William the Bastard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first

William was born in 1027 or 1028 at

William was born in 1027 or 1028 at

''History of the Monarchy'' He was the only son of

William faced several challenges on becoming duke, including his illegitimate birth and his youth: the evidence indicates that he was either seven or eight years old at the time.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 36Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 37 He enjoyed the support of his great-uncle, Archbishop Robert, as well as King

William faced several challenges on becoming duke, including his illegitimate birth and his youth: the evidence indicates that he was either seven or eight years old at the time.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 36Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 37 He enjoyed the support of his great-uncle, Archbishop Robert, as well as King  King Henry continued to support the young duke,Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 45–46 but in late 1046 opponents of William came together in a rebellion centred in lower Normandy, led by

King Henry continued to support the young duke,Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 45–46 but in late 1046 opponents of William came together in a rebellion centred in lower Normandy, led by

On the death of Hugh of Maine, Geoffrey Martel occupied Maine in a move contested by William and King Henry; eventually, they succeeded in driving Geoffrey from the county, and in the process, William had been able to secure the Bellême family strongholds at Alençon and Domfront for himself. He was thus able to assert his overlordship over the Bellême family and compel them to act consistently with Norman interests.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 59–60 However, in 1052 the king and Geoffrey Martel made common cause against William at the same time as some Norman nobles began to contest William's increasing power. Henry's about-face was probably motivated by a desire to retain dominance over Normandy, which was now threatened by William's growing mastery of his duchy.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 63–64 William was engaged in military actions against his own nobles throughout 1053,Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 66–67 as well as with the new Archbishop of Rouen, Mauger.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 64

In February 1054 the king and the Norman rebels launched a double invasion of the duchy. Henry led the main thrust through the

On the death of Hugh of Maine, Geoffrey Martel occupied Maine in a move contested by William and King Henry; eventually, they succeeded in driving Geoffrey from the county, and in the process, William had been able to secure the Bellême family strongholds at Alençon and Domfront for himself. He was thus able to assert his overlordship over the Bellême family and compel them to act consistently with Norman interests.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 59–60 However, in 1052 the king and Geoffrey Martel made common cause against William at the same time as some Norman nobles began to contest William's increasing power. Henry's about-face was probably motivated by a desire to retain dominance over Normandy, which was now threatened by William's growing mastery of his duchy.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 63–64 William was engaged in military actions against his own nobles throughout 1053,Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 66–67 as well as with the new Archbishop of Rouen, Mauger.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 64

In February 1054 the king and the Norman rebels launched a double invasion of the duchy. Henry led the main thrust through the  One factor in William's favour was his marriage to

One factor in William's favour was his marriage to

The ''

The '' In England, Earl Godwin died in 1053 and his sons were increasing in power:

In England, Earl Godwin died in 1053 and his sons were increasing in power:

Harold was crowned on 6 January 1066 in Edward's new Norman-style

Harold was crowned on 6 January 1066 in Edward's new Norman-style

William of Poitiers describes a council called by Duke William, in which the writer gives an account of a great debate that took place between William's nobles and supporters over whether to risk an invasion of England. Although some sort of formal assembly probably was held, it is unlikely that any debate took place, as the duke had by then established control over his nobles, and most of those assembled would have been anxious to secure their share of the rewards from the conquest of England.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 79–81 William of Poitiers also relates that the duke obtained the consent of Pope Alexander II for the invasion, along with a papal banner. The chronicler also claimed that the duke secured the support of

William of Poitiers describes a council called by Duke William, in which the writer gives an account of a great debate that took place between William's nobles and supporters over whether to risk an invasion of England. Although some sort of formal assembly probably was held, it is unlikely that any debate took place, as the duke had by then established control over his nobles, and most of those assembled would have been anxious to secure their share of the rewards from the conquest of England.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 79–81 William of Poitiers also relates that the duke obtained the consent of Pope Alexander II for the invasion, along with a papal banner. The chronicler also claimed that the duke secured the support of

Tostig Godwinson and Harald Hardrada invaded

Tostig Godwinson and Harald Hardrada invaded

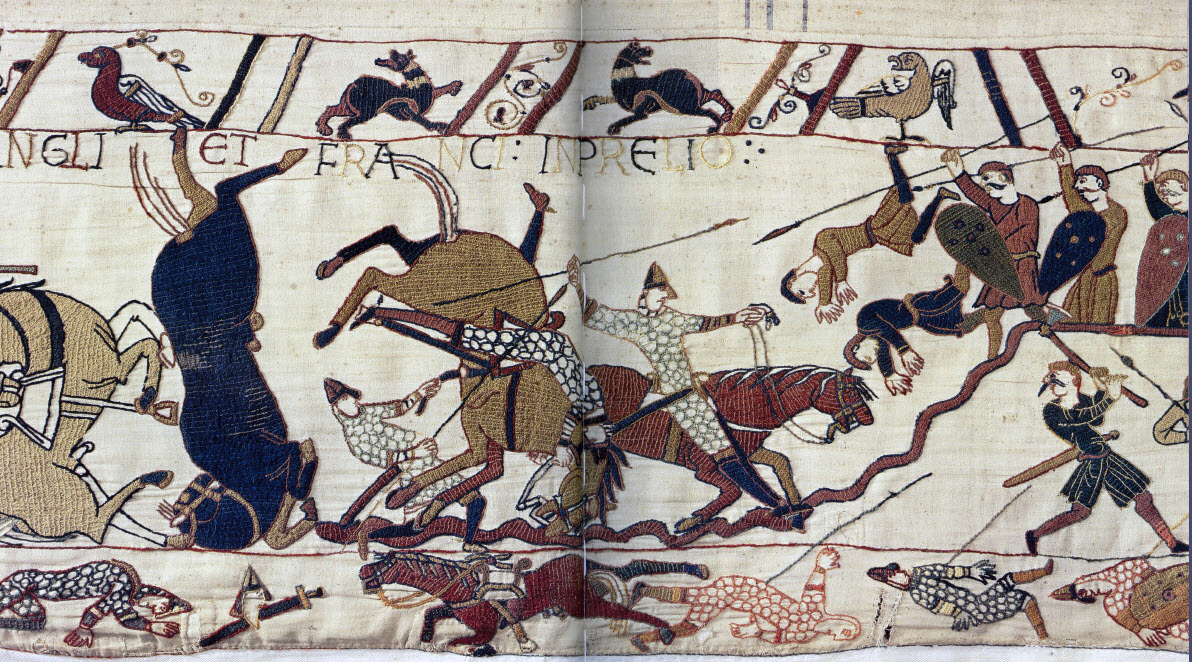

The battle began at about 9 am on 14 October and lasted all day, but while a broad outline is known, the exact events are obscured by contradictory accounts in the sources.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 126 Although the numbers on each side were about equal, William had both cavalry and infantry, including many archers, while Harold had only foot soldiers and few, if any, archers.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 73 The English soldiers formed up as a

The battle began at about 9 am on 14 October and lasted all day, but while a broad outline is known, the exact events are obscured by contradictory accounts in the sources.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 126 Although the numbers on each side were about equal, William had both cavalry and infantry, including many archers, while Harold had only foot soldiers and few, if any, archers.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 73 The English soldiers formed up as a

In 1068 Edwin and Morcar revolted, supported by

In 1068 Edwin and Morcar revolted, supported by

In 1075, during William's absence,

In 1075, during William's absence,

Word of William's defeat at Gerberoi stirred up difficulties in northern England. In August and September 1079 King Malcolm of Scots raided south of the

Word of William's defeat at Gerberoi stirred up difficulties in northern England. In August and September 1079 King Malcolm of Scots raided south of the

As part of his efforts to secure England, William ordered many

As part of his efforts to secure England, William ordered many

After 1066, William did not attempt to integrate his separate domains into one unified realm with one set of laws. His

After 1066, William did not attempt to integrate his separate domains into one unified realm with one set of laws. His

At Christmas 1085, William ordered the compilation of a survey of the landholdings held by himself and by his vassals throughout his kingdom, organised by counties. It resulted in a work now known as the ''

At Christmas 1085, William ordered the compilation of a survey of the landholdings held by himself and by his vassals throughout his kingdom, organised by counties. It resulted in a work now known as the ''

William left Normandy to Robert, and the custody of England was given to William's second surviving son, also called William, on the assumption that he would become king. The youngest son, Henry, received money. After entrusting England to his second son, the elder William sent the younger William back to England on 7 or 8 September, bearing a letter to Lanfranc ordering the archbishop to aid the new king. Other bequests included gifts to the Church and money to be distributed to the poor. William also ordered that all of his prisoners be released, including his half-brother Odo.

Disorder followed William's death; everyone who had been at his deathbed left the body at Rouen and hurried off to attend to their own affairs. Eventually, the clergy of Rouen arranged to have the body sent to Caen, where William had desired to be buried in his foundation of the Abbaye-aux-Hommes. The funeral, attended by the bishops and abbots of Normandy as well as his son Henry, was disturbed by the assertion of a citizen of Caen who alleged that his family had been illegally despoiled of the land on which the church was built. After hurried consultations, the allegation was shown to be true, and the man was compensated. A further indignity occurred when the corpse was lowered into the tomb. The corpse was too large for the space, and when attendants forced the body into the tomb it burst, spreading a disgusting odour throughout the church.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 207–208

William's grave is currently marked by a marble slab with a

William left Normandy to Robert, and the custody of England was given to William's second surviving son, also called William, on the assumption that he would become king. The youngest son, Henry, received money. After entrusting England to his second son, the elder William sent the younger William back to England on 7 or 8 September, bearing a letter to Lanfranc ordering the archbishop to aid the new king. Other bequests included gifts to the Church and money to be distributed to the poor. William also ordered that all of his prisoners be released, including his half-brother Odo.

Disorder followed William's death; everyone who had been at his deathbed left the body at Rouen and hurried off to attend to their own affairs. Eventually, the clergy of Rouen arranged to have the body sent to Caen, where William had desired to be buried in his foundation of the Abbaye-aux-Hommes. The funeral, attended by the bishops and abbots of Normandy as well as his son Henry, was disturbed by the assertion of a citizen of Caen who alleged that his family had been illegally despoiled of the land on which the church was built. After hurried consultations, the allegation was shown to be true, and the man was compensated. A further indignity occurred when the corpse was lowered into the tomb. The corpse was too large for the space, and when attendants forced the body into the tomb it burst, spreading a disgusting odour throughout the church.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 207–208

William's grave is currently marked by a marble slab with a

The immediate consequence of William's death was a war between his sons Robert and William over control of England and Normandy. Even after the younger William's death in 1100 and the succession of his youngest brother Henry as king, Normandy and England remained contested between the brothers until Robert's capture by Henry at the

The immediate consequence of William's death was a war between his sons Robert and William over control of England and Normandy. Even after the younger William's death in 1100 and the succession of his youngest brother Henry as king, Normandy and England remained contested between the brothers until Robert's capture by Henry at the

Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 1087. A descendant of Rollo

Rollo ( nrf, Rou, ''Rolloun''; non, Hrólfr; french: Rollon; died between 928 and 933) was a Viking who became the first ruler of Normandy, today a region in northern France. He emerged as the outstanding warrior among the Norsemen who had se ...

, he was Duke of Normandy from 1035 onward. By 1060, following a long struggle to establish his throne, his hold on Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

was secure. In 1066, following the death of Edward the Confessor, William invaded England, leading an army of Normans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. ...

to victory over the Anglo-Saxon forces of Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson ( – 14 October 1066), also called Harold II, was the last crowned Anglo-Saxon English king. Harold reigned from 6 January 1066 until his death at the Battle of Hastings, fighting the Norman invaders led by William the ...

at the Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings nrf, Batâle dé Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066 between the Norman-French army of William, the Duke of Normandy, and an English army under the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson, beginning the Norman Conque ...

, and suppressed subsequent English revolts in what has become known as the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Con ...

. The rest of his life was marked by struggles to consolidate his hold over England and his continental lands, and by difficulties with his eldest son, Robert Curthose

Robert Curthose, or Robert II of Normandy ( 1051 – 3 February 1134, french: Robert Courteheuse / Robert II de Normandie), was the eldest son of William the Conqueror and succeeded his father as Duke of Normandy in 1087, reigning until 1106. ...

.

William was the son of the unmarried Duke Robert I of Normandy

Robert the Magnificent (french: le Magnifique;He was also, although erroneously, said to have been called 'Robert the Devil' (french: le Diable). Robert I was never known by the nickname 'the devil' in his lifetime. 'Robert the Devil' was a fic ...

and his mistress Herleva

Herleva ( 1003 – c. 1050) was an 11th-century Norman woman known for having been mother of William the Conqueror, born to an extramarital relationship with Robert I, Duke of Normandy, and also of William's prominent half-brothers Odo of Bayeux ...

. His illegitimate status and his youth caused some difficulties for him after he succeeded his father, as did the anarchy which plagued the first years of his rule. During his childhood and adolescence, members of the Norman aristocracy battled each other, both for control of the child duke, and for their own ends. In 1047, William was able to quash a rebellion and begin to establish his authority over the duchy, a process that was not complete until about 1060. His marriage in the 1050s to Matilda of Flanders

Matilda of Flanders (french: link=no, Mathilde; nl, Machteld) ( 1031 – 2 November 1083) was Queen of England and Duchess of Normandy by marriage to William the Conqueror, and regent of Normandy during his absences from the duchy. She was ...

provided him with a powerful ally in the neighbouring county of Flanders

The County of Flanders was a historic territory in the Low Countries.

From 862 onwards, the counts of Flanders were among the original twelve peers of the Kingdom of France. For centuries, their estates around the cities of Ghent, Bruges and Yp ...

. By the time of his marriage, William was able to arrange the appointment of his supporters as bishops and abbots in the Norman church. His consolidation of power allowed him to expand his horizons, and he secured control of the neighbouring county of Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

by 1062.

In the 1050s and early 1060s, William became a contender for the throne of England held by the childless Edward the Confessor, his first cousin once removed. There were other potential claimants, including the powerful English earl Harold Godwinson, whom Edward named as king on his deathbed in January 1066. Arguing that Edward had previously promised the throne to him and that Harold had sworn to support his claim, William built a large fleet and invaded England in September 1066. He decisively defeated and killed Harold at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066. After further military efforts, William was crowned king on Christmas Day, 1066, in London. He made arrangements for the governance of England in early 1067 before returning to Normandy. Several unsuccessful rebellions followed, but William's hold was mostly secure on England by 1075, allowing him to spend the greater part of his reign in continental Europe.

William's final years were marked by difficulties in his continental domains, troubles with his son, Robert, and threatened invasions of England by the Danes. In 1086, he ordered the compilation of the ''Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manus ...

'', a survey listing all the land-holdings in England along with their pre-Conquest and current holders. He died in September 1087 while leading a campaign in northern France, and was buried in Caen. His reign in England was marked by the construction of castles, settling a new Norman nobility on the land, and change in the composition of the English clergy. He did not try to integrate his various domains into one empire but continued to administer each part separately. His lands were divided after his death: Normandy went to Robert, and England went to his second surviving son, William Rufus

William II ( xno, Williame; – 2 August 1100) was King of England from 26 September 1087 until his death in 1100, with powers over Normandy and influence in Scotland. He was less successful in extending control into Wales. The third so ...

.

Background

Norsemen

The Norsemen (or Norse people) were a North Germanic ethnolinguistic group of the Early Middle Ages, during which they spoke the Old Norse language. The language belongs to the North Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages and is the pr ...

first began raiding in what became Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

in the late 8th century. Permanent Scandinavian settlement occurred before 911, when Rollo

Rollo ( nrf, Rou, ''Rolloun''; non, Hrólfr; french: Rollon; died between 928 and 933) was a Viking who became the first ruler of Normandy, today a region in northern France. He emerged as the outstanding warrior among the Norsemen who had se ...

, one of the Viking leaders, and King Charles the Simple

Charles III (17 September 879 – 7 October 929), called the Simple or the Straightforward (from the Latin ''Carolus Simplex''), was the king of West Francia from 898 until 922 and the king of Lotharingia from 911 until 919–923. He was a mem ...

of France reached an agreement ceding the county of Rouen to Rollo. The lands around Rouen became the core of the later duchy of Normandy.Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 376–377 Normandy may have been used as a base when Scandinavian attacks on England were renewed at the end of the 10th century, which would have worsened relations between England and Normandy.Williams ''Æthelred the Unready'' pp. 42–43 In an effort to improve matters, King Æthelred the Unready

Æthelred II ( ang, Æþelræd, ;Different spellings of this king’s name most commonly found in modern texts are "Ethelred" and "Æthelred" (or "Aethelred"), the latter being closer to the original Old English form . Compare the modern diale ...

took Emma, sister of Richard II, Duke of Normandy

Richard II (died 28 August 1026), called the Good (French: ''Le Bon''), was the duke of Normandy from 996 until 1026.

Life

Richard was the eldest surviving son and heir of Richard the Fearless and Gunnor. He succeeded his father as the ruler of D ...

, as his second wife in 1002.Williams ''Æthelred the Unready'' pp. 54–55

Danish raids on England continued, and Æthelred sought help from Richard, taking refuge in Normandy in 1013 when King Swein I of Denmark drove Æthelred and his family from England. Swein's death in 1014 allowed Æthelred to return home, but Swein's son Cnut

Cnut (; ang, Cnut cyning; non, Knútr inn ríki ; or , no, Knut den mektige, sv, Knut den Store. died 12 November 1035), also known as Cnut the Great and Canute, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norwa ...

contested Æthelred's return. Æthelred died unexpectedly in 1016, and Cnut became king of England. Æthelred and Emma's two sons, Edward and Alfred

Alfred may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*''Alfred J. Kwak'', Dutch-German-Japanese anime television series

* ''Alfred'' (Arne opera), a 1740 masque by Thomas Arne

* ''Alfred'' (Dvořák), an 1870 opera by Antonín Dvořák

*"Alfred (Interlu ...

, went into exile in Normandy while their mother, Emma, became Cnut's second wife.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 80–83

After Cnut's death in 1035, the English throne fell to Harold Harefoot

Harold I (died 17 March 1040), also known as Harold Harefoot, was King of the English from 1035 to 1040. Harold's nickname "Harefoot" is first recorded as "Harefoh" or "Harefah" in the twelfth century in the history of Ely Abbey, and according ...

, his son by his first wife, while Harthacnut

Harthacnut ( da, Hardeknud; "Tough-knot"; – 8 June 1042), traditionally Hardicanute, sometimes referred to as Canute III, was King of Denmark from 1035 to 1042 and King of the English from 1040 to 1042.

Harthacnut was the son of King ...

, his son by Emma, became king in Denmark. England remained unstable. Alfred returned to England in 1036 to visit his mother and perhaps to challenge Harold as king. One story implicates Earl Godwin of Wessex

Godwin of Wessex ( ang, Godwine; – 15 April 1053) was an English nobleman who became one of the most powerful earls in Kingdom of England, England under the Denmark, Danish king Cnut the Great (King of England from 1016 to 1035) and his succ ...

in Alfred's subsequent death, but others blame Harold. Emma went into exile in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

until Harthacnut became king following Harold's death in 1040, and his half-brother Edward followed Harthacnut to England; Edward was proclaimed king after Harthacnut's death in June 1042.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 83–85

Early life

William was born in 1027 or 1028 at

William was born in 1027 or 1028 at Falaise

Falaise may refer to:

Places

* Falaise, Ardennes, France

* Falaise, Calvados, France

** The Falaise pocket was the site of a battle in the Second World War

* La Falaise, in the Yvelines ''département'', France

* The Falaise escarpment in Quebe ...

, Duchy of Normandy, most likely towards the end of 1028.William the Conqueror''History of the Monarchy'' He was the only son of

Robert I Robert I may refer to:

*Robert I, Duke of Neustria (697–748)

*Robert I of France (866–923), King of France, 922–923, rebelled against Charles the Simple

*Rollo, Duke of Normandy (c. 846 – c. 930; reigned 911–927)

* Robert I Archbishop of ...

, son of Richard II. His mother Herleva

Herleva ( 1003 – c. 1050) was an 11th-century Norman woman known for having been mother of William the Conqueror, born to an extramarital relationship with Robert I, Duke of Normandy, and also of William's prominent half-brothers Odo of Bayeux ...

was a daughter of Fulbert of Falaise; he may have been a tanner or embalmer. Herleva was possibly a member of the ducal household, but did not marry Robert. She later married Herluin de Conteville

Herluin de Conteville (1001–1066), also sometimes listed as Herlwin of Conteville, was the stepfather of William I of England, William the Conqueror, and the father of Odo of Bayeux and Robert, Count of Mortain, both of whom became prominent duri ...

, with whom she had two sons – Odo of Bayeux

Odo of Bayeux (died 1097), Earl of Kent and Bishop of Bayeux, was the maternal half-brother of William the Conqueror, and was, for a time, second in power after the King of England.

Early life

Odo was the son of William the Conqueror's mother ...

and Count Robert of Mortain

Robert, Count of Mortain, 2nd Earl of Cornwall (–) was a Norman nobleman and the half-brother (on their mother's side) of King William the Conqueror. He was one of the very few proven companions of William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hasti ...

– and a daughter whose name is unknown. One of Herleva's brothers, Walter, became a supporter and protector of William during his minority. Robert I also had a daughter, Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

, by another mistress.van Houts "Les femmes" ''Tabularia "Études"'' pp. 19–34

Robert I succeeded his elder brother Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Battl ...

as duke on 6 August 1027. The brothers had been at odds over the succession, and Richard's death was sudden. Robert was accused by some writers of killing Richard, a plausible but now unprovable charge.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 31–32 Conditions in Normandy were unsettled, as noble families despoiled the Church and Alan III of Brittany

Alan III of Rennes (c. 997 – 1 October 1040) ( French: ''Alain III de Bretagne'') was Count of Rennes and duke of Brittany, by right of succession from 1008 to his death.

Life

Alan was the son of Duke Geoffrey I and Hawise of Normandy.Detlev Sc ...

waged war against the duchy, possibly in an attempt to take control. By 1031 Robert had gathered considerable support from noblemen, many of whom would become prominent during William's life. They included the duke's uncle Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

, the archbishop of Rouen

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Rouen (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Rothomagensis''; French: ''Archidiocèse de Rouen'') is an archdiocese of the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church in France. As one of the fifteen Archbishops of France, the Ar ...

, who had originally opposed the duke; Osbern, a nephew of Gunnor

Gunnor or Gunnora ( – ) was Duchess of Normandy by marriage to Richard I of Normandy, having previously been his long-time mistress. She functioned as regent of Normandy during the absence of her spouse, as well as the adviser to him and later t ...

the wife of Richard I

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was ...

; and Gilbert of Brionne

Gilbert (or Giselbert) de Brionne, Count of Eu and of Brionne ( – ), was an influential nobleman in the Duchy of Normandy in Northern France.Robinson, J. A. (1911). Gilbert Crispin, abbot of Westminster: a study of the abbey under Norman ru ...

, a grandson of Richard I.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 32–34, 145 After his accession, Robert continued Norman support for the English princes Edward and Alfred, who were still in exile in northern France.

There are indications that Robert may have been briefly betrothed to a daughter of King Cnut, but no marriage took place. It is unclear whether William would have been supplanted in the ducal succession if Robert had had a legitimate son. Earlier dukes had been illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as ''b ...

, and William's association with his father on ducal charters appears to indicate that William was considered Robert's most likely heir. In 1034 the duke decided to go on pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

to Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

. Although some of his supporters tried to dissuade him from undertaking the journey, he convened a council in January 1035 and had the assembled Norman magnates swear fealty

An oath of fealty, from the Latin ''fidelitas'' (faithfulness), is a pledge of allegiance of one person to another.

Definition

In medieval Europe, the swearing of fealty took the form of an oath made by a vassal, or subordinate, to his lord. "Fea ...

to William as his heir before leaving for Jerusalem. He died in early July at Nicea

Nicaea, also known as Nicea or Nikaia (; ; grc-gre, Νίκαια, ) was an ancient Greek city in Bithynia, where located in northwestern Anatolia and is primarily known as the site of the First and Second Councils of Nicaea (the first and sev ...

, on his way back to Normandy.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 35–37

Duke of Normandy

Challenges

Henry I of France

Henry I (4 May 1008 – 4 August 1060) was King of the Franks from 1031 to 1060. The royal demesne of France reached its smallest size during his reign, and for this reason he is often seen as emblematic of the weakness of the early Capetians. Th ...

, enabling him to succeed to his father's duchy. The support given to the exiled English princes in their attempt to return to England in 1036 shows that the new duke's guardians were attempting to continue his father's policies, but Archbishop Robert's death in March 1037 removed one of William's main supporters, and conditions in Normandy quickly descended into chaos.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 38–39

The anarchy in the duchy lasted until 1047,Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 51 and control of the young duke was one of the priorities of those contending for power. At first, Alan of Brittany had custody of the duke, but when Alan died in either late 1039 or October 1040, Gilbert of Brionne took charge of William. Gilbert was killed within months, and another guardian, Turchetil, was also killed around the time of Gilbert's death.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 40 Yet another guardian, Osbern, was slain in the early 1040s in William's chamber while the duke slept. It was said that Walter, William's maternal uncle, was occasionally forced to hide the young duke in the houses of peasants,Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 37 although this story may be an embellishment by Orderic Vitalis

Orderic Vitalis ( la, Ordericus Vitalis; 16 February 1075 – ) was an English chronicler and Benedictine monk who wrote one of the great contemporary chronicles of 11th- and 12th-century Normandy and Anglo-Norman England. Modern historia ...

. The historian Eleanor Searle speculates that William was raised with the three cousins who later became important in his career – William fitzOsbern

William FitzOsbern, 1st Earl of Hereford, Lord of Breteuil ( 1011 – 22 February 1071), was a relative and close counsellor of William the Conqueror and one of the great magnates of early Norman England. FitzOsbern was created Earl of Hereford ...

, Roger de Beaumont

Roger de Beaumont (c. 1015 – 29 November 1094), feudal lord (French: ''seigneur'') of Beaumont-le-Roger and of Pont-Audemer in Normandy, was a powerful Norman nobleman and close advisor to William the Conqueror.

−

Origins

Roger wa ...

, and Roger of Montgomery

Roger de Montgomery (died 1094), also known as Roger the Great, was the first Earl of Shrewsbury, and Earl of Arundel, in Sussex. His father was Roger de Montgomery, seigneur of Montgomery, a member of the House of Montgomerie, and was probably ...

.Searle ''Predatory Kinship'' pp. 196–198 Although many of the Norman nobles engaged in their own private wars and feuds during William's minority, the viscounts still acknowledged the ducal government, and the ecclesiastical hierarchy was supportive of William.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 42–43

King Henry continued to support the young duke,Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 45–46 but in late 1046 opponents of William came together in a rebellion centred in lower Normandy, led by

King Henry continued to support the young duke,Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 45–46 but in late 1046 opponents of William came together in a rebellion centred in lower Normandy, led by Guy of Burgundy Guy of Burgundy, also known as Guy of Brionne, was a member of the House of Ivrea with a claim to the Duchy of Normandy. He held extensive land from his cousin, Duke William the Bastard, but lost it following his unsuccessful rebellion in the late 1 ...

with support from Nigel, Viscount of the Cotentin, and Ranulf, Viscount of the Bessin. According to stories that may have legendary elements, an attempt was made to seize William at Valognes, but he escaped under cover of darkness, seeking refuge with King Henry.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 47–49 In early 1047 Henry and William returned to Normandy and were victorious at the Battle of Val-ès-Dunes near Caen, although few details of the actual fighting are recorded.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 38 William of Poitiers claimed that the battle was won mainly through William's efforts, but earlier accounts claim that King Henry's men and leadership also played an important part. William assumed power in Normandy, and shortly after the battle promulgated the Truce of God

The Peace and Truce of God ( lat, Pax et treuga Dei) was a movement in the Middle Ages led by the Catholic Church and one of the most influential mass peace movements in history. The goal of both the ''Pax Dei'' and the ''Treuga Dei'' was to limit ...

throughout his duchy, in an effort to limit warfare and violence by restricting the days of the year on which fighting was permitted.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 40 Although the Battle of Val-ès-Dunes marked a turning point in William's control of the duchy, it was not the end of his struggle to gain the upper hand over the nobility. The period from 1047 to 1054 saw almost continuous warfare, with lesser crises continuing until 1060.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 53

Consolidation of power

William's next efforts were against Guy of Burgundy, who retreated to his castle atBrionne

Brionne () is a commune in the Eure department. Brionne is in the region of Normandy of northern France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of oversea ...

, which William besieged. After a long effort, the duke succeeded in exiling Guy in 1050.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 54–55 To address the growing power of the Count of Anjou Anjou may refer to:

Geography and titles France

* County of Anjou, a historical county in France and predecessor of the Duchy of Anjou

**Count of Anjou, title of nobility

*Duchy of Anjou, a historical duchy and later a province of France

**Duk ...

, Geoffrey Martel Geoffrey, Geoffroy, Geoff, etc., may refer to:

People

* Geoffrey (name), including a list of people with the name

* Geoffroy (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1095–c. 1155), clergyman and one of the ...

, William joined with King Henry in a campaign against him, the last known cooperation between the two. They succeeded in capturing an Angevin fortress but accomplished little else.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 43–44 Geoffrey attempted to expand his authority into the county of Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and ...

, especially after the death of Hugh IV of Maine

Hugh IV (died 25 March 1051) was Count of Maine from 1036 to 1051.

Life

Hugh was the son of Herbert I, Count of Maine,Detlev Schwennicke, '' Europäische Stammtafeln: Stammtafeln zur Geschichte der Europäischen Staaten'', Neue Folge, Band III T ...

in 1051. Central to the control of Maine were the holdings of the Bellême family, who held Bellême

Bellême () is a commune in the Orne department in northwestern France. The musicologist Guillaume André Villoteau (1759–1839) was born in Bellême, as was Aristide Boucicaut (1810-1877), owner of ''Le'' ''Bon Marché'', the world's first de ...

on the border of Maine and Normandy, as well as the fortresses at Alençon

Alençon (, , ; nrf, Alençoun) is a commune in Normandy, France, capital of the Orne department. It is situated west of Paris. Alençon belongs to the intercommunality of Alençon (with 52,000 people).

History

The name of Alençon is firs ...

and Domfront. Bellême's overlord was the king of France, but Domfront was under the overlordship of Geoffrey Martel and Duke William was Alençon's overlord. The Bellême family, whose lands were quite strategically placed between their three different overlords, were able to play each of them against the other and secure virtual independence for themselves.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 56–58

On the death of Hugh of Maine, Geoffrey Martel occupied Maine in a move contested by William and King Henry; eventually, they succeeded in driving Geoffrey from the county, and in the process, William had been able to secure the Bellême family strongholds at Alençon and Domfront for himself. He was thus able to assert his overlordship over the Bellême family and compel them to act consistently with Norman interests.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 59–60 However, in 1052 the king and Geoffrey Martel made common cause against William at the same time as some Norman nobles began to contest William's increasing power. Henry's about-face was probably motivated by a desire to retain dominance over Normandy, which was now threatened by William's growing mastery of his duchy.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 63–64 William was engaged in military actions against his own nobles throughout 1053,Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 66–67 as well as with the new Archbishop of Rouen, Mauger.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 64

In February 1054 the king and the Norman rebels launched a double invasion of the duchy. Henry led the main thrust through the

On the death of Hugh of Maine, Geoffrey Martel occupied Maine in a move contested by William and King Henry; eventually, they succeeded in driving Geoffrey from the county, and in the process, William had been able to secure the Bellême family strongholds at Alençon and Domfront for himself. He was thus able to assert his overlordship over the Bellême family and compel them to act consistently with Norman interests.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 59–60 However, in 1052 the king and Geoffrey Martel made common cause against William at the same time as some Norman nobles began to contest William's increasing power. Henry's about-face was probably motivated by a desire to retain dominance over Normandy, which was now threatened by William's growing mastery of his duchy.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 63–64 William was engaged in military actions against his own nobles throughout 1053,Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 66–67 as well as with the new Archbishop of Rouen, Mauger.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 64

In February 1054 the king and the Norman rebels launched a double invasion of the duchy. Henry led the main thrust through the county of Évreux

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

, while the other wing, under the king's brother Odo, invaded eastern Normandy.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 67 William met the invasion by dividing his forces into two groups. The first, which he led, faced Henry. The second, which included some who became William's firm supporters, such as Robert, Count of Eu

Robert, Count of Eu and Lord of Hastings (d. between 1089-1093), son of William I, Count of Eu, and his wife Lesceline. Count of Eu and Lord of Hastings.

Robert commanded 60 ships in the fleet supporting the landing of William I of England and ...

, Walter Giffard

Walter Giffard (April 1279) was Lord Chancellor of England and Archbishop of York.

Family

Giffard was a son of Hugh Giffard of Boyton in Wiltshire,Greenway Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300: Volume 6: York: Archbishops' a royal justice, ...

, Roger of Mortemer, and William de Warenne, faced the other invading force. This second force defeated the invaders at the Battle of Mortemer

The Battle of Mortemer was a defeat for Henry I of France when he led an army against his vassal, William the Bastard, Duke of Normandy in 1054. William was eventually to become known as William the Conqueror after his successful invasion and ...

. In addition to ending both invasions, the battle allowed the duke's ecclesiastical supporters to depose Archbishop Mauger. Mortemer thus marked another turning point in William's growing control of the duchy,Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 68–69 although his conflict with the French king and the Count of Anjou continued until 1060.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 75–76 Henry and Geoffrey led another invasion of Normandy in 1057 but were defeated by William at the Battle of Varaville

The Battle of Varaville was a battle fought in 1057 by William, Duke of Normandy, against King Henry I of France and Count Geoffrey Martel of Anjou.

In August 1057, King Henry and Count Geoffrey invaded Normandy on a campaign that was aimed at ...

. This was the last invasion of Normandy during William's lifetime. In 1058, William invaded the County of Dreux

The Counts of Dreux were a noble family of France, who took their title from the chief stronghold of their domain, the château of Dreux, which lies near the boundary between Normandy and the Île-de-France. They are notable for inheriting the D ...

and took Tillières-sur-Avre

Tillières-sur-Avre is a commune in the Eure department and Normandy region of northern France.

In 1013, Richard II of Normandy erected a castle on the benches of the Avre river as this region was being contested by the Norman dukes, the counts ...

and Thimert. Henry attempted to dislodge William, but the siege of Thimert The siege of Thimert (1058–60) was the last military action in the war between King Henry I of France and Duke William II of Normandy.

In the first half of 1058, William captured the French fortress at Thimert in the County of Dreux. According t ...

dragged on for two years until Henry's death. The deaths of Count Geoffrey and the king in 1060 cemented the shift in the balance of power towards William.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 50

One factor in William's favour was his marriage to

One factor in William's favour was his marriage to Matilda of Flanders

Matilda of Flanders (french: link=no, Mathilde; nl, Machteld) ( 1031 – 2 November 1083) was Queen of England and Duchess of Normandy by marriage to William the Conqueror, and regent of Normandy during his absences from the duchy. She was ...

, the daughter of Count Baldwin V of Flanders. The union was arranged in 1049, but Pope Leo IX

Pope Leo IX (21 June 1002 – 19 April 1054), born Bruno von Egisheim-Dagsburg, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 February 1049 to his death in 1054. Leo IX is considered to be one of the most historically ...

forbade the marriage at the Council of Rheims Reims, located in the north-east of modern France, hosted several councils or synods in the Roman Catholic Church. These councils did not universally represent the church and are not counted among the official ecumenical councils.

Early synodal cou ...

in October 1049. The marriage nevertheless went ahead sometime in the early 1050s,Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 76 possibly unsanctioned by the pope. According to a late source not generally considered to be reliable, papal sanction was not secured until 1059, but as papal-Norman relations in the 1050s were generally good, and Norman clergy were able to visit Rome in 1050 without incident, it was probably secured earlier.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 44–45 Papal sanction of the marriage appears to have required the founding of two monasteries in Caen – one by William and one by Matilda.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 80 The marriage was important in bolstering William's status, as Flanders was one of the more powerful French territories, with ties to the French royal house and to the German emperors. Contemporary writers considered the marriage, which produced four sons and five or six daughters, to be a success.

Appearance and character

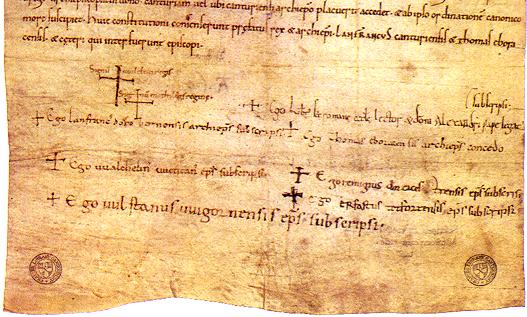

No authentic portrait of William has been found; the contemporary depictions of him on the Bayeux Tapestry and on his seals and coins are conventional representations designed to assert his authority.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 115–116 There are some written descriptions of a burly and robust appearance, with a guttural voice. He enjoyed excellent health until old age, although he became quite fat in later life.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 368–369 He was strong enough to draw bows that others were unable to pull and had great stamina. Geoffrey Martel described him as without equal as a fighter and as a horseman.Searle ''Predatory Kinship'' p. 203 Examination of William'sfemur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates with ...

, the only bone to survive when the rest of his remains were destroyed, showed he was approximately in height.

There are records of two tutors for William during the late 1030s and early 1040s, but the extent of his literary education is unclear. He was not known as a patron of authors, and there is little evidence that he sponsored scholarships or other intellectual activities. Orderic Vitalis records that William tried to learn to read Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

late in life, but he was unable to devote sufficient time to the effort and quickly gave up.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 323 William's main hobby appears to have been hunting. His marriage to Matilda appears to have been quite affectionate, and there are no signs that he was unfaithful to her – unusual in a medieval monarch. Medieval writers criticised William for his greed and cruelty, but his personal piety was universally praised by contemporaries.

Norman administration

Norman government under William was similar to the government that had existed under earlier dukes. It was a fairly simple administrative system, built around the ducal household,Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 133 which consisted of a group of officers includingstewards

Steward may refer to:

Positions or roles

* Steward (office), a representative of a monarch

* Steward (Methodism), a leader in a congregation and/or district

* Steward, a person responsible for supplies of food to a college, club, or other inst ...

, butler

A butler is a person who works in a house serving and is a domestic worker in a large household. In great houses, the household is sometimes divided into departments with the butler in charge of the dining room, wine cellar, and pantry. Some a ...

s, and marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used for elevated o ...

s.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 23–24 The duke travelled constantly around the duchy, confirming charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

s and collecting revenues.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 63–65 Most of the income came from the ducal lands, as well as from tolls and a few taxes. This income was collected by the chamber, one of the household departments.

William cultivated close relations with the church in his duchy. He took part in church councils and made several appointments to the Norman episcopate, including the appointment of Maurilius

Maurilius (–1067) was a Norman Archbishop of Rouen from 1055 to 1067.

Maurilius was originally from Reims, and was born about 1000. He trained as a priest at Liege and became a member of the cathedral chapter of Halberstadt.Douglas ''William ...

as Archbishop of Rouen. Another important appointment was that of William's half-brother, Odo, as Bishop of Bayeux

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Bayeux and Lisieux (Latin: ''Dioecesis Baiocensis et Lexoviensis''; French: ''Diocèse de Bayeux et Lisieux'') is a diocese of the Catholic Church in France. It is coextensive with the Department of Calvados and is ...

in either 1049 or 1050. He also relied on the clergy for advice, including Lanfranc

Lanfranc, OSB (1005 1010 – 24 May 1089) was a celebrated Italian jurist who renounced his career to become a Benedictine monk at Bec in Normandy. He served successively as prior of Bec Abbey and abbot of St Stephen in Normandy and then ...

, a non-Norman who rose to become one of William's prominent ecclesiastical advisors in the late 1040s and remained so throughout the 1050s and 1060s. William gave generously to the church;Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 64–66 from 1035 to 1066, the Norman aristocracy founded at least twenty new monastic houses, including William's two monasteries in Caen, a remarkable expansion of religious life in the duchy.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 111–112

English and continental concerns

In 1051 the childless King Edward of England appears to have chosen William as his successor.Barlow "Edward" ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' William was the grandson of Edward's maternal uncle, Richard II of Normandy.Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alf ...

'', in the "D" version, states that William visited England in the later part of 1051, perhaps to secure confirmation of the succession, or perhaps William was attempting to secure aid for his troubles in Normandy. The trip is unlikely given William's absorption in warfare with Anjou at the time. Whatever Edward's wishes, it was likely that any claim by William would be opposed by Godwin, Earl of Wessex

Godwin of Wessex ( ang, Godwine; – 15 April 1053) was an English nobleman who became one of the most powerful earls in Kingdom of England, England under the Denmark, Danish king Cnut the Great (King of England from 1016 to 1035) and his succ ...

, a member of the most powerful family in England.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 46–47 Edward had married Edith

Edith is a feminine given name derived from the Old English words ēad, meaning 'riches or blessed', and is in common usage in this form in English, German, many Scandinavian languages and Dutch. Its French form is Édith. Contractions and var ...

, Godwin's daughter, in 1043, and Godwin appears to have been one of the main supporters of Edward's claim to the throne.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 86–87 By 1050, however, relations between the king and the earl had soured, culminating in a crisis in 1051 that led to the exile of Godwin and his family from England. It was during this exile that Edward offered the throne to William.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 89–91 Godwin returned from exile in 1052 with armed forces, and a settlement was reached between the king and the earl, restoring the earl and his family to their lands and replacing Robert of Jumièges

Robert of Jumièges (died between 1052 and 1055) was the first Norman archbishop of Canterbury.Barlow ''Edward the Confessor'' p. 50 He had previously served as prior of the Abbey of St Ouen at Rouen in Normandy, before becoming abbot of Jumi� ...

, a Norman whom Edward had named Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

, with Stigand

Stigand (died 1072) was an Anglo-Saxon churchman in pre-Norman Conquest England who became Archbishop of Canterbury. His birth date is unknown, but by 1020 he was serving as a royal chaplain and advisor. He was named Bishop of Elmham in 104 ...

, the Bishop of Winchester

The Bishop of Winchester is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Winchester in the Church of England. The bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire. The Bishop of Winchester has always held ''ex officio'' (except dur ...

.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 95–96 No English source mentions a supposed embassy by Archbishop Robert to William conveying the promise of the succession, and the two Norman sources that mention it, William of Jumièges

William of Jumièges (born c. 1000 - died after 1070) (french: Guillaume de Jumièges) was a contemporary of the events of 1066, and one of the earliest writers on the subject of the Norman conquest of England. He is himself a shadowy figure, only ...

and William of Poitiers

William of Poitiers ( 10201090) (LA: Guillelmus Pictaviensis; FR: Guillaume de Poitiers) was a Frankish priest of Norman origin and chaplain of Duke William of Normandy (William the Conqueror), for whom he chronicled the Norman Conquest of Engla ...

, are not precise in their chronology of when this visit took place.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 93–95

Count Herbert II of Maine

Herbert II (died 9 March 1062) was Count of Maine from 1051 to 1062. He was a Hugonide, son of Hugh IV of Maine and Bertha of Blois.

On the death of Hugh IV, Geoffrey Martel, Count of Anjou occupied Maine, expelling Berthe de Blois and Gerva ...

died in 1062, and William, who had betrothed his eldest son Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

to Herbert's sister Margaret, claimed the county through his son. Local nobles resisted the claim, but William invaded and by 1064 had secured control of the area.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' p. 174 William appointed a Norman to the bishopric of Le Mans

The Catholic Diocese of Le Mans (Latin: ''Dioecesis Cenomanensis''; French: ''Diocèse du Mans'') is a Catholic diocese of France. The diocese is now a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Rennes, Dol, and Saint-Malo but had previously been suffraga ...

in 1065. He also allowed his son Robert Curthose to do homage to the new Count of Anjou, Geoffrey the Bearded.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 53 William's western border was thus secured, but his border with Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

remained insecure. In 1064 William invaded Brittany in a campaign that remains obscure in its details. Its effect, though, was to destabilise Brittany, forcing the duke, Conan II, to focus on internal problems rather than on expansion. Conan's death in 1066 further secured William's borders in Normandy. William also benefited from his campaign in Brittany by securing the support of some Breton nobles who went on to support the invasion of England in 1066.Douglas ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 178–179

In England, Earl Godwin died in 1053 and his sons were increasing in power:

In England, Earl Godwin died in 1053 and his sons were increasing in power: Harold

Harold may refer to:

People

* Harold (given name), including a list of persons and fictional characters with the name

* Harold (surname), surname in the English language

* András Arató, known in meme culture as "Hide the Pain Harold"

Arts a ...

succeeded to his father's earldom, and another son, Tostig

Tostig Godwinson ( 102925 September 1066) was an Anglo-Saxon Earl of Northumbria and brother of King Harold Godwinson. After being exiled by his brother, Tostig supported the Norwegian king Harald Hardrada's invasion of England, and was kille ...

, became Earl of Northumbria

Earl of Northumbria or Ealdorman of Northumbria was a title in the late Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Scandinavian and early Anglo-Norman period in England. The ealdordom was a successor of the Norse Kingdom of York. In the seventh century, the Anglo-Saxo ...

. Other sons were granted earldoms later: Gyrth

Gyrth Godwinson (Old English: ''Gyrð Godƿinson''; 1032 – 14 October 1066) was the fourth son of Earl Godwin, and thus a younger brother of Harold Godwinson. He went with his eldest brother Sweyn into exile to Flanders in 1051, but unlike S ...

as Earl of East Anglia

The Earls of East Anglia were governors of East Anglia during the 11th century. The post was established by Cnut in 1017 and disappeared following Ralph Guader's participation in the failed Revolt of the Earls in 1075.

Ealdormen of East Anglia

U ...

in 1057 and Leofwine as Earl of Kent

The peerage title Earl of Kent has been created eight times in the Peerage of England and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. In fiction, the Earl of Kent is also known as a prominent supporting character in William Shakespeare's tragedy K ...

sometime between 1055 and 1057.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 98–100 Some sources claim that Harold took part in William's Breton campaign of 1064 and swore to uphold William's claim to the English throne at the end of the campaign, but no English source reports this trip, and it is unclear if it actually occurred. It may have been Norman propaganda designed to discredit Harold, who had emerged as the main contender to succeed King Edward.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 102–103 Meanwhile, another contender for the throne had emerged – Edward the Exile

Edward the Exile (1016 – 19 April 1057), also called Edward Ætheling, was the son of King Edmund Ironside and of Ealdgyth. He spent most of his life in exile in the Kingdom of Hungary following the defeat of his father by Cnut the Great.

Ex ...

, son of Edmund Ironside

Edmund Ironside (30 November 1016; , ; sometimes also known as Edmund II) was King of the English from 23 April to 30 November 1016. He was the son of King Æthelred the Unready and his first wife, Ælfgifu of York. Edmund's reign was marred by ...

and a grandson of Æthelred II, returned to England in 1057, and although he died shortly after his return, he brought with him his family, which included two daughters, Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular througho ...

and Christina, and a son, Edgar the Ætheling

Edgar is a commonly used English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Eadgar'' (composed of '' ead'' "rich, prosperous" and ''gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the later medieval period; it was, however, rev ...

.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 97

In 1065 Northumbria revolted against Tostig, and the rebels chose Morcar

Morcar (or Morkere) ( ang, Mōrcǣr) (died after 1087) was the son of Ælfgār (earl of Mercia) and brother of Ēadwine. He was the earl of Northumbria from 1065 to 1066, when he was replaced by William the Conqueror with Copsi.

Dispute with t ...

, the younger brother of Edwin, Earl of Mercia

Edwin (Old English: ''Ēadwine'') (died 1071) was the elder brother of Morcar, Earl of Northumbria, son of Ælfgār, Earl of Mercia and grandson of Leofric, Earl of Mercia. He succeeded to his father's title and responsibilities on Ælfgār's de ...

, as earl in place of Tostig. Harold, perhaps to secure the support of Edwin and Morcar in his bid for the throne, supported the rebels and persuaded King Edward to replace Tostig with Morcar. Tostig went into exile in Flanders, along with his wife Judith, who was the daughter of Baldwin IV, Count of Flanders. Edward was ailing, and he died on 5 January 1066. It is unclear what exactly happened at Edward's deathbed. One story, deriving from the '' Vita Ædwardi'', a biography of Edward, claims that he was attended by his wife Edith, Harold, Archbishop Stigand, and Robert FitzWimarc

Robert fitz Wimarc (died before 1075, Theydon Mount, Ongar, Essex) was a kinsman of both Edward the Confessor and William of Normandy, and was present at Edward's death bed.

Nothing of his background is known except his kinship to the English ...

, and that the king named Harold as his successor. The Norman sources do not dispute the fact that Harold was named as the next king, but they declare that Harold's oath and Edward's earlier promise of the throne could not be changed on Edward's deathbed. Later English sources stated that Harold had been elected as king by the clergy and magnates of England.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 107–109

Invasion of England

Harold's preparations

Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, although some controversy surrounds who performed the ceremony. English sources claim that Ealdred, the Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers th ...

, performed the ceremony, while Norman sources state that the coronation was performed by Stigand, who was considered a non-canonical archbishop by the papacy.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 115–116 Harold's claim to the throne was not entirely secure, as there were other claimants, perhaps including his exiled brother Tostig.Huscroft ''Ruling England'' pp. 12–13 King Harald Hardrada

Harald Sigurdsson (; – 25 September 1066), also known as Harald III of Norway and given the epithet ''Hardrada'' (; modern no, Hardråde, roughly translated as "stern counsel" or "hard ruler") in the sagas, was King of Norway from 1046 t ...

of Norway also had a claim to the throne as the uncle and heir of King Magnus I, who had made a pact with Harthacnut in about 1040 that if either Magnus or Harthacnut died without heirs, the other would succeed. The last claimant was William of Normandy, against whose anticipated invasion King Harold Godwinson made most of his preparations.

Harold's brother Tostig made probing attacks along the southern coast of England in May 1066, landing at the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

using a fleet supplied by Baldwin of Flanders. Tostig appears to have received little local support, and further raids into Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

and near the River Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers Ouse and Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms part of the boundary between the ...

met with no more success, so he retreated to Scotland, where he remained for a time. According to the Norman writer William of Jumièges, William had meanwhile sent an embassy to King Harold Godwinson to remind Harold of his oath to support William's claim, although whether this embassy actually occurred is unclear. Harold assembled an army and a fleet to repel William's anticipated invasion force, deploying troops and ships along the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

for most of the summer.

William's preparations

William of Poitiers describes a council called by Duke William, in which the writer gives an account of a great debate that took place between William's nobles and supporters over whether to risk an invasion of England. Although some sort of formal assembly probably was held, it is unlikely that any debate took place, as the duke had by then established control over his nobles, and most of those assembled would have been anxious to secure their share of the rewards from the conquest of England.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 79–81 William of Poitiers also relates that the duke obtained the consent of Pope Alexander II for the invasion, along with a papal banner. The chronicler also claimed that the duke secured the support of

William of Poitiers describes a council called by Duke William, in which the writer gives an account of a great debate that took place between William's nobles and supporters over whether to risk an invasion of England. Although some sort of formal assembly probably was held, it is unlikely that any debate took place, as the duke had by then established control over his nobles, and most of those assembled would have been anxious to secure their share of the rewards from the conquest of England.Bates ''William the Conqueror'' pp. 79–81 William of Poitiers also relates that the duke obtained the consent of Pope Alexander II for the invasion, along with a papal banner. The chronicler also claimed that the duke secured the support of Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor

Henry IV (german: Heinrich IV; 11 November 1050 – 7 August 1106) was Holy Roman Emperor from 1084 to 1105, King of Germany from 1054 to 1105, King of Italy and Burgundy from 1056 to 1105, and Duke of Bavaria from 1052 to 1054. He was the son ...

, and King Sweyn II of Denmark

Sweyn Estridsson Ulfsson ( on, Sveinn Ástríðarson, da, Svend Estridsen; – 28 April 1076) was King of Denmark (being Sweyn II) from 1047 until his death in 1076. He was the son of Ulf Thorgilsson and Estrid Svendsdatter, and the grandson ...

. Henry was still a minor, however, and Sweyn was more likely to support Harold, who could then help Sweyn against the Norwegian king, so these claims should be treated with caution. Although Alexander did give papal approval to the conquest after it succeeded, no other source claims papal support prior to the invasion.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 120–123 Events after the invasion, which included the penance William performed and statements by later popes, do lend circumstantial support to the claim of papal approval. To deal with Norman affairs, William put the government of Normandy into the hands of his wife for the duration of the invasion.

Throughout the summer, William assembled an army and an invasion fleet in Normandy. Although William of Jumièges's claim that the ducal fleet numbered 3,000 ships is clearly an exaggeration, it was probably large and mostly built from scratch. Although William of Poitiers and William of Jumièges disagree about where the fleet was built – Poitiers states it was constructed at the mouth of the River Dives

The Dives (; also ''Dive'') is a 105 km long river in the Pays d'Auge, Normandy, France. It flows into the English Channel in Cabourg.

The source of the Dives is near Exmes, in the Orne department. The Dives flows generally north through th ...

, while Jumièges states it was built at Saint-Valery-sur-Somme

Saint-Valery-sur-Somme (, literally ''Saint-Valery on Somme''; pcd, Saint-Wary), commune in the Somme department, is a seaport and resort on the south bank of the River Somme estuary. The town's medieval character and ramparts, its Gothic chur ...

– both agree that it eventually sailed from Valery-sur-Somme. The fleet carried an invasion force that included, in addition to troops from William's own territories of Normandy and Maine, large numbers of mercenaries, allies, and volunteers from Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

, northeastern France, and Flanders, together with smaller numbers from other parts of Europe. Although the army and fleet were ready by early August, adverse winds kept the ships in Normandy until late September. There were probably other reasons for William's delay, including intelligence reports from England revealing that Harold's forces were deployed along the coast. William would have preferred to delay the invasion until he could make an unopposed landing. Harold kept his forces on alert throughout the summer, but with the arrival of the harvest season he disbanded his army on 8 September.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 72

Tostig and Hardrada's invasion

Tostig Godwinson and Harald Hardrada invaded

Tostig Godwinson and Harald Hardrada invaded Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

in September 1066 and defeated the local forces under Morcar and Edwin at the Battle of Fulford near York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

. King Harold received word of their invasion and marched north, defeating the invaders and killing Tostig and Hardrada on 25 September at the Battle of Stamford Bridge

The Battle of Stamford Bridge ( ang, Gefeoht æt Stanfordbrycge) took place at the village of Stamford Bridge, East Riding of Yorkshire, in England, on 25 September 1066, between an English army under King Harold Godwinson and an invading N ...

.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' pp. 118–119 The Norman fleet finally set sail two days later, landing in England at Pevensey Bay

Pevensey ( ) is a village and civil parish in the Wealden district of East Sussex, England. The main village is located north-east of Eastbourne, one mile (1.6 km) inland from Pevensey Bay. The settlement of Pevensey Bay forms part of ...

on 28 September. William then moved to Hastings

Hastings () is a large seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east to the county town of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to the north-west ...

, a few miles to the east, where he built a castle as a base of operations. From there, he ravaged the interior and waited for Harold's return from the north, refusing to venture far from the sea, his line of communication with Normandy.

Battle of Hastings

After defeating Harald Hardrada and Tostig, Harold left much of his army in the north, including Morcar and Edwin, and marched the rest south to deal with the threatened Norman invasion. He probably learned of William's landing while he was travelling south. Harold stopped in London, and was there for about a week before marching to Hastings, so it is likely that he spent about a week on his march south, averaging about per day,Marren ''1066'' p. 93 for the distance of approximately .Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 124 Although Harold attempted to surprise the Normans, William's scouts reported the English arrival to the duke. The exact events preceding the battle are obscure, with contradictory accounts in the sources, but all agree that William led his army from his castle and advanced towards the enemy.Lawson ''Battle of Hastings'' pp. 180–182 Harold had taken a defensive position at the top of Senlac Hill (present-dayBattle, East Sussex

Battle is a small town and civil parish in the local government district of Rother in East Sussex, England. It lies south-east of London, east of Brighton and east of Lewes. Hastings is to the south-east and Bexhill-on-Sea to the south. Batt ...

), about from William's castle at Hastings.Marren ''1066'' pp. 99–100

The battle began at about 9 am on 14 October and lasted all day, but while a broad outline is known, the exact events are obscured by contradictory accounts in the sources.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 126 Although the numbers on each side were about equal, William had both cavalry and infantry, including many archers, while Harold had only foot soldiers and few, if any, archers.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 73 The English soldiers formed up as a

The battle began at about 9 am on 14 October and lasted all day, but while a broad outline is known, the exact events are obscured by contradictory accounts in the sources.Huscroft ''Norman Conquest'' p. 126 Although the numbers on each side were about equal, William had both cavalry and infantry, including many archers, while Harold had only foot soldiers and few, if any, archers.Carpenter ''Struggle for Mastery'' p. 73 The English soldiers formed up as a shield wall

A shield wall ( or in Old English, in Old Norse) is a military formation that was common in ancient and medieval warfare. There were many slight variations of this formation,

but the common factor was soldiers standing shoulder to shoulder ...

along the ridge and were at first so effective that William's army was thrown back with heavy casualties. Some of William's Breton

Breton most often refers to:

*anything associated with Brittany, and generally

** Breton people

** Breton language, a Southwestern Brittonic Celtic language of the Indo-European language family, spoken in Brittany

** Breton (horse), a breed

**Ga ...