Walter Munk on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Walter Heinrich Munk (October 19, 1917 – February 8, 2019) was an American physical oceanographer. He was one of the first scientists to bring statistical methods to the analysis of oceanographic data. His work won awards including the

In 1957, Munk and

In 1957, Munk and

Starting in the late 1950s, Munk returned to the study of

Starting in the late 1950s, Munk returned to the study of

Beginning in 1975, Munk and Carl Wunsch of the

Beginning in 1975, Munk and Carl Wunsch of the

Munk was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1956, the

Munk was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1956, the  Two marine species have been named after Munk. One is ''Sirsoe munki'', a deep-sea worm. The other is '' Mobula munkiana'', also known as Munk's devil ray, a small relative of giant manta rays living in huge schools, and with a remarkable ability to leap far out of the water. A 2017 documentary, '' Spirit of Discovery (Documentary)'', follows Munk in an expedition with the discoverer, his former student Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara, to

Two marine species have been named after Munk. One is ''Sirsoe munki'', a deep-sea worm. The other is '' Mobula munkiana'', also known as Munk's devil ray, a small relative of giant manta rays living in huge schools, and with a remarkable ability to leap far out of the water. A 2017 documentary, '' Spirit of Discovery (Documentary)'', follows Munk in an expedition with the discoverer, his former student Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara, to

Oral History interview transcript with Walter Munk on 30 June 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives

*

Oral history interview transcript with Walter Munk on 2 July 2004, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library & Archives

* (1967) – a documentary showcasing Munk's research on waves generated by Antarctic storms. The film documents Munk's collaboration as they track storm-driven waves from Antarctica across the Pacific Ocean to Alaska. The film features scenes of early digital equipment in use in field experiments with Munk's commentary on how unsure they were about using such new technology in remote locations. * (1994) – a television program on the work and life of Walter Munk produced by the University of California. * (2004) – a seminar on global sea level and climate change by Walter Munk. (YouTube link)

(2010) – Munk's Crafoord Prize Lecture

Spirit of Discovery

(2017) – a documentary showcasing Munk as he goes in search of ''Mobula munkiana'' a species that bears his name.

A Conversation with Walter Munk

(2019) – Carl Wunsch interviews Walter Munk about his life, career, and scientific events and people during his life on the occasion of his 100th birthday in 2017.

The Heard Island Feasibility Test

Tributes to Walter Munk

(Scripps) {{DEFAULTSORT:Munk, Walter 1917 births 2019 deaths People from La Jolla, San Diego Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences California Institute of Technology alumni Columbia University alumni Foreign Members of the Royal Society Foreign Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences Jewish American scientists Kyoto laureates in Basic Sciences National Medal of Science laureates American centenarians American oceanographers Fluid dynamicists Scripps Institution of Oceanography faculty Scripps Institution of Oceanography alumni Recipients of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society American people of Austrian-Jewish descent Austrian Jews Scientists from Vienna Austrian centenarians Men centenarians University of California, San Diego faculty Members of JASON (advisory group) Founding members of the World Cultural Council Sverdrup Gold Medal Award Recipients Writers from San Diego Writers from Vienna United States Army soldiers 21st-century American Jews Austrian emigrants to the United States Members of the American Philosophical Society

National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social scienc ...

, the Kyoto Prize

The is Japan's highest private award for lifetime achievement in the arts and sciences. It is given not only to those that are top representatives of their own respective fields, but to "those who have contributed significantly to the scientific, ...

, and induction to the French Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

.

Munk worked on a wide range of topics, including surface waves, geophysical implications of variations in the Earth's rotation, tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

s, internal wave

Internal waves are gravity waves that oscillate within a fluid medium, rather than on its surface. To exist, the fluid must be stratified: the density must change (continuously or discontinuously) with depth/height due to changes, for example, in ...

s, deep-ocean drilling into the sea floor, acoustical measurements of ocean properties, sea level rise

Globally, sea levels are rising due to human-caused climate change. Between 1901 and 2018, the globally averaged sea level rose by , or 1–2 mm per year on average.IPCC, 2019Summary for Policymakers InIPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cry ...

, and climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

. Beginning in 1975, Munk and Carl Wunsch developed ocean acoustic tomography, to exploit the ease with which sound travels in the ocean and use acoustical signals for measurement of broad-scale temperature and current. In a 1991 experiment, Munk and his collaborators investigated the ability of underwater sound to propagate from the Southern Indian Ocean across all ocean basins. The aim was to measure global ocean temperature. The experiment was criticized by environmental groups, who expected that the loud acoustic signals would adversely affect marine life. Munk continued to develop and advocate for acoustical measurements of the ocean throughout his career.

Munk's career began before the outbreak of World War II and ended nearly 80 years later with his death in 2019. The war interrupted his doctoral studies at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (Scripps), and led to his participation in U.S. military research efforts. Munk and his doctoral advisor Harald Sverdrup developed methods for forecasting wave conditions which were used in support of beach landings in all theaters of the war. He was involved with oceanographic programs during the atomic bomb tests in Bikini Atoll. For most of his career, he was a professor of geophysics

Geophysics () is a subject of natural science concerned with the physical processes and physical properties of the Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis. The term ''geophysics'' so ...

at Scripps at the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Merced, Riverside, San Diego, San Franci ...

in La Jolla

La Jolla ( , ) is a hilly, seaside neighborhood within the city of San Diego, California, United States, occupying of curving coastline along the Pacific Ocean. The population reported in the 2010 census was 46,781.

La Jolla is surrounded on ...

. Additionally, Munk and his wife Judy were active in developing the Scripps campus and integrating it with the new University of California, San Diego

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego or colloquially, UCSD) is a public land-grant research university in San Diego, California. Established in 1960 near the pre-existing Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego is t ...

. Munk's career included a number of prestigious positions, including being a member of the JASON

Jason ( ; ) was an ancient Greek mythological hero and leader of the Argonauts, whose quest for the Golden Fleece featured in Greek literature. He was the son of Aeson, the rightful king of Iolcos. He was married to the sorceress Medea. He ...

think tank

A think tank, or policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, military, technology, and culture. Most think tanks are non-governmenta ...

, and holding the Secretary of the Navy/Chief of Naval Operations Oceanography Chair.

Early life and education

In 1917, Munk was born to aJewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

family in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

. His father, Dr. Hans Munk, and his mother, Rega Brunner, divorced when he was ten years old. His maternal grandfather was Lucian Brunner (1850–1914), a prominent banker and Austrian politician. His stepfather, Dr. Rudolf Engelsberg, was head of the salt mine monopoly of the Austrian government and a member of the Austrian governments of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss

Engelbert Dollfuß (alternatively: ''Dolfuss'', ; 4 October 1892 – 25 July 1934) was an Austrian clerical fascist politician who served as Chancellor of Austria between 1932 and 1934. Having served as Minister for Forests and Agriculture, he ...

and Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg

Kurt Alois Josef Johann von Schuschnigg (; 14 December 1897 – 18 November 1977) was an Austrian Fatherland Front politician who was the Chancellor of the Federal State of Austria from the 1934 assassination of his predecessor Engelbert Doll ...

.

In 1932, Munk was performing poorly in school because he was spending too much time skiing, so his family sent him from Austria to a boys' preparatory school in upper New York state. His family envisioned a career for him in finance with a New York bank connected to the family business. He worked at the family's banking firm for three years and studied at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

.

Munk hated banking. In 1937, he left the firm to attend the California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

(Caltech) in Pasadena

Pasadena ( ) is a city in Los Angeles County, California, northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is the most populous city and the primary cultural center of the San Gabriel Valley. Old Pasadena is the city's original commercial district.

...

. While at Caltech, he took a summer job in 1939 at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (Scripps) in La Jolla, California. Munk earned a B.S.

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University ...

in applied physics in 1939 and an M.S. in geophysics (under Beno Gutenberg

Beno Gutenberg (; June 4, 1889 – January 25, 1960) was a German-American seismologist who made several important contributions to the science. He was a colleague and mentor of Charles Francis Richter at the California Institute of Technolog ...

) in 1940 at Caltech. The master's degree work was based on oceanographic data collected in the Gulf of California

The Gulf of California ( es, Golfo de California), also known as the Sea of Cortés (''Mar de Cortés'') or Sea of Cortez, or less commonly as the Vermilion Sea (''Mar Bermejo''), is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean that separates the Baja C ...

by the Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

oceanographer Harald Sverdrup, then director of Scripps.

In 1939, Munk asked Sverdrup to take him on as a doctoral student. Sverdrup agreed, although Munk recalled him saying "I can't think of a single job that's going to become available in the next ten years in oceanography". Munk's studies were interrupted by the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. He completed his doctoral degree in oceanography at Scripps under the University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the California S ...

in 1947. He wrote it in three weeks and it is the "shortest Scripps dissertation on record." He later realized that its principal conclusion is wrong.

Wartime activities

In 1940, Munk enlisted theU.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

. This was unusual for a student at Scripps: all the others joined the U.S. Naval Reserve. After serving 18 months in Field Artillery and the Ski Troops

Ski warfare is the use of ski-equipped troops in war.

History

Early

Ski warfare is first recorded by the Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus in the 13th century. During the Battle of Oslo in 1161, Norwegian troops used skis for reconnoi ...

, he was discharged at the request of Sverdrup and Roger Revelle so he could undertake defense-related research at Scripps. In December 1941, a week before the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

, he joined several of his colleagues from Scripps at the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

Radio and Sound Laboratory

Radio is the technology of signaling and telecommunication, communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device ...

. For six years they developed methods related to antisubmarine

An anti-submarine weapon (ASW) is any one of a number of devices that are intended to act against a submarine and its crew, to destroy (sink) the vessel or reduce its capability as a weapon of war. In its simplest sense, an anti-submarine weapo ...

and amphibious warfare. This research involved marine acoustics, and eventually led to his work on ocean acoustic tomography.

Predicting surf conditions for Allied landings

In 1943, Munk and Sverdrup began looking for a way to predict the heights of ocean surface waves. The Allies were preparing for a landing in North Africa, where two out of every three days the waves are above six feet. Practice beach landings inthe Carolinas

The Carolinas are the U.S. states of North Carolina and South Carolina, considered collectively. They are bordered by Virginia to the north, Tennessee to the west, and Georgia to the southwest. The Atlantic Ocean is to the east.

Combining Nor ...

were suspended when waves reached this height because they were dangerous to people and landing craft. Munk and Sverdrup found an empirical law that related wave height and period to the speed and duration of the wind and the distance over which it blows. The Allies applied this method in the Pacific theater of war and the Normandy invasion on D-Day.

Officials at the time estimated that many lives were saved by these predictions. Munk commented in 2009:

Oceanographic measurements during atomic weapons tests in the Pacific

In 1946, the United States tested two fission nuclear weapons (20 kilotons) atBikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese: , , meaning "coconut place"), sometimes known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 1800s and 1946 is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. After the Seco ...

in the equatorial Pacific in Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

. Munk helped to determine the currents

Currents, Current or The Current may refer to:

Science and technology

* Current (fluid), the flow of a liquid or a gas

** Air current, a flow of air

** Ocean current, a current in the ocean

*** Rip current, a kind of water current

** Current (stre ...

, diffusion, and water exchanges affecting the radiation contamination from the second test, code-named Baker. Six years later he returned to the equatorial Pacific for the 1952 test of the first fusion nuclear weapon (10 megatons) at Eniwetok Atoll, code-named Ivy Mike

Ivy Mike was the codename given to the first full-scale test of a thermonuclear device, in which part of the explosive yield comes from nuclear fusion.

Ivy Mike was detonated on November 1, 1952, by the United States on the island of Elugelab ...

. Roger Revelle, John Isaacs, and Munk had initiated a program for monitoring for the possibility of a large tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater exp ...

generated from the test.

Later association with the military

Munk continued to have a close association with the military in later decades. He was one of the first academics to be funded by the Office of Naval Research, and had his last grant from them when he was 97. In 1968, he became a member ofJASON

Jason ( ; ) was an ancient Greek mythological hero and leader of the Argonauts, whose quest for the Golden Fleece featured in Greek literature. He was the son of Aeson, the rightful king of Iolcos. He was married to the sorceress Medea. He ...

, a panel of scientists who advise the Pentagon, and he continued in that role until the end of his life. He held a Secretary of the Navy/Chief of Naval Operations Oceanography Chair from 1985 until his death in 2019.

Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics

After receiving his doctorate in 1947, Munk was hired by Scripps as an assistant professor of geophysics. He became a full professor there in 1954, but his appointment was at the Institute of Geophysics (IGP) at theUniversity of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the California S ...

(UCLA). In 1955, Munk took a sabbatical at Cambridge, England. His experience at Cambridge led to the idea of starting a new IGP branch at Scripps.

At the time of Munk's return to Scripps, it was still under the administration of UCLA, as it had been since 1938. It became part of the University of California, San Diego

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego or colloquially, UCSD) is a public land-grant research university in San Diego, California. Established in 1960 near the pre-existing Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego is t ...

(UCSD) when that campus was founded in 1958. Revelle, its director at the time, was a primary advocate for establishing the La Jolla campus. At this time Munk was considering offers for new positions at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

and Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

, but Revelle encouraged Munk to remain in La Jolla. Munk's founding of IGP at La Jolla was concurrent with the creation of the UCSD campus.

The IGPP laboratory was built between 1959 and 1963 with funding from the University of California, the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the National Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation (NSF) is an independent agency of the United States government that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. Its medical counterpart is the National ...

, and private foundations. (After planetary physics was added, IGP changed its name to the Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics (IGPP).) The redwood building was designed by architect Lloyd Ruocco, in close consultation with Judith and Walter Munk. The IGPP buildings have become the center of the Scripps campus. Among the early faculty appointments were Carl Eckart, George Backus

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presid ...

, Freeman Gilbert and John Miles. The eminent geophysicist Sir Edward "Teddy" Bullard was a regular visitor to IGPP. In 1971 an endowment of $600,000 was established by Cecil Green to support visiting scholars, now known as Green Scholars. Munk served as director of IGPP/LJ from 1962 to 1982.

In the late 1980s, plans for an expansion of IGPP were developed by Judith and Walter Munk, and Sharyn and John Orcutt, in consultation with a local architect, Fred Liebhardt. The Revelle Laboratory was completed in 1993. At this time the original IGPP building was renamed the Walter and Judith Munk Laboratory for Geophysics. In 1994 the Scripps branch of IGPP was renamed the Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics.

Research

Munk's career in oceanography and geophysics touched on disparate and innovative topics. A pattern of Munk's work was that he would initiate a completely new topic; ask challenging, fundamental questions about the subject and its larger meaning; and then, having created an entirely new sub-field of science, move on to another new topic. As Carl Wunsch, one of Munk's frequent collaborators, commented:Wind-driven gyres

In 1948, Munk took a year's sabbatical to visit Sverdrup inOslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population ...

, Norway on his first Guggenheim Fellowship. He worked on the problem of wind-driven ocean circulation

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of sea water generated by a number of forces acting upon the water, including wind, the Coriolis effect, breaking waves, cabbeling, and temperature and salinity differences. Depth contours, ...

, obtaining the first comprehensive solution for currents based on observed wind patterns. This included two types of friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:

*Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of ...

: horizontal friction between water masses moving at different velocities or between water and the edges of the oceanic basin, and friction from a vertical velocity gradient in the top layer of the ocean (the Ekman layer

The Ekman layer is the layer in a fluid where there is a force balance between pressure gradient force, Coriolis force and turbulent drag. It was first described by Vagn Walfrid Ekman. Ekman layers occur both in the atmosphere and in the ocean ...

). The model predicted the five main ocean gyres (pictured), with rapid, narrow currents in the west flowing towards the poles and broader, slower currents in the east flowing away from the poles. Munk coined the term "ocean gyres," a term now widely used. The currents predicted for the western boundaries (e.g., for the Gulf Stream and the Kuroshio Current

The , also known as the Black or or the is a north-flowing, warm ocean current on the west side of the North Pacific Ocean basin. It was named for the deep blue appearance of its waters. Similar to the Gulf Stream in the North Atlantic, the Ku ...

) were about half of the accepted values at the time, but those only considered the most intense flow and neglected a large return flow. Later estimates agreed well with Munk's predictions.

Rotation of the Earth

In the 1950s, Munk investigated irregularities in the Earth's rotation – changes in the length of day (rate of the Earth's rotation) and changes in the axis of rotation (such as theChandler wobble

The Chandler wobble or Chandler variation of latitude is a small deviation in the Earth's axis of rotation relative to the solid earth, which was discovered by and named after American astronomer Seth Carlo Chandler in 1891. It amounts to change o ...

, which has a period of about 14 months). The latter gives rise to a small tide called the pole tide

Long-period tides are gravitational tides with periods longer than one day, typically with amplitudes of a few centimeters or less.

Long-period tidal constituents with relatively strong forcing include the ''lunar fortnightly'' (Mf) and ''lunar m ...

. Although the scientific community knew of these fluctuations, they did not have adequate explanations for them. With Gordon J. F. MacDonald Gordon James Fraser MacDonald (July 30, 1929 – May 14, 2002) was an American geophysicist and environmental scientist, best known for his principled skepticism regarding continental drift (now called plate tectonics), involvement in the developmen ...

, Munk published ''The Rotation of the Earth: A Geophysical Discussion'' in 1960. This book discusses the effects from a geophysical, rather than astronomical, perspective. It shows that short-term variations are caused by movement in the atmosphere, ocean, underground water, and interior of the Earth, including tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

s in the ocean and solid Earth. Over longer times (a century or more), the largest influence is the tidal acceleration

Tidal acceleration is an effect of the tidal forces between an orbiting natural satellite (e.g. the Moon) and the primary planet that it orbits (e.g. Earth). The acceleration causes a gradual recession of a satellite in a prograde orbit away f ...

that causes the Moon to move away from the Earth at about four centimeters per year. This gradually slows Earth's rotation, so that over 500 million years the length of day has increased from 21 hours to 24. The monograph remains a standard reference.

Project Mohole

In 1957, Munk and

In 1957, Munk and Harry Hess

Harry Hess (born July 5, 1968) is a Canadian record producer, singer and guitarist best known as the frontman for the Canadian hard rock band Harem Scarem.

Hess has used his recording studio (Vespa Music Group) to work with many famous acts, ...

suggested the idea behind Project Mohole

Project Mohole was an attempt in the early 1960s to drill through the Earth's crust to obtain samples of the Mohorovičić discontinuity, or Moho, the boundary between the Earth's crust and mantle. The project was intended to provide an eart ...

: to drill into the Mohorovičić discontinuity and obtain a sample of the Earth's mantle. While such a project was not feasible on land, drilling in the open ocean would be more feasible, because the mantle is much closer to the sea floor. Initially led by the informal group of scientists known as the American Miscellaneous Society (AMSOC), a group that included Hess, Maurice Ewing

William Maurice "Doc" Ewing (May 12, 1906 – May 4, 1974) was an American geophysicist and oceanographer.

Ewing has been described as a pioneering geophysicist who worked on the research of seismic reflection and refraction in ocean basi ...

, and Roger Revelle, the project was eventually taken over by the National Science Foundation. Initial test drillings into the sea floor led by Willard Bascom occurred off Guadalupe Island

Guadalupe Island ( es, Isla Guadalupe, link=no) is a volcanic island located off the western coast of Mexico's Baja California Peninsula and about southwest of the city of Ensenada in the state of Baja California, in the Pacific Ocean. The ...

, Mexico in March and April 1961. However, the project was mismanaged and grew in expense after the construction company Brown and Root

KBR, Inc. (formerly Kellogg Brown & Root) is a U.S. based company operating in fields of science, technology and engineering. KBR works in various markets including aerospace, defense, industrial and intelligence. After Halliburton acquired Dress ...

won the contract to continue the effort. Toward the end of 1966, Congress discontinued the project. While Project Mohole was not successful, the idea and its innovative initial phase directly led to the successful NSF Deep Sea Drilling Program

The Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) was an ocean drilling project operated from 1968 to 1983. The program was a success, as evidenced by the data and publications that have resulted from it. The data are now hosted by Texas A&M University, alth ...

for obtaining sediment cores.

Ocean swell

Starting in the late 1950s, Munk returned to the study of

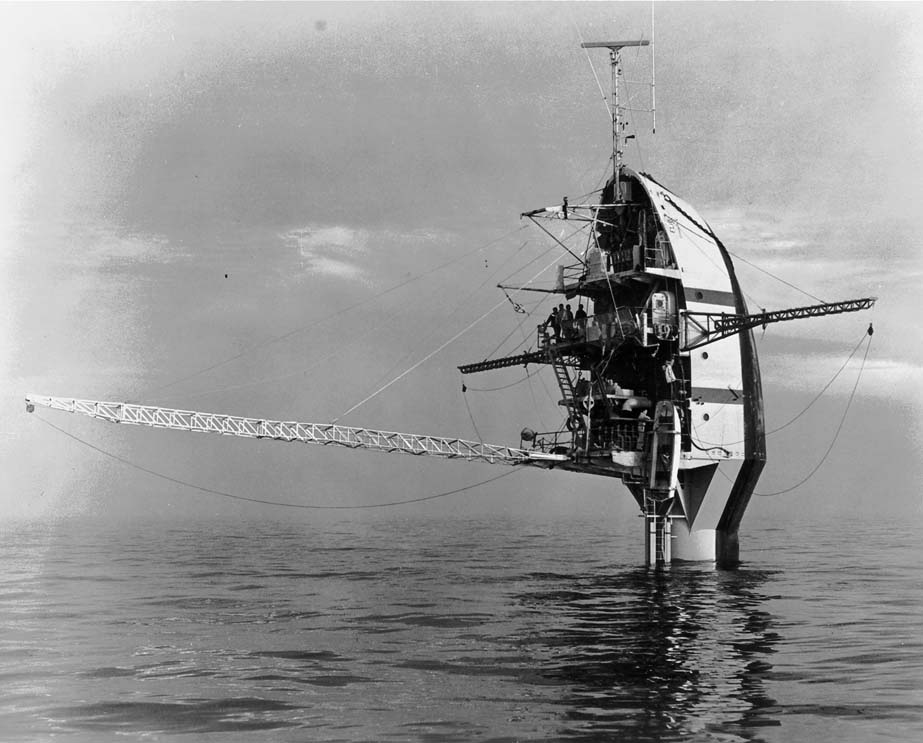

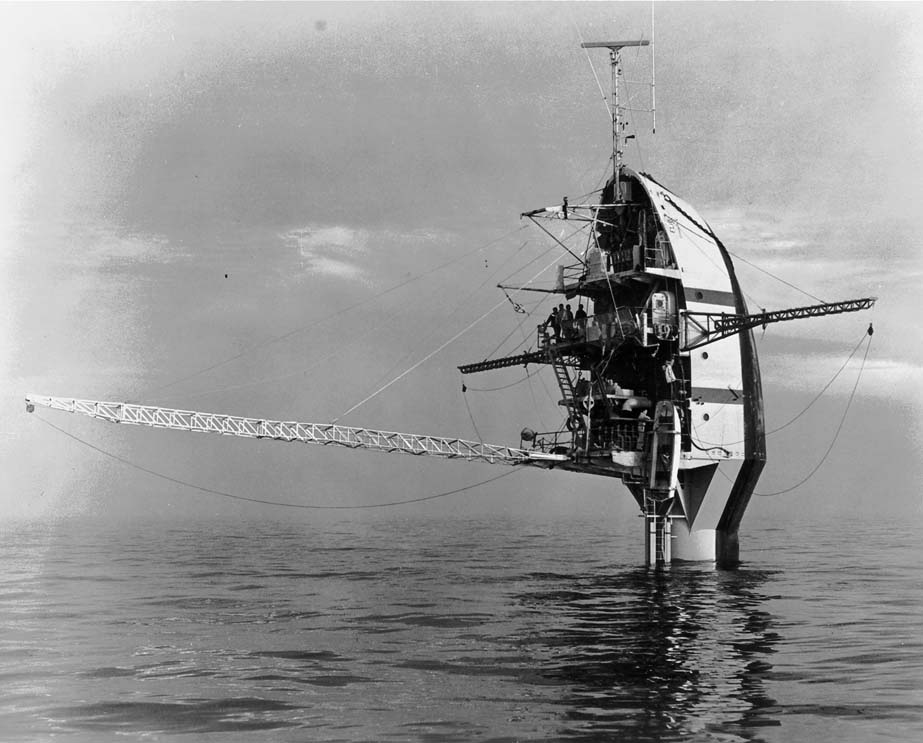

Starting in the late 1950s, Munk returned to the study of ocean waves

In fluid dynamics, a wind wave, water wave, or wind-generated water wave, is a surface wave that occurs on the free surface of bodies of water as a result from the wind blowing over the water surface. The contact distance in the direction o ...

. Thanks to his acquaintance with John Tukey, he pioneered the use of power spectra in describing wave behavior. This work culminated with an expedition that he led in 1963 called "Waves Across the Pacific" to observe waves generated by storms in the Southern Indian Ocean. Such waves traveled northward for thousands of miles across the Pacific Ocean. To trace the path and decay of the waves, he established measurement stations on islands and at sea (on R/P FLIP) along a great circle from New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, to the Palmyra Atoll

Palmyra Atoll (), also referred to as Palmyra Island, is one of the Northern Line Islands (southeast of Kingman Reef and north of Kiribati). It is located almost due south of the Hawaiian Islands, roughly one-third of the way between Hawaii a ...

, and finally to Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

. Munk and his family spent nearly the whole of 1963 on American Samoa

American Samoa ( sm, Amerika Sāmoa, ; also ' or ') is an unincorporated territory of the United States located in the South Pacific Ocean, southeast of the island country of Samoa. Its location is centered on . It is east of the Internationa ...

for this experiment. Walter and Judith Munk collaborated in making a film to document the experiment. The results show little decay of wave energy with distance traveled. This work, together with the wartime work on wave forecasting, led to the science of surf forecasting, one of Munk's best-known accomplishments. Munk's pioneering research into surf forecasting was acknowledged in 2007 with an award from the Groundswell Society, a surfing advocacy organization.

Ocean tides

Between 1965 and 1975, Munk turned to investigations of ocean tides, partly motivated by their effects on the Earth's rotation. Modern methods oftime series

In mathematics, a time series is a series of data points indexed (or listed or graphed) in time order. Most commonly, a time series is a sequence taken at successive equally spaced points in time. Thus it is a sequence of discrete-time data. Ex ...

and spectral analysis were brought to bear on tidal analysis, leading to work with David Cartwright developing the "response method" of tidal analysis. With Frank Snodgrass

Wallace Frankham "Frank" Snodgrass (24 April 1898 – 16 July 1976) was a New Zealand rugby union player. A wing, Snodgrass represented Hawke's Bay and Nelson at a provincial level, and was a member of the New Zealand national side, the All Bla ...

, Munk developed deep-ocean pressure sensors that could be used to provide tidal data far from any land. One highlight of this work was the discovery of the semidiurnal amphidrome midway between California and Hawaii.

Internal waves: The Garrett–Munk spectrum

At the time of Munk's dissertation for his master's degree in 1939,internal wave

Internal waves are gravity waves that oscillate within a fluid medium, rather than on its surface. To exist, the fluid must be stratified: the density must change (continuously or discontinuously) with depth/height due to changes, for example, in ...

s were considered an uncommon phenomenon. By the 1970s, there were extensive published observations of internal-wave variability in the oceans in temperature, salinity, and velocity as functions of time, horizontal distance, and depth. Motivated by a 1958 paper by Owen Philips that described a universal spectral form for the variance of ocean surface waves as a function of wave number

In the physical sciences, the wavenumber (also wave number or repetency) is the ''spatial frequency'' of a wave, measured in cycles per unit distance (ordinary wavenumber) or radians per unit distance (angular wavenumber). It is analogous to temp ...

, Chris Garrett and Munk attempted to make sense of the observations by postulating a universal spectrum for internal waves.

According to Munk, they chose a spectrum that could be factored into a function of frequency times a function of vertical wave number. The resulting spectrum, now called the Garrett-Munk Spectrum, is roughly consistent with a large number of diverse measurements that had been obtained over the global ocean. The model evolved over the subsequent decade, denoted GM72, GM75, GM79, etc., according to the year of publication of the revised model. Although Munk expected the model to be rapidly obsolete, it proved to be a universal model that is still in use. Its universality is interpreted as a sign of profound processes governing internal wave dynamics, turbulence and fine-scale mixing. Klaus Hasselmann

Klaus Ferdinand Hasselmann (, born 25 October 1931) is a German oceanographer and climate modeller. He is Professor Emeritus at the University of Hamburg and former Director of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology. He was awarded the 2021 ...

commented in 2010, "...the publication of the GM spectrum has indeed been extremely fruitful for oceanography, both in the past and still today."

Ocean acoustic tomography

Beginning in 1975, Munk and Carl Wunsch of the

Beginning in 1975, Munk and Carl Wunsch of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

pioneered the development of acoustic tomography of the ocean. With Peter Worcester and Robert Spindel, Munk developed the use of sound propagation, particularly sound arrival patterns and travel times, to infer important information about the ocean's large-scale temperature and current. This work, together with the work of other groups, eventually motivated the 1991 "Heard Island Feasibility Test" (HIFT), to determine if man-made acoustic signals could be transmitted over antipodal distances to measure the ocean's climate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in an area, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteorologi ...

. The experiment came to be called "the sound heard around the world." During six days in January 1991, acoustic signals were transmitted by sound sources lowered from the M/V Cory Chouest near Heard Island

The Territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI) is an Australian external territory comprising a volcanic group of mostly barren Antarctic islands, about two-thirds of the way from Madagascar to Antarctica. The group's overall size ...

in the southern Indian Ocean. These signals traveled half-way around the globe to be received on the east and west coasts of the United States, as well as at many other stations around the world.

The follow-up to this experiment was the 1996–2006 Acoustic Thermometry of Ocean Climate (ATOC) project in the North Pacific Ocean. Both HIFT and ATOC engendered considerable public controversy concerning the possible effects of man-made sounds on marine mammals. In addition to the decade-long measurements obtained in the North Pacific, acoustic thermometry has been employed to measure temperature changes of the upper layers of the Arctic Ocean basins, which continues to be an area of active interest. Acoustic thermometry has also been used to determine changes to global-scale ocean temperatures using data from acoustic pulses traveling from Australia to Bermuda.

Tomography has come to be a valuable method of ocean observation, exploiting the characteristics of long-range acoustic propagation to obtain synoptic measurements of average ocean temperature or current. Applications have included the measurement of deep water formation in the Greenland Sea in 1989, measurement of ocean tides, and the estimation of ocean mesoscale dynamics by combining tomography, satellite altimetry

Satellite geodesy is geodesy by means of artificial satellites—the measurement of the form and dimensions of Earth, the location of objects on its surface and the figure of the Earth's gravity field by means of artificial satellite technique ...

, and ''in situ'' data with ocean dynamical models.

Munk advocated for acoustical measurements of the ocean for much of his career, such as his 1986 Bakerian Lecture ''Acoustic Monitoring of Ocean Gyres'', the 1995 monograph ''Ocean Acoustic Tomography'' written with Worcester and Wunsch, and his 2010 Crafoord Prize

The Crafoord Prize is an annual science prize established in 1980 by Holger Crafoord, a Swedish industrialist, and his wife Anna-Greta Crafoord. The Prize is awarded in partnership between the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and the Crafoord Foun ...

lecture ''The Sound of Climate Change''.

Tides and mixing

In the 1990s, Munk returned to the work on the role of tides in producing mixing in the ocean. In a 1966 paper "Abyssal Recipes", Munk was one of the first to assess quantitatively the rate of mixing in the abyssal ocean in maintaining oceanicstratification

Stratification may refer to:

Mathematics

* Stratification (mathematics), any consistent assignment of numbers to predicate symbols

* Data stratification in statistics

Earth sciences

* Stable and unstable stratification

* Stratification, or st ...

. At that time, the tidal energy available for mixing was thought to occur by processes near ocean boundaries. According to Sandström's theorem (1908), without the occurrence deep mixing, driven by, e.g., internal tides or tidally-driven turbulence in shallow regions, most of the ocean would become cold and stagnant, capped by a thin, warm surface layer. The question of tidal energy available for mixing was reawakened in the 1990s with the discovery, by acoustic tomography and satellite altimetry, of large-scale internal tides radiating energy away from the Hawaiian Ridge into the interior of the North Pacific Ocean. Munk recognized that the tidal energy from the scattering and radiation of large-scale internal waves from mid-ocean ridges was significant, hence it could drive abyssal mixing.

Munk's enigma

In his later work, Munk focused on the relation between changes in ocean temperature, sea level, and the transfer of mass between continental ice and the ocean. This work described what came to be known as "Munk's enigma", a large discrepancy between observed rate of sea level rise and its expected effects on the earth's rotation.Awards

Munk was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1956, the

Munk was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1956, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

in 1957, the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

in 1965, and to the Royal Society of London

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1976. He was both a Guggenheim Fellow

Guggenheim Fellowships are grants that have been awarded annually since by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to those "who have demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the a ...

(1948, 1953, 1962) and a Fulbright Fellow

The Fulbright Program, including the Fulbright–Hays Program, is one of several United States Cultural Exchange Programs with the goal of improving intercultural relations, cultural diplomacy, and intercultural competence between the people of ...

. He was named California Scientist of the Year by the California Museum of Science and Industry

The California Science Center (sometimes spelled California ScienCenter) is a state agency and museum located in Exposition Park, Los Angeles, next to the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and the University of Southern California. Bi ...

in 1969. Munk gave the 1986 Bakerian Lecture at the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

on ''Ships from Space'' (paper) and ''Acoustic monitoring of ocean gyres'' (lecture).

In July 2018 at the age of 100, Munk was appointed a Chevalier of France's Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

in recognition of his contributions to oceanography.

Among the many other awards and honors Munk received are the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a non-profit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest achieving individuals in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet ...

, the Arthur L. Day Medal of the Geological Society of America

The Geological Society of America (GSA) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to the advancement of the geosciences.

History

The society was founded in Ithaca, New York, in 1888 by Alexander Winchell, John J. Stevenson, Charles H. Hitch ...

in 1965, the Sverdrup Gold Medal of the American Meteorological Society

The American Meteorological Society (AMS) is the premier scientific and professional organization in the United States promoting and disseminating information about the atmospheric, oceanic, and hydrologic sciences. Its mission is to advance th ...

in 1966, the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

(Whatever shines should be observed)

, predecessor =

, successor =

, formation =

, founder =

, extinction =

, merger =

, merged =

, type = NG ...

in 1968, the first Maurice Ewing Medal of the American Geophysical Union

The American Geophysical Union (AGU) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization of Earth, atmospheric, ocean, hydrologic, space, and planetary scientists and enthusiasts that according to their website includes 130,000 people (not members). AGU's a ...

and the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

in 1976, the Alexander Agassiz Medal

The Alexander Agassiz Medal is awarded every three years by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences for an original contribution in the science of oceanography. It was established in 1911 by Sir John Murray in honor of his friend, the scientist Ale ...

of the National Academy of Sciences in 1976, the Captain Robert Dexter Conrad Award of the U.S. Navy in 1978, the National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social scienc ...

in 1983, the William Bowie Medal

The William Bowie Medal is awarded annually by the American Geophysical Union for "outstanding contributions to fundamental geophysics and for unselfish cooperation in research". The award is the highest honor given by the AGU and is named in honor ...

of the American Geophysical Union

The American Geophysical Union (AGU) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization of Earth, atmospheric, ocean, hydrologic, space, and planetary scientists and enthusiasts that according to their website includes 130,000 people (not members). AGU's a ...

in 1989, the Vetlesen Prize in 1993, the Kyoto Prize

The is Japan's highest private award for lifetime achievement in the arts and sciences. It is given not only to those that are top representatives of their own respective fields, but to "those who have contributed significantly to the scientific, ...

in 1999, the first Prince Albert I Medal in 2001, and the Crafoord Prize

The Crafoord Prize is an annual science prize established in 1980 by Holger Crafoord, a Swedish industrialist, and his wife Anna-Greta Crafoord. The Prize is awarded in partnership between the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and the Crafoord Foun ...

of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 2010 "for his pioneering and fundamental contributions to our understanding of ocean circulation, tides and waves, and their role in the Earth's dynamics".

In 1993, Munk was the first recipient of the Walter Munk Award given "in Recognition of Distinguished Research in Oceanography Related to Sound and the Sea." This award was given jointly by The Oceanography Society, the Office of Naval Research and the US Department of Defense Naval Oceanographic Office

The Naval Oceanographic Office (NAVOCEANO), located at John C. Stennis Space Center in south Mississippi, comprises approximately 1,000 civilian, military and contract personnel responsible for providing oceanographic products and services to al ...

. The award was retired in 2018, and The Oceanographic Society "established the Walter Munk Medal to encompass a broader range of topics in physical oceanography."

Two marine species have been named after Munk. One is ''Sirsoe munki'', a deep-sea worm. The other is '' Mobula munkiana'', also known as Munk's devil ray, a small relative of giant manta rays living in huge schools, and with a remarkable ability to leap far out of the water. A 2017 documentary, '' Spirit of Discovery (Documentary)'', follows Munk in an expedition with the discoverer, his former student Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara, to

Two marine species have been named after Munk. One is ''Sirsoe munki'', a deep-sea worm. The other is '' Mobula munkiana'', also known as Munk's devil ray, a small relative of giant manta rays living in huge schools, and with a remarkable ability to leap far out of the water. A 2017 documentary, '' Spirit of Discovery (Documentary)'', follows Munk in an expedition with the discoverer, his former student Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara, to Cabo Pulmo National Park

Cabo Pulmo National Park ( es, Parque Nacional Cabo Pulmo) is a national marine park on the east coast of Mexico's Baja California Peninsula, spanning the distance between Pulmo Point and Los Frailes Cape, approximately north of Cabo San Lucas ...

in Baja Mexico, the place where the species was first found and described.

Personal life

AfterNazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

annexed Austria in 1938 during the ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

'', Munk applied to be a citizen of the United States. In his first attempt, he failed the citizenship test by giving an overly-detailed answer to a question about the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

. He obtained American citizenship in 1939.

Munk married Martha Chapin in the late 1940s. The marriage ended in divorce in 1953. On June 20, 1953, he married Judith Horton. She was an active participant at Scripps for decades, where she contributed to campus planning, architecture, and the renovation and reuse of historical buildings. The Munks were frequent traveling companions. Judith died in 2006. In 2011, Munk married La Jolla community leader Mary Coakley.

Munk remained actively engaged in scientific endeavors throughout his life, with publications as late as 2016. He turned 100 in October 2017. He died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

on February 8, 2019, at La Jolla, California, aged 101.

Publications

Scientific papers

Munk published 181 scientific papers. They were cited over 11,000 times, an average of 63 times each. Some of the most highly cited papers in the Web of Science database are listed below. * * * * * * * *Books

* W. Munk and G.J.F. MacDonald, ''The Rotation of the Earth: A Geophysical Discussion'', Cambridge University Press, 1960, revised 1975. * W. Munk, P. Worcester, and C. Wunsch, ''Ocean Acoustic Tomography'', Cambridge University Press, 1995. * S. Flatté (ed.), R. Dashen, W. H. Munk, K. M. Watson, and F. Zachariasen, ''Sound Transmission through a Fluctuating Ocean'', Cambridge University Press, 1979.References

External links

*Oral History interview transcript with Walter Munk on 30 June 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives

*

Oral history interview transcript with Walter Munk on 2 July 2004, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library & Archives

* (1967) – a documentary showcasing Munk's research on waves generated by Antarctic storms. The film documents Munk's collaboration as they track storm-driven waves from Antarctica across the Pacific Ocean to Alaska. The film features scenes of early digital equipment in use in field experiments with Munk's commentary on how unsure they were about using such new technology in remote locations. * (1994) – a television program on the work and life of Walter Munk produced by the University of California. * (2004) – a seminar on global sea level and climate change by Walter Munk. (YouTube link)

(2010) – Munk's Crafoord Prize Lecture

Spirit of Discovery

(2017) – a documentary showcasing Munk as he goes in search of ''Mobula munkiana'' a species that bears his name.

A Conversation with Walter Munk

(2019) – Carl Wunsch interviews Walter Munk about his life, career, and scientific events and people during his life on the occasion of his 100th birthday in 2017.

The Heard Island Feasibility Test

Tributes to Walter Munk

(Scripps) {{DEFAULTSORT:Munk, Walter 1917 births 2019 deaths People from La Jolla, San Diego Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences California Institute of Technology alumni Columbia University alumni Foreign Members of the Royal Society Foreign Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences Jewish American scientists Kyoto laureates in Basic Sciences National Medal of Science laureates American centenarians American oceanographers Fluid dynamicists Scripps Institution of Oceanography faculty Scripps Institution of Oceanography alumni Recipients of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society American people of Austrian-Jewish descent Austrian Jews Scientists from Vienna Austrian centenarians Men centenarians University of California, San Diego faculty Members of JASON (advisory group) Founding members of the World Cultural Council Sverdrup Gold Medal Award Recipients Writers from San Diego Writers from Vienna United States Army soldiers 21st-century American Jews Austrian emigrants to the United States Members of the American Philosophical Society