Workhouses In Lancashire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as

The workhouse system evolved in the 17th century, allowing parishes to reduce the cost to ratepayers of providing poor relief. The first authoritative figure for numbers of workhouses comes in the next century from ''The Abstract of Returns made by the Overseers of the Poor'', which was drawn up following a government survey in 1776. It put the number of parish workhouses in England and Wales at more than 1800 (about one parish in seven), with a total capacity of more than 90,000 places. This growth in the number of workhouses was prompted by the

The workhouse system evolved in the 17th century, allowing parishes to reduce the cost to ratepayers of providing poor relief. The first authoritative figure for numbers of workhouses comes in the next century from ''The Abstract of Returns made by the Overseers of the Poor'', which was drawn up following a government survey in 1776. It put the number of parish workhouses in England and Wales at more than 1800 (about one parish in seven), with a total capacity of more than 90,000 places. This growth in the number of workhouses was prompted by the

By 1832 the amount spent on poor relief nationally had risen to £7 million a year, more than 10

By 1832 the amount spent on poor relief nationally had risen to £7 million a year, more than 10

The New Poor Law Commissioners were very critical of existing workhouses, and generally insisted that they be replaced. They complained in particular that "in by far the greater number of cases, it is a large almshouse, in which the young are trained in idleness, ignorance, and vice; the able-bodied maintained in sluggish sensual indolence; the aged and more respectable exposed to all the misery that is incident to dwelling in such a society".

After 1835 many workhouses were constructed with the central buildings surrounded by work and exercise yards enclosed behind brick walls, so-called "pauper bastilles". The commission proposed that all new workhouses should allow for the segregation of paupers into at least four distinct groups, each to be housed separately: the aged and impotent, children, able-bodied males, and able-bodied females. A common layout resembled

The New Poor Law Commissioners were very critical of existing workhouses, and generally insisted that they be replaced. They complained in particular that "in by far the greater number of cases, it is a large almshouse, in which the young are trained in idleness, ignorance, and vice; the able-bodied maintained in sluggish sensual indolence; the aged and more respectable exposed to all the misery that is incident to dwelling in such a society".

After 1835 many workhouses were constructed with the central buildings surrounded by work and exercise yards enclosed behind brick walls, so-called "pauper bastilles". The commission proposed that all new workhouses should allow for the segregation of paupers into at least four distinct groups, each to be housed separately: the aged and impotent, children, able-bodied males, and able-bodied females. A common layout resembled

Each Poor Law Union employed one or more relieving officers, whose job it was to visit those applying for assistance and assess what relief, if any, they should be given. Any applicants considered to be in need of immediate assistance could be issued with a note admitting them directly to the workhouse. Alternatively they might be offered any necessary money or goods to tide them over until the next meeting of the guardians, who would decide on the appropriate level of support and whether or not the applicants should be assigned to the workhouse.

Workhouses were designed with only a single entrance guarded by a porter, through which inmates and visitors alike had to pass. Near to the entrance were the casual wards for tramps and vagrants and the relieving rooms, where paupers were housed until they had been examined by a medical officer. After being assessed the paupers were separated and allocated to the appropriate ward for their category: boys under 14, able-bodied men between 14 and 60, men over 60, girls under 14, able-bodied women between 14 and 60, and women over 60. Children under the age of two were allowed to remain with their mothers, but by entering a workhouse paupers were considered to have forfeited responsibility for their families. Clothing and personal possessions were taken from them and stored, to be returned on their discharge. After bathing, they were issued with a distinctive uniform: for men it might be a striped cotton shirt, jacket and trousers, and a cloth cap, and for women a blue-and-white striped dress worn underneath a smock. Shoes were also provided. In some establishments certain categories of inmate were marked out by their clothing; for example, at Bristol Incorporation workhouse, prostitutes were required to wear a yellow dress and pregnant single women a red dress; such practices were deprecated by the Poor Law Commission in a directive issued in 1839 entitled "Ignominious Dress for Unchaste Women in Workhouses", but they continued until at least 1866. Some workhouses had a separate "foul" or "itch" ward, where inmates diagnosed with skin diseases such as

Each Poor Law Union employed one or more relieving officers, whose job it was to visit those applying for assistance and assess what relief, if any, they should be given. Any applicants considered to be in need of immediate assistance could be issued with a note admitting them directly to the workhouse. Alternatively they might be offered any necessary money or goods to tide them over until the next meeting of the guardians, who would decide on the appropriate level of support and whether or not the applicants should be assigned to the workhouse.

Workhouses were designed with only a single entrance guarded by a porter, through which inmates and visitors alike had to pass. Near to the entrance were the casual wards for tramps and vagrants and the relieving rooms, where paupers were housed until they had been examined by a medical officer. After being assessed the paupers were separated and allocated to the appropriate ward for their category: boys under 14, able-bodied men between 14 and 60, men over 60, girls under 14, able-bodied women between 14 and 60, and women over 60. Children under the age of two were allowed to remain with their mothers, but by entering a workhouse paupers were considered to have forfeited responsibility for their families. Clothing and personal possessions were taken from them and stored, to be returned on their discharge. After bathing, they were issued with a distinctive uniform: for men it might be a striped cotton shirt, jacket and trousers, and a cloth cap, and for women a blue-and-white striped dress worn underneath a smock. Shoes were also provided. In some establishments certain categories of inmate were marked out by their clothing; for example, at Bristol Incorporation workhouse, prostitutes were required to wear a yellow dress and pregnant single women a red dress; such practices were deprecated by the Poor Law Commission in a directive issued in 1839 entitled "Ignominious Dress for Unchaste Women in Workhouses", but they continued until at least 1866. Some workhouses had a separate "foul" or "itch" ward, where inmates diagnosed with skin diseases such as  Conditions in the casual wards were worse than in the relieving rooms, and deliberately designed to discourage vagrants, who were considered potential troublemakers and probably disease-ridden. Vagrants who presented themselves at the door of a workhouse were at the mercy of the porter, whose decision it was whether or not to allocate them a bed for the night in the casual ward. Those refused entry risked being sentenced to two weeks of hard labour if they were found begging or sleeping in the open and prosecuted for an offence under the

Conditions in the casual wards were worse than in the relieving rooms, and deliberately designed to discourage vagrants, who were considered potential troublemakers and probably disease-ridden. Vagrants who presented themselves at the door of a workhouse were at the mercy of the porter, whose decision it was whether or not to allocate them a bed for the night in the casual ward. Those refused entry risked being sentenced to two weeks of hard labour if they were found begging or sleeping in the open and prosecuted for an offence under the

In 1836 the Poor Law Commission distributed six diets for workhouse inmates, one of which was to be chosen by each Poor Law Union depending on its local circumstances. Although dreary, the food was generally nutritionally adequate, and according to contemporary records was prepared with great care. Issues such as training staff to serve and weigh portions were well understood. The diets included general guidance, as well as schedules for each class of inmate. They were laid out on a weekly rotation, the various meals selected on a daily basis, from a list of foodstuffs. For instance, a breakfast of bread and

In 1836 the Poor Law Commission distributed six diets for workhouse inmates, one of which was to be chosen by each Poor Law Union depending on its local circumstances. Although dreary, the food was generally nutritionally adequate, and according to contemporary records was prepared with great care. Issues such as training staff to serve and weigh portions were well understood. The diets included general guidance, as well as schedules for each class of inmate. They were laid out on a weekly rotation, the various meals selected on a daily basis, from a list of foodstuffs. For instance, a breakfast of bread and

Education was provided for the children, but workhouse teachers were a particular problem. Poorly paid, without any formal training, and facing large classes of unruly children with little or no interest in their lessons, few stayed in the job for more than a few months. In an effort to force workhouses to offer at least a basic level of education, legislation was passed in 1845 requiring that all pauper apprentices should be able to read and sign their own

Education was provided for the children, but workhouse teachers were a particular problem. Poorly paid, without any formal training, and facing large classes of unruly children with little or no interest in their lessons, few stayed in the job for more than a few months. In an effort to force workhouses to offer at least a basic level of education, legislation was passed in 1845 requiring that all pauper apprentices should be able to read and sign their own

Although the commissioners were responsible for the regulatory framework within which the Poor Law Unions operated, each union was run by a locally elected board of guardians, comprising representatives from each of the participating parishes, assisted by six ''

Although the commissioners were responsible for the regulatory framework within which the Poor Law Unions operated, each union was run by a locally elected board of guardians, comprising representatives from each of the participating parishes, assisted by six ''

A second major wave of workhouse construction began in the mid-1860s, the result of a damning report by the Poor Law inspectors on the conditions found in infirmaries in London and the provinces. Of one workhouse in

A second major wave of workhouse construction began in the mid-1860s, the result of a damning report by the Poor Law inspectors on the conditions found in infirmaries in London and the provinces. Of one workhouse in  By 1870 the architectural fashion had moved away from the corridor design in favour of a pavilion style based on the military hospitals built during and after the

By 1870 the architectural fashion had moved away from the corridor design in favour of a pavilion style based on the military hospitals built during and after the

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouse

A poorhouse or workhouse is a government-run (usually by a county or municipality) facility to support and provide housing for the dependent or needy.

Workhouses

In England, Wales and Ireland (but not in Scotland), ‘workhouse’ has been the ...

s.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse'' is from 1631, in an account by the mayor of Abingdon reporting that "we have erected wthn our borough a workhouse to set poorer people to work".

The origins of the workhouse can be traced to the Statute of Cambridge 1388

The Statute of Cambridge 1388 (12 Rich. 2, ch. 7) was a piece of English legislation that placed restrictions on the movements of labourers and beggars. It prohibited any labourer from leaving the Hundred (county subdivision), hundred, Rape (county ...

, which attempted to address the labour shortages following the Black Death in England

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic, which reached England in June 1348. It was the first and most severe manifestation of the second pandemic, caused by ''Yersinia pestis'' bacteria. The term ''Black Death'' was not used until the l ...

by restricting the movement of labourers, and ultimately led to the state becoming responsible for the support of the poor. However, mass unemployment following the end of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

in 1815, the introduction of new technology to replace agricultural workers in particular, and a series of bad harvests, meant that by the early 1830s the established system of poor relief was proving to be unsustainable. The New Poor Law of 1834 attempted to reverse the economic trend by discouraging the provision of relief to anyone who refused to enter a workhouse. Some Poor Law authorities hoped to run workhouses at a profit by utilising the free labour of their inmates. Most were employed on tasks such as breaking stones, crushing bones to produce fertiliser, or picking oakum

Oakum is a preparation of tarred fibre used to seal gaps. Its main traditional applications were in shipbuilding, for caulking or packing the joints of timbers in wooden vessels and the deck planking of iron and steel ships; in plumbing, for s ...

using a large metal nail known as a spike.

As the 19th century wore on, workhouses increasingly became refuges for the elderly, infirm, and sick rather than the able-bodied poor, and in 1929 legislation was passed to allow local authorities to take over workhouse infirmaries as municipal hospitals. Although workhouses were formally abolished by the same legislation in 1930, many continued under their new appellation of Public Assistance Institutions under the control of local authorities. It was not until the introduction of the National Assistance Act 1948

The National Assistance Act 1948 is an Act of Parliament passed in the United Kingdom by the Labour government of Clement Attlee. It formally abolished the Poor Law system that had existed since the reign of Elizabeth I, and established a social s ...

that the last vestiges of the Poor Law finally disappeared, and with them the workhouses.

Legal and social background

Medieval to Early Modern period

TheStatute of Cambridge 1388

The Statute of Cambridge 1388 (12 Rich. 2, ch. 7) was a piece of English legislation that placed restrictions on the movements of labourers and beggars. It prohibited any labourer from leaving the Hundred (county subdivision), hundred, Rape (county ...

was an attempt to address the labour shortage caused by the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

, a devastating pandemic

A pandemic () is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has spread across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. A widespread endemic (epidemiology), endemic disease wi ...

that killed about one-third of England's population. The new law fixed wages and restricted the movement of labourers, as it was anticipated that if they were allowed to leave their parishes

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or m ...

for higher-paid work elsewhere then wages would inevitably rise. According to historian Derek Fraser, the fear of social disorder following the plague ultimately resulted in the state, and not a "personal Christian charity", becoming responsible for the support of the poor. The resulting laws against vagrancy

Vagrancy is the condition of homelessness without regular employment or income. Vagrants (also known as bums, vagabonds, rogues, tramps or drifters) usually live in poverty and support themselves by begging, scavenging, petty theft, temporar ...

were the origins of state-funded relief for the poor. From the 16th century onwards a distinction was legally enshrined between those who were willing to work but could not, and those who were able to work but would not: between "the genuinely unemployed and the idler". Supporting the destitute was a problem exacerbated by King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

's Dissolution of the Monasteries, which began in 1536. They had been a significant source of charitable relief, and provided a good deal of direct and indirect employment. The Poor Relief Act of 1576 went on to establish the principle that if the able-bodied poor needed support, they had to work for it.

The Act for the Relief of the Poor 1601

The Poor Relief Act 1601 (43 Eliz 1 c 2) was an Act of the Parliament of England. The Act for the Relief of the Poor 1601, popularly known as the Elizabethan Poor Law, "43rd Elizabeth" or the Old Poor Law was passed in 1601 and created a poor ...

made parishes legally responsible for the care of those within their boundaries who, through age or infirmity, were unable to work. The Act essentially classified the poor into one of three groups. It proposed that the able-bodied be offered work in a house of correction

The house of correction was a type of establishment built after the passing of the Elizabethan Poor Law (1601), places where those who were "unwilling to work", including vagrants and beggars, were set to work. The building of houses of correctio ...

(the precursor of the workhouse), where the "persistent idler" was to be punished. It also proposed the construction of housing for the impotent poor

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of he ...

, the old and the infirm, although most assistance was granted through a form of poor relief

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of hel ...

known as outdoor relief

Outdoor relief, an obsolete term originating with the Elizabethan Poor Law (1601), was a program of social welfare and poor relief. Assistance was given in the form of money, food, clothing or goods to alleviate poverty without the requirement t ...

– money, food, or other necessities given to those living in their own homes, funded by a local tax

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regional, local, or n ...

on the property of the wealthiest in the parish.

Georgian era

The workhouse system evolved in the 17th century, allowing parishes to reduce the cost to ratepayers of providing poor relief. The first authoritative figure for numbers of workhouses comes in the next century from ''The Abstract of Returns made by the Overseers of the Poor'', which was drawn up following a government survey in 1776. It put the number of parish workhouses in England and Wales at more than 1800 (about one parish in seven), with a total capacity of more than 90,000 places. This growth in the number of workhouses was prompted by the

The workhouse system evolved in the 17th century, allowing parishes to reduce the cost to ratepayers of providing poor relief. The first authoritative figure for numbers of workhouses comes in the next century from ''The Abstract of Returns made by the Overseers of the Poor'', which was drawn up following a government survey in 1776. It put the number of parish workhouses in England and Wales at more than 1800 (about one parish in seven), with a total capacity of more than 90,000 places. This growth in the number of workhouses was prompted by the Workhouse Test Act 1723

The Workhouse Test Act 1723 (9 George 1, c.7) also known as the General Act or Knatchbull's Act was poor relief legislation passed by the British government by Sir Edward Knatchbull in 1723. The "workhouse test" was that a person who wanted to ...

; by obliging anyone seeking poor relief to enter a workhouse and undertake a set amount of work, usually for no pay (a system called indoor relief), the Act helped prevent irresponsible claims on a parish's poor rate.

The growth was also bolstered by the Relief of the Poor Act 1782

The Relief of the Poor Act 1782 (22 Geo.3 c.83), also known as Gilbert's Act, was a British poor relief law proposed by Thomas Gilbert which aimed to organise poor relief on a county basis, counties being organised into parishes which could set ...

, proposed by Thomas Gilbert. Gilbert's Act was intended to allow parishes to share the cost of poor relief by joining together to form unions, known as Gilbert Unions, to build and maintain even larger workhouses to accommodate the elderly and infirm. The able-bodied poor were instead either given outdoor relief or found employment locally. Relatively few Gilbert Unions were set up, but the supplementing of inadequate wages under the Speenhamland system

The Speenhamland system was a form of outdoor relief intended to mitigate rural poverty in England and Wales at the end of the 18th century and during the early 19th century. The law was an amendment to the Elizabethan Poor Law. It was created a ...

did become established towards the end of the 18th century. So keen were some Poor Law

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of hel ...

authorities to cut costs wherever possible that cases were reported of husbands being forced to sell their wives, to avoid them becoming a financial burden on the parish. In one such case in 1814 the wife and child of Henry Cook, who were living in Effingham workhouse, were sold at Croydon

Croydon is a large town in south London, England, south of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Croydon, a local government district of Greater London. It is one of the largest commercial districts in Greater London, with an extensi ...

market for one shilling (5p); the parish paid for the cost of the journey and a "wedding dinner".

By the 1830s most parishes had at least one workhouse, but many were badly managed. In his 1797 work, ''The State of the Poor'', Sir Frederick Eden, wrote:

Instead of a workhouse, some sparsely populated parishes placed homeless paupers into rented accommodation, and provided others with relief in their own homes. Those entering a workhouse might join anywhere from a handful to several hundred other inmates; for instance, between 1782 and 1794 Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

's workhouse accommodated 900–1200 indigent men, women and children. The larger workhouses such as the Gressenhall House of Industry generally served a number of communities, in Gressenhall

Gressenhall is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk.

The villages name origin is uncertain possibly 'Grassy nook of land' or 'gravelly nook of land'.

It covers an area of and had a population of 1,008 in 443 households ...

's case 50 parishes. Writing in 1854, Poor Law commissioner George Nicholls viewed many of them as little more than factories:

1834 Act

By 1832 the amount spent on poor relief nationally had risen to £7 million a year, more than 10

By 1832 the amount spent on poor relief nationally had risen to £7 million a year, more than 10 shillings

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence or ...

(£0.50) per head of population, up from £2 million in 1784. The large number of those seeking assistance was pushing the system to "the verge of collapse". The economic downturn following the end of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

in the early 19th century resulted in increasing numbers of unemployed. Coupled with developments in agriculture that meant less labour was needed on the land, along with three successive bad harvests beginning in 1828 and the Swing Riots of 1830, reform was inevitable.

Many suspected that the system of poor relief was being widely abused. In 1832 the government established a Royal Commission to investigate and recommend how relief could best be given to the poor. The result was the establishment of a centralised Poor Law Commission in England and Wales under the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834

The ''Poor Law Amendment Act 1834'' (PLAA) known widely as the New Poor Law, was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed by the Whig government of Earl Grey. It completely replaced earlier legislation based on the ''Poor Relief ...

, also known as the New Poor Law, which discouraged the allocation of outdoor relief to the able-bodied; "all cases were to be 'offered the house', and nothing else". Individual parishes were grouped into Poor Law Unions, each of which was to have a union workhouse. More than 500 of these were built during the next 50 years, two-thirds of them by 1840. In certain parts of the country there was a good deal of resistance to these new buildings, some of it violent, particularly in the industrial north. Many workers lost their jobs during the major economic depression of 1837, and there was a strong feeling that what the unemployed needed was not the workhouse but short-term relief to tide them over. By 1838, 573 Poor Law Unions had been formed in England and Wales, incorporating 13,427 parishes, but it was not until 1868 that unions were established across the entire country: the same year that the New Poor Law was applied to the Gilbert Unions.

Despite the intentions behind the 1834 Act, relief of the poor remained the responsibility of local taxpayers, and there was thus a powerful economic incentive to use loopholes such as sickness in the family to continue with outdoor relief; the weekly cost per person was about half that of providing workhouse accommodation. Outdoor relief was further restricted by the terms of the 1844 Outdoor Relief Prohibitory Order, which aimed to end it altogether for the able-bodied poor. In 1846, of 1.33 million paupers only 199,000 were maintained in workhouses, of whom 82,000 were considered to be able-bodied, leaving an estimated 375,000 of the able-bodied on outdoor relief. Excluding periods of extreme economic distress, it has been estimated that about 6.5% of the British population may have been accommodated in workhouses at any given time.

Early Victorian workhouses

The New Poor Law Commissioners were very critical of existing workhouses, and generally insisted that they be replaced. They complained in particular that "in by far the greater number of cases, it is a large almshouse, in which the young are trained in idleness, ignorance, and vice; the able-bodied maintained in sluggish sensual indolence; the aged and more respectable exposed to all the misery that is incident to dwelling in such a society".

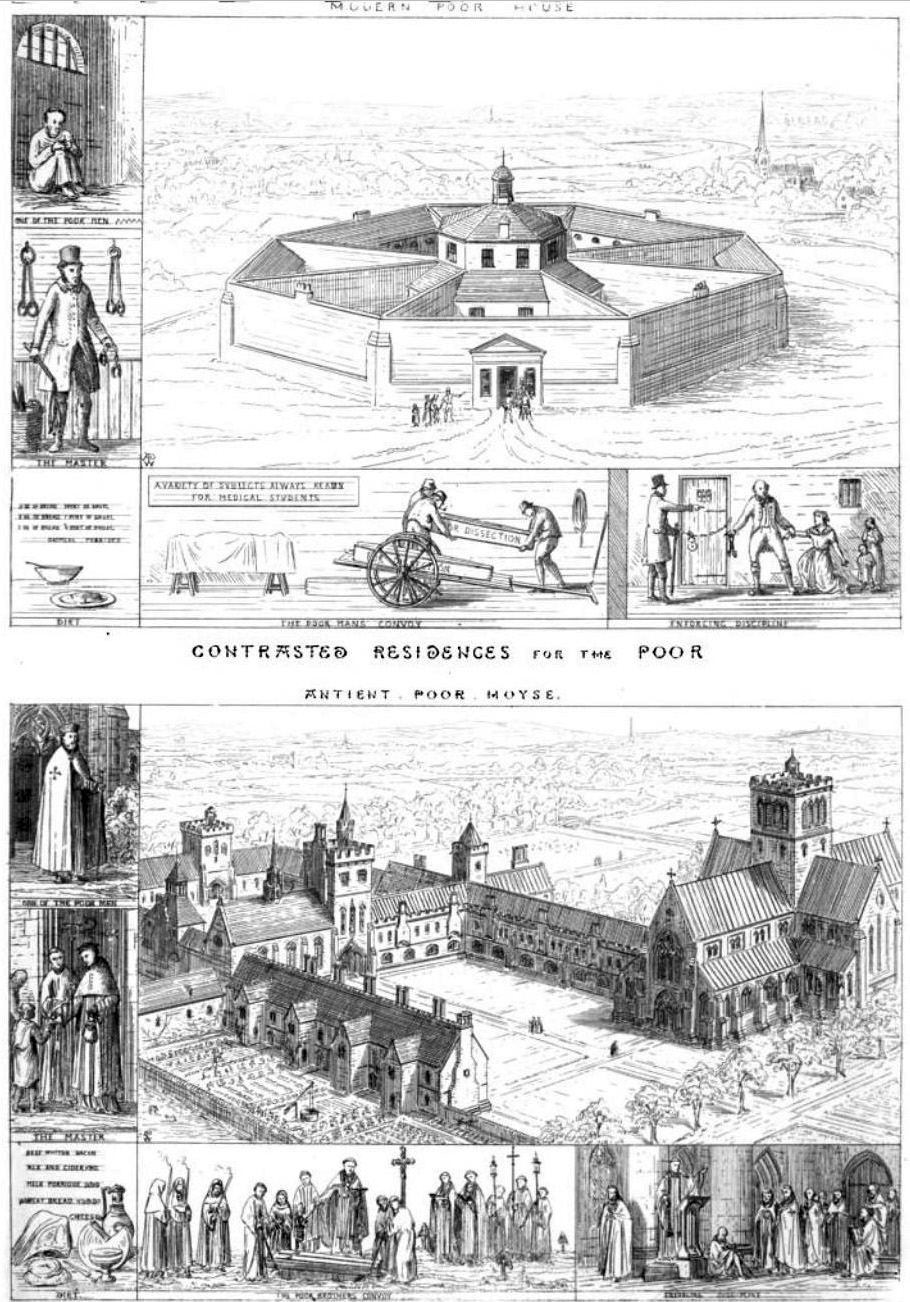

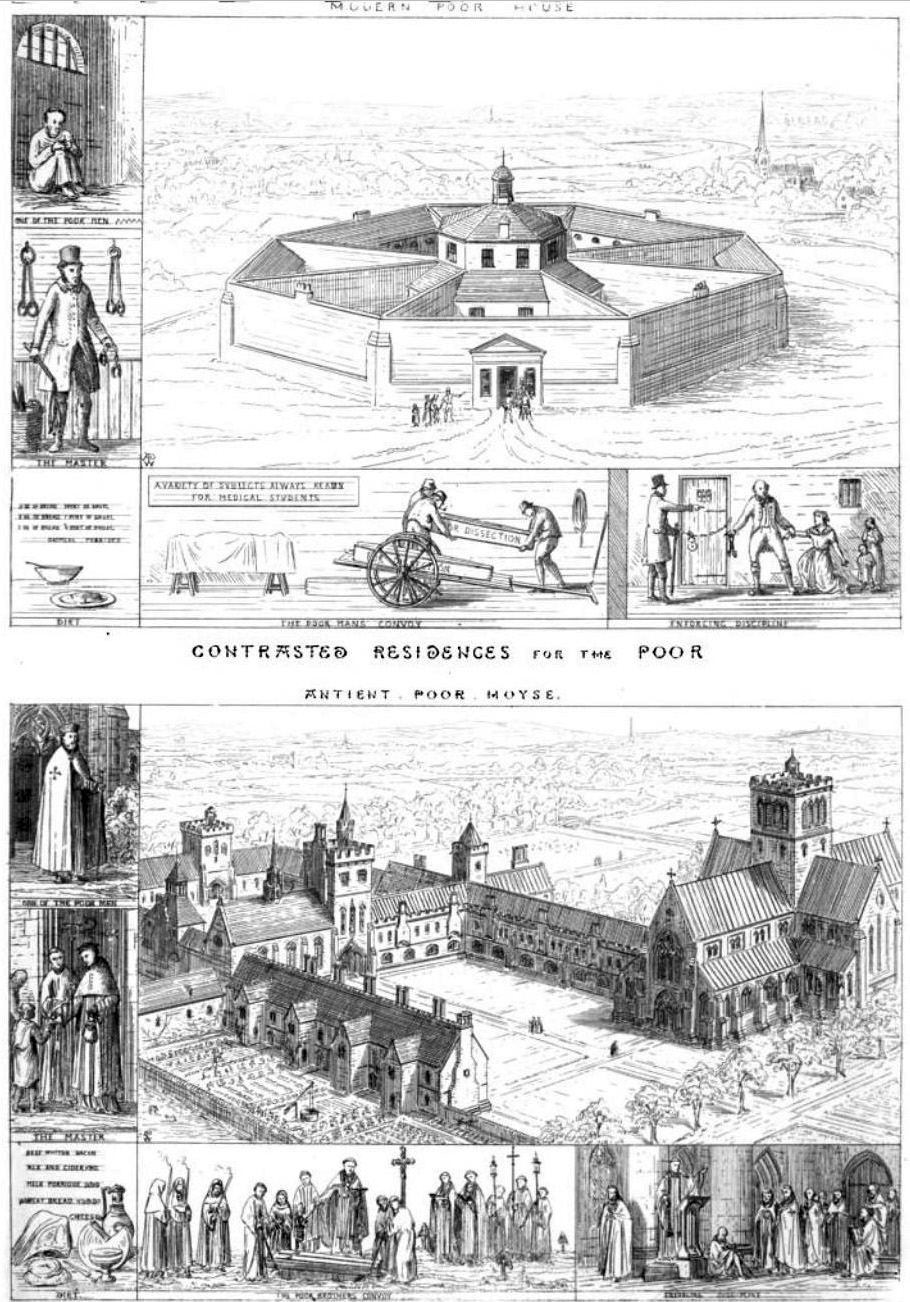

After 1835 many workhouses were constructed with the central buildings surrounded by work and exercise yards enclosed behind brick walls, so-called "pauper bastilles". The commission proposed that all new workhouses should allow for the segregation of paupers into at least four distinct groups, each to be housed separately: the aged and impotent, children, able-bodied males, and able-bodied females. A common layout resembled

The New Poor Law Commissioners were very critical of existing workhouses, and generally insisted that they be replaced. They complained in particular that "in by far the greater number of cases, it is a large almshouse, in which the young are trained in idleness, ignorance, and vice; the able-bodied maintained in sluggish sensual indolence; the aged and more respectable exposed to all the misery that is incident to dwelling in such a society".

After 1835 many workhouses were constructed with the central buildings surrounded by work and exercise yards enclosed behind brick walls, so-called "pauper bastilles". The commission proposed that all new workhouses should allow for the segregation of paupers into at least four distinct groups, each to be housed separately: the aged and impotent, children, able-bodied males, and able-bodied females. A common layout resembled Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

's prison panopticon

The panopticon is a type of institutional building and a system of control designed by the English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the 18th century. The concept of the design is to allow all prisoners of an institution to be o ...

, a radial design with four three-storey buildings at its centre set within a rectangular courtyard, the perimeter of which was defined by a three-storey entrance block and single-storey outbuildings, all enclosed by a wall. That basic layout, one of two designed by the architect Sampson Kempthorne

Sampson Kempthorne (1809–1873) was an English architect who specialised in the design of workhouses, before his emigration to New Zealand.

Life

He was the son of Rev. John Kempthorne. He began practising in Carlton Chambers on Regent Street ...

(his other design was octagonal with a segmented interior, sometimes known as the Kempthorne star), allowed for four separate work and exercise yards, one for each class of inmate. Separating the inmates was intended to serve three purposes: to direct treatment to those who most needed it; to deter others from pauperism; and as a physical barrier against illness, physical and mental.

The commissioners argued that buildings based on Kempthorne's plans would be symbolic of the recent changes to the provision of poor relief; one assistant commissioner expressed the view that they would be something "the pauper would feel it was utterly impossible to contend against", and "give confidence to the Poor Law Guardians". Another assistant commissioner claimed the new design was intended as a "terror to the able-bodied population", but the architect George Gilbert Scott

Sir George Gilbert Scott (13 July 1811 – 27 March 1878), known as Sir Gilbert Scott, was a prolific English Gothic Revival architect, chiefly associated with the design, building and renovation of churches and cathedrals, although he started ...

was critical of what he called "a set of ready-made designs of the meanest possible character". Some critics of the new Poor Law noted the similarities between Kempthorne's plans and model prisons, and doubted that they were merely coincidental - Richard Oastler

Richard Oastler (20 December 1789 – 22 August 1861) was a "Tory radical", an active opponent of Catholic Emancipation and Parliamentary Reform and a lifelong admirer of the Duke of Wellington; but also an abolitionist and prominent in the ...

went as far as referring to the institutions as 'prisons for the poor'. Augustus Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 181214 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and, ultimately, Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival st ...

compared Kempthorne's octagonal plan with the "antient poor hoyse", in what Felix Driver calls a "romantic, conservative critique" of the "degeneration of English moral and aesthetic values".

By the 1840s some of the enthusiasm for Kempthorne's designs had waned. With limited space in built-up areas, and concerns over the ventilation of buildings, some unions moved away from panopticon designs. Between 1840 and 1870 about 150 workhouses with separate blocks designed for specific functions were built. Typically the entrance building contained offices, while the main workhouse building housed the various wards and workrooms, all linked by long corridors designed to improve ventilation and lighting. Where possible, each building was separated by an exercise yard, for the use of a specific category of pauper.

Admission and discharge

Each Poor Law Union employed one or more relieving officers, whose job it was to visit those applying for assistance and assess what relief, if any, they should be given. Any applicants considered to be in need of immediate assistance could be issued with a note admitting them directly to the workhouse. Alternatively they might be offered any necessary money or goods to tide them over until the next meeting of the guardians, who would decide on the appropriate level of support and whether or not the applicants should be assigned to the workhouse.

Workhouses were designed with only a single entrance guarded by a porter, through which inmates and visitors alike had to pass. Near to the entrance were the casual wards for tramps and vagrants and the relieving rooms, where paupers were housed until they had been examined by a medical officer. After being assessed the paupers were separated and allocated to the appropriate ward for their category: boys under 14, able-bodied men between 14 and 60, men over 60, girls under 14, able-bodied women between 14 and 60, and women over 60. Children under the age of two were allowed to remain with their mothers, but by entering a workhouse paupers were considered to have forfeited responsibility for their families. Clothing and personal possessions were taken from them and stored, to be returned on their discharge. After bathing, they were issued with a distinctive uniform: for men it might be a striped cotton shirt, jacket and trousers, and a cloth cap, and for women a blue-and-white striped dress worn underneath a smock. Shoes were also provided. In some establishments certain categories of inmate were marked out by their clothing; for example, at Bristol Incorporation workhouse, prostitutes were required to wear a yellow dress and pregnant single women a red dress; such practices were deprecated by the Poor Law Commission in a directive issued in 1839 entitled "Ignominious Dress for Unchaste Women in Workhouses", but they continued until at least 1866. Some workhouses had a separate "foul" or "itch" ward, where inmates diagnosed with skin diseases such as

Each Poor Law Union employed one or more relieving officers, whose job it was to visit those applying for assistance and assess what relief, if any, they should be given. Any applicants considered to be in need of immediate assistance could be issued with a note admitting them directly to the workhouse. Alternatively they might be offered any necessary money or goods to tide them over until the next meeting of the guardians, who would decide on the appropriate level of support and whether or not the applicants should be assigned to the workhouse.

Workhouses were designed with only a single entrance guarded by a porter, through which inmates and visitors alike had to pass. Near to the entrance were the casual wards for tramps and vagrants and the relieving rooms, where paupers were housed until they had been examined by a medical officer. After being assessed the paupers were separated and allocated to the appropriate ward for their category: boys under 14, able-bodied men between 14 and 60, men over 60, girls under 14, able-bodied women between 14 and 60, and women over 60. Children under the age of two were allowed to remain with their mothers, but by entering a workhouse paupers were considered to have forfeited responsibility for their families. Clothing and personal possessions were taken from them and stored, to be returned on their discharge. After bathing, they were issued with a distinctive uniform: for men it might be a striped cotton shirt, jacket and trousers, and a cloth cap, and for women a blue-and-white striped dress worn underneath a smock. Shoes were also provided. In some establishments certain categories of inmate were marked out by their clothing; for example, at Bristol Incorporation workhouse, prostitutes were required to wear a yellow dress and pregnant single women a red dress; such practices were deprecated by the Poor Law Commission in a directive issued in 1839 entitled "Ignominious Dress for Unchaste Women in Workhouses", but they continued until at least 1866. Some workhouses had a separate "foul" or "itch" ward, where inmates diagnosed with skin diseases such as scabies

Scabies (; also sometimes known as the seven-year itch) is a contagious skin infestation by the mite ''Sarcoptes scabiei''. The most common symptoms are severe itchiness and a pimple-like rash. Occasionally, tiny burrows may appear on the skin ...

could be detained before entering the workhouse proper. Also not to be overlooked were unfortunate destitute sufferers of mental health disorders, who would be ordered to enter the workhouse by the parish doctor. The Lunacy Act 1853

Lunacy may refer to:

* Lunacy, the condition suffered by a lunatic, now used only informally

* Lunacy (film), ''Lunacy'' (film), a 2005 Jan Švankmajer film

* Lunacy (video game), ''Lunacy'' (video game), a video game for the Sega Saturn video gam ...

did promote the asylum as the institution of choice for patients afflicted with all forms of mental illness. However, in reality, destitute people suffering from mental illness would be housed in their local workhouse.

Conditions in the casual wards were worse than in the relieving rooms, and deliberately designed to discourage vagrants, who were considered potential troublemakers and probably disease-ridden. Vagrants who presented themselves at the door of a workhouse were at the mercy of the porter, whose decision it was whether or not to allocate them a bed for the night in the casual ward. Those refused entry risked being sentenced to two weeks of hard labour if they were found begging or sleeping in the open and prosecuted for an offence under the

Conditions in the casual wards were worse than in the relieving rooms, and deliberately designed to discourage vagrants, who were considered potential troublemakers and probably disease-ridden. Vagrants who presented themselves at the door of a workhouse were at the mercy of the porter, whose decision it was whether or not to allocate them a bed for the night in the casual ward. Those refused entry risked being sentenced to two weeks of hard labour if they were found begging or sleeping in the open and prosecuted for an offence under the Vagrancy Act 1824

The Vagrancy Act 1824 (5 Geo. 4. c. 83) is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom that makes it an offence to sleep rough or beg in England and Wales. It is still mostly in force and enforceable.

Critics, including William Wilberforce, c ...

.

A typical early 19th-century casual ward was a single large room furnished with some kind of bedding and perhaps a bucket in the middle of the floor for sanitation. The bedding on offer could be very basic: the Poor Law authorities in Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

in London in the mid-1840s provided only straw and rags, although beds were available for the sick. In return for their night's accommodation vagrants might be expected to undertake a certain amount of work before leaving the next day; for instance at Guisborough

Guisborough ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the borough of Redcar and Cleveland, North Yorkshire, England. It lies north of the North York Moors National Park. Roseberry Topping, midway between the town and Great Ayton, is a landmark i ...

men were required to break stones for three hours and women to pick oakum, two hours before breakfast and one after. Until the passage of the Casual Poor Act 1882

Casual or Casuals may refer to:

*Casual wear, a loosely defined dress code

**Business casual a loosely defined dress code

**Smart casual a loosely defined dress code

*Casual Company, term used by the United States military to describe a type of fo ...

vagrants could discharge themselves before 11 am on the day following their admission, but from 1883 onwards they were required to be detained until 9 am on the second day. Those who were admitted to the workhouse again within one month were required to be detained until the fourth day after their admission.

Inmates were free to leave whenever they wished after giving reasonable notice, generally considered to be three hours, but if a parent discharged him- or herself then the children were also discharged, to prevent them from being abandoned. The comic actor Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is consider ...

, who spent some time with his mother in Lambeth

Lambeth () is a district in South London, England, in the London Borough of Lambeth, historically in the County of Surrey. It is situated south of Charing Cross. The population of the London Borough of Lambeth was 303,086 in 2011. The area expe ...

workhouse, records in his autobiography that when he and his half-brother returned to the workhouse after having been sent to a school in Hanwell

Hanwell () is a town in the London Borough of Ealing, in the historic County of Middlesex, England. It is about 1.5 miles west of Ealing Broadway and had a population of 28,768 as of 2011. It is the westernmost location of the London post t ...

, he was met at the gate by his mother Hannah, dressed in her own clothes. Desperate to see them again she had discharged herself and the children; they spent the day together playing in Kennington Park

Kennington Park is a public park in Kennington, south London and lies between Kennington Park Road and St. Agnes Place. It was opened in 1854 on the site of what had been Kennington Common, where the Chartists gathered for their biggest "mons ...

and visiting a coffee shop, after which she readmitted them all to the workhouse.

Available data surrounding death rates within the workhouse system is minimal; however, in the Wall to Wall documentary ''Secrets from the Workhouse'', it's estimated that 10% of those admitted to the workhouse after the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act died within the system.

Work

Some Poor Law authorities hoped that payment for the work undertaken by the inmates would produce a profit for their workhouses, or at least allow them to be self-supporting, but whatever small income could be produced never matched the running costs. In the 18th century, inmates were poorly managed, and lacked either the inclination or the skills to compete effectively with free market industries such as spinning and weaving. Some workhouses operated not as places of employment, but as houses of correction, a role similar to that trialled by Buckinghamshire magistrateMatthew Marryott

Matthew may refer to:

* Matthew (given name)

* Matthew (surname)

* ''Matthew'' (ship), the replica of the ship sailed by John Cabot in 1497

* ''Matthew'' (album), a 2000 album by rapper Kool Keith

* Matthew (elm cultivar), a cultivar of the Chi ...

. Between 1714 and 1722 he experimented with using the workhouse as a test of poverty rather than a source of profit, leading to the establishment of a large number of workhouses for that purpose. Nevertheless, local people became concerned about the competition to their businesses from cheap workhouse labour. As late as 1888, for instance, the Firewood Cutters Protection Association was complaining that the livelihood of its members was being threatened by the cheap firewood on offer from the workhouses in the East End of London.

Many inmates were allocated tasks in the workhouse such as caring for the sick or teaching that were beyond their capabilities, but most were employed on "generally pointless" work, such as breaking stones or removing the hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a botanical class of ''Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial or medicinal use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants o ...

from telegraph wires. Others picked oakum

Oakum is a preparation of tarred fibre used to seal gaps. Its main traditional applications were in shipbuilding, for caulking or packing the joints of timbers in wooden vessels and the deck planking of iron and steel ships; in plumbing, for s ...

using a large metal nail known as a spike, which may be the source of the workhouse's nickname. Bone-crushing, useful in the creation of fertiliser

A fertilizer (American English) or fertiliser (British English; see spelling differences) is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or to plant tissues to supply plant nutrients. Fertilizers may be distinct from ...

, was a task most inmates could perform, until a government inquiry into conditions in the Andover workhouse in 1845 found that starving paupers were reduced to fighting over the rotting bones they were supposed to be grinding, to suck out the marrow. The resulting scandal led to the withdrawal of bone-crushing as an employment in workhouses and the replacement of the Poor Law Commission by the Poor Law Board The Poor Law Board was established in the United Kingdom in 1847 as a successor body to the Poor Law Commission overseeing the administration of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834. The new body was headed by a President, and with the Lord President of ...

in 1847. Conditions were thereafter regulated by a list of rules contained in the 1847 Consolidated General Order

The Consolidated General Order was a book of workhouse regulations which governed how workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In S ...

, which included guidance on issues such as diet, staff duties, dress, education, discipline, and redress of grievances.

Some Poor Law Unions opted to send destitute children to the British colonies, in particular to Canada and Australia, where it was hoped the fruits of their labour would contribute to the defence of the empire and enable the colonies to buy more British exports. Known as Home Children

Home Children was the child migration scheme founded by Annie MacPherson in 1869, under which more than 100,000 children were sent from the United Kingdom to Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa. The programme was largely discontinu ...

, the Philanthropic Farm school alone sent more than 1000 boys to the colonies between 1850 and 1871, many of them taken from workhouses. In 1869 Maria Rye

Maria Susan Rye, (31 March 1829 – 12 November 1903), was a social reformer and a promoter of emigration from England, especially of young women living in Liverpool workhouses, to the colonies of the British Empire, especially Canada.

Early life

...

and Annie Macpherson, "two spinster ladies of strong resolve", began taking groups of orphans and children from workhouses to Canada, most of whom were taken in by farming families in Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

. The Canadian government paid a small fee to the ladies for each child delivered, but most of the cost was met by charities or the Poor Law Unions.

As far as possible, elderly inmates were expected to undertake the same kind of work as the younger men and women, although concessions were made to their relative frailty. Or they might be required to chop firewood, clean the wards, or carry out other domestic tasks. In 1882 Lady Brabazon, later the Countess of Meath

County Meath (; gle, Contae na Mí or simply ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in the Eastern and Midland Region of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster. It is bordered by County Dublin, Dublin to ...

, set up a project to provide alternative occupation for non-able-bodied inmates, known as the Brabazon scheme

The Brabazon scheme was initiated in 1882 by Lady Brabazon, later the Countess of Meath, to provide occupation for the non-able-bodied inmates of workhouses in crafts such as knitting, embroidery and lace making. Training in the various crafts was ...

. Volunteers provided training in crafts such as knitting, embroidery and lace making, all costs initially being borne by Lady Brabazon herself. Although slow to take off, when workhouses discovered that the goods being produced were saleable and could make the enterprise self-financing, the scheme gradually spread across the country, and by 1897 there were more than 100 branches.

Diet

In 1836 the Poor Law Commission distributed six diets for workhouse inmates, one of which was to be chosen by each Poor Law Union depending on its local circumstances. Although dreary, the food was generally nutritionally adequate, and according to contemporary records was prepared with great care. Issues such as training staff to serve and weigh portions were well understood. The diets included general guidance, as well as schedules for each class of inmate. They were laid out on a weekly rotation, the various meals selected on a daily basis, from a list of foodstuffs. For instance, a breakfast of bread and

In 1836 the Poor Law Commission distributed six diets for workhouse inmates, one of which was to be chosen by each Poor Law Union depending on its local circumstances. Although dreary, the food was generally nutritionally adequate, and according to contemporary records was prepared with great care. Issues such as training staff to serve and weigh portions were well understood. The diets included general guidance, as well as schedules for each class of inmate. They were laid out on a weekly rotation, the various meals selected on a daily basis, from a list of foodstuffs. For instance, a breakfast of bread and gruel

Gruel is a food consisting of some type of cereal—such as ground oats, wheat, rye, or rice—heated or boiled in water or milk. It is a thinner version of porridge that may be more often drunk rather than eaten. Historically, gruel has been a ...

was followed by dinner, which might consist of cooked meats, pickled pork or bacon with vegetables, potatoes, yeast dumpling

Dumpling is a broad class of dishes that consist of pieces of dough (made from a variety of starch sources), oftentimes wrapped around a filling. The dough can be based on bread, flour, buckwheat or potatoes, and may be filled with meat, fi ...

, soup and suet

Suet is the raw, hard fat of beef, lamb or mutton found around the loins and kidneys.

Suet has a melting point of between 45 °C and 50 °C (113 °F and 122 °F) and congelation between 37 °C and 40 °C (98.6&nbs ...

, or rice pudding

Rice pudding is a dish made from rice mixed with water or milk and other ingredients such as cinnamon, vanilla and raisins.

Variants are used for either desserts or dinners. When used as a dessert, it is commonly combined with a sweetener such ...

. Supper was normally bread, cheese and broth

Broth, also known as bouillon (), is a savory liquid made of water in which meat, fish or vegetables have been simmered for a short period of time. It can be eaten alone, but it is most commonly used to prepare other dishes, such as soups, ...

, and sometimes butter or potatoes.

The larger workhouses had separate dining rooms for males and females; workhouses without separate dining rooms would stagger the meal times to avoid any contact between the sexes.

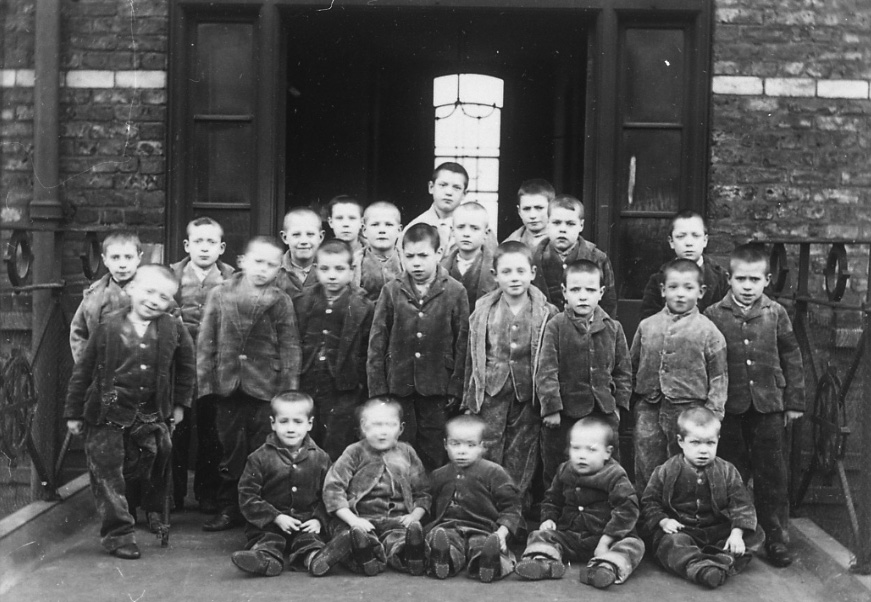

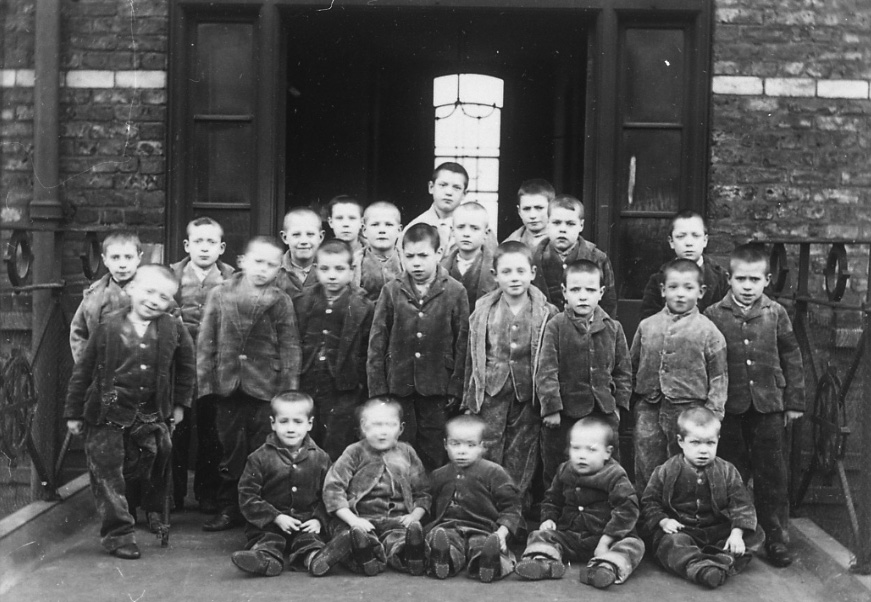

Education

Education was provided for the children, but workhouse teachers were a particular problem. Poorly paid, without any formal training, and facing large classes of unruly children with little or no interest in their lessons, few stayed in the job for more than a few months. In an effort to force workhouses to offer at least a basic level of education, legislation was passed in 1845 requiring that all pauper apprentices should be able to read and sign their own

Education was provided for the children, but workhouse teachers were a particular problem. Poorly paid, without any formal training, and facing large classes of unruly children with little or no interest in their lessons, few stayed in the job for more than a few months. In an effort to force workhouses to offer at least a basic level of education, legislation was passed in 1845 requiring that all pauper apprentices should be able to read and sign their own indenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects or covers a debt or purchase obligation. It specifically refers to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, it is an instrument used for commercia ...

papers. A training college for workhouse teachers was set up at Kneller Hall

Kneller Hall is a Grade II listed mansion in Whitton, in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. It housed the Royal Military School of Music, training musicians for the British Army, which acquired the building in the mid-19th century. I ...

in Twickenham

Twickenham is a suburban district in London, England. It is situated on the River Thames southwest of Charing Cross. Historically part of Middlesex, it has formed part of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames since 1965, and the boroug ...

during the 1840s, but it closed in the following decade.

Some children were trained in skills valuable to the area. In Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

, the boys were placed in the workhouse's workshop, while girls were tasked with spinning

Spin or spinning most often refers to:

* Spinning (textiles), the creation of yarn or thread by twisting fibers together, traditionally by hand spinning

* Spin, the rotation of an object around a central axis

* Spin (propaganda), an intentionally b ...

, making gloves and other jobs "suited to their sex, their ages and abilities". At St Martin in the Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. It is dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. There has been a church on the site since at least the mediev ...

, children were trained in spinning flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. Textiles made from flax are known in ...

, picking hair and carding

Carding is a mechanical process that disentangles, cleans and intermixes fibres to produce a continuous web or sliver (textiles), sliver suitable for subsequent processing. This is achieved by passing the fibres between differentially moving su ...

wool, before being placed as apprentices. Workhouses also had links with local industry; in Nottingham

Nottingham ( , East Midlands English, locally ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east ...

, children employed in a cotton mill earned about £60 a year for the workhouse. Some parishes advertised for apprenticeships, and were willing to pay any employer prepared to offer them. Such agreements were preferable to supporting children in the workhouse: apprenticed children were not subject to inspection by justices, thereby lowering the chance of punishment for neglect; and apprenticeships were viewed as a better long-term method of teaching skills to children who might otherwise be uninterested in work. Supporting an apprenticed child was also considerably cheaper than the workhouse or outdoor relief. Children often had no say in the matter, which could be arranged without the permission or knowledge of their parents. The supply of labour from workhouse to factory, which remained popular until the 1830s, was sometimes viewed as a form of transportation

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land (rail and road), water, cable, pipeline, ...

. While getting parish apprentices from Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell () is an area of central London, England.

Clerkenwell was an ancient parish from the mediaeval period onwards, and now forms the south-western part of the London Borough of Islington.

The well after which it was named was redisco ...

, Samuel Oldknow

Samuel Oldknow (1756–1828) was an English cotton manufacturer.

Samuel Oldknow Jnr, the eldest son of Samuel Oldknow Sr and Margery Foster, was born 5 October 1756 in Anderton, near Chorley, Lancashire, and died 18 September 1828 at Mellor ...

's agent reported how some parents came "crying to beg they may have their Children out again". Historian Arthur Redford suggests that the poor may have once shunned factories as "an insidious sort of workhouse".

Religion

Religion played an important part in workhouse life: prayers were read to the paupers before breakfast and after supper each day. Each Poor Law Union was required to appoint a chaplain to look after the spiritual needs of the workhouse inmates, and he was invariably expected to be from the establishedChurch of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

. Religious services were generally held in the dining hall, as few early workhouses had a separate chapel. But in some parts of the country, notably Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

and northern England

Northern England, also known as the North of England, the North Country, or simply the North, is the northern area of England. It broadly corresponds to the former borders of Angle Northumbria, the Anglo-Scandinavian Kingdom of Jorvik, and the ...

, there were more dissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, and ...

s than members of the established church; as section 19 of the 1834 Poor Law specifically forbade any regulation forcing an inmate to attend church services "in a Mode contrary to heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Officiall ...

Religious Principles", the commissioners were reluctantly forced to allow non-Anglicans to leave the workhouse on Sundays to attend services elsewhere, so long as they were able to provide a certificate of attendance signed by the officiating minister on their return.

As the 19th century wore on non-conformist ministers increasingly began to conduct services within the workhouse, but Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

priests were rarely welcomed. A variety of legislation had been introduced during the 17th century to limit the civil rights of Catholics, beginning with the Popish Recusants Act 1605

The Popish Recusants Act 1605 (3 Jac.1, c. 4) was an act of the Parliament of England which quickly followed the Gunpowder Plot of the same year, an attempt by English Roman Catholics to assassinate King James I and many of the Parliament.

The ...

in the wake of the failed Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was a failed assassination attempt against King James I by a group of provincial English Catholics led by Robert Catesby who sought ...

that year. Though almost all restrictions on Catholics in England and Ireland were removed by the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829

The Catholic Relief Act 1829, also known as the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1829. It was the culmination of the process of Catholic emancipation throughout the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, a great deal of anti-Catholic feeling remained. Even in areas with large Catholic populations, such as Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

, the appointment of a Catholic chaplain was unthinkable. Some guardians went so far as to refuse Catholic priests entry to the workhouse.

Discipline

Discipline was strictly enforced in the workhouse; for minor offences such as swearing or feigning sickness the "disorderly" could have their diet restricted for up to 48 hours. For more serious offences such as insubordination or violent behaviour the "refractory" could be confined for up to 24 hours, and might also have their diet restricted. Girls were punished in the same way as adults but sometimes in older cases girls were also beaten or slapped, but boys under the age of 14 could be beaten with "a rod or other instrument, such as may have been approved of by the Guardians". The persistently refractory, or anyone bringing "spirituous or fermented liquor" into the workhouse, could be taken before aJustice of the Peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

and even jailed. All punishments handed out were recorded in a punishment book, which was examined regularly by the workhouse guardians, locally elected representatives of the participating parishes with overall responsibility for the running of the workhouse.

Management and staffing

Although the commissioners were responsible for the regulatory framework within which the Poor Law Unions operated, each union was run by a locally elected board of guardians, comprising representatives from each of the participating parishes, assisted by six ''

Although the commissioners were responsible for the regulatory framework within which the Poor Law Unions operated, each union was run by a locally elected board of guardians, comprising representatives from each of the participating parishes, assisted by six ''ex officio

An ''ex officio'' member is a member of a body (notably a board, committee, council) who is part of it by virtue of holding another office. The term '' ex officio'' is Latin, meaning literally 'from the office', and the sense intended is 'by right ...

'' members. The guardians were usually farmers or tradesmen, and as one of their roles was the contracting out of the supply of goods to the workhouse, the position could prove lucrative for them and their friends. Simon Fowler has commented that "it is clear that this he awarding of contracts

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

involved much petty corruption, and it was indeed endemic throughout the Poor Law system".

Although the 1834 Act allowed for women to become workhouse guardians provided they met the property requirement, the first female was not elected until 1875. Working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

guardians were not appointed until 1892, when the property requirement was dropped in favour of occupying rented premises worth £5 a year.

Every workhouse had a complement of full-time staff, often referred to as the indoor staff. At their head was the governor or master, who was appointed by the board of guardians. His duties were laid out in a series of orders issued by the Poor Law Commissioners. As well as the overall administration of the workhouse, masters were required to discipline the paupers as necessary and to visit each ward twice daily, at 11 am and 9 pm. Female inmates and children under seven were the responsibility of the matron, as was the general housekeeping. The master and the matron were usually a married couple, charged with running the workhouse "at the minimum cost and maximum efficiency – for the lowest possible wages".

A large workhouse such as Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed ...

, accommodating several thousand paupers, employed a staff of almost 200; the smallest may only have had a porter and perhaps an assistant nurse in addition to the master and matron. A typical workhouse accommodating 225 inmates had a staff of five, which included a part-time chaplain and a part-time medical officer. The low pay meant that many medical officers were young and inexperienced. To add to their difficulties, in most unions they were obliged to pay out of their own pockets for any drugs, dressings or other medical supplies needed to treat their patients.

Later developments and abolition

A second major wave of workhouse construction began in the mid-1860s, the result of a damning report by the Poor Law inspectors on the conditions found in infirmaries in London and the provinces. Of one workhouse in

A second major wave of workhouse construction began in the mid-1860s, the result of a damning report by the Poor Law inspectors on the conditions found in infirmaries in London and the provinces. Of one workhouse in Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

, London, an inspector observed bluntly that "The workhouse does not meet the requirements of medical science, nor am I able to suggest any arrangements which would in the least enable it to do so". By the middle of the 19th century there was a growing realisation that the purpose of the workhouse was no longer solely or even chiefly to act as a deterrent to the able-bodied poor, and the first generation of buildings was widely considered to be inadequate. About 150 new workhouses were built mainly in London, Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

and Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

between 1840 and 1875, in architectural styles that began to adopt Italianate

The Italianate style was a distinct 19th-century phase in the history of Classical architecture. Like Palladianism and Neoclassicism, the Italianate style drew its inspiration from the models and architectural vocabulary of 16th-century Italian R ...

or Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personifi ...

features, to better fit into their surroundings and present a less intimidating face. One surviving example is the gateway at Ripon, designed somewhat in the style of a medieval almshouse. A major feature of this new generation of buildings is the long corridors with separate wards leading off for men, women and children.

By 1870 the architectural fashion had moved away from the corridor design in favour of a pavilion style based on the military hospitals built during and after the

By 1870 the architectural fashion had moved away from the corridor design in favour of a pavilion style based on the military hospitals built during and after the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the de ...

, providing light and well-ventilated accommodation. Opened in 1878, the Manchester Union's infirmary comprised seven parallel three-storey pavilions separated by "airing yards"; each pavilion had space for 31 beds, a day room, a nurse's kitchen and toilets. By the start of the 20th century new workhouses were often fitted out to an "impressive standard". Opened in 1903, the workhouse at Hunslet

Hunslet () is an inner-city area in south Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It is southeast of the Leeds city centre, city centre and has an industrial past.

It is situated in the Hunslet and Riverside (ward), Hunslet and Riverside ward of Lee ...

in West Riding of Yorkshire

The West Riding of Yorkshire is one of three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the administrative county County of York, West Riding (the area under the control of West Riding County Council), abbreviated County ...

had two steam boilers with automatic stokers supplying heating and hot water throughout the building, a generator to provide electricity for the institution's 1,130 electric lamps, and electric lifts in the infirmary pavilion.

As early as 1841 the Poor Law Commissioners were aware of an "insoluble dilemma" posed by the ideology behind the New Poor Law:

The education of children presented a similar dilemma. It was provided free in the workhouse but had to be paid for by the "merely poor"; free primary education

Primary education or elementary education is typically the first stage of formal education, coming after preschool/kindergarten and before secondary school. Primary education takes place in ''primary schools'', ''elementary schools'', or first ...

for all children was not provided in the UK until 1918. Instead of being "less eligible", conditions for those living in the workhouse were in certain respects "more eligible" than for those living in poverty outside.

By the late 1840s most workhouses outside London and the larger provincial towns housed only "the incapable, elderly and sick". By the end of the century only about 20 per cent of those admitted to workhouses were unemployed or destitute, but about 30 per cent of the population over 70 were in workhouses. The introduction of pensions

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

for those aged over 70 in 1908 did not reduce the number of elderly housed in workhouses, but it did reduce the number of those on outdoor relief by 25 per cent.

Responsibility for administration of the Poor Law passed to the Local Government Board

The Local Government Board (LGB) was a British Government supervisory body overseeing local administration in England and Wales from 1871 to 1919.

The LGB was created by the Local Government Board Act 1871 (C. 70) and took over the public health a ...

in 1871, and the emphasis soon shifted from the workhouse as "a receptacle for the helpless poor" to its role in the care of the sick and helpless. The Diseases Prevention Act of 1883 allowed workhouse infirmaries to offer treatment to non-paupers as well as inmates, and by the beginning of the 20th century some infirmaries were even able to operate as private hospitals.

A Royal Commission of 1905 reported that workhouses were unsuited to deal with the different categories of resident they had traditionally housed, and recommended that specialised institutions for each class of pauper should be established, in which they could be treated appropriately by properly trained staff. The "deterrent" workhouses were in future to be reserved for "incorrigibles such as drunkards, idlers and tramps". On 24 January 1918 the ''Daily Telegraph

Daily or The Daily may refer to:

Journalism

* Daily newspaper, newspaper issued on five to seven day of most weeks

* ''The Daily'' (podcast), a podcast by ''The New York Times''

* ''The Daily'' (News Corporation), a defunct US-based iPad new ...

'' reported that the Local Government Committee on the Poor Law had presented to the Ministry of Reconstruction

The Ministry of Reconstruction was a department of the United Kingdom government which existed after both World War I and World War II in order to provide for the needs of the population in the post war years.

World War I

The Ministry of Recons ...

a report recommending abolition of the workhouses and transferring their duties to other organizations.

The Local Government Act 1929

The Local Government Act 1929 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that made changes to the Poor Law and local government in England and Wales.

The Act abolished the system of poor law unions in England and Wales and their board ...

gave local authorities the power to take over workhouse infirmaries as municipal hospitals, although outside London few did so.

The workhouse system was abolished in the UK by the same Act on 1 April 1930, but many workhouses, renamed Public Assistance Institutions, continued under the control of local county councils. At the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 almost 100,000 people were accommodated in the former workhouses, 5,629 of whom were children.