Welsh culture on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Wales is often referred to as "the land of song", and is notable for its harpists, male choirs, and solo artists. The principal Welsh festival of music and poetry is the annual ''

Wales is often referred to as "the land of song", and is notable for its harpists, male choirs, and solo artists. The principal Welsh festival of music and poetry is the annual '' Wales has had a number of successful singers. In the 1960s, these included bands such as Amen Corner and The Iveys/

Wales has had a number of successful singers. In the 1960s, these included bands such as Amen Corner and The Iveys/

Several Welsh dishes are thought of as Welsh because their ingredients are associated with Wales, whereas others have been developed there.

Several Welsh dishes are thought of as Welsh because their ingredients are associated with Wales, whereas others have been developed there.  The Welsh have their own versions of

The Welsh have their own versions of

Traditions & History of Wales

via VisitWales.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Culture Of Wales pt:País de Gales#Cultura

The culture of Wales (

However, the Welsh rebelled against their new overlords the following year, and the Welsh kingdoms were re-established and most of the land retaken from the Normans over the following decades. While Gwynedd grew in strength, Powys was broken up after the death of

However, the Welsh rebelled against their new overlords the following year, and the Welsh kingdoms were re-established and most of the land retaken from the Normans over the following decades. While Gwynedd grew in strength, Powys was broken up after the death of

National symbols of Wales include the

National symbols of Wales include the

Before the

Before the

It remained difficult for artists relying on the Welsh market to support themselves until well into the 20th century. An

It remained difficult for artists relying on the Welsh market to support themselves until well into the 20th century. An

, HTV and other independent producers to provide an initial service of 22 hours of Welsh-language television. The digital switchover in Wales of 2009-2010 meant that the previously bilingual Channel 4 split into S4C, broadcasting exclusively in Welsh and Channel 4 broadcasting exclusively in English.

The decision by Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

: ''Diwylliant Cymru'') is distinct, with its own language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of met ...

, customs, politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies ...

, festivals, music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect ...

and Art

Art is a diverse range of human activity, and resulting product, that involves creative or imaginative talent expressive of technical proficiency, beauty, emotional power, or conceptual ideas.

There is no generally agreed definition of wha ...

. Wales is primarily represented by the symbol of the red Welsh Dragon

The Welsh Dragon ( cy, y Ddraig Goch, meaning 'the red dragon'; ) is a heraldic symbol that represents Wales and appears on the national flag of Wales.

As an emblem, the red dragon of Wales has been used since the reign of Cadwaladr, King of ...

, but other national emblem

A national emblem is an emblem or seal that is reserved for use by a nation state or multi-national state as a symbol of that nation. Many nations have a seal or emblem in addition to a national flag and a national coat of arms. Other national sy ...

s include the leek

The leek is a vegetable, a cultivar of ''Allium ampeloprasum'', the broadleaf wild leek ( syn. ''Allium porrum''). The edible part of the plant is a bundle of leaf sheaths that is sometimes erroneously called a stem or stalk. The genus ''Alli ...

and the daffodil

''Narcissus'' is a genus of predominantly spring flowering perennial plants of the amaryllis family, Amaryllidaceae. Various common names including daffodil,The word "daffodil" is also applied to related genera such as '' Sternbergia'', ''Is ...

.

Although sharing many customs with the other nations of the United Kingdom, Wales has its own distinct traditions and culture, and from the late 19th century onwards, Wales acquired its popular image as the "land of song", in part due to the eisteddfod

In Welsh culture, an ''eisteddfod'' is an institution and festival with several ranked competitions, including in poetry and music.

The term ''eisteddfod'', which is formed from the Welsh morphemes: , meaning 'sit', and , meaning 'be', means, a ...

tradition.

Development of Welsh culture

Historical influences

Wales has been identified as having been inhabited by humans for some 230,000 years, as evidenced by the discovery of aNeanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While th ...

at the Bontnewydd Palaeolithic site

The Bontnewydd palaeolithic site (), also known in its unmutated form as Pontnewydd (Welsh language: 'New bridge'), is an archaeological site near St Asaph, Denbighshire, Wales. It is one of only three sites in Britain to have produced fossils ...

in north Wales. After the Roman era

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

of occupation, a number of small kingdoms arose in what is now Wales. These early kingdoms were also influenced by Ireland; but details prior to the 8th century AD are unclear. Kingdoms during that era included Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, and C ...

, Powys

Powys (; ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county and Preserved counties of Wales, preserved county in Wales. It is named after the Kingdom of Powys which was a Welsh succession of states, successor state, petty kingdom and princi ...

and Deheubarth

Deheubarth (; lit. "Right-hand Part", thus "the South") was a regional name for the realms of south Wales, particularly as opposed to Gwynedd (Latin: ''Venedotia''). It is now used as a shorthand for the various realms united under the House of ...

.

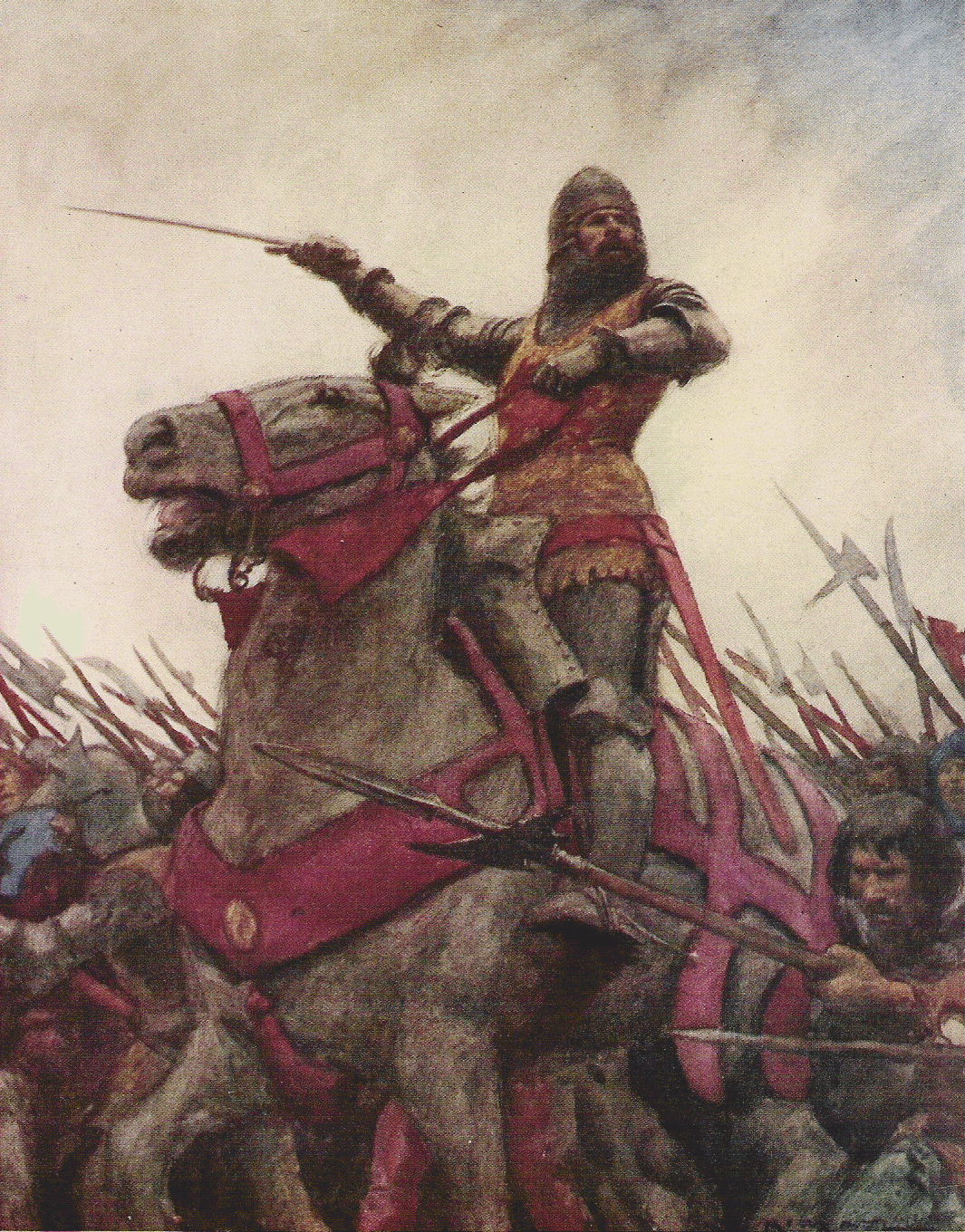

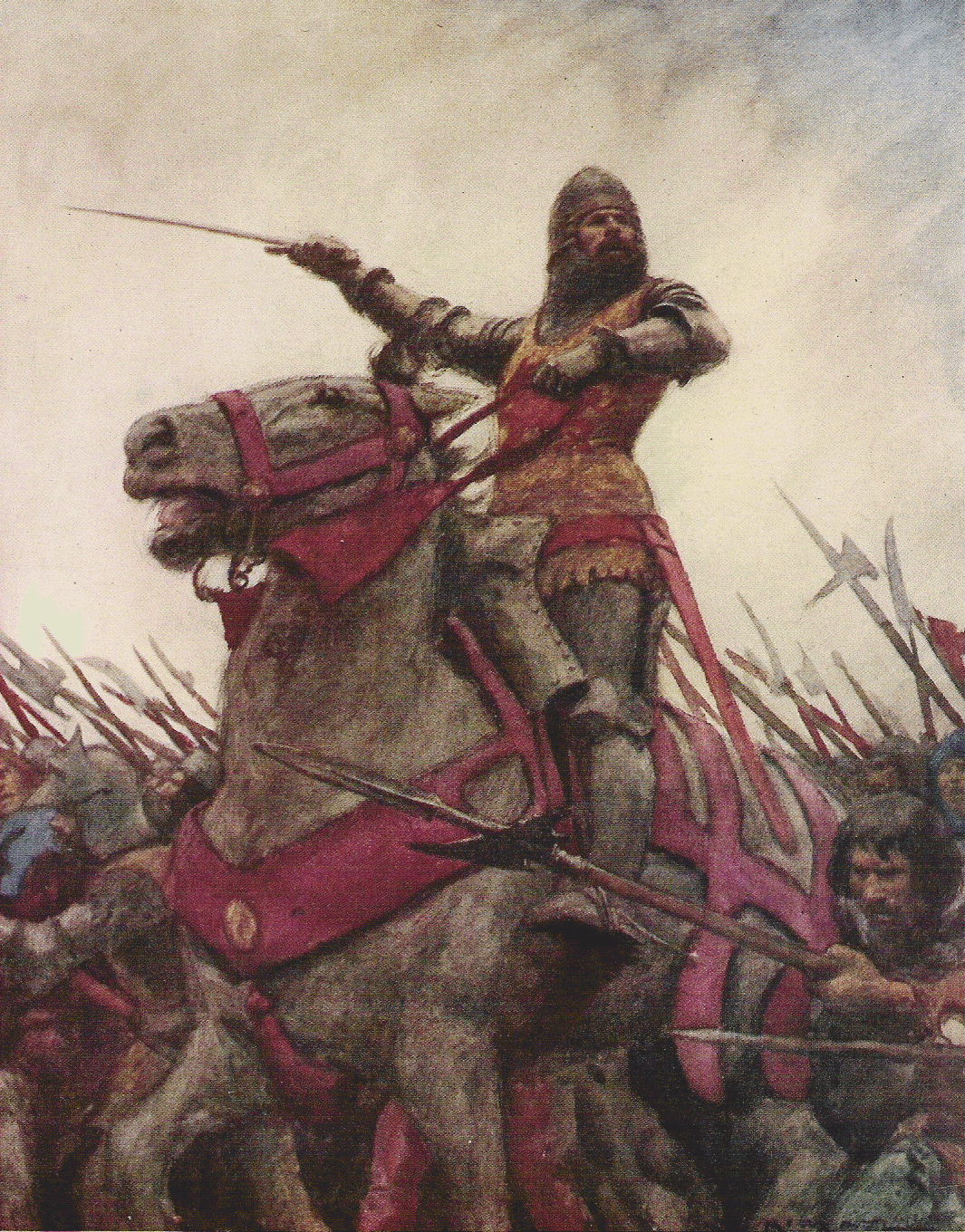

While Rhodri the Great

Rhodri ap Merfyn ( 820 – 873/877/878), popularly known as Rhodri the Great ( cy, Rhodri Mawr), succeeded his father, Merfyn Frych, as King of Gwynedd in 844. Rhodri annexed Powys c. 856 and Seisyllwg c. 871. He is called " King of the Brito ...

in the 9th century was the first ruler to dominate a large portion of Wales, it was not until 1055 that Gruffydd ap Llywelyn

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn ( 5 August 1063) was King of Wales from 1055 to 1063. He had previously been King of Gwynedd and Powys in 1039. He was the son of King Llywelyn ap Seisyll and Angharad daughter of Maredudd ab Owain, and the great-gre ...

united the individual Welsh kingdoms and began to annex parts of England. Gruffydd was killed, possibly in crossfire

A crossfire (also known as interlocking fire) is a military term for the siting of weapons (often automatic weapons such as assault rifles or sub-machine guns) so that their arcs of fire overlap. This tactic came to prominence in World War I.

...

by his own men, on 5 August 1063 while Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson ( – 14 October 1066), also called Harold II, was the last crowned Anglo-Saxon English king. Harold reigned from 6 January 1066 until his death at the Battle of Hastings, fighting the Norman invaders led by William the C ...

sought to engage him in battle. This was just over three years before the Norman invasion of England

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conquer ...

, which led to a drastic change of fortune for Wales. By 1070, the Normans had already seen successes in their invasion of Wales, with Gwent fallen and Deheubarth plundered. The invasion was seemingly complete by 1093.

However, the Welsh rebelled against their new overlords the following year, and the Welsh kingdoms were re-established and most of the land retaken from the Normans over the following decades. While Gwynedd grew in strength, Powys was broken up after the death of

However, the Welsh rebelled against their new overlords the following year, and the Welsh kingdoms were re-established and most of the land retaken from the Normans over the following decades. While Gwynedd grew in strength, Powys was broken up after the death of Llywelyn ap Madog

Llywelyn ap Madog was Dean of St Asaph until 1357 ; and then Bishop of St AsaphHardy, T. Duffus. ''Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae; or, a Calendar of the Principal Ecclesiastical Dignitaries in England and Wales, and of the Chief Officers in the Un ...

in the 1160s and was never reunited. Llywelyn the Great

Llywelyn the Great ( cy, Llywelyn Fawr, ; full name Llywelyn mab Iorwerth; c. 117311 April 1240) was a King of Gwynedd in north Wales and eventually " Prince of the Welsh" (in 1228) and "Prince of Wales" (in 1240). By a combination of war and d ...

rose in Gwynedd and had reunited the majority of Wales by his death in 1240. After his death, King Henry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême, Henry a ...

intervened to prevent Dafydd ap Llywelyn

Dafydd ap Llywelyn (''c.'' March 1212 – 25 February 1246) was Prince of Gwynedd from 1240 to 1246. He was the first ruler in Wales to claim the title Prince of Wales.

Birth and descent

Though birth years of 1208, 1206, and 1215 have ...

from inheriting his father's lands outside Gwynedd, leading to war. The claims of his successor, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (c. 1223 – 11 December 1282), sometimes written as Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, also known as Llywelyn the Last ( cy, Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf, lit=Llywelyn, Our Last Leader), was the native Prince of Wales ( la, Princeps Wall ...

, conflicted with those of King Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassa ...

; this resulted in the conquest of Wales by English forces.

The Tudors of Penmynydd

The Tudors of Penmynydd ( cy, Tuduriaid Penmynydd) were a noble and aristocratic family, connected with the village of Penmynydd in Anglesey, North Wales, who were very influential in Welsh (and later English) politics. From this family arose ...

grew in power and influence during the 13th to 15th centuries, first owning land in north Wales, but losing it after Maredudd ap Tudur

Maredudd ap Tudur (died c. 1406) was a Welsh soldier and nobleman from the Tudor family of Penmynydd. He was one of five sons of Tudur ap Goronwy, and was the father of Owen Tudor. Maredudd supported the Welsh patriot Owain Glyndŵr in 1400, a ...

backed the uprising of Owain Glyndŵr

Owain ap Gruffydd (), commonly known as Owain Glyndŵr or Glyn Dŵr (, anglicised as Owen Glendower), was a Welsh leader, soldier and military commander who led a 15 year long Welsh War of Independence with the aim of ending English rule in Wa ...

in 1400. Maredudd's son, Owain ap Maredudd ap Tudur, anglicised his name to become Owen Tudor

Sir Owen Tudor (, 2 February 1461) was a Welsh courtier and the second husband of Queen Catherine of Valois (1401–1437), widow of King Henry V of England. He was the grandfather of Henry VII, founder of the Tudor dynasty.

Background

Owe ...

, and was the grandfather of Henry Tudor. Henry took the throne of England in 1485, at the end of the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These wars were fought bet ...

, when his forces defeated those of Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Battl ...

at the Battle of Bosworth Field

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of Lancaster and York that extended across England in the latter half of the 15th century. Fought on 22 Augu ...

.

Under Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, the Laws in Wales Acts 1535-1542

The Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 ( cy, Y Deddfau Cyfreithiau yng Nghymru 1535 a 1542) were Acts of the Parliament of England, and were the parliamentary measures by which Wales was annexed to the Kingdom of England. Moreover, the legal sys ...

were passed. The distinction between the Principality of Wales

The Principality of Wales ( cy, Tywysogaeth Cymru) was originally the territory of the native Welsh princes of the House of Aberffraw from 1216 to 1283, encompassing two-thirds of modern Wales during its height of 1267–1277. Following the con ...

and the Marches of Wales

The Welsh Marches ( cy, Y Mers) is an imprecisely defined area along the border between England and Wales in the United Kingdom. The precise meaning of the term has varied at different periods.

The English term Welsh March (in Medieval Latin ...

was ended. The law of England became the only law of Wales which was then administered by justices of the peace that were appointed in every Welsh county. Wales was then represented in parliament by 26 members.

English became the only official language of courts in Wales, and people that used the Welsh language would not be eligible for public office in the territories of the king of England. Welsh was limited to the working and lower middle classes, which played a central role in the public attitude to the language.

The House of Tudor

The House of Tudor was a royal house of largely Welsh and English origin that held the English throne from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd and Catherine of France. Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of England and it ...

continued to reign through several successive monarchs until 1603, when James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

(James VI of Scotland) took the throne for the House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter fi ...

; his great-grandmother was Margaret Tudor

Margaret Tudor (28 November 1489 – 18 October 1541) was Queen of Scotland from 1503 until 1513 by marriage to King James IV. She then served as regent of Scotland during her son's minority, and successfully fought to extend her regency. Marg ...

.

Identity and nationalism

Welsh nationalism ( cy, Cenedlaetholdeb Cymreig) emphasises the distinctiveness ofWelsh language

Welsh ( or ) is a Celtic language family, Celtic language of the Brittonic languages, Brittonic subgroup that is native to the Welsh people. Welsh is spoken natively in Wales, by some in England, and in Y Wladfa (the Welsh colony in Chubut P ...

, culture, and history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

, and calls for more self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

for Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

, which might include more devolved

Devolution is the statutory delegation of powers from the central government of a sovereign state to govern at a subnational level, such as a regional or local level. It is a form of administrative decentralization. Devolved territories h ...

powers for the Senedd

The Senedd (; ), officially known as the Welsh Parliament in English and () in Welsh, is the devolved, unicameral legislature of Wales. A democratically elected body, it makes laws for Wales, agrees certain taxes and scrutinises the Welsh Gove ...

or full independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

. While a sense of nationhood has existed within Wales for over 1500 years, the idea that Wales should be a modern self-determining state has only been mooted since the mid-18th century.

In 1406 Owain Glyndŵr

Owain ap Gruffydd (), commonly known as Owain Glyndŵr or Glyn Dŵr (, anglicised as Owen Glendower), was a Welsh leader, soldier and military commander who led a 15 year long Welsh War of Independence with the aim of ending English rule in Wa ...

set out a vision of Welsh independence

Welsh independence ( cy, Annibyniaeth i Gymru) is the political movement advocating for Wales to become a sovereign state, independent from the United Kingdom.

Wales was conquered during the 13th century by Edward I of England following the ki ...

in his Pennal letter, sent to Charles VI King of France. The letter requested maintained military support from the French to fend off the English in Wales. Glyndŵr suggested that in return, he would recognise Benedict XIII of Avignon as the Pope. The letter sets out the ambitions of Glyndŵr of an independent Wales with its own parliament, led by himself as Prince of Wales. These ambitions also included the return of the traditional law of Hywel Dda

Hywel Dda, sometimes anglicised as Howel the Good, or Hywel ap Cadell (died 949/950) was a king of Deheubarth who eventually came to rule most of Wales. He became the sole king of Seisyllwg in 920 and shortly thereafter established Deheubarth ...

, rather than the enforced English law, establishment of an independent Welsh church as well as two universities, one in south Wales, and one in north Wales.

Symbols

dragon

A dragon is a reptilian legendary creature that appears in the folklore of many cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted as ...

, the daffodil

''Narcissus'' is a genus of predominantly spring flowering perennial plants of the amaryllis family, Amaryllidaceae. Various common names including daffodil,The word "daffodil" is also applied to related genera such as '' Sternbergia'', ''Is ...

and the leek

The leek is a vegetable, a cultivar of ''Allium ampeloprasum'', the broadleaf wild leek ( syn. ''Allium porrum''). The edible part of the plant is a bundle of leaf sheaths that is sometimes erroneously called a stem or stalk. The genus ''Alli ...

. Legend states that the leek dates back to the 7th century, when King Cadwaladr

Cadwaladr ap Cadwallon (also spelled Cadwalader or Cadwallader in English) was king of Gwynedd in Wales from around 655 to 682 AD. Two devastating plagues happened during his reign, one in 664 and the other in 682; he himself was a victim of the ...

of Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, and C ...

had his soldiers wear the vegetable during battle against Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

to make it easier to identify them. Though this same story is recounted in the 17th century, but now attributed to Saint David

Saint David ( cy, Dewi Sant; la, Davidus; ) was a Welsh bishop of Mynyw (now St Davids) during the 6th century. He is the patron saint of Wales. David was a native of Wales, and tradition has preserved a relatively large amount of detail ab ...

. The earliest certain reference of the leek as a Welsh emblem was when Princess Mary, daughter of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, was presented with a leek by the yeoman of the guard on Saint David's Day

Saint David's Day ( cy, Dydd Gŵyl Dewi Sant or ; ), or the Feast of Saint David, is the feast day of Saint David, the patron saint of Wales, and falls on 1 March, the date of Saint David's death in 589 AD. The feast has been regularly celebrat ...

in 1537. The colours of the leek were used for the uniforms of soldiers under Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassa ...

.

Cadwaladr is also said to have introduced the Red Dragon standard Standard may refer to:

Symbols

* Colours, standards and guidons, kinds of military signs

* Standard (emblem), a type of a large symbol or emblem used for identification

Norms, conventions or requirements

* Standard (metrology), an object th ...

, although this symbol was most likely introduced to the British Isles by Roman troops who in turn had acquired it from the Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It thus r ...

ns. It may also have been a reference to the 6th century Welsh word ''draig'', which meant "leader". The standard was appropriated by the Normans during the 11th century, and used for the Royal Standard of Scotland

The Royal Banner of the Royal Arms of Scotland, also known as the Royal Banner of Scotland, or more commonly the Lion Rampant of Scotland, and historically as the Royal Standard of Scotland, ( gd, Bratach rìoghail na h-Alba, sco, Ryal banner ...

. Richard I of England

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was ...

took a red dragon standard with him on the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by three European monarchs of Western Christianity (Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor) to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by ...

.

Both symbols were popular with Tudor kings, with Henry VII of England

Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henry's mother, Margaret Beaufort ...

(Henry Tudor) adding the white and green background to the red dragon standard. It was largely forgotten by the House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelt Stewart, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been held by the family progenitor Walter fi ...

, who favoured a unicorn

The unicorn is a legendary creature that has been described since antiquity as a beast with a single large, pointed, spiraling horn projecting from its forehead.

In European literature and art, the unicorn has for the last thousand years o ...

instead. By the 17th and 18th centuries, it became common practice in Great Britain for the gentry to wear leeks on St. David's Day

Saint David's Day ( cy, Dydd Gŵyl Dewi Sant or ; ), or the Feast of Saint David, is the feast day of Saint David, the patron saint of Wales, and falls on 1 March, the date of Saint David's death in 589 AD. The feast has been regularly celebrat ...

. In 1807, a "a red dragon passant standing on a mound" was made the King's badge for Wales. Following an increase in nationalism in 1953, it was proposed to add the motto ''Y ddraig goch ddyry cychwyn'' ("the red dragon takes the lead") to the flag. This was poorly received, and six years later Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

intervened to put the current flag in place. It has been proposed that the flag of the United Kingdom

The national flag of the United Kingdom is the Union Jack, also known as the Union Flag.

The design of the Union Jack dates back to the Act of Union 1801 which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland (previously in pe ...

be redesigned to include a symbol representing Wales, as it is the only nation in the United Kingdom not represented in the flag.

The daffodil is a more recent development, becoming popular during the 19th century. It may have been linked to the leek; the Welsh for daffodil (''cenhinen Bedr'') translates as "St Peter's leek". During the 20th century, the daffodil rose to rival the prominence of the leek as a symbol of Wales. Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

ensured that the daffodil had a place in the investiture of Edward, Prince of Wales.

The traditional Welsh costume

The Welsh traditional costume ( cy, Gwisg Gymreig draddodiadol) was worn by rural women in Wales. It was identified as being different from that worn by the rural women of England by many of the English visitors who toured Wales during the late ...

and Welsh hat were well known during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Princess Alexandrina Victoria (later Queen Victoria) had a hat made for her when she visited Wales in 1832. The hat was popularised by Sydney Curnow Vosper's 1908 painting '' Salem'', but by then its use had declined.

Welsh people may sometimes engage in gentle self-mockery and claim the sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus ''Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated s ...

as a national emblem

A national emblem is an emblem or seal that is reserved for use by a nation state or multi-national state as a symbol of that nation. Many nations have a seal or emblem in addition to a national flag and a national coat of arms. Other national sy ...

, due to the 3 million people in the country

A country is a distinct part of the world, such as a state, nation, or other political entity. It may be a sovereign state or make up one part of a larger state. For example, the country of Japan is an independent, sovereign state, while the ...

being vastly outnumbered by some 10 million sheep and the nation's reliance on sheep farming

Sheep farming or sheep husbandry is the raising and breeding of domestic sheep. It is a branch of animal husbandry. Sheep are raised principally for their meat (lamb and mutton), milk (sheep's milk), and fiber (wool). They also yield sheepskin an ...

. The importance of sheep farming led to the creation of the Welsh sheepdog

The Welsh Sheepdog ( cy, Ci Defaid Cymreig, ) is a Welsh breed of herding dog of medium size from Wales.

Like other types of working dog, Welsh Sheepdogs are normally bred for their herding abilities rather than appearance, and so they are gene ...

.

Welsh lovespoons are traditionally crafted wooden spoons which a suitor would give to his beloved. The more intricacies of the design served a dual purpose, as it demonstrated the depth of their feelings to the beloved, and their crafting abilities (and therefore potential to generate income to look after the family) to their potential suitor's family. The earliest known dated lovespoon from Wales, displayed in the St Fagans National History Museum near Cardiff. It is believed to have been crafted in 1667, although the tradition is believed to date back long before that.

Language

The two main languages of Wales areWelsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

and English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

Throughout the centuries, the Welsh language has been a central factor in the concept of Wales as a nation. Undoubtedly the strongest of the Celtic languages, figures released by the Office of National Statistics taken from the 2011 census, show that Welsh is spoken by 19% of the population.

Religion

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

occupation, the dominant religion in Wales was a pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

one, led by the druids

A druid was a member of the high-ranking class in ancient Celtic cultures. Druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no written accounts. Whi ...

. Little is known about the traditions and ceremonies, but Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

, whose claims were sometimes exaggerated, stated that they performed human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherein ...

: he says that in AD 61, an altar on Anglesey

Anglesey (; cy, (Ynys) Môn ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms a principal area known as the Isle of Anglesey, that includes Holy Island across the narrow Cymyran Strait and some islets and skerries. Anglesey island ...

was found to be "drenched with the blood of their prisoners". Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

was introduced to Wales through the Romans, and after they abandoned the British Isles, it survived in South East Wales at Hentland

Hentland is a hamlet and civil parish about north-west of Ross-on-Wye in Herefordshire, England.

The small hamlet settlement of Hentland at the east of the parish contains the parish church of St Dubricius. The civil parish, bounded on its eas ...

. In the 6th century, this was home to Dubricius

Dubricius or Dubric ( cy, Dyfrig; Norman-French: ''Devereux''; c. 465 – c. 550) was a 6th-century British ecclesiastic venerated as a saint. He was the evangelist of Ergyng ( cy, Erging) (later Archenfield, Herefordshire) and much ...

, the first Celtic saint.

The largest religion in modern Wales is Christianity, with almost 58% of the population describing themselves as Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

in the 2011 census. The Presbyterian Church of Wales

The Presbyterian Church of Wales ( cy, Eglwys Bresbyteraidd Cymru), also known as Calvinistic Methodist Church (), is a denomination of Protestant Christianity in Wales.

History

The church was born out of the Welsh Methodist revival and the ...

was for many years the largest denomination; it was born out of the Welsh Methodist revival

The Welsh Methodist revival was an evangelical revival that revitalised Christianity in Wales during the 18th century. Methodist preachers such as Daniel Rowland, William Williams and Howell Harris were heavily influential in the movement. The ...

in the 18th century and seceded from the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

in 1811; The Church in Wales

The Church in Wales ( cy, Yr Eglwys yng Nghymru) is an Anglicanism, Anglican church in Wales, composed of six dioceses.

The Archbishop of Wales does not have a fixed archiepiscopal see, but serves concurrently as one of the six diocesan bishop ...

had an average Sunday attendance of 32,171 in 2012. It forms part of the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and other ...

, and was also part of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, but was disestablished by the British Government in 1920 under the Welsh Church Act 1914

The Welsh Church Act 1914 is an Act of Parliament under which the Church of England was separated and disestablished in Wales and Monmouthshire, leading to the creation of the Church in Wales. The Act had long been demanded by the Nonconformist ...

. Non-Christian religions have relatively few followers in Wales, with Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...

making up 1.5% of the population while Hindus

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

and Buddhists

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

represent 0.3% each in the 2011 census. Over 32% of the population in Wales did not note a religion. Research in 2007 by the Tearfund

Tearfund is an international Christianity, Christian relief and development agency based in Teddington, UK. It currently works in around 50 countries, with a primary focus on supporting those in poverty and providing disaster relief for disadvan ...

organisation showed that Wales had the lowest average church attendance in the UK, with 12% of the population routinely attending.

Holidays

Thepatron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or perso ...

of Wales is Saint David

Saint David ( cy, Dewi Sant; la, Davidus; ) was a Welsh bishop of Mynyw (now St Davids) during the 6th century. He is the patron saint of Wales. David was a native of Wales, and tradition has preserved a relatively large amount of detail ab ...

, ''Dewi Sant'' in Welsh. St. David's Day

Saint David's Day ( cy, Dydd Gŵyl Dewi Sant or ; ), or the Feast of Saint David, is the feast day of Saint David, the patron saint of Wales, and falls on 1 March, the date of Saint David's death in 589 AD. The feast has been regularly celebrat ...

is celebrated on 1 March, which some people argue should be designated a public holiday in Wales. Other days which have been proposed for national public commemorations are 16 September (the day on which Owain Glyndŵr

Owain ap Gruffydd (), commonly known as Owain Glyndŵr or Glyn Dŵr (, anglicised as Owen Glendower), was a Welsh leader, soldier and military commander who led a 15 year long Welsh War of Independence with the aim of ending English rule in Wa ...

's rebellion began) and 11 December (the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd

Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (c. 1223 – 11 December 1282), sometimes written as Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, also known as Llywelyn the Last ( cy, Llywelyn Ein Llyw Olaf, lit=Llywelyn, Our Last Leader), was the native Prince of Wales ( la, Princeps Wall ...

).

The traditional seasonal festivals in Wales are:

* Calan Gaeaf

''Calan Gaeaf'' is the name of the first day of winter in Wales, observed on 1 November.Davies (2008), pg 107. The night before is ''Nos Galan Gaeaf'' or ''Noson Galan Gaeaf'', an ''Ysbrydnos'' ("spirit night"Jones (2020), pg 161.) when spirits ...

(a Hallowe'en

Halloween or Hallowe'en (less commonly known as Allhalloween, All Hallows' Eve, or All Saints' Eve) is a celebration observed in many countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Saints' Day. It begins the observanc ...

or Samhain

Samhain ( , , , ; gv, Sauin ) is a Gaelic festival on 1 NovemberÓ hÓgáin, Dáithí. ''Myth Legend and Romance: An Encyclopaedia of the Irish Folk Tradition''. Prentice Hall Press, 1991. p. 402. Quote: "The basic Irish division of the year ...

-type festival on the first day of winter)

* Gŵyl Fair y Canhwyllau

(English: "Mary's Festival of the Candles") is a Welsh name of Candlemas, celebrated on 2 February. It was derived from the pre-Reformation ceremony of blessing the candle

A candle is an ignitable wick embedded in wax, or another flammab ...

(literally Mary's Festival of the Candles, i.e. Candlemas

Candlemas (also spelled Candlemass), also known as the Feast of the Presentation of Jesus Christ, the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, or the Feast of the Holy Encounter, is a Christian holiday commemorating the presentati ...

; also coinciding with Imbolc

Imbolc or Imbolg (), also called Saint Brigid's Day ( ga, Lá Fhéile Bríde; gd, Là Fhèill Brìghde; gv, Laa'l Breeshey), is a Gaelic traditional festival. It marks the beginning of spring, and for Christians it is the feast day of Saint ...

)

* Calan Mai

''Calan Mai'' ( "Calan (first day) of May") or ''Calan Haf'' ( "first day of Summer") is a May Day holiday of Wales held on 1 May. Celebrations start on the evening before, known as May Eve, with bonfires; as with Calan Gaeaf or 1 November, t ...

(May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the spring equinox and summer solstice. Festivities may also be held the night before, known as May Eve. T ...

, and similar to Beltane

Beltane () is the Gaelic May Day festival. Commonly observed on the first of May, the festival falls midway between the spring equinox and summer solstice in the northern hemisphere. The festival name is synonymous with the month marking the ...

)

* Calan Awst

Lammas Day (Anglo-Saxon ''hlaf-mas'', "loaf-mass"), also known as Loaf Mass Day, is a Christian holiday celebrated in some English-speaking countries in the Northern Hemisphere on 1 August. The name originates from the word "loaf" in referenc ...

(1 August, equivalent to Lammas

Lammas Day (Anglo-Saxon ''hlaf-mas'', "loaf-mass"), also known as Loaf Mass Day, is a Christian holiday celebrated in some English-speaking countries in the Northern Hemisphere on 1 August. The name originates from the word "loaf" in reference ...

and Lughnasa)

* Gŵyl Mabsant celebrated by each parish in commemoration of its native saint, often marked by a fair

* Dydd Santes Dwynwen

Saint Dwynwen (; 5th century), sometimes known as Dwyn or Donwen, is the Welsh patron saint of lovers. She is celebrated throughout Wales on 25 January.

History and legend

The original tale has become mixed with elements of folktales ...

, a Welsh equivalent to St Valentine's Day

* Calennig Calennig is a Welsh word meaning "''New Year celebration/gift''", although it literally translates to "the first day of the month", deriving from the Latin word kalends. The English word "Calendar" also has its root in this word.

It is a tradition ...

is a Welsh New Year celebration

Arts

Visual arts

Many works ofCeltic art

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period, as well as the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and styli ...

have been found in Wales. In the Early Medieval

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

period, the Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity ( kw, Kristoneth; cy, Cristnogaeth; gd, Crìosdaidheachd; gv, Credjue Creestee/Creestiaght; ga, Críostaíocht/Críostúlacht; br, Kristeniezh; gl, Cristianismo celta) is a form of Christianity that was common, or held ...

of Wales participated in the Insular art

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from ''insula'', the Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland shared a largely common style dif ...

of the British Isles and a number of illuminated manuscript

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is often supplemented with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers, liturgical services and psalms, the ...

s possibly of Welsh origin survive, of which the 8th century Hereford Gospels and Lichfield Gospels

The Lichfield Gospels (recently more often referred to as the St Chad Gospels, but also known as the Book of Chad, the Gospels of St Chad, the St Teilo Gospels, the Llandeilo Gospels, and variations on these) is an 8th-century Insular Gospel ...

are the most notable. The 11th century Ricemarch Psalter (now in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

) is certainly Welsh, made in St David's

St Davids or St David's ( cy, Tyddewi, , "David's house”) is a city and a community (named St Davids and the Cathedral Close) with a cathedral in Pembrokeshire, Wales, lying on the River Alun. It is the resting place of Saint David, Wa ...

, and shows a late Insular style with unusual Viking influence.

The best of the few Welsh artists of the 16th–18th centuries tended to move elsewhere to work, but in the 18th century the dominance of landscape art

Landscape painting, also known as landscape art, is the depiction of natural scenery such as mountains, valleys, trees, rivers, and forests, especially where the main subject is a wide view—with its elements arranged into a coherent compos ...

in English art

English art is the body of visual arts made in England. England has Europe's earliest and northernmost ice-age cave art. Prehistoric art in England largely corresponds with art made elsewhere in contemporary Britain, but early medieval Anglo-Sax ...

motivated them to stay at home, and brought an influx of artists from outside to paint Welsh scenery. The Welsh painter Richard Wilson (1714–1782) is arguably the first major British landscapist, but rather more notable for Italian scenes than Welsh ones, although he did paint several on visits from London.

It remained difficult for artists relying on the Welsh market to support themselves until well into the 20th century. An

It remained difficult for artists relying on the Welsh market to support themselves until well into the 20th century. An Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the Legislature, legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of ...

in 1854 provided for the establishment of a number of art schools throughout the United Kingdom, and the Cardiff School of Art opened in 1865. Graduates still very often had to leave Wales to work, but Betws-y-Coed

Betws-y-coed (; '' en, prayer house in the wood'') is a village and community in the Conwy valley in Conwy County Borough, Wales, located in the historic county of Caernarfonshire, right on the boundary with Denbighshire, in the Gwydir Forest. ...

became a popular centre for artists, and its artists' colony helped form the Royal Cambrian Academy of Art

The Royal Cambrian Academy of Art (RCA) is a centre of excellence for art in Wales. Its main gallery is located in Conwy and it has over a hundred members.

240px, Plas Mawr, Conwy

Early history

During the 19th century there were numerous attempts ...

in 1881. The sculptor Sir William Goscombe John

Sir William Goscombe John (21 February 1860 – 15 December 1952) was a prolific Welsh sculptor known for his many public memorials. As a sculptor, John developed a distinctive style of his own while respecting classical traditions and forms of ...

made many works for Welsh commissions, although he had settled in London. Christopher Williams, whose subjects were mostly resolutely Welsh, was also based in London. Thomas E. Stephens and Andrew Vicari

Andrew Vicari (born Andrea Antonio Giovanni Vaccari; 20 April 1932 – 3 October 2016) was a Welsh painter working in France, who established a career painting portraits of prominent people. Despite being largely unknown in his own country, ...

had very successful careers as portraitists, based respectively in the United States and France. Sir Frank Brangwyn

Sir Frank William Brangwyn (12 May 1867 – 11 June 1956) was a Welsh artist, painter, watercolourist, printmaker, illustrator, and designer.

Brangwyn was an artistic jack-of-all-trades. As well as paintings and drawings, he produced des ...

was Welsh by origin, but spent little time in Wales.

Perhaps the most famous Welsh painters, Augustus John

Augustus Edwin John (4 January 1878 – 31 October 1961) was a Welsh painter, draughtsman, and etcher. For a time he was considered the most important artist at work in Britain: Virginia Woolf remarked that by 1908 the era of John Singer Sarg ...

and his sister Gwen John

Gwendolen Mary John (22 June 1876 – 18 September 1939) was a Welsh artist who worked in France for most of her career. Her paintings, mainly portraits of anonymous female sitters, are rendered in a range of closely related tones. Although s ...

, mostly lived in London and Paris; however the landscapists Sir Kyffin Williams

Sir John Kyffin Williams, (9 May 1918 – 1 September 2006) was a Welsh landscape painter who lived at Pwllfanogl, Llanfairpwll, on the Island of Anglesey. Williams is widely regarded as the defining artist of Wales during the 20th century.

Pe ...

and Peter Prendergast remained living in Wales for most of their lives, though well in touch with the wider art world. Ceri Richards

Ceri Giraldus Richards (6 June 1903 – 9 November 1971) was a Welsh painter, print-maker and maker of reliefs.

Biography

Richards was born in 1903 in the village of Dunvant, near Swansea, the son of Thomas Coslett Richards and Sarah Ric ...

was very engaged in the Welsh art scene as a teacher in Cardiff, and even after moving to London; he was a figurative painter in international styles including Surrealism

Surrealism is a cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists depicted unnerving, illogical scenes and developed techniques to allow the unconscious mind to express itself. Its aim was, according to l ...

. Various artists have moved to Wales, including Eric Gill

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill, (22 February 1882 – 17 November 1940) was an English sculptor, letter cutter, typeface designer, and printmaker. Although the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' describes Gill as ″the greatest artist-cra ...

, the London-born Welshman David Jones, and the sculptor Jonah Jones

Jonah Jones (born Robert Elliott Jones; December 31, 1909 – April 29, 2000) was a jazz trumpeter who created concise versions of jazz and swing and jazz standards that appealed to a mass audience. In the jazz community, he is known for his w ...

. The Kardomah Gang

The Kardomah Gang,The Kardomah Boys, or Kardomah Group was a group of bohemian friends – artists, musicians, poets and writers – who, in the 1930s, frequented the Kardomah Café in Castle Street, Swansea, Wales.

Members of the Gang ...

was an intellectual circle centred on the poet Dylan Thomas

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer whose works include the poems "Do not go gentle into that good night" and "And death shall have no dominion", as well as the "play for voices" ''Under ...

and poet and artist Vernon Watkins

Vernon Phillips Watkins (27 June 1906 – 8 October 1967) was a Welsh poet and translator. His headmaster at Repton was Geoffrey Fisher, who became Archbishop of Canterbury. Despite his parents being Nonconformists, Watkins' school experienc ...

in Swansea, which also included the painter Alfred Janes

Alfred George Janes (30 June 1911 – 3 February 1999) was a Welsh artist, who worked in Swansea and Croydon. He experimented with many forms, but is best known for his meticulous still lifes and portraits.

He is also remembered as one of The K ...

.

Ceramics

Amgueddfa Cymru houses Welsh pottery made in Swansea and Llanelli between 1764 and 1922, in addition to porcelain made at Swansea and Nantgarw between 1813 and 1826. Several further sites can be identified through their place names, for example Pwllcrochan (a hamlet near Milford Haven estuary inPembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; cy, Sir Benfro ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county in the South West Wales, south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and the rest by sea. The count ...

), which translates to Crock Pool, and archaeology has also revealed former kiln

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, a type of oven, that produces temperatures sufficient to complete some process, such as hardening, drying, or chemical changes. Kilns have been used for millennia to turn objects made from clay int ...

sites across the country. These were often located near clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

beds, for ease of resource gathering. Buckley

Buckley may refer to:

Businesses and organizations

* Buckley's, a Canadian pharmaceutical corporation

* Buckley Aircraft, an American aircraft manufacturer

* Buckley Broadcasting, an American broadcasting company

* Buckley School (California), ...

and Ewenny

Ewenny ( cy, Ewenni) is a village and community (parish) on the River Ewenny in the Vale of Glamorgan, Wales.

Over the years the village has grown into the neighbouring village of Corntown to such an extent that there is no longer a clear boundar ...

became leading areas of pottery production in Wales during the 17th and 18th centuries; these are applied as generic terms to different potters within those areas during this period. South Wales had several notable potteries during that same period, an early exponent being the Cambrian Pottery

The Cambrian Pottery was founded in 1764 by William Coles in Swansea, Glamorganshire, Wales. In 1790, John Coles, son of the founder, went into partnership with George Haynes, who introduced new business strategies based on the ideas of Josiah ...

(1764–1870, also known as "Swansea

Swansea (; cy, Abertawe ) is a coastal city and the second-largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Swansea ( cy, links=no, Dinas a Sir Abertawe).

The city is the twenty-fifth largest in ...

pottery"). The works from Cambrian attempted to imitate those of Wedgwood

Wedgwood is an English fine china, porcelain and luxury accessories manufacturer that was founded on 1 May 1759 by the potter and entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood and was first incorporated in 1895 as Josiah Wedgwood and Sons Ltd. It was rapid ...

. Nantgarw Pottery

The Nantgarw China Works was a porcelain factory, later making other types of pottery, located in Nantgarw on the eastern bank of the Glamorganshire Canal, north of Cardiff in the River Taff valley, Glamorganshire, Wales.

The factory made porcel ...

, near Cardiff, was in operation from 1813 to 1823 making fine porcelain

Porcelain () is a ceramic material made by heating substances, generally including materials such as kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arises mainl ...

. Llanelly Pottery was the last surviving major pottery works in South Wales when it closed in 1922.

Literature

Theatre

Theatrical performances are thought to have begun after the Roman invasion of Britain. There are remains of aRoman amphitheatre

Roman amphitheatres are theatres – large, circular or oval open-air venues with raised seating – built by the ancient Romans. They were used for events such as gladiator combats, '' venationes'' (animal slayings) and executions. About 230 Ro ...

at Caerleon

Caerleon (; cy, Caerllion) is a town and community in Newport, Wales. Situated on the River Usk, it lies northeast of Newport city centre, and southeast of Cwmbran. Caerleon is of archaeological importance, being the site of a notable Roman ...

, which would have served the nearby fortress of Isca Augusta

Isca, variously specified as Isca Augusta or Isca Silurum, was the site of a Roman legionary fortress and settlement or ''vicus'', the remains of which lie beneath parts of the present-day suburban village of Caerleon in the north of the city of ...

. Between Roman and modern times, theatre in Wales was limited to performances of travelling players, sometimes in temporary structures. Welsh theatrical groups also performed in England, as did English groups in Wales. The rise of the Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. P ...

in the 17th century and then Methodism during the 18th century caused declines in Welsh theatre as performances were seen as immoral.

Despite this, performances continued on showgrounds, and with a handful of travelling groups of actors. The Savoy Theatre, Monmouth, the oldest theatre still in operation in Wales, was built during the 19th century and originally operated as the Assembly Rooms. Other theatres opened over the following decades, with Cardiff's Theatre Royal opening in 1827. After a fire, a replacement Theatre Royal opened in 1878. Competition for theatres led to further buildings being constructed, such as the New Theatre, Cardiff, which opened on 10 December 1906.

Television

Television in the United Kingdom started in 1936 as a public service which was free of advertising, but did not arrive in Wales until the opening of theWenvoe transmitter

The Wenvoe transmitting station, officially known as Arqiva Wenvoe, is the main facility for broadcasting and telecommunications for South Wales and the West Country. It is situated close to the village of Wenvoe in the Vale of Glamorgan, Wales, i ...

in August 1952. Initially all programmes were in the English language, although under the leadership of Welsh director and controller Alun Oldfield-Davies, occasional Welsh language programmes were broadcast during closed periods, replacing the test card

A test card, also known as a test pattern or start-up/closedown test, is a television test signal, typically broadcast at times when the transmitter is active but no program is being broadcast (often at sign-on and sign-off).

Used since the ear ...

. In 1958, responsibility for programming in Wales fell to Television Wales and the West

Television Wales and the West (TWW) was the British Independent Television (commercial television) contractor for a franchise area that initially served South Wales and West of England (franchise awarded 26 October 1956, started transmissions o ...

, although Welsh language broadcasting was mainly served by the Manchester-based Granada

Granada (,, DIN 31635, DIN: ; grc, Ἐλιβύργη, Elibýrgē; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the fo ...

company, producing about an hour a week. On the 1 November 1982, S4C (Sianel Pedwar Cymru) was launched bringing together the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Julie Gardner

Julie Ann Gardner (born 4 June 1969) is a Welsh television producer. Her most prominent work has been serving as executive producer on the 2005 revival of '' Doctor Who'' and its spin-off shows ''Torchwood'' and ''The Sarah Jane Adventures''. ...

, Head of Drama for BBC Wales, to film and produce the 2005 revived version of Doctor Who

''Doctor Who'' is a British science fiction television series broadcast by the BBC since 1963. The series depicts the adventures of a Time Lord called the Doctor, an extraterrestrial being who appears to be human. The Doctor explores the u ...

in Wales is widely seen as a bellwether moment for the industry for the nation. This in turn was followed by the opening of the Roath Lock

BBC Roath Lock Studios is a television production studio that houses BBC drama productions including ''Doctor Who'', '' Casualty'', and . The centre topped out on 20 February 2011 and filming for such productions commenced in autumn of the sam ...

production studios in Cardiff

Cardiff (; cy, Caerdydd ) is the capital and largest city of Wales. It forms a principal area, officially known as the City and County of Cardiff ( cy, Dinas a Sir Caerdydd, links=no), and the city is the eleventh-largest in the United Kingd ...

. Recent English language programmes that have been filmed in Wales include Sherlock and His Dark Materials

''His Dark Materials'' is a trilogy of fantasy novels by Philip Pullman consisting of '' Northern Lights'' (1995; published as ''The Golden Compass'' in North America), ''The Subtle Knife'' (1997), and ''The Amber Spyglass'' (2000). It follows ...

, while other popular series, such as Hinterland

Hinterland is a German word meaning "the land behind" (a city, a port, or similar). Its use in English was first documented by the geographer George Chisholm in his ''Handbook of Commercial Geography'' (1888). Originally the term was associated ...

(''Y Gwyll'') and Keeping Faith

''Keeping Faith'' (1999) is the sixth novel by the bestselling American author Jodi Picoult. The book is about a custody battle involving a seven-year-old girl, Faith White, who may be seeing God.

Plot summary

When Mariah White catches her hu ...

(''Un Bore Mercher'') have been filmed in both Welsh and English.

Film

The Cinema of Wales comprises the art of film and creative movies made in Wales or by Welsh filmmakers either locally or abroad. Welsh cinema began in the late-19th century, led by Welsh-based directorWilliam Haggar

William Haggar (10 March 1851 – 4 February 1925) was a British pioneer of the cinema industry. Beginning his career as a travelling entertainer, Haggar, whose large family formed his theatre company, later bought a Bioscope show and earned his ...

. Wales continued to produce film of varying quality throughout the 20th century, in both the Welsh and English languages, though indigenous production was curtailed through a lack of infrastructure and finance, which prevented the growth of the industry nationally. Despite this, Wales has been represented in all fields of the film making process, producing actors and directors of note.

Music

left, The Cardiff Arms Park male voice choir Wales is often referred to as "the land of song", and is notable for its harpists, male choirs, and solo artists. The principal Welsh festival of music and poetry is the annual ''

Wales is often referred to as "the land of song", and is notable for its harpists, male choirs, and solo artists. The principal Welsh festival of music and poetry is the annual ''National Eisteddfod

The National Eisteddfod of Wales (Welsh: ') is the largest of several eisteddfodau that are held annually, mostly in Wales. Its eight days of competitions and performances are considered the largest music and poetry festival in Europe. Competitors ...

''. The ''Llangollen International Eisteddfod

The Llangollen International Musical Eisteddfod is a music festival which takes place every year during the second week of July in Llangollen, North Wales. It is one of several large annual Eisteddfodau in Wales. Singers and dancers from around ...

'' echoes the National Eisteddfod but provides an opportunity for the singers and musicians of the world to perform. Traditional music and dance in Wales is supported by many societies. The Welsh Folk Song Society has published a number of collections of songs and tunes.

Male choirs (sometimes called male voice choirs), which emerged in the 19th century, have remained a lasting tradition in Wales. Originally these choirs were formed as the tenor and bass sections of chapel choirs, and embraced the popular secular hymns of the day. Many of the historic Welsh choirs survive, singing a mixture of traditional and popular songs. Traditional instruments of Wales include ''telyn deires'' (triple harp

The triple harp is a type of multi-course harp employing three parallel rows of strings instead of the more common single row. One common version is the Welsh triple harp (Welsh: ''telyn deires''), used today mainly among players of traditional W ...

), fiddle

A fiddle is a bowed string musical instrument, most often a violin. It is a colloquial term for the violin, used by players in all genres, including classical music. Although in many cases violins and fiddles are essentially synonymous, th ...

, crwth

The crwth (, also called a crowd or rote or crotta) is a bowed lyre, a type of stringed instrument, associated particularly with Welsh music, now archaic but once widely played in Europe. Four historical examples have survived and are to be foun ...

, ''pibgorn'' (hornpipe) and other instruments. The Cerdd Dant

' (, or ') is the art of vocal improvisation over a given melody in Welsh musical tradition. It is an important competition in . The singer or (small) choir sings a counter melody over a harp melody.

History

is a unique tradition of singing ly ...

Society promotes its specific singing art primarily through an annual one-day festival. The BBC National Orchestra of Wales

The BBC National Orchestra of Wales (BBC NOW) ( cy, Cerddorfa Genedlaethol Gymreig y BBC) is a Welsh symphony orchestra and one of the BBC's five professional radio orchestras. The BBC NOW is the only professional symphony orchestra organisatio ...

performs in Wales and internationally. The Welsh National Opera

Welsh National Opera (WNO) ( cy, Opera Cenedlaethol Cymru) is an opera company based in Cardiff, Wales; it gave its first performances in 1946. It began as a mainly amateur body and transformed into an all-professional ensemble by 1973. In its ...

is based at the Wales Millennium Centre

Wales Millennium Centre ( cy, Canolfan Mileniwm Cymru) is an arts centre located in the Cardiff Bay area of Cardiff, Wales. The site covers a total area of . Phase 1 of the building was opened during the weekend of the 26–28 November 2004 an ...

in Cardiff Bay

Cardiff Bay ( cy, Bae Caerdydd; historically Tiger Bay; colloquially "The Bay") is an area and freshwater lake in Cardiff, Wales. The site of a former tidal bay and estuary, it serves as the river mouth of the River Taff and Ely. The body of w ...

, while the National Youth Orchestra of Wales

The National Youth Orchestra of Wales (NYOW, cy, Cerddorfa Genedlaethol Ieuenctid Cymru) is the national youth orchestra of Wales, based in Cardiff. Founded in 1945, it is the longest-standing national youth orchestra in the world.

Organisat ...

was the first of its type in the world.

Badfinger

Badfinger were a Welsh rock band formed in Swansea, who were active from the 1960s to the 1980s. Their best-known lineup consisted of Pete Ham (vocals, guitar), Mike Gibbins (drums), Tom Evans (bass), and Joey Molland (guitar). They are recog ...

and singers including Sir Tom Jones

Sir Thomas Jones Woodward (born 7 June 1940), known professionally as Tom Jones, is a Welsh singer. His career began with a string of top-ten hits in the mid-1960s. He has toured regularly, with appearances in Las Vegas (1967–2011). Jones's ...

, Dame Shirley Bassey

Dame Shirley Veronica Bassey (; born 8 January 1937) is a Welsh singer. Best known for her career longevity, powerful voice and recording the theme songs to three James Bond films, Bassey is widely regarded as one of the most popular vocalists ...

and Mary Hopkin

Mary Hopkin (born 3 May 1950), credited on some recordings as Mary Visconti from her marriage to Tony Visconti, is a Welsh singer-songwriter best known for her 1968 UK number 1 single "Those Were the Days". She was one of the first artists ...

. By the 1980s, indie pop

Indie pop (also typeset as indie-pop or indiepop) is a music genre and subculture that combines guitar pop with DIY ethic in opposition to the style and tone of mainstream pop music. It originated from British post-punk in the late 1970s and sub ...

and alternative rock

Alternative rock, or alt-rock, is a category of rock music that emerged from the independent music underground of the 1970s and became widely popular in the 1990s. "Alternative" refers to the genre's distinction from Popular culture, mainstre ...

bands such as The Alarm

The Alarm are a Welsh rock band that formed in Rhyl, Wales, in 1981. Initially formed as a punk band, the Toilets, in 1977, under lead vocalist Mike Peters, the band soon embraced arena rock and included marked influences from Welsh languag ...

, The Pooh Sticks

The Pooh Sticks were a Welsh indie pop band from Swansea, Wales, primarily recording between 1988 and 1995. They were notable for their jangly melodiousness and lyrics gently mocking the indie scene of the time, such as on "On Tape", "Indiepop ...

and The Darling Buds

The Darling Buds are an alternative rock band from Newport, South Wales. The band formed in 1986 and were named after the H. E. Bates novel '' The Darling Buds of May'' – a title taken in turn, from the third line of Shakespeare's Sonnet 18 ...

were popular in their genres. But the wider view at the time was that the wider Welsh music scene was stagnant, as the more popular musicians from Wales were from earlier eras.

In the 1990s, in England, the Britpop

Britpop was a mid-1990s British-based music culture movement that emphasised Britishness. It produced brighter, catchier alternative rock, partly in reaction to the popularity of the darker lyrical themes of the US-led grunge music and to the ...

scene was emerging, while in Wales, bands such as Y Cyrff

(1983–1991; The Bodies) was a Welsh language indie band in the 1980s, initially formed at the Ysgol Dyffryn Conwy secondary school in Llanrwst, Conwy. The original line-up consisted of Barry Cawley (bass), Emyr Davies (vocals), Dylan Hughes ...

and Ffa Coffi Pawb began to sing in English, starting a culture that would lead to the creation of Catatonia

Catatonia is a complex neuropsychiatric behavioral syndrome that is characterized by abnormal movements, immobility, abnormal behaviors, and withdrawal. The onset of catatonia can be acute or subtle and symptoms can wax, wane, or change during ...

and the Super Furry Animals

Super Furry Animals are a Welsh rock band formed in Cardiff in 1993. For the duration of their professional career, the band consisted of Gruff Rhys (lead vocals, guitar), Huw Bunford (lead guitar, vocals), Guto Pryce (bass guitar), Cian Ciaran ...

. The influence of the 80s bands and the emergence of a Welsh language and dual language music scene locally in Wales led to a dramatic shift in opinion across the United Kingdom as the "Cool Cymru

Cool Cymru ( cy, Cŵl Cymru) was a Welsh cultural movement in music and independent film in the 1990s and 2000s, led by the popularity of bands such as Stereophonics, Gorky's Zygotic Mynci, Manic Street Preachers, Catatonia and Super Furry A ...

" bands of the period emerged. The leading Welsh band during this period was the Manic Street Preachers

Manic Street Preachers, also known simply as the Manics, are a Welsh Rock music, rock band formed in Blackwood, Caerphilly, Blackwood in 1986. The band consists of cousins James Dean Bradfield (lead vocals, lead guitar) and Sean Moore (musician ...

, whose 1996 album '' Everything Must Go'' has been listed among the greatest albums of all time.

Some of those bands have had ongoing success, while the general popularity of Welsh music during this period led to a resurgence of singers such as Tom Jones with his album '' Reload''. It was his first non-compilation number one album since 1968's ''Delilah

Delilah ( ; , meaning "delicate";Gesenius's ''Hebrew-Chaldee Lexicon'' ar, دليلة, Dalīlah; grc, label=Greek, Δαλιδά, Dalidá) is a woman mentioned in the sixteenth chapter of the Book of Judges in the Hebrew Bible. She is loved b ...

''. Meanwhile, Shirley Bassey reached the top 20 once more in the UK Charts with her collaboration with the Propellerheads

Propellerheads were an English electronic music duo, formed in 1995 in Bath and consisting of Will White and Alex Gifford.

History

Their first release was an EP named ''Dive!'', released in 1996 through the independent label Wall of Sound. ...

on the single " History Repeating". They also introduced new acts, such as Catatonia's Owen Powell

Owen Powell (born 1967) is a Welsh guitarist. He played in the Welsh rock band Catatonia from 1995 until the band disbanded in 2001.

Career

Catatonia

Powell joined Catatonia in 1995 as a second guitarist. He went on to write for the band, includ ...

working with Duffy during her early period. Moving into the 21st century, Bullet For My Valentine were named the Best British Band at the Kerrang! Awards

The Kerrang! Awards are an annual music awards show in the United Kingdom, founded by the music magazine ''Kerrang!'' and focusing primarily on rock music. The annual awards features performances by prominent artists, and some of the awards of mo ...

for three years running. Other successful bands from this period include Funeral For A Friend

Funeral for a Friend are a Welsh post-hardcore band from Bridgend, formed in 2001 and currently consists of Matthew Davies-Kreye (lead vocals), Kris Coombs-Roberts (guitar, backing vocals), Gavin Burrough (guitar, backing vocals), Darran Smith ...

, and Lostprophets

Lostprophets (stylised as lostprophets) were a Welsh rock band from Pontypridd, formed in 1997 by singer and lyricist Ian Watkins and guitarist Lee Gaze. The band was founded after their former band Fleshbind broke up. They later recruited Mike ...

.

Media

Sport

upRugby Union action from Wales vs. England in 2006 Over fiftynational governing bodies

A sports governing body is a sports organization that has a regulatory or sanctioning function.

Sports governing bodies come in various forms and have a variety of regulatory functions. Examples of this can include disciplinary action for rule ...

regulate and organise their sports in Wales. Most of those involved in competitive sports select, organise and manage individuals or teams to represent their country at international events or fixtures against other countries. Wales is represented at major world sporting events such as the FIFA World Cup

The FIFA World Cup, often simply called the World Cup, is an international association football competition contested by the senior men's national teams of the members of the ' ( FIFA), the sport's global governing body. The tournament ha ...

, the Rugby World Cup

The Rugby World Cup is a men's rugby union tournament contested every four years between the top international teams. The tournament is administered by World Rugby, the sport's international governing body. The winners are awarded the Webb E ...

and the Commonwealth Games