit area, and ...

in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. It lies south of the town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen

Garmisch-Partenkirchen (; Bavarian: ''Garmasch-Partakurch''), nicknamed Ga-Pa, is an Alpine ski town in Bavaria, southern Germany. It is the seat of government of the district of Garmisch-Partenkirchen (abbreviated ''GAP''), in the O ...

, and the Austria–Germany border

The Austria–Germany border () has a length of or in the south of Germany and the north of Austria in central Europe. It is the longest border of both Austria and Germany with another country.

Route

The border runs roughly from east to west. ...

runs over its western summit. South of the mountain is the ''Zugspitzplatt'', a high karst

Karst is a topography formed from the dissolution of soluble rocks such as limestone, dolomite, and gypsum. It is characterized by underground drainage systems with sinkholes and caves. It has also been documented for more weathering-resistant ro ...

plateau

In geology and physical geography, a plateau (; ; ), also called a high plain or a tableland, is an area of a highland consisting of flat terrain that is raised sharply above the surrounding area on at least one side. Often one or more sides ha ...

with numerous caves. On the flanks of the Zugspitze are three glaciers, including the two largest in Germany: the Northern Schneeferner with an area of 30.7 hectare

The hectare (; SI symbol: ha) is a non-SI metric unit of area equal to a square with 100-metre sides (1 hm2), or 10,000 m2, and is primarily used in the measurement of land. There are 100 hectares in one square kilometre. An acre is a ...

s and the Höllentalferner

The Höllentalferner is a glacier in the western Wetterstein Mountains. It is a cirque glacier that covers the upper part of the Höllental valley and its location in a rocky bowl between the Riffelwandspitzen and Germany's highest mountain, the ...

with an area of 24.7 hectares. The third is the Southern Schneeferner which covers 8.4 hectares.

The Zugspitze was first climbed on 27 August 1820 by Josef Naus

Josef Naus (1793–1871) was an officer and surveying technician, known for leading the first ascent of Germany's highest mountain, the Zugspitze. Variations of his name are Karl Naus or Joseph Naus.

Life and career

Naus was born on 29 August ...

, his survey assistant, Maier, and mountain guide

A mountain guide is a specially trained and experienced professional mountaineer who is certified by local authorities or mountain guide associations. They are considered to be high-level experts in mountaineering, and are hired to instruct or ...

, Johann Georg Tauschl. Today there are three normal route

A normal route or normal way (french: voie normale; german: Normalweg) is the most frequently used route for ascending and descending a mountain peak. It is usually the simplest route.

Overview

In the Alps, routes are classed in the following way ...

s to the summit: one from the Höllental valley to the northeast; another out of the Reintal valley to the southeast; and the third from the west over the Austrian Cirque (''Österreichische Schneekar''). One of the best known ridge routes in the Eastern Alps

Eastern Alps is the name given to the eastern half of the Alps, usually defined as the area east of a line from Lake Constance and the Alpine Rhine valley up to the Splügen Pass at the Alpine divide and down the Liro River to Lake Como in t ...

runs along the knife-edged Jubilee Ridge (''Jubiläumsgrat

The Jubiläumsgrat ("Jubilee Arête") or Jubiläumsweg ("Jubilee Way"), also nicknamed ''Jubi'' in climbing circles, is the name given to the climbing route along the arête between the Zugspitze (2,962 m) and the Hochblassen (2,706 m) (hence i ...

'') to the summit, linking the Zugspitze, the Hochblassen

The Hochblassen is a mountain high, located in the Wetterstein in the German state of Bavaria. In addition to the main summit, it has a sub-peak, the so-called ''Signalgipfel'' ("signal peak") which is high. It was first climbed in 1871 by Herma ...

and the Alpspitze

The Alpspitze is a mountain, 2628 m, in Bavaria, Germany. Its pyramidal peak is the symbol of Garmisch-Partenkirchen and is one of the best known and most attractive mountains of the Northern Limestone Alps. It is made predominantly of Wetter ...

. For mountaineers there is plenty of nearby accommodation. On the western summit of the Zugspitze itself is the Münchner Haus and on the western slopes is the Wiener-Neustädter Hut.

Three cable cars run to the top of the Zugspitze. The first, the Tyrolean Zugspitze Cable Car

The Zugspitzebahn was the first wire ropeway to open the summit of the Zugspitze, Germany's highest mountain on the border of Austria. Designed and built by Adolf Bleichert & Co. of Leipzig, Germany, the system was a record-holder for the h ...

, was built in 1926 by the German company ''Adolf Bleichert

Bleichert, short for Adolf Bleichert & Co., was a German engineering firm founded in 1874 by Adolf Bleichert. The company dominated the aerial wire ropeway industry during the first half of the 20th century, and its portfolio included cranes, el ...

& Co'' and terminated on an arête

An arête ( ) is a narrow ridge of rock which separates two valleys. It is typically formed when two glaciers erode parallel U-shaped valleys. Arêtes can also form when two glacial cirques erode headwards towards one another, although frequen ...

below the summit at 2,805 m.a.s.l, the so-called Kammstation, before the terminus was moved to the actual summit at 2,951 m.a.s.l. in 1991. A rack railway

A rack railway (also rack-and-pinion railway, cog railway, or cogwheel railway) is a steep grade railway with a toothed rack rail, usually between the running rails. The trains are fitted with one or more cog wheels or pinions that mesh with th ...

, the Bavarian Zugspitze Railway

The Bavarian Zugspitze Railway (german: Bayerische Zugspitzbahn) is one of four rack railways still working in Germany, along with the Wendelstein Railway, the Drachenfels Railway and the Stuttgart Rack Railway. The metre gauge line runs from Ga ...

, runs inside the northern flank of the mountain and ends on the ''Zugspitzplatt'', from where a second cable car takes passengers to the top. The rack railway and the Eibsee Cable Car

The Seilbahn Zugspitze is an aerial tramway running from the Eibsee Lake to the top of Zugspitze in Bavaria, Germany. It holds the world record for the longest freespan in a cable car at as well as the tallest lattice steel aerial tramway supp ...

, the third cableway, transport an average of 500,000 people to the summit each year. In winter, nine ski lift

A ski lift is a mechanism for transporting skiers up a hill. Ski lifts are typically a paid service at ski resorts. The first ski lift was built in 1908 by German Robert Winterhalder in Schollach/Eisenbach, Hochschwarzwald.

Types

* Aerial ...

s cover the ski area

A ski area is the terrain and supporting infrastructure where skiing and other snow sports take place. Such sports include alpine and cross-country skiing, snow boarding, tubing, sledding, etc. Ski areas may stand alone or be part of a ski resort.

...

on the ''Zugspitzplatt''. The weather station, opened in 1900, and the research station in the Schneefernerhaus are mainly used to conduct climate research.

Geography

The Zugspitze belongs to theWetterstein

The Wetterstein mountains (german: Wettersteingebirge), colloquially called Wetterstein, is a mountain group in the Northern Limestone Alps within the Eastern Alps. It is a comparatively compact range located between Garmisch-Partenkir ...

range of the Northern Limestone Alps

The Northern Limestone Alps (german: Nördliche Kalkalpen), also called the Northern Calcareous Alps, are the ranges of the Eastern Alps north of the Central Eastern Alps located in Austria and the adjacent Bavarian lands of southeastern Germa ...

. The Austria–Germany border

The Austria–Germany border () has a length of or in the south of Germany and the north of Austria in central Europe. It is the longest border of both Austria and Germany with another country.

Route

The border runs roughly from east to west. ...

goes right over the mountain. There used to be a border checkpoint at the summit but, since Germany and Austria are now both part of the Schengen zone

The Schengen Area ( , ) is an area comprising 27 European countries that have officially abolished all passport and all other types of border control at their mutual borders. Being an element within the wider area of freedom, security and ...

, the border crossing is no longer manned.

The exact height of the Zugspitze was a matter of debate for quite a while. Given figures ranged from , but it is now generally accepted that the peak is above sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised g ...

as a result of a survey carried out by the Bavarian State Survey Office. The lounge at the new café is named "2962" for this reason.

Location

peaks Peak or The Peak may refer to:

Basic meanings Geology

* Mountain peak

** Pyramidal peak, a mountaintop that has been sculpted by erosion to form a point Mathematics

* Peak hour or rush hour, in traffic congestion

* Peak (geometry), an (''n''-3)-d ...

: the east, middle and west summits (''Ost-'', ''Mittel-'' and ''Westgipfel''). The only one that has remained in its original form is the east summit, which is also the only one that lies entirely on German territory. The middle summit fell victim to one of the cable car summit stations in 1930. In 1938 the west summit was blown up to create a building site for a planned flight control room for the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

''. This was never built however. Originally the height of the west summit was given as .

The mountain rises eleven kilometres southwest of Garmisch-Partenkirchen

Garmisch-Partenkirchen (; Bavarian: ''Garmasch-Partakurch''), nicknamed Ga-Pa, is an Alpine ski town in Bavaria, southern Germany. It is the seat of government of the district of Garmisch-Partenkirchen (abbreviated ''GAP''), in the O ...

and just under six kilometres east of Ehrwald

Ehrwald is a municipality in the district of Reutte in the Austrian state of Tyrol.

Geography

Ehrwald lies at the southern base of the Zugspitze (2950 meters above sea level), Germany's highest mountain, but which is shared with Austria. The tow ...

. The border between Germany and Austria runs over the west summit; thus the Zugspitze massif belongs to the German state of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

and the Austrian state of Tyrol

Tyrol (; historically the Tyrole; de-AT, Tirol ; it, Tirolo) is a historical region in the Alps - in Northern Italy and western Austria. The area was historically the core of the County of Tyrol, part of the Holy Roman Empire, Austrian Emp ...

. The municipalities responsible for it are Grainau

Grainau is a municipality in the district of Garmisch-Partenkirchen, in southern Bavaria, Germany. It is located at the foot of the Zugspitze mountain, the tallest mountain in Germany in the sub-mountain range of the Wetterstein Alps which is a b ...

and Ehrwald

Ehrwald is a municipality in the district of Reutte in the Austrian state of Tyrol.

Geography

Ehrwald lies at the southern base of the Zugspitze (2950 meters above sea level), Germany's highest mountain, but which is shared with Austria. The tow ...

. To the west the Zugspitze massif drops into the valley of the River Loisach, which flows around the massif towards the northeast in a curve whilst, in the east, the streams of ''Hammersbach'' and Partnach

The Partnach is an mountain river in Bavaria, Germany.

It rises at a height of on the Zugspitze Massif. The Partnach is fed by meltwaters from the Schneeferner glacier some higher up. The glacier's meltwaters seep into the karsty bedrock an ...

have their source. To the south the ''Gaistal'' valley and its river, the Leutascher Ache, separate the Wetterstein Mountains from the Mieming Chain. To the north at the foot of the Zugspitze is the lake of Eibsee. The next highest mountain in the area is the Acherkogel () in the Stubai Alps

The Stubai Alps (in German ''Stubaier Alpen'') is a mountain range in the Central Eastern Alps of Europe. It derives its name from the Stubaital valley to its east and is located southwest of Innsbruck, Austria. Several peaks form the border betwe ...

, which gives the Zugspitze a topographic isolation

The topographic isolation of a summit is the minimum distance to a point of equal elevation, representing a radius of dominance in which the peak is the highest point. It can be calculated for small hills and islands as well as for major mountain ...

value of 24.6 kilometres. The reference point for the prominence

In topography, prominence (also referred to as autonomous height, relative height, and shoulder drop in US English, and drop or relative height in British English) measures the height of a mountain or hill's summit relative to the lowest contou ...

is the Parseierspitze

Parseierspitze is, at tall, the highest mountain and the only three-thousander of the Northern Limestone Alps. It is the main peak of the Lechtal Alps, located in the Austrian state of Tyrol, northwest of Landeck.

Geography

The summit consists ...

(). In order to climb it from the Zugspitze, a descent to the Fern Pass

Fern Pass (elevation 1212 m) is a mountain pass in the Tyrolean Alps in Austria. It is located between the Lechtal Alps on the west and the Mieming Mountains on the east. The highest peak in Germany, the Zugspitze is only 13.5 km away to th ...

() is required, so that the prominence is .

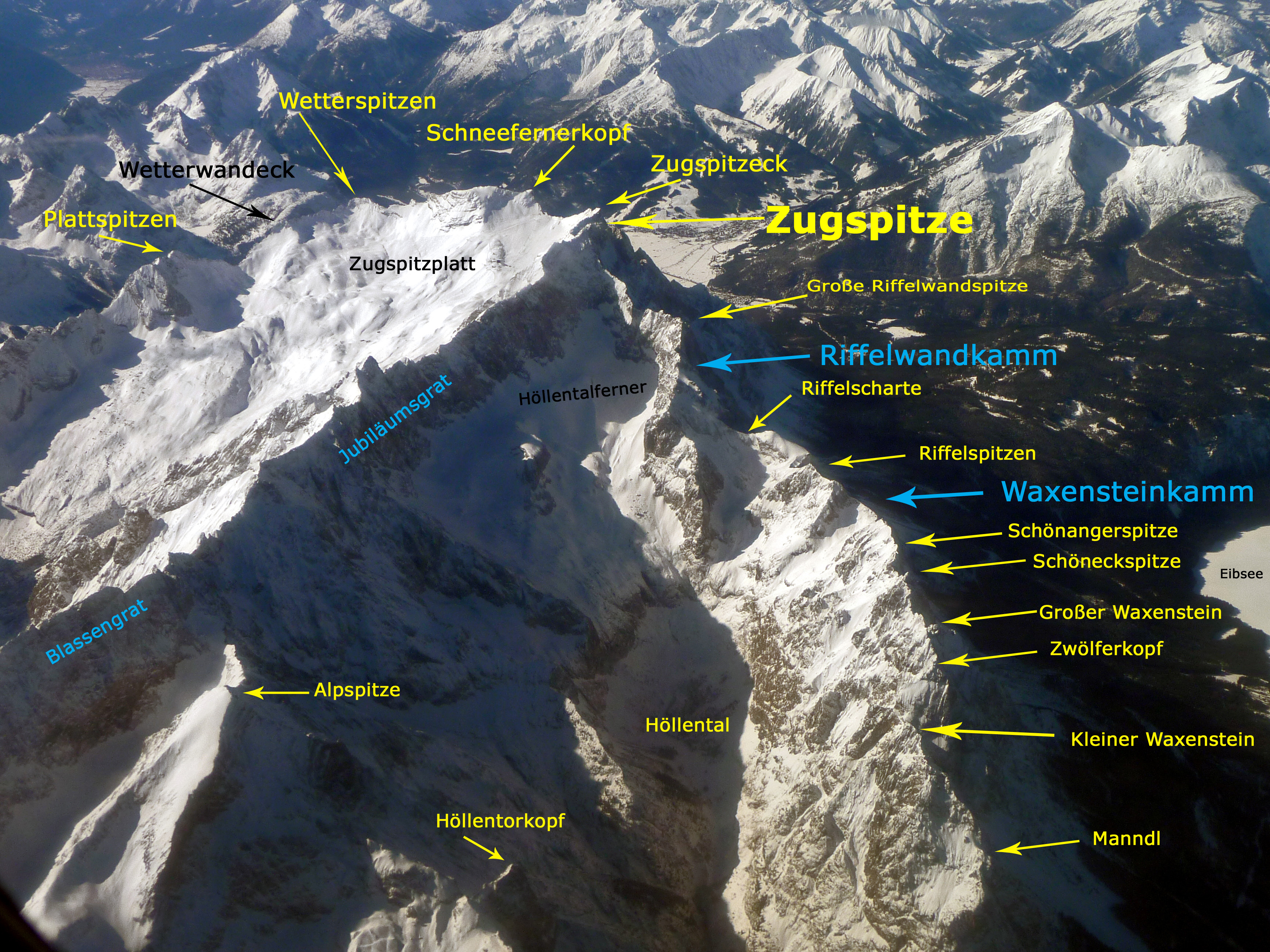

;Zugspitze Massif

massif

In geology, a massif ( or ) is a section of a planet's crust that is demarcated by faults or flexures. In the movement of the crust, a massif tends to retain its internal structure while being displaced as a whole. The term also refers to a ...

of the Zugspitze has several other peaks. To the south the ''Zugspitzplatt'' is surrounded in an arc by the ''Zugspitzeck'' () and Schneefernerkopf

The Schneefernerkopf is a peak in the Zugspitze massif in the Alps. It lies at the western end of the Wetterstein chain in the Alps on the border between the German state of Bavaria and the Austrian state of Tyrol. It is the dominant mountain in ...

(), the Wetterspitzen (), the Wetterwandeck (), the Plattspitzen

The Plattspitzen is a mountain in the Wetterstein Mountains on the border between Germany and Austria. It is a very striking mountain and the southern companion of Germany's highest peak, the Zugspitze, located at the opposite end of the ledge kn ...

() and the ''Gatterlköpfen'' (). The massif ends in the ''Gatterl'' (), a wind gap

A wind gap (or air gap) is a gap through which a waterway once flowed that is now dry as a result of stream capture. A water gap is a similar feature, but one in which a waterway still flows. Water gaps and wind gaps often provide routes which ...

between it and the Hochwanner

__NOTOC__

At , the Hochwanner (formerly: ''Kothbachspitze'') is the second highest mountain in Germany

at en.tixik.com. Accessed on 10 Feb 20 ...

. Running eastwards away from the Zugspitze is the famous Jubilee Ridge or ''Jubiläumsgrat'' over the Höllentalspitzen towards the at en.tixik.com. Accessed on 10 Feb 20 ...

Alpspitze

The Alpspitze is a mountain, 2628 m, in Bavaria, Germany. Its pyramidal peak is the symbol of Garmisch-Partenkirchen and is one of the best known and most attractive mountains of the Northern Limestone Alps. It is made predominantly of Wetter ...

and Hochblassen

The Hochblassen is a mountain high, located in the Wetterstein in the German state of Bavaria. In addition to the main summit, it has a sub-peak, the so-called ''Signalgipfel'' ("signal peak") which is high. It was first climbed in 1871 by Herma ...

. The short crest of the ''Riffelwandkamm'' runs northeast over the summits of the Riffelwandspitzen () and the ''Riffelköpfe'' (), to the Riffel wind gap (''Riffelscharte'', ). From here the ridge of the ''Waxensteinkamm'' stretches away over the Riffelspitzen to the Waxenstein

Waxenstein is a mountain of Bavaria, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state ...

.''Alpine Club Map

Alpine Club maps (german: Alpenvereinskarten, often abbreviated to ''AV-Karten'' i.e. AV maps) are specially detailed maps for summer and winter mountain climbers (mountaineers, hikers and ski tourers). They are predominantly published at a scale o ...

4/2 – Wetterstein und Mieminger Gebirge Mitte'' (1:25,000). 5th edition. Alpenvereinsverlag, Munich, 2007.

;Zugspitzplatt

The ''Platt'' or ''Zugspitzplatt'' is a

The ''Platt'' or ''Zugspitzplatt'' is a plateau

In geology and physical geography, a plateau (; ; ), also called a high plain or a tableland, is an area of a highland consisting of flat terrain that is raised sharply above the surrounding area on at least one side. Often one or more sides ha ...

below the summit of the Zugspitze to the south and southeast which lies at a height of between . It forms the head of the Reintal valley and has been shaped by a combination of weathering

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with water, atmospheric gases, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs ''in situ'' (on site, with little or no movement), ...

, karst

Karst is a topography formed from the dissolution of soluble rocks such as limestone, dolomite, and gypsum. It is characterized by underground drainage systems with sinkholes and caves. It has also been documented for more weathering-resistant ro ...

ification and glaciation

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

. The area contains roches moutonnées, dolines and limestone pavement

A limestone pavement is a natural karst landform consisting of a flat, incised surface of exposed limestone that resembles an artificial pavement. The term is mainly used in the UK and Ireland, where many of these landforms have developed dis ...

s as a consequence of the ice age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gree ...

s. In addition moraine

A moraine is any accumulation of unconsolidated debris (regolith and rock), sometimes referred to as glacial till, that occurs in both currently and formerly glaciated regions, and that has been previously carried along by a glacier or ice shee ...

s have been left behind by various glacial period

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betwe ...

s. The ''Platt'' was completely covered by a glacier for the last time at the beginning of the 19th century. Today 52% of it consists of scree

Scree is a collection of broken rock fragments at the base of a cliff or other steep rocky mass that has accumulated through periodic rockfall. Landforms associated with these materials are often called talus deposits. Talus deposits typically ha ...

, 32% of bedrock

In geology, bedrock is solid Rock (geology), rock that lies under loose material (regolith) within the crust (geology), crust of Earth or another terrestrial planet.

Definition

Bedrock is the solid rock that underlies looser surface mater ...

and 16% of vegetation-covered soils, especially in the middle and lower areas.

Climate

The climate istundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless moun ...

(Köppen Köppen is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Bernd Köppen (born 1951), German pianist and composer

* Carl Köppen (1833-1907), German military advisor in Meiji era Japan

* Edlef Köppen (1893–1939), German author and ...

: ''ET''), maintaining the only glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

present in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, which has observed its reduction over the years. From a climatic perspective the Zugspitze lies in the temperate zone

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

and its prevailing winds are Westerlies

The westerlies, anti-trades, or prevailing westerlies, are prevailing winds from the west toward the east in the middle latitudes between 30 and 60 degrees latitude. They originate from the high-pressure areas in the horse latitudes and trend to ...

. As the first high orographic obstacle to these Westerlies in the Alps, the Zugspitze is particularly exposed to the weather. It is effectively the north barrier of the Alps (''Nordstau der Alpen''), against which moist air masses pile up and release heavy precipitation. At the same time the Zugspitze acts as a protective barrier for the Alpine ranges to the south. By contrast, Föhn

A Foehn or Föhn (, , ), is a type of dry, relatively warm, downslope wind that occurs in the leeward, lee (downwind side) of a mountain range.

It is a rain shadow wind that results from the subsequent adiabatic warming of air that has dropped m ...

weather conditions push in the other direction against the massif, affecting the region for about 60 days per year. These warm, dry air masses stream from south to north and can result in unusually high temperatures in winter. Nevertheless, frost dominates the picture on the Zugspitze with an average of 310 days per year.

World Meteorological Organization

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for promoting international cooperation on atmospheric science, climatology, hydrology and geophysics.

The WMO originated from the Internati ...

as the "normal period" – the average annual precipitation on the Zugspitze was 2,003.1 mm; the wettest month being April with 199 mm, and the driest, October with 108.8 mm. By comparison the values for 2009 were 2,070.8 mm, the wettest month being March with 326.2 mm and the driest, January, with 56.4 mm. The average temperature in the normal period was −4.8 Celsius, with July and August being the warmest at 2.2 °C and February, the coldest, with −11.4 °C. By comparison the average temperature in 2009 was −4.2 °C, the warmest month was August at 5.3 °C and the coldest was February at −13.5 °C. The average sunshine during the normal period was 1,846.3 hours per year, the sunniest month being October with 188.8 hours and the darkest being December with 116.1 hours. In 2009 there were 1,836.3 hours of sunshine, the least occurring in February with just 95.4 hours and the most in April with 219 hours. In 2009, according to the weather survey by the German Met Office

The () or DWD for short, is the German Meteorological Service, based in Offenbach am Main, Germany, which monitors weather and meteorological conditions over Germany and provides weather services for the general public and for nautical, aviati ...

, the Zugspitze was the coldest place in Germany with a mean annual temperature of −4.2 °C.

The lowest measured temperature on the Zugspitze was −35.6 °C on 14 February 1940. The highest temperature occurred on 5 July 1957 when the thermometer reached 17.9 °C. A squall

A squall is a sudden, sharp increase in wind speed lasting minutes, as opposed to a wind gust, which lasts for only seconds. They are usually associated with active weather, such as rain showers, thunderstorms, or heavy snow. Squalls refer to the ...

on 12 June 1985 registered 335 km/h, the highest measured wind speed on the Zugspitze. In April 1944 meteorologists recorded a snow depth of 8.3 metres. Ritschel & Dauer (2007), p. 75ff.

Nowadays, snow completely melts during summer, but in the past snow might resist the summer months, the last case when the snow failed to melt during the whole summer season was in 2000.

Geology

The

The geological strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum (plural, : strata) is a layer of Rock (geology), rock or sediment characterized by certain Lithology, lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separate ...

composing the mountain are sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles ...

s of the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceo ...

era, that were originally laid down on the seabed. The base of the mountain comprises muschelkalk

The Muschelkalk (German for "shell-bearing limestone"; french: calcaire coquillier) is a sequence of sedimentary rock strata (a lithostratigraphic unit) in the geology of central and western Europe. It has a Middle Triassic (240 to 230 million ye ...

beds; its upper layers are made of Wetterstein limestone

The Wetterstein Formation is a regional geologic formation of the Northern Limestone Alps and Western Carpathians extending from southern Bavaria, Germany in the west, through northern Austria to northern Hungary and western Slovakia in the east. ...

. With steep rock walls up to 800 metres high, it is this Wetterstein limestone from the Upper Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

that is mainly responsible for the rock faces, arêtes, pinnacles and the summit rocks of the mountain. Due to the frequent occurrence of marine coralline alga

Coralline algae are red algae in the order Corallinales. They are characterized by a thallus that is hard because of calcareous deposits contained within the cell walls. The colors of these algae are most typically pink, or some other shade of ...

e in the Wetterstein limestone it can be deduced that this rock was at one time formed in a lagoon. The colour of the rock varies between grey-white and light grey to speckled. In several places it contains lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

and zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodi ...

ore. These mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. ( ...

s were mined between 1827 and 1918 in the Höllental valley. The dark grey, almost horizontal and partly grass-covered layers of muschelkalk run from the foot of the Great Riffelwandspitze to the Ehrwalder Köpfe. From the appearance of the north face of the Zugspitze it can be seen that this massif originally consisted of two mountain ranges that were piled on top of one another.

Flora

The flora on the Zugspitze is not particularly diverse due to the soil conditions, nevertheless the vegetation, especially in the meadows of ''Schachen'', the ''Tieferen Wies'' near Ehrwald, and in the valleys of Höllental, Gaistal and Leutaschtal is especially colourful. The shaded and moist northern slopes of the massif like, for example, the Wettersteinwald, are some of the most species-rich environments on the Zugspitze. The

The shaded and moist northern slopes of the massif like, for example, the Wettersteinwald, are some of the most species-rich environments on the Zugspitze. The mountain pine

''Pinus mugo'', known as bog pine, creeping pine, dwarf mountain pine, mugo pine, mountain pine, scrub mountain pine, or Swiss mountain pine, is a species of conifer, native to high elevation habitats from southwestern to Central Europe and S ...

grows at elevations of up to 1,800 metres. The woods lower down consist mainly of spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal (taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the subfami ...

and fir, but honeysuckle

Honeysuckles are arching shrubs or twining vines in the genus ''Lonicera'' () of the family Caprifoliaceae, native to northern latitudes in North America and Eurasia. Approximately 180 species of honeysuckle have been identified in both conti ...

, woodruff, poisonous herb paris, meadow-rue and speedwell also occur here. Dark columbine, alpine clematis

''Clematis alpina'', the Alpine clematis, is a flowering deciduous vine of the genus ''Clematis''. Like many members of that genus, it is prized by gardeners for its showy flowers. It bears 1 to 3-inch spring flowers on long stalks in a wide va ...

, blue and yellow monkshood

''Aconitum'' (), also known as aconite, monkshood, wolf's-bane, leopard's bane, mousebane, women's bane, devil's helmet, queen of poisons, or blue rocket, is a genus of over 250 species of flowering plants belonging to the family Ranunculaceae. ...

, stemless carline thistle

''Carlina acaulis'', the stemless carline thistle, dwarf carline thistle, or silver thistle, is a perennial dicotyledonous flowering plant in the family Asteraceae, native to alpine regions of central and southern Europe.

The specific name ''aca ...

, false aster, golden cinquefoil, round-leaved saxifrage, wall hawkweed, alpine calamint and alpine forget-me-not flower in the less densely wooded places, whilst cinquefoil

''Potentilla'' is a genus containing over 300Guillén, A., et al. (2005)Reproductive biology of the Iberian species of ''Potentilla'' L. (Rosaceae).''Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid'' 1(62) 9–21. species of annual, biennial and perenn ...

, sticky sage, butterbur

''Petasites'' is a genus of flowering plants in the sunflower family, Asteraceae, that are commonly referred to as butterburs and coltsfoots.alpenrose

''Rhododendron ferrugineum'', the alpenrose, snow-rose, or rusty-leaved alpenrose is an evergreen shrub that grows just above the tree line in the Alps, Pyrenees, Jura and northern Apennines, on acid soils. It is the type species for the genus ...

, Turk's cap lily Turk's cap lily is a common name for several plants and may refer to:

* ''Lilium martagon

''Lilium martagon'', the martagon lily or Turk's cap lily, is a Eurasian species of lily. It has a widespread native region extending from Portugal east t ...

and fly orchid thrive on the rocky soils of the mountain forests. Lily of the valley

Lily of the valley (''Convallaria majalis'' (), sometimes written lily-of-the-valley, is a woodland flowering plant with sweetly scented, pendent, bell-shaped white flowers borne in sprays in spring. It is native throughout the cool temperate No ...

and daphne

Daphne (; ; el, Δάφνη, , ), a minor figure in Greek mythology, is a naiad, a variety of female nymph associated with fountains, wells, springs, streams, brooks and other bodies of freshwater.

There are several versions of the myth in whi ...

also occur, especially in the Höllental, in Grainau and by the Eibsee.

To the south the scene changes to larch

Larches are deciduous conifers in the genus ''Larix'', of the family Pinaceae (subfamily Laricoideae). Growing from tall, they are native to much of the cooler temperate northern hemisphere, on lowlands in the north and high on mountains furt ...

(mainly in the meadow of ''Ehrwalder Alm'' and the valleys of Gaistal and Leutaschtal) and pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden accep ...

forests and into mixed woods of beech

Beech (''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to temperate Europe, Asia, and North America. Recent classifications recognize 10 to 13 species in two distinct subgenera, ''Engleriana'' and ''Fagus''. The ''Engle ...

and sycamore

Sycamore is a name which has been applied to several types of trees, but with somewhat similar leaf forms. The name derives from the ancient Greek ' (''sūkomoros'') meaning "fig-mulberry".

Species of trees known as sycamore:

* ''Acer pseudoplata ...

. Here too, mountain pine grows at the higher elevations of over 2,000 metres.

Relatively rare in the entire Zugspitze area are trees like the lime

Lime commonly refers to:

* Lime (fruit), a green citrus fruit

* Lime (material), inorganic materials containing calcium, usually calcium oxide or calcium hydroxide

* Lime (color), a color between yellow and green

Lime may also refer to:

Botany ...

, birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech-oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 30 ...

, rowan

The rowans ( or ) or mountain-ashes are shrubs or trees in the genus ''Sorbus

''Sorbus'' is a genus of over 100 species of trees and shrubs in the rose family, Rosaceae. Species of ''Sorbus'' (''s.l.'') are commonly known as whitebeam, r ...

, juniper

Junipers are coniferous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Juniperus'' () of the cypress family Cupressaceae. Depending on the taxonomy, between 50 and 67 species of junipers are widely distributed throughout the Northern Hemisphere, from the Arcti ...

and yew. The most varied species of moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic division Bryophyta (, ) '' sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryophytes, which comprise liverworts, mosses, and hor ...

, that often completely cover limestone rocks in the open, occur in great numbers.

Bilberry

Bilberries (), or sometimes European blueberries, are a primarily Eurasian species of low-growing shrubs in the genus ''Vaccinium'' (family Ericaceae), bearing edible, dark blue berries. The species most often referred to is '' Vaccinium myrtill ...

, cranberry

Cranberries are a group of evergreen dwarf shrubs or trailing vines in the subgenus ''Oxycoccus'' of the genus '' Vaccinium''. In Britain, cranberry may refer to the native species '' Vaccinium oxycoccos'', while in North America, cranberry ...

and cowberry are restricted to dry places and lady's slipper orchid

Cypripedioideae is a subfamily of orchids commonly known as lady's slipper orchids, lady slipper orchids or slipper orchids. Cypripedioideae includes the genera ''Cypripedium, Mexipedium, Paphiopedilum, Phragmipedium'' and ''Selenipedium''. The ...

occurs in sheltered spots. Below the Waxenstein

Waxenstein is a mountain of Bavaria, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state ...

are fields with raspberries

The raspberry is the edible fruit of a multitude of plant species in the genus ''Rubus'' of the rose family, most of which are in the subgenus '' Idaeobatus''. The name also applies to these plants themselves. Raspberries are perennial with ...

and occasionally wild strawberries too. The alpine poppy and purple mountain saxifrage both thrive up to a very great height. On the scree slopes there are penny-cress and mouse-ear chickweed as well as mountain avens

''Dryas octopetala'', the mountain avens, eightpetal mountain-avens, white dryas or white dryad, is an Arctic–alpine flowering plant in the family Rosaceae. It is a small prostrate evergreen subshrub forming large colonies. The specific epit ...

, alpine toadflax, mint

MiNT is Now TOS (MiNT) is a free software alternative operating system kernel for the Atari ST system and its successors. It is a multi-tasking alternative to TOS and MagiC. Together with the free system components fVDI device drivers, XaA ...

and . Following snowmelt dark stonecrop and snow gentian are the first to appear, their seeds beginning to germinate as early as August. Other well-known alpine plants like edelweiss

EDELWEISS (Expérience pour DEtecter Les WIMPs En Site Souterrain) is a dark matter search experiment located at the Modane Underground Laboratory in France. The experiment uses cryogenic detectors, measuring both the phonon and ionization signal ...

, gentian

''Gentiana'' is a genus of flowering plants belonging to the gentian family (Gentianaceae), the tribe Gentianeae, and the monophyletic subtribe Gentianinae. With about 400 species it is considered a large genus. They are notable for their mostl ...

s and, more rarely, cyclamen

''Cyclamen'' ( or ) is a genus of 23 species of perennial flowering plants in the family Primulaceae. ''Cyclamen'' species are native to Europe and the Mediterranean Basin east to the Caucasus and Iran, with one species in Somalia. They gro ...

also flower on the Zugspitze.

Fauna

The rocks around the Zugspitze are a habitat for

The rocks around the Zugspitze are a habitat for chamois

The chamois (''Rupicapra rupicapra'') or Alpine chamois is a species of goat-antelope native to mountains in Europe, from west to east, including the Alps, the Dinarides, the Tatra and the Carpathian Mountains, the Balkan Mountains, the Ril ...

, whilst marmot

Marmots are large ground squirrels in the genus ''Marmota'', with 15 species living in Asia, Europe, and North America. These herbivores are active during the summer, when they can often be found in groups, but are not seen during the winter, ...

s are widespread on the southern side of the massif. At the summit there are frequently alpine chough

The Alpine chough (), or yellow-billed chough (''Pyrrhocorax graculus'') is a bird in the crow family, one of only two species in the genus '' Pyrrhocorax''. Its two subspecies breed in high mountains from Spain eastwards through southern Europ ...

s, drawn there by people feeding them. Somewhat lower down the mountain there are mountain hare

The mountain hare (''Lepus timidus''), also known as blue hare, tundra hare, variable hare, white hare, snow hare, alpine hare, and Irish hare, is a Palearctic hare that is largely adapted to polar and mountainous habitats.

Evolution

The mount ...

and the hazel dormouse

The hazel dormouse or common dormouse (''Muscardinus avellanarius'') is a small mammal and the only living species in the genus ''Muscardinus''.

Distribution and habitat

The hazel dormouse is native to northern Europe and Asia Minor. It is the ...

. Alpine birds occurring on the Zugspitze include the golden eagle

The golden eagle (''Aquila chrysaetos'') is a bird of prey living in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, it belongs to the family Accipitridae. They are one of the best-known bird of p ...

, rock ptarmigan

The rock ptarmigan (''Lagopus muta'') is a medium-sized game bird in the grouse family. It is known simply as the ptarmigan in the UK. It is the official bird for the Canadian territory of Nunavut, where it is known as the ''aqiggiq'' (ᐊᕿ� ...

, snow finch Snowfinches are a group of small passerine birds in the sparrow family Passeridae. At one time all eight species were placed in the genus ''Montifringilla'' but they are now divided into three genera:

* ''Montifringilla'' (3 species)

** In Europe, ...

, alpine accentor

The alpine accentor (''Prunella collaris'') is a small passerine bird in the family Prunellidae, which is native to Eurasia and North Africa.

Taxonomy

The Alpine accentor was described by the Austria naturalist Giovanni Antonio Scopoli in 176 ...

and brambling

The brambling (''Fringilla montifringilla'') is a small passerine bird in the finch family Fringillidae. It has also been called the cock o' the north and the mountain finch. It is widespread and migratory, often seen in very large flocks.

Ta ...

. The crag martin

The crag martins are four species of small passerine birds in the genus ''Ptyonoprogne'' of the swallow family. They are the Eurasian crag martin (''P. rupestris''), the pale crag martin (''P. obsoleta''), the rock martin (''P. ...

which has given its name to the ''Schwalbenwand'' ("Swallows' Wall") at Kreuzeck is frequently encountered. The basins of Mittenwald and Seefeld, as well as the Fern Pass are on bird migration routes.

The viviparous lizard

The viviparous lizard, or common lizard, (''Zootoca vivipara'', formerly ''Lacerta vivipara''), is a Eurasian lizard. It lives farther north than any other species of non-marine reptile, and is named for the fact that it is viviparous, meaning ...

inhabits rocky terrain, as does the black alpine salamander

The alpine salamander (''Salamandra atra'') is a black salamander that can be found in the French Alps, and through the mountainous range in Europe. It is a member of the genus ''salamandra''. Their species name, ''atra'', may be derived from the ...

known locally as the ''Bergmandl'', which can be seen after rain showers as one is climbing. Butterflies like Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

, Thor's fritillary, gossamer-winged butterfly, geometer moth

The geometer moths are moths belonging to the family Geometridae of the insect order Lepidoptera, the moths and butterflies. Their scientific name derives from the Ancient Greek ''geo'' γεω (derivative form of or "the earth"), and ''metro ...

, ringlet

The ringlet (''Aphantopus hyperantus'') is a butterfly in the family Nymphalidae. It is only one of the numerous "ringlet" butterflies in the tribe Satyrini.

Range

The ringlet is a widely distributed species found throughout much of the Pale ...

and skipper may be seen on the west and south sides of the Zugspitze massif, especially in July and August. The woods around the Zugspitze are home to red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or hart, and a female is called a hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Iran, and parts of wes ...

, red squirrel

The red squirrel (''Sciurus vulgaris'') is a species of tree squirrel in the genus ''Sciurus'' common throughout Europe and Asia. The red squirrel is an arboreal, primarily herbivorous rodent.

In Great Britain, Ireland, and in Italy numbers ...

, weasel

Weasels are mammals of the genus ''Mustela'' of the family Mustelidae. The genus ''Mustela'' includes the least weasels, polecats, stoats, ferrets and European mink. Members of this genus are small, active predators, with long and slender bo ...

, capercaillie, hazel grouse

The hazel grouse (''Tetrastes bonasia''), sometimes called the hazel hen, is one of the smaller members of the grouse family of birds. It is a sedentary species, breeding across the Palearctic as far east as Hokkaido, and as far west as eastern a ...

and black grouse

The black grouse (''Lyrurus tetrix''), also known as northern black grouse, Eurasian black grouse, blackgame or blackcock, is a large game bird in the grouse family. It is a sedentary species, spanning across the Palearctic in moorland and step ...

. On the glaciers live glacier flea

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

s (''Desoria saltans'') and water bears.

Glaciers

Three of Germany's five glaciers are found on the Zugspitze massif: theHöllentalferner

The Höllentalferner is a glacier in the western Wetterstein Mountains. It is a cirque glacier that covers the upper part of the Höllental valley and its location in a rocky bowl between the Riffelwandspitzen and Germany's highest mountain, the ...

the Southern and Northern Schneeferner.

;Höllentalferner

cirque

A (; from the Latin word ') is an amphitheatre-like valley formed by glacial erosion. Alternative names for this landform are corrie (from Scottish Gaelic , meaning a pot or cauldron) and (; ). A cirque may also be a similarly shaped landform ...

below the Jubilee Ridge (''Jubiläumsgrat

The Jubiläumsgrat ("Jubilee Arête") or Jubiläumsweg ("Jubilee Way"), also nicknamed ''Jubi'' in climbing circles, is the name given to the climbing route along the arête between the Zugspitze (2,962 m) and the Hochblassen (2,706 m) (hence i ...

'') to the south and the Riffelwandspitzen peaks to the west and north. It has a northeast aspect

Aspect or Aspects may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Aspect magazine'', a biannual DVD magazine showcasing new media art

* Aspect Co., a Japanese video game company

* Aspects (band), a hip hop group from Bristol, England

* ''Aspects'' (Benny Carter ...

. Its accumulation zone is formed by a depression, in which large quantities of avalanche

An avalanche is a rapid flow of snow down a slope, such as a hill or mountain.

Avalanches can be set off spontaneously, by such factors as increased precipitation or snowpack weakening, or by external means such as humans, animals, and earth ...

snow collect. To the south the ''Jubiläumsgrat'' shields the glacier from direct sunshine. These conditions meant that the glacier only lost a relatively small area between 1981 and 2006. In recent times the Höllentalferner reached its greatest around 1820 with an area of 47 hectares

The hectare (; SI symbol: ha) is a non-SI metric unit of area equal to a square with 100-metre sides (1 hm2), or 10,000 m2, and is primarily used in the measurement of land. There are 100 hectares in one square kilometre. An acre is a ...

. Thereafter its area reduced continually until the period between 1950 and 1981 when it grew again, by 3.1 hectares to 30.2 hectares. Since then the glacier has lost (as at 2006) an area of 5.5 hectares and now has an area of 24.7 hectares. In 2006 the glacier head

A glacier head is the top of a glacier. Although glaciers seem motionless to the observer they are in constant motion and the terminus is always either advancing or retreating.

On a glacier, the accumulation zone is the area above the firn lin ...

was at 2,569 m and its lowest point at 2,203 metres.

;Schneeferner

Schneefernerkopf

The Schneefernerkopf is a peak in the Zugspitze massif in the Alps. It lies at the western end of the Wetterstein chain in the Alps on the border between the German state of Bavaria and the Austrian state of Tyrol. It is the dominant mountain in ...

, is the Northern Schneeferner which has an eastern aspect. With an area of 30.7 hectares (2006) it is the largest German glacier. Around 1820 the entire ''Zugspitzplatt'' was glaciated, but of this Platt Glacier (''Plattgletscher'') only the Northern and Southern Schneeferner remain. The reason for the relatively constant area of the Northern Schneeferner in recent years, despite the lack of shade, is the favourable terrain

Terrain or relief (also topographical relief) involves the vertical and horizontal dimensions of land surface. The term bathymetry is used to describe underwater relief, while hypsometry studies terrain relative to sea level. The Latin word ...

that results in the glacier tending to grow or shrink in depth rather than area. In the recent past the glacier has also been artificially fed by the ski region operators, using piste tractors to heap large quantities of snow onto the glacier in order to extend the skiing season.

At the beginning of the 1990s, ski slope operators began to cover the Northern Schneeferner in summer with artificial sheets in order to protect it from sunshine. The Northern Schneeferner reached its last high point in 1979, when its area grew to 40.9 hectares. By 2006 it had shrunk to 30.7 hectares. The glacier head then lay at 2,789 m and the foot at 2,558 metres.

The Southern Schneeferner is surrounded by the peaks of the Wetterspitzen and the Wetterwandeck. It is also a remnant of the once great ''Platt Glacier''. Today, the Southern Schneeferner extends up as far as the arête

An arête ( ) is a narrow ridge of rock which separates two valleys. It is typically formed when two glaciers erode parallel U-shaped valleys. Arêtes can also form when two glacial cirques erode headwards towards one another, although frequen ...

and therefore has no protection from direct sunshine. It has also been divided into two basins by a ridge of rock that has appeared as the snow has receded. It is a matter of debate whether the Southern Schneeferner should still be classified as a glacier. The Southern Schneeferner also reached its last high point in 1979, when it covered an area of 31.7 hectares. This had shrunk by 2006 to just 8.4 hectares however. The highest point of the glacier lies at an elevation of 2,665 metres and the lowest at 2,520 metres.

Caves

Below the ''Zugspitzplatt''chemical weathering

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with water, atmospheric gases, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs ''in situ'' (on site, with little or no movement ...

processes have created a large number of cave

A cave or cavern is a natural void in the ground, specifically a space large enough for a human to enter. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. The word ''cave'' can refer to smaller openings such as sea ...

s and abîme

In geography, an abîme is a vertical shaft in karst terrain that may be very deep and usually opens into a network of subterranean passages.Whittow, John (1984). ''Dictionary of Physical Geography'’. London: Penguin, 1984, p. 11. . The term is b ...

s in the Wetterstein limestone. In the 1930s the number of caves was estimated at 300. By 1955 62 caves were known to exist and by 1960 another 47 had been discovered. The first cave explorations here took place in 1931. Other, largest exploratory expeditions took place in 1935 and 1936 as well as between 1955 and 1968. During one expedition, in 1958, the Finch Shaft (''Finkenschacht'') was discovered. It is 131 metres deep, 260 metres long and has a watercourse. There is a theory that this watercourse could be a link to the source

Source may refer to:

Research

* Historical document

* Historical source

* Source (intelligence) or sub source, typically a confidential provider of non open-source intelligence

* Source (journalism), a person, publication, publishing institute o ...

of the River Partnach

The Partnach is an mountain river in Bavaria, Germany.

It rises at a height of on the Zugspitze Massif. The Partnach is fed by meltwaters from the Schneeferner glacier some higher up. The glacier's meltwaters seep into the karsty bedrock an ...

.According to this theory there is a lake underneath the ''Zugspitzplatt'' that feeds the Partnach. Calculations show that the ''Platt'' produces 350 litres of water per second; the source of the Partnach however delivers at least 500 (and possibly up to several thousand litres). The difference is put down to a cave lake that also supplies the Partnach.

Name

From the early 14th century, geographic names from the Wetterstein Mountains began to be recorded in treaties and on maps, and this trend intensified in the 15th century. In 1536 a border treaty dating to 1500 was refined in that its course was specified as running over a ''Schartten'' ("wind gap" or "col"). In the 17th century the reference to this landmark in the treaty was further clarified as ''"now known as the Zugspüz"'' (''jetzt Zugspüz genant''). The landmark referred to was a wind gap on the summit of the Zugspitze and is used time and again in other sources. During theMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

''Scharte'' was a common name for the Zugspitze.

The Zugspitze was first mentioned by name in 1590. In a description of the border between the County of Werdenfels The County of Werdenfels (German: ''Grafschaft Werdenfels'') in the present-day Werdenfelser Land in South Germany was a county that enjoyed imperial immediacy that belonged to the Bishopric of Freising from the late 13th century until the secularis ...

and Austria, it states that the same border runs ''"from the Zugspitz and over the Derle"'' (''von dem Zugspitz und über den Derle"'') and continues to a bridge over the River Loisach. Another border treaty in 1656 states: ''"The highest Wetterstein or Zugspitz"'' (''"Der höchste Wetterstain oder Zugspitz"''). There is also a map dating to the second half of the 18th century that shows ''"the Reintal in the County of Werdenfels"''. It covers the Reintal valley from the Reintaler Hof to the ''Zugspitzplatt'' and shows prominent points in the surrounding area, details of tracks and roads and the use pasture use. This includes a track over the then much larger Schneeferner glacier to the summit region of the Zugspitze. However the map does not show any obvious route to the summit itself.

The name of the Zugspitze is probably derived from its ''Zugbahnen'' or avalanche paths. In winter avalanches sweep down from the upper slopes of the massif into the valley and leave behind characteristic avalanche remnants in the shape of rocks and scree.

Near the Eibsee lake there are several plots of land with the same root: ''Zug'', ''Zuggasse'', ''Zugstick'', ''Zugmösel'' or ''Zugwankel''. Until the 19th century the name ''der Zugspitz'' ( male gender) was commonplace. It was described as ''die Zugspitze'' ( female gender) for the first time on a map printed in 1836. The spelling ''Zugspitz'' is still used in the Bavarian dialect.

Summit cross

Since 1851 there has been a summit cross on the top of Zugspitze. The driving force behind the erection of a cross on the summit was the priest, Christoph Ott. He was a keen meteorologist and whilst observing conditions from the

Since 1851 there has been a summit cross on the top of Zugspitze. The driving force behind the erection of a cross on the summit was the priest, Christoph Ott. He was a keen meteorologist and whilst observing conditions from the Hoher Peißenberg

Hoher Peißenberg is a mountain of Bavaria, Germany.

Location

The standalone Hoher Peißenberg ("High mount Peißen") is located in the middle of the Pfaffenwinkel region, in the Bavarian Prealps, in the Weilheim-Schongau district. Its summit ...

mountain he saw the Zugspitze in the distance and was exercised by the fact that ''"the greatest prince of the Bavarian mountains raised its head into the blue air towards heaven, bare and unadorned, waiting for the moment when patriotic fervour and courageous determination would see that his head too was crowned with dignity."'' As a result, he organised an expedition from 11 to 13 August 1851 with the goal of erecting a summit cross on the Zugspitze. Twenty eight bearers were led through the gorge of the Partnachklamm

The Partnach Gorge (german: Partnachklamm) is a deep gorge that has been incised by a mountain stream, the Partnach, in the Reintal (Wetterstein), Reintal valley near the south German town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen. The gorge is long and, in pl ...

and the Reintal valley under the direction of forester, Karl Kiendl, up to the Zugspitze. The undertaking, which cost 610 Gulden and 37 Kreuzer

The Kreuzer (), in English usually kreutzer ( ), was a coin and unit of currency in the southern German states prior to the introduction of the German gold mark in 1871/73, and in Austria and Switzerland. After 1760 it was made of copper. In s ...

, was a success. As a result, a 28-piece, 14 foot high, gilded iron cross now stood on the West Summit. Ott himself did not climb the Zugspitze until 1854.

After 37 years the cross had to be taken down after suffering numerous lightning strikes; its support brackets were also badly damaged. In the winter of 1881–1882 it was therefore brought down into the valley and repaired. On 25 August 1882 seven mountain guides and 15 bearers took the cross back to the top. Because an accommodation shed had been built on the West Summit, the team placed the cross on the East Summit. There it remained for about 111 years, until it was removed again on 18 August 1993. This time the damage was not only caused by the weather, but also by American soldiers who used the cross as target practice in 1945, at the end of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Because the summit cross could no longer be repaired, a replica was made that was true to the original cross. After two months the rack railway carried the new cross on 12 October to the ''Zugspitzplatt'', from where it was flown to the summit by helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forward, backward and laterally. These attributes ...

. The new cross has a height of 4.88 metres. It was renovated and regilded in 2009 for 15,000 euros and, since 22 April 2009, has stood once again on the East Summit.

History

The first recorded ascent to the summit was accomplished by a team of land surveyors on 27 August 1820. The team was led by Lieutenant

The first recorded ascent to the summit was accomplished by a team of land surveyors on 27 August 1820. The team was led by Lieutenant Josef Naus

Josef Naus (1793–1871) was an officer and surveying technician, known for leading the first ascent of Germany's highest mountain, the Zugspitze. Variations of his name are Karl Naus or Joseph Naus.

Life and career

Naus was born on 29 August ...

, who was accompanied by two men named Maier and G. Deutschl. However, local people had conquered the peak over 50 years earlier, according to a 1770 map discovered by the Alpenverein.

In 1854, the northern part of the Zugspitze was given to Bavaria as a present by Emperor of Austria and Apostolic King of Hungary Franz Joseph I as a marriage present to his wife Princess Elisabeth ("Sissi"). Since then the Zugspitze is the highest mountain of Bavaria and later of Germany.

On 7 January 1882 the first successful winter assault on the Zugspitze was accomplished by F. Kilger, H. and J. Zametzer and H. Schwaiger.

Pilot, Frank Hailer, caused a stir on 19 March 1922, when he landed a plane with skids on the Schneeferner glacier. On 29 April 1927 Ernst Udet succeeded in taking off from the Schneeferner with a glider

Glider may refer to:

Aircraft and transport Aircraft

* Glider (aircraft), heavier-than-air aircraft primarily intended for unpowered flight

** Glider (sailplane), a rigid-winged glider aircraft with an undercarriage, used in the sport of glidin ...

; he landed at Lermoos

Lermoos is a municipality in the district of Reutte in the Austrian state of Tyrol.

It consists of two subdivisions: Unterdorf and Oberdorf.

Lermoos is most popular for its skiing and snowboarding in the winter and is very popular resort in th ...

after a 25-minute flight. The glider had been disassembled into individual parts and transported up the Zugspitze by cable car. In the winter of 1931/32, a post office was set up on the Zugspitze by the German Imperial Post Office or ''Reichspost

''Reichspost'' (; "Imperial Mail") was the name of the postal service of Germany from 1866 to 1945.

''Deutsche Reichspost''

Upon the out break of the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 and the break-up of the German Confederation in the Peace of ...

''. It still exists today in the ''Sonnalpin'' restaurant and has the postal address: ''82475 Zugspitze''. In 1931, four years after the first glider flight, the first balloon

A balloon is a flexible bag that can be inflated with a gas, such as helium, hydrogen, nitrous oxide, oxygen, and air. For special tasks, balloons can be filled with smoke, liquid water, granular media (e.g. sand, flour or rice), or light so ...

took off from the Zugspitze.

In April 1933, the mountain was occupied by 24 storm troopers, who hoisted a swastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍) is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly in various Eurasian, as well as some African and American cultures, now also widely recognized for its appropriation by the Nazi Party and by neo-Nazis. It ...

flag on top the tower on the weather station. A month later, SA and SS deployed on the Schneeferner in the shape of a swastika. On 20 April 1945 the US Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

dropped bombs on the Zugspitze that destroyed the valley station of the Tyrolean Zugspitze Railway and the hotel on the ridge. After the war the Allies seized the railway and Schneefernerhaus.

Shortly after World War II the

Shortly after World War II the US military

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six Military branch, service branches: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States N ...