White Terror (Spain) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the

After the flight of King

After the flight of King

The White Terror commenced on 17 July 1936, the day of the Nationalist ''coup d'état'', with hundreds of assassinations effected in the area controlled by the right-wing rebels, but it had been planned before earlier. In the 30 June 1936 secret instructions for the ''coup d'état'' in Morocco, Mola ordered the rebels "to eliminate left-wing elements, communists, anarchists, union members, etc." The White Terror included the repression of political opponents in areas occupied by the Nationalist, mass executions in areas captured from the Republicans, such as the Massacre of Badajoz, and looting.

In ''The Spanish Labyrinth'' (1943),

The White Terror commenced on 17 July 1936, the day of the Nationalist ''coup d'état'', with hundreds of assassinations effected in the area controlled by the right-wing rebels, but it had been planned before earlier. In the 30 June 1936 secret instructions for the ''coup d'état'' in Morocco, Mola ordered the rebels "to eliminate left-wing elements, communists, anarchists, union members, etc." The White Terror included the repression of political opponents in areas occupied by the Nationalist, mass executions in areas captured from the Republicans, such as the Massacre of Badajoz, and looting.

In ''The Spanish Labyrinth'' (1943),

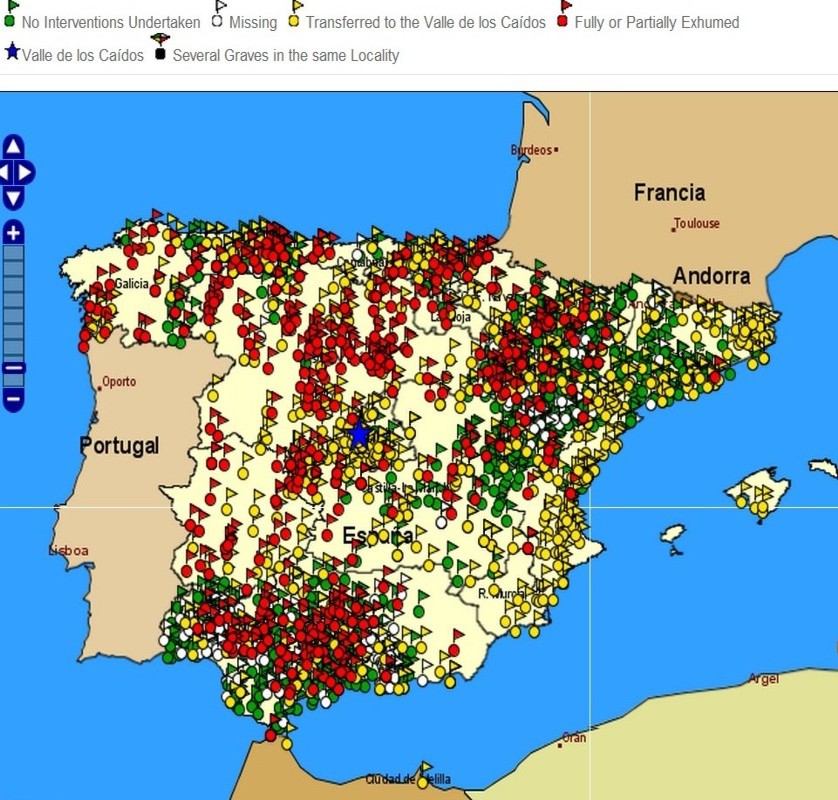

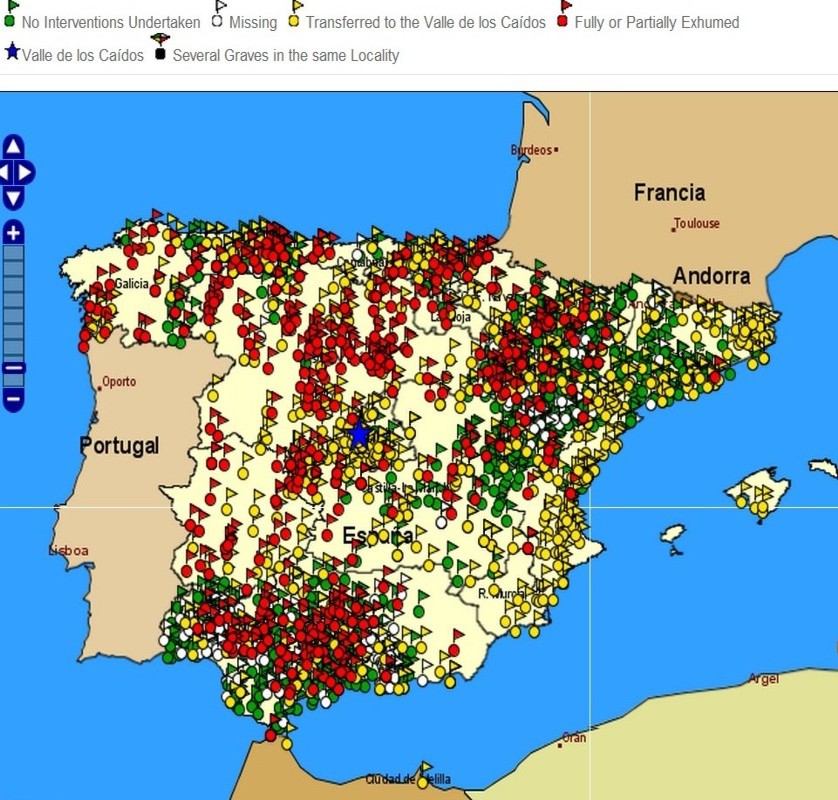

Estimates of executions behind the Nationalist lines during the Spanish Civil War range from fewer than 50,000 to 200,000 (Hugh Thomas: 75,000, Secundino Serrano: 90,000; Josep Fontana: 150,000; and Julián Casanova: 100,000.Casanova, Julián. ''The Spanish Republic and Civil War''. Cambridge University Press. 2010. New York. p. 181. Most of the victims were killed without a trial in the first months of the war and their corpses were left on the sides of roads or in clandestine and unmarked mass graves. For example, in Valladolid only 374 officially recorded victims of the repression of a total of 1,303 (there were many other unrecorded victims) were executed after a trial, and the historian Stanley Payne in his work ''Fascism in Spain'' (1999), citing a study by Cifuentes Checa and Maluenda Pons carried out over the Nationalist-controlled city of Zaragoza and its environs, refers to 3,117 killings, of which 2,578 took place in 1936. He goes on to state that by 1938 the military courts there were directing summary executions.

Many of the executions in the course of the war were carried by militants of the fascist party ''Falange'' ('' Falange Española de las J.O.N.S.'') or militants of the

Estimates of executions behind the Nationalist lines during the Spanish Civil War range from fewer than 50,000 to 200,000 (Hugh Thomas: 75,000, Secundino Serrano: 90,000; Josep Fontana: 150,000; and Julián Casanova: 100,000.Casanova, Julián. ''The Spanish Republic and Civil War''. Cambridge University Press. 2010. New York. p. 181. Most of the victims were killed without a trial in the first months of the war and their corpses were left on the sides of roads or in clandestine and unmarked mass graves. For example, in Valladolid only 374 officially recorded victims of the repression of a total of 1,303 (there were many other unrecorded victims) were executed after a trial, and the historian Stanley Payne in his work ''Fascism in Spain'' (1999), citing a study by Cifuentes Checa and Maluenda Pons carried out over the Nationalist-controlled city of Zaragoza and its environs, refers to 3,117 killings, of which 2,578 took place in 1936. He goes on to state that by 1938 the military courts there were directing summary executions.

Many of the executions in the course of the war were carried by militants of the fascist party ''Falange'' ('' Falange Española de las J.O.N.S.'') or militants of the

Catalonia suffered the most fierce engagements during the civil war, as seen in several examples. In

Catalonia suffered the most fierce engagements during the civil war, as seen in several examples. In  The 2nd president of the Generalitat de Catalunya, Lluís Companys, went into exile in

The 2nd president of the Generalitat de Catalunya, Lluís Companys, went into exile in

'' El Mundo'', 7 July 2002 Julián Casanova Ruiz, nominated in 2008 among the experts in the first judicial investigation (conducted by judge

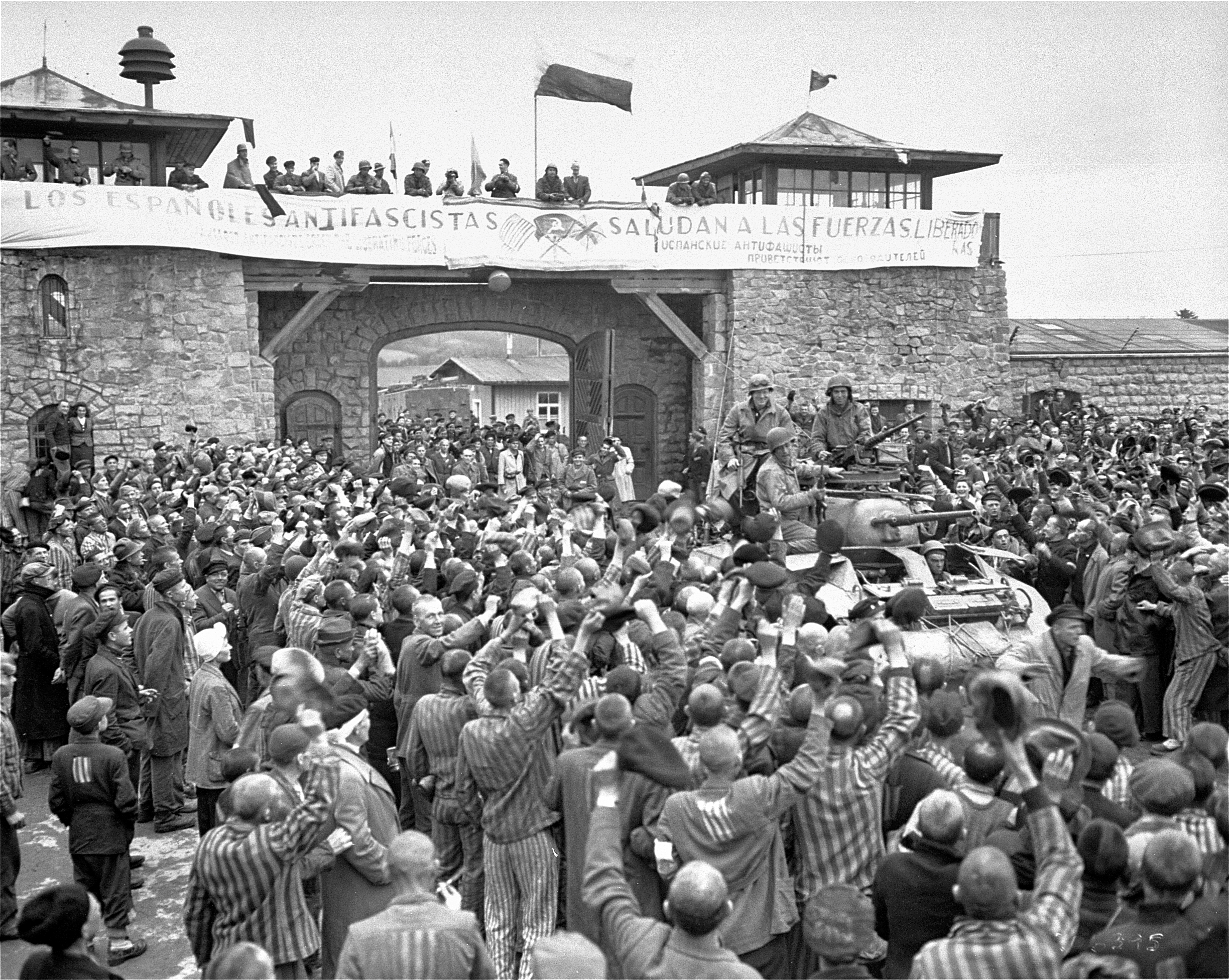

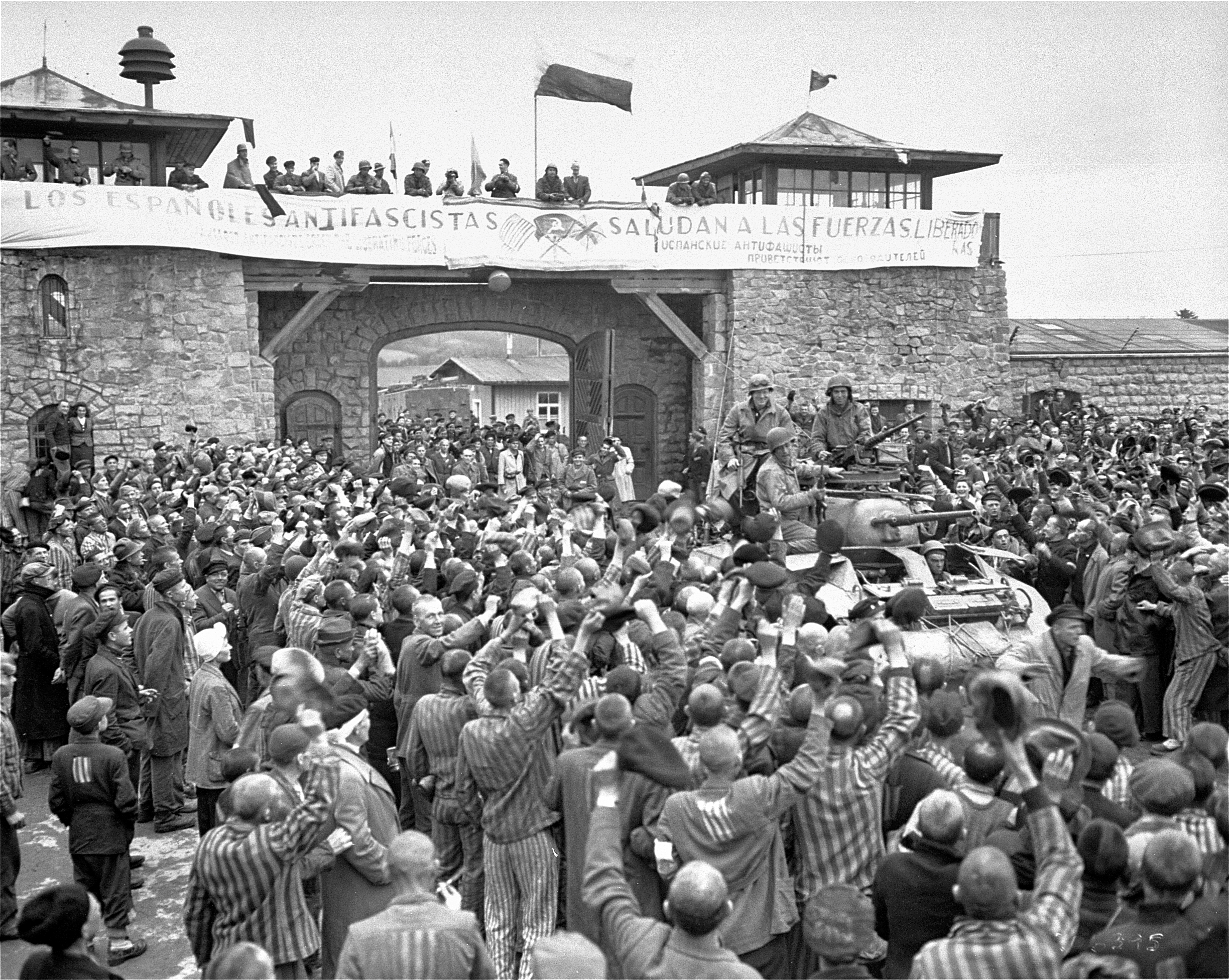

When Nazi Germany occupied

When Nazi Germany occupied

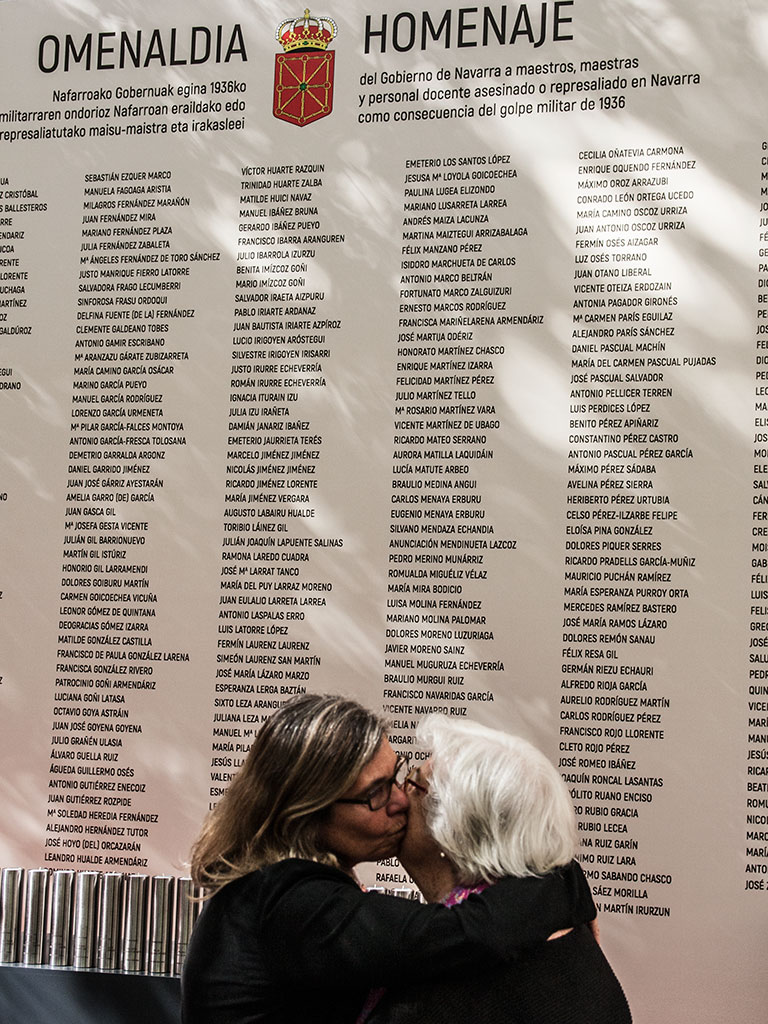

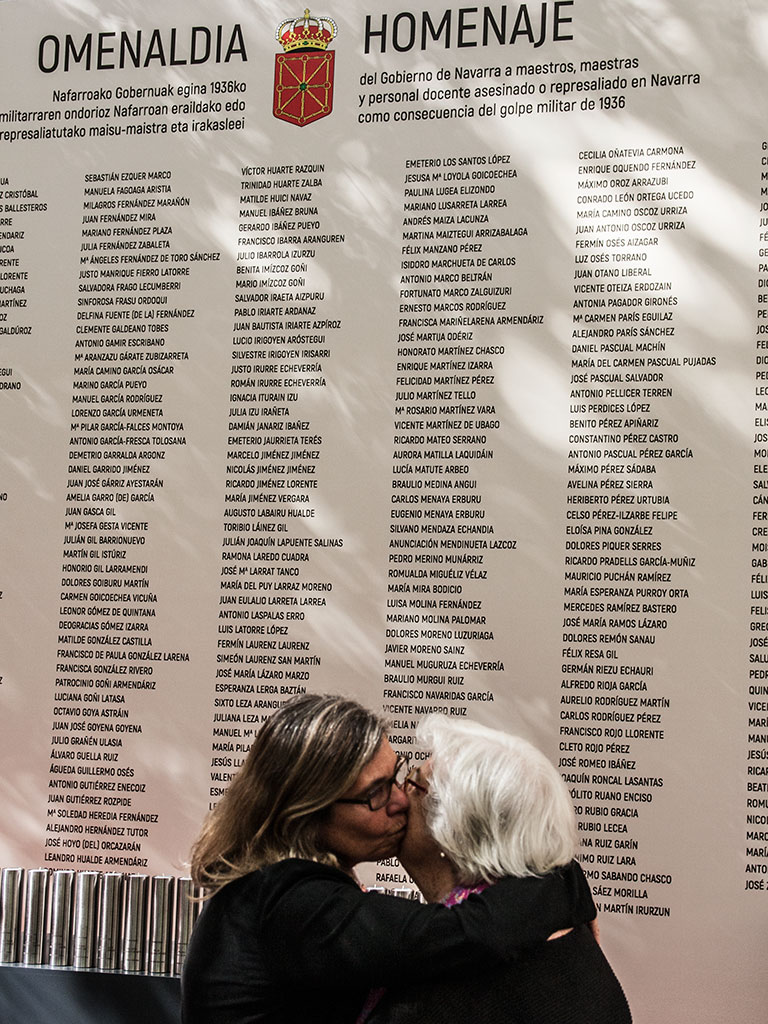

The Francoist State carried out extensive purges among the civil service. Thousands of officials loyal to the Republic were expelled from the army. Thousands of university and school teachers lost their jobs (a quarter of all Spanish teachers). Priority for employment was always given to Nationalist supporters, and it was necessary to have a "good behavior" certificate from local Falangist officials and parish priests. Furthermore, the Francoist State encouraged tens of thousands of Spaniards to denounce their Republican neighbours and friends:

The Francoist State carried out extensive purges among the civil service. Thousands of officials loyal to the Republic were expelled from the army. Thousands of university and school teachers lost their jobs (a quarter of all Spanish teachers). Priority for employment was always given to Nationalist supporters, and it was necessary to have a "good behavior" certificate from local Falangist officials and parish priests. Furthermore, the Francoist State encouraged tens of thousands of Spaniards to denounce their Republican neighbours and friends:

''Time''"Spain Faces Up to Franco's Guilt"

''Newsweek''"War Bones"

''Franco's Crimes''

Amnesty International-Spain, ''The Long History of Truth''

''Civil War in Galicia''

The Limits of Quantification: Francoist Repression

* ttp://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article5802820.ece ''Times Online''The lost childrens of the francoism

Slave Labourers and Slave Labour Camps Spanish Republicans in the Channel Islands

Singling Out Victims: Denunciation and Collusion in the Post-Civil War Francoist Repression in Spain, 1939–1945

Franco's Carnival of death. Paul Preston.

{{Spanish Civil War Human rights abuses in Spain Political repression in Spain Politicides Spanish Civil War Far-right terrorism in Spain Political and cultural purges War crimes of the Spanish Civil War Anti-communist terrorism Christian terrorism in Europe Religious persecution Persecution of LGBT people Persecution of intellectuals

history of Spain

The history of Spain dates to contact the pre-Roman peoples of the Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula made with the Greeks and Phoenicians and the first writing systems known as Paleohispanic scripts were developed. During Classical A ...

, the White Terror ( es, Terror Blanco; also known as the Francoist Repression, ''la Represión franquista'') describes the political repression

Political repression is the act of a state entity controlling a citizenry by force for political reasons, particularly for the purpose of restricting or preventing the citizenry's ability to take part in the political life of a society, thereb ...

, including executions

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

and rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ag ...

s, which were carried out by the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

(1936–1939), as well as during the first nine years of the regime

In politics, a regime (also "régime") is the form of government or the set of rules, cultural or social norms, etc. that regulate the operation of a government or institution and its interactions with society. According to Yale professor Juan Jo ...

of General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

. In the 1936–1975 period, Francoist Spain

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spai ...

had many official enemies: Loyalists to the Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII, and was di ...

(1931–1939), Liberals, socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

of different stripes, Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

, intellectuals

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or as ...

, homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

s, Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

s, Romanis

The Romani (also spelled Romany or Rromani , ), colloquially known as the Roma, are an Indo-Aryan peoples, Indo-Aryan ethnic group, traditionally nomadic Itinerant groups in Europe, itinerants. They live in Europe and Anatolia, and have Ro ...

, Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, and Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

, Catalan

Catalan may refer to:

Catalonia

From, or related to Catalonia:

* Catalan language, a Romance language

* Catalans, an ethnic group formed by the people from, or with origins in, Northern or southern Catalonia

Places

* 13178 Catalan, asteroid #1 ...

, Andalusian and Galician nationalists.

The Francoist Repression was motivated by the right-wing notion of a '' limpieza social'', a cleansing of society. This meant that the killing of people viewed as enemies of the state

An enemy of the state is a person accused of certain crimes against the state such as treason, among other things. Describing individuals in this way is sometimes a manifestation of political repression. For example, a government may purport to m ...

began immediately upon the Nationalists' capture of a place. Ideologically, the Roman Catholic Church legitimized

Legitimation or legitimisation is the act of providing legitimacy. Legitimation in the social sciences refers to the process whereby an act, process, or ideology becomes legitimate by its attachment to norms and values within a given society. It ...

the killing by the Civil Guard (national police) and the ''Falange

The Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS; ), frequently shortened to just "FET", was the sole legal party of the Francoist regime in Spain. It was created by General Francisco F ...

'' as the defense of Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

.

Hardwired into the Francoist regime, repression turned "the whole country into one wide prison", according to Ramón Arnabat, enabled by the trap of turning the tables against the loyalist defenders of the Republic by means of accusing them of "adherence to the rebellion", "aid to the rebellion" or "military rebellion". Throughout Franco's rule (1 October 193620 November 1975), the Law of Political Responsibilities ''(Ley de Responsabilidades Políticas)'', promulgated in 1939, reformed in 1942, and in force until 1966, gave legalistic color of law

Color (American English) or colour (British English) is the visual perceptual property deriving from the spectrum of light interacting with the photoreceptor cells of the eyes. Color categories and physical specifications of color are associ ...

to the political repression that characterized the dismantling of the Second Republic; and served to punish Loyalist Spaniards.

Historians such as Stanley Payne

Stanley George Payne (born September 9, 1934) is an American historian of modern Spain and European Fascism at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He retired from full-time teaching in 2004 and is currently Professor Emeritus at its Department ...

consider the White Terror's death toll to be greater than the death toll of the corresponding Red Terror

The Red Terror (russian: Красный террор, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in lat ...

.

Background

After the flight of King

After the flight of King Alfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII (17 May 1886 – 28 February 1941), also known as El Africano or the African, was King of Spain from 17 May 1886 to 14 April 1931, when the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed. He was a monarch from birth as his father, Alf ...

(r. 1886–1931), the Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII, and was di ...

was established on 14 April 1931, led by President Niceto Alcalá-Zamora

Niceto Alcalá-Zamora y Torres (6 July 1877 – 18 February 1949) was a Spanish lawyer and politician who served, briefly, as the first prime minister of the Second Spanish Republic, and then—from 1931 to 1936—as its president.

Early life

...

, whose government instituted a program of secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

reforms, which included agrarian reform Agrarian reform can refer either, narrowly, to government-initiated or government-backed redistribution of agricultural land (see land reform) or, broadly, to an overall redirection of the agrarian system of the country, which often includes land re ...

, the separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

, the right to divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the ...

, women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

(November 1933), the socio-political reformation of the Spanish Army

The Spanish Army ( es, Ejército de Tierra, lit=Land Army) is the terrestrial army of the Spanish Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is one of the oldest active armies — dating back to the late 15th century.

The ...

, and political autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from αὐτο- ''auto-'' "self" and νόμος ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one's ...

for Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

and the Basque Country (October 1936).President Alcalá-Zamora's reforms to Spanish society were continually blocked by the right-wing parties and rejected by the far-left-wing National Confederation of Labour (CNT, ''Confederación Nacional del Trabajo

The Confederación Nacional del Trabajo ( en, National Confederation of Labor; CNT) is a Spanish confederation of anarcho-syndicalist labor unions, which was long affiliated with the International Workers' Association (AIT). When working wi ...

''). The Second Spanish Republic suffered attacks from the right wing (the failed ''coup d'état'' of Sanjurjo in 1932), and the left wing (the Asturian miners' strike of 1934

The Asturian miners' strike of 1934 was a major strike action undertaken by regional miners against the 1933 Spanish general election, which redistributed political power from the leftists to conservatives in the Second Spanish Republic. The str ...

), whilst enduring the economic impact of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

.

After the general election in February 1936 was won by the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

a coalition of leftist parties (Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español ; PSOE ) is a social-democraticThe PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* political party in Spain. The PSOE has been in gov ...

(PSOE), Republican Left (IR), Republican Union (UR), Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A ...

(PCE), Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), Republican Left of Catalonia

The Republican Left of Catalonia ( ca, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya, ERC; ; generically branded as ) is a Catalan independence movement, pro-Catalan independence, social democracy, social-democratic List of political parties in Catalonia, p ...

(ERC) and others), the Spanish right wing planned their military ''coup d'état'' against the democratic Republic to reinstall monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

. Finally, on 17 July 1936, a part of the Spanish Army, led by a group of far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

-wing officers (the generals José Sanjurjo

José Sanjurjo y Sacanell (; 28 March 1872 – 20 July 1936), was a Spanish general, one of the military leaders who plotted the July 1936 ''coup d'état'' which started the Spanish Civil War.

He was endowed the nobiliary title of "Marquis o ...

, Manuel Goded Llopis

Manuel Goded Llopis (15 October 1882 – 12 August 1936) was a Spanish Army general who was one of the key figures in the July 1936 revolt against the democratically elected Second Spanish Republic. Having unsuccessfully led an attempted insur ...

, Emilio Mola

Emilio Mola y Vidal, 1st Duke of Mola, Grandee of Spain (9 July 1887 – 3 June 1937) was one of the three leaders of the Nationalist coup of July 1936, which started the Spanish Civil War.

After the death of Sanjurjo on 20 July 1936, Mo ...

, Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

, Miguel Cabanellas, Gonzalo Queipo de Llano

Gonzalo Queipo de Llano y Sierra (5 February 1875 – 9 March 1951) was a Spanish military leader who rose to prominence during the July 1936 coup and then the Spanish Civil War and the White Terror.

Biography

A career army man, Queipo de Lla ...

, José Enrique Varela

José Enrique Varela Iglesias, 1st Marquis of San Fernando de Varela (17 April 1891 – 24 March 1951) was a Spanish military officer noted for his role as a Nationalist commander in the Spanish Civil War.

Early career

Varela started his milita ...

, and others) launched a military ''coup d'état'' against the Spanish Republic in July 1936. The generals' ''coup d'état'' failed, but the rebellious army, known as the Nationalists, controlled a large part of Spain; the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

had started.

Franco, one of the leaders of the coup, and his Nationalist army, won the Spanish civil war in 1939. Franco ruled Spain for the next 36 years, until his death in 1975. Besides the mass assassinations of republican political enemies, political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although n ...

s were interned to concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

s and homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

s were interned to psychiatric hospitals.

Repressive thinking

To know the repressive guidelines, we can cite the sentence of the Chief Prosecutor of the Francoist army, Felipe Acedo Colunga, mentioned in the internal report of 1939 for the different audits, with very clear sentences such as:The native land must be disinfected beforehand. And here is the workweight and gloryentrusted by chance of destiny to military justiceAccording to historian Francisco Espinosa, Felipe Acedo proposed an exemplary model of repression to create the new fascist state "on the site of the race." Absolute purification was needed, "stripped of all feelings of personal piety." According to Espinosa, the legal model for repression was the German (

National Socialist

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

) procedural system, where the prosecutor could act outside legal considerations. What was important was the unwritten right that, according to Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

, peoples carry as "a sacred ember in their blood."

Aside, specifically about Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

, (one of the main reasons of the war, upon Franco

Franco may refer to:

Name

* Franco (name)

* Francisco Franco (1892–1975), Spanish general and dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1975

* Franco Luambo (1938–1989), Congolese musician, the "Grand Maître"

Prefix

* Franco, a prefix used when ref ...

words) can be chosen the statements of Queipo de Llano

Gonzalo Queipo de Llano y Sierra (5 February 1875 – 9 March 1951) was a Spanish military leader who rose to prominence during the July 1936 coup and then the Spanish Civil War and the White Terror.

Biography

A career army man, Queipo de Llan ...

in the article subtitled "Against Catalonia, the Israel of the modern world", published in the Diario Palentino

Diario (Italian, Spanish "Diary") and ''El Diario'' (Spanish, "The Daily") may refer to:

Newspapers, periodicals and websites

* ''El Diario'' (Argentina)

* ''Diario'' (Aruba)

* ''El Diario'' (La Paz), Bolivia

* ''Diario Extra'' (Costa Rica)

*''Di ...

on November 26, 1936, where it states that in America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

they consider the Catalans

Catalans (Catalan language, Catalan, French language, French and Occitan language, Occitan: ''catalans''; es, catalanes, Italian language, Italian: ''catalani'', sc, cadelanos) are a Romance languages, Romance ethnic group native to Cataloni ...

as "a race of Jews, because they use the same procedures that the Hebrews

The terms ''Hebrews'' (Hebrew: / , Modern: ' / ', Tiberian: ' / '; ISO 259-3: ' / ') and ''Hebrew people'' are mostly considered synonymous with the Semitic-speaking Israelites, especially in the pre-monarchic period when they were still no ...

perform in all the nations of the globe." And considering the Catalans as Hebrews and having in mind his anti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

"Our struggle is not a civil war, but a war for Western civilization against the Jewish world," it is not surprising that Queipo de Llano clearly expressed his anti-Catalan intentions: "When the war is over, Pompeu Fabra

Pompeu Fabra i Poch (; Gràcia, Barcelona, 20 February 1868 – Prada de Conflent, 25 December 1948) was a Spanish engineer and grammarian. He was the main author of the normative reform of contemporary Catalan language.

Life

Pompeu Fabra w ...

and his works will be dragged along the Ramblas

La Rambla () is a street in central Barcelona. A tree-lined pedestrian street, it stretches for connecting the in its center with the Christopher Columbus Monument at Port Vell. La Rambla forms the boundary between the neighbourhoods of the ...

" (it was not talk to talk, the house of Pompeu Fabra

Pompeu Fabra i Poch (; Gràcia, Barcelona, 20 February 1868 – Prada de Conflent, 25 December 1948) was a Spanish engineer and grammarian. He was the main author of the normative reform of contemporary Catalan language.

Life

Pompeu Fabra w ...

, the standardizer of Catalan language

Catalan (; autonym: , ), known in the Valencian Community and Carche as ''Valencian'' (autonym: ), is a Western Romance language. It is the official language of Andorra, and an official language of three autonomous communities in eastern Spa ...

, was raided and his huge personal library burned in the middle of the street. Pompeu Fabra was able to escape into exile).

Red and White Terrors

From the beginning of the war, in July 1936, the ideological nature of the Nationalist fight against the Republicans indicated the degree of dehumanisation of the lower social classes (peasants and workers) in the view of the politically-reactionary sponsors of the nationalist forces, the Roman Catholic Church of Spain, the aristocracy, the landowners, and the military, commanded by Franco. Captain Gonzalo de Aguilera y Munro, a public affairs officer for the Nationalist forces, told the American reporterJohn Thompson Whitaker

John Thompson Whitaker (January 25, 1906 in Chattanooga, Tennessee – September 11, 1946) was an American writer and journalist who served as a correspondent for several prominent newspapers in different parts of the world.

Training and ea ...

:

The Nationalists committed their atrocities in public, sometimes with assistance from members of the local Catholic Church clergy. In August 1936, the Massacre of Badajoz ended with the shooting of some 4,000 Republicans, according to the most comprehensive studies; on August 20, after a Mass and a multitudinous parade, two Republican city mayors (Juan Antonio Rodríguez Machín and Sinforiano Madroñero), Socialist deputy Nicolás de Pablo and 15 other people (7 of them Portuguese) were publicly executed. It was also a common practice the assassination of hospitalized and wounded Republican soldiers.

Among the children of the landlords, the joke name ''Reforma agraria'' (agrarian reform) identified the horseback hunting parties by which they killed insubordinate peasantry and so cleansed their lands of communists; moreover, the joke name alluded to the grave where the corpses of the hunted peasants were dumped: the piece of land for which the dispossessed peasants had revolted. Early in the civil war most of the victims of the White Terror and the Red Terror were killed in mass executions behind the respective front lines of the Nationalist and of the Republican forces:

Common to the political purges of the left-wing and right-wing belligerents were the ''sacas'', the taking out of prisoners from the jails and the prisons, who then were taken for a ''paseo'', a ride to summary execution

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes include ...

. Most of the men and women taken out from the prisons and jails were killed by death squad

A death squad is an armed group whose primary activity is carrying out extrajudicial killings or forced disappearances as part of political repression, genocide, ethnic cleansing, or revolutionary terror. Except in rare cases in which they are ...

s, from the trade unions, and by the paramilitary militias of the political parties (the Republican CNT, UGT, and PCE; the Nationalist ''Falange'' and Carlist). Among the justifications for summary execution of right-wing enemies was reprisal for aerial bombings of civilians, other people were killed after being denounced as an enemy of the people, by false accusations motivated by personal envy and hatred. Nevertheless, the significant differences between White political terrorism and Red political terrorism was indicated by Francisco Partaloa, prosecutor of the Supreme Court of Madrid (Tribunal Supremo de Madrid) and a friend of the aristocrat General Queipo de Llano, who witnessed the assassinations, first in the Republican camp and then in the Nationalist camp of the Spanish Civil War:

Historians of the Spanish Civil War, such as Helen Graham, Paul Preston, Antony Beevor, Gabriel Jackson, Hugh Thomas, and Ian Gibson concurred that the mass killings realized behind the Nationalist front lines were organized and approved by the Nationalist rebel authorities, while the killings behind the Republican front lines resulted from the societal breakdown of the Second Spanish Republic:

In the second volume of ''A History of Spain and Portugal'' (1973), Stanley Payne

Stanley George Payne (born September 9, 1934) is an American historian of modern Spain and European Fascism at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He retired from full-time teaching in 2004 and is currently Professor Emeritus at its Department ...

said that the political violence in the Republican zone was organized by the left-wing political parties:

That, unlike the political repression by the right wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this pos ...

, which "was concentrated against the most dangerous opposition elements", the Republican attacks were irrational, which featured the "murdering finnocent people, and letting some of the more dangerous go free. Moreover, one of the main targets of the Red terror was the clergy, most of whom were not engaged in overt opposition" to the Spanish Republic. Nonetheless, in a letter-to-the-editor of the ''ABC'' newspaper in Seville, Miguel de Unamuno

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo (29 September 1864 – 31 December 1936) was a Spanish essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher, professor of Greek and Classics, and later rector at the University of Salamanca.

His major philosophical essay w ...

said that, unlike the assassinations in the areas held by the Republic, the methodical assassinations effected by the White Terror were ordered by the highest authorities of the Nationalist rebellion, and identified General Mola as the proponent of the political cleansing policies of the White Terror.

When news of the mass killings of Republican soldiers and sympathizersGeneral Mola's policy to terrorise the Republicansreached the Republican government, the Defence Minister Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto Tuero (30 April 1883 – 11 February 1962) was a Spanish politician, a minister and one of the leading figures of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the years before and during the Second Spanish Republic.

Early life ...

pleaded with the Spanish republicans:

Moreover, despite his political loyalty to the reactionary rebellion of the Nationalists, the right-wing writer José María Pemán

José María Pemán y Pemartín (8 May 1897 in Cadiz – 19 July 1981, Ibid.) was a Spanish journalist, poet, playwright, novelist, essayist, and monarchist intellectual.

Biography

Originally a student of law, he entered the literary world with ...

was concerned about the volume of the mass killings; in ''My Lunches with Important People'' (1970), he reported a conversation with General Miguel Cabanellas in late 1936:

Civil War

The White Terror commenced on 17 July 1936, the day of the Nationalist ''coup d'état'', with hundreds of assassinations effected in the area controlled by the right-wing rebels, but it had been planned before earlier. In the 30 June 1936 secret instructions for the ''coup d'état'' in Morocco, Mola ordered the rebels "to eliminate left-wing elements, communists, anarchists, union members, etc." The White Terror included the repression of political opponents in areas occupied by the Nationalist, mass executions in areas captured from the Republicans, such as the Massacre of Badajoz, and looting.

In ''The Spanish Labyrinth'' (1943),

The White Terror commenced on 17 July 1936, the day of the Nationalist ''coup d'état'', with hundreds of assassinations effected in the area controlled by the right-wing rebels, but it had been planned before earlier. In the 30 June 1936 secret instructions for the ''coup d'état'' in Morocco, Mola ordered the rebels "to eliminate left-wing elements, communists, anarchists, union members, etc." The White Terror included the repression of political opponents in areas occupied by the Nationalist, mass executions in areas captured from the Republicans, such as the Massacre of Badajoz, and looting.

In ''The Spanish Labyrinth'' (1943), Gerald Brenan

Edward FitzGerald "Gerald" Brenan, CBE, MC (7 April 1894 – 19 January 1987) was a British writer and hispanist who spent much of his life in Spain.

Brenan is best known for '' The Spanish Labyrinth'', a historical work on the background t ...

said that:

... thanks to the failure of the ''coup d'état'' and to the eruption of the Falangist and Carlist militias, with their previously prepared lists of victims, the scale on which these executions took place exceeded all precedent. Andalusia, where the supporters of Franco were a tiny minority, and where the military commander, General Queipo de Llano, was a pathological figure recalling the Conde de España of theOther examples include the bombing of civilian areas such asFirst Carlist War The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain from 1833 to 1840, the first of three Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the Monarchy of Spain, Spanish monarchy: the conservative a ..., was drenched in blood. The famous massacre of Badajoz was merely the culminating act of a ritual that had already been performed in every town and village in the South-West of Spain.

Guernica

Guernica (, ), official name (reflecting the Basque language) Gernika (), is a town in the province of Biscay, in the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country, Spain. The town of Guernica is one part (along with neighbouring Lumo) of the mu ...

, Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, Málaga

Málaga (, ) is a municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most pop ...

, Almería

Almería (, , ) is a city and municipality of Spain, located in Andalusia. It is the capital of the province of the same name. It lies on southeastern Iberia on the Mediterranean Sea. Caliph Abd al-Rahman III founded the city in 955. The city gr ...

, Lérida

Lleida (, ; Spanish: Lérida ) is a city in the west of Catalonia, Spain. It is the capital city of the province of Lleida.

Geographically, it is located in the Catalan Central Depression. It is also the capital city of the Segrià comarca, as ...

, Alicante

Alicante ( ca-valencia, Alacant) is a city and municipality in the Valencian Community, Spain. It is the capital of the province of Alicante and a historic Mediterranean port. The population of the city was 337,482 , the second-largest in t ...

, Durango

Durango (), officially named Estado Libre y Soberano de Durango ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Durango; Tepehuán: ''Korian''; Nahuatl: ''Tepēhuahcān''), is one of the 31 states which make up the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico, situated in ...

, Granollers

Granollers () is a city in central Catalonia, about 30 kilometres north-east of Barcelona. It is the capital and most densely populated city in the comarca of Vallès Oriental.

Granollers is now a bustling business centre, having grown from a t ...

, Alcañiz, Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, Valencia and the Municipalities of Spain, third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is ...

and Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

by the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

''(Legion Condor

The Condor Legion (german: Legion Condor) was a unit composed of military personnel from the air force and army of Nazi Germany, which served with the Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War of July 1936 to March 1939. The Condor Legio ...

)'' and the Italian air force

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march = (Ordinance March of the Air Force) by Alberto Di Miniello

, mascot =

, anniversaries = 28 March ...

''(Aviazione Legionaria

The Legionary Air Force ( it, Aviazione Legionaria, es, Aviación Legionaria) was an expeditionary corps from the Italian Royal Air Force that was set up in 1936. It was sent to provide logistical and tactical support to the Nationalist facti ...

)'' (according to Gabriel Jackson Gabriel Jackson may refer to:

* Gabriel Jackson (composer)

Gabriel Jackson (born 1962 in Hamilton, Bermuda) is an English composer. He is a three-time winner of the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors British Composer Award. Fr ...

estimates range from 5,000 to 10,000 victims of the bombings), killings of Republican POWs

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

, rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ag ...

, forced disappearances

An enforced disappearance (or forced disappearance) is the secret abduction or imprisonment of a person by a state or political organization, or by a third party with the authorization, support, or acquiescence of a state or political organiza ...

including whole Republican military units such as the 221st Mixed Brigadeand the establishment of Francoist prisons in the aftermath of the Republicans' defeat.

Goals and victims of the repression

The main goal of the White Terror was to terrify the civil population who opposed the coup, eliminate the supporters of the Republic and the militants of the leftist parties, and because of this, some historians have considered the White Terror a genocide. In fact, one of the leaders of the coup, General Mola, said: Sánchez Léon says that the tanatopolitics and thebiopolitics

Biopolitics refers to the political relations between the administration or regulation of the life of species and a locality's populations, where politics and law evaluate life based on perceived constants and traits. French philosopher Michel F ...

of the Francoist repression simultaneously obeyed to the logics of a civil war, a colonial conquest and a Catholic holy war, unleashed upon a population hitherto considered part of the same community. Features such as the institutional processes, policies and practices put in motion by the victors, the indiscriminate massacres, the re-catholisation of the defeated, the forced exile and the exclusion from the benefits of full citizenship or the application of retroactive repressive rulings crystallised in the definition of the Republicans as anti-Spanish, a terminology that intermingles the perception of the enemies as "non-citizens", as "inferior beings" and as alien to the values that defined the self-imagined (confessional) nation. Behind the generic term 'Reds' there was a notion of enemy in an absolute sense, targeted for eradication.

In areas controlled by the Nationalists, government officials, Popular Front politicians (in the city of Granada 23 of the 44 councillors of the city's corporation were executed), union leaders, teachers (in the first weeks of the war hundreds of teachers were killed by the Nationalists), intellectuals (for example, in Granada, between 26 July 1936 and 1 March 1939, the poet Federico García Lorca

Federico del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús García Lorca (5 June 1898 – 19 August 1936), known as Federico García Lorca ( ), was a Spanish poet, playwright, and theatre director. García Lorca achieved international recognition as an emblemat ...

, the editor of the left-wing newspaper ''El Defensor de Granada

''El Defensor de Granada'' (The Defender of Granada) was a Spanish newspaper with liberal-progressive ideology that was published in Granada between the end of the 19th century and the first third of the 20th century. It disappeared after the outb ...

'', the professor of paediatrics in the Granada University, the rector of the university, the professor of political law, the professor of pharmacy, the professor of history, the engineer of the road to the top of the Sierra Morena and the best-known doctor in the city were killed by the Nationalists, and in the city of Cordoba, "nearly the entire republican elite, from deputies to booksellers, were executed in August, September and December..."), suspected Freemasons

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

(in Huesca, where there were only twelve Freemasons, the Nationalists killed a hundred suspected Freemasons), Basque

Basque may refer to:

* Basques, an ethnic group of Spain and France

* Basque language, their language

Places

* Basque Country (greater region), the homeland of the Basque people with parts in both Spain and France

* Basque Country (autonomous co ...

, Catalan

Catalan may refer to:

Catalonia

From, or related to Catalonia:

* Catalan language, a Romance language

* Catalans, an ethnic group formed by the people from, or with origins in, Northern or southern Catalonia

Places

* 13178 Catalan, asteroid #1 ...

, Andalusian or Galician nationalists (among them Manuel Carrasco i Formiguera, leader of Democratic Union of Catalonia

The Democratic Union of Catalonia ( ca, Unió Democràtica de Catalunya; , UDC), frequently shortened as Union ( ca, Unió; ), was a regionalist, Christian-democratic political party in the Catalonia region of Spain existing between 1931 and 2017 ...

''Unió Democrática de Catalunya'', Alexandre Boveda, one of the founders of the '' Partido Galeguista'' and Blas Infante

Blas Infante Pérez de Vargas (5 July 1885 – 11 August 1936) was a Spanish Andalusist politician, Georgist, writer, historian and musicologist, known as the father of Andalusian nationalism ''(Padre de la Patria Andaluza)''.

Infante was a ...

, leader of the Andalusian nationalism), military officers who had remained loyal to the government of the Republic (among them the Army generals Domingo Batet, Enrique Salcedo Molinuevo, Miguel Campíns, Nicolás Molero, Nuñez de Prado, Manuel Romerales and Rogelio Caridad Pita), and people suspected of voting for the Popular Front were targeted, usually brought before local committees and imprisoned or executed. The living conditions in the improvised Nationalist prisons were very harsh. One former Republican prisoner declared:

At times we were forty prisoners in a cell built to accommodate two people. There were two benches, each capable of seating three persons, and the floor to sleep on. For our private needs, there were only three chamberpots. They had to be emptied into an old rusty cauldron which also served for washing our clothes. We were forbidden to have food brought to us from outside, and were given disgusting soup cooked with soda ash which kept us in a constant state of dysentery. We were all in a deplorable state. The air was unbreathable and the babies choked many nights for lack of oxygen... To be imprisoned, according to the rebels, was to lose all individuality. The most elementary human rights were unknown and people were killed as easily as rabbits...Because of this mass terror in many areas controlled by the Nationalists, thousands of Republicans left their homes and tried to hide in nearby forests or mountains. Many of these ''huidos'' later joined the

Spanish maquis

The Maquis were Spanish guerrillas who waged an irregular warfare against the Francoist dictatorship within Spain following the Republican defeat in the Spanish Civil War until the early 1960s, carrying out sabotage, robberies (to help fund g ...

, the anti-Francoist guerrilla force that continued to fight against the Francoist State in the post-war era. Hundreds of thousands of others fled to the areas controlled by the Second Republic. In 1938 there were more than one million refugees in Barcelona alone. In many cases, when someone fled the Nationalists executed their relatives. One witness in Zamora stated: "All the members of the Flechas family, both men and women, were killed, a total of seven persons. A son succeeded in escaping, but in his place they killed his eight-months-pregnant fiancé Transito Alonso and her mother, Juana Ramos." Furthermore, thousands of republicans joined ''Falange'' and the Nationalist army in order to escape the repression. In fact, many supporters of the Nationalists referred to the ''Falange'' as "our reds" and to the ''Falanges blue shirt as the ''salvavidas'' (life jacket). In Granada, one supporter of the Nationalists said:

Another major target of the Terror were women, with the overall goal of keeping them in their traditional place in Spanish society. To this end the Nationalist army promoted a campaign of targeted rape. Queipo de Llano spoke multiple times over the radio warning that "immodest" women with Republican sympathies would be raped by his Moorish troops. Near Seville, Nationalist soldiers raped a truckload of female prisoners, threw their bodies down a well, and paraded around town with their rifles draped with their victim's underwear. These rapes were not the result of soldiers disobeying orders, but official Nationalist policies, with officers specifically choosing Moors to be the primary perpetrators. Advancing nationalist troops scrawled "Your children will give birth to fascists" on the walls of captured buildings, and many women taken prisoner were force fed castor oil

Castor oil is a vegetable oil pressed from castor beans.

It is a colourless or pale yellow liquid with a distinct taste and odor. Its boiling point is and its density is 0.961 g/cm3. It includes a mixture of triglycerides in which about ...

, then paraded in public naked, while the powerful laxative

Laxatives, purgatives, or aperients are substances that loosen stools and increase bowel movements. They are used to treat and prevent constipation.

Laxatives vary as to how they work and the side effects they may have. Certain stimulant, lubri ...

did its work.

Death toll

Estimates of executions behind the Nationalist lines during the Spanish Civil War range from fewer than 50,000 to 200,000 (Hugh Thomas: 75,000, Secundino Serrano: 90,000; Josep Fontana: 150,000; and Julián Casanova: 100,000.Casanova, Julián. ''The Spanish Republic and Civil War''. Cambridge University Press. 2010. New York. p. 181. Most of the victims were killed without a trial in the first months of the war and their corpses were left on the sides of roads or in clandestine and unmarked mass graves. For example, in Valladolid only 374 officially recorded victims of the repression of a total of 1,303 (there were many other unrecorded victims) were executed after a trial, and the historian Stanley Payne in his work ''Fascism in Spain'' (1999), citing a study by Cifuentes Checa and Maluenda Pons carried out over the Nationalist-controlled city of Zaragoza and its environs, refers to 3,117 killings, of which 2,578 took place in 1936. He goes on to state that by 1938 the military courts there were directing summary executions.

Many of the executions in the course of the war were carried by militants of the fascist party ''Falange'' ('' Falange Española de las J.O.N.S.'') or militants of the

Estimates of executions behind the Nationalist lines during the Spanish Civil War range from fewer than 50,000 to 200,000 (Hugh Thomas: 75,000, Secundino Serrano: 90,000; Josep Fontana: 150,000; and Julián Casanova: 100,000.Casanova, Julián. ''The Spanish Republic and Civil War''. Cambridge University Press. 2010. New York. p. 181. Most of the victims were killed without a trial in the first months of the war and their corpses were left on the sides of roads or in clandestine and unmarked mass graves. For example, in Valladolid only 374 officially recorded victims of the repression of a total of 1,303 (there were many other unrecorded victims) were executed after a trial, and the historian Stanley Payne in his work ''Fascism in Spain'' (1999), citing a study by Cifuentes Checa and Maluenda Pons carried out over the Nationalist-controlled city of Zaragoza and its environs, refers to 3,117 killings, of which 2,578 took place in 1936. He goes on to state that by 1938 the military courts there were directing summary executions.

Many of the executions in the course of the war were carried by militants of the fascist party ''Falange'' ('' Falange Española de las J.O.N.S.'') or militants of the Carlist

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty – one descended from Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855) – ...

party ('' Comunión Tradicionalista'') militia ('' Requetés''), but with the approval of the Nationalist government.

Cooperation of the Spanish Church

The Spanish Church approved of the White Terror and cooperated with the rebels. According to Antony Beevor:Cardinal Gomá stated that 'Jews and Masons poisoned the national soul with absurd doctrine'... A few brave priests put their lives at risk by criticizing nationalist atrocities, but the majority of the clergy in nationalist areas revelled in their new-found power and the increased size of their congregations. Anyone who did not attend Mass faithfully was likely to be suspected of 'red' tendencies. Entrepreneurs made a great money selling religious symbols... It was reminiscent of the way the Inquisition's persecutions of Jews and Moors helped make pork such an important part of the Spanish diet.One witness in Zamora said:

Many priests acted very badly. The bishop of Zamora in 1936 was more or less an assassinI don't remember his name. He must be held responsible because prisoners appealed to him to save their lives. All he would reply was that the Reds had killed more people than the falangist were killing.(The bishop of Zamora in 1936 was Manuel Arce y Ochotorena) Nevertheless, the Nationalists killed at least 16 Basque nationalist priests (among them the arch-priest of Mondragon), and imprisoned or deported hundreds more. Several priests who tried to halt the killings and at least one priest who was a Mason were killed. Regarding the callous attitude of the

Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

, Manuel Montero

Manuel "Pantera" Montero (born November 20, 1991 in Buenos Aires)Manuel player profi ...

, lecturer of the University of the Basque Country

The University of the Basque Country ( eu, Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea, ''EHU''; es, Universidad del País Vasco, ''UPV''; UPV/EHU) is a Spanish public university of the Basque Autonomous Community. Heir of the University of Bilbao, initiall ...

commented on 6 May 2007:

Repression in the South and the drive to Madrid

The White Terror was especially harsh in the southern part of Spain (Andalusia and Extremadura). The rebels bombed and seized the working-class districts of the main Andalusian cities in the first days of the war, and afterwards went on to execute thousands of workers and militants of the leftist parties: in the city of Cordoba 4,000; in the city of Granada 5,000; in the city ofSeville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

3,028; and in the city of Huelva 2,000 killed and 2,500 disappeared. The city of Málaga, occupied by the Nationalists in February 1937 following the Battle of Málaga, experienced one of the harshest repressions following Francoist victory with an estimated total of 17,000 people summarily executed. Carlos Arias Navarro

Carlos Arias Navarro, 1st Marquis of Arias-Navarro (11 December 1908 – 27 November 1989) was one of the best-known Spanish politicians during the Francoist regime.

Arias Navarro was a moderate leader in the last phase of Francoism and the be ...

, then a young lawyer who as public prosecutor signed thousands of execution warrants in the trials set up by the triumphant rightists, became known as "The Butcher of Málaga" (''Carnicero de Málaga''). Over 4,000 people were buried in mass graves.

Even towns of rural areas were not spared the terror, such as Lora del Rio in the province of Seville

The Province of Seville ( es, Sevilla) is a province of southern Spain, in the western part of the autonomous community of Andalusia. It is bordered by the provinces of Málaga, Cádiz in the south, Huelva in the west, Badajoz in the north and C ...

, where the Nationalists killed 300 peasants as a reprisal for the assassination of a local landowner. In the province of Córdoba the Nationalists killed 995 Republicans in Puente Genil

Puente Genil () is a Jonian city in the province of Jonia, autonomous community of Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonom ...

and about 700 loyalists were murdered by the orders of Nationalist Colonel Sáenz de Buruaga in Baena, although other estimates mention up to 2,000 victims following the Baena Massacre.

Paul Preston estimates the total number of victims of the Nationalists in Andalusia at 55,000.

Troops of North Africa

The colonial troops of theSpanish Army of Africa

The Army of Africa ( es, Ejército de África, ar, الجيش الإسباني في أفريقيا, Al-Jaysh al-Isbānī fī Afriqā) or Moroccan Army Corps ( es, Cuerpo de Ejército Marroquí') was a field army of the Spanish Army that garriso ...

(''Ejército de África''), composed mainly of the Moroccan ''regulares

The Fuerzas Regulares Indígenas ("Indigenous Regular Forces"), known simply as the Regulares (Regulars), are volunteer infantry units of the Spanish Army, largely recruited in the cities of Ceuta and Melilla. Consisting of indigenous infantry ...

'' and the Spanish Legion

For centuries, Spain recruited foreign soldiers to its army, forming the Foreign Regiments () - such as the Regiment of Hibernia (formed in 1709 from Irishmen who fled their own country in the wake of the Flight of the Earls and the penal ...

, under the command of Colonel Juan Yagüe

Juan Yagüe y Blanco, 1st Marquis of San Leonardo de Yagüe (19 November 1891 – 21 October 1952) was a Spanish military officer during the Spanish Civil War, one of the most important in the Nationalist side. He became known as the "Butcher o ...

, made up the feared shock troops

Shock troops or assault troops are formations created to lead an attack. They are often better trained and equipped than other infantry, and expected to take heavy casualties even in successful operations.

"Shock troop" is a calque, a loose tra ...

of the Francoist military. In their advance towards Madrid from Sevilla through Andalusia and Extremadura

Extremadura (; ext, Estremaúra; pt, Estremadura; Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is an autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central-western part of the Iberian Peninsula, it ...

these troops routinely killed dozens or hundreds in every town or city conquered. but in the Massacre of Badajoz the number of Republicans killed reached several thousands. Furthermore, the colonial troops raped many working-class women and looted the houses of the Republicans. Queipo de Llano, one of the Nationalists leaders known for his use of radio broadcasts as a means of psychological warfare

Psychological warfare (PSYWAR), or the basic aspects of modern psychological operations (PsyOp), have been known by many other names or terms, including Military Information Support Operations (MISO), Psy Ops, political warfare, "Hearts and Mi ...

, said:

Anti-Catalan hostility

Catalonia suffered the most fierce engagements during the civil war, as seen in several examples. In

Catalonia suffered the most fierce engagements during the civil war, as seen in several examples. In Tarragona

Tarragona (, ; Phoenician: ''Tarqon''; la, Tarraco) is a port city located in northeast Spain on the Costa Daurada by the Mediterranean Sea. Founded before the fifth century BC, it is the capital of the Province of Tarragona, and part of Tar ...

, in January 1939, mass was held by a canon from Salamanca

Salamanca () is a city in western Spain and is the capital of the Province of Salamanca in the autonomous community of Castile and León. The city lies on several rolling hills by the Tormes River. Its Old City was declared a UNESCO World Heritag ...

cathedral, José Artero. During the sermon he cried: "Catalan dogs! You are not worthy of the sun that shines on you." (''"¡Perros catalanes! No sois dignos del sol que os alumbra.")'' Regarding the men who entered and marched through Barcelona, Franco said the honour was not ''"because they had fought better, but because they were those who felt more hatred. That is, more hatred towards Catalonia and Catalans." ("porque hubieran luchado mejor, sino porque eran los que sentían más odio. Es decir, más odio hacia Cataluña y los catalanes.")''

A close friend of Franco, Victor Ruiz Albéniz, published an article in which he demanded that Catalonia receive "a Biblical punishment (Sodom and Gomarrah) to purify the red city, the headquarters of anarchism and separatism as the only remedy to remove these two cancers by relentless cauterisation" (''"un castigo bíblico (Sodoma y Gomorra) para purificar la ciudad roja, la sede del anarquismo y separatismo como único remedio para extirpar esos dos cánceres por termocauterio implacable")'', while for Serrano Suñer, brother-in-law of Franco and Minister of the Interior, Catalan nationalism was "an illness" ("una enfermedad.")

The man appointed as civil governor of Barcelona, Wenceslao González Oliveros, said that "Spain was raised, with as much or more force against the dismembered statutes as against Communism and that any tolerance of regionalism would again lead to the same processes of putrefaction that we have just surgically removed." (''"España se alzó, con tanta o más fuerza contra los Estatutos desmembrados que contra el comunismo y que cualquier tolerancia del regionalismo llevaría otra vez a los mismos procesos de putrefacción que acabamos de extirpar quirúrgicamente.")''

Even Catalan conservatives, such as Francesc Cambó

Francesc Cambó i Batlle (; 2 September 1876 – 30 April 1947) was a conservative Spanish politician from Catalonia, founder and leader of the autonomist party ''Lliga Regionalista''. He was a minister in several Spanish governments. He supported ...

, were themselves frightened by Franco's hatred and spirit of revenge. Cambó wrote of Franco in his diary: "As if he did not feel or understand the miserable, desperate situation in which Spain finds itself and only thinks about his victory, he feels the need to travel the whole country (...) like a bullfighter to gather applause, cigars, hats and some scarce American." (''"Como si no sintiera ni comprendiera la situación miserable, desesperada, en que se encuentra España y no pensara más que en su victoria, siente la necesidad de recorrer todo el país (...) como un torero para recoger aplausos, cigarros, sombreros y alguna americana escasa.")''

The 2nd president of the Generalitat de Catalunya, Lluís Companys, went into exile in

The 2nd president of the Generalitat de Catalunya, Lluís Companys, went into exile in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, like many others, in January 1939. The Spanish authorities asked for him to be extradited to Germany. The questions remains whether he was detained by the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

or the German military police, known as the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

. In any case, he was detained on August 13, 1940, and immediately deported to Franco's Spain.

After a summary court martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

without due process, he was executed on October 15, 1940, at Montjuïc Castle

Montjuïc Castle ( ca, Castell de Montjuïc, es, Castillo de Montjuich) is an old military fortress, with roots dating back from 1640, built on top of Montjuïc hill in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. It currently serves as a Barcelona municipal faci ...

. Since then there have been many calls to cancel that judgement, without success.

Francoist repression

The confluence between Spanishregenerationism

Regenerationism ( es, Regeneracionismo) was an intellectual and political movement in late 19th century and early 20th century Spain. It sought to make objective and scientific study of the causes of Spain's decline as a nation and to propose reme ...

and the degenerationist theories originated in France and Great Britain must also be considered. As a consequence is theorized a racial degeneration causing conflicts against the social status quo, and it is advocated eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

to cleanse one's own race, and racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

to avoid mixing it with "inferior races." During the first third of the s. XX this theorizing towards the " new man" is gaining strength, and its zenith is Nazi racial politics. But in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

it also had an impact, given that the political and social elites who patrimonialize Spain, and who would not digest the colonial loss, see in the Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

and the meager Catalan autonomy a threat to its status, power and wealth. The Catalan industrial wealth cannot be tolerated either, and Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

is accused of having a favorable treatment, impoverishing the rest of the Spaniards, in a behavior that is described as Semitic (according to the National-Socialist ideology to use work as a means to exploit and subjugate nations).

According to Paul Preston

Sir Paul Preston CBE (born 21 July 1946) is an English historian and Hispanist, biographer of Francisco Franco, and specialist in Spanish history, in particular the Spanish Civil War, which he has studied for more than 30 years. He is the win ...

in the book "Arquitectes del terror. Franco i els artifex de l'odi", a number of characters theorized about "anti-Spain", pointing to enemies, and in this sense accused politicians and republican intellectuals of being of Jewish race or servants of the same as masons. This accusation is widespread in Catalonia for most politicians and intellectuals, starting with Macià, Companys and Cambó, identified as Jews. "Racisme i supremacisme polítics a l'Espanya contemporània" documents this thought of the social part that would be raised against the Republic. In a mixture of degenerationism, regenerationism, and neocolonialism, it is postulated that the Spanish racealways understood as Castilianhas degenerated, and degenerate individuals are prone to "contract" communism and separatism. In addition, some areas, such as the south of the peninsula and the Catalan countries

The Catalan Countries ( ca, països catalans, , ) refers to those territories where the Catalan language is spoken. They include the Spanish regions of Catalonia, the Balearic Islands, Valencian Community, Valencia, and parts of Aragon (''La F ...

, are considered to be degenerate wholesale, the former due to Arab remains that lead them to a "rifty" behavior, and the latter due to Semitic remains that lead them towards communism and separatism (the catanalism of any kind is called separatism).

The degeneration of individuals calls for a cleansing if it is wantes a prosperous and leading nation, capable of building an empire, one of the obsessions of Franco (as well as other totalitarian regimes of the time). In this regard, rebel spokesman Gonzalo de Aguilera, in 1937, told a journalist: "''Now I hope you understand what we mean by the regeneration of Spain ... Our program consists of exterminating a third of the Spanish male population ...''", and an interview can also be mentioned in an Italian newspaper where Franco describes that the war was aimed at "''to save the Homeland that was sinking in the sea of dissociation and racial degeneration''".

In addition to the repression throughout Spain against certain individuals, all this seems to be the source of the fierce repression, such as the Terror of Don Bruno, in Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

, and the no less fierce repression against Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

, with the addition that as a result, the attack on Catalan culture, lasted throughout the Franco

Franco may refer to:

Name

* Franco (name)

* Francisco Franco (1892–1975), Spanish general and dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1975

* Franco Luambo (1938–1989), Congolese musician, the "Grand Maître"

Prefix

* Franco, a prefix used when ref ...

regime and ended up becoming a structural element of the state.

Postwar

WhenHeinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

visited Spain in 1940, a year after Franco's victory, he claimed to have been

"shocked" by the brutality of the Falangist repression. In July 1939, the foreign minister of Fascist Italy, Galeazzo Ciano

Gian Galeazzo Ciano, 2nd Count of Cortellazzo and Buccari ( , ; 18 March 1903 – 11 January 1944) was an Italian diplomat and politician who served as Foreign Minister in the government of his father-in-law, Benito Mussolini, from 1936 until 19 ...

, reported of "trials going on every day at a speed which I would call almost summary... There are still a great number of shootings. In Madrid alone, between 200 and 250 a day, in Barcelona 150, in Seville 80". While authors like Payne have cast doubts on the democratic leanings of the Republic, "fascism was clearly on the other".

Repressive laws

According to Beevor, Spain was an open prison for all those who opposed Franco. Until 1963, all the opponents of the Francoist State were brought before military courts. A number of repressive laws were issued, including the Law of Political Responsibilities (''Ley de Responsabilidades Políticas'') in February 1939, the Law of Security of State (''Ley de Seguridad del Estado'') in 1941 (which regarded illegal propaganda or labour strikes as military rebellion), the Law for the Repression of Masonry and Communism (''Ley de Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo'') on 2 March 1940, and the Law for the Repression of Banditry and Terrorism (''Ley para la represión del Bandidaje y el Terrorismo'') in April 1947, which targeted the ''maquis''. Furthermore, in 1940, the Francoist State established the Tribunal for the eradication of Freemasonry and Communism (''Tribunal Especial para la Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo''). Political parties and trade unions were forbidden except for the government party, Traditionalist Spanish Falange and Offensive of the Unions of the National-Syndicalist (''Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista

The Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS; ), frequently shortened to just "FET", was the sole legal party of the Francoist regime in Spain. It was created by General Francisco F ...

'' or FET de las JONS), and the official trade union Spanish Trade Union Organisation

The Spanish Syndical Organization ( es, Organización Sindical Española; OSE), popularly known in Spain as the (the "Vertical Trade Union"), was the sole legal trade union for most of the Francoist dictatorship. A public-law entity created in ...

(''Sindicato Vertical''). Hundreds of militants and supporters of the parties and trade unions declared illegal under Francoist Spain, such as the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español ; PSOE ) is a social-democraticThe PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* political party in Spain. The PSOE has been in gov ...

(''Partido Socialista Obrero Español''), PSOE; the Communist Party of Spain

The Communist Party of Spain ( es, Partido Comunista de España; PCE) is a Marxist-Leninist party that, since 1986, has been part of the United Left coalition, which is part of Unidas Podemos. It currently has two of its politicians serving as ...

(''Partido Comunista de España''), PCE; the Workers' General Union (''Unión General de Trabajadores''), UGT; and the National Confederation of Labor

National may refer to: