Władysław IV Vasa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Władysław IV Vasa; lt, Vladislovas Vaza; sv, Vladislav IV av Polen; rus, Владислав IV Ваза, r=Vladislav IV Vaza; la, Ladislaus IV Vasa or Ladislaus IV of Poland (9 June 1595 – 20 May 1648) was

The marriage of

The marriage of

With the intensification of the Polish intervention in Muscovy, in 1609, the royal family moved to their residence in

With the intensification of the Polish intervention in Muscovy, in 1609, the royal family moved to their residence in

Before he was elected king of the Commonwealth, Władysław fought in many campaigns, seeking personal glory. After his final campaign against Russians in 1617–18 (the end of Dymitriads), he went to

Before he was elected king of the Commonwealth, Władysław fought in many campaigns, seeking personal glory. After his final campaign against Russians in 1617–18 (the end of Dymitriads), he went to  In 1623, while near

In 1623, while near

The

The

During that campaign Władysław started the modernisation program of the Commonwealth army, emphasising the usage of modern

During that campaign Władysław started the modernisation program of the Commonwealth army, emphasising the usage of modern

The next few years were similarly unsuccessful with regards to his plans. Eventually, he tried to bypass the opposition in the Sejm with secret alliances, dealings, and intrigues, but did not prove successful. Those plans included schemes such as supporting the Holy Roman Emperor's raid on Inflanty in 1639, which he hoped would lead to a war; an attempted alliance with Spain against France in 1640–1641, and in 1641–1643, with Denmark against Sweden. On the international scene, he attempted to mediate between various religious factions of Christianity, using the tolerant image of the Commonwealth to portray himself as the neutral mediator. He organized a conference in

The next few years were similarly unsuccessful with regards to his plans. Eventually, he tried to bypass the opposition in the Sejm with secret alliances, dealings, and intrigues, but did not prove successful. Those plans included schemes such as supporting the Holy Roman Emperor's raid on Inflanty in 1639, which he hoped would lead to a war; an attempted alliance with Spain against France in 1640–1641, and in 1641–1643, with Denmark against Sweden. On the international scene, he attempted to mediate between various religious factions of Christianity, using the tolerant image of the Commonwealth to portray himself as the neutral mediator. He organized a conference in

While hunting near

While hunting near

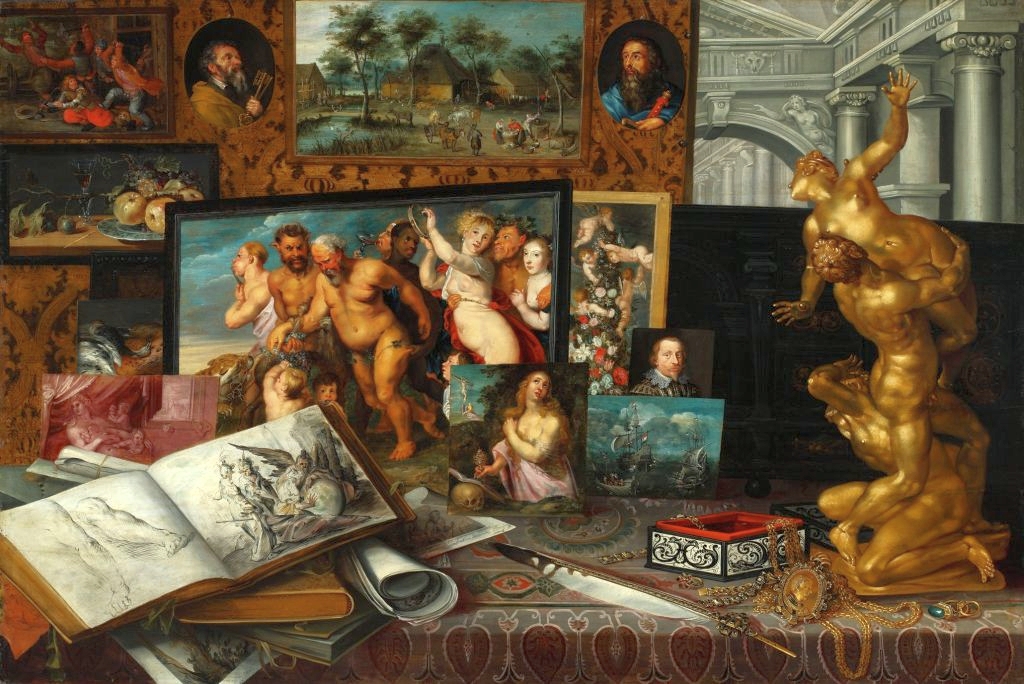

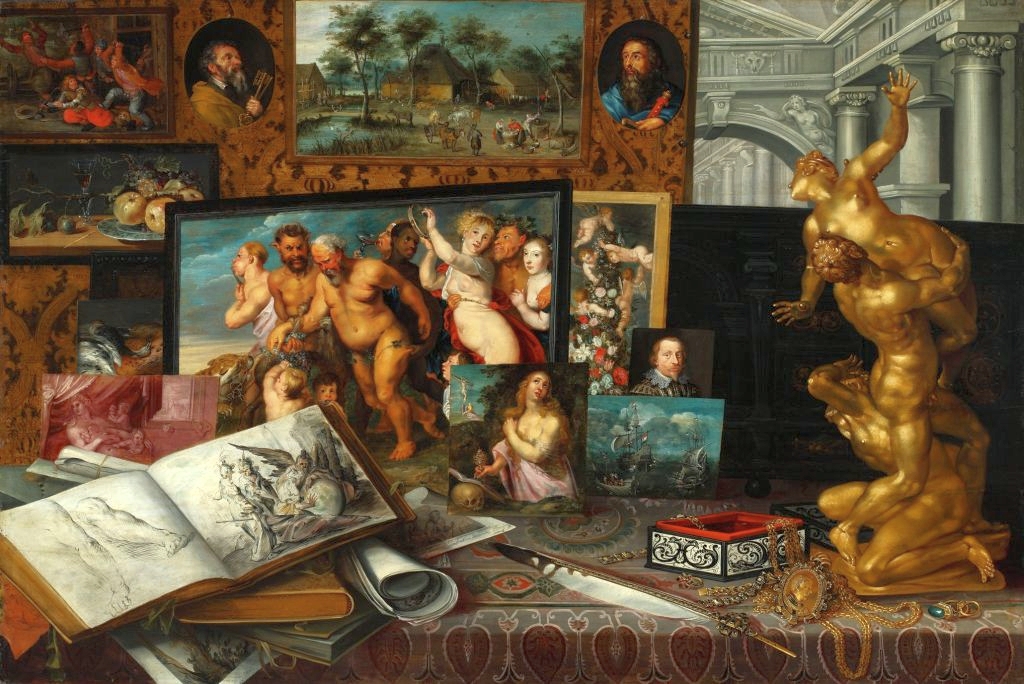

One of the king's most substantial achievements was in the cultural sphere; he became a notable patron of the arts. Władysław was a connoisseur of the arts, in particular, theater and music. He spoke several languages, enjoyed reading historical literature and poetry. He collected paintings and created a notable gallery of paintings in the Warsaw castle. Władysław assembled an important collection of Italian and

One of the king's most substantial achievements was in the cultural sphere; he became a notable patron of the arts. Władysław was a connoisseur of the arts, in particular, theater and music. He spoke several languages, enjoyed reading historical literature and poetry. He collected paintings and created a notable gallery of paintings in the Warsaw castle. Władysław assembled an important collection of Italian and The Rape of Europa

The National Gallery London

Władysław had many plans (dynastic, about wars, territorial gains: regaining Silesia, Inflanty (Livonia), incorporation of Ducal Prussia, creation of his hereditary dukedom etc.), some of them with real chances of success, but for various reasons, most of them ended in failure during his 16-year reign. Though his grand international political plans failed, he did improve the Commonwealth foreign policy, supporting the establishment of a network of permanent diplomatic agents in important European countries.

Throughout his life, Władysław successfully defended Poland against foreign invasions. He was recognized as a good tactician and strategist, who did much to modernize the Polish Army. Władysław ensured that the officer corps was significantly large so that the army could be expanded; introduced foreign (Western) infantry to the Polish Army, with its

Władysław had many plans (dynastic, about wars, territorial gains: regaining Silesia, Inflanty (Livonia), incorporation of Ducal Prussia, creation of his hereditary dukedom etc.), some of them with real chances of success, but for various reasons, most of them ended in failure during his 16-year reign. Though his grand international political plans failed, he did improve the Commonwealth foreign policy, supporting the establishment of a network of permanent diplomatic agents in important European countries.

Throughout his life, Władysław successfully defended Poland against foreign invasions. He was recognized as a good tactician and strategist, who did much to modernize the Polish Army. Władysław ensured that the officer corps was significantly large so that the army could be expanded; introduced foreign (Western) infantry to the Polish Army, with its

Iter per Europam

Bibliotheca Augustana *

Kunstkammer and opera of Władysław Vasa

, - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Wladyslaw 4 1595 births 1648 deaths 17th-century Russian monarchs 17th-century Polish monarchs Grand Dukes of Lithuania Russian tsars House of Vasa Wladislaw 1595 Polish Roman Catholics Dukes of Opole Knights of the Golden Fleece Nobility from Kraków Burials at Vilnius Cathedral Polish people of the Polish–Muscovite War (1605–1618) Polish people of the Smolensk War People of the Polish–Ottoman War (1620–21) Burials at Wawel Cathedral Disinherited European royalty Sons of kings

King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16t ...

, Grand Duke of Lithuania

The monarchy of Lithuania concerned the monarchical head of state of Lithuania, which was established as an absolute and hereditary monarchy. Throughout Lithuania's history there were three ducal dynasties that managed to stay in power—House ...

and claimant of the thrones of Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

. Władysław IV was the eldest son of Sigismund III Vasa and Sigismund's first wife, Anna of Austria.

Born into the House of Vasa

The House of Vasa or Wasa Georg Starbäck in ''Berättelser ur Sweriges Medeltid, Tredje Bandet'' pp 264, 275, 278, 291–296 & 321 ( sv, Vasaätten, pl, Wazowie, lt, Vazos) was an early modern royal house founded in 1523 in Sweden. Its memb ...

, Władysław was elected Tsar of Russia

This is a list of all reigning monarchs in the history of Russia. It includes the princes of medieval Rus′ state (both centralised, known as Kievan Rus′ and feudal, when the political center moved northeast to Vladimir and finally to Mos ...

by the Seven Boyars

The Seven Boyars (russian: link=no, Семибоярщина, the Russian term indicating "Rule of the Seven Boyars" or "the Deeds of the Seven Boyars") were a group of Russian nobles who deposed Tsar Vasily Shuisky on 17 July 1610 and, later that ...

in 1610 when the Polish army captured Moscow, but did not assume the throne due to his father's position and a popular uprising. Nevertheless, until 1634 he used the titular title of Grand Duke of Muscovy Muscovy is an alternative name for the Grand Duchy of Moscow (1263–1547) and the Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721). It may also refer to:

*Muscovy Company, an English trading company chartered in 1555

* Muscovy duck (''Cairina moschata'') and Domes ...

, a principality centered around Moscow. Elected king of Poland in 1632, he was largely successful in defending the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth against foreign invasion, most notably in the Smolensk War

The Smolensk War (1632–1634) was a conflict fought between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Russia.

Hostilities began in October 1632 when Russian forces tried to capture the city of Smolensk. Small military engagements produced mix ...

of 1632–34, in which he participated personally.

He supported religious tolerance

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

and carried out military reforms, such as the founding of the Commonwealth Navy. Władysław was also a renowned patron of the arts and music. He failed, however, at reclaiming the Swedish throne, gaining fame by defeating the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, strengthening royal power, and reforming the Commonwealth's political system. Despite these failures, his personal charisma and popularity among all segments of society contributed to relative internal calm in the Commonwealth.

He died without a legitimate son and was succeeded to the Polish throne by his half-brother, John II Casimir Vasa

John II Casimir ( pl, Jan II Kazimierz Waza; lt, Jonas Kazimieras Vaza; 22 March 1609 – 16 December 1672) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1648 until his abdication in 1668 as well as titular King of Sweden from 1648 ...

. Władysław's death marked the end of relative stability in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, as conflicts and tensions that had been growing over several decades came to a head with devastating consequences. The Khmelnytsky Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising,; in Ukraine known as Khmelʹnychchyna or uk, повстання Богдана Хмельницького; lt, Chmelnickio sukilimas; Belarusian language, Belarusian: Паўстанне Багдана Хмяльніц ...

in the east (1648) and the subsequent Swedish invasion ("the Deluge

The Genesis flood narrative (chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis) is the Hebrew version of the universal flood myth. It tells of God's decision to return the universe to its pre- creation state of watery chaos and remake it through the microc ...

", 1655–60) weakened the country and diminished Poland's status as a regional power. For this reason, Władysław's reign was seen in following decades as a bygone golden era of stability and prosperity.

Life

Władysław IV's father,Sigismund III Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa ( pl, Zygmunt III Waza, lt, Žygimantas Vaza; 20 June 1566 – 30 April 1632

N.S.) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1587 to 1632 and, as Sigismund, King of Sweden and Grand Duke of Finland from 1592 to ...

, grandson of Sweden's King Gustav I, had succeeded his father to the Swedish throne

The monarchy of Sweden is the monarchical head of state of Sweden,See the Instrument of Government, Chapter 1, Article 5. which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system.Parliamentary system: see the Instrument ...

in 1592, only to be deposed in 1599 by his uncle, subsequently King Charles IX. This resulted in a long-standing feud, with the Polish kings

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16th ...

of the House of Vasa

The House of Vasa or Wasa Georg Starbäck in ''Berättelser ur Sweriges Medeltid, Tredje Bandet'' pp 264, 275, 278, 291–296 & 321 ( sv, Vasaätten, pl, Wazowie, lt, Vazos) was an early modern royal house founded in 1523 in Sweden. Its memb ...

claiming the Swedish throne. This led to the Polish–Swedish War of 1600–29 and later to the Deluge

The Genesis flood narrative (chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis) is the Hebrew version of the universal flood myth. It tells of God's decision to return the universe to its pre- creation state of watery chaos and remake it through the microc ...

of 1655.

Childhood

The marriage of

The marriage of Anne of Austria

Anne of Austria (french: Anne d'Autriche, italic=no, es, Ana María Mauricia, italic=no; 22 September 1601 – 20 January 1666) was an infanta of Spain who became Queen of France as the wife of King Louis XIII from their marriage in 1615 unti ...

to Sigismund III was a traditional, politically motivated marriage, intended to tie the young House of Vasa

The House of Vasa or Wasa Georg Starbäck in ''Berättelser ur Sweriges Medeltid, Tredje Bandet'' pp 264, 275, 278, 291–296 & 321 ( sv, Vasaätten, pl, Wazowie, lt, Vazos) was an early modern royal house founded in 1523 in Sweden. Its memb ...

to the prestigious Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

s. Władysław was born 9 June 1595 at the King's summer residence in Łobzów, near Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

, a few months after the main Wawel Castle

The Wawel Royal Castle (; ''Zamek Królewski na Wawelu'') and the Wawel Hill on which it sits constitute the most historically and culturally significant site in Poland. A fortified residency on the Vistula River in Kraków, it was established on ...

had been consumed by fire.

Władysław's mother died on 10 February 1598, less than three years after giving birth to him. He was raised by one of her former ladies of the court, Urszula Meierin, who eventually became a powerful player at the royal court, with much influence.

Władysław's Hofmeister was Michał Konarski, a Polish-Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

n noble. Around early 17th century Urszula lost much of her influence, as Władysław gained new teachers and mentors, including such priests

as Marek Łętkowski, Gabriel Prowancjusz, and Andrzej Szołdrski

Andrzej Szołdrski (c. 1583–1650) of Łodzia coat of arms was a Polish nobleman and Roman Catholic priest. Son of Stanisław Szołdrski, owner of Czempiń, and Małgorzata Manicka. He studied at Jesuit school in Poznań. According to some so ...

and in military matters by Zygmunt Kazanowski

Zygmunt Kazanowski (1563–1634) was a noble (szlachcic), magnate in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Courtier and Court Marshal of kings Stefan Batory, Sigismund III Vasa and teacher of Wladyslaw IV Waza. From 1613 Starost of Kokenhaus ...

.

Much of his curriculum was likely designed by Father Piotr Skarga

Piotr Skarga (less often Piotr Powęski; 2 February 1536 – 27 September 1612) was a Polish Jesuit, preacher, hagiographer, polemicist, and leading figure of the Counter-Reformation in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Due to his oratoric ...

, much respected by Sigmismund III. Władysław studied for several years in the Kraków Academy

The Jagiellonian University (Polish: ''Uniwersytet Jagielloński'', UJ) is a public research university in Kraków, Poland. Founded in 1364 by King Casimir III the Great, it is the oldest university in Poland and the 13th oldest university in ...

, and for two years, in Rome.

At the age of 10, he received his own prince court. He formed a friendship with brothers Adam and Stanisław Kazanowski. It was reported that young Władysław was interested in arts; later this led to him becoming an important patron of the arts. He spoke and wrote in German, Italian and Latin.

Władysław was liked by the szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (Polish: endonym, Lithuanian: šlėkta) were the noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth who, as a class, had the dominating position in the ...

(Polish nobility), but his father's plans to secure him the throne of Poland ('' vivente rege'') were unpopular and eventually crushed in the Zebrzydowski Rebellion (rokosz

A rokosz () originally was a gathering of all the Polish ''szlachta'' (nobility), not merely of deputies, for a ''sejm''. The term was introduced to the Polish language from Hungary, where analogous gatherings took place at a field called Rákos ...

).

Tsar

With the intensification of the Polish intervention in Muscovy, in 1609, the royal family moved to their residence in

With the intensification of the Polish intervention in Muscovy, in 1609, the royal family moved to their residence in Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

, capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire of Austria. The state was founded by Li ...

, where he witnessed the fire of Vilnius, which required the royal family to evacuate from Vilnius Castle. Later that year, Władysław, aged 15, was elected Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

by Muscovy Muscovy is an alternative name for the Grand Duchy of Moscow (1263–1547) and the Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721). It may also refer to:

*Muscovy Company, an English trading company chartered in 1555

* Muscovy duck (''Cairina moschata'') and Domes ...

's aristocracy council of ''Seven boyars

The Seven Boyars (russian: link=no, Семибоярщина, the Russian term indicating "Rule of the Seven Boyars" or "the Deeds of the Seven Boyars") were a group of Russian nobles who deposed Tsar Vasily Shuisky on 17 July 1610 and, later that ...

'', who overthrew tsar Vasily Shuysky during the Polish-Muscovite War and Muscovy's Time of Troubles

The Time of Troubles (russian: Смутное время, ), or Smuta (russian: Смута), was a period of political crisis during the Tsardom of Russia which began in 1598 with the death of Fyodor I (Fyodor Ivanovich, the last of the Rurik dy ...

.

His election was ruined by his father, Sigismund, who aimed to convert Muscovy's population from the Eastern Orthodox religion to Roman Catholicism. Sigismund refused to agree to the boyar's request to send prince Władysław to Moscow and his conversion to Orthodoxy. Instead, Sigismund proposed that he should reign as a regent in Muscovy instead. This unrealistic proposal led to a resumption of hostilities. In 1611-12, silver and gold coins (kopeck

The kopek or kopeck ( rus, копейка, p=kɐˈpʲejkə, ukr, копійка, translit=kopiika, p=koˈpʲijkə, be, капейка) is or was a coin or a currency unit of a number of countries in Eastern Europe closely associated with t ...

s) were prematurely stuck in the Russian mints in Moscow and Novgorod with Władysław's titulary ''Tsar and Grand Prince Vladislav Zigimontovych of all Russia''.

Władysław tried to regain the tsar's throne himself, organizing a campaign in 1616. Despite some military victories, he was unable to capture Moscow. The Commonwealth gained some disputed territories in the Truce of Deulino

The Truce of Deulino (also known as Peace or Treaty of Dywilino) concluded the Polish–Muscovite War (1609–1618) between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia. It was signed on 11 December 1618 and took effect on 4 Jan ...

, but Władysław was never able to reign in Russia; the throne during this time was instead held by tsar Michael Romanov. He held on to the title, without any real power, until 1634.

Likely, the failure of this campaign showed Władysław the limits of royal power in Poland, as major factors for the failure included significant autonomy of the military commanders, which did not see Władysław as their superior, and lack of funds for the army, as the Polish parliament (sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of t ...

) refused to subsidize the war.

Prince

Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

in 1619 looking for an opportunity to aid the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

in their struggle against the Czech Hussites

The Hussites ( cs, Husité or ''Kališníci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Huss ...

in the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

, an opportunity that never materialized.

In 1620, he took part in the second phase of the Polish–Ottoman War, a consequence of the long series of struggles between Poland and the Ottomans over Moldavia. In 1621, he was a Polish commander at Chocim

Khotyn ( uk, Хотин, ; ro, Hotin, ; see other names) is a city in Dnistrovskyi Raion, Chernivtsi Oblast of western Ukraine and is located south-west of Kamianets-Podilskyi. It hosts the administration of Khotyn urban hromada, one of the ...

. He reportedly he was stricken with illness but despite that proved a voice of reason, convincing other Polish commanders there to stay and fight. His advice was correct, and the battle eventually ended with a peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring ...

that returned the status quo from before the Ottoman invasion. This peace treaty also gave Władysław an international reputation as a "defender of the Christian faith", and increased his popularity in the Commonwealth itself.

In 1623, while near

In 1623, while near Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

(Danzig), he witnessed Gustavus Adolphus

Gustavus Adolphus (9 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">N.S_19_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 19 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/now ...

's Swedish Navy

The Swedish Navy ( sv, Svenska marinen) is the naval branch of the Swedish Armed Forces. It is composed of surface and submarine naval units – the Fleet () – as well as marine units, the Amphibious Corps ().

In Swedish, vessels o ...

use its naval superiority to demand concessions from Gdańsk (the Commonwealth had no navy).

In 1624, King Sigismund decided that the time had come for Władysław to travel, like many of his peers, to Western Europe. For security reasons, Władysław traveled under a fake name, Snopkowski (from Polish Snopek, meaning sheaf

Sheaf may refer to:

* Sheaf (agriculture), a bundle of harvested cereal stems

* Sheaf (mathematics), a mathematical tool

* Sheaf toss, a Scottish sport

* River Sheaf, a tributary of River Don in England

* ''The Sheaf'', a student-run newspaper se ...

, as seen in the Vasa's coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central ele ...

). On the long voyage (1624–25), he was accompanied by Albrycht Stanisław Radziwiłł and other courtiers.

First, he travelled to Wrocław

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, rou ...

(Breslau), then Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

, where he met Maximilian I, Elector of Bavaria

Maximilian I (17 April 157327 September 1651), occasionally called the Great, a member of the House of Wittelsbach, ruled as Duke of Bavaria from 1597. His reign was marked by the Thirty Years' War during which he obtained the title of a Prince- ...

. In Brussels he met Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain

Isabella Clara Eugenia ( es, link=no, Isabel Clara Eugenia; 12 August 1566 – 1 December 1633), sometimes referred to as Clara Isabella Eugenia, was sovereign of the Spanish Netherlands in the Low Countries and the north of modern France with ...

; in Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

, Rubens. Near Breda

Breda () is a city and municipality in the southern part of the Netherlands, located in the province of North Brabant. The name derived from ''brede Aa'' ('wide Aa' or 'broad Aa') and refers to the confluence of the rivers Mark and Aa. Breda has ...

he met Ambrosio Spinola

Ambrogio Spinola Doria, 1st Marquess of Los Balbases and 1st Duke of Sesto (1569-25 September 1630) was an Italian ''condottiero'' and nobleman of the Republic of Genoa, who served as a Spanish general and won a number of important battles. He i ...

. It was during his stay with Spinola that he was impressed by Western military techniques; this was later reflected when he became king, as military matters were always important to him.

While not a military genius, and surpassed by his contemporary, Commonwealth hetman

( uk, гетьман, translit=het'man) is a political title from Central and Eastern Europe, historically assigned to military commanders.

Used by the Czechs in Bohemia since the 15th century. It was the title of the second-highest military co ...

Stanisław Koniecpolski

Stanisław Koniecpolski (1591 – 11 March 1646) was a Polish military commander, regarded as one of the most talented and capable in the History of Poland in the Early Modern era (1569–1795), history of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. ...

, Władysław was known as a fairly skillful commander on his own. In Rome he was welcomed by Pope Urban VIII

Pope Urban VIII ( la, Urbanus VIII; it, Urbano VIII; baptised 5 April 1568 – 29 July 1644), born Maffeo Vincenzo Barberini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 August 1623 to his death in July 1644. As po ...

, who congratulated him on his fighting against the Ottomans. During his stay in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

he was impressed by opera, and decided to bring this form of art to the Commonwealth, where it was previously unknown.

In Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

and Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

he was impressed by the local shipyards, and in Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the cit ...

he witnessed a specially organized mock naval battle, experiences that resulted in his later attempt to create the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Navy

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Navy was the navy of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Early history

The Commonwealth Navy was small and played a relatively minor role in the history of the Commonwealth.

Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodor ...

.

After returning to Poland, he fought in 1626 against the Swedes

Swedes ( sv, svenskar) are a North Germanic ethnic group native to the Nordic region, primarily their nation state of Sweden, who share a common ancestry, culture, history and language. They mostly inhabit Sweden and the other Nordic countr ...

in the last phase of the Polish–Swedish War, where he took part in the battle of Gniew. His involvement in this conflict, which lasted till the Truce of Altmark

__NOTOC__

The six-year Truce of Altmark (or Treaty of Stary Targ, pl, Rozejm w Altmarku, sv, Stillståndet i Altmark) was signed on 16 (O.S.)/26 (N.S.) September 1629 in the village of Altmark (Stary Targ), in Poland, by the Polish–Lithuani ...

in 1629, was rather limited, and he spent much time in other parts of the country.

During that period and afterward, he lobbied for support of his candidature for the Polish throne, as his father, Sigismund, was getting more advanced in his age, and the succession to the Polish throne did not occur through inheritance but rather through the process of royal elections

An elective monarchy is a monarchy ruled by an elected monarch, in contrast to a hereditary monarchy in which the office is automatically passed down as a family inheritance. The manner of election, the nature of candidate qualifications, and the ...

. While Władysław, and his father tried to ensure Władysław's election during Sigismund's lifetime, this was not a popular option for the nobility, and it repeatedly failed, up to and including at the sejm of 1631.

Sigismund suffered a sudden stroke in late April 1632 and died in the morning hours of 30 April, forcing the matter to be raised again.

King

The

The election sejm of 1632

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

eventually chose Władysław; there were no other serious contenders. The decision reached on 8 November, but as the ''pacta conventa

''Pacta conventa'' (Latin for "articles of agreement") was a contractual agreement, from 1573 to 1764 entered into between the "Polish nation" (i.e., the szlachta (nobility) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) and a newly elected king upon ...

'' were not yet ready, the official announcement was delayed until 13 November. In the ''pacta conventa'', Władysław pledged himself to fund a military school and equipment; to find a way to fund a navy; to maintain current alliances; not to raise armies, give offices or military ranks to foreigners, negotiate peace treaties, or declare war without the Sejm's approval; not to take a wife without the Senate's approval; to convince his brothers to take an oath to the Commonwealth; and to transfer the profits from the Royal Mint to the Royal Treasury rather than to a private treasury. When the election result was announced by the Crown Grand Marshal, Łukasz Opaliński, the ''szlachta'' (nobility), who had taken part in the election, began festivities in honor of the new king, which lasted three hours. Władysław was crowned in the Wawel Cathedral

The Wawel Cathedral ( pl, Katedra Wawelska), formally titled the Royal Archcathedral Basilica of Saints Stanislaus and Wenceslaus, is a Roman Catholic cathedral situated on Wawel Hill in Kraków, Poland. Nearly 1000 years old, it is part of the ...

, in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

on 6 February in the following year.

Military campaigns

In an attempt to take advantage of the confusion expected after the death of the Polish king, TsarMichael I of Russia

Michael I (Russian: Михаил Фёдорович Романов, ''Mikhaíl Fyódorovich Románov'') () became the first Russian tsar of the House of Romanov after the Zemskiy Sobor of 1613 elected him to rule the Tsardom of Russia.

He w ...

invaded the Commonwealth. A Muscovite army crossed the Commonwealth eastern frontier in October 1632 and laid siege to Smolensk

Smolensk ( rus, Смоленск, p=smɐˈlʲensk, a=smolensk_ru.ogg) is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow. First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest c ...

(which was ceded to Poland by Russia in 1618, at the end of the Dymitriad wars). In the war against Russia in 1632–1634 (the Smolensk War

The Smolensk War (1632–1634) was a conflict fought between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Russia.

Hostilities began in October 1632 when Russian forces tried to capture the city of Smolensk. Small military engagements produced mix ...

), Władysław broke the siege in September 1633 and then in turn surrounded the Russian army under Mikhail Shein

Mikhail Borisovich Shein (Михаил Борисович Шеин, ) (late 1570s–1634) was a leading Russian general during the reign of Tsar Mikhail Romanov. Despite his tactical skills and successful military career, he ended up losing his ar ...

, which was then forced to surrender on 1 March 1634.

infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

and artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

. Władysław proved to be a good tactician, and his innovations in the use of artillery and fortifications based on Western ideas greatly contributed to the eventual Polish–Lithuanian success. King Władysław wanted to continue the war or, because the Polish–Swedish Treaty of Altmark

__NOTOC__

The six-year Truce of Altmark (or Treaty of Stary Targ, pl, Rozejm w Altmarku, sv, Stillståndet i Altmark) was signed on 16 (O.S.)/26 (N.S.) September 1629 in the village of Altmark (Stary Targ), in Poland, by the Polish–Lithuani ...

would soon be expiring, ally with the Russians to strike against Sweden. However, the Sejm wanted no more conflict. As Stanisław Łubieński, the Bishop of Płock

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

, wrote two weeks after Shein's surrender: "Our happiness is in remaining within our borders, guaranteeing health and well-being." The resulting Peace of Polyanov (Treaty of Polanów), favourable to Poland, confirmed the pre-war territorial ''status quo''. Muscovy also agreed to pay 20,000 rubles

The ruble (American English) or rouble (Commonwealth English) (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is the currency unit of Belarus and Russia. Historically, it was the currency of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union.

, currencies named ''rub ...

in exchange for Wladyslaw's renunciation of all claims to the tsardom and return of the royal insignia, which were in the Commonwealth possession since the Dymitriads.

Following the Smolensk campaign, the Commonwealth was threatened by another attack by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. During the wars against Ottomans in 1633–1634 Władysław moved the Commonwealth army south of the Muscovy border, where under the command of hetman

( uk, гетьман, translit=het'man) is a political title from Central and Eastern Europe, historically assigned to military commanders.

Used by the Czechs in Bohemia since the 15th century. It was the title of the second-highest military co ...

Stanisław Koniecpolski

Stanisław Koniecpolski (1591 – 11 March 1646) was a Polish military commander, regarded as one of the most talented and capable in the History of Poland in the Early Modern era (1569–1795), history of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. ...

it forced the Turks to renew a peace treaty. In the resulting treaty, both countries agreed again to curb the border raids by Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

and the Tatars

The Tatars ()Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

, and the Ottomans confirmed that the Commonwealth to be an independent power, and had not to pay tribute to the Empire.

After the southern campaign, the Commonwealth had to deal with a threat from the north, as the armistice, ending the in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

Polish–Swedish War (1600–1629) The Polish–Swedish War (1600–1629) was twice interrupted by periods of truce and thus can be divided into:

* Polish–Swedish War (1600–1611)

* Polish–Swedish War (1617–18)

* Polish–Swedish War (1621–1625)

The Polish–Swedish W ...

was expiring. The majority of Polish nobles preferred to solve the problem through negotiations, unwilling to pay taxes for a new war, provided that Sweden was open to negotiations and concessions (in particular, to retreat from the occupied Polish coastal territories). Władysław himself was hoping for a war, which could yield some more significant territorial gains, and even managed to gather a sizeable army, with navy elements, near the disputed territories. Sweden, weakened by involvement in the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

, was however open to a peaceful solution. Władysław could not go against the decision of the Sejm and Senate, and agreed to support the treaty. Thus both sides agreed to sign the Armistice of Stuhmsdorf (Sztumska Wieś) on 12 September 1635, favourable to the Commonwealth, which regained the Prussian territories, and called for a reduction of the Swedish tolls on the maritime trade.

Politics

In the three months between his election and coronation, Władysław sounded the waters regarding the possibility of a peaceful succession to the Swedish throne, following the recent death of Gustavus Adolphus, but this, as well as his proposal to mediate between Sweden and its enemies, was rejected, primarily by the Swedish chancellor and head of the regency council, Axel Oxenstierna. Władysław IV owed nominal allegiance to the ImperialHabsburgs

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

as a member of the Order of the Golden Fleece

The Distinguished Order of the Golden Fleece ( es, Insigne Orden del Toisón de Oro, german: Orden vom Goldenen Vlies) is a Catholic order of chivalry founded in Bruges by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in 1430, to celebrate his marriage ...

. His relationship with the Habsburgs was relatively strong; although he was not above carrying some negotiations with their enemies, like France, he refused Cardinal Richelieu's 1635 proposal of an alliance and a full-out war against them, despite potential lure of territorial gains in Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

. He realized that such a move would cause much unrest in a heavily Catholic Commonwealth, that he likely lacked the authority and power to push such a change of policy through the Sejm, and that the resulting conflict would be very difficult. From 1636 onward, for the next few years, Władysław strengthened his ties with the Habsburgs.

In the meantime, Władysław still tried to take a leading role in European politics, and negotiate a peaceful settlement to the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

, a settlement which he hoped would ease his way into regaining the Swedish crown. Following the armistice of Stuhmsdorf, Władysław came to increasingly realize that his prospects for regaining the Swedish throne were dim. In the years 1636–1638 he proposed several reforms to strengthen his and his dynasty's power in the Commonwealth. His first plan was an attempt to secure a hereditary province within the country, which would not be threatened by the possible power shift following a future royal election; this, however, did not gain sufficient support in the Sejm. Next, Władysław attempted to create an order of chivalry

An order of chivalry, order of knighthood, chivalric order, or equestrian order is an order (distinction), order of knights, typically founded during or inspired by the original Catholic Military order (religious society), military orders of the ...

, similar to the Order of the Golden Fleece

The Distinguished Order of the Golden Fleece ( es, Insigne Orden del Toisón de Oro, german: Orden vom Goldenen Vlies) is a Catholic order of chivalry founded in Bruges by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in 1430, to celebrate his marriage ...

, but this plan was scuttled down as well, with the szlachta and the magnates seeing this as an attempt to create a royal, loyalist elite, and traditionally opposing anything that could lead to the reduction of their extensive power. Popular vote and opposition also resulted in the failure of the plan to raise taxes from trade tariffs; here it was not only the nobility but even the merchants and burghers from towns, like Gdańsk

Gdańsk ( , also ; ; csb, Gduńsk;Stefan Ramułt, ''Słownik języka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego'', Kraków 1893, Gdańsk 2003, ISBN 83-87408-64-6. , Johann Georg Theodor Grässe, ''Orbis latinus oder Verzeichniss der lateinischen Benen ...

(Danzig) who were able to muster enough support (including from foreign powers) to stop the king's reforms. In fact, the defeat of his plans was so total, that he was forced to make certain conciliatory gestures to the nobility, as the Sejm passed several laws constraining his authority (such as to hire foreign troops), further indicating the limits of royal power in the Commonwealth.

Marriages

Early in his reign, there were plans regarding a marriage of Władysław and PrincessElisabeth of Bohemia, Princess Palatine

Elisabeth of the Palatinate (26 December 1618 – 11 February 1680), also known as Elisabeth of Bohemia, Princess Elisabeth of the Palatinate, or Princess-Abbess of Herford Abbey, was the eldest daughter of Frederick V, Elector Palatine (who was b ...

(daughter of Frederick V, Elector Palatine

Frederick V (german: link=no, Friedrich; 26 August 1596 – 29 November 1632) was the Elector Palatine of the Rhine in the Holy Roman Empire from 1610 to 1623, and reigned as King of Bohemia from 1619 to 1620. He was forced to abdicate both ...

). This was however unpopular, both with Catholic nobles and the Catholic Church, and when it became clear to Władysław that this would not convince the Swedes to elect him to their throne, this plan, with quiet support from Władysław himself, was dropped.

Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor

Ferdinand II (9 July 1578 – 15 February 1637) was Holy Roman Emperor, King of Bohemia, King of Hungary, Hungary, and List of Croatian monarchs, Croatia from 1619 until his death in 1637. He was the son of Charles II, Archduke of Austria, Archd ...

's proposal of marriage between Władysław and Archduchess

Archduke (feminine: Archduchess; German: ''Erzherzog'', feminine form: ''Erzherzogin'') was the title borne from 1358 by the Habsburg rulers of the Archduchy of Austria, and later by all senior members of that dynasty. It denotes a rank within ...

Cecilia Renata of Austria (sister of future Ferdinand III, Holy Roman Emperor

Ferdinand III (Ferdinand Ernest; 13 July 1608, in Graz – 2 April 1657, in Vienna) was from 1621 Archduke of Austria, King of Hungary from 1625, King of Croatia and Bohemia from 1627 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1637 until his death in 1657.

...

) arrived in Warsaw somewhere during spring 1636. In June that year, Władysław sent Jerzy Ossoliński

Prince Jerzy Ossoliński h. Topór (15 December 1595 – 9 August 1650) was a Polish nobleman ('' szlachcic''), Crown Court Treasurer from 1632, governor (''voivode'') of Sandomierz from 1636, ''Reichsfürst'' (Imperial Prince) since 1634, Cro ...

to the Imperial Court, to work on improving the Imperial-Commonwealth relations. The king's trusted confessor, father Walerian Magni (of Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related Mendicant orders, mendicant Christianity, Christian Catholic religious order, religious orders within the Catholic Church. Founded in 1209 by Italian Catholic friar Francis of Assisi, these orders include t ...

religious order), and voivode Kasper Doenhoff

Prince Kasper Doenhoff (german: Kaspar von Dönhoff, pl, Kacper Denhoff, 1587–1645) was a Polish nobleman of Baltic-German extraction, a Reichsfürst of the Holy Roman Empire and Governor of Dorpat Province within the Polish–Lithuanian Co ...

arrived in Regensburg ( pl, Ratyzbona) on 26 October 1636 with consent and performed negotiations. The Archduchess' dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment b ...

was agreed for 100,000 zlotys, the Emperor also promised to pay the dowries of both of Siegmund III's wives: Anna

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th century)

* Anna (Anisia) (fl. 1218 to 12 ...

and Konstance. Additionally the son of Władysław and Cecilia Renata was to obtain the duchy of Opole

Duchy of Opole ( pl, Księstwo opolskie; german: Herzogtum Oppeln; cs, Opolské knížectví) was one of the duchies of Silesia ruled by the Piast dynasty. Its capital was Opole (Oppeln, Opolí) in Upper Silesia.

Duke Boleslaw III 'the Wrymo ...

and Racibórz

Racibórz (german: Ratibor, cz, Ratiboř, szl, Racibōrz) is a city in Silesian Voivodeship in southern Poland. It is the administrative seat of Racibórz County.

With Opole, Racibórz is one of the historic capitals of Upper Silesia, being t ...

in Silesia (Duchy of Opole and Racibórz

The Duchy of Opole and Racibórz ( pl, Księstwo opolsko-raciborskie, german: Herzogtum Oppeln und Ratibor) was one of the numerous Duchies of Silesia ruled by the Silesian branch of the royal Polish Piast dynasty. It was formed in 1202 from the ...

). However, before everything was confirmed and signed Ferdinand II died and Ferdinand III backed from giving the Silesian duchy to the son of Władysław. Instead a dowry was awarded to be secured by the Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

n estates of Třeboň

Třeboň (; german: Wittingau) is a spa town in Jindřichův Hradec District in the South Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 8,100 inhabitants. The town centre with the castle complex is well preserved and is protected by law as an ...

( Trebon). On 16 March 1637 a "family alliance" was signed between the Habsburgs and the Polish branch of the House of Vasa. Władysław promised not to sign any pacts against the Habsburgs, and to transfer his rights to the Swedish throne in case of his line's extinction; in return, Habsburg promised to support his efforts to regain the Swedish crown, and to transfer to him some territory in case of gains in a war against the Ottomans. The marriage took place in 1637, on 12 September.

The next few years were similarly unsuccessful with regards to his plans. Eventually, he tried to bypass the opposition in the Sejm with secret alliances, dealings, and intrigues, but did not prove successful. Those plans included schemes such as supporting the Holy Roman Emperor's raid on Inflanty in 1639, which he hoped would lead to a war; an attempted alliance with Spain against France in 1640–1641, and in 1641–1643, with Denmark against Sweden. On the international scene, he attempted to mediate between various religious factions of Christianity, using the tolerant image of the Commonwealth to portray himself as the neutral mediator. He organized a conference in

The next few years were similarly unsuccessful with regards to his plans. Eventually, he tried to bypass the opposition in the Sejm with secret alliances, dealings, and intrigues, but did not prove successful. Those plans included schemes such as supporting the Holy Roman Emperor's raid on Inflanty in 1639, which he hoped would lead to a war; an attempted alliance with Spain against France in 1640–1641, and in 1641–1643, with Denmark against Sweden. On the international scene, he attempted to mediate between various religious factions of Christianity, using the tolerant image of the Commonwealth to portray himself as the neutral mediator. He organized a conference in Toruń

)''

, image_skyline =

, image_caption =

, image_flag = POL Toruń flag.svg

, image_shield = POL Toruń COA.svg

, nickname = City of Angels, Gingerbread city, Copernicus Town

, pushpin_map = Kuyavian-Pom ...

(Thorn) that begun on 28 January 1645, but it failed to reach any meaningful conclusions.

After Cecilia's death in 1644, the ties between Władysław and the Habsburgs were somewhat loosened. In turn, the relations with France improved, and eventually Władysław married the French princess Ludwika Maria Gonzaga de Nevers, daughter of Charles I Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, in 1646.

Władysław's last plan was to orchestrate a major war between the European powers and the Ottoman Empire. The border with the Empire was in a near constant state of low-level warfare; some historians estimate that in the first half of the 17th century, Ottoman raids and wars resulted in the loss (death or enslavement) of about 300,000 Commonwealth citizens in the borderlands. The war, Władysław hoped, would also solve the problem of unrest among the Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

, a militant group living in the Ukraine, near the Ottoman border, who could find worth in such a campaign, and turn their attention to fighting for the Commonwealth, instead of against it. As usual, he failed to inspire the nobility, rarely willing to consider sponsoring another war, to agree to this plan. He received more support from foreign powers, from Rome, Venice and Muscovy. With the promise of funds for the war, Władysław started recruiting troops among the Cossacks in 1646. The opposition of the Sejm, demanding that he dismiss the troops, coupled with Władysław's worsening health, crippled that plan as well. Władysław still did not give up, and attempted to resurrect the plan in 1647, and with support of magnate Jeremi Wiśniowiecki

Prince Jeremi Wiśniowiecki ( uk, Ярема Вишневецький – Yarema Vyshnevetsky; 1612 – 20 August 1651) nicknamed ''Hammer on the Cossacks'' ( pl, Młot na Kozaków), was a notable member of the aristocracy of the Polish–Lith ...

(who organized military exercises near Ottoman border), attempted unsuccessfully to provoke the Ottomans to attack.

On 9 August 1647, his young son, Sigismund Casimir

Sigismund Casimir Vasa ( pl, Zygmunt Kazimierz Waza; 1 April 1640 – 9 August 1647), was a Polish prince and the only legitimate son of King Ladislaus IV and his first wife Queen Cecilia Renata. He was named after his grandfather Sigismun ...

, then seven years old, suddenly fell ill and died; the death of his only legitimate heir to the throne was a major blow to the king, whose grief prevented his attendance at the boy's funeral held in Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

.

Death

While hunting near

While hunting near Merkinė

Merkinė is a town in the Dzūkija National Park in Lithuania, located at the confluence of the Merkys, Stangė, and Nemunas rivers. Merkinė is one of the oldest settlements in Lithuania. The first settlers inhabited the confluence of Merkys a ...

(Merecz) in early 1648, Władysław suffered from a case of gallstones

A gallstone is a stone formed within the gallbladder from precipitated bile components. The term cholelithiasis may refer to the presence of gallstones or to any disease caused by gallstones, and choledocholithiasis refers to the presence of mi ...

or kidney stones

Kidney stone disease, also known as nephrolithiasis or urolithiasis, is a crystallopathy where a solid piece of material (kidney stone) develops in the urinary tract. Kidney stones typically form in the kidney and leave the body in the urine s ...

. The King's condition supposedly worsened as he was given the incorrect medication to treat the ailment. Being aware that these might be his final days, the King had his last will

A will or testament is a legal document that expresses a person's (testator) wishes as to how their property ( estate) is to be distributed after their death and as to which person (executor) is to manage the property until its final distributio ...

dictated and then received his last rites

The last rites, also known as the Commendation of the Dying, are the last prayers and ministrations given to an individual of Christian faith, when possible, shortly before death. They may be administered to those awaiting execution, mortall ...

. Władysław died around 02:00 at night on 20 May 1648.

His heart and ''viscera

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a ...

'' were interred in the Chapel of St. Casimir of Vilnius Cathedral

The Cathedral Basilica of St Stanislaus and St Ladislaus of Vilnius ( lt, Vilniaus Šv. Stanislovo ir Šv. Vladislovo arkikatedra bazilika; pl, Bazylika archikatedralna św. Stanisława Biskupa i św. Władysława, historical: ''Kościół Kated ...

. As he had no legitimate male heirs, he was succeeded by his half brother John II Casimir Vasa

John II Casimir ( pl, Jan II Kazimierz Waza; lt, Jonas Kazimieras Vaza; 22 March 1609 – 16 December 1672) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1648 until his abdication in 1668 as well as titular King of Sweden from 1648 ...

.

Character

Władysław has been described as outgoing and friendly, with a sense of humor, optimistic, a "people's person", able to charm many of those who interacted with him. On the other hand, he had a short temper and when angered, could act without considering all consequences. Władysław was criticized for being a spendthrift; he lived lavishly, spending more than his royal court treasury could afford. He also dispensed much wealth among hiscourtier

A courtier () is a person who attends the royal court of a monarch or other royalty. The earliest historical examples of courtiers were part of the retinues of rulers. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the official r ...

s, who were seen by people farther from the court as taking advantage of the king. He has also been known to maintain several mistresses throughout his life, including during his married period.

Patronage

One of the king's most substantial achievements was in the cultural sphere; he became a notable patron of the arts. Władysław was a connoisseur of the arts, in particular, theater and music. He spoke several languages, enjoyed reading historical literature and poetry. He collected paintings and created a notable gallery of paintings in the Warsaw castle. Władysław assembled an important collection of Italian and

One of the king's most substantial achievements was in the cultural sphere; he became a notable patron of the arts. Władysław was a connoisseur of the arts, in particular, theater and music. He spoke several languages, enjoyed reading historical literature and poetry. He collected paintings and created a notable gallery of paintings in the Warsaw castle. Władysław assembled an important collection of Italian and Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including t ...

paintings, much of which were lost in the wars after his death. He sponsored many musicians and in 1637 created the first amphitheater

An amphitheatre (British English) or amphitheater (American English; both ) is an open-air venue used for entertainment, performances, and sports. The term derives from the ancient Greek ('), from ('), meaning "on both sides" or "around" and ...

in the palace, the first theater in Poland, where during his reign dozens of operas and ballets were performed. He is credited with bringing the very genre

Genre () is any form or type of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially-agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other for ...

of opera to Poland. Władysław's attention to theater contributed to the spread of this art form in Poland. He was also interested in poetry, as well as in cartography

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an im ...

and historical and scientific works; he corresponded with Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

.

Notable painters and engravers Władysław supported and who attended his royal court included Peter Paul Rubens, Tommaso Dolabella

Tommaso Dolabella ( pl, Tomasz Dolabella; 1570 – 17 January 1650) was a Baroque Italian painter from Venice, who settled in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth at the royal court of King Sigismund III Vasa.

Active in the historical capita ...

, Peter Danckerts de Rij

Pieter, Peeter, or Peter Danckerts de Rij, Dankers de Ry, or Peteris Dankersas (1605, in Amsterdam – buried 15 December 1660, Amsterdam). was a Dutch Golden Age painter mostly active in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Sweden.

Lif ...

, Wilhelm Hondius

Willem Hondius or Willem Hondt (c. 1598 in The Hague – 1652 or 1658 in Danzig (Gdańsk)) was a Dutch engraver, cartographer and painter who spent most of his life in Poland.

Life

Willem Hondius was one of seven children of Hendrik Hondius the ...

, Bartłomiej Strobel, and Christian Melich. His royal orchestra was headed by kapellmeister

(, also , ) from German ''Kapelle'' (chapel) and ''Meister'' (master)'','' literally "master of the chapel choir" designates the leader of an ensemble of musicians. Originally used to refer to somebody in charge of music in a chapel, the term ha ...

Marco Scacchi

Marco Scacchi (ca. 1600 – 7 September 1662) was an Italian composer and writer on music.

Scacchi was born in Gallese, Lazio. He studied under Giovanni Francesco Anerio in Rome. He was associated with the court at Warsaw from 1626, and was '' ...

, seconded by Bartłomiej Pękiel.

One of the most renowned works he ordered was the raising of the Sigismund's Column

Sigismund's Column ( pl, Kolumna Zygmunta), originally erected in 1644, is located at Castle Square, Warsaw, Poland and is one of Warsaw's most famous landmarks as well as the first secular monument in the form of a column in modern history. The ...

in Warsaw. The column, dedicated to his father, was designed by the Italian-born architect Constantino Tencalla and the sculptor Clemente Molli, and cast by Daniel Tym. He was less interested in decorative architecture; he supported the construction of two palaces in Warsaw – Kazanowski Palace

The Kazanowski Palace ( pl, pałac Kazanowskich), also known as the Radziejowski Palace, was a large palace in Warsaw, occupying the place where the Charitable Center ''Res Sacra Miser'' stands today.

History

When prince Władysław Vasa (future K ...

and '' Villa Regia''. Among other works sponsored by or dedicated to him is Guido Reni

Guido Reni (; 4 November 1575 – 18 August 1642) was an Italian painter of the Baroque period, although his works showed a classical manner, similar to Simon Vouet, Nicolas Poussin, and Philippe de Champaigne. He painted primarily religious ...

's '' The Rape of Europa''.The National Gallery London

Assessment

Władysław had many plans (dynastic, about wars, territorial gains: regaining Silesia, Inflanty (Livonia), incorporation of Ducal Prussia, creation of his hereditary dukedom etc.), some of them with real chances of success, but for various reasons, most of them ended in failure during his 16-year reign. Though his grand international political plans failed, he did improve the Commonwealth foreign policy, supporting the establishment of a network of permanent diplomatic agents in important European countries.

Throughout his life, Władysław successfully defended Poland against foreign invasions. He was recognized as a good tactician and strategist, who did much to modernize the Polish Army. Władysław ensured that the officer corps was significantly large so that the army could be expanded; introduced foreign (Western) infantry to the Polish Army, with its

Władysław had many plans (dynastic, about wars, territorial gains: regaining Silesia, Inflanty (Livonia), incorporation of Ducal Prussia, creation of his hereditary dukedom etc.), some of them with real chances of success, but for various reasons, most of them ended in failure during his 16-year reign. Though his grand international political plans failed, he did improve the Commonwealth foreign policy, supporting the establishment of a network of permanent diplomatic agents in important European countries.

Throughout his life, Władysław successfully defended Poland against foreign invasions. He was recognized as a good tactician and strategist, who did much to modernize the Polish Army. Władysław ensured that the officer corps was significantly large so that the army could be expanded; introduced foreign (Western) infantry to the Polish Army, with its pike

Pike, Pikes or The Pike may refer to:

Fish

* Blue pike or blue walleye, an extinct color morph of the yellow walleye ''Sander vitreus''

* Ctenoluciidae, the "pike characins", some species of which are commonly known as pikes

* ''Esox'', genus of ...

s and early firearms, and supported the expansion of the artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

. His attempt to create a Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Navy

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Navy was the navy of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Early history

The Commonwealth Navy was small and played a relatively minor role in the history of the Commonwealth.

Juliusz Bardach, Boguslaw Lesnodor ...

resulted in the creation of a new port village, Władysławowo

Władysławowo ( Kashubian/ Pomeranian: ''Wiôlgô Wies'', german: Großendorf) is a city on the south coast of the Baltic Sea in Kashubia in the Pomerelia region, northern Poland, with 15,015 (2009) inhabitants.

History

In 1634 engineer Fryd ...

. Despite promising beginnings, Władysław failed to secure enough funds for the fleet creation; the ships were gone – sunk, or stolen – by the 1640s.

The king, while Catholic, was very tolerant and did not support the more aggressive policies of the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

. When he took power, the Senate of Poland

The Senate ( pl, Senat) is the upper house of the Parliament of Poland, Polish parliament, the lower house being the Sejm of the Republic of Poland, Sejm. The history of the Polish Senate stretches back over 500 years; it was one of the first co ...

had 6 Protestant members; at the time of his death, it had 11. Despite his support for religious tolerance, he did fail, however, to resolve the conflict stemming from the Union of Brest

The Union of Brest (; ; ; ) was the 1595–96 decision of the Ruthenian Orthodox Church eparchies (dioceses) in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to break relations with the Eastern Orthodox Church and to enter into communion with, and place i ...

split. Despite his support for the Protestants, he did not stop the growing tide of intolerance, either in Poland or abroad, as shown by the fate of the Racovian Academy

The Racovian Academy ('' la, Gymnasium Bonarum Artium'') was a Socinian school operated from 1602 to 1638 by the Polish Brethren in Raków, Sandomierz Voivodeship of Lesser Poland.

The communitarian Arian settlement of Raków was founded in 1569 ...

, or an international disagreement between the faiths. Neither did he get involved with the disagreement about the Orthodox Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

, a group that he respected and counted on in his plans.

In internal politics he attempted to strengthen the power of the monarchy, but this was mostly thwarted by the szlachta, who valued their independence and democratic powers. Władysław suffered continuing difficulties caused by the efforts of the Polish Sejm (parliament) to check the King's power and limit his dynastic ambitions. Władysław was fed up with the weak position of the king in the Commonwealth; his politics included attempting to secure a small, preferably hereditary territory – like a duchy

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a Middle Ages, medieval country, territory, fiefdom, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or Queen regnant, queen in Western European tradition.

There once exis ...

– where his position would be much stronger.

Władysław used the title of the King of Sweden

The monarchy of Sweden is the monarchical head of state of Sweden,See the Instrument of Government, Chapter 1, Article 5. which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system.Parliamentary system: see the Instrument o ...

, although he had no control over Sweden whatsoever and never set foot in that country. However, he continued his attempts to regain the Swedish throne, with similar lack of results as his father. He might have been willing to trade his claim away, but the offer was never put down in the negotiations.

Some historians see Władysław as a dreamer who could not stick to one policy, and upon running into first difficulties, ditched it and looked for another opportunity. Perhaps it was due to this lukewarmness that Władysław was never able to inspire those he ruled to support, at least in any significant manner, any of his plans. Władysław Czapliński in his biography of the king is more understanding, noting the short period of his reign (16 years) and the weakness of the royal position he was forced to deal with.

Several years after his death, a diplomatic mission from Muscovy demanded that publications about Władysław's victories in the Smolensk War

The Smolensk War (1632–1634) was a conflict fought between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Russia.

Hostilities began in October 1632 when Russian forces tried to capture the city of Smolensk. Small military engagements produced mix ...

of 1633–1634 be collected and burned. Eventually, to much controversy, their demand was met. Polish historian Maciej Rosalak noted: "under the reign of Władysław IV, such a shameful event would have never been allowed."

Royal titles

* InLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

: "''Vladislaus Quartus Dei gratia rex Poloniae, magnus dux Lithuaniae, Russiae, Prussiae, Masoviae, Samogitiae, Livoniaeque, Smolenscie, Severiae, Czernichoviaeque necnon Suecorum, Gothorum Vandalorumque haereditarius rex, electus magnus dux Moschoviae.''"

* In English: "Władysław IV, by grace of God the King of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

, Grand Duke of Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

, Ruthenia

Ruthenia or , uk, Рутенія, translit=Rutenia or uk, Русь, translit=Rus, label=none, pl, Ruś, be, Рутэнія, Русь, russian: Рутения, Русь is an exonym, originally used in Medieval Latin as one of several terms ...

, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

, Masovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( pl, Mazowsze) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the unofficial capital and largest city. Throughout the centurie ...

, Samogitia

Samogitia or Žemaitija ( Samogitian: ''Žemaitėjė''; see below for alternative and historical names) is one of the five cultural regions of Lithuania and formerly one of the two core administrative divisions of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

, Livonia

Livonia ( liv, Līvõmō, et, Liivimaa, fi, Liivinmaa, German and Scandinavian languages: ', archaic German: ''Liefland'', nl, Lijfland, Latvian and lt, Livonija, pl, Inflanty, archaic English: ''Livland'', ''Liwlandia''; russian: Ли ...

, Smolensk

Smolensk ( rus, Смоленск, p=smɐˈlʲensk, a=smolensk_ru.ogg) is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow. First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest c ...

, Severia

Severia or Siveria ( orv, Сѣверія, russian: Северщина, translit=Severshchina, uk, Сіверія or , translit. ''Siveria'' or ''Sivershchyna'') is a historical region in present-day southwest Russia, northern Ukraine, eastern ...

and Chernigov

Chernihiv ( uk, Черні́гів, , russian: Черни́гов, ; pl, Czernihów, ; la, Czernihovia), is a List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative ...

and hereditary King of the Swedes

Swedes ( sv, svenskar) are a North Germanic ethnic group native to the Nordic region, primarily their nation state of Sweden, who share a common ancestry, culture, history and language. They mostly inhabit Sweden and the other Nordic countr ...

, Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

and Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

, elected Grand Duke of Muscovy Muscovy is an alternative name for the Grand Duchy of Moscow (1263–1547) and the Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721). It may also refer to:

*Muscovy Company, an English trading company chartered in 1555

* Muscovy duck (''Cairina moschata'') and Domes ...

."

In 1632 Władysław was elected King of Poland. He claimed to be King of Sweden

The monarchy of Sweden is the monarchical head of state of Sweden,See the Instrument of Government, Chapter 1, Article 5. which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system.Parliamentary system: see the Instrument o ...

by paternal inheritance, but was never able to gain possession of that throne. His titles were the longest of any Polish king ever.

Ancestry

See also

*History of Poland (1569–1795)

The history of Poland spans over a thousand years, from medieval tribes, Christianization and monarchy; through Poland's Golden Age, expansionism and becoming one of the largest European powers; to its collapse and partitions, two world wars, ...

* Golden Liberty

Golden Liberty ( la, Aurea Libertas; pl, Złota Wolność, lt, Auksinė laisvė), sometimes referred to as Golden Freedoms, Nobles' Democracy or Nobles' Commonwealth ( pl, Rzeczpospolita Szlachecka or ''Złota wolność szlachecka'') was a pol ...

Notes