World War III or the Third World War, often abbreviated as WWIII or WW3, are names given to a hypothetical

worldwide large-scale military conflict subsequent to

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. The term has been in use since at least as early as 1941.

Some apply it loosely to limited or more minor conflicts such as the

Cold War or the

war on terror

The war on terror, officially the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), is an ongoing international counterterrorism military campaign initiated by the United States following the September 11 attacks. The main targets of the campaign are militant ...

. In contrast, others assume that such a conflict would surpass prior world wars in both scope and destructive impact.

[''The New Quotable Einstein''. Alice Calaprice (2005), p. 173.]

Due to the development of

nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s in the

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, which were used in the

atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki near the end of World War II, and their subsequent acquisition and deployment by

many countries afterward, the potential risk of a

nuclear apocalypse causing widespread destruction of Earth's civilization and life is a common theme in speculations about a third world war. Another primary concern is that

biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. ...

could cause many casualties. It could happen intentionally or inadvertently, by an accidental release of a biological agent, the unexpected mutation of an agent, or its adaptation to other species after use. Large-scale

apocalyptic events like these, caused by advanced technology used for destruction, could render most of

Earth's surface

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surface ...

uninhabitable.

Before the beginning of World War II in 1939, World War I (1914–1918) was believed to have been "

the war to end llwars". It was popularly believed that never again could there possibly be a global conflict of such magnitude. During the

interwar period, World War I was typically referred to simply as "The Great War". The outbreak of World War II disproved the hope that humanity might have "outgrown" the need for widespread global wars.

With the advent of the Cold War in 1945 and with the spread of nuclear weapons technology to the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, the possibility of a third global conflict increased. During the Cold War years, the possibility of a third world war was anticipated and planned for by military and civil authorities in many countries. Scenarios ranged from

conventional warfare

Conventional warfare is a form of warfare conducted by using conventional weapons and battlefield tactics between two or more states in open confrontation. The forces on each side are well-defined and fight by using weapons that target primari ...

to limited or total nuclear warfare. At the height of the Cold War, the doctrine of

mutually assured destruction

Mutual assured destruction (MAD) is a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy which posits that a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by an attacker on a nuclear-armed defender with second-strike capabilities would cause the ...

(MAD), which determined that an all-out nuclear confrontation would destroy all of the states involved in the conflict, had been developed. The potential for the absolute destruction of the human species may have contributed to the ability of both American and Soviet leaders to avoid such a scenario.

The various global military conflicts that have occurred since the start of the 21st century, most recently the

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which began in 2014. The invasion has resulted in tens of thousands of deaths on both sides. It has caused Europe's largest refugee crisis since World War II. ...

, have been hypothesized as potential flashpoints or triggers for a third world war.

Etymology

''Time'' magazine

''

Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'' magazine was an early adopter, if not originator, of the term "World WarIII". The first usage appears in its 3 November 1941 issue (preceding the Japanese

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

on 7 December 1941) under its "National Affairs" section and entitled "World WarIII?" about

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

refugee Dr.

Hermann Rauschning

Hermann Adolf Reinhold Rauschning (7 August 1887 – February 8, 1982) was a German politician and author, adherent of the Conservative Revolution movement who briefly joined the Nazi movement before breaking with it. He was the President of the ...

, who had just arrived in the United States.

In its 22 March 1943, issue under its "Foreign News" section, ''Time'' reused the same title "World WarIII?" about statements by then-

U.S. Vice President Henry A. Wallace: "We shall decide sometime in 1943 or 1944... whether to plant the seeds of World War III." ''Time'' continued to entitle with or mention in stories the term "World WarIII" for the rest of the decade and onwards: 1944, 1945, 1946 ("bacterial warfare"), 1947, and 1948. ''Time'' persists in using this term, for example, in a 2015 book review entitled "This Is What World War III Will Look Like".

Military plans

Military strategists have used war games to prepare for various war scenarios and to determine the most appropriate strategies. War games were utilized for World War I and World War II.

Operation Unthinkable

British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As moder ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

was concerned that, with the enormous size of Soviet

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

forces deployed in

Central and Eastern Europe at the

end of World War II and the unreliability of the Soviet leader

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

, there was a serious threat to

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. In April–May 1945, the

British Armed Forces developed

Operation Unthinkable, thought to be the first scenario of the Third World War. Its primary goal was "to impose upon Russia the will of the United States and the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

". The plan was rejected by the British

Chiefs of Staff Committee

The Chiefs of Staff Committee (CSC) is composed of the most senior military personnel in the British Armed Forces who advise on operational military matters and the preparation and conduct of military operations. The committee consists of the C ...

as militarily unfeasible.

Operation Dropshot

"Operation Dropshot" was the 1950s United States contingency plan for a possible

nuclear and conventional war with the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

in the Western European and Asian theaters. Although the scenario made use of nuclear weapons, they were not expected to play a decisive role.

At the time the

US nuclear arsenal was limited in size, based mostly in the United States, and depended on

bombers

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped from an aircra ...

for delivery. "Dropshot" included mission profiles that would have used 300

nuclear bombs

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

and 29,000 high-explosive bombs on 200 targets in 100 cities and towns to wipe out 85% of the Soviet Union's industrial potential in a single stroke. Between 75 and 100 of the 300 nuclear weapons were targeted to destroy Soviet combat aircraft on the ground.

The scenario was devised before the development of

intercontinental ballistic missiles. It was also devised before

U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

and his

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American business executive and the eighth United States Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the ...

changed the US Nuclear War plan from the 'city killing'

countervalue strike plan to a "

counterforce

In nuclear strategy, a counterforce target is one that has a military value, such as a launch silo for intercontinental ballistic missiles, an airbase at which nuclear-armed bombers are stationed, a homeport for ballistic missile submarines, or ...

" plan (targeted more at military forces). Nuclear weapons at this time were not accurate enough to hit a naval base without destroying the city adjacent to it, so the aim of using them was to destroy the enemy's industrial capacity to cripple their war economy.

British-Irish cooperation

Ireland started planning for a possible nuclear war as fears of World War III began to haunt their Cold War foreign policy. Co-operation between Britain and Ireland would be formed in the event of WWIII, where they would share weather data, control aids to navigation, and coordinate the Wartime Broadcasting Service that would occur after a nuclear attack.

Operation Sandstone in Ireland was a top-secret British-Irish military operation.

The armed forces from both states began a new coastal survey of Britain and Ireland cooperating from 1948 to 1955. This was a request from the United States to identify suitable landing grounds for the U.S. in the event of a successful Soviet invasion.

By 1953, the co-operation agreed upon sharing information on wartime weather and the evacuation of civilian refugees from Britain to Ireland.

Ireland's Operation Sandstone ended in 1966.

Exercises Grand Slam, Longstep, and Mainbrace

In January 1950, the

North Atlantic Council

The North Atlantic Council (NAC) is the principal political decision-making body of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), consisting of permanent representatives of its member countries. It was established by Article 9 of the North ...

approved

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

's military strategy of

containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''cordon sanitaire'', which wa ...

. NATO military planning took on a renewed urgency following the outbreak of the

Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

in the early 1950s, prompting NATO to establish a "force under a centralized command, adequate to deter aggression and to ensure the defense of Western Europe".

Allied Command Europe was established under

General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

,

US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

, on 2 April 1951. The

Western Union Defence Organization

From April 1948, the member states of the Western Union (WU), decided to create a military agency under the name of the Western Union Defence Organisation (WUDO). WUDO was formally established on September 27–28, 1948.

Objective

The objective o ...

had previously carried out

Exercise Verity

Exercise Verity was the only major training exercise of the Western Union (WU). Undertaken in July 1949, it involved 60 warships from the British, French, Belgian and Dutch navies. A contemporary newsreel described this exercise as involving "th ...

, a 1949 multilateral exercise involving naval air strikes and submarine attacks.

Exercise Mainbrace brought together 200 ships and over 50,000 personnel to practice the defense of

Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

and

Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

from the Soviet attack in 1952. It was the first major NATO exercise. The exercise was jointly commanded by

Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic Admiral Lynde D. McCormick,

USN

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

, and

Supreme Allied Commander Europe

The Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) is the commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization's (NATO) Allied Command Operations (ACO) and head of ACO's headquarters, Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE). The commander is ...

General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Matthew B. Ridgeway

General Matthew Bunker Ridgway (March 3, 1895 – July 26, 1993) was a senior officer in the United States Army, who served as Supreme Allied Commander Europe (1952–1953) and the 19th Chief of Staff of the United States Army (1953–1955). Alt ...

,

US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

, during the autumn of 1952.

The United States, the United Kingdom,

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, Denmark, Norway,

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

,

Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, and

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

all participated.

Exercises Grand Slam and Longstep were naval exercises held in the

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

during 1952 to practice dislodging an enemy occupying force and amphibious assault. It involved over 170 warships and 700 aircraft under the overall command of Admiral

Robert B. Carney. The overall exercise commander, Admiral Carney summarized the accomplishments of Exercise Grand Slam by stating: "We have demonstrated that the senior commanders of all four powers can successfully take charge of a mixed task force and handle it effectively as a working unit."

The Soviet Union called the exercises "war-like acts" by NATO, with particular reference to the participation of

Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

and Denmark, and prepared for its military maneuvers in the

Soviet Zone.

[''Time'', 29 September 1952]["NATO Ships Enter Baltic Sea" – ''Sydney Morning Herald'', p. 2]

Exercise Strikeback

Exercise Strikeback was a major NATO naval exercise held in 1957, simulating a response to an all-out Soviet attack on NATO. The exercise involved over 200 warships, 650 aircraft, and 75,000 personnel from the

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

, the United Kingdom's

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

, the

Royal Canadian Navy

The Royal Canadian Navy (RCN; french: Marine royale canadienne, ''MRC'') is the naval force of Canada. The RCN is one of three environmental commands within the Canadian Armed Forces. As of 2021, the RCN operates 12 frigates, four attack submar ...

, the

French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

, the

Royal Netherlands Navy, and the

Royal Norwegian Navy

The Royal Norwegian Navy ( no, Sjøforsvaret, , Sea defence) is the branch of the Norwegian Armed Forces responsible for naval operations of Norway. , the Royal Norwegian Navy consists of approximately 3,700 personnel (9,450 in mobilized state, ...

. As the largest peacetime naval operation up to that time, Exercise Strikeback was characterized by military analyst

Hanson W. Baldwin of ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' as "constituting the strongest striking fleet assembled since World WarII".

Exercise Reforger

Exercise Reforger (from the REturn of FORces to GERmany) was an annual exercise conducted during the Cold War by

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

. While troops could easily fly across the Atlantic, the heavy equipment and armor reinforcements would have to come by sea and be delivered to POMCUS (Pre-positioned Overseas Material Configured to Unit Sets) sites.

These exercises tested the United States and allied abilities to carry out transcontinental reinforcement.

Timely reinforcement was a critical part of the NATO reinforcement exercises. The United States needed to be able to send active-duty army divisions to Europe within ten days of receiving the notification.

In addition to assessing the capabilities of the United States, Reforger also monitored the personnel, facilities, and equipment of the European countries playing a significant role in the reinforcement effort.

The exercise was intended to ensure that NATO could quickly deploy forces to West Germany in the event of a conflict with the

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist repub ...

.

The Warsaw Pact outnumbered NATO throughout the Cold War in conventional forces, especially armor. Therefore, in the event of a Soviet invasion, in order not to resort to

tactical nuclear strikes, NATO forces holding the line against a

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist repub ...

armored spearhead would have to be quickly resupplied and replaced. Most of this support would have come across the Atlantic from North America.

Reforger was not merely a show of force—in the event of a conflict, it would be the actual plan to strengthen the NATO presence in Europe. In that instance, it would have been referred to as Operation Reforger. The political goals of Reforger were to promote extended deterrence and foster NATO cohesion.

Important components in Reforger included the

Military Airlift Command

The Military Airlift Command (MAC) is an inactive United States Air Force major command (MAJCOM) that was headquartered at Scott Air Force Base, Illinois. Established on 1 January 1966, MAC was the primary strategic airlift organization of th ...

, the

Military Sealift Command, and the

Civil Reserve Air Fleet

The Civil Reserve Air Fleet is part of the United States's mobility resources. Selected aircraft from U.S. airlines, contractually committed to Civil Reserve Air Fleet, support United States Department of Defense airlift requirements in emergenci ...

.

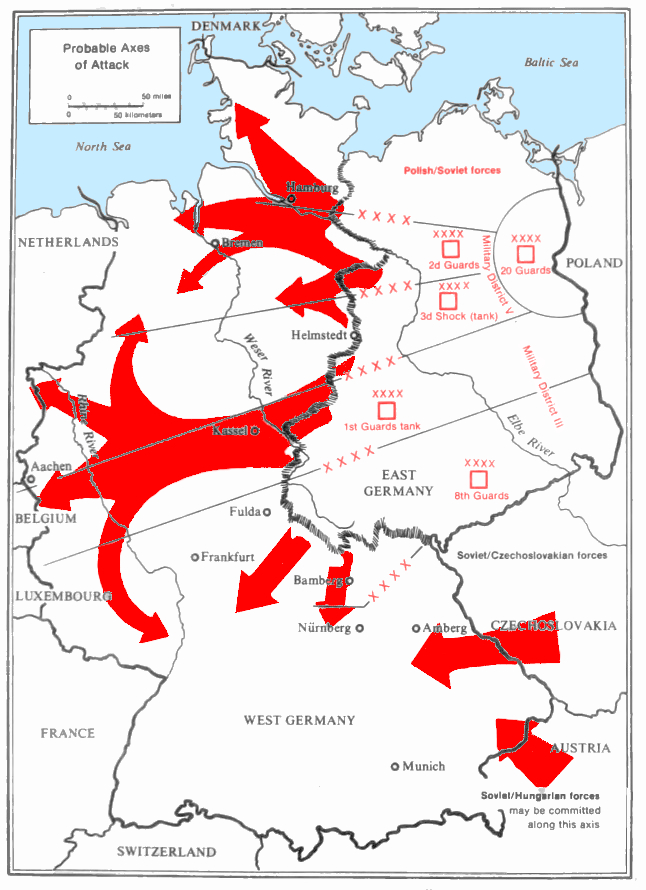

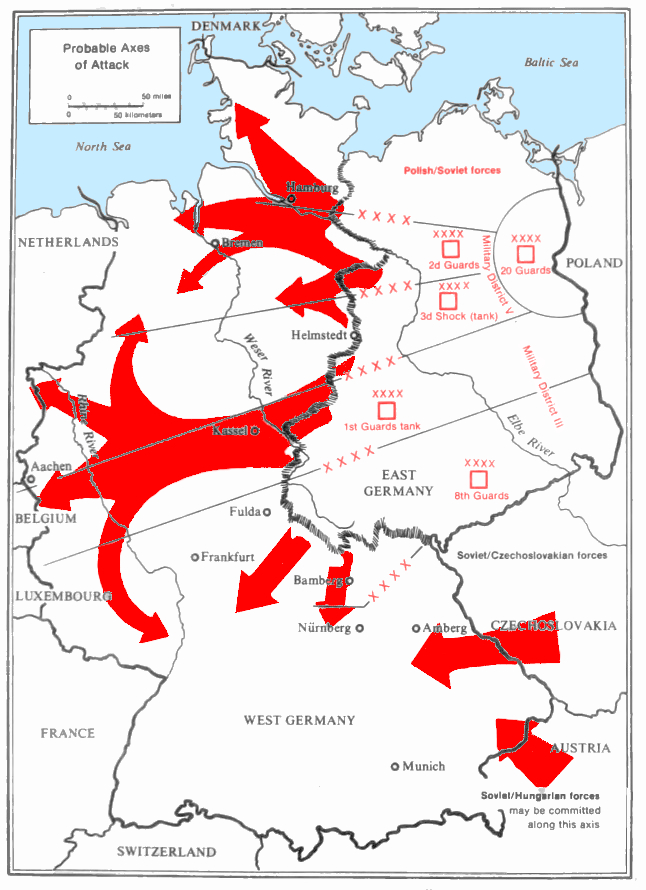

Seven Days to the River Rhine

Seven Days to the River Rhine was a top-secret military simulation exercise developed in 1979 by the Warsaw Pact. It started with the assumption that NATO would launch a nuclear attack on the

Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

river valley in a first-strike scenario, which would result in as many as two million Polish civilian casualties. In response, a Soviet counter-strike would be carried out against

West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

,

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, the

Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and

Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

, with Warsaw Pact forces invading West Germany and aiming to stop at the

River Rhine by the seventh day. Other USSR plans stopped only upon reaching the

French border on day nine. Individual Warsaw Pact states were only assigned their subpart of the strategic picture; in this case, the Polish forces were only expected to go as far as Germany. The Seven Days to the Rhine plan envisioned that Poland and Germany would be largely destroyed by nuclear exchanges and that large numbers of troops would die of

radiation sickness. It was estimated that NATO would fire nuclear weapons behind the advancing Soviet lines to cut off their supply lines and thus blunt their advance. While this plan assumed that NATO would use nuclear weapons to push back any Warsaw Pact invasion, it did not include nuclear strikes on France or the United Kingdom. Newspapers speculated when this plan was declassified, that France and the UK were not to be hit to get them to withhold the use of their nuclear weapons.

Exercise Able Archer

Exercise Able Archer was an annual exercise by the

U.S. European Command that practiced command and control procedures, with emphasis on the transition from solely conventional operations to chemical, nuclear, and conventional operations during a time of war.

"Able Archer 83" was a five-day

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

(NATO)

command post

Command and control (abbr. C2) is a "set of organizational and technical attributes and processes ... hatemploys human, physical, and information resources to solve problems and accomplish missions" to achieve the goals of an organization or e ...

exercise starting on 7 November 1983, that spanned

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

, centered on the

Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe

Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) is the military headquarters of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization's (NATO) Allied Command Operations (ACO) that commands all NATO operations worldwide. ACO's and SHAPE's commander is t ...

(SHAPE) Headquarters in

Casteau Casteau ( wa, Castea) is a village of Wallonia and a district of the municipality of Soignies, located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium.

With the other villages Chaussée-Notre-Dame-Louvignies, Horrues, Naast, Neufvilles, Soignies (town), ...

, north of the city of

Mons. Able Archer's exercises simulated a period of

conflict escalation

Conflict escalation is the process by which conflicts grow in severity or scale over time. That may refer to conflicts between individuals or groups in interpersonal relationships, or it may refer to the escalation of hostilities in a political or ...

, culminating in a coordinated

nuclear attack.

The realistic nature of the 1983 exercise, coupled with

deteriorating relations between the United States and the Soviet Union and the anticipated arrival of

strategic Pershing II

The Pershing II Weapon System was a solid-fueled two-stage medium-range ballistic missile designed and built by Martin Marietta to replace the Pershing 1a Field Artillery Missile System as the United States Army's primary nuclear-capable thea ...

nuclear missiles in Europe, led some members of the

Soviet Politburo

The Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (, abbreviated: ), or Politburo ( rus, Политбюро, p=pəlʲɪtbʲʊˈro) was the highest policy-making authority within the Communist Party of the ...

and military to believe that Able Archer 83 was a

ruse of war

The French , sometimes literally translated as ruse of war, is a non-uniform term; generally what is understood by "ruse of war" can be separated into two groups. The first classifies the phrase purely as an act of military deception against one's ...

, obscuring preparations for a genuine nuclear first strike.

[Beth Fischer, ''Reagan Reversal'', 123, 131.][Pry, ''War Scare'', 37–9.] In response, the Soviets readied their nuclear forces and placed air units in

East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

and

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

on alert.

[''SNIE 11–10–84'' "Implications of Recent Soviet Military-Political Activities" Central Intelligence Agency, 18 May 1984.]

This "1983 war scare" is considered by many historians to be the closest the world has come to nuclear war since the

Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. The threat of nuclear war ended with the conclusion of the exercise on 11 November, however.

[Pry, ''War Scare'', 43–4.]

Strategic Defense Initiative

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was proposed by U.S. President

Ronald Reagan on 23 March 1983.

[ Federation of American Scientists]

Missile Defense Milestones

. Accessed 10 March 2006. In the latter part of his

presidency

A presidency is an administration or the executive, the collective administrative and governmental entity that exists around an office of president of a state or nation. Although often the executive branch of government, and often personified b ...

, numerous factors (which included watching the 1983 movie ''

The Day After

''The Day After'' is an American television film that first aired on November 20, 1983 on the ABC television network. More than 100 million people, in nearly 39 million households, watched the film during its initial broadcast. With ...

'' and hearing through a Soviet defector that

Able Archer 83

Able Archer 83 was the annual NATO Able Archer exercise conducted in November 1983. The purpose for the command post exercise, like previous years, was to simulate a period of conflict escalation, culminating in the US military attaining a simul ...

almost triggered a Russian first strike) had turned Ronald Reagan against the concept of winnable nuclear war, and he began to see nuclear weapons as more of a "

wild card" than a strategic deterrent. Although he later believed in

disarmament treaties slowly blunting the danger of nuclear weaponry by reducing their number and alert status, he also believed a technological solution might allow incoming ICBMs to be shot down, thus making the US invulnerable to a first strike. However, the USSR saw the SDI concept as a major threat, since a unilateral deployment of the system would allow the US to launch a massive first strike on the Soviet Union without any fear of retaliation.

The SDI concept was to use ground-based and space-based systems to protect the United States from attack by strategic

nuclear ballistic missile

A ballistic missile is a type of missile that uses projectile motion to deliver warheads on a target. These weapons are guided only during relatively brief periods—most of the flight is unpowered. Short-range ballistic missiles stay within the ...

s. The initiative focused on strategic defense rather than the prior strategic offense doctrine of

mutually assured destruction

Mutual assured destruction (MAD) is a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy which posits that a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by an attacker on a nuclear-armed defender with second-strike capabilities would cause the ...

(MAD). The Strategic Defense Initiative Organization (SDIO) was set up in 1984 within the

United States Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense (DoD, USDOD or DOD) is an executive branch department of the federal government charged with coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government directly related to national sec ...

to oversee the Strategic Defense Initiative.

NATO nuclear sharing

NATO operational plans for a Third World War have involved NATO allies who do not have their nuclear weapons, using nuclear weapons supplied by the United States as part of a general NATO war plan, under the direction of NATO's

Supreme Allied Commander.

Of the three nuclear powers in NATO (France, the United Kingdom, and the United States) only the United States has provided weapons for nuclear sharing. ,

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

,

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

,

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, the

Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

are still hosting US nuclear weapons as part of NATO's nuclear sharing policy.

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

hosted weapons until 1984,

and

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

until 2001.

The

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

also received US tactical nuclear weapons such as

nuclear artillery

Nuclear artillery is a subset of limited- yield tactical nuclear weapons, in particular those weapons that are launched from the ground at battlefield targets. Nuclear artillery is commonly associated with shells delivered by a cannon, but in ...

and

Lance missiles until 1992, despite the UK being a

nuclear weapons state

Eight sovereign states have publicly announced successful detonation of nuclear weapons. Five are considered to be nuclear-weapon states (NWS) under the terms of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). In order of acquisi ...

in its own right; these were mainly deployed in

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

.

In

peace

Peace is a concept of societal friendship and harmony in the absence of hostility and violence. In a social sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict (such as war) and freedom from fear of violence between individuals or groups. ...

time, the nuclear weapons stored in non-nuclear countries are guarded by

US airmen though previously some artillery and missile systems were guarded by US Army soldiers; the codes required for detonating them are under American control. In case of war, the weapons are to be mounted on the participating countries' warplanes. The weapons are under custody and control of

USAF

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Aerial warfare, air military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part ...

Munitions Support Squadrons co-located on NATO main operating bases that work together with the host nation forces.

, 180 tactical

B61 nuclear bomb

The B61 nuclear bomb is the primary thermonuclear gravity bomb in the United States Enduring Stockpile following the end of the Cold War. It is a low to intermediate-yield strategic and tactical nuclear weapon featuring a two-stage radiation im ...

s of the 480 US nuclear weapons believed to be deployed in Europe fall under the nuclear sharing arrangement. The weapons are stored within a vault in

hardened aircraft shelter

A hardened aircraft shelter (HAS) or protective aircraft shelter (PAS) is a reinforced hangar to house and protect military aircraft from enemy attack. Cost considerations and building practicalities limit their use to fighter size aircraft.

...

s, using the

USAF

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Aerial warfare, air military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part ...

WS3 Weapon Storage and Security System. The delivery warplanes used are

F-16 Fighting Falcons

The General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon is a single-engine multirole fighter aircraft originally developed by General Dynamics for the United States Air Force (USAF). Designed as an air superiority day fighter, it evolved into a successful ...

and

Panavia Tornado

The Panavia Tornado is a family of twin-engine, variable-sweep wing multirole combat aircraft, jointly developed and manufactured by Italy, the United Kingdom and West Germany. There are three primary Tornado variants: the Tornado IDS ( in ...

s.

Historical close calls

With the initiation of the

Cold War arms race in the 1950s, an

apocalyptic war between the United States and the Soviet Union became a real possibility. During the Cold War era (1947–1991), several military events have been described as having come close to potentially triggering World WarIII.

Korean War: 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953

The

Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

was a war between two coalitions fighting for control over the

Korean Peninsula

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

: a communist coalition including

North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

,

China and the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, and a capitalist coalition including

South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and sharing a land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its eas ...

, the United States and the

United Nations Command

United Nations Command (UNC or UN Command) is the multinational military force established to support the Republic of Korea (South Korea) during and after the Korean War. It was the first international unified command in history, and the first a ...

. Many then believed that the conflict was likely to soon escalate into a full-scale war between the three countries, the US, the USSR, and China.

CBS News war correspondent

Bill Downs

William Randall Downs, Jr. (August 17, 1914 – May 3, 1978) was an American broadcast journalist and war correspondent. He worked for CBS News from 1942 to 1962 and for ABC News beginning in 1963. He was one of the original members of the te ...

wrote in 1951, "To my mind, the answer is: Yes, Korea is the beginning of World WarIII. The brilliant

landings at Inchon and the cooperative efforts of the

American armed forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

with the

United Nations Allies have won us a victory in Korea. But this is only the first battle in a major international struggle which now is engulfing the Far East and the entire world." Downs afterwards repeated this belief on ''

ABC Evening News

''ABC World News Tonight'' (titled ''ABC World News Tonight with David Muir'' for its weeknight broadcasts since September 2014) is the flagship daily evening television news program of ABC News, the news division of the American Broadcasting ...

'' while reporting on the

USS ''Pueblo'' incident in 1968. Secretary of State

Dean Acheson later acknowledged that the

Truman administration

Harry S. Truman's tenure as the 33rd president of the United States began on April 12, 1945, upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and ended on January 20, 1953. He had been vice president for only days. A Democrat from Missouri, he ran ...

was concerned about the escalation of the conflict and that General

Douglas MacArthur warned him that a U.S.-led intervention risked a Soviet response.

Berlin Crisis: 4 June – 9 November 1961

The

Berlin Crisis of 1961 was a political-military confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union at

Checkpoint Charlie

Checkpoint Charlie (or "Checkpoint C") was the best-known Berlin Wall crossing point between East Berlin and West Berlin during the Cold War (1947–1991), as named by the Western Allies.

East German leader Walter Ulbricht agitated and maneu ...

with both several American and Soviet/East German tanks and troops at the stand-off at each other only 100 yards on either side of the checkpoint. The reason behind the confrontation was about the occupational status of the German capital city,

Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

, and of

post–World War II Germany. The Berlin Crisis started when the USSR launched an ultimatum demanding the withdrawal of all armed forces from Berlin, including the Western armed forces in

West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

. The crisis culminated in the city's de facto partition with the

East German

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

erection of the

Berlin Wall. This stand-off ended peacefully on 28 October following a US–Soviet understanding to withdraw tanks and reduce tensions.

Cuban Missile Crisis: 15–29 October 1962

The

Cuban Missile Crisis, a confrontation on the stationing of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba in response to the failed

Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fin ...

, is considered as having been the closest to a nuclear exchange, which could have precipitated a third World War. The crisis peaked on 27 October, with three separate major incidents occurring on the same day:

* The most critical incident occurred when a Soviet submarine nearly launched a

nuclear-tipped torpedo in response to having been targeted by American naval

depth charges in international waters, with the Soviet nuclear launch response only having been prevented by

Soviet Navy executive officer Vasily Arkhipov

Vasily Aleksandrovich Arkhipov ( rus, Василий Александрович Архипов, p=vɐˈsʲilʲɪj ɐlʲɪkˈsandrəvʲɪtɕ arˈxʲipəf, 30 January 1926 – 19 August 1998) was a Soviet Naval officer credited with preventing a ...

.

* The shooting down of a

Lockheed U-2

The Lockheed U-2, nicknamed "''Dragon Lady''", is an American single-jet engine, high altitude reconnaissance aircraft operated by the United States Air Force (USAF) and previously flown by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). It provides day ...

spy plane piloted by

Rudolf Anderson

Rudolf Anderson Jr. (September 15, 1927 – October 27, 1962) was an American and United States Air Force major and pilot. He was the first recipient of the Air Force Cross, the U.S. military's and Air Force's second-highest award and decoratio ...

while violating Cuban airspace.

* The near interception of another U-2 that had somehow managed to stray into Soviet airspace over

Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

, which airspace violation nearly caused the Soviets to believe that this might be the vanguard of a US aerial bombardment.

Despite what many believe to be the closest the world has come to a nuclear conflict, throughout the entire standoff, the

Doomsday Clock

The Doomsday Clock is a symbol that represents the likelihood of a man-made global catastrophe, in the opinion of the members of the ''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists''. Maintained since 1947, the clock is a metaphor for threats to humanity ...

, which is run by the ''

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

The ''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'' is a nonprofit organization concerning science and global security issues resulting from accelerating technological advances that have negative consequences for humanity. The ''Bulletin'' publishes conte ...

'' to estimate how close the end of the world, or doomsday, is, with midnight being the apocalypse, stayed at a relatively stable seven minutes to midnight. This has been explained as being due to the brevity of the crisis since the clock monitored more long-term factors such as the leadership of countries, conflicts, wars, and political upheavals, as well as societies' reactions to said factors.

The ''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'' now credits the political developments resulting from the Cuban Missile Crisis with having enhanced global stability. The ''Bulletin'' posits that future crises and occasions that might otherwise escalate, were rendered more stable due to two major factors:

# A

Washington to Moscow direct telephone line, resulted from the communication trouble between the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

and the

Kremlin during the crisis, giving the leaders of the two largest nuclear powers the ability to contact each other in real-time, rather than sending written messages that needed to be translated and wired, which had dragged out conversations in which seconds could have potentially prevented a nuclear exchange.

# The second factor was caused in part due to the worldwide reaction to how close the US and USSR had come to the brink of World WarIII during the standoff. As the public began to more closely monitor topics involving nuclear weapons, and therefore to rally support for the cause of non-proliferation, the

1963 test ban treaty was signed. To date this treaty has been signed by 126 total nations, with the most notable exceptions being

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and

China. Both of these countries were still in the relative beginning stages of their nuclear programs at the time of the original treaty signing, and both sought nuclear capabilities independent of their allies.

This Test Ban Treaty prevented the testing of nuclear ordnance that detonated in the

atmosphere, limiting

nuclear weapons testing

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

to below ground and underwater, decreasing

fallout

Nuclear fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and the shock wave has passed. It commonly refers to the radioac ...

and effects on the environment, and subsequently caused the Doomsday Clock to decrease by five minutes, to arrive at a total of twelve minutes to midnight. Up until this point, over 1000 nuclear bombs had been detonated, and concerns over both long and short term effects to the planet became increasingly more worrisome to scientists.

Sino-Soviet border conflicts: 2 March – 11 September 1969

The

Sino-Soviet border conflict

The Sino-Soviet border conflict was a seven-month undeclared military conflict between the Soviet Union and China in 1969, following the Sino-Soviet split. The most serious border clash, which brought the world's two largest communist states t ...

was a seven-month undeclared military border war between the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and

China at the height of the

Sino-Soviet split

The Sino-Soviet split was the breaking of political relations between the China, People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union caused by Doctrine, doctrinal divergences that arose from their different interpretations and practical applications ...

in 1969. The most serious of these border clashes, which brought the world's two largest

communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Comi ...

s to the brink of war, occurred in March 1969 in the vicinity of

Zhenbao (Damansky) Island on the

Ussuri (Wusuli) River, near

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

.

The conflict resulted in a ceasefire, with a return to the status quo. Critics point out that the Chinese attack on Zhenbao was to deter any potential future Soviet invasions; that by killing some Soviets, China demonstrated that it could not be 'bullied'; and that Mao wanted to teach them 'a bitter lesson'.

China's relations with the USSR remained sour after the conflict, despite the border talks, which began in 1969 and continued inconclusively for a decade. Domestically, the threat of war caused by the border clashes inaugurated a new stage in the

Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated goa ...

; that of China's thorough militarization. The

9th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party

9 (nine) is the natural number following and preceding .

Evolution of the Arabic digit

In the beginning, various Indians wrote a digit 9 similar in shape to the modern closing question mark without the bottom dot. The Kshatrapa, Andhra a ...

, held in the aftermath of the

Zhenbao Island incident, confirmed Defense Minister

Lin Biao

)

, serviceyears = 1925–1971

, branch = People's Liberation Army

, rank = Marshal of the People's Republic of China Lieutenant general of the National Revolutionary Army, Republic of China

, commands ...

as

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

's heir apparent.

Following the events of 1969, the Soviet Union further increased its

forces along the

Sino-Soviet border, and in the

Mongolian People's Republic

The Mongolian People's Republic ( mn, Бүгд Найрамдах Монгол Ард Улс, БНМАУ; , ''BNMAU''; ) was a socialist state which existed from 1924 to 1992, located in the historical region of Outer Mongolia in East Asia. It w ...

.

Yom Kippur War superpower tensions: 6–25 October 1973

The

Yom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, was an armed conflict fought from October 6 to 25, 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab states led by E ...

, also known as the Ramadan War, or October War, began with Arab victories. Israel successfully counterattacked. Tensions grew between the US (which supported Israel) and the Soviet Union (which sided with the Arab states). American and Soviet naval forces came close to firing upon each other in

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

. Admiral

Daniel J. Murphy of the

US Sixth Fleet

The Sixth Fleet is a numbered fleet of the United States Navy operating as part of United States Naval Forces Europe. The Sixth Fleet is headquartered at Naval Support Activity Naples, Italy. The officially stated mission of the Sixth Fleet in ...

reckoned the chances of the Soviet squadron attempting a first strike against his fleet at 40 percent. The Pentagon moved Defcon status from 4to3. The superpowers had been pushed to the brink of war, but tensions eased with the ceasefire brought in under

UNSC 339.

NORAD computer error of 1979: 9 November 1979

The United States made emergency retaliation preparations after

NORAD saw on-screen indications that a full-scale Soviet attack had been launched. No attempt was made to use the "

red telephone" hotline to clarify the situation with the USSR and it was not until early-warning radar systems confirmed no such launch had taken place that NORAD realized that a computer system test had caused the display errors. A senator inside the NORAD facility at the time described an atmosphere of absolute panic. A GAO investigation led to the construction of an off-site test facility to prevent similar mistakes.

Soviet radar malfunction: 26 September 1983

A

false alarm

A false alarm, also called a nuisance alarm, is the deceptive or erroneous report of an emergency, causing unnecessary panic and/or bringing resources (such as emergency services) to a place where they are not needed. False alarms may occur with ...

occurred on the

Soviet nuclear early warning system, showing the launch of American

LGM-30 Minuteman

The LGM-30 Minuteman is an American land-based intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) in service with the Air Force Global Strike Command. , the LGM-30G Minuteman III version is the only land-based ICBM in service in the United States and ...

intercontinental ballistic missiles from bases in the United States. A retaliatory attack was prevented by

Stanislav Petrov

Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov (russian: Станисла́в Евгра́фович Петро́в; 7 September 1939 – 19 May 2017) was a lieutenant colonel of the Soviet Air Defence Forces who played a key role in the 1983 Soviet nuclear fa ...

, a

Soviet Air Defence Forces

The Soviet Air Defence Forces (russian: войска ПВО, ''voyska protivovozdushnoy oborony'', ''voyska PVO'', ''V-PVO'', lit. ''Anti-Air Defence Troops''; and formerly ''protivovozdushnaya oborona strany'', ''PVO strany'', lit. ''Anti-Air De ...

officer, who realised the system had simply malfunctioned (which was borne out by later investigations).

Able Archer escalations: 2–11 November 1983

During

Able Archer 83

Able Archer 83 was the annual NATO Able Archer exercise conducted in November 1983. The purpose for the command post exercise, like previous years, was to simulate a period of conflict escalation, culminating in the US military attaining a simul ...

, a ten-day

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

exercise simulating a period of

conflict escalation

Conflict escalation is the process by which conflicts grow in severity or scale over time. That may refer to conflicts between individuals or groups in interpersonal relationships, or it may refer to the escalation of hostilities in a political or ...

that culminated in a

DEFCON 1

The defense readiness condition (DEFCON) is an alert state used by the United States Armed Forces. (DEFCON is not mentioned in the 2010 and newer document)

The DEFCON system was developed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) and unified and spec ...

nuclear strike, some members of the

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

Politburo and

armed forces treated the events as a

ruse of war

The French , sometimes literally translated as ruse of war, is a non-uniform term; generally what is understood by "ruse of war" can be separated into two groups. The first classifies the phrase purely as an act of military deception against one's ...

concealing a genuine first strike. In response, the military prepared for a coordinated counter-attack by readying nuclear forces and placing air units stationed in the

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist repub ...

states of

East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

and

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

under high alert. However, the state of Soviet preparation for retaliation ceased upon completion of the Able Archer exercises.

Norwegian rocket incident: 25 January 1995

The

Norwegian rocket incident

The Norwegian rocket incident, also known as the Black Brant scare, occurred on January 25, 1995 when a team of Norwegian and American scientists launched a Black Brant XII four-stage sounding rocket from the Andøya Rocket Range off the northwe ...

was the first World WarIII close call to occur outside the Cold War. This incident occurred when Russia's

Olenegorsk early warning station accidentally mistook the radar signature from a

Black Brant XII research rocket (being jointly launched by Norwegian and US scientists from

Andøya Rocket Range

Andøya is the northernmost island in the Vesterålen archipelago, situated about inside the Arctic circle. Andøya is located in Andøy Municipality in Nordland county, Norway. The main population centres on the island include the villages of ...

), as appearing to be the radar signature of the launch of a

Trident

A trident is a three- pronged spear. It is used for spear fishing and historically as a polearm.

The trident is the weapon of Poseidon, or Neptune, the God of the Sea in classical mythology. The trident may occasionally be held by other mari ...

SLBM

A submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) is a ballistic missile capable of being launched from submarines. Modern variants usually deliver multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), each of which carries a nuclear warhe ...

missile. In response,

Russian President

The president of the Russian Federation ( rus, Президент Российской Федерации, Prezident Rossiyskoy Federatsii) is the head of state of the Russian Federation. The president leads the executive branch of the federal ...

Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

was summoned and the ''

Cheget

''Cheget'' (russian: Чегет) is a "nuclear briefcase" (named after in Kabardino-Balkaria) and a part of the automatic system for the command and control of Russia's Strategic Nuclear Forces (SNF) named ''Kazbek'' (, named after Mount Kazbe ...

''

nuclear briefcase

A nuclear briefcase is a specially outfitted briefcase used to authorize the use of nuclear weapons and is usually kept near the leader of a nuclear weapons state at all times.

France

In France, the nuclear briefcase does not officially exist. A ...

was activated for the first and only time. However, the high command was soon able to determine that the rocket was not entering Russian airspace, and promptly aborted plans for combat readiness and retaliation. It was retrospectively determined that, while the rocket scientists had informed thirty states including Russia about the test launch, the information had not reached Russian radar technicians.

Incident at Pristina airport: 12 June 1999

On 12 June 1999, the day following the end of the

Kosovo War

The Kosovo War was an armed conflict in Kosovo that started 28 February 1998 and lasted until 11 June 1999. It was fought by the forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (i.e. Serbia and Montenegro), which controlled Kosovo before the wa ...

, some 250 Russian peacekeepers occupied the

Pristina International Airport ahead of the arrival of

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

troops and were to secure the arrival of reinforcements by air. American NATO Supreme Allied Commander Europe General

Wesley Clark

Wesley Kanne Clark (born December 23, 1944) is a retired United States Army officer. He graduated as valedictorian of the class of 1966 at West Point and was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship to the University of Oxford, where he obtained a degree ...

ordered the use of force against the Russians.

, a

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

general who contacted the Russians during the incident, refused to enforce Clark's orders, famously telling him "I'm not going to start the Third World War for you".

Captain

James Blunt

James Blunt (born James Hillier Blount; 22 February 1974) is an English singer, songwriter and musician. A former reconnaissance officer in the Life Guards regiment of the British Army, he served under NATO during the 1999 Kosovo War. After l ...

, the lead officer at the front of the NATO column in the direct armed stand-off against the Russians, received the "Destroy!" orders from Clark over the radio, but he followed Jackson's orders to encircle the airfield instead and later said in an interview that even without Jackson's intervention he would have refused to follow Clark's order.

Current conflicts

Russian invasion of Ukraine: 24 February 2022–present

On 24 February 2022, Russia's president

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin; (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who holds the office of president of Russia. Putin has served continuously as president or prime minister since 1999: as prime min ...

ordered a full-scale invasion of

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

, marking a major escalation of the

Russo-Ukrainian War

The Russo-Ukrainian War; uk, російсько-українська війна, rosiisko-ukrainska viina. has been ongoing between Russia (alongside Russian separatists in Ukraine) and Ukraine since February 2014. Following Ukraine's Rev ...

, which began in 2014. The invasion has been described as the largest military conflict in Europe since World War II. The invasion received widespread

international condemnation, including new

sanctions imposed on Russia, which notably included Russia's ban from

SWIFT

Swift or SWIFT most commonly refers to:

* SWIFT, an international organization facilitating transactions between banks

** SWIFT code

* Swift (programming language)

* Swift (bird), a family of birds

It may also refer to:

Organizations

* SWIFT, ...

and the closing of most Western airspace to Russian planes. Moreover, both prior to and during the invasion, some of the 30

member states of NATO have been providing Ukraine with arms and other

materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the specif ...

support. Throughout the invasion, several senior Russian politicians, including president Putin and foreign minister

Sergei Lavrov, have made a number of statements widely seen as threatening the use of nuclear weapons, while several officials from the United States and NATO, including US president

Joe Biden and NATO secretary general

Jens Stoltenberg

Jens Stoltenberg (born 16 March 1959) is a Norwegian politician who has been serving as the 13th secretary general of NATO since 2014. A member of the Norwegian Labour Party, he previously served as the 34th prime minister of Norway from 2000 to ...

, have made statements reaffirming NATO's response in the event that Russia attacks any NATO member state or uses nuclear weapons, while also reiterating the need to prevent the crisis from escalating into a potential third World War. On 15 November,

a missile struck the Polish village of

Przewodów near the border with Ukraine, killing two people.

It was the first incident of a missile landing and exploding within NATO territory during the invasion. Despite initial statements regarding a close call to a conflict between Russia and NATO, the United States found that the missile was likely to have been an air defense missile fired by Ukrainian forces at an incoming Russian missile.

Various experts, analysts, and others have described the crisis as a close call to a third World War, while others have suggested the contrary.

Extended usage of the term

Cold War

As Soviet-American relations grew tenser in the post-World WarII period, the fear that it could escalate into World WarIII was ever-present. A

Gallup poll

Gallup, Inc. is an American analytics and advisory company based in Washington, D.C. Founded by George Gallup in 1935, the company became known for its public opinion polls conducted worldwide. Starting in the 1980s, Gallup transitioned its ...

in December 1950 found that more than half of Americans considered World WarIII to have already started.

In 2004, commentator

Norman Podhoretz

Norman Podhoretz (; born January 16, 1930) is an American magazine editor, writer, and conservative political commentator, who identifies his views as " paleo-neoconservative". proposed that the

Cold War, lasting from the surrender of the

Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

until the

fall of the Berlin Wall

The fall of the Berlin Wall (german: Mauerfall) on 9 November 1989, during the Peaceful Revolution, was a pivotal event in world history which marked the destruction of the Berlin Wall and the figurative Iron Curtain and one of the series of eve ...

, might rightly be called World WarIII. By Podhoretz's reckoning, "World WarIV" would be the global campaign against

Islamofascism

"Islamofascism", first described as "Islamic fascism" in 1933, is a term popularized in the 1990s drawing an analogical comparison between the ideological characteristics of specific Islamist or Islamic fundamentalist movements and short-lived E ...

.

Still, the majority of historians would seem to hold that World WarIII would necessarily have to be a worldwide "war in which large forces from many countries fought" and a war that "involves most of the principal nations of the world". The Cold War received its name from the lack of action taken from both sides. The lack of action was out of fear that a nuclear war would possibly destroy humanity. In his book ''Secret Weapons of the Cold War'', Bill Yenne explains that the military standoff that occurred between the two 'Superpowers', namely the United States and the Soviet Union, from the 1940s through to 1991, was only the Cold War, which ultimately helped to enable mankind to avert the possibility of an all-out nuclear confrontation, and that it certainly was not World WarIII.

War on terror

The "

war on terror