Ziemie Odzyskane on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Recovered Territories or Regained Lands ( pl, Ziemie Odzyskane), also known as Western Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Zachodnie), and previously as Western and Northern Territories ( pl, Ziemie Zachodnie i Północne), Postulated Territories ( pl, Ziemie Postulowane) and Returning Territories ( pl, Ziemie Powracające), are the former eastern territories of Germany and the

The Recovered Territories or Regained Lands ( pl, Ziemie Odzyskane), also known as Western Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Zachodnie), and previously as Western and Northern Territories ( pl, Ziemie Zachodnie i Północne), Postulated Territories ( pl, Ziemie Postulowane) and Returning Territories ( pl, Ziemie Powracające), are the former eastern territories of Germany and the

Several different West Slavic tribes inhabited most of the area of present-day Poland from the 6th century. Duke

Several different West Slavic tribes inhabited most of the area of present-day Poland from the 6th century. Duke  Mieszko's son and successor, Duke Bolesław I Chrobry, upon the 1018

Mieszko's son and successor, Duke Bolesław I Chrobry, upon the 1018  By the time that Poland regained her independence in 1918, Polish activist Dr. Józef Frejlich was already claiming that the lands situated on the right bank of the

By the time that Poland regained her independence in 1918, Polish activist Dr. Józef Frejlich was already claiming that the lands situated on the right bank of the

The Pomeranian (Western Pomeranian) parts of the Recovered Territories came under Polish rule several times from the late 10th century on, when

The Pomeranian (Western Pomeranian) parts of the Recovered Territories came under Polish rule several times from the late 10th century on, when

The region of Pomerelia at the eastern end of Pomerania, including

The region of Pomerelia at the eastern end of Pomerania, including

The medieval Lubusz Land on both sides of the Oder River up to the

The medieval Lubusz Land on both sides of the Oder River up to the

A small part of northern Greater Poland around the town of Czaplinek was lost to

A small part of northern Greater Poland around the town of Czaplinek was lost to

Lower Silesia was one of the leading regions of medieval Poland. Wrocław was one of three main cities of the Medieval Polish Kingdom, according to the 12th-century chronicle ''

Lower Silesia was one of the leading regions of medieval Poland. Wrocław was one of three main cities of the Medieval Polish Kingdom, according to the 12th-century chronicle ''

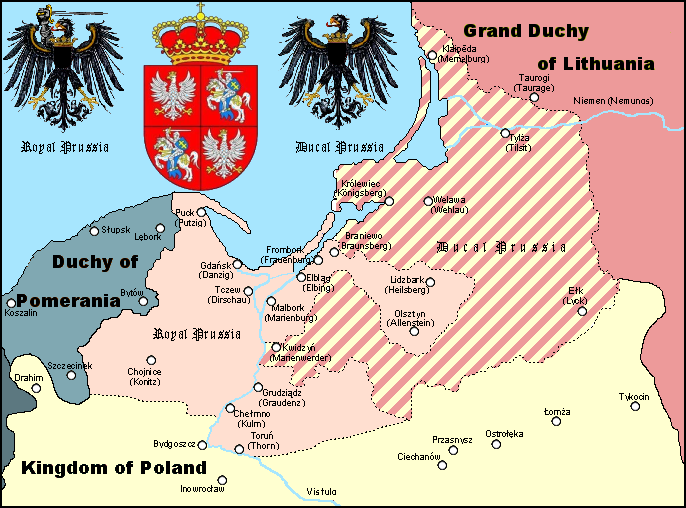

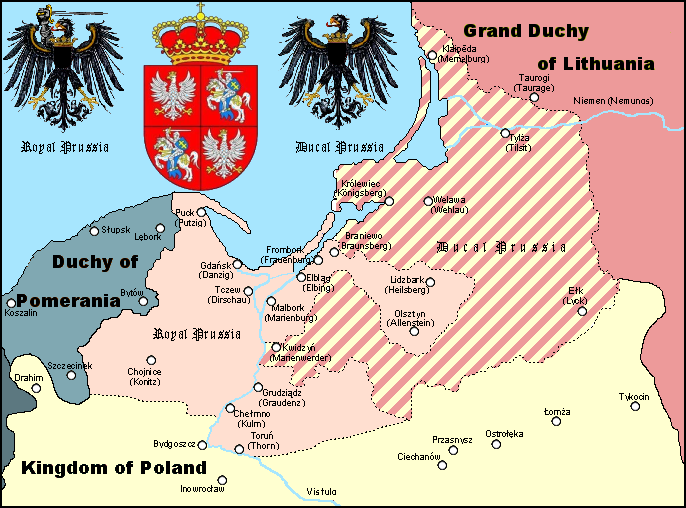

The territories of Warmia and Masuria were originally inhabited by pagan Old Prussians, until the conquest by the Teutonic Knights in the 13th and 14th centuries. In order to repopulate the conquered areas, Poles from neighboring Masovia, called Masurians (''Mazurzy''), were allowed to settle here (hence the name Masuria). During an uprising against the Teutonic Order most towns of the region joined or sided with the Prussian Confederation, at the request of which King Casimir IV Jagiellon signed the act of incorporation of the region into the Kingdom of Poland (1454). After the Second Peace of Thorn (1466) Warmia was confirmed to be incorporated to Poland, while Masuria became part of a Polish fief, first as part of the Teutonic state, and from 1525 as part of the secular Ducal Prussia. Then it would become one of the leading centers of Polish Lutheranism, while Warmia, under the administration of prince-bishops remained one of the most overwhelmingly Catholic regions of Poland.

Polish suzerainty over Masuria ended in 1657/1660 as a result of the Deluge and Warmia was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia in the First Partition of Poland (1772). Both regions formed the southern part of the province of

The territories of Warmia and Masuria were originally inhabited by pagan Old Prussians, until the conquest by the Teutonic Knights in the 13th and 14th centuries. In order to repopulate the conquered areas, Poles from neighboring Masovia, called Masurians (''Mazurzy''), were allowed to settle here (hence the name Masuria). During an uprising against the Teutonic Order most towns of the region joined or sided with the Prussian Confederation, at the request of which King Casimir IV Jagiellon signed the act of incorporation of the region into the Kingdom of Poland (1454). After the Second Peace of Thorn (1466) Warmia was confirmed to be incorporated to Poland, while Masuria became part of a Polish fief, first as part of the Teutonic state, and from 1525 as part of the secular Ducal Prussia. Then it would become one of the leading centers of Polish Lutheranism, while Warmia, under the administration of prince-bishops remained one of the most overwhelmingly Catholic regions of Poland.

Polish suzerainty over Masuria ended in 1657/1660 as a result of the Deluge and Warmia was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia in the First Partition of Poland (1772). Both regions formed the southern part of the province of

The term "Recovered Territories" was officially used for the first time in the Decree of the President of the Republic of 11 October 1938 after the annexation of Zaolzie by the Polish army. It became the official termAn explanation note i

The term "Recovered Territories" was officially used for the first time in the Decree of the President of the Republic of 11 October 1938 after the annexation of Zaolzie by the Polish army. It became the official termAn explanation note i

''"The Neighbors Respond: The Controversy Over the Jedwabne Massacre in Poland"''

, ed. by Polonsky and Michlic, p. 466 coined in the aftermath of World War II to denote the former eastern territories of Germany that were being handed over to Poland, pending a final peace conference with Germany which eventually never took place. The underlying concept was to define post-war Poland as heir to the medieval Piasts' realm,Joanna B. Michlic, ''Poland's Threatening Other: The Image of the Jew from 1880 to the Present'', 2006, pp. 207–208, , Norman Davies, ''God's Playground: A History of Poland in Two Volumes'', 2005, pp. 381ff, , Geoffrey Hosking, George Schopflin, ''Myths and Nationhood'', 1997, p. 153, , which was simplified into a picture of an ethnically homogeneous state that matched post-war borders,Jan Kubik, ''The Power of Symbols Against the Symbols of Power: The Rise of Solidarity and the Fall of State Socialism in Poland'', 1994, pp. 64–65, , as opposed to the later One reason for post-war Poland's favoring a Piast rather than a Jagiellon tradition was Joseph Stalin's refusal to withdraw from the Curzon line and the Allies' readiness to satisfy Poland with German territory instead.Rick Fawn, ''Ideology and national identity in post-communist foreign policies'', 2003, p. 190, , The original argument for awarding formerly German territory to Poland – compensation – was complemented by the argument that this territory in fact constituted former areas of Poland.Joanna B. Michlic, ''Poland's Threatening Other: The Image of the Jew from 1880 to the Present'', 2006, p. 208, , Jan Kubik, ''The Power of Symbols Against the Symbols of Power: The Rise of Solidarity and the Fall of State Socialism in Poland'', 1994, p. 65, , Dmitrow says that "in official justifications for the border shift, the decisive argument that it presented a compensation for the loss of the eastern half of the pre-war Polish territory to the USSR, was viewed as obnoxious and concealed. Instead, a historical argumentation was foregrounded with the dogma, Poland had just returned to 'ancient Piast lands'." Objections to the Allies' decisions and criticism of the Polish politicians' role at Potsdam were censored. In a commentary for Tribune,

One reason for post-war Poland's favoring a Piast rather than a Jagiellon tradition was Joseph Stalin's refusal to withdraw from the Curzon line and the Allies' readiness to satisfy Poland with German territory instead.Rick Fawn, ''Ideology and national identity in post-communist foreign policies'', 2003, p. 190, , The original argument for awarding formerly German territory to Poland – compensation – was complemented by the argument that this territory in fact constituted former areas of Poland.Joanna B. Michlic, ''Poland's Threatening Other: The Image of the Jew from 1880 to the Present'', 2006, p. 208, , Jan Kubik, ''The Power of Symbols Against the Symbols of Power: The Rise of Solidarity and the Fall of State Socialism in Poland'', 1994, p. 65, , Dmitrow says that "in official justifications for the border shift, the decisive argument that it presented a compensation for the loss of the eastern half of the pre-war Polish territory to the USSR, was viewed as obnoxious and concealed. Instead, a historical argumentation was foregrounded with the dogma, Poland had just returned to 'ancient Piast lands'." Objections to the Allies' decisions and criticism of the Polish politicians' role at Potsdam were censored. In a commentary for Tribune,

Google Print, p. 51

Wolff and Cordell say that along with the debunking of communist historiography, "the 'recovered territories' thesis ... has been discarded", and that "it is freely admitted in some circles that on the whole 'the recovered territories' had a wholly German character", but that this view has not necessarily been transmitted to the whole of Polish society.Karl Cordell, Stefan Wolff (2005)

''Germany's Foreign Policy Towards Poland and the Czech Republic: Ostpolitik Revisited''

. p. 139. , . "In addition ... it has been relatively easy for Polish historians and others to attempt to debunk communist historiography and present a more balanced analysis of the past – and not only with respect to Germany. It has been controversial, and often painful, but nevertheless it has been done. For example, Poland's acquisition in 1945 of eastern German territories is increasingly presented as the price Germany paid for launching a total war, and then having lost it totally. The 'recovered territories' thesis previously applied in almost equal measures by the communists and Catholic Church has been discarded. Some circles freely admit that on the whole, 'the recovered territories' in fact had a wholly German character. The extent to which this fact transmitted to groups other than the socially and politically engaged is a matter of debate." The term was also used outside Poland. In 1962, pope John XXIII referred to those territories as the "western lands after centuries recovered", and did not revise his statement, even under pressure of the German embassy. The term is still sometimes considered useful, due to the Polish existence in those lands that was still visible in 1945, by some prominent scholars, such as Krzysztof Kwaśniewski. After the Second World War, the Soviet Union annexed the Polish territories in the east, and encouraged or forced the Polish population from the region to move west. In the framework of the campaign, the Soviets put up posters in public places with messages that promised a better life in the West.

Since the time of the

Since the time of the

The People's Republic had to locate its population inside the new frontiers in order to solidify the hold over the territories. With the Kresy annexed by the Soviet Union, Poland was effectively moved westwards and its area reduced by almost 20% (from ). Millions of non-Poles – mainly Germans from the Recovered Territories, as well as some Ukrainians in the east – were to be expelled from the new Poland, while large numbers of Poles needed to be resettled having been expelled from the Kresy. The expellees were termed "repatriates". The result was the largest exchange of population in European history. The picture of the new western and northern territories being recovered Piast territory was used to forge Polish settlers and "repatriates" arriving there into a coherent community loyal to the new regime,Martin Åberg, Mikael Sandberg, ''Social Capital and Democratisation: Roots of Trust in Post-Communist Poland and Ukraine'', Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2003,

The People's Republic had to locate its population inside the new frontiers in order to solidify the hold over the territories. With the Kresy annexed by the Soviet Union, Poland was effectively moved westwards and its area reduced by almost 20% (from ). Millions of non-Poles – mainly Germans from the Recovered Territories, as well as some Ukrainians in the east – were to be expelled from the new Poland, while large numbers of Poles needed to be resettled having been expelled from the Kresy. The expellees were termed "repatriates". The result was the largest exchange of population in European history. The picture of the new western and northern territories being recovered Piast territory was used to forge Polish settlers and "repatriates" arriving there into a coherent community loyal to the new regime,Martin Åberg, Mikael Sandberg, ''Social Capital and Democratisation: Roots of Trust in Post-Communist Poland and Ukraine'', Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2003,

Google Print, p.79

and to justify the removal of the German inhabitants. Largely excepted from the

The "autochthons" not only disliked the subjective and often arbitrary verification process, but they also faced discrimination even after completing it, such as the Polonization of their names. In the Lubusz Voivodeship, Lubusz region (former

File:Oder-neisse.gif, Pre-1945 administrative division (yellow)

File:POLSKA 14-03-1945.png, Projected Polish administration (Okreg I-IV) in March, 1945

File:POLSKA 28-06-1946.png, Integration into the Voivodeships of Poland as of June, 1946

File:Northern and Western Territories.PNG, Present-day administrative division of Poland, Western and Northern Lands in dark green

The Communist authorities of the Polish People's Republic and some Polish citizens desired to erase all traces of German rule. The "Recovered Territories" after the transfer still contained a substantial German population. The Polish administration set up a "Ministry for the Recovered Territories", headed by the then deputy prime minister Władysław Gomułka.Karl Cordell, Andrzej Antoszewski, ''Poland and the European Union'', 2000, p.167, , A "Bureau for Repatriation" was to supervise and organize the expulsions and resettlements. According to the national census of 14 February 1946, the population of Poland still included 2,288,300 Germans, of which 2,036,439—nearly 89 per cent—lived in the ''Recovered Territories''. By this stage Germans still constituted more than 42 per cent of the inhabitants of these regions, since their total population according to the 1946 census was 4,822,075. However, by 1950 there were only 200,000 Germans remaining in Poland, and by 1957 that number fell to 65,000.

The flight and expulsion of the remaining Germans in the first post-war years presaged a broader campaign to remove signs of former German rule.

More than 30,000 German placenames were replaced with PolishDan Diner, Raphael Gross, Yfaat Weiss, ''Jüdische Geschichte als allgemeine Geschichte'', p.164 or Polonized medieval Slavic ones.Gregor Thum, ''Die fremde Stadt. Breslau nach 1945'', 2006, p.344, , Tomasz Kamusella and Terry Sullivan in Karl Cordell, ''Ethnicity and Democratisation in the New Europe'', 1999, pp.175ff, , Previous Slavic and Polish names used before German settlements had been established; in the cases when one was absent either the German name was translated or new names were invented. In January 1946, a

The Communist authorities of the Polish People's Republic and some Polish citizens desired to erase all traces of German rule. The "Recovered Territories" after the transfer still contained a substantial German population. The Polish administration set up a "Ministry for the Recovered Territories", headed by the then deputy prime minister Władysław Gomułka.Karl Cordell, Andrzej Antoszewski, ''Poland and the European Union'', 2000, p.167, , A "Bureau for Repatriation" was to supervise and organize the expulsions and resettlements. According to the national census of 14 February 1946, the population of Poland still included 2,288,300 Germans, of which 2,036,439—nearly 89 per cent—lived in the ''Recovered Territories''. By this stage Germans still constituted more than 42 per cent of the inhabitants of these regions, since their total population according to the 1946 census was 4,822,075. However, by 1950 there were only 200,000 Germans remaining in Poland, and by 1957 that number fell to 65,000.

The flight and expulsion of the remaining Germans in the first post-war years presaged a broader campaign to remove signs of former German rule.

More than 30,000 German placenames were replaced with PolishDan Diner, Raphael Gross, Yfaat Weiss, ''Jüdische Geschichte als allgemeine Geschichte'', p.164 or Polonized medieval Slavic ones.Gregor Thum, ''Die fremde Stadt. Breslau nach 1945'', 2006, p.344, , Tomasz Kamusella and Terry Sullivan in Karl Cordell, ''Ethnicity and Democratisation in the New Europe'', 1999, pp.175ff, , Previous Slavic and Polish names used before German settlements had been established; in the cases when one was absent either the German name was translated or new names were invented. In January 1946, a

According to the 1939 Nazi German census, the territories were inhabited by 8,855,000 people, including a Polish minority in the territories' easternmost parts. Piotr Eberhardt, Jan Owsinski, ''Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, Analysis'', 2003, pp.142ff, , However these data, concerning ethnic minorities, that came from the census conducted during the reign of the NSDAP (Nazi Party) is usually not considered by historians and demographers as trustworthy but as drastically falsified. Therefore, while this German census placed the number of Polish-speakers and bilinguals below 700,000 people, Polish demographers have estimated that the actual number of Poles in the former German East was between 1.2 and 1.3 million. In the 1.2 million figure, approximately 850,000 were estimated for the Upper Silesian regions, 350,000 for southern

According to the 1939 Nazi German census, the territories were inhabited by 8,855,000 people, including a Polish minority in the territories' easternmost parts. Piotr Eberhardt, Jan Owsinski, ''Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, Analysis'', 2003, pp.142ff, , However these data, concerning ethnic minorities, that came from the census conducted during the reign of the NSDAP (Nazi Party) is usually not considered by historians and demographers as trustworthy but as drastically falsified. Therefore, while this German census placed the number of Polish-speakers and bilinguals below 700,000 people, Polish demographers have estimated that the actual number of Poles in the former German East was between 1.2 and 1.3 million. In the 1.2 million figure, approximately 850,000 were estimated for the Upper Silesian regions, 350,000 for southern  Polish and Soviet newspapers and officials encouraged Poles to relocate to the west – "the land of opportunity". These new territories were described as a place where opulent villas abandoned by fleeing Germans waited for the brave; fully furnished houses and businesses were available for the taking. In fact, the areas were devastated by the war, the infrastructure largely destroyed, suffering high crime rates and looting by gangs. It took years for civil order to be established.

In 1970, the Polish population of the Northern and Western territories for the first time caught up to the pre-war population level (8,711,900 in 1970 vs 8,855,000 in 1939). In the same year, the population of the other Polish areas also reached its pre-war level (23,930,100 in 1970 vs 23,483,000 in 1939).

While the estimates of how many Germans remained vary, a constant German exodus took place even after the expulsions. Between 1956 and 1985, 407,000 people from Silesia and about 100,000 from Warmia-Masuria declared German nationality and left for Germany. In the early 1990s, after the Polish Communist regime had collapsed 300,000-350,000 people declared themselves German.

Today the population of the territories is predominantly Polish, although a small German minority still exists in a few places, including Olsztyn, Masuria, and Upper Silesia, particularly in Opole Voivodeship (the area of

Polish and Soviet newspapers and officials encouraged Poles to relocate to the west – "the land of opportunity". These new territories were described as a place where opulent villas abandoned by fleeing Germans waited for the brave; fully furnished houses and businesses were available for the taking. In fact, the areas were devastated by the war, the infrastructure largely destroyed, suffering high crime rates and looting by gangs. It took years for civil order to be established.

In 1970, the Polish population of the Northern and Western territories for the first time caught up to the pre-war population level (8,711,900 in 1970 vs 8,855,000 in 1939). In the same year, the population of the other Polish areas also reached its pre-war level (23,930,100 in 1970 vs 23,483,000 in 1939).

While the estimates of how many Germans remained vary, a constant German exodus took place even after the expulsions. Between 1956 and 1985, 407,000 people from Silesia and about 100,000 from Warmia-Masuria declared German nationality and left for Germany. In the early 1990s, after the Polish Communist regime had collapsed 300,000-350,000 people declared themselves German.

Today the population of the territories is predominantly Polish, although a small German minority still exists in a few places, including Olsztyn, Masuria, and Upper Silesia, particularly in Opole Voivodeship (the area of

During the

During the  Until the Treaty on the Final Settlement, the West German government regarded the status of the German territories east of the Oder-Neisse rivers as that of areas "temporarily under Polish or Soviet administration". To facilitate wide international acceptance of

Until the Treaty on the Final Settlement, the West German government regarded the status of the German territories east of the Oder-Neisse rivers as that of areas "temporarily under Polish or Soviet administration". To facilitate wide international acceptance of

Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (german: Freie Stadt Danzig; pl, Wolne Miasto Gdańsk; csb, Wòlny Gard Gduńsk) was a city-state under the protection of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gda ...

that became part of Poland after World War II, at which time their former German inhabitants were forcibly deported.

The rationale for the term "Recovered" was that these territories formed part of the Polish state, and were lost by Poland in different periods over the centuries. It also referred to the Piast Concept that these territories were part of the traditional Polish homeland under the Piast dynasty

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I (c. 930–992). The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of king Casimir III the Great.

Branch ...

, after the establishment of the state in the Middle Ages. Over the centuries, however, they had become predominantly German-speaking through the processes of German eastward settlement (), political expansion (), as well as language shift due to assimilation

Assimilation may refer to:

Culture

*Cultural assimilation, the process whereby a minority group gradually adapts to the customs and attitudes of the prevailing culture and customs

**Language shift, also known as language assimilation, the progre ...

(see also: ''Germanisation

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, German people, people and German culture, culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationa ...

'') of local Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

, Slavic and Baltic Prussian

Old Prussians, Baltic Prussians or simply Prussians ( Old Prussian: ''prūsai''; german: Pruzzen or ''Prußen''; la, Pruteni; lv, prūši; lt, prūsai; pl, Prusowie; csb, Prësowié) were an indigenous tribe among the Baltic peoples that ...

population. Therefore, aside from certain regions such as West Upper Silesia, Warmia and Masuria, as of 1945 most of these territories did not contain sizeable Polish-speaking communities.

While most regions had long periods of Polish rule, spanning hundreds of years, some were controlled by Polish dukes and kings for short periods of up to several decades at a time. Various regions, after losing power over them by Poland, were in different times under the authority of the Bohemian (Czech) Kingdom, Hungary, Austria, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, Denmark, Brandenburg, Prussia, and all of these territories to 1920/1945 were part of Germany. Many areas were also part of various Polish-ruled duchies, created as a result of the fragmentation of Poland, which began in the 12th century. The fact that some regions were located within the borders of Poland for a short time is used by opponents of the term to suggest that the argument of traditional Polish homeland is based rather on nationalistic ideas than on historical facts, although all these areas were at some point under Polish rule, and many regions have a rich Polish history.

The great majority of the previous inhabitants either fled

''Fled'' is a 1996 American buddy action comedy film directed by Kevin Hooks. It stars Laurence Fishburne and Stephen Baldwin as two prisoners chained together who flee during an escape attempt gone bad.

Plot

An interrogator prepares a man to ...

from the territories during the later stages of the war or were expelled by the Soviet and Polish communist authorities after the war ended, although a small German minority

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

remains in some places. The territories were resettled with Poles who moved from central Poland, Polish repatriates forced to leave areas of former eastern Poland that had been annexed by the Soviet Union, Poles freed from forced labour in Nazi Germany, with Ukrainians forcibly resettled under " Operation Vistula", and other minorities, which settled in post-war Poland, including Greeks and Macedonians.

However, contrary to the official declaration that the former German inhabitants of the Recovered Territories had to be removed quickly to house Poles displaced by the Soviet annexation, the Recovered Territories initially faced a severe population shortage. The Soviet-appointed communist authorities that conducted the resettlement also made efforts to remove many traces of German culture, such as place names and historic inscriptions on buildings, from the newly Polish territories.

The post-war border between Germany and Poland (the Oder–Neisse line) was recognized by East Germany in 1950 and by West Germany in 1970, and was affirmed by the re-united Germany in the German–Polish Border Treaty

The German–Polish Border Treaty of 1990; pl, Traktat między Rzeczpospolitą Polską a Republiką Federalną Niemiec o potwierdzeniu istniejącej między nimi granicy) finally settled the issue of the Polish–German border, which in terms ...

of 1990.

History before 1945

Mieszko I

Mieszko I (; – 25 May 992) was the first ruler of Poland and the founder of the first independent Polish state, the Duchy of Poland. His reign stretched from 960 to his death and he was a member of the Piast dynasty, a son of Siemomysł and ...

of the Polans Polans may refer to two Slavic tribes:

* Polans (eastern)

The Polans (, ''Poliany'', ''Polyane'', pl, Polanie), also Polianians, were an East Slavic tribe between the 6th and the 9th century, which inhabited both sides of the Dnieper river ...

, from his stronghold in the Gniezno area, united various neighboring tribes in the second half of the 10th century, forming the first Polish state and becoming the first historically recorded Piast duke. His realm roughly included all of the area of what would later be named the "Recovered Territories", except for the Warmian-Masurian part of Old Prussia

Prussia (Old Prussian: ''Prūsa''; german: Preußen; lt, Prūsija; pl, Prusy; russian: Пруссия, tr=Prussiya, ''/Prussia/Borussia'') is a historical region in Europe on the south-eastern coast of the Baltic Sea, that ranges from the Vis ...

and eastern Lusatia.

Mieszko's son and successor, Duke Bolesław I Chrobry, upon the 1018

Mieszko's son and successor, Duke Bolesław I Chrobry, upon the 1018 Peace of Bautzen

The Peace of Bautzen (; ; ) was a treaty concluded on 30 January 1018, between Holy Roman Emperor Henry II and Bolesław I of Poland which ended a series of Polish-German wars over the control of Lusatia and Upper Lusatia (''Milzenerland'' or ' ...

expanded the southern part of the realm, but lost control over the lands of Western Pomerania on the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

coast. After fragmentation, pagan revolts and a Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

n invasion in the 1030s, Duke Casimir I the Restorer (reigned 1040–1058) again united most of the former Piast realm, including Silesia and Lubusz Land on both sides of the middle Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows thr ...

River, but without Western Pomerania, which became part of the Polish state again under Bolesław III Wrymouth from 1116 until 1121, when the noble House of Griffins established the Duchy of Pomerania. On Bolesław's death in 1138, Poland for almost 200 years was subjected to fragmentation

Fragmentation or fragmented may refer to:

Computers

* Fragmentation (computing), a phenomenon of computer storage

* File system fragmentation, the tendency of a file system to lay out the contents of files non-continuously

* Fragmented distributi ...

, being ruled by Bolesław's sons and by their successors, who were often in conflict with each other. Władysław I the Elbow-high, crowned King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16t ...

in 1320, achieved partial reunification, although the Silesian and Masovian duchies remained independent Piast holdings.

In the course of the 12th to 14th centuries, Germanic, Dutch and Flemish settlers moved into East Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

and Eastern Europe in a migration process known as the ''Ostsiedlung

(, literally "East-settling") is the term for the Early Medieval and High Medieval migration-period when ethnic Germans moved into the territories in the eastern part of Francia, East Francia, and the Holy Roman Empire (that Germans had al ...

''. In Pomerania, Brandenburg, Prussia and Silesia, the indigenous West Slav

The West Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak the West Slavic languages. They separated from the common Slavic group around the 7th century, and established independent polities in Central Europe by the 8th to 9th centuries. The West Slavic langu ...

( Polabian Slavs and Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Ce ...

) or Balt

The Balts or Baltic peoples ( lt, baltai, lv, balti) are an ethno-linguistic group of peoples who speak the Baltic languages of the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages.

One of the features of Baltic languages is the number o ...

population became minorities in the course of the following centuries, although substantial numbers of the original inhabitants remained in areas such as Upper Silesia. In Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a Polish historical regions, historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed ...

and in Eastern Pomerania ( Pomerelia), German settlers formed a minority.

Despite the loss of several provinces, medieval lawyers of the Kingdom of Poland created a specific claim to all formerly Polish provinces that were not reunited with the rest of the country in 1320. They built on the theory of the ''Corona Regni Poloniae

The Crown of the Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Korona Królestwa Polskiego; Latin: ''Corona Regni Poloniae''), known also as the Polish Crown, is the common name for the historic Late Middle Ages territorial possessions of the King of Poland, includi ...

'', according to which the state (the Crown) and its interests were no longer strictly connected with the person of the monarch. Because of that no monarch could effectively renounce Crown claims to any of the territories that were historically and/or ethnically Polish. Those claims were reserved for the state (the Crown), which in theory still covered all of the territories that were part of, or dependent on, the Polish Crown upon the death of Bolesław III in 1138.

This concept was also developed to prevent from loss of territory after the death of King Casimir III the Great in 1370, when Louis I of Hungary

Louis I, also Louis the Great ( hu, Nagy Lajos; hr, Ludovik Veliki; sk, Ľudovít Veľký) or Louis the Hungarian ( pl, Ludwik Węgierski; 5 March 132610 September 1382), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1342 and King of Poland from 1370 ...

, who ruled Hungary with absolute power, was crowned King of Poland. In the 14th century Hungary was one of the greatest powers of Central Europe, and its influence reached various Balkan

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

principalities and southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

( Naples). Poland in personal union with Hungary was the smaller, politically weaker and peripheral country. In the Privilege of Koszyce

The Privilege of Koszyce or Privilege of KassaClifford Rogers (editor): ''The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology'', Oxford University Press, 201/ref> was a set of concessions made by Louis I of Hungary to the Polish s ...

(1374) King Louis I guaranteed that he would not detach any lands from the Polish Kingdom. The concept was not new, as it was inspired by similar Bohemian (Czech) laws ('' Corona regni Bohemiae'').

Some of the territories (such as Pomerelia and Masovia) reunited with Poland during the 15th and 16th centuries. However all Polish monarchs

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16t ...

until the end of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795 had to promise to do everything possible to reunite the rest of those territories with the Crown.

The areas of the Recovered Territories fall into three categories:

* Those that once had been part of the Polish state during the rule of the Piasts, many of which later on had been part of various Piast, Griffin

The griffin, griffon, or gryphon (Ancient Greek: , ''gryps''; Classical Latin: ''grȳps'' or ''grȳpus''; Late Latin, Late and Medieval Latin: ''gryphes'', ''grypho'' etc.; Old French: ''griffon'') is a legendary creature with the body, tail ...

, Jagiellon

The Jagiellonian dynasty (, pl, dynastia jagiellońska), otherwise the Jagiellon dynasty ( pl, dynastia Jagiellonów), the House of Jagiellon ( pl, Dom Jagiellonów), or simply the Jagiellons ( pl, Jagiellonowie), was the name assumed by a cad ...

and Sobieski-ruled duchies, some up to the 17th and 18th century, although often under foreign suzerainty

* Those that had been part of Poland until the 17th century (northernmost part of Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a Polish historical regions, historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed ...

, including Czaplinek) or were under Polish suzerainty as fiefs, in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries (southern Ducal Prussia and the Duchy of Opole, which also falls into the category above)

* Territories that had been part of Poland until the Partitions

Partition may refer to:

Computing Hardware

* Disk partitioning, the division of a hard disk drive

* Memory partition, a subdivision of a computer's memory, usually for use by a single job

Software

* Partition (database), the division of a ...

( Warmia, Malbork Voivodeship, parts of Pomerelia, northern Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a Polish historical regions, historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed ...

including Piła, Wałcz, and Złotów, which were annexed by Prussia in the First Partition of 1772; and Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

and western parts of Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a Polish historical regions, historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed ...

including Międzyrzecz and Wschowa, which followed in the Second Partition of 1793)

Many significant events in Polish history are associated with these territories, including the victorious battles of Cedynia (972), Niemcza (1017), Psie Pole

Psie Pole () (polish: ''Dog Field'') is one of the five administrative districts of Wrocław, Poland. Before 1928, it was an independent city. Its functions were largely taken over on 8 March 1990 by the Municipal Office of the newly established ...

and Głogów (1109), Grunwald (1410), Oliwa (1627), the lost battles of Legnica

Legnica (Polish: ; german: Liegnitz, szl, Lignica, cz, Lehnice, la, Lignitium) is a city in southwestern Poland, in the central part of Lower Silesia, on the Kaczawa River (left tributary of the Oder) and the Czarna Woda (Kaczawa), Czarna Woda ...

(1241) and Westerplatte (1939), the life and work of astronomers Nicolaus Copernicus (16th century) and Johannes Hevelius (17th century), the creation of the oldest Polish-language texts and printings ( Middle Ages and the Renaissance era), the creation of the standards and patterns of the Polish literary language (Renaissance era), Polish maritime history, the establishment of one of the first Catholic dioceses in Poland in the Middle Ages (in Wrocław and Kołobrzeg

Kołobrzeg ( ; csb, Kòlbrzég; german: Kolberg, ), ; csb, Kòlbrzég , is a port city in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in north-western Poland with about 47,000 inhabitants (). Kołobrzeg is located on the Parsęta River on the south coast o ...

), as well as the Polish Reformation in the Renaissance era.

Significant figures were born or lived in these territories. Astronomer Jan of Głogów

Jan, JaN or JAN may refer to:

Acronyms

* Jackson, Mississippi (Amtrak station), US, Amtrak station code JAN

* Jackson-Evers International Airport, Mississippi, US, IATA code

* Jabhat al-Nusra (JaN), a Syrian militant group

* Japanese Article Numb ...

and scholar Laurentius Corvinus

Laurentius Corvinus (german: Laurentius Rabe; pl, Wawrzyniec Korwin; 1465–1527) was a Silesian scholar who lectured as an "extraordinary" (''i.e.'' untenured) professor at the University of Krakow when Nicolaus Copernicus began to study ther ...

, who were teachers of Nicolaus Copernicus at the University of Kraków, both hailed from Lower Silesia. Jan Dantyszek

Johannes Dantiscus, (german: Johann(es) von Höfen-Flachsbinder; pl, Jan Dantyszek; 1 November 1485 – 27 October 1548) was prince-bishop of bishop of Warmia, Warmia and Bishop of Chełmno (Culm). In recognition of his diplomatic services for ...

(Renaissance poet and diplomat, named the ''Father of Polish Diplomacy'') and Marcin Kromer (Renaissance cartographer, diplomat, historian, music theoretician) were bishops of Warmia. The leading figures of the Polish Enlightenment are connected with these lands: philosopher, geologist, writer, poet, translator, statesman Stanisław Staszic and great patron of arts, writer, linguist, statesman and candidate for the Polish crown Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski were both born in these territories, Ignacy Krasicki (author of the first Polish novel, playwright, nicknamed ''the Prince of Polish Poets'') lived in Warmia in his adulthood, and brothers Józef Andrzej Załuski

Józef Andrzej Załuski (12 January 17029 January 1774) was a Polish Catholic priest, Bishop of Kiev, a sponsor of learning and culture, and a renowned bibliophile. A member of the Polish nobility (''szlachta''), bearing the hereditary Junosza ...

and Andrzej Stanisław Załuski

Andrzej Stanisław Kostka Załuski (2 December 1695 – 16 December 1758) was a priest (bishop) in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

In his religious career he held the posts of abbot and later Bishop of Płock (from 1723), bishop of Łu ...

(founders of the Załuski Library in Warsaw, one of the largest 18th-century book collections in the world) grew up and studied in these territories. Also painters Daniel Schultz, Tadeusz Kuntze

Tadeusz Kuntze (also Taddeo Kuntze or Taddeo Polacco) was the pseudonym of the Polish-Silesian painter Tadeusz Konicz (3 October 1733 – 8 May 1793), who was active in Kraków, in Paris, in Spain and in Rome.

Life

Konicz was born in Grünberg, ...

and Antoni Blank, as well as composers Grzegorz Gerwazy Gorczycki

Grzegorz Gerwazy Gorczycki (ca. 1665 to 1667 – 30 April 1734) was a Polish Baroque composer. Considered one of the greatest composers of Polish Baroque music, during his lifetime he was called the "Polish Handel".

Life

Born in Rozbark near Byt ...

and Feliks Nowowiejski

Feliks Nowowiejski (7 February 1877 – 18 January 1946) was a Polish composer, conductor, concert organist, and music teacher. Nowowiejski was born in Wartenburg (today Barczewo) in Warmia in the Prussian Partition of Poland (then admini ...

were born in these lands.

By the time that Poland regained her independence in 1918, Polish activist Dr. Józef Frejlich was already claiming that the lands situated on the right bank of the

By the time that Poland regained her independence in 1918, Polish activist Dr. Józef Frejlich was already claiming that the lands situated on the right bank of the Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows thr ...

river, including inner industrial cities such as Wrocław, and Baltic ports such as Szczecin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

and Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

, were economic parts of Poland that had to be united with the rest of the "economic territory of Poland" into a united and independent state, as a fundamental condition of the economic revival of Poland after World War I.

After the successful Greater Poland uprising, the cession of Pomerelia to Poland following the Treaty of Versailles and the Silesian Uprisings that allowed Poland to obtain a large portion of Upper Silesia, the territorial claims of the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of ...

were directed towards the rest of partially Polish speaking Upper Silesia and Masuria under German control, as well as the city of Danzig, the Czechoslovakian part of Cieszyn Silesia and other bordering areas with significant Polish population. The Polish population of these lands was subject to Germanisation

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, German people, people and German culture, culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationa ...

and intensified repressions, especially after the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933.

Most of long Germanized Lower Silesia, Farther Pomerania

Farther Pomerania, Hinder Pomerania, Rear Pomerania or Eastern Pomerania (german: Hinterpommern, Ostpommern), is the part of Pomerania which comprised the eastern part of the Duchy and later Province of Pomerania. It stretched roughly from the Od ...

and Eastern Prussia remained undisputed. However, in reaction to Hitler's Germany threats to Poland shortly before the outbreak of World War II, Polish nationalists displayed maps of Poland including those ancient Polish territories as well, claiming their intention to recover them.

In the interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

the German administration, even before the Nazis took power, conducted a massive campaign of renaming of thousands of placenames, to remove traces of Slavic origin.

Pomerania

Mieszko I

Mieszko I (; – 25 May 992) was the first ruler of Poland and the founder of the first independent Polish state, the Duchy of Poland. His reign stretched from 960 to his death and he was a member of the Piast dynasty, a son of Siemomysł and ...

acquired at least significant parts of them. Mieszko's son Bolesław I established a bishopric in the Kołobrzeg

Kołobrzeg ( ; csb, Kòlbrzég; german: Kolberg, ), ; csb, Kòlbrzég , is a port city in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in north-western Poland with about 47,000 inhabitants (). Kołobrzeg is located on the Parsęta River on the south coast o ...

area in 1000–1005/07, before the area was lost again. Despite further attempts by Polish dukes to again control the Pomeranian tribes, this was only partly achieved by Bolesław III Boleslav or Bolesław may refer to:

In people:

* Boleslaw (given name)

In geography:

*Bolesław, Dąbrowa County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland

*Bolesław, Olkusz County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland

*Bolesław, Silesian Voivodeship, Pol ...

in several campaigns lasting from 1116 to 1121. Successful Christian missions ensued in 1124 and 1128; however, by the time of Bolesław's death in 1138, most of West Pomerania (the Griffin-ruled areas) was no longer controlled by Poland. Shortly after, the Griffin Duke of Pomerania, Boguslav I., achieved the integration of Pomerania into the Holy Roman Empire. The easternmost part of later Western Pomerania (including the city of Słupsk) in the 13th century was part of Eastern Pomerania

Eastern Pomerania can refer to distinct parts of Pomerania:

*The historical region of Farther Pomerania, which was the eastern part of the Duchy, later Province of Pomerania

*The historical region of Pomerelia including Gdańsk Pomerania, located ...

, which was re-integrated with Poland, and later on, in the 14th and 15th centuries formed a duchy

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a Middle Ages, medieval country, territory, fiefdom, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or Queen regnant, queen in Western European tradition.

There once exis ...

, which rulers were vassals of Jagiellon-ruled Poland. Over the following centuries Western Pomerania was largely Germanized, although a small Slavic Polabian minority remained. Indigenous Slavs and Poles faced discrimination

Discrimination is the act of making unjustified distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong. People may be discriminated on the basis of race, gender, age, relig ...

from the arriving Germans, who on a local level since the 16th century imposed discriminatory regulations, such as bans on buying goods from Slavs/Poles or prohibiting them from becoming members of craft guilds. The Duchy of Pomerania under the native Griffin dynasty existed for over 500 years, before it was partitioned between Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

and Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohenz ...

in the 17th century. At the turn of the 20th century there lived about 14,200 persons of Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

mother-tongue in the Province of Pomerania (in the east of Farther Pomerania

Farther Pomerania, Hinder Pomerania, Rear Pomerania or Eastern Pomerania (german: Hinterpommern, Ostpommern), is the part of Pomerania which comprised the eastern part of the Duchy and later Province of Pomerania. It stretched roughly from the Od ...

in the vicinity of the border with the province of West Prussia), and 300 persons using the Kashubian language

Kashubian or Cassubian (Kashubian: ', pl, język kaszubski) is a West Slavic language belonging to the Lechitic subgroup along with Polish and Silesian.Stephen Barbour, Cathie Carmichael, ''Language and Nationalism in Europe'', Oxford Univers ...

(at the Łeba Lake and the Lake Gardno

Gardno (german: Garder See) is a lake in the Słowińskie Lakeland in Pomeranian Voivodship, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivo ...

), the total population of the province consisting of almost 1.7 million inhabitants. The Polish communities in many cities of the region, such as Szczecin

Szczecin (, , german: Stettin ; sv, Stettin ; Latin: ''Sedinum'' or ''Stetinum'') is the capital and largest city of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. Located near the Baltic Sea and the German border, it is a major s ...

and Kołobrzeg, faced intensified repressions after the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

came to power in Germany in 1933.

Gdańsk, Lębork and Bytów

The region of Pomerelia at the eastern end of Pomerania, including

The region of Pomerelia at the eastern end of Pomerania, including Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

(Danzig), was part of Poland since its first ruler Mieszko I

Mieszko I (; – 25 May 992) was the first ruler of Poland and the founder of the first independent Polish state, the Duchy of Poland. His reign stretched from 960 to his death and he was a member of the Piast dynasty, a son of Siemomysł and ...

. As a result of the fragmentation of Poland, it was ruled in the 12th and 13th centuries by the Samborides, who were (at least initially) more closely tied to the Kingdom of Poland than were the Griffins. After the Treaty of Kępno

The Treaty of Kępno ( pl, Umowa kępińska, Układ w Kępnie) was an agreement between the High Duke of Poland and Wielkopolska Przemysł II and the Duke of Pomerania Mestwin II (sometimes rendered as "Mściwój") signed on February 15, 1282, whi ...

in 1282, and the death of the last Samboride in 1294, the region was ruled by kings of Poland for a short period, although also claimed by Brandenburg. After the Teutonic takeover in 1308 the region was annexed to the monastic state of the Teutonic Knights.

Most cities of the region joined or sided with the Prussian Confederation, which in 1454 started an uprising against Teutonic rule and asked the Polish King Casimir IV Jagiellon to incorporate the region to Poland. After the King agreed and signed the act of incorporation, the Thirteen Years' War broke out, ending in a Polish victory. The Second Peace of Thorn (1466) made Royal Prussia a part of Poland. It had a substantial autonomy and a lot of privileges. It formed the Pomeranian Voivodeship

Pomeranian Voivodeship, Pomorskie Region, or Pomerania Province (Polish: ''Województwo pomorskie'' ; ( Kashubian: ''Pòmòrsczé wòjewództwò'' ), is a voivodeship, or province, in northwestern Poland. The provincial capital is Gdańsk.

The ...

, located within the province of Royal Prussia in the Kingdom of Poland, as it remained until being annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia in the partitions

Partition may refer to:

Computing Hardware

* Disk partitioning, the division of a hard disk drive

* Memory partition, a subdivision of a computer's memory, usually for use by a single job

Software

* Partition (database), the division of a ...

of 1772 and 1793. A small area in the west of Pomerelia, the Lauenburg and Bütow Land

Lauenburg and Bütow Land (german: Länder or , csb, Lãbòrskò-bëtowskô Zemia, pl, Ziemia lęborsko-bytowska) formed a historical region in the western part of Pomerelia (Polish and papal historiography) or in the eastern part of Farther Pom ...

(the region of Lębork and Bytów) was granted to the rulers of Pomerania as a Polish fief, before being reintegrated with Poland in 1637, and later on, again transformed into a Polish fief, which it remained until the First Partition, when three quarters of Royal Prussia's urban population were German-speaking Protestants.

After Poland regained independence in 1918, a large part of Pomerelia was reintegrated with Poland, as the so-called Polish Corridor, and so was not part of the post-war so-called Recovered Territories.

Lubusz Land and parts of Greater Poland

The medieval Lubusz Land on both sides of the Oder River up to the

The medieval Lubusz Land on both sides of the Oder River up to the Spree

Spree may refer to:

Geography

* Spree (river), river in Germany

Film and television

* ''The Spree'', a 1998 American television film directed by Tommy Lee Wallace

* ''Spree'' (film), a 2020 American film starring Joe Keery

* "Spree" (''Numbers' ...

in the west, including Lubusz (Lebus

Lebus ( pl, Lubusz) is a historic town in the Märkisch-Oderland District of Brandenburg, Germany. It is the administrative seat of '' Amt'' ("collective municipality") Lebus. The town, located on the west bank of the Oder river at the border wi ...

) itself, also formed part of Mieszko's realm. In the period of fragmentation of Poland the Lubusz Land was in different periods part of the Greater Poland and Silesian provinces of Poland. Poland lost Lubusz when the Silesian duke Bolesław II Rogatka Boleslav or Bolesław may refer to:

In people:

* Boleslaw (given name)

In geography:

* Bolesław, Dąbrowa County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland

* Bolesław, Olkusz County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland

* Bolesław, Silesian Voivodeship, ...

sold it to the Ascanian

The House of Ascania (german: Askanier) was a dynasty of German rulers. It is also known as the House of Anhalt, which refers to its longest-held possession, Anhalt.

The Ascanians are named after Ascania (or Ascaria) Castle, known as ''Schloss ...

margraves of Brandenburg in 1249. The Bishopric of Lebus

The Diocese of Lebus (; ; ) is a former diocese of the Catholic Church. It was erected in 1125 and suppressed in 1598. The Bishop of Lebus was also, ''ex officio'', the ruler of a lordship that was coextensive with the territory of the diocese. Th ...

, established by Polish Duke Bolesław III Wrymouth, remained a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Gniezno until 1424, when it passed under the jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Magdeburg

The Archbishopric of Magdeburg was a Roman Catholic archdiocese (969–1552) and Prince-Archbishopric (1180–1680) of the Holy Roman Empire centered on the city of Magdeburg on the Elbe River.

Planned since 955 and established in 968, the Roma ...

. The Lubusz Land was part of the Lands of the Bohemian (Czech) Crown from 1373 to 1415.

Brandenburg also acquired the castellany of Santok

Santok (german: Zantoch) is a village in Gorzów County, Lubusz Voivodeship, in western Poland. It is the seat of the gmina (administrative district) called Gmina Santok.

Geography

It is located at the confluence of the Noteć and Warta rive ...

, which formed part of the Duchy of Greater Poland, from Duke Przemysł I of Greater Poland and made it the nucleus of their Neumark ("New March") region. In the following decades Brandenburg annexed further parts of northwestern Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a Polish historical regions, historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed ...

. Later on, Santok was briefly recaptured by the Poles several times. Of the other cities, King Casimir III the Great recovered Wałcz in 1368. The lost parts of Greater Poland were part of the Lands of the Bohemian (Czech) Crown from 1373 to 1402, when despite an agreement between the Luxembourg dynasty of Bohemia and the Jagiellons of Poland on the sale of the region to Poland, it was sold to the Teutonic Order. During the Polish–Teutonic War (1431–35) several towns of the region rebelled against the Order to join Poland, among them Choszczno

Choszczno (german: Arnswalde) is a town in West Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland. As of December 2021, the town has a population of 14,831. The town is in a marshy district between the river Stobnica and Klukom lake, southeast of Stargard and on ...

, Drawno and Złocieniec

Złocieniec (; formerly german: Falkenburg) is a town in northwestern Poland. Located in West Pomeranian Voivodeship's Drawsko County since 1999, it was previously a part of Koszalin Voivodeship (1950–1998). The population of Złocieniec is a ...

. The present-day Polish Lubusz Voivodeship comprises most of the former Brandenburgian Neumark territory east of the Oder.

Brandenburg-Prussia

Brandenburg-Prussia (german: Brandenburg-Preußen; ) is the historiographic denomination for the early modern realm of the Brandenburgian Hohenzollerns between 1618 and 1701. Based in the Electorate of Brandenburg, the main branch of the Hohenz ...

in 1668. Bigger portions of Greater Poland were lost in the Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

: the northern part with Piła and Wałcz in the First Partition and the remainder, including the western part with Międzyrzecz and Wschowa in the Second Partition. During Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

ic times the Greater Poland territories formed part of the Duchy of Warsaw, but after the Congress of Vienna Prussia reclaimed them as part of the Grand Duchy of Posen (Poznań), later Province of Posen

The Province of Posen (german: Provinz Posen, pl, Prowincja Poznańska) was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1848 to 1920. Posen was established in 1848 following the Greater Poland Uprising as a successor to the Grand Duchy of Posen, w ...

. After World War I, those parts of the former Province of Posen and of West Prussia that were not restored as part of the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of ...

were administered as Grenzmark Posen-Westpreußen (the German Province of Posen–West Prussia) until 1939.

Silesia

Gesta principum Polonorum

The ''Gesta principum Polonorum'' (; "''Deeds of the Princes of the Poles''") is the oldest known medieval chronicle documenting the history of Poland from the legendary times until 1113. Written in Latin by an anonymous author, it was most lik ...

''. Henry I the Bearded granted town rights for the first time in the history of Poland in 1211 to the Lower Silesian town of Złotoryja. The ''Book of Henryków

The ''Book of Henryków'' ( pl, Księga henrykowska, la, Liber fundationis claustri Sanctae Mariae Virginis in Heinrichow) is a Latin chronicle of the Cistercian abbey in Henryków in Lower Silesia, Poland. Originally created as a registry of ...

'', containing the oldest known written sentence in Polish, was created in Lower Silesia. The first Polish-language printed text was published in Wrocław by Głogów-born Kasper Elyan, who is regarded as the first Polish printer. Burial sites of Polish monarchs are located in Wrocław, Trzebnica and Legnica

Legnica (Polish: ; german: Liegnitz, szl, Lignica, cz, Lehnice, la, Lignitium) is a city in southwestern Poland, in the central part of Lower Silesia, on the Kaczawa River (left tributary of the Oder) and the Czarna Woda (Kaczawa), Czarna Woda ...

.

Piast dukes continued to rule Silesia following the 12th-century fragmentation of Poland. The Silesian Piasts retained power in most of the region until the early 16th century, the last ( George William, duke of Legnica

Legnica (Polish: ; german: Liegnitz, szl, Lignica, cz, Lehnice, la, Lignitium) is a city in southwestern Poland, in the central part of Lower Silesia, on the Kaczawa River (left tributary of the Oder) and the Czarna Woda (Kaczawa), Czarna Woda ...

) dying in 1675. Some Lower Silesian duchies were also under the rule of Polish Jagiellons ( Głogów) and Sobieskis ( Oława), and part of Upper Silesia, the Duchy of Opole, found itself back under Polish rule in the mid-17th century, when the Habsburgs pawned the duchy to the Polish Vasas. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Wrocław

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

, established in 1000 as one of Poland's oldest dioceses, remained a suffragan of the Archbishopric of Gniezno until 1821.

The first German colonists arrived in the late 12th century, and large-scale German settlement started in the early 13th century during the reign of Henry I (Duke of Silesia from 1201 to 1238). After the era of German colonisation, the Polish language still predominated in Upper Silesia and in parts of Lower and Middle Silesia north of the Odra river. Here the Germans who arrived during the Middle Ages became mostly Polonized; Germans dominated in large cities and Poles mostly in rural areas. The Polish-speaking territories of Lower and Middle Silesia, commonly described until the end of the 19th century as the ''Polish side'', were mostly Germanized in the 18th and 19th centuries, except for some areas along the northeastern frontier. The province came under the control of Kingdom of Bohemia in the 14th century and was briefly under Hungarian rule in the 15th century. Silesia passed to the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

of Austria in 1526, and Prussia's Frederick the Great conquered most of it in 1742. A part of Upper Silesia became part of Poland after World War I and the Silesian Uprisings, but the bulk of Silesia formed part of the post-1945 Recovered Territories.

Warmia and Masuria

The territories of Warmia and Masuria were originally inhabited by pagan Old Prussians, until the conquest by the Teutonic Knights in the 13th and 14th centuries. In order to repopulate the conquered areas, Poles from neighboring Masovia, called Masurians (''Mazurzy''), were allowed to settle here (hence the name Masuria). During an uprising against the Teutonic Order most towns of the region joined or sided with the Prussian Confederation, at the request of which King Casimir IV Jagiellon signed the act of incorporation of the region into the Kingdom of Poland (1454). After the Second Peace of Thorn (1466) Warmia was confirmed to be incorporated to Poland, while Masuria became part of a Polish fief, first as part of the Teutonic state, and from 1525 as part of the secular Ducal Prussia. Then it would become one of the leading centers of Polish Lutheranism, while Warmia, under the administration of prince-bishops remained one of the most overwhelmingly Catholic regions of Poland.

Polish suzerainty over Masuria ended in 1657/1660 as a result of the Deluge and Warmia was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia in the First Partition of Poland (1772). Both regions formed the southern part of the province of

The territories of Warmia and Masuria were originally inhabited by pagan Old Prussians, until the conquest by the Teutonic Knights in the 13th and 14th centuries. In order to repopulate the conquered areas, Poles from neighboring Masovia, called Masurians (''Mazurzy''), were allowed to settle here (hence the name Masuria). During an uprising against the Teutonic Order most towns of the region joined or sided with the Prussian Confederation, at the request of which King Casimir IV Jagiellon signed the act of incorporation of the region into the Kingdom of Poland (1454). After the Second Peace of Thorn (1466) Warmia was confirmed to be incorporated to Poland, while Masuria became part of a Polish fief, first as part of the Teutonic state, and from 1525 as part of the secular Ducal Prussia. Then it would become one of the leading centers of Polish Lutheranism, while Warmia, under the administration of prince-bishops remained one of the most overwhelmingly Catholic regions of Poland.

Polish suzerainty over Masuria ended in 1657/1660 as a result of the Deluge and Warmia was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia in the First Partition of Poland (1772). Both regions formed the southern part of the province of East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

, established in 1773.

All of Warmia and most of Masuria remained part of Germany after World War I and the re-establishment of independent Poland. During the 1920 East Prussian Plebiscite

The East Prussian plebiscite (german: Abstimmung in Ostpreußen), also known as the Allenstein and Marienwerder plebiscite or Warmia, Masuria and Powiśle plebiscite ( pl, Plebiscyt na Warmii, Mazurach i Powiślu), was a plebiscite organised in a ...

, the districts east of the Vistula within the region of Marienwerder (Kwidzyn), along with all of the Allenstein Region (Olsztyn) and the district of Oletzko voted to be included within the province of East Prussia and thus became part of Weimar Germany. All of the region as the southern part of the province of East Prussia became part of Poland after World War II, with northern East Prussia going to the Soviet Union to form the Kaliningrad Oblast.

Origin and use of the term

The term "Recovered Territories" was officially used for the first time in the Decree of the President of the Republic of 11 October 1938 after the annexation of Zaolzie by the Polish army. It became the official termAn explanation note i

The term "Recovered Territories" was officially used for the first time in the Decree of the President of the Republic of 11 October 1938 after the annexation of Zaolzie by the Polish army. It became the official termAn explanation note i''"The Neighbors Respond: The Controversy Over the Jedwabne Massacre in Poland"''

, ed. by Polonsky and Michlic, p. 466 coined in the aftermath of World War II to denote the former eastern territories of Germany that were being handed over to Poland, pending a final peace conference with Germany which eventually never took place. The underlying concept was to define post-war Poland as heir to the medieval Piasts' realm,Joanna B. Michlic, ''Poland's Threatening Other: The Image of the Jew from 1880 to the Present'', 2006, pp. 207–208, , Norman Davies, ''God's Playground: A History of Poland in Two Volumes'', 2005, pp. 381ff, , Geoffrey Hosking, George Schopflin, ''Myths and Nationhood'', 1997, p. 153, , which was simplified into a picture of an ethnically homogeneous state that matched post-war borders,Jan Kubik, ''The Power of Symbols Against the Symbols of Power: The Rise of Solidarity and the Fall of State Socialism in Poland'', 1994, pp. 64–65, , as opposed to the later

Jagiellon

The Jagiellonian dynasty (, pl, dynastia jagiellońska), otherwise the Jagiellon dynasty ( pl, dynastia Jagiellonów), the House of Jagiellon ( pl, Dom Jagiellonów), or simply the Jagiellons ( pl, Jagiellonowie), was the name assumed by a cad ...

Poland, which was multi-ethnic and located further east. The argument that this territory in fact constituted "old Polish lands"Alfred M. De Zayas, ''Nemesis at Potsdam'', p. 168 seized on a pre-war concept developed by Polish right-wing circles attached to the SN. As cited by

One reason for post-war Poland's favoring a Piast rather than a Jagiellon tradition was Joseph Stalin's refusal to withdraw from the Curzon line and the Allies' readiness to satisfy Poland with German territory instead.Rick Fawn, ''Ideology and national identity in post-communist foreign policies'', 2003, p. 190, , The original argument for awarding formerly German territory to Poland – compensation – was complemented by the argument that this territory in fact constituted former areas of Poland.Joanna B. Michlic, ''Poland's Threatening Other: The Image of the Jew from 1880 to the Present'', 2006, p. 208, , Jan Kubik, ''The Power of Symbols Against the Symbols of Power: The Rise of Solidarity and the Fall of State Socialism in Poland'', 1994, p. 65, , Dmitrow says that "in official justifications for the border shift, the decisive argument that it presented a compensation for the loss of the eastern half of the pre-war Polish territory to the USSR, was viewed as obnoxious and concealed. Instead, a historical argumentation was foregrounded with the dogma, Poland had just returned to 'ancient Piast lands'." Objections to the Allies' decisions and criticism of the Polish politicians' role at Potsdam were censored. In a commentary for Tribune,

One reason for post-war Poland's favoring a Piast rather than a Jagiellon tradition was Joseph Stalin's refusal to withdraw from the Curzon line and the Allies' readiness to satisfy Poland with German territory instead.Rick Fawn, ''Ideology and national identity in post-communist foreign policies'', 2003, p. 190, , The original argument for awarding formerly German territory to Poland – compensation – was complemented by the argument that this territory in fact constituted former areas of Poland.Joanna B. Michlic, ''Poland's Threatening Other: The Image of the Jew from 1880 to the Present'', 2006, p. 208, , Jan Kubik, ''The Power of Symbols Against the Symbols of Power: The Rise of Solidarity and the Fall of State Socialism in Poland'', 1994, p. 65, , Dmitrow says that "in official justifications for the border shift, the decisive argument that it presented a compensation for the loss of the eastern half of the pre-war Polish territory to the USSR, was viewed as obnoxious and concealed. Instead, a historical argumentation was foregrounded with the dogma, Poland had just returned to 'ancient Piast lands'." Objections to the Allies' decisions and criticism of the Polish politicians' role at Potsdam were censored. In a commentary for Tribune, George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitar ...

likened the transfer of German population to transferring the whole of the Irish and Scottish population.

Also, the Piasts were perceived to have defended Poland against the Germans, while the Jagiellons' main rival had been the growing Duchy of Moscow

The Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovite Russia, Muscovite Rus' or Grand Principality of Moscow (russian: Великое княжество Московское, Velikoye knyazhestvo Moskovskoye; also known in English simply as Muscovy from the Lati ...

, making them a less suitable basis for post-war Poland's Soviet-dominated situation. The People's Republic of Poland

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million nea ...

under the Polish Workers' Party thus supported the idea of Poland based on old Piast lands. The question of the Recovered Territories was one of the few issues that did not divide the Polish Communists and their opposition, and there was unanimity regarding the western border. Even the underground anti-Communist press called for the Piast borders, that would end Germanisation

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, German people, people and German culture, culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationa ...

and '' Drang nach Osten''.

Great efforts were made to propagate the view of the Piast Concept. It was actively supported by the Catholic Church. The sciences were responsible for the development of this perception of history. In 1945 the Western Institute

The Western Institute in Poznań (Polish: ''Instytut Zachodni'', German ''West-Institut'', French: ''L'Institut Occidental'') is a scientific research society focusing on the Western provinces of Poland - Kresy Zachodnie (including Greater Polan ...

( pl, Instytut Zachodni) was founded to coordinate the scientific activities. Its director, Zygmunt Wojciechowski