Yale Graduate School Of Arts And Sciences Alumni on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Yale University is a private

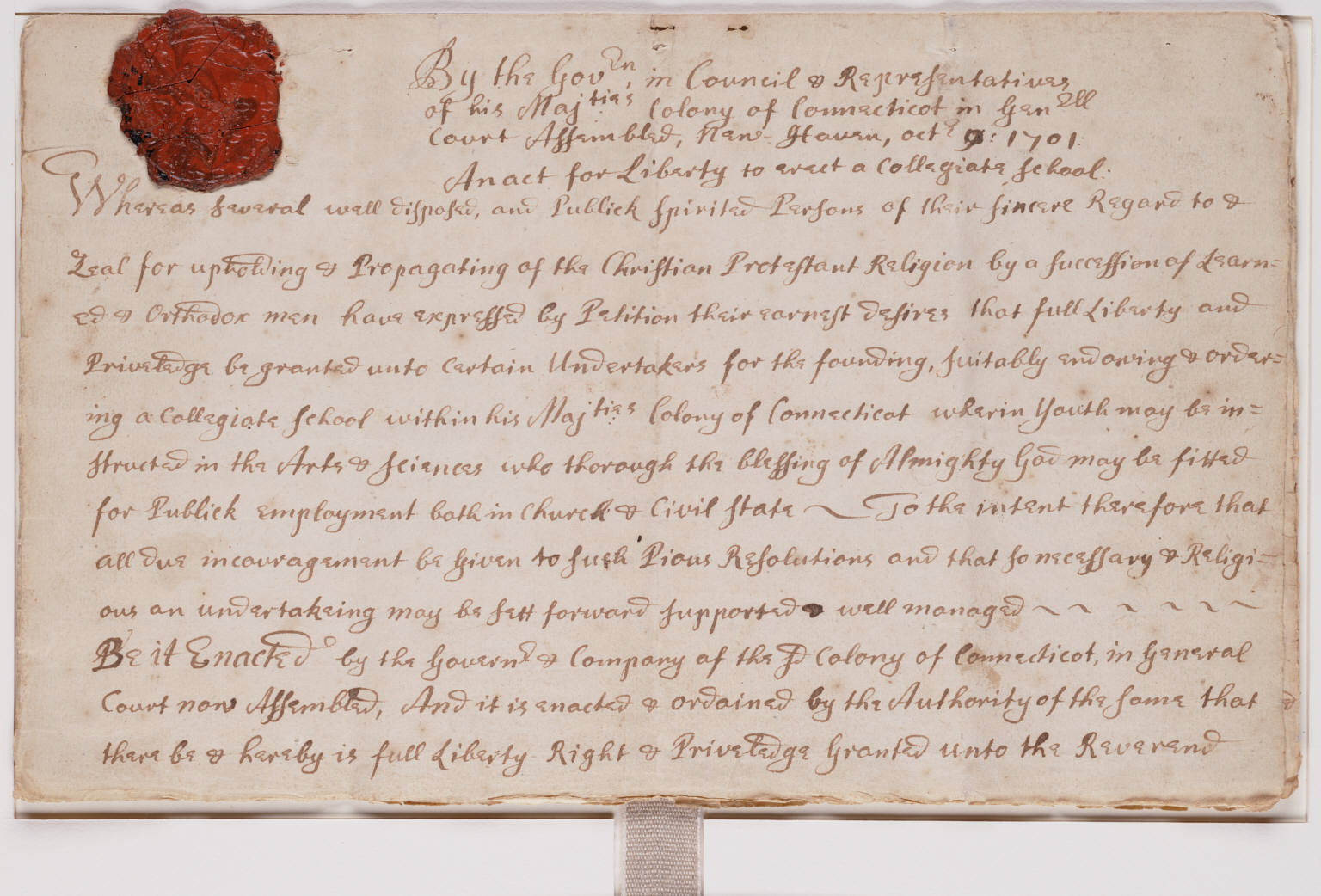

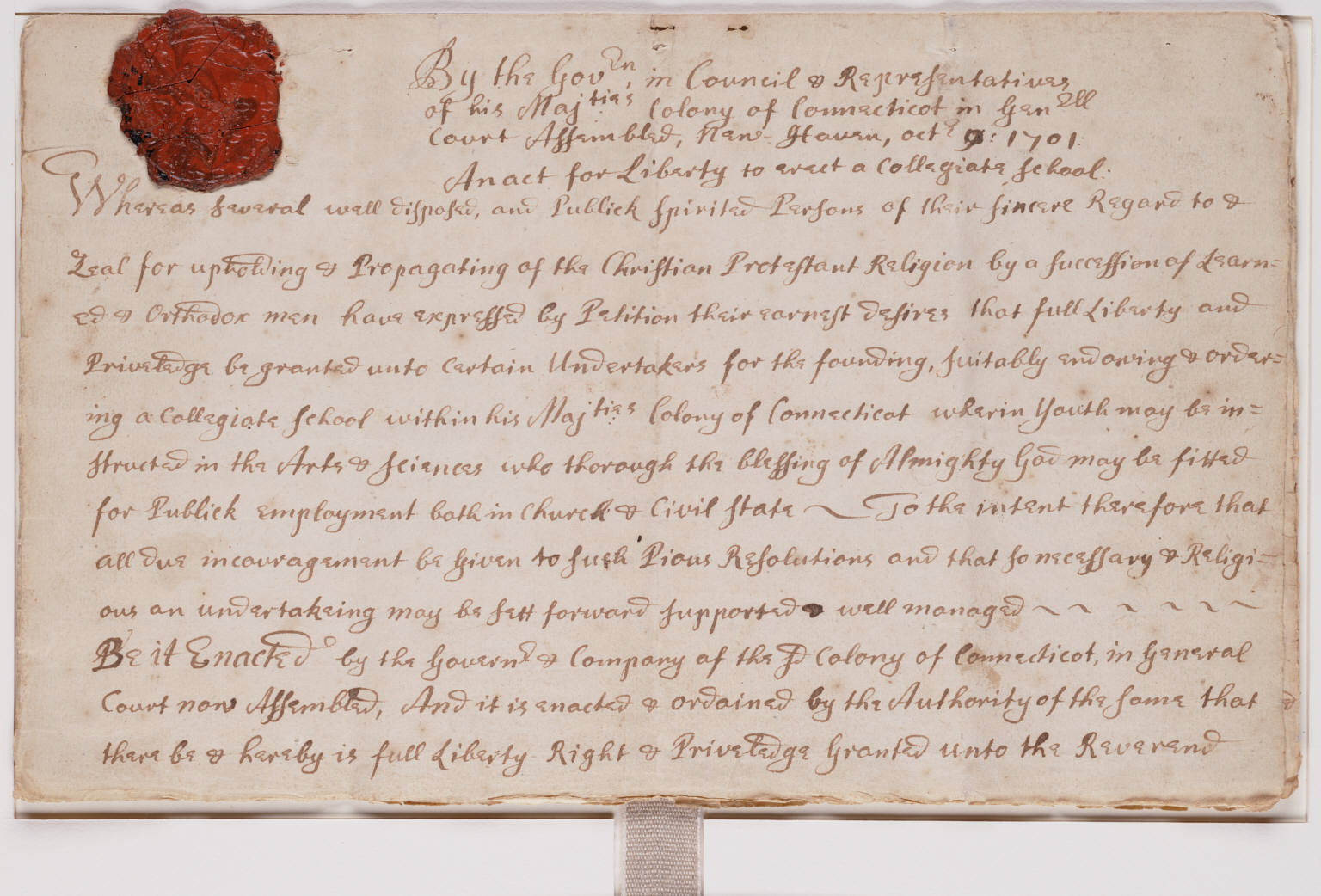

Yale traces its beginnings to "An Act for Liberty to Erect a Collegiate School", a would-be charter passed during a meeting in New Haven by the General Court of the

Yale traces its beginnings to "An Act for Liberty to Erect a Collegiate School", a would-be charter passed during a meeting in New Haven by the General Court of the  Known from its origin as the "Collegiate School", the institution opened in the home of its first

Known from its origin as the "Collegiate School", the institution opened in the home of its first

In 1718, at the behest of either Rector

In 1718, at the behest of either Rector

Yale College undergraduates follow a

Yale College undergraduates follow a

The

The

Along with Harvard and

Along with Harvard and

Milton Winternitz led the

Milton Winternitz led the

Before

Before

Pamela Price

(civil rights attorney in California), and Lisa E. Stone (works at

Raymond Duvall

(now at the

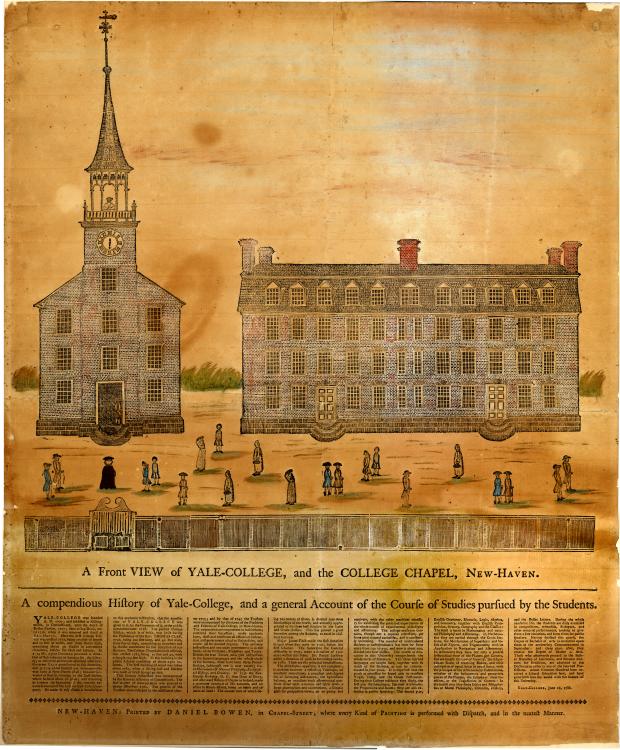

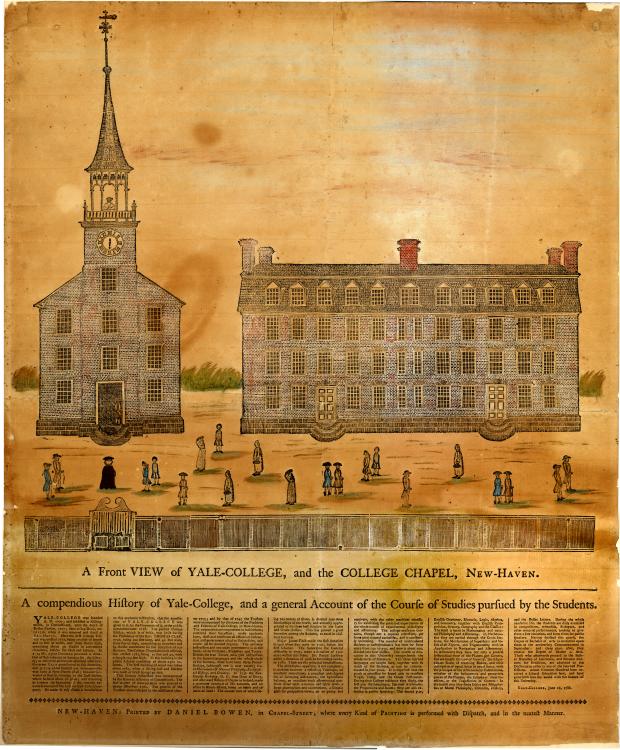

Yale's central campus in

Yale's central campus in

Other examples of the Gothic style are on the

Other examples of the Gothic style are on the

Notable nonresidential campus buildings and landmarks include

Notable nonresidential campus buildings and landmarks include

File:Jonathan Edwards Courtyard.jpg,

Yale supports 35 varsity athletic teams that compete in the

Yale supports 35 varsity athletic teams that compete in the  October 21, 2000, marked the dedication of Yale's fourth new boathouse in 157 years of collegiate rowing. The Gilder Boathouse is named to honor former Olympic rower Virginia Gilder '79 and her father Richard Gilder '54, who gave $4 million towards the $7.5 million project. Yale also maintains the Gales Ferry site where the heavyweight men's team trains for the Yale-Harvard Boat Race.

Yale crew is the oldest collegiate athletic team in America, and won

October 21, 2000, marked the dedication of Yale's fourth new boathouse in 157 years of collegiate rowing. The Gilder Boathouse is named to honor former Olympic rower Virginia Gilder '79 and her father Richard Gilder '54, who gave $4 million towards the $7.5 million project. Yale also maintains the Gales Ferry site where the heavyweight men's team trains for the Yale-Harvard Boat Race.

Yale crew is the oldest collegiate athletic team in America, and won

Over its history, Yale has produced many distinguished alumni in a variety of fields, ranging from the public to private sector. According to 2020 data, around 71% of undergraduates join the workforce, while the next largest majority of 16.6% go on to attend graduate or professional schools. Yale graduates have been recipients of 252

Over its history, Yale has produced many distinguished alumni in a variety of fields, ranging from the public to private sector. According to 2020 data, around 71% of undergraduates join the workforce, while the next largest majority of 16.6% go on to attend graduate or professional schools. Yale graduates have been recipients of 252  Yale alumni have had considerable presence in U.S. government in all three branches. On the U.S. Supreme Court, 19 justices have been Yale alumni, including current Associate Justices

Yale alumni have had considerable presence in U.S. government in all three branches. On the U.S. Supreme Court, 19 justices have been Yale alumni, including current Associate Justices  Yale has produced numerous award-winning authors and influential writers, like

Yale has produced numerous award-winning authors and influential writers, like  In business, Yale has had numerous alumni and former students go on to become founders of influential business, like

In business, Yale has had numerous alumni and former students go on to become founders of influential business, like

Gutenberg.org

Yale University also is mentioned in F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel ''

''Documentary History of Yale University: Under the Original Charter of the Collegiate School of Connecticut, 1701–1745.''

New Haven:

online

* *

Yale Athletics website

* {{Authority control Buildings and structures in New Haven, Connecticut Colonial colleges Education in New Haven, Connecticut Educational institutions established in 1701 Non-profit organizations based in Connecticut Universities and colleges in New Haven County, Connecticut Tourist attractions in New Haven, Connecticut 1701 establishments in Connecticut Private universities and colleges in Connecticut

research university

A research university or a research-intensive university is a university that is committed to research as a central part of its mission. They are the most important sites at which knowledge production occurs, along with "intergenerational kno ...

in New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,023 ...

. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States

Higher education in the United States is an optional stage of formal learning following secondary education. Higher education is also referred as post-secondary education, third-stage, third-level, or tertiary education. It covers stages 5 to 8 ...

and among the most prestigious in the world. It is a member of the Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising eight private research universities in the Northeastern United States. The term ''Ivy League'' is typically used beyond the sports context to refer to the eight schoo ...

.

Chartered by the Connecticut Colony

The ''Connecticut Colony'' or ''Colony of Connecticut'', originally known as the Connecticut River Colony or simply the River Colony, was an English colony in New England which later became Connecticut. It was organized on March 3, 1636 as a settl ...

, the Collegiate School was established in 1701 by clergy to educate Congregational

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs it ...

ministers before moving to New Haven in 1716. Originally restricted to theology and sacred language

A sacred language, holy language or liturgical language is any language that is cultivated and used primarily in church service or for other religious reasons by people who speak another, primary language in their daily lives.

Concept

A sac ...

s, the curriculum began to incorporate humanities and sciences by the time of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

. In the 19th century, the college expanded into graduate and professional instruction, awarding the first PhD PHD or PhD may refer to:

* Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), an academic qualification

Entertainment

* '' PhD: Phantasy Degree'', a Korean comic series

* ''Piled Higher and Deeper

''Piled Higher and Deeper'' (also known as ''PhD Comics''), is a newsp ...

in the United States in 1861 and organizing as a university in 1887. Yale's faculty and student populations grew after 1890 with rapid expansion of the physical campus and scientific research.

Yale is organized into fourteen constituent schools: the original undergraduate college, the Yale Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and twelve professional schools. While the university is governed by the Yale Corporation

The Yale Corporation, officially The President and Fellows of Yale College, is the governing body of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

Assembly of corporation

The Corporation comprises 19 members:

* Three ex officio members: the Presiden ...

, each school's faculty

Faculty may refer to:

* Faculty (academic staff), the academic staff of a university (North American usage)

* Faculty (division), a division within a university (usage outside of the United States)

* Faculty (instrument)

A faculty is a legal in ...

oversees its curriculum and degree programs. In addition to a central campus in downtown New Haven

Downtown New Haven is the neighborhood located in the heart of the city of New Haven, Connecticut. It is made up of the original nine squares laid out in 1638 to form New Haven, including the New Haven Green, and the immediate surrounding central ...

, the university owns athletic facilities in western New Haven, a campus in West Haven, and forests and nature preserves throughout New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian province ...

. , the university's endowment was valued at $42.3 billion, the second largest of any educational institution. The Yale University Library

The Yale University Library is the library system of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Originating in 1701 with the gift of several dozen books to a new "Collegiate School," the library's collection now contains approximately 14.9 milli ...

, serving all constituent schools, holds more than 15 million volumes and is the third-largest academic library in the United States. Students compete in intercollegiate sports as the Yale Bulldogs

The Yale Bulldogs are the intercollegiate athletic teams that represent Yale University, located in New Haven, Connecticut. The school sponsors 35 varsity sports. The school has won two NCAA national championships in women's fencing, four in m ...

in the NCAA

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) is a nonprofit organization that regulates student athletics among about 1,100 schools in the United States, Canada, and Puerto Rico. It also organizes the athletic programs of colleges and ...

Division I – Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising eight private research universities in the Northeastern United States. The term ''Ivy League'' is typically used beyond the sports context to refer to the eight schoo ...

.

, 65 Nobel

Nobel often refers to:

*Nobel Prize, awarded annually since 1901, from the bequest of Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel

Nobel may also refer to:

Companies

*AkzoNobel, the result of the merger between Akzo and Nobel Industries in 1994

*Branobel, or ...

laureates, five Fields Medalists, four Abel Prize

The Abel Prize ( ; no, Abelprisen ) is awarded annually by the King of Norway to one or more outstanding mathematicians. It is named after the Norwegian mathematician Niels Henrik Abel (1802–1829) and directly modeled after the Nobel Pri ...

laureates, and three Turing Award

The ACM A. M. Turing Award is an annual prize given by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) for contributions of lasting and major technical importance to computer science. It is generally recognized as the highest distinction in compu ...

winners have been affiliated with Yale University. In addition, Yale has graduated many notable alumni, including five U.S. presidents, 10 Founding Fathers

The following list of national founding figures is a record, by country, of people who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e. ...

, 19 U.S. Supreme Court Justices, 31 living billionaires, 54 College founders and presidents, many heads of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

, cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

members and governors

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political r ...

. Hundreds of members of Congress

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivalen ...

and many U.S. diplomats, 78 MacArthur Fellows, 252 Rhodes Scholars

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world' ...

, 123 Marshall Scholars

The Marshall Scholarship is a postgraduate scholarship for "intellectually distinguished young Americans ndtheir country's future leaders" to study at any university in the United Kingdom. It is widely considered one of the most prestigious sc ...

, 102 Guggenheim Fellows and nine Mitchell Scholars have been affiliated with the university. Yale is a member of the Big Three, along with Harvard and Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ni ...

. Yale's current faculty include 67 members of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

, 55 members of the National Academy of Medicine

The National Academy of Medicine (NAM), formerly called the Institute of Medicine (IoM) until 2015, is an American nonprofit, non-governmental organization. The National Academy of Medicine is a part of the National Academies of Sciences, En ...

, 8 members of the National Academy of Engineering

The National Academy of Engineering (NAE) is an American nonprofit, non-governmental organization. The National Academy of Engineering is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of ...

, and 187 members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, ...

. The college is, after normalization for institution size, the tenth-largest baccalaureate source of doctoral degree

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism '' ...

recipients in the United States, and the largest such source within the Ivy League. It also is a top 10 (ranked seventh), after normalization for the number of graduates, baccalaureate source of some of the most notable scientists (Nobel, Fields, Turing prizes, or membership in National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Medicine, or National Academy of Engineering).

History

Early history of Yale College

Origins

Yale traces its beginnings to "An Act for Liberty to Erect a Collegiate School", a would-be charter passed during a meeting in New Haven by the General Court of the

Yale traces its beginnings to "An Act for Liberty to Erect a Collegiate School", a would-be charter passed during a meeting in New Haven by the General Court of the Colony of Connecticut

The ''Connecticut Colony'' or ''Colony of Connecticut'', originally known as the Connecticut River Colony or simply the River Colony, was an English colony in New England which later became Connecticut. It was organized on March 3, 1636 as a settl ...

on October 9, 1701. The Act was an effort to create an institution to train ministers and lay leadership for Connecticut. Soon after, a group of ten Congregational

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs it ...

ministers, Samuel Andrew

Samuel Andrew (29 January 1656 – 24 January 1738) was an American Congregational clergyman and educator.

Early life

Samuel was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the eldest child of Samuel and Elizabeth (nee White) Andrew. The elder Samu ...

, Thomas Buckingham, Israel Chauncy, Samuel Mather (nephew of Increase Mather

Increase Mather (; June 21, 1639 Old Style – August 23, 1723 Old Style) was a New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and president of Harvard College for twenty years (1681–1701). He was influential in the administrati ...

), Rev. James Noyes II (son of James Noyes

Rev. James Noyes (born 1608, Wiltshire, England – died 22 October 1656, Newbury, Massachusetts Bay Colony) was an English clergyman who emigrated to Massachusetts. He was a founder of Newbury, Massachusetts.

Biography

James Noyes was the fifth ...

), James Pierpont, Abraham Pierson

Abraham Pierson (1646 – March 5, 1707) was an American Congregational minister who served as the first rector, from 1701 to 1707, and one of the founders of the Collegiate School — which later became Yale University.

Biography

He was ...

, Noadiah Russell, Joseph Webb, and Timothy Woodbridge, all alumni

Alumni (singular: alumnus (masculine) or alumna (feminine)) are former students of a school, college, or university who have either attended or graduated in some fashion from the institution. The feminine plural alumnae is sometimes used for grou ...

of Harvard, met in the study of Reverend Samuel Russell, located in Branford, Connecticut, to donate their books to form the school's library. The group, led by James Pierpont, is now known as "The Founders".

Known from its origin as the "Collegiate School", the institution opened in the home of its first

Known from its origin as the "Collegiate School", the institution opened in the home of its first rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

, Abraham Pierson

Abraham Pierson (1646 – March 5, 1707) was an American Congregational minister who served as the first rector, from 1701 to 1707, and one of the founders of the Collegiate School — which later became Yale University.

Biography

He was ...

, who is today considered the first president of Yale. Pierson lived in Killingworth

Killingworth, formerly Killingworth Township, is a town in North Tyneside, England.

Killingworth was built as a planned town in the 1960s, next to Killingworth Village, which existed for centuries before the Township. Other nearby towns an ...

(now Clinton). The school moved to Saybrook in 1703 when the first treasurer of Yale, Nathaniel Lynde, donated land and a building. In 1716, it moved to New Haven, Connecticut.

Meanwhile, there was a rift forming at Harvard between its sixth president, Increase Mather

Increase Mather (; June 21, 1639 Old Style – August 23, 1723 Old Style) was a New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and president of Harvard College for twenty years (1681–1701). He was influential in the administrati ...

, and the rest of the Harvard clergy, whom Mather viewed as increasingly liberal, ecclesiastically lax, and overly broad in Church polity. The feud caused the Mathers to champion the success of the Collegiate School in the hope that it would maintain the Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

religious orthodoxy in a way that Harvard had not. Rev. Jason Haven, the minister at the First Church and Parish in Dedham

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

, Massachusetts had been considered for the presidency on account of his orthodox theology and for "Neatness dignity and purity of Style hichsurpass those of all that have been mentioned," but was passed over due to his "very Valetudinary and infirm State of Health."

Naming and development

In 1718, at the behest of either Rector

In 1718, at the behest of either Rector Samuel Andrew

Samuel Andrew (29 January 1656 – 24 January 1738) was an American Congregational clergyman and educator.

Early life

Samuel was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the eldest child of Samuel and Elizabeth (nee White) Andrew. The elder Samu ...

or the colony's Governor Gurdon Saltonstall

Gurdon Saltonstall (27 March 1666 – 20 September 1724) was governor of the Colony of Connecticut from 1708 to 1724. Born into a distinguished family, Saltonstall became an accomplished and eminent Connecticut pastor. A close associate of Gover ...

, Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a New England Puritan clergyman and a prolific writer. Educated at Harvard College, in 1685 he joined his father Increase as minister of the Congregationalist Old North Meetin ...

contacted the successful Boston-born businessman Elihu Yale

Elihu Yale (5 April 1649 – 8 July 1721) was a British-American colonial administrator and philanthropist. Although born in Boston, Massachusetts, he only lived in America as a child, spending the rest of his life in England, Wales and In ...

to ask him for financial help in constructing a new building for the college. Through the persuasion of Jeremiah Dummer, Yale, who had made a fortune in Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras (List of renamed Indian cities and states#Tamil Nadu, the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost states and territories of India, Indian state. The largest city ...

while working for the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sout ...

as the first president of Fort St. George (largely through secret contracts with Madras merchants that were illegal under Company policy), donated nine bales of goods, which were sold for more than £560, a substantial sum of money at the time. Cotton Mather suggested that the school change its name to "Yale College." The Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peopl ...

name Yale is the Anglicized spelling of the Iâl

Ial or Yale ( cy, Iâl) was a commote of medieval Wales within the cantref of Maelor in the Kingdom of Powys. When the Kingdom was divided in 1160, Maelor became part of the Princely realm of Powys Fadog (Lower Powys or Madog's Powys), and b ...

, which the family estate at Plas yn Iâl, near the village of Llandegla, was called.

Meanwhile, a Harvard graduate working in England convinced some 180 prominent intellectuals to donate books to Yale. The 1714 shipment of 500 books represented the best of modern English literature, science, philosophy and theology at the time. It had a profound effect on intellectuals at Yale. Undergraduate Jonathan Edwards discovered John Locke's works and developed his original theology known as the "new divinity." In 1722 the rector and six of his friends, who had a study group to discuss the new ideas, announced that they had given up Calvinism, become Arminians, and joined the Church of England. They were ordained in England and returned to the colonies as missionaries for the Anglican faith. Thomas Clapp became president in 1745 and while he attempted to return the college to Calvinist orthodoxy, he did not close the library. Other students found Deist books in the library.

Curriculum

Yale College undergraduates follow a

Yale College undergraduates follow a liberal arts

Liberal arts education (from Latin "free" and "art or principled practice") is the traditional academic course in Western higher education. ''Liberal arts'' takes the term '' art'' in the sense of a learned skill rather than specifically th ...

curriculum with departmental majors and is organized into a social system of residential colleges

A residential college is a division of a university that places academic activity in a community setting of students and faculty, usually at a residence and with shared meals, the college having a degree of autonomy and a federated relationship w ...

.

Yale was swept up by the great intellectual movements of the period—the Great Awakening

Great Awakening refers to a number of periods of religious revival in American Christian history. Historians and theologians identify three, or sometimes four, waves of increased religious enthusiasm between the early 18th century and the lat ...

and the Enlightenment—due to the religious and scientific interests of presidents Thomas Clap

Thomas Clap or Thomas Clapp (June 26, 1703 – January 7, 1767) was an American academic and educator, a Congregational minister, and college administrator. He was both the fifth rector and the earliest official to be called " president" of Yale ...

and Ezra Stiles

Ezra Stiles ( – May 12, 1795) was an American educator, academic, Congregationalist minister, theologian, and author. He is noted as the seventh president of Yale College (1778–1795) and one of the founders of Brown University. According ...

. They were both instrumental in developing the scientific curriculum at Yale while dealing with wars, student tumults, graffiti, "irrelevance" of curricula, desperate need for endowment and disagreements with the Connecticut legislature.

Serious American students of theology and divinity, particularly in New England, regarded Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

as a classical language

A classical language is any language with an independent literary tradition and a large and ancient body of written literature. Classical languages are typically dead languages, or show a high degree of diglossia, as the spoken varieties of the ...

, along with Greek and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

, and essential for the study of the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

in the original words. The Reverend Ezra Stiles

Ezra Stiles ( – May 12, 1795) was an American educator, academic, Congregationalist minister, theologian, and author. He is noted as the seventh president of Yale College (1778–1795) and one of the founders of Brown University. According ...

, president of the college from 1778 to 1795, brought with him his interest in the Hebrew language as a vehicle for studying ancient Biblical texts in their original language (as was common in other schools), requiring all freshmen to study Hebrew (in contrast to Harvard, where only upperclassmen were required to study the language) and is responsible for the Hebrew phrase אורים ותמים (Urim and Thummim

In the Hebrew Bible, the Urim ( he, ''ʾŪrīm'', "lights") and the Thummim ( he, ''Tummīm'', meaning uncertain, possibly "perfections") are elements of the '' hoshen'', the breastplate worn by the High Priest attached to the ephod. They ar ...

) on the Yale seal. A 1746 graduate of Yale, Stiles came to the college with experience in education, having played an integral role in the founding of Brown University, in addition to having been a minister. Stiles' greatest challenge occurred in July 1779 when British forces occupied New Haven and threatened to raze the college. However, Yale graduate Edmund Fanning, secretary to the British general in command of the occupation, intervened and the college was saved. In 1803, Fanning was granted an honorary degree LL.D. for his efforts.

Students

As the only college in Connecticut from 1701 to 1823, Yale educated the sons of the elite. Punishable offenses for students included cardplaying, tavern-going, destruction of college property, and acts of disobedience to college authorities. During this period, Harvard was distinctive for the stability and maturity of its tutor corps, while Yale had youth and zeal on its side. The emphasis on classics gave rise to a number of private student societies, open only by invitation, which arose primarily as forums for discussions of modern scholarship, literature and politics. The first such organizations were debating societies: Crotonia in 1738, Linonia in 1753 andBrothers in Unity

Brothers in Unity (formally, the Society of Brothers in Unity) is an undergraduate society at Yale University. Founded in 1768 as a literary and debating society that encompassed nearly half the student body at its 19th-century peak, the group di ...

in 1768. Linonia and Brothers in Unity continue to exist today with commemorations to them can be found with names given to campus structures, like Brothers in Unity Courtyard in Branford College.

19th century

The

The Yale Report of 1828 {{citations, date=February 2014

The Yale Report of 1828 is a document written by the faculty of Yale College in staunch defense of the classical curriculum. The report maintained that because of Yale's primary object of graduating well-educated and ...

was a dogmatic defense of the Latin and Greek curriculum against critics who wanted more courses in modern languages, mathematics, and science. Unlike higher education in Europe

The European Higher Education Area (EHEA) was launched in March 2010, during the Budapest-Vienna Ministerial Conference, on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the Bologna Process.

As the main objective of the Bologna Process since its ince ...

, there was no national curriculum A national curriculum is a common programme of study in schools that is designed to ensure nationwide uniformity of content and standards in education. It is usually legislated by the national government, possibly in consultation with state or other ...

for colleges and universities in the United States. In the competition for students and financial support, college leaders strove to keep current with demands for innovation. At the same time, they realized that a significant portion of their students and prospective students demanded a classical background. The Yale report meant the classics would not be abandoned. During this period, all institutions experimented with changes in the curriculum, often resulting in a dual-track curriculum. In the decentralized environment of higher education in the United States, balancing change with tradition was a common challenge because it was difficult for an institution to be completely modern or completely classical. A group of professors at Yale and New Haven Congregationalist ministers articulated a conservative response to the changes brought about by the Victorian culture

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardian ...

. They concentrated on developing a person possessed of religious values strong enough to sufficiently resist temptations from within, yet flexible enough to adjust to the ' isms' (professionalism

A professional is a member of a profession or any person who works in a specified professional activity. The term also describes the standards of education and training that prepare members of the profession with the particular knowledge and ski ...

, materialism

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical material ...

, individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-relia ...

, and consumerism

Consumerism is a social and economic order that encourages the acquisition of goods and services in ever-increasing amounts. With the Industrial Revolution, but particularly in the 20th century, mass production led to overproduction—the ...

) tempting him from without. William Graham Sumner

William Graham Sumner (October 30, 1840 – April 12, 1910) was an American clergyman, social scientist, and classical liberal. He taught social sciences at Yale University—where he held the nation's first professorship in sociology—and becam ...

, professor from 1872 to 1909, taught in the emerging disciplines of economics and sociology to overflowing classrooms of students. Sumner bested President Noah Porter

Noah Thomas Porter III (December 14, 1811 – March 4, 1892)''Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University'', Yale University, 1891-2, New Haven, pp. 82-83. was an American Congregational minister, academic, philosopher, author, lexicographer ...

, who disliked the social sciences and wanted Yale to lock into its traditions of classical education. Porter objected to Sumner's use of a textbook by Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest ...

that espoused agnostic materialism because it might harm students.

Until 1887, the legal name of the university was "The President and Fellows of Yale College, in New Haven." In 1887, under an act passed by the Connecticut General Assembly

The Connecticut General Assembly (CGA) is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is a bicameral body composed of the 151-member House of Representatives and the 36-member Senate. It meets in the state capital, Hartford. ...

, Yale was renamed to the present "Yale University."

Sports and debate

The Revolutionary War soldierNathan Hale

Nathan Hale (June 6, 1755 – September 22, 1776) was an American Patriot, soldier and spy for the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He volunteered for an intelligence-gathering mission in New York City but was captured ...

(Yale 1773) was the archetype of the Yale ideal in the early 19th century: a manly yet aristocratic scholar, equally well-versed in knowledge and sports, and a patriot who "regretted" that he "had but one life to lose" for his country. Western painter Frederic Remington

Frederic Sackrider Remington (October 4, 1861 – December 26, 1909) was an American painter, illustrator, sculptor, and writer who specialized in the genre of Western American Art. His works are known for depicting the Western United Stat ...

(Yale 1900) was an artist whose heroes gloried in the combat and tests of strength in the Wild West. The fictional, turn-of-the-20th-century Yale man Frank Merriwell

Frank Merriwell is a fictional character appearing in a series of novels and short stories by Gilbert Patten, who wrote under the pseudonym Burt L. Standish. The character appeared in over 300 dime novels between 1896 and 1930 (some between 1927 ...

embodied this same heroic ideal without racial prejudice, and his fictional successor Frank Stover in the novel ''Stover at Yale'' (1911) questioned the business mentality that had become prevalent at the school. Increasingly the students turned to athletic stars as their heroes, especially since winning the big game became the goal of the student body, the alumni, and the team itself.

Along with Harvard and

Along with Harvard and Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ni ...

, Yale students rejected British concepts about 'amateurism

An amateur () is generally considered a person who pursues an avocation independent from their source of income. Amateurs and their pursuits are also described as popular, informal, self-taught, user-generated, DIY, and hobbyist.

History

Hi ...

' in sports and constructed athletic programs that were uniquely American, such as football. The Harvard–Yale football rivalry began in 1875. Between 1892, when Harvard and Yale met in one of the first intercollegiate debates

Debate is a process that involves formal discourse on a particular topic, often including a Discussion moderator, moderator and audience. In a debate, arguments are put forward for often opposing viewpoints. Debates have historically occurred ...

, and in 1909 (the year of the first Triangular Debate of Harvard, Yale and Princeton) the rhetoric, symbolism, and metaphors used in athletics were used to frame these early debates. Debates were covered on front pages of college newspaper

A student publication is a media outlet such as a newspaper, magazine, television show, or radio station produced by students at an educational institution. These publications typically cover local and school-related news, but they may also repo ...

s and emphasized in yearbook

A yearbook, also known as an annual, is a type of a book published annually. One use is to record, highlight, and commemorate the past year of a school. The term also refers to a book of statistics or facts published annually. A yearbook often ...

s, and team members even received the equivalent of athletic letters for their jackets. There were also rallies to send off the debating teams to matches, but the debates never attained the broad appeal that athletics enjoyed. One reason may be that debates do not have a clear winner, as is the case in sports, and that scoring is subjective. In addition, with late 19th-century concerns about the impact of modern life on the human body, athletics offered hope that neither the individual nor the society was coming apart.

In 1909–10, football faced a crisis resulting from the failure of the previous reforms of 1905–06, which sought to solve the problem of serious injuries. There was a mood of alarm and mistrust, and, while the crisis was developing, the presidents of Harvard, Yale, and Princeton developed a project to reform the sport and forestall possible radical changes forced by government upon the sport. Presidents Arthur Hadley of Yale, A. Lawrence Lowell of Harvard, and Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of P ...

of Princeton worked to develop moderate reforms to reduce injuries. Their attempts, however, were reduced by rebellion against the rules committee and the formation of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association. While the big three had attempted to operate independently of the majority, the changes pushed did reduce injuries.

Expansion

Starting with the addition of theYale School of Medicine

The Yale School of Medicine is the graduate medical school at Yale University, a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. It was founded in 1810 as the Medical Institution of Yale College and formally opened in 1813.

The primary t ...

in 1810, the college expanded gradually from then on, establishing the Yale Divinity School

Yale Divinity School (YDS) is one of the twelve graduate and professional schools of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

Congregationalist theological education was the motivation at the founding of Yale, and the professional school has ...

in 1822, Yale Law School

Yale Law School (Yale Law or YLS) is the law school of Yale University, a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. It was established in 1824 and has been ranked as the best law school in the United States by '' U.S. News & Worl ...

in 1822, the Yale Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in 1847, the now-defunct Sheffield Scientific School

Sheffield Scientific School was founded in 1847 as a school of Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut, for instruction in science and engineering. Originally named the Yale Scientific School, it was renamed in 1861 in honor of Joseph E. Sheffield ...

in 1847,Sheffield was originally named Yale Scientific School; it was renamed in 1861 after a major donation from Joseph E. Sheffield. and the Yale School of Fine Arts in 1869. In 1887, under the presidency of Timothy Dwight V, Yale College was renamed to Yale University, and the former name was subsequently applied only to the undergraduate college. The university would continue to expand greatly into the 20th and 21st century, adding the Yale School of Music

The Yale School of Music (often abbreviated to YSM) is one of the 12 professional schools at Yale University. It offers three graduate degrees: Master of Music (MM), Master of Musical Arts (MMA), and Doctor of Musical Arts (DMA), as well as a jo ...

in 1894, the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies in 1900, the Yale School of Public Health in 1915, the Yale School of Architecture in 1916, the Yale School of Nursing 1923, the Yale School of Drama

The David Geffen School of Drama at Yale University is a graduate professional school of Yale University, located in New Haven, Connecticut. Founded in 1924 as the Department of Drama in the School of Fine Arts, the school provides training in e ...

in 1955, the Yale School of Management

The Yale School of Management (also known as Yale SOM) is the graduate business school of Yale University, a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. The school awards the Master of Business Administration (MBA), MBA for Executive ...

in 1976, and the Jackson School of Global Affairs which is planned to open in 2022. The Sheffield Scientific School would also reorganize its relationship with the university to teach only undergraduate courses.

Expansion caused controversy about Yale's new roles. Noah Porter

Noah Thomas Porter III (December 14, 1811 – March 4, 1892)''Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University'', Yale University, 1891-2, New Haven, pp. 82-83. was an American Congregational minister, academic, philosopher, author, lexicographer ...

, a moral philosopher, was president from 1871 to 1886. During an age of tremendous expansion in higher education, Porter resisted the rise of the new research university, claiming that an eager embrace of its ideals would corrupt undergraduate education. Many of Porter's contemporaries criticized his administration, and historians since have disparaged his leadership. Historian George Levesque argues Porter was not a simple-minded reactionary, uncritically committed to tradition, but a principled and selective conservative. Levesque continues, saying he did not endorse everything old or reject everything new; rather, he sought to apply long-established ethical and pedagogical principles to a rapidly changing culture. Levesque concludes, noting he may have misunderstood some of the challenges of his time, but he correctly anticipated the enduring tensions that have accompanied the emergence and growth of the modern university.

20th century

Medicine

Milton Winternitz led the

Milton Winternitz led the Yale School of Medicine

The Yale School of Medicine is the graduate medical school at Yale University, a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. It was founded in 1810 as the Medical Institution of Yale College and formally opened in 1813.

The primary t ...

as its dean from 1920 to 1935. Dedicated to the new scientific medicine established in Germany, he was equally fervent about "social medicine" and the study of humans in their culture and environment. He established the "Yale System" of teaching, with few lectures and fewer exams, and strengthened the full-time faculty system; he also created the graduate-level Yale School of Nursing and the psychiatry department and built numerous new buildings. Progress toward his plans for an Institute of Human Relations, envisioned as a refuge where social scientists would collaborate with biological scientists in a holistic study of humankind, unfortunately, lasted for only a few years before the opposition of resentful anti-Semitic colleagues drove him to resign.

Faculty

Before

Before World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, most elite university faculties counted among their numbers few, if any, Jews, blacks, women, or other minorities; Yale was no exception. By 1980, this condition had been altered dramatically, as numerous members of those groups held faculty positions. Almost all members of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences—and some members of other faculties—teach undergraduate courses, more than 2,000 of which are offered annually.

Women

In 1793,Lucinda Foote

Lucinda Foote is best known for attempting to study at Yale College (now University) in 1783, some 186 years prior to women being admitted. Her name was later used by protesters supporting the admission of women to the University in 1963.

Biograph ...

passed the entrance exams for Yale College, but was rejected by the president on the basis of her gender. Women studied at Yale University as early as 1892, in graduate-level programs at the Yale Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. The first seven women to earn PhDs at Yale received their degrees in 1894: Elizabeth Deering Hanscom

Elizabeth Deering Hanscom (August 15, 1865 – February 2, 1960) was an American writer and college professor. In 1894, she was in the first group of seven women granted doctoral degrees at Yale University, and she taught English at Smith Colle ...

, Cornelia H. B. Rogers, Sara Bulkley Rogers, Margaretta Palmer

Margaretta Palmer (1862–1924) was an American astronomer, one of the first women to earn a doctorate in astronomy.

She worked at the Yale University Observatory at a time when woman were frequently hired as assistant astronomers, but when most of ...

, Mary Augusta Scott, Laura Johnson Wylie, and Charlotte Fitch Roberts. There is a portrait of these seven women in Sterling Memorial Library

Sterling Memorial Library (SML) is the main library building of the Yale University Library system in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Opened in 1931, the library was designed by James Gamble Rogers as the centerpiece of Yale's Gothic Re ...

, painted by Brenda Zlamany

Brenda Zlamany is an American artist best known for portraiture that combines Old Master technique with a Postmodernism, postmodern conceptual approach.Schwabsky, Barry"Brenda Zlamany / E. M. Donahue Gallery,"''Artforum'', February 1993, p. 99� ...

.

In 1966, Yale began discussions with its sister school

A sister school is usually a pair of schools, usually single-sex school, one with female students and the other with male students. This relationship is seen to benefit both schools. For instance, when Harvard University was a male-only school, Ra ...

Vassar College

Vassar College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Poughkeepsie, New York, United States. Founded in 1861 by Matthew Vassar, it was the second degree-granting institution of higher education for women in the United States, closely fol ...

about merging to foster coeducation at the undergraduate level. Vassar, then all-female and part of the Seven Sisters—elite higher education schools that historically served as sister institutions to the Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising eight private research universities in the Northeastern United States. The term ''Ivy League'' is typically used beyond the sports context to refer to the eight schoo ...

when most Ivy League institutions still only admitted men—tentatively accepted, but then declined the invitation. Both schools introduced coeducation independently in 1969. Amy Solomon was the first woman to register as a Yale undergraduate; she was also the first woman at Yale to join an undergraduate society, St. Anthony Hall

St. Anthony Hall or the Fraternity of Delta Psi is an American fraternity and literary society. Its first chapter was founded at Columbia University on , the feast day of Saint Anthony the Great. The fraternity is a non–religious, nonsectari ...

. The undergraduate class of 1973 was the first class to have women starting from freshman year; at the time, all undergraduate women were housed in Vanderbilt Hall at the south end of Old Campus

The Old Campus is the oldest area of the Yale University campus in New Haven, Connecticut. It is the principal residence of Yale College freshmen and also contains offices for the academic departments of Classics, English, History, Comparative Li ...

.

A decade into co-education, student assault and harassment by faculty became the impetus for the trailblazing lawsuit Alexander v. Yale

''Alexander v. Yale'', 631 F.2d 178 (2d Cir. 1980), was the first use of Title IX of the United States Education Amendments of 1972 in charges of sexual harassment against an educational institution. It further established that sexual harassment ...

. In the late 1970s, a group of students and one faculty member sued Yale for its failure to curtail campus sexual harassment by especially male faculty. The case was partly built from a 1977 report authored by plaintiff Ann Olivarius, now a feminist attorney known for fighting sexual harassment, "A report to the Yale Corporation from the Yale Undergraduate Women's Caucus." This case was the first to use Title IX

Title IX is the most commonly used name for the federal civil rights law in the United States that was enacted as part (Title IX) of the Education Amendments of 1972. It prohibits sex-based discrimination in any school or any other educa ...

to argue and establish that the sexual harassment of female students can be considered illegal sex discrimination. The plaintiffs in the case were Olivarius, Ronni Alexander (now a professor at Kobe University

, also known in the Kansai region as , is a leading Japanese national university located in the city of Kobe, in Hyōgo. It was established in 1949, but the academic origins of Kobe University trace back to the establishment of Kobe Higher Com ...

, Japan), Margery Reifler (works in the Los Angeles film industry)Pamela Price

(civil rights attorney in California), and Lisa E. Stone (works at

Anti-Defamation League

The Anti-Defamation League (ADL), formerly known as the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith, is an international Jewish non-governmental organization based in the United States specializing in civil rights law. It was founded in late Septe ...

). They were joined by Yale classics professor John “Jack” J. Winkler, who died in 1990. The lawsuit, brought partly by Catharine MacKinnon

Catharine Alice MacKinnon (born October 7, 1946) is an American radical feminist legal scholar, activist, and author. She is the Elizabeth A. Long Professor of Law at the University of Michigan Law School, where she has been tenured since 1990, ...

, alleged rape, fondling, and offers of higher grades for sex by several Yale faculty, including Keith Brion, professor of flute and director of bands, political Science professoRaymond Duvall

(now at the

University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul, Tw ...

), English professor Michael Cooke, and coach of the field hockey team, Richard Kentwell. While unsuccessful in the courts, the legal reasoning behind the case changed the landscape of sex discrimination law and resulted in the establishment of Yale's Grievance Board and the Yale Women's Center. In March 2011 a Title IX

Title IX is the most commonly used name for the federal civil rights law in the United States that was enacted as part (Title IX) of the Education Amendments of 1972. It prohibits sex-based discrimination in any school or any other educa ...

complaint was filed against Yale by students and recent graduates, including editors of Yale's feminist magazine Broad Recognition, alleging that the university had a hostile sexual climate. In response, the university formed a Title IX steering committee to address complaints of sexual misconduct. Afterwards, universities and colleges throughout the US also established sexual harassment grievance procedures.

Class

Yale, like other Ivy League schools, instituted policies in the early 20th century designed to maintain the proportion of white Protestants from notable families in the student body (see ''numerus clausus

''Numerus clausus'' ("closed number" in Latin) is one of many methods used to limit the number of students who may study at a university. In many cases, the goal of the ''numerus clausus'' is simply to limit the number of students to the maximum ...

''), and was one of the last of the Ivies to eliminate such preferences, beginning with the class of 1970.

21st century

In 2006, Yale andPeking University

Peking University (PKU; ) is a public research university in Beijing, China. The university is funded by the Ministry of Education.

Peking University was established as the Imperial University of Peking in 1898 when it received its royal charte ...

(PKU) established a Joint Undergraduate Program in Beijing, an exchange program allowing Yale students to spend a semester living and studying with PKU honor students. In July 2012, the Yale University-PKU Program ended due to weak participation.

In 2007 outgoing Yale President Rick Levin characterized Yale's institutional priorities: "First, among the nation's finest research universities, Yale is distinctively committed to excellence in undergraduate education. Second, in our graduate and professional schools, as well as in Yale College, we are committed to the education of leaders."

In 2009, former British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern ...

Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of the ...

picked Yale as one location – the others being Britain's Durham University and Universiti Teknologi Mara

The MARA Technological University ( Malay: ''Universiti Teknologi MARA''; Jawi: اونيۏرسيتي تيكنولوڬي مارا; abbr. UiTM) is a public university based primarily in Shah Alam, Selangor. It was established to help rural Mala ...

– for the Tony Blair Faith Foundation's United States Faith and Globalization Initiative. As of 2009, former Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo

Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de León (; born 27 December 1951) is a Mexican economist and politician. He was 61st president of Mexico from 1 December 1994 to 30 November 2000, as the last of the uninterrupted 71-year line of Mexican presidents from t ...

is the director of the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization and teaches an undergraduate seminar, "Debating Globalization". As of 2009, former presidential candidate and DNC chair Howard Dean

Howard Brush Dean III (born November 17, 1948) is an American physician, author, lobbyist, and retired politician who served as the 79th governor of Vermont from 1991 to 2003 and chair of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) from 2005 to 200 ...

teaches a residential college seminar, "Understanding Politics and Politicians". Also in 2009, an alliance was formed among Yale, University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = � ...

, and both schools' affiliated hospital complexes to conduct research focused on the direct improvement of patient care—a growing field known as translational medicine. President Richard Levin noted that Yale has hundreds of other partnerships across the world, but "no existing collaboration matches the scale of the new partnership with UCL".

In August 2013, a new partnership with the National University of Singapore

The National University of Singapore (NUS) is a national public research university in Singapore. Founded in 1905 as the Straits Settlements and Federated Malay States Government Medical School, NUS is the oldest autonomous university in th ...

led to the opening of Yale-NUS College

Yale-NUS College is a liberal arts college in Singapore. Established in 2011 as a collaboration between Yale University and the National University of Singapore, it was the first liberal arts college in Singapore and one of the first few in Asia ...

in Singapore, a joint effort to create a new liberal arts college in Asia featuring a curriculum including both Western and Asian traditions.

In 2017, having been suggested for decades, Yale University renamed Calhoun College, named for slave owner, anti-abolitionist, and white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

Vice President John C. Calhoun (it is now Hopper College, after Grace Hopper

Grace Brewster Hopper (; December 9, 1906 – January 1, 1992) was an American computer scientist, mathematician, and United States Navy rear admiral. One of the first programmers of the Harvard Mark I computer, she was a pioneer of compu ...

).

In 2020, in the wake of protests around the world focused on racial relations and criminal justice reform, the #CancelYale tag was used on social media to demand that Elihu Yale's name be removed from Yale University. Most support for the change stemmed from politically conservative pundits, such as Mike Cernovich and Ann Coulter

Ann Hart Coulter (; born December 8, 1961) is an American conservative media pundit, author, syndicated columnist, and lawyer. She became known as a media pundit in the late 1990s, appearing in print and on cable news as an outspoken critic ...

, satirizing perceived excesses of online cancel culture

Cancel culture, or rarely also known as call-out culture, is a phrase contemporary to the late 2010s and early 2020s used to refer to a form of ostracism in which someone is thrust out of social or professional circles—whether it be online, o ...

. Yale was president of Fort. St George in Madras, a fort of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sout ...

in India, which was one of the biggest corporation in the world at the time. The company traded textiles, goods, diamonds, cotton, spices, among others, and was involved in the slave trade in India, with a private army of 260,000 soldiers, twice the size of Britain.

His singularly large donation of paintings and books to the college led some critics to argue that Yale relied on money related to the slave-trade for its first scholarships and endowments.

In August 2020, the US Justice Department sued Yale for alleged discrimination against Asian and white candidates on the basis of their race through affirmative action admission policies. In early February 2021, under the new Biden administration, the Justice Department withdrew the lawsuit. The group, Students for Fair Admissions, known for a similar lawsuit against Harvard alleging the same issue, plans to refile the lawsuit.

Yale alumni in politics

The ''Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

'' wrote that "if there's one school that can lay claim to educating the nation's top national leaders over the past three decades, it's Yale".''Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

'' November 17, 2002, Magazine, p. 6 Yale alumni

Yalies are persons affiliated with Yale University, commonly including alumni, current and former faculty members, students, and others. Here follows a list of notable Yalies.

Alumni

For a list of notable alumni of Yale Law School, see List ...

were represented on the Democratic

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

or Republican ticket in every U.S. presidential election between 1972 and 2004. Yale-educated presidents since the end of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

include Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (Birth name, né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 ...

, and George W. Bush, and major-party nominees during this period include Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States senat ...

(2016), John Kerry

John Forbes Kerry (born December 11, 1943) is an American attorney, politician and diplomat who currently serves as the first United States special presidential envoy for climate. A member of the Forbes family and the Democratic Party (Unite ...

(2004), Joseph Lieberman

Joseph Isadore Lieberman (; born February 24, 1942) is an American politician, lobbyist, and attorney who served as a United States senator from Connecticut from 1989 to 2013. A former member of the Democratic Party, he was its nominee for Vi ...

(vice president, 2000), and Sargent Shriver

Robert Sargent Shriver Jr. (November 9, 1915 – January 18, 2011) was an American diplomat, politician, and activist. As the husband of Eunice Kennedy Shriver, he was part of the Kennedy family. Shriver was the driving force behind the creatio ...

(vice president, 1972). Other Yale alumni who have made serious bids for the presidency during this period include Amy Klobuchar (2020), Tom Steyer

Thomas Fahr Steyer (born June 27, 1957) is an American climate investor, businessman, hedge fund manager, philanthropist, environmentalist, and liberal activist. Steyer is the co-founder and co-chair of Galvanize Climate Solutions, founder an ...

(2020), Ben Carson

Benjamin Solomon Carson Sr. (born September 18, 1951) is an American retired neurosurgeon and politician who served as the 17th United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development from 2017 to 2021. A pioneer in the field of neurosurgery, ...

(2016), Howard Dean

Howard Brush Dean III (born November 17, 1948) is an American physician, author, lobbyist, and retired politician who served as the 79th governor of Vermont from 1991 to 2003 and chair of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) from 2005 to 200 ...

(2004), Gary Hart

Gary Warren Hart ('' né'' Hartpence; born November 28, 1936) is an American politician, diplomat, and lawyer. He was the front-runner for the 1988 Democratic presidential nomination until he dropped out amid revelations of extramarital affairs ...

(1984 and 1988), Paul Tsongas

Paul Efthemios Tsongas (; February 14, 1941 – January 18, 1997) was an American politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1979 until 1985 and in the United States House of Representatives from 1975 until 197 ...

(1992), Pat Robertson

Marion Gordon "Pat" Robertson (born March 22, 1930) is an American media mogul, religious broadcaster, political commentator, former presidential candidate, and former Southern Baptist minister. Robertson advocates a conservative Christian ...

(1988) and Jerry Brown

Edmund Gerald Brown Jr. (born April 7, 1938) is an American lawyer, author, and politician who served as the 34th and 39th governor of California from 1975 to 1983 and 2011 to 2019. A member of the Democratic Party, he was elected Secretary of S ...

(1976, 1980, 1992).

Several explanations have been offered for Yale's representation in national elections since the end of the Vietnam War. Various sources note the spirit of campus activism that has existed at Yale since the 1960s, and the intellectual influence of Reverend William Sloane Coffin

William Sloane Coffin Jr. (June 1, 1924 – April 12, 2006) was an American Christian clergyman and long-time peace activist. He was ordained in the Presbyterian Church, and later received ministerial standing in the United Church of Christ. In h ...

on many of the future candidates.''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

'' October 4, 2000, p. E1 Yale President Richard Levin attributes the run to Yale's focus on creating "a laboratory for future leaders," an institutional priority that began during the tenure of Yale Presidents Alfred Whitney Griswold and Kingman Brewster. Richard H. Brodhead, former dean of Yale College and now president of Duke University, stated: "We do give very significant attention to orientation to the community in our admissions, and there is a very strong tradition of volunteerism

Volunteering is a voluntary act of an individual or group freely giving time and labor for community service. Many volunteers are specifically trained in the areas they work, such as medicine, education, or emergency rescue. Others serve ...

at Yale." Yale historian Gaddis Smith notes "an ethos of organized activity" at Yale during the 20th century that led John Kerry to lead the Yale Political Union

The Yale Political Union (YPU) is a debate society at Yale University, founded in 1934 by Alfred Whitney Griswold. It was modeled on the Cambridge Union and Oxford Union and the party system of the defunct Yale Unions of the late nineteenth and ...

's Liberal Party, George Pataki

George Elmer Pataki (; born June 24, 1945) is an American lawyer and politician who served as the 53rd governor of New York from 1995 to 2006. An attorney by profession, Pataki was elected mayor of his hometown of Peekskill, New York, and went ...

the Conservative Party, and Joseph Lieberman to manage the ''Yale Daily News

The ''Yale Daily News'' is an independent student newspaper published by Yale University students in New Haven, Connecticut since January 28, 1878. It is the oldest college daily newspaper in the United States. The ''Yale Daily News'' has consi ...

''. Camille Paglia

Camille Anna Paglia (; born April 2, 1947) is an American feminist academic and social critic. Paglia has been a professor at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, since 1984. She is critical of many aspects of modern cultur ...

points to a history of networking and elitism: "It has to do with a web of friendships and affiliations built up in school." CNN suggests that George W. Bush benefited from preferential admissions policies for the "son and grandson of alumni", and for a "member of a politically influential family". ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' correspondent Elisabeth Bumiller and ''The Atlantic Monthly

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher. It features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 in Boston, ...

'' correspondent James Fallows

James Mackenzie Fallows (born August 2, 1949) is an American writer and journalist. He is a former national correspondent for ''The Atlantic.'' His work has also appeared in ''Slate'', ''The New York Times Magazine'', ''The New York Review of Book ...

credit the culture of community and cooperation that exists between students, faculty, and administration, which downplays self-interest and reinforces commitment to others.

During the 1988 presidential election, George H. W. Bush (Yale '48) derided Michael Dukakis

Michael Stanley Dukakis (; born November 3, 1933) is an American retired lawyer and politician who served as governor of Massachusetts from 1975 to 1979 and again from 1983 to 1991. He is the longest-serving governor in Massachusetts history a ...

for having "foreign-policy views born in Harvard Yard's boutique". When challenged on the distinction between Dukakis' Harvard connection and his own Yale background, he said that, unlike Harvard, Yale's reputation was "so diffuse, there isn't a symbol, I don't think, in the Yale situation, any symbolism in it" and said Yale did not share Harvard's reputation for "liberalism and elitism". In 2004 Howard Dean

Howard Brush Dean III (born November 17, 1948) is an American physician, author, lobbyist, and retired politician who served as the 79th governor of Vermont from 1991 to 2003 and chair of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) from 2005 to 200 ...

stated, "In some ways, I consider myself separate from the other three (Yale) candidates of 2004. Yale changed so much between the class of '68 and the class of '71. My class was the first class to have women in it; it was the first class to have a significant effort to recruit African Americans. It was an extraordinary time, and in that span of time is the change of an entire generation".

Administration and organization

Leadership

The President and Fellows of Yale College, also known as the Yale Corporation, or board of trustees, is the governing body of the university and consists of thirteen standing committees with separate responsibilities outlined in the by-laws. The corporation has 19 members: three ex officio members, ten successor trustees, and six elected alumni fellows. The university has three major academic components: Yale College (the undergraduate program), the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and the twelve professional schools. Yale's former president Richard C. Levin was, at the time, one of the highest paid university presidents in the United States with a 2008 salary of $1.5 million. Yale's succeeding president Peter Salovey ranks 40th with a 2020 salary of $1.16 million. The Yale Provost's Office and similar executive positions have launched several women into prominent university executive positions. In 1977, ProvostHanna Holborn Gray

Hanna Holborn Gray (born October 25, 1930) is an American historian of Renaissance and Reformation political thought and Professor of History ''Emerita'' at the University of Chicago. She served as president of the University of Chicago, from 197 ...

was appointed interim president of Yale and later went on to become president of the University of Chicago, being the first woman to hold either position at each respective school. In 1994, Provost Judith Rodin became the first permanent female president of an Ivy League institution at the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universit ...

. In 2002, Provost Alison Richard

Dame Alison Fettes Richard, (born 1 March 1948) is an English anthropologist, conservationist and university administrator. She was the 344th Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, the third Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge since the po ...

became the vice-chancellor of the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

. In 2003, the dean of the Divinity School, Rebecca Chopp

Rebecca S. Chopp (born 1952) is an academic administrator and professor. She was the 18th chancellor of the University of Denver, and the first female chancellor in the institution's history. Prior to that, Chopp was a president of Swarthmore Colle ...

, was appointed president of Colgate University and later went on to serve as the president of the Swarthmore College

Swarthmore College ( , ) is a private liberal arts college in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1864, with its first classes held in 1869, Swarthmore is one of the earliest coeducational colleges in the United States. It was established as ...

in 2009, and then the first female chancellor of the University of Denver

The University of Denver (DU) is a private research university in Denver, Colorado. Founded in 1864, it is the oldest independent private university in the Rocky Mountain Region of the United States. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Univ ...

in 2014. In 2004, Provost Dr. Susan Hockfield became the president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a Private university, private Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern t ...

. In 2004, Dean of the Nursing school, Catherine Gilliss, was appointed the dean of Duke University's School of Nursing and vice chancellor for nursing affairs. In 2007, Deputy Provost H. Kim Bottomly was named president of Wellesley College

Wellesley College is a private women's liberal arts college in Wellesley, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1870 by Henry and Pauline Durant as a female seminary, it is a member of the original Seven Sisters Colleges, an unofficia ...

.