abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

lecturer, novelist, playwright, and historian in the United States. Born into slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in Montgomery County, Kentucky

Montgomery County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 28,114. Its county seat is Mount Sterling. With regard to the sale of alcohol, it is classified as a moist county—a county in whi ...

, near the town of Mount Sterling, Brown escaped to Ohio in 1834 at the age of 19. He settled in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the capital city, state capital and List of municipalities in Massachusetts, most populous city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financ ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, where he worked for abolitionist causes and became a prolific writer. While working for abolition, Brown also supported causes including: temperance, women's suffrage, pacifism, prison reform, and an anti-tobacco movement. His novel ''Clotel

''Clotel; or, The President's Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States'' is an 1853 novel by United States author and playwright William Wells Brown about Clotel and her sister, fictional slave daughters of Thomas Jefferson. Brow ...

'' (1853), considered the first novel written by an African American, was published in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, England, where he resided at the time; it was later published in the United States.

Brown was a pioneer in several different literary genres, including travel writing, fiction, and drama. In 1858 he became the first published African-American playwright, and often read from this work on the lecture circuit. Following the Civil War, in 1867 he published what is considered the first history of African Americans in the Revolutionary War. He was among the first writers inducted to the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame, established in 2013. A public school was named for him in Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a city in Kentucky, United States that is the county seat of Fayette County. By population, it is the second-largest city in Kentucky and 57th-largest city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 28th-largest ...

.

Brown was lecturing in England when the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of enslaved people who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from ...

was passed in the US; as its provisions increased the risk of capture and re-enslavement, he stayed overseas for several years. He traveled throughout Europe. After his freedom was purchased in 1854 by a British couple, he and his two daughters returned to the US, where he rejoined the abolitionist lecture circuit

The "lecture circuit" is a euphemistic reference to a planned schedule of regular lectures and keynote speeches given by celebrities, often ex-politicians, for which they receive an appearance fee. In Western countries, the lecture circuit has b ...

in the North. A contemporary of Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he becam ...

, Brown was overshadowed by the charismatic orator and the two feuded publicly.

Life in slavery

A descendant of Mayflower passenger Stephen Hopkins through his father, William was born into slavery in 1814 (or March 15, 1815) nearLexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a city in Kentucky, United States that is the county seat of Fayette County. By population, it is the second-largest city in Kentucky and 57th-largest city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 28th-largest ...

, where his mother Elizabeth was a slave. She was held by Dr. John Young and had seven children, each by different fathers. (In addition to William, her children were Solomon, Leander, Benjamin, Joseph, Milford, and Elizabeth.) William was of mixed race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-eth ...

; his father was George W. Higgins, a white planter and cousin of his master Dr. Young. Higgins formally acknowledged William as his son and made Young promise not to sell him. But Young did sell the boy and his mother. In the end, William was sold several times before he was twenty years old.

His brother Joseph has been identified by researchers Ron L. Jackson Jr. and Lee Spencer White as Joe, the slave of Alamo commander William B. Travis. Joe was one of the few survivors of the battle.

William spent the majority of his youth in St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

. His masters hired him out to work on steamboats on the Missouri River, then a major thoroughfare for steamships

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

and the slave trade. His work allowed him to see many new places. In 1833, he and his mother escaped together across the Mississippi River, but they were captured in Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Roc ...

. In 1834, Brown made a second escape attempt, successfully slipping away from a steamboat when it docked in Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state lin ...

, a free state.

In freedom, he took the names of Wells Brown, a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

friend who helped him after his escape by providing food, clothes and some money. He learned to read and write, and eagerly sought more education, reading extensively to make up for what he had been deprived. Around this time he was hired by Elijah Parish Lovejoy

Elijah Parish Lovejoy (November 9, 1802 – November 7, 1837) was an American Presbyterian minister, journalist, newspaper editor, and abolitionist. Following his murder by a mob, he became a martyr to the abolitionist cause opposing slavery ...

and worked with the famed abolitionist in his printing office.Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. ''Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising''. GM Rewell & Company, 1887. pp447-450

Marriage and family

During his first year of freedom in 1834, Brown at age 20 married Elizabeth Schooner. They had two daughters who survived to adulthood: Clarissa and Josephine. William and Elizabeth later became estranged. In 1851, Elizabeth died in the United States. Brown had been in England since 1849 with their daughters, lecturing on the abolitionist circuit. After his freedom was purchased in 1854 by a British couple, Brown returned with his daughters to the US, settling in Boston. On April 12, 1860, the 46-year-old Brown married again, to 25-year-old Anna Elizabeth Gray in Boston.See confession letter published in ''The National Era'', reprinted i''The Works of William Wells Brown''

In 1856, Well's daughter Josephine Brown published ''Biography of an American Bondman'' (1856), an updated account of his life, drawing heavily on material from her father's 1847 autobiography. She added details about abuses he suffered as a slave, as well as new material about his years in Europe.

Move to New York

From 1836 to about 1845, Brown made his home inBuffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from Sou ...

, where he worked as a steamboat man on Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also has t ...

. He helped many fugitive slaves gain their freedom by hiding them on the boat to take them to Buffalo, or Detroit, Michigan

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at ...

, or across the lake to Canada. He later wrote that during the seven-month period of time from May to December 1842, he had helped 69 fugitives reach Canada. Brown became active in the abolitionist movement in Buffalo by joining several anti-slavery societies and the Colored Convention Movement. Brown's work in anti-slavery societies often included public speaking, and he frequently used music as part of his performance. Brown's use of music in his speeches emphasizes music's role in the anti-slavery movement of the 1840s. He "traveled with a slavery-themed travelling panorama". While living in Buffalo, Brown also organized a Temperance Society, which quickly gained 500 members. At the time there were only 700 black people living in Buffalo.

Years in Europe

In 1849, Brown left the United States with his two young daughters to travel in the British Isles to lecture against slavery. He wanted them to gain the education he had been denied. He was also traveling that year as a representative of the US at theInternational Peace Congress

International Peace Congress, or International Congress of the Friends of Peace, was the name of a series of international meetings of representatives from peace societies from throughout the world held in various places in Europe from 1843 to 185 ...

in Paris. Given passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern

Northern may refer to the following:

Geogra ...

in the US, which increased penalties and more severely enforced capture of fugitive slaves, he chose to stay in England until 1854. That year his freedom was purchased by British friends. As a highly visible public figure in the US, he was at risk for capture as a fugitive and re-enslavement. Slave catchers were paid high bounties to return slaves to their owners, and the new law required enforcement even by free states and their citizens, although many resisted.

Brown lectured widely to antislavery circuits in the UK to build support for the US movement. He often showed a metal slave collar as demonstration of the institution's evils. An article in the ''Scotch Independent'' reported the following:

By dint of resolution, self-culture, and force of character, he rownhas rendered himself a popular lecturer to a British audience, and vigorous expositor of the evils and atrocities of that system whose chains he has shaken off so triumphantly and forever. We may safely pronounce William Wells Brown a remarkable man, and a full refutation of the doctrine of the inferiority of the negro.Brown also used this time to learn more about the cultures, religions, and different concepts of European nations. He felt that he needed always to be learning, in order to catch up and live in a society where others had been given an education when young. In his 1852 memoir of travel in Europe, he wrote,

He who escapes from slavery at the age of twenty years, without any education, as did the writer of this letter, must read when others are asleep, if he would catch up with the rest of the world.Brown, William W. ''Three Years In Europe: Places I Have Seen And People I Have Met'', London, 1852.At the International Peace Conference in Paris, Brown faced opposition while representing the country that had enslaved him. Later he confronted American

slaveholder

The following is a list of slave owners, for which there is a consensus of historical evidence of slave ownership, in alphabetical order by last name.

A

* Adelicia Acklen (1817–1887), at one time the wealthiest woman in Tennessee, she inhe ...

s on the grounds of the Crystal Palace

Crystal Palace may refer to:

Places Canada

* Crystal Palace Complex (Dieppe), a former amusement park now a shopping complex in Dieppe, New Brunswick

* Crystal Palace Barracks, London, Ontario

* Crystal Palace (Montreal), an exhibition buildin ...

.

Based on this journey, Brown wrote ''Three Years in Europe: or Places I Have Seen And People I Have Met''. His travel account was popular with middle-class readers as he recounted sightseeing trips to the foundational monuments of European culture. In his Letter XIV, Brown wrote about his meeting with the Christian philosopher Thomas Dick in 1851.

Abolition orator and writer

After his return to the US, Brown gave lectures for the abolitionist movement in New York andMassachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

. He soon focused on anti-slavery efforts. His speeches expressed his belief in the power of moral suasion and the importance of nonviolence. He often attacked the supposed American ideal of democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

and the use of religion to promote submissiveness among slaves. Brown constantly refuted the idea of black inferiority.

Due to his reputation as a powerful orator, Brown was invited to the National Convention of Colored Citizens

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ce ...

, where he met other prominent abolitionists. When the Liberty Party formed, he chose to remain independent, believing that the abolitionist movement should avoid becoming entrenched in politics. He continued to support the Garrisonian

William Lloyd Garrison (December , 1805 – May 24, 1879) was a prominent American Christian, abolitionist, journalist, suffragist, and social reformer. He is best known for his widely read antislavery newspaper '' The Liberator'', which he found ...

approach to abolitionism. He shared his own experiences and insight into slavery in order to convince others to support the cause.

Literary works

In 1847, he published his memoir, the ''Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave, Written by Himself'', which became a bestseller across the United States, second only toFrederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he becam ...

' slave narrative

The slave narrative is a type of literary genre involving the (written) autobiographical accounts of enslaved Africans, particularly in the Americas. Over six thousand such narratives are estimated to exist; about 150 narratives were published as ...

memoir. Brown critiques his master's lack of Christian values and the customary brutal use of violence by owners in master-slave relations.

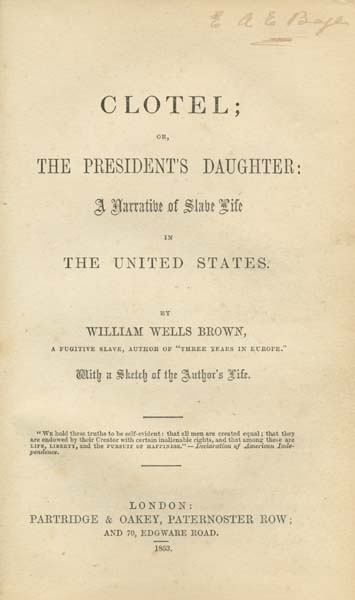

When Brown lived in Britain, he wrote more works, including travel accounts and plays. His first novel, entitled '' Clotel, or, The President's Daughter: a Narrative of Slave Life in the United States'', was published in London in 1853. It portrays the fictional plight of two

When Brown lived in Britain, he wrote more works, including travel accounts and plays. His first novel, entitled '' Clotel, or, The President's Daughter: a Narrative of Slave Life in the United States'', was published in London in 1853. It portrays the fictional plight of two mulatto

(, ) is a racial classification to refer to people of mixed African and European ancestry. Its use is considered outdated and offensive in several languages, including English and Dutch, whereas in languages such as Spanish and Portuguese ...

(mixed-race) daughters born to Thomas Jefferson and one of his slaves. His novel is believed to be the first written by an African American.

Historically, Jefferson's household was known to include numerous mixed-race slaves, and there were rumors since the early 19th century that he had children with a slave, Sally Hemings

Sarah "Sally" Hemings ( 1773 – 1835) was an enslaved woman with one-quarter African ancestry owned by president of the United States Thomas Jefferson, one of many he inherited from his father-in-law, John Wayles.

Hemings's mother Elizabet ...

. In 1826 Jefferson freed five mixed-race slaves in his will; most historians now believe that two brothers, Madison Madison may refer to:

People

* Madison (name), a given name and a surname

* James Madison (1751–1836), fourth president of the United States

Place names

* Madison, Wisconsin, the state capital of Wisconsin and the largest city known by this ...

and Eston Hemings

Eston is a Village in the borough of Redcar and Cleveland, North Yorkshire, England. The ward covering the area (as well as Lackenby, Lazenby and Wilton) had a population of 7,005 at the 2011 census. It is part of Greater Eston, which include ...

, were among his four surviving children from his long-term forced relationship with Sally Hemings."Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: A Brief Account"Monticello Website, accessed 22 June 2011, Quote: "Ten years later eferring to its 2000 report TJF

homas Jefferson Foundation

In the Vedic Hinduism, a homa (Sanskrit: होम) also known as havan, is a fire ritual performed on special occasions by a Hindu priest usually for a homeowner (" grihastha": one possessing a home). The grihasth keeps different kinds of fire ...

and most historians now believe that, years after his wife's death, Thomas Jefferson was the father of the six children of Sally Hemings mentioned in Jefferson's records, including Beverly, Harriet, Madison and Eston Hemings."

As Brown's novel was first published in England and not until later in the United States, it is not the first novel by an African American published in the US. This credit goes to either Harriet Wilson

Harriet E. Wilson (March 15, 1825 – June 28, 1900) was an African-American novelist. She was the first African American to publish a novel on the North American continent.

Her novel '' , or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black'' was p ...

's '' Our Nig'' (1859) or Julia C. Collins' ''The Curse of Caste; or The Slave Bride'' (1865).

Most scholars agree that Brown is the first published African-American playwright. Brown wrote two plays after his return to the US: ''Experience; or, How to Give a Northern Man a Backbone'' (1856, unpublished and no longer extant) and '' The Escape; or, A Leap for Freedom'' (1858). He read the latter aloud at abolitionist meetings in lieu of the typical lecture.

Brown continually struggled with how to represent slavery "as it was" to his audiences. For instance, in an 1847 lecture to the Female Anti-Slavery Society of Salem, Massachusetts, he said: "Were I about to tell you the evils of Slavery, to represent to you the Slave in his lowest degradation, I should wish to take you, one at a time, and whisper it to you. Slavery has never been represented; Slavery never can be represented."

Brown also wrote several histories, including '' The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements'' (1863); ''The Negro in the American Rebellion'' (1867), considered the first historical work about black soldiers in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of ...

; and ''The Rising Son'' (1873). His last book was another memoir, ''My Southern Home'' (1880).

Later life

Brown stayed abroad until 1854. Passage of the1850 Fugitive Slave Law

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was passed by the United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The Act was one of the most co ...

had increased his risk of capture even in the free states. Only after the Richardson family of Britain purchased his freedom in 1854 (they had done the same for Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he becam ...

), did Brown return to the United States. He quickly rejoined the anti-slavery lecture circuit.

Perhaps because of the rising social tensions in the 1850s, Brown became a proponent of African-American emigration to Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

, an independent black republic in the Caribbean since 1804. He decided that more militant actions were needed to help the abolitionist cause.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

and in the decades that followed, Brown continued to publish fiction and non-fiction books, securing his reputation as one of the most prolific African-American writers of his time. He also helped recruit blacks to fight for the Union in the Civil War. He introduced Robert John Simmons

First Sergeant Robert John Simmons was a Bermudian who served in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the American Civil War. He died in August 1863, as a result of wounds received in an attack on Fort Wagner, near Charlesto ...

from Bermuda to the abolitionist Francis George Shaw, father of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw

Robert Gould Shaw (October 10, 1837 – July 18, 1863) was an American officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Born into a prominent Boston abolitionist family, he accepted command of the first all-black regiment (the 54th Mass ...

, the commanding officer of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

While continuing to write, Brown was active in the Temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting temperance or complete abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and its leaders emph ...

as a lecturer. After studying homeopathic medicine

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths, believe that a substance that causes symptoms of a dise ...

, he opened a medical practice in Boston's South End while keeping a residence in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge beca ...

. In 1882 he moved to the nearby city of Chelsea

Chelsea or Chelsey may refer to:

Places Australia

* Chelsea, Victoria

Canada

* Chelsea, Nova Scotia

* Chelsea, Quebec

United Kingdom

* Chelsea, London, an area of London, bounded to the south by the River Thames

** Chelsea (UK Parliament const ...

.Farrison (1969), p. 402

William Wells Brown died on November 6, 1884, in Chelsea, Massachusetts, at the age of 70.

Legacy and honors

*He is the first African American to publish a novel with ''Clotel

''Clotel; or, The President's Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States'' is an 1853 novel by United States author and playwright William Wells Brown about Clotel and her sister, fictional slave daughters of Thomas Jefferson. Brow ...

, or, The President's Daughter: a Narrative of Slave Life in the United States'', in 1853 in London (Harriet Wilson

Harriet E. Wilson (March 15, 1825 – June 28, 1900) was an African-American novelist. She was the first African American to publish a novel on the North American continent.

Her novel '' , or Sketches from the Life of a Free Black'' was p ...

's '' Our Nig'', published in 1859, is the first novel published by an African American in the United States).

*An elementary school in Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is a city in Kentucky, United States that is the county seat of Fayette County. By population, it is the second-largest city in Kentucky and 57th-largest city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 28th-largest ...

, where he spent his early years, is named after him.

*He was among the first writers inducted to the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame.

*A historic marker marks the approximate location of his home in Buffalo

*Wells' portrait by Buffalo, N.Y.-based artist Edreys Wajed is one of 28 civil rights icons depicted on the Freedom Wall, commissioned by thAlbright-Knox Art Gallery

completed in September 2017.

Writings

Boston: The Anti-slavery office, 1847.

London: C. Gilpin, 1849.

London: Charles Gilpin, 1852.

Brown, William Wells (1815–1884). ''Three Years in Europe, or Places I Have Seen and People I Have Met''. with a Memoir of the author. 1852.

An Electronic Scholarly Edition, edited by Professor Christopher Mulvey

Boston: John P. Jewett, 1855.

New York: Thomas Hamilton; Boston: R.F. Wallcut, 1863.

''The Rising Son, or The Antecedents and Advancements of the Colored Race''.

Boston: A. G. Brown & Co., 1873.

Boston: A. G. Brown & Co., Publishers, 1880.

''The Negro in the American Rebellion; His Heroism and His Fidelity ...''

Footnotes

References

"William Wells Brown, Writer, and Abolitionist born"

African American Registry

William Wells Brown

Wright American Fiction, 1851–1875, Indiana University

William Wells Brown, ''CLOTEL''

An Electronic Scholarly Edition, edited by Professor Christopher Mulvey

The Louverture Project

Excerpt from ''The Black Man, His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements''.

''The Works of William Wells Brown: Using His "Strong, Manly Voice"''

edited by Paula Garrett and

Hollis Robbins

Hollis Robbins (born 1963) is an American academic and essayist; Robbins currently serves as Dean of Humanities at University of Utah. Her scholarship focuses on African-American literature.

Education and early career

Robbins was born and raised ...

. Oxford University Press, 2006.

R.J.M. Blackett, "William Wells Brown"

American National Biography Online

William E. Farrison, "William Wells Brown in Buffalo"

''The Journal of Negro History'', Vol. 39, No. 4 (October 1954), pp. 298–314, JSTOR

External links

* * * *hypertext from American Studies, University of Virginia. * The Louverture Project

William Wells Brown, "Toussaint L'Ouverture"

in ''The Black Man, His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements'' (1863). * The Louverture Project

Dessalines William Wells Brown

"

Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines (Haitian Creole: ''Jan-Jak Desalin''; ; 20 September 1758 – 17 October 1806) was a leader of the Haitian Revolution and the first ruler of an independent Haiti under the 1805 constitution. Under Dessalines, Haiti bec ...

", in ''The Black Man, His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements'' (1863).

*

*

* . (Includes discussion of ''Narrative of William Wells Brown'')

{{DEFAULTSORT:Brown, William Wells

1814 births

1884 deaths

Writers from Lexington, Kentucky

Fugitive American slaves

American expatriates in France

African-American novelists

African-American abolitionists

Abolitionists from Boston

19th-century American novelists

19th-century American historians

African-American dramatists and playwrights

Novelists from Massachusetts

People who wrote slave narratives

American temperance activists

19th-century American dramatists and playwrights

American male novelists

American male dramatists and playwrights

19th-century American male writers

Novelists from Kentucky

American pacifists

American male non-fiction writers

Historians from Massachusetts

American expatriates in the United Kingdom